Abstract

Using data from various sources, this paper discusses the recently documented below replacement level fertility in India in the context of the universality of marriage of girls, most of which are arranged by the parents, and increase in their mean age at marriage, mainly due to decrease in child marriage. There is virtually no increase in divorce rate, cohabitation, or voluntary childlessness, except for some anecdotal evidence from metro cities. The paper shows that the transition to small family in India is not due to cultural shifts towards post-modern attitudes and norms that accept and stress individuality and self-actualization. It is largely due to high aspirations among urban middle-class parents for children which can be fulfilled when they have one or at most two children in view of the rising cost of private English medium education and health care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introducion

At the turn of this century, almost all countries around the world have witnessed transition from high to low birth and death rates. This has been termed as First Demographic Transition (FDT). It generated a large body of literature in several countries that examined the levels, pace of change or trends and determinants to explain how the transition has occurred as well its consequences for social, economic and political developments (Bongaarts, 2009; Canning, 2011; Casterline, 2003; Dyson, 2010; James, 2011; Reher, 2011). The FDT started first in the Western European countries more than a century ago where the drivers of change were broadly identified as industrialization, urbanization and modernization. In response to public health measures most children born survived that led parents to want or desire fewer children. These resulted initially in high population growth rate and with some lag changed the age structure of the population (See: Notestein, 1945; Coale, 1973; Cochran & O’Kane, 1977; Blanc, 2020). Beyond Western European region, with some time lag, several other countries in other regions of the world also experienced similar changes in their populations. Most analyses, if not authoritatively concluded, opined that at the end of the FDT total fertility level that reached replacement level will continue within a narrow range hover around it for years to come and the populations of most countries and eventually of the world will stabilize with total fertility rate ranging between 1.7 and 2.1(United Nations, 2017).

However, as some scholars noted, that was not the end of the story of the demographic transition. In the same European countries where FDT started, fertility continued to fall well below the replacement level and many different living arrangements outside formal or legal marriage began to occur. A significant proportion of women and men choose and continue to remain legally unmarried; some opting for live in relationship or cohabitation without formalizing it in marriage. Some unions decide voluntary childlessness but some choose to have children. High rate of divorce among those who undergo formal marriage and dissolution of cohabitation become widespread and acceptable. Researchers like van de Kaa and Lesthaeghe documented these developments in Western European countries like France, Germany, and Sweden and termed them as Second Demographic Transition (SDT) in several of their publications (See: Lesthaeghe, 1995; Lesthaeghe & Surkyn, 2008; Lesthaeghe, 2010; van de Kaa, 1987). According to them the primary drivers of these changes are cultural shifts towards post-modern attitudes and norms that accept and stress individuality and self-actualization. The identifiable features of SDT thus are: below replacement fertility including voluntary childlessness among some couples, rise in age at marriage, rise in prevalence and acceptance of premarital cohabitation and change in values that tolerate and even emphasize individualism.

While recognizing that not all characteristics will occur in all societies simultaneously, the authors and advocates of the SDT believe that transformations will take place in different measures in many other countries as they embark on or go through the SDT. The cultural contexts of the countries would be important – in the short or medium term – but globalization along with the all-pervasive technological revolution as well as contraceptive revolution will eventually lead to some sort of homogeneity in the pattern across several countries. East Asian countries such as Japan, South Korea exhibit some characteristics of SDT in terms of significant proportion of women (and men) remains single or not marry and where total fertility rate has reached significantly below replacement level. However, there is very little evidence of cohabitation (Atoh et al., 2004).

I explore in this paper where India stands with regard to SDT. Using data from various sources, I discuss the recently documented below replacement level fertility in the context of the increase in mean age at marriage, no increase in divorce rate, and very limited evidence on cohabitation, and on voluntary childlessness. Given the fact that India is very heterogeneous in terms of religions, languages, caste affiliation, etc. it is difficult to generalize for the country as a whole, and so wherever possible regional diversities will be highlighted.

2 Decline in fertility in India

The transition to small family or steady decline in fertility is evident in India, as gleaned from the annual data compiled by the Sample Registration System (SRS) from around 1970 onwards and the periodic surveys conducted by the National Family Health surveys (NFHS) since 1992–93. The total fertility rate (TFR) for the country as a whole has declined from 3.6 in 1991 to 2.4 by 2011 and according to the NFHS-5 conducted in 2019–21, it is now 2.0 children per woman. The decline in fertility was recorded in both rural and urban areas as well as by all the states of the country. Further, barring two large states of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh in North India and three small states (Jharkhand, which was part of Bihar until 2000, Manipur and Meghalaya) all the states have achieved a replacement or below replacement level fertility. The contours and the pace of fertility decline and the consequent demographic transition have been documented by several researchers (See: Bhat 2002; Dreze & Murthi 2001; Guilmoto & Rajan 2005; Visaria and Visaria (1994) and Visaria 2004). The steady and continuous fertility decline has been hailed by many as India making a history in its demographic transition.Footnote 1

A number of empirical studies as well as those analyzing secondary data from the Indian Censuses, and the National Family Health Surveys have attempted to explain the factors responsible for the increased pace of decline in fertility in the last 20 years thereby nearly completing the four phases of the first demographic transition.

Since TFR is a period measure and measures fertility of women in all the ages of their reproductive span, it is important to examine the data on the number of children ever born to women who have completed their fertility. It reflects fertility in the past and is not a current measure, but gives an indication of family formation of Indian women over time and changes therein. Available data from the five NFHS surveys, conducted between 1992–93 and 2019–21, shown below in Table 1, clearly indicate that both the TFR and children ever born (CEB) to women who have completed their reproduction (women aged 40–44 years) have declined by close to 40 percent in almost three decades. While it is important to note that 40–44-year-old women in 2019–21 with an average of 3 children born to them were in peak reproductive period almost 20 years ago and would have been influenced by the prevailing fertility norms, ethos of that time including the family program policies and services. The Table also shows that in 1992–93, almost 60 percent of currently married women aged 15–49 years with two living children reported that they did not want any more children; by 2019–21 there were 86 percent women with two children who did not want any more children. Evidently, two-child norm has spread in India among majority of women. This implies that that the current cohort of women in their prime reproductive phase will very likely have fewer than three children at the end of their childbearing age.

