Abstract

Research Question

Does analysis of intimate partner violence (IPV) among Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal couples in the Northern Territory (NT), Australia, reveal any predictable escalation in frequency or severity of harm over a 4-year observation period?

Data

We examined all 61,796 incidents of IPV recorded by the NT Police for 23,104 unique couples (‘dyads’), over the 5-year period from 1 January 2010 to 31 December 2014. For purposes of analysing changes over time in frequency and harm, we used standardised observation periods (generally 4 years) from first incident to end of observations.

Methods

Each IPV incident was re-classified by crime type using the penal code of England and Wales, in order to measure the severity of harm in NT with the Cambridge Crime Harm Index (CHI). The CHI scores were used to test for patterns of concentration and escalation, based on the total days of recommended imprisonment for each offence type, summed across all offences of that type for the entire sample.

Findings

The findings were sharply split between Aboriginal and White dyads. While there was no evidence of escalation in either frequency or severity of IPV incidents in the White dyads, there was substantial evidence of escalation among Aboriginal offenders with three or more incidents in a 4-year period.

Less than 2% of White offenders (2 of 111) had three or more incidents in 4 years, compared to 32.4% of Aboriginals (N = 105 out of 355 offenders).

For those couples of both races known by police to have two or more incidents, there was a strong pattern of escalation in the frequency and seriousness of offending for up to 20 incidents over 4 years. While 66% of couples had desisted by year 3 with no further reports that year or the next, among the 34% of couples (N = 3621) persisting into year 3 the probability of a new incident by year 4 was 99.9%. Similarly, the time between incidents for these repeaters declined with each new incident, indicating an increase in frequency.

Severity of harm also rose with repeated incidents, from 0.6 of expected Cambridge CHI value per dyad among couples with 1 to 5 incidents over 4 years to 3.82 times higher than expected value per dyad among those couples observed to have 16–20 incidents over 4 years—six times more harm among couples (almost entirely Aboriginals) with the highest frequency of incidents than among couples with the lowest frequency.

Conclusions

This targeting analysis confirms other research that shows no escalation in frequency or severity of domestic abuse among predominantly White European populations. Yet it also provides the first systematic test of the escalation hypothesis about IPV reported to police among Australian Aboriginal dyads. That evidence provides a strong basis in evidence for developing a two-track policy for policing IPV in Australian areas with substantial Indigenous populations. Track 1 would serve dyads (of either race) presenting for the first or second time, for whom a light touch may generally be sufficient. Yet any couple known to have had two or more prior offences could receive a far more intensive strategic investment, including the testing of new strategies for prevention of escalation in harm or frequency of IPV. Yet because this pattern of escalation is found only in a minority of Aboriginal dyads, it is important to base policy on evidence-based targeting of dyads with prior occurrences rather than race.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It is widely believed across the NT Police that escalation in severity of harm and frequency is a common feature of couples experiencing interpersonal violence (IPV) (NT Police 2014) and that this is particularly the case in Aboriginal communities or couples. That view was recently contradicted by evidence from the predominantly White European population of Suffolk County, UK (see Bland and Ariel 2015) that in domestic abuse police callouts escalation in severity is rare, as is escalation in frequency of calls, except among the most chronic cases. Yet in that analysis, the couples (or ‘dyads’ of victim and offender, defined here as unique opposite-sex intimate partners and ex-partners in a spousal, romantic or sexual relationship) included parent-child relationships, siblings and other kinds of family violence along with IPV. The Bland and Ariel (2015) Suffolk police analysis also used observation periods that were not held constant, so that each dyad had different periods of time at risk for repeat incidents. While the Suffolk analysis was a major advance in the precision of evidence on domestic abuse, it leaves unanswered two key questions: whether the same conclusions would be reached if (1) dyads observed were restricted to intimate partners, and if (2) each dyad had an equal time period for further observation and recording of police contacts after the first case was reported to police.

This paper fills those research gaps in relation to the Northern Territory of Australia with a descriptive analysis of the characteristics, frequency and severity of IPV incidents reported to the NT Police, together with patterns of escalation and desistance. These incidents overwhelmingly involve Aboriginal victims and offenders.

