Abstract

This paper analyzes social mobility as realized by students of a high-quality public flagship university in Brazil, the Federal University of Pernambuco (UFPE), and compares with mobility at US institutions, applying the methodology of Chetty et al. (2017). Intergenerational income mobility is analyzed using the family income of students matriculating to UFPE in 2005–2006 and individual earnings 12–13 years later. Upward mobility is defined as the percentage of students who attain the highest quintile of individual earnings among those who matriculated from the lowest income families. We find that mobility rates are higher at UFPE than at comparator US universities as calculated by Chetty et al. (2017). While these are non-causal estimates, they nonetheless suggest that public universities can play a key role in facilitating upward social mobility in Brazil. Disaggregating by gender, we find higher mobility rates for men than for women in both UFPE and US comparator institutions. Using UFPE admissions data, we are able to explore the role of both ability and major choice on mobility gaps by gender and race. For both women and Afro-Brazilians, the proxy for ability (college entry exam) does not explain the gap in reaching the top earnings quintile compared to white males. However, the choice of major is found to be an important factor in limiting mobility for these demographic groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The practice of not charging tuition or fees at high quality public universities in Latin America has long been criticized as a policy with good intentions that effectively acts as a subsidy from the poor to the rich. The regressive nature of government spending at tertiary schooling compared with spending at lower levels has been highlighted by economists for decades (Psacharopoulos et al. 1986, Rozada and Menendez 2002, and Busso et al. 2017). In Brazil in particular, the tuition-free federal universities were for many years regarded as institutions that primarily served the elite, as the poor were characterized as being excluded by entrance exams that were insurmountable without private schooling and expensive tutoring (Birdsall and James 1993). Telles and Paixao (2013) note that the students at the free-tuition public universities are disproportionately privileged from private secondary schools while students attending the private universities come from the poorly resourced public secondary schools.

Studies of social mobility have traditionally focused on intergenerational income mobility, as this is a very concrete means of assessing whether offspring reach a higher standard of living than their parents. Moving up or down the mobility ladder is not only a concern to parents but also to policymakers. The strong negative correlation between intergenerational income mobility and income inequality is known as the “Great Gatsby Curve,” with Latin American countries well represented in the low intergenerational mobility and high-income inequality quadrant of the graph. Durlauf (1996) and Corak (2013) suggest that higher inequality may impede income mobility. This paper analyzes social mobility as realized by students of a high-quality public flagship university in Brazil, the Federal University of Pernambuco (UFPE). Using administrative data for incoming students, we explore patterns of intergenerational mobility by comparing the family income at the time of matriculation with later young adult earnings. Our approach is similar to the methodology implemented by Chetty et al. (2017) although our analysis is restricted to one large public university in Brazil. We calculate upward mobility rates by race and gender and compare these with public flagship and private universities in the USA as calculated by Chetty et al. (2017). Our analysis explores whether mobility at UFPE, as measured for cohorts matriculating in 2005–2006, aligns with the conventional perception of little mobility at elite public flagship universities or whether the observed mobility is more aligned with that measured in US universities by Chetty et al. (2017). While these are non-causal estimates, they nonetheless suggest that public universities can play a key role in facilitating upward social mobility in Brazil.

Brazil is one of the most unequal countries in the world according to income inequality measures such as the Gini coefficient, and differential earnings by gender and race contribute to this aggregate inequality. Despite completing higher average years of schooling than their male counterparts, women in Brazil earn less than their peers, exhibiting the largest earning gaps in wages in the region after controlling for individual and family characteristics (Ñopo 2012). Morrison et al. (2018) note that race explains 9% of overall income inequality in Brazil. Progress over the last two decades towards achieving universal basic schooling has closed much of the racial gap in completing primary and secondary school; nonetheless, an overall gap in educational attainment by race remains (Marteleto 2012). While race represents a complex social phenomenon in Brazil, it has long been characterized and measured primarily in terms of skin color (Telles 2004, and Mitchell-Walthour 2017). The first national census of 1872 implemented the classification that is still partially in use today—branca (white), parda (brown), preta (black)—while the category amarela (yellow) was added by the national statistical institute (IBGE) in 1940 to enumerate Asian-Brazilians and the category Indigena (Indigenous) added in 1991 (IBGE 2008). The National Statistical Institute recognizes the inadequacy and controversy of what they refer to as a measure of self ethno-racial identification but continue to apply the six category questions in the interest of producing the most consistent information over time (IBGE 2008). With respect to the overall population, the 2010 census of Brazil characterized 50.7% of the population as Afro-Brazilian (7.6% preta, 43.1% parda), 47.7% of the population white, 1.1% Asian-Brazilian, and 0.4% Indigenous. Recent studies have demonstrated the endogenous nature of racial self-identification in Brazil, and how higher educational attainment is no longer is associated with “whitening” but rather a higher probability of self-identifying as Afro-Brazilian out of pride (Marteleto 2012, and Mitchell-Walthour and Darity Jr. 2015).