Demographers and other social scientists attribute this decline in fertility to a number of factors. They range from increase in age at marriage, easy access to family planning methods, decline in infant and neonatal mortality, improvement in wealth status, urban way of living, increase in the level of education among women, increase in women’s participation in employment, etc. Some of these are distal factors that affect fertility through the proximate determinants. In the Indian context, it is important to examine the role of marriage to understand its contribution to fertility and in the context of SDT since marriage is the most important determinant of the reduction in fertility from the biological maximum. Applying the Bongaart’s proximate determinants of fertility model to the NFHS data for 2015–16, Singh et al. (2022) estimated that in India marriage contributed 36 percent reduction in fertility. As shown in Table 2, the singulate mean age at marriage of women increased from about 18 years in 1981 to close to 21 years in 2011. The percentage of single girls in the age group 15–19, increased from 56 in 1981 to 80 in 2011 and that of girls aged 20–24 more than doubled from 14 to 31 during the same period. The steady increase in the average age at first marriage and increase in the proportion of girls in the age group 15–24 remaining single is due to a multitude of factors such as the enactment of law banning girls to marry before age 18, increase in city living, policy of compulsory education to all children including girls until age 14, availability of schools up to grade 8 in almost all villages, etc.Footnote 2

Widespread messaging of family planning, using the IEC (information, education, communication) measures throughout the country has made Indians even in the remotest parts aware that fertility can be controlled. India’s national family planning programme was launched in 1952, and within a few years, it was incentivized and continues to be so.Footnote 3 Promotion of family planning services by the Indian government has played an important role in increasing contraceptive use and thereby lowering the level of fertility. Along with that factors such as increasing urbanization, off-farm employment, the possibility of rising returns on educational investments in children have been important factors in promoting the small family norm. Abortion has been legal in India since 1971 and approval of medical abortion in 2002 has further enabled Indian women to terminate their unwanted pregnancies. According Singh et al. (2022), based on 2015–16 NFHS data, contraception and abortion contributed around 24 percent to the fertility reduction.

Factors like reduction in child mortality, increase in education and reduction in poverty, or increase in income, etc. termed as distal factors, contribute to lowering fertility and operate through the proximate determinants. Mohanty et al. (2016), after detailed analysis of district level data available from the surveys for 1991 and 2001, found that increased educational attainment and improved child survival continues to be the major drivers of fertility reduction but family income was not. The widespread adoption of contraception by illiterate women, as shown by multilevel analysis by McNay et al., (2003) and Arokiasamy, (2009), suggests that the diffusion of new ideas and aspirations for the children are spreading among poor or illiterate thereby narrowing the differences between them as discussed later.

3 Institution of marriage in India

While increase in the age at marriage of Indian women has been strongly associated with decline in fertility, it is important to examine how the institution of marriage itself is undergoing changes to usher the SDT. At the outset it must be pointed out that marriage of women (and also of men) has remained universal in India. Ever since data from the Indian Censuses have become available over century and a half, it has been observed that marriage of women is near universal. According to the latest available data from the 2011 Census, more than 98 percent of Indian women were married by age 35; with very small difference between urban (97.3%) and rural (98.6%) areas (Bhagat, 2016). Some north–south differences in the proportion of women married have existed especially at younger ages. For example, according to the 2011 Census data, in the age group of 25–29 years, nearly 15 percent of women in the southern state of Kerala were single as against just 5 percent of women in the northern state of Bihar. Most marriages in India even today are arranged by the parents who are obligated to ensure that every child is married and does so at a fairly early age and fulfil their responsibility. The characteristics of Indian marriage system that are relevant or have bearing on fertility changes that are discussed here are the age at marriage, selection of spouse, possibilities and mechanisms of divorce and widow remarriage.

Historically the age at marriage in India was very low and most girls were married before attaining puberty. The enlightened Indian reformers and others vehemently opposed such a practice. As early as 1929, the Child Marriage Restraint Act was passed that fixed the minimum age at marriage for girls at 14 years and for boys at 17 years. The Act was amended in 1978, raising the marriage ages of girls and boys to 18 and 21 respectively. The mean age at marriage of women slowly increased from 16 years estimated from the 1961 Census age data to close to 19 years by 2011.Footnote 4 However, despite the Act, the NFHS-4 survey conducted in 2015–16 noted that among the 18–23-year-old currently married women, 21 percent were married before age 18 (Kumar, 2020).Footnote 5 In the 25–29 age group of women, a third of women had got married before age 18. Early marriage has been a persistent phenomenon of states such as Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand and West Bengal.

There is some evidence of age at marriage of women having increased in recent years in response to several factors. A number of studies undertaken using large survey data such as those available from the National Family Health Surveys (five surveys over nearly 30 years) and other regional studies have focused on exploring the correlates of age at marriage of women in India. Factors such as pursuit of higher education by women, engaging in gainful employment, higher wealth status or caste of the household, living in metropolitan cities and in southern states (except for Andhra Pradesh) are found to be statistically significant in explaining postponement of marriage of girls (See: Das & Dey, 1998; Dommaraju, 2009; Subramanian, 2008; Kumar, 2020). These factors have influenced the age at marriage but the primary reason for increase in average age at marriage of Indian women is the decline in child marriages. There is virtually no evidence that the near universality of marriage has been dented in spite of increasing urbanization or modernization of the Indian society.

In a situation where marriage is universal and arranged, endogamy becomes the mode of spouse selection. Parents select spouse from within the same caste and kinship group.Footnote 6 Even many of the advertisements in the newspapers or on the matrimonial sites, which are being used by parents as well as by individuals themselves living in metro cities, clearly state the sub-caste within which the alliance is sought. Using a large data set of individuals who placed matrimonial advertisements in local dailies in West Bengal, Banerjee, et al. (2013) found a strong preference for within caste marriage. By following some of the families of those whose advertisements appeared in the newspapers, the authors found that the preference was because marriages within the same caste were socially and economically advantageous to both the partners.