The Northern Territory Context

The NT is Australia’s northern-most jurisdiction with a landmass of 1.3 million square kilometres and a population of about 240,000. Aboriginal people comprise 32% of this population and 13% of the total Australian Indigenous population (ABS 2011). Across Australia, Indigenous people constitute 2.6% of the Australian population. Most of the NT Aboriginal population (79%) is spread across numerous small remote communities (ABS 2011).

The living conditions in many of these communities more closely resemble those in the third world rather than those of wider Australia. These circumstances, including the particular challenges of remoteness and isolation, pose special problems for police response and crime prevention. Just as the population is widely dispersed, so are the police, often with distances of hundreds of kilometres between police stations. These vast distances, economic costs and time delays preclude many Aboriginal people from access to immediate policing services. Recent patrol tracking has identified that approximately 33% of police work is spent on responding to reported family violence incidents (NT Police 2015) but with very little apparent positive impact.

A key issue for this study is the ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach of the police responses to IPV incidents. Sherman and Strang (1996) suggest that when IPV incidents trigger the same police response to all levels of harm, then there is the very real risk of doing little about the most serious cases, as police are doing too much on the far more numerous less serious cases. This is currently the case in the NT where all IPV matters are categorised as a ‘Disturbance-Domestic’ and all of them elicit a mandatory minimum level of response. While resources might be better used where harm is greatest, there has been no readily available and reliable means for police to classify the likelihood of serious crime or injury after each response. Even the use of a frequency measure is not sufficient to understand the nature of victims’ experiences of recurring IPV, or to target the most serious cases. Hence, this study employs the Cambridge Crime Harm Index to IPV incidents, the first study restricted to IPV cases that uses a harm index.

IPV in the Aboriginal Population

Indigenous women across Australia are 35 times more likely than White women to sustain injury and require hospitalisation as a result of family violence (Report on Government Services 2009). In the Northern Territory, Aboriginal women are 40 times more likely than White women to be hospitalised as a result of violent assaults, most of which are committed by heavily intoxicated intimate partners (Ramamoorthi et al. 2015). Factors impacting on vulnerability to IPV for Aboriginal people in the NT include isolation or remoteness, inability to leave the community, lack of access to services, language barriers and economic status (National Council to Reduce Violence Against Women and Their Children 2009; Chung et al. 2000).

There are also numerous complex socio-cultural factors that impact on violence in Aboriginal communities in the NT. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Women’s Task Force on Violence (2000, p. 9) stated that

‘The high incidence of violent crime in some Indigenous communities, particularly in remote and rural regions, is exacerbated by factors not present in the broader Australian community…dispossession, cultural fragmentation and marginalisation have contributed to the current crisis in which many Indigenous persons find themselves; high unemployment, poor health, low educational attainment and poverty have become endemic elements in Indigenous lives.’

As well, per-capita alcohol consumption in the NT is one and a half times higher than the Australian average, with alcohol consumption rates for Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people higher than the national average in every age category (Chondor and Wang 2010). The involvement of alcohol in IPV is especially problematic within Aboriginal communities, notwithstanding the unavailability of alcohol for legal sale within many communities, especially in more remote areas (Bolger 1991; Memmott et al. 2001; Putt and Delahunty 2006; Anderson and Wild 2007; Memmott 2010). The reliance on ‘takeaway’ alcohol, a common method of supply in the NT, has led to a proliferation of takeaway alcohol outlets resulting in increased overall consumption and more heavy drinking (Livingston, 2011). Alcohol is the factor most strongly associated with the risk of violent victimisation among Aboriginal people (Mouzos and Makkai 2004; Ramamoorthi et al. 2015) and intimate partner deaths involving an Indigenous offender and victim are 13 times more likely to be related to alcohol than any other kind of homicide in Australia (Deardon and Payne 2009). Data relating to alcohol involvement in the IPV incidents in this data set confirm these earlier findings.

Data

In records kept by the NT Police, all matters involving IPV are categorised as ‘Disturbance-Domestic’, regardless of seriousness. The data reported here are based on an initial group of about 88,000 unique ‘domestic disturbance’ incidents that occurred in the 5 years from 1 January 2010 to 31 December 2014, extracted from the NT Police crime recording and reporting system. The data include all mandatory fields for reporting by police in reported and recorded IPV incidents, and were classified against unique incident numbers and unique person identification numbers. After data cleaning, the final data set consists of 61,796 unique IPV incidents on the NT Police case management system between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2014, including both crimes and non-crimes (Table 1).

