Abstract

We review the measurement methods and thickness characterization algorithms of semiconductor multilayer devices. Today’s ultrahigh-density, high-energy-efficient three-dimensional semiconductor devices require an iterative semiconductor layer-stacking process. Accurate determination of nanometer-scale layer thickness is crucial for reliable semiconductor device fabrication. In this paper, we first review the commonly used semiconductor multilayer thickness measurement methods, including destructive and nondestructive measurement methods. Next, we review two approaches for thickness characterization: model-based algorithms using a physical interpretation of multilayer structures and a method using data-driven machine learning. With the growing importance of semiconductor multilayer devices, we anticipate that this study will help in selecting the most appropriate method for multilayer thickness characterization.

Highlights

-

This paper covers various measurement methods and algorithms to detect the thickness of semiconductor multilayer devices.

-

Model-based algorithm is suitable for cases where the number of layers is small or physical interpretation is required.

-

Machine learning performs well for thickness characterization of multilayer devices without complex physical analysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Since the first microprocessor was commercialized in 1971 [1], the semiconductor industry has focused on making smaller transistors to increase the density of integrated circuits. Roughly following Moore’s law [2, 3], the number of transistors in a single device has increased from only ~ 2300 in 1971 to more than 100 billion at present. However, continuing to reduce the size of transistors according to Moore’s law reaches its physical [4, 5] and technical limits [6] as the channel length (spacing between source and drain electrodes) is reduced to less than 10 nm.

Instead of planar scaling, to increase the integration density of semiconductor devices, the semiconductor industry is choosing a three-dimensional (3D) manufacturing strategy [7], which has the advantages of high capacity and high energy efficiency. The manufacture of 3D semiconductor devices is accompanied by vertical layer-stacking technologies such as monolithic [8] or heterogeneous integration [9]. Layer materials used for semiconductor multilayer devices vary depending on the purpose. For example, for the gate electrode configuration called a metal oxide semiconductor [10], an oxide layer such as SiO2 is commonly used as an insulating layer, and a polysilicon or metallic material is used as a conductive layer. Depending on the purpose, the number of layers can range from a few to hundreds. For example, 3D NAND flash memories [11,12,13] (3D NANDs) have higher storage capacity than conventional planar charge trap flash by vertically stacking the semiconductor materials by more than 200 layers.

The fabrication process of 3D semiconductor multilayer devices has benefited from advances in existing thin film deposition techniques [14]. These techniques have developed rapidly since the 1930s, as the need for optical thin film coating, particularly for military applications, is substantial. The development of vacuum evaporation [15] and magnetron sputtering [16] was accelerated by the invention of oil diffusion pumps [17] in the 1930s. Chemical vapor deposition (CVD) [18] and atomic layer deposition (ALD) [19, 20] technologies were discovered in the 1960s and remain widely used to deposit very thin layers in semiconductor facilities.

Nanometer-thick multilayer devices made of semiconductor materials include 3D NANDs [11,12,13, 21], transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) [22,23,24,25,26,27], graphene multilayer devices [28,29,30], and dispersive mirrors [31,32,33,34,35]. Table 1 provides commonly used materials, the number of layers, layer thickness, potential defects, measurement methods, and applications for each semiconductor multilayer device. Residual stresses during thin film deposition can cause unwanted thickness variations in the finished product [36]. Accurate measurements of the layer thickness of these devices are important for the reliable electrical performance of the finished product.

To date, several multilayer thickness metrology methods for 3D semiconductor devices have been proposed [37, 38]. Figure 1 briefly shows commonly used measurement methods depending on the target thickness of the layer. In this paper, we focus on reviewing the measurement methods and algorithms for nanometer-scale multilayer semiconductor devices. Table 2 compares nanometer-scale semiconductor multilayer thickness measurement methods. The thickness resolution of the optical methods depends on the layer thickness, the number of layers, and the measuring method. For example, in situ measurements show higher accuracy than ex situ measurements [39], and the thickness error increases with the thickness of the layer [40]. Electron microscopy [41,42,43,44] has the advantages of high magnification and high spatial resolution of < 0.1 nm; however, because of its destructive nature, the wafer-cutting process is required to measure the cross sections of the multilayer devices. Spectrophotometry [45, 46] is a nondestructive, noncontact method that can determine the thickness with a subnanometer resolution by exploiting the reflection, absorption, and transmission properties of light in light–matter interactions. Spectroscopic ellipsometry [47,48,49] is widely used for multilayer thickness characterization by simultaneously measuring the amplitude and phase change of the polarization state of the reflected light from a target sample. Raman spectroscopy [50,51,52] can observe the chemical and structural characteristics of multilayers by detecting scattered light. Ultrasound [53, 54] can be used for multilayer thickness characterization, but because of its relatively long wavelength (typically sub-mm scale), it is not suitable for analyzing nanometer-scale multilayer devices. White-light interferometry (WLI) [55,56,57] has been used to measure relatively thick layers of > 1 μm. WLI-based thin film thickness measurement is limited to transparent materials and is not suitable for nanometer-scale thin film devices because of its low phase sensitivity [58].

