Abstract

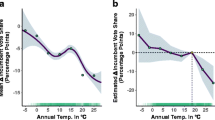

We explore how the political survival of leaders in different political regimes is affected by drought and flooding precipitation, which are the two major anticipated impacts of anthropogenic climate change. Using georeferenced climate data for the entire world and the Archigos dataset for the period of 1950–2010, we find that irregular political exits, such as coups or revolutions, are not significantly affected by climate impacts. Similarly, drought has a positive but insignificant effect on all types of political exits. On the other hand, we find that floods increase political turnover through the regular means such as elections or term limits. Democracies are better able to withstand the pressures arising from the economic and social disruptions associated with high precipitation than other institutional arrangements. Our results further suggest that, in the context of floods, political institutions play a more important role than economic development for the leaders’ political survival.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Notably, however, Neumayer et al. do not distinguish between different political institutions, using GDP and per capita income as the two control variables.

Both Flores and Smith (2013) and Chang and Berdiev (2015) rely on the Emergency Events Database (EM-DAT), which reports population impacts based on information provided by UN agencies, non-governmental organization, insurance companies, research institutes and press agencies (D. Guha-Sapir et al. 2015). The accuracy of the impacts data – such as the number of people killed, displaced, or requiring emergency assistance – depends on the quality of global monitoring and reporting of the relevant disasters. In addition, Chang and Berdiev employ a conditional logit model that is problematic because it does not explicitly account for time dependencies in the data, and therefore might produce overly optimistic results (Beck et al. 1998).

By convention, “adaptation” refers to measures that deal with the consequences of climate change, whereas “mitigation” aims to curb or halt the process of climate change itself (IPCC 2014).

Some exceptions exist. For example, non-democratic leaders can exploit donor preferences for political stability to trade higher political risk for greater rent extraction (Steinwand 2014).

For grid cells that are not completely contained by a country’s boundaries, we use national identification of the largest territory within the grid cell to determine the national identification of the cell. For coastal areas, the grid cell has a national identification of a country as long as there is at least some (no matter how small) land area within the cell.

SPEI calculation uses the monthly difference between precipitation and potential evapotranspiration (PET). This difference between precipitation and PET describes the water balance of the soil (Thornthwaite 1948). Although other drought indices are also based on water balance—such as the Palmer drought severity index (PDSI) (Palmer 1965)—SPEI is more convenient to calculate and can represent different time scales. At longer timescales (e.g., 12 months), the SPEI has been shown to correlate with the self-calibrating PDSI for a set of observatories with different climate characteristics, located in different parts of the world (Vicente-Serrano et al. 2009).

For example, developed countries may have a higher rate of reporting (but not actual occurrence) of various disasters than developing countries.

One exception that we could find is a study of length of stay and hospital discharge by (Sá et al. 2007). We note, however, that the ratio of the number of patients (34,250) to the number of hospitals (78) is much larger than the ratio of the number of leaders (1495) to the number of countries (172): 439.1 and 8.7, respectively. Even for a large number of patients relative to the number of hospitals, the authors acknowledge possible limitations associated with the fixed-effects approach.

The CIF is the appropriate quantity of interest for competing risk models. Standard survival functions are not well defined because the event of interest depends on the covariates both directly and indirectly through the effect of the covariates on competing events (Fine and Gray 1999).

References

Acemoglu D, Johnson S, Robinson JA (2001) The colonial origins of comparative development: an empirical investigation. Am Econ Rev 91(5):1369–1401

Achen CH, Bartels LM (2004) Blind retrospection. Electoral responses to drought, flu, and shark attacks. Estudios/working papers (Centro de Estudios Avanzados en Ciencias Sociales) (199)

Ashley ST, Ashley WS (2008) Flood fatalities in the United States. J Appl Meteorol Climatol 47(3):805–818. https://doi.org/10.1175/2007JAMC1611.1

Bechtel MM, Hainmueller J (2011) How lasting is voter gratitude? An analysis of the short- and long-term electoral returns to beneficial policy. Am J Polit Sci 55(4):852–868. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00533.x

Beck N, Katz JN, Tucker R (1998) Taking time seriously: time-series-cross-section analysis with binary dependent variable. Am J Polit Sci 42(4):1260–1288

Bhaduri B, Bright E, Coleman P, Urban M (2007) LandScan USA: a high-resolution geospatial and temporal modeling approach for population distribution and dynamics. GeoJournal 69(1–2):103–117. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-007-9105-9

Black R, Adger WN, Arnell NW, Dercon S, Geddes A, Thomas D (2011) The effect of environmental change on human migration. Glob Environ Chang 21(S1):S3–S11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.10.001

