Abstract

Purpose

Malnutrition is a condition which is highly prevalent, especially in older persons. Physicians play an important role in multidisciplinary nutritional management, but often feel inadequately prepared to provide nutritional information/therapy to their patients. The aim of this study was to gather information on curricular content on malnutrition in older persons in basic study programs for medical doctors.

Methods

We selected a cross-sectional study design and used a Web-based online survey. We emailed the Web link to those persons responsible for curriculum development at 310 medical schools in 31 European countries.

Results

A total of 26 (8.4%) medical schools in 12 European countries completed the questionnaire. The topic of malnutrition in older adults was included as part of the medical students’ curricula at 50.0% (13 out of 26) of the participating institutions. Most commonly topics taught in the institutions were causes of malnutrition (13, 50%), assessment of malnutrition (13, 50%) and consequences of malnutrition (12, 46.2%). The topic of malnutrition screening was addressed in nine (35%) of the institutions.

Conclusions

Based on our results, we strongly recommend including the topic of malnutrition in older adults in the undergraduate curricula of medical students in Europe. A special focus should be placed on multidisciplinary cooperation. Integrative teaching that targets all professional groups could be one option. Initiatives need to be carried out to create a higher level of awareness and promote improvements in nutrition education for medical doctors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Malnutrition represents a highly relevant geriatric syndrome in older people, along with frailty, immobility, falls, incontinence or cognitive impairment [1, 2]. Age-related changes, such as impaired senses of taste and smell, an increase in the number of satiety signals, or numerous chronic diseases and, thus, multiple drug use, may lead to reduced food intake. In addition, social factors such as loneliness or life-changing experiences like the loss of a partner may decrease nutritional intake and lead to malnutrition [2, 3]. The prevalence of malnutrition in older adults, which ranges between 5 and 50%, depends on the setting as well as the instrument used to assess malnutrition [4,5,6]. Negative consequences of malnutrition are well documented in the literature, including a higher risk of infections, poor rates of wound healing, increased lengths of hospital stays, diminished quality of life and even increased mortality [7,8,9].

Health-care staff must strive to achieve good health outcomes for older people and prevent and treat malnutrition by providing adequate nutrition [10]. Malnutrition can successfully be prevented and treated if evidence-based interventions are conducted, as, for example, summarized in the ESPEN (European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism) guidelines on clinical nutrition and hydration in geriatrics [10]. Nutritional awareness and knowledge are prerequisites, however, for the implementation of these recommendations [11,12,13].

Dietitians/nutritionists are well-trained experts in nutrition and are uniquely qualified to coordinate nutritional therapy based on the Nutrition Care Process in all health-care settings [10, 13]. However, other health-care professionals, including physicians, nurses and therapists, should also be involved in nutritional care, made aware of nutritional problems and know the (basic) principles of nutritional therapy. This allows them to address nutritional challenges in older people, take adequate prevention steps and provide treatment for older persons with (a risk of) malnutrition within the multidisciplinary team [14, 15].

Physicians play a special role in multidisciplinary nutritional management. In most European countries, physicians are responsible for prescribing nutritional therapy and referring patients to dietitians. In addition, they are responsible for providing their patients with correct and evidence-based nutritional information [16]. If physicians have a firm foundation of knowledge in the field of nutrition and display a positive attitude toward the topic, it can be assumed that they are more likely to initiate nutritional therapy and refer to or consult a dietitian and at an earlier stage [13].

Physicians in the clinical practice often feel incompetent and inadequately prepared to provide nutritional information/therapy to their patients [17]. This may be because they receive little education about nutrition during their undergraduate education. If medical doctors do not feel comfortable discussing nutritional topics, they are unlikely to recognize patients who are at risk of malnutrition, provide nutritional information to their patients, or refer them to a nutritional expert. This is regrettable, since patients rely on medical doctors and view them as trustworthy sources of reliable health information.

The undergraduate education is the basis of the daily working life for many physicians [16]. Unfortunately, the integration of nutrition topics into the curricula of medical students is poor, and there are many barriers to including nutrition training in these curricula. These barriers include negative attitudes toward the role of nutrition as compared to medical interventions, the unrecognized importance of nutrition in medicine, or already overfilled curricula [11, 18].

In recent years, some surveys were carried out to elucidate the extent of nutrition education in medical schools. A survey conducted in US medical schools in 2006 and updated in 2010 was identified [19, 20]. In 2010, nearly all educational institutions that completed the survey (103 out of 109) stated that they provided some form of nutrition education. Of these medical schools, 25% stated that they provided a course dedicated to the topic of nutrition for their students. The average amount of time spent on nutrition content was 22.3 h over the complete educational period [19].