Optical approaches are accompanied by characterization algorithms [59,60,61,62,63] to determine the thickness of a multilayer. Model-based or machine learning algorithms [64] can be used as the characterization algorithm. Model-based algorithms find unknown sample parameters (thickness or refractive index) by comparing the calculated optical responses (reflectance or transmittance) based on optical modeling with the measured ones. Machine learning, which is a data-driven algorithm, automatically learns the correlation between unknown sample parameters and optical responses without accurate multilayer structural modeling.

In Sect. 2, methods commonly used for semiconductor multilayer devices, namely, electron microscopy, spectrophotometry, spectroscopic ellipsometry, and Raman spectroscopy, are reviewed, and in Sect. 3, algorithms commonly used for semiconductor multilayer devices are reviewed.

2 Multilayer Device Measurement Methods

2.1 Electron Microscopy

The working principle of electron microscopy [65] is to detect and analyze scattered or transmitted electrons resulting from electron–matter interactions. The highest resolution of today’s electron microscopy has reached the sub-angstrom scale [66], which is limited by noise such as thermal, drift, and lens aberrations [67, 68].

The high-resolution capabilities of electron microscopy are exploited in semiconductor device manufacturing facilities to measure the nanometer-scale thickness of semiconductor multilayers [69, 70]. Electron microscopy commonly used for semiconductor metrology includes critical dimension scanning electron microscopy (CD-SEM) [41] and scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) [71].

SEM detects secondary and backscattered electrons produced by electron–matter interactions to determine interlayer boundaries from changes in signal intensity according to the composite materials of the multilayer. In particular, CD-SEM [72, 73] is specialized in the dimensional metrology of semiconductor devices. To avoid damaging the sample, electrons are accelerated at a low energy of < 1 keV, and fast and accurate stages for the semiconductor wafer are inserted in the CD-SEM instrument. The resolution of commonly used CD-SEM is < 1 nm, determined by the electron-optical system. CD-SEM does not require special sample preparation [74], such as TEM, which requires thin sections of a specimen and has the advantage of having a wider FOV than TEM.

Figure 2a shows the thickness characterization results of the oxide films of 3D NAND using CD-SEM [75]. Because the oxide–nitride-blocking oxide (ONO) film thickness surrounding the vertical channel of 3D NAND is related to the data retention rate in the final products, precise thickness measurement is required. The diameter of each layer is determined by the difference in brightness between different media, and the layer thickness of ~ 10 nm is determined by the difference in diameter before and after deposition. In this paper, CD-SEM can measure the ONO film thickness with a precision of 0.08 nm.

Representative examples of electron microscopy used for semiconductor multilayer thickness characterization. a CD-SEM images of ONO films for 3D NAND devices. Reproduced with permission from [75]. Copyright 2018 Society of Photo-Optical Instrumentation Engineers (SPIE). b CD-SEM analysis for defect detection using machine learning. Reproduced with permission from [76]. Copyright 2021 Society of Photo-Optical Instrumentation Engineers (SPIE). c Cross-sectional STEM images of vertically stacked MoS2–WS2 multilayer devices. Reproduced from [80] with permission from Kang K. et al., Layer-by-layer assembly of two-dimensional materials into wafer-scale heterostructures, Nature, 550, 229–233, 2017, Springer Nature. d In situ STEM images showing the evolution of the a-TiOxNy layer. Reproduced from [81] with permission of Royal Society of Chemistry, from in situ TEM observation on the interface-type resistive switching by electrochemical redox reactions at a TiN/PCMO interface, Baek K. et al., 9, 582–593, 2017; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

Machine learning is used to improve the imaging speed of CD-SEM [76]. Figure 2b shows the fast detection of defects in periodic patterned images of 36-nm pitch with the help of machine learning. Machine learning is used to reduce the imaging time from 20 h/mm2 with conventional CD-SEM imaging to 1.25 h/mm2. By training a machine learning model with a rapidly acquired low-resolution image as input and a slowly acquired high-resolution image as output, a trained machine learning model can quickly detect defects at high resolution with rapidly acquired low-resolution images.

STEM [77,78,79] enables subangstrom resolution imaging by scanning a nanometer-sized electron beam point by point on a target sample. Scattered electrons transmitted through the sample are collected by an annular-shaped detector at the back focal plane of the objective lens. With the intensity variation of the scattered electron proportional to the square of the atomic number, the material properties and thickness can be characterized. The resolution of STEM has reached ~ 0.05 nm [66] but has the disadvantage of limited FOV and the need to prepare very thin sections of specimens, typically approximately 100 nm thick, for high resolution.