In this analysis, ‘crimes’ refer to incidents where there is prima facie evidence that a crime has been committed and there is a victim, offender and at least one criminal offence linked to the incident. ‘Non-crimes’ are incidents where no prima facie offence, victim or offender has been detected. Participants are people recorded as being involved in an incident but where there is no prima facie case to determine whether the person is a victim or offender but they are linked to the incident.

‘Domestic Violence Orders (DVOs)’ are police field-issued orders to a person they believe has or is likely to commit an IPV-related offence: these orders remain in place until confirmed or otherwise by a court. A court-issued DVO includes both confirmed police-issued DVOs and DVOs applied for by the protected person, the police or registered in the NT from another jurisdiction.

There were 23,104 unique dyads in the dataset. Most men and women appear in only one dyad (75%), but 17% appear in two dyads. About 1% of both men and women appear in five to eight dyads and one woman appears in ten dyads, which is the largest number of dyads in which any individual appears.

Frequency

Frequency refers to the number of repeat incidents by unique dyads over a defined period. Where there are repeat incidents, intermittency is based on measured ‘time to failure’, that is, the length of time between repeat incidents (Sherman 1992) and is defined as the average number of days between repeat incidents of IPV for unique dyads. A reduction in the time between repeat incidents within one dyad over time indicates an escalation in frequency of IPV.

In order to track the frequency of both crime and non-crime incidents between dyads and the intermittency between these incidents, a 4-year time period for each individual dyad was established, starting with the date of first report to the police. Any dyad that did not have a full 1460 days (365 × 4 years) was excluded from the analysis, but for all eligible cases we considered nothing that happened after the first 1460 days from the initial report of IPV in that dyad. This cohort therefore used only those dyads with their first incident occurring in 2010.

Seriousness/Severity

The key area of concern for policing is the severity of injury and offences committed. In this data set, this was measured principally through CHI values. To provide useful differentiation between harms of incidents, Sherman et al. (2014, 2016) propose that incident counts be supplemented by translating them into a Cambridge Crime Harm Index (CHI) value. This index provides a method by which the harm of each crime is determined by multiplying the crime by the number of days in prison that crime would attract under sentencing guidelines for England and Wales. These authors argue that CHI values offer greater clarity for evidence-based deployment of police resources and development of policy, providing a standard ‘bottom line for crime’. The CHI appears to be a robust measurement tool that offers greater discrimination than a simple count of incidents.

Escalation is defined as continuing criminal behaviour at a higher level (Feld and Straus 1989). Together, frequency, intermittency and seriousness/severity paint the picture of escalation in IPV. Escalation in terms of harm or seriousness is analysed for all dyads within the 4-year risk period by assigning a CHI value to each offence, using the methodology of Sherman et al. (2014) as adopted by Bland and Ariel (2015).

Escalation in frequency and severity are also investigated via a conditional probability analysis for the dyads to determine the probability of further IPV incidents, given the occurrence of previous incidents: both crimes and non-crimes will be examined.

Findings

Incidents

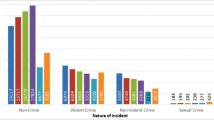

The final data set consisted of 61,796 unique IPV incidents reported to the NT Police between January 2010 and December 2014. The majority of IPV incidents that NT Police attend are classified as non-crimes (67%); significant police resources are evidently being dispatched to IPV incidents that do not involve a crime and have no identified victim or offender.

Crimes

There were 20,292 crimes in the dataset, of which assault was the most serious offence in 69% of cases. Sexual assault was the most serious offence in less than 1% of crimes (Fig. 1). The proportion of dyads with both partners of the same race (Aboriginal or non-Aboriginal) was significantly greater for both crimes and non-crimes than would have been expected by chance (p < 0.0001).

Race, age and gender are three factors by which vulnerability to IPV varies hugely. In the case of crimes, women are overwhelmingly the victims (89%) and they also suffer the majority of crime harm (85%) (Table 2).

It is Aboriginal women, however, who overwhelmingly experienced the highest level of IPV victimisation in the dataset: they were the victims in 83% of crimes (Table 3) and experienced 65% of the crime harm value (Table 4). Note that both tables reflect the degree to which dyads tended to be of the same race.

Although Aboriginal women experience the highest proportion of crime harm, the ratio of the percentage of crime harm experienced (Table 4) to the percentage of victimisation (Table 3) shows that the average crime harm per incident with injury is lowest for Aboriginal women (Table 5). This may indicate that Aboriginal women experience a higher degree of low-level injury than other groups, as well as experiencing serious injury.

