Abstract

Gender equity in education is an essential UN sustainable development goal. However, it is unclear what aspects of gender are important to consider in regard to research outcomes as well as how findings can be interpreted in the context of gender stereotypes and bias. This lack of clarity is particularly salient in the STEM field. Computer-supported collaborative learning (CSCL) is a group learning method where learners work together on group tasks that aim at the sharing and co-construction of knowledge. Aside from the cognitive learning gains, the literature reports that CSCL can bring social and psychological benefits, such as fostering positive mutual relationships and increased understanding of equity and diversity. In order to elaborate on the assumed potential of CSCL to support equity and diversity goals in education, this systematic literature will focus on the role of gender in CSCL. Although gender issues in CSCL have been examined before, a comprehensive overview is still lacking. Based on the PRISMA method, the current systematic review considers 27 articles, and explores (1) how gender is addressed, (2) what findings concerning gender are reported, and (3) the potential of CSCL to create more gender inclusive learning contributing to the UN SDGs. Our findings show that most studies addressed gender as a binary predictor for participation, communication, or attitude. Less than half of the studies treated gender more nuanced by defining gender as a social construct. This review highlights the need for additional research on the role of gender in CSCL, alongside more methodologies that can account for the complexities this entails. It is estimated that there is some potential for CSCL to decrease gender stereotypes and gender bias in STEM education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

1.1 Eliciting the role of gender in STEM education & research

Psychological and sociological theories within educational research acknowledge how learning outcomes on the individual or group level are also interrelated with their greater social contexts, such as classroom culture or pedagogic policies and norms in the school, the educational field, and society—especially in regard to gender (Fenstermaker and West 2009; Abbiss 2008). According to the European Commission (2019), it is a central goal of the EU to promote research into gender issues, facilitate gender equality, and question gender stereotypes in order to make gender-related research outcomes more effective and powerful in explaining the distinct needs of girls or women and boys or men. In terms of operationalizing gender in research, many social science studies differentiate between sex and gender in order to distinguish biological determinants from socio-cultural constructions, the latter being seen as more informative and central for many social science research contexts (Fenstermaker and West 2009). Some scholars elaborate on how the notion of sex and gender interact and influence culture, society, and also research approaches (Butler 2004; Lindqvist et al. 2021).

Over the past decades, social-constructivists have supported the theoretical stance that the individual’s participation in the production of gender is more in focus with the result that gender differences are understood neither as “natural” or essential nor as a simple result of socialisation conditions, but rather as an active expression, hence the term “doing gender” (Butler 2004; West and Zimmerman 1887). The concept of “doing gender” makes clear that gender identities result from the practices of representation and attribution of the subjects. In social interactions, they represent themselves as “male” or “female” or experience attributions from their interaction partners as either “male” or “female,” or, for instance, as “inter” or “trans,” which is usually harder to do, since the interactions in which identities are represented and ascribed are always characterised by power and inequality, and the dichotomous gender regime marginalises others. In the operationalization of research regarding gender and gendered differences, Lindqvist et al. (2021) therefore suggest addressing gender not as a fixed category but as a socially and historically dependent expression of embodied societal norms that are individual and collective expressions (emphasis by authors). Researchers have to critically choose the questions they ask regarding gender to not implicitly reproduce gender bias, i.e., gender stereotypes in research that are prevalent in most of society. Rather than a fixed dichotomous predictor, gender can be better explained with either a) physiological, b) identity-related, c) legal, or d) behavioural factors. Researchers have to formulate questions that describe their specific research interest in gender. Lindqvist et al. (2021) state for instance, when they are interested if the participants menstruate, it concerns the physiological or biological gender of a person; when they are interested in social identities online or offline, it concerns gender identity; when they are interested in the influence of the gender assigned at birth on the experience of transgender students, it concerns the legal gender; when they are interested in specific gender expressions in social learning scenarios such as CSCL, it concerns the behaviour of and among genders. Hence, the creation of male and female categories automatically establishes binaries. It artificially reduces manifold social expressions of gender that could be relevant to understanding social learning and instead reproduces stereotypical gender norms in research, argue socio-constructivist scholars (West and Zimmerman 1887; Lindqvist et al. 2021).

Social scientists such as Abbiss (2008), who engage in the theoretical discussion about gender in ICT learning, therefore identify two strains of concepts of gender: If researchers choose to look at gender as a binary predictor of behaviour and perception, related to the learner’s biological gender, it is the “liberalist” stance. It builds on the underlying assumptions that there are no power relations between genders in society, i.e., that men, women, and other genders are equal in all fields of society. Differences in behaviour and perceptions of different genders in learning are therefore insulated and independent social observations. The opposing one is the “constructivist” stance (ibid.). It understands gender as a fluid, multifaceted social construct. It builds on the assumption that gender is always related to the social and cultural context, i.e., the power relations of genders in society and the learning environment at the time, which Mahoney (2001) translated into gender/technology and power/knowledge relations.

Gender power relations are especially relevant to focus on, argues Mahoney (2001), in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education. As many scholars state, there is a persistent gender gap in STEM, which is pictured as a “leaky pipeline” (Charlesworth and Banaji 2019). Although many girls start STEM education and might even be high-achieving students, few women enter and remain in STEM careers (Perez-Felkner et al. 2014). Thus, minority-majority power relations need to be considered in understanding women’s learning experience in STEM environments.

The theoretical discourse in social science about the conceptual specifications of gender is interesting to consider transferring to the research field of CSCL, where such academic discourse is not mainstream yet (cf. Ames and Burrell 2017). We posit that this topic may find fertile ground in the CSCL community, as this has traditionally been an interdisciplinary and heterogeneous research field, recognizing and integrating a multitude of epistemological stances (Stahl et al. 2006; Stahl and Hakkarainen 2021). Understanding the definition of gender and how it is addressed and operationalized in CSCL could bring about new knowledge on the role of gender in online social group learning.

1.2 CSCL & inclusive (STEM) education

Computer-supported collaborative learning (CSCL) is a technology-supported learning scenario that has received ample academic attention over the past decades due to its potential to enhance student learning and further pedagogical advantages beyond individual knowledge acquisition. As a research field, CSCL investigates the positive interdependence, socio-cognitive conflict, resource sharing, and verbalising thoughts in the learning process of small groups of collaborating learners (Dillenbourg 1999; Cress et al. 2021). Concerning the composition of the learning scenario in education, several applications of technologies are summed up under the term CSCL. One element they all share is student collaboration in a designated digital learning environment in which knowledge is constructed collaboratively and with a common shared goal, e.g., solving an ill-structured problem (Kirschner and Erkens 2013). Although this kind of group work may also support the development of social, cognitive, and online collaborative teamwork skills, CSCL is usually employed as an instructional method that facilitates knowledge construction through social interaction (ibid.). Studies demonstrate that the collaborative learning knowledge-building process enhances student learning by leveraging interactions through discourse, response pairs, group moves, and problem-solving themes (Stahl et al. 2006). CSCL research can ‘view’ how a small group evolves to solve a problem, identify the social and social-emotional aspects underlying the group dynamics, and contemplate how current technologies further support these learning processes (Kirschner et al. 2015).