STEM can be used to verify the deposition state of stacked layers of ultrathin semiconductor films [80,81,82]. Figure 2c shows TMD films measured with angstrom precision by STEM [80]. An interlayer distance of 6.4 Å is distinguished. In situ TEM measurements can be used to observe real-time growth or shrinkage of the few-nanometer intermediate reaction layer of neuromorphic multilayer devices [81], as shown in Fig. 2d. They directly visualized the electrochemical redox processes by in situ TEM imaging.

Electron microscopy is widely used in semiconductor manufacturing processes due to its high resolution; however, it is not suitable for total inspection because it requires a wafer-cutting process. Compared to optical approaches, electron microscopy typically has a narrow FOV of 10–100 nm and requires tedious sample preparation processes, such as focused ion beam milling [83] in the case of TEM.

2.2 Spectrophotometry

Spectrophotometry [45, 46] is the quantitative measurement of transmitted or reflected light as a function of wavelength resulting from light–matter interactions over a wide wavelength range. The ratio of the intensity between the reference (a portion of a light source or reference mirror) and the measured (light interacting with the thin film materials) depends on the layer thickness and the refractive index of the thin film devices. Single or multiple photometers can be used to detect intensity changes. In general, the spectral range of ultraviolet to near-infrared light is used for spectrophotometers, but recently, the spectral range of extreme ultraviolet light (from 10 to 124 nm) has also been used [84,85,86,87] to measure semiconductor devices with a thickness of a few nanometers.

Spectrophotometry is noninvasive, nondestructive, simple, and requires no special sample preparation. However, spectrophotometry has a drawback when measuring highly absorbing media such as metallic materials in the visible range. Compared to spectroscopic ellipsometry, spectrophotometry has better spatial resolution because it does not necessarily require the beam to be incident on the sample at an oblique incident angle, but the optical information is limited to the amplitude change, while ellipsometry obtains the amplitude and phase change of the polarization state with a single measurement.

Thickness characterization by spectrophotometry is an indirect method that requires appropriate optical modeling and optimization algorithms to determine the layer thickness from the measured optical responses. Sample parameters such as the thickness or refractive index of each layer are determined by the optical fitting methods [88, 89], which compare the measured spectra with the simulated ones. For the optical modeling of multilayer devices, the transfer matrix method (TMM) [14] based on the continuity of electromagnetic waves passing through a thin film can be used. The electric and magnetic fields in the vertical direction (the direction in which the thin films are stacked) at the interface of the thin film system can be expressed as a characteristic matrix, as shown in the following equation [14]:

where Et (Eb) and Ht (Hb) are the electric and magnetic fields of the upper (lower) boundary of the layer, respectively. The phase shift δ is expressed as 2πNdcosθ/λ, where N, d, θ, and λ are the complex index of refraction, the thickness of the layer, the incident angle of light, and the wavelength of light, respectively. η is the optical admittance, which represents the ratio of the magnetic field to the electric field. The transfer matrix for multiple layers can be expressed as the following equation by extending Eq. (1):

The number of layers is m, and the optical admittance of the substrate is ηs. B and C are the normalized electric and magnetic fields, respectively. Thus, the reflectance (R), transmittance (T), and absorption (A) of the multilayer thin film system can be expressed as the following equations:

The calculated reflectance or transmittance can be compared to the measured values to characterize the optimal thickness or refractive index of each layer. The most commonly used metric for evaluating the goodness of fit is the mean squared error (MSE), as shown in the following equation:

where σ is the error bar of the measurements, N is the number of measurements, and M is the fit coefficient.

To increase the sensitivity of the measured signal from the targeted thin film, differential reflectance spectroscopy (DRS) [90,91,92] can be used. Differential reflectance (DR) can be expressed as DR = (R1 − R2)/R2, where R1 and R2 are the reflectance of the target and the reference, respectively. When a medium similar to the substrate of the target thin film is used as a reference sample, the target layer thickness can be measured with subnanometer precision. Figure 3a shows the DR spectra of thin film devices used as display panels [90]. In this study, the thickness of a ~ 10-nm-thick silicon layer is determined with 0.3-nm precision.

Representative examples of spectrophotometry. a Experimental setup and optical fitting results of differential reflectometry. Reprinted with permission from [90]. © The Optical Society. b Schematic of angle-resolved spectral reflectometry and a comparison of the measured and calculated angle-dependent reflectance. Reprinted with permission from [94]. © The Optical Society

To increase the amount of measurement information, multiangle [93, 94] or multisample [95] measurements can be used. Substantial changes in the reflectance spectra by changing the angle of incidence can provide new information. Measuring multiple samples with fixed optical constants of the target sample can also provide additional information. The additional information can improve the accuracy and uniqueness of thickness characterization [49]. Figure 3b shows multiangle reflectometry [94] using a digital micromirror device. The reflectance spectrum from the target sample changes with the angle of incidence from 0 to ~ 70°. Thus, a ~ 210 to 250-nm-thick layer was characterized with a combined uncertainty of 0.43 nm.