As the schooling gap by race at the tertiary level of schooling was perceived as extremely persistent, universities in Brazil began implementing compensatory policies to expand access to traditionally excluded students. The Federal Policy which was binding for UFPE only in 2012 guarantees 50% of entrance slots for public school students with half of those spots reserved for low-income students and the overall demographic composition reflecting the ethno-racial composition of the state. The Federal Policy extended earlier policy initiatives that began with the 2002 affirmative action policy at the State University of Rio de Janeiro and spread in non-uniform ways to almost 50 institutions by 2010. It is important to note both the overall context of race in Brazil and the fact that the 2005–2006 cohorts followed in this study entered the university before the affirmative action policy was implemented in 2012. The cohorts who entered under the affirmative action policy have not had sufficient time to graduate and enter the labor market to be able to compare their earnings relative to the income of their parents.

Our results indicate that upward mobility at UFPE compares favorably to public flagships in the USA. While the analysis using data for one flagship university in Brazil, UFPE, is not perfectly comparable to Chetty’s analysis of universities in the USA, it nonetheless allows us to generate the first empirical estimate of mobility along the lines of Chetty et al. (2017) for a public university in Latin America. Moreover, we are able to examine how mobility varies by gender and race, addressing the vacuum in the literature that has focused on males in developed countries because of data availability (Torche 2015). Although we find the UPFE conveys upward mobility for traditionally socially excluded individuals, we emphasize that under-representation of low-income and Afro-Brazilian students, particularly in competitive high-remunerated majors. Hence, while our analysis suggest that public universities can play a key role in facilitating upward social mobility in Brazil, the overall potential impact is not realized if access remains highly unequal.

The remainder of the article is organized as follows. In the next section, we provide background information on students enrolled at the Federal University of Pernambuco, along with a description of the university’s admissions policy. The “Data” section describes the data and details the sample used throughout the analysis. The “Methodology” section presents the methodology, and the “Results” section describes the empirical findings. The “Conclusions and Policy Implications” section concludes the paper.

Background

Our primary unit of analysis is students applying to the Federal University of Pernambuco in Brazil (Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, UFPE) in the years of 2005 and 2006. UFPE is the major flagship university in the northeast of Brazil and one of the top ten institutions in the country,Footnote 1 according to the Ministry of Education. In addition to its high quality and reputation, it is a public university and does not charge tuition. These features make it a very attractive choice for high school applicants from the state of Pernambuco, regardless of their future career choices or socioeconomic background. As of 2018, enrollment at all university campus includes 30,000 undergraduate and 13,000 graduate students, with an average of 5,000 undergraduate students admitted per year over the period of analysis 2005–2006.

Currently, the university offers 99 undergraduate programs.Footnote 2 Most of the undergraduate programs consist of four years of coursework, and some are five-year programs (34%).Footnote 3 Unlike in the USA, students must decide their major before applying and matriculating to university. The major preference must be determined before taking the entrance exam to UFPE since the second part of the exam is content specific. As such students compete for a spot at the university only with those who choose the same major.

Students are admitted to the university based on their entrance exam score called the vestibular, which is held once per year and tests candidates through different subjects in two rounds. The first round covers nine subjects (Mathematics, Portuguese, a foreign language, Literature, History, Geography, Physics, Chemistry, and Biology) and is the same regardless the major she is applying to. The final round is a specific-area exam which evaluates the applicants in Portuguese and three other subjects particularly required for the competed program. Only recently, in 2015, UFPE started adopting the new national centralized entrance process (Unified Selection System, SISU) applied to all public higher education institutions, ending institution-specific exams.

For the cohort of 2005–2006, the acceptance rate to the university was 10%. The majority of candidates are students who have recently graduated from secondary school, but those taking the exam includes individuals who were not admitted in the past or students intending to switch majors. Any individual with a high school diploma or equivalentFootnote 4 can apply to a specific major in the university, and their chances to be admitted are exclusively determined by their performance on the vestibular. In other words, for the cohort we follow in the study, UFPE was not allowed to use other criteria to admit candidates (Matta et al. 2016).

As a point of reference for the national population, 28.8% of the college age population (18–25 year olds) who completed secondary school were attending a post-secondary educational institution in 2006.Footnote 5 As a highly selective institution the students admitted to UFPE are not representative of students at all Brazilian universities. In that sense, and to provide some context to how UFPE compares to the rest of the country, in Table 1, we compare Exame Nacional do Ensino Médio (ENEM) scores for entrants of the University with general scores from students entering college in Pernambuco and Brazil in the year 2006 (MEC 2006). The ENEM is a standardized, non-mandatory Brazilian national exam for high school students in Brazil and is mostly used as one of the admission criteria for being accepted into tertiary education. UFPE matriculants perform better than the national and state averages for entrants in Universities across the country.

