Abstract

This paper contains a narrative review of the literature in the field of school-based mind–body interventions (MBIs). The aim of the current review is to verify whether the school-based MBI programs implemented in primary and secondary schools over the past 5 years are effective in helping schoolchildren cope with stress-related, behavioral, and affective issues, as well as improve stress response and school performance. All articles were retrieved using a number of databases. Inclusion criteria comprised qualitative and quantitative, English language, and peer-reviewed studies among third graders (8–9 years old) to twelfth graders (17–18 years old), including special needs pupils. Qualitative studies were limited to pupils’ experience only. Ten studies meeting the criteria for this review were assessed. The school-based interventions included yoga-based programs and mindfulness training. Evidence was evaluated and summarized. Across the reviewed studies, we found support for MBIs as part of school curricula to reduce negative effects of stress and promote overall well-being with caveats to consider in choosing specific programs. The practical implications of the current review include considerations related to the incorporation of MBIs in school curricula, which would likely benefit schoolchildren.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mind–body interventions (MBIs) are based on a number of practices designed to work on a physical and mental level in such a way as to enhance the mind’s positive impact on the body (Rossi et al. 2006, 2011). They include ancient practices for self-care and well-being such as meditation, yoga, and tai chi, as well as more modern western practices, such as hypnosis, autogenic training, mindfulness, biofeedback, guided imagery, arts therapy, relaxation training, and psychological therapies. The list is ever growing and includes new practices developed over the past few decades that integrate psychology, consciousness, and body movement such as eye movement desensitization reprocessing (Chen et al. 2018; Fernandez and Faretta, 2007), mind–body transformation therapy (Cozzolino 2016; Cozzolino et al. 2020; Cozzolino et al. 2020; Rossi et al. 2013), and brain wave modulation technique (Cozzolino et al. 2020; Cozzolino and Celia 2016). Despite theoretical and practical differences in these approaches, they are all meant to promote the mind–body connection.

A growing body of research suggests that MBIs can have a number of positive effects on both healthy and clinical subjects, including the reduction of perceived stress (Gallego et al. 2016; Lolla 2018; Noordali et al. 2017; Paul et al. 2013), decreases in anxiety and depression (Gallego et al. 2016; Jeitler et al. 2017; Noordali et al. 2017; Paul et al. 2013; Regehr et al. 2013; Veehof et al. 2016), or improvements in chronic illness (Buric et al. 2017; Carlson et al. 2017; Montgomery et al. 2017; Paul et al. 2013). On the other hand, it must be noted that negative side effects were found in some participants of these interventions. In a review (Cramer et al. 2013), yoga was found to cause adverse events that mainly affected the musculoskeletal, nervous, or visual system. Moreover, mindfulness treatments can cause people to forget or dismiss thoughts that may be beneficial or protective if remembered (Wilson et al.2015).

Even though research seems to indicate that mind–body techniques are effective in enhancing psychologic and physical health, there is still poor understanding of the underlying mechanisms (Buric et al. 2017). The efficacy of mind–body practices seems to be associated with their capability of reducing the sympathetic physiological response to stress by activating the parasympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) and by regulating the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis (Sawni and Breuner 2017). Moreover, they are also shown to increase neuroplasticity, heart rate variability, EEG synchrony, and oxygenation (Buric et al. 2017; Lee et al. 2015; Murata et al. 2004). In recent years, the effects of yoga, mindfulness, mindful meditation, and therapeutic hypnosis have also been investigated by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies (Aleksandrowicz et al. 2006; Desai et al. 2015; Falcone and Jerram 2018; Ives-Deliperi et al. 2011). As these neuroimaging studies suggest that these practices have a positive impact on the cerebral systems governing attention and are also capable of inducing positive changes to mental and behavioral experience.

Evidence also suggests that the mind and body communicate through neurochemical and immunological pathways (Atkinson et al. 2010; Celia 2020; Cozzolino et al. 2017; Cozzolino et al. 2020; Sawni and Breuner 2017; Venuleo et al. 2018). Recent research in this field has focused on epigenetic mechanisms, that is to say molecular processes modulating gene expression, which can induce long-term changes in the genome (Cozzolino et al. 2017; Kanherkar et al. 2017; Rossi et al. 2006, 2011). Epigenetic mechanisms regulate the interaction between genes and environment through the so-called activity or experience-dependent genes, which become active when they capture environmental, psychological and social cues (Battuello et al. 2012; Cozzolino et al. 2017; Cozzolino et al. 2020; Rossi et al. 2008). These studies indicate a correlation between mind–body practices and epigenetic state (Kanherkar et al. 2017). Therefore, it is hypothesized that MBIs help control or change the expression of inflammatory genes (Buric et al. 2017). Consequently, this mind–body effect also has a positive impact on the processes underlying specific diseases (Cozzolino et al. 2015; Cozzolino et al. 2020).

