Abstract

The Australian Outdoor Health (OH) sector provides diverse practices that support an interconnected human and ecological approach to health and wellbeing. There is an urgent need for the OH sector to develop a comprehensive ethical practice framework, to enable professional recognition and other initiatives to progress. This would bring the sector in line with similar health and wellbeing occupations including social work, psychology, and counselling that have established professional recognition. A key feature of professional recognition is the acceptance of a Code of Ethics or Ethical Framework to guide practice and enhance standing in the field. This scoping review of the literature is undertaken to aid in developing an OH ethical practice framework. Findings suggest the framework should incorporate two overarching themes of beneficence and nonmaleficence, and contain six guiding principles: diversity, equity, advocacy, justice, accountability, and competence. We discuss these findings, situate them within broader OH community and health sector discourses, and make recommendations for establishing an Australian ethical practice framework to assist the move towards professional recognition and drive ethical OH practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction and background

In Australia, Outdoor Health (OH) is a recent umbrella term adopted and promoted by the Australian Association for Bush Adventure Therapy (AABAT), with the aim of creating a ‘bigger tent’ to include a more diverse range of outdoor- and nature-based interventions (AABAT Inc, 2021a). Some of the practice approaches that can be found under the new OH umbrella encompass, therapeutic horticulture (Marsh et al., 2018), equine-facilitated therapies, nature-based therapy (Harper et al., 2019), bush adventure therapy (Pryor et al., 2005), forest therapy (Kotte et al., 2019), ecotherapy (King et al., 2022), and Aboriginal on-Country programs (Atkinson, 2020; Prehn, 2021). Despite the diversity of practices, there is a unifying feature that links these therapeutic approaches: the incorporation of the outdoors and nature—in its many forms—into practice. In this paper, we define OH, in line with the newly established Australian OH representative body, as “nature-based health interventions that intentionally activate human contact with nature to support human and environmental health, wellbeing, and healing” (AABAT Inc, 2021a).

The arrival of a collective, interconnected Australian OH sector has been preceded by more than three decades of research investigating the therapeutic benefits of various outdoor- and nature-based approaches for participants (Bowen & Neill, 2013; Carpenter, 2008; Cianchi, 1991; Itin, 1998; Neill, 2003; Nicholls, 2008; Pryor, 2009). While academic scholarship in this sector has evolved mainly from a starting point that privileged male-dominated, North American and Eurocentric histories of Outdoor and Adventure Therapy (Mitten, 2020), recent years have seen an exponential growth in research literature (Rodríguez-Redondo et al., 2023). Internationally, there is increasing interest in and exploration of the therapeutic benefits of nature connection to improve health and wellbeing and promote healthy communities (Andersen et al., 2021; Chen, 2019; Jones et al., 2021; Robinson et al., 2020; Yessoufou et al., 2020). This scholarship reflects a growing recognition of the interdependency of rich, holistic relationships between place, culture, identity, and health (AABAT Inc, 2020, 2021b; Carpenter & Pryor, 2004). There has been increased integration of traditionally discrete areas of work and knowledges into health domains, including, for example, ecosystem services (Haase, 2021), environmental restoration (Nabhan et al., 2020) and urban design (Lafrenz, 2022). Issues of gender and power (Mitten, 1994, 2020), culture and decolonisation (Prehn & Ezzy, 2020), and coercion and abuse (Dobud, 2021) are part of the new foci of OH studies, as are explorations of the espoused positions of equity, diversity and inclusion (Gray et al., 2022) held by the OH community.

Recognising the increasing scholarly and practice interest in outdoor health interventions, we acknowledge that outdoor- and nature-based practices are not new. While the term OH is recent, the practices themselves are connected to cultures and life-sustaining ways of being that are as old as the human species (Kimmerer, 2020; Sveiby & Skuthorpe, 2006). Although some perspectives still focus largely on the Western domains of health and wellbeing and conceptualise OH as a recent phenomenon (Dobud, 2016; Gass et al., 2020), others, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander scholars are tending toward understanding it as tied to Indigenous cultures, world views and identities (Atkinson, 2020; Carpenter & Pryor, 2004; Prehn, 2021; Pryor, 2006; Sveiby & Skuthorpe, 2006). These ancient origins of the practice have diverse contemporary expressions, incorporating new technologies and acknowledge the interdependence and intradependence of ecological systems (Ludy & Perry, 2010; Perry & Ablon, 2019; Porges, 2011; Pretty et al., 2017; van der Kolk, 2014). Collaborative OH trans-cultural and trans-disciplinary partnerships have enabled improved understandings of the range and impacts of culturally diverse human-nature relationships across time that orientate towards holistic health and sustainability (AABAT Inc, 2008, 2020; Carpenter & Pryor, 2004; Pryor & Carpenter, 2002).

Nevertheless, taking people with specific health and wellbeing needs, and physical and mental health challenges, into outdoor settings to connect with nature involves a particular level of risk (Hooley, 2016; King et al., 2022). These are risks that indoor health services with more stable, predictable, and controllable environments do not incur. Risk, however, can be ameliorated through considered, ethical practice (Reese, 2016). Risk also needs to be balanced against the multifarious health and wellbeing benefits not afforded by indoor settings (Chen, 2019; Jordan, 2015). Several studies, for example, have shown the outdoors delivers broad-ranging mental, emotional, physical, social, and ecological health benefits (Cooley et al., 2020; Frumkin et al., 2017); improvements in physical, mental and spiritual health (Roberts et al., 2021); reduced health disparities (Rigolon et al., 2021), and decreased loneliness and improved social connection (Leavell et al., 2019). From Indigenous perspectives, enhanced physical and mental health benefits have been shown, as well as improvements in the sense of self and cultural identity (Prehn, 2021).

Evidence suggests that OH practices support work across many areas identified by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2019) in the Australian Burden of Disease Study. These include but are not limited to: youth and adult mental health treatment (Elsey et al., 2016; Swinson et al., 2019) and recovery (Howarth et al., 2018); Indigenous health services (Prehn & Ezzy, 2020; Ritchie et al., 2014); social isolation (Leavell et al., 2019); trauma recovery (Avila & Holloway, 2011; Knowles et al., 2019, 2020; Rakar-Szabo et al., 2019); and chronic illness support (Banaka & Young, 1985; Buckley & Brough, 2017; Zhu et al., 2017). Overall, the variety of benefits to a range of population groups and across several areas suggests the OH sector is characterised by a malleability that promises the capacity to make meaningful contributions to the health sector. Inclusion within the health sector highlights the question of what constitutes safe and ethical practice. As the field of OH develops, the challenges associated with practising in outdoor environments will require ongoing close and critical consideration. For the OH sector to be recognised more broadly as a safe and effective standalone profession, it must ensure it adheres to a strong ethical practice framework that can cater to the diverse array of approaches used.