The CSCL literature documents three different socio-habitual forms of investigating gender differences. The most prominent form pertains to differences in the participation of boys and girls in CSCL learning (Palonen and Hakkarainen 2000). Prinsen et al. (2007) elaborated on the gender differences in CSCL participation in an initial literature review of thirteen studies; however, they included papers on computer-mediated communication (CMC) in their analysis. Others have looked at gender differences in communication behaviour in CSCL learning environments (Tomai et al. 2014; Koulouri et al. 2017), and, lastly, gender differences in attitudes towards ICT and computer-supported collaborative learning (Zhan et al. 2015). Just as in the traditional classroom, the learning performance of mixed-gender teams in online spaces depends on the quality of interpersonal interactions in both collaborative settings (Chennabathni and Rejskind 1998; Curşeu et al. 2018; Hennessy Elliott 2020).

It is important to note that with respect to interpersonal interactions, we have to take into account that there are significant differences between interpersonal interactions online and offline, the most fundamental difference being the increased psychological distance in CSCL compared to face-to-face communication (Kreijns et al. in press). Social and psychological differences can result in more confusion or misunderstanding, less productiveness, less cohesion, and less satisfaction in online group work compared to its analogous counterpart (Järvelä et al. 2015). Further, studies in ICT learning are arguing that these differences could be aggravated by the fact that online environments facilitate gender-stereotyped ways of interactions, which negatively affect girls’ participation (Prinsen et al. 2007; Richard and Hoadley 2015). Power dynamics and gender-stereotyped communication styles carry over from face-to-face into online environments, including social cues that are also present in the written language, such as complimenting women for not being bad at maths. They would then be expressions of prevalent implicit gender bias in collaborative online learning communities (Battista and Wright 2020).

Other scholars find that the extent to and the way in which gender-related attitudes, communication styles, and preferences are enacted in CSCL also depends on the domain and the character of the educational technologies used and varies with gender group constellations (Curşeu et al. 2018).

Nonetheless, CSCL could also provide a solution for gender-inclusive learning. The main benefit of CSCL noted by literature is that it yields positive cognitive and psychological effects on learners and that mutual relationships can be strengthened in online group learning (Kirschner and Erkens 2013; Chen et al. 2018). Since Prinsen et al. (2007) conclude their first review on gender in CSCL with the outlook that it might be possible that implicit gender bias can be overcome by addressing gender equity and inclusiveness in CSCL, we would like to understand whether and how CSCL can be an effective mediator of exclusive behaviour and gender stereotypes in online collaboration.

As a first step, we need to understand the role of gender in CSCL research and online social group learning. This review aims to focus the attention of the field on the importance of reflecting on gender in CSCL research and provides an overview of the literature as well as research gaps. The following research questions guide our work:

RQ1

How is gender addressed, defined, and operationalized in studies in CSCL?

RQ2

What are the empirical findings regarding gender and gender difference in CSCL?

RQ3

In which learning contexts was gender and gender difference investigated in CSCL?

RQ4

What is the estimated potential of CSCL in alleviating gender differences and gender bias in education?

After elaborating on the method of this systematic review, the results will be documented in the analysis and discussed afterward, followed by the review’s conclusions.

2 Method

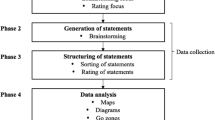

To answer the research questions, we performed a systematic review following the PRISMA methodology (Moher et al. 2009). To this end, suitable studies were extracted from three electronic databases, ScienceDirect (Elsevier), SAGE, and SpringerLink, and the comprehensive AI technology of the MIT project semantic scholar (semantic scholar.org*).

In the identification phase, we used the following search query using keywords highlighted in research in gender studies and CSCL: (Computer-supported OR “Online Collaborative Learning” OR “Computer-supported learning” OR CSCL) AND (Gender OR “Gender Bias” OR Stereotype OR Discrimination OR Inclusion) AND Education. Discrimination and Stereotype as further search terms were chosen based on the relevant literature suggesting the relatedness of gender, gender bias, and discrimination (Kelan 2009). We observed that using the keyword E‑Learning delivered fewer results, so we removed it from our search query. From our original search results (= 1353), we removed duplicates (n = 383) and studies that were no recent CSCL studies (2005–2021) or not written in English (n = 228).

Fig. 1 illustrates the different steps at which the articles were screened following the PRISMA methodology (Moher et al. 2009).

Next, the records (n = 741) were screened manually by looking at the title, abstract, keywords, and research questions of the studies for relevance. We further excluded studies that were only related to e‑learning or distance learning but not strictly to CSCL. In total, 638 studies were thereafter excluded. Subsequently, we examined sixty-eight studies, where six were omitted due to being literature reviews, poster presentations, or conference papers shorter than three pages. We read the sixty-two full texts during the last step of the screening phase and thoroughly evaluated them. In this last screening step, thirty-five studies were further excluded due to the lack of focus on gender and the mentioning of gender as a by-product of study outcomes, insufficiently elaborated as a concept. Finally, we only included studies that specifically addressed gender or gender difference in CSCL as the main topic mentioned in the title, abstract or keywords, or explicit research question. No restriction was placed in terms of discipline or the methodology apart from being empirical. The last phase of the literature review involved the analysis of the remaining twenty-seven articles.

Our coding strategy for the remaining CSCL studies was as follows. We looked at the main research focus and related descriptive paragraphs to understand the theoretical and conceptual approaches to gender research. Employing a grounded theory approach to analyse the research approaches in these CSCL studies, we classified them according to the two conceptual strains identified in the theoretical ICT learning discourse (see Abbiss 2008): liberal or (post-) constructivist. We also classified the main research focus described in the paper in terms of the three different socio-habitual forms of investigating gender differences in the CSCL literature: focussing on the interaction behaviour in CSCL (Behaviour); and/or the communication among collaborating team members (Dialogue); and/or the students’ perceptions of gender in CSCL (Perception), (cf. Prinsen et al. 2007).

The following information was additionally extracted from the papers: year of publication, authors, country, design, participants, the discipline of the researchers conducting the study, and the study field of students participating in the CSCL task. The list of papers included in this review is available in Appendix, Table 3. The results of the analysis are presented in the following section.

3 Results

This chapter will first offer an overview of the CSCL research designs and contexts of the studies included in this systematic literature review. We will then continue by documenting the research topics related to gender and the underlying theoretical understanding and operationalisation of gender (RQ1), see 3.1, Conceptualisations of Gender. Next, the empirical findings regarding gender in CSCL studies will be presented (RQ2, see 3.2), Empirical Findings, and thereafter, the Learning Contexts (RQ3, see 3.3). Lastly, the information regarding the potential of CSCL to alleviate gender difference and gender bias in education will be compiled from the findings of the included papers (RQ4), see 3.4 CSCL & Gender Equality.