According to the nationwide India Human Development Study (IHDS) conducted in 2004–05, less than five percent of the respondent women had a role in choosing their husbands, although nearly two thirds felt that they were consulted in the decision (Desai & Andrist, 2010). The content and quality of consultation and consent are often unstated or remain vague. Presumably, those boys and girls who are well educated – with college education or educated at least up to high school – have a greater voice in approving or disapproving the potential partner identified by parents or family. Anecdotal evidence suggests that inter-caste marriages, which are recognized by law, and which would be outside the purview of families or close kin-group, do take place in India’s urban areas among highly educated people, although they constitute a very small proportion of the total number of marriages and many couples tend to face strong opposition from the kin network. Family ties with such couples become weak and often times they are barred from caste-based social events.

Further, marital dissolution through divorce or separation in India has been rare. As per the 2011 census, less than one percent of married women were divorced or separated and this proportion has been remarkably stable over the last four decades (Jacob & Chattopadhyay, 2016). Based on the third District Level Household and Facility Survey (DLHS-3) conducted in 2007–8, where a question was asked to all the women their current marital status and for those currently widowed, separated, divorced or deserted the duration of their current marital state, Dommaraju, (2016) estimated that about 2 per cent of all marriages in India end in divorce or separation within 20 years of marriage. The rate ranged from around four percent in Northeast states and less than one percent in the northern states. These differences are likely to be due to differences in kinship and marriage systems, and status of women in the two regions. Interestingly, women with higher education as well as those with at least one son had the lowest risk of divorce or separation compared to those with lower levels of education or with no children.

In India different religious groups have their own marriage and divorce related laws and additionally there are also customary laws enforced by several caste organizations. This plethora of laws make it difficult to enforce uniform codes by the Indian judicial system.Footnote 7 Given the fact that it takes a long time for divorce cases to be tried and resolved in the Indian courts, some opt for separation if there is no intention to remarry or seek divorce using the caste-based customary laws. The reasons for not approaching courts for legal separation or divorce are that they are perceived as being ineffective and inefficient, costly, and complex and out of reach of many.

However, recently Lesthaeghe, (2010) has more or less accepted that societies which are predominantly Hindu and Muslim are unlikely to undergo changes in marriage patterns soon because marriage continues to be stubbornly universal and marriages are arranged by parents or members of close kin networks. Scholars like James and Srinivasan, (2015) also opine that the larger network of family, caste and religion are important determinants of marriage in India and these act as hinderance to the rise of individualism needed to break away from their hold and choose marriage across religion or linguistic group or geographical boundaries as well as opt for non-marriage or other forms of living arrangements. In fact, they term the stability in the marriage institution of India as ‘golden cage’. According to the theory of SDT, changes in the union formation are prerequisites for the transition and for changes in the levels of fertility. It is therefore important to examine whether, what type of and to what extent changes in marriage and family formation patterns are occurring in India in recent years.

3.1 Is the Institution of marriage likely to change in future?

There is a definite decrease in child marriage in India and a steady increase in age at marriage. India may in coming years witness small increase in non-marriage (the factors for it may range from failing to find the right partner at right time to familial responsibility). A very slow increase in non-marriage among girls in India—mostly among those having well-paid jobs commensurate to their level of education and living in metro cities—is anecdotally documented by women’s popular magazines. Data compiled on nearly 3000 urban single women above the age of 35 from all walks of life and living in major cities suggest that majority of these women make their own choices when it comes to career, dating and sex, and battling stereotypes (Kundu, 2018). The author however points out that these women, whether single by choice or circumstance, are under scathing societal pressure, invasive scrutiny and persistent criticism. In other words, being single in a country where the highest validation of one’s gender remains marriage and motherhood, is a constant struggle for single women. Also, majority of the metro-girls, in spite of the visible emancipation from patriarchy, continue to be rooted in their own families and kin networks for social and moral support despite having friends at workplace and social network outside family.

If choosing to remain single is rare in India, cohabitation with a person of opposite sex is even rarer. It is however likely that it may be gaining popularity in recent times as marriage age increases along with education and well-paid employment among both men and women. Under the Indian law live-in relationship with person of opposite sex is not illegal between consenting adults who enter into a relationship mutually and is thus not a criminal offence. The Indian court views such relationships ‘in the nature of marriage’ if the relationship is between two unmarried individuals. However, according to some state high courts, that perceive a live-in relationship between a married and an unmarried person as illegal, unacceptable, and therefore view it as destroying the country’s ‘social fabric’.

Even rudimentary data are not available on how many Indian men and women choose live-in relationship because there is rarely an open acknowledgement of it. Indian society is not yet open to the idea of live in relationship because it is perceived as immoral in which a woman loses her virginity (pre-marital sex is totally unacceptable) and thus does not adhere to the traditional idea of what constitutes a socially accepted conjugal couple (Narayan, et al. 2021). Anecdotal cases of few couples in live-in relationship, brought before the courts in India have dealt with issues such as granting protection to couples, financial arrangements, granting legal status to children born of such union, etc. In reality any type of live-in relationship in India continues to be socially taboo, unacceptable and rare.Footnote 8

Cohabiting partners who have openly acknowledged their relationship, on the other hand, have indicated that their belief in gender equality, mutual respect, compatibility, and no need of dowry giving or receiving have encouraged them to enter in live-in relationship. It is too early to know whether greater number of young metro-couples will try out this form of relationship and for what duration before legally marrying.

In a nutshell, unlike in the Western societies where marriage or union formation is a personal behavior involving individual choice, in India, families play an important role in the marriage process and the role of the marrying individuals in the negotiations process is often very limited. Adherence to the caste boundaries, rules of endogamy (including hypergamy), and giving or receiving of dowry influence the negotiations between families. Some small changes are evident with the spread of education, urban living, but even today only a small fraction of couples make their own choice of partner. Cohabitation, live-in relationship or opting for single living that are becoming the new norms in many developed societies are unlikely to become widely acceptable in the complex, multi-layered caste hierarchies of the Indian society in the near future. Given the hold of the extended kinship system on families, the individual-centered behavior is unlikely to become widespread in India. In spite of the rising aspirations and consumerism evident in recent years among the Indian urban middle classes, the hold of social institutions like caste and community remains quite strong on individual behaviors, particularly with regards to marriage decisions and gender roles. Also, the price for deviation in terms of security, support is too high to pay for most people.