By way of comparison, the Australian Association of Social Workers has an established Code of Ethics (AASW, 2020), and the Australian Psychology Society also have a recognised professional Code of Ethics (APS 2007). Although there is a set of ethical principles for the bush adventure therapy field (AABAT Inc, 2009) that have been used to assess program quality (Pryor et al., 2018), the OH sector lacks a shared comprehensive ethical practice framework.

This paper explores current published literature on ethical issues within and surrounding OH practices and considers how this can inform the development of an Ethical Practice Framework. We aim to answer the question:

What key ethical considerations are necessary to develop an Australian Outdoor Health Ethical Practice Framework?

This paper responds to calls from previous research about the lack of dialogue and research on ethics related to care in the OH sector. Previous research exploring ethics within the field has focused on a narrower group of ‘outdoor therapies’ such as forest therapy, adventure therapy (Harper & Fernee, 2022) and ecotherapy (King et al., 2022) or addressed specific ethical issues such as involuntary service user participation (Dobud, 2021) or gender and power relations (Mitten, 1994, 2020). This paper extends this scholarship through an investigation of ethical issues found in a broader range of OH approaches and identifies several key ethical themes that are common within the literature.

Ethics is a subfield of philosophy focused on the moral principles that govern a person’s behaviour or the conducting of an activity. Ethics can be traced back to Ancient Greece, and the Greek word ēthikos, meaning ‘the moral art’ or ‘character’ closely related to another Greek word, ēthos meaning ‘custom’ (Partridge, 1990). Within the field of ethics, there are several applied areas, such as bioethics (Harris et al., 2023), and one that holds particular relevance for OH is environmental ethics. Unlike narrower fields of ethics such as bioethics, environmental ethics provides a useful broad ecological lens through which we can view OH practice. Des Jardins (1997), in his work on environmental ethics, encourages us to critically reflect on our held worldviews, particularly concerning our view of the interrelationship between people and place. As the field of OH is deeply intertwined with the natural environment, health and sustainability, Des Jardins’ (1997) approach is particularly relevant.

In this paper we extend this idea further to engage in critical reflection about views concerning the relationship between people, culture, place, and planet. Through critical engagement with environmental and ecological ethics alongside human and health ethics, an ethical practice framework for the OH sector can maintain focus on what provides this field of practice with its unique identity: the human-nature connection.

Methodology and method

Guided by the understanding that social research is by nature subjective, researchers should state their social positioning and standpoint (Walter, 2019). We acknowledge that we four authors are academics with a keen sense of the holistic benefits that nature connection can provide. As a result, we are all committed to progressing the OH sector. Three authors of this paper identify as white Anglo-Australians, and one as Worimi (Australian Aboriginal). Our social and cultural positionings have shaped the review process from conceptualisation and analysis through to findings and dissemination (Walter 2019).

Method

Scoping reviews allow opportunities for a rich exploration of published research across diverse topics (Bell et al., 2018). This paper uses a scoping review method to explore ethical issues in the Australian OH sector to progress the development of an Ethical Practice Framework and to enhance practice. This method allows for mapping a range of ethical issues and their relevance to the OH sector. The data is collected using the Arksey and O’Malley (2005) five-step process:

-

i)

identifying the review question/s;

-

ii)

identifying relevant studies;

-

iii)

study selection;

-

iv)

charting, collating, summarising; and

-

v)

reporting the findings.

Search strategy

Using an abridged form of the recommended JBI process (Peters et al., 2020), our search strategy commenced with preliminary explorative searches on PubMed and Scopus to establish appropriate search terms. The complete scoping review was conducted over 10 months in 2022–2023 and used Scopus, PubMed, and Informit, One SCOPUS search is provided as an example here (Fig. 1).

Eligibility and inclusion criteria

The table above (Fig. 2) details the inclusion and exclusion criteria. To further refine our criteria, we define ‘ethics’ as the systematic consideration of moral principles, or the application of a system of moral principles that are relevant to a given definable context (Macquarie Dictionary, 2021).

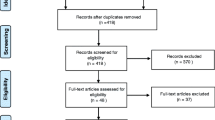

Prisma chart

The following PRISMA chart (Fig. 3) depicts the process of finding relevant studies and deciding which to include.

Data extraction and analysis

Studies that met inclusion criteria were transferred to Nvivo Version 12 for data extraction and subsequent coding. Categories for data extraction included: author, year, location, study type, purpose, OH modality/ies, ethical issues, and study limitations. In total, 24 studies met the inclusion criteria [Appendix Table 1].

The included studies were initially coded by the primary author, who identified the dominant "meaning units" in the papers. Other authors then reviewed these. Overarching themes, themes, and subthemes were initially generated inductively from the analysis and synthesis of the codes and then revised through a reflexive and iterative process of discussion, review, and reflection by all authors (Braun & Clarke, 2019). This process of thematic analysis discussions generated the patterns of ethical issues within the papers and were also informed by the existing Codes of Ethics for three Australian allied health professions with similar therapeutic aims (AASW, 2020; APS Ltd, 2018; PACFA, 2017).

Findings

The findings from the 24 studies indicated 55 ethical topics, and the analysis generated two overarching themes and six sub-themes [Appendix Table 2]. The two overarching themes were beneficence and nonmaleficence, and the six sub-themes are diversity, equity, advocacy, justice, accountability, and competence. These themes speak directly to the research question: What are key ethical considerations for developing an Australian OH Ethical Practice Framework?

Beneficence & nonmaleficence: doing good and avoiding harm

Beneficence and nonmaleficence were the dominant themes across the included studies. Ethical topics, issues or principles were expressed in terms of having potential to either do good (beneficence) and/or avoid harm (nonmaleficence), and the relationships between the two concepts. For example, King et al. (2022) describe how counselling in nature often leads to more egalitarian relationships with reduced power imbalances that tend to occur in four walls. At the same time, they note how this context places greater responsibility on practitioners to adhere to principles of informed consent and to negotiate with participants about the limitations to autonomy and choice necessary for this context (King et al., 2022). Hooley (2016) describes the paired ideas of beneficence and nonmaleficence as a continual anchor point for all therapeutic activity that invites extra consideration in OH contexts. King et al. (2022) speak of beneficence and nonmaleficence as two key principles, alongside others, that govern bio-medical ethics—a lens through which they address issues related to OH practice.

Advocacy

There was a strong call from various authors for the need to increase awareness of the benefits of OH practices within health and related sectors (Drost, 2019; King & McIntyre, 2018; Lokugamage et al., 2020; Sacco, 2021). This advocacy theme was present in ten of the 24 scoping review studies, across diverse cross sections of the community including benefits for early life (Benz et al., 2022) to older people (Taranrød et al., 2021). Moriggi et al. (2020) suggested advocacy for developing alliances and relationships across all levels of society, informed by the ecological and holistic health concepts common within OH practices, was important. Four studies discussed a potential agenda for OH practices which was to contribute to an ‘ecological consciousness’ that would, in various ways, address the global issue of planetary health (Benz et al., 2022; N. J. Harper & Fernee, 2022; Lokugamage et al., 2020; Plesa, 2019). For some, this also included promoting consideration of how various OH practices can directly contribute to climate action (Benz et al., 2022; Hall, 2019; Moriggi et al., 2020; Stålhammar & Thorén, 2019).