The number of participants in the 27 selected studies varied considerably, especially in the quantitative studies, with between 40 and 1131 participants. Most of the papers were published after 2015 (n = 18), when the UN had launched the new global Sustainable Development Goals 2030 and set gender in the spotlight of public and academic attention. More than one-third of the studies (n = 11) were from the United States, and four came from the Netherlands, two from Israel, the remaining ones were from the UK, Australia, Argentina, Germany, Belgium, Italy, Spain, Romania, South Africa, China, and the United Arab Emirates. Regarding the scientific discipline, by far the most (n = 13) papers reported studies conducted by researchers from the field of social and educational sciences; eight came from computer science, three from psychology, two from ethnography, one from social work, and one from literature studies. As to the educational setting, most studies took place in a higher education institution (n = 15) or high or middle school settings (n = 10); one study concerned more minors, and two from adult and other contexts.

The group size and duration of the CSCL task, if mentioned, significantly varied. Six studies took place in pairs (mixed-gender compared to single-gender dyads), four studies in groups of 3–4, two in groups of 2–3, and three other studies with groups larger than three members but not more than seven. Also, the duration of the studies varied from 90 mins, four school lessons, 40 h, 14 days to “several weeks,” two–3 months, or one university semester (see Appendix, Table 3). The CSCL tasks were mostly remote educational group settings with synchronous and or asynchronous tasks, sometimes MOOCs via Moodle or google teams or another school or university-specific platform (n = 20). Except for three studies in social work, literature, and psychology, twenty-four studies took place in STEM curricula, some specifically concerned (coding) games (n = 4) and robotics (n = 2), STEM problem-based learning (n = 2), and one study examined special CSCL in hackathons.

3.1 Conceptualisations of gender in CSCL

After analysing the studies included in this review through the lens of the two theoretical strands identified in the discourse of ICT learning explained earlier (Abbiss 2008), the following methodological implications were found. All studies building their research design on a liberalist perspective on gender, i.e., based their definition of gender on an assumption of dichotomous gender differences instead associated with the sex or biological gender of the learners than their social gender identity or expression, employed quantitative methods (n = 15). In the research design, they treated gender as a fixed, dichotomous variable, used to predict differences between boys and girls. Gender was frequently (n = 9) not further contextualised. For example, Zhan et al. (2015) used gender as an individual difference variable hypothesised to influence individual group members’ learning experience and performance. In complex social processes such as group learning with individuals that arguably have more social markers than their biological gender, this implied an artificial reduction of complexity to uphold the explanatory strength of the research design and statistical analysis. This needed to be done in order to be able to identify patterns of communication, choice, and, most of all, interaction behaviour in CSCL. However, it neglects a more refined perspective on gender or social interdependencies and context.

On the contrary, studies building on a (post-) constructivist perspective on gender employed primarily qualitative (n = 7) and mixed methods (n = 5) in their research designs. They treated gender as a social construct and tried to shed light on inter-social dependencies and definitions of gender in the specific learning contexts. (See specifics in Fig. 2).

We found that not all studies (n = 9) elaborated on their conceptual definitions of gender. However, the concepts of gender discussed in the remaining studies (n = 18) can be clustered by their research topics: Studies concerning behaviour (n = 10) in CSCL either elaborated on collaboration and interaction behaviour, motivation, digital competence, or “femaleness” of behaviour from a liberal gender perspective (n = 4) or based on the theoretical counterpart, they elaborated on gender-stereotypes in behaviour (n = 6). Research looking into gender differences in communication, i.e., concepts of dialogue (n = 4), either took a liberalist stance to look at female communication patterns (n = 2) or employed a (post-) constructivist understanding of gender and communication in order to decode also (counter-) stereotypical communication patterns of women and men in CSCL. The latter is noteworthy since constructivist papers declared that gender is a mutual social construct of female and male properties, not referring only to women “as the other gender” and men as the neutral gender, which is in line with the arguments of recent discussions of gender scholars (Lindqvist et al. 2021). Interestingly, (post-) constructivist approaches defined gender as interdependent with individual and group Perception and Social Positioning in CSCL (n = 6). To show the relatedness of gender experience in learning with the social, cultural, ethnic, and socio-economic background of the group members is a so-called intersectional understanding of gender that elicits the nuances of power relations, social inclusion, and exclusion in group scenarios. Based on that understanding, these studies elaborated on social processes in learning or gaming and hacking culture (n = 2). Normative concepts of equity (n = 2), inclusion (n = 2), safety (n = 1), and leadership (n = 2) were referred to in their conceptualizations of gender in technology-supported learning contexts.

In conclusion, gender as a concept was either used as a tool to describe and predict gendered patterns of behaviour in CSCL, i.e., in a liberal research approach or, it was used to understand how social and psychological aspects of gender and their context interfered with CSCL behaviour and communication, i.e., in a constructivist research approach.

3.2 Empirical findings

Looking at empirical findings, the role of gender in CSCL depended on the research aim of the studies. Numerous (n = 11) studies supported the proposition that gender group constellations are a robust predictor of group learning performance and success (see row 1.1 in Table 1). These papers assessed the performance and success of CSCL experiments, paying attention to participants’ behaviour in single- or mixed-gender groups comparatively. For instance, a quantitative study by Cen et al. (2016) employed a predictive mathematical model equipped with supervised machine learning to assess group and individual performance in real-time, analysing various data sources of university students working in a Moodle environment, where a collection of tools enabled communication, information sharing and collaborative document creation on one platform. They found a high level of predictability of group performance based solely on the style and mechanics of collaboration and support the claim that heterogeneous groups with diverse skills and genders benefit more from collaborative learning than homogeneous groups. Zheng and Pinkwart’s (2014) and Zhan et al.’s (2015) studies employing similar technologies support this. Gnesdilow et al. (2013) and Ding et al. (2011) follow these lines of argumentation, providing examples of school children in a physics learning computer game for groups in the classroom where students in mixed-gender groups performed significantly better than students in same-gender groups. In these studies, having at least one group member of the opposite gender increased individual students’ post-test performance. Others, however, found contradicting results for CSCL in physics school education (Harskamp et al. 2008). Taylor and Baek (2019) also do not find group composition explaining group performance. Assessing preschool children who played with LEGO Mindstorms EV3 robotics over weeks in class, they found the gender composition of the group inconsequential for group performance in building a robot. It was rather the division of group roles and tasks between the genders that impacted the individual development of computational thinking skills. Research on the preference of what group roles women or men take on in a CSCL setting at university found no gender difference in the role preferences in mixed-gender groups, nor was the level of participation different between the genders analysing the interactions in a Moodle environment (Costaguta et al. 2019). So, in these studies, gender was a predictor of team performance, however, with contradictory results.

