Abstract

Based on a survey implemented in a county in central China, the researchers found it is common for women to experience gender-based violence, especially violence at the hands of intimate partners. About half of men surveyed reported inflicting physical or sexual violence on their female partners. One in five men reported having raped a partner or non-partner woman. The physical, mental and reproductive health of the female and male respondents were found to be significantly associated with women’s victimization and men’s perpetration of intimate partner violence. Gender-based violence, including intimate partner violence, is a construction of the social-ecological system. Four elements that are key to hegemonic masculinity are identified: male decision-making, male reputation, violence and heterosexuality. By positing the four elements as standards that define a “real man”, the domination of men over women is naturalized and legitimized. It is necessary to foster other non-violent and more equitable masculinities.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Since the concept of intimate partner violence (IPV) against women arrived in China in the 1990s, surveys conducted by institutions like the Women’s Federation of China (Tao and Jiang 1993) and China Population and Development Research Center (Zheng and Xie 2004) have demonstrated that IPV is the most common form of violence against women in China. In the effort to eliminate the violence, Chinese scholars have taken into consideration a wide range of topics such as feminist law, ethnic minority issues, marriage markets and the imbalanced sex ratio in their studies of IPV against women (Gu 2014; Song and Zhang 2017; Dan 2018). While more and more international studies point to the strong connection between rigid hegemonic masculinities and violence against women (Schrock and Padavic 2007; Duncanson 2015; Cossins and Plummer 2018; Heilman and Barker 2018), this connection is neglected in China. Understanding gender based violence, especially IPV against women, from the perspective of hegemonic masculinities is thus the goal of our survey.

In May 2011, field research was carried out in a county in central China where the majority of the population lives in rural areas. By multiple stage random sampling, 67 communities were chosen and then 50 interviewees (25 women and 25 men) were randomly selected in each community. We had a response rate of 83.7%, with 1103 women and 1017 men aged 18–49 years completing the female and male questionnaires. Among the respondents, 97.8% of them are currently or have been partnered. The female and male questionnaires and research protocol were provided by the institutions that initiated and provided technical support for the survey. The implementation team made slight adjustments to the questionnaires based on Chinese and local contexts. Personal digital assistants were used to ensure that the responses of the interviewees were strictly confidential. Further information is provided in the Table 8 in Appendix (see Table 1).

2 Intimate partner violence against women

2.1 Prevalence

A breakdown of details reported by men follows in this paragraph. With respect to emotional violence, 28.6% of men reported deliberately frightening or intimidating their female partners, 22.4% reported insulting or deliberately making their partner feel bad about herself, and 14.2% reported deliberately degrading her in front of others. In terms of financial violence, the three most common items concerned men were forbidding women to find work or earn money (10.6%), male partners who spent their own earnings on alcohol and cigarettes although they knew their female partners could not support the family alone (7.7%), and forcing the female partner out of the place of residence (7.2%). In terms of physical violence, pushing or shoving was the most common type (32.8%), slapping or throwing things at women was second (29.8%), and striking women with fists was third (17.8%). With respect to sexual violence, the most common occurrence was the man insisting on sex when the female partner was unwilling, because the man felt entitled to sex with the woman who was his wife or girlfriendFootnote 1 (15.0%). In other cases the man physically forced his female partner to have sex (12.1%). Both of these behaviors are categorized as partner rape. In terms of the lifetime prevalence of partner rape, 14.3% of male respondents reported having perpetrated partner rape and 9.9% of female respondents reported being the victim. The items partner rape and males forcing female partners to watch phonography or perform sexual acts they do not want are classified as sexual violence. In addition, based on reports from women, the prevalence of emotional, physical and sexual violence inflicted by male partners during the female partner’s any of pregnancy were 13.1%, 3.6% and 5.5%, respectively.