Notwithstanding a growing number of studies on adult populations, some research indicates that there are relatively few studies on the effects of these interventions within a school setting (Bennett and Dorjee 2016; Šouláková et al. 2019). School-based MBI programs are typically aimed at improving well-being and preventing mental illness among children and adolescents.

Crucial developmental transitions, such as physical growth and cognitive, language, and moral development, take place during childhood and adolescence. Over this time, individuals have to solve problems and find opportunities related to schooling and personal life (Alivernini et al. 2019; Duprey et al. 2018; Girelli et al. 2019, 2020; Lucidi et al. 2019). In doing so, they develop behaviors that will probably last over the entire course of their lives. It is no surprise, then, that many adults’ mental issues have their onset during developmental years, when children and adolescents spend many hours at school (Girelli et al. 2018; Kessler et al. 2007). A great number of chronic mental illnesses have an early onset prior to 14 years, with anxiety disorders emerging at around 7, and suicide rates being particularly high in adolescence (Šouláková et al. 2019).

Since school-based MBIs are aimed at enhancing mental health, they may play a very important role in helping schoolchildren cope with several mental and physical conditions such as chronic illness, anxiety, depression, phobias, anger, grief, bereavement, etc. (Rocco et al. 2018; Sawni and Breuner 2017). This is consistent with findings from a recent meta-analysis of mindfulness-based interventions among youth (Klingbeil et al. 2017) where these interventions exhibited small, positive effects comparable to those obtained in clinical settings.

Moreover, MBIs imply teachable skills that children and adolescents (if not severely mentally impaired) can learn without great effort, and, if administered by trained professionals, they are safe and functional (Sawni and Breuner 2017).

Mind–body interventions in school settings can be carried out in several ways. They can be used with a single individual or with groups of students who are experiencing difficulties; as regards timing, they can be conducted in the classroom setting during regular class time, over lunch or during study breaks, or even throughout the school environment (Šouláková et al. 2019). Schools often choose to implement the type of intervention that best fits their needs and is most approved by school personnel and parents.

Owing to the importance of the matter, we conducted this narrative review to verify whether the mind–body programs implemented in primary and secondary schools over the past 5 years, included in this review, support the hypothesis that these programs are effective in helping schoolchildren cope with behavioral and affective issues, as well as improve stress response and school performance. The practical implications of the findings of this review include considerations related to the incorporation of MBIs in school curricula.

Method

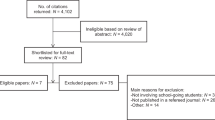

An extensive literature search was conducted using Scopus, Web of Science Core Collection, and PubMed. The databases were searched for the following keywords: school-based mind–body intervention, stress management, school performance, affect regulation, behavioral disturbances. Inclusion criteria comprised qualitative and quantitative, English language, peer-reviewed studies focusing on the effects of school-based mind–body interventions on stress, performance, behavior, and affect among third graders (8–9 years old) to twelfth graders (17–18 years old), including special needs pupils. Qualitative studies were limited to pupils’ experience only. We chose such inclusion criteria based on our research interest to prepare the grounds for our future studies. In fact, our line of experimental research includes investigation of innovative neuroscientific based mind–body techniques (Cozzolino et al. 2020; Cozzolino et al. 2020; Cozzolino et al. 2020) among university students, which we are planning to experiment with schoolchildren as well. Moreover, in order to provide a state-of-the-art picture of the designated subject, time restraint was applied, and articles were chosen dating from 2015 to 2019. In the references chosen, mind–body therapies were used either alone or as an adjunct to other interventions. In the case of control studies, control groups were exposed to several conditions, ranging from no intervention to regularly scheduled physical education. Overall, 115 references were found using the keywords and the time restraints chosen. Of the 115 references found, 68 were excluded based on the article title, and 47 were considered based on relevance. Out of the 47 references, 33 studies were selected based on the abstract. Applying the selection criteria led to the exclusion of 23 of those studies. Within those studies, nine were excluded, because they were reviews or meta-analyses, seven were non-school-based, and seven fell outside the time range chosen (Fig. 1).

