Abstract

Martha Muchow, in collaboration with Heinz Werner, developed a questionnaire to collect data on magical thinking and practices in children and adolescents in Germany in the early 1900s. Three other studies (Watzlawik & Valsiner, 2012; Massoumi, 2019; Szarata, 2019) have used an English translation of this questionnaire to collect and analyse data on magical thinking and behaviour in the USA, Germany, India, Turkey, and South Korea. Using a cultural psychology and critical cross- “cultural” approach, this study combined and re-analysed both Massoumi in Karl-Franzens-Universitaet Graz, 2019 and Szarata in Freie Universitaet Berlin, 2019 pre-coded data (N = 488) on the magical practices from four countries: Germany, India, Turkey, and South Korea. A descriptive analysis and cross-tables (chi-square) for group comparisons were performed. The study aims to compare the similarities and differences of groups in different settings on how magical practice is applied (passively or actively), the internal and external motives and influencing factors behind magical thinking and practices, and the reactions to the outcomes of magical practice. The findings show that the participants’ country of origin played a role in who used magic; how and reasons for its application; its continued use and frequency of use in adulthood; reactions to their outcomes; and the motivating factors for magic application. Participants’ sex and the religious status only played a role in who used magic, reactions to their outcomes, and motives for their use. The current study adds support to the relevance of reanalysing data from historical periods in understanding how cultural phenomena move in time and space, and discusses directions for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Magical thinking and practices were for a long time considered to be a relic from the developmental history of mankind (Heine, 2000), “a remnant of childhood and an immature mind” (Rosengren & French, 2013, p. 42), and associated more with “primitive” or “uncivilized” societies (Zusne & Jones, 2014). The emergence of religious and social sciences as academic disciplines in the late nineteenth century placed the role of magic (and its rites, rituals, and beliefs) at a crossroad, where it was used to define religion (and differentiating it to magic) and mediate religion’s relation to science as a “worthy” human experience (Sørensen, 2008; Styers, 2004). This aided the exclusion of magic from the defining norms, and identities of modern Western societies. And although magical thinking and practices is nowadays considered universal and present in every society (Mayer, 2015; Rosengren & French, 2013), Otto (2019) found that their validity still comes into questioning. They are still believed to be anti-religious; are refuted and explained by modern science (e.g. the herbology aspects of witchcraft being explained in pharmacology); and even argued alongside historic stereotypical concepts of magic—heresy, superstition, idiocy, etc. (Otto, 2019). Valid or not, magic pervades all aspects of our lives as cognitive processes that are a part of our daily social lives and correspond to “culturally organised settings” (Lave, 1988, p. 1) that involve other actors (Lave, 1988). Recognising that magical thinking has been shown to decreases across childhood as it does across adulthood, where magical explanations of events become less socially appealing (Brashier & Multhaup, 2017), clinical psychologists and anthropologists continue to research the nature and roles of magical thinking and practices play in human beings’ experience of the world.

This study adds to the body of existing research on magical thinking and practices through a review and analysis of four clinical psychology studies conducted between the twentieth and twenty-first century on magical thinking. A brief overview of the studies is provided here for a contextual background to the study that will be presented in this article. Three of the studies used build on Heinz Werner and Martha Muchow’s (1928) study on magical personal customs of children and young adults in Germany, using a questionnaire they developed and Muchow published in the Journal for Educational Psychology. Werner and Muchow’s study coincided with the beginning of the World War II and was subsequently not completed (Watzlawik, 2013). Some 600 filled questionnaires were, however, found in Werner’s belongings at Clark University, when he was based following his escape from the Nazi regime until his death (refer to Watzlawik, 2013; Watzlawik & Valsiner, 2012). Werner’s and Muchow’s questionnaire and the preliminary work they did at Hamburg University are regarded as the first study for this article.

This article’s second study was one conducted by Watzlawik and Valsiner (2012) and published in The Oxford Handbook of Culture and Psychology. Their three-part study entailed a translation of the questionnaires (from German to English), application of the translated questionnaire to Clark University’s psychology students, and then a comparison of the responses from their sample with those from the German sample (Watzlawik & Valsiner, 2012). The third study in this article is a Clinical Psychology master’s thesis study by Massoumi (2019), who applied Watzlawik and Valsiner’s translated questionnaire to psychology students in Germany, India, Turkey, and South Korea and included the US sample (from Watzlawik & Valsiner’s, 2012 study) for a cross-country comparison on magical thinking. Massoumi’s analysis however only focused on responses to the first half of the questionnaire. The fourth study used in this article is Szarata (2019) bachelor’s thesis which used Massoumi’s data from the four countries (Germany, India, Turkey, and South Korea) and analysed the responses to the remaining half of the questionnaire for a country comparison on magical application practices and coping strategies adopted to failed magic.

The current study presented here takes a retrospective approach to these four research endeavours and reflects on the prevalence of magical thinking over time. It uses a statistical re-analysis of the data collected by Massoumi (2019) and Szarata (2019) from the four countries (Germany, India, Turkey, and South Korea) to describe the similarities and differences related to magical thinking and practices between the four countries, while also reflecting on the key findings from Watzlawik and Valsiner (2012) study. In doing so, this article presents for the first time, a country comparison of magical thinking and practices in children and young adults using Werner and Muchow’s questionnaire and offers a critical reflection for future research considerations. Furthermore, the current study adds support to the relevance of reanalysing data from historical periods in understanding how cultural phenomena move in time and space.

The following sections of this article will summarize literature on the relation between life’s uncertainties and magical thinking, classical views on magical thinking and practices, and present evidence from empirical studies on the role of magic in our lives. An exhaustive literature review is beyond the scope of this article and will not be provided. What is however offered is a supporting framework for understanding the concepts and ideas that are used in the study.

Magical Thinking and Uncertainty in Life

In his 1984 article, Individuality and Hubris in Mythology: The Struggle to be Human, Mitchell (1984) suggests that of all creatures in this world, human beings have the potential to live with freedom and choice. Yet the history of humans shows it is the world that set their limits, provided them harmony, and influenced their behaviour in such a way that they really have little more freedom and choice than other animals do (Mitchell, 1984). Over time, humans have accumulated the psychological and intellectual tools needed to overcome the challenge of life being determined by heredity, instincts, or environmental limitations and thereby “manifest their potential to choose and gain responsibility for their own destiny” (Mitchell, 1984, p. 400). In finding the power to subdue nature, the structure and harmony that the world provided is however lost and humans are left to encounter a new life state–uncertainty.

Uncertainty, the reality that the future is capricious, is therefore an inevitable fact that all societies must reckon with. Life for us humans has come to mean living “in a gray-scale space where uncertainty is rife” (Simpkin & Schwartzstein, 2016, p. 1713). For Watzlawik and Valsiner (2012), the uncertainty and unpredictability of life as the state is when “the causes for a certain and favoured outcome are unknown” (p. 784). Zusne and Jones (2014) add that “the realization that one does not know, or that one lacks certain information, equals the realization that this gap in information must be filled” (p. 13). Walker et al. (2003), however, argue that uncertainty is not simply a situation where knowledge is absent. For them, uncertainty can prevail in situations or contexts where information, even a lot, is available, and can be influenced (increased or decreased) by new or complex information.