In a European survey about nutrition education carried out in 32 European medical schools in 14 European countries [21], 68.8% of the respondents stated that nutrition education is required in some form in their curriculum. The average amount of time spent on nutrition content was 23.7 h over the complete educational period [21]. ESPEN recently conducted a worldwide survey in 29 countries (Europe, Asia, South America, Australia) to determine the extent and content of clinical nutrition education offered to medical students [22]. Of the 56 participating institutions, 73.3% of the respondents reported that they provided obligatory education on clinical nutrition; however, in only 55% of the institutions, education on clinical nutrition was mandatory. The extent of clinical nutrition was more than 8 h in 72% of the medical schools, while it was less in 28% [22].

Taken together, these results show that not all medical schools provide nutrition education, and if education on nutrition is provided, it is taught as an aside and is not specifically identified in the curricula. Concurrently, most of the educators and students surveyed indicated that the amount of nutrition education offered was inadequate [19, 21, 22].

However, as stated above (the risk of developing), malnutrition is especially relevant in older adults. The above-mentioned surveys placed a general focus on education in nutrition, but not specifically on nutrition education in older persons. Up until now, there has been no indication in the literature if and to which extent the topic of malnutrition, and specifically malnutrition in older adults (where its prevalence is highest), is addressed in medical curricula.

For this reason, we aimed at gathering information on curricular content on malnutrition in older persons that are present in basic study programs for medical doctors.

Methods

We selected a cross-sectional study design and used a Web-based online survey that consisted of 15 questions. We then sent the Web link by e-mail to those persons responsible for curriculum development at 310 medical schools in 31 European countries. These persons at all institutions were asked to complete the questionnaire (in the English language) and send the curriculum of their nutrition courses to the authors. To increase the response rate, we kept the questionnaire as short as possible (5–10 min to complete), used a special university e-mail address, distributed the online survey link with the help of local medical associations (cover letters were written in the target language of the country) and sent our study results to the participating universities after the study was completed. Data analysis was carried out by using SPSS. The details of the methods have been published elsewhere [14].

Results

A total of 26 (8.4%) out of the 310 identified medical schools in 12 European countries completed the questionnaire: Italy (1), Belgium (1), Poland (1), Portugal (1), Switzerland (1), Finland (2), Germany (2), Sweden (2), Hungary (3), Ireland (3), the Netherlands (3) and Lithuania (6). Although we sent out reminders, no responses were received from institutions located in Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Denmark, UK, Estonia, France, Greece, Iceland, Latvia, Luxemburg, Malta, Norway, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, or Spain. No educational institution sent us their curriculum (i.e., non-compliance with second request); therefore, it was not possible to conduct a content analysis of the curricula.

Of the 26 responding institutions, respondents from 20 (76.9%) institutions stated that they offered nutrition education. In 12 (60%) institutions, nutrition education was listed as a mandatory part of the medical curricula, whereas 8 (40%) institutions presented it as optional. Fourteen (53.9%) institutions provided lectures during the first year. Twelve (46.2%) provided nutrition education during the 2nd year; 16 (61.5%), during the 3rd year; 13 (50%), during the 4th year; and 13 (50%), during the 5th year of the respective education programs (see Table 1). The amount of time allocated to nutrition education was usually less than 5 h/year, but three institutions (11.5%, in Finland, Poland and Ireland) provided more than 25 h of education during the first year of nutrition education (see Table 1).

In 42.3% of all participating institutions (11 out of 26), the survey results indicated that the topic of malnutrition in older adults was taught by physicians. Dietitians held lectures on this topic in 19.2% (5 out of 26), nurses in 7.7% (2 out of 26) and nutritional scientists in 7.7% (2 out of 20) of the institutions.

The topic of malnutrition in older adults was included as part of the medical students’ curricula at 50.0% (13 out of 26) of the participating institutions.

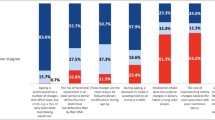

Regarding the content of malnutrition education, the most commonly mentioned topics regarding malnutrition in older persons were: causes of malnutrition (13, 50%), assessment of malnutrition (13, 50%) and consequences of malnutrition (12, 46.2%). The topic of malnutrition screening was addressed in nine (35%) of the institutions. Nutrition support in older patients admitted to intensive care units (ICU) was rarely reported (4, 15.4%). Perioperative nutrition (7, 29.6%) or cooperation in multidisciplinary nutrition support teams (8, 34.6%) and the responsibilities of various professionals in nutritional support (8, 34.6%) were also infrequently included topics (Table 2).

