Abstract

In policy studies, there is a concern with understanding how new ideas affect policymaking. Central to this is the issue of how ideas become collectively adopted by policy actors. The policy paradigm perspective—the classical way of understanding collective adoption—has faced criticism for overestimating the coherence of adopted ideas and not paying sufficient attention to the micro-scale cognitive processes at play during collective adoption and how these are conditioned by macro-scale organisational processes and structures. This paper provides a sociolinguistic account of the collective adoption of policy ideas that explicitly relates micro-scale cognitive processes (interpretation, attention allocation) to macro-scale organisational structure (division of labour). Drawing on relevance theory, it argues that implicit in the diffusion of an idea within policy circles is an organisationally coordinated interpretive process which results in multiple versions of the idea adapted to the division of labour of government. Supporting this is an empirical analysis of the collective adoption of resilience, sustainability and wellbeing by the British government during 2000–2020. Using a dataset of policy documents (~ 85 million tokens) published by 12 British central departments, I use BERT to automatically extract the different senses expressed by occurrences of ‘resilience’, ‘resilient’, ‘sustainable’, ‘sustainability’ and ‘wellbeing’. I examine how these senses contribute to changes in the use of this vocabulary, the contents of these senses, and the distribution of these senses across the 12 departments. Through this, I examine senses that express versions of resilience, sustainability and wellbeing adapted to particular departmental functions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

An ongoing line of research within policy studies is the impact of ideas upon policymaking. Researchers want to understand how policymaking is affected by changes in the ideas that are collectively held by policy actors [61]. Understanding this requires specification of the processes through which new ideas influence policy actors’ decisions and become collectively adopted.

This issue tends to be approached at two scales—that of individual policy actors and that of organisational systems. At the individual scale some have focussed on cognitive processes [38, 40, 66], in which ideas’ influence on policymaking consists in updates to policy actors’ mental representations and beliefs, and the impact of such updates upon decision making. At the system scale, researchers have focussed on how ideas come to be collectively adopted through organisational processes such as competition between advocacy coalitions, paradigm shifts and the formation of ‘policy windows’ [29, 42, 55]. However, despite recognition that understanding individual scale processes involving cognitive ‘micro-foundations’ [41] is crucial to specifying the processes through which ideas influence policymaking, overall researchers have tended to focus on macro-scale approaches rather than cognitive approaches [61]. As a result, how the impact of ideas is mediated by the interlinking of micro-scale cognitive and macro-scale organisational processes has been under-researched.

The micro- and macro-scale processes through which ideas influence policymaking condition each other. Updates to subjective beliefs and preferences are conditioned by organisational structure/processes and vice versa—hence the advocacy coalition framework’s emphasis on the central role policy actors’ ‘core beliefs’ play in the formation of and competition between advocacy coalitions [55]. This makes the micro–macro-relation between individuals’ cognitive and decision-making processes and organisational processes/structures central to understanding how ideas influence policymaking [39].

Current literature on the collective adoption of ideas in policymaking highlights this. The collective adoption of ideas has classically been analysed in terms of paradigms—rigid collections of shared beliefs and preferences that together form a coherent (i.e. logically consistent) discursive framework that constrains how policy actors formulate problems and make policy decisions [29]. However, analysis of the collective adoption of ideas in terms of paradigms has faced criticism for overestimating the coherence of collectively adopted ideas and not paying enough attention to how collective adoption is driven by micro-scale decision making and cognitive processes—in other words not leaving enough room for the individual agency involved in the use of ideas [28, 37, 41]. These two points are related. The tendency towards conceptualising collectively adopted ideas as rigid, coherent frameworks stems from a lack of attention to the messiness of the micro-scale cognitive/decision-making processes through which individuals use ideas [37]. This raises the question; how can the collective adoption of ideas be understood in a way that explicitly takes into account the micro–macro-relations between individual and organisational processes/structures?

Helping to answer this is the purpose of this paper. Drawing on relevance theory [59, 67], I argue that the collective adoption of ideas takes place through a sociolinguistic process of coordinated interpretation, in which individual policy actors’ interpretations of the linguistic items used to express ideas are coordinated by organisational structures via judgments of relevance. Through discussion of coordinated interpretation, I give an account of (1) what it means for an idea to be ‘collectively adopted’ that avoids positing rigid, coherent conceptual frameworks like paradigms, (2) the micro-scale mechanics of the diffusion process through which ideas become collectively adopted and (3) how these micro-scale diffusion mechanics are coordinated by macro-scale organisational structures.

The focus on diffusion is crucial. An account of the collective adoption of ideas that explicitly addresses micro–macro-relations must include an account of how ideas diffuse between people, since ultimately ideas come to be collectively adopted through communication between individuals. This is something that has been neglected in ideational literature. Though critics of the paradigm approach have come up with alternative conceptualisations of collectively adopted ideas that indeed leave more room for micro-scale individual agency and a lack of coherence (e.g. repertoires [37], Foucauldian epistemes and dispositifs [69], webs of interrelated ‘meaningful elements’ [9]), these are focussed on explaining in what sense ideas are ‘collectively adopted’ rather than how ideas become ‘collectively adopted’. Therefore, the diffusion process that leads to collective adoption has not been discussed much by these alternative conceptualisations.

To support my notion of coordinated interpretation, I conduct an empirical analysis of the diffusion of the ideas resilience, sustainability and wellbeing throughout the British government’s departmental division of labour (i.e. departmental division of labour; Department for Education, Department for Digital, Culture, and Media & Sport). I focus on the relation between the diffusion of resilience, sustainability and wellbeing and the polysemy of the terms used to express these ideas (‘resilience’, ‘resilient’, ‘sustainable’, ‘sustainability’, and ‘wellbeing’)—i.e. the range of different senses that can be expressed by these terms—and how both are conditioned by the organisational structures represented by the government’s departmental division of labour. Since the range of possible ways of interpreting some term is reflected in the different senses expressed by occurrences of the term, analysis of polysemy allows me to examine how interpretation is coordinated by organisational structure. This empirical analysis is conducted on a dataset of token sequences (~ 85 million tokens) sampled from ~ 120,000 British government documents published between 2000 and 2020. I make use of word sense induction (WSI) via BERT [18, 44] to automatically extract the different senses expressed by ‘resilience’, ‘resilient’, ‘sustainable’, ‘sustainability’ and ‘wellbeing’ in the dataset. This allows me to examine the relation between these terms’ polysemy and the departmental division of labour quantitatively.

This paper has six sections. The first section gives an overview of the central claims made about coordinated interpretation and idea diffusion. The second section contextualises resilience, sustainability and wellbeing, summarising existing research on the overall direction of policy change produced by their adoption. The third section explains the methods and data used. The fourth section presents the results of the empirical analysis of the diffusion and polysemy of resilience, sustainability and wellbeing. The fifth and sixth sections discuss the results, using them to argue that coordinated interpretation indeed acts as an interface between the organisational and cognitive processes and to illustrate how coordinated interpretation happens.

Idea diffusion, coordinated interpretation and micro–macro-relations

If an idea has been collectively adopted by a collection of organisations, it must have undergone diffusion. There must have been a process through which the idea spread across the collection of organisations, either from sources outside the collection, an initial subset of the collection, or both. Literature on the shift from the post-war Keynesian consensus to neoliberal economic policy provides a good illustration of this. Researchers have noted the role played by think tanks [21, 47, 53, 58, 60] as conduits for the spread of neoliberal arguments between academics critical of Keynesian economics and policy actors. In the UK prior to Thatcher’s government neoliberal arguments spread between the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA), London School of Economics (LSE), University of Chicago and the Conservative Party [12, 16].

