Abstract

Despite the expanding body of research on school bullying and interventions, knowledge is limited on what teachers should do to identify, prevent, and reduce bullying. This systematic literature review provides an overview of research on the role of primary school teachers with regard to bullying and victimization. A conceptual framework was developed in line with the Theory of Planned Pehavior, which can serve in further research to facilitate research in investigating the prevention and reduction of bullying. Different elements of this framework were distinguished in categorizing the literature: teachers’ knowledge, attitudes, perceived subjective norms, and self-efficacy, which impacted subsequently the likelihood to intervene, used strategies and programs, and ultimately the bullying prevalence in the classroom. In total, 75 studies complied to the inclusion criteria and were reviewed systematically. The Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment was used to assess the quality of each study, leading to 25 papers with an adequate research design that were discussed in more detail. The approach in this review provides a framework to combine studies on single or multiple elements of a complex theoretical model of which only some parts have been empirically investigated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Teachers’ Role in Bullying

Over the previous decades, there has been an increased research interest in school bullying (Volk et al., 2017). Bullying has been defined as systematic, intentional, goal-directed aggression toward victims who are physically or socially weaker than the bully or bullies. Bullying often occurs in schools out of teachers’ sight, for example on the playground or in the lunchroom (Bradshaw et al., 2007; Veenstra et al., 2014), and is therefore difficult for teachers to detect. However, even when bullying occurs in their sight, teachers often fail to take action (Craig et al., 2000a; Veenstra et al., 2014), although their responses have an important effect on preventing and reducing bullying (Migliaccio, 2015; Sokol et al., 2016; van Verseveld et al., 2019). It is therefore important to know which individual and contextual features play a role in how teachers can identify and intervene in bullying effectively.

To date, an overarching framework is missing in research on teachers’ characteristics and behavior in relation to bullying (Oldenburg et al., 2015; Yoon & Bauman, 2014), but it would contribute to the development of more effective and tailored coaching and support for teachers. We aimed to fill this gap by, first, providing a systematic overview of the literature addressing the role of teachers’ characteristics and behaviors in identifying, preventing, and reducing bullying in primary school. Second, we intended to develop a theoretical framework by extending the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 2012), that could benefit future research on teachers’ role in tackling bullying. We assessed all reviewed studies on their quality by using the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale, which provided insight in the generalizability of findings.

Our review focused on primary school teachers. Most literature on bullying has focused on primary education, and many anti-bullying programs have been developed and tested in primary schools. Furthermore, the context of primary schools and the effectiveness in tackling bullying differs from secondary education (Yeager et al., 2015), with less frequent contact with students and changing class compositions depending on students’ specialization or subject choices. This potentially changes teachers’ ability to identify and observe bullying incidents, and also the extent to which they can influence or alter the situation.

Theory of Planned Behavior Applied to Teachers’ Anti-Bullying Behavior

The theory of planned behavior (TPB; Ajzen, 1991, 2012) is an action model based on the theory of reasoned action (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010), and helps to understand and predict changes in human social behavior based on the assumption that human behavior is reasonable. According to TPB, there is a certain sequence where individual factors affect humans’ attitudes toward behavior, their subjective norms, and their perceived behavioral control. Subsequently, these elements influence someone’s intention of behavior and finally ends in the display of actual behavior (Ajzen, 2012).

Applying the framework to teachers’ anti-bullying efforts, we can also distinguish these different elements, which are depicted in Fig. 1. The first element concerns attitudes, which refer to teachers’ attitudes toward bullying interventions, with the underlying beliefs of taking bullying seriously and having empathy with victims (van Verseveld et al., 2019). It is assumed that the more teachers take bullying seriously and have empathy with victims, the more they are inclined to intervene, and might therefore also be more positive about intervening. Research included in the review indicated that teachers are more likely to intervene when they consider bullying as serious and less normative and when they have empathy with victims (e.g., Dedousis-Wallace et al., 2014; Yoon, 2004).

The second element concerns perceived behavioral control and refers to self-efficacy. Higher self-efficacy was shown to result in more perseverance and performance (Ajzen, 2012). In line with this, a positive relation was expected and found between teachers’ self-efficacy and the likelihood to intervene (e.g., Dedousis-Wallace et al., 2014; Yoon et al., 2016).

The third element is the subjective norms, which are defined as teachers’ perceptions of how important others, such as the principal and colleagues, would rate their behavior. Teachers can perceive these normative beliefs as social pressure to which they want to comply, which guides their intentional behavior. For teachers, the norms and actions of their colleagues and principal are expected to be important for comfort to intervene (O’Brennan et al., 2014), implementation fidelity (e.g., Cunningham et al., 2016), and bullying prevalence (Roland & Galloway, 2004). Participation in an anti-bullying program or school policies on bullying also shape prevailing norms and expectations in the school; for instance, by influencing the likelihood to intervene (Benítez et al., 2009).

In addition to the three previously mentioned elements, we propose that a fourth element is important, teachers’ knowledge, that relates to the other elements, and influences teachers’ likelihood to intervene (Dedousis-Wallace et al., 2014) and their actual behavior. Before being able to intervene, teachers must know about bullying as a phenomenon (Allen, 2010), its types and consequences, and about its prevalence in their classroom. Hence, we added knowledge to the model at the same prediction level for intention to intervene as attitudes, perceived behavioral control, and subjective norms (see Fig. 1).

According to the TPB, these elements together influence the intention of behavior, in this case, teachers’ likelihood to intervene, which forms the precedent for actual behavior, referring to using strategies to tackle bullying or applying elements of anti-bullying programs or policies. However, to study teachers’ effectiveness in tackling bullying, the bullying prevalence in the classroom can be considered as the final outcome, that indicates whether bullying reduction or prevention in class is achieved by the displayed behavior of the teacher. We, therefore, added bullying prevalence as outcome in our theoretical framework, see Fig. 1.

Even though TPB is a thoroughly tested theory in other fields, such as health sciences and health-related behavior, its relation to teachers’ bullying intervention behavior is rather limited (Hawley & Williford, 2015). Several studies argued that the TPB may be relevant for understanding the potential role of teacher self-efficacy and attitudinal change in predicting their intentions and behaviors to tackle bullying (e.g., Cunningham et al., 2019a; Gregus et al., 2017; Hawley & Williford, 2015; MacFarlane & Woolfson, 2013; van Verseveld et al., 2019; Yoon et al., 2011). However, no previous study tested the framework as a whole and applied it to teachers in relation to bullying. Through this systematic review, we investigated the extent to which research on teachers’ role in tackling bullying can be classified according to the conceptual framework based on the TPB and identified potential research caveats and avenues for further research.