In today’s context with the novel Covid-19 pandemic, the challenges related to information overload provide a good example of this view. Lockdown measures and increased isolation have seen many people resort to the Internet and social and electronic media for information and entertainment (Rathore & Farooq, 2020). While these online platforms offer a valuable forum for sharing valuable Covid-19 -elated data and promoting awareness of prevention strategies (e.g. Tangcharoensathien et al., 2020), there has also been sharing of “unauthenticated and sometimes dangerously incorrect information” (Rathore & Farooq, 2020, p. S163) with negative consequences increased Covid-19-related discrimination and racism, panic buying and stockpiling of essentials, and even the loss of lives (cp. World Health Organisation, 2020). The abundant supply of Covid-19 information during the Covid-19 pandemic has been termed as an “infodemic” defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as “an overabundance of information, some accurate and some not, that makes it hard for people to find trustworthy sources and reliable guidance when they need it” (WHO, 2020, “providing timely and accurate information”, para. 1).

So, what happens when people are confronted with uncertainty? Watzlawik and Valsiner (2012) propose that people would either do nothing or do anything to increase the likelihood of a favoured outcome. And when a cause-effect relationship “cannot be rationally explained by physical laws or culturally acceptable explanations” thereby creating uncertainty, magical thinking is thought to arise (Bocci & Gordon, 2007, p. 1823). Magical thinking therefore uses imagination to create a psychic reality that is based on an individual’s needs and one that the individual experiences as being more authentic than their external reality (Ogden, 2010). One could even describe this process as a type of cognitive-processing limitation where non-correlational reasoning is “utilized when objects and events conceptually (or semantically) affiliate or exclude one another in our minds” (Shweder et al., 1977, p. 637). While magical thinking is rooted in the experience of uncertainty, we can also appreciate that the meanings associated with these experiences is not only shaped by the sociocultural setting in which it occurs, but it may also differ among individuals in the same sociocultural setting. Two people from the same cultural context can thus attach different meanings to the same (uncertain) event, based on their unique personal experiences, personalities, education, traumas, social status, etc.

Classical View of Magic in Relation to Science and Religion

Early conceptions of magic were associated with descriptions of beliefs and practices in primitive societies (in distant “exotic” places), relics of an ancient past, and as “a precursor to scientific and systematic causal reasoning” (Rosengren & Hickling, 2000, p. 79) in human cognitive development (Rosengren & Hickling, 2000; Sørensen, 2007). Modern scholars comparing the modern scientific age with earlier times where magic prevailed often categorised science as knowledge that was backed by research and regarded “natural phenomena as the product of impersonal forces” (Brooke, 1991, p.17), while magic and religion were categorised as dogmatic knowledge that had no empirical support and involved supernatural agents and forces (Brooke, 1991; Versnel, 1991). This comparison appears to place science, on the one hand, in an opposite position from religion and magic, and on the other hand draws similarities between religion and magic in that they both “refer to supernatural forces and powers, a reality different from normal reality” (Versnel, 1991, p. 178). Literature however shows that religion has been elevated slightly in position on this continuum, as we will see in the subsequent paragraphs.

The reformation of the sixteenth century saw the nature and role of magic in Western societies remarkably change because of the transformations in political and economic structures along with the “concomitant shifts in the demarcation and social position of religion and science” (Styers, 2004, p. 27). Science, in predominantly Christian Western societies, was promoted as a new way of thinking about and relating to the universe and subsequently considered as “modern thought”, while magic was relegated to primitive thinking and fantasies of an ancient past (Bailey, 2006; Meyer & Mirecki, 1995; Styers, 2004; Sørensen, 2007; Subbotsky, 2010). Religious reform, specifically the period of Protestant Reformation, also saw a distinction made between religion and magic, where (certain) elements of religion were considered essential matters of private intellect and relegating others to superstition and other magical practices of less civilised societies (Bailey, 2006; Styers, 2004).

Moro (2017) explained that social theorists such as Emile Durkheim, Max Weber, and Marcel Mauss also supported the distinction between religion and magic, arguing that they were different ways humans classified and understood the world according to the different levels of social organisations and institutional development of a particular society. Religion became classified by some as a system of institutionalised magical beliefs, while practices such as witchcraft, astrology, palm reading, and even everyday superstitions as noninstitutionalised magical beliefs (Subbotsky, 2010). Versnel (1991) for example elaborates how the distinction between religion and magic, which continues to be applied today, is argued around the following distinguishing characteristics:

-

1.

Intention or goal—the primary goal of magic is to achieve individual goals while that of religion focuses on long-term societal goals and concerns.

-

2.

Attitude—magic predominantly entails manipulative acts carried out and influenced by an individual with the secret knowledge of doing so, whereas religion entails an attitude of submission and supplication towards powers that are outside an individual’s sphere of influence.

-

3.

Action—to guarantee its success, magic focuses on the rules and instructions and often requires some level of professional experience. Religion, however, focuses on intended future outcomes which are not dependent on professional specialist (though their skills may be important facilitators) but on the free favour of sovereign gods.

-

4.

Social or moral evaluation—the belief that magic is individualistic makes it often perceived as an anti-social activity. Religion is on the other hand, perceived as being a positive social cohesive act.

Let us note that the above understanding of the difference between religion and magic is very much a Western one that largely considers major world religions and excludes those found in local settings, which subsequently excludes an understanding of the culture in which it is embedded, its founders and foundations of the religious system, as well as cultural texts or artefacts that may provide additional information about that religious system (Hopfe & Woodward, 2009). Although magical thinking is now accepted as a universal phenomenon, how it is understood and promoted continues to carry on a biased Westernised understanding of magic and its cultural roles. That is, magical thinking and practices are still framed in terms of “an evolutionary sequence from magic-to-religion-to-science” (Nemeroff & Rozin, 2002, p. 2) and magic as being “bad religion, bad science, bad medicine” (Meyer & Mirecki, 1995, p. 2). Reinforcing the belief that magic and magical practices are contradictory to modern everyday experience and to the basic laws of nature (Subbotsky, 2011) fails to incorporate human experiences and events that science has not offered explanations for. Subsequently, this has clinical implications, as it drastically limits a wholistic understanding of types of human thought processes and the roles they play in an individual’s life. Alternative views of magic that are not framed within the tripartite distinction between religion, magic, and science and their roles in everyday human experience therefore need to be considered.

The Role of Magical Thinking in Our Lives

The psychological functionism’s view of the role of magic and its role in society explains magical thinking as the false beliefs in causal relations without empirical evidence that is typically found in children (believed to decrease with age) and the mentally ill (Moro, 2017). Piaget, for example, viewed magical thinking as a ubiquitous aspect of a child’s cognitive development (cp. Rosengren & French, 2013). For him, magical thinking was a typical type of error in everyday cause-effect relations that a child makes simply because they lack a particular knowledge about an event or situation. He argued that magical thinking in children would be gradually replaced with more logical and scientific thinking as their cognitive structures become more differentiated and complex as the child grows and their experience with and knowledge of the world changes (Miller, 2016).

