Abstract

In this quasi-experimental field study, we investigated the effects of a digital support tool on knowledge about, assessment of, and feedback on self-regulated learning (SRL). Student teachers (N = 119) took the roles of learners and teachers. As learners, they wrote learning journals and received feedback on the strategies they had used. As teachers, they assessed a peer’s learning strategies elicited in the learning journals and provided feedback. A digital tool supported the participants in their role as teachers by providing additional assessment support (yes/no) and feedback support (yes/no). Assessment support was realized with rubrics, feedback support was realized with sentence starters. Our results indicated that declarative and self-reported knowledge about SRL increased in all groups. Assessment support did not foster assessment skills, but feedback support fostered the quality of the peer feedback and feedback quality in a standardized posttest. High feedback quality, in turn, predicted learners’ application of organizational (but not metacognitive) strategies. We conclude that the combination of writing learning journals and providing peer feedback on SRL is a promising approach to promote future teachers’ SRL skills. Digital tools can support writing the feedback, for example, by providing sentence starters as procedural facilitators. Such support can help teachers supply high-quality feedback on SRL, which can then help learners improve their SRL.

Zusammenfassung

In dieser quasi-experimentellen Feldstudie untersuchten wir die Auswirkungen eines digitalen Unterstützungstools auf das Wissen über selbstreguliertes Lernen (SRL), das Diagnostizieren von SRL und Feedback zu SRL. Lehramtsstudierende (N = 119) übernahmen die Rolle der Lernenden und Lehrenden. Als Lernende schrieben sie Lerntagebücher und erhielten Feedback zu den von ihnen verwendeten Lernstrategien. Als Lehrende bewerteten sie die Lernstrategien eines Peers und gaben Feedback. Ein digitales Tool unterstützte die Teilnehmenden in ihrer Rolle als Lehrende, indem es zusätzliche Diagnostikunterstützung (ja/nein) und Feedbackunterstützung (ja/nein) bot. Das Diagnostizieren wurde durch die Vorgabe von Kriterien unterstützt, das Feedback durch Satzanfänge. Unsere Ergebnisse zeigten, dass das deklarative und selbstberichtete Wissen über SRL in allen Gruppen zunahm. Die Diagnostikunterstützung führte nicht zu besseren Diagnosefertigkeiten, aber die Feedbackunterstützung führte zu höherer Qualität des Peer Feedbacks und zu höherer Feedbackqualität in einem standardisierten Posttest. Diese höhere Feedbackqualität förderte wiederum die Anwendung von Organisationsstrategien (aber nicht metakognitiver Strategien) aufseiten der Lernenden. Insgesamt stellt die Kombination aus Lerntagebuch-Schreiben und Peer-Feedback-Geben eine vielversprechende Möglichkeit dar, um SRL-Kompetenzen angehender Lehrkräfte zu fördern. Dabei können digitale Tools das Schreiben des Feedbacks beispielsweise durch die Vorgabe von Satzanfängen (als procedural facilitators) unterstützen. Diese Unterstützung kann den Lehrenden dabei helfen, hochwertiges Feedback zu formulieren – um dann wiederum die Lernenden beim selbstregulierten Lernen voranzubringen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Self-regulatory learning skills prepare us for lifelong learning inside and outside formal institutions. There is thus broad consensus that teachers should help their students become self-regulated learners (e.g., Dignath and Veenman 2021; Porter and Peters-Burton 2021; Zimmerman 2002). In this regard, recent frameworks (e.g., Karlen et al. 2020; Kramarski and Heaysman 2021) acknowledged that teachers are also learners themselves—and that their own self-regulatory skills interact with their skills teaching self-regulated learning (SRL). To promote students’ SRL, future teachers should therefore become effective learners themselves (Dembo 2001; see also Heaysman and Kramarski 2022; Karlen et al. 2023; Kramarski and Kohen 2017; Porter and Peters-Burton 2021). From this perspective, teachers’ SRL-related skills, such as their knowledge about or assessment of SRL, result from their experiences as self-regulated learners and as facilitators (or “agents”; Karlen et al. 2020) of SRL. These skills shape the way they teach SRL to their students. At the end of this chain, there are students with self-regulatory skills that should improve with teachers’ support (Karlen et al. 2020).

In this study, we selected relevant components from these models (Karlen et al. 2020; Kramarski and Heaysman 2021) as well as from models of assessment competence (Herppich et al. 2018), provided targeted support by a digital tool, and examined the impact of that support at different levels. We instructed the participating future teachers to assume the roles of both self-regulated learners and SRL teachers. As learners, they wrote learning journals, that is, they applied learning strategies and reflected on their learning process, and received feedback from a peer on their learning journal. As teachers, they assessed their peers’ SRL elicited in the learning journals and provided feedback—which in turn also promoted their own SRL. A digital tool provided additional assessment support with rubrics, and/or feedback support with sentence starters. The central aim of the study was to investigate the direct effects of this supportive tool on knowledge about, assessment of, and feedback on SRL. Additionally, we explored indirect effects on learners’ SRL.

1.1 Teachers as self-regulated learners

Self-regulated learning means that learners engage in activities to develop knowledge and skills in a self-directed, purposeful, and proactive way. They set learning goals, plan their strategy use (forethought phase), observe and control the success of their strategies (performance phase), and evaluate their progress (self-reflection phase; see Zimmerman 2002). An essential characteristic of self-regulated learners is that they apply effective learning strategies, which differ in whether they activate cognitive processing (i.e., strategies that support knowledge construction directly) or metacognitive processing (i.e., strategies that regulate the process of knowledge construction; e.g., Roelle et al. 2017). Cognitive strategies aim, for example, to organize or elaborate knowledge. Organization means that the learners structure their knowledge, identify connections, and understand hierarchical relationships. Elaboration means that learners link new information to their prior knowledge, for example, by generating personal examples or creating analogies (Mayer and Clark 2001; Nückles et al. 2020). Metacognitive processing means “cognition about one’s own cognition” (Fiedler et al. 2019, p. 89) and includes monitoring of and, if needed, correcting cognitive processes (Fiedler et al. 2019). In the context of self-regulated learning, metacognitive strategies serve to plan, monitor, and regulate the learning process (Mayer and Clark 2001; Nückles et al. 2020).

Journal writing is an effective means to foster the application of learning strategies (e.g., Glogger et al. 2012; Hübner et al. 2010; for a review, see Nückles et al. 2020). In such a learning journal, learners reflect (while writing) on the learning contents and their understanding. They receive prompts that encourage them, for instance, to arrange the contents they have learned in a logical order (organization), link the new information to everyday experiences (elaboration), or write down what they have not yet understood (metacognition; see Nückles et al. 2020).