Discussion

The results of this online survey show that it is challenging to collect conclusive data about the curricular content from European medical universities. Representatives from only 26 out of 310 universities that were contacted completed the questionnaire, and we did not receive any curricula, although we made great efforts to increase the response rate [14]. For example, we asked representatives of medical associations in the respective European countries to deliver the survey link to the institutions. In some countries, the associations supported us by writing a short cover letter in the respective language of the countries. We also sent reminders by e-mail and used an official e-mail address that had been specially created for the study, since this has been shown in other studies to improve the response rate [14].

It is necessary to reflect on strategies to increase response when planning similar surveys in the future. Using existing contacts to other universities may prove to be advantageous. One possibility could be directly contacting the responsible persons in advance and explaining the aim of the survey [23]. In general, online surveys achieve about 10% lower response rates than telephone surveys [24]. Therefore, using the method of a telephone survey may result in a higher rate of completed questionnaires.

In light of the low response and feedback rate we achieved with our online survey, we could presume that the representatives contacted at the medical universities have limited or no interest in nutrition education, but this may not necessarily be the case. The low response rate also created a bias in our results. For this reason, the results could not be generalized to other populations, but still have the potential to provide important insights. Because we did not receive any curricula from the educational institutions, we could not objectively assess the content of the curricular courses on nutrition. This would have allowed us to collect important and valid data. We presume that representatives of institutions that have a vested interest in nutrition were more likely to respond, potentially creating a bias in our results. According to the data that could be collected, we assume that the proportion of nutrition education in the medical curricula is still limited.

In the USA, the National Academy of Sciences recommends 25 minimum contact hours for nutrition education for medical students [25, 26]. The American Society for Nutrition even recommends 44 minimum contact hours [27]. To our knowledge, such recommendations do not exist for Europe [22]. Although our survey sample did not allow us to identify the exact number of teaching hours devoted to nutrition education, we revealed that most of the universities provided either no or fewer than 5 h of nutrition education per year (see Table 1). These results lead us to conclude that nutrition education—if it exists at particular institutions at all—still makes up a minor part of the physicians’ curricula.

Malnutrition is a condition, which is highly prevalent, especially in older persons, and is therefore recognized as a geriatric syndrome [28]. Due to the high heterogeneity of the answers about both amount and content of (mal)nutrition education in the current survey, it is of high importance to develop European standards in the field of nutrition education. There are ongoing efforts to standardize education and training in geriatric medicine [29]. To include education about malnutrition in older adults as part of geriatric education can be one possibility to increase the quality of nutrition education. The extent and content of education of geriatricians differ from country to country, but in most European countries there is a need for improvement [30]. The European Union of Medical Specialists (UEMS) published a consensus paper among geriatricians on a geriatric curriculum with the minimal requirements for medical students. It was concluded that the topic of malnutrition is one important geriatric syndrome in older people and should be included in the geriatricians’ curricula [31].

Sooner or later, nearly every physician will come into contact with malnourished patients [22], regardless of the setting. According to the results of our survey, physicians are not adequately prepared to correctly identify these persons and refer them or treat them in an evidence-based way. Nutritional medicine is a multidisciplinary topic, and dietitians/nutritionists are considered to be experts in the field of clinical nutrition [13]. However, physicians have to be able to identify when an older person is in need of a referral to a dietitian and dietetic treatment. If physicians have not received basic knowledge about malnutrition in older adults, it is highly unlikely that they will consult dietitians for further treatment, working together in a multidisciplinary team to develop nutrition care plans for the patients.

In recent years, researchers have demonstrated that nutritional therapy is effective and can increase body weight, body composition and improve physical functions [32, 33]. It can reduce complication rates and has the potential to reduce the length of hospital stays and readmission rates to hospital [33,34,35]. Some studies could even demonstrate reduced mortality and health-care costs [34,35,36]. However, nutritional therapy in malnourished persons or persons at risk of developing malnutrition can only be successful if these persons are detected at an early stage and if all health-care professionals work together [15].

Some countries, such as the USA, UK and Australia, have invested efforts in recent years to improve nutrition education in medical programs. Some online curricula and Web-based nutrition education resources have been developed to help medical doctors improve their nutritional skills [11, 37]. However, these resources are not available or used in all countries, and physicians must have enough interest in the topic of nutrition and motivation to educate themselves independently.