A complete analysis of the British government’s collective adoption of neoliberal ideas during 1980s UK that explicitly addresses the micro- and macro-processes involved would need to include; an account of the diffusion of ideas between the IEA, LSE, University of Chicago and the Conservative party, conducted through tracking of the interpersonal social networks of the individuals involved in these organisations; the communications had within these interpersonal networks and the exposure of these individuals to these organisations’ publications. In addition to this, a complete analysis would also need to include an account of how neoliberal ideas diffused amongst the multitude of civil servants, councillors, consultants etc. who work in the organisations responsible for making and delivering policy—central departments, local authorities, agencies and so on. After all, circulation of an idea amongst the governing party is not enough to consider it fully adopted. It needs to be in active use within the policy process.

One can think of this idea diffusion from a cognitive perspective, in terms of the spread of mental representations and updates to subjective beliefs and policy preferences. However, this idea diffusion is simultaneously a linguistic process. Familiarity with an idea comes only through reading or hearing about it—ideas spread because the linguistic items (particular statements, arguments and terms) used to express them spread. The diffusion of these linguistic items happens through being continuously used in policy actors’ communications, which in turn means they are continuously being interpreted. Therefore, the diffusion of an idea is mediated by a multitude of interpretations of the linguistic items used to discuss the idea.

My central claim is that the micro-scale cognitive processes and the macro-scale organisational structures involved in the collective adoption of policy ideas are intertwined through this linguistic, interpretive process. Following the relevance theoretic notion that linguistic interpretation is a relevance-maximising process, I argue that organisational structures constrain what policy actors consider relevant, which shapes how they interpret the linguistic items used to express some idea. This in turn constrains the cognitive processes through which policy actors use ideas to make policy decisions. Thus, the collective adoption of ideas by government organisations happens through a process of linguistic diffusion, in which organisational structure coordinates cognitive processes through coordination of the relevance-maximising operations inherent in policy actors’ interpretive acts.

This is a very rough characterisation of the points I want to make. I reserve a more detailed explanation to the discussion section of this paper, where I can draw upon the results of my empirical analysis. At this point, what is important is the notion that organisational structures coordinate policy actors’ interpretive acts. If this is true, one would expect the organisational coordination of interpretation to be reflected in the polysemy of the terms used to express diffusing ideas. One might expect, for example, certain senses to be particularly associated with certain organisational structures. There are two reasons why polysemy would reflect organisational coordination of interpretation. First, the range of possible ways of interpreting a term will be reflected in the senses expressed by occurrences of the term. Second, since the diffusion of a term happens through the accumulation of individual choices to use the term in a particular way and, therefore, to express a particular sense, polysemy is a consequence of diffusion. As coordinated interpretation is something that happens during diffusion, one would expect the polysemy generated by diffusion to be shaped by and, therefore, reflect coordinated interpretation.

Because of this, I argue for the importance of coordinated interpretation in collective adoption through empirical analysis of the polysemy of ‘resilience’, ‘resilient’, ‘sustainable’, ‘sustainability’ and ‘wellbeing’ across the British government’s departmental division of labourFootnote 1 during 2000–2020. I refer to these words collectively as the ‘target vocabulary’ for short. The purpose here is to show that the departmental division of labour coordinates the cognitive processes through which policy actors use resilience, sustainability and wellbeing through coordination of how policy actors interpret the target vocabulary, thus providing an example of a specific instance where organisational structure coordinated individual cognitive processes through coordinating interpretation. I identify which senses are dominant during periods of diffusion, the contents expressed by dominant senses and the extent to which particular senses are associated with particular aspects of the departmental division of labour. Before proceeding with this, I explain the decision to focus on resilience, sustainability and wellbeing.

Resilience, sustainability and wellbeing

The decision to focus on resilience, sustainability and wellbeing was made because they represent a recent, large-scale shift in policymaking. Joseph and McGregor collectively refer to these ideas as ‘the new trinity of governance’ [40], arguing that they represent a new mode of neoliberal policymaking that attempts to balance maintaining neoliberalism’s emphases on growth and trade liberalisation with addressing neoliberalism’s failure in addressing economic, political and environmental crises (e.g. climate crisis, 2008 crash). Other commentators have similarly noted the recent ubiquity and influence of these concepts in policymaking [8, 10, 13]. As such, researchers more or less know how these ideas impacted policymaking. This provides a straightforward way to contextualise this paper’s theoretical concerns in relation to a known instance of pervasive policy change in the later sections. I briefly summarise what is known about the adoption of these ideas into neoliberal governance:

-

1.

Resilience was adapted into governance from academia, in particular ecology and psychology [40]. Common to these academic notions is that people or systems have a default state and ways of returning to the default state after disturbance. For example, C.S. Holling used resilience to explain how ecosystems self-organise into new default states in response to disturbances, e.g. the default ratio of different animals’ populations in a forest might change after a wildfire [35]. In psychology, resilience has been used to refer to the capacity of people to return to a default level of wellbeing after a traumatic event such as the death of a loved one [40]. Commentators have noted that its use in Anglo-American governance has increased especially after the 2008 financial crisis [5, 40], but in UK policymaking its use is older [57], following the transfer of responsibility for crisis management from the Home Office to the Cabinet Office in 2001. Since this transfer, resilience in British policy has largely been used in security policy, in which it is used to describe a country’s organisational capacity to return to a default state of functioning after crises such as terror attacks and natural disasters. This capacity is built through actions like requiring organisations to undertake risk assessments, and such actions are statutory requirements following the 2004 Civil Contingencies Act [70]. An important trigger for this reorientation of crisis and risk governance was the collapse of the Soviet Union, which shifted attention away from the potential of military conflict towards ‘civilian disasters, including the King’s Cross underground fire (1987), the Zeebrugge ferry sinking (1987), the Clapham rail crash (1988) and the Hillsborough stadium tragedy (1989)’ [57].

-

2.

The current policymaking use of sustainability is derived from the Club of Rome’s The Limits to Growth [8, 45]. This book argues that if economic and population growth continue to increase exponentially societies will face collapse within a century. Here, sustainability means the capacity to manage resources and population in a way that will not cause total collapse through transitioning towards policy designed to achieve ‘global equilibrium’ [45], in which growth is abandoned as a goal and replaced by requirements of keeping population and quantity of capital, as well as their ratio to each other, constant [45]. Sustainability was adapted into international development policy through the Brundtland report, which outlined a notion of sustainable development and growth—growth that is able to meet ‘the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ [68]. The idea of sustainable development has since been the most noticeable application of sustainability in governance. In the UK, the notion was at the centre of New Labour’s ‘Sustainable Communities’ urban regeneration programme [52], which sought to address the decline of the UK’s former industrial centres through addressing housing problems (lack of supply, abandonment, etc.) and pursuing economic development whilst minimising the environmental impact of this development through measures and targets concerning biodiversity, greenbelt use, flood risks and so on [52].

-

3.

Joseph and McGregor track the current adoption of wellbeing to positive psychology and the capabilities approach to development advanced by development economists and philosophers, most notably Amartya Sen, Martha Nussbaum and Sabine Alkire [40]. Psychological discussion of wellbeing largely concerns the measurement of subjective wellbeing—wellbeing as happiness. The capabilities version of wellbeing focuses more on the conditions needed for people to lead fulfilling lives, and how access to such conditions can be measured. This is the rationale behind the Human Development Index (HDI), which bundles measurements of life expectancy, education level, per capita income, and so on. This sense of wellbeing has had particular impact in international development, with the HDI being used by the United Nations Development Programme. Joseph and McGregor note the psychological version has been more influential in British policymaking, pointing to the Cabinet Office’s establishment of the Behavioural Insights Team in 2010, unofficially known as the ‘Nudge Unit’. One area of concern for the Nudge Unit involves drawing upon behavioural science to devise policies that encourage, without any direct interference, people to make choices that improve subjective wellbeing [40].