Another set of studies (n = 16) attempted to understand the overall mixed-gender group performance or individual performance in CSCL by assessing behaviour and communication (see row 1.2 in Table 1). Lin et al. (2019) found in the analysis of university students’ communication in an online synchronous collaboration that the degree of participation was not different between men and women. “However, women exhibited significantly higher average social impact, responsibility, and internal cohesion compared (…) to men. We also compared the proportion of learner’s interaction profiles, and results suggest that women are more likely to be effective and cohesive communicators” (Lin et al. 2019, p. 434). In a comparable technical setting, Chiru et al. (2013) found that women were more innovative in CSCL chat conversation, and more gender diverse teams performed better. Rambe (2017) argues along the line, but with other outcomes. In his study of a South African university asynchronous group work in a google docs experiment, he found that the success of collaborative learning depended on overcoming asymmetric gender participation and leaders’ dominance. He added the observation of micro-aggressions. When online conversation included gendered and racialized discriminatory expressions, the participation of individual white and black women and black men in diverse groups in CSCL decreased greatly. Others found that gender bias in communication can be alleviated in online asynchronous group work at university. According to Tomai et al. (2014), counter-stereotypical communication, of either task-oriented “stereotypical male” or emotional cohesion “stereotypical female” oriented communication, was found in both all-male and all-female teams. They found that CSCL in small groups with asynchronous communication has the ability to promote counter-stereotypical communication patterns. However, only looking at all-male and all-female teams.

When it comes to the relation between communication behaviour and specific technical aspects of CSCL, Reychav and McHaney (2017) found that involving video material in an online group learning task in class while working on tablets increased the interaction of women. Based on socialisation theory, they argue that men were more amenable to text-based materials and placed less value on connections and interaction, and therefore less likely cooperative communication styles in learning than women. These effects are supported by Koulouri et al. (2017), who analysed team performance in a simultaneous navigation group task at a university, with and without visual feedback online. While no performance variance was found between men and women, the behaviour differed: “Males had a strong tendency to introduce novel vocabulary when communication problems occurred during the navigation, while females did not change their communication strategy. When visual feedback was removed, however, females adapted their strategies drastically and effectively, increasing the quality and specificity of the verbal interaction, repeating and re-using vocabulary, while the behaviour of males remained consistent” (Koulouri et al. 2017, p. 43 f.).

Richard and Giri (2017) find that inclusive, collaborative practice is possible in simultaneous and hybrid digital and physical CSCL settings. They found these conditions crucial for individual participation behaviour and the learning success of collaborative groups of marginalised or minority group students. In a high school maker space experiment with simultaneous and digital and physical responsive computer game design projects, they found that interactive tasks with students learning how to program in person and collaboratively showed significant promise for fostering inclusive, collaborative practice and understanding for each other: “It is helping learners better appreciate the creative, diverse and meaningful ways computing could be used in their lives, as well as, encourage computing identity and self-efficacy in the group but also the individual,” (Richard and Giri 2017, p. 421). Di Lauro (2020) supports the argument that simultaneous hybrid tasks of CSCL can be meaningful for creating inclusive learning experiences. She also found that the content of the CSCL task can be supportive. Her unique form of CSCL with university students, an edit-a-thons of Wikipedia adding female scholar entries created more visibility for female role models in history as a means to delimit homogeneity of network knowledge on a greater scale.

Regarding the gender differences in motivation and attitudes in synchronous CSCL tasks, Raes et al. (2010) found that CSCL is beneficial for girls and effective for science learning since they had a more positive perception of computer-supported learning than boys, which led to better performance over time. Asterhan et al. (2011) supported the latter, however, comparing only all-male and all-female teams. Buffum et al. (2016) found that school children’s attitudes and perceptions toward game-based CSCL are positive among boys and girls, regardless of their prior knowledge or exposure to technology. They found that girls with no experience made significant gains in learning in a short period of time. Huynh et al. (2005) and Ying et al.’s (2021) study had different results in this regard. When researching the motivation of mixed-gender CSCL pairs, they found women to report significantly higher stress levels, lower levels of perceived competence, and less perceived choice than men. However, they worked with adult students in higher education in computer science.

3.3 Learning contexts

Notably, most CSCL studies (n = 24) included in this review took place in STEM learning contexts. Only three CSCL studies took place in seminars on social work, psychology, and literature studies at the university. The STEM studies were carried out in different settings ranging from preschool to university student CSCL. The findings regarding gender varied greatly, from age group, social context, school subject, and the technology worked with, making them hardly comparable.

Notwithstanding, among the STEM were studies with findings that were directly related to the computer science context, especially when negative effects in the learning process and results for women were documented. Ying et al. (2021) found that perceived stress, alienation, and distance can be visible in women’s participation and dialogue patterns in simultaneous remote CSCL in university. They reasoned that in a STEM field such as computer science, where women have been historically underrepresented, their gender could be an early predictor of collaborative experience. Also, Richard and Hoadley (2015) reported the need for female- and minority-friendly communities in their study on educational or leisure time gaming environments. Analysing the collaborative learning in coding and gaming, they found that female-friendly communities can support girls in gaming and help protect girls and other minorities from exclusive and discriminatory practices in homogenous male-dominated gaming environments and cultures. Richterich (2019) supports the argument in her ethnographic study on university hackathons. She discovered that CSCL hackathon formats in computer science reproduced gender-stereotypical work divisions, where women were designing, and men were coding. Also, the fact that women were a minority group at all hackathon events strongly defined the hacking culture and learning atmosphere with clear majority-minority relations making the women present invisible in the male-dominated culture.

Six studies reported further implications for STEM CSCL regarding gender and/or other social markers, such as ethnicity, culture, and social class, in the minority-majority relations in learning environments. Hennessy Elliott (2020) documented gender-stereotypical narratives about who can or cannot do activities in computer science in his ethnographic observation of a LatinX girl in a high school robotics team who was never put into the driver’s seat throughout the tasks by the white male majority in the team. Cintron et al. (2019) found that introductory computer science courses at universities lack inclusiveness. Their study demonstrated that students of women and minority groups were more motivated toward computer science. They found the course more relevant than non-minority students, but they perceived less support from teachers and instructors. Also, Ames and Burrell (2017) documented exclusionary practices in a CSCL gaming experiment with minority youth playing Minecraft, which is an online community that white middle-class boys dominate. They found that apart from gender, the fact that these girls and boys came from families with low socio-economic status separated them from the Minecraft community and impacted their learning results and experiences. The disadvantages due to a lack of language literacy, parental support, and access to computers hindered the equity aims of the connected learning tasks in CSCL. As a consequence, minority boys and girls equally felt misunderstood by the majority of players and resigned or misbehaved in the interactions out of defiance.

Thus, these studies (Cintron et al. 2019; Buffum et al. 2016; Hennessy Elliott 2020; Rambe 2017; Ames and Burrell 2017; Richard and Giri 2017) demonstrated that minority-majority relations play a specific role in computer-supported learning environments where one social group is dominant. They analysed the interrelation of privilege and discrimination based on the different social positions of the individuals from minorities in online social learning groups. They further gave some indications that the relation between technology and social position shaped the learning experience and participation of these boys and girls in the team and further pointed out that these effects may be even more crucial for girls from marginalised social groups.

3.4 CSCL & gender equality

Analysing the results section of the papers included in this review, in order to assess the estimated potentials of CSCL in alleviating gender bias and inequality, we found the following implications and solutions. Several studies (n = 7) attested CSCL the potential of exacerbating existing inequalities and social exclusion (see No. 1, Table 2).