In addition to such prompts, elaborated feedback can foster SRL. For example, Nückles et al. (2005) instructed university students to write learning journals and provide feedback on a peer’s journal. Their feedback’s quality was strongly associated with the peer’s application of organization and elaboration strategies. Similarly, Roelle et al. (2011) found that feedback supported learners who had initially applied low-quality learning strategies to apply higher-quality strategies. In a study by Pieper et al. (2021), feedback on a learning journal increased the quality of reflection in the subsequent journal. Thus, high-quality feedback on learning strategies can be assumed to enhance learners’ subsequent use of strategies in journal writing.

With respect to the self-regulated learning cycle (Zimmerman 2002), both journal writing and feedback support the performance phase in particular, by encouraging the use of effective strategies (learning journal), providing information about the goals of effective strategies, and suggesting next steps for strategy use (feedback). However, both methods also support the self-reflection and forethought phase, as learners reflect on their own progress and write about next steps for their future learning (learning journal) and can use the feedback as a basis for self-reflection and planning (feedback).

1.2 Teachers as facilitators of SRL

Teachers’ own self-regulatory skills form the basis for their competence in teaching SRL to others (see Dembo 2001; Kramarski and Heaysman 2021). Drawing from frameworks by Karlen et al. (2020) and Herppich et al. (2018), we categorize these competences as (1) SRL-related dispositions, (2) assessment skills, and (3) SRL instruction (see Fig. 1).

-

1.

Teachers’ SRL-related dispositions result from their experiences as learners and teachers, and include knowledge about SRL—but also other cognitive or affective-motivational dispositions such as SRL-related beliefs and motivation (Karlen et al. 2020). Here, we focus on declarative knowledge about effective learning strategies (for a similar specification, see Glogger-Frey et al. 2018a). In addition to measuring knowledge with a standardized test, we also asked the student teachers to judge their own knowledge. Such self-judgments are relevant in educational research and practice as they prompt learners to evaluate their progress and engage in effective metacognitive strategies (Hausman et al. 2021; Metcalfe 2009). Teachers’ dispositions shape their ability to assess learning-related aspects, and, in turn, their instructional decisions. We hereby distinguish between assessment skills (e.g., applying specific strategies as cues for judging SLR) and subsequent instructional steps (e.g., providing feedback).

-

2.

Teachers’ assessment skills can be conceptualized as procedural knowledge (in contrast to the declarative knowledge about learning strategies described above), and include whether they can make accurate judgments about learners, their learning progress, and achievements (e.g., Herppich et al. 2018). In terms of formative assessment, teachers could, for example, learn from a learning journal about the strategies learners used and how well they worked (e.g., Glogger et al. 2012, 2013). However, teachers need guidance and training to make such assessments. Many future teachers have knowledge that does not allow them to properly assess learning strategies (Glogger-Frey et al. 11,12,a, b; Lawson et al. 2019). Providing teachers with definitional and quality criteria for learning strategies can support the assessment of learning strategies in authentic learning products, such as learning journal excerpts (e.g., Glogger-Frey et al. 2018b). One way to give assessors just-in-time scoring criteria is to use rubrics. Rubrics are scoring tools providing specific criteria for evaluating the objective of interest (e.g., Panadero and Jonsson 2013; Reddy and Andrade 2010). For example, rubrics could contain criteria for high-quality elaboration, and teachers could then rate to what extent those criteria were met. An exemplary rubric would be “Elaboration: An example is explained and closely related to the topic in a comprehensible way”. This rubric entails knowledge about learning strategies (here: an explained example is a specific instantiation of an elaboration strategy) and gives cues for evaluation (here: the example should be comprehensible and clearly related to the topic). Rubrics thus help assessors apply their knowledge to the specific learner’s product. In this way, rubrics can foster declarative and procedural knowledge about learning strategies, and potentially train assessment skills over time (e.g., Reddy and Andrade 2010).

-

3.

SRL instruction involves direct methods to foster students’ SRL (i.e., explicit instruction on learning strategies) and indirect methods (i.e., creating learning environments that support SRL; Dignath and Veenman 2021). In this study, we focus on how teachers provide feedback on students’ learning strategies and thus on a direct method to promote SRL. Feedback is a powerful tool for facilitating learners’ progress in general (Hattie and Timperley 2007)—and SRL in particular (see Nückles et al. 2020; Roelle et al. 2011). We focus on formative feedback, that is, feedback that refers to the process of learning (not the results) and is communicated with the intention to modify the leaners’ thinking or behavior (Shute 2008). Feedback should ideally address the learning goal (feed up), the current learning stage (feed back), and the next steps for achieving the learning goal (feed forward; see Hattie and Timperley 2007). Such feedback need not necessarily come from the instructors—peers can provide it also. In fact, peer feedback is known to improve academic writing (for a meta-analysis, see Huisman et al. 2019). Peer feedback can exert a twofold effect on learners: For one, learners benefit from receiving their peers’ feedback, potentially encouraging them to improve their own self-regulated learning (e.g., Ballantyne et al. 2002; Nückles et al. 2005). On the other hand, feedback writingFootnote 1 entails dealing with the learning goals and making criteria-based judgments, thus fostering deeper understanding of the learning contents and future academic performance (e.g., Andrade 2009; Huisman et al. 2018). However, providing feedback is challenging, and university students often have difficulty writing high-quality, content-related feedback for their peers (e.g., Kaufman and Schunn 2011; van den Berg et al. 2006). Even teacher students, who should be familiar with evaluating others’ academic achievements, have such difficulties (e.g., related to negative beliefs about peer feedback or feeling unconfident; Alqassab et al. 2018; Seroussi et al. 2019). It is therefore important to support this process, for example, via procedural facilitation. Procedural facilitators are tools that provide learners with a structure or memory aid for performing complex tasks (e.g., Baker et al. 2002). For example, sentence starters can serve as writing facilitators (Scardamalia et al. 1984). With respect to feedback, such sentence starters can give the writer ideas about how to phrase their feedback and help remember different aspects that feedback should contain. It can thus be assumed that such procedural facilitation supports feedback writers in deepening and applying their own (declarative and procedural) knowledge of learning strategies, while, for example, they elaborate on the goals of effective learning strategies (feed up).

Models of assessment competence (e.g., Herppich et al. 2018) highlight the difference between assessment and subsequent instruction as two distinct processes. Hence, supporting assessment with rubrics should mainly foster assessment skills, and supporting feedback with sentence starters should mainly foster feedback quality. Yet both processes are closely connected, as a correct assessment forms the basis for supplying precise feedback. Supporting both processes should therefore be most beneficial for teachers, especially when they have time to get accustomed to working with rubrics (see Bürgermeister et al. 2021).