The policy changes described above are all underpinned by a shift away from the narrowly economistic common sense that characterised the kind of neoliberal governance that accompanied the shift towards monetarism in the 1980s. This economistic common sense approached most, if not all, policy issues through expanding and removing impositions upon markets. For example, global poverty was approached through the global expansion of trade liberalisation to generate growth (hence the Washington consensus), 1970s inflation was understood in terms of the imposition upon labour markets/the price mechanism by trade unions and the issue of improving public services was approached through introducing market mechanisms into government procurement and service provision. There are two aspects of this economistic common sense that resilience, sustainability and wellbeing depart from. The first aspect is the tendency to understand society in general in the same way orthodox economists understand markets [26, 40]—as a consequence of the utility calculations of rational, self-interest individuals. The second aspect is the growth paradigm [56], in which it is held that there is no limit to the extent to which economic growth can be pursued, that growth is the solution for key problems such as global poverty and that growth is equivalent to social progress.

Resilience departs from the first aspect. As a result of its ecological baggage, its adoption came with the adoption of a complex systems perspective of social systems quite distinct from the market-based perspective characteristic of the economistic perspective. As a complex system intertwined with multiple other systems, society inevitably contains an element of unpredictability that cannot be dealt with using the tools of orthodox economics [4, 40]. Sustainability and wellbeing depart from the growth paradigm. As noted above, the initial formulation of sustainability in The Limits to Growth was radically opposed to the notion that economic growth could be limitlessly pursued and constituted the solution for the most pressing social issues, arguing that the quest for growth should be replaced with the quest for global equilibrium. In sustainable development, we see a watering down of the Club of Rome’s arguments since development is still ultimately about pursuing economic growth [3]. Nevertheless there remains recognition that there is some kind of limit to growth that must be observed, if not as strict as the limit required by global equilibrium. The adoption of wellbeing was a result of criticisms of the notion that social progress is equivalent to economic growth, and therefore, entirely trackable through economic measurements such as GDP [40]. Both psychological and capabilities versions of wellbeing were used to articulate those aspects of ‘progress’ that are not necessarily reflected in growth, and to advocate for a shift towards supplementing economic measures with measures such as HDI and happiness indices.

In a similar way to how the many of the policy changes of 1980s Anglo-American governance were part of an overall direction of policy change from Keynesianism to economistic neoliberalism, the various policy changes introduced through resilience, sustainability and wellbeing are part of an overall direction of policy change away from a purely economistic version of neoliberalism to a less economistic version. For brevity, I call this less economistic version ‘crisis neoliberalism’, since it is more worried about the risk of crises. It is important to stress that the shift from economistic to crisis neoliberalism is nowhere near as radical as the shift from Keynesianism to monetarism. Crisis neoliberalism is still neoliberalism. The governments who adopted resilience, sustainability and wellbeing between 2000 and 2020 maintained the core emphases of 1980s neoliberalism: economic growth, deregulation (e.g. the Conservative’s 2015 Deregulation Act), reducing public spending (e.g. the post-2010 austerity policies introduced by the Conservative-Liberal coalition) and introducing market mechanisms into the provision of state services (e.g. New Labour’s adoption of public–private partnerships).

It is worth noting that the above analyses provide an account of why resilience, sustainability and wellbeing were adopted, rather than how. They explain the reasoning behind their adoption and how this reasoning emerged from various circumstances from the collapse of the Soviet Union to the 2008 financial crisis. As emphasised in previous sections, understanding how, rather than why, these ideas were adopted must be based on an account of the linguistic, cognitive and organisational processes involved in their diffusion.

Dataset and methods

To analyse the polysemy of the target vocabulary, I use a dataset representing the documents of 12 central government departments published during 2000–2020 sourced from gov.uk and webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Web scrapersFootnote 2 were used to download.pdf files from these websites, which were then converted into.txt format using the command line utility QPDF. Gov.uk was used to retrieve documents produced by central departments from 2010 to 2020, webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk was used to retrieve central department documents produced between 2000 and 2010. Approximately, 120,000 documents were collected. A stratified sample of sentences containing approximately 85 million tokens was taken from this collection, where each strata contains sentences of the documents of one central government department during 1 year. To avoid potential problems of unequal strata sizes affecting data analysis, sampling was done such that all strata (where a single stratum contains the sentences of a single department in a single year) all contained the same number of sentences (25,000 sentences per department per year). Departments which had less than 25,000 sentences in more than 2 years between 2000 and 2020 were excluded, which possibly means some distinct uses of the target vocabulary are excluded from this study.

Departmental documents were used because departments are the most powerful organisations responsible for implementing policy, being directly accountable to Parliament and with the heads of each department (i.e. Secretaries of State and the Chancellor of the Exchequer) being members of the Cabinet, the chief executive power in the British parliamentary system. As previously mentioned, an idea cannot be understood as fully adopted unless it is in active use across the policy process, meaning analysis of the adoption of resilience, sustainability and wellbeing requires a dataset that represents as much of the policy process as possible. The central position of departments within the government means their documents represent a greater portion of the policy process than other available government documents, such legislation and records of parliamentary debates (whose influence on the policy process is very indirect compared to departmental documents and legislation). As departments share the same hierarchical position in government, they represent comparable portions of the policy process. Though primary and secondary legislation represent a considerable portion of policy implementation, it was found that legislation has quite a distinct legal vocabulary not found elsewhere in government that does not include extensive use of the target vocabulary, often to the extent that running valid statistical tests involving legislation and target vocabulary senses was not possible. Because of this, legislation was not included in the dataset.

Most of the policy actors working in departments are civil servants, though as ministerial organisations these departments have a number of ministers working in them too. The documents of the dataset also include documents produced by organisations that are commissioned by departments such as universities and market research firms, so a minority of policy actors are academics and private sector consultants. There are a very wide variety of documents represented in the data set, including white papers, policy impact assessments, departmental reviews, annual accounts, guidance, surveys, specifications of targets and standards, and draft legislation. Documents produced by bodies that are either accountable to or within the oversight of central departments are also included (e.g. the documents of executive agencies and multi-agent partnerships). Again, to ensure as much of the policy process as possible was represented, there were no restrictions on what kind of departmental document was included in the dataset.

To automatically extract the different senses expressed in the dataset by the target vocabulary, I used Lucy and Bamman’s method of word sense induction (WSI) via BERT [44]. WSI is a procedure for automatically extracting the different senses expressed by the occurrences of a word. For example, consider a document containing 10 occurrences of ‘bank’ where 5 of these occurrences express the financial organisation sense and the other 5 express the river bank sense. A good WSI procedure will be able to automatically determine which of these occurrences concerns the financial organisation sense and which of these occurrences concerns the river bank sense.

There are two basic steps involved in large language model (LLM)-based WSI—(a) retrieving token embeddings and (b) clustering token embeddings. For (a), a LLM is used to produce an embedding representation of every occurrence in a given dataset of a given target vocabulary. These embeddings are called token embeddings. Since LLMs are designed and pre-trained in such a way that the token embeddings they produce encode the linguistic features distinctive of the occurrences they represent (without any need for fine-tuning), the similarity between token embeddings (measured with cosine similarity or Euclidean distance) captures how similar in meaning token embeddings are. The more similar two token embeddings are, the more similar in meaning the occurrences they represent are. Therefore, (b) involves using a clustering algorithm to sort the token embeddings corresponding to each word in the target vocabulary into clusters, where embeddings are sorted into the same cluster if they are more similar to each other than others. Each cluster is taken to represent a particular sense of a word. To illustrate with the above ‘bank’ example, (a) would involve retrieving token embeddings of all 10 occurrences of ‘bank’ using an LLM, and (b) would involve clustering the embeddings representing these 10 occurrences. If successful, the result would be 2 clusters of 5 token embeddings, with the first cluster’s embeddings corresponding to occurrences of ‘bank’ expressing the financial organisation sense and the second cluster’s embeddings corresponding to the river bank sense.

