Abstract

A decorated ulna of a gannet (Morus bassanus) was found in 1966 during the exploration of the archaeological site of Torre cave (Gipuzkoa, northern Iberian Peninsula). The present study offers a new appraisal of this truly outstanding art object through a technological and stylistic analysis enriched by more recent finds. What makes this object extraordinary is the fact that it is one of the most complete specimens in the Iberian Peninsula. Moreover, the Torre tube is one of the few remains with peri-cylindrical decoration displaying a complex combination of motifs. It is profusely decorated with figurative representations (deer, horse, ibex, chamois, aurochs and an anthropomorph) and signs (single lines, parallel lines, zigzags, etc.) in two rows in opposite directions. The tube resembles objects from other Magdalenian sites in Cantabrian Spain and the Pyrenees, which corroborate the exchange of technical and iconographic behaviour.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It is over 50 years since the discovery and exemplary publication (Barandiarán, 1971) of one of the most important portable art objects in the Cantabrian region made of hard animal material. In the intervening years, both photographic and microscopic technologies have advanced enormously and details can now be viewed with a resolution that was unimaginable at the time of the discovery. Additionally, progress in field and laboratory work enables better contextualisation of this object within a larger repertory. Although little information is available about human occupations at the site of Torre cave, the find of a bird ulna (Morus bassanus) that is practically complete and profusely decorated deserves a new in-depth study, including from the technological viewpoint.

In the analytic field of portable art, tubes are defined as elongated hollow bone objects, generally obtained from the long bones of birds, with a sub-circular cross-section or cylindrical in shape (Averbouh, 1993, 2003a, 2003b). The ends of the tubes may appear with different morphologies depending on the alterations made to the bone, but complete tubes often appear with their ends sawn off and therefore lack the epiphyses. On other occasions, however, the proximal end is preserved whereas the distal end is broken, as in the case of the Torre tube. Some of these objects possess one or more perforations in their shaft and may or may not be decorated with figurative motifs and/or signs. They were first described in the late nineteenth century (first mentioned by Piette, 1876) and have been ascribed typologically to different categories and attributed to an array of possible functions in the course of historiography: panpipes (Piette, 1907), containers for needles (Déchelette, 1924), flutes (e.g. Absolon, 1937; d’Errico et al., 2003; Conard et al., 2009; Shaham, 2012), whistle (Allain, 1950), beads in the process of being made (Péquart & Péquart, 1960), a container for ochre (Leroi-Gourhan, 1965), ritual objects (Barandiarán, 1971), aerographs (Montes Barquín et al., 2004; Rozoy, 1978), ornamental objects (Taborin, 1989), aerophones (e.g. Clodoré-Tissot et al., 2009; Ibáñez et al., 2015; Lbova et al., 2013; Münzel et al., 2016; Davin et al., in revision), etc.

In the case of bird bone tubes with several perforations in regular spaces, their use as wind instruments has been accepted unanimously by the scientific community and they are often described as the first musical instruments in the archaeological record. There has been an intense debate about the existence of musical instruments at archaeological sites associated with the Middle Palaeolithic and a possible musical tradition of the Neanderthals. An artefact that has raised many discussions is a cave bear (Ursus spelaeus) femur shaft from the site of Divje Babe I in Slovenia, with six perforations at regular distances, of which three are intact. This object has divided the opinion of researchers between those who support the explanation that it is a musical instrument made by a Neanderthal (Turk & Košir, 2017; Turk et al., 1995, 2018, 2020) and those who deny it with taphonomic arguments, as they attribute the perforations to punctures made by the canine teeth of carnivores (Chase & Nowell, 1998; d’Errico et al., 1998a, 1998b, 2003; Albrecht et al., 2001; Diedrich, 2015).

Apart from this controversial Mousterian specimen from Divje Babe I, the first flutes accepted as such come from Early Aurignacian sites in the southwest of Germany, Hohle Fels and Vogelherd and are dated in c. 35,000 cal. BP (Conard et al., 2009). Similar objects continue to appear in the rest of the Upper Palaeolithic, such as the group of flutes from Isturitz (Pyrénées-Atlantiques, France) dated between the Aurignacian and Magdalenian, although most are attributed to the Gravettian technocomplex (Buisson, 1990; d’Errico et al., 2003). The oldest pierced bird tubes, defined as aerophones, have recently been found in the Near East at the Natufian site of Eynan-Ain-Mallaha (Upper Jordan Valley, Israel) dated c. 12,000 BP (Davin et al., in revision).

In contrast, no clear consensus has been reached about the function of bone tubes without perforations, as the one studied here. Some of the proposed functions were compiled by Averbouh (1993: 110), who discriminated three functional groups: musical instruments, recipients and others (amulets, personal ornaments).

Tubes have been found at sites across Europe, with the greatest concentration in the areas of Périgord and the Pyrenees, at such sites as La Vache (Clottes & Delporte, 2003), Gourdan (Chollot, 1964), Isturitz (Buisson, 1990), Le Placard (Chauvet, 1910) and Mas d’Azil (Péquart & Péquart, 1960). Fewer examples of bone tubes are known in the Iberian Peninsula, but they include finds at Santimamiñe (González Sainz, 2011), La Güelga (Menéndez & García, 1998), Altamira (Breuil & Obermaier, 1935), Rascaño (González Echegaray & Barandiarán, 1981), El Valle (Obermaier, 1925; Cheyner & González Echegaray, 1964), La Paloma (Corchón, 1986), Las Caldas (Corchón, 2018) and Cova dels Blaus (Casabó et al., 1991). The Torre tube (Barandiarán, 1971) is one of the most complete specimens in the peninsula and also one of the few with peri-cylindrical decoration (like, for instance, at La Mairie and La Vache, France) and a combination of motifs on the whole surface of the bone. Within the category of decorated tubes, it is assigned to the Upper Magdalenian and, owing to its decoration, it may have been used for a different purpose than the other tubes mentioned here. Its exhaustive description will consequently provide valuable information about the cognitive capacity of Magdalenian hunter-gatherers and data about the technical and iconographic exchange.

The Site: Torre

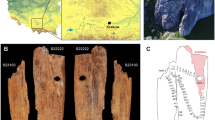

Torre cave is on the left bank of the River Oiartzun, in the municipality of Oiartzun (Gipuzkoa, Spain) (Fig. 1). It is 34 m above sea level and about 12 km from the modern coastline.

Location of Torre and Magdalenian sites mentioned in the text in northern Iberia. The Cantabrian region includes Basque Country (A), Cantabria (B) and Asturias (C). 1, Torre; 2, Ekain; 3, Urtiaga; 4, Ermittia; 5, Santa Catalina; 6, Lumentxa; 7, Santimamiñe; 8, Antoliñako Koba; 9, El Valle; 10, La Garma; 11, Rascaño; 12, El Juyo; 13, Las Chimeneas; 14, El Castillo; 15, Hornos de la Peña; 16, Altamira; 17, Cualventi; 18, Llonín; 19, Balmori; 20, Collubil; 21, Tito Bustillo; 22, La Güelga; 23, Las Caldas; 24, La Paloma; 25, Cueva Oscura de Ania; 26, Sofoxó. Western Europe topographic map (topography: NASA SRTMBO. relief: NGDC ETOPO1)

The cave formed in lithology belonging to the Liassic epoch of the Jurassic. Its small entrance faces west and is 0.8 m high and 1.5 m wide. It consists of a single narrow passage 9 m long, which ends at a 6-m shaft where several fauna remains were found (Fig. 2).

The deposit was discovered in 1966 by A. Laburu, with R. Gastón, E. Gastón, P. Ochoa and F. Ochoa in the course of a project of the prehistory department in Aranzadi Science Society to find and catalogue archaeological sites in Gipuzkoa. The engraved bird bone studied here was found on the cave’s floor at the time of its discovery. In 1967, L. Echaide, M. I. Bea and B. Izquierdo, together with the above-mentioned discoverers, performed an archaeological exploration of the cave and retrieved Upper Palaeolithic remains. In 1971, I. Barandiarán Maestu published a detailed iconographic study of the Torre tube, including an exceptionally good drawing of its engravings. Later, the deposit was excavated in 1982 and 1983 under the direction of J. Altuna (Altuna, 1983).

The stratigraphic sequence in Torre cave is quite limited and did not yield many archaeological remains. Although no radiocarbon dates are yet available, very sporadic occupations in the Gravettian, Solutrean and Magdalenian are attested to (Altuna, 1983).

Materials and Methods

The present study has been adapted mainly to the analytical terminology and methodology of the French school (Averbouh and Provenzano, 1998-99; Averbouh, 2000, 2016; Provenzano, 2004), which has also been largely followed by other researchers (e.g. Christensen, 1999; Goutas, 2004; Goutas & Tejero, 2016; Pétillon, 2006; Tartar, 2009; Tejero, 2010, 2013). We also follow the technical analysis of Palaeolithic art (Crémades, 1994; d’Errico, 1994; Fritz, 1999; Rivero, 2012, 2015, 2017).

The object of study is deposited in the GORDAILUA (Cultural Heritage Centre of Gipuzkoa, Irun, Spain). The macroscopic analysis was performed by observing the bone with the naked eye. The microscopic observation used a Nikon Eclipse 50i optical microscope (stereo-microscope up to × 70) and an Inspectis F30s digital microscope (stereo-microscope up to × 30). The tracings were made digitally from a photographic model created with a mosaic of photomicrographs at × 10, following the current standard methodology (Fritz & Tosello, 2007). The graphic units were discriminated by considering those that formed individual structures (zoomorphs, recognisable signs) or groupings of lines in the same area.