1.3 Present study

The central aim of this study was to investigate the effects of a digital support tool on (student) teachers’ knowledge about, assessment of, and feedback on SRL. Participants took the roles of both learners and teachers by writing learning journals and receiving feedback (as learners), and by assessing learning strategies and giving feedback to their peers (as teachers). All were supported as learners by receiving prompts for journal writing and as teachers by using the tool for feedback writing. However, we varied whether the digital tool provided additional assessment support by rubrics (yes/no) and additional feedback support by sentence starters (yes/no). As dependent variables, we measured indicators of teachers’ SRL-related dispositions, assessment skills, and instruction (see Fig. 1). Regarding teachers’ SRL-related dispositions, we focused on declarative and self-reported knowledge about learning strategies. Regarding teachers’ assessment skills, we focused on their assessment of learning strategies from learning journals (i.e., procedural knowledge). Regarding SRL instruction, we analyzed feedback on learning strategies (peer feedback and feedback on a standardized learning journal).

We addressed the following research questions (RQ) and hypotheses:

RQ 1: Do assessment support (and feedback support) improve knowledge about learning strategies? We expected that declarative and self-reported knowledge about learning strategies would increase over time, as all participants engaged in activities that promoted a deeper understanding of effective learning strategies (journal writing; writing and receiving peer feedback). We furthermore expected that assessment support would especially deepen knowledge over time, as working with rubrics should help internalize criteria of effective learning strategies. Finally, we assumed that assessment support would be most effective together with feedback support over time, as the combination of rubrics and procedural facilitation should prompt participants in their roles as teachers to apply, deepen, and formulate their knowledge about learning strategies, especially if they train these skills in the course of a semester.

RQ 2: Do assessment support (and feedback support) improve the assessment of learning strategies? Assessment support in the form of rubrics should maximize the correct assessment (and justification) of learning strategies. We thus expected that assessment support would improve participants’ assessment skills in their roles as teachers in a standardized learning journal entry at the end of the semester. Given the assumed favorable effects of combining rubrics and procedural facilitation, we also expected that assessment support would be most effective together with feedback support.

RQ 3: Do feedback support (and assessment support) improve feedback quality? As procedural facilitation (e.g., in the form of sentence starters) can help writers apply their knowledge to their writing product, we expected that feedback support would raise peer feedback quality. This support should be most effective in combination with the rubrics (i.e., assessment support) and with sufficient training time. We also assessed feedback quality based on a standardized learning journal entry at the end of the semester. Similar to the expected effects on peer feedback, we expected that feedback support would raise feedback quality on this standardized learning journal, and that feedback support would be most effective in combination with assessment support.

Finally, we aimed to examine how the different forms of support affected learners’ SRL (RQ 4). Therefore, we coded how well participants used cognitive and metacognitive strategies in their learning journals (i.e., learners’ procedural knowledge). On the one hand, we examined whether the use of learning strategies increased over time in all groups as a result of regular engagement with the journals and feedback. On the other hand, we investigated whether there were indirect positive effects of feedback support on learning strategies via feedback quality (see Fig. 1). However, because the study design did not allow us to clearly separate effects on “learners” from effects on “teachers,” this research question was exploratory in nature. Participants who were supported as learners were also supported in their roles as teachers; thus, the effects of journal writing, feedback writing, and feedback receiving were too confounded to prove causal effects.

2 Method

2.1 Design and participants

We conducted a quasi-experimental study with a 2 × 2-design. Assessment support (with rubrics) and feedback support (with sentence starters) served as between-subject factors, thus leading to four experimental conditions: (1) assessment support, (2) feedback support, (3) both assessment and feedback support, and (4) no additional assessment or feedback support. We analyzed the data of 119 student teachersFootnote 2 (age: M = 21.81 years, SD = 3.79; 85% femaleFootnote 3; school types: 54% primary education, 44% secondary education, 3% special education). To analyze the learning strategies (RQ 4), we drew a small subsample consisting of those students that we could identify as tandem partners for the peer feedback (n = 34). All student teachers took part in an obligatory developmental psychology course, which was divided into 12 seminars. We allocated the seminars randomly to one of the four conditions (number of participants per condition: n1 = 36, n2 = 28, n3 = 31, n4 = 24).

A priori power analyses, based on analyses with four groups and two (three) points of measurement, medium effect sizes, and a power of 1 − β = 0.80 resulted in a desired sample size of 124 (136) participants. With our sample of 119 students, we have almost reached this goal, although the number of complete datasets was limited by practical-organizational problems (see footnote). The study complied with the German Psychological Society’s ethical guidelines as well as APA ethical standards. All participants were informed about taking part in research and could decline to participate without incurring any disadvantages. The learning journals and the peer feedback were mandatory for participants of the seminars; answering the questionnaires was voluntary. We pseudonymized (and later anonymized) all data so that the research team had no access to personal information about the students.

2.2 Materials

2.2.1 Learning journals

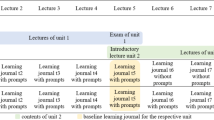

The students wrote seven learning journals throughout the semester (see Table 1) in which they reflected on the course’s contents and on their own learning process (Nückles et al. 2020). We used prompts to encourage cognitive and metacognitive strategies. For example, we asked that students provide a coherent overview of the learning contents (organization) or identify open questions (metacognition). The full instructions for writing the learning journals are provided as supplementary material. At the beginning, we informed the students about the purpose of journal writing and about the different learning strategies as recommended, for example, by Hübner et al. (2010).

2.2.2 Peer feedback

The students provided and received peer feedback three times during the semester (see Table 1). The feedback exchange was reciprocal, that is, a student gave feedback always to the same peer, and got feedback from that peer. At the beginning, we informed all students about the principles of good feedback (based on Hattie and Timperley 2007). Assessment support was realized with rubrics, which provided criteria for evaluating how well the peer had applied the learning strategies. A sample rubric for elaboration was “An example is explained and closely related to the topic in a comprehensible way”. Students rated the criteria on a six-point scale. Feedback support was realized with sentence starters, which prompted comments on the learning strategy’s aim (feed up), on how well the learning strategy had been applied (strength and weaknesses, feed back), and on subsequent steps (feed forward; see Hattie and Timperley 2007). Students were free to use and adapt as many sentence starters as they wanted. Note that the feedback support provided a structure for writing the feedback, but no contents about learning strategies. A sample feed-up sentence starter was “The aim of writing the learning journals is to …”.

All students used a digital tool to provide their feedback (see Fig. 2). This tool contained empty boxes for feedback on the three learning strategies (organizational, elaborative, and metacognitive strategies). Students needed to type at least 500 characters into a box. The tool had specific, interactive features: In the versions with assessment support, the tool processed the results of the strategy assessment and displayed them in aggregated form in the following step, when giving feedback. In the versions with feedback support, the tool moved the sentence starters that were clicked on to the text box for further editing. In the combined version, the tool automatically adapted the sentence starters to the results of the strategy assessment.