Since (b) can be computationally intensive when clustering large numbers of token embeddings, Lucy and Bamman do not perform (b) on all token embeddings retrieved [44]. For each word, they take a random sample of 500 token embeddings from the total number of token embeddings retrieved from BERT for the word and only perform (b) on this sample. They then match the rest of the token embeddings corresponding to the word to the clusters induced from the sample of 500 via cluster matching. In cluster matching, a token embedding is matched to a sense cluster by first finding the similarities between the embedding and the centroids of all sense clusters induced for the word. Then, the embedding is matched to the cluster with the centroid it has the greatest similarity to. For example, if through (a) 2000 token embeddings representing occurrences of ‘bank’ were retrieved, (b) would only be performed on a random sample of 500 of these 2000 embeddings. The remaining 1500 would be matched to the clusters induced from the sample of 500 through comparing the similarities between each of the 1500 embeddings to the centroids of each induced cluster. By only performing (2) on a sample of 500 and then using cluster matching, Lucy and Bamman’s method of achieves good, if not state-of-the-art, results on the standardised datasets for testing WSI procedures (SemEval 2010 Task 14 and SemEval 2013 Task 13) whilst being significantly less computationally intensive and time consuming than the state-of-the-art [44]. This paper uses the same procedure.

K-means is the clustering algorithm used for (2) on the sample of 500. It requires that the number of clusters k to be generated is set manually. Lucy and Bamman devise an automated procedure for choosing a k between 2 and 9 according to the minimum residual sum of squares. This paper does not do this, instead opting to fix k at 9. This was because it was found through manual inspection that choosing a k according to the minimum residual sum of squares resulted in small numbers of clusters where each cluster contains occurrences that ought to be considered as different senses. Returning to the ‘bank’ example, this would be equivalent to a cluster containing occurrences expressing both financial institution and river bank senses. A k of 9 was chosen to minimise this problem. Higher values were not used to avoid the opposite problem in which multiple clusters all contain occurrences expressing the same sense (e.g. a situation where 2 clusters of ‘bank’ both contain occurrences expressing the same financial institution sense).

Once sense clusters are retrieved, their contents need to be understood. A problem with this is that each cluster might consist of thousands of expressions, making reliably gaining an overall impression of the contents of sense clusters labour intensive and difficult. To mitigate this, I follow the approach to sense cluster interpretation found in [50], in which the key terms of each sense cluster—those terms that are most relevant/unique to a cluster—are retrieved. These key terms give an overview of the unique word uses captured by the induced sense. Key terms are retrieved by measuring the term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) of each term in the expressions composing each sense cluster:

Here, freqcluster(term) is the frequency of the term in a particular cluster, N is the total number of sense clusters and d(term) is the number of clusters the term appears in. Once the TF-IDF of each term in a cluster is found, those terms which have the highest TF-IDF are taken to be the key terms of the cluster. I take the 10 words and bigrams of a cluster with the highest TF-IDF to be the cluster’s key terms. Stopwords and words that appear in more than 80% of each word’s sense clusters were excluded from TF-IDF calculations. I use these key terms to ensure what is concluded from manual inspection of sense clusters represents the main word uses captured by clusters and is not dependent on cherry picking cluster expressions. Some sense cluster expressions, though not identical with each other, were nevertheless extremely similar. Such expressions came from documents that were also very similar though not identical. These expressions were also excluded from TF-IDF calculations. Though in [50] key terms were used to avoid manual inspection of cluster expressions entirely, there is a lot of useful information about the word uses captured by induced senses that can only be gained through reading sense cluster expressions. Therefore, I use key terms as a guide for and check upon manual inspection rather than as a replacement.

Results

I now present the results of empirical examination of the target vocabulary’s observable polysemy. There are three focuses; (1) identification of dominant senses during periods of diffusion, (2) sense content, i.e. what is expressed by target vocabulary senses and (3) distribution of senses across departmental division of labour, i.e. the extent to which particular senses are associated with particular portions of the departmental division of labour.

1. Periods of diffusion and dominant senses: The plots on the left of Fig. 1 show the changes in relative frequency of the target vocabulary across 2000–2020. Each point in each plot represents the relative frequency of a word in a year. Generalised additive modelsFootnote 3 (represented by the blue line) were fitted to the data points to provide a clearer picture of the overall trends within each word’s changes in relative frequency. The dashed lines represent 95% confidence intervals. These plots provide an overview of diffusion of the target vocabulary, with periods of increase in relative frequency corresponding to periods of diffusion. ‘Resilience’, ‘resilient’ and ‘sustainable’ display two waves of diffusion, with the first wave tending to happen between 2000 and 2010 and the second wave tending to happen between 2015 and 2020—besides ‘resilient’ whose second wave appears to not have peaked before 2020. In contrast ‘sustainability’ and ‘wellbeing’ have much less distinct waves of diffusion—it is better to say they have been more or less consistently diffusing between 2000 and 2020.

Relative frequencies of the target vocabulary and target vocabulary senses over time: the plots on the left visualise the changes in the relative frequency of the target vocabulary over time. The plots on the right visualise the changes in the relative frequency of target vocabulary senses over time

The plots on the right of Fig. 1 visualise the relative frequencies of each of the senses that compose the overall relative frequencies of each of the target vocabulary’s words. Again, generalised additive models were fitted to provide a clearer picture of the overall trends in changes in each sense’s relative frequencies. Each coloured line represents the relative frequencies over time of a particular sense, where each sense is indexed from 0 to 8. Through these plots one can see what uses underpin the diffusion of the target vocabulary—thus, one can see that much of the first wave of the diffusion of ‘resilience’ is a result of an increase in the use of the sense resilience 3. These plots also enable identification of the most dominant senses during periods of diffusion—the senses that have the highest relative frequencies during periods of diffusion. Resilience 3 is the dominant sense most responsible for the diffusion of ‘resilience’ between 2000 and 2010.

2. Sense contents: I focus examination of sense contents on these dominant senses. This ensures that analysis captures the central word uses responsible for diffusion. I also use these dominant senses to ensure that during discussion of sense distribution, the patterns of distribution discussed hold for the main word uses behind target vocabulary diffusion—if these patterns were only true for quite marginal senses, my argument would be weakened considerably.

Resilience

Sense | Key terms |

|---|---|

2 | security resilience, preparedness resilience, emergency preparedness, resistance resilience, resilience response, response april, stability resilience, health emergency, readiness resilience, flood resistance |

3 | local resilience, resilience forums, resilience forum, national resilience, london resilience, regional resilience, category responders, uk resilience, resilience extranet, cabinet office |

7 | flood resilience, climate resilience, financial resilience, network resilience, cyber resilience, sector resilience, business resilience, infrastructure resilience, director general, energy resilience |

The first wave in the growth of ‘resilience’ is largely the result of the growth of the sense resilience 3, which is composed of occurrences in expressions about regional resilience:

-

‘The Government News Network GNN made a major contribution to improving regional resilience by establishing Regional Media Emergency Forums […]’ [6]

-

‘The London Resilience Team includes secondees drawn from the organisations represented at the London Regional Resilience Forum […]’ [43]

-

‘[…] the Regulations provides that general Category 1 Responders which have functions which are exercisable in a particular local resilience area in England or Wales must co-operate with each other in connection with the performance of their duties under section 21 of the CCA […]’ [7].

