Abstract

Previous studies have linked experiences with chance events to shifts in career intentions, but they have not investigated chance events as agents of career shifts in graduate students. This study investigated the types of chance events and perceived impacts of those events on the career intentions of life science graduate students at a university in the southeastern United States. We used a survey to investigate three questions: (1) Do life science graduate students experience chance events, and if so, what types of chance events were most common? (2) What is the relationship between impact level and valence of chance events on participants’ career intentions? (3) How do participants describe the impacts of chance events on their career intentions? Of the 39 respondents, 92% reported a chance event during graduate school, with 85% reporting high impacts on their career intentions; none perceived these impacts as solely negative. Participants described chance events’ impacts on their careers as presenting challenges, affording insights, spurring evaluations, and providing opportunities. These findings highlight the positive opportunities chance events may provide graduate students. Understanding how these events shape career intentions can inform career development resources that empower graduate students to see chance events as opportunities for growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Whether graduate students intend to pursue a traditional academic career or an alternative career, such as in government or industry, a shift in career intentions in graduate school is relatively common. Research highlights that graduate students’ confidence in their career path declines within the first 2 years of doctoral training, with significant shifts in career intentions in their third year (Fuhrmann et al., 2011). Others have documented a significant decline in graduate students’ initial career interests by later stages of their programs (Roach & Sauermann, 2017; Sauermann & Roach, 2012).

While many graduate students, particularly in the sciences, initially have career goals of becoming a faculty member (Austin & McDaniels, 2006; Zimmerman, 2018), it is increasingly apparent that graduate school does not always lead to an academic career (Gemme and Gingras, 2012). A rising percentage of graduate students in biomedical programs, for example, are choosing to pursue careers outside of academia (St. Clair et al., 2017; Wood et al., 2020) despite some perceptions that this represents a failure (Sherman et al., 2021; Shmatko et al., 2020; Zimmerman, 2018). Thus, there is evidence of increasingly diverse career intentions and career intention shifts of graduate students, but less information to explain why this is happening.

Investigations into why graduate students might reconsider their career intentions have often focused on perceptions of deficits. A deficit approach emphasizes student perceptions of low self-efficacy, declining motivation, difficulty obtaining research funding, low sense of belonging, workload expectations, identity conflict, and the lack of skills required for diverse careers (Alberts et al., 2014; Hardré et al., 2019; Roach & Sauermann, 2017; Sauermann, 2005). These factors are often associated with changes in career intentions (Byars-Winston et al., 2014; Cabrera et al., 2001; Fuhrmann et al., 2011; Shmatko et al., 2020; Wood et al., 2020), yet there has been less focus on the events that underlie these deficit perceptions. Additionally, few focus on positive factors associated with career shifts. For example, graduate students may experience empowering and transformative moments in graduate school that cultivate the exploration of new careers.

Unexpected and unplanned (chance) events happen throughout a graduate student’s degree program, and these events are known to alter career intentions in many populations (Bright et al., 2005; Hirschi, 2010; Kindsiko & Baruch, 2019; Rojewski, 1999; Salomone & Slaney, 1981; Scott & Hatalla, 1990; Williams et al., 1998). Although research on chance events has been conducted on undergraduate students (Bright et al., 2005) and post-doctoral students (Kindsiko & Baruch, 2019), there has been much less focus on graduate students. McCulloch (2021) investigated the positive impacts of chance events on graduate student research; however, the work did not explore chance events broadly and how they impacted career outcomes. Therefore, to our knowledge, there are no studies specifically focusing on how graduate students experience, react to, and perceive the outcomes of unexpected experiences on their career paths. This research is important because divergences from intended career paths can be a source of anxiety for undergraduate students (Beiter et al., 2015; Deer et al., 2018) and may generate similar feelings of anxiety for graduate students.

This study investigated the perception and impact of unpredictable or unplanned events—also known as chance events—on life science graduate students. It also analyzed perceptions of impact levels, the valence of their emotional reactions (whether they felt negatively, positively, or neutral about the event), and examples of career impacts. In so doing, we hoped to highlight the need for resources to support responses to chance events.

Theoretical Framework: Chance Events, Career Paths, and Their Role in Graduate Education

Chance Events

Defining a “chance event” can be a challenge because of the multiple terms and definitions associated with them. For example, serendipity, luck, synchronicity, and happenstance (Bright et al., 2005) each imply different experiences or outcomes of the chance event (Alcock, 2010; McCulloch, 2021). Serendipity, happenstance, and luck assume a positive outcome of the chance event, whereas chance events in the broadest sense may have a positive, negative, or neutral outcome valence. Synchronicity—often used in place of chance—assumes that when multiple events occur simultaneously, it is fate linking them together. Due to the variation in terminology used to describe chance events, we provided one definition of chance events to our participants throughout the entirety of the study: chance events are unplanned and unpredictable events. This decision helped to control the potential differences in the definition of a chance event and allowed us to examine the variability in perceptions of the impacts and outcomes of these events among graduate students.

Individuals may differ in their perception of the impacts and outcomes of chance events based on their anticipation of a particular circumstance or tolerance for unexpected outcomes. Whether an individual finds an event to be “unplanned” or “unpredictable” depends on the extent to which they anticipated the event occurring. Some graduate students may have anticipated failed experiments and would not consider them a chance event, while others may attribute any research failure as a chance event. A student’s perception of unpredictability may also be based on their level of perceived control over the outcomes (Rojewski, 1999). Some may feel unprepared to react to the event while others may feel confident in their ability to influence the outcome. This continuum of individual perceptions of controllability may shape how individuals interpret and evaluate the event’s significance (Cabral & Salomone, 1990) and whether they view it as positively or negatively impacting their career trajectory. An unexpected event that a student feels they can control and does not impact their career may be forgotten. However, an unexpected event that another student feels incapable of controlling and greatly impacts their career may loom large in their memories. This introduces variability in both recall of chance events and perceptions of their impacts on careers.

