Abstract

Research Question

How concentrated is the total harm of offences with detected offenders (identified suspects) among the complete list of all detected offenders in a given year in an English police agency, and how consistent is the list of highest-harm “felonious few” offenders from one year to the next?

Data

Characteristics of 327,566 crimes and 39,545 unique offenders as recorded by Northamptonshire Police in 7 years from 2010 to 2016 provide the basis for this analysis.

Methods

Crime and offender records were matched to harm weightings derived from the Cambridge Crime Harm Index (Sherman et al. 2016a; Sherman et al., Policing, 10(3), 171–183, 2016b). Descriptive statistics summarize a concentration of harm identifying the felonious few, changes over time in membership of the “few”, offender typologies and tests for escalation of severity, frequency and intermittency across repeated offences.

Findings

Crime harm is much more concentrated among offenders than crime volume: 80% of crime harm that is identified to an offender is linked to a felonious few of just 7% of all detected offenders. While chronic repeat offenders are the majority contributors to harm totals of this group, those with the most general range of offence types contribute the most harm. Individual members of the felonious few rarely maintain that position year on year; over 95% of each year’s list is composed of individuals not present in previous years. Within individual crime histories, we observe a pattern of de-escalation in crime harm per offence over time. “One-time” offenders, those with just one crime record, typically made up a third of the felonious few in both number and harm contribution.

Conclusions

These findings demonstrate the potential to target a small number of repeat offenders for harm reduction strategies using a metric of total crime severity, not just volume, despite a substantial portion of crime harm caused by one-time offenders that may be largely unpredictable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Like most police forces in England and Wales, Northamptonshire Police have traditionally been place-based in most of its crime analyses, focusing on the profiling of demand and resources by jurisdictional boundaries. In 2017, the national police inspectorate (HMICFRS) recommended that police forces rethink their approach to offender management, with particular regard to the most prolific and dangerous offenders. Up to this point, these programmes had been primarily driven by considerations of crime volume. The recent development of the Cambridge Crime Harm Index (CCHI) afforded an opportunity to examine this issue from the perspective of the total harmfulness of each offender and not just the frequency of their offending (Sherman et al. 2016b). This article reports on the first application of the CCHI to a population of detected offenders over a multi-year period.

Research Question

In this analysis, we aim to build a better understanding of long-term, multi-year offending patterns by assigning weighted harm scores to police recorded crime data using the CCHI. Our aim is to contribute better evidence to decisions about how to set priorities for allocating scarce police resources. Our premise is that understanding the patterns of both harm levels and frequency of offending among the known population of offenders is a key part of evidence-based targeting. Moreover, such targeting depends heavily on systematic evidence of offending patterns from systematic tracking of the entire population of detected offenders. These aims lead us to address our overall research question: How concentrated is the total harm of detected offences among the complete list of detected offenders in a given year in an English police agency, and how consistent is the list of highest-harm “felonious few” individuals from one year to the next?

This general question is comprised of three analytic questions:

- 1.

What are the distributions and trends for the harm and frequency of detected crime across all offenders and repeat offenders, both within each year and year on year?

- 2.

Does offending among detected offenders escalate, remain steady or de-escalate in harm, frequency or intermittency over time?

- 3.

Is there a small felonious few subset of high-harm offenders in any given year, and if so do the individuals in that group stay constant or change substantially over time?

Our major limitation in answering these questions is a lack of access to prison records, which could enable calculations across offenders that are adjusted for time at risk in the community. Thus, our questions are all qualified by the premise of analysing people who were at large in society for at least part of each year that they come to police notice as suspects in new crimes.

Previous research on offender tracking highlights just how important it is to understand patterns of offending. Research focused on onset, prevalence, escalation, seriousness and cessation can help to identify desistance and termination opportunities that can arguably be targeted through crime control policy (Brantingham and Brantingham 2013). Chronic offenders are seen as an extreme within the general offending population and are variously characterized as habitual or “dangerous”. Yet offenders who commit a high volume of offences over extended periods of time (Blumstein et al. 1986) are not necessarily the most serious offenders, and the most serious are not necessarily the most frequent. Long-term offending research from developmental studies has focused primarily on frequency. That question is certainly important, but it leaves a gap in knowledge about short-term patterns of offending to which police can allocate resources. That gap can help criminology to consider whether there is a small group of offenders who are responsible for the majority of harm in short periods of time in any community and, if so, whether they are persistently and consistently harmful.