Regional resilience is a way of talking about how services are to be coordinated in a way that enables them to respond to emergencies as effectively as possible—some area is resilient if their responder services are arranged in a particular way, not resilient if not. The optimal manner of coordinating services is set out in various pieces of legislation and Cabinet Office documents, especially the 2004 Civil Contingencies Act [70], meaning occurrences of resilience 3 have a fairly precise definition. Thus, regional resilience is defined in terms of certain organisations—whose establishment/constitution is required/defined by the Civil Contingencies Act 2004, e.g. Local Resilience Forums—meeting the standards set out by the Act and other Cabinet Office documents. This corroborates the research on resilience discussed in “Idea diffusion, coordinated interpretation and micro–macro-relations”, in which the central role of the Cabinet Office and in using resilience to craft security policy on risk and crisis management is noted.

In contrast, the second wave of growth (after 2015) in the use of ‘resilience’ is not dominated by a particular sense compared to the first wave, and those senses which contribute the most to the second wave of growth do not correspond to a precise definition of ‘resilience’ to the same extent as resilience 3. Thus, the two senses which contribute the most to the increase in use of ‘resilience’ after 2015 are resilience 2 and resilience 7, which correspond to uses of ‘resilience’ as a general noun/noun phrase (e.g. ‘Operational analytical resilience is low’ [32]) and uses of ‘resilience’ as part of a list or conjunction (e.g. ‘Through our responsibilities for domestic security and resilience, policing, drugs, race equality and active communities, our criminal justice system and our immigration and asylum policy, we are in a unique position to […]’ [36]). Though senses of resilience corresponding to more specific notions of resilience do contribute to the second wave of the growth—resilience 5, which makes the 3rd greatest contribution to the second wave of growth, corresponds to children’s psychological resilience/resilienceFootnote 4 as a personal trait (e.g. ‘Importantly, their experiences during the teenage years combine to shape their character, their personal attributes, and their level of resilience […]’ [17])—that resilience 2 and resilience 7 contribute the most to the second wave suggests the second wave is largely the result of uses of ‘resilience’ as a generic noun without a particularly specific, specialised meaning.

Resilient

Sense | Key terms |

|---|---|

3 | secure resilient, sustainable resilient, cohesive active, national security, resilient extremism, active resilient, safe resilient, communities cohesive, dso, robust resilient |

6 | resilient layer, unit supported, fixed, bandwidth, layer resilient, supported floor, floating layer, wall, timber, floor coverings |

7 | Resilient telecommunications, water act, resilient supply, planning, waterways obligations, support management, supply support, obligations water, management inland, maintain water |

Notable about the use of ‘resilient’ over time is resilient 6, which starts off as contributing somewhat to the overall relative frequency of ‘resilient’ but ends up generally contributing the least after 2009. Its initial peak in 2000 is potentially misleading—one would need data from the 1990s to see if resilient 6’s peak in 2000 is a one off or part of a longer, older trend. Nevertheless, one can see there is a general decline in the use of resilient 6 compared to other senses between 2007 and 2020. Resilient 6 consists of uses of ‘resilient’ that relate to engineering, construction or other fields rooted in natural science:

-

‘Complaints appear to be growing from the occupiers of flats suffering increased levels of impact noise transmission from the flat above due to the laying of laminate wood floor finishes as a substitute for carpet or other resilient floor coverings […]’ [15]

-

‘The turbine blades for the Jumo 004 were manufactured from a steel-based allow containing some nickel and chromium, though the material used was insufficiently resilient to withstand the very high temperatures and high tensile stresses encountered in that part of the engine […]’ [54]

-

‘[…] edge switches shall be stacked using specific and dedicated stacking ports to enable high speed communication between each switch in the stack as a part of a dedicated resilient architecture […]’ [14].

As resilient 6 has declined, senses similar to the generic resilience 2 and resilience 7 have increased in use. Therefore, the senses that have contributed the most to both waves of the growth of ‘resilient’ are resilient 3 and resilient 7. Resilient 3 contains expressions that are judgments of how resilient something is, e.g. ‘Morale was reported to be surprisingly resilient but officers reflected anxiety about the future’ [46], ‘Domestic demand remained the most resilient sector’ [25], ‘After a decade of sound macroeconomic policy and the promotion of flexible and open product, labour and capital markets, there is clear evidence that the UK economy is more resilient than in the past’ [63]. Resilient 7 contains expressions using ‘resilient’ as a general adjective, e.g. ‘In the UK, resilient house prices and the general strength of consumer spending acted as a brake on similar rate reductions’ [62]. Like resilience 2 and resilience 7, resilient 2 and resilient 7 do not relate to occurrences that relate to an explicit, precise definition of ‘resilience’/’resilient’ like resilience 3.

Sustainable

Sense | Key terms |

|---|---|

0 | fair sustainable, strong sustainable, affordable sustainable, sustainable structures, sustainable pay, efficient sustainable, new fair, sustainable bands, staff fair, effective sustainable |

3 | financially sustainable, government sustainable, dcms sustainable, environmentally sustainable, fco sustainable, un sustainable, mod sustainable, sustainable indicators, division, securing future |

The use of ‘sustainable’ resembles the use of ‘resilience’ in that it is led by a single sense—sustainable 3—that relates to explicitly specified characterisations of ‘sustainable’. Sustainable 3 consists of expressions in which ‘sustainable’ are either related to or used as a part of names of documentation/guidelines/programmes/objectives/organisations etc. Thus, most of the key terms for sustainable 3 are related to documents like the following:

-

Securing the Future: Delivering UK Sustainable Development Strategy [34]: government sustainable,Footnote 5 securing future

-

UK International Priorities: The FCO Sustainable Development Strategy [24]: fco sustainable

-

UN Sustainable Development Goals [65]: un sustainable

-

MOD Sustainable Development Strategy [49]: mod sustainable.

That the use of ‘sustainable’ as part of names for various kinds of documentation/rules/procedures is the main reason for both waves of growth in the use of ‘sustainable’ suggests both waves of growth involve a proliferation in efforts to give explicit definitions of ‘sustainable’, since much of the purpose of such documents/rules/procedures is to set out standards people can use to determine when something is ‘sustainable’ or not. For example, Securing the Future describes New Labour’s overall plan for sustainable development, i.e. achieving economic growth whilst simultaneously mitigating the effects of climate change through things like disincentivizing waste production via taxes (HM Government 2005: 50), encouraging emissions trading [34], mandating electricity suppliers to source a portion of their sales from renewable sources [34], and so on. To measure the success of such policies, Securing the Future provides a range of indicatorsFootnote 6 [34], e.g. CO2 emissions by end user, household energy use, people of working age in employment etc. In effect, ‘sustainable’ is defined in terms of these indicators—x is sustainable if such and such indicator thresholds are reached.

It is worth noting that these indicators and targets are not entirely specified within Securing the Future—full specification is delegated to a range of other documents, in particular Public Service Agreements. ‘Sustainable’ is, therefore, not entirely defined within any single document—it is defined via an intertextual network of measurable indicators. Documents that include ‘sustainable’ in the title tend to form elements in intertext networks which as a collective define ‘sustainable’ in terms of a range of standards/targets precise enough to be used in implementation.