Figure 2 shows a sharp increase in victim vulnerability to IPV as both sexes in the dyad approach age 18 years. This increases steeply up to 29 years and then shows a gradual decrease in involvement by age across the remainder of the life-span.

Escalation

To address the question of escalation, a cohort of dyads with consistent tracking time was extracted. This cohort included dyads with a first appearance in the data set in 2010, at least two separate appearances, and within a strict 4-year anniversary window from the first recorded appearance.

Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal males in this data set displayed distinctly different patterns in terms of the number of dyads to which they had been a party in IPV. Approximately two thirds of Aboriginal male victims of IPV in 2014 had previously been the offender in the same dyad, with 77% of those having been the offender more than once; 20 of them (5.6% of all Aboriginal male victims) had previously been an offender on ten or more occasions. One third of non-Aboriginal male victims of IPV in 2014 had previously been the offender in the same dyad, with more than half of those having been the offender only once (Table 6).

Table 7 and Fig. 3 show the pattern of desistance for all IPV incidents where the dyad first appeared in 2010. From year 1 to 2, there is a rate of recidivism of 46.4% and therefore desistance of 53.6%. By the fourth year anniversary, there is only an 11.8% rate of re-offending and as such a cumulative desistance rate of 88.2% from the first appearance of the dyad.

The same pattern is evident with the more serious crime category of IPV alone (Table 8 and Fig. 4). From year 1 to year 2, the re-offending rate is 52.8% (desistance of 47.2%), consistent with the findings for all incidents. By the fourth year anniversary of first appearance in 2010, there is only a 12.7% rate of re-offending (cumulative desistance of 87.3%).

Intermittency and Escalation in Frequency: Another part of the pattern is intermittency for those dyads with repeat IPV incidents. There were 3500 dyad appearances between incidents 1 and 2 with an average intermittency of 270 days; between incidents 2 and 3, intermittency decreased to an average of 210 days. By dyad appearances 9 and 10, intermittency had reduced to an average of 102 days, and between incidents 19 and 20, the average was 47 days. Beyond this point, the data are volatile, with smaller numbers of dyad appearances but with average intermittency as low as 5 days. This pattern of decreased intermittency and therefore escalation in frequency is very strong (Fig. 5).

Escalation in Severity (Crime Harm): While escalation of frequency of IPV over time is evident with persistent dyads, the follow-up question is whether there is escalation in the severity of violence in repeat incidents. Figure 6 displays the ratio of CHI value to total dyad appearances. It is evident that there is a steady increase in crime harm up to six incidents. Following this, the pattern is of a valley of de-escalation in harm followed by a peak of escalation in harm.

The patterns of escalation and de-escalation in the data were analysed in blocks of five incidents (Table 9) with a moving average (Fig. 7). This identifies a pattern of escalation of crime harm for up to 16–20 incidents; after 20 incidents the number of dyads is fewer than 25 for each repeat incident count and estimates are thus likely to be unreliable.

Conditional Probability: The final dimension of escalation and desistance examined here is conditional probability, that is, given an IPV incident has occurred, what are the probabilities of second and subsequent IPV incidents occurring? Thirty-seven percent of first IPV appearances are crimes (Fig. 8). The conditional probability of a crime following either another crime or non-crime is 38% at the second incident. This rate steadily escalates to 44% at the sixth crime and then stabilises at about this level for the remainder of crimes up to 20 incidents. After 20 repeat incidents, the dyad numbers fall to under 60 and the data become unreliable.

Conversely, the conditional probability of non-crimes occurring after any type of IPV incident de-escalates from 63% on the first incident to 56% at the sixth incident and then stabilises at this level consistent with crime incidents.

To further examine escalation through conditional probability, we examined the probability of crime incidents following other crime incidents as compared to non-crime incidents (Fig. 9). There is a much greater probability of a crime incident following another crime incident than a non-crime incident. The conditional probability increases from 55% at the second incident to 58% at the seventh incident. A crime incident following a non-crime incident also has an escalating conditional probability of 27% at the second incident to 36% at the seventh incident.