Tracking Offenders Over Time

Why criminals start offending, why criminals stop offending and what they do in-between have long been of interest to researchers. A notable early study that focused on life course offending is the Philadelphia Birth Cohort Study (Wolfgang et al. 1972). This research traced the developments of boys from birth until eighteen and found that 18% of the offenders could be defined as “chronic recidivists” and were responsible for more than half of the total offences committed. The “Pareto curve” concentration of the volume of crime events among a small proportion of offenders has had a substantial impact of criminal justice policy. It has also led to the identification of such concentrations in other dimensions of crime, in which a small number of units account for a large proportion of total crime event volume (Sherman 2007). For example a small proportion of all locations experience most crimes (Sherman et al. 1989), a small proportion of victims suffer the majority of crime harm (Farrell 1995; Dudfield et al. 2017) and a small proportion of all offenders have the most criminal convictions (Farrington et al. 2013).

The phenomenon of high concentration among a small part of a population is often described as “the power few” (Sherman 2007), but this phrase has been attacked by members of the public who find the phrase too complimentary to offenders who cause so much harm. More recent discussions of this group have denoted its members as the felonious few, as distinct from the “miscreant many” (Sherman et al. 2016a). In this article, we use interchangeably the terminology of “power few” (in reference to the statistical concept of a skewed distribution as a “power curve”) and the felonious few, in order to acknowledge a transition in terminology in the field of evidence-based policing. Yet whether the concentration being described is measured by offending volume or by the sum of its severity can make a big difference in the meaning of the concept. The total volume of an individual’s crimes, as recent evidence shows (Barnham et al. 2017; Bland and Ariel 2015), is not a good predictor of the total harm from an individual’s crimes.

That recent evidence comes from jurisdiction-wide offender census measures, rather than from the birth cohort studies that tended to reach the opposite conclusion. In the London birth cohort of some 400 males, for example, Farrington (1978) concluded that violent offenders tended to be more frequent or chronic than non-violent offenders. Summarizing the issues, Piquero (2000) stated that across a range of research, offenders who commit one or two crimes will be less harmful than those who continue to offend frequently. Yet the Philadelphia birth cohort study, in contrast, found that by 30 years of age, chronic offenders were no more dangerous than infrequent offenders. Multiple offending did not imply more serious offences, and increasing career length did not mean an escalation in offences (Weitekamp et al. 1995). In any case, much larger populations can reveal more granularity in differences across offenders, which could explain the different conclusions drawn from different methods. A large population of frequent offenders may display much wider variation in the total seriousness of their crime history.

Specialist Offenders and Generalist Offenders

Another dimension of criminal offending research seeks to explore categories of the “specialist offender” and the “generalist offender”. Those who offend in the same or similar category of offence over time are described as a specialist offender. “Generalist offenders” are those who are involved in a mixture of offence classes, also known as “offence switching” (Brame et al. 2004, p. 202). It is speculated by developmental criminologists that frequent offenders are more likely to be flexible (generalist) in their offending types, as opposed to less frequent offenders (Loeber and LeBlanc 1990; LeBlanc and Loeber 1998). This is supported by Chaiken and Chaiken and Chaiken’s (1982) research, which was reanalysed by Spelman (1994), finding that offenders with multiple crime types in their record committed about twice as many crimes as specialists. This led to the conclusion that the more frequent the offender, the more versatile they are across crime categories.

Escalation

Other researchers have addressed the question of whether more frequency or variety leads to escalation from less serious to more serious offences. Liu et al. (2011), for example, reviewed the 1953 birth cohort from the England and Wales Offender Index up until 1999. They found evidence to support both de-escalation being associated with ageing and escalation being associated with higher numbers of convictions. Yet whether de-escalation of seriousness applies to all offenders, or excludes a high-harm subset that could be called a felonious few, remains unclear from prior research. The lack of clarity is largely due to the small sample sizes of cohort studies, as well as the discordance between cohorts and the full population police must contend with. None of the developmental studies, to date, have examined entire populations embracing all age groups. If only for that reason alone, it is important to explore changes in distributions of offending populations within police jurisdictions over time.