Mainly, the studies about minorities in STEM education paying attention to the intersectional experience of women and girls belonging to social and political groups of marginalisation, stigmatisation, and disempowerment in learning and working spaces, where being white and male are the norm, found that there is little perspective for CSCL to alleviate minorities’ disadvantages with pedagogical interventions. These authors queried whether CSCL as pedagogical means is capable of addressing the digital divide, divisions of class, and ethnicity that shape (minority) girls’ reality appropriately in gaming or platforms as they are today (Ames and Burrell 2017; Hennessy Elliott 2020). Others find that the scope of unconscious gender bias in STEM education became clear when observing that higher female participation did not automatically reduce differential treatment and stereotyped perception of women in CSCL learning experiences (Rambe 2017; Ying et al. 2021). They further find that a deeply rooted gender bias still exists in the classroom today, and carries over to technology-supported learning environments in CSCL (Huynh et al. 2005; Cintron et al. 2019; Richterich 2019).

Nevertheless, according to the majority of the literature (n = 20), the research gave some evidence that CSCL can support gender inclusion and equity in education (See No. 2, Table 2). For instance, Lin et al. (2019) found counter-stereotypical participation and communication in CSCL. Even though they found an existing gender bias in classroom cultures, they proposed that CSCL could mitigate biases with an inclusive pedagogy course design and tasks that explicitly promote gender equity through inclusivity norms promoted in class and online communication and collaboration among teachers and students alike, which is also supported by Koulouri et al. (2017) and Raes et al. (2010). Other authors further argue that understanding the gender composition of teams and team performance could lead to strategic and easy-to-implement teaching decisions for enhancing collaboration and learning (Gnesdilow et al. 2013; Zheng and Pinkwart 2014; Cen et al. 2016; Zhan et al. 2015). Again others saw game-based learning, gender-equal representation in instructional material, and technological aspects such as employing various media types, and interactive task and rotating task divisions and responsibilities in hybrid or online collaboration, in both simultaneous and asynchronous settings, as drivers of inclusive practice since they would make CSCL attractive and accessible for all learners (Costaguta et al. 2019; Taylor and Baek 2019; Reychav and McHaney 2017; Tomai et al. 2014; Asterhan et al. 2011). According to Di Lauro (2020), individuals could be motivated by mass-collaborative events and empowerment of network knowledge based on feminist theory.

In summary, the reviewed literature pinpointed two main positive consequences of CSCL in this regard. First, fostering awareness of the problem (Di Lauro 2020; Sepulveda 2018), which would help to counteract gender stereotypes in STEM for all gender, and secondly, increasing self-identification and efficacy of girls and women in computer science (Richard and Hoadley 2015).

4 Discussion

In this paper, we investigated the state-of-the-art role of gender in CSCL according to four research questions. We will discuss our results in the following, highlighting the challenges and possible solutions for educators to design gender-inclusive CSCL environments with the proposed solutions in the included studies and related literature. Also, we will identify new methodological trajectories for CSCL researchers to support future research in the field.

4.1 Premises for gender in research methodologies

Concerning RQ1 (definition of gender in CSCL), we found that none of the papers included in this review elaborated on their definition of gender sufficiently to make a clear-cut distinction in methodology. Numerous studies in CSCL continued a strain of explanation that has been popular with scholars since the 1980s, i.e., “gendered difference of behaviour vs. doing gender,” thus treating gender as the biological sex, i.e., a fixed variable that is biologically and also socially determining learning results. This perspective neither views gender as a social construct continuously challenged and constructed bi-directionally by individually expressed identity nor accommodates social and political notions of gender in society and education. Recent debates of queer and feminist scholars and intersectional perspectives in social science and psychology have challenged this epistemological perception (Wilkinson 2014). Furthermore, since the early 1990s, the methodological approach in qualitative and quantitative studies on gender has changed (cf. Abbiss 2008).

In comparison, few researchers would argue that age is best measured with the two response categories ‘young’ and ‘old,’ but gender is still most often measured as a dichotomous variable (Lindqvist et al. 2021, p. 1).

To use a dichotomous variable for describing gender in CSCL is problematic for two reasons. First, given that gender is used to classify individuals and describe collaborative groups statistically, it is obfuscating to discuss the problem of gender bias and gender difference in the absence of a clear definition and frame of reference. It poses validity issues and limits the ability to describe and explain empirical outcomes related to gender. Second, adopting the dichotomous variable of male/female reinforces the discriminatory practice in society against individuals who do not identify as either men or women. The findings of the studies included in this review, for instance, do not mirror the experience and performance of learners who do identify as non-binary or genderqueer in learning environments, where other gender identities than “male” or “female” are marginalized. These populations have not been addressed in the studies at all. Focusing on the representation of Trans children, Wilkinson (2014) thus stresses the importance of avoiding “gender blindness” towards other forms of gender identities in educational research. In order to prevent their further misrepresentation in education, we need to reflect more deeply on the implications of CSCL for non-binary or genderqueer student populations, who are at risk for exclusion and marginalization by discriminatory practice that is persistent in society and classrooms. To achieve better representation in and accuracy of the research regarding the gender of learners, we need to operationalize gender in ways that capture its complexity and represent all individual experiences equally to understand empirical findings in CSCL better.

Rather than physical attributes or the legal gender, research about social processes of learning, learning experience, and success should concern gender identity and its perceptions and social expression in behaviour and communication in the classroom to be more accurate. Lindqvist et al.’s study (2021) gives some practical operational advice on what research interests and questions can be addressed with gender-related variables. Transferred to the research field of CSCL, potential future research on gender should employ the following methods:

-

Gender Identity: Since gender is a self-defined identity, which can be more or less fluid or change over time and context when collecting demographic information about the participants’ gender, researchers could use multiple-choice questions with additional response options that go beyond the female/male dichotomy (e.g., non-binary, other) or have a free-text response. The latter, of course, is causing several problems when processing the data and quantifying results. Therefore, Lindqvist et al. (2021) recommend reviewing the research question and explicitly elaborating what aspects of gender are relevant for the research interest. If participants’ gender identity is of interest (e.g., how they self-identify or if their identity experience mirrors the gender assigned at birth), the question should be formulated to ask participants about that explicitly. The authors also propose to use validated scales like the Multi-Gender Identity Questionnaire (Multi GIQ) or the Bem Sex-Role Inventory (BSRI). These could be useful to move beyond gender as a predictor for the formation of gendered impressions in behaviour and communication in online learning groups. The scales define femininity and masculinity as two independent dimensions. However, instead of measuring personality traits (BSRI), the Multi-GIQ items assess self-identification with femininity and masculinity on levels related to gender identity, gender expression, legal gender, and physical aspects.

-

Gender Expressions, i.e., the way in which a learner expresses their gender identity, typically embrace a range of feminine and masculine gender expressions in their communication and behaviour in their group in CSCL. These expressions vary individually and also depend on the social and cultural context. It is an important aspect to better understand the role of gender in social learning environments such as CSCL. Lindqvist et al. advise: “When it is of interest to assess participants’ gender expression, a simple way is to ask the participants about how feminine and masculine they see themselves, and how feminine and masculine they believe others see them. Importantly, all participants regardless of their gender identity should respond to both the questions about femininity and masculinity, to account for individual diversity.” (Lindqvist et al. 2021, p. 9). Another proposal is to ask how important identifying with one’s gender is by using an adapted version of Luhtanen and Crocker’s (1992) Collective Self-Esteem Scale (CSES). This scale measures the importance of identification with a social group that defines social identity.