Chance Events and Career Paths

Researchers previously investigated how chance events influenced career paths in a wide range of participants. These studies included individuals external to academia (i.e., nonprofessional workers, vocational and high school students, or those with disabilities) as well as those currently pursuing an undergraduate degree or having completed a graduate degree (i.e., college students and those who had obtained their Ph.D. or master’s degrees) (Bright et al., 2005; Hirschi, 2010; Kindsiko & Baruch, 2019; Rojewski, 1999; Salomone & Slaney, 1981; Scott & Hatalla, 1990; Williams et al., 1998). These studies found that chance events were important factors in career thinking. However, one notable group has been excluded from these investigations of chance events and career outcomes: graduate students.

While it is possible that chance events would have similar impacts on graduate students as those in other academic studies, graduate students are a unique population at universities. They have intersecting identities as students, teachers, and researchers, which makes them different from undergraduate students (Winstone & Moore, 2017). Like undergraduate students, graduate students are still in school to obtain a degree, but they have a more focused area of study. In comparison to faculty members and post-doctoral scholars, they do not yet have their terminal degree and may still experience fluctuations in their career intentions (Roach & Sauermann, 2017; Sauermann & Roach, 2012). Graduate students reside in a transitional space (Reid & Gardner, 2020), making them unique from others in academic settings and suggesting that their reactions to chance events may also be unique. Thus, there is a need to explore any relationships between chance events and changes in career intentions in this population.

Planned Happenstance Learning Theory

Building on the foundations of the Learning Theory of Career Counseling (Krumboltz, 1996) and the Social Learning Theory (Krumboltz et al., 1976), the Planned Happenstance Learning Theory (PHLT) provides a unique perspective by integrating chance events as factors that influence career decisions. The PHLT highlights the overall importance of actively engaging with and reframing chance events into opportunities for learning and growth (Mitchell et al., 1999). The theory recognizes that a range of factors—such as personal interests, values, skills, and financial stability—both planned and unplanned, influence career paths. By integrating these factors with chance events, this theory gives insight into the process in which individuals navigate change and make certain career decisions (Krumboltz, 2009).

In PHLT, the individual is at the framework’s core, signifying their active role in shaping their career paths and personal lives. This theory recognizes that both intrinsic (i.e., previous learning experiences) and extrinsic (i.e., environmental conditions) factors influence the unique journey of each individual (Krumboltz, 2009; Mitchell et al., 1999), including how they perceive and act on chance events. In this theory, the utilization of five key skills—curiosity, persistence, flexibility, optimism, and risk-taking—plays a crucial role in an individual’s ability to adapt and engage with chance events (Eissenstat & Nadermann, 2018; Mitchell et al., 1999; Valickas et al., 2019). For example, if individuals are curious, they are more inclined to seek new experiences due to the chance event. Persistence enables the individual to be resilient when faced with challenges or difficulties, thus increasing their probability of navigating new circumstances. Flexibility allows individuals to adapt to challenges or difficulties resulting from chance events. Optimism brings a positive belief in ability, while risk-taking encourages the individual to step outside their comfort zone and embrace change as a part of their overall growth. Within the context of PHLT, these skills are seen as innate but can be developed over time. Furthermore, these skills positively impact how individuals interact with chance events and increase the likelihood of growth and success in their careers and personal lives (Krumboltz et al., 2013).

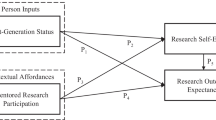

Unlike traditional career theories, Planned Happenstance Learning Theory is a useful framework to guide this study because it recognizes the unpredictability of graduate education and posits positive reactions to these circumstances. However, we also wanted to acknowledge that outcomes to a chance event might differ in valence—some students might perceive a chance event as negative (perhaps resulting in deficit feelings) and some might perceive it as a positive catalyst for career change. Thus, we added valence to the PHLT to guide our study (Fig. 1).

Chance events and the Planned Happenstance Learning Theory. The figure shows how an individual interacts and processes a chance event which is initially influenced by intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Processing the chance event is often mediated by the five skills (curiosity, persistence, flexibility, optimism, and risk-taking). The utilization of these skills may determine whether these chance events are framed as opportunities (positive perceptions) or as obstacles (negative perceptions), potentially influencing the individual’s interpretation of the chance event

Rationale and Research Questions

A multitude of factors, such as perceptions of interest, self-efficacy, and locus of control, may influence how individuals perceive or react to chance events (Bright et al., 2005, 2009; Hirschi, 2010; Rojewski, 1999; Williams et al., 1998). Hirschi and Valero’s (2017) research elaborated that work motivation specific to person-job fit and self-efficacy, and work engagement also mediate reactions. Therefore, it is important to understand not only the occurrence of events but also the perceived valence and impact on an individual’s career intentions when assessing their responses to chance events (Roseman, 2001, p. 89).

This study surveyed life science graduate students at the University of Tennessee about their recall and perceptions of chance events within their programs and how they saw these events shaping their career intentions. Our goal was to explore whether this unique group of students, positioned in a transitional and dynamic academic context, perceived that chance events shifted their career intentions, and if so, how? Thus, this study asked the following research questions:

-

1. Do life science graduate students experience chance events, and if so, what types of chance events are most common?

-

2. What is the relationship between impact level and valence of chance events on participants’ career intentions?

-

3. How do participants describe the impacts of chance events on their career intentions?

By exploring the impacts of chance events on life science graduate students, we can better understand how graduate students reflect on and navigate unplanned and unexpected challenges to their career intentions and use this information to inform programmatic support for these students.

Methods

This study was exploratory in nature, not because chance events have not been studied before, but because the population of interest—graduate students—had not been asked about chance events in relation to their career intentions before. An exploratory study seeks to lay the foundation for future work, using the data to determine whether and how to proceed (Hallingberg et al., 2018). In exploratory studies, especially using surveys, the goal is often not to select a large random sample of the population; instead, researchers select a smaller group of individuals who have deep understanding of the context or phenomena under investigation (Sue & Ritter, 2007). Therefore, we choose to select life science graduate students at one research-intensive university for this study.

This study—including its design, recruitment, and analysis methods—was approved by the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Institutional Review Board (UTK IRB-21–06521). Qualtrics Survey Software was used to collect data for the pilot survey and the final survey. Written consent was waived for this study. Instead, participants were provided with a description of the study and asked to indicate their agreement to participate by checking “Yes” or “No” before proceeding with the survey.

