Abstract

Research Question

Can requiring police to wear body-worn cameras (BWC) on duty restrain police misconduct in contexts such as a favela in Rio de Janeiro, where police use militaristic and highly aggressive tactics?

Data

We collected quantitative and qualitative data on a wide range of behaviors, including police wearing BWC, turning on the BWC for recording citizen contacts, use of force by and against police officers, stop and search, responding to citizen requests for police assistance, and police supervisors wearing BWC. A total of 857 different police officers were tracked during the 1-year study, with a mean of 470 officers each month participating in the test of BWC across 52,000 officer shifts.

Methods

BWC status was randomly assigned by shifts to all officers in the shift, within five different kinds of police units. Analyses focused on intent-to-treat effects, with high compliance of wearing BWC but less than half of measured encounters recorded. Regression analyses provided estimates of different effects for officers who had previously been injured or had injured civilians.

Findings

Camera assignment, regardless of whether police turned cameras on, reduced stop-and-searches and other forms of potentially aggressive interactions with civilians. Cameras also produced a strong de-policing effect: police wearing cameras were significantly less likely to engage in any activity, including responding to calls and dispatch and street requests for help. These changes in police behavior occurred even when in 50% of the registered interactions with civilians, officers disobeyed the protocol that required them to turn their cameras on. Yet when officers’ supervisors wore cameras, policing activities and camera usage increased. Police surveys, interviews, and focus groups strengthen the findings.

Conclusion

The potential of BWC to reduce police abuse finds limitations where an organizational culture that perpetuates a lack of compliance with internal protocols and violence persists.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

If you give body cameras to my officers, This will stop them from doing their job.

–Interview with a Police Unit Commander in Rocinha’s UPP

Introduction

Police abusive behavior is a grave problem in many democratic societies worldwide. Police-civilian interactions are characterized by a profound imbalance of power and the ever-present potential to abuse and oppress. Police abuse results from individual, societal, and institutional factors. In recent years, the academic debate in the USA has increasingly concentrated on structural racism and implicit racial biases (Glaser et al., 2014; Knox et al., 2020; Streeter, 2019; Fryer, 2019). Cano (2010) also finds evidence of racial discrimination in the use of force by police in the Brazilian context, where Blacks and “Pardos” (people of mixed race) are the primary victims of officer-involved killings.

Another line of research traces police aggression to societal preferences. In Latin America, fear of crime and “ideology,” as Godoy (2006) has found, generate popular support for police aggression, including the use of lethal force, lynching, and other forms of extra-legal actions that violate human rights. Caldeira (2002) highlights the persistence of strong popular support for strong-hand militarized policing approaches in Brazil and how societal preferences perpetuate an oppressive institution.

Institutional factors play a crucial role in allowing police unlawful behavior and abuse, including how police departments monitor and sanction police aggression and how criminal justice systems fail to punish it (Brinks, 2007; Magaloni & Rodriguez, 2020; Mummolo, 2018; Skolnick & Fyfe, 1993). Police behavior further results from organizational culture and in-group socialization, where aggressive behavior is learned from peers and rewarded by superiors (Westley, 1970). Using a large representative survey (N=5000) of the Military Police of Rio de Janeiro (PMERJ),Footnote 1 Magaloni and Cano (2016) uncovered a “police as warrior mentality” among police officers. They argue that the police-as-warrior behavior is supported by the majority of the urban middle class, who endorse the common phrases “Bandido bom é bandido morto” (a good criminal is a dead criminal) and “Direitos humanos são para humanos” (human rights are for humans).

A related line of research emphasizes agency problems as the main culprit of police misconduct stemming from an incapacity to supervise and sanction frontline officers (Brehm & Gates, 1997). This paper focuses on such agency dilemmas. In recent years, body-worn cameras (BWC) have been one of the most prominent interventions to address agency problems (Ariel et al., 2015, 2016; Lum et al., 2019; McCluskey et al., 2019; Ready & Young, 2015). It is believed that BWC can curb police misconduct through two main mechanisms. First, BWC are likely to increase supervisors’ monitoring capacity, which can increase compliance with protocols and induce more restraint on the part of the police. Second, due to their ability to produce higher quality and more reliable evidence, cameras can increase the probability that police are prosecuted and convicted in courts for unlawful or abusive behavior (Ariel et al., 2015). This deterrence channel may operate both by restraining police officers’ abusive behavior and by reducing aggressive behavior toward the police in their interactions with civilians (Ariel, 2016; Jennings et al., 2015).

In this article, we report the first field experiment on this subject in a high-violence and racially segregated developing world setting: a large favelaFootnote 2 in Brazil, known as Rocinha, with a population of around 120,000 inhabitants. Our experiment was implemented from December 2015 to November 2016. It included the random assignment of cameras to more than 8500 shifts and 470 police officers.

Research Question

A critical question is whether body cameras can restrain police misconduct in contexts such as Rocinha, where despite efforts to demilitarize the police through the introduction of a community-oriented policing approach (called the Pacifying Police Units, or UPPs), police continue to use militaristic and highly aggressive tactics.

Drawing from Black (1980), we focus on cameras’ effect on three forms of police behaviors:

-

i.

Proactive policing, including stop-and-searches and other encounters with civilians.

-

ii.

Reactive policing such as emergency calls and dispatches of officers to those locations, and requests for help by residents in the streets.

-

iii.

Use of deadly force, which we measure with the number of bullets fired.

Data and Methods

In order to answer these questions, we randomly assigned cameras to three types of units:

-

GPPs or foot patrols deployed to fixed geographic areas to carry “proximity” policing functions

-

GTTPs, which are tactical units that often engage in special operations involving armed confrontations with drug traffickers

-

Radio Patrulhas, or patrol units with vehicles

Compliance with Experimental and Standard Protocols

The results of our study are complex and reflect some of the limitations of BWCs when there is ample disobedience to protocols. We found evidence that in around 50% of the registered “occurrences,” called BOPMs for the Portuguese acronym, officers did not record the event. Empirically, we address the extensive non-compliance through intention-to-treat (ITT) models. In most empirical models, the “treatment” is camera assignment, although we also distinguish in some models between cameras that were turned on and that were not.

Overview of Findings

Camera assignment led to a 39% reduction in stop-and-searches and other proactive enforcement activities. The reduction of proactive enforcement activities can be regarded as a positive result in Rocinha where, according to our qualitative interviews with residents, officers often abuse their authority by using unnecessary force (e.g., “slap suspects,” “pull hair,” “hitting,” “physically attacking”) and threatening civilians.

Aggression seems to go both ways. Three rounds of surveys with police officers during our study reveal that a significant number of them are victims of community aggression, including being “cursed,” becoming targets of thrown “water,” “urine,” or “stones,” and suffering “verbal threats” and “physical attacks,” all of which are manifestations of the toxic police-community relationships that persist in Rocinha and many favelas in Rio (Magaloni et al., 2020). These forms of community aggression toward the police declined during our study, suggesting that the deterrence channel induced by the cameras may have operated both ways, restraining police abusive behavior toward residents and aggressive behavior toward the police in their interactions with residents, in line with Ariel (2016) and Jennings et al. (2015).

An unexpected result is that cameras also discouraged police from performing necessary functions. When shifts were assigned a camera, they reduced their actions in response to calls to the operation center and street requests by 43% and 60%, respectively.

Our results raise an important question: why did camera assignment and not its usage produce such a substantial de-policing effect? We argue that two factors explain this intriguing result. First, when officers were assigned a camera, they chose not to engage with civilians because they wanted to evade the obligation to record the interaction. Importantly, when we model the difference between police wearing cameras that were turned on or not, the de-policing effect disappears for shifts that generally turned their cameras on. In other words, officers who engaged in more BOPMs did record these, likely because they knew that the videos would not generate incriminating evidence. Second, interviews and focus groups pointed to an indirect psychological effect where frontline officers believed that in assigning BWCs to Rocinha’s UPP, the PMERJ’s High Command had chosen them for closer scrutiny.