Machine learning can be used to reduce the characterization time or replace complex optical modeling [40, 96, 97]. Figure 4a shows the use of a thin film neural network [96] for the optical design and characterization of a multilayer of 232 layers. Using a trained machine learning model greatly reduced the computation time for thickness characterization. This thin film neural network takes ~ 0.924 s to optically model 232 layers, which is ~ 73-fold faster than the conventional framework (~ 67.5 s).

Representative examples of recent spectrophotometry for semiconductor multilayer thickness characterization. a Conceptual diagram of a thin film neural network and optical fitting results of 232 layers. Reproduced from [96] under the terms of creative common license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/. b 3D nanostructure characterization results of EUV imaging reflectometry. Reproduced from [85] under the terms of creative common license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/

As the structure of 3D integrated circuits is reduced to nanometer size, reflectometry in the extreme ultraviolet (EUV) region [84,85,86,87] can be used to measure nanoscale features. The wavelength range of EUV light generated by high harmonic generation is ~ 10 to 100 nm, which has the advantage of nanoscale spatial resolution. In addition, EUV light can penetrate metallic materials such as copper or aluminum, which is opaque in the visible range. Figure 4b shows the surface topographic imaging and thickness characterization of the SiO2-doped microstructures by EUV phase-sensitive reflectometry [85]. A SiO2 layer thickness of a few nanometers was characterized with 0.3-nm precision.

2.3 Spectroscopic Ellipsometry

One of the most widely used multilayer characterization methods, spectroscopic ellipsometry [47,48,49, 98], measures the changes in the polarization state of reflected or transmitted light from target samples. The main advantage of ellipsometry is in acquiring two pieces of optical information simultaneously by measuring the amplitude (ψ) and phase difference (Δ) of the polarization change with a rotating polarizer or analyzer (another polarizer before the detector) unit. Because ellipsometry irradiates light on the target device at an oblique angle, lateral resolution can be limited by several micrometers. Spectroscopic ellipsometry uses a mechanically rotating polarizer to obtain the change in polarization state over time. Therefore, it is vulnerable to mechanical vibration and takes several milliseconds to acquire single measurement data.

Similar to spectrophotometry, conventional ellipsometry also indirectly characterizes sample parameters with accurate optical modeling of the multilayer structure. The reflection coefficient of s- and p-polarized light is expressed as the following equation:

where rs and rp are the Fresnel coefficients of s- and p-polarized reflections, respectively, which are functions of thickness and refractive index. ψ and Δ can be derived with s- and p-polarized reflection coefficients calculated by the TMM. The thickness and refractive index of a thin film are determined when the MSE between the measured and calculated values is minimized, as shown by the following equation:

where σ is the error bar of the measurements, N is the number of measurements, and M is the fit coefficient.

Unfortunately, ψ and Δ values measured from single-wavelength ellipsometry do not provide a unique multilayer thickness solution. Thus, ellipsometry is often accompanied by multiangle [99,100,101] or multisample [102, 103] measurements. Multiangle or multisample measurement data help improve the uniqueness of characterization results by providing more information about the sample. Reducing the number of unknown parameters (such as layer thicknesses or refractive indices) can also help improve the accuracy and uniqueness of the characterization results. For example, by introducing a tooling factor that linearly fits the multilayer thickness change tendency in the layer deposition process [104], the number of fitting parameters required for characterization can be substantially reduced (from 37 to 2). Figure 5a shows the thickness characterization results of a 37-layer SiO2–Ta2O5 stack with a relative thickness error of < 2% compared to the target design. In this study, complex refractive indices can be estimated using the dispersion model [105, 106].

Representative examples of recent spectroscopic ellipsometry for semiconductor multilayer thickness characterization. a Optical fitting results of spectroscopic ellipsometric data using a tooling factor for each material. Reprinted from Surf Coat Technol, 357, Hilfiker J. N. et al., Spectroscopic ellipsometry characterization of multilayer optical coatings, 114–121, Copyright 2019, with permission from Elsevier [104]. b Experimental setup of dual-comb spectroscopic ellipsometry. Reproduced from [107] under the terms of creative common license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/. c Representative examples of layer thickness prediction results using machine learning. Reproduced from [108] under the terms of creative common license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/

Dual-comb ellipsometry [107] has been reported to improve the spectral resolution of spectroscopic ellipsometry, as shown in Fig. 5b. Dual-comb spectroscopy uses two optical frequency combs with slightly different repetition rates to acquire an interferogram in a wide time span without mechanical scanning. By exploiting this feature, s- and p-polarized interferograms between the signal comb and local comb can be obtained with two independent photodetectors, respectively. As one of the experimental results, the high spectral resolution of dual-comb spectroscopy can provide better thickness characterization precision (3.3 nm) compared to that of conventional ellipsometry (12.1 nm). However, because the typical spectral bandwidth of an optical frequency comb is < 100 nm, dual-comb spectroscopy can provide only limited optical information for thin films compared to conventional spectroscopic ellipsometry. Therefore, an optical comb source with a wide wavelength range may be required.

