Key summary points

To map challenges related to the transition of citizens from hospital to temporary care at a skilled nursing facility in relation to medication management, responsibility of medical treatment, and communication.

AbstractSection FindingsHalf of the citizens possessed all medication needed for further dispensing when they arrived at the skilled nursing facility. The nurses conducted in median three telephone calls and sent in median two correspondences per citizen.

AbstractSection MessageA third of contacts related to medication management were avoidable with improved practices around communication.

Abstract

Purpose

With decreasing number of hospital beds, more citizens are discharged to temporary care at skilled nursing facilities, requiring increasingly complex care in a non-hospital setting. We mapped challenges related to the transition of citizens from hospital to temporary care at a skilled nursing facility in relation to medication management, responsibility of medical treatment, and communication.

Methods

Descriptive study of citizens discharged from Odense University Hospital to temporary care from May 2022 to March 2023.

Results

We included 209 citizens (53% women, median age 81 years). Most citizens (97%; n = 109/112) had their medication changed during hospital admission. Citizens used a median of eight medications, including risk medications (96%, n = 108). Medication-related challenges occurred for 37% (n = 77) of citizens and most often concerned missing alignment of medication records. Half of citizens (47%, n = 99) moved into temporary care with all medication needed for further dispensing. Nurses conducted in median three telephone calls (interquartile range [IQR 1–4]) and sent in median two correspondences (IQR 1–3) per citizen within the first 5 days. Nurses most often called the hospital physician (41% of telephone calls, n = 265/643) and sent correspondences to the general practitioner (55% of correspondences, n = 257/469). For 31% (n = 29/95) of citizens requiring action from nursing staff, this could have been avoided if the nurses had had access to the discharge letter.

Conclusion

We identified several challenges related to the transition of patients from hospital to temporary care, most often related to medication. A third of actions related to medication management were considered avoidable with improved practices around communication.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Temporary care beds outside the hospital are critical subsystems in modern healthcare systems, providing short-term care and rehabilitation for patients, most often following hospital admissions [1]. These beds are increasingly important as the aging population continues to grow, placing greater demands on healthcare systems worldwide [2]. Temporary care beds can help alleviate the pressure on hospitals, freeing up resources for more urgent cases while providing patients with the necessary care and support to aid their recovery.

The high throughput of increasingly complex and frail patients into temporary care beds [3,4,5] constitutes a challenge for healthcare providers [4]. One of the primary issues faced is communication with other parts of the healthcare system, including hospitals, primary care providers, and long-term care facilities [6,7,8,9]. Effective communication is essential for ensuring continuity of care and avoiding adverse events such as medication errors, readmissions, and delays in care [7, 10, 11]. The challenges posed by communication breakdowns in the healthcare system can lead to negative outcomes for patients [11, 12] and increase the burden on healthcare providers [13, 14].

To improve care for the growing population of older people, it is essential to understand the challenges associated with the transfer of patients from the hospital to temporary care. In this study, we aimed to describe and systematically map these challenges related to the transition of patients from hospital to temporary care at a skilled nursing facility (SNF) in relation to medication management, responsibility of medical treatment, and communication.

Methods

We conducted an observational study describing challenges related to the transition of patients being discharged from either a medical or surgical department at a large tertiary university hospital to short-term temporary care at a SNF.

Setting

The study was conducted at Odense University Hospital and the SNF “Lysningen”, both located in the Region of Southern Denmark.

Odense University Hospital is a large tertiary university hospital with 965 beds, receiving patients mainly from Funen (approx. 500,000 citizens). The hospital discharges approx. 100,000 patients per year and has 42 medical and surgical departments. Of these, 19 discharges patients to “Lysningen” and were thus included in this study.