Results

A total of ten studies met the inclusion criteria and were reviewed for this article, gathering a total of 858 patients (Table 1). Of these, nine were conducted in the USA, and one in Israel. Both qualitative and quantitative studies were included; while four of the studies were randomized controlled trials (RCTs), as summarized in Table 2, the others were mostly quasi-experimental studies, as summarized in Table 3. The number of participants varied from a minimum of 20 to a maximum of 211 subjects. Of the ten studies selected, three were related to elementary school students (Butzer et al. 2015; Keller et al. 2019; Tarrasch 2018); three included middle school students (Butzer et al. 2017; Butzer et al. 2017; Frank et al. 2017); one was related to sixth grade students only (Kang et al. 2018); two included high school students (Butzer et al. 2015; Fishbein et al. 2016); and one was related to elementary to middle school students (Sarkissian et al. 2018). Overall, three of these studies were related to students with special educational needs: one was carried out in a high-poverty area (Frank et al. 2017), one was related to high-risk adolescents (Fishbein et al. 2016), and another was related to students with a specific learning disability (Keller et al. 2019).

As to the type of intervention, the majority of the studies reviewed in this paper included yoga-based programs, such as the kripalu yoga in the schools (KYIS) curriculum (used in two studies), your own greatness affirmed (Y.O.G.A.) for youth, yoga for classrooms (Y4C), mindful yoga, and transformative life skills (TLS). Although these programs are based on spiritual practices, they are all completely secular and do not endorse any kind of spiritual orientation. The KYIS program curriculum aims to stimulate affective regulation, relational competence, and self-confidence. It includes Kripalu yoga techniques such as self-observation without judgment, self-regulation, and compassion meditation (Butzer et al. 2017). The Y.O.G.A. for youth program includes yoga and meditation. It aims at giving youth tools for self-discovery, and also helps them to focus mentally in order to fulfill “their own greatness” (Sarkissian et al. 2018). The Y4C program includes the key aspects of classical yoga and focuses on self-regulation (Butzer et al. 2015). The mindful yoga curriculum includes key mindfulness principles (e.g., concentration on breath, a non-judgmental attitude, cognitive and emotional awareness, etc.) and the use of mindfulness skills to cope with stressful situations. The yoga style is hatha vinyasa flow (Fishbein et al. 2016). The TLS program is a classroom-based program that includes yoga exercise, breathing, and meditation to reduce stress and stimulating physical and emotional wellness (Butzer et al. 2015). The remaining studies included mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) and mindfulness meditation techniques. MBSR includes the practice of exercises aimed at promoting awareness of physical, emotional, affective, and cognitive states. The exercises include challenges that require children to practice mindful walking or mindful eating (Tarrasch 2018). The mindfulness meditation techniques include breathing, and cognitive, affective, and body awareness exercises. They may also include meditation sessions (Kang et al. 2018).

The mind–body interventions assessed in these studies varied in program duration and frequency of sessions, from one to four times a week over periods of 6 weeks to 6 months. Some of these studies indicated that MBIs could have a positive impact on students’ behavior and stress management. In a study carried out by Butzer et al. (2015) on the effects of a 10-week classroom-based yoga intervention on cortisol concentrations and perceived behavior in second and third graders, results revealed a significant decrease in cortisol levels in the second graders only, and improvement in behavior and ability to control anger and to deal with stress and anxiety in all participants, though the third graders showed fewer improvements than the second graders. Furthermore, a study by Frank et al. (2017) aimed at assessing the effectiveness of a yoga-based social-emotional wellness promotion program (TLS), on emotional distress, prosocial behavior, and school functioning in adolescents attending an inner-city school district. Results suggested significant reductions in the number of unexcused absences and incarcerations. Moreover, significant increases were found in student emotion regulation, positive thoughts, and stress coping. As to the measures of physical symptoms, suspensions, school grades, and overall affect, there were no significant effects. Qualitative data were obtained through student reports. Most participants showed appreciation for the intervention and also found it to be effective with regards to social behavior.

