Abstract

China’s “one-child policy” that had been in force between 1980 and 2016 evolved over time and differed widely between regions. Local policies in many regions also targeted the timing and spacing of childbearing by setting the minimum age at marriage, first birth and second birth and defining minimum interval between births. Our study uses data from the 120 Counties Population Dynamics Monitoring System to reconstruct fertility level and timing in nine counties in Shandong province, which experienced frequent changes in birth and marriage policies. We reconstruct detailed indicators of fertility by birth order in 1986–2016, when policies on marriage and fertility timing became strictly enforced since 1989 and subsequently relaxed (especially in 2002) and abandoned (in 2013). Our analysis reveals that birth timing policies have fuelled drastic changes in fertility level, timing and spacing in the province. In the early 1990s period fertility rates plummeted to extreme low levels, with the provincial average total fertility rate falling below 1 in 1992–1995. Second births rates fell especially sharply. The age schedule of childbearing shifted to later ages and births became strongly concentrated just above the minimum policy age at first and second birth, resulting in a bimodal distribution of fertility with peaks at ages 25 and 32. Conversely, the abandonment of the province-level policy on the minimum age at marriage and first birth and less strict enforcement of the policy on the minimum age at second birth contributed to a recovery of period fertility rates in the 2000s and a shift to earlier timing of first and second births. It also led to a shorter second birth interval and a re-emergence of a regular age schedule of fertility with a single peak around age 28.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

China’s “one-child policy” that had been implemented from 1980 to 2016 evolved over time and differed widely between regions (Attané, 2016; Chen et al., 2009; Qin et al., 2018; Scharping, 2013). In addition to child-number policy, local policies in many regions also targeted the timing and spacing of childbearing by specifying the minimum age at marriage, first birth and second birth and defining minimum interval between births. These policy restrictions changed frequently and their enforcement also varied by region. Together, these localised policy regulations and their frequent revisions implied massive diversity across regions in their timing and spacing policies. The family planning policies were enforced with a combination of rewards for the couples who obeyed the policy regulation (notably, one-child couples were often eligible for cash subsidies, housing provision, and extra food) and coercion and penalties for the couples who violated the policy rules; in particular in the form of a huge financial penalty (“social child-raising fee”) imposed on the couples having unauthorised child (e.g., Short & Zhai, 1998).

The diversity in fertility and marriage policies in China across time and between regions contributes to a wide variation in fertility across provinces and counties in China (Qin et al., 2018; Wang & Chi, 2017). It also presents an excellent opportunity for studying fertility reactions to the changes in birth number, birth timing and birth spacing policies, especially following the years when new policy regulations had been established or abandoned. Because of the parallel existence of national- and region-specific regulations and regional differences in the intensity in policy enforcement, the impact of policies should be studied locally. Changes in family planning policies in China can be studied as a “natural experiment” that dramatically altered the decisions about the number, timing, and spacing of births among Chinese couples. Although the shift to low fertility in China has been partly driven by social and economic development, including urbanisation and massive education expansion (Cai, 2010), policies regulating fertility and marriage played an important role. They influenced fertility trends and accelerated the fall in fertility in China to very low levels. Their frequent changes and revisions also contributed to fertility swings in China and in Chinese regions during the last three decades. However, only a few studies analysed systematically local variation in family policies and how it affected fertility over time (e.g., Cai, 2010; Scharping, 2013; Short & Zhai, 1998; Wang & Chi, 2017).

We use a unique dataset, the 120 Counties Population Dynamics Monitoring System (hereafter also labelled 120 CMS) to reconstruct fertility level and timing in nine counties and county-level cities in Shandong province, which experienced frequent changes in birth and marriage policies as well as relatively strict enforcement of policy regulations. The dataset allows us to derive detailed indicators of fertility by birth order in the period 1986–2016, when policies on marriage and fertility timing became strictly enforced since 1989 and subsequently relaxed (especially in 2002) and abandoned (in 2013). Also, we cover the period 2014–2016 when one-child-policy was relaxed across the whole China. First it was replaced by a “selective two child-policy” (all couples where one partner was single child were eligible to have a second child) and later by a universal two child policy. The nine counties covered differ widely in their economic development, urbanisation, and policy fertility level until 2016. To summarise the evidence across analysed regions, we also estimate population-weighted average fertility indicators for the whole Shandong province.

Our analysis combines period and cohort data that provide insights about both short-term and long-term fertility responses to policy restrictions and their revisions. We look especially at first and second births, which make up about 90% of the overall fertility, and document massive shifts in fertility timing, spacing and in the age profile of childbearing following the strict enforcement of mandatory age at marriage and second birth since 1990. Specifically, our study addresses the following questions:

-

How did the shifts in marriage and birth timing policies affect period fertility level as well as the timing and spacing of births?

-

Did these shifts in period fertility have a lasting influence on cohort fertility trends, especially on the cohort progression rates to second birth?