Vygotsky on the other hand took a sociocultural approach that incorporated the role of culture in human development. He argued that culture, with its shared tools, symbols, practices, and histories, shaped and defined the knowledge and skills a child developed and needed to function in a particular cultural setting, which in turn explained the variability of children’s development around the world (Miller, 2016). Some contemporary scholars have also moved away from explaining cognitive development in terms of the development of scientific rationality, and incorporate sociocultural elements in their approach, including religious practices, societal values, and even local ideologies about events (Rosengren et al., 2000). For example, Nemeroff and Rozin empirical studies (e.g. 1989, 1994, 2000; see also Rozin et al, 1986) on sympathetic magical thinking (in the areas of disgust and fear of contagion) provided evidence to the existence of magical thinking in modern industrial societies and their purposes. They observed that their study subjects avoided disgusting replicas of their favourite food (e.g. chocolate shaped as dog faeces) adding support for the law of similarity, where the image or appearance of an object is perceived to be real and even share deeper properties with object it resembles. Where acceptable foods were in contact with disgusting objects (e.g. a sterilized cockroach in fruit juice), the food was rendered disgusting, providing evidence for the law of contagion, where elements of an undesirable object are believed to be transfer (and contaminate) to another object when they make physical contact. With their findings, Nemeroff and Rozin (1994) concluded that magical thinking was an integral part and type of human thinking that appeared to present itself only in certain conditions and for specific purposes. They saw that magical thinking could influence “individual economic decisions (e.g. holding on to an old, malfunctioning car because of one’s history with it), health decisions (e.g. avoiding food because it looks like something offensive, or because it is associated with an undesirable name; or being reluctant to receive blood from a donor of another race, …; or practicing homeopathic medicine), and tastes in things like clothing, food, or music” (Rozin et al., 1986, p. 711).

We could of course argue that the above findings also support arguments that magical thinking is cognitive errors where resemblance is used as a predictor for the likelihood of co-occurrence (Shweder et al., 1977). Regardless, it is quite normal for people to try and “understand, explain, and arrive at generalizations about the empirical relationships among objects and events in their experience … regardless of the presence or absence of explicit, self-conscious scientific canons of objectivity and verification in their society” (Shweder et al., 1977, p. 647). Magical thinking therefore allows us some sense of control in times of uncertainty and offers several causal pathways to account for human experiences and events where there might not be other explanations (Moro, 2017; Moscovici, 2014; Nemeroff & Rozin, 2000). The tendency to perceive an object as having an “essence” that determines its (positive or negative) characteristics (i.e. the concept of psychological essentialism) has been linked to beliefs that these characteristics could be transmitted when an individual physically touches that object (Rosengren & French, 2013). For example, the thinking that “grandmother’s ring was a part of her in a meaningful sense, so that wearing it constitutes a connection with her” is thought to further the experience of connections with one’s internal and external world (Nemeroff & Rozin, 2000, p. 26). The inclination to essentialise objects therefore invites clinicians to analyse the history of cherished objects with a view to understanding the personal meanings associated with magical thinking and behaviour.

Gmelch (1971) observed that American baseball players applied specific rituals (i.e. an action or behaviour intended to produce a desired outcome, e.g. listening to a particular song before playing a game) to enhance performance, reduce chance, and subsequently secure game success. Although these rituals have no empirical connection to the desired outcome, baseball players tended to associate their success, and its associated positive affective rewards, with a prior behaviour rather than their actual skills, as it provided them a sense of control over desired outcomes through their performance. While this may be considered an “illusion” of control, its adaptive function cannot be ignored. Assuming more control over your circumstances tends to predict positive health outcomes, while assuming less control can lead to poor health outcomes and poor overall performance in one’s life (Nemeroff & Rozin, 2000). Nemeroff and Rozin (2000) draw our attention to an existing large body of clinical studies showing how “learned helplessness is linked to depression, stress, physical symptoms, and poorer overall performance in life” (p. 27).

Subbotsky (2010) also suggests that in considering alternative forms of causality, magical thinking fosters creativity as is presently found in our literature and the visual (e.g. photography, sculptures, paintings) and performing (e.g. plays, films, dance) arts. In conclusion, these few examples add support to magical thinking being common across sociocultural settings (including modern societies and among their “educated” members) and allows us to appreciate the adaptive uses of magical thinking.

Study Methodology

Literature shows that while magical thinking and behaviour are observable in all societies around the world, how they are manifested in social life is, however, context and culture specific. Understanding the meaning-making processes involved in magical thinking and behaviour and the meanings they arrive at may thus shed light on culture’s role in the use of magic and its associated features.

For this purpose, this study combines a cultural psychology and critical cross-cultural approach to investigate four studies on magical thinking and behaviours that were conducted between the twentieth and twenty-first century. A statistical re-analysis of pre-coded data from two studies (from the late 2000s) will be conducted and discussed alongside reflections of findings and observations from two other studies (from the early 1900s and early 2000s) to draw attention to the prevalence of magical thinking and behaviour across space and time. The four studies use the same data-collection tool, a questionnaire that was developed by Muchow (1928), together with Werner, to investigate magical thinking and behaviour. The journey of this questionnaire and subsequent studies that used it will be described in the section that follows.

The following overarching question guided the statistical re-analysis of the two studies with data from four countries, namely Germany, India, South Korea, and Turkey: Do the different countries exhibit commonalities or differences in the use of magical thinking? If so, what are the specific nuances regarding magical thinking and behaviour? The following sub-questions helped to answer these questions:

-

Is magical thinking and behaviour applied actively, passively, or both?

-

For what purpose is magical thinking used?

-

Did the use of magical thinking continue from childhood/adolescence into adulthood?

-

How did the participant react or respond when the desired outcome was not achieved?

-

What motivates one to use of magical thinking or behaviour?

The above approach was selected for two main reasons. Firstly, it presents a cross-country comparison of magical thinking and practices in Germany, India, South Korea, and Turkey by combining and re-analysing two studies that each assessed responses to half of the same questionnaire. Secondly, in adding reflections of findings from other previous studies that used the same questionnaire and using a critical cross-cultural lens, the current study can highlight tendencies of magical thinking and practices spanning a period of 92 years and put forth recommendations for future research in magical thinking and practices.

Journey of the Questionnaire and Subsequent Research Endeavours

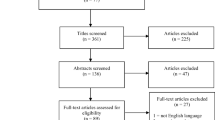

Figure 1 illustrates the journey of Muchow’s questionnaire and subsequent research endeavours, whose details will be outlined in this section.

Together with Werner, Muchow (1928) developed a questionnaire to facilitate their investigation on magical personal customs of children and young adults, which was published in the Journal for Educational Psychology in Germany (Muchow, 1928). Earlier interviews they had conducted with adolescents and adults at Hamburg University’s Psychological Laboratory already showed the presence of magical practices in these two population groups (Watzlawik & Valsiner, 2012). The rise of the Nazi regime coinciding with the beginning of the World War II halted the completion of Werner and Muchow’s study. During Werner’s escape from Germany, he carried with him some pre-filled questionnaires, which made their way to Clark University in Worcester, USA, where he resided until his death in 1964 (Watzlawik & Valsiner, 2012).