Equity

Aspects of equity were present across 13 of the 24 studies that met scoping review criteria. Within these the most significant equity issues discussed were access to nature (Drost, 2019; Hall, 2019; King et al., 2022; Moriggi et al., 2020; Reese, 2018), access to diverse culturally appropriate health practices (Drost, 2019; Ljubicic et al., 2021; Lokugamage et al., 2020; Tujague & Ryan, 2021) and, accessibility of OH services to people of all abilities (Hooley, 2016; Jeffery & Wilson, 2017; King et al., 2022; Reese, 2018). Accessing funding in various forms was discussed as a major barrier to the provision of OH services (Drost, 2019; King et al., 2022; Ljubicic et al., 2021; J. W. Long et al., 2020; Pearce, 2018; Reese, 2018). The disparity in access between rural and urban settings (Hooley, 2016; Ljubicic et al., 2021; Moriggi et al., 2020), and the time available to provide OH services (Bradford, 2019; Reese, 2018) were also raised.

Accountability

Accountability was discussed from a range of different angles. These included mechanisms for ‘accountable practice’ such as: obtaining appropriate training for the type of OH practice being offered (Hooley, 2016; King et al., 2022); ensuring practice is based on the best available evidence (Hooley, 2016; King et al., 2022); measuring outcomes of practice and gathering participant feedback (Harper & Fernee, 2022; Hooley, 2016; Moriggi et al., 2020); maintaining adequate insurances (King et al., 2022); and, ensuring good record keeping (Hooley, 2016; King et al., 2022). Several papers contained suggestions for maintaining ongoing accountability, such as ensuring practitioners undertake regular supervision, engaging in communities of practice (Haber & Deaton, 2019; Hooley, 2016; King et al., 2022), and practitioners attending to their areas of privilege (Benz et al., 2022; King et al., 2022; Lokugamage et al., 2020; Plesa, 2019; Sacco, 2021; Tujague & Ryan, 2021). Accountability for the ongoing sustainability of practice was raised as both an individual and a systemic issue that the OH sector will need to consider (Drost, 2019; Harper & Fernee, 2022; King et al., 2022; Ljubicic et al., 2021; J. W. Long et al., 2020; Moriggi et al., 2020). Some authors also tied accountability to greater environmental sustainability and planetary health obligations (Benz et al., 2022; Hall, 2019; Lokugamage et al., 2020; Pearce, 2018; Plesa, 2019).

Justice

Issues of justice were evident in 17 of the 24 studies and include the related principles of rights, dignity, respect, and care for people, place and planet. Power relations were discussed in some papers (Bradford, 2019; Drost, 2019; Haber & Deaton, 2019; King & McIntyre, 2018; Lokugamage et al., 2020) alongside practice related issues of transparency, informed consent, coercion, confidentiality, and participant autonomy which are significant areas of discussion due to the nuanced contextual, cultural, and political landscape of OH practices (Bradford, 2019; Haber & Deaton, 2019; Hall, 2019; Harper & Fernee, 2022; Hooley, 2016; King & McIntyre, 2018; King et al., 2022; Reese, 2018; Stea et al., 2022; Taranrød et al., 2021). The potential impact of conflicting values between practitioners and participants was thought to be more prevalent in the OH context due to often strong pro-environmental values held by practitioners (Bradford, 2019; King & McIntyre, 2018; King et al., 2022; Lokugamage et al., 2020; Moriggi et al., 2020; Pearce, 2018; Reese, 2018).

Some authors stepped back from the immediacy of practice to consider social, cultural, and ecologic factors of relevance. Significantly, the ongoing injustices of colonisation and the potential for cultural appropriation in OH practices were spelled out (Lokugamage et al., 2020; Tujague & Ryan, 2021). Some authors called for an orientation toward cultural humility and the adoption of a decolonising attitude alongside meaningful recognition of Indigenous histories, living culture and healing practices (Drost, 2019; Hall, 2019; Harper & Fernee, 2022; King et al., 2022; Ljubicic et al., 2021; Lokugamage et al., 2020; J. W. Long et al., 2020; Moriggi et al., 2020; Pearce, 2018; Tujague & Ryan, 2021).

Diversity

In this paper, diversity refers to the variety of practices, practice frameworks, and health disciplines that comprise the OH sector and impact ethical framework development considerations. For example, Moriggi et al. (2020) describe how green care practices cross disciplinary lines (including health and wellbeing, social inclusion, education, personal development, etc.) to meet specific needs. King and McIntyre (2018) share the value of diversity, indicating that practitioners can bring a range of structures, theoretical orientations and ways of incorporating nature into their practice that match participant needs. For some, the inclusion of culturally diverse and appropriate practices was important (Drost, 2019; King et al., 2022; Ljubicic et al., 2021; Lokugamage et al., 2020; Tujague & Ryan, 2021), and for others, it was tailoring services to meet particular participant needs (Harper & Fernee, 2022; Hooley, 2016; Lokugamage et al., 2020; Moriggi et al., 2020).

More than 20 different OH approaches were named. These included a range of psychotherapeutic techniques such as: environmental psychology (Benz et al., 2022), ecopsychology (Plesa, 2019), nature-based counselling & EcoWellness (Reese, 2018), psychotherapy outdoors (Hooley, 2016), and ecotherapy (King & McIntyre, 2018; King et al., 2022). Further, a range of outdoor therapies were represented: adventure therapy, bush adventure therapy, forest therapy, surf therapy, nature-therapy, wilderness therapy, friluftsterapi (therapy in the open air), outdoor family therapy, and more (Harper & Fernee, 2022; Jeffery & Wilson, 2017; Stea et al., 2022). Indigenous healing practices featured strongly (Drost, 2019; Lokugamage et al., 2020; Tujague & Ryan, 2021), alongside cultural land-based practices (Ljubicic et al., 2021; Tujague & Ryan, 2021). Other practices that involve attending to the land include: ecological/ecosystem restoration (M. J. Long, 1993; Moriggi et al., 2020; Pearce, 2018; Stålhammar & Thorén, 2019), care farming (Taranrød et al., 2021), and green care practices (rewilding, ecotourism, therapeutic horticulture, and more) (Moriggi et al., 2020; Stålhammar & Thorén, 2019). Additional approaches found in the scoping reviewing included: animal assisted therapy (Galardi et al., 2021); experiential learning (Bradford, 2019; Haber & Deaton, 2019; Kolb & Kolb, 2018), and outdoor occupational therapy. Overall, the diversity of practice present within OH may form one of the sectors most significant defining features.