The first taxonomic and anatomic identification of the bone tube was made by J. Altuna (Barandiarán, 1971). The present study has confirmed this identification of using the reference collection in the Royal British Columbia Museum (Victoria, Canada).

Results

Raw Material

The Torre tube was made from the left ulna of a northern gannet (Morus bassanus) (Fig. 3). All the known tubes in the Palaeolithic archaeological record are made from bones and mostly from long bird bones (Averbouh, 1993, 2003a, 2003b). These bones possess flat surfaces, thin compact walls and a hollow medullar cavity (Absolon, 1937; Buisson, 1990). The object was found in two pieces because of an old break, and the two fragments were later joined together. The bone is 179 mm long and 10 mm wide with an average thickness of 1.2 mm; its cross-section is sub-circular (Fig. 4).

The ulna displays a fracture at its distal end and consequently lacks the distal epiphysis, whereas the proximal end preserves a part of the olecranon. The central hole can therefore be observed at both ends. Its general outline is straight, with a slight anatomical curve in the proximal part. The motifs appear on all sides of the bone, which is not pierced in any place.

Both the dorsal and the ventral surfaces contain areas with manganese impregnations that partly cover several motifs, although the figures can be seen correctly. In addition, at the proximal end of the epiphysis, two areas are altered taphonomically by rodent bites, characterised by channels of variable depth and length (e.g. d’Errico & Villa, 1997).

Remains of the northern gannet have not been found at many Upper Palaeolithic sites: Gruta da Figueira Brava (Portugal), Nerja (Spain), Ibex cave (Gibraltar) and Archi cave (Italy) (Boessneck et al., 1980; Cooper, 2000; Mourer-Chauvire & Antunes, 2000; Eastham, 2021). The northern gannet is a pelagic sea bird that lives in the North Atlantic in large colonies on cliffs or islands. After the breeding season, in winter, they migrate south along the coasts of the western Mediterranean (Fisher & Vevers, 1944). Torre cave is now about 12 km from the shore, although marine regression during the cold climate in the Magdalenian would have moved the coastline north by about 6 or 7 km opposite the mouth of the River Urola (Altuna & Merino, 1984) or by at least 10 km in the case of the River Oiartzun owing to the form of the continental shelf. Since the avifauna at the site has not been studied, the amount of accumulation of bird remains in the cave is not known and it cannot be determined whether the bone was transported to the cave or it was obtained and processed somewhere nearer the Magdalenian coast.

Debitage

The Torre tube was prepared before being engraved by modifying the bone only partially, as the proximal epiphysis was preserved (Mons & Pigeaud, 2014). Unlike other Palaeolithic tubes (e.g. La Vache (Clottes & Delporte, 2003), Le Placard (Clottes et al., 2010)), the epiphysis was not removed by sawing it off. In contrast, the distal epiphysis has not been preserved owing to a fracture. It would appear to be an accidental breakage judging by the fresh fracture plane. Because of this breakage, we do not know whether the original decorated object also preserved the distal epiphysis.

Decoration Process and Techniques

The surface of the left gannet ulna was previously prepared to regularise and eliminate the protuberances of the bone (Fig. 5). This process was made by scraping, as superficial longitudinal striations prove. Technical processes can often be identified in connection with the preparation of the surface of these types of objects, and a natural patina has been described on numerous specimens (Mons & Pigeaud, 2014).

The motifs were drawn in an order that is difficult to determine because of the few superimpositions between them (see the section “Motifs”). The technique used to produce the motifs on the Torre tube was by engraving lines that are generally deep with a V-shaped cross-section, combined with a more superficial engraving of details and several signs and notches. The figures occupy practically the whole available surface of the bone. The variety in the types of lines and their depth indicate the probable use of different lithic tools. Moreover, the breakage at the distal end of the bone may have removed small parts of some motifs, such as part of Motif 23.

The representations follow a similar pattern in all cases. The outlines of the figures and signs were made first by passing the tool several times to make deep grooves. The decorations formed by short lines and/or notches were always produced later, and it can sometimes be seen that the bone was turned over to make them. The artist possessed great cognitive ability, an aesthetic appreciation of visual regularity and lateralisation of motor functions.

Motifs

The identified motifs are described following the anatomical axis of the tube, from the proximal end to the distal end, beginning with the figurative representations, the animals and anthropomorph, and then the signs (Figs. 6 and 7).

-

Motif 1: The zoomorphic representation of a male deer (Cervus elaphus) consisting of the head (with a convex profile, maxillary line and open snout), the eye with caruncle, pointed ears with auditory canal, cervical-dorsal line and neck (Fig. 8 (1)). The antlers are represented by the frontal tine, second tine and part of the beam. The deer’s coat is shown by small deep marks, especially on the head, around the eye and jaw and along its back. Two prolongations seem to indicate the forelimbs of the deer, consisting of parallel lines. A line that crosses the animal’s chest (Motif 8) may represent a weapon or other objects, indicating that the animal was wounded. The stag was engraved by making a single groove that was deepened by passing the implement several times, and with single passings in the lines indicating the coat. The lines display different cross-sections: flat for the frontal-nasal line and maxilla and V-shaped for the lines of its coat.

-

Motif 2: Representation of a horse (Equus sp.). The head was drawn with a straight frontal line, snout, nostril, maxillary line, jaw with pronounced curvature and pointed ears (Fig. 8 (2)). The eye was engraved with the caruncle. The mane is represented by vertical lines, and the cervical-dorsal and neck-chest lines were also engraved. The coat was indicated by lines made with a single incision in the chin, head, neck and upper part of the animal’s back. One forelimb is represented by two parallel lines, while the belly bulges slightly (drawn with two parallel curves as a kind of internal division). It was engraved with a single groove, which is deeper in the horse’s outline and sensory organs, and by single incisions and notches in the lines indicating the coat and mane. The incisions are V-shaped.

-

Motif 3: Representation of a chamois (Rupicapra pyrenaica) consisting of the head with a concave profile (Fig. 8 (3)). The eye, snout, nostrils and pointed ears with auditory canal are represented. Six short vertical lines opposite the ears indicate a lock of hair. Two hook-shaped horns are drawn with juxtaposed parallel lines above the eye. The cervical-dorsal line, croup and neckline were also represented. The coat of the chamois is indicated with simple lines that show the different colours of the band that goes from the snout to the eyes and ears and continues along the animal’s neck to the forelimbs. Two forelimbs are represented by two convergent lines. Inside one leg, three vertical lines are spaced at regular distances and do not converge with the lines of the legs, while the other is represented by two convex lines that occupy part of the animal’s belly and extend as far as the centre of the Motif 7. It was engraved with a V-shaped cross-section and different depths. In the outline, the tool was passed several times at different depths, while for internal details and depiction of the coat, single passings were made.

-

Motif 4: Representation of an ibex (Capra pyrenaica). The head is depicted as a front view, indicated by an elongated triangle with convergent lines at the bottom. The ears and horns are shown on each side with divergent lines (Fig. 8 (4)). The horns are filled by short lines at regular distances, while another two shorter parallel lines may allude to the animal’s coat or mane. The cervical-dorsal line and the neck, together with the head, display short lines representing the ibex’s coat. In the animal’s belly, a probable leg completely flexed backward is drawn with two long convergent horizontal lines. In addition, above its back, four angles parallel to one another may be interpreted as an ibex in an inverse position. Their schematic form seems to suggest an unfinished figure. The ibex was engraved with a single V-shaped groove.

-

Motif 5: Representation of an ibex (Capra pyrenaica) consisting of a head as a front view (Fig. 8 (5)). The outline comprises the face represented by a single line and a series of short lines. As in the case of Motif 4, the ears and horns were depicted with divergent lines. It was engraved with a single V-shaped groove.

-

Motif 6: Representation of an aurochs (Bos primigenius). It is depicted with a head with a straight profile, maxillary line, snout, eye and caruncle, nostrils and mouth (Fig. 8 (6)). Two wide hairy ears are represented by short lines of different lengths. The horns are convex and point forwards, with lines that practically join. The cervical-dorsal line (a long diagonal line) and the neck are also shown. As in Motifs 3 and 4, the animal’s legs are depicted by parallel lines, and like the chamois, four short lines at regular distances were engraved inside one leg. Additionally, in the area of its belly, two vertical lines converge towards its neck. Its coat has been depicted with small deep lines, especially in its head, around the caruncle and jaw and along its back. It was created with a single groove of varying depths obtained by passing the engraving tool more frequently in its outline and only once in the details of its coat. The cross-section of the lines is V-shaped.

-

Motif 7: Representation of a male anthropomorph, with his head in profile, a round skull and a large forehead (Fig. 9). In the noticeable facial prognathism, both the nose (with nostril) and the chin are quite pronounced. The eye and eyelashes, neck, back and part of an arm are also depicted. In some areas (head, around the eye, back, chin and arms), short lines suggest the body hair of a male. Above his head, two practically convergent lines were engraved with numerous short lines around their distal ends. This has been interpreted as some kind of headdress with feathers (Barandiarán, 1971; Corchón, 1990), although the connection between these lines and the anthropomorph is not definite (the lines do not converge completely and are not superimposed on the outline of his head). It also differs from other examples of feathered headdresses in cave art (Jordá, 1970). We, therefore, have classified it as an individual sign (Motif 11). The anthropomorph was engraved with a single groove which is deeper in the outline, and lines drawn with a single incision representing the body hair. The cross-section of the engravings is V-shaped.