Discussion

Across Australia, about 4% of the population are estimated to have reported to police incidents of IPV (ABS 2012), but the survey on which these data are based does not include Aboriginal communities in the NT. In fact the NT situation with its high Aboriginal population is considerably bleaker: in this study, 9% of the NT population over 16 years reported being the victim of at least one IPV incident in only a 5-year period. In this data set, almost nine out of ten victims were Aboriginal, and eight of them were Aboriginal women. Given that Aboriginal women are about 10% of the total NT population, this means that almost three quarters of them have been the victim of IPV recorded in police reports over a 5-year period. Nearly all the offenders against these women are Aboriginal men. The converse is also true: of the one in ten Aboriginal men who are recorded as victims of IPV, Aboriginal women are almost always the offenders.

The age of highest vulnerability in this data set for IPV victims, offenders and/or participants was 20–34 years. Given that the average age of Aboriginal people is much younger than non-Aboriginal people (38% of the Aboriginal population in the NT is currently under 15 years, compared with 19% of the non-Aboriginal population (ABS 2011), the impact of this young population will likely negatively impact on the future rates of Aboriginal IPV in the NT.

The pattern of rapid escalation at around the age of 20 for both males and females does, however, represent a targeting opportunity for early intervention. Whereas only 8% of incidents in this data set involved 15–19-year olds, the three successive 5-year age groups were each more than double that figure at around 17%. This represents an important moment for intervening with young people not yet involved in repeat incidents.

Almost half of the crime incidents involved the breach of a DVO, and half of these also included an assault against a person or their property. The high rate of breaching DVOs in about 60% of IPV crimes should lower expectations about their capacity to constrain offenders’ behaviour. In addition, most DVO breaches by Aboriginal men and women are against current partners. This seems to indicate that Aboriginal dyads are less likely to comply with conditions of DVOs than non-Aboriginal offenders. This point is especially worthy of mention given that many NT Aboriginal people live in remote communities and have strong kinship and cultural ties. Because Aboriginal dyads tend to remain a couple and live in small communities, dealing with IPV as ‘victim’ and ‘offender’ using arrest and DVOs as the primary means of intervention seems unlikely to be effective.

Given the way in which police records are organised, dyads with repeat incidents can get lost in the system. Over 10,000 dyads have five or more incidents and over 1200 dyads have 15 or more incidents. Yet there is little opportunity to intensively track any of them until a risk assessment process is developed to identify the individual dyads at most risk of harm. It should also be possible for police to target and monitor recidivist offenders who continue to commit IPV at a high rate and who also commit IPV across a number of dyads.

In this dataset, fewer than one quarter of IPV incidents resulted in injury and only about 4% resulted in serious injury. Aboriginal women were the victims in most cases (83% of total incidents), but their crime harm per incident with injury was lower than for other victims at 65% of total crime harm. This should not, however, be interpreted as minimising the consequences of IPV on Aboriginal women. The data include both minor and serious injuries. It may be that Aboriginal women appear at a much higher frequency in the minor injury category, and that this skews the results toward lower crime harm overall for Aboriginal women.

It has been argued (Straus 2010; Bair-Merritt et al. 2010) that women’s motivations for offending are qualitatively different from men’s in that women will often perpetrate IPV either in self-defence or in retaliation for IPV being perpetrated on them. These data indicate that at least for Aboriginal women this theory cannot be discounted. Approximately two thirds of Aboriginal male victims of IPV in 2014 had previously been the offender in the same dyad (see Table 6), with three quarters of those having been the offender more than once in the previous 4 years. So it may be the case that Aboriginal women often commit IPV in self-defence or retaliation: this may especially be likely in the cohort of Aboriginal dyads where the violence is mutual, high-harm and sustained over time. These chronic high-harm dyads, or those alternating between high- and low-harm incidents where both partners are the initiators of violence, might be prioritised for the testing of alternative interventions.

Targeting Escalation—or Not

It is clear from this analysis that the view that IPV always escalates in frequency and severity over time is not the case in the NT: almost half the dyads (43%) tracked over the 4-year period had only one occurrence in the dataset. There is a range of reasons other than desistance that may account for no repeats, including the death of one of the partners, incarceration, separation, leaving the jurisdiction or simply failing to report further IPV. These explanations are not compelling, however, given (1) the predominantly young age of the dyads, (2) that two thirds of the incidents are non-crimes, (3) that Aboriginal dyads tend to remain together and (4) that there is negligible long-term migration out of the jurisdiction for Aboriginal dyads. The most credible hypothesis is consistent with general criminological evidence that some offenders do indeed desist, although at varying speeds. It is also consistent with growing evidence that most IPV is low-level and tends not to escalate (Bland and Ariel 2015; Sherman et al. 2016).

