Abstract

In June 2015, about 53,000 people were affected by unusually severe floods in Accra, Ghana. The real impact of such a disaster is a product of exposure (“Who was affected?”), vulnerability (“How much did the affected households lose?”), and socioeconomic resilience (“What was their ability to cope and recover?”). This study explores these three dimensions to assess whether poor households were disproportionally affected by the 2015 floods by using household survey data collected in Accra in 2017. It reaches four main conclusions. (1) In the studied area, there is no difference in annual expenditures between the households who were affected and those who were not affected by the flood. (2) Poorer households lost less than their richer neighbors in absolute terms, but more when compared with their annual expenditure level, and poorer households are over-represented among the most severely affected households. (3) More than 30% of the affected households report not having recovered two years after the shock, and the ability of households to recover was driven by the magnitude of their losses, sources of income, and access to coping mechanisms, but not by their poverty, as measured by the annual expenditure level. (4) There is a measurable effect of the flood on behaviors, undermining savings and investment in enterprises. The study concludes with two policy implications. First, flood management could be considered as a component of the poverty-reduction strategy in the city. Second, building resilience is not only about increasing income. It also requires providing the population with coping and recovery mechanisms such as financial instruments. A flood management program needs to be designed to target low-resilience households, such as those with little access to coping and recovery mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A World Bank report on urban floods in Antananarivo using a similar methodology is forthcoming.

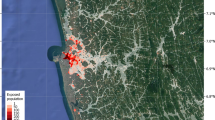

A flood map was later produced by the World Bank in 2018 (Klopstra et al. forthcoming)

Survey of Wellbeing via Instant and Frequent Tracking (SWIFT) methodology found here: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/591711545170814297/Survey-of-Wellbeing-via-Instant-and-Frequent-Tracking-SWIFT-Data-Collection-Guidelines

Greater Accra Metropolitan Area is made up of Accra Metropolitan District and 9 other neighboring urban or peri-urban districts

The reason why the expenditure levels in our sample match the GLSS6 could be due to the economic growth experienced between 2012/2013 and 2017. Slum areas may also attract households from both low and relatively high income levels thanks to the accessibility to jobs and social and cultural networks that may exist in these areas.

Tenure, household assets, housing quality, household member education and labor status, access to public services, etc. For more detail on the SWIFT methodology, please see the handbook: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/591711545170814297/Survey-of-Well-Being-via-Instant-and-Frequent-Tracking-SWIFT-Data-Collection-Guidelines

The levels of the thresholds were selected by considering the distribution of the losses in relation to income. A large enough sample of households lost over 10% of annual expenditure to be able to say something statistically meaningful about this subgroup, while above the 10% threshold, the number of households start to diminish quickly.

We only have information on households who were living in the surveyed areas two years after the floods. We cannot say anything about households who have been affected but moved outside the surveyed areas after the shock.

Other determinants of cost of rent include dwelling type, roof material, size and type of water service.

Other determinants of total housing costs are wall material, type of water and sanitation services and distance to CBD. When elevation is introduced in the regression, however, the exposure to the 2015 flood does not have a significant impact on housing costs anymore. The correlation between elevation and exposure to the 2015 floods is likely to explain this result.

Households from the first quartile represent 38% of the households losing more than 5% of annual expenditure, while they represent 25% of the population – the ratio 38/25 = 1.52.

See Figure A in the Online Appendix

We use the official Ghana national poverty rate of 1314 cedis.

Follow-up phone interview three years after the flood suggests that about half of the households that did not recover in two years had still not recovered after three years.

Coarsened Exact Matching is a method of preprocessing data to control for some or all of the potentially confounding influence of pretreatment control variables by reducing imbalance between the treated and control groups. See section 3 in the Online Appendix for a description of the methodology.

With a broader definition of poverty that would include financial inclusion, social capital, and stability of income, poverty would affect the ability to recover. Here, we define poverty only through the level of annual expenditure.