Machine learning can be combined with spectroscopic ellipsometry [108,109,110,111] to replace complex optical modeling. The correlation between the thickness of each layer of multilayer and ellipsometric data can be automatically trained using machine learning. Figure 5c shows the thickness prediction results with more than 200 layers using a machine learning model [108]. Using the ellipsometric data as the input and the high-resolution thickness information measured by TEM as the output, the thickness of each layer can be predicted with an average root-mean-square error of ~ 1.6 Å. Additionally, machine learning can be used for optical design. Without complex physical interpretation of the thin film structures, the machine learning model predicts ellipsometric spectra based on the given refractive indices and thicknesses during the optimization process [110]. Thus, the optimization process ended faster with smaller MSE values than conventional spectroscopic ellipsometry tested for 15 thin film materials.

2.4 Raman Spectroscopy

Raman spectroscopy [50] can be used to characterize thin film devices by exploiting the change in the energy state of scattered light as it interacts with thin film material. Most of the scattered photons undergo elastic scattering (Rayleigh scattering) and very rarely do incident photons lose or gain energy (Raman scattering). The Raman shift is defined as the difference in frequency between the incident light and the scattered light. Because the Raman shift depends on the material and incident light, Raman spectroscopy can be used to identify unknown materials [112, 113]. Further, by carefully observing the change in the Raman shift spectrum (in terms of the height, width, and position of the peak), the layer thickness or number of layers can be determined [114,115,116,117,118,119]. For example, by observing the 1st-order Raman shift of crystalline silicon at 520 cm−1, the thickness of the silicon material grown during the deposition process can be monitored in real time [120]. Typically, Raman spectroscopy uses a continuous wave or pulsed laser, and the scattered light is collected by a lens and a highly sensitive photodetector array. Because most of the scattered light is in the regime of Rayleigh scattering, a notch filter or an edge pass filter should be used to filter it out.

Thin film characterization using Raman spectroscopy is an indirect method similar to other optical-based analyses. By fitting the calculated Raman shift to the measured one, the composition of a thin film can be determined, or the change in thickness can be characterized [121, 122]. The intensity of a Raman shift is proportional to a function of the intensity I0 and the frequency ν of the incident light as follows [50]:

where N is the number of scattering molecules, and α and Q are the polarizability and amplitude of the vibrational coordinate, respectively. The peak intensity of a Raman shift varies with the layer thickness. Figure 6a shows the peak intensity changes in a Raman shift while consecutively stacking MoS2 on SiO2–Si multilayer devices [115]. As the ~ 0.7-nm thick MoS2 layer is continuously stacked, the spectral information of the Raman shift (the peak position and distance from the adjacent peak position) continuously changes. With the fitting process, the MoS2 layer thickness can be determined with an accuracy of 10% of the nominal thickness. However, when the number of layers exceeds ~ 10, the sensitivity of peak position changes is substantially degraded. Therefore, thickness characterization using the peak intensity of the Raman shift is limited to < 10 layers. This restriction is one of the limitations of thickness characterization using Raman spectroscopy, where the peak intensity change is not monotonic when the number of layers or the thickness increases.

Representative examples of Raman spectroscopy for semiconductor multilayer thickness characterization: a MoS2 layers at layer numbers from 1 to 116. Reprinted with permission from [115]. Copyright 2012 American Chemical Society. b Exfoliated hBN layers at layer numbers from 3 to 20. Reproduced from [116] with permission of © IOP Publishing Ltd, from Low frequency Raman spectroscopy of few-atomic-layer thick hBN crystals, Stenger I. et al., 4, 031003, 2017; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

Low-frequency Raman spectroscopy [116, 123] can be used to determine the number of layers from the strong dependence of the low-frequency vibrational modes on the layer number. In the case of hBN-based 2D semiconductor devices [124], the stacking order and the number of layers of hBN are closely related to electrical characteristics. As shown in Fig. 6b, the low-frequency vibrational modes at < 100 cm−1 are strongly downshifted as the hBN thickness decreases. In contrast, the high-frequency vibrational mode near ~ 1350 cm−1 appears insensitive to thickness changes.