Another similarity in the change over time in the use of ‘sustainable’ to the change in the use of ‘resilience’ is that more generic senses play a greater role in the growth of ‘sustainable’ after 2015, thus sustainable 0, which contains sentences in which ‘sustainable’ is used in a list or conjunction (e.g. ‘Rather, achieving the goals of food and energy security requires the international community to work together to harness the power and the innovation of the global system, underpinned by a renewed commitment to openness and fairness, to deliver more stable, secure and sustainable commodity markets’ [64]), becomes the second greatest contributor to the use of ‘sustainable’ from 2015.

Sustainability

Sense | Key terms |

|---|---|

0 | sustainability appraisal, approach sustainability, oda, aspects sustainability, sustainability reporting, issues sustainability, focus sustainability, principles sustainability, ensuring sustainability, understanding sustainability |

4 | fiscal sustainability, session hc, treasury minutes, report financial, term fiscal, economic sustainability, pac report, hc pac, wales session, obr fiscal |

7 | sustainability appraisal, sustainability reporting, sustainability, transformation, report sustainability, ensure sustainability, fco sustainability, levy sustainability, sustainability fund, aggregates levy, transport |

The growth of ‘sustainability’ is similar to the growth of ‘sustainable’ in that the sense that contributes the most to growth—sustainability 7—largely involves ‘sustainability’ as part of the names of particular documents/procedures/rules—e.g. ‘Following the issue of the Department’s Sustainability Appraisal Handbook, the integration of Sustainability Appraisal into decision making on the Estate has grown substantially’ [48], thus sustainability 7’s key terms largely capture bigrams related to documents/procedures/rules such as sustainability appraisals, sustainability and transformation partnerships (partnerships of local authorities and NHS organisations that plan NHS spending in England), the Aggregates Levy Sustainability Fund, FCO sustainability reports, and so on. This again suggests that the production of intertextual networks which collectively provide standards for explicitly defining ‘sustainability’ in various contexts is an important part of the overall use of ‘sustainability’.

More generic uses are again a central part of the use of ‘sustainability’, with sustainability 0, which largely covers expressions in which ‘sustainability’ features as a generic noun (though there is some overlap with sustainability 7 as shown by key terms ‘sustainability appraisal’ and ‘sustainability reporting’), contributing the second most to overall use of ‘sustainability’ for most years. However, it is notable that from 2016 onwards the less generic sustainability 4, which largely relates to fiscal/economic sustainability, contributes the second most to overall use of ‘sustainability’.

Wellbeing

The increase in the use of ‘wellbeing’ before 2005 is largely led by wellbeing 7, which covers uses of ‘wellbeing’ as a generic noun, e.g. ‘Preservation and study of cultural heritage contributes to overall social wellbeing through understanding and appreciation of the past and its legacy’ [22].

Sense | Key terms |

|---|---|

2 | employee health, good health, promote health, advice, improving health, safety wellbeing, confidence, physical activity, support health, health england |

3 | subjective wellbeing, measures wellbeing, personal wellbeing, life satisfaction, associated, ons, rating, culture sport, national wellbeing, slightly higher |

5 | wellbeing valuation, psychological wellbeing, previous survey, wellbeing index, difference comparison, wellbeing feasibility, feasibility pilot, difference cs, staff wellbeing, scale |

6 | wellbeing board, survey employees, work survey, wellbeing work, joint health, commissioning groups, wellbeing strategy, clinical commissioning, secretary health, cabinet secretary |

7 | economic wellbeing, social wellbeing, children wellbeing, people wellbeing, economic social, personal wellbeing, different areas, financial wellbeing, tell economic, productivity tell |

8 | psychological wellbeing, wellbeing work, work feasibility, feasibility pilot, emotional wellbeing, telephone support, work psychological, evaluation group, group work, evaluation telephone |

The key terms of wellbeing 7 list the typical phrases that result from this generic use of ‘wellbeing’. After 2005 more specialised senses contributed the most to the increase in the use of ‘wellbeing’, with wellbeing 6 and wellbeing 2 contributing the most to the increase in ‘wellbeing’ between 2008 and 2014. Wellbeing 6 is similar to resilience 3, sustainable 3 and sustainability 7 in that it involves expressions in which ‘wellbeing’ forms part of the name of documentation/procedures/standards/organisations. Thus wellbeing 6’s key terms relate to things like health and wellbeing strategies, health and wellbeing boards (local authority committees responsible for producing strategy relating to ‘health and wellbeing’), joint health and wellbeing strategies, and so on:

-

‘There was strong support for exploring the scope for self-assessment following the consultation on the Independence, Wellbeing and Choice social care green paper, and in the White Paper Our Health, Our Care, Our Say’ [31]

-

‘If a health and wellbeing board has specific objections, the NHS Commissioning Board will have to satisfy itself that any such objections have been properly considered’ [2]

-

‘Having health and wellbeing boards at a local level in local authorities also mitigates the possible risk of potentially diverse clinical commissioning groups not working together on the strategic needs of a local population’ [19].

Such documentation/procedures/organisations in general relate to ‘health and wellbeing’ in particular, and therefore, represent an inter-organisational/intertextual effort to provide/implement an explicit definition of wellbeing in relation to health as understood from a medical perspective—hence the organisations mentioned in wellbeing 6’s key terms are connected to the NHS. Health and wellbeing boards, for example, require a representative from clinical commissioning groups (also mentioned in wellbeing 6’s key terms), which are responsible for the delivery of healthcare in England. Wellbeing 2 is related to wellbeing 6 in that it involves expressions about ‘health and wellbeing’, but these expressions tend to be about the health and wellbeing of particular subjects rather than ‘health and wellbeing’ documentation/procedures/organisations. Thus, the key terms of wellbeing 2 relate to mentions of ‘employee health and wellbeing’, ‘safety and wellbeing’, promoting/improving health and wellbeing and so on.

From 2014 onwards wellbeing 5 contributes the most to the growth of ‘wellbeing’, which covers expressions in which ‘wellbeing’ is discussed as something to be improved and as an object of research, e.g. as something measurable (and therefore, improvable), as something that affects other measurable and desired outcomes, as a concept which needs definition, and so on:

-

‘It assesses their potential impact for policy and provides a series of proposals as how to incorporate wellbeing evidence into policy appraisal’ [64]

-

‘Estimate monetary values for those wellbeing impacts using the Wellbeing Valuation approach’ [27]

-

‘The mental health charity Mind launched its Workplace Wellbeing Index earlier this year’ [20].

The focus on ‘wellbeing’ as an object of research is reflected in wellbeing 5’s key terms—e.g. ‘wellbeing valuation’ is the name of a method for pricing the impact of various things upon people’s wellbeing, e.g. the price of the decrease in wellbeing that results from flooding, ‘previous survey’, ‘wellbeing index’, ‘difference comparison’, ‘difference cs’, ‘scale’ all relate to statistical analyses of surveys designed to gather data on wellbeing. Alongside the growth in wellbeing 5 one sees the growth of wellbeing 3 and wellbeing 8 (though wellbeing 8 does not continue to make a large contribution to the overall growth of ‘wellbeing’ from 2018 unlike wellbeing 5 and 3). Both these senses again relate to specialised rather than generic uses of ‘wellbeing’. Wellbeing 3 covers expressions about subjective wellbeing—wellbeing as someone’s own evaluation of the quality of various aspects of their life—and wellbeing 8 covers expressions about wellbeing and mental health.