Digital tool with assessment support (rubrics) and feedback support (sentence starters). (This figure was adapted from Bürgermeister et al. 2021)

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Knowledge

We developed a questionnaire to measure declarative knowledge about learning strategies. The instruction was “Learning journals can serve as diagnostic tool for learning strategies. What do you think is important for assessing and fostering learning strategies with learning journals?” The students rated the items on a scale from 1 (= not important at all) to 6 (= very important). Five items referred to the different learning strategies (e.g., “show connections between the topics” for organization). The questionnaire also included four items that addressed irrelevant aspects (e.g., linguistic features). These items were analyzed separately (see supplementary materials). Students’ answers were recoded based on expert judgments. If an aspect had been correctly identified as important (five or six points), we assigned two points. If that aspect had been rated as quite important (four points), we assigned one point. If it had been (incorrectly) identified as unimportant (less than four points), we assigned zero points. We aggregated the items into a sum score (max = 10 points). Internal consistencies were acceptable (T1: α = 0.68, T8: α = 0.72). Self-reported knowledge about learning strategies was measured in the middle and at the end of the semester with two items: “The aims of learning strategies became clearer to me” and “The evaluation criteria of learning strategies became clearer to me”. The students agreed with the statements on a scale from 1 (= do not agree) to 4 (= agree very much). Internal consistencies were good (T5: α = 0.77, T8: α = 0.81).

2.3.2 Assessment skills

At the end of the study, we measured how well the students could assess learning strategies in a learning journal and how they justified their assessment (see Glogger-Frey et al. 2018b, 2022). All read the same (standardized) extract from a learning journal, which included a description of two elaboration strategies and one metacognitive strategy. We first analyzed assessment accuracy and assigned three points if a student had recognized all three strategies correctly, two points if two strategies had been recognized, and so forth. We also coded whether the students justified their assessment of elaboration and metacognition correctly. We assigned three points if students had described two (or more) correct aspects for justifying the chosen learning strategy, two points if they had described one correct aspect for justifying it, one point if students had assessed the correct strategy without justification, and zero points if students had not assessed the strategy. A second independent rater coded 30% of the answers. Interrater reliability was excellent for accuracy, ICC = 0.91, and acceptable for justification of elaboration and metacognition, ICC = 0.64 and ICC = 0.74.

2.3.3 Feedback quality

We coded content-related quality, adaptivity, and style of the peer feedback and standardized feedback via the coding scheme from Bürgermeister et al. (2021), based on Hattie and Timperley (2007). Content-related quality was analyzed separately for the different learning strategies (organization, elaboration, and metacognition). We coded the extent to which the feedback described (a) the learning strategy’s goal (feed up), (b) the strengths of how the learning strategy had been applied (feed back), (c) the weaknesses of how the latter had been applied (feed back), and (d) subsequent steps for applying the strategy successfully (feed forward). The codes ranged from 0 (= not described) to 3 (= precisely described). Furthermore, we coded whether (e) the next steps suggested matched the weaknesses that had been described on a scale from 0 (= no) to 2 (= yes). We aggregated the categories into a sum score (max = 14 points), thus obtaining three scores for the feedback quality on organization, elaboration, and metacognition.

In terms of adaptivity and style, feedback should be addressed personally to the recipient, adapted to the task to be evaluated, and written factually, comprehensibly, and constructively (Brookhart 2017; Hattie and Timperley 2007). Regarding adaptivity, we thus coded whether the feedback (a) addressed the feedback recipient personally on a scale from 0 (= no) to 2 (= yes), and (b) to what extent the feedback matched the underlying learning journal on a scale from 0 (= not matched) to 3 (= very good match), and then calculated a sum score for adaptivity (max = 5 points). Regarding feedback style, we coded whether the feedback was (a) written objectively, and (b) was clear and understandable on a scale from 0 (= no) to 2 (= yes), and then calculated a sum score for feedback style (max = 4 points).

The full coding scheme is provided as supplementary online file, including examples of the peer feedback. Twenty percent of the feedbacks were double-coded. ICCs ranged from 0.89 to 0.97, indicating good interrater reliability.

2.3.4 Learning strategies

We coded learning strategies from the learning journals with an established coding scheme (see Nückles et al. 2020) and according to the rubrics. For each strategy (organization, elaboration, and metacognition), we coded how well the strategy had been applied on a scale from 1 (= not applied) to 6 (= high-quality strategy application). A detailed description of the coding rationale is found in Glogger et al. (2012). Sample codings are provided as supplementary material. Ten percent of the feedbacks were double-coded. Due to problems with interrater reliability, we excluded elaboration from the analyses. ICCs for organization and metacognition ranged from 0.54 to 0.87, indicating acceptable interrater reliability.

2.4 Procedure

Table 1 illustrates the measurements taken during the semester. At the beginning, all students received information about the procedure and answered the knowledge questionnaire (T1). They then wrote their weekly learning journals (T2–T7), and provided feedback to their peer three times (T3, T5, and T7). In the middle of the semester (T5), they indicated their self-reported knowledge. At the end (T8), we assessed declarative and self-reported knowledge again. Students also read a standardized extract from a learning journal, assessed its learning strategies, and provided feedback to the (unknown) writer—this time without any scaffolds.

2.5 Data analysis

To analyze RQ 1–3, we conducted ANOVAsFootnote 4 with assessment support (yes vs. no) and feedback support (yes vs. no) as between-subject factors for variables measured once (assessment skills and standardized feedback), and with time as additional within-subject factor for all variables measured twice or three times (knowledge and peer feedback). We used Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons to break down significant interactions.

To analyze the learning journals (RQ 4), we drew a small subsample consisting of those participants (n = 34) that we could identify as tandem partners. For this subsample, we coded the learning journals at T2 and T7. Learning journals from six students were missing because of difficulty retrieving the documents or with code allocation; these missing values were replaced with the mean value of the respective learning strategy. To analyze indirect effects of feedback support on learning strategies via peer feedback quality, we conducted mediation analyses (Hayes 2013). We report 95%-confidence intervals derived from 5000 bootstrap samples to determine indirect effects; significant effects are characterized by intervals that exclude zero.

We used two-tailed significance tests and an alpha level of 0.05 to evaluate significance. To estimate effect sizes, we report partial eta-squared. Values of ηp2 = 0.01, 0.06, and 0.14 are regarded as small, medium, and large effects, respectively.

3 Results

3.1 Preliminary analyses

Table 2 presents descriptive values for the central measures. There were no differences between groups in prior knowledge (p = 0.93) or prior learning strategies (p = 0.48).