Housing investments include a wide variety of actions such as expanding the dwelling, upgrading roof, wall or floor material, adding or heightening the floor, upgrading the windows or adding toilets or even blocking the walls to prevent flooding.

References

Akter S, Mallick B (2013) The poverty–vulnerability–resilience Nexus: evidence from Bangladesh. Ecol Econ 96:114–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2013.10.008

Arouri M, Nguyen C, Youssef AB (2015) Natural disasters, household welfare, and resilience: evidence from rural Vietnam. World Dev 70:59–77

Baez JE, Lucchetti L, Genoni ME, Salazar M (2017) Gone with the Storm: Rainfall Shocks and Household Wellbeing in Guatemala. The Journal of Development Studies 53(8):1253–1271

Bangalore M, Smith A, Veldkamp T (2018) Exposure to floods, climate change, and poverty in Vietnam. Economics of Disasters and Climate Change 2(6):1–21

Baulch, B (ed.) (2011) Why poverty persists: Poverty dynamics in Asia and Africa, Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar

Beltran A, Maddison D, Elliott R (2015). “Is Flood Risk Capitalised in Property Values? A Meta-analysis Approach from the Housing Market.” Paper presented at EAERE (European Association of Environmental and Resource Economists), Helsinki, Finland, June 24–27

Burke M, Hsiang SM, Miguel E (2015) Global non-linear effect of temperature on economic production. Nature 527:235–239

Carter MR, Little PD, Mogues T, Negatu W (2007) Poverty traps and natural disasters in Ethiopia and Honduras. World Dev 35:835–856. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2006.09.010

Dang HH, Lanjouw PF, Swinkels RA (2014). “Who remained in poverty, who moved up, and who fell down? an investigation of poverty dynamics in Senegal in the late 2000s.” Policy Research working paper; no. WPS 7141; Washington, DC: World Bank Group

Decon S (2002) Income risk, coping strategies, and safety nets. World Bank Res Obs 17(2):141–166

Durand-Lasserve A, Selod H, Durand-Lasserve M (2013) A systemic analysis of land markets and land institutions in west African cities: rules and practices-the case of Bamako, Mali. In: Policy research working paper. World Bank Group, Washington, DC

Eakin H, Bojórquez-Tapia LA, Janssen MA, Georgescu M, Manuel-Navarrete D, Vivoni ER, Escalante AE, Baeza-Castro A, Mazari-Hiriart M, Lerner AM (2017) Urban resilience efforts must consider social and political forces. PNAS 114(2):186–189

Engstrom R, Pavelesku D, Tanaka T, Wambile A (2017) Monetary and non-monetary poverty in urban slums in Accra: Combining geospatial data and machine learning to study urban poverty, Working paper. http://www3.grips.ac.jp/~econseminar/seminar2017/Tanaka.pdf

Elbers C, Gunning JW, Kinsey B (2007) Growth and risk: methodology and micro evidence. World Bank Econ Rev 21:1–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/lhl008

Erman A, Tariverdi M, Obolensky M, Chen X, Vincent RC, Malgioglio S, Maruyama Rentschler JE, Hallegatte S, Yoshida N (2019) Wading out the storm: The role of poverty in exposure, vulnerability and resilience to floods in Dar Es Salaam (English). Policy research working paper; no. WPS 8976. Washington, D.C. World Bank Group

Ghana Statistical Service (2018) Ghana living standards survey round 7 (GLSS7): poverty trends in Ghana 2005 –2017. Accra: GSS. http://www2.statsghana.gov.gh/docfiles/publications/GLSS7/Poverty%20Profile%20Report_2005%20-%202017.pdf

Hallegatte S, Bangalore M, Bonzanigo L, Fay M, Narloch U, Rozenberg J, Vogt-Schilb A (2014) Climate change and poverty: An analytical framework. policy research working paper; No. 7126. Washington, DC. World Bank Group

Hallegatte S, Bangalore M, Jouanjean MA (2016a). “Higher losses and slower development in the absence of disaster risk management investments.” Policy Research Working Paper, World Bank, Washington, DC