Of those dyads that do persist with more than one reported IPV incident, however, the pattern of escalation in frequency showed strongly. There is a definite pattern of escalation in frequency up to 20 incidents, with an average intermittency of 9 months between incidents 1 and 2, and down to 7 weeks between incidents 19 and 20.

An even more important question is whether there is escalation in harm in repeat incidents. For those dyads where there are recurring incidents of IPV over time, we found an unbroken pattern of escalation in harm up to six incidents. Following the sixth incident, the pattern is of a valley of de-escalation in harm followed by re-escalation to an overall average increase in escalation, again (as in frequency) up to 20 incidents.

We also examined the conditional probability of non-crime and crime recidivism within dyads. It was found that there was a high probability of a crime following a previous crime but that this probability did not escalate over subsequent IPV incidents. However, where a crime followed a non-crime, there was escalation across seven subsequent incidents. These results are consistent with other findings (e.g. Piquero et al. 2006) which show that some IPV offenders escalate and de-escalate their violent behaviour in a relationship, while others maintain stable low-level aggression or stable high-level violence.

In all of these findings, the exacerbating effect of alcohol cannot be ignored. A defining factor of the three regional centres with the highest number of IPV incidents per capita (Alice Springs, Katherine and Tennant Creek) is that all have a higher proportion of Aboriginal residents than any other single location, and in almost all these incidents (90%) the offender was intoxicated. The key difference between these and other locations is the availability of alcohol.

Conclusion

The characteristics, frequency and seriousness of IPV in the NT described here provide the start of an evidence-base for police to develop strategies for targeting serious harm IPV, especially in indigenous communities.

The principal conclusion is that non-crime cases with low-level harm make up two thirds of all police responses to IPV. Because each case is subject to minimum police response guidelines, it is evident that NT Police are currently investing considerable resources in low-harm incidents that could be invested in cases suffering far greater levels of harm. There is a clear opportunity for police to develop a risk assessment process to guide responders in determining when a case presents low-risk of re-offending or future harm versus cases that may be high-harm in the future. Following this descriptive analysis, future research can focus on appropriate responses for the different typologies of IPV identified here: one-time reported IPV, chronic low-harm dyads and chronic high-harm dyads.

This targeting analysis confirms other research that shows no escalation in frequency or severity of domestic abuse among predominantly White European populations (Bland and Ariel 2015; Sherman et al. 2016). Yet it also provides the first systematic test of the escalation hypothesis about IPV reported to police among Australian Aboriginal dyads. That evidence provides a strong basis in evidence for developing a two-track policy for policing IPV in Australian areas with substantial Indigenous populations.

Track 1 would serve dyads (of either race) presenting for the first or second time, for whom a light touch may generally be sufficient. There may be good reason, for example, not to make arrests in such cases as long as there is no injury (Sherman 1992).

Track 2 could be set in motion for any couple known to have had two or more prior offences. Dyads on this track could receive a far more intensive strategic investment, including the testing of new strategies for prevention of escalation in harm or frequency of IPV. Yet because this pattern of escalation is found only in a minority of Aboriginal dyads, it is important to base policy on evidence-based targeting of dyads with prior occurrences rather than race.

References

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Women's Task Force on Violence (2000) The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Women’s Task Force on Violence Report, (Rev. Ed.), Brisbane: Department of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Policy and Development.

Anderson, P., & Wild, R. (2007). Ampe Akelyernemane Meke Mekarle—little children are sacred: Report of the Northern Territory Board of Inquiry into the protection of Aboriginal children from sexual abuse. Darwin: Northern Territory Government.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2011) Population characteristics, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, 2006 ABC Cat no 4713.0.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2012) Personal safety survey, ABS Cat no 4906.0.

Bair-Merritt, M. H., Crowne, S. S., Thompson, D. A., Sibinga, E., Trent, M., & Campbell, J. (2010). Why do women use intimate partner violence? A systematic review of women’s motivations. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 11(4), 178–189.

Bland, M., & Ariel, B. (2015). Targeting escalation in reported domestic abuse evidence from 36,000 callouts. International Criminal Justice Review, 25(1), 30–53.