Regarding the use of deadly force, there were only 27 events when police fired their weapons and used 469 bullets. Given the small number of events, we do not have enough statistical power to run OLS regressions. A simple cross-tab suggests that cameras may have dissuaded officers from using firearms. However, these results should be taken cautiously because of the small number of deadly force events.

In terms of the effects of randomly assigning cameras to supervisors, we found that the probability that police engaged in a BOPM increased by 300% when their supervisors wore a camera. Likely, when supervisors wore cameras, they felt more compelled to do a better job of supervising their officers—in this case, enticing them to engage in more policing activity.

Lastly, the paper explores, through OLS regression models, the factors associated with minutes police recorded. The results reveal a troubling phenomenon: officers who appear to be more aggressive, which we infer from the fact that they reported “having injured one or many persons in the past year,” resisted recording their interactions with civilians at a higher rate than officers who had not injured citizens. By contrast, those who turned their cameras on more often report having experienced a high degree of community aggression, which we measure with a composite index of the number of times they reported being victims of vicious behaviors toward them. Another factor associated with more camera usage is the frequency of supervision regarding compliance with the protocol. According to our police surveys, only 30% of the officers reported being supervised in the field for their on-camera usage frequently or very frequently.

In summary, this study uncovers the BWC potential to reduce aggressive interactions with civilians, including stop-and-searches and other proactive encounters. Additionally, cameras appear to have led officers to use less deadly force. However, this study also demonstrates some unsettling results, including a de-policing effect where police stopped performing necessary functions such as responding to calls dispatched from the Operations Center, and to street requests from citizens. Inadequate supervision, our study reveals, can undermine compliance with BWCs’ protocols and attempts to monitor frontline officers. This problem can partly be remedied by assigning cameras to supervisors. The fact that police refused to turn on the BWC limits the effectiveness of this technology because abusive officers could turn their cameras off and not worry about being sanctioned for misbehaving.

Police in Rio de Janeiro

In charge of ostensibly preventive policing, the PMERJFootnote 3 is one of the deadliest police forces in the world. Data on officer-involved killings from the State’s Institute of Public Security (ISP) show that Rio’s police killed at least 19,865 people between 2003 and 2019. Roughly 20% of all registered homicides in that period occurred at the hands of on-duty officers. The PMERJ has justified these killings based on self-defense or “resistance to arrest” (auto de resistência). The criminal justice system practically never investigates or punishes these killings (Brinks, 2007). Since the 1980s, drug trafficking groups began to fill the governance vacuum in the favelas (Dowdney, 2005). In tandem, militias of former police officers, firemen, and prison guards emerged across the city, promising to remove drug gangs and provide security to citizens (Cano & Duarte, 2012).

The Military Police increasingly relied on special operation units such as the Battalion of Special Operations (BOPE), trained in urban warfare, and tactical teams operating inside the territorial battalions, known as GTTPs, to fight a war with drug trafficking factions. The war on drugs has produced exorbitant levels of violence.

Starting in 2008, the Rio government introduced a wide-reaching policing project, the Pacifying Police Units (UPPs) (Lessing, 2015; Willis & Prado, 2014). The goal was to foster a new policing mentality based on notions of “proximity policing.” The first UPP was introduced in December of 2008 and the program gradually expanded to cover 160 favelas with over 10,000 police officers deployed. The expansion of the UPPs halted in 2014. Through a quasi-experimental evaluation, Magaloni et al. (2020) demonstrate that the UPPs reduced officer-involved killings by more than 40%, although in some areas, police lethal violence increased. Officer-involved killings significantly escalated with the economic recession of 2015, which also increased crime.

The PMERJ Organizational Structure

Rio provides a unique social laboratory to gain insight into the bureaucratic and organizational challenges of reforming a large corporation of more than 40,000 police officers. The PMERJ is headed by the High Command, which is in charge of establishing the corporation’s goals and objectives; designing special operations and setting protocols; hiring, training, and promotions; and monitoring and reprimanding officers, among others. There are more than forty Territorial Battalions in charge of policing in their areas, which operationally are organized into Intermediary Commands or Policing Area Commands. There are thirty-nine UPPs, which police over 160 favelas. The UPPs are headed by the General Commander of the UPPs, under the direction of the PMERJ’s High Command. The PMERJ also has many specialized units, including the BOPE, Riot Police (Choche), and tourism (BPtour), among others.

The principal-agency dilemmas entailed in monitoring frontline officers underscored by Brehm and Gates (1997) are exacerbated by the fact that the PMERJ is a large corporation with such a complex organizational structure. Each Territorial Battalion, UPP Unit, and Specialized Battalion is headed by a Unit Commander, who appoints several local supervisors. Although the PMERJ High Command sets policies and protocols and is in charge of sanctioning police misconduct, enforcing protocols and monitoring frontline officers depends on Unit Commanders and their supervisors. This organizational structure complicates agency dilemmas because frontline officers are under the command of multiple principals.Footnote 4

Rocinha: the Context of the Study Site

The study site was chosen by the General Commander of Operations, who is a part of the PMERJ’s High Command. Rocinha is one of the most valuable territories for drug trafficking because of its size and geographic location, near the wealthiest neighborhoods. Rocinha received a UPP in 2012. For a year, the UPP was well received, until the Amarildo scandal in the summer of 2013, when the unit commander and various UPP officers were implicated in the torture and killing of Amarildo de Souza, a bricklayer from the favela. De Souza’s death occurred in a police building with CCTV cameras. The footage showed De Souza entering the police station. The Unit Commander claimed that he had left the police building by a door with a broken camera.Footnote 5 Attempting to salvage the UPP’s legitimacy, the military police detained the UPP Unit Commander and over ten officers. The Amarildo scandal severely damaged the UPP’s legitimacy. Soon after this took place, the police lost control of the local situation, and armed confrontations began to escalate in frequency.

One month before the onset of the study (November 2015), we collected a representative survey (n = 1873) about perceptions of security and the police among Rocinha residents.Footnote 6 Figure 1 reports the percentage of respondents who were victimized by police and by criminal groups. Victimization by police appears to be more prevalent than victimization by criminal groups. In our fieldwork, residents reported that their interactions with police involve behaviors such as being “slapped in the face,” “pulled by the hair,” “frisked with no reason,” “disrespect,” and “aggression.”

Our survey also asked about favela residents’ feelings toward the police. Sixty-one percent reported fear of being killed by the police. Respondents also were given a menu of options equally split between positive and negative words: fear, respect, distrust, admiration, sympathy, indifference, disrespect, rage, or “other.” The most commonly used words were negative and expressed harsh sentiments toward the police: “distrust” (39%), “fear” (38%), and “disrespect” (27%). Only 3% reported “respect” and 5% “admiration.” Fifty-six percent reported feeling disrespected by the police. Not surprisingly, only 10% reported that they would resort to the police if they had a conflict.

Unlike the community survey that could not be collected again due to resource limitations, we collected three rounds of surveys with police officers. The baseline survey was collected in November 2015, and rounds 2 and 3 were collected in June–August and October–November 2016, respectively.Footnote 7 In one question, we asked officers how frequently they were “involved in the following activities during their daily shifts: drugs seizures, drug possession, gun seizures, disturbance of peace, domestic violence, resistance to arrest, bickering, arrests, and vehicle trafficking.” Seizing drugs or weapons, dealing with a resistance to arrest incident, drug possession, or an arrest might result after police stop-and-search a suspect.Footnote 8 Domestic violence incidents and vehicle thefts often result from calls for help to the operation center.