Hallegatte S, Bangalore M, Bonzanigo L, Fay M, Kane T, Narloch U, Rozenberg J (2016b) Shock waves: managing the impacts of climate change on poverty. Climate change and development series. World Bank, Washington, DC

Hallegatte S, Vogt-Schilb A, Bangalore M, Rozenberg J (2017). Unbreakable: building the resilience of the poor in the face of natural disasters. World Bank Publications

Husby T, Hofkes M (2015). “Loss Aversion on the Housing Market and Capitalisation of Flood Risk.” Paper presented at EAERE (European Association of Environmental and Resource Economists), Helsinki, Finland, June 24–27

Iacus SM, King G, Porro G (2012) Causal inference without balance checking: coarsened exact matching. Polit Anal 20(1):1–24

Islam SN, Winkel J (2017) Climate change and social inequality DESA working paper no. 152

Jones L, Samman E, Vinck P (2018) Subjective measures of household resilience to climate variability and change: insights from a nationally representative survey of Tanzania. Ecol Soc 23(1):9

Kalkuhl M, Wenz L (2018) “The impact of climate conditions on economic production. Evidence from a global panel of regions”, ZBW – Leibniz information Centre for Economics, Kiel, Hamburg

Keerthiratne S, Tol RSJ (2018) Impact of natural disasters on income inequality in Sri Lanka. World Dev 105:217–230

Klopstra D, Udo J, Gamadeku R, van Bork G, van Hussen K, Berentsen K, Slabbers S, Ahlijah O (forthcoming) Greater Accra Climate Risk Mitigation Strategy, draft report. HKV

Marinetti C, Martens E, Modderman N, Arntz LR (2016). “Methodology: Urban Flood Risk Assessment, Project Flood Risk Accra.” https://repository.tudelft.nl/islandora/object/uuid:14c432e0-4eba-49b1-be50-8e4577ae1058/datastream/OBJ

Mendelsohn R, Dinar A, Williams L (2006) The distributional impact of climate change on rich and poor countries. Environ Dev Econ 11:159–178

McCarthy N, Kilic T, De La Fuente A, Brubaker J (2018) Shelter from the storm? Household-level impacts of, and responses to, the 2015 floods in Malawi. Economics of Disasters and Climate Change 2(3):237–258

Moser CN, ed. (2008) Reducing global poverty: the case for asset accumulation. Brookings Institution Press

Mutter JC (2015) Disaster profiteers: how natural disasters make the rich richer and the poor even poorer. St. Martin’s Press, New York

Noy I, Patel P (2014). “Floods and Spillovers: Households after the 2011 Great Flood in Thailand.” Working Paper Series No. 3609, School of Economics and Finance, Victoria University of Wellington

ODI (Overseas Development Institute) and GFDRR (Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery) (2015) “Unlocking the Triple Dividend of Resilience—Why Investing in DRM Pays Off.” http://www.odi.org/tripledividend

Opondo DO (2013) Erosive coping after the 2011 floods in Kenya. International Journal of Global Warming 5:452–466. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJGW.2013.057285

Patankar A (2015) “The exposure, vulnerability and adaptive capacity of households to floods in Mumbai.” Policy research working paper 7481, World Bank, Washington, DC

Patankar AM (2017). “Colombo: exposure, vulnerability, and ability to respond to floods”. Policy research working paper; no. WPS 8084. Washington, D.C.: world bank group

Quisumbing AR (2007) Poverty Transitions, shocks, and consumption in rural Bangladesh: Preliminary results from a longitudinal household survey. Chronic Poverty Research Centre Working Paper No. 105.