Bolger, A. (1991). Aboriginal women and violence. Canberra: Australian National University, North Australia Research Unit.

Chondor, R., & Wang, Z. (2010). Alcohol use in the Northern Territory: health gains planning information sheet. Darwin: Northern Territory Government.

Chung, D., Kennedy, R., O’Brien, B. and Wendt, S. with assistance from Cody, S. (2000) Home safe home: the link between domestic and family violence and women’s homelessness, Partnerships Against Domestic Violence, The Women’s Services Network (WESNET) and the Department of Families and Community Services. Retrieved 15 August 2015 from http://wesnet.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/homesafehome.pdf

Dearden, J., & Payne, J. (2009). Alcohol and homicide in Australia. Trends & Issues in Crime & Criminal Justice, 372 Retrieved 23 July 2015 from http://aic.gov.au/publications/current%20series/tandi/361380/tandi372.html.

Feld, S. L., & Straus, M. A. (1989). Escalation and desistance of wife assault in marriage. Criminology, 27(1), 141–161.

Livingston, M. (2011). A longitudinal analysis of alcohol outlet density and domestic violence. Addiction, 106, 919–925.

Memmott, P., Stacy, R., Chambers, C., & Keys, C. (2001). Violence in indigenous communities. Canberra: Crime Prevention Branch, Commonwealth Attorney-General's Department.

Memmott, P. (2010). On regional and cultural approaches to Australian indigenous violence. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 43(2), 333–355.

Mouzos, J. and Makkai, T. (2004) Women’s experiences of male violence: findings from the Australian component of the International Violence Against Women Survey (IVAWS), Research and public policy series No. 56, Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology. Retrieved 23 July 2015 from http://www.aic.gov.au/publications/current series/ rpp/41-60/rpp56.aspx

National Council to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children (NCRVWC) (2009). Time for action: the National Council’s plan for Australia to reduce violence against women and their children, 2009–2021. Retrieved 23 July 2015 from http://www.nswrapecrisis.com.au/Portals/0/PDF/The_Plan.pdf

Northern Territory Police, ‘Domestic violence strategy’ (Unpublished Northern Territory Police 2014).

Northern Territory Police, ‘Business excellence project’ (Unpublished Northern Territory Police 2015).

Piquero, A. R., Brame, R., Fagan, J., & Moffitt, T. E. (2006). Assessing the offending activity of criminal domestic violence suspects: offense specialization, escalation, and de-escalation evidence from the Spouse Assault Replication Program. Public Health Rep, 121(4), 409–418.

Putt, J., & Delahunty, B. (2006). Illicit drug use in rural and remote indigenous communities. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology.

Ramamoorthi, R., Jayaraj, R., Notaras, L., & Thomas, M. (2015). Epidemiology, aetiology, and motivation of alcohol misuse among Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders of the Northern Territory: a descriptive review. J Ethn Subst Abus, 14(1), 1–11.

Report on Government Services (2009). Australian Government Productivity Commission. http://www.pc.gov.au/research/ongoing/report-on-government-services/2009/2009.

Sherman, L. W. (1992). Policing domestic violence: experiments and dilemmas. New York: Free Press.

Sherman, L.W., Neyroud P.W. and Neyroud, E.C., (2014) ‘The Cambridge Crime Harm Index (CHI): measuring total harm from crime based on sentencing guidelines, Version 2.0’. (Unpublished report for University of Cambridge).

Sherman, L.W., Bland, M., House, P. and Strang, H. (2016). Targeting family violence reported to Western Australia Police, 2010–2015: the Felonious few vs. the miscreant many. Report to Deputy Police Commissione Stephen Brown . Perth: Western Australia Police.

Sherman, L.W. and Strang, H. (1996) ‘Policing domestic violence: the problem solving paradigm’ (paper presented at the Problem-Solving Policing as Crime Prevention Conference, Stockholm, 1996).

Straus, M. A. (2010). Thirty years of denying the evidence on gender symmetry in partner violence: implications for prevention and treatment. Partner Abuse, 1(3), 332–362.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kerr, J., Whyte, C. & Strang, H. Targeting Escalation and Harm in Intimate Partner Violence: Evidence from Northern Territory Police, Australia. Camb J Evid Based Polic 1, 143–159 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41887-017-0005-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41887-017-0005-z