Conclusion

Based on our results, we strongly recommend including the topic of malnutrition in older adults in the undergraduate curricula of medical students in Europe. Specific topics such as perioperative nutrition or nutrition in ICUs should be included in the courses. A special focus should be placed on multidisciplinary cooperation. Integrative teaching that targets all professional groups could be one option. Furthermore, teachers with expertise in nutrition education should preferably be involved in the educational process. Initiatives need to be carried out to create awareness needed and promote improvements in nutrition education for medical doctors. If nutrition continues to be treated as a secondary subject matter of lesser importance by the educational institutions training health-care professionals, the potential of nutrition therapy will not be expanded in clinical practice, which may result in poorer outcomes for malnourished older persons.

References

World Health Organisation (WHO) (2015) World report on ageing and health. WHO, Geneva

Volkert D (2013) Malnutrition in older adults—urgent need for action: a plea for improving the nutritional situation of older adults. Gerontology 59(4):328–333

Norman K, Pichard C, Lochs H, Pirlich M (2008) Prognostic impact of disease-related malnutrition. Clin Nutr 27(1):5–15

Roller RE, Eglseer D, Eisenberger A, Wirnsberger GH (2016) The Graz Malnutrition Screening (GMS): a new hospital screening tool for malnutrition. Br J Nutr 115(4):650–657

Eglseer D, Halfens RJ, Lohrmann C (2017) Is the presence of a validated malnutrition screening tool associated with better nutritional care in hospitalized patients? Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif) 37:104–111

Vandewoude MFJ, van Wijngaarden JP, De Maesschalck L, Luiking YC, Van Gossum A (2018) The prevalence and health burden of malnutrition in Belgian older people in the community or residing in nursing homes: results of the NutriAction II study. Aging Clin Exp Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-018-0957-2

Thomas MN, Kufeldt J, Kisser U, Hornung HM, Hoffmann J, Andraschko M et al (2016) Effects of malnutrition on complication rates, length of hospital stay, and revenue in elective surgical patients in the G-DRG-system. Nutrition 32(2):249–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2015.08.021

Gomes F, Emery PW, Weekes CE (2016) Risk of malnutrition is an independent predictor of mortality, length of hospital stay, and hospitalization costs in stroke patients. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 25(4):799–806

Marshall S, Bauer J, Isenring E (2014) The consequences of malnutrition following discharge from rehabilitation to the community: a systematic review of current evidence in older adults. J Hum Nutr Diet 27(2):133–141

Volkert D, Beck AM, Cederholm T, Cruz-Jentoft A, Goisser S, Hooper L et al (2018) ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition and hydration in geriatrics. Clin Nutr. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2018.05.024

Kris-Etherton PM, Akabas SR, Bales CW, Bistrian B, Braun L, Edwards MS et al (2014) The need to advance nutrition education in the training of health care professionals and recommended research to evaluate implementation and effectiveness. Am J Clin Nutr 99(5 Suppl):1153s–1166s

Kris-Etherton PM, Akabas SR, Douglas P, Kohlmeier M, Laur C, Lenders CM et al (2015) Nutrition competencies in health professionals’ education and training: a new paradigm. Adv Nutr 6(1):83–87

Hark LA, Deen D (2017) Position of the academy of nutrition and dietetics: interprofessional education in nutrition as an essential component of medical education. J Acad Nutr Diet 117(7):1104–1113

Eglseer D, Halfens RJG, Schussler S, Visser M, Volkert D, Lohrmann C (2018) Is the topic of malnutrition in older adults addressed in the European nursing curricula? A MaNuEL study. Nurs Educ Today 68:13–18

Tappenden KA, Quatrara B, Parkhurst ML, Malone AM, Fanjiang G, Ziegler TR (2013) Critical role of nutrition in improving quality of care: an interdisciplinary call to action to address adult hospital malnutrition. J Acad Nutr Diet 113(9):1219–1237

Adams KM, Kohlmeier M, Powell M, Zeisel SH (2010) Nutrition in medicine: nutrition education for medical students and residents. Nutr Clin Pract 25(5):471–480

DiMaria-Ghalili RA, Mirtallo JM, Tobin BW, Hark L, Van Horn L, Palmer CA (2014) Challenges and opportunities for nutrition education and training in the health care professions: intraprofessional and interprofessional call to action. Am J Clin Nutr 99(5 Suppl):1184s–1193s

Dimaria-Ghalili RA, Edwards M, Friedman G, Jaferi A, Kohlmeier M, Kris-Etherton P et al (2013) Capacity building in nutrition science: revisiting the curricula for medical professionals. Ann NY Acad Sci 1306:21–40