To increase the sensitivity of the Raman signal, interference enhancement [125, 126] by exploiting the multiple reflections occurring on the SiO2–Si substrate can be used. Typical graphene layers or TMDs are fabricated on a Si substrate with a capping layer of silicon oxide several hundred nanometers thick. The Raman signal with interference enhancement can be detected with high sensitivity with up to a 30-fold enhancement factor [125]. However, multiple reflections from the SiO2–Si stack lead to ambiguity in the peak intensity of the Raman shift as the layer thickness increases.

Raman spectroscopy is widely used to detect the structural, chemical, and electrical properties of semiconductor multilayer devices in inspection facilities. Micro-Raman spectroscopy [120, 121, 127] can be used to analyze a local target area with high resolution and a small spot size by applying a microscopic system. Information from Raman spectroscopic studies includes electron/hole doping concentration [128], material composition [112, 113], stress and strain [52, 127], crystal orientation [129], and layer thickness and number [114,115,116,117,118,119]. With these versatile applications, Raman spectroscopy is commonly used to analyze the 2D semiconductor multilayer devices of emerging next-generation semiconductor materials such as graphene, hBN, and MoS2. However, because a Raman spectrum contains insufficient information for use in the multilayer characterization of semiconductors of hundreds of layers, it is mainly used for layer characterization of a few nanometers in thickness, with < 10 layers.

3 Multilayer Device Characterization Algorithms

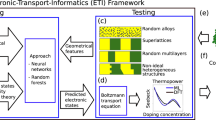

A determination of layer thickness with multilayer device measurements involves the use of appropriate algorithms. Model-based algorithms [59,60,61,62,63] include optical modeling and optical parameter optimization. Machine learning can be used for hidden physics modeling, direct characterization, and image classification. The operating principles for both categories are depicted in Fig. 7.

Figure 7a shows the operating principle of the model-based algorithm. Optical modeling requires the thickness and refractive index information of the target multilayer device to be set as initial values. The refractive index of the layer can be estimated with various dispersion models [63, 105, 130,131,132] depending on the medium. The modeled optical spectrum is compared with the measured spectrum using an optimization algorithm [133,134,135,136]. During the optimization process, the objective function minimizes, for example, the MSE between the measured and the modeled values. With repeated iterations, the updated sample parameters generate new modeled optical responses and are compared with the measured values again. When the MSE is minimized, the optimization process stops, and optimal sample parameters are determined.

Figure 7b shows the operating principle of machine learning. Machine learning only focuses on finding the correlation between the measured optical responses and the desired sample parameters. As a representative type of machine learning, supervised learning can be exploited for thickness characterization. The operating principle is as follows. First, in the training process, the machine learning model is trained with the measured optical responses as an input and the thickness information as an output. “Training” means optimizing the weight parameters of the machine learning model that best represents the input–output relationship. Various machine learning models, such as ridge regression [137], artificial neural networks [138], convolution neural networks [139], and support vector machines [140], can be used to train the labeled data. Second, in the prediction process, optical responses measured for unseen multilayer devices are applied to the trained model to predict thickness.

This section compares the commonly used methods for each algorithm to select the right one for a given problem.

3.1 Model-Based Algorithm

Determining the sample parameters of thin film devices involves estimating the “causes” (the thickness and refractive index of the target multilayer) from the “results” (the measured optical spectrum), which is called solving the optical inverse problem [14, 61]. The process of matching the modeled values with the estimated sample parameters to the measured values is called “fitting.” The accuracy and uniqueness of the solutions (sample parameters) are inevitably affected by measurement and numerical errors [49, 62]. An optical model is designed based on the initial values of the sample parameters. For example, optical responses (such as reflectance and transmittance) can be calculated by the TMM with multilayer thickness and refractive index information. An initial value of thickness can be assigned based on preliminary knowledge, and an initial value of the refractive index can be assigned using optical dispersion models. Sample parameters are updated until the calculated optical responses best fit the measured ones. To evaluate the goodness of fit, for example, the MSE between calculated and measured values can be used. To update and evaluate the optical model, optimization algorithms such as the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm [135], gradient descent [133], the Gauss–Newton algorithm [134], and genetic algorithms [136] are commonly used for thin film characterization.

To estimate the refractive index, the Sellmeier equation [106], Cauchy’s equation [131], and the Tauc–Lorentz model [132] can be used. Sellmeier and Cauchy’s equations are the empirical relation of the refractive index with respect to the wavelength and are mainly used to model the refractive index of transparent media such as fused silica in the visible range. The difference between Sellmeier and Cauchy’s equations is that the former equation fits better in the infrared wavelength range, and the latter equation has a simpler form. The general formulas for both methods are as follows:

where n is the refractive index, λ is the wavelength of the light, and A, B, and C are the fitting coefficients. To model the complex refractive index of absorbing media, the Tauc–Lorentz model can be used. The Tauc–Lorentz model expresses the complex relative permittivity with the following formula:

where ε is the relative permittivity, E is the photon energy, ε(∞) is the relative permittivity at infinite energy, and χ is the electric susceptibility. The complex refractive index can be derived from the complex relative permittivity with the equations below:

where n and κ are the real and imaginary parts of the refractive index, respectively. Modeling the refractive index can improve the accuracy and uniqueness of thickness characterization by reducing the unknown parameters of the optical inverse problem.