Competence

The theme of competence refers to the complex and diverse skills and knowledge required for effective OH practice, as well as the various training pathways that practitioners may take (Benz et al., 2022; Drost, 2019; Hooley, 2016; Jeffery & Wilson, 2017; King & McIntyre, 2018; King et al., 2022; Lokugamage et al., 2020). Competence-related ethical issues included values, attitudes, knowledges, and skills. Values and attitudes toward practice included such things as an orientation towards social, cultural, and ecological justice (Plesa, 2019), ecological orientation to practice (Benz et al., 2022; Galardi et al., 2021; Hall, 2019; Harper & Fernee, 2022; King et al., 2022; Lokugamage et al., 2020; Pearce, 2018; Plesa, 2019; Reese, 2018), valuing diversity and inclusion (King & McIntyre, 2018), intentionality (Hooley, 2016; Jeffery & Wilson, 2017; King & McIntyre, 2018; King et al., 2022; Pearce, 2018; Reese, 2018), heart (Moriggi et al., 2020; Pearce, 2018), and humility (Lokugamage et al., 2020; Tujague & Ryan, 2021).

There was a range of areas of knowledge and theory that were emphasised. These included theoretical knowledge of trauma-informed practices (Haber & Deaton, 2019; King et al., 2022; Lokugamage et al., 2020; Sacco, 2021; Tujague & Ryan, 2021), attachment theory (Benz et al., 2022; Pearce, 2018; Reese, 2018; Stålhammar & Thorén, 2019), and experiential learning theories (Haber & Deaton, 2019; Kolb & Kolb, 2018). There were several contextual bodies of knowledge raised, such as knowledge of experiential and outdoor activities (Drost, 2019; King & McIntyre, 2018; King et al., 2022; Kolb & Kolb, 2018; Ljubicic et al., 2021; Moriggi et al., 2020; Pearce, 2018; Stålhammar & Thorén, 2019), environmental knowledge and skills, and knowledge about Indigenous history, living culture, and healing practices (Drost, 2019; Hall, 2019; Harper & Fernee, 2022; King et al., 2022; Ljubicic et al., 2021; J. W. Long et al., 2020; Moriggi et al., 2020; Pearce, 2018).

Three groups of ethical issues relating to practitioner skills were articulated. The first was related to planning—assessing need (Hooley, 2016; King & McIntyre, 2018; King et al., 2022; Reese, 2018), long-term planning (Ljubicic et al., 2021; Moriggi et al., 2020; Stea et al., 2022; Tujague & Ryan, 2021), co-design, and tailoring services to individual, group and community needs (Harper & Fernee, 2022; Hooley, 2016; Lokugamage et al., 2020; Moriggi et al., 2020). The second was related to being adaptive to different relational contexts—working with individuals or working with groups (Bradford, 2019; Haber & Deaton, 2019; Jeffery & Wilson, 2017), managing dynamic boundaries (Harper & Fernee, 2022; King et al., 2022; Reese, 2018), managing dual relationships (Bradford, 2019; Haber & Deaton, 2019; King et al., 2022; Moriggi et al., 2020), and managing the complex interplay between individual, group, culture, activity, and environment (Bradford, 2019; Haber & Deaton, 2019; Hooley, 2016; Lokugamage et al., 2020; Pearce, 2018). Finally, the need to engage in rigorous reflective practice and supervision was raised as a method of contributing to practitioner competence, especially because of the diverse practice contexts that may be encountered across OH (Bradford, 2019; King et al., 2022; Moriggi et al., 2020; Reese, 2018).

Discussion

The scoping review findings highlight many important elements required for an Australian Outdoor Health ethical practice framework. In addition, two key understandings emerge: first that along with theoretical and practical knowledge, OH practitioners need to adopt an ongoing commitment towards ethical endeavour within their practice, particularly when working with vulnerable and marginalised people. This includes but is not limited to critical engagement with their own value-based positions and increasing attention to the relationship between human health and ecological sustainability. Second, that practitioners should be able to identify and understand factors that enable and inhibit ethical practice and apply this across different systemic scales. Below, we explore each of these ideas further.

Ethical endeavour within practice

The ethical principles of beneficence and non-maleficence form the bedrock of many contemporary health ethics codes, yet despite the espoused importance of these principles and the skills and knowledge held by many practitioners, various harms occur in the outdoors (Leemon & Schimelpfenig, 2003; McLean et al., 2022; Russell & Harper, 2006; Wells & Warden, 2018). The amelioration of harms in OH practice involves not only the development of practice skills and theoretical knowledge but also development of understanding and awareness of ethics. Ethical endeavour is something people engage in every day, as we deliberate about choices we make for ourselves and those around us in our personal and professional lives. Ethical endeavour also requires us to assess our personal and professional values alongside the issues we encounter in practice. Nevertheless, Bennet (2015) observes and is concerned that ethics and ethical endeavour are often seen as sitting outside the ordinary day-to-day encounters of life in contemporary Western culture. It follows that an ethical practice framework for OH must guide practitioners towards practice skills, theoretical knowledge and also the adoption of a commitment towards ‘every-day’ ethical deliberation. Particularly ethical deliberation concerning better understanding the effects of personal and professional values on practice, and critical reflexive engagement with practice issues.

Consideration of how people working in helping professions identify, carry and express their values in practice is debated fervently. This review highlighted the importance of several broad value positions that appear to be taken up by many authors. Ecological sustainability and pro-environmental attitudes (Benz et al., 2022; Galardi et al., 2021; Hall, 2019; Harper & Fernee, 2022; King et al., 2022; Lokugamage et al., 2020; Pearce, 2018; Plesa, 2019; Reese, 2018); culturally diverse and appropriate health practices (Drost, 2019; King et al., 2022; Ljubicic et al., 2021; Lokugamage et al., 2020; Tujague & Ryan, 2021); and, the value of program co-design and tailoring services to particular individual and group needs (Harper & Fernee, 2022; Hooley, 2016; Lokugamage et al., 2020; Moriggi et al., 2020). In some instances, these values have led to tension or values conflicts (Bradford, 2019; King & McIntyre, 2018; King et al., 2022; Lokugamage et al., 2020; Moriggi et al., 2020; Pearce, 2018; Reese, 2018). In relation to pro-environmental values, some authors invite caution against letting personal values obscure participant needs (King & McIntyre, 2018). Others suggest this is not so much a problem, because pro-environmental values generally align with ethical practice, health and wellbeing outcomes, and environmental health outcomes (Reese, 2018). Regardless, any OH ethical practice framework should support practitioners to identify and debate the impact of their personal and professional values to the point where they can come to an ethical practice position. This process is consistent with a shift in the helping professions over recent decades that sees practitioners increasingly explicate value positions and highlight the role of politics and social action within their work (Reynolds, 2013; Siegenthaler & Boss, 1998; Spade, 2010).