“Lysningen” is a SNF located in Odense Municipality. It is a large tertiary care center with 64 temporary care beds which provides care and treatment to patients who, following an admission, are not well enough to return to their home. Citizens are referred to such a stay by their municipality, based on a suggestion from the hospital in relation to discharge. Care is provided by nurses, healthcare assistants, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, and pharmaconomists. Politically, there are no demands of physicians in permanent positions at SNFs in Denmark [5]. Thus, medical treatment and changes to this is managed by the hospital physician during hospital admission, while it is the citizens’ general practitioner, i.e., the primary care setting, who is responsible for treatment and medication changes in the SNF. Care providers at “Lysningen” only get the discharge notice from the hospital nurses and not the discharge letter from the hospital physician. To prevent information gab, a phone call between a nurse from the SNF and a nurse from the hospital, coordinating citizens’ needs of care and treatment as well as practicalities before discharge, is made. Citizens are responsible themselves for bringing medication needed for further dispensing following the first 24 h after hospital discharge. The capture area for “Lysningen” is citizens from Odense Municipality (approx. 200,000 citizens).

Study design

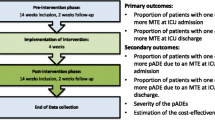

The study was an observational study conducted in a two-step design.

The first step provided a preliminary mapping and categorization of challenges related to the transition of patients from hospital to temporary care. A clinical pharmacist (LVRN) followed and observed nurses’ and pharmaconomists’ (comparable to a pharmacy technician, although with an education of 3 years) way of handling contacts to hospital physician, general practitioner, community pharmacy, and others involved in treatment and care, such as relatives, for 11 citizens, after which knowledge saturation was established (i.e., where no further information was obtained). The findings were discussed with a steering group supporting the study, comprising a general practitioner and a consultant from Odense Municipality, a consultant and a PhD student in emergency medicine from Odense University Hospital as well as a nurse from and the head of “Lysningen”. The project and steering group decided to further explore challenges related to medication management, responsibility of the medical treatment, and communication. For each of the three categories, factors associated with challenges related to the transition of patients from hospital to temporary care were identified among the project and steering group (as described in the data collection section).

The second step consisted of mapping the patients’ way through the system by a comprehensive systematic registration and categorization of the challenges described in the first step.

Patients

Patients discharged from all discharging bed departments of Odense University Hospital were enrolled in the study. Patients were eligible if they were aged 18 years or above and could provide written informed consent. Initially, patients with dementia or other cognitive impairment were excluded because of inability to give consent. However, following approval from the Regional Council of Southern Denmark on October 17, 2022, these patients were included without providing written informed consent. Patients were censored if they left the SNF within 5 days of hospital discharge. This could be due to either being readmitted to the hospital, leaving by own choice, or dying. Based on the daily number of patients discharged from Odense University Hospital to “Lysningen” as well as the time limit of the study, we aimed for inclusion of 200 patients as this was considered feasible and sufficient to show any important tendencies.

Data collection

Data collection took place from May 10, 2022 to March 10, 2023 and included consecutively discharged patients, hereafter referred to as citizens. Data were collected by trained pharmaconomists (MN and SG). For consistency, both data collectors were trained by the pharmacist carrying out the initial phase of the project. This entailed that the pharmaconomists followed the pharmacist during mapping of challenges for four citizens. Following this, the pharmaconomists had audit training sessions with the pharmacist. Data were collected every day between 8 am and 3 pm (weekends excluded) and were registered for the first 5 days of each citizen’s stay at the SNF. Data were collected from review of records in the interdisciplinary system NEXUS used in Odense Municipality as well as from consultation with the nurses and pharmaconomists working in the SNF. The following information was collected for each citizen: demographics, medication status, discharging department, residential information, medication administration status, level of function, changes of medication, number of telephone calls, electronically sent correspondences and to whom these were addressed, and an assessment of whether the required contacts could have been avoided if the nurses had had the discharge letter from the hospital physician and not only the usual discharge notice from the nurses. The medication list (excluding vitamins and nutritional supplements) was evaluated by number of changes during hospitalization and analyzed based on information from the Shared Medication Record and the electronic patient record. Risk medications were categorized inspired by Pirmohamed et al. [15] and modified to present medications available in Denmark. All data were processed in the online-based Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) system [16].

Statistics

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze patient characteristics and the quantitative outcomes. All analyses were performed using Stata 17 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Ethics approval

Patient capable of providing written informed consent was included on this basis. Patients with dementia and other cognitive impairment were included without written informed consent after approval from the Regional Council of Southern Denmark (record no. 21/67763) on October 17, 2022. These citizens’ relatives were informed of the inclusion and had the opportunity to object. Before this date, these citizens were excluded. The study was registered in the Region of Southern Denmark’s repository (record no. 22/48161). The Regional Committee on Health Research Ethics waived registration (record no. 21/35007) due to the study design.