In 2009, while working at Clark University, USA, Roger Bibace (1926–2020) and Watzlawik found some 600 pre-filled questionnaires among Werner’s things at the Heinz Werner Library at Clark University. Watzlawik proceeded to translate the questionnaire into English and added a question to the original questionnaire, making it into 11 open-ended questions with 12 demographic questions (Massoumi, 2019). Together with Jaan Valsiner, she then used the translated questionnaire to investigate how magical thinking was culturally constructed in America and Germany and whether the underlying use of magical behaviour had changed over the different time periods (Watzlawik & Valsiner, 2012). The questionnaire was given to undergraduate students of the Psychology Department at Clark University, results of which were published in the Oxford Handbook of Culture and Psychology in 2010 under the title “The Making of Magic: Cultural Constructions and the Mundane Supernatural”. Watzlawik later handed over the completed questionnaires to the University of Hamburg, where they now remain at the Martha-Muchow-Library (Universität Hamburg, 2010). A synopsis of the translated questionnaire is provided in Table 1.

For her master’s thesis, Massoumi (2019) used the English translated questionnaire to analyse the cultural differences in magical practices and their meanings from the USA (N = 54), Germany (N = 93), India (N = 99), South Korea (N = 136), and Turkey (N = 160). While she used Watzlawik and Valsiner (2012) US data, Massoumi collected fresh data from Germany, India, Turkey, and South Korea. The data was collected from university students, most of whom were psychology students. Ethical consent was obtained from the respective universities’ ethical boards as well as the study participants prior to the investigation. Translation of the English questionnaire into the local language was required for the research groups in Turkey, South Korea, and Germany. Results from these samples were then translated back into English for the data analysis.

The data used by Massoumi was gathered between 2009 and 2018. She used the responses from the first five of the ten questions from the translated questionnaire for her study and applied a two-step approach to analyse the responses to the five questions: a qualitative content analysis to categorise and code the responses to the open-ended questions, followed by a variance analysis of the data on SPSS for cross-country comparison. In the same year, Szarata (2019) used Massoumi’s data set and analysed the differences in the use of magical behaviour and reactions to its ineffectiveness, with a focus on the responses to the last and remaining five questions of the questionnaire. She excluded the responses from the US (N = 54) sample and used a similar two-step approach to Massoumi.

The current study combined and re-analysed both Massoumi (2019) and Szarata (2019) pre-coded data and used a descriptive analysis and cross-tables (chi-square) for group comparisons in favour of a variance analysis, which was considered better suited for the existing data. The focus of analysis also changed: While Massoumi (2019) and Szarata (2019) analysis focused on a country-difference perspective with respect to magical thinking and behaviour, this study additionally explores the similarities and unique nuances among four countries: Germany, India, Turkey, and South Korea. Since Szarata (2019) omitted responses from the USA in her analysis, for comparability, this study also omits this country’s responses in this re-analysis. Reflections from Watzlawik and Valsiner (2012) study, which comprise of a US and earlier German sample, are incorporated in this study. The findings presented here are therefore a first ever overview of different country responses to Muchow’s translated questionnaire in its entirety. Additionally, while Muchow’s questionnaire did not include any demographic questions, the English translated questionnaire that was used in Massoumi and Szarata’s studies did, thereby allowing consideration of these parameters in the current study.

Four hundred eighty-eight participants’ responses, distributed as follows, make up this study’s sample set: Germany (N = 93), India (N = 99), Turkey (N = 160), and South Korea (N = 136). The sample description is shown in Table 2.

Results

Is Magical Thinking and Behaviour Applied Actively, Passively, or Both?

From 488 respondents, a frequency analysis showed that 259 (53%) used oracles (either actively or passivelyFootnote 1) and 141 (29%) did not, in childhood/adolescence. In assessing the use of oracles according to participants’ sex and religious status, similar findings were registered (see Fig. 2a, b). For example, more male (n = 93, 65%) and female (n = 252, 74%) participants reported using oracles either passively or actively compared to those who did not. Similarly, more participants used oracles than those who did not, irrespective of their religious status or affiliations. Results also showed that twice as many females used oracles than those who did not, while an almost equal number of men used oracles as much as those who did not.

A statistical analysis showed a significant association between country of origin and active use of oracles, X2 (3, N = 488) = 19.47, p < .001. Turkey and South Korea were disproportionally associated with active use of oracles (see Table 3a). For passive use of oracles, significant associations between country of origin and passive use of oracles, X2 (3, N = 488) = 55.74, p < .001, and between sex and passive use of oracles, X2 (1, N = 488) = 14.65, p < .001. Germany, India, and females were found to be disproportionately associated with passive use of oracles.

For What Purpose Is Magical Thinking Used?

The reasons behind the use of magical practices during childhood and adolescence were analysed using a qualitative content analysis of the responses toFootnote 2Questions 1a, 1b, and 4 (Massoumi, 2019). Table 3 displays the identified categories assigned to participants’ responses to their application of active and passive oracles. A frequency analysis from 488 responses on the reasons behind using oracles revealed that for active oracles, the top three drivers for their use were “test of physical fitness” (n = 46, 9%) followed by “other reason” (n = 41, 8%), and lastly to “adjust walking pace” (n = 30, 6%). For passive oracles, the top three factors behind their use were “counting objects” (n = 89, 18%), then “religious reasons” (n = 59, 12%), and to “assign meaning to random events” (n = 49, 10%). When considering the sex and religious status of the participant, the same order was found.

A chi-square test of independence showed a significant association between country of origin and some of the identified categories for active and passive use of oracles. With active oracles, there was a significant relationship between country of origin and testing one’s physical fitness, X2 (3, N = 488) = 29.54, p < .001; country of origin and adjusting walking pace, X2 (3, N = 488) = 25.33, p < .001; and country of origin and consuming a specific food/drink, X2 (3, N = 488) = 18.93, p < .001. Turkey was disproportionately associated with applying active oracles to test their physical fitness and to adjust their walking pace, while India was disproportionately associated with applying active oracles to consume specific foods/drinks.

With passive oracles, there was a significant association between country of origin and counting objects, X2 (3, N = 488) = 64.87, p < .001; country of origin and taking part in social customs, X2 (3, N = 488) = 10.76, p = .013; country of origin and using specific items or games, X2 (3, N = 488) = 33.66, p < .001; and country of origin and using them for religious reasons, X2 (3, N = 488) = 88.27, p < .001. Specifically, Germany was disproportionately associated with applying passive oracles to count objects, taking part in social customs, and using specific items or games to make decisions, while India was disproportionately associated with using passive oracles to take part in social customs and for religious reasons. No statistically significant association was found between sex and any of the identified categories, nor between religious status and any of the identified categories.

Did the Use of Magical Thinking Continue from Childhood/Adolescence into Adulthood?

When asked whether participants continue to use rites, rituals, and/or oracles (referred to as “magical practices” or “practice of magic” in the subsequent text), a frequency analysis showed that 260 (53%) participants continued to use them, compared to 228 (47%) who no longer use them.