Holding a commitment towards critical reflexive deliberation within practice is aligned with many of the ethical principles identified in this review, such as: humility (Lokugamage et al., 2020; Tujague & Ryan, 2021), dignity (Harper & Fernee, 2022), and co-creation/co-design (Harper & Fernee, 2022; Hooley, 2016; Lokugamage et al., 2020; Moriggi et al., 2020). It is also supportive of better understanding social privilege (Benz et al., 2022; King et al., 2022; Lokugamage et al., 2020; Plesa, 2019; Sacco, 2021; Tujague & Ryan, 2021), continued effort towards decolonising practices (Drost, 2019; King et al., 2022; Ljubicic et al., 2021; Lokugamage et al., 2020; Tujague & Ryan, 2021), and better understanding how power operates (Bradford, 2019; Drost, 2019; Haber & Deaton, 2019; King & McIntyre, 2018; Lokugamage et al., 2020). The range of ethical issues related to the OH sector in part also reflect broader systemic and societal issues. For example, gender, culture and power inequities (Mitten, 1994, 2020), coercive and abusive practices (Dobud, 2021), and the hegemony of white, hyper-masculinized cisgender men (Gray et al., 2022). These broader issues will not be solved via normative ethical positions found in typical bio-medical ethics frameworks, nor will they be resolved through assertion of individualistic rights. Rather, they require a commitment to ongoing, intentional, skilled, critical reflexive deliberation that allows for tentative, revisable decision making, grounded in close attention to the subjective, contextual, and relational realities of the people involved.

A question for future consideration is: how can an Australian Outdoor Health Ethical Practice Framework best cultivate and encourage ongoing critical reflexive deliberation that is necessary for safe and ethical practice?

Ethics across systems

While considering ethics at the coalface of practice is essential (Hooley, 2016; King et al., 2022), so too is the need to address ethics across entire systems of operation. As Hall (2019) highlights, contemplating various systemic layers at which OH operates is necessary for ethical outcomes in practice. Plesa (2019) discusses broader ethical issues of climate change and the need to take up an ecological lens within the psychology profession, and in their work on decolonising the health sector, Lokugamage et al., (2020) demonstrate how this endeavour involves action at individual and organisational levels. The need for addressing ethical issues across systemic scales is further highlighted by McLean (2022) who points to the multi-systemic failures in decision making that have lead to harms occurring in outdoor practices. As such, an OH Ethical Practice Framework will need to guide individuals, organisations, or entities toward identifying relevant systems and developing systemic understandings of ethical issues encountered in practice. Considering the location of ethical issues across systems invites practitioners to take responsibility for understanding the relationship between the problems they see people facing and the contexts in which these issues exist. This type of consideration is not new; for example, systemically oriented therapies (Denborough, 2001; Hedges, 2005; White, 2007), feminist theory (hooks, 2014) and intersectional theory (Joy, 2019) invite reflection on the relationship between difficulties people face and the various structural factors that may be shaping them. However, in health and therapeutic professions that predominantly use the bio-medical model (Peel et al., 2021), systematic considerations can be overlooked and not given appropriate consideration.

In the construction of an OH ethical framework, an understanding of relevant ecological theories will support multi-systemic thinking (Benz et al., 2022; Harper & Fernee, 2022; Lokugamage et al., 2020; Plesa, 2019). For example, Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) Ecological Systems Theory provides a readily accessible construct for mapping issues at a micro, meso, and macro level. Latour’s Actor Network Theory (2005) supports understanding systemic influences of power and agency on ethical practice. Further exploration of the utility and applicability of these theories will benefit the structure of any OH ethical practice framework.

A second question for future consideration is: how can an Australian Outdoor Health Ethical Practice Framework enable individuals, organisations, or entities to identify, understand and respond to societal and systemic ethical issues encountered in practice?

Limitations

This paper has several limitations. First, the scoping review did not include grey literature, principally due to time constraints. Second, the scoping review was limited to literature published in English, excluding studies outside the English-speaking world. The authors acknowledge that this privileges certain knowledges that are generated primarily in the Western world, while marginalising some of those, particularly from the ‘global south’. Third, the OH field is remarkably diverse, and some approaches to health and wellbeing, while relevant, were not conducted outdoors and were not included in this study. Future exploration of ethical issues in OH practice could build upon this study by including studies published in languages other than English and consider the inclusion of grey literature.

Conclusion

Establishing an Outdoor Health ethical practice framework is key to addressing ethical concerns, and to moving towards greater professional recognition for the sector. The findings of this review highlight that ethical issues are of great interest to the OH sector. To our knowledge this review is the first to look at the variety of issues present in a broad range of OH practices. Building from work already done, the findings identify the gamut of ethical issues found in the literature and provide a starting point from which to develop an OH ethical framework for future practice.

Our review demonstrates that an Australian OH ethical practice framework needs to invite practitioners and organisations to consider their work in relation to the overarching principles of beneficence and nonmaleficence, not just at the intersection of practice, but also with regard to the relationship between practice and the social and ecological systems they reside within. We recommend that an Australian OH ethical practice framework should lead practitioners, organisations, and the sector in an ongoing critical consideration of guiding principles such as advocacy, equity, accountability, justice, diversity, and competence. An Australian OH ethical practice framework should consider an appropriate level of theoretical training and experience required by pre-service practitioners to avoid unintentionally harm to already vulnerable and marginalised participants. It will need to be flexible enough to cater for the diversity of practices that exist within the sector, and accessible enough to enable practitioners and organisations to engage with ethical dimensions of practice as a routine part of daily work. Crucially, it will also need to ensure that OH practices are effective, safe, and secure, and that practitioners are competent and accountable.

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

AABAT Inc. (2008). History of the name - Australian Association for Bush Adventure Therapy Inc. Retrieved October 2023, https://aabat.org.au/history-of-the-name/

AABAT Inc. (2009). Ethical Principles - Australian Association for Bush Adventure Therapy Inc. Retrieved October 2023, https://aabat.org.au/ethical-principles/

AABAT Inc. (2020). Nature and Health Symposium. Outdoor Health Australia. Retrieved October 2023, https://outdoorhealth.org.au/nhrpp-symposium/

AABAT Inc. (2021a). About – Outdoor Health Australia. Outdoor Health Australia. Retrieved October 2023, https://outdoorhealth.org.au/about/

AABAT Inc. (2021b). Outdoor Health Symposium. Outdoor Health Australia. Retrieved October 2023, https://symposium.outdoorhealthcare.org.au/

AASW. (2020). AASW Code of Ethics 2020. Australian Association of Social Workers. Retrieved October 2023, https://www.aasw.asn.au/about-aasw/ethics-standards/code-of-ethics/

Andersen, L., Corazon, S. S. S., & Stigsdotter, U. K. K. (2021). Nature Exposure and Its Effects on Immune System Functioning: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 18(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041416

APS Ltd. (2018). APS Code of Ethics. The Australian Psychological Society Limited. Retrieved October 2023, https://psychology.org.au/getmedia/d873e0db-7490-46de-bb57-c31bb1553025/aps-code-of-ethics.pdf

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Atkinson, J. (2020). Human-Nature Connections: Vol. “Nature and Health” Online Symposium [Video]. YouTube - AABAT Inc. - Bundjalung Land. Retrieved October 2023, https://outdoorhealthcare.org.au/event-naidoc-2020-2/

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2019). Australian Burden of Disease Study: Impact and causes of illness and death in Australia 2015. https://doi.org/10.25816/5EBCA2A4FA7DC

Avila, M. A., & Holloway, J. (2011). Connection to nature as an intervention for children exposed to trauma [Doctor of Psychology]. Alliant International University

Banaka, W. H., & Young, D. W. (1985). Community coping skills enhanced by an adventure camp for adult chronic psychiatric patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 36(7), 746–748.