-

What does the evidence for the province of Shandong reveal about the fertility transition in China and the shift to a later childbearing in the country?

Our results reveal that the enforcement of marriage and fertility timing policies since 1990 brought about a massive postponement of both first and second births and lengthening of the second birth interval, leading to a temporary sharp fall in period total fertility rate (TFR) to extreme low levels in the mid-1990s. They also brought about a strong concentration of childbearing into a narrow age interval just after the mandatory minimum ages at first and second birth. Later, policy relaxations resulted in period fertility upswings. Cohort fertility rates and parity progression ratios were much less affected, suggesting that the main effect on birth and marriage timing policies was in fuelling instability in period fertility rates during the 1990s and 2000s.

The article is structured as follows. First we outline key family policy trends in China and in Shandong province since the 1970s. Then we introduce data, methods and indicators used. Subsequently, we present trends in period fertility level, fertility timing and spacing, age pattern of childbearing, and discuss their impact on completed fertility and the transition to second birth. The concluding discussion summarises main findings, highlights the role of a stricter enforcement of birth planning policies since 1990, and provides a brief reflection on the ongoing “postponement transition” in fertility in China.

2 Background: key family policy trends in China and in Shandong province

2.1 The evolution of national policies

Since their introduction in the 1970s, the policies aiming to regulate marriage and childbearing in China were revised frequently. In the 1970s, later marriage and later childbearing rules were applied in the cities where couples were encouraged to delay marriage until age 25 for women and age 28 for men and not to have more than two children. Urban and rural couples alike had to conform to a longer birth-spacing period of at least 3–4 years (Attané, 2002).

The establishment of one-child policies, first discussed in 1978, was motivated by the goal of quickly reducing high birth rates, which were seen as impeding economic growth (Wang et al., 2013). In February 1980, a set of developmental goals had been formulated, including a goal of limiting a total population in China to 1.2 billion in 2000, accompanied by policies that restricted 95% of urban couples and 90% of rural couples to having only one child (Wang et al., 2013). This drastic fertility limitation was in part enforced by a host of coercive measures. However, popular resistance forced the government to relax its most stringent rules. From 1984 on, rural couples have been allowed a second child, subject to province-specific conditions (Attané, 2002; Gu et al., 2007; Scharping, 2013).

In the 1980s, each province enacted its own set of family-limitation regulations, leading to a great policy variation between provinces (Short & Zhai, 1998). Exceptions from the one-child-per-couple rule were defined within regions (provinces and prefectures) and applied either for specific population groups (rural residents, ethnic minorities, specific socio-economic groups or occupations) or for all couples in the region fulfilling certain criteria (e.g., both partners being the only children) (Attané, 2002; Gu et al., 2007; Scharping, 2013; Short & Zhai, 1998). Altogether, Gu et al. (2007) identified 22 circumstances where couples were exempted from one-child policy based on examination of 420 prefecture-level family planning policy guidelines in 1999. A new mechanism, “the family planning responsibility system” was established to hold all cadres accountable for successful policy implementation (Greenhalgh, 1986). Birth spacing requirements also spread across the country, with most provinces requiring a minimum spacing of 4 or 5 years between the first and the second birth. In addition, some provinces also set a minimum age for women who could have a second birth, while other provinces specified both birth timing and birth spacing requirements (Zhang & Liu, 2016). People’s reproductive behaviour—the timing of marriage and first birth, the possibility to have a second child, as well as the timing and spacing of the second birth—thus became subject to administrative regulation that combined national and local rules and policies.

Enforcement of the birth limitation program was tightened nation-wide since 1991 (Greenhalgh & Li, 1995; Zeng, 1996). Supported by an extensive bureaucracy devoted to surveillance and policy enforcement, the policy penetrated Chinese society from the highest level of the government down to urban neighbourhoods and rural villages (Cai, 2010; Greenhalgh, 2008; Gu et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2013). As a result, local and nationwide birth registration system in China became unreliable and incomplete, with frequent omissions of unplanned (or “unauthorised”) births (Jiang et al., 2013). Since the mid-1990s rural couples who could have a second birth often had to wait longer for the authorization in order to achieve the local-level quotas (Hu, 1998).

Only since the turn of the twenty-first century Chinese population policy began to show less demographic quantitative orientation, with more focus on individual well-being (Attané, 2002). Eventually, the extensive birth control policies in China have been abandoned or rolled back. The provinces which used to require minimum interval between the first and the second birth phased out these requirements. As of 2016, no birth spacing requirements remained in provincial regulations (Zhang & Liu, 2016), implying that couples could freely decide about the timing of their second birth. The “one child policy” was abandoned. In November 2013 it was replaced by “selective two-child policy” and since January 2016 by a “universal two-child policy”, whereby every couple was allowed to have two children. Most recently, a “three-child policy” announced on 31 May 2021 effectively spells the end of fertility limiting policies in China as very few women and couples desire to have more than two children.Footnote 1