-

Motif 8: A curved line or loop was engraved below the neck of the deer (Motif 1). It consists of a single line that practically reaches the animal’s outline. Inside the deer and therefore in contact with its outline, another short line follows the direction of the first mark. A single oblique line of the same length was drawn under this second line. Together they form an open oval shape. They were drawn with wide, deep, V-shaped engraving (Fig. 10 (1)).

-

Motif 9: Eight slightly curved vertical lines at regular distances were drawn below Motif 8 (Fig. 10 (2)). They were made with a single incision of the engraving tool.

-

Motif 10: Several slightly oblique parallel lines that overlap the foreleg and belly of the male deer (Motif 1) (Fig. 10 (3)).

-

Motif 11: The sign located behind the deer (Motif 1) is formed by two converging lines creating a spindle shape. Short lines are seen around the distal end of the sign and some inside it. This sign has been associated with doubts about the figure of the anthropomorph and is described as a kind of headdress with feathers, although it might also be interpreted as a weapon over the deer (Fig. 10 (4)). It was engraved with a V-shaped cross-section.

-

Motif 12: The motif is formed by three slightly oblique parallel lines and six short lines that converge at their top (Fig. 10 (5)). It is located in front of the snout of the horse. It was engraved with deep incisions with a V-shaped cross-section.

-

Motif 13: A branching motif directly behind Motif 2 is formed by two slightly oblique parallel lines while, at their top, numerous short lines create a circular outline (Fig. 10 (6)). It was engraved with lines of medium depth.

-

Motif 14: Zigzag sign formed by three closed angles, located in front of Motif 4 and superimposed by Motif 15 (Fig. 10 (7)). It was engraved with lines of medium depth and a V-shaped cross-section.

-

Motif 15: Short deep line in front of the head of the chamois (Motif 3). This deep engraving has not been described in previous publications (Fig. 10 (8)).

-

Motif 16: Ladder-shaped sign formed by two parallel lines with short lines spaced at regular distances between them (Fig. 10 (9)). It is located below the figure of the chamois (Motif 3). Some of the lines extend beyond the parallel lines and are concentrated mostly at the lower end. It was engraved with lines of variable depth and a V-shaped cross-section.

-

Motif 17: Sign consisting of three parallel lines (Fig. 10 (10)). It was engraved with lines of medium depth and a V-shaped cross-section.

-

Motif 18: Adjacent spindle-shaped motifs formed by two convergent spindle shapes juxtaposed in the area of the withers of the aurochs (Fig. 10 (11)). It was engraved with lines of medium depth and a V-shaped cross-section.

-

Motif 19: Two parallel oblique lines directly above Motif 21. They were engraved with deep incisions with a V-shaped cross-section.

-

Motif 20: Two parallel oblique lines in front of Motif 19 and close to the breakage of the bone. Therefore, it is not known whether they originally continued in the distal part of the tube. They were engraved with deep incisions with a V-shaped cross-section.

-

Motif 21: Multiple zigzag signs formed by several convergent oblique lines (Fig. 10 (14)). They were engraved with deep incisions with a V-shaped cross-section.

-

Motif 22: Sign formed by rows of numerous traces engraved around the figure of the aurochs (Motif 6) (Fig. 10 (4)).

-

Motif 23: Sign formed by two parallel lines between Motif 22. Since it is right at the distal end of the bone, it is not known whether the breakage eliminated part of the sign (Fig. 10 (16)). This motif has not been described in previous publications.

The Rest of the Materials

Very few archaeological artefacts were found in the excavation directed by J. Altuna in 1982 and 1983 (Altuna, 1983). However, three objects made of antlers from the Magdalenian level are worthy of mention (Fig. 11). One of these (To.2: max. length 160 mm, max. width 14 mm) is the medial fragment of a projectile point (hunting weapon) with diagnostical functional fractures caused by impact (e.g. Pétillon, 2006) at its distal and proximal ends. A motif on its sides is formed by a series of convergent straight incisions. This is a common form of decoration during the Upper Palaeolithic, especially of projectile points and rods (Corchón, 1986). The other two objects (To.7H.219 and To.7H.194.1) are a distal fragment of a projectile point (max. length 25 mm, max. width 14 mm) and an awl (max. length 47 mm, max. width 3 mm) with a series of ten transversal lines spaced at regular distances on one of its faces.

Discussion

Bird long bones were often used to make tubes during prehistory in very diverse chronological and geographic settings (e.g. Absolon, 1937; Averbouh, 1993, 2003a, 2003b; Buisson, 1990; Eastham, 2021; Mons & Pigeaud, 2014; Davin et al., in revision). The consumption of birds by Neanderthal (Homo neanderthalensis) populations has been attested to in the Iberian Peninsula, for example at Bolomor (Blasco & Fernández Peris, 2009) and Cova Negra (Martínez Valle et al., 2016). Evidence is also present in Mousterian sites such as Gorham’s cave and Vanguard cave (Gibraltar), and Pié Lombard, Les Fieux and Abri des Pêcheurs (France) (Blasco et al., 2016; Finlayson et al., 2012; Laroulandie et al., 2016; Romero et al., 2017; Rufà et al., 2018). Bone bird’s alimentary exploitation has also been documented among anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens) during the Upper Palaeolithic (Bochenski et al., 2009; Eastham, 2021; Goffette et al., 2020; Laroulandie, 2004; Laroulandie et al., 2020; Wertz et al., 2016) and later periods. The use of bird bones as a raw material is equally known in all the Upper Palaeolithic cultures, from the Chatelperronian, as at Grotte du Renne, France (d’Errico et al., 1998a, 1998b), and Aurignacian, for example at Hohle Fels and Vogelherd (Conard et al., 2009), and Geißenklösterle (Münzel et al., 2002) (Germany) while their use intensified from the Gravettian onwards (Isturitz, Pair-non-Pair, Lespaux in France) (Buisson, 1990; Cousté & Krtolitza, 1961).

In the Iberian Peninsula, except for an Aurignacian specimen from the cave of La Garma A (Arias & Ontañón, 2004), the first bird tubes do not appear until the Solutrean, with most examples dated in the Magdalenian (Barandiarán, 1972; Corchón, 1986). Barandiarán (1967, 1971) sub-divided them into four groups (beads, simple tubes, perforated tubes and tubes with figurative decoration), based on technical and morphological criteria. The Torre tube would belong to the fourth sub-group, defined as ‘tubes with figurative decoration’. Most tubes display old breakages or sawn-off ends, although some fractures seem to have been deliberate (Averbouh, 1993; Laroulandie, 2004, 2006).

The Figurative Motifs

The Torre tube displays both figurative and non-figurative motifs along the bone. The former corresponds to different taxa: red deer, horse, chamois, aurochs and ibex. The depictions of the ibexes are stylised images as frontal views. The figure of the male deer, however, is formed by a realistic head with part of its antlers (see above) as observed in other red deer figures in Cantabrian Magdalenian portable art (e.g. El Castillo (Barandiarán, 1972; Corchón, 1986), El Pendo (Carballo, 1927; Montes Barquín, 1994), Cualventi (García Guinea, 1986), Ekain (Barandiarán & Altuna, 1977)) and Mediterranean portable art (Parpalló (Villaverde, 1994)). The male deer is also evidenced in the south of France (Lortet and Mas d’Azil (Chollot, 1964)). However, the proportion of male deer in Palaeolithic art is relatively small compared to that of other animals.

Motif 2 depicts a horse, represented by its head and the defining traits of this animal, like the jaw, the mane, pointed ears and hairs on its chin. The horse is the most frequently represented animal in European Palaeolithic cave art (Altuna, 2002; Sauvet & Wlodarczyk, 1995), and its dominance also extends to portable art (Sauvet, 2019). Horses have been represented in European portable art on different kinds of objects: on a bone spatula engraved with two horses in line (Moure, 1982a) and on a piece of slate (Moure, 1982b), both from Tito Bustillo cave; on bones used as hunting weapons from El Pendo (Carballo & Larín, 1933); on bone and plaques pieces in Parpalló (Villaverde, 1994; Villaverde et al., 2015); on a bird tube with two horses from El Valle (Cheyner and González Echegaray, 1964); and on a piece of red hematite from Lumentxa engraved with three horses (Barandiarán & Aranzadi, 1927, 1934), and horses are also engraved on lithic objects from Abauntz (Utrilla & Mazo, 1996) and Urtiaga (Barandiarán, 1947), among others. Depictions of horses also appear on portable art objects from France (Isturitz (Saint-Périer, 1936), La Madeleine (Chollot, 1980), Les Fadets (Airvaux, 2001), La Marche (Pales & Tassin de Saint-Péreuse, 1981)) , Germany (Saaleck (Bosinski, 1982), Knirgrotte (Feustel, 1974), Oelknitz (Feustel, 1987)) and Portugal (Foz do Medal (Soares De Figueiredo et al., 2020)).

In the middle of the tube, a chamois is represented in great detail, including the hair in front of its ears, the hook-shaped horns and the characteristic colour changes of its coat. Chamois are not often depicted in either cave art or portable art, although they were frequent prey at many Palaeolithic sites (Altuna, 1972, 1990). In the Iberian Peninsula, only two other examples have been described in portable art: on an engraved rib from Collubil (González Morales, 1977) and on several Parpalló plaquettes (Villaverde, 1994), whereas depictions are somewhat more numerous in parietal art (Spain: Altxerri, El Castillo, Las Chimeneas). Rather more examples are known of chamois in portable art in France, e.g. a pierced antler baton with four representations of chamois from Gourdan (Chollot, 1964), a bone disc from Laugerie-Basse (Roussot, 1984) and an antler baton with engravings of three anthropomorphs with chamois coats from Abri Mège (Darpeix, 1939), among others.