Other studies from this review suggested the effectiveness of MBIs on cognitive functioning and academic performance. A study (Tarrasch 2018) investigated the effects of mindfulness practice on sustained and selective attention in small groups of primary school children. The intervention group received a 10-week mindfulness intervention. Results revealed significant improvement in both sustained and selective attentional tasks and a general reduction in impulsivity in the experimental group as compared to the control group. These results clearly bear crucial implications for children’s wellness and school functioning. Another study (Butzer et al. 2015) evaluated how a 12-week school-based yoga intervention influenced grade point average in ninth and tenth grade students. Although both groups showed a decline in grade point average, the control group showed a significantly greater decline than the yoga group. Both groups exhibited comparable declines once the yoga intervention was over. These results suggest that yoga may prevent declines in grade point average, but these effects may not endure after the intervention is over. A study by Keller et al. (2019) evaluated the effects of a mindfulness-based training on reading ability scores and attitudes in children with learning disabilities. Participants were assigned to either an active control or a 5-week mindfulness-based intervention. Results of the quantitative analysis indicated a significant rise in response times during decoding and lowered heart rate. The themes that emerged from qualitative analysis indicated improvements in reading ability and general affect.

Another group of studies from this review focused on the efficacy of MBIs in reducing cigarette smoking and substance use in high-risk adolescents. A pilot randomized controlled trial (Fishbein et al. 2016) was conducted to test the efficacy of a 20-session mindful yoga intervention for reducing substance use in students at high-risk for dropping out. Results showed that the yoga group, as compared to control, were less willing to use alcohol and also received more positive social skill ratings from teachers. Yet, there were no significant effects on impulsivity, affect, or engagement coping. In a similar vein, Butzer et al. (2017) conducted a randomized controlled trial to test whether yoga was effective in reducing risk factors for substance use in seventh grade students. The intervention consisted of 32 yoga sessions as compared to physical-education-as-usual in the control group. Results indicated that immediately after the intervention students in the control group, compared to the yoga group, were significantly more eager to attempt to smoke cigarettes. Findings also suggested that school-based yoga might have beneficial effects on smoke prevention in male and female adolescents. Moreover, improvement in emotional self-control was found, but only in females.

Other studies reviewed in this paper focused on the effectiveness of MBIs on students’ positive affect, resilience, and well-being. As a part of a group randomized controlled trial (Butzer et al. 2017), a qualitative examination of yoga (Butzer et al. 2017) was conducted considering how student perceived yoga in terms of such aspects as practicality, ease of learning, and direct results. Findings were mixed. Very positive opinions were related to the effects of yoga on stress, sleep, and relaxation, whereas generally positive opinions were related to affective self-regulation, sociability, substance use, and academic performance. Likewise, another study (Sarkissian et al. 2018) was carried out in urban inner-city schools, where disadvantaged children at high risk of behavioral and emotional problems were attending. The intervention consisted of a 10-week YOGA for Youth program aimed at investigating the effects of the program on student stress, affect, and resilience. The study also included informal qualitative interviews with schoolteachers, yoga teachers, and students to understand how the program was perceived. The quantitative results revealed significant improvement in stress, affect, and resilience in the participants. As for qualitative results, all participants (including schoolteachers and yoga teachers) reported that the program had improved students’ well-being. Moreover, a study by Kang (Kang et al. 2018) investigated gender as a possible moderator for emotional effects in response to school-based mindfulness training. The goal of the study was to improve emotional well-being in early adolescents. The intervention group completed short mindfulness meditation sessions as an adjunct to history teaching, whereas the control group received paired experiential activity in addition to history teaching from the same teacher without meditation. Pre- and post-intervention self-reported measures of emotional well-being, mindfulness, and self-compassion were acquired. Results show that the intervention group reported greater improvement in emotional well-being compared to the control group, with important gender differences. Female meditators, in fact, showed greater gains in positive affect compared to female controls, whereas both male meditators and male controls showed equivalent increases. Moreover, only females showed increases in self-compassion associated with improved affect. Overall, these findings indicate the efficacy of classroom-based mindfulness interventions and interventions that take into account the different developmental needs of female and male individuals.