Figure 2 reveals that during our study, there seems to be a systematic decline in both proactive and reactive policing activities (figure on the left) (Black, 1980). Since crime rates did not significantly change during our study, as revealed by reports before the Civil Police in charge of investigations (see the Appendix), the data indicates a de-policing effect produced by the cameras, as we demonstrate below when exploring treatment effects.

Moreover, there is a decline in self-reported use of force (see Fig. 2, on the right). We asked officers if they had participated in an armed conflict, used their firearms, wounded someone, and participated in an event where someone was injured or killed during the last 12 months.Footnote 9 We observe a substantial decline in self-reported use of deadly force during our field experiment. For instance, at baseline, 43% report firing a weapon, and at the end of the study, this declines to less than 9%.

Changes in police behavior might partly be responsible for the substantial reduction in community hostility toward police, which can be seen in Fig. 3. Police said that residents “throw water,” “urine,” and “stones” at them and that they would “curse” and “physically attack” them. The data reveals a significant decline in these forms of aggression during our field experiment. There is suggestive evidence that body cameras might have simultaneously reduced police abuse and aggressive behavior toward the police.

Study Design

We considered five different kinds of police units for randomly assigning entire shifts to wear cameras or not. For most teams, the shift randomization was made at the unit level (e.g., all or none of the officers received cameras each shift). The units in the study were:

-

GTPPs: These tactical units often engage in armed confrontations. GTPPs are not deployed to fixed geographic areas but to locations where special operations occur. There were three GTPP units during the study, each with five to seven officers.

-

GPPs/Visibilidades: These units are assigned to fixed geographic areas and carry out foot patrolling. GPPs perform “proximity” policing functions. Most units have two to three officers working shifts of 12 h.

-

GPPs/Bases: These are deployed to fixed geographic areas and carry out regular patrolling functions. They have more police officers (four to five) and have shifts of 24 h.Footnote 10

-

Supervisors: There are only two supervisors in the UPP, and they work 24-h shifts. For supervisors, we randomized the days (full weeks) when they received a camera from February to July.

-

Radio/Patrulhas: These were included in July at the request of the UPP Commander. They are smaller units (two officers) deployed with vehicles to fixed geographic areas.

Some treated units randomly received a camera during every shift, but other officers received a camera during only some shifts. This strategy allowed us to compare treated and control units and officers within the same unit at different points in time with and without cameras, as shown in Figure 11 of the Appendix. Our study initially varied the treatment (camera assignment) within treated units across two dimensions:

-

Coverage: Some treated units were randomly provided cameras for all police officers working that shift (“full team”). In contrast, the rest of the treated units were provided cameras for only half of their officers (“half team”). In this later scenario, cameras within a unit were randomly assigned among officers during each shift. The objective of this variation was to assess whether all or only some officers needed to be equipped with a camera to observe an impact on their behavior.

-

Usage protocol: officers in some units were randomly assigned to the protocol that asked to turn their cameras on during their entire shifts (“always-on mode”). Other units were randomly required to turn on their cameras only when interacting with citizens (“interactive mode”), which is the prevalent practice in the USA. Our intuition was that it would be more difficult for officers to refuse to turn on their cameras if they were asked to record their interactions all the time. Unfortunately, as we report below, the “always-on mode” had to be abandoned in the middle of the study.

Each officer assigned to a camera received a copy of the protocol they were expected to follow along with the official publication of the document. Each day, cameras were distributed by Rocinha’s Armament Reserve. Thirteen docking stations were placed to recharge the body cameras and download recordings. Every day, officers in charge of distributing and registering equipment would provide a camera to each officer assigned to the experiment. Additionally, the Armament Reserve displayed a printed copy of both protocols outside its glass window. Several training sessions were conducted on using the cameras and following the protocols best.

Changes in the Design of the Study

Conducting a field experiment in a highly volatile setting was challenging. The original study had to be re-designed in three ways. In February, we had to drop the “half team” variation of the treatment. At first, to assign cameras to half or full teams, we collected information about police officers’ monthly shifts. Armament Reserve’s officers received a monthly assignment spreadsheet and distributed the equipment accordingly. After a month, we realized that officers were often moved daily to different shifts. This meant we needed to collect information on officers’ daily changes to improve compliance with the randomization and treatment assignment. On the previous night, Armament Reserve officers received the researchers’ assignments for the next day. But this implied that we could no longer randomize the “half team” variation. Notably, after we began collecting officers’ shifts daily, compliance with camera assignment improved to more than 90% (as seen in Figure 13 of the Appendix).

The second change came in May 2016 when there was a change in Rocinha’s UPP Commander, who implemented substantial changes to the size of the units and their territorial distribution. Some units previously allocated to the study were disbanded, and new units were added. These changes affected five of the ten original GPPs-Visibilidade units, which merged into three new units assigned to the control group. The territoriality of the other GPP-Visibilidade, GPP-Base, and GTPP units remained unchanged.

The last significant change came in July 2016, after the PMERJ organized group conversations with officers in the study to discuss the importance of the cameras and reinforce the protocol. It was clear from those conversations that officers felt highly uncomfortable with the full-time (“always on”) protocol and that efforts to improve compliance among officers assigned to this treatment were unsuccessful. Consequently, we adjusted our study and dropped this variation of the treatment.

Table 1 shows the number of shifts in the control and treatment groups by unit type. Bases (GPPs 24 h) assignment was constant across the study (two units in the control group and two in the treatment group). Two of the three GTTP units were permanently assigned to the treatment group. Nevertheless, we varied the months each unit was assigned to these groups. The higher percentage of shifts in the treatment group for GPPs/Visibilidade reflects the creation of new units after the start of the study and the existence of smaller GPP units assigned to the treatment group during the length of the study.

Reactive and Proactive Policing Activities and Other “BOPMs”

Our first dependent variable is registered “occurrences” (also called BOPMs). Each occurrence is reported by the leader in charge of the unit involved in the incident. Table 2 classifies the BOPMs into reactive and proactive policing activities (Black, 1980). We also show other registered BOPMs for which it is unclear whether the police action was reactive or proactive. Reported BOPMs correspond only to the units that were part of the study. Close to half of the occurrences (49%) involve reactive policing activities, of which 354 are calls to 911 at the operation center. Calls included in this category concern potential thefts, robberies, domestic violence incidents, loud noise complaints, street fights, and gunshot reports, among others. These calls are received at the operation center. “Requests” originate in response to an invitation made directly to an officer by a civilian in the street, a colleague officer, or other security agents. This category mainly comprises street incidents, including fights and brawls, robberies, traffic accidents, and medical emergencies.

The second category of BOPMs we study involves proactive policing. These include stop-and-searches (“abordagens”), “encounters” that consist of all the “random or un- expected” interactions or events police officers experience during their regular patrols, interactions with “suspicious individuals,” events where police claim suspects “initiate the aggression,” and events that are said to “disrupt the peace.” We group these into one category: stop-and-search and other encounters.

Overall there was minimal policing activity in Rocinha during the study. One reason is that, as our community survey revealed, residents prefer not to report crimes or approach the police. In many of Rio’s favelas, residents like to take care of themselves. Many resort to the tribunal do tráfico (drug traffickers’ tribunal) to report crimes and resolve communal conflicts because they experience the police as agents of oppression and trust drug lords more (Magaloni et al., 2020). It is also likely that many police-civilian interactions were not registered, which is quite common in other countries, including the USA. Unfortunately, we cannot measure the effect of cameras on interactions that were not recorded. Had officers complied with the “always-on mode” protocol, the problem of having interactions that are not registered could have been minimized.