A frequency analysis of the current practice of magic against the sex, religious status, and country of origin of the participant seemed to show some differences (see Fig. 3a–c). For example, more female than male participants reported practicing magic at the time of the survey. Under the religious status category, more religious than non-religious participants reported practicing magic at the time of the survey. Among the four countries, India had the highest portion of participants who reported continued practice of magic at the time of the survey, followed by those from Germany and then South Korea. Participants from South Korea tended not to continue practicing magic while an equal number of participants from Turkey continued to practice magic, as did those that do not.

In reviewing whether the above differences were statistically significant, a chi-squared test found a significant association between country of origin and continued practice of magic, X2 (3, N = 488) = 16.66, p < .001. Specifically, India was disproportionately associated with continued practice of magic at the time of the survey. No significant association was found between sex and continued practice of magic, X2 (1, N = 486) = 2.20, p = .138, or between religious status and continued practice of magic, X2 (1, N = 486) = 2.20, p = .138.

Participants were also asked about the frequency of magical practice—often, rarely, sometimes, for important decisions, or daily. From 206 participants’ responses, a frequency analysis revealed that a majority applied them “rarely” (n = 58, 28%), followed by those who applied them “daily” (n = 52, 25%), and then those who applied them “sometimes” (n = 43, 21%), and magical practice was least applied “often” (n = 13, 6%).

When analysing the frequency of use of magical practice against participants’ sex, religious status, and country, some differences in patterns of use emerged. Figure 4a shows that most male participants reported practicing magic “daily”, followed by “sometimes”, and then “rarely”. Female participants, on the other hand, presented a similar pattern to the whole sample. They reported practicing magic “rarely” the most, followed by “daily”, and “sometimes”. Non-religious participants practiced magic mostly “rarely” and “sometimes” equally, followed closely by when making “important decisions” and then “daily”. Religious participants presented with a similar trend to that of the whole sample. A majority used them “rarely”, followed by “daily”, and then equally “sometimes” and when making “important decisions” (refer to Figs. 4a, b). A chi-square test of dependence however determined there were no significant associations between frequency of use of magical practices and sex, X2 (4, N = 204) = 1.36, p = .852, and between frequency of use of magical practices and religious status, X2 (4, N = 204) = 5.04, p = .284.

An analysis of the patterns in frequency of use across the countries showed that just under half of the sample provided insights into their patterns of magic practices. Some differences in the frequency of use between the countries appeared, as shown in Fig. 4c.

Participants from India and Turkey mainly practiced magic “rarely”, while those from Germany mainly practiced magic “sometimes”, and those from South Korea mainly practiced magic “daily”. Other than German participants who reported practicing magic “daily” the least, all other participants reported practicing magic “often” the least. The patterns of how the responses on the frequency of use of magic practice were distributed within each country were interesting. Participants from India were distributed nearly equally between the different five frequencies of use options provided, while the distribution for German participants tended to be around one preferred frequency of use (sometimes). Both Turkey and South Korea appear to show two main preferences for frequency of use. Respondents from Turkey used oracles mainly “rarely” and “daily”, while those from South Korea practiced magic mainly when making “important decisions” and “daily”.

A chi-square test of independence showed that the relation between country of origin and frequency of use of magical practices was significant, X2 (12, N = 206) = 82.65, p < .001. India was disproportionately associated with practicing magic often; Turkey was disproportionately associated with practicing magic both rarely and daily; Germany was disproportionately associated with practicing magic sometimes; South Korea was disproportionately associated with practicing magic for important decisions and daily; and India was disproportionately associated with practicing magic daily.

How Did the Participants React or Respond When the Desired Outcome Was Not Achieved?

Responses to the question on how participants reacted to unsuccessful outcomes of the rituals they applied (see question 9 in see Table 1) were also analysed through a qualitative content analysis. Seven categories were identified (see Table 4).

A frequency analysis of 251 responses found that only three participants (1%) reported that they always had success with their rituals, also the category with the least recordings. A majority, however, were indifferent (N = 104, 41%), followed by those who experienced negative emotions (N = 53, 21%), and in third place those who simply repeated the magical behaviour (N = 38, 15%).

When reviewing the role of sex and religious status, a similar pattern in the order of reported outcomes was observed. When country of origin was added to the analysis, interesting patterns of differences between the countries could be seen (see Table 5).

From Table 5, we see that participants from Germany, Turkey, and South Korea recorded being indifferent to their unsuccessful rituals attempts as the most common outcome. Participants from India, on the other hand, reported experiences of negative emotions as the most common outcome. The only country that recorded experiences of physical discomfort from unsuccessful ritual applications was Turkey (N = 2, 2%), albeit a small number. A closer look revealed that these two participants also identified as being female and religious. Two participants from India and one from Germany reported being successful in their rituals. These participants also identify themselves as being female and religious.

A chi-test square test of independence was used to examine the relationship between each of the variables of country of origin, sex, and religious status, and reactions to unsuccessful magic outcomes. A significant relation between country of origin and the experience of frustration (unspecified) was found, X2 (3, N = 251) = 20.46, p < .001. Specifically, South Korea was disproportionally associated with experiencing of frustration upon unsuccessful magic. There was also a significant association between sex and the experience of frustration, X2 (1, N = 250) = 10.80, p = .001, where males were disproportionally associated with experiences of frustration upon unsuccessful magic practices. The relationship between religious status and cessation of magical practice was also found to be significant, X2 (1, N = 251) = 6.99, p = .008, where religious people were disproportionately associated with ceasing magical behaviour upon unsuccessful magic outcomes.

What Motivates One to Use Magical Thinking?

Here, the analysis examined the importance of magical practices and the influencing factors (internal and external) behind participants’ use of these practices. When asked how important the rituals were or are to the participants, a frequency analysis showed that from 349 respondents, more than half of them (N = 218, 63%) stated they were “somewhat important”, followed by a quarter (N = 70, 20%) who noted they were “important”, and then just under a quarter reported noted they were “not important” (N = 61, 18%). When analysing the patterns of the perceived importance of the rituals against sex, religious status, and country of origin, similar patterns of responses were generally observed. Differences were specifically observed among male participants, participants who were religious, and participants from South Korea, where these groups all placed “not important” in second position and “important” in the last position (see Fig. 5a–c).

The relationship between country of origin and the importance of magical practices was found to be statistically significant, X2 (6, N = 349) = 33.21, p < .001. Germany and Turkey were disproportionately associated with perceiving rituals as somewhat important; South Korea was disproportionately associated with perceiving rituals as not important; and India was disproportionately associated with perceiving rituals as both important and not important. No significant association was found between sex and importance of magical practices, X2 (2, N = 348) = 3.74, p = .154, nor between religious status and importance of magical practices, X2 (2, N = 346) = 4.59, p = .101.

The analysis of responses to Question 4 on the internal and external influencing factors behind magical practices was done using a qualitative content analysis. The identified categories are reflected in Table 6.