2.2 Key fertility characteristics and family policy trends in Shandong province

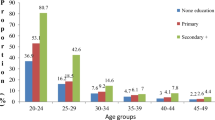

Shandong is a coastal province in the East of China. It is the second most populous province in the country, with population of 91 million in 2016; in terms of the GDP per capita it ranked as the ninth wealthiest province in China in 2016. Shandong is also very diverse, with coastal regions being much more prosperous than interior prefectures. Similar to the other provinces in China, it experienced massive education expansion in the last decades, first concentrated at secondary education, but more recently also marked by a rapid rise in higher education, with the share of young people still studying in their early twenties surging rapidly after 2005. At the same time, also the share of never-married women past age 25 has increased fast since 2005 arguably as a result of their higher education, career aspirations, but also changing attitudes to marriage and women’s roles (Yu & Xie, 2015).

Shandong province has a long history of policies regulating reproduction. It took the leading role in national family planning policy enforcement and its subsequent deregulation in the last decades. The province enacted numerous regulations aimed to control birth timing in order to reach provincial and local population control targets. Overall, it had low level of family policy permissiveness (Attané, 2002), with ‘policy fertility’ level allowing on average 1.45 births per woman (Gu et al., 2007). The regulations regarding marriage age and childbearing in the province were established earlier than in most other provinces. As Fig. 1 shows, these policies changed frequently, with the eligibility criteria for the second births determined in part by a series of exceptions that varied from place to place and changed over time (Short & Zhai, 1998).

As early as in the 1960s some prefectures in the Shandong province stipulated later marriage and later childbearing rules in their cities. More cities followed suit in the 1970s. Shandong province was also among the first regions pioneering the “Wan, Xi, Shao” (Later, Longer, Fewer) policy. In 1979, minimum marriage age requirement had been set at 25 for rural males and 23 for rural females.

From 1980 Shandong province began implementing strict one-child policy. Later, the Shandong Province Family Planning Regulations, decreed in 1988, specified 13 categories of exceptions, defining which couples who allowed to have a second birth (Gu et al., 2007), with the minimum age at second birth set at 30. The provincial government pursued severe administrative control to limit early marriage and early childbearing since 1989, ahead of the national movement to tighten the enforcement of the birth-limiting program. Later marriage and later age at childbearing started to be included as key indicators in the annual performance evaluation at different level of local family planning in the province.

From 2001 Shandong province documents no longer emphasized the importance of later marriage and excluded it from the sets of population control evaluation indicators. One year later, since 2002, women in Shandong province could freely decide on the timing of their first birth. In 2013 the second birth spacing requirements were abandoned. Finally, as in the whole China, one-child policy was abandoned as well, and after a brief period of “selective two child policy” in 2014–2015, a universal policy of two children per couple came into the effect since January 2016.

Despite restrictive policy regulations, fertility in Shandong province did not fall as much as in some other prosperous Chinese provinces. The 2010 population Census showed a completed fertility at 1.48 births per woman born in 1970, about 10% below the national average (1.61). A 1% sample survey of 2015 put the completed fertility of these women in Shandong province at a slightly higher level of 1.56. This level is comparable to that in the lowest-fertility countries globally. Several national and provincial surveys suggest that women in Shandong province retained relatively high fertility intentions. In the 2004 Shandong province fertility survey, over 70% respondents preferred to have at least two children. The ideal number of children among married men and women aged 20–44 in the province was 1.92 in a national sample survey conducted in 2013, higher than in most other provinces (Zhuang et al., 2014). These relatively high reproductive intentions also help explaining why the province experienced a remarkable rebound in fertility following the recent abandonment of one-child policy (Sects. 4.2 and 4.5 below).

3 Data and methods

3.1 Data: the 120 Counties Population Dynamics Monitoring System

We use data from the 120 Counties Population Dynamics Monitoring System (120 CMS) coordinated by the National Health and Family Planning Commission (NHFPC) of China.Footnote 2 The system was developed on the basis of the 2000 National Population Census. County level units included in the system were randomly selected from eastern, central and western regions. The aim is to collect the information on demographic and socioeconomic characteristics and to monitor selected vital events on an annual basis, covering each individual resident in each of the 120 counties and county level cities and districts (hereafter labelled as counties). The information collected include sex, age, birth date, place of birth, place of household registration, place of current residence, education, marital status and other characteristics. The NHFPC began collecting data through this system and conducting annual analyses since 2008. The 120 CMS is composed of specific databases, including household database, women’s database, and women’s birth history database. In the whole country, 117 out of 120 counties that reported their current resident population in 2020, had population of 128.4 million, accounting for 9.4% of national population.