Discussion

For this review, we assessed ten studies (indexed in Scopus, Web of Science Core Collection, and PubMed) on school students who received school-based yoga programs and school-based mindfulness training as an intervention. Among these studies, there were four RCTs, five single group studies, a qualitative research, and an exploratory examination. The studies reviewed suggest that school-based MBIs are successful in helping students cope with several personal and schooling difficulties. These studies mostly focused on the effects of school-based MBIs on students’ (1) behavior and stress management, (2) positive affect and well-being, (3) cigarette smoking and substance use, and (4) cognitive functioning and academic performance. The majority of these studies involved school-based yoga interventions such as the KYIS curriculum, Y.O.G.A. for youth, Y4C, mindful yoga, and TLS. The remaining studies involved school-based interventions using MBSR and mindfulness meditation techniques. These interventions were found to have beneficial effects on students’ relaxation, positive thinking, cognitive restructuring in response to stress, affect, resilience, mood, and emotion-regulation.

Clearly, this review has limitations. First, the included studies were broad and did not allow us to make any definitive statements. Second, our conclusions are only as good as the data and studies that we identified. Moreover, alongside results suggesting several significant beneficial effects, some of these studies found no effects on measures of self-control, involuntary engagement coping, somatization, or general affect; in a study, neither suspensions nor academic grades were affected by the intervention. A possible explanation for these findings is that the interventions had not been tailored to the developmental stage of the children receiving the programs (Šouláková et al. 2019). Furthermore, some of the studies were limited by factors such as the small number of subjects and the use of assessment tools, the validity and reliability of which were not recognized. Other limitations included the short duration of the intervention programs and a lack of active control groups.

The practical implications of these findings include considerations related to the incorporation of MBIs in school curricula. Across reviewed studies, we found some support for MBIs as part of school curricula to reduce negative effects of stress and promote overall well-being with caveats to consider in choosing specific programs. In fact, whereas mindfulness training had significant impact on students’ cognitive performance, attentional capacities, and emotional well-being, school-based yoga programs were found to be effective in improving students’ mental health and well-being, and decreasing their willingness to engage in unhealthy behaviors, such as smoking cigarettes or drinking alcohol. Moreover, these interventions may be used as preventive programs, which are especially suited to school settings where children spend most of the time, most of the year, during the developmentally important years of childhood and adolescence.

Conclusions

Notwithstanding the heterogeneity in terms of procedures, age range, and sample size, the studies reviewed seem to suggest some beneficial effects of school-based yoga and mindfulness programs. Although additional research is needed especially regarding the long-term effects of mind–body interventions in school settings, if schools incorporated these practices in their curricula, students would likely benefit from them.

References

Aleksandrowicz, J. W., Urbanik, A., & Binder, M. (2006). Imaging of hypnosis with functional magnetic resonance. Psychiatria Polska, 40(5), 969–983. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17217239

Alivernini, F., Cavicchiolo, E., Girelli, L., Lucidi, F., Biasi, V., Leone, L., et al. (2019). Relationships between sociocultural factors (gender, immigrant and socioeconomic background), peer relatedness and positive affect in adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 76, 99–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.08.011

Atkinson, D., Iannotti, S., Cozzolino, M., Castiglione, S., Cicatelli, A., Vyas, B., et al. (2010). A new bioinformatics paradigm for the theory, research, and practice of therapeutic hypnosis. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 53(1), 27–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/00029157.2010.10401745

Battuello, M., Roma, P., & Celia, G. (2012). Group psychotherapy for HIV patients. A different approach. Retrovirology, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4690-9-S1-P92

Bennett, K., & Dorjee, D. (2016). The impact of a mindfulness-based stress reduction course (MBSR) on well-being and academic attainment of sixth-form students. Mindfulness, 7(1), 105–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0430-7

Buric, I., Farias, M., Jong, J., Mee, C., & Brazil, I. A. (2017). What is the molecular signature of mind-body interventions? A systematic review of gene expression changes induced by meditation and related practices. In Frontiers in Immunology (Vol. 8, Issue JUN, p. 670). Frontiers Media S.A. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2017.00670

Butzer, B., Day, D., Potts, A., Ryan, C., Coulombe, S., Davies, B., et al. (2015). Effects of a classroom-based yoga intervention on cortisol and behavior in second- and third-grade students: A pilot study. Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 20(1), 41–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156587214557695

Butzer, B., LoRusso, A., Shin, S. H., & Khalsa, S. B. S. (2017). Evaluation of yoga for preventing adolescent substance use risk factors in a middle school setting: A preliminary group-randomized controlled trial. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(3), 603–632. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0513-3

Butzer, B., Marie LoRusso, A., Windsor, R., Riley, F., Frame, K., Bir Khalsa, S. S., & Conboy, L. (2017). A qualitative examination of yoga for middle school adolescents. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 3(10), 195–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/1754730X.2017.1325328