Survey Creation and Validation

A pilot survey was created and sent to graduate students who were in a STEM, but not life science, program at the institution. The purpose of this pilot survey was to see whether graduate students recalled chance events, assess participant interpretation of the questions, and identify potential issues that could compromise question validity and reliability (Antony et al., 2019). Our pilot survey explored chance event experiences with four open-ended questions: (1) What are your career intentions and why? (2) What unplanned or unpredictable events have occurred and impacted your career intentions? (3) Can you describe an unplanned or unpredictable event that influenced your career intention? (4) Is there anything else you would like us to know about unplanned or unpredictable events? Over 4 weeks, 25 students started the survey, and 14 completed it. We found that the survey took approximately 10 to 15 min to complete. Many graduate students were able to describe chance events that happened to them, but there were students who misinterpreted some of the questions, and often, extraneous information was provided that did not answer our research intentions.

Based on this pilot survey, we decided to use close-ended questions to focus and expedite study responses. For example, we used a defined list of career intentions specific to science careers (see survey description below). We also decided to use a list of types of chance events as prompts for student descriptions of unplanned and unpredictable events that happened to them. Finally, we decided to ask questions about perception of valence and impact of chance events, as informed by the work of Bright et al., (2005, 2009), to capture more specific outcomes of chance events.

The new survey underwent content validation through collaboration with four domain experts familiar with survey design. These individuals provided feedback on question clarity and validity to identify any potential problems with the survey instrument (Ikart, 2019; Olson, 2010).

Survey Description

The final survey consisted of 11 items about the following topics: career intentions, chance events experienced during graduate school, impact of chance events, perceive valence of chance events generally, students’ experience with chance events, and demographics (Table 1).

To answer the first research question, participants could select from a list of 12 chance event options (Table 2; Rice, 2014) to indicate types of events that had occurred in graduate school. Rice developed this list as a modification of Betsworth and Hansen’s (1996) work on chance events in adults associated with a midwestern university (i.e., undergraduate alumni and faculty).

To address our second research question, participants selected their current and initial career intentions from a list of science career options. They then selected the impact level of each chance event on their career intentions (i.e., high impact, limited impact, and no impact). As informed by the work of Bright et al., (2005, 2009), participants also identified how they felt overall about the impacts of those chance events on their career intentions, using several emotional valence categories. Valence—in the context of this study—refers to the positive (i.e., favorable), negative (i.e., unfavorable), neutral, or mixture of positive and negative perceptions about the impact the event had on the graduate student’s career intention.

Finally, to investigate research question three, participants responded to an open-ended question asking them to recall and describe a single chance event that was most impactful on their career intentions.

The following demographic information was collected: year in graduate program, type of graduate assistantship, age range, ethnicity, and gender identity. For questions relating to ethnicity and gender, participants had the option not to disclose this information.

Survey Recruitment

Departmental administrators from four life science-affiliated departments at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, received IRB-approved recruitment emails. These administrators were asked to distribute the survey and associated email verbiage to their graduate student listservs. If all administrators sent the emails, the potential sample population would be approximately 450 graduate students. The departmental administrators for life science programs were asked to send the survey three times between November 15, 2021, and February 10, 2022. As per our IRB, participants had to be 18 years or older and currently enrolled in a life science graduate program to participate in the survey; incentives were not offered for completion.

Data Analysis

There were 69 initial responses to the survey. After removing incomplete responses, or those who did not consent, the final sample size was 39 participants. Each participant received a participant identifier based on color (i.e., blue, red, purple).

Research Question 1: Do Life Science Graduate Students Experience Chance Events, and if so, What Types of Chance Events Are Most Common?

For research question one, we compiled the percentage of respondents who indicated that chance events had occurred to them, the number of chance events selected by each respondent, and the number and frequency of chance event types that were selected by the respondent pool.

Research Question 2 : What Is the Relationship Between Impact Level and Valence of Chance Events on Participants’ Career Intentions?

To answer research question two, we created categories for career changes across the respondent pool. We did this in two ways: career changes overall and academic career changes.

For career changes overall, participants’ original and current career intention changes were sorted into three categories: complete career shift, slight career shift, and no career shift. A complete career shift occurred when participants selected completely different careers as their initial and current career intentions. A slight career shift involved either adding new career intentions or removing some of the initial intentions from their current choices. No career shift was defined as having the same career intention(s) checked for both initial and current career responses.

We created academic career change categories because the literature on graduate student career changes often focuses on shifts of graduate students into and out of academic careers To do this, we used the original and current career responses to create four categories: those who maintained the intention to have a career in academia, those who became interested in an academic career, those who lost interest in an academic career, and those who were never interested in a career in academia.

We then looked at the relationship between these career changes and respondents’ perceptions of the impact of the chance events and the valence of the chance events they had experienced. Impacts were compiled by separating the respondents into each career change category and then calculating the percent impact (high, slight, or no impact) for each chance event among those respondents. Overall impact (high, slight, or no impact) was then averaged across chance events in each career shift category. Valence (not applicable, neutral, mix of positive and negative, and positive) was compiled by separating respondents into each career change category and then calculating the percentage who indicated each type of valence for the chance events they had experienced. We then created stacked bar graphs to show the relationships between impact and valence and career change categories.

Research Question 3: How Do Participants Describe the Impacts of Chance Events on Their Career Intentions?

To answer research question three, we utilized inductive coding to examine the responses to the open-ended question asking respondents (n = 30) to describe an impactful chance event. Inductive coding is useful when researchers do not have existing coding schemes and must create categories—or rather codes—from participant responses (Miles et al., 2020). The first author, H.F., independently reviewed the participant responses, took detailed notes, and organized the information into overarching ideas. H.F. created an initial coding rubric with the codes and definitions for each. H.F. and a secondary coder (see acknowledgments) further refined these initial codes until a final codebook was agreed upon. This codebook consisted of four codes (Table 3). Using the final codebook, H.F. and E.S. coded the participant responses individually. Each response functioned as one coding unit, with multiple codes assigned to each response as needed to represent the ideas expressed. H.F. and E.S. then compared and discussed all codes assigned, reached a final consensus, and clarified all codebook descriptions.