Main Findings

Effects of Camera Assignment on Reactive and Proactive Policing

In this section, we assess the effect of camera assignment on the probability of officers’ involvement in proactive and reactive activities. Since BOPMs are reported at the unit/shift level and not at the individual-officer level, our units of analysis are GPPs/Visibilidade, GPP/Bases, GTTPs, and Radio Patrulhas. The former two are grouped because both are similar and perform “proximity policing” functions. Given that 50% of the shifts that registered a BOPM did not record it, the analysis in this section will focus on intention-to-treat (ITT) effects. We consider a shift treated when one or more police officers in a shift are assigned to a camera, regardless of whether they turned it on or not. We contrast the behavior of these shifts with those that did not get cameras.

Table 3 shows the coefficients of logit models on the probability of an occurrence during a particular shift. We ran two models for each type of BOPM: the first isolates the effects of camera assignment controlling for the unit type, and the second interacts camera assignment with unit type. For the heterogeneous effects models, we exclude Radio Patrulhas because they generated few observations in the treatment group, and the models cannot calculate marginal effects. GTTPs serve as the baseline category. All models are logits where we code as 1 when there is any event in the shift and otherwise. Since treatment was assigned at that unit-shift level, we cluster errors at that level (Abadie et al., 2017). As robustness tests, we ran OLS regressions with the exact zero-one specification and total BOPMs. All results are consistent.

The results for models 1, 3, 5, and 7 demonstrate that body-camera assignment strongly discouraged potentially aggressive stop-and-searches and other encounters with civilians, as well as essential policing activities, including responding to calls to the operation center and street requests.

To explore the magnitude of the effects, Fig. 4 presents the results expressed as odds ratios. The predicted probability of police engaging in stop-and-search and other encounters reduces by 39%Footnote 11 when officers are assigned a camera. The effect of using a camera translates into a 43% reduction in calls and dispatch from the operation center. Cameras led to a 60% reduction in police response to street requests. Overall, camera assignment decreased total BOPMs by 46%.

Predicted effects of camera assignment on BOPMs. Notes: Estimated effects and their 95% confidence intervals come from logit models 1, 3, and 5 of Table 3. Effects are calculated as odd ratios. Errors clustered at the unit level

Models 2, 4, 6, and 8 in Table 3 interact units with the treatment. Across these models, we find that cameras do not reduce policing activities by GTTPs but strongly discourage GPPs from engaging in proactive and reactive policing. We speculate that two factors drive the differential impact of cameras among GTTPs and GPPS. First, GPPs have the most direct interaction with civilians, and as can be seen in Table 2, they generate most of the proactive and reactive policing activities. In these interactions, there is substantial “street-level” discretion and the potential to abuse authority. For example, according to our qualitative interviews with residents, GPP officers often use offensive language, abuse their power by using unnecessary force (e.g., “slap suspects,” “pull hair,” “hitting”), and threaten civilians. GTTPs do not engage in “proximity policing” but are deployed directly by the UPP Commander to perform special operations, including engaging in armed confrontations with drug traffickers and general anti-narcotics operations. It means that GTTPs have less discretion than GPPs because the Unit Commander closely supervises them.

Modality of Treatment and Supervision

In this section, we model the probability of an occurrence for each treatment modality focusing again on intention-to-treat models (e.g., camera assignment.) To report the results in one table, we group in row one what we label here “half treatments.” These correspond to the following modalities: “some officers,” “interactive mode,” and “supervisors with no camera.” In row two, we group “full team,” “always-on mode,” and “supervisors with camera.” Data for each treatment modality is from the time such modality was in effect: Coverage (November to February), Protocol (November to July), and Supervisors (February to July). As before, we use logit models where the dependent variable is coded as one-zero, reflecting the presence or absence of an occurrence during a shift, respectively.

Model 1 in Table 4 shows the effects of coverage on the probability of a BOPM. Relative to the control group, when cameras are assigned to a shift, regardless of whether to “full teams” or “half teams,” this reduces the probability of a BOPM; it should be noted that the “half team” mode is barely statistically significant. Model 3 shows that when shifts are assigned to the “interactive” mode, police are significantly less likely to engage in a BOPM. The “always-on” mode is also negative but statistically indistinguishable from the control group. Lastly, model 5 shows that when supervisors are randomly assigned a camera, the probability of a BOPM significantly increases relative to when they are not wearing a camera.

Models 2, 4, and 6 modalities of treatment with camera assignment. Model 2 shows that when “full” and “half” teams are assigned a camera, shifts register significantly fewer BOPMs. In terms of protocol, model 4 reveals that the “interactive mode” produces significantly fewer BOPMs when police are wearing a camera. When we interact the “always-on mode” with camera assignment, the coefficient is not statistically significant. Hence, relative to this protocol, the “interactive mode” appears to produce stronger effects dissuading officers from registering more BOPMs. The results are suggestive that these protocols affect police behavior differently. Still, unfortunately, since we had to abandon this treatment modality, the study did not generate enough observations to reach a solid conclusion.

Effects of Assigning Cameras to Supervisors

The most notable effect of these treatment modalities was randomly assigning cameras to supervisors. Figure 5 estimates the marginal effects for models 5 and 6. The figure on the left shows that when supervisors wore a camera, the probability of a BOPM increased by 300%, from .01 to .04. The figure on the right shows how the treatment of supervisors and officers jointly impacts the probability of a BOPM. Whether officers wore a camera or not, assigning a camera to supervisors significantly increased the likelihood of a BOPM. Note that when officers wore a camera and supervisors did not, the probability of a BOPM was relatively low, and this increased by 200% when supervisors were jointly assigned a camera. These substantial effects point to the critical importance of local supervision and how, when they were given a camera, this mitigated the de-policing effect cameras induced.

Camera assignment to supervisors: Estimated marginal effects on BOPMs. Notes: Estimated effects and their 95% confidence intervals come from logit models 5 and 6 of Table 4

Camera Assignment Compared to Cameras that Are Turned on

Of the 11,386 shifts in the study, 70% of officers did not turn their cameras on. The camera protocol required officers to record their interactions. When we focus on registered BOPMs per shift, the police did not record 50% of these. In this section, we analyze treatment effects focusing on the differences between camera assignment and cameras turned on. Our dependent variable is the probability of a BOPM. We use a zero-one specification of the dependent variables and logit models. Results are presented in Table 5.

For all types of BOPMs except responding to street requests, the probability that an officer performed a policing activity when they recorded the event was larger and statistically significant than when they did not. Figure 6 presents the marginal predicted effects of recording. The results are suggestive that police engaged in fewer BOPMs because they did not want to record them. Importantly, when officers recorded the event, the de-policing effect induced by the cameras disappeared in the case of total BOPMs and calls to the operation center. Although the impact of recording is also positive and statistically significant for street requests, the 95% confidence intervals are too wide to make sound inferences on marginal effects, probably because of the small number of observations regarding recorded events. Our results demonstrate that wearing a camera, and not only turning the BWC on, had a strong deterrent (or de-policing) effect: in this case, inducing officers to engage in fewer policing activities, both proactive and reactive.

Estimated marginal effects of turning the camera on to record. Notes: Estimated effects and their 95% confidence intervals come from logit models presented in Table 5

Use of Deadly Force

In addition to BOPMs, we gathered official information on the number of daily gunshots fired per officer. The PMERJ provided this database and does not include personal information on the police officers (name, sex, age, etc.) other than a unique numerical identifier, which the authors are not allowed to share.