Results

A total of 297 citizens were invited to participate in the study, of which 209 were included (Fig. 1).

Following inclusion, nine citizens were censored during follow-up, of which five died during the first five days of their stay at the SNF, three were readmitted to the hospital, and one regretted their stay and went home.

Half of all included citizens (53%; n = 111) were women and the median age was 81 years (interquartile range [IQR 74–86]) (Table 1).

One in five citizens (19%; n = 39) had dementia or otherwise impaired cognition. Citizens were mainly discharged from either the Geriatric Department (22%; n = 45), Neurological Department (17%; n = 36), or Orthopedic Department (13%; n = 28).

Around half of citizens were transferred to the SNF on weekdays before 3 pm (54%, n = 112), with the remaining being transferred after 3 pm (46%, n = 97). Monday was the most frequent weekday for transfer (24%, n = 50). One in ten citizens (11%, n = 24 of 209) were transferred on either Friday after 3 pm or during the weekend.

Medication management

The majority (97%; n = 109/112) of citizens had their medication changed during hospital admission before arrival at the SNF. Most citizens (86%; n = 96) had one or more (median 2.9 [IQR 1–4]) new medications started, 23% (n = 26) had one or more (median 0.3 [IQR 0–0]) medications stopped, and 97% (n = 109) had changes in strength or dose to one or more (median 4.9 [IQR 3–7]) medications (data not shown).

Citizens were discharged from the hospital and arrived to the SNF with a median of eight medications (IQR 5–11) (Table 2).

The majority of citizens (96%, n = 108) used at least one risk medication at time of arrival. The most common risk medications were diuretics (48%; n = 54), opioids (47%; n = 53), and anticoagulants (46%; n = 51). A sub-analysis for the group of citizens with impaired cognition showed no difference in relation to medication use (data not shown).

For almost all citizens (99%; n = 207), the medication provided by the hospital to the SNF was used during the first day. For 37% (n = 77) of citizens, there were problems related to the medication provided, most often due to missing update of the Shared Medication Record, change in strength of medication, missing or unidentified medication, or other discrepancies. Further, during the first day only half of citizens (47%; n = 99) either brought or were brought all medication needed for further dispensing for the first week and further during their temporary care stay.

Responsibility of medical treatment

The type of healthcare-related contacts or visits are presented in Fig. 2.

Number of citizens that need to contact or received a visit from a health-care provider at the skilled nursing facility, within the first 5 days. Type of healthcare provider is specified to general practitioner, on-call general practitioner, number of hospital readmissions, and acute team from hospital or geriatric nurse or a geriatrician from hospital. Some citizens received multiple visits or contacts per day but is only represented once in this figure

During the first 5 days, the general practitioner visited 4% (n = 8) of citizens, the on-call general practitioner was contacted for 13% of citizens (n = 27), while the municipal acute team or acute admission department was contacted for 15% of citizens (n = 31). Fourteen percent (n = 28) had a follow-up visit from a geriatrician from the hospital and 5% (n = 10) of citizens were readmitted.

The citizens with impaired cognition had a similarly prevalence of contacts or visits within the first 5 days at the SNF (data not shown).

Communication

The nurses conducted in median three (IQR 1–4) telephone calls and sent in median two electronically correspondences (IQR 1–3) per citizen about medication within the first 5 days (Table 3).

Most telephone calls and correspondences were made on the second day (data not shown). It was primarily the hospital physician who was called and the general practitioner to whom the correspondences were addressed (Table 3). The contacts primarily concerned medication (Table 3). Coordinating telephone calls between the hospital nurse and the nurse from the SNF before hospital discharge were made for all 209 citizens.

We assessed 83% (n = 169 of 204) cases with discrepancy between the discharge notice from the nurses and the discharge letter, most often related to medication. In half (53%; n = 109 of 204) of cases with discrepancy, no action defined as phone call or correspondence was needed from the SNF to provide care and treatment. However, for 31% (n = 29 of the 95) of citizen records that required action from the SNF, it was estimated that the action could have been avoided if the nurses from the SNF had had the discharge letter.