Results

Participants

The majority of the sample (N = 39) was female (69%), white (82%), and between the ages of 25–34 (69%) (Table 4). The largest proportion of participants, (26%), was in year four of their graduate program, although respondents from years 1 through 3 were also well represented. Participants were either funded through a teaching assistant (36%) or research assistant (36%), while the remaining 28% had other sources of funding. Specifically, these students were both research and teaching assistants (5%), on a fellowship (5%), were unfunded and worked part-time to support their graduate education (11%) or did not explain funding (5%).

Research Question 1: Do Life Science Graduate Students Experience Chance Events, and if so, What Types of Chance Events Are Most Common?

Of the 39 participants, 36 (n = 92%) selected at least one of the chance event types as having occurred in graduate school. Three participants (n = 8%) reported not experiencing chance events. Four participants selected the “other” category to describe a unique chance event not covered by the existing types. For example, one participant described a PI changing universities unexpectedly, while another identified unexpected job rejections. Although these chance events could likely have been placed in one of the existing chance event types, the researchers preserved the participants’ responses as they appeared in the data. Participants selected an average of 3.4 chance event types each, with a range of zero to nine chance event types being selected. Responses for each participant can be found in Online Resources 1 and 2.

Graduate student participants selected the chance event type “professional or personal” encounters—such as meeting a seminar speaker—most often (selected by 23 participants or 59% of the sample), followed by the unintended exposure to new work and right place-right time (n = 21; 54%). The three least common chance event types selected included unexpected financial problems (n = 9; 23%), unexpected job openings (n = 11; 28%), and obstacles in career path (n = 13; 33%) (Fig. 2).

Research Question 2: What Is the Relationship Between Impact Level and Valence of Chance Events on Participants’ Career Intentions?

We found that 26% of participants had a complete career shift, 44% had a slight career shift, and 33% had no change in their career intentions. For the slight shifts, 36% became more open to different career paths and 8% narrowed their focus (Online Resource 1). Examples of complete shifts include moving from an initial intention to pursue a career in bench science for the government, followed by a loss of interest in that path, to currently being more interested in science education for the general public. An example of slight shifts included becoming more interested in policy-related careers while maintaining interest in becoming a PI or losing interest in government positions while maintaining interest in becoming a PI.

We found that 50% of the participants maintained an interest in a career in academia over time, 14% switched their career intention away from academia since starting graduate school, 11% became interested in a career in academia, and 25% maintained an intention to have a career outside of academia (Online Resource 2).

Below, and in the Online Resources, we examine whether these career shifts were related to self-reported chance event impact or perceived valence.

Perception of Level of Impact

Overall, respondents indicated two types of chance events that consistently had higher impacts on their careers: professional or personal encounters (65% said high impact and 35% said limited impact) and right place-right time (67% said high impact and 33% said limited impact) (Online Resource 3). The remaining chance event types all had impacts but were not as consistently high in perceived impact. Of the respondents who experienced a chance event, 85% (n = 33) indicated at least one event had a high impact on their career intentions.

Figure 3 depicts the level of impact (High, Limited, or No impact) in relation to shifts in career categories (e.g., No shift, Slight shift, and Complete shift). Overall, those who indicated no impact of the chance events seemed less likely to have a career shift. Those who indicated a high impact of the chance event seemed to become interested in academia (Online Resource 4).

Relationship between the impact level of chance events and overall career shifts. Each bar represents the average impact level of chance events on the respondents, categorized by No impact, Limited impact, and High impact. The x-axis displays the percentage of respondents in each career shift category for the associated impact. The blue color represents “No shift,” orange represents “Slight shift,” and gray represents “Complete shift” in career intentions

Perception of Valence

Approximately half of the participants (49%) perceived chance events as both positive and negative, followed by 41% noting that their experience with chance events had only been positive. The remaining 10% of participants perceived chance events as neutral. Interestingly, no participants perceived their experiences with chance events as solely negative.

Figure 4 and Online Resource 5 shows how the perceived valence of chance events (positive, positive and negative, or neutral) were related to career shifts. Those who said chance events were neutral never shifted their career intentions. Those more positive about the chance event, as compared to having a mix of positive and negative perceptions, had a higher percent of individuals with a complete career shift and more who lost an interest in academia (Online Resources 4 and 5).

Relationship between the perceived valence of chance events and overall career shifts. Each bar represents the category of valence across the respondent pool: “Positive, Negative, Neutral, Mix of positive and negative, and Not applicable.” The x-axis displays the percentage of respondents in each career shift category for the associated valence. The blue color represents “No shift,” orange represents “Slight shifts,” and gray represents “Complete shifts” in career intentions

Research Question 3: How Do Participants Describe the Impacts of Chance Events on Their Career Intentions?

Of the 39 participants, 77% wrote reflections about a chance event that had highly impacted their career. During analysis, we identified four codes: (1) challenges, (2) insights, (3) evaluations, and (4) opportunities (Table 3). The “challenges” code was identified when participants described barriers or obstacles that the participant had to navigate. This code reflects the participants’ discussion about how the event affected them directly, although it did not address the research question. The code of “insight” encompasses participant reflections on learning something new, whether that be requirements for careers, about themselves, or even gaining new perspectives. The code of “evaluation” emerged when the participants described reasons for their choices or thought processes in relation to career changes. Participants, for example, talked about the chance event’s alignment with their interests or reflections on work-life balance. The “opportunity” code represented instances when the chance event resulted in a concrete event such as an internship or job.

Challenges

The “challenges’’ code describes the perception that the chance event presented barriers or obstacles to an individual’s personal well-being or work. This code was identified in 27% of the participant responses. It occurred most often when participants shared their unexpected experiences with a historical event such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Often, the responses could be broken into two types of challenges experienced by the graduate students: challenges to research or personal lives or challenges to an individual’s mental health. Responses that described challenges to research or personal lives referred to situations that presented personal and professional trials. These challenges encompassed factors such as their perceived ability, significance of their research, or execution of research methods. These situations required individuals to navigate obstacles to move forward. For example, Fuchsia talked about how the pandemic had created:

shortages of supplies making research far more difficult and strenuous. The length of time to complete my degree has been increased due to the pandemic

Navigating these obstacles increased challenges to mental health for some participants. Thus, some participants talked about how an event impacted their emotional state and well-being, ultimately influencing how they handled the events. For example, Pink wrote about the chance event of the pandemic, saying:

Increase in anxiety and pressure to succeed as if everything is normal, partner was laid-off from their job, isolation from family and friends, and lack of funding all contributing negatively to mental health and reducing motivation for this degree and career path.