A frequency analysis on the external motivating factors for magical practices revealed the top influencing factor being the participants “influence from friends” (n = 58, 50%), that is, persons unrelated to the participant, followed by “influence from family” (n = 49, 43%), and then “influence from environmental cues” (n = 23, 20%) including practices observed in movies, books, or those commonly observed in a particular society or setting. While non-religious participants show the same order of external motivating factors as that from the frequency analysis, the religious participants deviate slightly from that order. That is, family influence (n = 38, 51%) is the highest reported motivating factor, followed by friends’ influence (n = 32, 43%), and lastly environmental influences (n = 16, 22%). It was observed that participants from Germany and South Korea also adopted the same order of external motivating factors as that from the frequency analysis. Interestingly, participants from South Korea reported influence from their friends for their magic practice three times as much as their family (n = 8, 67% vs n = 2, 17%), while those from Germany were influenced nearly half as much by their friends as they were by their family (n = 18, 72% vs n = 10, 40%).

Participants from India (n = 30, 60%) reported to be influenced mostly by family, almost twice as much as by friends. Although participants from Turkey also revealed that friends influenced them the most to practice magic, just as those from Germany and South Korea, they instead stated environmental cues as being the second most external influencing factor for practicing magic, while German and South Korean participants had this factor in third position after influence from family (refer to Fig. 6a–c).

A statistical analysis on the role of sex, religious status, and country of origin only found significant associations between family influence and country of origin, X2 (3, N = 115) = 13.11, p = .004, and between influence from friends and unrelated persons and country of origin, X2 (3, N = 115) = 13.22, p = .004. Specifically, India was disproportionately associated with influence from family for their magical practices, while Germany, Turkey, and South Korea were disproportionately associated with influence from unrelated persons for their magical practices.

On the internal motives behind magical practices, a frequency analysis revealed that the top three categories (out of 7 coded categories) were “to regulate emotions”, that is, the elimination of negative feelings or events (n = 41, 29%); “for fun or entertainment purposes” (n = 36, 25%); and “to secure a successful outcome” (n = 26, 18%). Watzlawik and Valsiner (2012) also showed that participants from both samples (the USA and Germany) reported that fear and the subsequent anxiety it caused were a common trigger for magical practice, a result that is similar to this study’s finding of the most common internal motive for magical practice (i.e. to regulate emotions). When considering sex, religious status, and country of origin, only the sex category presented the same order of internal motives as that from the frequency analysis above. A statistical analysis, however, only found a significant association between the use of magical practice to eliminate boredom and country of origin, X2 (3, N = 143) = 7.83, p = .05, where Germany and Turkey were disproportionately associated with being intrinsically motivated by boredom to perform magic.

When looking at the participants’ sense of responsibility for others or their concern for others as potential internal motivating factors for magical practices, a frequency analysis seemed to suggest that these were not considered as key driving factors for magical practice. From 268 responses, only 70 participants (26%) confirmed that they performed rituals because they felt responsible for others’ well-being and only 42 (16%) reported that they performed rituals out of concern for others’ well-being. A similar pattern was observed when considering sex, religious status, and country of origin (see Fig. 7a–c).

A significant relationship was found between religious status and a sense of responsibility for others (X2 (1, N = 268) = 4.54, p = .033) and between country of origin and a sense of responsibility for others (X2 (3, N = 268) = 15.34, p = .002). India, South Korea, and non-religious persons were disproportionally associated with performing rituals out of a sense of responsibility for others. An analysis on the role of sex, religious status, and country of origin on driving concern for other’s well-being revealed a significant association between country of origin and concern for others’ well-being, X2 (3, N = 268) = 19.88, p < .001. Non-religious people were disproportionately associated with applying magic out of concern for others’ well-being. Sex and religious status showed no significant association with concern for others’ well-being.

Discussion

This study sought to analyse whether people from different countries exhibit commonalities and/or differences in their use of magical thinking and behaviour. Specifically, how they are applied, the internal and external motives surrounding them, and the experienced reactions to their performance. The observations presented here support several findings from existing studies on magical thinking, beliefs, and practices. We can appreciate the ubiquitous nature of magical practices in modern society, their presence across the human lifespan, and their relevance in human life. This study applied a cross-cultural comparison in the way magic, and while differences appeared between the countries regarding the motives behind magical practices and the frequency of their use, the religious status and sex of a participant appeared to play only minor roles in the practice of magic.

The role of sex in magical practice was only relevant in relation to the use of oracles passively and the experience of frustration from unsuccessful outcomes of magical application. This finding is interesting for a few reasons. Given that most participants rated magical practices as “somewhat important”, then we could expect experiences of frustration, disappointment, anger, or other negative emotional affect when the application of magic cannot achieve success. Concurrently, if we use the argument that magical thinking is “illogical,” or “unreasonable,” or “irrational,” then any expectation that success is likely or even guaranteed would be unrealistic, and perhaps even eliminate any negative effects that would be associated with failed magical practices. The study, however, demonstrated that even known/realised unrealistic expectations can still lead to frustration, showing that magical practice may offer some sort of benefit to an individual, which they attach importance to. Watzlawik and Valsiner’s (2012) study found that in both the US and German sample, participants’ reactions to failed magical practices appeared to indicate a correlation between the importance or personal value attached to the desired outcome of a ritual and the reactions to failed rituals. For example, in their study, they regarded those participants that reported to “shrug” it off when the desired outcome was not achieved, as attaching low importance to that ritual, while those who blamed themselves when the desired outcome was not achieved, they regarded them as attaching high importance to that rituals. Withal, the actual role of a participant’s sex is unclear and would need further investigation into the meanings and associations individuals have for magical thinking and behaviour.

Religious practice only played a role in relation to the cessation of magical practice upon their unsuccessful outcomes and its association with a sense of responsibility for others as an internal motivating factor for magical application. Perhaps religious persons would cease magical practice upon unsuccessful outcomes if it were perceived that the wishes and expectations not being aligned with those of a higher power. It may, however, be surprising that religious persons felt less responsible for the well-being of others, if one considers the maxims of charity or benevolence of many religions. However, it could also be argued that this responsibility is placed with a higher power (e.g. a justly acting divine being) and that an individual can help others but cannot directly influence their well-being. In both cases, more in-depth interviews could shed light on the attributions of meaning here.

Although only three out of 488 participants stated that their magical practices were always successful, individuals continued applying magic mostly passively, and just like findings from other studies, magical practice in this sample also decreases in the participants’ lifespans. The continuation of magical practice from childhood into adulthood was also found by Watzlawik and Valsiner (2012), where 83% of US (n = 25) and 85% of German (n = 28) participants reported they continued practicing magic in adulthood. Interestingly, while they found that the function of performed rituals is relatively stable over the participants’ life course, they noted that their content varied. For example, from the German sample, a participant reported counting a particular type of horse that was a common and important mode of transportation in those times. Their US sample however had no mention of counting horses, which they deduced was because horses were replaced by cars as a mode of transportation at the time the study was conducted. Another related observation they made was that participants applied magical practices for specific purposes (e.g. to alleviate boredom or for self-motivation) and only for a specific time. Similarly, some participants reported the emergence of magical practices along with certain events or triggered by unpleasant or traumatic experiences. Of the responses to the emergence of magical practices (n = 57), 11% attributed the emergence of magical practices to the parallel occurrence of events and 12% attributed them to unpleasant or traumatic experiences.