Compared with to the instances of IPV documented above, men controlling the behavior of female partners was much more common. A total of 91.0% of men reported having done this at some point during their lives and 86.4% of women reported being controlled at some point. Among the specific items of men controlling the behavior of female partners, the most common is the male partner having more power to make big decisions (72.4%), followed by the male partner not allowing the female partner to wear certain items of clothing (45.8%) and getting angry if the female partner asks him to use a condom (40.3%).

Women often experience more than one type of IPV. Among women who reported experiencing emotional, financial, physical or sexual IPV, 43% of them experienced only one type, 30% experienced two types, 20% experienced three types and 8% experienced four types. Based on the reports of male perpetrators, the four percentage were 36%, 34%, 22% and 9%, respectively.

With respect to emotional, financial, physical and sexual IPV during the 12 months prior to the survey date, the prevalence of perpetrations reported by men were 19.1%, 10.5%, 14.4% and 7.5%, respectively, and the prevalence of victimizations reported by women were 10%, 6.9%, 6.8% and 3.3%, respectively.

2.2 Health consequences and seeking help

The statistics show the ratio of women injured from IPV was alarmingly high. Among 364 women who reported being victims of physical IPV, 40.7% (n = 148) suffered injuries including sprains, burns, knife cuts, bone fractures, lost teeth and other injuries, or had to receive medical care or be hospitalized. With respect to the severity of physical IPV injuries, 34.5% of 148 injured women were bedridden for a period of time, had to take work leave, or had to receive medical care. Beside these physical injures, IPV harmed women in other ways. Compared to women who never experienced IPV, the possibility that women who experienced IPV would suffer from mental and/or reproductive health problems was significantly higher (see Table 2 below).

Many women who are victims of IPV do not seek help. Among 364 women who reported experiencing physical IPV, 60% kept silent, only 6.6% reported the IPV to the police, 10% sought medical help and 36.8% told family members. Among 24 women who reported IPV to the police, 11 women did not report the details of how the police reacted to their reports, only one woman got the chance to open a court case, three women were sent away, and nine women were asked to compromise with their partners. Among the women who sought medical help, only half of them (n = 30) told the truth about how they had been injured. Of the 133 women who told family members about the IPV, nearly half of them (44.4%) were not supported by the family. Instead what they said was treated with indifference, or the family blamed the woman for causing the IPV or she was told to keep silent. In 24.8% of the cases, families were supportive, among other things, suggesting the women report the matter to the police. In 30.8% of the cases, the family’s reactions were ambiguous.

Women who claimed to be victims of rape or attempted rape by non-partners had similar experiences. Among 176 women who reported experiencing such violence, 72% kept silent and the rest sought help from family, hotlines, the local Women’s Federation or community committee, medical personnel or the police. Among 14 women who reported to the police, 8 women had cases opened. Among 30 women who told their families about being victims of sexual violence, nearly half of them (43.3%) were treated with ambivalence, 30% were not supported and 26.7% were supported.

3 Men’s childhood trauma and the rape of non-partners

3.1 Childhood trauma

Data for five kinds of childhood trauma were collected and are presented below. Hunger here refers to not enough food during childhood. Three behaviors are defined as neglect: living in different households (not with parents) at different times during childhood; parents did not look after the child due to alcohol or drug abuse; or the child spent nights outside the home and adults at home did not notice. Emotional violence includes the following behaviors of parents or teachers: scolding children for being lazy, stupid or weak; or humiliating children in public. Children who witness their mother being beaten by her husband or boyfriend are also victims of emotional violence. Physical violence refers to children being beaten by hard objects, being scarred by beatings, and being physically punished by teachers or principles. The following items are considered sexual violence against children: other people touching a child’s hips or genital areas, children being forced to touch themselves, children being frightened or threatened into having sex with others, or children having sex with men or women 5 years older than they are.