Data

Northamptonshire (abbreviated as “Northants”) is a predominantly rural county in the East Midlands region of England. Its population is broadly comparable with the averages for England and Wales, with Northants being 91% white compared to an 86% white population nationally.

All crimes reported to Northamptonshire Police are input onto the NICHE records management system. Our dataset was extracted from this system to cover all crimes recorded in the 7 years between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2016. Offence classifications were derived according to Home Office Counting Rules, an official government classification system. The dataset was combined with CCHI values taken from the database available from the University of Cambridge at https://www.crim.cam.ac.uk/Research/research-tools/cambridge-crime-harm-index/view

Using Crime Harm Indices to Track Offenders

The Cambridge Crime Harm Index (CCHI) derives its weighting of each of over 700 offence categories from Sentencing Council guidelines given to magistrates and judges in the UK (Sherman et al. 2016a, b). Each weighting represents the recommended number of days in prison that a first-time offender would receive in the absence of any aggravating or mitigating factors: the so-called starting point for a sentencing decision procedure. Equivalent durations are obtained for non-custodial sentences (such as fines) by extrapolations based on the size of the fine and the minimum wage.

Recent analyses have used the CCHI to answer a variety of questions. It has, for example, examined overall offending in domestic abuse for any evidence of escalation in severity of harm inflicted against victims. Neither Bland and Ariel (2015) nor Barnham et al. (2017) found any pattern of escalation in harm of domestic crime among abusers repeatedly reported to police. Where there is evidence of re-offending from these cohorts, average crime harm scores did not exceed the first-year average crime harm score; in fact, these power few offenders, as the studies described them, showed de-escalation in the severity of their offending. Bland and Ariel (2015) and Barnham et al. (2017) both also explored intermittency and conditional probability of further frequency of events; they both found support for increasing probability of a further offence with each additional crime and decreasing intermittency between each passing event. Both also found high levels of concentration in harm levels among a proportionally small group of person-based units (dyads for Bland and Ariel, and offenders for Barnham et al.). These two studies, in particular, provide a starting point for our analytical methods in Northamptonshire.

Methods

Analytical Procedure

Crime Patterns and Offender Attribution

A “notifiable offence” (also known as a crime) was counted against a unique reference number (URN) for each crime occurrence. This provided a distinct count of crimes, preventing duplicate counts. The majority of crime occurrences had an offender record linked to them for a specific purpose (such as suspect status), and these records also had URNs to prevent duplicates. When an offender record is linked to a crime, the connection is given a description to denote why the record is linked and the description on the link. Descriptions comprising an “outcome code”, which refers to the outcome of the investigative process, were used to attribute crime records to offenders in our database. Outcome codes 1–8 (commonly referred to as “solved” or “detected” crimes) were the only codes used in this filtering. Crimes with multiple offenders were counted once for each offender.

Specialist and Generalist Offender Classifications

For the purposes of our research, we adopted the common police force definition of a “repeat offender” (more than one crime record in the dataset). Calculations were made to count the number of offence categories to which each offender had been linked. We utilized level 2 of the Home Office “Crime Tree” classification system for the purpose of grouping crime types (see Liggins 2017 for the list and example of how offenders were mapped to it). Repeat offenders with more than one crime classification attributed to them were considered “generalist”, while those with just one crime type were considered “specialist”. Offenders with only one offence were considered as “one-time” offenders. While this classification is fairly blunt, it proves to be helpful for our exploratory analysis.

Frequency, Escalation and Intermittency

We utilized descriptive statistics to establish frequencies and conditional probability calculations (P(A|B)) to analyse the relationship between the extent of generalization and future crime. Escalation was analysed by mapping sequential CCHI values and using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and appropriate post-hoc tests. Intermittency (the duration in between offences) was considered in the same way.

The Felonious Few

The CCHI weighting was the key variable used to determine the re-named power few (felonious few) offenders who accounted for the vast majority of total harm, as measured in days of imprisonment recommended by English sentencing guidelines. CCHI scores were totalled for each detected offender in the 7-year time period across all years and in each separate year. Then each offender was ranked in descending order from the highest to lowest harm scores. In each time period, we calculated the proportion of offenders accounting for a cumulative 80% of total CCHI scores.