Method

Databases and Search Strategies

Articles that were included were found through the electronic databases of SocINDEX, PsycINFO, and ERIC. These bibliographic databases contain high-quality peer-reviewed research in sociology, psychology, and educational sciences and cover the relevant specific and cross-disciplinary literature in each field. At the start of the search, the determined key terms were “bullying,” “teacher,” and “victimization.” Because variations of each search term can be used in titles or keywords, (e.g., bullying, bully, bullies) an asterisk was used to enlarge search terms: bull*, teach*, and victimize*. Each database contains a list with so-called subject terms (also known as search terms or key identifiers). Journal articles with “victimization” in British spelling in their title or abstract were linked to the subject term “victimization” in American spelling in all databases. As the subject term “victim(s)” was linked to victims of crime or abuse, and not to victims of bullying, we lengthened the search term “victim” to “victimize*” in all databases. In all three databases two cross-searches were performed; the first search focused on “bull* AND teach*.” The second search was performed with the combination “victimize* AND teacher*” in PsycINFO, and with the combination “(victims of bullying) AND teach*” in SocINDEX and ERIC, as these were suggested subject terms commonly used in these search engines.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We included articles that were published until February 2022. No restrictions were imposed to the geographic area where the research was carried out, nor to the publication year. To ascertain the methodological quality of included literature, articles had to be peer-reviewed and published in a scientific journal and be available in English. Other formats, such as books or book chapters, were excluded. For inclusion, it was important that the study comprised (i) primary school teachers; (ii) qualitative or quantitative empirical data on teachers (articles exclusively focusing on children were excluded); (iii) teachers’ characteristics and/or behavior with regard to bullying; and (iv) general bullying (articles solely focused on, for example, minority bullying, such as sexual- or identity-related, weight-related bullying, or school shootings were excluded).

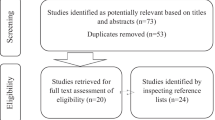

Paper Selection

Figure 2 presents a Prisma flow chart (Silva et al., 2017), visualizing the identification and selection process for the inclusion of articles. The “bully* AND teach*” search resulted in 585 hits in SocINDEX, 899 hits in PsycINFO, and 1329 hits in ERIC, whereas the second search, with “victimiz*AND teach*,” revealed 76, 1790, and 186 hits, respectively.

In the following step, articles were selected when they seemed to meet the inclusion criteria based on the title, and, in case of doubt, the abstract. The articles selected during the first search were marked in the hits of the second search, enabling us to prevent duplicates within the same database. This resulted in the selection of 60 articles in SocINDEX, 100 in PsycINFO, and 111 results in ERIC for the search on bullying and teachers, and 6, 11, and 12 results in the search on victimization and teachers. After removing duplicates in the different databases (33 articles) 234 articles remained.

Three researchers, who selected articles by reading the title and abstract, reviewed the list of 234 articles independently in order to assess if they met the inclusion criteria. Consensus was reached for 202 publications. The three researchers read and discussed the remaining 32 articles, and then made a final decision. Of the 234 articles, 107 articles did not meet the inclusion criteria because they lacked empirical teacher data in primary education or did not have data in relation to classroom bullying. An additional 52 publications were excluded after reading the content of the publication, when it appeared they did not include teacher data or solely focused on teachers from middle, secondary, or high school, or only had teacher reports about student behavior, but not about themselves in relation to bullying. Furthermore, three papers focused on externalizing or aggressive behavior of which bullying was only a small part, two papers concerned bullying between teachers and students, and one study concerned a meta-analysis of which some studies were already included. These studies were therefore excluded. The final selection contained 75 studies.

In discussing the studies we first identified study- and teacher- characteristics of all 75 studies, and categorized all studies according to the TPB framework. In the next step, we assessed the quality of the studies and only included studies in the discussion of results that scored six or more points on a 10-point scale of the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (Wells et al., 2013), resulting in 25 studies. These studies scored adequately on selection (such as representation and sample size), comparability (controlling for important factors), and outcome (assessment and adequate statistical testing) and are therefore more suitable for generalization. For that reason, we discuss these studies in more detail. The reasons for omitting classification stars in the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment allow us to identify potential caveats in this research field.

Results

Study Characteristics

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the 75 included articles. The first article was published in 1997 and the latest in 2021. The increasing attention for bullying and intervention programs is reflected in an increase in articles concerning the role of primary school teachers in bullying. Most articles were published in psychological and educational journals, and conducted in the USA, followed by the UK, Canada, and Australia. About 35% of the articles originated from non-English countries.

Methodologically, most articles are concerned with cross-sectional research (see Table 2). In 26 of the 66 cross-sectional articles, data were analyzed with comparing means between groups, and 13 articles used regression models. The remaining articles used either simple analysis such as t-tests, structural equation modeling, or were cross-sectional articles using qualitative methods, which were also used in one longitudinal and one mixed-methods study. Thirteen articles had less than 50 respondents, 25 articles had between 50 and 149 respondents, and 37 articles included over 150 respondents.

Teacher Characteristics

Table 3 presents the characteristics of the teachers in the included studies. In most articles, the mean age was not provided or only broadly referred to. In 29 articles, teachers’ mean age was between 20 and 49 years. In almost all articles, the majority of the teachers was female, often even more than 70%, which reflects the sex distribution of teachers in western countries. In seven articles, the teachers were in (pre-service) training and did not have any work experience yet. In six articles, the average teaching experience was less than 10 years, often due to the inclusion of pre-service or recently started teachers. Most articles included in-service teachers, three articles combined pre- and in-service teachers and some articles also included non-teaching school staff or students for comparison with teachers in their study.

Although an inclusion criterion was that articles comprised primary school teachers, some articles covered multiple teacher groups, ranging from kindergarten to primary, middle, or high schools. In total, 27 articles focused on primary school teachers only, whereas 41 articles focused on both primary and secondary school teachers. Seven studies with pre-service teachers were not categorized (Table 4).