Motifs 4 and 5 are two stylised ibexes represented as frontal views. The head of one of them is represented by two convergent lines with the ears and horns above them, while the outline of the second consists of a single line and a series of short marks. The ibex as a frontal view is a motif that is thought to have originated in the Cantabrian region because of its abundance in that area (Rivero, 2012; Barandiarán et al., 2013) and is regarded as a chrono-cultural marker of the Upper-Final Magdalenian (González Sainz, 1993, 2005). It is a motif that has been found at numerous sites across the whole of northern Spain (Llonín (Fortea et al., 1992), Sofoxó (Corchón & Hoyos, 1972), El Valle (Cheyner and González Echegaray, 1964), El Pendo (Carballo & González Echegaray, 1952), Tito Bustillo (Moure, 1990), Urtiaga (Ruiz Idarraga & Berganza, 2008), Berroberria (Barandiarán et al., 2013), Abauntz (Utrilla & Mazo, 1996), Agarre (Arrizabalaga et al., in progress)). Schematic ibex in a frontal perspective have also been described at Pyrenean sites like Gourdan (Chollot, 1964) and La Vache (Clottes & Delporte, 2003) and other French locations such as Montgaudier (Duport, 1987).

Aurochs also appear among the animals in the Magdalenian figurative record, although they are not too common (Barandiarán, 1994; Sauvet, 2019; Weniger, 1999). On the Torre tube, an auroch is shown in a straight profile, with an eye and caruncle, wide hairy ears and horns pointing forwards. The convention of this representation is similar to that seen at other sites in northern Iberian, such as La Garma (Arias et al., 2008), Balmori (Vega del Sella, 1930), El Pendo (Carballo & González Echegaray, 1952) and Santa Catalina (Berganza & Ruiz Idarraga, 2004) or in the Mediterranean basin, as at Parpalló (Villaverde, 1994). Some other clear examples have come from Magdalenian sites in Europe: in Belgium (Trou de Chaleux: Lejeune, 1993), Italy (Polesini cave: Radmilli, 1974) and France (Rochereil: Paillet & Man-Estier, 2016), among others.

Motif 7 depicts a male anthropomorph with his head in profile, a globular skull and a large forehead. Within the wide iconography in Palaeolithic art, anthropomorphs stand out for their appearance as caricatures, unlike the naturalistic approach to zoomorphs, and they sometimes display details that create a hybrid or animal-like aspect (Clottes, 1987; Ripoll, 1958; Vialou, 1997). Moreover, these representations do not follow a systematised iconographic model (Corchón, 1998). More anthropomorphs are found in parietal art than on portable objects: the stones engraved with two anthropomorphs at Abauntz (Utrilla & Mazo, 1996); several engraved plaques and a spear-thrower with anthropomorphs, some of them possibly hybrid, at Las Caldas (Corchón, 1998); some possible human outlines on an antler baton from El Valle (Obermaier, 1925); and some doubtful figures engraved on plaques at Parpalló (Villaverde, 1994). In addition to these Iberian examples, representations of anthropomorphs have been found at such European sites as Isturitz (Saint-Perier, 1934), La Marche (Airvaux & Pradel, 1984), Mas d’Azil (Piette, 1902) and Raymonden (Marshack, 1972).

The fauna found in the deposit in Torre cave has not been studied in detail, although remains of red deer, reindeer and chamois have been cited (Altuna, 1983). It is, therefore, difficult to determine whether the animals engraved on the tube correspond to the prey that was usually hunted in the area. However, studies at coetaneous sites in northern Iberia appear to reflect a dichotomy in prey choice. In the Magdalenian, numerous sites located in valleys specialised in capturing red deer, whereas, in more mountainous places, they hunted ibex and chamois (Altuna, 1972, 1990; Yravedra, 2002a, 2002b). Thus, the Torre tube exhibits the preferred prey of Magdalenian hunter-gatherers, such as ibex (Ekain (Altuna & Mariezkurrena, 1984), Ermittia (Altuna, 1972), Praileaitz I (Castaños & Castaños, 2017), Rascaño (Altuna, 1981)) and red deer (Tito Bustillo (Altuna, 1976), Santimamiñe (Castaños, 1984), Aitzbitarte IV (Altuna, 1970), La Riera (Altuna, 1986), La Paloma (Castaños, 1980)), although there are exceptions where the two mentioned taxa are co-dominant in the Magdalenian fauna (El Mirón (Marín-Arroyo & Geiling, 2015)). However, it also displays animals that were consumed less often: horses, chamois and aurochs (Ekain (Altuna & Mariezkurrena, 1984), El Pendo (Fuentes Vidarte, 1980), La Riera (Altuna, 1986)). Therefore, depicting both the main prey and those hunted less or rarely may respond to a particular meaning that the artist wished to convey. Yet, as Altuna (1994: 310) explains, if the consumed and the represented species are compared, all the depicted animals were present in the proximities of the sites and, therefore, we should be cautious when considering the possible individual or symbolic connotations.

Non-figurative Motifs

The non-figurative decoration on the Torre tube can be divided into simple and complex signs. Motif 8 is a curved or loop-shaped sign, formed by a single curved line with two small curves at one end. This type of motif is relatively common in Palaeolithic art, both on portable objects (La Paloma, El Pendo) and in parietal art (Altamira, Hornos de la Peña, Tito Bustillo), mostly in the Upper Magdalenian (Corchón, 1986, 2004).

Another sign consists of eight slightly oblique parallel lines that form a graphic unit. This type of motif is very common throughout the Upper Palaeolithic on all kinds of objects (hunting weapons, domestic tools) but becomes increasingly frequent during the Magdalenian (Barandiarán, 1972).

Motif 11 is a spindle shape formed by two convergent curves with a series of short lines at its distal end; although some of them are inside the motif, they fail to form a ladder-like spindle (Corchón, 1986) as identified at other sites. In turn, Motif 18 consists of adjacent spindles, formed by two juxtaposed convergent spindle shapes.

Two branching motifs are seen on the tube (Motifs 12 and 13). Corchón (1986: 138) differentiates two variants within this kind of motif: typical and atypical branching forms. Both motifs on the Torre tube belong to the atypical variant as they are comprised of two or three more or less regular curves with a series of short lines at one end. This is a kind of sign that has been described sporadically at Solutrean and Magdalenian Spanish sites (Corchón, 1986), at El Otero, El Valle, El Pendo, and La Paloma (Barandiarán, 1972; Corchón, 1986).

Zigzag signs appear twice on the tube (Motifs 14 and 21). The former consists of three closed angles and is superimposed by Motif 16. The latter is formed by six closed angles. Within the theme of zigzag decoration, Motif 14 is classified in the dissociated variant, as none of the angles are juxtaposed, whereas the second is multiple zigzag formed by multiple convergent oblique lines (Corchón, 1986). The dissociated variant is one of the most common in Iberian Palaeolithic art, especially at Magdalenian sites and on projectile points and rods. The closest parallels have been found at Ermittia (Barandiarán, 1972), Abauntz (Utrilla & Mazo, 1996), Llonín, Altamira, La Paloma (Corchón, 1986) and Cova dels Blaus (Casabó et al., 1991). It has also been identified at more distant sites, like Laugerie-Basse (Breuil, 1936) and La Vache (Clottes & Delporte, 2003), France.

A ladder-like motif is formed by two parallel lines and other shorter ones spaced at regular distances. Following the proposal of Corchón (1986: 129), this would correspond to the irregular simple ladder variant, with the in-filling lines pointing in different directions. Ladder-like motifs, seen in both portable and parietal arts, diversify considerably in the Magdalenian. In the first phases of the period, they are associated mainly with projectile points and rods (Spain: Morín, El Pendo, La Paloma), whereas in the final phase of the Magdalenian, they appear on other types of objects, such as tubes like the Torre one (Corchón, 1986, 2004).

The Torre tube also displays rows of notches (Motif 22). Such marks are quite common in portable art in northern Iberia (Barandiarán, 1972; Corchón, 1986), where they are limited to the Solutrean and Upper Magdalenian (La Riera, Cueto de la Mina). Parallels of this type of motif can be found in older chronologies, mainly in the Aurignacian, at such European sites as Gorges-d’Enfer (Chollot, 1962), Abri Blanchard (Bourrillon et al., 2018; White, 1992), La Souquette (O'Hara et al., 2015) (France) and Vogelherd (Conard et al., 2003).

Motifs 10, 19 and 20 are comprised of parallel oblique and curved lines. Because of the fracture at the end of the tube, it is unknown whether they were part of a more complex composition.

Next to the break, a motif formed by two parallel transversal incisions was not included in the first study of the tube (Barandiarán, 1971). The fracture does not allow the full size of the motif to be known, although it appears to be a series of parallel lines (the start of a third incision is visible), similar to Motif 9. A series of parallel transversal lines is a typical motif in Palaeolithic art (Barandiarán, 1972; Corchón, 1986) and is found in practically the whole Upper Palaeolithic.

The figures on the Torre tube are arranged in two rows facing opposite directions and generally juxtaposed without any contact or superimpositions except in isolated cases. This arrangement resembles the juxtapositions of figures in vertical or horizontal rows, which is a classic composition mostly in the final phases of the Magdalenian (Corchón, 1986; Barandiarán, 1972). However, six examples of superimpositions can be observed. It can consequently be determined that the representations were produced in at least three stages, virtually filling up all the spaces on the tube (Fig. 12). Motifs 7 and 4 were probably the first to be engraved, and later Motif 5 was produced, superimposed on Motif 4, and also probably Motif 13. Next, Motif 3 was created in the centre of the tube, superimposed on Motif 7. It is possible that Motifs 1, 2 and 6 were also engraved in the process. Finally, the aurochs were superimposed on the stylised ibex (Motifs 4 and 5). Motif 22, which is located around the figure of the aurochs, must have been produced after it. The other motifs are isolated from the rest, which makes it impossible to determine the order in which they were created. However, as they are all signs, they were likely produced in the third stage of engraving. Owing to the unity in the arrangement of the representations and the similarities that can be observed, it is likely that these three stages were close to one another in time, and they may have been carried out by the same artist.