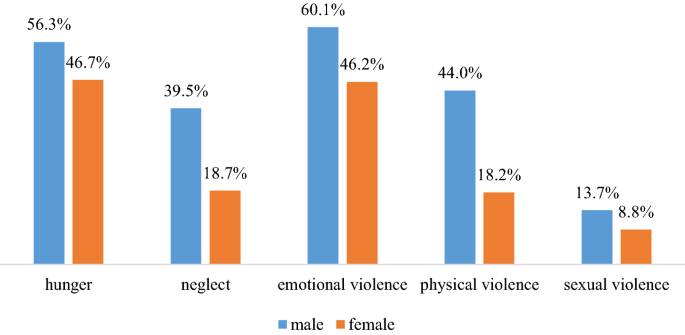

As Fig. 1 shows, many respondents experienced violence or adversity during childhood and male respondents were more likely than females to be involved (P < 0.0001). Besides the traumas listed in Fig. 1, 24.7% of male respondents reported being bullied at school or in their communities during childhood, and 21.8% reported bullying others.

Source as Table 1

The prevalence of childhood trauma reported by male and female respondents.

3.2 Rape against non-partners

This study investigated men raping non-partner women. This included a man forcing or persuading a woman to have sex against her will, or a man having sex with a woman who was unable to give consent because of excessive alcohol or drug consumption. Gang rape, in which a woman was forced or persuaded to have sex against her will with more than one man, was also investigated. In order to present non-partner rape in context, data on partner rape are also listed in Table 3. Although the majority of rapes are partner rapes, as indicated in Table 3, women also face the risk of non-partner rape. One in five women reported being the victim of rape or attempted raped by non-partner men.

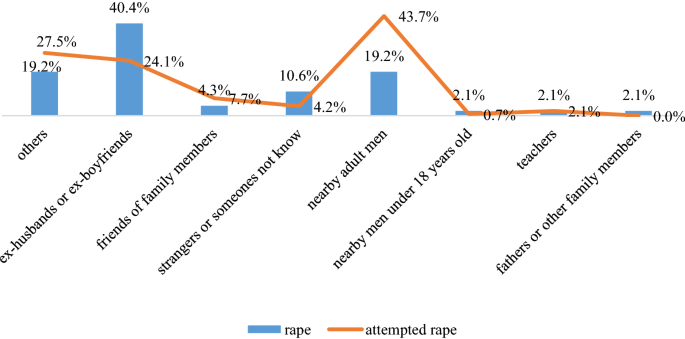

Regarding the motivation of rape, according to 222 male respondents who reported raping or attempting to rape non-partner women, the most common motivation was a feeling of male sexual entitlement. This included the man wanting to have the woman sexually, wanting to have sex, or wanting to show that he could have sex. Among these male respondents, 86.1% reported being driven by sexual entitlement. As well as sexual entitlement, 58% of the men reported being bored or seeking fun, 43% were angry or wanted to punish the woman, and 24% reported they had been drinking alcohol. Figure 2 indicates that some men’s sexual entitlement towards a women did not stop after the end of an intimate partner relationship. In fact ex-husbands and ex-boyfriends were the most likely perpetrators of non-partner rape. A look at the information reported by males who acknowledged having raped a woman, 91% of them committed rape for the first time between the ages of 15 and 29 years old, and 19.8% of the men raped more than one women.

Source as Table 1

Information on the perpetrators of 47 non-partner rapes and 145 attempted rape, as reported by women.

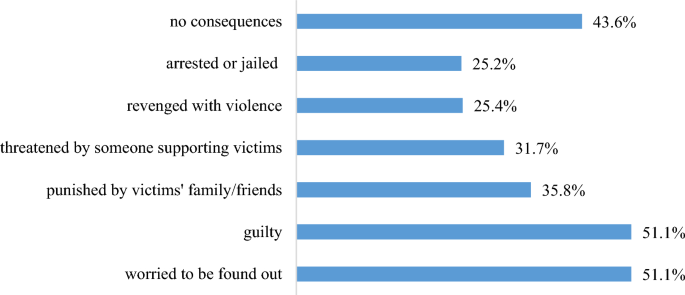

As shown in Fig. 3, among 222 men who reported raping or attempting to rape non-partner women, nearly half of them reported suffering no consequences and only one quarter experienced legal repercussions. These findings correlate with the fact that about three quarters of women respondents kept silent after experiencing rape or attempted rape by non-partners.