We can appreciate that self-soothing or self-regulation is a crucial part of human functioning that entails a dynamic process through which experience gathered from environmental cues works to steer an individual’s actions towards a desired goal in a variety of settings (Blair & Ursache, 2011; Inzlicht et al., 2021). Following this and this study’s findings that family, friends, a sense of responsibility, and concern for others were significant motivating factors for magical practice in adulthood, one can see how magical thinking and behaviour relies on an exchange between one’s internal and external world—while being set in a specific cultural context that influences its uses including rules—with the goal to achieve some sort of harmony in an individual’s internal world. Furthermore, it counters the perception that individualistic practices and values are increasing globally. Similarly, these findings are also aligned with those of Watzlawik and Valsiner (2012) that magical practices are: commonly a private affair not shared with others; depend on the circumstances that trigger them; and reactions to their outcomes depend on the value attached to the desired outcome of the magical practice being performed. This reinforces other arguments that magical thinking can, and does, co-exist alongside what is considered rational thought, and in harmony at that. Consequently, the legitimacy of the arguments differentiating rational from magical thinking begs a closer look. In-depth studies on the relationship between the environmental cues, one’s internal state, and the meanings produced would therefore provide valuable insights into not only the culturally specific experiences surrounding magical thinking and behaviour but also the unique individual nuances that accompany them.

Nonetheless, the findings of this study must be seen considering some limitations. Four major limitations could be addressed in future research. First, the questionnaire included suggestive or leading questions as well as questions with over one interpretation. A revision and testing of the questionnaire are needed to better assess the relevance of magical practices in society today. Second, the data used for this re-analysis is not an accurate representation of the populations being studied. The sample comprised students, a majority of whom were undergraduate psychology students and identified themselves as female. Would responses from students of philosophy or religious studies have differed? Would one’s perceived agency and control in everyday life play a role in magical practices? These questions remain open and therefore the generalizability of this study is limited. Future studies should consider a sampling frame and recruitment procedures in their study scope that would represent an unbiased reflection of the population under study.

Third, there was the lack of available and reliable data, largely emanating from unanswered questions/missing data. Retrospectively, this likely originates from the design flaws of the questionnaire. Subsequently, it was challenging to find meaningful relationships and trends in the re-analysis. In-depth interviews exploring the unique meanings people assign to magic and magical practices, how they define different concepts associated with their use (e.g. frequency of use and level of importance), in which social contexts they are and/or not used, and the expected and/or realised outcomes, would provide a deeper understanding of the processes involved in magical thinking and behaviour.

Fourth, the translation of the original questionnaire and some of the responses could contribute to the different understandings being “lost in translation” from both the study participant’s and the study evaluators’ perspectives. Different cultural contexts with their historical experiences influence how language is coded along with its symbols and metaphorical meanings (Watzlawik, 2013). Therefore, what is considered “real” or “unreal” is depicted in the language adopted in a specific socio-cultural context (Winch, 1964). To truly understand the concepts of magic and their significance, their use in a particular language needs to be considered (Winch, 1964). For researchers, this becomes relevant in the study of magic and its associated concepts. It acknowledges inherent (and often unconscious) biases that Western researchers continue to embed in their analysis of data from socio-culturally different contexts (Tambiah, 1990), a concern related to the third shortcoming mentioned above. For example, the categorical coding of data and cross-country comparisons by Massoumi (2019) and Szarata (2019) is based on their interpretations of responses provided, which is based on the language codes and subsequent metaphorical thinking and understandings of their cultural context, one that is considered Western. Subsequently in using these interpretations, the findings presented here are not entirely free of these biases.

Conclusion

Albeit the study limitations, this study highlights and adds evidence to the omnipresence of magical thinking and practices. It also illustrates the relevance of reanalysing data from historical periods in understanding how cultural phenomena move in time and space and sheds light on opportunities for future research in magical thinking and behaviour. Previous research has focused on cross-cultural comparison of magical thinking and behaviour, also contributing to a better understanding of the complex mental life of the human being. Nevertheless, there is still more to be learned about magical thinking and behaviour. Indeed, a turn towards a cultural psychology approach to understanding magical thinking, for example, could provide such new insights. After all, magic is largely a matter of individual opinion, as it means various things to different people (Gray, 1969). Consequently, the subjective nature of magical thinking also begs us to be cautious about accepting observers’ definitions of magic and magical thinking. Instead, by exploring the meaning-making processes behind magical thinking and behaviour, we could acquire a deeper understanding of the adaptive nature of magical thinking and consider its relevance for clinical psychology practice.

References

Bailey, M. D. (2006). The meanings of magic. Magic, Ritual, and Witchcraft, 1(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1353/mrw.0.0052

Blair, C., & Ursache, A. (2011). A bidirectional model of executive functions and self-regulations. In K. D. Vohs & R. F. Baumeister (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications (2nd ed, pp. 300–320). Guilford Press.

Bocci, L., & Gordon, P. K. (2007). Does magical thinking produce neutralising behaviour? An experimental investigation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(8), 1823–1833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2007.02.003

Brashier, N. M., & Multhaup, K. S. (2017). Magical thinking decreases across adulthood. Psychology and Aging, 32(8), 681–688. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000208

Brooke, J. H. (1991). Science and religion: Some historical perspectives. Cambridge University Press.

Gmelch, G. (1971). Baseball magic. Trans-Action, 8(8), 39–41.

Gray, W. G. (1969). Magical ritual methods. Helios Book Service.

Heine, S. (2000). On the origin of magical thinking in the contemporary context: Using Robert Musil’s ‘Tonka’ as a literary case study. Archive for the Psychology of Religion, 23(1), 81–101. https://doi.org/10.1163/157361200X00078

Hopfe, L. M., & Woodward, M. R. (2009). Religions of the world (11th ed.). Pearson Education.

Inzlicht, M., Werner, K. M., Briskin, J. L., & Roberts, B. W. (2021). Integrating models of self-regulation. Annual Review of Psychology, 72, 319–345. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-061020-105721

Lave, J. (1988). Cognition in practice: Mind, mathematics and culture in everyday life. Cambridge University Press.

Massoumi, R. (2019). Magisches Denken im Erwachsenalter: Ein Ländvergleich [Magical thinking in adulthood: A country comparison]. Karl-Franzens-Universitaet Graz.

Mayer, C.-H. (2015). Magie und magisches Denken in der Aufstellungsarbeit—Eine gesunde Sache? [Magic and magical thinking in group work: A healthy option?]. In C.-H. Mayer & S. Hausner (Eds.), Salutogene Aufstellungen: Beitraege zur Gesundheitsfoederung un der systemischen Arbeit (pp. 33–54). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Meyer, M., & Mirecki, P. (Eds.). (1995). Ancient magic and ritual power. BRILL.

Miller, P. H. (2016). Theories of developmental psychology (6th ed.). Worth Publishers Macmillan Learning.