Lastly, 20 articles focused on teachers that participated in an anti-bullying program or training. In 2 articles, part of the sample worked with an anti-bullying program, whereas the other part did not.

Quality Assessment

In order to weight the findings from different studies in different domains, and to prevent a distortion of the summary effect, a quality assessment of all papers was carried out according to the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS). The NOS intends to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies by assigning a maximum of 10 stars to each study, by focusing on three categories: selection and representativeness of the study (max. 5 stars), the comparability based on design and analysis (max. 2 stars), and the outcome (max. 3 stars). A study is considered poor if it scores below 5 stars, and/or 1 criterion is not met, or two criteria are unclear. Studies with 5–6 stars are considered fair quality, in case there is no important limitation that invalidates results. Finally, studies with more than six stars, and that meet all criteria, are considered being of good quality (McPheeters et al., 2012). In assessing the studies, we noticed that some studies did not provide explicit information on all criteria. In case of lacking information, no stars were assigned to the study on that criterium. As only 9 studies scored 7 stars or more, indicating good quality (see Appendix for a detailed overview), we decided to also include 13 studies that scored 6 stars. Of these 13 studies, 11 scored on all three categories, indicating at least fair quality, whereas two studies with 6 stars did not score on comparability (Cunningham et al., 2019b (22); Haataja et al., 2015 (36)).

From the 75 studies, 25 studies used an acceptable sampling method, but almost all studies lacked information on the comparison with nonrespondents, which may point to a self-selection bias. Especially studies where teachers could volunteer to fill out an online questionnaire they received through their employer or labor union might include a biased sample. For the comparability criterion, only four studies scored two stars and thus controlled for the most important factor (e.g., gender or teaching experience) and additional factors. However, 41 studies controlled at least for the most important factor. Finally, regarding the outcome criterion, most studies (62) scored at least two stars, often through using self-reports and using clear statistical tests. However, as almost all studies used teacher self-reports as main information in their study, there must be awareness that teachers’ answers can be subject to social desirability and thus present some information bias. To provide transparency in the quality assessment, a more detailed description of studies and their quality assessment can be found in the supplementary material Table S1.

The remaining 50 studies are less representative for the larger teacher population. If we would discuss all findings in detail, it would distort the distinction in weight (in particular in terms of generalizability) that should be assigned to each finding. However, Table 5 and the supplementary material include all studies, providing insight in the quality assessment and an overview of all included research. Table 5 provides information on all studies concerning the outcome and predictor variables according to the theoretical framework.

Different Domains of Research

We categorized and discuss the literature according to the theoretical framework based on TPB as follows: The first elements are (1) knowledge and understanding of bullying; (2) attitudes toward (types of) bullying; (3) perceived subjective norms; and (4) self-efficacy. These elements predict teachers’ (5a) likelihood to intervene, which predicts their actual behavior in the form of (5b) preferred and used strategies, and (5c) program (-evaluations) and policies. The final outcome of the model refers to (6) bullying prevalence in the classroom related. The sequence is also shown in Fig. 1.

Table 5 displays the categorization of all 75 papers according to their outcome and predictor variables. The 25 studies with an asterisk scored six or more stars on the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale, indicating sufficient quality, and will therefore be discussed in the next paragraphs. The numbers correspond to the numbers in the table of Appendix, and are also mentioned in the citations in this result section.

Knowledge

Several studies focused on teachers’ knowledge of bullying, its types and consequences, in relation to their gender, teacher status (i.e., whether they were pre- or in-service teacher), attitudes, received training, and type of bullying. However, none of these studies met the threshold of 6 or more stars on the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (see Table 5 for more details).

Attitudes

Teachers’ attitudes refer to their perception of (different types of) bullying, and the extent to which they take incidents seriously and have empathy with victims. Table 5 shows that teachers’ attitudes are related to their likelihood to intervene and the use of intervention strategies. Teachers with more than 20 years of service were more likely to think that children who bully out of the sight of teachers were unlikely to change, thereby placing the cause of bullying outside their own influence (Barnes et al., 2012 (5)). Teachers were also compared to non-teaching school staff in their attitudes, and results indicated that teachers spent more time with students and more bully incidents were reported to them than to non-teaching staff (Bradshaw et al., 2013 (15); A. Williford, 2015 (70)). Confidence in handling bullying and the presence of positive mental representations of relationships, referring to the trust of teachers in significant others, were related positively to teachers’ prosocial peer beliefs (Garner, 2017 (33)). Furthermore, studies that scored less than 6 stars investigated teachers’ attitudes in relation to gender, teacher service, length of service, knowledge, self-efficacy, received training, type of bullying, and situational attributes.

Perceived Subjective Norms

Perceived subjective norms refer to the teachers’ perception of how important others, such as the principal and their colleagues, think of their behavior. For instance, if teachers consider to intervene in a bullying situation by disciplining the bully and talking to the victim, they have assumptions of how colleagues think of this strategy, which affects the likelihood to perform this behavior. No studies so far were found that investigated this specific element with regard to bullying intervention and teacher behavior as an outcome variable, but it was used as a predictor variable (see also Table 5).

Self-Efficacy

Teachers’ self-efficacy refers to the extent to which teachers perceive themselves as being able to tackle bullying in their classrooms. Greater staff-connectedness within the team, and being involved in bullying prevention efforts such as training and school-wide programs or policies, were positively related to self-efficacy (O’Brennan et al., 2014 (56)). Furthermore, teachers with higher perceptions of principal support also had higher levels of self-efficacy, specifically for working with bullies (Skinner et al., 2014 (61)). Finally, teachers’ self-efficacy was positively related to students, and especially victims’ self-esteem (van Aalst et al., 2021 (67)). No additional studies focused on teacher self-efficacy as an outcome variable.

Likelihood to Intervene

Research indicated that teachers were more likely to intervene in physical than verbal bullying (Garner et al., 2013 (32); Yoon et al., 2016 (75)), and, relatedly, in direct than indirect forms of bullying (Fischer & Bilz, 2019 (30)). One study found that teachers’ self-efficacy related positively to the likelihood to intervene for both primary and secondary school teachers (Duong & Bradshaw, 2013 (27)), whereas another study found that teachers were not influenced by their self-efficacy in reporting their responses to bullying incidents (Yoon et al., 2016 (75)). Additional research indicated that 4% of the variance in the likelihood to intervene was explained by teachers’ self-efficacy related to bullying intervention (Fischer & Bilz, 2019 (30)).