At the beginning of a shift, a police officer receives weapons and ammunition to be kept under his custody for the duration of the shift. The gun number and the quantity of ammunition delivered are saved on a record. At the end of the shift, an officer must return both the gun and the bullets that were not used. The difference between what is received and what is returned is recorded as gunshots fired. In addition, an officer must report all the incidents during his shift, including those where he used ammunition. Each occurrence is assigned a numeric code (or TRO) and includes information on the date and time of the event, battalion, use of ammunition, gun number, and type of gun (high-speed vs. low-speed).Footnote 12

Figure 7 shows the number of gunshots police fired since creating the UPP in Rocinha. At its outset, the UPP began with a few events involving deadly force. Violence escalated soon after the UPP was implicated in the torturing and killing of Amarildo de Souza in the summer of 2013. Shortly after that event, there was a clear escalation of armed confrontations. According to the General Commander of Operations at the time, the UPP lost control of the favela after the Amarildo scandal. At the end of 2014, the PMERJ deployed the special operations battalion, BOPE, to Rocinha for several months. During this period, there was a sharp increase in gunshots, which began to decrease by April 2015. Our study began in December 2015, 9 months after armed confrontations had significantly declined.

To investigate if cameras affected the reduction of gunshots fired, we confront the challenge that there were only 27 events involving gunshots during our experiment. Table 6 presents the number of bullets fired during these events by treatment, control groups, and unit type. There were 306Footnote 13 bullets fired when police were not wearing cameras and 154 when they were wearing cameras. GPPs fired zero shots when they were wearing a camera and all of their 113 shells when they were not wearing a camera. Although GTPPs fired a significant number of bullets (154) when they were wearing a camera, they still fired more shots (193) when they were not wearing a camera.

Regarding the number of bullets per event, Table 6 shows that GPP fired 11.2 when they were wearing a camera and not bullets when treated. GTTPs fired 16.38 shots per event without cameras, increasing to 32.16 with cameras. Although GTTPs fired more bullets per event with cameras, there was a dramatic reduction in the total number of shots fired in Rocinha relative to the 3666 bullets fired in the previous year.

The apparent decrease in gunshots during our study could be explained by the fact that significantly fewer officers (27) participated in a shooting event compared to the number participating in the year before our study (282). We do not present statistical models of treatment effects because of the challenge of using such a small number of events to make sound inferences. Hence, our conclusion that cameras reduce deadly force should be taken with extreme caution.

Officer-Involved Killings

The gunshot data provided by the PMERJ do not identify the bullets that produced death. To assess whether fewer gunshots translated into fewer officer-involved killings, we must move beyond the data generated by the experiment. The number of officer-involved killings comes from the Civil Police (an investigative body institutionally distinct from the PMERJ) that registers these killings, which are then reported by the Instituto de Segurança Pública (ISP). From September 2012 to just before the experiment started, the police killed eight people, two of these during the year before the experiment. According to the ISP, there were no officer-involved killings during our study. After the study ended and until the end of 2018, the police killed eighteen more people.Footnote 14

An additional concern that one might have regarding the apparent reduction of the use of gunshots stems from the fact that during 2016 Brazil hosted the Olympics in Rio, and this event might have led the police to behave less violently everywhere, not only in Rocinha, to create an image of “peace” to the outside world. To challenge this argument, Fig. 8 shows that during our study (between the vertical lines), officer-involved killings are decreasing in Rocinha but sharply increasing in the rest of the UPPs. Hence, the Olympics are not associated with a generalized reduction in officer-involved killings.

Given that no people were killed by police during our study, one might question whether Rocinha is a setting where police violence is high. We note that the data on gunshots reveal that the favela can be set on fire at any moment due to armed confrontations between police and heavily armed criminal groups. Between 2012 and 2015, the UPP in Rocinha registered 93 wounded people, yet during our study, nobody was injured. Not surprisingly, in our survey, most residents reported being terrified of “being killed by the police.” Qualitative evidence also suggests that residents constantly fear being injured by lost bullets. Many said it was unsafe to walk in the favela after the UPP entered. In reality, favela residents are constantly caught in the crossfire with many bullets flying around. Moreover, we also highlight that although not lethal, police violence is also present when police stop and frisk, slap faces, or hit people which is common in Rocinha.

Camera Usage

Even though camera assignment produced strong behavioral effects, the extensive disobedience of the camera protocols—particularly, officers’ resistance to record—is concerning. In this section, we seek to answer a critical question: what distinguishes police who obeyed the camera protocols from those who resisted recording their interactions?

Figure 9 shows the percentage of cameras turned on during a shift. At the beginning of the study, there was high compliance, with 40% turning their cameras on at least once during a shift. This number drops to less than 5% in August, and usage increases to around 10%. Moreover, the number of minutes cameras were turned on was minimal—average usage across all cameras was 1.4 min per hour. Those cameras that were turned recorded an average of 7.5 min per hour.

Percentage of assigned cameras that were turned on. Notes: Long-dashed line: video footage management moved to the 23rd Battalion. Dashed line: PM publishes an order that every Occurrence must be recorded. Solid line: “always on” mode is eliminated. Dotted line: monthly body-camera usage reports are distributed to officers

The PMERJ’s first attempt to have a team of police officers work on the footage at the Central Headquarters of the UPPs (CPP) ultimately failed. After three rounds of training and numerous discussions about the recording process, the PMERJ’s High Command and the research team concluded that moving the infrastructure of footage management to Rocinha’s UPP—with a room, supervisor, and team only dedicated to performing this task—was necessary. By the end of April, the footage was physically allocated to Rocinha, which comprised a full-time coordinator and six officers working under the supervision of Rocinha’s sub-commander. As shown in Fig. 9, moving the footage management to Rocinha increased camera usage between April and May. However, even after the creation of this team exclusively dedicated to monitoring the images, the video recordings were barely watched. Moreover, during the study, it was never clear to front-line officers what behaviors their superiors were trying to reward or punish.

The PMERJ’s High Command implemented other actions to improve camera usage: they published a protocol in their Official Bulletin introducing a new rule, starting in May 2016, to reinforce the fact that every police report (BOPM) generated by an officer using a camera had to be recorded. The document provided procedures for penalizing officers who refused to turn their cameras on when interacting with civilians and registering a BOPM. Lack of protocol compliance would lead to a Direito de Razão de Defesa, a formal document superiors provide to police officers that gives them a warning and the opportunity to explain their misconduct. As shown in Fig. 9, this change in protocol increased camera usage in May. However, because local supervisors in Rocinha did not report officers who disobeyed, use began to decline precipitously after May.

Researchers implemented two more measures aimed at improving camera use. In August, we began to distribute reports on daily camera use to police officers. Upon collecting their cameras at the station, each officer received a printed copy of an individual report showing their daily camera usage during that month. Moreover, we created a monthly procedure to identify the worst-performing officers. Given the high level of non-compliance, we randomly selected four officers from among those with less than 2 min of recording; these officers were then called upon by their superiors to explain their low usage. Camera usage increased in September after these measures. However, it remained low until the end of the study because, as our interviews revealed, supervisors did not prioritize enforcing the camera protocols.

Factors Associated with Camera Usage

This section provides systematic evidence about the factors associated with officers’ willingness to turn their cameras on. We merged the data regarding camera usage with our police surveys, with the procedure we detail in the Appendix. We were able to match a total of 416 surveys out of 674. The Appendix shows that the matched reduced sample and the entire sample are mostly balanced. We use the following covariates:

-

Community hostility index: A composite index of answers to six questions about different types of aggressive community behaviors against officers, reported in Fig. 3. Our index has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88, which suggests that this measure has internal consistency. The higher the perceived community hostility, the more we expect the police to turn their cameras on.