The determination of sample parameters with an optimization process can be expressed as

where \(\hat{x}\) is the optimized sample parameter, and F(x) is the objective function such as \(F\left( x \right) = \sum \left[ {y_{{{\text{mea}}}} - y_{\bmod } \left( x \right)} \right]^{2}\), where ymea and ymod are measured and modeled curves, respectively. Optimization algorithms differ in how they treat the objective function to update parameters in the iterative optimization process. Gradient descent finds the local minima in the opposite direction of the derivative of the objective function. The Gauss–Newton algorithm can approach the local minima faster and more accurately than gradient descent by considering not only the gradient but also the second derivative of the objective function, but the calculation of the second derivative can lead to numerical instability. The Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm is a combination of gradient descent and the Gauss–Newton algorithm. The Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm behaves like gradient descent when parameters are far from the local minima and behaves like a Gauss–Newton algorithm when they get close.

A genetic algorithm is a search algorithm inspired by the theory of natural selection. A genetic algorithm optimizes sets of sample parameters at once in one iteration. These parameter sets are called a “population.” During the optimization process, among the initial population, a set of parameters with the smallest error between the model value and the measured value is “selected.” In the next iteration, the selected parameters are mixed with each other to create a new parameter set (this process is called “crossover”). Then, some of the parameters change randomly with low probability, and this process is called “mutation.” This process is repeated until the updated parameters yield optimal fitting results. A genetic algorithm is more likely to converge to the global optima compared with gradient methods, but it takes longer computation times because it requires calculating the objective function for all populations at every iteration.

Model-based algorithms have the advantages of not requiring a large number of samples, high interpretability of results, and the ability to set bounds on sample parameters. In the optimization process of model-based algorithms, setting the initial parameters is important, and sometimes incorrect initial parameters can cause the optimization to fail completely or take a long time. Furthermore, the computational speed of a model-based method should be considered because the optical modeling and optimization time increase with the number of layers.

3.2 Machine Learning

Machine learning is a data-driven algorithm that automatically detects patterns in data for decision-making. Machine learning is widely used in science and engineering, with strengths in pattern recognition, classification, prediction, and parameter optimization [141, 142]. Particularly in the field of ultrafast optics [143], machine learning algorithms are used for various purposes such as image reconstruction [144], optical parameter characterization [145], image classification [142, 146], and system self-optimization [147, 148].

Machine learning is divided into supervised learning, unsupervised learning, and reinforcement learning, depending on the approach [64]. Among these methods, supervised learning aims to train a parametric function that can map desired outputs from inputs. For the simplest example, the input vector \({\varvec{x}} = \left\{ {x_{1} ,x_{2} , \ldots ,x_{n} } \right\}\) can be optical responses for n wavelengths, and the desirable output vector \({\varvec{y}} = \left\{ {y_{1} ,y_{2} , \ldots ,y_{m} } \right\}\) can be the layer thickness of m layers. Then, the predicted output vector \(\hat{\user2{y}}\) is expressed as:

where w is the weight vector (variables updated every iteration), and b is the bias. As a representative objective function, one can evaluate the MSE:

where T is the total number of data. Machine learning uses a backpropagation algorithm [149] to update the weight vector at every iteration. Machine learning consumes most of the time to train the parametric function composed of weight vectors. However, because the trained machine learning model predicts the output through a simple matrix operation (matrix multiplication between the input matrix and the weight matrix) on new input data, the prediction time is very short (typically < 0.1 ms but dependent on the hardware used).

With the emergence of several techniques [137, 150, 151] to improve the algorithmic performances of machine learning and the improvement in the speed of processing large amounts of data using graphical processing units (GPUs) [152], machine learning has been effectively used in various fields. The gradient vanishing problem can be suppressed by the rectified linear unit activation function [150], and the overfitting problem is greatly suppressed by several regularization methods such as dropout [151], data augmentation [153, 154], and ridge regression [137]. Batch normalization [155] greatly reduces the overall training time by resolving the covariance shift problem of latent variables.