Butzer, B., Van Over, M., Noggle Taylor, J. J., & Khalsa, S. B. S. (2015). Yoga may mitigate decreases in high school grades. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2015, 259814. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/259814

Carlson, L. E., Zelinski, E., Toivonen, K., Flynn, M., Qureshi, M., Piedalue, K. A., & Grant, R. (2017). Mind-body therapies in cancer: What is the latest evidence? Current Oncology Reports, 19(10). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11912-017-0626-1

Celia, G. (2020). Les styles narratifs du groupe comme indicateurs de changement. Revue de Psychotherapie Psychanalytique de Groupe, 74(2).

Chen, R., Gillespie, A., Zhao, Y., Xi, Y., Ren, Y., & McLean, L. (2018). The efficacy of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing in children and adults who have experienced complex childhood trauma: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Frontiers in Psychology, 9(APR), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00534

Cozzolino, M. (2016). A psychosocial genomics research program in oncology (PSGPO) for verifying clinical, genomic and epigenetic effects of mind-body transformations therapy (MBT-T) in breast cancer patients. The International Journal of Psychosocial and Cultural Genomics: Health & Consciousness Research, 2(3), 34–41.

Cozzolino, M., & Celia, G. (2016). The neuroscientific evolution of Ericksonian approach as a metamodel of healing. The International Journal of Psychosocial and Cultural Genomics, Consciousness & Health Research, 2(1), 31–41.

Cozzolino, M., Celia, G., Rossi, K., & Rossi, E. L. (2020). Hypnosis as sole anesthesia for dental removal in a patient with multiple chemical sensitivity. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207144.2020.1762494

Cozzolino, M., Cicatelli, A., Fortino, V., Guarino, F., Tagliaferri, R., Castiglione, S., et al. (2015). The mind-body healing experience (MHE) is associated with gene expression in human leukocytes. International Journal of Physical and Social Sciences, 5(3), 361–374.

Cozzolino, M., Girelli, L., Vivo, D. R., Limone, P., & Celia, G. (2020). A mind–body intervention for stress reduction as an adjunct to an information session on stress management in university students. Brain and Behavior, 10(6). https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.1651

Cozzolino, M., Guarino, F., Castiglione, S., Cicatelli, A., & Celia, G. (2017). Pilot study on epigenetic response to a mind-body treatment. Translational Medicine @ UniSa, 17, 40. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6067070/

Cozzolino, Mauro, Celia, G., Rossi, K. L., & Rossi, E. L. (2020). Hypnosis as sole anesthesia for dental removal in a patient with multiple chemical sensitivity. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207144.2020.1762494

Cozzolino, Mauro, Celia, G., Vivo, D. R., Girelli, L., & Limone, P. (2020). Effects of the brain wave modulation technique administered online on stress, anxiety, global distress, and affect during COVID-19 pandemic: A randomized clinical trial. In Press.

Cozzolino, M., Vivo, D. R., Girelli, L., Limone, P., & Celia, G. (2020). The evaluation of a mind-body intervention (MBT-T) for stress reduction in academic settings: A pilot study. Behavioral Sciences, 10(8), 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs10080124

Cramer, H., Krucoff, C., & Dobos, G. (2013). Adverse events associated with yoga: A systematic review of published case reports and case series. PLoS ONE, 8(10). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0075515

Desai, R., Tailor, A., & Bhatt, T. (2015). Effects of yoga on brain waves and structural activation: a review. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 21(2), 112–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CTCP.2015.02.002

Duprey, E. B., McKee, L. G., O’Neal, C. W., & Algoe, S. B. (2018). Stressful life events and internalizing symptoms in emerging adults: The roles of mindfulness and gratitude. Mental Health and Prevention, 12, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhp.2018.08.003

Falcone, G., & Jerram, M. (2018). Brain Activity in Mindfulness Depends on Experience: a Meta-Analysis of fMRI Studies. Mindfulness, 9(5), 1319–1329. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0884-5

Fernandez, I., & Faretta, E. (2007). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing in the treatment of panic disorder with agoraphobia. Clinical Case Studies, 6(1), 44–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534650105277220

Fishbein, D., Miller, S., Herman-Stahl, M., Williams, J., Lavery, B., Markovitz, L., et al. (2016). Behavioral and psychophysiological effects of a yoga intervention on high-risk adolescents: A randomized control trial. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(2), 518–529. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0231-6

