Abstract

Research Question

What was the nature of kidnappings in London during a fairly recent 5-year period in the kinds of victims, offenders, motives, types of violence used and levels of injury?

Data

We analyse 924 reports of kidnap crimes recorded by the Metropolitan Police Service between 1 April 2006 and 31 March 2011. These data included free text information drawn from case notes.

Methods

We establish mutually exclusive categories of kidnappings by codifying all crime records, after examining case notes and populated fields from the Metropolitan Police’s crime recording system. Descriptive statistics are used to portray the patterns and nature of these crimes.

Findings

The application of a typology of mutually exclusive categories for these kidnappings shows that gangland/criminal/drugs-related cases comprised 40.5% of all kidnappings. Another 21% of all kidnaps were domestic or familial, including honour killings. Just over 10% were incidental to ‘acquisitive’ crimes such as car-jacking, whilst 8% were sexually motivated. Only 6% were categorised as traditional ransom kidnappings. About 4% were categorised into a purely violent category, whilst 3% were categorised as international/political.

Conclusions

The investigative and preventive implications of these many social worlds mapped out by this typology are substantial. Each social context may require investigators to possess expertise in the specific social world of kidnapping, as distinct from what might be called expertise in ‘kidnaps’ per se. Investigations and prevention might be re-engineered around targeted intelligence from these diverse social contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Kidnapping is an internationally prevalent crime. The global costs associated with kidnapping have long been known to run into the hundreds of millions of pounds, and the crime is a major concern for multinational businesses (Briggs 2001). Yet there is little assurance that patterns of kidnapping in one city or country can predict patterns of kidnapping in other places or times. The importance of understanding the form of kidnapping takes across London is substantial, yet it had not been systematically examined before the present study was undertaken in 2011–2012.

Previous research in other settings has produced typologies of kidnap, yet not without substantial bias in their estimates. For example, Alix (1978) bases his entire typology study on reports of kidnap taken from the New York Times. Alix therefore only had at his disposal reports of kidnap deemed interesting enough by editors and reporters to publish, and he has little to no insight into the reporting procedures of the police at the time. His typology of kidnap is biased by the very nature of his source before he undertakes any form of analysis independently of that which the New York Times has already performed in selecting a report of kidnap for publication in a major daily international broadsheet.

The approach adopted by Concannon et al. (2008) acknowledges the deficiencies in Alix’s primary source, but it suffers a different kind of bias. Limited to instances of kidnap that have survived the Supreme Court appeals process, Concannon focusses on substantive legal issues in offences of kidnap. This is not without value, for it provides Concannon with concrete parameters for defining a kidnap and to which she is able to apply a complicated set of qualifying criteria. Yet as the source of an empirically reliable estimate of the nature and distribution of characteristics of all kidnaps, her data are potentially even more biased than an estimate based on newspaper reports.

Both Alix and Concannon focus on offences of kidnap that have progressed well beyond the initial reporting phase. Both then attempt to overlay a typology of kidnap. However, in approaching kidnap at this late stage in both the investigative and judicial processes, there is an implicit assumption that there exists a ‘starting point’ at which a kidnap has been committed and no recognition of the various factors that have deemed this to be the case. Whilst the remit of both Alix and Concannon is to formulate a typology of kidnaps, there appears to be no questioning of what defines kidnap prior to their respective ‘starting points’.

Research Question

The research question is what characteristics and patterns can be discerned in London that could confirm or contradict the characteristics found by tracking studies of kidnapping in other communities. Firstly, we are concerned with an examination of the individual characteristics of victims and suspects involved in each separate offence as they were recorded: sex, age and ethnicity. Secondly, we are interested in the levels and kind of harm inflicted by these crimes: the property stolen during kidnap offences, the level of violence used, the extent of the injuries to victims and the relationships between victims and offenders. Thirdly, we seek to compare the London findings with evidence from tracking previous kidnap samples (see Alix 1978; Concannon et al. 2008), in order to assess the need for different typologies in London.

Data

At the time we collected our data, allegations of kidnapping reported to the Metropolitan Police were recorded on the computerised Crime Reporting Information System, of ‘CRIS’, used by frontline officers, detectives and civilian staff to keep an ongoing log of investigations. Using CRIS as a source of data has both disadvantages and advantages. The disadvantage is that the CRIS records have not been vetted by crime registrars and full classified for official crime statistics.

The advantages of using data from the very initial stages of crime recording, however, are numerous. CRIS data provide the most comprehensive picture of crimes initially called ‘kidnap’ when reported, and which drive what police officers within the Metropolitan Police Service must do about those reports on a daily basis. That is because CRIS charts the first contact between victims/complainants and police. Whilst later investigation may lead to a reclassification of some or many reports, CRIS data provided the initial basis for managing police priorities and resources.