Benz, A., Formuli, A., Jeong, G., Mu, N., & Rizvanovic, N. (2022). Environmental psychology: Challenges and opportunities for a sustainable future. PsyCh Journal, 11(5), 767–773. https://doi.org/10.1002/pchj.585

Bowen, D. J., & Neill, J. T. (2013). A meta-analysis of adventure therapy outcomes and moderators: Pre-post adventure therapy age-based benchmarks for outcome categories. Retrieved October 2023, http://www.danielbowen.com.au/meta-analysis

Bradford, D. L. (2019). Ethical Issues in Experiential Learning. Journal of Management Education, 43(1), 89–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562918807500. Scopus.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The Ecology of Human Development. Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv26071r6

Buckley, R. C., & Brough, P. (2017). Nature, Eco, and Adventure Therapies for Mental Health and Chronic Disease. Frontiers in Public Health, 5, 220. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00220

Carpenter, C. (2008). Changing spaces: Contextualising outdoor experiential programs for health and wellbeing. [Doctoral dissertation, Deakin University]

Carpenter, C., & Pryor, A. (2004). A confluence of cultures: Wilderness adventure therapy practice in Australia and New Zealand. In S. Bandoroff & S. Newes (Eds.), Coming of age: The evolving field of adventure therapy (pp. 224–239). Association for Experiential Education.

Chen, C. (2019). Nature’s pathways on human health. In International Handbook of Forest Therapy (pp. 12–31)

Cianchi, J. (Ed.). (1991). Proceedings of the First National Symposium on Outdoor/Wilderness Programs for Offenders: Birrigai, A.C.T., 2–4 October 1990. Adult Corrective Services

Cooley, S. J., Jones, C. R., Kurtz, A., & Robertson, N. (2020). ‘Into the Wild’: A meta-synthesis of talking therapy in natural outdoor spaces. Clinical Psychology Review, 77, 101841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101841

Denborough, D. (Ed.). (2001). Family Therapy: Exploring the field’s past, present & possible futures. Dulwich Centre Publications

Des Jardins, J. R. (1997). Environmental ethics: An introduction to environmental philosophy (2nd ed). Wadsworth Pub. Co.

Dobud, W. (2016). Exploring Adventure Therapy as an Early Intervention for Struggling Adolescents. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 19(1), 33–41.

Dobud, W. (2021). Experiences of secure transport in outdoor behavioral healthcare: A narrative inquiry. Qualitative Social Work. Scopus. https://doi.org/10.1177/14733250211020088

Drost, J. L. (2019). Developing the Alliances to Expand Traditional Indigenous Healing Practices Within Alberta Health Services. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 25(S1), S69–S77. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2018.0387. Scopus.

Elsey, H., Murray, J., & Bragg, R. (2016). Green fingers and clear minds: Prescribing ‘care farming’ for mental illness. British Journal of General Practice, 66, 99–100.

Frumkin, H., Bratman, G. N., Breslow, S. J., Cochran, B., Kahn, P. H., Lawler, J. J., Levin, P. S., Tandon, P. S., Varanasi, U., Wolf, K. L., & Wood, S. A. (2017). Nature contact and human health: A research agenda. Environmental Health Perspectives, 125(7). https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP1663

Galardi, M., De Santis, M., Moruzzo, R., Mutinelli, F., & Contalbrigo, L. (2021). Animal assisted interventions in the green care framework: A literature review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18). Scopus. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189431

Gass, M. A., Gillis, H. L. ‘Lee’, & Russell, K. C. (2020). Adventure Therapy: Theory, Research, and Practice. Taylor & Francis Group. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/utas/detail.action?docID=6130882

Gray, T., Allen-Craig, S., Mitten, D., & Charles, R. (2022). Widening the aperture: Using visual methods to broaden our understanding of gender in the outdoor profession. Annals of Leisure Research, 25(3), 314–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2021.1899831

Haase, D. (2021). Integrating Ecosystem Services, Green Infrastructure and Nature-Based Solutions—New Perspectives in Sustainable Urban Land Management (pp. 305–318). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-50841-8_16

Haber, R., & Deaton, J. D. (2019). Facilitating an Experiential Group in an Educational Environment: Managing Dual Relationships. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, 69(4), 434–458. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207284.2019.1656078

Hall, C. M. (2019). Tourism and rewilding: An introduction–definition, issues and review. Journal of Ecotourism, 18(4), 297–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2019.1689988. Scopus.

Harper, N. J., & Fernee, C. R. (2022). Unpacking Relational Dignity: In Pursuit of an Ethic of Care for Outdoor Therapies. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 766283. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.766283

Harper, N. J., Rose, K., & Segal, D. (2019). Nature-Based Therapy: A practitioner’s guide to working with children, youth and families. New Society Publishers

Harris, J., Maxwell, H., & Dodds, S. (2023). An Australian interpretive description of Contact Precautions through a bioethical lens; recommendations for ethically improved practice. American Journal of Infection Control, 51(6), 652–659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2022.08.010. Scopus.

Hedges, F. (2005). An introduction to systemic therapy with individuals: A social constructionist approach / Fran Hedges

hooks, B. (2014). Feminist theory: From margin to center. Taylor & Francis Group. Retrieved October 2023, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/utas/detail.action?docID=1811030

Hooley, I. (2016). Ethical Considerations for Psychotherapy in Natural Settings. Ecopsychology, 8(4). https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2016.0008

Howarth, M., Rogers, M., Withnell, N., & McQuarrie, C. (2018). Growing spaces: An evaluation of the mental health recovery programme using mixed methods. Journal of Research in Nursing, 23(6), 476–489. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987118766207. Scopus.

Itin, C. M. (1998). Exploring the boundaries of adventure therapy: International perspectives. Proceedings of the First International Adventure Therapy Conference, Perth, Australia

Jeffery, H., & Wilson, L. (2017). New Zealand Occupational Therapists’ Use of Adventure Therapy in Mental Health Practice. New Zealand Journal of Occupational Therapy, 64(1), 32–32.