The integral study of all the engravings on the Torre tube shows iconographic and stylistic characteristics that are very similar to those observed at other coetaneous sites. One of the conventions of the figures on the tube is the mixed approach to the motifs, including figurative and realistic depictions, showing the animals’ coats and anatomical details like the ears and eyes with caruncles, etc., together with the classic stylised caprids. The figures are arranged in two rows oriented in different directions (red deer, horse and ibex towards the left, and anthropomorph, chamois and aurochs towards the right) and with forwarding projection of the heads. Moreover, identifying non-figurative motifs (branching and ladder-like signs, zigzags, rows of notches) is important because, in some cases, they fulfil a convention with a very precise attribution for portable art. Therefore, taken together, the figures display significant internal coherence and can be attributed unreservedly to the final phases of the Magdalenian (13,000 to 11,500 cal BP).

Functionality

Scholars have proposed a large number of functions for bone tubes: panpipes, containers for needles, whistles, containers for liquids, raw material for beads in the process of being made, instruments related to hunting (blowpipes, decoys), pieces used for games, ochre containers, aerographs, ornaments and even symbolic elements (Averbouh, 1993, 2003a, 2003b). However, there is still no clear consensus about the functionality of these objects, and they may have been utilised for symbolic-social purposes and not practical use.

Tubes have been found with remains of colouring matter inside them at such sites as Altamira (Spain) (Montes Barquín et al., 2004), Spy (Belgium) (De Puydt & Lohest, 1887), Les Cottés (Breuil, 1906) and Lascaux (France) (Couraud & Laming-Emperaire, 1979). In other locations (e.g. Cosautsi (Otte et al., 1996), Le Placard (Chauvet, 1910)), however, these tubes are associated with bone needles because they have been discovered with those utensils inside, suggesting that they were containers for a kind of sewing kit. Alternatively, bearing in mind the known importance of the generation of sound for hunter-gatherer communities (e.g. Buckley, 1998; Fitch, 2006; Bannan, 2012; Morley, 2013; Fritz et al., 2021; Colombo, 2022), it should be noted that the absence of holes does not rule them out as a kind of flute, as demonstrated by contemporary (Telenka or Tilinca and Koncovka: flutes without finger holes that are traditional instruments on Romania and Slovakia, respectively), archaeological (Shaham, 2012) and ethnographic (Clodoré-Tissot et al., 2009) instruments. Some of these functions were compiled by Averbouh (1993: 110) in a publication in which she discriminates three hypothetical functional groups: musical instruments, recipients and others (amulets, personal ornaments). Indeed, the discovery of different marks of use associated with these tubes supports the hypothesis that they were used for multiple purposes, some of which do not leave persistent use-wear within the everyday needs of our ancestors.

No type of evidence of use has been detected on the Torre tube, and traceological analyses have been unable to study this aspect in greater depth. However, it was found with an old fracture in its middle, which had broken it into two pieces of similar size. This has led some researchers, like Barandiarán (1971: 64), to suggest that it was a ritual object and claim, without affirming it altogether, that it had been broken intentionally: “The suggestion to its intentional rupture -in some ritualistic way- can only be offered with many reservations”. However, no type of previous preparation of its surface or clear marks of sawing or bending is visible.

Morphometric studies of these objects (Averbouh, 1993, 2003a, 2003b) have shown that the hunter-gatherer groups sought some particular characteristics, such as a minimum diameter or length of the bone. At La Vache, for example, an assemblage of five tubes that share morphometric characteristics and rich figurative decoration, attributed to the Upper-Final Magdalenian (Averbouh, 2003a, 2003b), presumably was used for the same purpose. However, the small number of tubes that have been found means that it is difficult to reach a reliable conclusion about the use of these objects, especially regarding their possible non-utilitarian significance (Averbouh, 2003a, 2003b; Barandiarán, 1971). Consequently, we must admit that we cannot assign a definite function to the Torre tube.

Parallels of the Torre Tube

Several objects similar to the Torre tube have been documented in the Iberian Peninsula (Fig. 13). In the immediate surroundings, two fragments of a tube, probably from the same bird bone, were found at Santimamiñe (González Sainz, 2011). The two pieces display non-figurative zigzag decoration. More abundant evidence comes from Altamira, with four specimens (Breuil & Obermaier, 1935; González Echegaray & Freeman, 1996). These are all bird bones, presumably their long bones. One tube displays several parallel transversal incisions. Moreover, three of these bones contain remains of ochre inside them and adhered to the surface of one of them and they have been interpreted as aerographs (Montes Barquín et al., 2004).

Tubes from the northern Iberian: Santimamiñe (1) (González Sainz, 2011); La Paloma (2) (Corchón, 1994); Altamira (3) (Álvarez Fernández, 2001); El Juyo (4) (Barandiarán et al., 1985); Rascaño (5) (González Echegaray & Barandiarán, 1981); Balmori (6) (Vega del Sella, 1930); Las Caldas (7) (Corchón & Ortega, 2017a); El Castillo (8) (Cabrera, 1984); La Güelga (9) (Menéndez & García, 1998)

A tube made from a bird radius was found at El Valle cave without stratigraphic context. It was decorated with several figures: two outlines of horses surrounded by fish shapes and a stylised stag (Obermaier, 1925; Cheyner & González Echegaray, 1964).

Another specimen classified as a tube came from El Castillo (Cabrera, 1984). It has a perforation and is decorated with three longitudinal lines and a series of short transversal lines. It was described by its discoverers as a whistle (Cabrera, 1984). Another fragment of a bird bone tube engraved with short, deep lines was retrieved at Rascaño (González Echegaray & Barandiarán, 1981). At the site of La Güelga, a tube fragment, also made from a bird bone, was decorated with a series of transversal incisions. Attributed chronoculturally to the Lower Magdalenian, it was described by its researchers as a flute (Menéndez & García, 1998).

Six tubes made from bird bones were found in the Magdalenian levels at El Juyo (Barandiarán et al., 1985). Short transversal lines, generally at regular distances, were engraved on five of the tubes, while two deep transversal grooves decorated each end of the other bone.

Also, in northern Iberia, a tube fragment from La Paloma was decorated by a series of parallel transversal incisions and lateral marks at its distal end (Corchón, 1986). Excavations in Sofoxó cave recovered a fragment of a possible tube with decoration on its dorsal face, consisting of four transversal lines at regular distances (Corchón & Hoyos, 1972). This object type was found at Las Caldas in both Solutrean and Magdalenian levels. In the former, a bird bone tube was engraved with deep incisions in the form of rings around the tube; it was interpreted as the matrix for manufacturing beads (Corchón & Ortega, 2017a). Another three bird bone tubes were documented, one of which was pierced by two holes in the line and which may have been the middle part of a flute (Corchón & Ortega, 2017a). Two bird bone tubes were identified in the Magdalenian occupations: one with a series of parallel oblique incisions on its dorsal face and two longitudinal curved lines on both sides of its fracture, and one that was interpreted as a possible bead (Corchón & Ortega, 2017b).

Other similar finds to the Torre tube include the bone of a long-legged bird found in Balmori cave, fully decorated with a series of transversal incisions in parallel bands (Vega del Sella, 1930). An engraved bone tube from the Lmb level, dated in the Upper Solutrean, at Antoliñako Koba, displays four perforations opposite each other in the same way as the flutes from Isturitz (Aguirre, 2000). Excavations at Cueva Oscura de Ania found two tubes with parallel linear decoration that was helicoidal on one of them and transversal on the other. Their whereabouts are now unknown (Adán Álvarez et al., 2007; Pérez Pérez, 1977). One of the oldest tubes is the engraved bird bone with transversal incisions found at La Garma A, in layer C, which is attributed to the Aurignacian (Arias & Ontañón, 2004). It has been classified as an element of adornment.

Therefore, apart from this last specimen, in northern Iberia, the bone tubes appear from the Solutrean onwards and, above all, during the Magdalenian. Although they are practically all fragmented, they are similar to one another in the choice of raw material (bird long bone shafts), decorative motifs (series of transversal line) and their size, particularly in their diameter. Only the tube found in El Valle cave and the one studied here display figurative motifs of zoomorphs. A few of them are pierced, and also functional hypotheses have been proposed for very few of them.

In the Mediterranean area, Cova dels Blaus presents stylistic similarities, concerning the signs, and chronological similarities to the Torre tube (Casabó et al., 1991).

In contrast, sites in the Pyrenees and Périgord have yielded a richer assemblage of engraved tubes. As many as 28 tubes have been recovered at La Vache. The raw materials were long bird bones, as in the Iberian Peninsula, mainly ulnae and radii of raptors such as vultures and eagles, long-legged birds and ravens (Mons & Pigeaud, 2014). Some of these are decorated with figurative motifs and signs. One tube displays a complete engraved scene: a figure of a horse surrounded by a small bear as a frontal view, a line of small figures in straight profile, the head of a fish and several schematic fish and the head of another zoomorph (Delporte, 1993). Sixteen tubes with figurative and geometric decorations were found in Magdalenian levels at Mas d’Azil (Mons & Pigeaud, 2014). Heads and bodies of red deer, horses and fish-shaped motifs were represented in a similar style to the Torre tube, for example by showing the details of the animals’ coats, eyes with caruncle and open mouths (Péquart & Péquart, 1960). Of eleven tubes found at Gourdan, one displays the representations of a stag, the head of an ibex, a fish and several plant motifs (Chollot, 1964). One of the sites that have yielded the largest number of perforated tubes is Isturitz (Buisson, 1990), with a total of 20 specimens dating from the Aurignacian to the Magdalenian, although most of them come from Gravettian levels. The average number of holes in complete or partly complete tubes is two, but the number may vary between one and four holes. These objects have been the subject of several types of studies, including experimental approaches (Buisson & Dartiguepeyrou, 1996; García Benito et al., 2016) that support their use as musical instruments.