4 Drivers of fertility decline

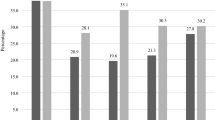

Evidently, the steady decline in fertility in India, noted above, is not due to increase in the eventual proportion of unmarried women in the population, which is very small. But at young ages of 15–19 and 20–24 years, fertility has declined, as evident in Fig. 1, rapidly between 1991 and 2019 because of the decrease in the proportion married at ages 15–19 and 20–24. From close to 4 out 10 adolescent girls who were married in 1991, the percent declined to 12 in 2019–21. Even in the age group 20–24, the decline in the proportion of girls married was from close to 80 in 1991 to 60 by 2019. The fertility decline among the older women is largely due to increase in the use of contraception by married women.

The marital fertility has declined from close to 5 children just 30 years ago in 1991 to 3 children today. As Fig. 2 shows, marital fertility at younger ages has hardly decreased.Footnote 9 In India, newly married women are expected to begin childbearing soon after marriage, although as the analysis of NFHS data from the 2015–16 survey indicated that nearly a quarter of 15–19-year-old married women would prefer to wait two or more years before having their first child (Ibarra-Nava et al. 2020). A sample survey carried out in six Indian states in 2006–07 also found that 51 percent of women aged 15–24 who were married for five or fewer years would have preferred to postpone their first pregnancy. However, only 10 percent used contraception to avoid becoming pregnant (Jejeebhoy et al. 2014). Newly married adolescent girls in India have low status in their marital family and are rarely able to negotiate delaying their first pregnancy. Once the women have had their desired number of children, and very likely if at least one of them is a male child, they opt for permanent method of contraception. For majority of the women the first and the only method of contraception is female sterilization. A few studies have shown that in states like Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu fertility is compressed in six to seven years between 20–29 years of age (Padmadas, et al. 2004).

4.1 Childlessness

When total fertility rate has come down recently to 2 children per woman for the country as a whole as per the NFHS-5 data, two questions need examination. Is the percent of women opting for one child increasing? Is some proportion of couples opting out of having any children? If there is some evidence of these, the related issue needing exploration is what has changed at individual or societal level for such ideas to take some root in a patriarchal child-centric Indian society? Table 3 gives an indication of change, as evident from the five NFHS surveys, in percent of currently married women with no children or just one child (of either sex or male or female child shown separately) who indicated that they do not want any more children and percent of women who adopted sterilization.

The question related to SDT is whether women in India are choosing to opt out of having any children. The willful or voluntary childlessness among those who are married (and equally having a child by women who are never married) is totally unacceptable in India of today. In any population a small percentage of childlessness exists as a result of involuntary infertility. Additionally, a certain percentage of women do conceive but their conceptions result in miscarriage and is thus childless. According to some researchers in India about 7 percent of currently married women are childless and 2.5 percentage of them experience involuntary childlessness or natural sterility (Agrawal et al., 2012; Ganguly & Unisa, 2010).

About 2 percent of women who had no child but reported that they did not want to have any children in the decade of 1990s, as shown in Table 3, is more a reflection of involuntary childlessness and women accepting the fact that they cannot have children due to some health issues and/or conception resulting in miscarriage. An increase in this proportion to 4 or 5 in the recent period could include some women who chose voluntary childlessness state. However, only around one-half of a percent of childless women opted for sterilization; some might have done so on medical advice because of facing serious health problems.

Overall, in a traditional patriarchal Indian society, where majority of the marriages are arranged, the familial pressure on women to conform to traditional family scheme of having children is very great. A sample survey conducted in the city of Kolkata in 2014, found that none of the women who did not have any living children at the time of survey reported that they did not want a child in future (Ghosh, 2015). The couples felt that their aspiration of personal achievements and self-fulfillment would be hampered if they did not have children. A small survey of about 50 women conducted in 2013 in Delhi, who chose not to have any children, opined that motherhood is not the only most fulfilling aspect of a woman’s life. According to them pursuit and achieving of higher education is equally fulfilling because it opens up horizons for them to many more ways of finding meaning and purpose in life. Some think that the modern urban highly educated women, exposed to the ethos of the western world articulate their language and ape the western ways of life including freedom from child bearing and rearing.

Many couples who choose childfree life are subjected by family members, friends and acquaintances to several questions such as how would they cope with loneliness in old age and with challenges that they would face with deterioration in their health, etc. However, a trend is visible that with nuclearization of families many couples (or just one surviving member) with well-educated children have to take care of themselves in old age because the children have moved away for employment. This trend is becoming evident in India and so some childless couples argue that having children is no guarantee of old-age support. Although the number of childfree couples is very small in India, some of them seem to be able to exercise their choice and derive support from their immediate social groups. A new kind of support groups such as Childfree by Choice – India are slowly coming up in metro cities like Bengaluru and Delhi. It remains to be seen whether such groups spread to other cities and their membership increases.

4.2 Single child families

What is becoming more widespread in India is the single-child family as shown in Table 3. The percent of currently married women aged 15–49 with one child only reporting that they do not want any additional children doubled from 15 to 31 percent between 1992–93 and 2019–21. The son-preference is evident but it is important to note that close to a quarter of women with just one daughter indicated that they did not want any additional child. Even the acceptance of sterilization among women with one child has also more than doubled during the same period from 4 to 8 percent. Again, one cannot rule out factors such as secondary sterility, some women having to undergo medical procedures that prevent future pregnancy, etc. that may be responsible for not having additional children. To a survey question they may describe their status as not wanting any more children.