Insights

The “insight” code typically occurred with professional or personal encounter chance events. It was identified in 37% of participant responses and describes moments where the individual learned something new or gained new perspectives. Participants highlighted gaining insights from concrete opportunities (i.e., a position becoming open), talking with others, or even observing others. Responses ranged from seemingly positive to negative insights on careers. Each of these responses in insight appeared to influence either a stabilization in a career intention or a shift away from the initial intention. In many cases, graduate student responses identified new insights into their careers that were seen as positive. For example, Jade described an instance where an unexpected job opening promoted discovery and supported their initial career intention. Jade explained that impact by saying:

With each exposure to another facet of academia,…I find new things to love

Other written responses acknowledged how talking with others—whether it be with peers, PIs, conference speakers, or seminar speakers—led to insights into careers or their degree. For example, Red wrote about how those interactions helped them to see that:

master’s degree holders in my field make comparable money to PhD holders, but have more stable work conditions and short-term goals

In some cases, conversations with others led to a reinforcement in career intentions. For example, Olive wrote about talking with a seminar speaker about their job in research:

sounded exactly like what I dreamed of doing

Graduate students also identified insights in response to chance events when observing others within their fields. In some responses, these insights identified new understandings of careers or degrees that may have influenced a shift away from their intended career or degree. For example, Red wrote about conversations with others about getting stuck in academic postdocs:

has made me realize that I might really enjoy teaching

Evaluations

Forty percent of the participants wrote about how chance events, such as historical events, exposure to new work, and influences of friends and family, created moments of reflection. Often, it was a moment when they assessed career alignment to their goals. In many instances, responses revealed that graduate students evaluated the importance of their work. For example, Yellow wrote about how a chance event had made them think more about their career options, saying:

I briefly considered pursuing a dual MD/PhD in order to be a research physician but ended up continuing on my current path.

In other cases of evaluations—perhaps in identifying the alignment between their interests and career requirements—individuals reflected on the balance of their work and personal lives. This was often described by participants who were attempting to balance the demands of careers or research and align them with their wants or interests for their personal lives. For example, Beige talked about how their experiences with the pandemic had made them realize that:

I would rather have a stable, financially and personally rewarding career where I can be close to friends and family rather than a research-driven career that is highly competitive

Opportunities

The “opportunities” code describes a concrete outcome—such as an internship or acceptance into a program—that resulted from a chance event and was seen in 17% of the written responses from graduate students. This code arose less frequently but was found across multiple chance event types, such as professional and personal encounters and historical events. Individuals often wrote about the option to act on an opportunity in response to a chance event and frequently pursued the opportunity. For example, Tan talked about a chance email from a friend with a job opportunity:

I wound up applying, getting an internship, and will be returning to that company following my graduation.

In some cases, participants talked about how the chance event was significant to them when shaping their career trajectories. Specifically, individuals noted that the events and subsequent opportunities broadened their career or educational goals. For example, Mauve explained how a chance encounter had opened a door:

without this opportunity I wouldn’t have entered grad school and may have even given up on going.

Across graduate student responses, unexpected or unplanned events motivated participants toward new careers they were not originally interested in or influenced a reinforcement of career intentions or degree. Similar types of chance events did not appear to have the same outcome among the graduate student participants. For example, some participants who had a professional or personal encounter had a shift away from their initial career intention while others did not.

Discussion

This study investigated the occurrence and impact of chance events on the career intentions among a sample of graduate students in the life sciences at one research-intensive university. Previous research identified chance events as significant factors influencing careers in various populations (Bright & Pryor, 2009; Duffy et al., 2013; Hirschi & Valero, 2017; Kindsiko & Baruch, 2019; Rojewski, 1999; Williams et al., 1998), but not graduate students. The findings of this study, reflecting participant perceptions and experiences, supported that chance events are common and are perceived as impacting graduate student career intentions. In such a small study, making definitive statements about patterns is difficult, but we noted that those who reported no impact or neutral impact of chance events were less likely to indicate a change in their career intentions, and high impact and positive affect seemed to have more shifts. Participant reflections on the events highlighted the importance of chance events as potential positive opportunities for growth in graduate professional development. Therefore, there is a need to further explore the transformative impacts these unexpected events can have on career development among graduate students, with a particular focus on how the events are processed emotionally and cognitively.

These results can be used to inform the application of the Planned Happenstance Learning Theory to graduate student careers. PHLT does not consider reflection as a component in processing chance events; our findings show that graduate students used chance events as moments of deep reflection to carefully consider their careers. Yet, not all graduate students reacted similarly, supporting the importance of individual perceptions, emotional responses, and contextual factors in graduate student responses to chance events. This suggests the need to incorporate individual differences in the emotional and cognitive processing of chance events in the PHLT. We also acknowledge, however, that because our study was done during the pandemic, we may have uncovered more emotional processing to this particular chance event and its cascading impacts than would be typical for chance events during less extraordinary times.

Finding 1: All Chance Event Types Influenced the Experiences of the Graduate Student Participants, Highlighting the Need for Comprehensive Support

Life science graduate students experienced many chance events while in their graduate programs. In fact, 92% of participants indicated experiencing at least one chance event with 82% experiencing multiple chance events while in their program. Although some chance event types were more prevalent, all were experienced by a significant proportion of the participants. This suggests that, methodologically, the types of chance events identified by Rice (2014) may serve as a good starting point for additional research on chance events and graduate students. It also suggests broadly that chance events are a significant factor in the experience of graduate students and that they are not confined to any particular subset of chance event types.

Similar to Betsworth and Hansen (1996) study on older adults, our respondent populations’ most common chance events were professional or personal encounters and right place-right time. This may be due to a primary focus of graduate education entailing learning about research, increasing skills, and building networks to help them advance in their careers, often through attending seminars and conferences and talking with other researchers. In contrast to Betsworth and Hansen (1996) study, however, many in the current study selected “influence of historical events” more frequently than other chance event types. This is likely due to the fact that the survey was administered during the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic resulted in research lab shutdowns, social distancing measures, and heightened anxiety for many—if not all—people. In many ways, it was surprising that this chance event was not the top selection among the respondents, suggesting the resilience of graduate students even in the midst of the pandemic.