Furthermore, teachers’ perception of bullying as a threat to their students was also related to a higher likelihood to intervene (Duong & Bradshaw, 2013 (27)). Some additional studies that scored less than 6 stars investigated teachers’ likelihood to intervene in relation to their gender, attitudes, self-efficacy, received training, and situational attributes, and can be found in Table 5 and the supplementary material.

Strategies

Roughly five strategies were mentioned that teachers can employ to tackle bullying: (1) work with bullies; (2) work with victims; (3) discipline bullies; (4) enlist other adults; and (5) ignore the incident (Bauman et al., 2008 (7); Burger et al., 2015 (16); Yoon et al., 2016 (75)). At the individual level, several elements affect teachers’ preferred strategies: teachers who were victimized in their childhood were more likely to discipline bullies or enlist other adults, and male teachers were more likely to enlist others than female teachers (Yoon et al., 2016 (75)). However, other research indicated that females were more likely to work with bullies, whereas males were more likely to ignore a bullying incident (Bauman et al., 2008 (7); Burger et al., 2015 (16)). When teachers perceived bullying as normative behavior, especially among boys, they were more likely to ignore the situation and expect male victims to cope with the problem on their own (Kochenderfer-Ladd & Pelletier, 2008 (44)). Teachers also used more authority-based interventions when they had more teaching experience and self-efficacy, and were more likely to encourage victims in being assertive when they had more empathy (Kollerová et al., 2021 (46)).

At the contextual level, higher perceived levels of bullying at school, or having to deal more with bullying, resulted in teachers being more likely to involve students in their bullying prevention strategies (Dake et al., 2004 (24)). Teachers who perceived their school climate as hostile were more likely to discipline bullies and less likely to involve other adults in handling the situation (Yoon et al., 2016 (75)). Several other studies focused on teachers’ strategies to tackle bullying, with gender, attitudes, received training, bullying type, and situational attributes as predictors (see Table 5 for more details).

Anti-Bullying Programs and Policies

Teachers’ confidence and belief in anti-bullying programs and policies are other important elements that contribute to teachers’ intervention behavior. At the individual level, sex, implementation fidelity, teachers’ beliefs, and perceptions played a role. Female teachers attributed more importance to the anti-bullying program for their school, had more confidence in the program, and used the provided literature better than male teachers, but were less likely to attend booster sessions (Ahtola et al., 2012 (1)). However, another study did not find any gender differences in working with an anti-bullying program (Baraldsnes, 2020 (4)). Teachers’ perceptions can also play a role; the more teachers perceive the anti-bullying program to be important to their school, the more they attend training and meetings of the program and implement its elements (Haataja et al., 2015 (37)).

The more confidence teachers felt to implement an anti-bullying program, in this case, the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program, the more they attended school-level activities, such as attending the school kick-off event, participating in training, reading training materials, and attending staff discussion groups and booster trainings (Cecil & Molnar-Main, 2015 (18)).

Contextually, the duration of the training was positively related to implementation fidelity among teachers. This higher implementation fidelity, in turn, was positively related to belief in the program and training participation (Haataja et al., 2015 (37)). Another important element, which also is reflected in the TPB, is behavioral norms, or the perception of important others. Receiving sufficient principal support appeared to play an important role in implementing school-wide prevention programs (Haataja et al., 2015 (37)), but was also important for teachers when faced with confrontational students or parents (Cunningham et al., 2019b (23)). Colleague support was another element mentioned as important for teachers’ participation in anti-bullying programs (Cunningham et al, 2019b (23)). Finally, school size and the relative number of suspensions in a school were inversely related to self-reported implementation fidelity of a statewide anti-bullying policy (Hall & Chapman, 2018 (38)). Additional studies included self-efficacy, received training, principal support, and situational attributes in their investigation of anti-bullying programs and policy implementations (see Table 5 for more details).

Bullying Prevalence

Bullying prevalence is the final outcome discussed in the literature on the role of teachers in bullying and refers to the level of bullying in the classroom, often measured by students’ self-reported bullying and victimization with questions based on the Olweus Bully/Victim questionnaire (Oldenburg et al., 2015 (58); Olweus, 1996). Self-reported bullying prevalence was higher in classrooms with teachers who attributed bullying to external causes, outside their control (Oldenburg et al., 2015 (58)).

With regard to contextual characteristics in relation to bullying prevalence, higher implementation fidelity of an anti-bullying program was related to lower bullying prevalence (Hall & Dawes, 2019 (39)). Professional cooperation and consensus among colleagues on professional matters were related to lower levels of bullying (Roland & Galloway, 2004 (60)). Finally, classrooms with more students had a higher prevalence of peer victimization, whereas less peer victimization was found in multi-grade classrooms (Oldenburg et al., 2015 (58)). Additional studies looked at self-efficacy, preferred strategies, received training, and situational attributes in relation to bullying prevalence.

Discussion

The aim of this systematic review was twofold: (1) to provide an overview of research on the role of primary school teachers in identifying, reducing, and intervening effectively in school bullying, and (2) to develop a theoretical framework and categorize literature according to this framework and identify caveats and possibilities for future research. In doing so, we extended the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991, 2012), and developed a theoretical framework to explain and predict teachers’ behavior to tackle bullying. The underlying assumption of the model is that teachers’ likelihood to intervene precedes their actual intervention behavior (Dedousis-Wallace et al., 2014).

The systematic search and selection of papers resulted in 75 studies, which we categorized on their outcome variables, according to elements of the TPB. This resulted in the following categories: starting with teachers’ (1) knowledge and understanding of bullying, (2) attitudes toward (types of) bullying, (3) perceived subjective norms, and (4) self-efficacy. These are precedents of teachers’ (5a) likelihood to intervene, which subsequently affect the actual behavior of the teacher, measured by (5b) preferred and used strategies and (5c) program (-evaluations) and policies. Studies on (6) the prevalence of bullying in relation to teacher factors were included as a final outcome category. Before discussing every element, we performed a quality assessment of all 75 studies, according to the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS). Only 25 studies scored 6 or more stars on a 10-point scale, suggesting sufficient quality. This indicates that future data collection for research in the field of teachers and tackling bullying can be improved by larger, representative sample sizes.