Rain D, Engstrom, R, Ludlow, C, Antos S (2011). “Accra Ghana: A City Vulnerable to Flooding and Drought induced migration”. UN Habitat Cities and Climate Change: Global Report on Human Settlements 2011. https://unhabitat.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/GRHS2011CaseStudyChapter04Accra.pdf

Skoufias E (2003) Economic crises and natural disasters: coping strategies and policy implications. World Dev 31(7):1087–1102

Takasaki Y (2011) Do local elites capture natural disaster reconstruction funds? J Dev Stud 47(9):1281–1298

Taupo T, Cuffe H, Noy I (2018) Household vulnerability on the frontline of climate change: the Pacific atoll nation of Tuvalu. Environ Econ Policy Stud 20(7):1–35

UN Country Team (UNCT) Ghana (2015) Ghana – floods situation report. Accra: United Nations – Ghana. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/unct_sitrep-_accra_floods_08062015.pdf

UNHABITAT; AMA (2011). Participatory slum upgrading and prevention Millennium City of Accra, Ghana

UNHABITAT (2008). UN-HABITAT: Ghana - Overview of the current Housing Rights situation and related activities. http://lib.ohchr.org/HRBodies/UPR/Documents/Session2/GH/UNHABITAT_GHA_UPR_S2_2008_UnitedNationsHABITAT_uprsubmission.pdf

Wineman A, Mason NM, Ochieng J, Kirimi L (2017) Weather extremes and household welfare in rural Kenya. Food Security 9:281–300

Winsemius HC, Jongman B, Veldkamp TIE, Hallegatte S (2018) Disaster risk, climate change, and poverty: assessing the global exposure of poor people to floods and droughts. Environ Dev Econ 23(3):328–348

World Bank (2017) Enhancing urban resilience in the Greater Accra metropolitan area. In: Working paper. World Bank Group, Washington, D.C.

World Bank (2015) Rising through cities in Ghana: urbanization review - overview report (English). Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group. WSMP (2008) Use of toilet facilities in Ghana. WSMP brief

Acknowledgments

This article was written based on the results of a report written by a team composed of Alvina Erman, Elliot Motte, Radhika Goyal, Akosua Asare, Shinya Takamatsu, Xiaomeng Chen, Silvia Malgioglio, Alexander Skinner, and Nobuo Yoshida, and led by Stephane Hallegatte. The authors received invaluable support in Ghana from Rachel Annan, Frederick Addison, Akosua Asare and Charlotte Hayfron from the World Bank and Dr. Clement Adamba and Prof. Robert Osei from ISSER, University of Ghana. We would like to thank the Accra Metropolitan Assembly (AMA) for supporting this work and a special thank you to Lydia Addy and her team for providing guidance of the local context. We would also like to thank the Sub-Metro Directors and their teams for supporting enumerators during data collection in areas covered by the survey.

Marianne Fay, Chief Economist for Sustainable Development, and Henry G. R. Kerali, Country Director for Ghana, chaired the World Bank internal review panel that included Kirsten Hommann, Oscar Ishizawa, Emmanuel Skoufias and Sarah Coll-Black. This report benefited from contributions by Kathleen G. Beegle, Tomomi Tanaka, Ryan Engstrom, Dan Pavelesku, Yan F. Zhang, Shohei Nakamura, Brian Walsh, Asmita Tiwari, Oleksiy Ivaschenko, Carl Christian Dingel, Nancy Lozano Garcia, Yohannes Yemane Kesete, Edward Charles Anderson, Keren Carla Charles, Sajid Anwar, Julie Rozenberg, Eric Dickson, Monica Yanez Pagans, Tiguist Fisseha, Oscar Ishizawa, Emmanuel Skoufias, Pauline Cazaubon, Frederico Ferreira Fonse Pedroso, Jonas Ingemann Parby, Emilie Bernadette Perge, Claudia Soto, Ivo Imparato, Beatrix Allah-Mensah, Carlos Silva-Jauregui.

The report was sponsored by the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR) with additional support from the World Bank Research Support Budget (RSB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 121 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Erman, A., Motte, E., Goyal, R. et al. The Road to Recovery the Role of Poverty in the Exposure, Vulnerability and Resilience to Floods in Accra. EconDisCliCha 4, 171–193 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41885-019-00056-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41885-019-00056-w