The findings from this study highlight that chance events are not solely confined to the professional realm. Many graduate students selected personal chance events such as “Influence of family and friends” and—while less frequently—unexpected financial problems. This is supported by research conducted by Scott and Hatalla (1990), who examined the role of chance and contingency factors in the careers of college-educated women. They found that over 60% of participants’ careers were significantly impacted by “unexpected personal events.” This characteristic of chance events interacting with both personal and professional aspects of someone’s life is supported by PHLT because it emphasizes the importance of developing skills like curiosity, risk-taking, persistence, flexibility, and optimism (Krumboltz, 2009) regardless of whether the event is personal or professional. This highlights the need to provide both personal and professional support to graduate students to empower them to grow in all areas of their lives.

Finding 2: Chance Events Had High and Mostly Positive Impacts on Career Intentions

We found evidence that impact level of chance events differed across career shifts, but those patterns need to be explored in larger samples. First, our findings suggest a potential association between the perceived impact of chance events and shifts in career intentions. Specifically, participants who indicated that the events had limited or high impacts were more likely to experience a shift in their career intentions compared to those who did not experience a shift. It is interesting that graduate students in this study thought many types of chance events were highly impactful on their career intentions. It should be noted, however, that some participants experienced shifts in career intentions when chance events were perceived as having no impact, highlighting a non-linear relationship between chance events and career decision-making. We suggest that chance events may prompt deeper contemplation about career paths, potentially influencing decisions over longer periods than our study captured. While our empirical data may not definitively support previous literature on chance events impacting career trajectories (Bright & Pryor, 2009; Bright et al., 2005; Hirschi, 2010; Kindsiko & Baruch, 2019; Salomone & Slaney, 1981; Williams et al., 1998), the perceptions of graduate students about the value of chance events on their careers were affirmed here.

Our findings revealed a higher perceived impact of chance events on graduate student career paths when compared to previous research. While Kindsiko and Baruch’s (2019) study—which focused on PhD holders in academia—noted that chance events impacted 30% of the participants’ careers, our findings indicated a higher prevalence among graduate students. This finding may suggest that the transitional phase of graduate education may be particularly susceptible to the influence of chance events on career trajectories which is in line with the PHLT and supports work suggesting the unique positionality of graduate students (Reid and Gadner, 2020). It should be noted, however, that unlike Kindsiko and Baruch (2019), we explicitly asked students about the occurrence and perceptions of chance events, which may have bolstered reported experiences with chance events.

A significant finding was the emotional valence graduate students expressed about the impact these events had on their careers. Specifically, graduate students in our study did not view the overall impact of chance events on their careers as solely negative. In fact, we found that graduate students viewed these events as having a mixture of positive and negative impacts on their careers, or sometimes, solely positive, regardless of any shifts in career intentions. This supports previous findings by Bright and Pryor (2009). It is possible that graduate student respondents did not view the overall impact of chance events as solely negative due to the retrospective nature of the survey. It is possible that immediate reactions to chance events may have been negative, but with time, the impact may have become more positive. This is an interesting finding because of the current deficit-framing of shifts in graduate careers (Alberts et al., 2014; Hardré et al., 2019; Roach & Sauermann, 2017; Sauermann, 2005) and lends support to the idea that there may be positive factors that underlie career shifts as well.

Finding 3: Participant Reflections About Chance Events Suggested the Importance of Processing and Interpreting the Experience in Relation to Their Personal Goals

According to the Planned Happenstance Learning Theory (PHLT), individuals who possess specific skills—curiosity, persistence, flexibility, optimism, and risk-taking—are inclined to perceive chance as opportunities for growth. Our analysis of graduate student written responses revealed an optimistic mindset, demonstrating willingness to interact with chance events without direct prompting. For example, the code of opportunity shows that participants embraced the uncertainty and looked to capitalize on the event. Additionally, those who described their chance events as moments for insight showed curiosity in gaining valuable knowledge and understanding from their experiences. Thus, a more in-depth analysis of graduate student experiences with chance events may find that many students are leveraging skills defined by PHLT.

Interestingly, the types of responses seen in the graduate students demonstrated a reflective aspect aligned with the appraisal and re-appraisal processes outlined by Lazarus’ (1974) Cognitive Appraisal Theory. Appraisal theory posits that individual responses to challenging situations are determined by the evaluation of the relevance and significance of the event, coping strategies and resources available, as well as the potential outcomes that may occur (Lazarus, 1974, 2001; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984, pp. 32). In response to chance events, we suggest that graduate students in this study engaged in a two-stage appraisal process, with the students appraising the initial impact of the events in terms of their alignment—or misalignment—with their goals, values, and overall well-being. This initial appraisal may serve as the basis for the first interpretation and reaction but then can go through iterative second rounds of appraisals that can shift perceptions over time. This may explain the combination of positive and negative overall impacts, but the lack of solely negative perceptions, many participants expressed about chance events.

These findings may further emphasize the importance of determining chance event alignment or misalignment with the individual’s goals and values. For example, if the event did align with their goals, values, or well-being, it was often viewed as an “opportunity” or an “insight” that helped graduate students’ career development. Conversely, if the event went against their current goals or interests, the participants typically saw the events as “challenges” to overcome or as providing moments for “evaluations” to consider what they wanted for their careers or research. However, this misalignment did not mean that the participants saw the events ultimately as negative; often, they appreciated the insight and thought it positively influenced their career, despite even an initial negative perception.

Overall, these results suggest that chance events were highly personal, but beneficial in helping graduate student participants decide what they wanted in their careers. It may be possible that without these events, graduate students in this study may not have reflected on their current paths and realized the potential need to adjust their path for their own well-being. Thus, studies should acknowledge the positive and perhaps necessary role that chance events may have on professional growth and well-being of graduate students.