A sub-analysis for the group of citizens with impaired cognition showed no difference in relation to communication (data not shown).

Discussion

We identified cross-sectorial challenges related to the transition of patients from hospital to temporary care at a SNF. Citizens moving into temporary care used multiple medications, most often including risk medications. Cross-sectorial challenges most often concerned lack of needed medication for dispensing at the SNF, meaning that the nurses at the SNF had to repeatedly contact primary care and hospital physicians. A third of all actions related to medication management could have been avoided with improved communication, with nurses at the SNF having access to the necessary information acquired from the journals, particularly the discharge letter.

Citizens arrived at the SNF with a median of eight medications which is similar to a study from the US [17]. Further, most citizens were treated with risk medications [15] as seen in another Danish study with similar older citizens [18]. Risk medications make these citizens a vulnerable group with high risk of hospital admissions [19].

In Denmark, we use the Shared Medication Record which is a personal profile for the individual citizen that provides full access to current medication, updated by the physician who last treated the citizens [20]. Unfortunately, this record is not always updated. The findings from our study are aligned with discrepancies reported in other studies [21, 22]. The resulting recurrent contacts to hospital or general practitioner are very time-consuming for the nurses at the SNFs. Furthermore, uncertainty about whether it is the right medication or not can compromise patient safety and lead to considerable frustration for the healthcare providers [23]. Alignment of medication currently often requires involvement of relatives as medication being obtained is based on the resources and availability of the relatives rather than the IT system and organizationally workflows.

The nurses from the SNF called the hospital physician mostly on the second day of the citizens stay. This is likely explained by the fact that 40% of patients arrived after 4 pm, i.e., where the staffing is lower, and the general practitioners are unavailable. The timing of discharge and transition to the SNFs was also highlighted as a problematic theme in recent a qualitative study [24]. Further, the telephone calls on the second day supports the national Danish decision of the responsibility of the citizens’ treatment being upheld by the hospital for 72 h after discharge. At the time of the study, this was not implemented in the region where the study took place. There were no physicians at this SNF, which is why the general practitioners and hospital physicians were contacted. Further, implementation of designated general practitioners at care homes in Denmark has been shown to reduce the number of acute admissions, short-term admissions, and readmissions [25], while it also contributes to more clear, precise, and timely communication between care homes and the general practitioner [26] This indicates that it could be worth trying to have a designated general practitioner at the SNFs in Denmark. Finally, geriatric follow-up has been shown to reduce unplanned hospital readmissions in a similar study population [27]. In our study, six of ten citizens had a follow-up visit from a geriatrician, potentially preventing citizens from being readmitted to the hospital.

Four out of five citizens had one or more discrepancies between the discharge notice from the nurses at the hospital and the discharge letter. These discrepancies covered missing information about medication, changes of dose, time for treatment, control of blood samples, etc. As estimated, a significant proportion of all telephone calls and correspondences from the SNF to general practitioners and hospitals related to such missing information. This indicates that shared information, where the nurses at the SNF could access all the information from the electronic patient journal from the hospital, would be valuable. Specifically, the nurses should systematically receive the discharge letter with medical changes described. Several solutions to improve medication changes at transitions have been demonstrated [18, 28, 29]. Potential strategies for improving communication and patient care may as well be addressed in a future study.

Among the principal strengths of our study is its fairly large size and the possibility to access data across sectors and different systems, thus enabling us to achieve valid data. Second, this study includes citizens with dementia and other cognitive impairments, although only for a part of the study period. Several limitations to our study should also be acknowledged. First, citizens were only included once, even if the citizens had several hospital admissions and subsequently stays at the SNF. When several subsequent transfers occur across healthcare sectors it can result in more complications related to continuation of changed medications, lack of information, etc., which might result in an even higher need for the nurses at the SNFs to contact hospital and general practitioners. Second, number of telephone calls and electronic correspondences were based on recollection by SNF staff or registrations in journals. However, the healthcare staff is very busy, and it is possible that not all contacts were reported, hereby leading to an underestimation of the number of contacts. Third, the heterogeneous study population includes not only older citizens but also a few younger and homeless citizens with, e.g., psychical illness and abuse. This heterogeneity makes it difficult to generalize the results. Finally, we collected data from one municipality with one SNF, which might also limit generalizability.