Jones, R., Tarter, R., & Ross, A. M. (2021). Greenspace Interventions, Stress and Cortisol: A Scoping Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 18(6). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18062802

Jordan, M. (2015). Nature and Therapy: Understanding counselling and psychotherapy in outdoor places. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315752457

Kimmerer, R. W. (2020). Braiding sweetgrass: Indigenous wisdom, scientific knowledge and the teachings of plants. Penguin Books.

King, B. C., & McIntyre, C. J. (2018). An Examination of the Shared Beliefs of Ecotherapists. Ecopsychology, 10(2), 117–126. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2018.0014. Scopus.

King, B. C., Taylor, C. D., Garcia, J. A., Cantrell, K. A., & Park, C. N. (2022). Ethics and ecotherapy: The shared experiences of ethical issues in practice. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 0(0), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2022.2029512

Knowles, B., Wright, S., & Rae, P. (2019). Roads to Wellness pilot outdoor intervention: Evaluation. Victoria Police

Knowles, B., Pryor, A., & Wright, S. (2020). Roads to Wellness pilot outdoor intervention: Post program evaluation

Kolb, A., & Kolb, D. (2018). Eight important things to know about the experiential learning cycle. Australian Educational Leader, 40(3), 8–14.

Kotte, D., Li, Q., & Shin, W. S. (2019). International handbook of forest therapy. Cambridge Scholars Publisher.

Lafrenz, A. J. (2022). Designing Multifunctional Urban Green Spaces: An Inclusive Public Health Framework. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17). Scopus. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710867

Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social: An introduction to actor-network-theory / Bruno Latour

Leavell, M. A., Leiferman, J. A., Gascon, M., Braddick, F., Gonzalez, J. C., & Litt, J. S. (2019). Nature-Based Social Prescribing in Urban Settings to Improve Social Connectedness and Mental Well-being: A Review. Curr Environ Health Rep, 6(4), 297–308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-019-00251-7. mdc.

Leemon, D., & Schimelpfenig, T. (2003). Wilderness injury, illness, and evacuation: National Outdoor Leadership School’s incident profiles, 1999–2002. Wilderness Environ Med, 14(3), 174–182. https://doi.org/10.1580/1080-6032(2003)14[174:wiiaen]2.0.co;2

Ljubicic, G. J., Mearns, R., Okpakok, S., & Robertson, S. (2021). Learning from the land (Nunami iliharniq): Reflecting on relational accountability in land-based learning and cross-cultural research in Uqšuqtuuq (Gjoa Haven, Nunavut). Arctic Science, 8(1), 252–291. https://doi.org/10.1139/as-2020-0059. Scopus.

Lokugamage, A. U., Ahillan, T., & Pathberiya, S. D. C. (2020). Decolonising ideas of healing in medical education. Journal of Medical Ethics, 46(4), 265–272. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2019-105866

Long, M. J. (1993). Adventure education: A curriculum designed for middle school physical education programs. Doctor of

Long, J. W., Lake, F. K., Goode, R. W., & Burnette, B. M. (2020). How Traditional Tribal Perspectives Influence Ecosystem Restoration. Ecopsychology, 12(2), 71–82. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2019.0055. Scopus.

Ludy, C. R., & Perry, B. D. (2010). The Role of Healthy Relational Interactions in Buffering the Impact of Childhood Trauma. In Working with Children to Heal Interpersonal Trauma: The Power of Play. (p. 18). The Guilford Press

Macquarie Dictionary. (2021). Retrieved October 2023, https://www.macquariedictionary.com.au/

Marsh, P., Brennan, S., & Vandenberg, M. (2018). ‘It’s not therapy, it’s gardening’: Community gardens as sites of comprehensive primary healthcare. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 24(4), 337–342. https://doi.org/10.1071/PY17149

McLean, S., Coventon, L., Finch, C. F., & Salmon, P. M. (2022). Incident reporting in the outdoors: A systems-based analysis of injury, illness, and psychosocial incidents in led outdoor activities in Australia. Ergonomics, 0(0), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140139.2022.2041733

Mitten, D. (1994). Ethical considerations in adventure therapy: A feminist critique. Women & Therapy, 15(3–4), 55–84. https://doi.org/10.1300/J015v15n03_06

Mitten, D. (2020). Critical Perspectives on Outdoor Therapy Practices. In Outdoor Therapies (pp. 175–187). Routledge. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429352027-17/critical-perspectives-outdoor-therapy-practices-denise-mitten

Moriggi, A., Soini, K., Bock, B. B., & Roep, D. (2020). Caring in, for, and with nature: An integrative framework to understand green care practices. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(8). Scopus. https://doi.org/10.3390/SU12083361

Nabhan, G. P., Orlando, L., Smith Monti, L., & Aronson, J. (2020). Hands-On Ecological Restoration as a Nature-Based Health Intervention: Reciprocal Restoration for People and Ecosystems. Ecopsychology, 12(3). https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2020.0003

Neill, J. T. (2003). Reviewing and Benchmarking Adventure Therapy Outcomes: Applications of Meta-Analysis. Journal of Experiential Education, 25(3), 316–321. https://doi.org/10.1177/105382590302500305. Scopus.

Nicholls, V. E. (2008). Busy doing nothing: Researching the phenomenon of" quiet time" in a challenge-based wilderness therapy program. Doctor of, 132–132

PACFA. (2017). PACFA: Code of ethics. Psychotherapy and counselling federation of Australia. Retrieved October 2023, https://www.pacfa.org.au/common/Uploaded%20files/PCFA/Documents/Documents%20and%20Forms/PACFA-Code-of-Ethics-2017.pdf

Partridge, E. (1990). Origins: An etymological dictionary of modern English (Fourth ed.). Routledge

Pearce, L. M. (2018). Affective ecological restoration, bodies of emotional practice. International Review of Environmental History, 4(1), 167–189.

Peel, N., Maxwell, H., & McGrath, R. (2021). Leisure and health: Conjoined and contested concepts. Annals of Leisure Research, 24(3), 295–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2019.1682017. Scopus.

Perry, B. D., & Ablon, J. S. (2019). Viewing Collaborative Problem Solving Through a Neurodevelopmental Lens. 13

Peters, M., Godfrey, C., McInerney, P., Munn, Z., Trico, A., & Khalil, H. (2020). Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews. In E. Aromataris & Z. Munn (Eds.), JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-12

Plesa, P. (2019). A theoretical foundation for ecopsychology: Looking at ecofeminist epistemology. New Ideas in Psychology, 52, 18–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newideapsych.2018.10.002. Scopus.