Adams KM, Kohlmeier M, Zeisel SH (2010) Nutrition education in US medical schools: latest update of a national survey. Acad Med 85(9):1537–1542

Adams KM, Lindell KC, Kohlmeier M, Zeisel SH (2006) Status of nutrition education in medical schools. Am J Clin Nutr 83(4):941s–944s

Chung M, van Buul VJ, Wilms E, Nellessen N, Brouns FJ (2014) Nutrition education in European medical schools: results of an international survey. Eur J Clin Nutr 68(7):844–846

Cuerda C, Schneider SM, Van Gossum A (2017) Clinical nutrition education in medical schools: results of an ESPEN survey. Clin Nutr 36(4):915–916

Edwards PJ, Roberts I, Clarke MJ, Diguiseppi C, Wentz R, Kwan I et al (2009) Methods to increase response to postal and electronic questionnaires. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3:Mr000008. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.mr000008.pub4

Fan W, Yan Z (2010) Factors affecting response rates of the web survey: a systematic review. Comp Human Behav 26(2):132–139

Adams KM, Butsch WS, Kohlmeier M (2015) The state of nutrition education at US medical schools. J Biomed Educ 2015:7

Adams KM, Kohlmeier M, Zeisel SH (2010) Nutrition education in US medical schools: latest update of a national survey. Acad Med 85(9):1537–1542

Schreiber KR, Cunningham FO (2016) Nutrition education in the medical school curriculum: a review of the course content at the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland–Bahrain. Ir J Med Sci 185(4):853–856

Pirlich M, Schutz T, Norman K, Gastell S, Lubke HJ, Bischoff SC et al (2006) The German hospital malnutrition study. Clin Nutr 25(4):563–572

Fisher JM, Masud T, Holm EA, Roller-Wirnsberger RE, Stuck AE, Gordon A et al (2017) New horizons in geriatric medicine education and training: the need for pan-European education and training standards. Eur Geriatr Med 8(5):467–473

Michel JP, Huber P, Cruz-Jentoft AJ (2008) Europe-wide survey of teaching in geriatric medicine. J Am Geriatr Soc 56(8):1536–1542

Masud T, Blundell A, Gordon AL, Mulpeter K, Roller R, Singler K et al (2014) European undergraduate curriculum in geriatric medicine developed using an international modified Delphi technique. Age Ageing 43(5):695–702

Baldwin C, Weekes CE (2011) Dietary advice with or without oral nutritional supplements for disease-related malnutrition in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 9:Cd002008

Bally MR, Blaser Yildirim PZ, Bounoure L, Gloy VL, Mueller B, Briel M et al (2016) Nutritional support and outcomes in malnourished medical inpatients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 176(1):43–53

Milne AC, Potter J, Vivanti A, Avenell A (2009) Protein and energy supplementation in elderly people at risk from malnutrition. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2:Cd003288

Elia M, Normand C, Norman K, Laviano A (2016) A systematic review of the cost and cost effectiveness of using standard oral nutritional supplements in the hospital setting. Clin Nutr 35(2):370–380

Deutz NE, Matheson EM, Matarese LE, Luo M, Baggs GE, Nelson JL et al (2016) Readmission and mortality in malnourished, older, hospitalized adults treated with a specialized oral nutritional supplement: a randomized clinical trial. Clin Nutr 35(1):18–26

Kris-Etherton PM, Pratt CA, Saltzman E, Van Horn L (2014) Introduction to nutrition education in training medical and other health care professionals. Am J Clin Nutr 99(5 Suppl):1151s–1152s

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Medical University of Graz. The preparation of this paper was supported by the MAlNUtrition in the ELderly (MaNuEL) knowledge hub. This work was supported by the Joint Programming Initiative ‘Healthy Diet for a Healthy Life’. The funding agencies supporting this work are: Austria: Federal Ministry of Science, Research and Economy (BMWFW—https://doi.org/10.420/0004-wf/v/3c/2016); France: Ecole Supérieure d’Agricultires (ESA); Germany: Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture (BMEL) (2815ERA10E and 2815ERA08E) represented by Federal Office for Agriculture and Food (BLE); Ireland: Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine (DAFM) (15/HDHL/2 MANUEL); and the Health Research Board (HRB); Spain: Instituto de Salud Carlos III, and the SENATOR trial (FP-HEALTH-2012-305930); The Netherlands: The Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw) (50-52905-98-499).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Eglseer, D., Visser, M., Volkert, D. et al. Nutrition education on malnutrition in older adults in European medical schools: need for improvement?. Eur Geriatr Med 10, 313–318 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-018-0154-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-018-0154-z