All crime records in CRIS were required to conform to classifications set out within Home Office Counting Rules—the official government crime definition catalogue. In examining any aspect of a specific crime type, the classificatory framework is a good starting point and kidnapping is no different. In fact, the subject of classification of kidnap was, at the time, more complex than other crime types. The offence of kidnap was (and remains) a common law offence—meaning it historically emanated from courts rather than act of parliament. Along with homicide, kidnap remains the last high-harm offence which has yet to be codified into statute. The lack of a codified definition has led to some confusion in terms of a working classification for kidnap. At the time our data were recorded, the Home Office (2011) defined kidnap as:

Unlawfully seizing and carrying away a person by force or fraud, or seizing and detaining a person against his or her will with an intent to carry that person away at a later time.

The Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO then, now the National Police Chief’s Council), however, used a different definition of kidnap in the ACPO (2002) Kidnap Manual:

the abduction or holding of a hostage with the intention of extorting money or other valuables, or securing some substantial concession for the hostage’s safe return.

Our data for this study used the Home Office classification as recorded by the Metropolitan Police at the time, thereby choosing the broader of the two definitions.Footnote 1 The national crime recording standard (NCRS) was instituted in April 2002 and was intended to bring consistency across the country in recording crime (Maguire 2007). The standard introduced to police across England and Wales included the universal adoption of a reporting system based upon a prima facie process as opposed to an evidence-based reporting system. What this meant in practical terms was that individual members of the public reporting crime would be taken at face value and the report should reflect this position as opposed to the police being able to quash a report because they think it could not possibly have occurred or the reporting was mischievous or mistaken.

The NCRS breaks down specific crimes into subcategories assigning each a category code. The table below shows how the Home Office breaks down the crime of kidnapping into sun-categories.

036/01 Kidnap (Common Law Interpretation)

036/02 Hijack

036/03 False imprisonment (Common Law Interpretation)

036/04 Detaining or Threatening to Kill or Injure a Hostage (Taking of Hostages Act 1982 Section 1)

The dataset used in this analysis is only those crime allegations confirmed as 036/01-kidnap. It was intended to include any allegations under category 036/04; however, following interrogation of the system, it was found that this category has not to date had any crime allegation recorded against it.

We utilised a variety of search prompts to isolate the pertinent features of kidnap offences. The system was interrogated retrospectively to extract all recorded offences committed from April 2006 through March 2011. This extraction provided 5 years of data for a total of 924 allegedly completed crimes (with attempted kidnaps deleted), with data on both the victims and the suspects for each report.

Methods

In order to classify the variables of interest in the analysis and to assess a possible typology, we reviewed the free text entries of every crime record. We used a pre-determined coding framework based on the previous typologies already discussed. We applied descriptive analytical techniques to variables for age, gender and ethnicity and collated details of property from the relevant fields for the same purpose. The use of violence in the commission of the offence was ascertained by use of the ‘features’ field in which officers can assign information to the crime record based on a pre-determined list of options (of which violence was one option).

Findings

Victim Characteristics

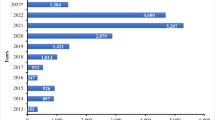

London kidnap victims in 2006–2011 were mostly males, but one-third were females. Their ethnicity had no majority, with 34% white European, 29% Afro-Caribbean, 25% unknown and 6% Asian. The victims’ age distribution is displayed in Fig. 1, which shows 48% under age 20 and only 8% over 40.

Among the victims in the 11–20 age bands, three-quarters (76%) were aged 16–20. That suggests that they are perhaps more likely to be involved in criminal activity, as distinct from being subjects of parental custody disputes (see “Typology” below).

Suspect Characteristics

Previous studies had found that kidnap offenders were mostly males, and this study was no exception. Yang et al. (2007) found that in Taiwan, kidnap offences were carried out mostly by males who were in their early to mid-20s. In the UK, Soothill et al. (2007) found that of 7587 adult offenders convicted of kidnap offences between 1979 and 2001, only 545 (7%) were females. The position in London during 2006–2011 was identical, at 7% of suspects being female—a substantial difference from the 33% of victims who were females.

The ethnicity of suspects also differed substantially from that of victims. Over half of the suspects (52%) were classified as Afro-Caribbean, with 21% white European, 19% ‘Asian’ and 3% Chinese/Japanese.

Figure 2 shows that the age of the suspects is substantially older than the age of the victims and that the mean number of suspects per case is far larger than the mean number of victims. The age of all suspects combined peaks between 21 and 30 years, yet the second-largest category is suspects between age 11 and age 20. The latter finding could have been a harbinger of the ‘County Lines’ exploitation of younger people in carrying out crimes planned by older offenders.