One major departure of this use of CCHI is that it includes proactively detected offences, such as drug offences or weapons possession, against the recommendation of Sherman et al. (2016a, b). That recommendation was based on the use of CCHI as general harm indicator. From the standpoint of ranking known or suspected offenders, however, many police forces may prefer to include proactive detections as an additional indicator of a rationale for making any one person a priority for offender management and targeting.

Findings

Contextual Findings

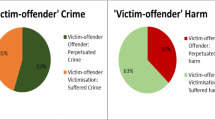

How Much of Overall Crime Was Offender-Identified (Identified to Specific Known Offenders)?

Figure 1 shows the differences between classification concentrations of reported crime volume for offences overall and for what we call “offender-identified crime” or “offender-detected crime”, i.e. offences for which at least one offender was identifiable. With violence against the person offences, for example, there was a greater percentage of the offender identified crime (28%), compared to the percentage of overall reported crime (22.1%). Theft offences made up the highest percentage of overall crimes reported (48.9%) and the highest percentage of offender identified crimes.

A different picture was observed in terms of crime harm, as shown in Fig. 2. Crime classifications with lower rates of offender identification were less represented in the distribution of crime harm by offence categories.

Repeat and One-Time Offenders Over Time

Of the 39,545 unique offenders named in our dataset, 14,548 (36.8%) committed more than one offence; the remainder were one-time offenders (within our time period). Between 2010 and 2016, almost three-quarters of all offender-identified crimes were committed by a repeat offender, a pattern that remained relatively stable year on year (as shown in Fig. 3).

Specialist and Generalist Offenders

As shown in Fig. 4, no offender offended in all nine crime categories, with the most being eight categories. Specialist offenders (one category only) represented 31.8% of all repeat offenders and 19.2% of crimes committed by repeat offenders. Generalists with just two crime categories represented 41.6% of repeat offenders and accounted for a further 29.6% of the total crimes committed by repeat offenders. Smaller percentages of crime and associated offences were found as the number of categories increased.

Repeat Offenders and Harm

Repeat offenders accounted for 68.7% of all offender-identified crime harm in the dataset, at a level which was largely consistent throughout each of the 7 years analysed. Among repeat offenders, “specialists” accounted for 22.5% of harm, slightly more than their proportional contribution to volume (shown in Fig. 4) but considerably less than the proportion of overall repeat offenders that they make up. Figure 5 shows that, as with volume of crime, the more “generalist” an offender is (i.e. the more types of crime they were linked to), the greater the proportional difference of their contribution to harm committed by repeat offenders.

Our findings also show that the more diverse an offender’s behaviour in terms of the range of crimes committed, the more harmful they were. An ANOVA test of the results shown in Fig. 6 indicated a statistically significant variance in the sequence (F (7, 14,540) = 102.63, p < 0.001). Tukey’s honestly significantly difference (HSD) post-hoc test indicated that 26 of the 28 possible combinations inferred by this figure were statistically significant.

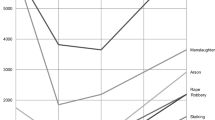

Offending Frequency, Escalation and Intermittency

Figure 7 shows that the initial probability of a first time identified offender being linked to a second offence was 37%. The conditional probability of further attributions of crimes to offenders rose with each subsequent offence up until the thirteenth event, when the risk level flattened. After that point, conditional probability ranged between 88 and 92%. On the thirtieth event, it becomes 99% likely to report a thirty-first event. The maximum number of offences identified for any one offender was 138 offences over the 7-year period. After the thirtieth event, the numbers of offenders at those levels of linked crimes become very low. Nonetheless, probability scores continue to range mostly between 90 and 99%. After just twelve events, all subsequent probabilities exceed 88%, which indicates that chronic offending is highly probable to remain chronic.

Intermittency

A related point about future offending is that with each additional offence, the next offence occurs with increasing speed after the last offence. In the criminological concept of “intermittency”, the crime-free time in between crime declines.

Figure 8 shows that on average, there were 333 days between the reported first and second offence. Between events 2 and 3, this time period dropped to 256 days. At the 36th event, intermittency dropped to its lowest average of 27 days. A one-way ANOVA was performed on the first ten pairings for number of days between offences and showed a significant difference between the groups (F [8, 41,491] = 232.7, p < .001). Post-hoc comparisons were undertaken using the Tukey HSD test, which indicated the most pair relationships were significantly different (see Liggins 2017: Table 3).