Brakenridge GR (2014) Global active archive of large flood events. Retrieved from: http://floodobservatory.colorado.edu

Bueno de Mesquita B, Smith A (2009) Political survival and endogenous institutional change. Comp Pol Stud 42(2):167–197

Bueno de Mesquita B, Smith A, Siverson RH, Morrow JD (2003) The logic of political survival. MIT Press, Cambridge

Buhaug H (2010) Climate not to blame for African civil wars. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107(38):16477–16482. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1005739107

Burkett M (2012) Climate refugees. In: Alam S, Bhuiyan JH, Chowdhury TM, Techera EJ (eds) Routledge handbook of international environmental law. Routledge, New York

Chang C-P, Berdiev AN (2015) Do natural disasters increase the likelihood that a government is replaced? Appl Econ 47(17):1788–1808. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2014.1002894

Chiozza G, Goemans HE (2004) International conflict and the tenure of leaders: is war still ex post inefficient? Am J Polit Sci 48(3):604–619

De Waal A (1989) Famine mortality: a case study of Darfur, Sudan 1984–5. Popul Stud 43(1):5–24

Deo RC, Byun H-R, Adamowski JF, Kim D-W (2015) A real-time flood monitoring index based on daily effective precipitation and its application to Brisbane and Lockyer Valley flood events. Water Resour Manag 29(11):4075–4093. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-015-1046-3

Ferejohn J (1986) Incumbent performance and electoral control. Public Choice 50:5–25

Fine JP, Gray RJ (1999) A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 94(446):496–509. https://doi.org/10.2307/2670170

Flores AQ, Smith A (2013) Leader survival and natural disasters. Br J Polit Sci 43(4):821–843

Gray R (1988) A class of k-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of a competing risk. Ann Stat 16(3):1141–1154

Goemans HE (2008) Which way out? The manner and consequences of losing office. J Confl Resolut 52(6):771–794

Goemans HE, Gleditsch KS, Chiozza G (2009) Introducing Archigos: a dataset of political leaders. J Peace Res 46(2):269–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343308100719

Guha-Sapir D, Below R & Hoyois P (2015) EM-DAT: International Disaster Database. Retrieved from: http://www.emdat.be

Harris I, Jones PD, Osborn TJ, Lister DH (2014) Updated high-resolution grids of monthly climatic observations – the CRU TS3.10 dataset. Int J Climatol 34(3):623–642. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.3711

Healy A, Malhotra N (2009) Myopic voters and natural disaster policy. Am Polit Sci Rev 103(3):387–406

Heston A, Summers R, Aten B (2012) Penn World Table Version 7.1. Center for International Comparisons of Production, Income and Prices at the University of Pennsylvania, November 2012

Hirabayashi Y, Mahendran R, Koirala S, Konoshima L, Yamazaki D, Watanabe S et al (2013) Global flood risk under climate change. Nat Clim Chang 3(9):816–821

Hsiang SM, Burke M, Miguel E (2013) Quantifying the influence of climate on human conflict. Science 341(6151):1235367. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1235367

IPCC (2014) Climate change 2014: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Part a: global and sectoral aspects. Contribution of working group II to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Retrieved from Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA

Javeline D (2014) The most important topic political scientists are not studying: adapting to climate change. Perspect Polit 12(2):420–434

Jonkman SN, Kelman I (2005) An analysis of the causes and circumstances of flood disaster deaths. Disasters 29(1):75–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0361-3666.2005.00275.x

Kahn ME (2005) The death toll from natural disasters: the role of income, geography, and institutions. Rev Econ Stat 87(2):271–284

Kelley CP, Mohtadi S, Cane MA, Seager R, Kushnir Y (2015) Climate change in the fertile crescent and implications of the recent Syrian drought. Proc Natl Acad Sci. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1421533112

King G, Tomz MR, Wittenberg J (2000) Making the most of statistical analyses: improving interpretation and presentation. Am J Polit Sci 44(2):347–361

Kirsch TD, Wadhwani C, Sauer L, Doocy S, Catlett C (2012) Impact of the 2010 Pakistan floods on rural and urban populations at six months, edition 1. PLOS Currents Disasters. https://doi.org/10.1371/4fdfb212d2432

Komori D, Nakamura S, Kiguchi M, Nishijima A, Yamazaki D, Suzuki S et al (2012) Characteristics of the 2011 Chao Phraya River flood in central Thailand. Hydrol Res Lett 6(0):41–46

Lazarev E, Sobolev A, Soboleva IV, Sokolov B (2014) Trial by fire: a natural Disaster's impact on support for the authorities in rural Russia. World Polit 66(04):641–668