Violence Used

It would appear at first glance that kidnap offending in London during the period analysed was almost exclusively an acquisitive crime and appeared not to have elements of political violence within it. Using the classificatory device modelled by Turner (1998), all of what is known about the property aspect of kidnap offending suggests that they sit in ‘type 1’ described as ‘money no politics’.

However, we must emphasise that the property field was only completed in 523 of the 924 crime reports in our dataset. There are a number of possible explanations for this. One is that property or cash was not a motivating factor at all, and therefore, it did not feature on the property field of the crime report; the motivation could simply be revenge, domestic conflicts or sexual exploitation of the victim. Another explanation is that the property field was simply not filled in by the officer at the time of filing the report, i.e. user error. The format the universal crime report takes does not allow for other motivational reasons for the kidnap to be separately identified—making it impossible to ascertain whether, for instance, the motivation for the kidnap offence was political or not.

Figure 3 shows the full breakdown of violence classifications described in the dataset.

Property Stolen

We found that 93% of the property stolen in kidnap crimes was valued at less than £500. Figure 4 shows the breakdown of property types stolen.

Injury Suffered by Victim

We found that almost half (46%) of all kidnaps involved some kind of injury, albeit most of them were minor in nature. Serious injuries occurred in just 6% of cases. Figure 5 shows the full breakdown of injury types.

Relationship Between Victim and Suspect

We found that familial or friendship/acquaintance relationships accounted for almost three-quarters of kidnap crimes (74%). Domestic abuse featured in a further 15%. Business associates were only 3% of the relationships, and criminal associates were only 1% (see Surtees (2011) for the full breakdown).

Typology

Out of the 924 crimes within the dataset, we identified nine distinct types of kidnap. This process does have within it a degree of subjectivity. Yet as Concannon et al. (2008) suggest, it also yields both fruitful and previously unexplored offence descriptions at the first reporting stage. Offence typologies in general are not necessarily mutually exclusive, in the sense that one kidnap can be or should be isolated as fitting only into either one category or another. Indeed, several of the offence types are closely linked and a particular instance could be said to fit into one or more of the designated descriptions.

That said, it should be noted that in this analysis, each crime was assigned to just one category. In the ransom category, for example all of those crimes that appeared to be straightforward ransom demands without obvious gang or drugs links were included. In contrast, where it was obvious that gang or drugs business lay behind the kidnap and subsequent ransom demands, the crimes were assigned to the crime/gang/drugs category. A future examination of these data might adopt a more sophisticated system to account for the complexity apparent in many of these reports. This approach of mutually exclusive classifications allows the analysis to reflect the motivation and rationale for each individual offence. Table 1 shows the full breakdown of our categories together with their respective frequencies.

The application of this mutually exclusive typology, grounded in the empirical patterns found in London, shows that the ‘gangland/drugs’ kidnaps account for 2 out of every 5 of these crimes. Domestic and honour crimes yield another 1 out of 5. Property and sexual exploitation take another 1 out of 5, with classic ‘ransom demand’ kidnaps trailing the others at 6% of all cases.

Conclusions

Our dataset—5 years of kidnap crimes from the Metropolitan Police Service—offered us a unique opportunity, with access to a level of investigative detail not previously available to academic researchers. Consequently, we are able to draw several important descriptive conclusions about the 924 kidnaps in the period we analysed. (1) The crime was predominantly committed by male suspects on male victims, but also with 33% female victims. (2) Suspects were more frequently African-Caribbean than any other ethnicity, but (3) the same was not true for victims, which were more evenly distributed between white Europeans, African-Caribbeans and Asians. (4) Both victims and offenders were predominantly below the age of 30, and above the age of 15. (5) Only a small proportion of victims received a serious injury.

Using our London-based, mutually exclusive categories to classify all 924 crimes, we are able to target concentrations of kidnapping in a new way. To restate the summary of Table 1 above, by far the largest category of kidnap was the gangland/criminal/drugs-related kidnapping. This amounted to over 40.5% of all kidnappings recorded in London in those 5 years. Approximately, 18% of all kidnaps were domestic or familial. Just over 10% were acquisitive and 8% were sexually motivated. Six percent were categorised as ransom kidnappings with just over 3% categorised as international/political. Approximately 3% of all recorded kidnappings were categorised in this study as honour based, and 4% were categorised into a purely violent category. (The remaining 9.5% that were categorised as miscellaneous most falling into the false reporting category, but due to the crime reporting standards had to remain classified as a crime.)