Limitations and Future Work

The results of this study are based on a small sample size and participants limited to one university. However, this limited scope was intentional to provide an initial exploration into chance events and their effects on the career intentions of graduate students. Further investigations at other institutions are needed to examine whether the types of chance events and their impacts are similar or different in other contexts. The small sample made it difficult to disaggregate the results by demographic characteristics such as race/ethnicity, gender identity, employment status, or age in a meaningful way. This is potentially important as different demographic groups may acknowledge or perceive the impacts of chance events differently given the intrinsic and extrinsic factors posited in PHLT. For example, despite common factors influencing master’s and Ph.D. students’ careers, these groups do have differences related to expectations and life situations (Hardré et al., 2019). Future work could employ a national survey to obtain a larger sample size to identify more generalizable patterns among graduate students.

The survey had participants recall chance events that occurred during their graduate programs. There may have been recall bias, where only impactful chance events were recalled, and non-impactful events were not recalled. Ultimately, this would bias the results toward the recollection of chance events that impacted career intentions. However, the study captured the experiences currently impacting the way these students think about their career intentions, which is critically important. In fact, our study suggests that chance events caused some individuals to pause and re-evaluate their careers. However, our methods were not designed to specifically probe or answer the extent to which re-appraisals were occurring or the extent to which these events impacted student well-being. Future work should investigate how an individual processes chance events initially and over time to better understand what support graduate students need to navigate these unexpected occurrences. Utilizing interviews, for example, would be a beneficial next step to investigate how a graduate student appraises chance events.

Conclusion

Our study provided evidence that graduate students, faculty, and those administering graduate programs should attend to the unplanned or unpredictable events that occur during graduate school because of their potential impact on the career development of graduate students. As graduate students navigate teaching, research, and other aspects of graduate school, unexpected events will occur, and graduate students need the knowledge and skills to process those events cognitively and emotionally. Given their potential to foster reflection and positive outcomes, and with appropriate framing, it may be that chance events could be an unexpected tool to support mental well-being in graduate students.

Data Availability

The data set generated and analyzed for this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Alberts, B., Kirschner, M. W., Tilghman, S., & Varmus, H. (2014). Rescuing US biomedical research from its systemic flaws. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(16), 5773–5777. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1404402111

Alcock, S. (2010). The stratigraphy of serendipity. In M. de Rond & L. Morley (Eds.), Serendipity: Fortune and the prepared mind (pp. 11–25). Cambridge University Press.

Antony, J., Lizarelli, F. L., Fernandes, M. M., Dempsey, M., Brennan, A., & McFarlane, J. (2019). A study into the reasons for process improvement project failures: Results from a pilot survey. International Journal of Quality and Reliability Management, 36(10), 1699–1720. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQRM-03-2019-0093

Austin, A. E., & McDaniels, M. (2006). Preparing the professoriate of the future: Graduate student socialization for faculty roles. In J.C. Smart (Ed.), Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research, 21. (pp. 397- 456). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-4512-3_8

Beiter, R., Nash, R., McCrady, M., Rhoades, D., Linscomb, M., Clarahan, M., & Sammut, S. (2015). The prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and stress in a sample of college students. Journal of Affective Disorders, 173, 90–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.054

Betsworth, D. G., & Hansen, J. I. C. (1996). The categorization of serendipitous career development events. Journal of Career Assessment, 4(1), 91–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/106907279600400106

Bingham, A. J. (2023). From data management to actionable findings: A five-phase process of qualitative data analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 22, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069231183620

Bright, J. E. H., & Pryor, R. G. L. (2009). Chance events in career development: Influence, control and multiplicity. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 75(1), 14–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2009.02.007

Bright, J. E. H., Pryor, R. G. L., & Harpham, L. (2005). The role of chance events in career decision making. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 66(3), 561–576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2004.05.001

Bright, J. E. H., Pryor, R. G. L., Chan, E. W. M., & Rijanto, J. (2009). Chance events in career development: Influence, control and multiplicity. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 75(1), 14–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2009.02.007

Byars-Winston, A. (2014). Toward a framework for multicultural STEM-focused career interventions. The Career Development Quarterly, 62(4), 340–357. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.2014.00087.x

Cabral, A. C., & Salomone, P. R. (1990). Chance and careers: Normative versus contextual development. The Career Development Quarterly, 39(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.1990.tb00230.x

Cabrera, A. F., Colbeck, C. L., & Terenzini, P. T. (2001). Developing performance indicators for assessing classroom teaching practices and student learning. Research in Higher Education, 42(3), 327–352. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018874023323

Deer, L. K., Gohn, K., & Kanaya, T. (2018). Anxiety and self-efficacy as sequential mediators in US college students’ career preparation. Education and Training, 60(2), 185–197. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-07-2017-0096

Duffy, R. D., Torrey, C. L., Bott, E. M., Allan, B. A., & Schlosser, L. Z. (2013). Time management, passion, and collaboration. The Counseling Psychologist, 41(6), 881–917. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000012457994

Eissenstat, S. J., & Nadermann, K. (2018). Examining the use of planned happenstance with students of Korean cultural backgrounds in the United States. Journal of Career Development, 46(4), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845318763955

Fuhrmann, C. N., Halme, D. G., O’Sullivan, P. S., & Lindstaedt, B. (2011). Improving graduate education to support a branching career pipeline: Recommendations based on a survey of doctoral students in the basic biomedical sciences. CBE-Cell Biology Education, 10(3), 239–249. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.11-02-0013

Gemme, B., & Gingras, Y. (2012). Academic careers for graduate students: A strong attractor in a changed environment. Higher Education, 63, 667–683. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-011-9466-3

Hallingberg, B., Turley, R., Segrott, J., Wight, D., Craig, P., Moore, L., Murphy, S., Robling, M., Simpson, S. A., & Moore, G. (2018). Exploratory studies to decide whether and how to proceed with full-scale evaluations of public health interventions: a systematic review of guidance. Pilot and Feasibility Studies, 4 (104). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-018-0290-8

Hardré, P. L., Liao, L., Dorri, Y., & Beeson Stoesz, M. A. (2019). Modeling American graduate students’ perceptions predicting dropout intentions. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 14, 105–132. https://doi.org/10.28945/4161

Hirschi, A. (2010). The role of chance events in the school-to-work transition: The Influence of demographic, personality and career development variables. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77(1), 39–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2010.02.002

Hirschi, A., & Valero, D. (2017). Chance events and career decidedness: Latent profiles in relation to work motivation. The Career Development Quarterly, 65(1), 2–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12076

Ikart, E. M., (2019). Survey questionnaire survey pretesting method: An evaluation of survey questionnaire via expert reviews technique. Asian Journal of Social Science Studies, 4(2). https://doi.org/10.20849/ajsss.v4i2.565

Kindsiko, E., & Baruch, Y. (2019). Careers of PhD graduates: The role of chance events and how to manage them. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 112, 122–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2019.01.010

Krumboltz, J. D. (1996). A learning theory of career counseling. In M. L. Savickas & W. B. Walsh (Eds.), Handbook of career counseling theory and practice (pp. 55–80). Davies-Black Publishing.