-

Armed confrontation index: A composite index of three questions, also reported in Fig. 2: firing a gun, engaging in an armed conflict, and seizing guns. Our Cronbach’s alpha is 0.75. We expect higher levels of the index to induce less camera usage.

-

Supervision: A dummy variable indicating if the police reports regarding camera usage were being supervised. We expected this variable to have a positive effect on camera usage.

-

Officer wounded: A dummy variable indicating whether the officer had ever been injured with a gun while in service. We expected this variable to have a negative effect.

-

Officer wounded someone: A dummy variable indicating whether the officer has ever injured “one or many persons” with a firearm while in service. We expected this variable to discourage police from recording their interactions.

We use an OLS regression where the dependent variable is the number of minutes the officer turned his camera normalized by the number of minutes the officer was assigned a camera. This is calculated from the beginning of our study to when the survey was collected. For officers who answered more than one survey, we calculate camera usage until the moment of the survey collection to avoid double counting. Our models control for officers’ demographics (age, education, race) and unit.Footnote 15 Errors are clustered at the unit-shift level. We exclude four instances of very high camera use to ensure that outliers do not drive our results. Results are presented in Table 7.

Our results support the conclusion that police who reported experiencing more aggressive behaviors from the community turned their cameras on more often. Contrary to our expectations, the higher the armed confrontation index, the more police turned on their cameras. The more officers reported being supervised using the cameras, the more they turned them on. Police who have been wounded in the past use their cameras less, although this variable is barely statistically significant. Finally, officers who have injured one or many persons in the past resisted recording their interactions at higher rates. These results are troubling because they reveal that more violent officers, who are more likely to be abusive, are also more prone to resist recording.

Organizational Culture

This section aims to gain insight into how organizational culture and police mentality shaped BWC adoption. We report findings from the police survey, interviews, and focus groups.Footnote 16 Drawing from our police surveys, although 80% reported being “aware of punishments for not using the cameras,” only 9% said they had received a warning for disobeying. Importantly, only 35% reported that they were “frequently” or “sometimes” supervised regarding camera usage. In essence, there was no explicit endorsement of the cameras by local supervisors and the UPP Unit Commanders. Like the UPP Unit Commander in the epigraph, the other two local UPP commanders assigned to Rocinha during our study also believed that cameras would “prevent officers from doing their jobs.” It is worth reflecting on what precisely police in Rocinha’s UPP believe their job to be.

In the baseline survey, we asked officers to choose three options concerning the UPP’s primary goal. A staggering 71% responded that it was to “combat drug trafficking.” Only 21% said it was to “reduce violence” and 8% to “service the community.” This “war” orientation toward crime-fighting, which distorts policing from its function as a guarantor of law and order to combat criminals in “war,” leads officers to act in rough and often unlawful manners. Officers explained that, in the violent environment in which they are immersed, it is often impossible to respect the laws. An officer articulated why: “criminals will most certainly try to shoot us to kill if they have the chance. Although the “correct” action is to enter an operation without shooting before any shots are heard coming from the other side, we cannot afford to do this.” He added that, as the famous saying goes, “those who shoot to kill must be shot at to die.”

Other officers justified their rough actions based on the risks armed confrontations pose to their lives. An officer said: “Everyone here has a story of being very close to death. The risk of dying and leaving our families behind or becoming invalid is genuine. Then, you think ten times if it is worth it to run after a criminal and risk your life or if you should shoot and walk the other way.” Responding to this comment, a peer added: “If I am in a position like that, I’ll shoot until the guy stops.”

Most officers spoke to what they saw as “the unfeasibility” of expecting the police to run after criminals during an operation instead of shooting. But a few others manifested a further desire to bring “justice” when the laws fail to punish criminals. An officer made the following malicious and cruel comment: “Good-for-nothings (vagabundos) are all the same. It does not matter if they are eight or ten years old. If I can do it [shoot to kill], I will ... the laws are not on our side. You arrest a criminal today; tomorrow, he is back on the streets.” Adding to this comment, another officer told us: “The judicial system needs to be changed. Once, I arrested the same guy twice in one week.” Another police officer added: “This is why it is better to kill than to arrest.” Officers stated that there are many administrative hurdles when a death occurs in their jobs. “When officers kill a civilian, the sergeant comes after us, then the commander. We must go to the police station, where the police chief will interrogate you. Then you go to the CPP (Central Headquarters of the UPP). Once this is all done, you have already lost one of your days off.”

This last comment is incredibly telling about the level of “numbness to killing” some officers have achieved. Here, he talks about the stress involved in going through all the administrative steps when you kill someone, but not about the stress that taking a life must cause. The effort to substitute the warrior and vigilante tactics and mentalities with the creation of a community-oriented police force failed. As a UPP officer told us: “There is a duality inside the organization. They teach us one thing but expect something different.” Even though UPP officers were supposed to engage more with the community, they are still trained and expected to act like soldiers as they wage “a war against crime.” It is evident in many of these comments that if cameras were to be used properly, they would indeed generate images that could be highly prejudicial to the officers. An officer expressed his resistance to the cameras: “Nobody is obligated to generate proof against themselves ... but that happens with the police officer when he is wearing a camera.”

The police building of Rocinha’s UPP is just a tiny office made from metal. A police officer told us: “We are in the enemy’s territory, and we have been completely abandoned [by the state].” Officers pointed to the numerous bullet holes the building has taken and underscored the extent to which the state left them “right in the wolf’s mouth.” Reflecting on the broader institutional context, a policeman told us: “You do not see anything in here … no basic sanitation, no schools, no universities, no health centers. Only the police are here, and we are always seen as the villains in the story.”

The tragedy is that favela residents are caught between two enemies at war. In our surveys, 85% told us that residents frequently or sometimes refuse to cooperate with the police, and 65% told us they feel “that residents threaten their physical well-being.” Interestingly, police saw a benefit to turning on their cameras to protect themselves from residents’ aggressive behaviors. An officer reflected on the utility of the cameras with the following words: “I think some people look at the camera and think: ‘I better not try anything. He is filming everything.’” Another officer added: “They [favela residents] think that we are filming at all times ... some of them even avoid walking in front of us.”

Conclusion

This study is the first randomized experiment on police body cameras in a favela, a high-violence setting in Brazil. Our statistical models demonstrate that camera assignment strongly deterred stop-and-searches and other encounters with civilians. The reduction of stop- and-searches and other proactive encounters where officers have a great deal of street discretion and often abuse their authority by using unnecessary force (e.g., “slap suspects,” “pull hair,” “hitting,” “physically attack”) was a positive outcome of the cameras.

The research showed that aggression goes both ways. Many police officers report being “cursed,” “thrown water, urine or stones,” and suffering “verbal” threats and “physical attacks” from residents. These forms of community aggression toward the police decreased during the study, suggesting that the deterrence channel induced by the cameras operated both ways, restraining police abusive behavior toward residents and aggressive behavior toward the police.

We also found that cameras produced a solid de-policing effect, where police stopped performing necessary functions such as calls and dispatch from the operations center and responding to street requests. There is also suggestive evidence that cameras reduced the use of deadly force, which we measure with the number of bullets fired by treatment and control officers, although this conclusion should be taken with extreme caution given the small number of events where police fired their guns.

Police changed their behavior when assigned a camera even in the absence of video recordings. Two factors explain why camera assignment, and not its usage, can serve as a deterrent. First, since officers were obliged to record their interactions, many refrained from engaging with civilians to avoid recording their interactions. Second, behavioral changes could have been driven by an indirect psychological effect where police felt more scrutinized by the PMERJ’s High Command because they were assigned a camera.