Frank, J. L., Kohler, K., Peal, A., & Bose, B. (2017). Effectiveness of a school-based yoga program on adolescent mental health and school performance: Findings from a randomized controlled trial. Mindfulness, 8(3), 544–553. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0628-3

Gallego, J., Aguilar-Parra, J. M., Cangas, A. J., Rosado, A., & Langer, Á. I. (2016). Efecto de intervenciones mente/cuerpo sobre los niveles de ansiedad, estrés y depresión en futuros docentes de edu. Revista de Psicodidactica, 21(1), 87–101. https://doi.org/10.1387/RevPsicodidact.13256

Girelli, L., Alivernini, F., Salvatore, S., Cozzolino, M., Sibilio, M., & Lucidi, F. (2018). Coping with the first exams: Motivation, autonomy support and perceived control predict the performance of first-year university students. Journal of Educational, Cultural and Psychological Studies, 2018(18), 165–185. https://doi.org/10.7358/ecps-2018-018-gire

Girelli, L., Cavicchiolo, E., Alivernini, F., Manganelli, S., Chirico, A., Galli, F., et al. (2020). Doping use in high-school students: Measuring attitudes, self-efficacy, and moral disengagement across genders and countries. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 663. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00663

Girelli, L., Cavicchiolo, E., Lucidi, F., Cozzolino, M., Alivernini, F., & Manganelli, S. (2019). Psychometric properties and validity of a brief scale measuring basic psychological needs satisfaction in adolescents. In Journal of Educational, Cultural and Psychological Studies (Vol. 2019, Issue 20, pp. 215–229). Edizioni Universitarie di Lettere Economia Diritto. https://doi.org/10.7358/ecps-2019-020-gire

Jeitler, M., Jaspers, J., von Scheidt, C., Koch, B., Michalsen, A., Steckhan, N., & Kessler, C. S. (2017). Mind-body medicine and lifestyle modification in supportive cancer care: A cohort study on a day care clinic program for cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology, 26(12), 2127–2134. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4433

Ives-Deliperi, V. L., Solms, M., & Meintjes, E. M. (2011). The neural substrates of mindfulness: an fMRI investigation. Social Neuroscience, 6(3), 231–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470919.2010.513495

Kang, Y., Rahrig, H., Eichel, K., Niles, H. F., Rocha, T., Lepp, N. E., Gold, J., & Britton, W. B. (2018). Gender differences in response to a school-based mindfulness training intervention for early adolescents. Journal of School Psychology, 68(December 2017), 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2018.03.004

Kanherkar, R. R., Stair, S. E., Bhatia-Dey, N., Mills, P. J., Chopra, D., & Csoka, A. B. (2017). Epigenetic mechanisms of integrative medicine. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2017(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/4365429

Keller, J., Ruthruff, E., & Keller, P. (2019). Mindfulness and speed testing for children with learning disabilities: Oil and water? Reading and Writing Quarterly, 35(2), 154–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573569.2018.1524803

Kessler, R. C., Amminger, G. P., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Lee, S., & Üstün, T. B. (2007). Age of onset of mental disorders: A review of recent literature. In Current Opinion in Psychiatry (Vol. 20, Issue 4, pp. 359–364). NIH Public Access. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0b013e32816ebc8c

Klingbeil, D. A., Renshaw, T. L., Willenbrink, J. B., Copek, R. A., Chan, K. T., Haddock, A., et al. (2017). Mindfulness-based interventions with youth: A comprehensive meta-analysis of group-design studies. Journal of School Psychology, 63, 77–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2017.03.006

Lee, J., Kim, J.-K., & Amy Wachholtz. (2015). The benefit of heart rate variability biofeedback and relaxation training in reducing trait anxiety. Korean Journal of Health Psychology, 20(2), 391–405. https://doi.org/10.17315/kjhp.2015.20.2.002

Lolla, A. (2018). Mantras help the general psychological well-being of college students: A pilot study. Journal of Religion and Health, 57(1), 110–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-017-0371-7

Lucidi, F., Girelli, L., Chirico, A., Alivernini, F., Cozzolino, M., Violani, C., & Mallia, L. (2019). Personality traits and attitudes toward traffic safety predict risky behavior across young, adult, and older drivers. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(MAR). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00536