Escalation

While future offending becomes more likely and sooner as the number of prior offences increases across each offender’s career (on average) within our 7-year window, it does not become more harmful. To the contrary, recidivism becomes generally less harmful with repeated offending, as Fig. 9 shows.

For all first-time offences, Fig. 9 shows an average crime harm score of 74 days of recommended imprisonment (n = 39,545 first-time offences). This was the highest average crime harm score across the chronological sequence of offending. The trend for average crime harm scores appears to mostly show a downward trend with peaks and troughs but no average crime harm score higher than the first reported offence. While the fluctuations become very wide after the 12th offence, the drop from an average of 74 at offence #1 to 36 at offence #12 is a steady drop of over 50% in CCHI scores. While there will be individual exceptions, the best bet across all offenders under management in that time period was that future harm levels would drop. That would include the felonious few, whose participation may persist well into the sequence shown in Fig. 9.

The “Felonious (Power) Few”

Figure 10 shows that for the 7 years combined, 20% of offender identified harm came from 0.6% of unique offenders, 50% of offender identified harm came from 2.7% of unique offenders and 80% came from 7.6% of unique offenders. Of those who were responsible for 80% of the offender-identified harm, this equated to 5.2% (17,033) of all reported crime offences and 31.7% of all crime harm (i.e. including those offences where an offender had not been attributed). Compared to offender identified crime, 20% of crime volume came from 10.3% of known offenders, 50% came from 21.2% of offenders and 80% came from 54.2% of identified offenders.

Figure 11 shows the total percentage of all felonious few offenders (producing 80% of crime harm) broken down between repeat and one-time offenders. This shows that the latter make up a smaller proportion of power few offenders and that typically there were approximately two repeat offenders in the power few for every one-time offender.

The contribution of individual offenders to overall offender-attributed crime harm had broadly the same ratio of 2:1 in favour of repeat offenders, with the notable exception of 2015, as shown in Fig. 12.

Tracking the list of the “felonious power few” cohort responsible for 80% of offender-identified harm in 2010 (n = 610) into subsequent years, we found a very high rate of attrition from the first year onward. As Fig. 13 shows, by 2011 just 3.4% of the 2010 felonious power few offenders remained in the most 80% of CCHI cohort calculated for the next calendar year, and more than three-quarters of that 2010 felonious few had no subsequent arrest in 2011. This pattern continued in every subsequent year up to 2016, by which time less than 1% of 2010’s power few remained among the most harmful offenders and almost nine in 10 had had no further detected offences.

What this analysis cannot tell us, however, is what proportion of the 2010 felonious few was in prison for all of 2011 or all or any part of 2012, 2013 or any year through 2016. Theoretically, the higher the CCHI value attributed to an identified offender in 2010, the more likely they were to be convicted and sentenced to prison. By definition, the higher the CCHI value among convicted offenders, the longer any prison sentences would be. Yet from a policing standpoint, it does not matter whether these offenders have been removed from the population. What matters is whether there is a means by which police can track the whereabouts of any recent list of a felonious few and specifically whether they are in prison or not.

Conclusions

As previous research has set out, there are weaknesses in the continued use of aggregated crime volumes as the sole means for targeting police resources, whether by areas, victims or offenders (Sherman et al. 2016a, b). Our findings demonstrate that the use of a severity metric such as the CCHI can provide important additional information for targeting police investments.

Repeat and One-Time Offenders

In our data, repeat offenders made up just over a third of offenders in a 7-year period but accounted for just over two thirds of crime harm. Yet our findings illustrate that one-time offenders also commit very high-harm crimes and can feature prominently in the subset of the power (or felonious) few. This highlights that public policy would just benefit from understanding not only chronic offenders but also any opportune intervention points for one-time offenders—such as predictors of domestic homicide by people with no prior offending records.

The major obstacle to predicting single-offence high harm, of course, is how a police agency might predict which individuals may commit such crimes, when they have no prior (or recent) criminal record. It is probable that some of these offenders do have prior records but outside the scope of our dataset. It is possible too that other police databases contain information on these individuals. They may be suspects in crimes, victims, subject to intelligence or stop and search records. They may have committed driving offences of having a record of being missing or absent. There may also be an extent of “lapse and relapse” (Laub and Sampson 2001). No matter how this might be done, this study confirms the importance of looking beyond any list of just “the usual suspects”.