It is notable that there is some crossover between wellbeing 5 and wellbeing 3 and 8. Wellbeing as an object of research also features as a theme in both wellbeing 3 and 8. Thus, the key terms of wellbeing 3 include bigrams like ‘measures wellbeing’, ‘associated’ (in the context of the expressions of wellbeing 3 this largely relates to mentions of statistical association), ‘slightly higher’ (relating to surveys showing certain categories of people rate their wellbeing as higher than other categories) and so on. Investigating subjective wellbeing as something quantifiable through statistical analyses of surveys underlies many mentions of subjective wellbeing. Similarly, the key terms of wellbeing 8 include bigrams like ‘work feasibility’, ‘feasibility pilot’, ‘evaluation group’, which relate to ‘work feasibility’ studies which are designed to assess the effectiveness of various kinds of programmes (e.g. the Evaluation of the Group Work Psychological Wellbeing and Work Feasibility Pilot is a study which assesses the success/failure of a programme designed to ‘improve employment and wellbeing outcomes for JSA [Job Seekers Allowance] claimants’ [51]). Investigation of the effect of the programmes being tested on participants’ mental wellbeing is a central part of these feasibility studies. Therefore, discussion of wellbeing as something to be improved and research into how to measure/improve wellbeing, in particular discussion of and research into subjective and mental wellbeing, contributes the most to the general increase in the use of ‘wellbeing’ after 2014.

Examination of sense content reveals that the dominant senses underlying periods of target vocabulary diffusion are scattered throughout a great variety of policy activities. There is not a particular kind of policy activity that is especially responsible for a particular word use and is, therefore, particularly responsible for diffusion. This is so even when considering a single sense. Thus, the example sentences of resilience 3 provided above are taken from documents that reflect a very broad range of policy activities—a document that details how the Cabinet Office’s spending helps it achieve its annual objectives [6], a document that details the measures put in place to ensure London’s resilience to emergencies as required by the Civil Contingencies Act [43] and a document that provides local authorities guidance on emergency mutual aid arrangementsFootnote 7 [7]. This suggests that the interpretive acts through which the target vocabulary diffuses are scattered throughout the policy process.

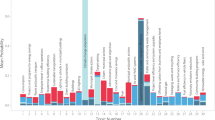

3. Distribution of senses: The distribution of target vocabulary senses across the British government’s departmental division of labour was examined using Chi-square tests upon senses’ frequency distributions. Figure 2 displays the adjusted residualsFootnote 8 gained from running 5 Chi-square tests on the frequency distribution of the senses of each word of the target vocabulary across all departmental categories. The Bonferroni adjusted p-values of the tests were all less than 3 × 10–50. The value in each cell is the adjusted standardised residual of the word in a department. The redder a cell is, the larger the residual is, whilst bluer cells indicate negative valued residuals. Residuals’ p-values were adjusted using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure to control family-wise error rate. The residual with the lowest positive value that was nevertheless significant at a 99% significance level had a value of 2.69, meaning all residuals with a value equal to or greater than 2.69 indicate an observed frequency significantly higher than the expected frequency that a 99% significance level. Such residuals show that occurrences of a sense are much more highly concentrated within a department compared to other departments.

Chi-square test results: each cell displays the adjusted standardised residual of a sense in a department. Red is used to indicate residuals that indicate an observed frequency much higher than the expected frequency, blue for residuals indicating an observed frequency much lower than the expected frequency

These Chi-square tests show that there are particularly strong associations between certain senses and narrow portions of the departmental division of labour. For example, resilience 3—pertaining to the ideas of risk assessment and crisis management codified in the Civil Contingencies Act—is very strongly associated with the Cabinet Office. Another example is sustainability 4Footnote 9—pertaining to notions of long-term profitability (related to the idea of sustainable development) and prudent fiscal/monetary policy (e.g. policy that keeps public sector debt below a certain proportion of GDP)—which is very strongly associated with the Treasury. This says something about the overall diffusion of the target vocabulary. Since this uneven distribution holds for the dominant senses most responsible for diffusion as well as more marginal senses, uneven distribution is not simply a feature of some niche ways of using the target vocabulary that is otherwise an unimportant aspect of target vocabulary diffusion. Rather, diffusion within the departmental division of labour is an inherently uneven process, with most of the uses, including dominant uses, underlying diffusion spreading a great deal in certain sections and very little in other sections.

Discussion

The results are evidence of coordinated interpretation because the aspects of the target vocabulary’s diffusion reflected in the results are the kinds of aspects one would expect to find if coordinated interpretation were at play. Two aspects in particular are suggestive of coordinated interpretation—the uneven-ness of diffusion and the connection between senses and departmental function:

-

1.

If the interpretive acts underlying target vocabulary diffusion were entirely uncoordinated by the departmental division of labour, one would not expect diffusion to be so uneven. There would not be much association between particular senses and particular departmental contexts since what departmental context a term is used in would have no bearing upon how it is used. The sense expressed through a decision to use a term within a departmental context would be as likely to appear in a different departmental context, reflecting a much more even diffusion process, with particular senses spreading in different departmental contexts to a more or less similar extent.

-

2.

The content of both dominant and marginal senses is often connected to the functions of the departments they are most strongly associated with—thus it is unsurprising that resilience 5, given its concern with the psychological resilience of children, is strongly associated with the Department for Education, that sustainability 4, given its concern with fiscal sustainability, is strongly associated with the Treasury, and so on. This gives some insight into what is driving the uneven-ness of the target vocabulary’s diffusion. A policy actor’s decision to use a term in a departmental context is directly informed by their knowledge of what the overall function of a department is, meaning the sense that ends up being expressed by the decision is directly related to departmental function. The uneven-ness of diffusion is a consequence of decisions to use the target vocabulary being adapted to particular departmental functions. If coordinated interpretation had no impact on diffusion, one would not expect to see any connection between sense content and departmental context, again because departmental context would have no bearing upon decisions to use the target vocabulary.

-

2.

Though the above suggests departmental division of labour does, somehow, coordinate the diffusion of the target vocabulary, I have yet to specify a mechanism that explains how this coordination happens. The uneven-ness of diffusion and the connection between sense contents and departmental function suggest judgments of relevance are at the centre of this issue. Someone working for the Department for Education is not going to be predisposed to interpreting and using ‘resilience’ in terms of a national capacity for crisis management, since this would be irrelevant to the Department for Education’s function. By drawing upon the notion of relevance, I now turn to specifying a mechanism which explains how division of labour coordinates the use of the target vocabulary and, therefore, the overall diffusion of resilience, sustainability and wellbeing.

The mechanics of the interplay between judgments of relevance and linguistic interpretation has been extensively considered in relevance theory [59, 67], in which it is argued that interlocutors always interpret the meanings of linguistic expressions in relation to the contextual assumptions they hold. For example, if two interlocutors A and B are having a conversation in which B utters ‘resilience’, A’s interpretation of ‘resilience’ will be shaped by A’s assumptions about the nature of their relationship with B, about the immediate history of the conversation in which B uttered ‘resilience’, and so on. Relevance theory argues that without taking these assumptions into account, there is no way for A to decide which interpretation of ‘resilience’ is the correct one—e.g. to figure out if B is talking about a national capacity for crisis management or the psychological robustness of individuals.

Sperber and Wilson argue that A would figure out the correct interpretation of B’s utterance of ‘resilience’ by selecting the interpretation that would introduce the greatest change to their collection of contextual assumptions C by inferential necessity/licence [67]. This change might be an addition or removal of an assumption to/from A’s collection of contextual assumptions, or a re-evaluation of A’s certainty in the truth/falsehood of their contextual assumptions [59]. Therefore, if A asks B ‘Would raising interest rates to tackle inflation affect the housing market?’ whilst holding the contextual assumption We need to decide whether to raise interest rates or not, and B responds ‘Yes—it would decrease resilience’, A will interpret B’s utterance of ‘resilience’ in the sense of the capacity of the housing market to withstand shocks rather than the sense of individual psychological robustness, since the former allows A to introduce the assumption interest rates cannot be increased without making the housing market more vulnerable, whilst the latter interpretation does not permit any addition to, removal from or re-evaluation of A’s collection of contextual assumptions.