The same pattern is observed when the focus is on family educational background. For UPFE students, we use mother’s tertiary education level as reported by the 2004 matriculants. At the national and regional levels, we draw from a 2005 Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais (INEP) study of ENEM participants—a proxy for individuals applying to University that year (INEP 2006). Analogous to the pattern seen with ENEM scores, matriculating UFPE students come from a more advantageous educational background than their regional or national peers.

While UFPE is an elite university compared to all universities in Brazil, it well-represents the 36 federal public universities that are found to outperform private universities (Hoffman et al. 2014). As shown in Table 13 in the Appendix, the index of the quality of the undergraduate and graduate courses offered by UFPE is close to the mean of all federal public universities. Choice of major by gender at UFPE also displays a similar pattern as found in other federal universities. Women are extremely under-represented in math and engineering majors, representing only 20% of students, and over-represented in teaching majors (88%).

Data

Data Sources and Sample

Our study uses three different datasets. The first comes from the admission committee (Comissão de Concursos e Vestibulares, COVEST), which provides detailed information about every UFPE applicant over the period of 2005–2006. It contains a wide range of socioeconomic characteristics including the family income reported at the time the student took the entry exam, as well as the first round of the college entry exam in which the content is common regardless of area of study. The income of the family, which is used to obtain our key explanatory variable, is not reported continuously but in categories. As such, we are not able to use the exact categories to replicate the bottom income quintile. The bracket of family income is assigned a percentile according to the national household income distribution as measured in the 2005 and 2006 Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios (National Household Survey - PNAD) (IBGE 2017). The lowest income category of a monthly family income of 300 reais or below corresponds to the cutoff for the income of the families with the 17% lowest incomes in 2005 and 12% lowest incomes in 2006.Footnote 6 Student in families earning above 2000 reais monthly are in the top quintile of family income, or to be precise in the top 17% of families in 2005 and in the top 20% in 2006. For simplicity, we will refer to these as the lowest (Q1) and highest income (Q5) quintiles.

While we do not have an external means of validating the self-reported parental income from the COVEST, we note that there is a high correspondence between the lowest income category and low parental education. Of the entrants in 2005–2006 reporting the lowest family income category, 38.3% reported the schooling attainment of the mother was less than primary complete. Of the matriculants reporting the highest family income category, 7% of the mothers of this group attained less than complete primary school. The COVEST data also includes information on student’s age, gender, race, parents’ occupations, and type of high school (public or private). The information on parents’ occupations is reported by the student and indicates if her mother and father work as a public employee, private employee, entrepreneur, farmer, or other occupation.Footnote 7 The student’s race is self-reported according to the standard IBGE classifications. The fact that race is reported at entry addresses concerns that the student might change his or her classification based on her success in school or in the labor market. The reporting of race also occurred 6 years before the affirmative action programs were implemented at UFPE.

The second data used in our analysis is UFPE’s Academic Information System (Sistema de Informações Acadêmicas, SIGA), which precisely informs the academic situation of UFPE enrollees. Matching SIGA with COVEST allows us to identify candidates who matriculated at UFPE and their assigned major program. In addition, SIGA plays an important role on recovering any missing values in the gender variable obtained from COVEST, since it requires precise registration by students. Our initial sample consists in 9707 students matched from these two datasets.

Finally, individual earnings for the sample of students who entered UFPE in 2005–2006 in Brazil are measured 12–13 years later using an administrative database, the Relação Anual de Informações Sociais (RAIS), which is linked to the tax system and covers approximately 49.6 million records for individuals in 2017.Footnote 8 The RAIS is a longitudinal dataset at the employee–employer level, with national coverage of the Brazilian formal labor market. To match the three databases at the student level, we used the individual unique social security number, which is required at the time of application and at the university’s enrollment process, and search across all 49.6 million RAIS records of formal employment covering all states in Brazil. The young adult earnings for the sample of US college students is also taken from tax records as reported in 2014 for wage earnings and net self-employment income. An individual’s percentile in the earnings is based on the national distribution of individual earnings for others in the same birth cohort.Footnote 9 To obtain the top quintile of our dependent variable, we used the national income threshold calculated from RAIS. Moreover, the individuals’ earnings were deflated to December 2006 using the Extended Consumer Price Index (IPCA). The final sample includes 5985 students.

The US analysis relies heavily on tax records in which students attending accredited US colleges are matched by social security numbers across tax forms in which the students have been listed as dependents, typically by parent(s). The US sample is comprised of 6.7 million students ages 19–22 who attended 2199 accredited universities in 1999–2004. Parental income for this sample reflects the average of when the college student was age 15–19 in 1996–2000 to smooth transitory fluctuations. The family income is ranked relative to all other families in the national distribution who have children in the same birth cohort.