Nonetheless, the doubling of the percentage of couples with one child not wanting any additional child in less than three decades is indicative of changes in the values, preferences and norms of the Indian society and has received attention from scholars, media, etc. This change is even more evident in big cities where associated with it are factors such as higher status and employment of women, liberalized abortion laws and availability of improved contraceptives that help women to stop with one child if they choose to do so. According to a sample survey undertaken in Kolkata, 65 percent of women with one child did not want to have any more children (Ghosh, 2015). In the Indian context, as is the case in East Asian countries like Japan, South Korea, rising cost of good quality education for the children is increasingly articulated by women for not able to afford even two or three children. A few quantitative and qualitative studies have been undertaken to understand the contribution and role of single child family to the declining fertility in India.

In Table 4 the change in one and a half decade between 2005-16 and 2019–21 among women with one or two living children who reported that they do not want any more children is shown by their socio-economic characteristics. Three important points emerge from these data. One, in the 15-year period, the percent of women wanting only one child has increased among all women regardless of their socio-economic background. Two, a higher percentage of women belonging to socially and economically better off groups reported not wanting more than one child compared to their sisters belonging to lower or disadvantaged groups. Three, the differences observed with regard to wanting no more than two children observed between the two groups of women in 2005–06, virtually disappeared by 2019–21. Regardless of their station in Indian society – whether rich or poor, whether illiterate of highly literate, etc. – 85 plus percent of women do not want more than two children. This is a remarkable convergence of the two-child family norm in a heterogenous country, which is proud of its plurality. The only two exceptions to this are: as against 87 percent of Hindu women not wanting more than two children, 73 percent of Muslim women reported this. Some son preference persists as evident by the fact that against 89 percent of women with one living son not wanting more than two children, 65 percent of those who have no son reported that they do not want more than two children.

With the analysis of nation-wide data as part of the India Human Development Study (IHDS), conducted in 2004–06, Basu and Desai, (2010) noted that incorporation into global culture through English language skills and less traditional gender roles seem to be associated with the spread of one child family in India. A study by ASSOCHAM, (2008) found that young parents from middle and upper-class felt that the cost of children’s education has risen disproportionately compared to their own income, and the increasing cost of educating children has deterred them from having more children. In fact, as many as 35 percent of working mothers with one child in metro cities who were interviewed as part of the study did not wish to have a second child. After comparing families of different parities from the IHDS survey, Basu and Desai, (2016) noted that one-child families were found more in metro cities, and belonged to upper caste and economic class. They opined that small families, by investing more in the education of few children, would be able to achieve greater social mobility. Equally important was the finding that 40 percent of the families who stopped at one child did so in spite of the child being a daughter. Evidently, the proverbial strong son-preference among Indians is weakening among couples who opt for one child.

It may be noted that in spite of India’s Right to Education Act of 2009, which clearly states that school education up to the age of 14 years would be free and compulsory for all children, provision of education has become expensive in both rural and urban areas as estimated by Chandrasekhar and Ghosh, (2020) from the data from the 75th National Sample Survey Organization conducted in 2017–18. This is because other costs associated with schooling — such as textbooks, uniforms, transport, private tuition —add to the financial burden of the households. The cost of education in private schools is much higher compared to that in government schools. But in view of the perception that the private schools provide better quality education, even rural lower middle-class parents are willing to spend a significant proportion of their earnings on their children’s education with a hope that good education will provide secure and preferably urban employment and in turn improve the economic as well as social status of the family. Having fewer children helps in investing more resources in them.

This transition from multiple children or even two children to just one child is attributed to rising aspirations of Indian couples and more particularly of women. The aspirations can be for self as well as for the child. In the European countries the days of Child King may be over and replaced by Couple King. But in India among the urban and upwardly mobile couples Single Child King appears to becoming popular and even acceptable.Footnote 10 Parents can aspire to provide the child good quality education in English medium school, private tuition, send for extra-curricular activities for well rounded development. Eventually, when grown up, the child would be assured a well-paid job; a dream of the parents. Based on the analysis of IHDS 2004–05 survey, Basu and Desai, (2016) state that the emergence of one child family in India is not due to aspirations of personal freedom that it would provide to parents. But it is due to increasing opportunities for well-paid employment opening up in India and the urban educated aspiring to make them accessible to their child by investing in his/her education and well-rounded development.

In Tamil Nadu state in south India where fertility fell to replacement level several years before it did elsewhere in the country, according to a few qualitative studies undertaken in the state during the 1990s, the decline was due to the rising aspirations of young couples who wished to provide better education and health care to their children compared to what they themselves received as children. Also, the studies reported that there was an awareness among rural couples with several children that land gets divided between them to such an extent that the small parcel of land that each son inherits becomes unviable for cultivation and survival. Therefore, couples desire fewer children. To bridge the gap between increasing aspirations and expectations and the limited resources to meet the aspirations, some couples resort to permanent method of contraception and limit the number of children. Nagaraj, (1999) terms this as social capillarity, meaning that the idea of and awareness about the small family norm will spread.

By restricting to having just one child, women are able to achieve socially valued motherhood goal (Pradhan & Sekher, 2014); and thereby avoid being subjected to criticisms from the immediate and extended family of being barren or selfish. At the same time women can have time on hand to pursue activities, career, employment etc.

5 Is India poised to enter the second demographic transition?

Undoubtedly there is a big shift in India in the past two to three decades in fertility level; from an average of more than three children a woman gave birth to in the early 1990s, TFR has come down to 2. In the 1990s having more than three children was an acceptable social behavior. The extended family contributed in several ways to bringing up the children. This pattern of bearing and raising children now has changed in urban India and is also increasingly changing in rural areas. The number of children born to a woman has come down throughout the country and rural–urban, inter-state differentials that were much discussed, analysed and studied as the country was going through the First Demographic Transition are less and less important. In spite of the much-admired diversity of the nation in terms of religions, languages, food habits, and cultural artifacts, its demography is inching towards some sort of convergence as shown in Table 4 above.