Studying the motifs, techniques and stylistic traits of Upper Palaeolithic art offers a huge potential for research into social and cultural interactions. Correspondence factor analyses (CFA) applied to the artistic representations of hunter-gatherers have enriched our information about inter-connection patterns (Rivero & Sauvet, 2014; Sauvet & Wlodarczyk, 2008). They seem to indicate that the formal model of the representation of some animals, such as horses, with an indication of the tear caruncle and other details, was created and developed in the Pyrenees during the Middle Magdalenian. This model became more widespread as it expanded towards Aquitaine and northern Iberia during this period (Rivero & Sauvet, 2014) when the sociocultural exchange networks probably reached their maximum extension. This is observed not only by the geographic distribution of portable and parietal art lato sensu but also by other material evidence, such as flint varieties, shells and osseous industry (Álvarez Fernández, 2002; Corchón et al., 2009; Erostarbe-Tome et al., 2022). Although this representation model seems to have been largely limited to the Middle Magdalenian (Rivero & Sauvet, 2014), the Torre tube shows that the same stylistic conventions continued to be followed to some extent in the Upper-Final Magdalenian. Moreover, the tube exhibits other forms of representation, such as ibex as frontal views, which originated in northern Iberia (Rivero, 2012; Barandiarán et al., 2013). Therefore, the Torre tube combines regional and inter-regional motifs and models, denoting clear evidence of the connection between different human groups.

Conclusion

The Torre tube represents the most complex combination of themes in the portable repertory in northern Iberia. It is the most complete decorated tube to have been found, and despite appearing outside a stratigraphic context, the iconographic conventions and the treatment of the motifs mean that it can be unreservedly attributed to the Upper-Final Magdalenian. A left ulna of the northern gannet was used for it, a characteristic material for this kind of object. As explained above, although only one other tube with depictions of zoomorphs has been found in the Iberian Peninsula at Cueva de El Valle (Cheyner & González Echegaray, 1964), other typological parallels are known in France. Thus, clear characteristic traits were repeated in both areas in the last phases of the Magdalenian, such as the naturalistic treatment of the zoomorphs, the convention of stylised ibexes as a frontal view and the complex associations of subject matter (Barandiarán, 1972; Corchón, 1986). They demonstrate the connections that existed between different groups of hunter-gatherers and the circulation, on regional and inter-regional scales, of ideas, iconographic models and technical behaviour.

On the Torre tube, we find a complex composition with depictions in two rows facing in opposite directions, in which figures are combined with different conventions (differences in the colour of the coat, details like the caruncle and jaw, etc.) and morphotypes (stylised ibexes as a frontal view), as well as conventional signs (Barandiarán, 2015). In this way, in the Upper and Final Magdalenian, when the Torre tube was created, homoespecific groupings were produced (Barandiarán, 2003) with a clear scenic organisation. These depictions occupy the whole available space of the tube to create a peri-cylindrical decoration. The reappraisal of this tube is a contribution to the knowledge of portable art on hard animal matter in northern Iberia, which was densely populated in the Magdalenian. The study of these portable objects reveals aspects of artistic that are crucial to an understanding of Palaeolithic societies.

Data Availability

The authors confirm that all data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Absolon, C. (1937). Les flûtes paléolithiques de l’Aurignacien et du Magdalénien de Moravie: analyse musicale et ethnologique comparative avec démonstrations. Congrés Préhistorique de France. Compte-rendu de la XII ème session, Toulouse-Foix, 1936. Société Préhistorique Française, Paris

Adán Álvarez, G. E., García Sánchez, E., & Quesada López, J. M. (2007). Cueva Oscura de Ania. (Las Regueras, Asturias, España) y la definición del Aziliense antiguo: La industria ósea. Caesaraugusta, 78, 107–124.

Aguirre, M. (2000). El paleolítico de Antoliñako Koba (Gautegiz-Arteaga, Bizkaia): secuencia estratigráfica y dinámica. Illunzar, 4, 39–81.

Airvaux, J. (2001). L’art préhistorique du Poitou-Charentes : Sculptures et gravures des temps glaciaires. Éditions La Maison des roches.

Airvaux, J., & Pradel, L. (1984). Gravure d’une tête humaine de face dans le Magdalénien III de la Marche, commune de Lussac-les-Châteaux (Vienne). BSPF, 81(7), 212–215.

Albrecht, G., Holdermann, C.-S., & Serangeli, J. (2001). Towards an archaeological appraisal of specimen No 652 from the Middle-Palaeolithic Level D / (layer 8) of the Divje Babe I. Arheološki Vestnik, 52, 11–15.

Allain, J. (1950). Un appeau magdalénien. Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française LXVII, 181–192.

Altuna, J. (1970). Fauna de Mamiferos del Yacimiento Prehistórico de Aitzbitarte IV - (Rentería-Guipúzcoa). Munibe. Sociedad De Ciencias Naturales Aranzadi (san Sebastian), 22, 3–41.

Altuna, J. (1972). Fauna de mamíferos de los yacimientos prehistóricos de Guipúzcoa, con catálogo de los mamíferos cuaternarios del Cantábrico y del Pirineo occidental. Munibe. Sociedad De Ciencias Naturales Aranzadi (san Sebastian), 24, 1–464.

Altuna, J. (1976). Los mammiferos del yacimiento prehistorico de Tito Bustillo (Asturias). In: Moure Romanillo, J. A., Cano Herrera, M., (Eds.), Excavaciones en la cueva de Tito Bustillo (Asturias): trabajos de 1975. Oviedo: Diputación Provincial, Instituto de Estudios Asturianos del Patronato José M.a Quadrado, 149–189.

Altuna, J. (1981). Restos óseos del yacimiento prehistórico del Rascaño (Santander). In: González Echegaray, J., Freeman, G.L. (Eds.), El Paleolítico Superior de la cueva del Rascaño (Santander) Centro de Investigación y Museo de Altamira. Monografías 3, 221–269

Altuna, J. (1983). Cueva de Torre (Oyarzun, Guipúzcoa). III Campaña de Excavaciones. Arkeoikuska: Investigación arqueológica, 81–82, 34–35.

Altuna, J. (1986). The mammalian faunas from the prehistoric site of La Riera. In L. G. Straus & G. A. Clark (Eds.), La Riera Cave: Stone Age hunter-gatherer adaptations in northern Spain (pp. 237–274). Arizona State University Anthropological Research Papers.

Altuna, J. (1990). Caza y alimentación precedente de Macromamíferos durante el Paleolítico de Amalda. In: Altuna, J., Baldeón, A., Mariezkurrena, K. Cueva de Amalda (Zestoa, País Vasco). Ocupaciones Paleolíticas y Postpaleolíticas. Sociedad de Estudios Vascos Serie B 4, 149–192.

Altuna, J. (1994). La relación fauna consumida-fauna representada en el Paleolítico Superior cantábrico. Complutum, 5, 303–312.

Altuna, J. (2002). Los animales representados en el arte rupestre de la Península Ibérica Frecuencias de los mismos. Munibe (Antropologia-Arkeologia) 54 21–33

Altuna, J., & Mariezkurrena, K. (1984). Bases de subsistencia de origen animal en el yacimiento de Ekain. In J. Altuna, & J. Merino (Eds.), El yacimiento prehistórico de la cueva de Ekain (Deba, Guipúzcoa) (pp. 211–280). Sociedad de Estudios Vascos, Sociedad de Ciencias Aranzadi.

Altuna, J., & Merino, J. (1984). El yacimiento prehistórico de la cueva de Ekain (Deba, Guipúzcoa). Sociedad de Estudios Vascos, Sociedad de Ciencias Aranzadi.

Álvarez Fernández, E. (2001). “Altamira revisited”: Nuevos datos, interpretaciones y reflexiones sobre la industria ósea y la malacofauna. Espacio Tiempo Y Forma. Serie i, Prehistoria Y Arqueología, 14, 167–184. https://doi.org/10.5944/etfi.14.2001.4727

Álvarez Fernández, E. (2002). Perforated Homalopoma sanguineum from Tito Bustillo (Asturias): Mobility of Magdalenian groups in northern Spain. Antiquity, 76, 641–646. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003598X00091043

Arias, P., & Ontañón, R. (2004). La materia del lenguaje prehistórico. El arte mueble paleolítico de Cantabria en su contexto. Santander, Gobierno de Cantabria.

Arias, P., Ontañón, R., Álvarez Fernández, E., Cueto Rapado, M., García-Moncó, C., & Teira, L. C. (2008). Falange grabada de la Galería Inferior de La Garma: Aportación al estudio del arte mobiliar del Magdaleniense Medio. In J. Fernández Eraso, J. Santos (Eds.), Homenaje a Ignacio Barandiarán Maestu (pp. 97–129). Vitoria: Universidad del País Vasco (Veleia 24–25).