Table 2 summarizes the differences in the data sources for the UFPE analysis and the analysis of US universities by Chetty et al. (2017). Some key differences in the data should be highlighted. The narrower lowest income bracket in Brazil, covering students from the lowest 17% in 2005 and lowest 12% in 2006 rather than the lowest 20% of family incomes, serves to underestimate the measure of upward mobility in UFPE relative to the measures at universities in the USA. The coverage of earners into taxable earnings, while high in both cases, is likely to be different for the USA and Brazil and may influence the results as well.

While the analysis for UFPE is not perfectly comparable to Chetty’s analysis of universities in the USA, it nonetheless permits us to assess whether the observed social mobility better aligns with traditional perception of public flagship universities in Latin America (little to no mobility) or perceptions of universities in the USA (considerable mobility). It is possible to compare mobility by gender using both the UFPE and Chetty datasets but self-reported data on race is only available in the UFPE data, so we will not be able to compare social mobility by race with US universities.

Descriptive Statistics

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics for all variables used in the analysis. The first three columns depict the initial sample of students derived from the match between COVEST-SIGA datasets. The final sample, presented in the latter three columns, represents the subset of individuals found in the formal labor market in 2017, conditioned on having between 18 and 29 years of age and being White or Afro-Brazilian. We match 62.2% of students from the enrollment data for the 2005–2006 cohorts with earnings from formal jobs in 2017, irrespective of gender. This is slightly higher than the 52.2% of individuals measured as contributing to labor taxes through formal sector employment for the same age group in the 2015 National Household Survey.

The unconditional means reveal that the patterns are very similar across the two samples. The share of students from the poorest households is 7% in both samples, but there are slight differences across the higher income brackets, with students from the top quintile being slightly underrepresented in the final sample. Self-identification of ethnic-racial category was reported in the COVEST using the same questions as in the census. Given that the sample is not sufficient for statistical analysis of students who identify as Indigenous and Asian-Brazilian, we focus on students identifying as Afro-Brazilian (pardo and preto) and White who comprise 44% and 56% of the sample, respectively.Footnote 10 The UFPE enrollees are equally divided across gender and have an average of 21 years of age. Regarding the family income, Table 3 also highlights that more than 30% of the students come from more wealthy backgrounds, while 52% attain the 71 percentile of the national income distribution, which translates into around 4.2–5 minimum salaries at 2005–2006 values. About 12–13 years after matriculating in the university, the earnings are very favorable: 66% of the matriculants reach the highest quintile of the national income distribution. In the next section we analyze intergenerational mobility using transition rates and control for other factors.

Methodology

To compare with Chetty et al. (2017), we define upward mobility as the percentage of students who matriculate to the university from the lowest quintile according to the their families income with respect to the national distribution of family income, and subsequently attain as young adults the highest quintile of earnings, again measured relative to their peers in the national distribution of earnings. We also measure the persistence of intergenerational income associated with universities by measuring the percentage of students matriculating in the highest family income quintile who maintain the highest income quintile bracket of earnings as young adults. It is important to clarify that the methodology applied does not identify the causal effects on students of attending a university, but rather is a descriptive analysis of the intergenerational mobility associated with the universities.

Following Chetty et al. (2017), we calculate an index that estimates the effectiveness of the university at social mobility which depends on the mobility rate as well as the university’s coverage of the poor students. Whereas the transition mobility measures the effectiveness on upward mobility from the perspective of a low-income individual, the college mobility index assesses the overall mobility of low-income students realized by the university. If the policymaker’s objective is to maximize the chance of a low-income matriculant reaching the highest earnings bracket the transition mobility is most relevant. But if the policymaker is more interested in the number of poor students who experience upward mobility, the university index is more relevant. A similar index is compiled to measure the persistence associated with specific colleges. To calculate the index of college persistence, the transition persistence is multiplied by the coverage of students from the highest income bracket. Expanding from Chetty et al. (2017), we further present disaggregated mobility results by gender and race. Finally, we examine the probability of reaching the top earnings quintile using linear probability models to examine whether gender and race differences are significant after controlling for family and individual characteristics.

Results

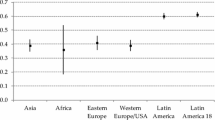

While the analysis for Brazil is neither comprehensive nor fully comparable to Chetty’s analysis of universities in the USA, it nonetheless permits us to assess whether the social mobility observed at UFPE is aligned with common perceptions. As can be seen in Tables 4 and 5 for UFPE as well as in US universities, the measure of persistence, or the probability of attaining the highest quintile of earnings as young adults given that one matriculated in the highest income quintile, is higher than mobility, or the probability of transitioning from the lowest to highest income bracket.Footnote 11 The higher success rates in reaching the highest earning brackets for the most advantaged students do not contrast with the conventional wisdom. UFPE’s overall index of persistence is very similar to the average of the public flagship universities in the USA (25.5 vs. 22.4). But this similar outcome reflects two different dynamics across the public flagships. The share of students coming from the highest income families is much higher in the US public flagship institutions while the transition probability of maintaining one’s place in the highest ranks is higher at UFPE. At UFPE 76.1% of students who enter in 2005–2006 from the richest families are measured in the RAIS in 2017 as earning in the top quintile of the earnings distribution for their age group. This high level of persistence reflects the traditional narrative about public universities preserving the distribution of wealth in Brazil.