In conclusion, future research in CSCL may explore how notions of gender interact with other social and psychological factors, e.g., individual and collective self-esteem and sense of belonging in CSCL. Research could elaborate on what behavioural outcomes or perceptions can be explained with the help of these factors to describe and represent the needs of all genders and social positions in online and offline collaborative learning.

4.2 Findings of gender-Inclusive solutions for CSCL in education

Regarding RQ2 (findings regarding gender and gender difference in CSCL), we learned that empirical results about gender and gender differences in CSCL were ambiguous and context-dependent. However, there were some interesting patterns of reasoning that were identifiable.

The majority of the studies found diversity and mixed-gender teams as a crucial support and successful method for achieving different cognitive, social, and meta-social goals in group learning (Koulouri et al. 2017; Raes et al. 2010; Gnesdilow et al. 2013; Zheng and Pinkwart 2014; Cen et al. 2016; Zhan et al. 2015). Nevertheless, some studies concerning minority girls and youth from families with low socio-economic status demonstrated how poverty constrains access to equal participation in education employing education technologies (Cintron et al. 2019; Buffum et al. 2016; Hennessy Elliott 2020; Rambe 2017; Ames and Burrell 2017; Richard and Giri 2017).

Looking more closely at the specific contexts and technologies used in CSCL tasks, it appeared that for groups of learners, especially in high school settings, there was a tendency that simultaneous in-class settings were the best fitting. The more heterogeneous in terms of social markers such as gender, cultural background, and socio-economic status the groups were, which also reflected in their exposure to technology and experience as well as belonging to a minority in the computer-supported learning environment, the more pedagogical assistance was needed for the teams to succeed (Chiru et al. 2013; Rambe 2017; Ames and Burrell 2017; Lin et al. 2019). Especially interesting were the findings regarding the use of technology in CSCL there: Most inclusive where hybrid learning scenarios in class with simultaneous tasks, where the teachers could intervene and assist in preventing exclusionary practice at any moment and enhancing gender-equal and inclusive classroom culture and learning environments throughout the CSCL (Reychav and McHaney 2017; Richard and Giri 2017). There were some indications that asynchronous remote online tasks appeared to be the best fitting for relatively homogenous groups of experienced learners at the university. They were increasing perceived stress and social conflicts in ethnically and gender diverse teams in computer science learning, i.e., an environment that was dominated by one male group increased the gender stereotype thread and supported exclusive behaviour (Rambe 2017; Ying et al. 2021).

Although some authors doubted that CSCL could help to overcome gender stereotypes and inequalities such as the digital divide in learners’ access to technology, the majority of the authors included in this review saw the potential of CSCL to challenge the status quo and offer the solutions for more equity and inclusion in CSCL.

-

On the societal level, inclusive education and gender equity norms need to be more strongly promoted and more present, especially in STEM fields and ICT. Regarding gender, society should invest more in women and their education to achieve equity; otherwise, non-inclusive environments like computer science hackathons and gender-stereotypical behaviour remain the same (Richterich 2019).

-

Others focus on technical solutions for more gender-inclusive CSCL designs and the use of different media sources and gender-mainstreaming in technological software development (Huynh et al. 2005; Cintron et al. 2019). More specifically, some opted for the employment of a variety of media resources and types of user interfaces and communication channels, which would apply to the preferences of women (Reychav and McHaney 2017; Koulouri et al. 2017; Ying et al. 2021). Others hypothesise that unless ICT design decisions are not driven by diversity- or gender-inclusive focused aims, systems are destined to include features that may be superfluous or even obstructive to particular groups of learners (Ames and Burrell 2017). If systems were designed as open for redesigning and development due to feedback from diverse learners, it could create more gender-equal inclusive technologies. Hence, they “are theoretically value-free, but fail to recognize the ways they may be implicitly exclusionary” (Richard and Giri 2017, p. 416).

-

The third group of authors sees pedagogical solutions as crucial for gender inclusivity in CSCL. They argue that CSCL tasks need to be more responsive, interactive, and creative (Richard and Hoadley 2015). Educators need to employ gender-sensitive communication strategies and educational materials (Ames and Burrell 2017). They also should establish social leadership in the classroom and supportive teaching strategies to include girls and other minorities in CSCL (Hennessy Elliott 2020; Rambe 2017). Tasks should be designed with rotating responsibilities in order to avoid gender-stereotypical work divisions and behaviour (Taylor and Baek 2019; Costaguta et al. 2019). In addition, the representation of women and other minorities in STEM is a critical instrument to CSCL inclusiveness (Richard and Giri 2017). More diverse learners and their diverse mentors would be able to empower girls and minorities in CSCL, nurturing equitable participation, which cannot be enforced by the design of technologies alone.

4.3 Representation matters in STEM science & research

Concerning RQ3 (specific learning contexts of CSCL), it was peculiar that most studies took place in STEM and computer science education. There may be two reasons why gender is of particular interest for explaining social learning and group behaviour in STEM education. Obviously, the practical implication is that the CSCL technology is often developed by ICT-related research departments researching this topic. Consequently, they also test these technologies with their students, STEM students. Nevertheless, and according to research on the homophily of social collaboration, another reason is that “similarity breeds connection” (Kwiek and Roszka 2021). Men like to work and network with men in male-dominated fields such as STEM. Consequently, personal networks are homogeneous concerning many socio-demographic and personal characteristics such as age, ethnicity, class, wealth, education, and gender. Thus, women are at a disadvantage in making connections and building meaningful work relationships in these fields (ibid.). Gender is essential for the collaboration experience in a learning context, where women are disproportionately misrepresented, i.e., in STEM and computer science (Ying et al. 2021). The literature shows that the learning experiences of girls and women are shaped by both prevalent gender stereotypes in STEM and the lack of role models to identify with in the field. The misrepresentation of women in the field consequently impacts future decisions in career and education (Carli et al. 2016). In conclusion, the analysis of the included studies gives the following outlooks regarding STEM:

-

“Representation matters”: Particular interest should be given to the conditions of developing educational technology and the inclusion and representation of women in the developing process more generally. The literature on gender bias of AI-based learning technology, for instance, warns that gender stereotypes in research and training data wrongfully codify individual behaviour and reproduce gender stereotypes, thereby sustaining a practice of exclusion, misrepresentation, and inaccuracy on a greater societal scale (Buolamwini and Gebru 2018).

4.4 Exploring potentials of CSCL research design

Regarding RQ4 (estimation of the potential of CSCL in alleviating gender differences and bias), the included study corpus conveys an ambiguous view on the potential of CSCL as an instructional method to create more inclusive learning environments. Most studies viewed CSCL as a positive and effective means to integrate diverse individuals in a collaborative group learning process to build and exchange knowledge with all members (see Table 2). However, empirical findings in CSCL varied and also contradicted each other. Several papers, for instance, found that mixed-gender teams would have the best collaborative learning results and shared positive attitudes towards CSCL (Zhan et al. 2015; Cen et al. 2016), while some studies found that CSCL benefited homogeneous groups of male students best (Harskamp et al. 2008).