3.2 Do assessment support (and feedback support) improve knowledge about learning strategies? (RQ 1)

According to our hypothesis, we expected that declarative and self-reported knowledge about learning strategies would increase over time in all groups. Indeed, there were significant effects of time on declarative knowledge about learning strategies, V = 0.09, F (1,115) = 10.74, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.09 and on self-reported knowledge, V = 0.44, F (1,115) = 90.31, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.44. These findings confirm our hypothesis and indicate that participants’ engagement in journal writing and writing and receiving peer feedback promoted a deeper understanding of effective learning strategies.

We had furthermore expected that assessment support (versus no assessment support) would especially deepen knowledge over time. However, the interaction effect assessment × time was not significant, neither for declarative nor self-reported knowledge (ps > 0.22), thus contradicting our hypothesis.

Lastly, we had expected that assessment support would be most effective together with feedback support over time. The interaction effect assessment × feedback × time was not significant for declarative knowledge, but significant for self-reported knowledge, V = 0.04, F (1,115) = 4.86, p = 0.029, ηp2 = 0.04. Pairwise comparisons revealed that students given both kinds of support reported deeper knowledge at the end of the semester (T8) than those who received only assessment support, diff = 0.64, 95% CI [0.15, 1.13], p = 0.012. This difference was not significant (yet) in the middle of the semester (T5). Hence, the combination of rubrics and procedural facilitation supported participants’ (self-reported) knowledge about SRL, especially when they trained over a longer period of time.

3.3 Do assessment support (and feedback support) improve the assessment of learning strategies? (RQ 2)

According to our hypothesis, we expected that the rubrics (i.e., assessment support) would improve participants’ assessment skills at the end of the semester, and that assessment support would be most effective together with feedback support. However, we detected no effects of assessment support, feedback support, and no interaction (all ps > 0.19). These results contradict our hypothesis; the two kinds of support failed to help the students assessing learning strategies in a (standardized) learning journal when support was removed.

3.4 Do feedback support (and assessment support) improve feedback quality? (RQ 3)

We expected that procedural facilitation (i.e., feedback support) would improve feedback quality, and that this support would be most effective in combination with the rubrics (i.e., assessment support) and with sufficient training time. We determined feedback quality in the peer feedback and in the standardized feedback task (i.e., feedback on a standardized learning journal entry) at the end of the semester.

3.4.1 Peer feedback

We analyzed feedback quality separately according to the learning strategies the feedback related to (organization, elaboration, and metacognition). The effect of feedback support was significant for feedback on organization, F (1,115) = 25.26, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.18, feedback on elaboration, F (1,115) = 27.04, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.19, and feedback on metacognition, F (1,115) = 51.39, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.31. In addition to these content-related indicators, feedback support improved also adaptivity, F (1,115) = 17.78, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.13, and style, F (1,115) = 6.00, p = 0.016, ηp2 = 0.05. Hence, in line with our hypothesis, procedural facilitation (in the form of sentence starters) demonstrated substantial positive effects on peer feedback quality across all subcategories.

Furthermore, we had expected that feedback support would be most effective in combination with the rubrics (i.e., assessment support) and with sufficient training time. However, the interaction effect feedback × assessment × time was significant only for feedback on elaboration, V = 0.07, F (2,114) = 4.18, p = 0.018, ηp2 = 0.07. Pairwise comparisons revealed that students given both kinds of support wrote better feedback than those given only assessment support in the first peer feedback, diff = 3.95, 95% CI [2.51, 5.39], p < 0.001, and third peer feedback, diff = 1.04, 95% CI [0.01, 2.08], p = 0.048. Figure 3 illustrates this interaction: Assessment support showed a particular benefit in the first peer feedback, together with feedback support, but in the second and third peer feedbacks, this benefit fell to the level of feedback support only. These results support our hypothesis only for feedback on elaboration. Here, supporting both processes was more effective than supporting assessment only (but that effect was not stable over time).

3.4.2 Standardized feedback

At the last measurement, all participants provided feedback on a standardized extract of a learning journal, without any scaffolds. This extract contained elaboration and metacognition (not organization), so feedback referred only to these two learning strategies. We had to exclude 16 participants from this analysis because they failed to provide serious answers. In line with our hypothesis, the effect of feedback support was significant, V = 0.11, F (4,96) = 2.89, p = 0.026, ηp2 = 0.11. Univariate comparisons indicated that feedback support improved feedback quality on elaboration, F (1,99) = 4.59, p = 0.035, ηp2 = 0.04, and adaptivity, F (1,99) = 8.89, p = 0.004, ηp2 = 0.08, but not feedback on metacognition and feedback style (ps > 0.78). Thus, as expected, students receiving feedback support provided better feedback than those without feedback support. However, the interaction between assessment support and feedback support was not significant (p = 0.71). Hence, against our hypothesis, the rubrics revealed no additional benefit.

3.5 How do the different forms of support affect learners’ SRL? (RQ 4)

We performed additional analyses on the strategies that participants used in their role as learners. One the one hand, we examined whether the use of learning strategies increased over time in all groups. However, we detected no effect of time on learning strategies (organization and metacognition, both ps > 0.24), indicating that the application of learning strategies did not increase significantly during the semester.

On the other hand, we explored whether there were indirect positive effects of feedback support on learning strategies via feedback quality. We used mediation analyses with feedback support (yes vs. no) as independent variable and quality of the (received)Footnote 5 second peer feedback as mediator. The learning strategies (organization and metacognition) in the learning journal that followed the second peer feedback served as dependent variables. We added learning strategies in the first learning journal as a covariate to control for baseline differences. With respect to organization, feedback support predicted feedback quality, and feedback quality predicted organization (see Fig. 4). The direct and total effects of feedback support on organization were not significant, but we did note a substantial indirect effect of feedback support via feedback quality, b = 0.29, SE = 0.20, 95% CI [0.04, 0.80].

With respect to metacognition, all mediation paths were non-significant (ps > 0.20), indicating no direct or indirect influences of feedback support on metacognitive strategies via feedback quality. These findings indicate an indirect effect of feedback support via feedback quality for organization, but not for metacognitive strategies.

4 Discussion

In this study, we investigated the effects of a digital support tool that provided assessment support in the form of rubrics and feedback support in the form of sentence starters on teachers’ knowledge about, assessment of, and feedback on self-regulated learning, and explored indirect effects on learners’ SRL. Overall, declarative and self-reported knowledge about SRL increased in all groups. Assessment support did not foster assessment skills, but feedback support did foster the quality of peer feedback and feedback quality in a standardized posttest. High feedback quality, in turn, predicted learners’ application of organizational (but not metacognitive) strategies.