Previous research proved the overall good representativeness of the 120 CMS. The monitoring system’s data on second birth intervals also matched closely with the results of the long-questionnaire on fertility in the 0.95% sample of the 2000 population census and other sources (Wang, 2013; Zhang et al., 2016). The 120 CMS covers all births among women who were of reproductive age in the late 1990s and the early 2000s. Comparisons of period and cohort fertility indicators suggest that the monitoring data cover well the births in the analysed counties in Shandong province since the mid-1980s. Based on data quality and coverage evaluation we decided to focus our analysis on the period of 1986–2016. The datasets also allowed us to reconstruct almost complete birth histories for the cohorts of women born in 1964–1976.

3.2 Analysed data for Shandong province

We use data on retrospective birth histories of women in nine counties in Shandong province included in the 120 CMS. These counties cover central, eastern and western administrative units of the province (see Table 1; Fig. 2). They have a total population of 7.7 million, representing 8% of the provincial population. The regions are very diverse in terms of their urbanisation rate, level of economic development and the actual level of period fertility. Three counties with highest urbanisation rate (Rencheng, Linzi, Gaomi) are characterised by a low level of policy fertility, and, also, very low period fertility rates (Table 1). In contrast, three of the counties with low level of urbanisation (Mudan, Mengyin, Lanling) share relatively low level of economic development, higher policy fertility and high (compared to China’s average) actual fertility rates. Despite their higher fertility level, Mudan and Mengyin have strongly distorted sex ratios at birth, suggesting widespread practice of sex-selective abortion. In combination, the population weighted data for the nine analysed counties come close to the provincial average in terms of their urbanisation, sex ratio at birth and ideal family size, while they are on average slightly less economically developed than the whole province.

We decided to analyse only data for women who are included in local household registration system (hukou), excluding women resident in the region, but with household registration elsewhere.Footnote 3 This improves the reliability of our data, especially with respect to the completeness of birth histories, as the registration system might not provide a full coverage of birth histories of women who migrated from other counties and provinces and it may not give a full coverage of unauthorised migrant populations. However, the exclusion of migrant women also means that our analysis is not fully representative of the population in the analysed counties as it does not capture the sizeable “floating population” of residents without local hukou. Because the floating people typically come from poorer and rural locations with higher fertility rates, our analysis may underestimate fertility rates among the total population in the analysed regions.

3.3 Methods, indicators and key policy changes analysed

We focus on changes in fertility level, timing and spacing following three major policy shifts targeting the timing of marriages and births: (1) the tightening of the administrative control over the minimum age at marriage and second birth since 1989, (2) easing out of the control over the age at marriage and an abandonment of the minimum age at first birth in 2001–2002, and (3) an abandonment of the restrictions on age at second birth in 2013 and subsequent replacement of the “one-child policy” with a “selective two-child policy” in 2014–2015 and with a “universal two-child policy” in 2016. We expect that these policy changes affected especially the timing of childbearing, stimulating postponement of first and second births after 1989. We also expect a strong temporary influence of these timing shifts on period fertility trends. In contrast, a possible shift to earlier childbearing in the 2000s might have given a temporary boost to period fertility rates.

The mandatory minimum ages at marriage and second birth, imposed by local administration since 1989, were considerably higher than the mean age at first and second birth in most of the counties at that time. These birth timing restrictions are quite unique, unrivalled by family and fertility policies used in other countries. We look at their impact using conventional period indicators of fertility level, timing and spacing such as the period TFR and period mean age at childbearing (MAB) specified by birth order, as well as indicators of second birth parity progression ratios and second birth intervals to get a finer understanding of the resulting fertility shifts. We use age-specific fertility rates by birth order to study to what extent childbearing became concentrated within a short age span around the minimum mandatory age at first marriage, first and second birth. Finally, we analyse cohort indicators of fertility and parity progression ratios to see whether the analysed policies left a lasting impact on cohort fertility levels.

4 Findings

4.1 Changes in period fertility

Period fertility rates in the analysed regions exhibit a U-shaped pattern between 1989 and 2005, with a massive fall in fertility starting in 1990, immediately after the launching of administrative push in 1989 to impose fertility and marriage timing restrictions (Fig. 3). Period TFR plummeted throughout the early 1990s, bottoming out in most regions in 1994. The fall in fertility was sharpest in counties that had higher fertility rates, leading to the narrowing in fertility differences between regions. In 1994, the weighted average TFR for the province fell to an extreme low level of 0.81, down from 1.96 in 1989, with two counties, Yanggu and Yangxin, reaching a low of 0.5 in 1994. Subsequently, the TFR saw a gradual recovery and by the early 2000s it bounced back close to the values reached in the late 1980s, later fluctuating at around 1.7–1.9 in 2005–2013. At the same time, cross-county differences increased again, with a wide variation in the TFR between around 1.1 in the most affluent region of Linzi to around 2.5 or even higher in the predominantly rural region of Lanling.