The fact that police did not record many of their interactions uncovers a limitation of this technology. When we explored the factors associated with camera usage, we find an unsettling result: police officers who refused to record were more likely to be violent. By contrast, police who recorded more reported being victims of community aggression, indicating that police saw a benefit in using the footage to protect themselves.

Hence an important limitation of BWCs is that they give too much freedom to the police to activate them. Where there is ample disobedience with protocols, cameras might need to be activated from the main station, withdrawing this decision from frontline officers. This technology already exists and might be something to consider in places like Rio de Janeiro.

Another limitation of the technology comes from the supervisors themselves. In our case, supervisors might have tried to sabotage the cameras by refusing to enforce the protocols. If abusive officers can turn their cameras off without worrying that their supervisors could sanction them, BWCs will not be as effective deterring police abuse. We suggested that one way to deal with this problem is to assign cameras to supervisors.

Moving forward, the motivating question of how best to control police abuse brings us back to the opening epigraph from a UPP Unit Commander in Rocinha who warned us that police would “refuse to do their jobs if they wore cameras.” This comment summarizes well some of this study’s findings. We observe a culture so ingrained in the construction of policing that introducing systems of accountability would lead police officers to stop doing their job. This, then, raises a similarly interesting question: what exactly is their job? As this paper revealed, police conceive their job as to wage “war with criminals.” In this ensuing battle, the very communities police are supposed to protect are seen as hostile forces.

Availability of Data and Materials

All data will be made available for replication purposes.

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Notes

The PMERJ is a uniform civilian body in charge of ostensive policing and preventing patrolling.

According to the Brazilian Census, favelas are irregular urban agglomerations.

The PMERJ differs from the Civilian Police as a plain-clothed investigative force.

During this period, Google Ideas and the Igarap´e Institute ran a small body-camera pilot program in this unit. The pilot included very few cameras and was neither designed as an RCT nor evaluated with systematic data.

Details relating to our collection methods are provided in the Appendix.

We collected 268, 235, and 171 responses, respectively.

Drug and arms seizures can also result from special operations ordered by the unit commander.

We did not ask directly if the officer had killed someone because, from prior work, we learned that police often refuse to answer this question.

Later in the study, these units were called Patrulhamentos.

Calculated as 1 − 0.61.

Extensive interviews with officers at the Armament Reserve of various Battalions and UPP Units collected for a different project point to the difficulty of misreporting the number of gunshots fired because frontline officers and officers in the Armament Reserve can be personally held accountable for the monetary value of the bullets when these are missing and not registered in a TRO.

This number includes treatment and control units only.

This information seems to be at odds with our police survey, reported in 2. According to that survey, when the study ended, 2% of the officers said that they “had participated in an event where someone was killed during the last year.” The apparent discrepancy between our police survey and the data ISP reported likely comes from two sources. First, more than 40% of officers were transferred to and from Rocinha’s UPP during our study. The officers who reported participating in an event where someone got killed or injured might have performed such killing or injury in a different Territorial Battalion, UPP, or Specialized Unit, including BOPE. Second, our interviews revealed that it is common for police officers, particularly those from the special operations unit, the GTPPs, to be deployed to support police operations outside their unit. This means that the 2.2% who in our survey reported killing someone during our study might have done so outside Rocinha.

We also control for the survey wave.

We collected interviews with the Military Police High Command, the General Command of the UPPs, Rocinha’s UPP Commanders and supervisors, officers from the Armament Reserve, police in charge of supervising the images, and three rounds of focus groups with frontline UPP officers.

References

Abadie, A., Athey, S., Imbens, G. W., and Wooldridge, J. (2017). When should you adjust standard errors for clustering? Technical report, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Ariel, B. (2016). Increasing cooperation with the police using body worn cameras. Police Quarterly, 19(3), 326–362.

Ariel, B., Farrar, W. A., & Sutherland, A. (2015). The effect of police body-worn cameras on use of force and citizens’ complaints against the police: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 31(3), 509–535.

Ariel, B., Sutherland, A., Henstock, D., Young, J., Drover, P., Sykes, J., Megicks, S., & Henderson, R. (2016). Wearing body cameras increases assaults against officers and does not reduce police use of force: Results from a global multi-site experiment. European Journal of Criminology, 13(6), 744–755.

Black, D. (1980). The manners and customs of the police. Academic.

Brehm, J. and Gates, S. (1997). Working. Shirking, and Sabotage: Bureaucratic Response to a democratic public.

Brinks, D. M. (2007). The judicial response to police killings in Latin America: Inequality and the rule of law. Cambridge University Press.

Caldeira, T. P. (2002). The paradox of police violence in democratic Brazil. Ethnography, 3(3), 235–263.

Cano, I. (2010). Racial bias in police use of lethal force in Brazil. Police Practice and Research: An International Journal, 11(1), 31–43.

Cano, I. and Duarte, T. (2012). No sapatinho: a evolu¸c˜ao das miĺıcias no Rio de Janeiro (2008–2011). LAV, Laborat´orio de Análise da Violˆencia (LAV-UERJ).

Dixit, A., Grossman, G. M., & Helpman, E. (1997). Common agency and coordination: General theory and application to government policy making. Journal of Political Economy, 105(4), 752–769.

Dowdney, L. (2005). Neither war nor peace. International comparisons of children and youth in organized armed violence.

Fryer, R. G., Jr. (2019). An empirical analysis of racial differences in police use of force. Journal of Political Economy, 127(3), 1210–1261.

Gailmard, S. (2009). Multiple principals and oversight of bureaucratic policy-making. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 21(2), 161–186.

Glaser, J., Spencer, K., & Charbonneau, A. (2014). Racial bias and public policy. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 1(1), 88–94.

Godoy, A. S. (2006). Popular injustice: Violence, community, and law in Latin America. Stanford University Press.

Gulzar, S., & Pasquale, B. J. (2017). Politicians, bureaucrats, and development: Evidence from India. American Political Science Review, 111(1), 162–183.

Jennings, W. G., Lynch, M. D., & Fridell, L. A. (2015). Evaluating the impact of police officer body-worn cameras (bwcs) on response-to-resistance and serious external complaints: Evidence from the Orlando police department (OPD) experience utilizing a randomized controlled experiment. Journal of Criminal Justice, 43(6), 480–486.

Knox, D., Lowe, W., & Mummolo, J. (2020). Administrative records mask racially biased policing. American Political Science Review, 114(3), 619–637.

Lessing, B. (2015). Logics of violence in criminal war. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 59(8), 1486–1516.

Lum, C., Stoltz, M., Koper, C. S., & Scherer, J. A. (2019). Research on body-worn cameras: What we know, what we need to know. Criminology & Public Policy, 18(1), 93–118.

Magaloni, B., & Rodriguez, L. (2020). Institutionalized police brutality: Torture, the militarization of security, and the reform of inquisitorial criminal justice in mexico. American Political Science Review, 114(4), 1013–1034.

Magaloni, B., Franco-Vivanco, E., & Melo, V. (2020). Killing in the slums: Social order, criminal governance, and police violence in Rio de Janeiro. American Political Science Review, 114(2), 552–572.

Magaloni, B. and Cano, I. (2016). Determinantes do uso da for¸ca policial no Rio de Janeiro. Editora UFRJ.

McCluskey, J. D., Uchida, C. D., Solomon, S. E., Wooditch, A., Connor, C., & Revier, L. (2019). Assessing the effects of body-worn cameras on procedural justice in the Los Angeles police department. Criminology, 57(2), 208–236.

Mummolo, J. (2018). Modern police tactics, police-citizen interactions, and the prospects for reform. The Journal of Politics, 80(1), 1–15.