4.1 Teachers as facilitators of SRL: Effects on knowledge, assessment skills, and feedback

Declarative and self-reported knowledge about SRL increased substantially in all groups. Following recent frameworks (e.g., Karlen et al. 2020), teachers’ knowledge about SRL results from their experiences as learners and as facilitators of SRL. We thus assume that the mix of activities—writing learning journals and receiving feedback (as learners) and providing peer feedback (as facilitators)—deepened knowledge about learning strategies, even in the group that received no additional assessment or feedback support. This assumption concurs with research indicating that journal writing supports knowledge development (see Nückles et al. 2020), as do writing and receiving peer feedback (e.g., Andrade 2009). However, our results’ overall pattern was inconsistent with our hypotheses, as we had assumed that working with rubrics (assessment support) would primarily increase knowledge about SRL—as in previous studies in which rubrics fostered learners’ knowledge (e.g., Andrade 2001). A reason could be that learners need time and training to benefit from rubrics. Andrade (2005, p. 29) states that “even a fabulous rubric does not change the fact that students need models, feedback, and opportunities to ask questions, think, revise, and so on”. To maintain equal conditions for all groups in our study, we could not provide such opportunities. Hence, the students had time to get used to the rubrics but were given no particular training. Nevertheless, the rubrics showed a delayed beneficial effect on self-reported knowledge, in combination with feedback support. This result matches previous findings from this project (see Bürgermeister et al. 2021): Most advantageous for students’ self-efficacy over time was the support of both assessment and feedback writing. Once students got used to working with the rubrics and formulating their feedback, they became more confident of their assessment and feedback-giving skills. Similarly, our findings indicate that students given combined support judged their knowledge about SRL as high at the end of the semester. Such positive self-efficacy might deepen their motivation to engage with SRL—and even their actual performance as self-regulated learners and teachers (see Karlen et al. 2023).

We found that assessment skills were largely unaffected by both kinds of support. The groups did not differ in recognizing learning strategies or in how they justified their assessment. This result surprised us because we had expected students who had worked continuously with rubrics to outperform those without rubric support. Again, we must assume that students lacked opportunities to practice, ask questions, or receive feedback on their assessments (see Andrade 2005). In this regard, peer assessments are especially challenging and require training (Li et al. 2020).

Our feedback findings largely fulfilled our expectations: The sentence starters helped to provide adequate feedback on the learning strategies, and improved global characteristics such as adaptivity and writing style. Hence, in line with research on procedural facilitation (e.g., Baker et al. 2002; Scardamalia et al. 1984), these sentence starters served as a memory aids and provided ideas on how to phrase the feedback. However, the general reduction of strategy-related feedback quality (see descriptive values, Table 2) might be associated with the expertise-reversal effect: Instructional methods that help beginners may be superfluous or even detrimental for (emerging) experts, and should therefore fade with growing expertise (Sweller et al. 2011). In our study, the support remained stable over the entire semester for technical reasons. Students may have perceived the support tool’s scaffolds (e.g., the rubrics, sentence starters) as very helpful at the beginning—which might also explain the high initial values in the combined group, see Fig. 3—but as too restrictive once they gained more experience, which then resulted in lower-quality feedback.

4.2 Teachers as self-regulated learners: Effects on learning strategies

In terms of our learners, results were mixed. Learners’ application of learning strategies (i.e., their procedural knowledge) did not improve during the semester in general, only in combination with high-quality feedback as described below, although their (declarative) knowledge thereof increased. Students may have had sufficient knowledge about strategies from a teacher’s perspective (e.g., how can I assess effective strategies with a learning journal?) but they found it hard to transmit that knowledge to themselves as learners (e.g., how can I apply effective strategies myself?). The lack of such procedural, learner-related knowledge might thus have been one reason why our students failed to improve their own application of effective strategies (see production deficiency; e.g., Hübner et al. 2010). At the same time, the fact that learning strategies remained stable over the semester can also be interpreted as a positive sign, as it contradicts the downward trends described in similar studies. In a study by Nückles et al. (2010), for example, students wrote learning journals regularly over a semester. Those who received specific prompts applied better strategies at first, but then the use of these strategies decreased towards the end of the semester. The authors argue that the level of instruction (i.e., the prompts) should be adapted to learners’ increasing level of expertise. In the present study, there was adaptive, personalized instruction in terms of the peer feedback, which included suggestions for further writing (feed forward). Perhaps this adaptivity buffered the downward trend described by Nückles et al. (2010).

In our exploratory analyses, we noted an indirect effect of supporting (teachers’) feedback on learners’ application of organization strategies via feedback quality. If the tool helped with formulating the feedback, students provided better feedback on organization, and the peer receiving that feedback improved his or her application of this strategy in the subsequent learning journal. This finding is in line with previous research (e.g., Nückles et al. 2005; Pieper et al. 2021; Roelle et al. 2011). In these investigations, feedback effects were also more pronounced regarding cognitive strategies (such as organization) than for metacognitive strategies. For example, Roelle et al. (2011) detected no substantial feedback effect on metacognition, and in the study by Nückles et al. (2005), peer feedback was associated with application of cognitive but not metacognitive strategies. We suggest two reasons why feedback failed to promote metacognitive strategies. First, learners often find it hard to engage in metacognitive activities (e.g., Nückles et al. 2004), which is also reflected by our study’s low mean values (Table 2). Perhaps they need no prompts to activate, or feedback to evaluate these strategies, but instead specific training on how metacognitive strategies are applied. Second, feedback’s effects only unfold when people are willing and able to exploit it (e.g., Huisman et al. 2018). In the case of peer feedback, however, students may perceive their peers as being inadequately qualified to make judgments and suggestions (e.g., Kaufman and Schunn 2011), which might have lowered their acceptance of the feedback. In this regard, however, it is interesting that we observed a small positive (non-significant) effect of quality of the given feedback on metacognitive strategies (see supplementary materials). Perhaps, evaluating another person’s metacognitive strategies and making suggestions helps improving one’s own strategies, especially the monitoring process. Future studies should disentangle the effects of receiving and providing feedback on SRL—especially on metacognition—more systematically.

4.3 Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, limitations result from interdependencies within seminars and the tandems for the peer feedback. The quasi-experimental design had the advantage that students were unlikely to note and talk about the different experimental conditions, but it also had the disadvantage that conditions were confounded with seminar groups (e.g., with group-specific achievement or atmosphere). Furthermore, participants’ outcomes depended on their tandem partner (e.g., whether the partner uploaded the feedback regularly). In follow-up studies, we suggest assigning participants randomly to experimental conditions across seminars, and then using hierarchical multilevel modeling to consider differences on the seminar level. To reduce the risk of exchange about the different conditions, students could be informed that there are different scaffolds and that they will be given insight into all kinds of support at the end of the study. Third, our findings regarding teachers’ assessment of SRL are limited by the fact that we measured assessment skills only once at the end of the study, in a standardized task lacking scaffolds. Thus, we cannot know how accurately students assessed their peers’ learning journals in the course of the semester, and how the rubrics affected their assessments. Future studies could focus on this study aspect—SRL assessment—by investigating the accuracy and development of such peer assessments.