Generalists and Specialists

We found that the majority of repeat offenders in a 7-year period were “generalists”, with at least two different categories of crime attributed to them. Moreover, these offenders had a higher frequency of crimes, providing more opportunities for prediction and intervention. Our evidence demonstrates a simple story—the more types of crime an offender engages in, the higher their overall crime count and contribution to overall crime harm. Simple though it may be, this finding has had little previous empirical coverage in respect of crime harm. It suggests a reasonably compelling case for the inclusion of some measure of offence diversification as part of risk assessment and offender management processes.

Who to Manage and for How Long?

Our analysis supported the notion found in other research (Bland and Ariel 2015; Barnham et al. 2017) that with each event, the next event becomes more likely (Fig. 7). While the first event shows a 37% likelihood of a second event, by the time it becomes the twelfth event, conditional probability exceeds 88%. Chronic offending is likely to become even more chronic given time, and the time in between crimes in particular will decrease with further offences. However, we found strong evidence that the severity of these additional crimes declines over time. There may be many possible reasons for this pattern, which seems to be a major piece of evidence in the study of desistance (Laub and Sampson 2001). The evidence seems to have important policy implications for the lifecycle of offender management by police or probation.

The question of offender management time is a critical resource issue, regardless of who does it (police, probation, or even prison). While we found that although there was a proportionally small group of offenders contributing a large proportion of harm in each year of our data, year-to-year turnover rate was almost 100%. This fits with our evidence showing de-escalation of harm, even with increasing frequency of offences. Exactly which offenders remain in the community, but drop substantially in CCHI levels, is an important question for further research to answer.

At the same time, the 0.8% of identified offenders we found to have persistent high harm tendencies over 7 years also merit further investigation. These are the offenders that are likely described by Blumstein et al. (1986) as career criminals or chronic offenders. Unlike almost all of the felonious few, these “very very” few offenders commit a high frequency of serious offences over extended periods of time. That means, among other things, that they must be able to spend some time each year out of prison, possibly by mixing low harm offences with higher harm offences. It is these offenders who could be used for accurate prediction models of very high harm and long-term chronic offenders.

Use of long-term, multi-year data in this way can help police forces to make better decisions through the use of evidence. Doing so requires a large cultural shift from current police analysis models, which largely focus on short periods of time. Rarely are such analyses allowed to go into the depths of detail or methods required to provide insight in targeting offenders. The present analysis could be profitably undertaken in every police force in England and Wales and refreshed annually or even more frequently.

With such a small number of felonious few offenders inflicting the vast majority of crime harm, our analysis suggests that offending is decidedly segmented in Northamptonshire. That is particularly the case for the most persistent felonious few chronic offenders who committed a high frequency of harmful offences over a lengthy period of time. It is also true for the single event offenders who commit significantly harmful offences for their first offence. This segmentation, and the comparative differences in harm presented by specialist and generalist repeat offenders, could assist police forces everywhere in reframing offender management and tracking.

References

Barnham, L., Barnes, G. C., & Sherman, L. W. (2017). Targeting escalation of intimate partner violence: evidence from 52,000 offenders. Cambridge Journal of Evidence Based Policing, 1, 116–142.

Bland, M., & Ariel, B. (2015). Targeting escalation in reported domestic abuse: evidence from 36,000 callouts. International Criminal Justice Review, 25(1), 30–53.

Blumstein, A., Cohen, J., Roth, J. A., & Visher, C. A. (1986). Criminal careers and career criminals: volume I. Washington D.C: National Academy Press.

Brame, R., Paternoster, R., Bushway, S., & D. (2004). Criminal offending frequency and offence switching. J Contemp Crim Justice, 20(1), 201–214.

Brantingham, P., & Brantingham, P. (2013). Crime pattern theory. In R. Wortley (Ed.), Environmental criminology and crime analysis (pp. 78–94). London: Routledge.

Chaiken, J. M., & Chaiken, M. R. (1982). Varieties of criminal behaviour. Santa Monica: Rand Corporation.

Dudfield, G., Angel, A., Sherman, L. W., & Torrence, S. (2017). The “power curve” of victim harm: targeting the distribution of crime harm index values across all victims and repeat victims over 1 year. Cambridge Journal of Evidence Based Policing, 1, 38–58.