Averbouh, A., & Provenzano, N. (1998–99). Propositions pour une terminologie du travail préhistorique des matières osseuses I Les techniques Préhist Anthropol. Méditerranéennes 7, 1–28.

Averbouh, A. (1993). Tubes et etuis. In: Camps-Fabrer, H. (dir.), Fiches typologiques de l’industrie osseuse préhistorique, cahier VI : les éléments récepteurs, Treignes, CEDARC, 99–113.

Averbouh, A. (2000). Technologie de la matiére osseuse travaillée et implications palethnologiques. L’exemple des chaines d’explotation du bois de cérvide chez les Magdalenéniens des Pyrénées. Université Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne.

Averbouh, A. (2003a). Les tubes. In: Clottes, J., Delporte, H. (dir.), La Grotte de La Vache (Ariège), fouilles Romain Robert. I – Les occupations du Magdalénien. Paris, Editions de la Réunion des Musées Nationaux, CTHS: 343–352.

Averbouh, A. (2003b). Tubes et os d’oiseaux. In: Clottes, J. Delporte, H. (dir.), La Grotte de La Vache (Ariège), fouilles Romain Robert. II – L’art mobilier. Paris, Editions de la Réunion des Musées Nationaux, CTHS: 323–389.

Averbouh, A. (Ed.) (2016). Multilingual lexicon of bone industry, version 2 (FrançaisAnglais-Italien-Espagnol, Allemand, Hongrois, Polonais, Russe, Bulgare, Roumain, Portugais, Danois), GDRE PREHISTOS - ARCHAEOLOGICAL STUDIES II, Hors série Préhistoire de la Méditerranée, 131.

Bannan, N. (2012). Music, language, and human evolution. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199227341.001.0001

Barandiarán, J. M. (1947). Exploración de la cueva de Urtiaga (Itziar, Guipúzcoa), Eusko-Jakintza 113–128, 265–271, 437–456, 679–696.

Barandiarán, I. (1967). El Paleomesolítico del Pirineo Occidental. Monografías Arqueológicas III, Universidad de Zaragoza, Zaragoza.

Barandiarán, I. (1971). Hueso con grabados paleolíticos, en Torre (Oyarzun, Guipúzcoa). Munibe. Sociedad De Ciencias Naturales Aranzadi (san Sebastian), 1, 37–69.

Barandiarán, I. (1972). Arte mueble del paleolítico cantábrico. Universidad de Zaragoza.

Barandiarán, I. (1994). Arte mueble del Paleolitico cantábrico: Una visión de síntesis en 1994. Complutum, 5, 45–80.

Barandiarán, I. (2003). Grupos homoespecíficos en el imaginario mobiliar magdaleniense. Retratos de familia y cuadros de género. Veleia series minor nº 21. Universidad del País Vasco, Vitoria.

Barandiarán, I. (2015). Contextualización arqueológica de Covaciella: una Koiné pirenaico/cantábrica en el Magdaleniense medio. In: García Diez, M., Ochoa, B., Rodríguez Asensio, J. A. (eds.), Arte rupestre paleolítico en la cueva de La Covaciella (Inguanzo, Asturias), 126–144.

Barandiarán, J. M., & Aranzadi, T. (1927). Nuevos hallazgos de arte magdaleniense en Vizcaya (Santimamiñe. Lumentxa). Anuario de Eusko Folklore, 3(2), 3–6.

Barandiarán, J. M., & Aranzadi, T. (1934). Contribución del estudio del arte mobiliar magdaleniense del País Vasco (Santimamiñe, Lumentxa, Bolinkoba, Urtiaga). Anuario De Eusko Folklore, 14, 213–234.

Barandiarán, J. M., & Altuna, J. (1977). Excavaciones en Ekain (memoria de las campañas 1969–1975). Munibe. Sociedad De Ciencias Naturales Aranzadi (san Sebastian), 29, 3–58.

Barandiarán, I., González Echegaray, J., Freeman, L. G., & Klein, R. G. (1985). Excavaciones en la cueva de El Juyo. Cantabria: Centro de Investigación y Museo de Altamira, Monografías nº14.

Barandiarán, I., Cava, A., & Gundín, E. (2013). La cabra alerta: marcador gráfico del Magdaleniense cantábrico avanzado. In M. de la Rasilla, (Coord.): J. Fortea Pérez (Eds.), Universitatis Ovetensis Magister. Estudios en homenaje (pp. 263–286). Oviedo: Gobierno del Principado de Asturias et alii.

Berganza, E., & Ruiz Idarraga, R. (2004). Una piedra, un mundo. Un percutor de piedra decorado. Vitoria-Gasteiz: Diputación Foral de Álava.

Blasco, R., & Fernández Peris, J. (2009). Middle Pleistocene bird consumption at Level XI of Bolomor Cave (Valencia, Spain). Journal of Archaeological Science, 36, 2213–2223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2009.06.006

Blasco, R., Rosell, J., Rufà, A., Sánchez Marco, A., & Finlayson, C. (2016). Pigeons and choughs, a usual resource for the Neanderthals in Gibraltar. Quaternary International, 421, 62–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2015.10.040

Bochenski, Z. M., Tomek, T., Wilczyński, J., Svoboda, J., Wertz, K., & Wojtal, P. (2009). Fowling during the Gravettian: The avifauna of Pavlov I, the Czech Republic. Journal of Archaeological Science, 36, 2655–2665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2009.08.002

Boessneck, J., Driesch, A. V., & den. (1980). Tierknochenfunde aus vier südspanischen Höhlen. Studien Über Frühe Tierknochenfunde Von Der Iberischen Halbinsel, 7, 1–83.

Bosinski, G. (1982). Die Kunst der Eiszeit in Deutschland und in der Schweiz, Kataloge vor- und frühgeschichtlicher Altertümer 20. Bonn.

Bourrillon, R., White, R., Tartar, E., Chiotti, L., Mensan, R., Clark, A., Castel, J.-C., Cretin, C., Higham, T., Morala, A., Ranlett, S., Sisk, M., Devièse, T., & Comeskey, D. J. (2018). A new Aurignacian engraving from Abri Blanchard, France: Implications for understanding Aurignacian graphic expression in Western and Central Europe. Quaternary International, 491, 46–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2016.09.063

Breuil, H. (1906). Les Cottés, une grotte du vieil age du renne, a Saint-Pierre de Maillé (Vienne). Revue De L’ecole D’anthropologie De París, 16, 47–62.

Breuil, H. (1936). Oeuvres d’art magdaléniennes de Laugerie-Basse (Dordogne). Actualités Scientifiques et Industrielles, 382, 1–13.

Breuil, H., & Obermaier, H. (1935). La cueva de Altamira en Santillana del Mar. Tipografía de Archivos.

Buckley, A. (1998). Hearing the past: Essays in historical ethnomusicology and the archaeology of sound. Liège, Belgium: Université de Liège.

Buisson, D. (1990). Les flûtes paléolithiques d’Isturitz (Pyrénées Atlantiques). Bulletin De La Société Préhistorique Française, 87, 420–433.

Buisson, D., & Dartiguepeyrou, S. (1996). Fabriquer une flûte au Paléolithique Supérieur. Récit D’une Expérimentation. Antiquités Nationales, 28, 145–148.

Cabrera, V. (1984). El Yacimiento de la Cueva de El Castillo (Puente Viesgo, Santander). Biblioteca Prehistórica Hispana, XXII.

Carballo, J. (1927). Bastón de mando prehistórico procedente de la caverna de “El Pendo” (Santander), Santander.

Carballo, J., & Larín, B. (1933). Exploración en la gruta de El Pendo (Santander) (p. 123). Madrid: Junta Superior de Excavaciones y Antigüedades.

Carballo, J., & González Echegaray, J. (1952). Algunos objetos inéditos de la Cueva de El Pendo. In Ampurias (Vol. XIV, pp. 38–48). Núm.

Casabó, J., Grangel, E., Portell, E., & Ulloa, P. (1991). Nueva pieza de arte mueble paleolítico en la provincia de Castellón. Saguntum. Papeles Del Laboratorio De Arqueología De Valencia, 24, 131–136.

Castaños, P. (1984). Estudio de los macromamíferos de la cueva de Santimamiñe (Vizcaya). Kobie, 14, 235–318.

Castaños, P., & Castaños, J. (2017). Estudio de la fauna de macromamíferos del yacimiento de Praileaitz I (Deba, Gipuzkoa). In X. Peñalver, S. San Jose, J. A. Mujika (Eds.), La Cueva de Praileaitz I (Deba, Gipuzkoa, Euskal Herria) Intervención Arqueológica 2000–2009 (Vol. 1, pp. 221–265). Munibe Monographs, Anthropology and Archaeology Series.

Castaños, P. (1980). La macrofauna de la cueva de La Paloma (Pleistoceno terminal de Asturias). In: Hoyos Gómez, M., Martínez Navarrete, M.I., Chapa Brunet, T., Castaños P., Sanchíz, F.B., La cueva de La Paloma. Soto de las Regueras (Asturias). Excavaciones Arqueológicas en España, 67–108.

Chase, P. G., & Nowell, A. (1998). Taphonomy of a suggested Middle Paleolithic bone flute from Slovenia. Current Anthropology, 39(4), 549–553. https://doi.org/10.1086/204771

Chauvet, G. (1910). Os, ivoires et bois de renne ouvrés de la Charente. Hypothèses palethnographiques. Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société archéologique et historique de la Charente (8° série) I, 1–184.

Cheyner, A., & González Echegaray, J. (1964). La Grotte de Valle. In E. Ripoll Perello (Eds.), Miscelánea en Homenaje al Abate Breuil (pp. 327–345). Tomo I: Diputación Provincial de Barcelona.