4.4 Implications for teacher education

The combination of writing learning journals and providing peer feedback on SRL appears to be a promising approach to strengthen future teachers’ SRL skills. These activities improve SRL-related knowledge and self-efficacy in particular (see also Bürgermeister et al. 2021), thereby raising the likelihood that teachers will later incorporate self-regulated learning in their classrooms. In this regard, teacher educators should keep in mind that teacher students are both future facilitators of SRL as well as self-regulated learners themselves. A course design resembling this study’s design incorporates both roles: The learner’s role is supported by reflecting, journal writing, receiving feedback, and so forth. The teacher’s role is supported by assessing a peer’s SRL and providing feedback. We suggest sentence starters as procedural facilitators for writing feedback. Rubrics might facilitate assessment support, but teacher educators might well need to demonstrate how to work with these rubrics, and provide opportunities for deliberate training. Finally, we find that combining learning journals, peer assessments, and peer feedback represents a fine opportunity to get insight into students’ learning processes in the sense of formative assessment, and to provide them with formative, individual feedback—especially in large courses.

Notes

Here, our focus was on how the received feedback affects SRL. However, additional analyses of giving feedback are provided as supplementary material.

The total sample consisted of 385 students; see Bürgermeister et al. (2021). However, as we aimed to analyze the quality of the peer feedback, we included only those students who had submitted all three peer feedbacks in our analyses. Therefore, only 30% of the initial sample’s datasets could be included in this study (n = 119). Out of this smaller sample, we were able to allocate feedback and learning journals for just another 30% (that is, n = 34). The dropouts occurred for personal reasons on the students’ part (e.g., absence times, delayed submissions) and for technical-methodological reasons (e.g., problems retrieving the documents, non-allocable codes). However, the dropouts were independent from experimental condition (ps > 0.35). We can thus rule out the possibility that dropouts affected results differently according to the kind of support the students received.

Gender distribution was equal in all four experimental groups (p = 0.89).

Shapiro Wilk’s tests indicated that the data were not normally distributed. However, as our sample was large enough (> 30), the distribution can be considered normal (central limit theorem; e.g., Kwak and Kim 2017), and ANOVAs are considered relatively robust against the normality assumption.

Additional analyses on effects of the given feedback are provided as a supplement to this article.

References

Alqassab, M., Strijbos, J.-W., & Ufer, S. (2018). Training peer-feedback skills on geometric construction tasks: role of domain knowledge and peer-feedback levels. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 33(1), 11–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-017-0342-0.

Andrade, H. G. (2001). The effects of instructional rubrics on learning to write. Current Issues in Education, 4(4).

Andrade, H. G. (2005). Teaching with rubrics: the good, the bad, and the ugly. College Teaching, 53(1), 27–31. https://doi.org/10.3200/CTCH.53.1.27-31.

Andrade, H. G. (2009). Students as the definitive source of formative assessment: academic self-assessment and the self-regulation of learning. In H. G. Andrade & G. J. Cizek (Eds.), Handbook of formative assessment (pp. 90–105). Routledge.

Baker, S., Gersten, R., & Scanlon, D. (2002). Procedural facilitators and cognitive strategies: Tools for unraveling the mysteries of comprehension and the writing process, and for providing meaningful access to the general curriculum. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 17(1), 65–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-5826.00032.

Ballantyne, R., Hughes, K., & Mylonas, A. (2002). Developing procedures for implementing peer assessment in large classes using an action research process. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 27(5), 427–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/0260293022000009302.

van den Berg, I., Admiraal, W., & Pilot, A. (2006). Design principles and outcomes of peer assessment in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 31(3), 341–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070600680836.

Brookhart, S. M. (2017). How to give effective feedback to your students. Ascd.

Bürgermeister, A., Glogger-Frey, I., & Saalbach, H. (2021). Supporting peer feedback on learning strategies: Effects on self-efficacy and feedback quality. Psychology Learning & Teaching, 20(3), 383–404. https://doi.org/10.1177/14757257211016604.

Dembo, M. H. (2001). Learning to teach is not enough—future teachers also need to learn how to learn. Teacher Education Quarterly, 28(4), 23–35.

Dignath, C., & Veenman, M. V. J. (2021). The role of direct strategy instruction and indirect activation of self-regulated learning—evidence from classroom observation studies. Educational Psychology Review, 33(2), 489–533. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09534-0.

Fiedler, K., Ackerman, R., & Scarampi, C. (2019). Metacognition: monitoring and controlling one’s own knowledge, reasoning and decisions. In R. J. Sternberg & J. Funke (Eds.), The psychology of human thougth: an introduction (pp. 89–111). Heidelberg University Publishing.

Glogger, I., Schwonke, R., Holzäpfel, L., Nückles, M., & Renkl, A. (2012). Learning strategies assessed by journal writing: Prediction of learning outcomes by quantity, quality, and combinations of learning strategies. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(2), 452–468. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026683.

Glogger, I., Holzäpfel, L., Kappich, J., Schwonke, R., Nückles, M., & Renkl, A. (2013). Development and evaluation of a computer-based learning environment for teachers: Assessment of learning strategies in learning journals. Education Research International, 2013, e785065. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/785065.

Glogger-Frey, I., Ampatziadis, Y., Ohst, A., & Renkl, A. (2018a). Future teachers’ knowledge about learning strategies: Misconcepts and knowledge-in-pieces. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 28, 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2018.02.001.

Glogger-Frey, I., Deutscher, M., & Renkl, A. (2018b). Student teachers’ prior knowledge as prerequisite to learn how to assess pupils’ learning strategies. Teaching and Teacher Education, 76, 227–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.01.012.

Glogger-Frey, I., Treier, A.-K., & Renkl, A. (2022). How preparation-for-learning with a worked versus an open inventing problem affect subsequent learning processes in pre-service teachers. Instructional Science, 50(3), 451–473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-022-09577-6.

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487.

Hausman, H., Myers, S. J., & Rhodes, M. G. (2021). Improving metacognition in the classroom. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 229(2), 89–103. https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000440.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. Guilford.

Heaysman, O., & Kramarski, B. (2022). Promoting teachers’ in-class SRL practices: effects of Authentic Interactive Dynamic Experiences (AIDE) based on simulations and video. Instructional Science, 50(6), 829–861. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-022-09598-1.