However, contrary to the conventional wisdom, as can be seen in Table 5, UFPE is associated with considerable intergenerational upward mobility. The observed mobility at Brazil’s flagship public university UFPE (45.9%) is higher than the mobility rates at the US public flagship universities (33.9% on average).Footnote 12 The university’s overall effectiveness observed in promoting social mobility depends on the coverage of low-income students. The measure of coverage of low-income students at UFPE, despite its focus on than the lowest quintile, is higher than that at US Ivy-plus institutions and US public flagships. The overall social mobility index for UFPE (3.0%) is above Stanford, Yale, and Harvard and at the top of the range of the US public flagships.Footnote 13 In this sense, the public flagship of UFPE can be described as on the path to being an “engine of social mobility,” as Chetty et al. (2017) describes the US public flagships with the highest indices of mobility (Tables 6 and 7).

It is important to note that while we have documented considerable mobility from lowest to highest income brackets at UFPE, these transitions are not realized by all students in the sample and as noted in other research in the region, some students may encounter downward mobility and/or negative private returns on their investments in tertiary education. The tremendous expansion in tertiary schooling has placed downward pressure on the returns to completing tertiary as compared with secondary. Not only have returns to completing tertiary versus secondary declined in recent years (Busso et al. 2017), but studies find that the private return to graduating from college is negative for approximately 30% of students in Colombia and 20% of students in Chile (Gonzalez-Velosa et al. 2015).Footnote 14 Moreover, studies have found declines in the overall quality of tertiary schooling provided as compared with earlier years (Busso et al. 2017).Footnote 15

Heterogeneity

When disaggregating results by gender we note higher rates of persistence and mobility for males than for females, both at UFPE and in the US universities but a differential pattern of matriculation by income background. Women are more likely than men to matriculate from the lowest income bracket and less likely from the highest income families, for both UFPE and the US public flagships.

With regard to race, we disaggregate the UFPE data (Table 8) but are unable to compare to results for US universities as they are not available. As in the previous analysis, persistence is observed to be higher than mobility for both White and Afro-Brazilian students. The probability of transitioning from the poorest income bracket to the highest (mobility) is marginally higher for whites than Afro-Brazilians, and the probability of staying in the top quintile is the same for both groups. While intergenerational mobility by race is not analyzed through the role of the universities in the USA, another paper by the Chetty research group finds that with respect to overall intergenerational mobility, Black males in the USA are more likely to exit the highest income bracket than their white counterparts (Chetty et al. 2018). The small to no difference in the transition rates by race at UFPE are complemented with a pattern of matriculation that promotes social inclusion. As shown in the last column of Table 8, once we consider the differential pattern of matriculation by income background, with a higher coverage of Afro-Brazilians in the lowest income brackets, UFPE as an institution is achieving a higher index of intergenerational income mobility for Afro-Brazilian students than for white students. In other words, UFPE is moving more Afro-Brazilian students than White students from the lowest income bracket to the top bracket not because of a higher individual transition rate but because of a higher rate of coverage.

Linear Probability Regressions

Table 9 displays the results of linear probability models that predict the probability that the individual earns in the top salary quintile among 27–39 year olds in all Brazil in 2017. We control for a set of family and individual characteristics including family income bracket, matriculation from private secondary school, first round entry exam score, choice of major, grade-point average in first semester, race, and gender.Footnote 16 The negative monotonic relationship between family income bracket and individual earnings is maintained when controls for female and Afro-Brazilian are introduced in the specification presented in column 3. However, the addition of the first round entry exam score and fixed effects by major attenuates the effect of the family income variables, with all brackets remaining significantly less likely to reach the top earnings quintile although with half or a third of their original magnitude.

One of the most consistent findings is the significantly negative female effect, indicating that female students are 4.9–12.4 percentage points less likely to reach the highest earnings quintile than their male peers. With simple controls for family income, the female penalty is approximately 12.4 percentage points as shown in regression 3. The introduction of a proxy for ability, the first round college entry score in regression 4, does little to attenuate the female penalty, suggesting that ability does not explain this gender difference. However more than half of the difference appears to be related to the choice of major as the female penalty in the specification of column 6 declines by over half with the addition of a set of dummies for major at first semester.