Generally, the outcome of a temporary stay is questioned in another Danish study which found varying effect [30], and the organization is of great political interest in these years, questioning how the citizens get the best treatment with most value for money.

Conclusions

Most citizens experienced polypharmacy, most often including risk medications, when transitioning into temporary care at the skilled nursing facility. We identified challenges related to particularly lack of needed medication and found that the nurses from the SNF had to contact hospital physicians and primary care repeatedly, particularly on the second day. A third of the actions related to medication management were considered avoidable with improved practices around communication.

Data availability

Data can be shared upon contact to the corresponding author and upon achieving the necessary approvals.

References

Werner RM, Coe NB, Qi M et al (2019) Patient outcomes after hospital discharge to home with home health care vs to a skilled nursing facility. JAMA Intern Med 179:617–623

Werner RM, Konetzka RT (2018) Trends in post-acute care use among medicare beneficiaries: 2000 to 2015. JAMA 319:1616–1617

Delara M, Murray L, Jafari B et al (2022) Prevalence and factors associated with polypharmacy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr 22:601

The Academy of Medical Science (2018) Multimorbidity: a priority for global health research [Internet]. Available from: https://acmedsci.ac.uk/file-download/82222577

Vinge S, Buch MS, Kjellberg PK (2021) The municipal emergency area: experiences and perspective on the development from 15 municipalities - VIVE.dk (In Danish: Det kommunale akutområde - Erfaringer og perspektiver på udviklingen fra 15 kommuner). [Internet]. The Danish National Center for Social Science Research (Denmark). Available from: https://www.vive.dk/media/pure/ozono7vn/5709970

Adler-Milstein J, Raphael K, O’Malley TA et al (2021) Information sharing practices between us hospitals and skilled nursing facilities to support care transitions. JAMA Netw Open 4:e2033980

Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO et al (2007) Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA 297:831–841

Vermeir P, Vandijck D, Degroote S et al (2015) Communication in healthcare: a narrative review of the literature and practical recommendations. Int J Clin Pract 69:1257–1267

Cam H, Wennlöf B, Gillespie U et al (2023) The complexities of communication at hospital discharge of older patients: a qualitative study of healthcare professionals’ views. BMC Health Serv Res 23:1211

Strehlau AG, Larsen MD, Søndergaard J et al (2018) General practitioners’ continuation and acceptance of medication changes at sectorial transitions of geriatric patients - a qualitative interview study. BMC Fam Pract 19:168

Parekh N, Ali K, Page A et al (2018) Incidence of medication-related harm in older adults after hospital discharge: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc 66:1812–1822

Zurlo A, Zuliani G (2018) Management of care transition and hospital discharge. Aging Clin Exp Res 30:263–270

Adelman RD, Tmanova LL, Delgado D et al (2014) Caregiver burden: a clinical review. JAMA 311:1052–1060

Søndergaard E, Willadsen TG, Guassora AD et al (2015) Problems and challenges in relation to the treatment of patients with multimorbidity: general practitioners’ views and attitudes. Scand J Prim Health Care 33:121–126

Pirmohamed M, James S, Meakin S et al (2004) Adverse drug reactions as cause of admission to hospital: prospective analysis of 18 820 patients. BMJ 329:15–19

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R et al (2009) Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 42:377–381

Hoel RW, Giddings Connolly RM, Takahashi PY (2021) Polypharmacy management in older patients. Mayo Clin Proc 96:242–256

Ravn-Nielsen LV, Duckert M-L, Lund ML et al (2018) Effect of an In-hospital multifaceted clinical pharmacist intervention on the risk of readmission: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 178:375

Montero-Odasso M, van der Velde N, Martin FC et al (2022) World guidelines for falls prevention and management for older adults: a global initiative. Age Ageing 51:205

Munck LK, Hansen KR, Mølbak AG et al (2014) The use of shared medication record as part of medication reconciliation at hospital admission is feasible. Dan Med J 61(5):A4817

Bülow C, Noergaard JDSV, Færch KU et al (2021) Causes of discrepancies between medications listed in the national electronic prescribing system and patients’ actual use of medications. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 129:221–231