Herppich, S., Praetorius, A.-K., Förster, N., Glogger-Frey, I., Karst, K., Leutner, D., Behrmann, L., Böhmer, M., Ufer, S., Klug, J., Hetmanek, A., Ohle, A., Böhmer, I., Karing, C., Kaiser, J., & Südkamp, A. (2018). Teachers’ assessment competence: Integrating knowledge-, process-, and product-oriented approaches into a competence-oriented conceptual model. Teaching and Teacher Education, 76, 181–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.12.001.

Hübner, S., Nückles, M., & Renkl, A. (2010). Writing learning journals: Instructional support to overcome learning-strategy deficits. Learning and Instruction, 20(1), 18–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2008.12.001.

Huisman, B., Saab, N., van Driel, J., & van den Broek, P. (2018). Peer feedback on academic writing: undergraduate students’ peer feedback role, peer feedback perceptions and essay performance. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(6), 955–968. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1424318.

Huisman, B., Saab, N., van den Broek, P., & van Driel, J. (2019). The impact of formative peer feedback on higher education students’ academic writing: a meta-analysis. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 44(6), 863–880. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1545896.

Karlen, Y., Hertel, S., & Hirt, C. N. (2020). Teachers’ professional competences in self-regulated learning: an approach to integrate teachers’ competences as self-regulated learners and as agents of self-regulated learning in a holistic manner. Frontiers in Education. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2020.00159.

Karlen, Y., Hirt, C. N., Jud, J., Rosenthal, A., & Eberli, T. D. (2023). Teachers as learners and agents of self-regulated learning: the importance of different teachers competence aspects for promoting metacognition. Teaching and Teacher Education, 125, 104055. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2023.104055.

Kaufman, J. H., & Schunn, C. D. (2011). Students’ perceptions about peer assessment for writing: their origin and impact on revision work. Instructional Science, 39(3), 387–406. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-010-9133-6.

Kramarski, B., & Heaysman, O. (2021). A conceptual framework and a professional development model for supporting teachers’ “triple SRL–SRT processes” and promoting students’ academic outcomes. Educational Psychologist, 56(4), 298–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2021.1985502.

Kramarski, B., & Kohen, Z. (2017). Promoting preservice teachers’ dual self-regulation roles as learners and as teachers: effects of generic vs. specific prompts. Metacognition and Learning, 12(2), 157–191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-016-9164-8.

Kwak, S. G., & Kim, J. H. (2017). Central limit theorem: the cornerstone of modern statistics. Korean Journal of Anesthesiology, 70(2), 144–156. https://doi.org/10.4097/kjae.2017.70.2.144.

Lawson, M. J., Vosniadou, S., Van Deur, P., Wyra, M., & Jeffries, D. (2019). Teachers’ and students’ belief systems about the self-regulation of learning. Educational Psychology Review, 31(1), 223–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-018-9453-7.

Li, H., Xiong, Y., Hunter, C. V., Guo, X., & Tywoniw, R. (2020). Does peer assessment promote student learning? A meta-analysis. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(2), 193–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1620679.

Mayer, R. E., & Clark, R. (2001). The promise of educational psychology: teaching for meaningful learning. Vol. 2. https://doi.org/10.1002/pfi.4930420410.

Metcalfe, J. (2009). Metacognitive judgments and control of study. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(3), 159–163. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01628.x.

Nückles, M., Schwonke, R., Berthold, K., & Renkl, A. (2004). The use of public learning diaries in blended learning. Journal of Educational Media, 29(1), 49–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/1358165042000186271.

Nückles, M., Renkl, A., & Fries, S. (2005). Wechselseitiges Kommentieren und Bewerten von Lernprotokollen in einem Blended Learning Arrangement. Unterrichtswissenschaft, 33(3), 227–243.

Nückles, M., Hübner, S., Dümer, S., & Renkl, A. (2010). Expertise reversal effects in writing-to-learn. Instructional Science, 38(3), 237–258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-009-9106-9.

Nückles, M., Roelle, J., Glogger-Frey, I., Waldeyer, J., & Renkl, A. (2020). The self-regulation-view in writing-to-learn: Using journal writing to optimize cognitive load in self-regulated learning. Educational Psychology Review, 32(4), 1089–1126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09541-1.

Panadero, E., & Jonsson, A. (2013). The use of scoring rubrics for formative assessment purposes revisited: a review. Educational Research Review, 9, 129–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2013.01.002.

Pieper, M., Roelle, J., vom Hofe, R., Salle, A., & Berthold, K. (2021). Feedback in reflective journals fosters reflection skills of student teachers. Psychology Learning & Teaching, 20(1), 107–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475725720966190.

Porter, A. N., & Peters-Burton, E. E. (2021). Investigating teacher development of self-regulated learning skills in secondary science students. Teaching and Teacher Education, 105, 103403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103403.

Reddy, Y. M., & Andrade, H. G. (2010). A review of rubric use in higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(4), 435–448. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930902862859.

Roelle, J., Berthold, K., & Fries, S. (2011). Effects of feedback on learning strategies in learning journals: learner-expertise matters. International Journal of Cyber Behavior, Psychology and Learning, 1(2), 16–30. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijcbpl.2011040102.

Roelle, J., Nowitzki, C., & Berthold, K. (2017). Do cognitive and metacognitive processes set the stage for each other? Learning and Instruction, 50, 54–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.11.009.

Scardamalia, M., Bereiter, C., & Steinbach, R. (1984). Teachability of reflective processes in written composition. Cognitive Science, 8(2), 173–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0364-0213(84)80016-6.

Seroussi, D.-E., Sharon, R., Peled, Y., & Yaffe, Y. (2019). Reflections on peer feedback in disciplinary courses as a tool in pre-service teacher training. Cambridge Journal of Education, 49(5), 655–671. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2019.1581134.

Shute, V. J. (2008). Focus on formative feedback. Review of Educational Research, 78(1), 153–189. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654307313795.

Sweller, J., Ayres, P., & Kalyuga, S. (2011). The guidance fading effect. In J. Sweller, P. Ayres & S. Kalyuga (Eds.), Cognitive load theory (pp. 171–182). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-8126-4_13.

Zimmerman, B. J. (2002). Becoming a self-regulated learner: an overview. Theory into Practice, 41(2), 64–70. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4102_2.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zeeb, H., Bürgermeister, A., Saalbach, H. et al. Effects of a digital support tool on student teachers’ knowledge about, assessment of, and feedback on self-regulated learning. Unterrichtswiss 52, 93–115 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42010-023-00184-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42010-023-00184-z

Keywords

- Self-regulated learning

- Learning strategies

- Journal writing

- Peer feedback

- Teacher education

- Assessment skills