Krumboltz, J. D. (2009). The happenstance learning theory. Journal of Career Assessment, 17(2), 135–154. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072708328861

Krumboltz, J. D., Mitchell, A. M., & Jones, G. B. (1976). A social learning theory of career selection. The Counseling Psychologist, 6, 71–81.

Krumboltz, J. D., Foley, P. F., & Cotter, E. W. (2013). Applying the happenstance learning theory to involuntary career transitions. The Career Development Quarterly, 61(1), 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.2013.00032.x

Lazarus, R. S. (1974). Psychological stress and coping in adaptation and illness. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 5(4), 321–333. https://doi.org/10.2190/t43t-84p3-qdur-7rtp

Lazarus, R. S. (2001). Relational meaning and discrete emotions. In K. R. Scherer, A. Schorr, & T. Johnstone (Eds.), Appraisal Processes in Emotion: Theory, Methods, Research (pp. 37–67). Oxford University Press.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer.

McCulloch, A. (2021). Serendipity in doctoral education: The importance of chance and the prepared mind in the PhD. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 46(2), 258–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877x

Miles, M. B., Huberman, M. A., & Saldaña, J. (2020). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook. SAGE Publications.

Mitchell, K. E., Al Levin, S., & Krumboltz, J. D. (1999). Planned happenstance: Constructing unexpected career opportunities. Journal of Counseling and Development, 77(2), 115–124. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1999.tb02431.x

Olson, K. (2010). An examination of questionnaire evaluation by expert reviewers. Field Methods. Sage Journals, 22(4), 295–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/155822X10379795

Reid, J., & Gardner, G. E. (2020). Navigating tensions of research and teaching: Biology graduate students’ perceptions of the research-teaching nexus within ecological contexts. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 19(3), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.19-11-0218

Rice, A. (2014). Incorporation of chance into career development theory and research. Journal of Career Development, 41(5), 445–463. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845313507750

Roach, M., & Sauermann, H. (2017). The declining interest in an academic career. PLoS One, 12(9), e0184130. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0184130

Rojewski, J. W. (1999). The role of chance in the career development of individuals with learning disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly, 22(4), 267. https://doi.org/10.2307/1511261

Roseman, I. J. (2001). A model of appraisal in the emotion system: Integrating theory, research, and applications. In K. R. Scherer, A. Schorr, & T. Johnstone (Eds.), Appraisal Processes in Emotion: Theory, Methods, Research (pp. 68–91). Oxford University Press.

Salomone, P. R., & Slaney, R. B. (1981). The influence of chance and contingency factors on the vocational choice process of nonprofessional workers. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 19(1), 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-8791(81)90046-4

Sauermann, H. (2005). Vocational choice: A decision making perspective. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 66(2), 273–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2004.10.001

Sauermann, H., & Roach, M. (2012). Science PhD career preferences: Levels, changes, and advisor encouragement. PLoS One, 7(5), e36307. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.003630

Scott, J., & Hatalla, J. (1990). The influence of chance and contingency factors on career patterns of college-educated women. The Career Development Quarterly, 39(1), 18–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.1990.tb00231.x

Sherman, D. K., Ortosky, L., Leong, S., Kello, C., & Hegarty, M. (2021). The changing career landscape of doctoral education in science, technology, engineering and mathematics: PhD students, faculty advisors and preferences for varied career options. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.711615

Shmatko, N., Katchanov, Y., & Volkova, G. (2020). The value of PhD in the changing world of work: Traditional and alternative research careers. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 152 (119907). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2019.11990

St. Clair, R., Hutto, T., MacBeth, C., Newstetter, W., McCarty, N. A., & Melkers, J. (2017). The “new normal”: Adapting doctoral trainee career preparation for broad career paths in science. PLoS One, 12(5), e0177035. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177035

Sue, V. M., & Ritter, L. A. (2007). Conducting online surveys. SAGE Publications, Inc., https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412983754

Valickas, A., Raišienė, A. G., & Rapuano, V. (2019). Planned happenstance skills as personal resources for students’ psychological wellbeing and academic adjustment. Sustainability, 11(12). https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123401

Williams, E. N., Soeprapto, E., Like, K., Touradji, P., Hess, S., & Hill, C. E. (1998). Perceptions of serendipity: Career paths of prominent academic women in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 45(4), 379–389. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.45.4.379

Winstone, N., & Moore, D. (2017). Sometimes fish, sometimes fowl? Liminality, identity work and identity malleability in graduate teaching assistants. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 54(5), 494–502. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2016.1194769

Wood, C.V., Jones, R.F., Remich, R.G., Caliendo, A.E., Langford, N.C., Keller, J.L., Cambell, P.B., & McGee, R. (2020) The National Longitudinal Study of Young Life Scientists: Career differentiation among a diverse group of biomedical PhD students. PLoS One, 15(6). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234259

Zimmerman, A. M. (2018). Navigating the path to a biomedical science career. PLoS One, 13(9), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0203783

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the participants in this study, as well as the reviewers and editor who provided excellent suggestions to improve the manuscript. We would also like to thank Morgan Smith for her assistance in coding, which significantly contributed to our data analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ferguson, H., Schussler, E.E. Examining the Unexpected: The Occurrence and Impact of Chance Events on Life Science Graduate Students’ Career Intentions. Journal for STEM Educ Res (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41979-024-00122-3

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41979-024-00122-3