The results furthermore showed that some elements of the framework were not or rarely studied as outcome variables. Perceived subjective norms, which refer to the support of the principal and colleagues, were used as a predictor variable for understanding teachers’ attitudes, self-efficacy, and working with anti-bullying programs and policies, but no research was found where factors were investigated that affect these subjective norms held by teachers. Also, teachers’ self-efficacy was understudied, with only two studies using it as a dependent variable, whereas multiple studies used it as a predictor in relation to teachers’ attitudes and likelihood to intervene. Both elements are, however, important in explaining and predicting teachers’ likelihood and actual intervention behavior to prevent and reduce bullying, and future research should investigate the elements in more detail and in relation to the other elements of the conceptual framework.

Overall, the results from this review seem to point at two groups of factors that are important for the implementation fidelity of anti-bullying programs or policies and ultimately reducing the bullying prevalence in classrooms. The first concern individual factors; attitudes of teachers toward bullying and their self-efficacy. The anti-bullying attitudes indicate whether they consider bullying as normative behavior, attribute bullying causes to external factors, or take some specific forms of bullying less seriously. Self-efficacy refers to teachers’ confidence in their ability to being able to tackle bullying or to implement an anti-bullying program, which in turn increases their efforts to reduce bullying. The second group of factors is contextual and refers to work conditions and subjective norms. Many elements in the framework that influence teachers’ likelihood to intervene relate to the cooperation teachers perceive among colleagues, and the support they feel from colleagues and the principal. In order to enhance the implementation fidelity of anti-bullying efforts, it is important to work on the attitudes and confidence of teachers on the one hand, and on team building and the principal support on the other hand.

As it is now, the whole model as presented has not been investigated, but given the fit of the studies in the framework based on TPB, there seems to be potential to do so. Future research would benefit from collecting data on all elements, preferably longitudinally. It would also be relevant to collect information on students’ self-reported victimization as an outcome variable, to examine how different elements influence the actual bullying prevalence in the classroom.

The approach in this study was fruitful in combining several studies that tested single or multiple elements of the complex theoretical framework displayed in Fig. 1. Noticeably, the 69 studies that were included in the review were compared on their quality with the use of the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment tool (Wells et al., 2013). Only 25 studies with sufficient quality were discussed. A conclusion to be drawn from this finding is that a substantial number of included studies are of poor quality. Specifically, only 8.5% (n = 6) scored on representativeness, and 57% (n = 39) scored on being somewhat representative of their population. 20% (n = 14) of the included studies compared respondents to non-respondents. The latter can be a serious issue in studies where a convenience sample was used, for instance when an email was sent out to all members of a specific group. The selection of teachers that participated in the research will probably be more interested in tackling bullying or being motivated to do, which increases the likelihood of a biased sample. In addition, 55% (n = 41) included one important control variable in their statistical analysis, which can affect the interpretation of results. Only 3% (n = 2) included all relevant control variables. Finally, 10% (n = 7) used validated measurements, whereas most studies described their measurements in detail (n = 64). Future research would benefit from more validated measurement tools and replications to verify results.

Conclusion

This systematic literature review examined 75 articles and provided a synthesis on teachers’ knowledge, attitudes, and interventions, and their relations to bullying prevalence in primary schools. Results indicated a broad variety in methodological approaches and participant characteristics amid the different articles, as well as a focus on different predictor and outcome variables. The outcomes that have been distinguished, corresponded to the conceptual framework that was developed, which may be used in further research and by policy makers as a starting point in their aim to improve teachers’ effectiveness in identifying, preventing, and reducing bullying in the classroom.

Availability of Data and Material

The data that support the findings of this study are available from D.v.A. upon reasonable request.

References

Studies marked with an asterix * are included in the review

*Ahtola, A., Haataja, A., Kärnä, A., Poskiparta, E., & Salmivalli, C. (2012). For children only? Effects of the KiVa antibullying program on teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28(6), 851–859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2012.03.006

*Ahtola, A., Haataja, A., Kärnä, A., Poskiparta, E., & Salmivalli, C. (2013). Implementation of anti-bullying lessons in primary classrooms: How important is head teacher support? Educational Research, 55(4), 376–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2013.844941

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior organizational behavior and human decision processes. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211.

Ajzen, I. (2012). The theory of planned behavior. In P. A. M. Van Lange, A. W. Kruglanski, & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 438–459). Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446249215.n22

Allen, K. P. (2010). Classroom management, bullying, and teacher practices. Professional Educator, 34(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2011.01.002

*Baller, S. L., Wenos, J. Z., & Peachey, A. A. (2019). Bullying prevention in an elementary school: An exploration of educator and staff perspectives. Journal of Educational Issues, 5(1), 162. https://doi.org/10.5296/jei.v5i1.14634

*Baraldsnes, D. (2020). Bullying prevention and school climate: Correlation between teacher bullying prevention. International Journal of Developmental Science, 14(3–4), 85–95.

*Barnes, A., Cross, D., Lester, L., Hearn, L., Epstein, M., & Monks, H. (2012). The invisibility of covert bullying among students: Challenges for school intervention. Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 22(2), 206–226. https://doi.org/10.1017/jgc.2012.27

*Bauman, S., & Del Rio, A. (2006). Preservice teachers’ responses to bullying scenarios: Comparing physical, verbal, and relational bullying. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(1), 219–231. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.98.1.219

*Bauman, S., Rigby, K., & Hoppa, K. (2008). US teachers’ and school counsellors’ strategies for handling school bullying incidents. Educational Psychology, 28(7), 837–856. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410802379085

*Begotti, T., Tirassa, M., & Acquadro Maran, D. (2017). School bullying episodes: Attitudes and intervention in pre-service and in-service Italian teachers. Research Papers in Education, 32(2), 170–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2016.1158857

*Bell, K. J. S., & Willis, W. G. (2016). Teachers perceptions of bullying among youth. Journal of Educational Research, 109(2), 159–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2014.931833

*Benítez, J. L., García-Berbén, A., & Fernández-Cabezas, M. (2009). The impact of a course on bullying within the pre-service teacher training curriculum. Education & Psychology, 7(1), 191–208.