Montgomery, G. H., Sucala, M., Dillon, M. J., & Schnur, J. B. (2017). Cognitive-behavioral therapy plus hypnosis for distress during breast radiotherapy: A randomized trial. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 60(2), 109–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/00029157.2017.1335635

Murata, T., Takahashi, T., Hamada, T., Omori, M., Kosaka, H., Yoshida, H., & Wada, Y. (2004). Individual trait anxiety levels characterizing the properties of Zen meditation. Neuropsychobiology, 50(2), 189–194. https://doi.org/10.1159/000079113

Noordali, F., Cumming, J., & Thompson, J. L. (2017). Effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions on physiological and psychological complications in adults with diabetes: A systematic review. Journal of Health Psychology, 22(8), 965–983. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105315620293

Paul, A., Cramer, H., Lauche, R., Altner, N., Langhorst, J., & Dobos, G. J. (2013). An oncology mind-body medicine day care clinic: Concept and case presentation. Integrative Cancer Therapies, 12(6), 503–507. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534735412473639

Regehr, C., Glancy, D., & Pitts, A. (2013). Interventions to reduce stress in university students: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 148(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.026

Rocco, D., Pastore, M., Gennaro, A., Salvatore, S., Cozzolino, M., & Scorza, M. (2018). Beyond verbal behavior: An empirical analysis of speech rates in psychotherapy sessions. Frontiers in Psychology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00978

Rossi, E., Iannotti, S., Cozzolino, M., Castiglione, S., Cicatelli, A., & Rossi, K. (2008). A pilot study of positive expectations and focused attention via a new protocol for optimizing therapeutic hypnosis and psychotherapy assessed with DNA microarrays: The creative psychosocial genomic healing experience. Sleep and Hypnosis, 10(2), 39–44.

Rossi, E. L., Cozzolino, M., Mortimer, J., Atkinson, D., & Rossi, K. L. (2011). A brief protocol for the creative psychosocial genomic healing experience: The 4-stage creative process in therapeutic hypnosis and brief psychotherapy. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 54(2), 133–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/00029157.2011.605967

Rossi, E. L., Rossi, K. L., Yount, G., Cozzolino, M., & Iannotti, S. (2006). The bioinformatics of integrative medical insights: Proposals for an international psycho-social and cultural bioinformatics project. Integrative Medicine Insights, 1(1), 7–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/117863370600100002

Rossi, K., Mortimer, J., & Rossi, E. (2013). Mind-body transformations therapy (MBT-T). A single case study of trauma and rehabilitation. The International Journal of Psychosocial Genomics Consciousness & Health Research, 1(1), 32–40.

Sarkissian, M., Trent, N. L., Huchting, K., & Khalsa, S. B. S. (2018). Effects of a Kundalini yoga program on elementary and middle school students’ stress, affect, and resilience. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 39(3), 210–216. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000538

Sawni, A., & Breuner, C. (2017). Clinical hypnosis, an effective mind-body modality for adolescents with behavioral and physical complaints. Children, 4(4), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/children4040019

Šouláková, B., Kasal, A., Butzer, B., & Winkler, P. (2019). Meta-review on the effectiveness of classroom-based psychological interventions aimed at improving student mental health and well-being, and preventing mental illness. Journal of Primary Prevention, 40(3), 255–278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-019-00552-5

Tarrasch, R. (2018). The effects of mindfulness practice on attentional functions among primary school children. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(8), 2632–2642. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1073-9

Veehof, M. M., Trompetter, H. R., Bohlmeijer, E. T., & Schreurs, K. M. G. (2016). Acceptance- and mindfulness-based interventions for the treatment of chronic pain: a meta-analytic review. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 45(1), 5–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2015.1098724

Venuleo, C., Mangeli, G., Mossi, P., Amico, A. F., Cozzolino, M., Distante, A., et al. (2018). The Cardiac Rehabilitation Psychodynamic Group Intervention (CR-PGI): An explorative study. Frontiers in Psychology, 9((JUN)), 976. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00976

Wilson, B. M., Mickes, L., Stolarz-Fantino, S., Evrard, M., & Fantino, E. (2015). Increased false-memory susceptibility after mindfulness meditation. Psychological Science, 26(10), 1567–1573. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615593705

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Salerno within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cozzolino, M., Vivo, D.R. & Celia, G. School-Based Mind–Body Interventions: A Research Review. Hu Arenas 5, 262–278 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42087-020-00163-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42087-020-00163-1