Kerstenetzky L, Birschbach MJ, Beach KF et al (2018) Improving medication information transfer between hospitals, skilled-nursing facilities, and long-term-care pharmacies for hospital discharge transitions of care: a targeted needs assessment using the intervention mapping framework. Res Soc Adm Pharm RSAP 14:138–145

Grissinger M (2017) Disrespectful behavior in health care. P & T 42:74–77

Gadbois EA, Tyler DA, Shield R et al (2019) Lost in transition: a qualitative study of patients discharged from hospital to skilled nursing facility. J Gen Intern Med 34:102–109

Christensen LD, Vestergaard CH, Christensen MB et al (2022) Health care utilization related to the introduction of designated GPs at care homes in denmark: a register-based study. Scand J Prim Health Care 40:115–122

Christensen LD, Huibers L, Bro F et al (2023) Interprofessional team-based collaboration between designated GPs and care home staff: a qualitative study in an urban danish setting. BMC Prim Care 24:3

Thomsen K, Fournaise A, Matzen LE et al (2021) Does geriatric follow-up visits reduce hospital readmission among older patients discharged to temporary care at a skilled nursing facility: a before-and-after cohort study. BMJ Open 11:e046698

Achilleos M, McEwen J, Hoesly M et al (2020) Pharmacist-led program to improve transitions from acute care to skilled nursing facility care. Am J Health Syst Pharm 77:979–984

Sibicky SL, Pogge EK, Bouwmeester CJ et al (2024) Pharmacists’ impact on older adults transitioning to and from patient care centers: a scoping review. J Pharm Pract 37:169–183

Strøm C, Stefansson JS, Fabritius ML et al (2018) Hospitalisation in short-stay units for adults with internal medicine diseases and conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012370.pub2

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Lisbeth Muurholm, Head of Hospital Pharmacy Funen, Odense University Hospital and Kristine Kolberg Madsen, Head of the skilled nursing facility “Lysningen”, Odense Municipality who ensured the organizational base for conducting this study. Further, we would like to acknowledge the steering group supporting the study, including Rasmus Dahl (general practitioner, Odense Municipality), Lene Annette Norberg (consultant, Odense Municipality), Annmarie Touborg Lassen (consultant, Emergency Medicine Research Unit, Odense University Hospital), Stine Emilie Udesen (PhD student, Emergency Medicine Research Unit, Odense University Hospital) and Tanja Julie Jensen (nurse, “Lysningen”, Odense Municipality), as well as all involved nurses and pharmaconomists from “Lysningen” and all participating patients. Finally, we like to acknowledge Open Patient data Explorative Network (OPEN), Odense University Hospital, Region of Southern Denmark for ensuring access to and counseling about registration of data in the online-based Research Electronic Data Capture system (REDCap).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Odense University Hospital. This work was supported by the Public Health Research Fund of the Region of Southern Denmark [Grant number 1186].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Lene Vestergaard Ravn-Nielsen, Carina Lundby and Anton Pottegård obtained funding and contributed to study concept and design. Lene Vestergaard Ravn-Nielsen, Stine Galsgaard and Marianne Nielsen acquired data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data. Emma Bjørk and Anton Pottegård performed the statistical analysis and take responsibility for the accuracy of the data analysis. Emma Bjørk, Lene Vestergaard Ravn-Nielsen, Carina Lundby and Anton Pottegård interpreted data. Lene Vestergaard Ravn-Nielsen drafted the manuscript and all the authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and read and approved the final version of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The study was registered in the Region of Southern Denmark’s repository (record no. 22/48161). The Regional Committee on Health Research Ethics waived registration (record no. 21/35007) due to the study design.

Informed consent

Patient capable of providing written informed consent was included on this basis. Patients with dementia and other cognitive impairment were included without written informed consent after approval from the Regional Council of Southern Denmark (record no. 21/67763) on October 17, 2022. These citizens’ relatives were informed of the inclusion and had the opportunity to object. Before this date, these citizens were excluded.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ravn-Nielsen, L.V., Bjørk, E., Nielsen, M. et al. Challenges related to transitioning from hospital to temporary care at a skilled nursing facility: a descriptive study. Eur Geriatr Med (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-024-01003-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-024-01003-z