The results in Table 9 also reflect the patterns observed in Table 8 of lower mobility rates for Afro-Brazilian students. A significant and considerable gap of 7.0 percentage points for Afro-Brazilians is estimated when only the gender variable is included as shown in column 7. The gap by race reflects historical patterns of exclusion in Brazil as the distribution of family income among the Afro-Brazilian students is more concentrated in the lower categories than among White students. The estimated parameter for Afro-Brazilians falls by almost half when family income is included in regression 3. While the disadvantage by race is less than one-half the size of gender, it also does not change substantially when the proxy for ability (vestibular score) is added in column 4. However, once controls for majors are added in column 6 there is no longer a significant penalty to race. This suggests that for the 2005–2006 population of students matriculating to UFPE, these basic explanatory variables explain the differences observed in reaching to the highest earnings quintile.

The inclusion of fixed effects by major indicates that, in fact, the career choice made previously to university entrance plays a role in explaining differences in future earnings across gender and race. As shown in Table 12, the summary statistics suggest that females and Afro-Brazilians tend to choose majors with lower returns in the labor market. For instance, the concentration of Afro-Brazilians and females in fields like humanities is very pronounced compared to their lower representation in STEM fields (Bustelo et al. 2019). The asymmetric distribution of these two characteristics across fields raises questions about their career choices prior to entering the tertiary education system. Possible explanations could relate to the lack of role models in some fields (Hoffmann and Oreopoulos 2009) or poor incentives to invest in stereotyped subjects— like Math and Physics—in early grades (Pope and Sydnor 2010). Specifically for Afro-Brazilian students, the fact that matriculation is more often than not preceded by an attendance to low quality primary and secondary public schools (Cavalcanti et al. 2010) can also work as an additional barrier in accessing more competitive/high return majors.

We also explore these same relationships through the set of basic regressions that are run separately on the demographic groups as shown in Table 10. The double-disadvantage for Afro-Brazilian women is demonstrated in the regressions in columns 1 and 4. The penalty to being female is higher for Afro-Brazilian women than for white women and the penalty for being Afro-Brazilian is negative and significant for females but not for males. The different functional forms are evident with males demonstrating a much steeper relationship between family income and the probability of reaching the top earning quintile than women, particularly among White students.

Concerns about Selection

Our results suggest that entry into UFPE conveys considerable upward social mobility for low-income and traditionally marginalized populations in Brazil. As we are not able to match a large proportion of the matriculating cohort from 2005 to 2006 with formal labor income in 2017, the methodology raises concerns about selection. Of primary concern is whether the students who are not observed in the 2017 RAIS income data have very different transition rates than the students with observed salary data. Table 11 examines the probability of being observed in the RAIS labor income data among the sample of students from the lowest income bracket. There are no individual or family characteristics that are significantly correlated with having a formal labor market income in 2017. While our results remain descriptive rather than causal, the analysis in Table 11 suggests that we are not overestimating upward mobility by omitting students with weaker observable characteristics from the analysis.

Conclusions and Policy Implications

The persistence of economic advantage as passed from one generation to another is observed in both the US universities as well as at UFPE, where college students matriculating from high income backgrounds are one third to two thirds more likely to reach the upper rungs of young adult earnings than peers from low-income backgrounds. Conventional perception has held that universities in Latin America, particularly flagship public universities, did not offer a ladder for low-income students to attain the highest rungs of earnings as young adults. Without population registries and other types of longitudinal data, the opportunity to explore intergenerational mobility has been very limited in developing countries, including in Latin America. This analysis demonstrates that for cohorts entering between 2005 and 2006, the Federal University of Pernambuco (UFPE) provided more mobility than the average for US flagship public universities as well as a higher index of mobility than numerous elite private universities in the USA. It is worth noting that at this period in time approximately 7% of students matriculated from families from the lowest income quintile in Brazil compared to 36% from the top quintile, in effect limiting the university’s overall contribution to reducing income inequality.

At UFPE as elsewhere in the region of Latin America and the Caribbean over the past two decades, women have moved ahead of men in terms of access to tertiary schooling, but when it comes to transforming the college experience to labor market remuneration, men have maintained their advantage (Duryea and Robles 2017). As is the case in the USA, we find that female entrants at UFPE experience lower intergenerational income mobility than male counterparts. Our analysis suggests that this is explained not through differential ability by gender but in large part explained by differential major choice by gender. Brazil is beginning to explore programs to promote the interest and self-confidence of girls into non-traditional majors, such as through after-school girls coding clubs and other initiatives. As the selection of major is made at a much earlier stage in Brazil than in the USA, it is even more important that these initiatives target girls as they are forming expectations about university courses and future careers.