*Biggs, B. K., Vernberg, E. M., Twemlow, S. W., Fonagy, P., & Dill, E. J. (2008). Teacher adherence and its relations to teacher attitudes and student outcomes in an elementary school-based violence prevention program. School Psychology Review, 37(4), 533–549.

*Blain-Arcaro, C., Smith, J. D., Cunningham, C. E., Vaillancourt, T., & Rimas, H. (2012). Contextual attributes of indirect bullying situations that influence teachers’ decisions to intervene. Journal of School Violence, 11(3), 226–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2012.682003

*Boulton, M. J. (2014). Teachers’ self-efficacy, perceived effectiveness beliefs, and reported use of cognitive-behavioral approaches to bullying among pupils: Effects of in-service training with the I DECIDE program. Behavior Therapy, 45(3), 328–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2013.12.004

Bradshaw, C. P., Sawyer, A. L., & O’Brennan, L. M. (2007). Bullying and peer victimization at school : Perceptual differences between students and school staff. School Psychology Review, 36(3), 361–382.

*Bradshaw, C. P., Waasdorp, T. E., O’Brennan, L. M., & Gulemetova, M. (2013). Teachers’ and Education Support Professionals’ Perspectives on Bullying and Prevention: Findings from a National Education Association Study, 42(3), 280–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2008.10.054.The

*Burger, C., Strohmeier, D., Spröber, N., Bauman, S., & Rigby, K. (2015). How teachers respond to school bullying: An examination of self-reported intervention strategy use, moderator effects, and concurrent use of multiple strategies. Teaching and Teacher Education, 51, 191–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.07.004

*Campbell, M., Whiteford, C., & Hooijer, J. (2019). Teachers’ and parents’ understanding of traditional and cyberbullying. Journal of School Violence, 18(3), 388–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2018.1507826

*Cecil, H., & Molnar-Main, S. (2015). Olweus bullying prevention program: Components implemented by elementary classroom and specialist teachers. Journal of School Violence, 14(4), 335–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2014.912956

*Chen, L. M., Sung, Y. H., & Cheng, W. (2017). How to enhance teachers’ bullying identification: A comparison among providing a training program, a written definition, and a definition with a checklist of bullying characteristics. Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 26(6), 351–359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-017-0354-1

*Cosgrove, H. E., & Nickerson, A. B. (2017). Anti-bullying/harassment legislation and educator perceptions of severity, effectiveness, and school climate: A cross-sectional analysis. Educational Policy, 31(4), 518–545. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904815604217

*Craig, W., Henderson, K., & Murphy, J. G. (2000a). Prospective teachers’ attitudes toward bullying and victimization. Sage Publications, Ltd..pdf.

Craig, W., Pepler, D., & Atlas, R. (2000b). Observations of bullying in the playground and in the classroom.pdf. School Psychology International, 21(1), 22–36.

*Cunningham, C. E., Mapp, C., Rimas, H., Cunningham, L., Mielko, S., Vaillancourt, T., & Marcus, M. (2016). What limits the effectiveness of antibullying programs? A thematic analysis of the perspective of students. Psychology of Violence, 6(4), 596–606. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039984

Cunningham, C. E., Rimas, H., Vaillancourt, T., Stewart, B., Deal, K., Cunningham, L., Vanniyasingam, T., Duku, E., Buchanan, D. H., & Thabane, L. (2019a). What antibullying program designs motivate student intervention in grades 5 to 8? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 00(00), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2019.1567344

*Cunningham, C. E., Rimas, H., Vaillancourt, T., Stewart, B., Deal, K., Cunningham, L., Vanniyasingam, T., Duku, E., Buchanan, D. H., & Thabane, L. (2019b). What influences educators’ design preferences for bullying prevention programs? Multi-level latent class analysis of a discrete choice experiment. School Mental Health, 12(1), 22–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-019-09334-0

*Dake, J. A., Price, J. H., Telljohann, S. K., & Funk, J. B. (2004). Teacher perceptions and practices regarding school bullying prevention. Journal of School Health, 444(9), 429–444.

*Dawes, M., Norwalk, K. E., Chen, C. C., Hamm, J. V., & Farmer, T. W. (2019). Teachers’ perceptions of self- and peer-identified victims. School Mental Health, 11(0123456789), 819–832. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-019-09329-x

*Dedousis-Wallace, A., Shute, R., Varlow, M., Murrihy, R., & Kidman, T. (2014). Predictors of teacher intervention in indirect bullying at school and outcome of a professional development presentation for teachers. Educational Psychology, 34(7), 862–875. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2013.785385

*Duong, J., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2013). Using the extended parallel process model to examine teachers’ likelihood of intervening in bullying. Journal of School Health, 83(6), 422–429. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12046

*Duy, B. (2013). Teachers’ attitudes toward different types of bullying and victimization in Turkey. Psychology in the Schools, 50(10), 987–1002. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits

*Ellis, A. A., & Shute, R. (2007). Teacher responses to bullying in relation to moral orientation and seriousness of bullying. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77(3), 649–663. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709906X163405

*Fischer, S. M., & Bilz, L. (2019). Teachers’ self-efficacy in bullying interventions and their probability of intervention. Psychology in the Schools, 56(5), 751–764. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22229

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (2010). Predicting and changing behavior : The reasoned action approach. Psychology Press.