Ready, J. T., & Young, J. T. (2015). The impact of on-officer video cameras on police– citizen contacts: Findings from a controlled experiment in mesa, az. Journal of Exper- Imental Criminology, 11(3), 445–458.

Skolnick, J. H., & Fyfe, J. J. (1993). Above the law: Police and the excessive use of force. Free Press.

Streeter, S. (2019). Lethal force in black and white: Assessing racial disparities in the circumstances of police killings. The Journal of Politics, 81(3), 1124–1132.

Westley, W. A. (1970). Violence and the police: A sociological study of law, custom, and morality (Vol. 28). MIT Press Cambridge.

Willis, G. D., & Prado, M. M. (2014). Process and pattern in institutional reforms: A case study of the police pacifying units (upps) in Brazil. World Development, 64, 232–242.

Funding

This project was funded by a generous grant from the Stanford Business School, Global Development Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Beatriz Magaloni wrote the main text, designed the experiment, and performed the statistical models, including producing all tables and figures. She also designed the survey instruments, secured funding, and conducted the fieldwork. Vanessa Melo supervised the implementation of the experiment, conducted fieldwork, and contributed to collecting and designing the surveys. Gustavo Robles contributed to the design of the experiment and dataset assembly. He performed statistical models and analyses in the preliminary versions of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Study Design

Officers Assigned to Treatment

During the study (December 2015 to November 2016), about 470 police officers were monthly assigned to UPP Rocinha on average, totaling more than 52 thousand individual shifts. From those, around two thirds were included in the study, as can be seen in Table

8 in Appendix. The rest of the officers held administrative positions or were assigned to smaller or new units that were not included in the study.

There was a high turnover during the study with more than 850 different police officers being assigned to Rocinha at some point during the study. In fact, by November 2016, almost half of the officers in the study had been reassigned. The months with the highest turnover were May and October 2016. The high turnover is not uncommon in Rio’s PMERJ, although in this case was also associated with frequent shifts of commanders during the study.

Assignment

The study was aimed to units within the UPP that have patrolling functions or substantial amount of interaction with the residents. We considered 3 types of units according to their functions, policing area, and length of the work shift: (1) GTPPs, (2) GPPs/Visibilidades, and (3) GPPs/Bases/Patrulhamentos.

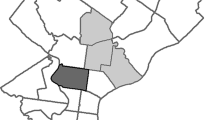

Figure 10 in Appendix shows the location of the GTPPs and GPPs in Rocinha at the beginning of the study. For the most part, our analysis will focus on GTPPs and GPPs. Within each type of unit (GTTP, GPP-Visibilidades, and GPP Bases), we randomly assigned full units into treatment and control groups.

Treated groups received body-worn cameras and control groups were not assigned cameras. In addition, in order to be able to make comparisons within units, we reassigned units to treatment and control groups at different stages of the study, as can be seen in Figures 11 and 12 in Appendix

Compliance with Camera Assignment

One of the main concerns of researchers was compliance with the daily distribution of the cameras, a critical task delegated to police officers at RUMB. Daily, RUMB’s staff received a document from researchers to distribute the equipment accordingly. Notably, the study had high compliance with camera assignments, improving distribution to 90% for the second half of the study. It is worth noting that compliance with camera assignment was particularly high after May 2016, as shown in Figure 13 in Appendix when we started receiving scheduled shifts on a daily basis instead of on a monthly basis. This helped reduced significantly the number of cameras that were not assigned due to errors in the shifts, which were planned monthly but changed constantly every day. The 10% of cameras not assigned consists mostly of police officers that did not show up to their shifts.

Ethical Considerations and Funding

All ethical safeguards were observed including approvals from our University’s IRB. Our research ensured risks to human subjects were minimal, while positive impacts have been significant. We worked for 9 years in Rio de Janeiro in partnership with the Ministry of Security, the Military Police, and various reputable NGOs in the favelas. Our studies produced tangible benefits on a problem that is of tremendous humanitarian importance. First, we build a massive data set on the daily consumption of bullets by individual police officers to track and monitor the excessive use of deadly force. Our work complemented that of Ignacio Cano, leading to removing 20 police officers from the street. In response to these contributions, a large retraining program aimed at 5000 officers on the progressive use of force was also initiated. The retraining program targeted seven battalions that generate the most police killings in Rio de Janeiro. We convinced the Military Police to temporally randomize treatment assignment and were evaluating their effects. When the newly elected governor openly asked police to “slaughter” criminals, we decided temporarily to halt our cooperation until better political conditions conducive to generating tangible results to control police violence emerge.

The project was funded with personal research funds of one of the researchers, Beatriz Magaloni, and a grant within our University. TASER donated 100 cameras and docking stations for the study, which we needed to import into Rio de Janeiro. When the study ended, the cameras and docking stations were returned to Taser.

Criminal Activity

We have demonstrated that BWCs cameras led to a substantial reduction in policing activities for GPPs, which are the units that respond to most incidents. An important question is if de-policing translated to an increase in criminal activities. Unfortunately, because no publicly available crime incidence data contains location information, it is impossible to match these occurrences to the areas and dates where officers used their cameras. As said above, we hired a local microenterprise, “Carteiro Amigo,” that provides mailing services to Rocinha’s residents to geo-reference crime reports that the military police provided to us. Nonetheless, because favelas lack official addresses and have a very irregular topography with many alleys and narrow streets, the information on their location was too vague and imprecise, which meant that we could only geo-reference 45% of these. Hence, the objective of this section is not to make causal claims about whether cameras increased or decreased crime but to inquire if there is an indication that during the period of our study, there was an increase in criminal activity, plausibly due to de-policing.

Table

9 in Appendix presents regression models for selected monthly indicators of criminal activity and law enforcement efforts with respect to different periods before and after the experiment. The coefficients should be read as how many events occurred in that period to the number of events observed during the experiment in 2016 (shown in the last row of the table). The results confirm there were no substantial differences in common criminal activity (using as a proxy the monthly number of thefts and robberies) during the experiment to 1 year before. In contrast, the number of monthly homicides and intentional injuries was lower during the experiment than in the previous 2 years. Finally, killings by the police and events of drug seizures were also lower during the experiment.

Analysis of Camera Usage with Survey Data

We collected three rounds of surveys with police officers. The baseline survey was collected in November of 2015 and rounds 2 and 3 in June–August and October–November of 2016. We collected 270, 230, and 170 responses, respectively. Question-wording for the items that were used in the analysis is available upon request.

The model of camera usage employs as a dependent variable the actual number of minutes the officer turned the camera during the study. Cameras were distributed by Rocinha’s “Reserva de Armamento e Munição Bélica” (Armament’s Reserve) located in the 23rd Battalion. Every day, police officers first stop at the station to get their daily equipment before heading to the favela. This process takes up to around an hour until officers can reach their final patrolling destination. A similar routine happens after each shift, when officers drop off guns and report the use of ammunition, in case of any usage. We merged usage data with our surveys. Because these were anonymous, we used the officer’s birthday as well as questions about his institutional trajectory in the Military Police to match this information with official data the Military Police use to identify officers by their RG, which is the same number used to distribute guns, bullets, and cameras. In line with IRB protocols, all this information is anonymized which means that the researchers do not have access to the officers’ names. Moreover, nobody beyond the researchers has access to the merged survey data with the RGs.

We were able to match a total of 416 responses out of 674. Table

10 in Appendix shows how many officers per survey round we were able to match. It also shows the number of officers who answered more than one survey. Because obviously, no police officer had used their cameras at the time the baseline survey was collected, our statistical analysis of camera usage uses bases 2 and 3. Per each round of survey, we input the total number of minutes officers had used their cameras from the beginning of the study until the time the survey was collected.