To a hypothetical question on the ideal number of total children asked to the respondents in NFHS -5, the overall estimate for India as a whole was 2.1, with slight preponderance for a male child. Among the major states, the response ranged between 1.8 and 2.1. Women from Bihar and the neighbouring Jharkhand state reported the ideal number as 2.5 and 2.4, respectively. The actual behavior can diverge from the ideal, but the convergence in ideal number of children wanted is also remarkable. Evidently the decline in fertility has continued in this century and the current TFR level a tad below replacement of 2.1 has led to explore whether the country is poised to enter into the second demographic transition.

According to the architects of the Second Demographic Transition, the reproductive behavior is merely an outcome of the spread of individualism, shift to self-actualization, tolerance to and acceptance of diversity of lifestyle choices. If in the process childlessness spreads and the TFR falls very low in the countries that have accepted the ideational changes and, in the process, have altered the traditional marriage and family structures, so be it. In this paper, I have examined available evidence on whether and in what ways the pillars of Indian society – marriage and family – are undergoing changes in recent years. The related exploration is whether the ingredients identified by the authors of SDT—changes in attitudes and values leading to changes in families and relationships, are found in some measure in India and likely to drive SDT.

Our analysis of marriage data and practices show that in India kinship and family ties continue to be important even today for majority of the people and they govern several decisions including those of when and whom to marry, when to have children and also how many. What has changed over time is decrease in child marriages and the commensurate increase in the average age at marriage. Marriage in India is a relationship between two families much more than between two individuals. Non-marriage for women (also for men) is not a choice in the arranged system. Unless a significant number of people free themselves from the deeper influence of these ties and develop other networks, the characteristics of SDT witnessed in western European nations are unlike to evolve in India in near future. Overall, marriage as a social institution is very likely to remain the dominant arrangement in India. Also, there is little evidence as yet that non-marriage among women will increase much.

Family will also remain as the nucleus of social organization and govern the social behavior of members. India will evolve its own path to SDT where individualism or personal fulfilment would not govern family formation decisions but limited data suggest that extraneous factors such as aspirations to provide English medium education to children may influence the decision on having just one child. Given the huge increase in the cost of private English medium education, middle class upwardly mobile couples feel that they cannot afford to provide it to even two or three children. Basu & Desai (2016), have opined, based on the primary data collected in the IPDS survey, that low fertility or stopping at one child in India is because parents value children highly.

The single child families are likely to spread in coming years, especially in metro cities as evidenced by the fact that almost a third of women with one child (of either sex) report that they do not want another child. Also, the factors underlying for opting for a single child – ambition to rise professionally, difficulties of getting domestic hired or parental support, nuclearization of families, cost of good quality private education—are becoming apparent in urban areas and strengthen the decision to stop at one child. At the same time, not having a child at all is not an option that Indian women consider in the realm of a possibility, except for very few. It is likely that those who voluntarily opt for childlessness rarely openly acknowledge that this is an informed choice that they have made. Assertion of their individualism and empowerment tends to be limited to their immediate non-familial social circle.

While in daily life the influence of the extended kinship system is decreasing in India, its importance at the time of marriage, and spouse selection is very much evident. Along with rising aspirations and consumerism in recent years among the Indian middle classes, the hold of social institutions like caste and community continues to remain fairly strong on individual behaviors. Thus, India enters the second demographic transition phase, carving its own path of retaining marriage as an intact institution, but allowing, accepting or reluctantly tolerating singlehood some women may choose. It appears having one living child will become more widespread among middle class households and raise the child by providing private education, all the amenities that the parents can afford, including sending abroad for higher education or employment. After almost three decade long one-child policy, strictly implemented in China, the response to its reversal and allowing couples to have two and very recently three children, among Chinese couples is very lukewarm. Factors such as lack of affordable public childcare, rising living costs including that of good quality education and the need for two-member earning family to maintain a certain standard of living, contribute to the present generation of young couples not wanting to have more than one child. It is too early to say whether in spite of the fact that India has no officially imposed policy on one child, it will become a new norm and lead to further decline in fertility.

As posed by Zaidi & Morgan (2017), the question whether the second demographic transition (SDT) is just not a continuation of the first one in India is important. Many of the ingredients identified by the proponents of the SDT such as a major shift in norms which emphasize self-actualization rather than altruism altered the marriage and family formation behavior of couples. As shown, there is little evidence of major cultural shifts in India either in societal norms that govern marriage, which continues to be almost universal and largely arranged by families. There has been a steady decline in fertility to such an extent that having just one child is becoming an acceptable choice made by some couples in large metropolitan cities likely to spread in the coming years. But it is important to note that this change is largely a response to the rising cost of quality private education and associated expenses and not because the Indian women (and their families) value emancipation from childbearing and child rearing. Voluntary childlessness is still unacceptable.

One obvious implication of this shift to one or two children adopted by majority of the Indian couples is that the country’s population will increase at a slower pace compared to the past largely because the norm of having only two or one child has become widespread. Therefore, India is most unlikely to undergo sudden changes in its age structure as has been witnessed in China in recent decades. The smooth transition gives India an opportunity to adjust to changes in both fertility and mortality provided the country with foresight design and implement right policies and programmes. With increasingly smaller cohorts of children entering schools, investments needed to build school classrooms etc. the resources, if spent on improving the quality of public education, will strengthen the quality of future workforce, which in turn would boost the Indian economy.

In conclusion I may add that the long-term or lagged effects of current behavior of Indian couples are under-researched. The norm of single child is expected to spread in the growing middle class in India. Its medium-term implications need urgent attention. When parents spend a large sum of their earnings on raising that child and ready her/him to face the competitive world, the savings needed for their own old age would be reduced. In the absence of many affordable assisted living facilities or old age homes, increasing cost of health services, lack of social security, the future of old and of very old appears rather bleak, whose number will increase in the coming decades, thanks to increase in life expectancy. In big cities of India, the old couples, whose successful children have left the nest for greener pastures, are increasingly facing emptiness. There is an urgent need for both the government and civil society groups to creatively address and attend to this issue. Or, reverting to two or three children, with a hope that at least one of them will take care of parents in their old age, can become a possibility? Will societal norm of not accepting support and care from married daughters change for couples with a single daughter or only daughters? Some changes in cultural norms are inevitable but overall India is poised to enter the next phase of demographic transition in its own ways and on its own terms while buiding on its old well-established traditions, practices and value systems.