Farrell, G. (1995). Preventing repeat victimisation. In M. Tonry (Ed.), Building a safer society. Crime and justice. 19 (pp. 469–534). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Farrington, D. P. (1973). Self-reports of deviant behaviour: predictive and stable? The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 64(1), 99–110.

Farrington, D. P. (1978). The family backgrounds of aggressive youth. In L. B. Hersov (Ed.), Aggression and antisocial behaviour in childhood and adolescence (pp. 73–93). Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Farrington, D. P., Piquero, A. R., & Jennings, W. G. (2013). Offending from childhood to late middle age. London: Springer.

Jennings, W. G., Loeber, R., Pardini, D. A., Piquero, A. R., & Farrington, D. P. (2016). Offending from childhood to young adulthood: recent results from the Pittsburgh Youth Study. London: Springer.

Laub, J. H., & Sampson, R. J. (2001). Understanding desistance from crime. In M. Tonry (Ed.), Crime and justice: a review of the research (pp. 1–69). Chicago: Chicago Press.

LeBlanc, M., & Loeber, R. (1998). Developmental criminology updated. Crime and Justice: An Annual Review of Research, 23, 115–198.

Liggins, A. (2017). Tracking the most serious offenders in Northamptonshire: continuity and replacement over time in the power few. Thesis submitted for the MSt in applied criminology and police management, Institute of Criminology, University of Cambridge.

Liu, J., Francis, B., & Soothill, K. (2011). A longitudinal study of escalation in crime seriousness. J Quant Criminol, 27, 175.

Loeber, R., & LeBlanc, M. (1990). Toward a developmental criminology. Crime and Justice: An Annual Review of Research, 12, 375–473.

Loeber, R., Hoeve, M., Slot, N. W., & Van Der Laan, P. H. (2012). Persisters and desisters in crime from adolescence into adulthood. Surrey: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

Monahan, K. C., & Piquero, A. R. (2009). Investigating the longitudinal relation between offending frequency and offending variety. Crim Justice Behav, 36(7), 653–673.

Piquero, A. R. (2000). Assessing the relationships between gender, chronicity, seriousness, and offence skewness in criminal offending. J Crim Just, 28(2), 103–115.

Reiss, A. J., & Roth, J. A. (1993). Understanding and preventing violence. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Sherman, L. W. (2007). The power few: experimental criminology and the reduction of harm. J Exp Criminol, 3(4), 299–321.

Sherman, L. W. (2013). The rise of evidence-based policing: targeting, testing, and tracking. Crime Justice, 42(1), 377–451.

Sherman, L., Gartin, P. R., & Buerger, M. E. (1989). Hot spots of predatory crime: routine activities and the criminology of place. Criminology, 27, 27–55.

Sherman, L. W., Bland, M., House, P., & Strang, H. (2016a). Targeting family violence reported to Western Australia Police, 2010–2015: the felonious few vs. the miscreant many. Perth: Western Australia Police.

Sherman, L. W., Neyroud, P., & Neyroud, E. (2016b). Measuring total harm from crime based on sentencing guidelines. Policing, 10(3), 171–183.

Spelman, W. (1994). Criminal incapacitation. New York: Plenum Press.

Weitekamp, E. G. M., Kerner, H. J., Schindler, V., & Schubert, A. (1995). On the “dangerousness” of chronic/habitual offenders: a re-analysis of the 1945 Philadelphia birth cohort data. Studies on Crime and Crime Prevention, 4(2), 159–175.

Wolfgang, M. E., Figlio, R. M., & Sellin, T. (1972). Delinquency in a birth cohort. Chicago: University Chicago Press.

Wolfgang, M. E., Thornberry, T. P., & Figlio, R. M. (1987). Studies in crime and justice. In From boy to man, from delinquency to crime. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Northamptonshire Police for matching the College of Policing support from the Policing Knowledge Fund of 2015–2017 to pay for the first author’s enrolment in the University of Cambridge Police Executive Programme’s M.St. course in applied criminology and police management at the Institute of Criminology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Liggins, A., Ratcliffe, J.H. & Bland, M. Targeting the Most Harmful Offenders for an English Police Agency: Continuity and Change of Membership in the “Felonious Few”. Camb J Evid Based Polic 3, 80–96 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41887-019-00039-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41887-019-00039-7