Licht A (2010) Coming into money: the impact of foreign aid on leader survival. J Confl Resolut 54(1):58–87

Mashall MG, Gurr TR, Jaggers K (2014) Polity IV Project. Retrieved from: http://www.systemicpeace.org/inscrdata.html

Mavromatis T (2007) Drought index evaluation for assessing future wheat production in Greece. Int J Climatol 27(7):911–924. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.1444

McLeman R, Smit B (2006) Migration as an adaptation to climate change. Clim Chang 76(1–2):31–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-005-9000-7

Mishra AK, Singh VP (2010) A review of drought concepts. J Hydrol 391(1–2):202–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2010.07.012

Mishra AK, Singh VP (2011) Drought modeling – a review. J Hydrol 403(1–2):157–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2011.03.049

Morrison KM (2009) Oil, nontax revenue, and the Redistributional foundations of regime stability. Int Organ 63(1):107–138

Neumayer E, Plümper T, Barthel F (2014) The political economy of natural disaster damage. Glob Environ Chang 24(supplement C):8–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.03.011

Palmer WC (1965) Meteorological drought, vol 30. US Department of Commerce, Weather Bureau, Washington, DC

Perch-Nielsen S, Bättig M, Imboden D (2008) Exploring the link between climate change and migration. Clim Chang 91(3–4):375–393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-008-9416-y

Prudhomme C, Giuntoli I, Robinson EL, Clark DB, Arnell NW, Dankers R et al (2014) Hydrological droughts in the 21st century, hotspots and uncertainties from a global multimodel ensemble experiment. Proc Natl Acad Sci 111(9):3262–3267. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1222473110

Przeworski A, Alvarez ME, Cheibub JA Limongi F (2000) Democracy and development: political institutions and well-being in the world. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 1950–1990

Reyna SP (2010) The disasters of war in Darfur, 1950–2004. Third World Q 31(8):1297–1320. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2010.541083

Ross ML (2001) Does oil hinder democracy? World Polit 53(3):325–361

Sá C, Dismuke CE, Guimarães P (2007) Survival analysis and competing risk models of hospital length of stay and discharge destination: the effect of distributional assumptions. Health Serv Outcome Res Methodol 7(3):109–124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10742-007-0020-9

Satagopan JM, Ben-Porat L, Berwick M, Robson M, Kutler D, Auerbach AD (2004) A note on competing risks in survival data analysis. Br J Cancer 91(7):1229–1235. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6602102

Solow AR (2013) Global warming: a call for peace on climate and conflict. Nature 497(7448):179–180. https://doi.org/10.1038/497179a

StataCorp (2015) STATA survival analysis reference manual release 14. Stata Press, College Station

Steinwand MC (2014) Foreign aid and political stability. Conflict Manag Peace Sci. https://doi.org/10.1177/0738894214541227

Svoboda M, LeComte D, Hayes M, Heim R, Gleason K, Angel J et al (2002) The drought monitor. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 83(8):1181–1190

Taylor KE, Stouffer RJ, Meehl GA (2011) An overview of CMIP5 and the experiment design. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 93(4):485–498. https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-11-00094.1

Thornthwaite CW (1948) An approach toward a rational classification of climate. Geogr Rev 38(1):55–94. https://doi.org/10.2307/210739

Tobert N (1985) The effect of drought among the Zaghawa in northern Darfur. Disasters 9(3):213–223

UNFCCC COP (2015) Adoption of the Paris agreement. United Nations Office at Geneva, Geneva

United Nations, D. o. E. a. S. A., Population Division (2013) World population prospects: the 2012 Revision. Retrieved from: http://esa.un.org/wpp/Excel-Data/population.htm

Vicente-Serrano SM, Beguería S, López-Moreno JI (2009) A multiscalar drought index sensitive to global warming: the standardized precipitation evapotranspiration index. J Clim 23(7):1696–1718. https://doi.org/10.1175/2009JCLI2909.1

Wolbers M, Koller MT, Stel VS, Schaer B, Jager KJ, Leffondré K, Heinze G (2014) Competing risks analyses: objectives and approaches. Eur Heart J 35(42):2936–2941

Acknowledgments

This project is funded by the National Science Foundation award #0940822. An earlier version of the paper was presented at American Political Science Association 2015 annual meeting in San Francisco, CA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The authors are listed alphabetically. T.X., M.Z., and O.S. generated the climate data. O.S. and M.S. performed data analysis and wrote the paper.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 29 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Smirnov, O., Steinwand, M.C., Xiao, T. et al. Climate Impacts, Political Institutions, and Leader Survival: Effects of Droughts and Flooding Precipitation. EconDisCliCha 2, 181–201 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41885-018-0024-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41885-018-0024-7