Source as Table 1

The consequences of rape and attempted rape of non-partner women, as reported by male perpetrators.

4 Hegemonic masculinity and the risk factors of gender-based violence

4.1 Hegemonic masculinity

The views of the respondents on gender, femininities and masculinities were evaluated on several scales and Table 4 summarizes the specific elements of hegemonic masculinity. All except one of the items were supported by more than half of the male and female respondents.

There are two contradictions in Table 4. First, while almost every male and female respondent agrees in the abstract principle that women and men should be treated equally, more than half of them also agree that men have more privileges than women when it comes to decision-making and sex life. The second contradiction is that, although more than 80% of male and female respondents agree men should share in the housework, more than half also consider looking after family members as women’s paramount duty. The gap between their attitudes and behaviors is greater for male respondents. While Table 4 shows that 92% of male respondents agree women should not be beaten in any situation, 44.7% of them reported inflicting physical IPV against women.

Why are there such striking contradictions? Table 4 reveals four key elements of hegemonic masculinity that provide at least part of the answer: (1) Men should decide important issues; (2) Men should be tough and use force if necessary; (3) A man should not beat a woman unless the woman challenges the man’s reputation; and 4) Men have to be heterosexual and it is in the nature of men to need sex more than women. By establishing these four elements above as a standard that defines “real men”, men’s domination over women is naturalized and legitimized. Such a definition of masculinity has negative ramifications for the notion of gender equality and can help to explain why there is such a large gap between male attitudes and behaviors. If hegemonic masculinity is the norm, gender equality does not mean that men and women should be treated the same, it means that men should treat women according to their “real” natures. In a world where men should decide important issues, be strong and use force if necessary, and need sex more than women, it becomes a simple matter for a man to justify forcing sex on an unwilling woman (i.e. raping a woman)—this is simply a manifestation of the natural order of things. While most people, men and women, agree that gender equality is a good thing in the abstract, widely accepted stereotypes of femininity, masculinity and gender differences lead instead to men dominating women and high levels of gender inequality.

Consistent with hegemonic masculinity which encourages men to be tough, use violence and not control sexual desire, male respondents reported a high likelihood of engaging in violent behavior and having unprotected sex. Nearly one in 5 men (18%) reported having participated in some form of violence including owning weapons, fighting with weapons, joining in gangs, being arrested and being in jail. Having unprotected sex was strikingly common. Among 856 men who reported having sexual experiences and answered the related questions, 82.7% of them reported never or seldom using condoms. Among 88 men who had had more than one sex partner during the last 12 month, 78.2% never or seldom used condoms.

IPV against women, one of the most common forms of violence engaged in by male respondents, also harms the male perpetrators. Compared with male respondents who never perpetrated IPV, Table 5 indicates that men who had perpetrated IPV were more likely to experience mental and reproductive health problems.

4.2 Risk factors for gender-based violence against women

Although poverty, low educational level, youth, and job pressures or unemployment are all commonly assumed to be risk factors associated with men perpetrating physical/sexual IPV against women, these are not confirmed by multiple logistic statistics. Table 6 presents the factors that increase the likelihood of a male perpetrating physical IPV against women. These are generational transmission of domestic violence and male domination, a man’s involvement in other types of violence, alcohol abuse, multiple sexual partners and quarrels between partners.

A comparison of Tables 6 and 7 shows that both the likelihood of men perpetrating physical and sexual IPV against women, and the likelihood of men raping partner and non-partner women were increased by three common risk factors: trauma during childhood, involvement in other types of violence, and having multiple sexual partners. Specifically, having experienced sexual violence during childhood and having low support for gender equality were found to be associated with men inflicting sexual violence.