These findings reveal the very different worlds in which the legal definition of kidnap occurs in London. The gangland kidnaps seem to be linked to regional or even national networks of drug dealers, and their proportion may have risen higher over the succeeding decade. The domestic/honour kidnaps seem likely to come from a completely different world of generational or cultural conflicts over roles of women and parental authority—although some may come from marital or child custody disputes of any culture. Taking people as incidental to taking property, such as in carjacks, may be most challenging to the traditional view of the kidnap being about the kidnapped—rather than their property. The traditional cinematic version of kidnaps—motivated by big ransom—is one of the very smallest categories.

The investigative and preventive implications of the distribution of cases in this new typology are substantial. They both require a range of expertise in the different social worlds of kidnapping and not what might be called expertise in ‘kidnaps’ per se. From an investigative standpoint, that conclusion suggests a hub-and-spoke system of assigning kidnap investigations based on the typology. For example:

The gangland kidnaps could be assigned to London-wide investigative units with good intelligence (qualitative or quantitative) on the gang world of county lines.

The domestic/honour kidnaps, in contrast, might be assigned to a safeguarding unit in one of the twelve police regions of the Metropolis—officers whose job is to protect vulnerable people or those at high risk of high-harm victimisation, let alone couples in custody battles for young children.

The sexual assault cases could be linked to either of the social worlds just described, or they could be linked to a world of sexual predators; more research is clearly needed in that category.

Finally, the kidnap-for-ransom cases could actually go to a London-wide unit that specialises in offenders who commit such crimes, and who may be going in and out of prison—something a specialist ‘ransom unit’ could track in its pool of likely repeat kidnappers, if such people can be found to exist (by more research as well).

The preventive implications would have to be developed in the same diverse social worlds, one world at a time. Yet the need for further research to target prevention strategies would be even greater than any of the other research issues raised by this study. In order to avoid unnecessary intrusion into people’s lives, the targeting of prevention efforts should have as little error (false positives) as possible. Yet once someone has been the victim of a kidnap or an attempt, the research could show a very high continuing probability of a repeat kidnapping—possibly by the same family members, or their relatives. It is on such questions that investigations and prevention can merge, with the same personnel and the same intelligence or digital data.

The final implication of this study is that it shows what a computer programme could do with an automated daily report. That report, based on the most recent 5 years of kidnap data, could generate:

A target list of kidnappers who have just been released from prison.

A rank ordering of kidnap victims who have been revictimised by any offence.

A list of members of different gang networks who have been injured, with linkages analysis to their closest co-offenders and arch-enemies.

Other assignments based on tested, targeted practice.

Tracking reports on whether previous assignments were completed.

This study was done with much manual effort, as well as with computer support. With more digital capacity, police departments anywhere could get more timely and accurate intelligence and respond with effective tactics by the people with the most appropriate skills or knowledge—another decision that could be partially automated with digital access to skills across a 50,000-employee organisation. Kidnapping in the twenty-first century can certainly benefit from more twenty-first-century tools.

Notes

We used only crimes with the Home Office code 036/01 Kidnap (Common Law Interpretation).

References

Alix, E. K. (1978). Ransom kidnapping in America: 1874–1974 the creation of a capital crime. London: Southern Illinois University Press.

Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO) (2002). Manuel of guidance for kidnap investigations. (restricted) www.acpo.police.

Briggs, R. (2001). The kidnapping business. London: The Foreign Policy Centre.

Concannon, D. M., Fain, B., & Fain, D. (2008). Kidnapping: an investigators guide to profiling. London: Academic Press.

Home Office (2011). Classification & Counting Rules. http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk.

Maguire, M. (2007). Crime data and statistics. In Maguire M, Morgan R, Reiner R (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of criminology, Fourth Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Soothill, K., Francis, B., & Ackerley, E. (2007). Kidnapping: a criminal profile of persons convicted 1979-2001. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 25, 69–84.

Surtees, K. (2011). ‘Kidnapping in London: offenders, victims and motivation.’ MSt Thesis in Applied Criminology and Police Management, University of Cambridge.

Turner, M. (1998). Kidnapping and politics. International Journal of the Sociology of Law, 26, 145–160.

Yang, S., Wu, B., & Huang, S. (2007). Kidnapping in Taiwan: the significance of geographic proximity, improvisation, and fluidity. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 51(3).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support of the Metropolitan Police Service for the first author to take the Cambridge M.St. course in applied criminology and police management, for which the research was done as the thesis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Surtees, K., Tankebe, J. & Bland, M. Tracking Kidnappings in London: Offenders, Victims and Motives. Camb J Evid Based Polic 3, 97–108 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41887-019-00036-w

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41887-019-00036-w