[Source: Authors’ computations based on 120 Counties Population Dynamics Monitoring System (120 CMS, 2016)]

Period total fertility rate (TFR) by birth order in 9 counties and county level units in Shandong province, 1986–2016. Note: Data for the whole Shandong province are population-weighted averages for the nine regions analysed

The easing of the one-child policies in 2014 and 2016 led to a limited increase in period fertility. Whereas first-order TFR fell, presumably due to a renewed postponement of first births in many regions (see below), the second-order TFR bounced up in 2014 and 2016, as some couples seized the new opportunity to have a second child.

The fall in fertility in the early 1990s was visible across all birth orders, but it was especially sharp for the second and third births. The second-order TFR fell by about three quarters on average to the levels of 0.1–0.3 and second birth period parity progression ration plummeted as well. The third and higher-order fertility was all but eliminated in the mid-1990s. However, the subsequent fertility rebound was especially strong for second-order births. Thus, the ups and downs in period fertility in the 1990s-2000s were driven especially by the shifts in second birth rates.

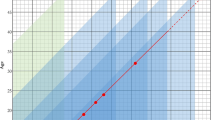

4.2 Changes in period fertility timing and spacing

The trends in the timing of childbearing indicate that the policies promoting later marriage and childbearing had the strongest effect on the timing and spacing of the second births. Although the mean age at childbearing increased rapidly throughout the 1990s, it did not show a clear trend reversal after 1989 (Fig. 4). The mean age at first birth rose especially in the first half of the 1990s and it increased most in the counties where it was the lowest by the late 1980s—suggesting a rapid convergence towards the age around 25, in line with the policy limit. But the largest shifts occurred in the timing of the second births, which were delayed dramatically during the 1990s. The mean age at the second birth (MAB2) in the province jumped from 26.9 to 31.2 in the decade since 1989. Across all counties, the MAB2 surpassed age 30 by the late 1990s, in line with the policy minimum age at the second birth. This massive postponement of second births was achieved in part by a lengthening of the second birth interval, which reached around 7 years in most regions in the late 1990s. Once the regulations related to age at marriage and childbearing were relaxed in 2002–2003 the shift to later timing of childbearing came to an end and first births gradually shifted to a younger age in most counties. In addition, the differences in fertility timing between counties grew rapidly as women in more rural and less developed regions shifted births to younger ages, whereas women living in more developed and more urban areas delayed family formation to yet later ages after 2010.

[Source: Authors’ computations from 120 Counties Population Dynamics Monitoring System (120 CMS, 2016)]

Period mean age at childbearing (total and by birth order) and mean birth interval between first and second birth in 9 counties in Shandong province, 1986–2016. Note: Data for the whole Shandong province are population-weighted averages for the nine regions analysed

4.3 A strong concentration of childbearing beyond the policy minimum age at marriage and second birth

A detailed analysis of changes in age-specific fertility rates (ASFR) suggests highly effective enforcement of marriage and birth timing policies in the province. There was a sharp reduction in first birth rates at ages 18–23 in 1991–1994, consistent with the minimum age at marriage of 23 stipulated by the policy. At the same time, second birth rates plummeted at ages 18–30, again perfectly in line with the policy enforcing a minimum age at second birth of 30 years.

As a result of these shifts in fertility timing, first and second birth rates in the 1990s became strongly concentrated into a narrow age span, just beyond the required minimum age at marriage (23) and second birth (30) (Fig. 5). A combination of a sharp concentration of the first and second birth rates into a narrow age band resulted in the pronounced bimodality in fertility schedules in the province, with an earlier peak at age 24–25 (similar to the previous schedule) and a later and lower peak at ages 31–32. The age schedule of fertility depicted irregular and distorted patterns, unparalleled outside China.

4.4 Summarising the policy effects on period fertility level and timing: fertility shifts after 1989 and 2002

Figures 6 and 9 (Appendix) summarise changes in fertility level and timing following the tightening of the fertility and marriage timing policies in Shandong province in 1989 and their abandonment in 2002–2003. We look at the relative changes in period fertility indicators within a 5-year period following these policy changes and at the absolute changes in the mean age at childbearing and in mean birth intervals within a 10-year period since the policy shifts. A selection of a longer interval for our analysis of the changes in birth timing was motivated by a longer time needed for the age-schedule of childbearing to adjust to the new policies.

[Source: Authors’ computations based on 120 Counties Population Dynamics Monitoring System (120 CMS, 2016)]

Relative changes in selected indicators of fertility over the periods 1989–1994, 2002–2007 and 2012–2016; nine counties in Shandong province (initial fertility level in the base year is 1.0; each circle represents one county, the weighted average for the whole province shown by black circles)

Our analysis shows a massive disruption in period fertility indicators in 1989–1994, especially at higher birth orders, in part driven by an intensive postponement of childbearing induced by the new policies. With one exception, all analysed counties show a fall in each of the fertility indicators analysed in Fig. 6. Especially the second birth rates, as measured by both the second-order TFR and the period parity progression ratio (PPR12), fell drastically (by about three quarters on average). Third-order TFR fell even more. The indicators of fertility timing show an intensive fertility postponement across all counties analysed, with a drastic shift towards later second births (Fig. 9).