Notes

Most Indian newspapers after the NFHS 5 results were released in May 2022 attributed India’s TFR of 2.0 to the significant progress in population control measures. (See: Hindustan Times, May 11, 2022; The Economic Times, May 9, 2022).

Regardless of the quality of the content of education, the very fact that girls are allowed to leave home, mingle with other children, be exposed to a different environment gives them confidence to voice their preferences including those of family size and control and space births later in life.

To what extent the incentives offered to couples for using the long acting or permanent contraceptive methods such as IUD or sterilization have been responsible for the uptake of contraceptive methods is a debatable issue.

The singulate mean age at marriage (SMAM) is the average length of single life expressed in years among those who marry before age 50. Its value is generally slightly higher than the average age at marriage which is the age of a person when she or he gets married.

NFHS -5 for 2019–21 reports that the percentage of women age 18–29 who were first married by exact age 18 was 24.7. The difference in age categories used in the denominator and the wording between NFHS 4 and 5 surveys would have to be rectified when analysis is done with individual or unit level data.

In India the castes are divided into innumerable sub-castes and each one is endogamous. Given India’s geographical and linguistic diversity, the selection of spouse is made within a kin cluster living within a restricted geographical area. Endogamous rules are followed by non-Hindus also.

For example, Muslim family matters are governed by the Muslim Personal Law (Sharia) Act of 1937, under which marriage is a contract, and Dissolution of Muslim Marriages Act of 1939. The Christian marriages are governed by the Christian Marriage Act of 1872 and the India Divorce Act of 1869. Hindu marriages and divorces are governed by the Hindu Marriage Act of 1955 which also applies to Buddhist, Jains and Sikhs. In addition, there is also a Special Marriage Act which allows for marriage between members of any or no religious affiliation and governs divorces.

As per the Indian law, in the live-in relationships which are in a nature of marriage, that is, the couples live for a long period of time and present themselves as husband and wife, a woman can seek protection under Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 and can claim for maintenance if the relationship does not work out or if one partner wishes to end it.

An examination of the annual statistics of age specific marital fertility for the age group 15–19 show steady increase in their fertility between 2011 and 2019 (from 240 births in 2011 per 1000 married women to 287 births in 2016, 323 in 2018 and 337 in 2019). This increase appears a bit puzzling when at age 20–24, marital fertility has almost remained unchanged. The one plausible explanation is that young women are increasingly cohabiting with their spouses immediately upon marriage now compared to the earlier times when the practice of young girls spent intermittently long period of time at parental home after marriage until they are accustomed to the conjugal family and its responsibilities. It is likely that such norms are not followed rigorously now.

Aries (1980) coined the term ‘child king’ to explain the phenomenon of families becoming child-oriented where the parental affection becomes centered on children. Parents realize that fewer children would enable them to invest greater resources in each child and hope that it would lead to upward social and economic mobility.

References

Agrawal, P., Agrawal, S., & Unisa, S. (2012). Spatial, socio-economic and demographic variation of childlessness in India: a special reference to reproductive health and marital breakdown. Global Journal of Medicine and Public Health, 1(6), 1–15.

Aries, P. (1980). Two successive Motivations for the declining birth rate in the West. Population and Development Review, 6(4), 645–650.

Arokiasamy, P. (2009). Fertility decline in India: contributions by uneducated women using contraception. Economic & Political Weekly, 44(30), 55–64.

ASSOCHAM. (2008). Rising school expenses vis-a –vis dilemma of young parents. Unpublished report.

Atoh, M., Kandiah, V., & Ivanov, S. (2004). The second demographic transition in Asia? Comparative analysis of the low fertility situation in East and South-East Asian countries. The Japanese Journal of Population, 2(1), 42–75.

Banerjee, A., et al. (2013). Marry for what? Caste and mate selection in modern India. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 5(2), 33–72. https://doi.org/10.1257/mic.5.2.33

Basu, A. M., & Desai, S. (2016). Hopes, Dreams and Anxieties: India’s One-Child Families. Asian Population Studies, 12(1), 4–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441730.2016.1144354

Basu, A.M., & Desai, S. (2010). Middle class dreams: India’s one child families. Extended abstract in the Annual Meeting of Population Association of America (PAA), Dallas, Texas. April 15–17, http://paa2010.princeton.edu/papers/101686.

Bhagat, R. B. (2016). The Practice of Early Marriages among Females in India: Persistence and Change. Working Paper No. 10, International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai, doi: https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.2741.4801.

Blanc, G., 2020, “Modernization Before Industrialization: Cultural Roots of the Demographic Transition in France”, ffhal-02318180v8f. accessed on 18.08.2022.

Bongaarts J, (2009). Human population growth and the demographic transition., Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, No.364, 2985–90. doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2009.0137.

Bhat, M. P. N. (2002). Contours of fertility decline in India: A district level study based on the 1991 Census. In K. Srinivasan (Ed.), Population Policy and Reproductive Health (pp. 96–107). Hindustan Publishers.

Canning, D. (2011). The causes and consequences of the demographic transition. Population Studies, 65(3), 353–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324728.2011.611372

Cochran, L. T., & O’Kane, J. M. (1977). Urbanization-Industrialization and the theory of demographic transition. The Pacific Sociological Review, 20(1), 113–134.

Casterline, J. B., (2003). Demographic Transition In: Demeny, P. and McNicoll, G. (eds.), Encyclopedia of Population, Vol. 1, Thomson & Gale, New York, pp. 210–216.

Chandrasekhar, C. P., & Ghosh, J. (2020). The alarming rise in the cost of education in new India’, The Hindu Business Line, November 30.

Coale, A.J. (1973). The demographic transition reconsidered, Proceedings of the International Population Conference, Liege, pp. 53–72.

Das, N. P., & Dey, D. (1998). Female age at marriage in India: trends and determinants. Demography India, 27, 91–115.