5 Conclusion

Gender-based violence perpetrated by men is constructed within the social-ecological system, which is composed of four concentric circles. The innermost circle is the individual, and for this circle research identifies several risk factors including childhood trauma, involvement in other types of violence, alcohol abuse, multiple sexual partners and low support for gender equality. In the second circle consisting of relationships, male domination within the family, couples quarreling, generational transmission of ideas about unequal gender relationships and the commission of male violence against both females and children are found to be risk factors. The third circle consists of community, and risk factors in this circle are correlated to community responses to IPV and sexual assault against women, and people’s consciousness of and attitude towards the laws and regulations governing IPV and VAW. The outermost circle consists of social norms and the political and economic environments, and researchers find out that in China, social values, social policy, and laws and regulations are permeated with ideas of rigid hegemonic masculinity, and serve to perpetuate gender-based violence, especially IPV against women (Wang et al. 2013; Deng and Shi 2018).

Based on our findings, we have the following core recommendations: (1) The whole society including governments, mass media, communities and schools should recognize rigid hegemonic masculinity and work to eliminate this type of masculinity which perpetuates gender-based violence, especially IPV against women, encouraging instead non-violent masculinities based on gender equality. (2) The laws and regulations to stop IPV against women should be strengthened and stronger implementation and evaluation are needed to ensure that men are unable to commit violence against women with impunity. (3) Governmental agencies and NGOs should provide professional services for abused women, engage men in programs of violence prevention and strive to eliminate childhood trauma for boys and girls.

Notes

A female respondent received a different question asking if she had had sex she did not want with a male partner because she was afraid the man might become violent or hurt her if she refused.

References

Cossins, A., & Plummer, M. (2018). Masculinity and sexual abuse, explaining the transition from victim to offender. Men and Masculinities, 21(2), 163–188.

Dan, S.-H. (2018). New development of female jurisprudence studies: An overview of masters and doctoral theses on female jurisprudence from 2006 to 2015. Journal of Chinese Women’s Studies, 27(3), 119–128.

Deng, Y.-X., & Shi, F. (2018). Dormitory labor regime and male workers: A study on Foxconn factory. Journal of Hunan University, 32(5), 128–135.

Duncanson, C. (2015). Hegemonic masculinity and the possibility of change in gender relations. Men and Masculinities, 18(2), 231–248.

Gu, X.-B. (2014). Gendered suffering-middle-aged Miao women’s narratives on domestic violence in Southwest China. Journal of Zhejiang Gongshang University, 28(4), 3–21.

Heilman, B., & Barker, G., (2018). Masculine norms and violence: Making the connections. https://promundoglobal.org/resources/page/10/?type=reports. Accessed February 12, 2019.

Schrock, D. P., & Padavic, I. (2007). Negotiating hegemonic masculinity in a batterer intervention program. Gender and Society, 21(5), 625–649.

Song, Y.-P., & Zhang, J.-W. (2017). Less is better? The effects of imbalance in sex ratio in the marriage market on domestic violence against women in China. Journal of Chinese Women’s Studies, 26(3), 5–15.

Tao, C.-F., & Jiang, Y.-P. (1993). An overview of Chinese women’s social status. Beijing: Chinese Women Publisher.

Wang, X. -Y., Jiao, D. -P., & Yang, L. -C. (2013). Masculinities and gender-based violence in transitional China. China Office of UNFPA.

Zheng, Z. Z., & Xie, Z. M. (2004). Migration and rural women’s development. Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press.

Acknowledgements

The research is funded by China Office of United Nation Population Fund, technically supported by Partners for Prevention, an Asia–Pacific programme jointly established by United Nations Development Programme, United Nation Population Fund, UN women and UN Volunteers, and conducted by the Anti-Domestic Violence Network of China and the Beijing Forestry University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Rights and permissions

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, X., Fang, G. & Li, H. Gender-based violence and hegemonic masculinity in China: an analysis based on the quantitative research. China popul. dev. stud. 3, 84–97 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42379-019-00030-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42379-019-00030-9