The fertility reaction to the abandonment of administrative restrictions regarding marriage and fertility timing was less dramatic. Period fertility rates increased across most counties and the rise was strong for second- and especially third-order TFR (in the latter case from very low initial levels). However, this fertility upturn followed up on an earlier rise in period fertility in the second half of the 1990s and early 2000s. Hence, it is difficult to distinguish the positive impact of the easing of policy restrictions on fertility from the continuing trend of a “recovery” of depressed fertility rates that had been under way before 2002. However, one sign that the policy changes had some positive effects on fertility is provided by the regional differentiation in fertility trends after 2002. Fertility rose quickly in 2002–2007 especially in the regions where fertility rates had been higher until the late 1980s. In addition, Fig. 9 documents a slight reversal in the previous trend towards later timing of births. Once women became free to choose the timing of their births, many counties displayed a shift to earlier childbearing. Interestingly, this shift was clearly manifested only for the first births, with women in more rural counties having children more often at ages 18–23 and the mean age at first birth falling by 1 year on average in a decade since 2002. The previous trend of rising age at second birth and increasing second birth interval has come to an end in most counties, but no consistent trend to earlier timing of second births could be observed.

4.5 The impact on cohort fertility and parity progression

What was the impact of the sharp downturn of period fertility past 1989 on completed fertility? The combination of restrictions on the timing of marriage and childbearing together with the continuation of one-child policy mean that the possibility of having a second birth tightened most for the women having a first birth around 1989. Looking at the progression rate to the second birth within 10 years after the first birth, Fig. 7 shows a lasting policy impact. There was steep fall in the second birth rate for the women having their first birth between 1986 and 1990 across all analysed counties except one, Linzi, which already had very low second birth progression rate (just above 0.3) in the 1980s. On average, 70% of women in the province who had a first birth in 1986 eventually had a second child. However, this share dropped to 41% for the women having their first child in 1991. Then it gradually climbed up again, with 59% of women having their first birth in 2005 subsequently having a second child within the next 10 years.

Overall, completed cohort fertility of women who were in prime childbearing years in the 1990s declined modestly, by about 0.15 (or 9%) between the cohorts of 1964 and 1972 and stabilised at 1.6 thereafter (Fig. 8). This was by and large due to the reduction in the completed fertility for second births, which fell from 0.63 to 0.52 among women born between 1964 and 1971. Cohort fertility for third births fell as well, reaching a very low level around 0.1 By contrast, completed fertility rate for first birth remained almost flat and largely undisturbed by the policy changes. It changed slightly from 0.96 to 0.95, implying a minor rise in final childlessness from 4 to 5%.

[Source: Authors’ computations based on 120 Counties Population Dynamics Monitoring System (120 CMS, 2016)]

Period TFR in 1986–2016 and completed cohort fertility (among women born between 1964 and 1970s or early 1980s; Shandong province (weighted average based on the data for 9 counties); total fertility, first and second births and total fertility

5 Summary and discussion

Policies regulating the timing of marriage and childbearing in China between the 1970s and early 2010s received considerably less research attention than the “child number” policies limiting the total number of children per couple. This was in part because the “timing policies” were often localised and differed widely by provinces and smaller regions (counties, prefectures), their enforcement varied by region and over time, and they were frequently revised. Furthermore, their impact seems to be less consequential for the individual couples and for the overall fertility levels than the influence of the “child number policies”. Our investigation of the changes in period and cohort fertility rates following the shifts in birth timing policies and their enforcement in Shandong province between 1989 and 2013 shows that the “timing policies” are an overlooked part of the whole package of fertility-limiting policies in China that had a strong impact on fertility, especially in the regions with initially higher fertility level.

However, the main factor affecting fertility was not the imposition of new timing policies or their abandonment, but rather their actual enforcement by provincial and local authorities. For instance, policies specifying minimum age at marriage (23 for women, 25 for men) and at first birth (24 years, pending approval) were officially in place in the province throughout the 1980s. At the same time, about a half of all women had their first child before age 24, clearly in violation of these policies. It was only since 1990 when a strict enforcement of birth number, birth timing and marriage timing policies was applied across the province and later nationally. The impact of this enforcement was strong and immediate: period fertility rates plummeted to extreme low levels, with the provincial average TFR falling below 1 in 1992–1995. Second births rates fell especially sharply, with the second-order TFR dropping by about three quarters to the level of 0.2 in 1994. Birth timing underwent a radical change: since 1990 a large majority of first births occurred past age 23 and second births were shifted to ages 30 and older, in line with the minimum ages stipulated by the policy. This has brought about a radical restructuring of the age schedule of childbearing, with a particularly sharp upward shift in the mean age at second birth and a jump in second birth intervals to about 7 years, i.e., considerably longer than in other countries with low fertility today. A strong concentration of first births to ages 24–27 and of second births to ages 31–34 has resulted in a peculiar bimodal distribution of fertility, with peaks at ages 25 and 32. Later, the abandonment of the province-level policy on the minimum age at marriage and first birth at around 2002 and less strict enforcement of the policy on the minimum age at second birth contributed to a recovery of period fertility rates in the 2000s, to a reversal of the postponement of first births (after 2003) and of second births (after 2007) as well as to the shortening of second birth interval. Age schedule of fertility became more regular again, with a single peak around age 28.