*Fry, D., Mackay, K., Childers-Buschle, K., Wazny, K., & Bahou, L. (2020). “They are teaching us to deliver lessons and that is not all that teaching is …”: Exploring teacher trainees’ language for peer victimisation in schools. Teaching and Teacher Education, 89, 102988. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.102988

*Garner, P. W. (2017). The Role of Teachers’ Social-emotional competence in their beliefs about peer victimization. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 33(4), 288–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377903.2017.1292976

*Garner, P. W., Moses, L. K., & Waajid, B. (2013). Prospective teachers’ awareness and expression of emotions: Associations with proposed strategies for behavioral management in the classroom. Psychology in the Schools, 50(5), 471. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits

*Göçmen, N. M., & Güleç, S. (2018). Relationship between teachers’ perceptions of mobbing and their problem solving skills. Educational Research and Reviews, 13(1), 51–59. https://doi.org/10.5897/ERR2017.3404

*Gradinger, P., Strohmeier, D., & Spiel, C. (2017). Parents’ and teachers’ opinions on bullying and cyberbullying prevention: The relevance of their own children’s or students’ involvement. Zeitschrift Fur Psychologie / Journal of Psychology, 225(1), 76–84. https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000278

Gregus, S. J., Rodriguez, J. H., Pastrana, F. A., Craig, J. T., McQuillin, S. D., & Cavell, T. A. (2017). Teacher self-efficacy and intentions to use antibullying practices as predictors of children’s peer victimization. School Psychology Review, 46(3), 304–319. https://doi.org/10.17105/SPR-2017-0060.V46-3

*Grumm, M., & Hein, S. (2013). Correlates of teachers’ ways of handling bullying. School Psychology International, 34(3), 299–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034312461467

*Haataja, A., Ahtola, A., Poskiparta, E., & Salmivalli, C. (2015). A process view on implementing an antibullying curriculum: How teachers differ and what explains the variation. School Psychology Quarterly, 30(4), 564–576. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000121

*Hall, W. J., & Chapman, M. V. (2018). The role of school context in implementing a statewide anti-bullying policy and protecting students. Educational Policy, 32(4), 507–539. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904816637689

*Hall, W. J., & Dawes, H. C. (2019). Is fidelity of implementation of an anti-bullying policy related to student bullying and teacher protection of students? Education Sciences, 9(2), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9020112

*Harger, B. (2019). A culture of aggression: School culture and the normalization of aggression in two elementary schools. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 40(8), 1105–1120. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2019.1660141

*Harks, M., & Hannover, B. (2019). Feeling socially embedded and engaging at school: The impact of peer status, victimization experiences, and teacher awareness of peer relations in class. European Journal of Psychology of Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-019-00455-3

Hawley, P. H., & Williford, A. (2015). Articulating the theory of bullying intervention programs: Views from social psychology, social work, and organizational science. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 37(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2014.11.006

*Hirschstein, M. K., Edstrom, L. V. S., Frey, K. S., Snell, J. L., & MacKenzie, E. P. (2007). Walking the talk in bullying prevention: Teacher implementation variables related to initial impact of the steps to respect program. School Psychology Review, 36(1), 3–21.

*Kahn, J. H., Jones, J. L., & Wieland, A. L. (2012). Preservice teachers’ coping styles and their responses to bullying. Psychology in the Schools, 49(8), 784–793. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21632

*Kochenderfer-Ladd, B., & Pelletier, M. E. (2008). Teachers’ views and beliefs about bullying: Influences on classroom management strategies and students’ coping with peer victimization. Journal of School Psychology, 46(4), 431–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2007.07.005

*Kokko, T. H. J., & Pörhölä, M. (2009). Tackling bullying: Victimized by peers as a pupil, an effective intervener as a teacher? Teaching and Teacher Education, 25(8), 1000–1008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.04.005

*Kollerová, L., Soukup, P., Strohmeier, D., Caravita, S. C. S., Kollerová, L., Soukup, P., Strohmeier, D., Simona, C., & Strohmeier, D. (2021). Teachers ’ active responses to bullying : Does the school collegial climate make a difference? European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 00(00), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2020.1865145

*Lee, C. (2006). Exploring teachers’ definitions of bullying. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 11(1), 61–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632750500393342

*Lopata, J. A., & Nowicki, E. A. (2014). Pre-service teacher beliefs on the antecedents to bullying : A concept mapping study. Canadian Journal of Education, 37(4), 1–25.

MacFarlane, K., & Woolfson, L. M. (2013). Teacher attitudes and behavior toward the inclusion of children with social, emotional and behavioral difficulties in mainstream schools: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Teaching and Teacher Education, 29(1), 46–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2012.08.006

*Marshall, M. L., Varjas, K., Meyers, J., Graybill, E. C., & Skoczylas, R. B. (2009). Teacher responses to bullying: Self-reports from the front line. Journal of School Violence, 8(2), 136–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220802074124

McPheeters, M. L., Kripalani, S., Peterson, N. B., Idowu, R. T., Jerome, R. N., Potter, S. A., & Andrews, J. C. (2012). Closing the quality gap: Revisiting the state of the science (vol. 3: Quality improvement interventions to address health disparities). Evidence Report/Technology Assessment, 208.3, 1–475.

*Menesini, E., Fonzi, A., & Smith, P. K. (2002). Attribution of meanings to terms related to bullying: A comparison between teacher and pupil perspectives in Italy. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 17(4), 393–406. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03173593

*Migliaccio, T. (2015). Teacher engagement with bullying: Managing an identity within a school. Sociological Spectrum, 35(1), 84–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/02732173.2014.978430

*Mishna, F., Sanders, J. E., McNeil, S., Fearing, G., & Kalenteridis, K. (2020). “If somebody is different”: A critical analysis of parent, teacher and student perspectives on bullying and cyberbullying. Children and Youth Services Review, 118(April), 105366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105366

*Mishna, F., Scarcello, I., Pepler, D., & Wiener, J. (2005). Teachers’ understanding of bullying. Canadian Journal of Education / Revue Canadienne De L’éducation, 28(4), 718. https://doi.org/10.2307/4126452

*Naylor, P., Cowie, H., Cossin, F., De Bettencourt, R., & Lemme, F. (2006). Teachers’ and pupils’ definitions of bullying. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 76(3), 553–576. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709905X52229

*Nicolaides, S., Toda, Y., & Smith, P. K. (2002). Knowledge and attitudes about school bullying in trainee teachers. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 72(1), 105–118. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709902158793

*O’Brennan, L. M., Waasdorp, T. E., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2014). Strengthening bullying prevention through school staff connectedness. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106(3), 870–880. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035957

*Oldenburg, B., Bosman, R., & Veenstra, R. (2016). Are elementary school teachers prepared to tackle bullying? A Pilot Study. School Psychology International, 37(1), 64–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034315623324

*Oldenburg, B., van Duijn, M., Sentse, M., Huitsing, G., van der Ploeg, R., Salmivalli, C., & Veenstra, R. (2015). Teacher characteristics and peer victimization in elementary schools: A classroom-level perspective. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 43(1), 33–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-013-9847-4

Olweus, D. (1996). The revised Olweus bully/victim questionnaire. In Bergen, Norway: Research Center for Health Promotion (HEMIL Center), University of Bergen.