We also identified studies reporting the positive effects of gender diversity on team knowledge acquisition and digital competencies (Sepulveda 2018; Di Lauro 2020). Lastly, a small-scale team analysis found that the single woman in the team was empowered through co-production of decision-making but also disempowered since her expertise and ownership were questioned by the other team members and gender-stereotyped narratives in the negotiations of the role of the driver of the team limited her options (Hennessy Elliott 2020). In conclusion, the literature thus far only gives some indication that CSCL as an instructional method can alleviate gender bias with CSCL depending on the nature of the tasks and technology applied in the specific context. Since gender-equal design should be established as the norm, not the exception, an approach to exploring the potential further could be gender mainstreaming.

Gender mainstreaming is an approach that considers all genders’ interests and concerns. It includes a gender equality perspective at all levels and stages of projects and processes—also in research. The discourse on the gender dimension in collaborative learning needs to be continued in CSCL research in the future. Gender-mainstreaming in research projects in CSCL could help design more equitable and inclusive CSCL scenarios and educational practices. To have teachers and learners consciously counteract gender stereotypes also needs scientific elaboration to gain more knowledge and more advanced pedagogic tools. Also, with the help of gender-mainstreamed technologies, the formal assessment of the learning processes of learners of any gender might bring about other social, psychological, or emotional factors related to the quality of the CSCL experience and success than their gender identity.

5 Limitations

A total of 27 peer-reviewed articles in English qualified for inclusion and were further assessed. Due to our search query and single-author screening of the literature, it might be possible that single studies regarding gender in CSCL published elsewhere have been missed and that studies in other languages and relevant grey literature have been overlooked. However, given the overall state of the field regarding this topic, it appears unlikely to have systematically missed a whole line of literature in this regard. Due to a small number of studies in CSCL concerning gender, a meta-analysis with statistical measures to estimate statistical heterogeneity, for instance, was not possible. Aside from these limitations, this is the first study to comprehensively explore the relationship between gender and CSCL, employing a socio-constructivist perspective.

6 Conclusion

Our assessment of empirical studies has brought to light that further empirical research is needed to define gender in CSCL, in order to assess gender differences and whether CSCL as an educational technology can alleviate gender bias in educational practice and research in CSCL. According to the corpus of studies, CSCL offers great promise but also poses uncertainty that it can affect gender bias in STEM education sufficiently. A dedicated research agenda on gender in CSCL and new operationalisations of gender and standardised methodological reflections would be an asset to the field.

References

Abbiss, J. (2008). Rethinking the ‘problem’ of gender and IT schooling: discourses in literature. Gender and Education, 20(2), 153–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250701805839.

Ames, M. G., & Burrell, J. (2017). Connected learning’ and the equity agenda. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing. CSCW ’17: Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing. Portland Oregon USA, 25 Feb 2017.

Asterhan, C. S. C., Schwarz, B. B., & Gil, J. (2012). Small-group, computer-mediated argumentation in middle-school classrooms: the effects of gender and different types of online teacher guidance. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 82(Pt 3), 375–397. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.2011.02030.x.

Battista, L. T., & Wright, L. A. (2020). Overcoming implicit bias in collaborative online learning communities. IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-9814-5.ch002

Buffum, P. S., Frankosky, M., Boyer, K. E., Wiebe, E. N., Mott, B. W., & Lester, J. C. (2016). Collaboration and gender equity in game-based learning for middle school computer science. Computing in Science & Engineering, 18(2), 18–28. https://doi.org/10.1109/MCSE.2016.37.

Buolamwini, J., & Gebru, T. (2018). Gender shades: intersectional accuracy disparities in commercial gender classification. In Proceedings of Machine Learning Research Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (Vol. 81, pp. 1–15).

Butler, J. (2004). Undoing gender. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203499627.

Carli, L. L., Alawa, L., Lee, Y., Zhao, B., & Kim, E. (2016). Stereotypes about gender and science. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 40(2), 244–260. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684315622645.

Cen, L., Ruta, D., Powell, L., Hirsch, B., & Ng, J. (2016). Quantitative approach to collaborative learning: performance prediction, individual assessment, and group composition. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 11(2), 187–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-016-9234-6.

Charlesworth, T. E. S., & Banaji, M. R. (2019). Gender in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics: issues, causes, solutions. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 39(37), 7228–7243. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0475-18.2019.

Chen, J., Wang, M., Kirschner, P. A., & Tsai, C.-C. (2018). The role of collaboration, computer use, learning environments, and supporting strategies in CSCL: a meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 88(6), 799–843. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654318791584.

Chennabathni, R., & Rgskind, G. (1998). Gender issues in collaborative learning. Canadian Women Studies, 42, 42–45.

Chiru, C., Rebedea, T., & Trausan-Matu, S. (2013). Identifying gender differences in CSCL chat conversations. In Proceedings Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning Conference Vol. 1.

Cintron, L., Chang, Y., Cohoon, J., Tychonievich, L., Halsey, B., Yi, D., & Schmitt, G. (2019). Exploring underrepresented student motivation and perceptions of collaborative learning-enhanced CS undergraduate introductory courses. In 2019 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE). 16/10/2019–19/10/2019. (pp. 1–9).

Costaguta, R., Missio, D., & Santana-Mansilla, P. A. (2019). Preliminary analysis of gender and team roles in forum interactions. In Interacción 2019: XX International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction. Donostia Gipuzkoa Spain, 25 June 2019. https://doi.org/10.1145/3335595.

Cress, U., Rosé, C., Wise, A. F., & Oshima, J. (Eds.). (2021). International handbook of computer-supported collaborative learning (1st edn.). Computer-supported collaborative learning series, Vol. 19. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-65291-3.

Curşeu, P. L., Chappin, M. M. H., & Jansen, R. J. G. (2018). Gender diversity and motivation in collaborative learning groups: the mediating role of group discussion quality. Social Psychology of Education, 21(2), 289–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-017-9419-5.

Di Lauro, F. (2020). ‘If it is not in Wikipedia, blame yourself:’ edit-a-thons as vehicles for computer-supported collaborative learning in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 45(5), 1003–1014. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1750191.

Dillenbourg, P. (1999). What do you mean by collaborative learning? In P. Dillenbourg (Ed.), Collaborative-learning: cognitive and computational approaches (pp. 1–19). Oxford: Elsevier.

Ding, N., Bosker, R. J., & Harskamp, E. G. (2011). Exploring gender and gender pairing in the knowledge elaboration processes of students using computer-supported collaborative learning. Computers & Education, 56(2), 325–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.06.004.

European Commission (2019). Shaping Europe’s digital future. Retrieved July 20, 2022 from https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/women-digital

Fenstermaker, S., & West, C. (2009). Doing gender, doing difference: Inequality, power, and institutional change. Routledge.