The birth timing policies have strongly contributed to the ups and downs in period fertility in the province in the late 1990s and 2000s. They also left a lasting imprint on cohort fertility rates. The second birth rates declined most among the women affected by the more stringent enforcement of the timing policies since 1990. At the same time, second birth rates eventually recovered across most counties analysed and women having a first child in the early 2000s showed a much higher progression to the second birth than their counterparts entering motherhood in the early 1990s. Overall, the close match between the enforcement of birth timing policies and the actual timing of fertility indicates that women in Shandong province were more likely to obey the timing restrictions than the “birth number” policies. Women largely complied with the timing regulations without reducing radically their ultimate progression to the second birth. They flexibly responded to the policy enforcement by shifting the age at family formation and prolonging second birth intervals, but often without necessarily “giving up” their plans to have their second child. In the more rural counties, the persistence of local culture cherishing siblings as a sign of a household fortune and giving a higher value to boys than girls contributed to their strong recovery in period fertility. Today, the province still displays remarkable differences in fertility level and timing between mostly rural and less economically developed counties on the one hand and predominantly urban and more affluent counties on the other hand. The four most urbanised counties in our analysis, Rencheng, Linzi, Gaomi, and Zouping first reached a very low period fertility at or below 1.5 already in the 1990s and have largely retained it until now. The completed fertility of women in Rencheng and Linzi born in the early 1970s is around 1.3, comparable to the countries with lowest fertility rates globally such as Italy and Spain. Women in these counties also display low fertility intentions, suggesting that very low fertility has become entrenched there.

Our research also brings insights into the “postponement transition” (Kohler et al., 2002; Sobotka, 2017) towards a later timing of birth in China that is now well advanced. The initial shift towards delayed childbearing in the province in the 1990s was policy-driven, with first and second birth schedule concentrated just above the minimum policy age at first and second birth. The overall mean age at first birth jumped from about 25 to the level close to 28. Later, with the timing policies easing out, the postponement transition in Shandong province reversed between 2000 and 2013, with first and second birth schedule becoming younger and less concentrated. More recently, however, age at first birth has started rising again, this time driven by the factors observed in other low-fertility countries with delayed childbearing. These include higher education expansion, stronger labour market attachment of women, demanding work schedules, unaffordable housing and economic insecurity among young adults, delayed marriages as well as changing attitudes towards marriage and children. This “second wave” of the postponement of first marriages and births, driven by external conditions and changing preferences, puts a downward pressure on first birth rates. This helps explaining why fertility rates in the province (and in the whole China) did not increase much once the policies limiting second births were abandoned in 2014 and 2016 and the second birth rates increased. This evidence also points out that it might be difficult to achieve a sustained increase in period fertility rates in China in the next two decades (Morgan et al., 2009): with further education expansion and a continuation of other factors contributing to delayed parenthood, the country is set to follow the earlier path of many highly developed countries of a continuous postponement of first births (Sobotka, 2017). This long-lasting shift to late parenthood is likely to deflate period fertility for many years to come.

Notes

Only 9.3% of the respondents of the 2017 National Fertility Survey intended to have three or more children (Zhuang et al., 2020).

The National Health and Family Planning Commission has been dissolved and its functions integrated into the new agency called the National Health Commission after State Council institutional reform in March 2018.

Household registration, or hukou, is one of the most important elements in China’s birth planning policy (Scharping, 2013). There are two general categories of hukou: agricultural and non-agricultural (sometimes referred to as rural and urban). Under this system, a person’s hukou is determined at birth, and changing it is nearly impossible. Between the 1990s and 2013 people with an urban hukou usually could have one child, while people with a rural hukou were often eligible to have a second child, especially if their first birth was a daughter born during one-child policy period.

References

Attané, I. (2002). China’s family planning policy: an overview of its past and future. Studies in Family Planning, 33(1), 103–113.

Attané, I. (2016). Second child decisions in China. Population and Development Review, 42(3), 519–536.

Cai, Y. (2010). China’s below-replacement fertility: government policy or socioeconomic development? Population and Development Review, 36(3), 419–440.

Chen, J., Retherford, R., Choe, M. K., Li, X., & Hu, Y. (2009). Province-level variation in the achievement of below-replacement fertility in China. Asian Population Studies, 5(3), 309–328.

Greenhalgh, S. (1986). Shifts in China’s population policy, 1984–86: views from the central, provincial, and local levels. Population and Development Review, 12(3), 491–515.