Important differences in mobility are also found across race. The lower probability for Afro-Brazilian matriculants at UFPE to earn in the top income quintile is related to historical patterns of discrimination in Brazil. Success at reaching the top quintile is correlated with one’s family income at matriculation with the family income of Afro-Brazilian students more concentrated in the lower brackets. Racial differences in reaching the top earnings bracket are largely explained by income and choice of major, but not ability.

The cohorts analyzed entered UFPE in 2005–2006 and thus pre-date the Federal Policy of affirmative action that was implemented at UFPE in 2012. While our analysis finds considerable upward mobility for traditionally marginalized students, only 7% of the student population overall matriculated from the lowest income brackets and the percentage of students identifying as Afro-Brazilian (45%) is far below the share identifying as Afro-Brazilians in the state of Pernambuco (67%) using a similar age group.Footnote 17 Moreover, as seen in Table 12, Afro-Brazilians are concentrated in poorly remunerated majors, with particularly poor representation in competitive majors such as medicine and engineering. The affirmative action policies implemented in 2012 are designed to address the under-representation of low-income and Afro-Brazilian students, and are implemented within major, with the aim of maximizing the number of students the federal universities place on the path of upward mobility.

There are some limitations of the study that have implications for future research. The threshold for the lowest relative income category in Brazil is lower than the bottom quintile used in the USA, leading us to underestimate mobility in Brazil. The findings for the UFPE sample are also limited to individuals who are included in the tax data of firms. While women and men appear in the tax records at similar rates, and observable characteristics are similar, self-employed and informal sector workers may differ in unobservable factors related to mobility. Although our results are non-causal, they nonetheless suggest that public universities can play a key role in facilitating upward social mobility in Brazil and that policies that expand access can more fully realize universities as drivers of mobility. Future work will be able to explore whether cohorts who entered under subsequent affirmative action policies experienced accelerated social mobility.

Notes

Yearly, MEC performs a stringent evaluation of Brazilian Higher Education Institutions (private and public) based in a vast range of inputs related to infrastructure, quality of majors and teachers, management effectiveness, and student’s academic performance. UFPE always have been figured at the twenty best Brazilian public universities since the first MEC evaluation and is currently in the 2nd percentile on the distribution of institutions quality.

This number does not include special programs, such as those focused on distance learning and high school teachers without college degree.

Due to its complexity, students must attend six years of college education to graduate in Medicine.

Students with high age/grade distortion may obtain secondary schooling with a method called supletivo, which is an alternative method to compensate the disadvantages related to opportunities in higher education assess. It basically summarizes all high school program, which usually takes 3 years, in one intensive year course.

Calculation based on 2006 National Household Survey (Pesquisa Nacional Por Amostra de Domicilios).

The assignment of each student in the national distribution of earnings was based on the microdata of the 2005 and 2006 PNAD. The assignments for 2005 were also validated with the reports by IBGE on the distribution of family income for 2005 as the minimum monthly salary was 300 reais and therefore the income categories reported in the IBGE tables corresponded with the categories in the COVEST.

COVEST data includes a domestic worker occupation exclusively for student’s mother.

RAIS or Yearly Social Information Report is a large restricted-access federal dataset collected by the Brazilian Ministry of Labor. Every year, tax registered firms are legally required to report every worker formally employed at some point during the previous calendar year.

We calculate the average monthly wage and deflate it to December 2006 for comparability purposes.

The COVEST sample was comprised of 1% of students who self-identified as Indigenous and 4% as Asian-Brazilian.

We should keep in mind that the comparisons are similar but not equivalent across countries.

Chetty et al. define public flagships using the College Board Annual Survey of Colleges (2016). There are 32 US flagships included in the average.

Again, we are likely underestimating mobility in the case of Brazil.

Private returns take into consideration the costs, including opportunity costs, of additional education not only the difference in earnings between different levels of schooling.

We have full transition matrix (presented in the appendix) for UFPE, but we do not have the full transition matrix for the USA.

The regressions also include a dummy for living in the city of Recife at the time of application and dummies for parents’ occupations (self-employed, entrepreneur, private employee, farmer or other). The results are qualitatively the same with the exclusion of the geographic and occupational controls.

The 2015 PNAD uses the same self-identification classification for race as the COVEST. The percentage of Pernambuco self-identifying as AFro-Brazilian was calculated using an age group of 17–25. The state of Pernambuco has a higher share of Afro-Brazilians (pardo and preto) than the national average.

References

Birdsall N, James E. Efficiency and equity in social spending: how and why governments misbehave. In: Lipton M, van der Gaag J, editors. Including the poor. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1993.

Busso M, Cristia J, Hincapié D, Messina J, Ripani L. Learning better: public policy for skills development. Washington, D.C.: Inter-American Development Bank; 2017.

Bustelo M, Duryea S, Piras C, Sampaio B, Trevisan G, Viollaz M. The role of college major on the gender pay gap in Brazil. Washington, D.C.: Inter-American Development Bank; 2019.