*Rigby, K. (2020). Do teachers really underestimate the prevalence of bullying in schools? Social Psychology of Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-020-09564-0

*Roland, E., & Galloway, D. (2004). Professional cultures in schools with high and low rates of bullying. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 15(3/4), 241–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243450512331383202

da Silva, J. L., de Oliveira, W. A., de Mello, F. C. M., de Andrade, L. S., Bazon, M. R., & Silva, M. A. I. (2017). Anti-bullying interventions in schools: A systematic literature review. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 22(7), 2329–2340. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232017227.16242015

*Skinner, A. T., Babinski, L. M., & Gifford, E. J. (2014). Teachers’ expectations and self-efficacy for working with bullies and victims. Psychology in the Schools, 51(1), 72–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21735

*Sokol, N., Bussey, K., & Rapee, R. M. (2016). Teachers’ perspectives on effective responses to overt bullying. British Educational Research Journal, 42(5), 851–870. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3237

*Strohmeier, D., Solomontos-Kountouri, O., Burger, C., & Doğan, A. (2021). Cross-national evaluation of the ViSC social competence programme: Effects on teachers. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 18(6), 948–964. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2021.1880386

*Sultana, M. A., Ward, P. R., & Bond, M. J. (2020). The impact of a bullying awareness programme for primary school teachers: A cluster randomised controlled trial in Dhaka. Bangladesh. Educational Studies, 46(1), 106–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2018.1536877

*Swift, L. E., Hubbard, J. A., Bookhout, M. K., Grassetti, S. N., Smith, M. A., & Morrow, M. T. (2017). Teacher factors contributing to dosage of the KiVa anti-bullying program. Journal of School Psychology, 65(August 2016), 102–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2017.07.005

*Tucker, E., & Maunder, R. (2015). Helping children to get along: Teachers’ strategies for dealing with bullying in primary schools. Educational Studies, 41(4), 466–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2015.1043980

*van Aalst, D. A. E., Huitsing, G., Mainhard, T., Cillessen, A. H. N., & Veenstra, R. (2021). Testing how teachers’ self-efficacy and student-teacher relationships moderate the association between bullying, victimization, and student self-esteem. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 18(6), 928–947. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2021.1912728

*van der Zanden, P. J. A. C., Denessen, E. J. P. G., & Scholte, R. H. J. (2015). The effects of general interpersonal and bullying-specific teacher behaviors on pupils’ bullying behaviors at school. School Psychology International, 36(5), 467–481. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034315592754

*van Verseveld, M. D. A., Fekkes, M., Fukkink, R. G., & Oostdam, R. J. (2020). Teachers’ experiences with difficult bullying situations in the school: An explorative study. Journal of Early Adolescence. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431620939193

van Verseveld, M. D. A., Fukkink, R. G., Fekkes, M., & Oostdam, R. J. (2019). Effects of antibullying programs on teachers’ interventions in bullying situations. A Meta-Analysis. Psychology in the Schools, 56(9), 1522–1539. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22283

Veenstra, R., Lindenberg, S., Huitsing, G., Sainio, M., & Salmivalli, C. (2014). The role of teachers in bullying: The relation between antibullying attitudes, efficacy, and efforts to reduce bullying. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106(4), 1135–1143. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036110

Volk, A. A., Veenstra, R., & Espelage, D. L. (2017). So you want to study bullying? Recommendations to enhance the validity, transparency, and compatibility of bullying research. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 36(June), 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2017.07.003

Wells, G. A., Shea, B., O’Connell, D., Peterson, J., Welch, V., Losos, M., & Tugwell, P. (2013). The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality if nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. In BMC Public Health201313:154 (pp. 1–17).

*Williford, A. (2015). Intervening in bullying: Differences across elementary school staff members in attitudes, perceptions, and self-efficacy beliefs. Children & Schools, 37(3), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1093/cs/cdv017

*Williford, A., Depaolis, K. J., & Colonnieves, K. (2021). Differences in school staff attitudes, perceptions, self-efficacy beliefs, and intervention likelihood by form of student victimization. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 12(1), 83–107. https://doi.org/10.1086/713360

Yeager, D. S., Fong, C. J., Lee, H. Y., & Espelage, D. L. (2015). Declines in efficacy of anti-bullying programs among older adolescents: Theory and a three-level meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 37(1), 36–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2014.11.005

*Yoon, J. (2004). Predicting teacher interventions in bullying situations. Education & Treatment of Children, 27(1), 37–45.

Yoon, J., & Bauman, S. (2014). Teachers: A critical but overlooked component of bullying prevention and intervention. Theory into Practice, 53(4), 308–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2014.947226

*Yoon, J., Bauman, S., Choi, T., & Hutchinson, A. S. (2011). How South Korean teachers handle an incident of school bullying. School Psychology International, 32(3), 312–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034311402311

*Yoon, J., & Kerber, K. (2003). Elementary teachers’ attitudes and intervention strategies. Research in Education, 69, 27–35. https://doi.org/10.7227/RIE.69.3

*Yoon, J., Sulkowski, M. L., & Bauman, S. A. (2016). Teachers’ responses to bullying incidents: Effects of teacher characteristics and contexts. Journal of School Violence, 15(1), 91–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2014.963592

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Beau Oldenburg and Eleonora Marucci for assisting in selecting papers for this review.

Funding

This study was funded by an NWO Vici to R. V. (453–14-016) and an NWO Veni to G. H. (451–17-013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.v.A. designed and executed the systematic search, and wrote the paper. G.H. and R.V. collaborated in the writing and editing of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Highlights

• Despite increased attention for bullying, little research exists on teachers’ roles.

• The research field has selective samples and lacks sufficient generalizable studies.

• Research would benefit from using consistently validated instruments.

• The Theory of Planned Behavior succinctly classifies research on teachers’ roles.

• Teachers’ self-efficacy and perceived subjective norms were limitedly investigated.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

van Aalst, D.A., Huitsing, G. & Veenstra, R. A Systematic Review on Primary School Teachers’ Characteristics and Behaviors in Identifying, Preventing, and Reducing Bullying. Int Journal of Bullying Prevention 6, 124–137 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-022-00145-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-022-00145-7