Greenhalgh, S. (2008). Just one child: science and policy in Deng’s China. University of California Press.

Greenhalgh, S., & Li, J. (1995). Engendering reproductive policy and practice in peasant China: for a feminist demography of reproduction. Signs, 20(3), 601–641.

Gu, B., Wang, F., Guo, Z., & Zhang, E. (2007). China’s local and national fertility policies at the end of the twentieth century. Population and Development Review, 33(1), 129–148.

Hu, Y. (1998). A prediction of the trend of population development in urban and rural areas in China. Chinese Journal of Population Science, 10(1), 75–87. (in Chinese).

Jiang, Q., Li, S., & Feldman, M. W. (2013). China’s population policy at the crossroads: social impacts and prospects. Asian Journal of Social Science, 41(2), 193–218.

Kohler, H.-P., Billari, F. C., & Ortega, J. A. (2002). The emergence of lowest-low fertility in Europe during the 1990s. Population and Development Review, 28(4), 641–680.

Morgan, S. P., Guo, Z., & Hayford, S. R. (2009). China’s below-replacement fertility: recent trends and future prospects. Population and Development Review, 35(3), 605–629.

Population Census Office. (2012). Tabulation on the 2010 population census of the People’s Republic of China by county. China Statistics Press. (in Chinese).

Qin, M., Falkingham, J., & Padmadas, S. (2018). Unpacking the differential impact of family planning policies in China: analysis of parity progression ratios from retrospective birth history data, 1971–2005. Journal of Biosocial Science, 50(6), 800–822.

Scharping, T. (2013). Birth control in China 1949–2000: population policy and demographic development. Routledge.

Short, S. E., & Zhai, F. (1998). Looking locally at China’s one-child policy. Studies in Family Planning, 29(4), 373–387.

Sobotka, T. (2017). Post-transitional fertility: the role of childbearing postponement in fuelling the shift to low and unstable fertility levels. Journal of Biosocial Science, 49(S1), S20–S45.

Wang, D., & Chi, G. (2017). Different places, different stories: a study of the spatial heterogeneity of county-level fertility in China. Demographic Research, 37(16), 493–526.

Wang, F., Cai, Y., & Gu, B. (2013). Population, policy, and politics: how will history judge China’s one-child policy? Population and Development Review, 38(s1), 115–129.

Wang, J. (2013). The effects of family planning policy on the birth interval between the first and the second child. South China Population, 28(4), 1–7. (in Chinese).

Wang, J., Ma, Z., & Li, J. (2019). Rethinking China’s actual and desired fertility: now and future. Population Research, 43(2), 32–44. (in Chinese).

Yu, J., & Xie, Y. (2015). Changes in the determinants of marriage entry in post-reform urban China. Demography, 52(6), 1869–1892.

Zeng, Y. (1996). Is fertility in China in 1991–92 far below replacement level? Population Studies, 50(1), 27–34.

Zhang, C., & Liu, H. (2016). Historical analysis of birth spacing policy in China. South China Population, 31(6), 40–56. (in Chinese).

Zhang, C., Liu, H., Wang, Y., & Wang, X. (2016). Study on the composition of second birth interval of China. Population & Development, 22(6), 73–92. (in Chinese).

Zhuang, Y., Jiang, Y., & Li, B. (2020). Fertility intention and related factors in China: findings from the 2017 National Fertility Survey. China Population and Development Studies., 4, 114–126.

Zhuang, Y., Jiang, Y., Wang, Z., Li, C., Qi, J., Hui, W., et al. (2014). Fertility intention of rural and urban residents in China: results from the 2013 national fertility intention survey. Population Research, 38(3), 3–13. (in Chinese).

Acknowledgements

The analysis presented in this article was carried out while Cuiling Zhang was a guest researcher at the Vienna Institute of Demography (VID)/Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital. Her stay was funded by a fellowship by National Scholarship Council of China. We would like to thank Yingan Wang and Krystof Zeman for their assistance. Cuiling Zhang’s research was partially funded by the Major Program of National Social Science Fund of China (16ZDA089).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors contributed equally to this article. CZ and TS jointly designed the study, decided about the data and methods used, drafted the text and prepared its subsequent revisions. CZ performed the data analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare there is no conflict of interest.

Appendix

Appendix

See Fig. 9 .

[Source: Authors’ computations based on 120 Counties Population Dynamics Monitoring System (120 CMS, 2016)]

Absolute changes in mean age at first (MAB1) and second (MAB2) birth (in years) and in mean second birth interval (BI12) in 1989–1999, 2002–2012 and 2012–2016; nine counties in Shandong province (each circle represents one county, the weighted average for the whole province shown by black circles)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, C., Sobotka, T. Drastic changes in fertility level and timing in response to marriage and fertility policies: evidence from Shandong province, China. China popul. dev. stud. 5, 191–214 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42379-021-00089-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42379-021-00089-3