Gnesdilow, D., Evenstone, A., Rutledge, J., Sullivan, S., & Puntambekar, S. (2013). Group work in the science classroom: how gender composition may affect individual performance. https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.1718.5285.

Harskamp, E., Ding, N., & Suhre, C. (2008). Group composition and its effect on female and male problem-solving in science education. Educational Research, 50(4), 307–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131880802499688.

Hennessy Elliott, C. (2020). “Run it through me:” positioning, power, and learning on a high school robotics team. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 29(4/5), 598–641. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2020.1770763.

Huynh, Q. M., Lee, J.-M., & Schuldt, B. A. (2005). The insiders’ perspectives: a focus group study on gender issues in a computer-supported collaborative learning environment. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 4, 237–255. https://doi.org/10.28945/275.

Järvelä, S., Kirschner, P. A., Panadero, E., Malmberg, J., Phielix, C., Jaspers, J., Koivuniemi, M., & Järvenoja, H. (2015). Enhancing socially shared regulation in collaborative learning groups: designing for CSCL regulation tools. Educational Technology Research and Development, 63(1), 125–142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-014-9358-1.

Kelan, E. K. (2009). Gender fatigue: the ideological dilemma of gender neutrality and discrimination in organizations. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/revue Canadienne Des Sciences De L’administration, 26(3), 197–210. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjas.106.

Kirschner, P. A., & Erkens, G. (2013). Toward a framework for CSCL research. Educational Psychologist, 48(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2012.750227.

Kirschner, P. A., Kreijns, K., Phielix, C., & Fransen, J. (2015). Awareness of cognitive and social behaviour in a CSCL environment. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 31(1), 59–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12084.

Koulouri, T., Lauria, S., & Macredie, R. D. (2017). The influence of visual feedback and gender dynamics on performance, perception and communication strategies in CSCW. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 97, 162–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2016.09.003.

Kreijns, K., Weidlich, J., & Kirschner, P. (in press). Pitfalls of social interaction in online group learning. In Cambridge handbook of Cyber behavior. Cambridge University Press.

Kwiek, M., & Roszka, W. (2021). Gender-based homophily in research: a large-scale study of man-woman collaboration. Journal of Informetrics, 15(3), 101–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2021.101171.

Lin, Y., Dowell, N., Godfrey, A., Choi, H., & Brooks, C. (2019). Modeling gender dynamics in intra and interpersonal interactions during online collaborative learning. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Learning Analytics & Knowledge (pp. 431–435). https://doi.org/10.1145/3303772.3303837.

Lindqvist, A., Sendén, M. G., & Renström, E. A. (2021). What is gender, anyway: a review of the options for operationalising gender. Psychology & Sexuality, 12(4), 332–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2020.1729844.

Luhtanen, R., & Crocker, J. (1992). A collective self-esteem scale: Self-evaluation of one’s social identity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18(3), 302–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167292183006

Mahoney, M. (2001). Boys’ toys and women’s work: feminism engages software. In Feminism in the twentieth–century: science, technology and medicine (pp. 169–185).

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62(10), 1006–1012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005.

Palonen, T., & Hakkarainen, K. (2000). Patterns of interaction in computer-supported learning: a social network analysis. In Proceedings Fourth International Conference of the Learning Sciences (pp. 334–339).

Perez-Felkner, L., McDonald, S. K., & Schneider, B. (2014). What happens to high-achieving females after high school? In I. Schoon & J. S. Eccles (Eds.), Gender differences in aspirations and attainment (pp. 285–320). https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139128933.018.

Prinsen, F. R., Volman, M., & Terwel, J. (2007). Gender-related differences in computer-mediated communication and computer-supported collaborative learning. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 23(5), 393–409. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2729.2007.00224.x.

Raes, A., Schellens, T., & De Wever, B. (2010). The impact of web-based collaborative inquiry for science learning in secondary education. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference of the Learning Sciences. ICLS ’10, Chicago, IL, USA, June 29–July 2. Vol. 1.

Rambe, P. (2017). Spaces for interactive engagement or technology for differential academic participation? Google Groups for collaborative learning at a South African University. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 29(2), 353–387. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-017-9141-5.

Reychav, I., & McHaney, R. (2017). The relationship between gender and mobile technology use in collaborative learning settings: an empirical investigation. Computers & Education, 113, 61–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.05.005.

Richard, G. T., & Giri, S. (2017). Inclusive collaborative learning with multi-interface design. In Implications for Diverse and Equitable Makerspace Education (Vol. 1, pp. 415–422).

Richard, G. T., & Hoadley, C. (2015). Learning Resilience in the Face of Bias: Online Gaming, Protective Communities and Interest-Driven Digital Learning. In Proceedings 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Collaborative Learning: Exploring the Material Conditions of CSCL. Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning Conference, CSCL, 1.

Richterich, A. (2019). Hacking events: project development practices and technology use at hackathons. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 25(5/6), 1000–1026. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856517709405.

Sepulveda, P. (2018). Computer supported collaborative learning in teaching social intervention in gender violence to the students of Social Work. In 2018 International Symposium on Computers in Education (SIIE) (pp. 1–6). https://doi.org/10.1109/siie.2018.8586742.

Stahl, G., & Hakkarainen, K. (2021). Theories of CSCL. In International handbook of computer-supported collaborative. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-65291-3_2.

Stahl, G., & Koschmann Suthers, T. D. (2006). Computer-supported collaborative learning: an historical perspective. In Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences (pp. 409–426).

Taylor, K., & Baek, Y. (2019). Grouping matters in computational robotic activities. Computers in Human Behavior, 93, 99–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.12.010.

Tomai, M., Mebane, M. E., Rosa, V., & Benedetti, M. (2014). Can computer-supported collaborative learning (CSCL) promote counter-stereotypical gender communication styles in male and female university students? Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 116, 4384–4392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.952.

West, C., & Zimmerman, D. H. (1987). Doing gender. Gender and Society, 1(2), 125–151.

Wilkinson, W. (2014). Cultural competency. Transgender Studies Quarterly, 1(1/2), 68–73.

Ying, K. M., Rodríguez, F. J., Dibble, A. L., & Boyer, K. E. (2021). Understanding women’s remote collaborative programming experiences. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 4(CSCW3), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1145/3432952.

Zhan, Z., Fong, P. S., Mei, H., & Liang, T. (2015). Effects of gender grouping on students’ group performance, individual achievements and attitudes in computer-supported collaborative learning. Computers in Human Behavior, 48, 587–596. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.02.038.

Zheng, Z., & Pinkwart, N. (2014). A discrete particle swarm optimization approach to compose heterogeneous learning groups. In 2014 IEEE 14th International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (pp. 49–51). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICALT.2014.24.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

D. Kube, J. Weidlich, I. Jivet, K. Kreijns and H. Drachsler declare that they have no competing interests.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kube, D., Weidlich, J., Jivet, I. et al. “Gendered differences versus doing gender”: a systematic review on the role of gender in CSCL. Unterrichtswiss 50, 661–688 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42010-022-00153-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42010-022-00153-y