Cavalcanti T, Guimaraes J, Sampaio B. Barriers to skill acquisition in Brazil: public and private school students performance in a public university entrance exam. Q Rev Econ Finance. 2010;50(4):395–407.

Chetty R, Friedman J, Saez E, Turner N and Yagan D. Mobility report cards: the role of colleges in intergenerational mobility. The equality of opportunity project. 2017. Available at: http://www.equality-of-opportunity.org/papers/coll_mrc_paper.pdf. Accessed Jan 2019

Chetty R, Hendren N, Jones MR, Porter SR. Race and economic opportunity in the United States: an intergenerational perspective. NBER Working Paper 24441; 2018.

Corak M. Income inequality, equality of opportunity, and intergenerational mobility. J Econ Perspect. 2013;27(3):79–102.

Durlauf SN. A theory of persistent income inequality. J Econ Growth. 1996;1(1):75–93.

Duryea S, Robles M. Family legacy: Breaking the mold or repeating patterns? Social Pulse in Latin America and the Caribbean 2017, Inter-American Development Bank. 2017.

Gonzalez-Velosa C, Rucci G, Sarzosa M, Urzúa S. Returns to higher education in Chile and Colombia. IDB working paper series no. IDB-WP-587; 2015.

Hoffman C, Zanini R, Corrêa A, Siluk J, Schuch Júnior V, Ávila L. Performance of Brazilian universities in view of the general course index (IGC). Educ Pesqui. 2014;40(3):651–65.

Hoffmann F, Oreopoulos P. A professor like me the influence of instructor gender on college achievement. J Hum Resour. 2009;44(2):479–94.

IBGE. Características Étnico-Raciais da População. Um Estudo Das Categorias de Classificação de Cor Ou Raça. 2008.

IBGE. Microdados reponderados da PNAD 2001–2012. Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios anual, Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística; 2017. Available at: http://www.ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/populacao/trabalhoerendimento/pnad2015/microdados.shtm. Accessed Jul 2018

INEP. Resultados do ENEM 2005 Análise do perfil socioeconômico e do desempenho dos participantes. Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira, Ministério da Educação, Brasília. 2006. Available at: http://portal.inep.gov.br/informacao-da-publicacao/-/asset_publisher/6JYIsGMAMkW1/document/id/488832. Accessed May 2019

Marteleto LJ. Educational inequality by race in Brazil, 1982-2007: structural changes and shifts in racial classification. Demography. 2012;49(1):337–58.

Matta R, Ribas R, Sampaio B, Sampaio G. The effect of age at school entry on college admission and earnings: A regression-discontinuity approach. IZA Journal of Labor Economics. 2016;5(9):1–25

MEC. Desempenho médio na parte objetiva da prova do Enem 2006. Assessoria de Comunicação Social, Ministério da Educação, Brasília. 2006. Available at: http://portal.mec.gov.br/arquivos/pdf/tabelas_enem.pdf. Accessed Jul 2018

Mitchell-Walthour G. Economic pessimism and racial discrimination in Brazil. J Black Stud. 2017;48(7):675–97.

Mitchell-Walthour G, Darity W Jr. Choosing blackness in Brazil’s racialized democracy: the endogeneity of race in Salvador and São Paulo. Lat Am Caribb Ethn Stud. 2015;9(3):318–48.

Morrison J, Lustig N, Ratzlaff A. Ethno-racial inequality and fiscal policy in Latin America. 2018.

Ñopo H. New century old disparities - gender and ethnic earnings gaps in latin America and the Caribbean, New York Avenue, Inter-American Development Bank. 2012.

Pope D, Sydnor J. Geographic variation in the gender differences in test scores. J Econ Perspect. 2010;24(2):95–108.

Psacharopoulos G, Jee-Peng T, Jimenez E. Financing education in developing countries: an exploration of policy options. Washington, D.C.: World Bank. Education and Training Dept. Research division; 1986.

RAIS. Relação Anual de Informações Sociais, Database from the Ministério do Trabalho, Brasília; 2017.

Rozada M, Menendez A. Public university in Argentina: subsidizing the rich? Econ Educ Rev. 2002;21(4):341–51.

Telles E. Race in another America: the significance of skin color in Brazil. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2004.

Telles E, Paixao M. Affirmative action in Brazil: LASAFORUM; 2013.

Torche F. Intergenerational mobility and gender in Mexico. Social Forces. 2015;94(2):563–87.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted with restricted access to COVEST (UFPE) data that protected confidentiality. The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not reflect the views of UFPE or the Inter-American Development Bank or the Board of Directors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Duryea, S., de Freitas, L.B., Ozemela, L.MG. et al. Universities and Intergenerational Social Mobility in Brazil: Examining Patterns by Race and Gender. J Econ Race Policy 2, 240–256 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41996-019-00033-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41996-019-00033-1