Porges, S. (2011). The Polyvagal Theory (1st ed.). W. W. Norton & Company, Inc

Prehn, J. (2021). ‘“We’ve always done it. Country is our counselling office”’: Masculinity, nature-based therapy, and the strengths of Aboriginal men. Retrieved October 2023, http://ecite.utas.edu.au/143625

Prehn, J., & Ezzy, D. (2020). Decolonising the health and well-being of Aboriginal men in Australia. Journal of Sociology, 56(2), 151–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783319856618. Scopus.

Pretty, J., Rogerson, M., & Barton, J. (2017). Green mind theory: How brain-body-behaviour links into natural and social environments for healthy habits. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(7). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14070706

Pryor, A. (2006). Does Adventure Therapy Have Wings? Connecting with the Essence: 4th International Adventure Therapy (IATC4) Proceedings. 4th International Adventure Therapy, Rotorua, Aotearoa, New Zealand

Pryor, A. (2009). Wild adventures in wellbeing: Foundations, features and wellbeing impacts of Australian outdoor adventure interventions (OAI) [PhD Thesis, Deakin University]. Retrieved, October 2023, https://hdl.handle.net/10536/DRO/DU:30027427

Pryor, A., & Carpenter, C. (2002). South Pacific Forum for Wilderness Adventure Therapy: Shared Conversations. (Available from School of Education, Victoria University, PO Box 14428, MC Vic 8001, Australia.)

Pryor, A., Carpenter, C., & Townsend, M. (2005). Outdoor education and bush adventure therapy: A socio-ecological approach to health and wellbeing. Australian Journal of Outdoor Education, 9(1), 3–13.

Rakar-Szabo, N., Jane Steele, E., Smith, A., & Pryor, A. (2019). Regenerate evaluation: Executive summary. Retrieved October 2023, https://adventureworks.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Regen%20Eval_Exec%20Summ_FINAL_010319.pdf

Reese, R. F. (2016). EcoWellness & Guiding Principles for the Ethical Integration of Nature into Counseling. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 38(4), 345–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-016-9276-5. Scopus.

Reese, R. F. (2018). EcoWellness: Contextualizing Nature Connection in Traditional Clinical and Educational Settings to Foster Positive Childhood Outcomes. Ecopsychology, 10(4), 289–300. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2018.0031. Scopus.

Reynolds, V. (2013). Centering ethics in group supervision: Fostering cultures of critique & structuring safety. International Journal of Narrative Therapy & Community Work, 4, 1–13.

Rigolon, A., Browning, M., McAnirlin, O., & Yoon, H. V. (2021). Green Space and Health Equity: A Systematic Review on the Potential of Green Space to Reduce Health Disparities. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 18(5). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052563

Ritchie, S. D., Wabano, M. J., Russell, K., Enosse, L., & Young, N. L. (2014). Promoting resilience and wellbeing through an outdoor intervention designed for Aboriginal adolescents. Rural and Remote Health, 14, 2523. Scopus

Roberts, J. D., Ada, M. S. D., & Jette, S. L. (2021). NatureRx@UMD: A Review for Pursuing Green Space as a Health and Wellness Resource for the Body, Mind and Soul. Am J Health Promot, 35(1), 149–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890117120970334d. mdc.

Robinson, J. M., Jorgensen, A., Cameron, R., & Brindley, P. (2020). Let Nature Be Thy Medicine: A Socioecological Exploration of Green Prescribing in the UK. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 17(10). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103460

Rodríguez-Redondo, Y., Denche-Zamorano, A., Muñoz-Bermejo, L., Rojo-Ramos, J., Adsuar, J. C., Castillo-Paredes, A., Vega-Muñoz, A., & Barrios-Fernandez, S. (2023). Bibliometric Analysis of Nature-Based Therapy Research. Healthcare (Switzerland), 11(9). Scopus. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11091249

Russell, K. C., & Harper, N. J. (2006). Incident monitoring in outdoor behavioral healthcare programs: A four-year summary of restraint, runaway, injury and illness rates. Journal of Therapeutic Schools and Programs, 1(1), 70–90.

Sacco, K. K. (2021). Infusing Adventure Based Counseling Techniques Into Counselor Education. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health. Scopus. https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2020.1870598

Siegenthaler, A. L., & Boss, P. (1998). Commentary: A Feminist Perspective on The Issue of Neutrality In Therapy: Neutrality Can Be Hazardous To The Clients’ Health. Contemporary Family Therapy, 20(3), 333–340. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1022468913378

Spade, D. (2010). Be Professional. Harvard Journal of Law and Gender, 33(1), 71–84.

Stålhammar, S., & Thorén, H. (2019). Three perspectives on relational values of nature. Sustainability Science, 14(5), 1201–1212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-019-00718-4. Scopus.

Stea, T. H., Jong, M. C., Fegran, L., Sejersted, E., Jong, M., Wahlgren, S. L. H., & Fernee, C. R. (2022). Mapping the Concept, Content, and Outcome of Family-Based Outdoor Therapy for Children and Adolescents with Mental Health Problems: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(10). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19105825

Sveiby, K. E., & Skuthorpe, T. (2006). Treading lightly: The hidden wisdom of the world’s oldest people (Morris Miller Main DU 124. S64 S84 2006). Allen & Unwin

Swinson, T., Wenborn, J., & Sugarhood, P. (2019). Green walking groups: A mixed-methods review of the mental health outcomes for adults with mental health problems. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 83(3), 162–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022619888880

Taranrød, L. B., Pedersen, I., Kirkevold, Ø., & Eriksen, S. (2021). Being sheltered from a demanding everyday life: Experiences of the next of kin to people with dementia attending farm-based daycare. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 16(1), 1959497. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2021.1959497

Tujague, N. A., & Ryan, K. L. (2021). Ticking the box of ‘cultural safety’ is not enough: Why trauma-informed practice is critical to Indigenous healing. Rural and Remote Health, 21(4), 1–5.

van der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Penguin Books.

Walter, M. (Ed.). (2019). Social research methods (Fourth edition). Oxford University Press

Wells, F. C., & Warden, C. R. (2018). Medical Incidents and Evacuations on Wilderness Expeditions for the Northwest Outward Bound School. Wilderness Environ Med, 29(4), 479–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wem.2018.07.004

White, M. (2007). Maps of Narrative Practice (1st ed.). W. W. Norton & Company, Inc

Yessoufou, K., Sithole, M., & Elansary, H. O. (2020). Effects of urban green spaces on human perceived health improvements: Provision of green spaces is not enough but how people use them matters. PLoS ONE, 15(9), e0239314. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239314

Zhu, S.-H., Lu, Z.-D., Wan, H.-J., & Ye, C.-Y. (2017). Effect of horticultural therapy on metabolism indices in in-patients with chronic schizophrenia. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 31(6), 447–453.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Knowles, B., Marsh, P., Prehn, J. et al. Addressing ethical issues in outdoor health practice: a scoping review. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education 27, 7–35 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-024-00160-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-024-00160-w