Though I have discussed judgements of relevance in relation to the interpretation of statements, similar relevance-maximising mechanics are at play during actors’ decisions to utter (i.e. saying, writing) particular terms. Interlocutors always have an intended interpretation in mind when making utterances.

Adoption of the relevance theoretic view of interpretation enables a straightforward explanation of how the uneven diffusion of the target vocabulary is generated by the micro-scale interpretive acts of individual policy actors. The contextual assumptions of policy actors are coordinated by the departmental division of labour such that actors within the same departmental context will have a greater number of shared contextual assumptions compared to actors working in different departmental contexts. Any policy actor will have knowledge about their function within an organisation, the overall purpose of the organisation, and this knowledge will inform the contextual assumptions they use to interpret and utter linguistic expressions in a relevance-maximising way. Since policy actors within the same departmental will share a greater number of contextual assumptions, they will have a greater tendency to use the target vocabulary to express similar contents. Thus, particular senses come to be concentrated within particular departmental contexts, and senses strongly associated with a particular department tend to be related with the department’s function.

Knowledge of the function of an organisation and one’s own function within a department is of course not something that is generated by any single policy actor. Unless one has a role in establishing an organisation, such things are known and reinforced only through being directed by other actors working within the same organisation. The formation of policy actors’ contextual assumptions in alignment with the departmental division of labour, which in turn aligns actors’ interpretative acts with the departmental division of labour, is, therefore, a macro-scale process—an organisational coordination of interpretation.

Since interpretation is a cognitive process, the organisational coordination of interpretation is already an example of the organisational coordination of individual cognition. However, coordinated interpretation can be linked to other cognitive processes that have been highlighted by researchers as central to the impact of ideas upon policymaking. One such process is attention allocation. For example, Jacobs [38] notes that ideas correspond to individuals’ simplified ‘mental representations’ of the world. As they are simplified, they work as attention allocation devices—when considering a chair, attention is drawn towards the features of the chair present in one’s mental representation of it (e.g. four legs, a seat and a backrest) and away from the features that are abstracted away (e.g. the chair’s materials, it’s precise dimensions, it’s colours). In policymaking, this means the range of policy preferences considered by decision makers is constrained by what their representations of policy problems and instruments draw attention to and abstract away from. Therefore, when Bismarck first introduced a state pension scheme, this scheme was represented in terms of private insurance. During design of the scheme, attention was repeatedly drawn towards potential problems that are frequently faced by private insurance schemes, e.g. insolvency, and away from potential problems unique to state insurance schemes, e.g. diversion of funds/assets away from insurance towards some other purpose [38]. At an individual scale, ideas influence policymaking through a cognitive process of attention allocation via abstracted mental representations.

What mental representations are instantiated in a policy actor in response to some idea is going to depend upon how the actor interprets the linguistic items that express the idea. Therefore, what mental representations are instantiated in actors on exposure to occurrences of ‘resilience’ is going to depend on how actors interpret specific occurrences of ‘resilience’. Since these interpretations of occurrences of ‘resilience’ would be coordinated at an organisational level, the mental representations instantiated through exposure to occurrences of ‘resilience’ would also be coordinated at an organisational level. A policy actor who interprets an occurrence of ‘resilience’ that appears in the context of the Department for Education will have quite different mental representations instantiated compared to someone who interprets an occurrence of ‘resilience’ that appears in the context of the Cabinet Office. The former situation is more likely to result in mental representations of the psychological robustness of children, the latter is more likely to result in mental representations of the country’s organisational capacity to assess risk and manage crises. Since mental representations work as attention allocation devices, this in turn means that organisational coordination of interpretation doubles as the organisational coordination of individual attention.

Conclusion

Through examination of the collective adoption of resilience, sustainability and wellbeing across the UK government’s departmental division of labour, this paper has sought to produce an account of the collective adoption of policy ideas that explicitly addresses the relation between the micro- and macro-processes involved in collective adoption. I have argued that implicit in the diffusion process behind ideas’ collective adoption is a sociolinguistic process of coordinated interpretation. As a particular idea diffuses amongst policy actors, the micro-scale interpretations of the linguistic items used to express the idea are coordinated by the macro-scale division of labour that organises policy actors. Drawing on relevance theory, I suggest that this happens through the contextual assumptions policy actors have by virtue of being integrated into the organisational structures that constitute divisions of labour. It is the formation of these contextual assumptions that links these micro- and macro-factors. Through the formation of contextual assumptions, macro-scale organisational structure also coordinates other cognitive processes pertinent to the question of how ideas influence policymaking, e.g. the formation of mental representations and corresponding processes of attention allocation.

What arises from all this is a picture of the collective adoption of ideas that avoids the problems of the paradigm perspective and explicitly considers the micro–macro-relations emphasised by critics of the paradigm perspective. The relevance-maximising mechanics inherent in the interpretation and use of the terms used to express ideas results in the internalisation of a heterogeneous collection of functionally specialised conceptual frameworks, e.g. resilience as psychological robustness vs. resilience as a national-organisational capacity for risk assessment and crisis management. Of course, these different conceptual frameworks might be consistent with each other in some situations, but there is nothing within the work of relevance-maximisation that demands consistency.

Beyond providing a theory for how the organisational and cognitive processes involved in the collective adoption of ideas are interlinked, the arguments of this paper have implications for research on the impact of ideas in policymaking, in particular the role polysemy plays on the effect of ideas on policy outcomes.

Current research on polysemy and the impact of ideas [1, 3, 11, 23, 30, 33] tends to approach ideas from a psychological/cognitive perspective. Thus, work on the role of polysemy in policy change often takes ideas to be subjective beliefs [3], relating them to the core and secondary beliefs of policy actors emphasised in the Advocacy Coalition Framework [30, 33, 55]. The studies mentioned in this paper that have explicitly drawn upon cognitive psychology to understand the impact of ideas on policymaking further reflect this tendency.

This tendency has obscured the linguistic aspect of using ideas, preventing such research from examining how polysemy arises from language use within organisational structure, and therefore, how the range of policy outcomes that might arise from the collective adoption of an idea depends on the type of organisational structure into which it is adopted. Thus, whilst researchers have produced fruitful descriptions of what policy outcomes have resulted from the polysemy surrounding particular ideas (e.g. the policy outcomes produced by the polysemy surrounding the Europe of Knowledge idea [11]), how policy entrepreneurs exploit polysemy to build coalitions that can push policy outcomes based on a particular idea [3], a more general account of how the range of policy outcomes that might result from the adoption of an idea is influenced by the relation between organisational structure and polysemy has not been produced.

The sociolinguistic framework of this paper can be used as a starting point for producing a more general account. This paper has dealt with a very small aspect of the government’s total division of labour. The sociolinguistic approach used here can be used for further analyses of the polysemy generated by the adoption of ideas into other kinds of divisions of labour, for example, the hierarchical and regional divisions of labour between central departments, non-ministerial bodies, agencies and local authorities, the division between international (e.g. International Monetary Fund), transnational (e.g. European Union) and national governance organisations, and so on. This would further enable analysis of how the polysemy of an idea varies across these different kinds of divisions of labour, in turn enabling analysis of how the range of policy outcomes that result from the adoption of an idea also varies according to the polysemy generated by different divisions of labour. Such analyses would provide the empirical basis for a more general theory of organisational structure, polysemy and policy outcomes.

Data availability