Chollot, M. (1962). L’art mobilier préhistorique en France. Actes 6 Congrès U.I.S.P.P., Rome.

Chollot, M. (1964). Musée des Antiquités Nationales. Collection Piette. Art mobilier Préhistorique. Paris: Éd. des Musées Nationaux.

Chollot, M. (1980). Les origines du graphisme symbolique. Essai d’analyse des écritures primitives en Préhistoire. Fondation Singer-Polignac, Paris.

Christensen, M. (1999). Technologie de l’ivoire au Paléolithique supérieur: caractérisation physico-chimique du matériau et analyse foctionnelle des outils de transformation. BAR International Series 751. Hadrian Books, Oxford.

Clodoré-Tissot T., Le Gonidec M-B., Ramseyer D., & Anderes C. (2009). Instruments sonores du Néolithique à l’aube de l’Antiquité, Cahier XII (fiches de la Commission de nomenclature sur la l’industrie de l’os préhistorique) (p. 87). Paris: Ed. De la Société Préhistorique Française.

Clottes, J. (1987). La determinación de las representaciones humanas y animales en el arte paleolítico europeo. Bajo Aragón, Prehistoria VII-VIII, 1986–1987, 42–68.

Clottes, J., & Delporte, H. (2003). La grotte de La Vache (Ariège). París: Éditions de la Reunión des Musées Nationaux.

Clottes, J., Duport, L., Feruglio, V., & Le Guillou, Y. (2010). La grotte du Placard à Vilhonneur (Charente) (Fouilles 1990–1995). In J. Buisson-Catil, J. Primault, (Eds.), Préhistoire entre Vienne et Charente. Hommes et sociétés du Paléolithique. (Vol. XXXVIII, pp. 345–358). Mémoire: Association des Publications Chauvinoises.

Colombo, B. (ed.) (2022). The musical neurons. Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-08132-3_3

Conard, N. J., Niven, L., Mueller, K., & Stuart, A. (2003). The chronostratigraphy of the Upper Paleolithic deposits at Vogelherd. Mitteilungen Der Gesellschaft Für Urgeschichte, 12, 73–86.

Conard, N. J., Malina, M., & Münzel, S. C. (2009). New flutes document the earliest musical tradition in southwestern Germany. Nature, 460, 737–740. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08169

Cooper, J. H. (2000). A preliminary report on the Pleistocene avifauna of Ibex cave, Gibraltar. In: Finlayson, J. C., Fa, D. (eds.): Gibraltar during the Quaternary. (pp. 227–232). Gibraltar Government Heritage Publications.

Corchón, M. S. (1986). El Arte Mueble Paleolítico Cantábrico: contexto y análisis interno. Museo y Centro de Investigación de Altamira, Monografía 16. Ministerio de Cultura, Madrid.

Corchón, M. S. (1990). Iconografía de las representaciones antropomorfas paleolíticas: A propósito de la «Venus» Magdaleniense de Las Caldas (Asturias). Zephyrus XLIII, 17–37.

Corchón, M. S. (1994). Últimos hallazgos y nuevas interpretaciones del arte mueble paleolítico en el occidente asturiano. Complutum, 5, 235–264.

Corchón, M. S. (1998). Nuevas representaciones de antropomorfos en el Magdaleniense Medio Cantábrico. Zephyrus, 51, 35–60.

Corchón, M. S. (2004). El arte mueble paleolítico en la Cornisa Cantábrica y su prolongación en el Epipaleolítico. Kobie. Serie Anejos, 8, 425–474.

Corchón, M. S. (2018). La cueva de Las Caldas (Priorio, Oviedo). Ocupaciones magdalenienses en el valle del Nalón. Salamanca: Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca.

Corchón, M. S., & Hoyos, M. (1972). La Cueva de Sofoxó (Las Regueras, Asturias). Zephyrus, 23, 39–102.

Couraud, C., & Laming-Emperaire, A. (1979). Les colorants. In A. Leroi-Gourhan, J. Allain (Eds.), Lascaux inconnu. XIIe Supplément à Gallia Préhistoire (pp. 153–169). Paris: Centre National de Recherche Scientifique.

Corchón, M. S., & Ortega, P. (2017a). Los niveles solutrense de la Sala I de la cueva de Las Caldas (25000–21000 cal BP). Industrias y arte mueble. In M. S. Corchón (Ed.), La Cueva de Las Caldas (Priorio, Oviedo): ocupaciones solutrenses, análisis espaciales y arte parietal (pp. 35–189). Universidad de Salamanca.

Corchón, M. S., & Ortega, P. (2017b). Las industrias líticas y óseas (17,000–14,500 BP). Tipología, tecnología y materias primas. In M. S. Corchón (Ed.), Las cuevas de Las Caldas (Priorio, Oviedo): ocupaciones magdalenienses en el Valle del Nalón (pp. 247–556). Universidad de Salamanca.

Corchón, M. S., Tarriño, A., & Martínez, J. (2009). Mobilité, territoires et relations culturelles au début du Magdalénien moyen cantabrique: Nouvelles perspectives. In F. Djindjian, J. Kozłowski, & N. Bicho (Eds.), Le concept de territoires dans le Paléolithique supérieur européen (Actes du XV congrès de l’UISPP, Lisbonne, 2006) (British Archaeological Reports international series 1938) (pp. 217–230). Archaeopress.

Cousté, R., & Krtolitza, Y. (1961). La flûte paléolithique de l’abri Lespaux à Saint-Quentin de Baron (Gironde). Bulletin De La Société Préhistorique Française, 58(1–2), 28–30.

Crémades, M. (1994). L’Art mobilier Paléolithique: analyse des procédés technologiques. In: Chapa, T., Menéndez, M. (eds.), Arte Paleolítico. Complutum, 5, 369–384.

d’Errico, F. (1994). L’Art gravé azilien. De la technique à la signification. Gallia Préhistoire, supplément XXXI. Eds. du CNRS, Paris.

d’Errico, F., & Villa, P. (1997). Holes and grooves: The contribution of microscopy and taphonomy to the problem of art origins. Journal of Human Evolution, 33, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1006/jhev.1997.0141

d’Errico, F., Zilhão, J., Julien, M., Baffier, D., & Pelegrin, J. (1998a). Neanderthal acculturation in Western Europe? A critical review of the evidence and its interpretation. Current Anthropology, 39, 1–44. https://doi.org/10.1086/204689

d’Errico, F., Villa, P., Pinto, A., & Idarraga, R. A. (1998b). Middle Paleolithic origin of music? Using cave-bear bone accumulations to assess the Divje Babe I bone ‘flute.’ Antiquity, 72, 65–79. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003598X00086282

d’Errico, F., Henshilwood, C., Lawson, G., Vanhaeren, M., Tillier, A.-M., Soressi, M., Bresson, F., Maureille, B., Nowell, A., Lakarra, J., Backwell, L., & Julien, M. (2003). Archaeological evidence for the emergence of language, symbolism, and music–An alternative multidisciplinary perspective. Journal of World Prehistory, 17(1), 1–70. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023980201043

Darpeix, A. (1939). Sur l’interprétation des figurations anthropomorphes du Paléolithique supérieur. Bulletin De La Société Historique Et Archéologique Du Périgord, 66, 1–22.

Davin, L., Tejero, J.-M., Simmons, T., Shaham, D., Borbon, A., Tourny, O., Bridault, A., Rabinovich, R., Sindel, M., Khalaily, H., & Valla, F. R. (in revision). Prehistoric sounds at the transition to agriculture: Bone aerophones from the final Natufian of Eynan – Mallaha (Upper Jordan Valley, Israel). Nature.

de la Vega Del Sella, C. (1930). Las cuevas de La Riera y Balmori (Asturias), Memoria Comisión de Investigaciones Paleontológicas y Prehistóricas, 38.

De Puydt, M., & Lohest, M. (1887). L’homme contemporain du Mammouth à Spy (Namur). Annales de la Fédération archéologique et historique de Belgique. Compte rendu des travaux du Congrès tenu à Namur les 17–19 août 1886, 2, 207–240.

Déchelette, J. (1924). Manuel d’Archéologie Préhistorique, Celtique et Gallo-romaine (Vol. 2). Picard.

Delporte, H. (1993). L’art mobilier de la Grotte de la Vache : Premier essai de vue générale. Bulletin De La Société Prehistorique Française, 90, 131–136.

Diedrich, C. (2015). ‘Neanderthal bone flutes’: Simply products of Ice Age spotted hyena scavenging activities on cave bear cubs in European cave bear dens. Royal Society Open Science, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.140022.

Duport, L. (1987). Grotte de Montgaudier, commune de Montbron (Charente). Le foyer et les gravures magdaléniennes. In: Vandermeersch, B. (ed.), Préhistoire de Poitou-Charentes : problèmes actuels. Actes du 111º Congrès national des Sociétés savantes, Poitiers 1986, 37–48. Paris: Editions du C.T.H.S.

Eastham, A. (2021). Man and bird in the Palaeolithic of Western Europe. Archaeopress Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv25wxc7m

Erostarbe-Tome, A., Tejero, J. M., & Arrizabalaga, A. (2022). Technical and conceptual behaviours of bone and antler exploitation of last hunter-gatherers in northern Iberia The osseous industry from the Magdalenian layers of Ekain cave (Basque Country, Spain). Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 41, 103329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2021.103329

Feustel, R. (1987). Eiszeitkunst in Thüringen. In H. Müller-Beck & G. Albrecht (Eds.), Die Anfänge der Kunst vor 30 000 Jahren (pp. 60–63). Konrad Theiss.