Desai, S., & Andrist, L. (2010). Gender scripts and age at marriage in India. Demography, 47(3), 667–687. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.0.0118

Dommaraju, P. (2009). Female schooling and marriage change in India. Population-E, 64(4), 667–668.

Dommaraju, P. (2016). Divorce and separation in India. Population and Development Review, 42(2), 195–223. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2016.00127

Dreze, J., & Murthi, M. (2001). Fertility, education, and development: Evidence from India. Population and Development Review, 27(1), 33–63. Accessed 22 Jul. 2022.

Dyson, T. (2010). Population and Development: The Demographic Transition. Zed Books.

Ganguly, S., & Unisa, S. (2010). Trends of Infertility and Childlessness in India: Findings from NFHS Data. Facts. Views & Vision in ObGyn, 2(2), 131–138.

Goyal, R. P. (1988). Marriage age in India. Publishing House, New Delhi.

Ghosh, S. (2015). Second Demographic Transition or Aspirations in Transition: an exploratory analysis of lowest low fertility in Kolkata, India. Asia Research Centre (ARC) London School of Economics & Political Science, Working Paper 68.

Guilmoto, C. Z., & Rajan, S. I. (2005). Fertility Transition in South India. Sage Publications.

Ibarra-Nava, I., Choudhry, V., & Agardh, A. (2020). Desire to delay the first childbirth among young, married women in India: a cross sectional study based on national survey data. BMC Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8402-9

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), 1995, National Family Health Survey (MCH and Family Planning), India 1992–93. Bombay, IIPS.

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ORC Macro. 2000. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-2), 1998–99: India. Mumbai: IIPS.

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Macro International. 2007. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), 2005–06: India: Volume I. Mumbai: IIPS.

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF., 2017. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015–16: India. Mumbai: IIPS.

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF. 2021. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), 2019–21: India. Mumbai: IIPS

Jacob, S., & Chattopadhyay, S. (2016). Marriage dissolution in India: Evidence from Census 2011. Economic and Political Weekly, 51(33), 25–27.

James, K. S. (2011). India’s Demographic Change: Opportunities and Challenges. Science, 333(6042), 576–580. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1207969

James, K. S., & Srinivasan, K. (2015). Stability of the Institution of Marriage in India: the golden cage. Economic and Political Weekly, 50(13), 38–45.

Jejeebhoy, S. J., Santhya, K. G., & Zavier, A. J. F. (2014). Demand for Contraception to Delay First Pregnancy among Young Married Women in India. Studies in Family Planning, 45(2), 183–201.

Kumar, S. (2020). Trends, differentials and determinants of child marriage in India. Economic and Political Weekly, 55(6), 53–58.

Kundu, S. P. (2018). Status Single: The Truth About Being a Single Woman in India, Amaryllis. An imprint of Manjul Publishing House.

Lesthaeghe, R. (1995). The second demographic transition in Western countries. In K. O. Mason & A. M. Jensen (Eds.), Gender and Family Change in Industrialized Countries (pp. 17–62). Clarendon.

Lesthaeghe, R., Surkyn, J. (2008) When history moves on: The foundations and diffusion of a second demographic transition. In: R. Jayakody, A. Thornton and W. Axinn (eds.), International family change: Ideational Perspectives, Routledge, pp. 81–118.

Lesthaeghe, R. (2010). The Unfolding Story of the Second Demographic Transition. Population and Development Review, 36, 211–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728.4457.2010.00328

McNaaay, K., Arokiasamy, P., & Cassen, R. H. (2003). Why are uneducated women in India using contraception? A multilevel analysis. Population Studies, 57(1), 21–40.

Mohanty, S. K., et al. (2016). Distal determinants of fertility decline: evidence from 640 Indian districts. Demographic Research, 34, 373–406. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2016.34.13

Nagaraj, K. (1999). Extent and nature of fertility decline in Tamil Nadu. Review of Development and Change, 4(1), 89–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972266119990105

Narayan, C. L., Narayan, M., & Deepanshu, M. (2021). Live-in relationships in India—Legal and psychological implications. Journal of Psychosexual Health., 3(1), 18–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/2631831820974585

Notestein, F. W. (1945) Population-The long view, In: T. W. Schultz (ed.), Food for the World, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp. 36–57.

Office of the Registrar General, 2013, Sample Registration System Report 2011, New Delhi.

Padmadas, S. S., Hutter, I., & Wilekens, F. (2004). “Compression of women’s reproductive spans in Andhra Pradesh India. International Family Planning Perspectives, 30(1), 12–19.

Pradhan, I., & Sekher, T. V. (2014). Single-child families in India: levels, trends and determinants. Asian Population Studies, 10(2), 163–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441730.2014.909962

Reher, D. S. (2011). Economic and social implications of the demographic transition. Population and Development Review, 37(1), 11–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728.4457.2010.00376

Singh, S., et al. (2022). Key drivers of fertility levels and differentials in India, at the National, State and population subgroup levels, 2015–2016: an application of Bongaarts’ proximate determinants model. PLoS. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263532

Subramanian, P. K. (2008). Determinants of the age at marriage of rural women in India. Family & Consumer Sciences, 37(2), 160–166.

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, 2017, World Population Prospects 2017 – Data Booklet (ST/ESA/SER.A/401).

van de Kaa, D. J. (1987). Europe’s second demographic transition. Population Reference Bureau.

Visaria, L. (2004). The continuing fertility transition. In T. Dyson, R. Cassen, & L. Visaria (Eds.), Twenty-First Century India: Population (pp. 57–73). Oxford University Press.

Visaria, P., & Visaria, L. (1994). Demographic transition: Accelerating fertility decline in the 1980s. Economic and Political Weekly., 29, 3281–3292.

Zaidi, B., & Morgan, S. P. (2017). The second demographic transition: a review and appraisal. Annual Review of Sociology, 43(1), 473–492. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-060116-053442

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Visaria, L. India’s date with second demographic transition. China popul. dev. stud. 6, 316–337 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42379-022-00117-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42379-022-00117-w