Mitchell, A. (1984). Individuality and hubris in mythology: The struggle to be human. American Journal of Psychoanalysis, 44(4), 399–412. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01252542

Moro, P. A. (2017). Witchcraft, sorcery, and magic. In H. Callan (Ed.), The International Encyclopedia of Anthropology (pp. 1–9). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118924396.wbiea1915

Moscovici, S. (2014). The new magical thinking. Public Understanding of Science, 23(7), 759–779. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662514537584

Muchow, M. (1928). Fragebogen des Hamburger Psychologischen Laboratoriums über persönliche Bräuche [Questionnaire of the Hamburg Psychological Laboratory about personal customs]. Zeitschrift Für Pädagogische Psychologie Und Jungenkunde, 29(8), 494–496.

Nemeroff, C., & Rozin, P. (1989). ‘You are what you eat’: Applying the demand-free ‘impressions’ technique to an unacknowledged belief. Ethos, 17(1), 50–69.

Nemeroff, C., & Rozin, P. (1994). The contagion concept in adult thinking in the United States: Transmission of germs and of interpersonal influence. Ethos, 22(2), 158–186.

Nemeroff, C., & Rozin, P. (2000). The makings of the magical mind: The nature and function of sympathetic magical thinking. In K. S. Rosengren, C. N. Johnson, & P. L. Harris (Eds.), Imagining the impossible: Magical, scientific, and religious thinking in children. Cambridge University Press.

Nemeroff, C., & Rozin, P. (2002). Sympathetic magical thinking: The contagion and similarity ‘Heuristics.’ In T. Gilovich, D. Griffin, & D. Kahneman (Eds.), Heuristics and Biases: The Psychology of Intuitive Judgement (pp. 201–216). Cambridge University Press.

Ogden, T. H. (2010). On three forms of thinking: Magical thinking, dream thinking, and transformative thinking. The Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 79(2), 317–347. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2167-4086.2010.tb00450.x

Otto, B. C. (2019). If people believe in magic, isn’t that just because they aren’t educated? In W. J. Hanegraaff, P. J. Forshaw, & M. Pasi (Eds.), Hermes explains: Thirty questions about western esotericism (pp. 198–206). Amsterdam University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvx8b74s

Rathore, F. A., & Farooq, F. (2020). Information overload and infodemic in the COVID-19 pandemic. The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association, 70(Suppl 3)(5), S162–S165. https://doi.org/10.5455/JPMA.38Format:

Rosengren, K. S., & French, J. A. (2013). Magical thinking. In T. Marjorie (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of the development of imagination (pp. 42–60). Oxford University Press.

Rosengren, K. S., & Hickling, A. K. (2000). Metamorphosis and magic: The development of children’s thinking about possible events and plausible mechanisms. In K. S. Rosengren, C. N. Johnson, & P. L. Harris (Eds.), Imagining the impossible: Magical, scientific, and religious thinking in children (pp. 75–98). Cambridge University Press.

Rosengren, K. S., Johnson, C. N., & Harris, P. L. (Eds.). (2000). Imagining the impossible: Magical, scientific, and religious thinking in children. Cambridge University Press.

Rozin, P., Millman, L., & Nemeroff, C. (1986). Operation of the laws of sympathetic magic in disgust and other domains. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50(4), 703–712.

Shweder, R. A., Casagrande, J. B., Fiske, D. W., Greenstone, J. D., Heelas, P., & Laboratory of Comparitive Human Cognition, & Lancy, D. F. (1977). Likeness and likelihood in everyday thought: Magical thinking in judgments about personality [and comments and reply]. Current Anthropology, 18(4), 637–658. https://doi.org/10.1086/201974

Simpkin, A. L., & Schwartzstein, R. M. (2016). Tolerating uncertainty—The next medical revolution? New England Journal of Medicine, 375(18), 1713–1715. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1606402

Sørensen, J. (2007). A cognitive theory of magic. Rowman Altamira.

Sørensen, J. (2008). Magic among the Trobianders: Conceptual mapping in magical rituals. Cognitive Semiotics, 3, 36–64. https://doi.org/10.3726/81606_36

Styers, R. (2004). Making magic: Religion, magic, and science in the modern world. Oxford University Press.

Subbotsky, E. (2010). Magic and the mind: Mechanisms, functions, and development of magical thinking and behavior. Oxford University Press.

Subbotsky, E. (2011). The ghost in the machine: Why and how the belief in magic survives in the rational mind. Human Development, 54, 126–143. https://doi.org/10.1159/000329129

Szarata, V. (2019). Magisches Denken in verschiedenen Kulturen-Ein Laendervergleich bezueglich Anwendungs-praktiken und der Rektion auf Wirkungslosigkeit [Magical thinking in different cultures- a country comparison on application practices and strategies adopted for their ineffectiveness]. Freie Universitaet Berlin.

Tambiah, S. J. (1990). Magic, science and religion and the scope of rationality. Cambridge University Press.

Tangcharoensathien, V., Calleja, N., Nguyen, T., Purnat, T., D’Agostino, M., Garcia-Saiso, S., Landry, M., Rashidian, A., Hamilton, C., AbdAllah, A., Ghiga, I., Hill, A., Hougendobler, D., van Andel, J., Nunn, M., Brooks, I., Sacco, P. L., Domenico, M. D., Mai, P., & Briand, S. (2020). Framework for managing the COVID-19 infodemic: Methods and results of an online, crowdsourced WHO technical consultation. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(6), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.2196/19659

Universität Hamburg. (2010). Martha Muchow: Historische Dokumente entdeckt [Martha Muchow: Historical documents discovered]. UHH Newsletter. https://www.uni-hamburg.de/newsletter/archiv/Februar-2010-Nr-11/Martha-Muchow-Historische-Dokumente-entdeckt.html

Versnel, H. S. (1991). Some reflections on the relationship magic-religion. Numen, 38(2), 177–197. https://doi.org/10.2307/3269832

Walker, W. E., Harremoës, P., Rotmans, J., van der Sluijs, J. P., van Asselt, M. B. A., Janssen, P., & Krayer von Krauss, M. P. (2003). Defining uncertainty: A conceptual basis for uncertainty management in model-based decision support. Integrated Assessment, 4(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1076/iaij.4.1.5.16466

Watzlawik, M. (2013). Do you believe in magic? Symbol realism and magical practices. Culture & Psychology, 19(4), 506–517. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X13500326

Watzlawik, M., & Valsiner, J. (2012). The making of magic: Cultural constructions of the mundane supernatural. In J. Valsiner (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Culture and Psychology (pp. 783–795). Oxford University Press.

Winch, P. (1964). Understanding a primitive society. American Philosophical Quarterly, 1(4), 307–324.

World Health Organization. (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation report, 86. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331784

Zusne, L., & Jones, W. H. (2014). Anomalistic psychology: A study of magical thinking (2nd ed.). Psychology Press.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the participants for sharing their experiences. Special thanks go to Asil Özdoğru, Kübra Nur Çömlekçi, Min Han, and Hislop College, Lady Amritbai Daga College for Women, and Nagpur University who all helped collect or collected data in Turkey, South Korea, and India.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Namdiero-Walsh, A., Massoumi, R., Szarata, V. et al. Does Magical Thinking Bind or Separate Us? A Re-analysis of Data from Germany, India, South Korea, and Turkey. Hu Arenas (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42087-022-00309-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42087-022-00309-3