Compared to model-based algorithms, machine learning is advantageous because the computation time does not increase in proportion to the number of layers in a multilayer device, and accurate physical analysis of the multilayer device is not required. Because parameter optimization in machine learning is based on matrix multiplication, the computing time does not substantially increase even if the dimension of the predicted output increases. Given good quality data (data with good reproducibility), machine learning can effectively find correlations between input and the desired outputs without complex physical interpretation. With this advantage, for the early studies, machine learning algorithms were used to predict the ellipsometric spectrum using neural networks [109, 111]. Thin film neural networks have recently been used for effective thin film design [96]. Previously, careful optical modeling was required to design a thin film with the desired optical response. Thin film neural networks are more effective for multilayer device designs with > 200 layers. Machine learning yields better characterization results than conventional methods in optimizing the refractive index and thickness of thin layers in various media [110]. Moreover, machine learning can also be used for defect detection in inspection processes [76]. Supervised learning can be used to predict layer thicknesses of > 200 layers from spectroscopic ellipsometric data with a high resolution similar to TEM [108]. Furthermore, group delay dispersion (GDD) measured by scanning white-light interferometry [156] can be used as additional input data for supervised learning. GDD is the second derivative of the spectral phase change and is very sensitive to changes in thin film thickness. In [157], thickness characterization performance was improved by adding GDD to the input data for supervised learning.

The limitations of machine learning are that sufficient data (at least 100 or more) are required to train the model, and accurate prediction is difficult when the structure of the multilayer device differs from that used for training. Small data problems can be addressed by exploiting data augmentation [153, 154] or simulation data. Noise-injection-based data augmentation [108, 158, 159] effectively prevents model overfitting. In [108], faulty devices could be detected economically using simulation data instead of producing outlier samples that reflect all outlier cases. The no free lunch theorem [160] refers to the fact that a trained machine learning model that is optimized for a particular problem does not perform well for other problems. Thus, a machine learning model optimization process should always be performed according to the given problem. Therefore, in applications where the multilayer structure must be changed in various ways or the number of data is insufficient, a model-based method can be more economical.

An optical neural network (ONN) [96, 161,162,163] refers to performing neural network training and prediction in free space by exploiting the speed of light. The high transmission speed and low heat dissipation of optical communication can replace existing electronics-based computing systems. As thin film neural networks [96] are already being applied to multilayer analysis, ONN could potentially be applied to thin film design or characterization with ultrafast speed and high energy efficiencies.

4 Conclusions

We have reviewed commonly used measurement methods and algorithms for semiconductor multilayer devices. As the semiconductor industry demands more compact and more versatile 3D semiconductor devices, nanometer-scale semiconductor multilayer stacking technology is becoming critical. To date, destructive and nondestructive methods have been used complementary to each other for the thickness characterization of semiconductor multilayer devices. Optical approaches seek multi-variate, multi-sample measurements to achieve sub-nanometer-scale thickness characterization errors. Recently, data-driven machine learning has been used to accelerate characterization times or replace the complex physical interpretations of multilayer structures. The best combination of the measurement method and algorithm depends on the semiconductor multilayer device under testing. We expect that this review will be of great help in choosing an appropriate characterization method.

Availability of Data and Materials

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Faggin F (2018) How we made the microprocessor. Nat Electron 1:88–88

Moore GE (1998) Cramming more components onto integrated circuits. Proc IEEE 86:82–85

Lundstrom MS, Alam MA (2022) Moore’s law: the journey ahead. Science 378:722–723

Keyes RW (2005) Physical limits of silicon transistors and circuits. Rep Prog Phys 68:2701–2746

Wu JZ, Min J, Taur Y (2015) Short-channel effects in tunnel FETs. IEEE Trans Electron Devices 62:3019–3024

Levinson HJ (2022) High-NA EUV lithography: current status and outlook for the future. Jpn J Appl Phys 62:SD0803

Salahuddin S, Ni K, Datta S (2018) The era of hyper-scaling in electronics. Nat Electron 1:442–450

Vinet M et al (2011) 3D monolithic integration: technological challenges and electrical results. Microelectron Eng 88:331–335

Iyer SS (2016) Heterogeneous integration for performance and scaling. IEEE Trans Compon Pack Manuf Technol 6:973–982

Vadasz LL, Grove AS, Rowe TA, Moore GE (1969) Silicon-gate technology. IEEE Spectr 6:28–35

Kim H, Ahn S-J, Shin YG, Lee K, Jung E (2017) Evolution of NAND flash memory: from 2D to 3D as a storage market leader. IEEE International Memory Workshop (IMW), pp 1–4

Nitayama A, Aochi H (2011) Vertical 3D NAND flash memory technology. ECS Trans 41:15

Goda A (2021) Recent progress on 3D NAND flash technologies. Electronics 10:3156

Macleod HA (2010) Thin-film optical filters. CRC Press, Boca Raton

Bunshah R (1984) Vacuum evaporation-history, recent developments and applications. Int J Mater Res 75:840–846

Greene JE (2017) Tracing the recorded history of thin-film sputter deposition: from the 1800s to 2017. J Vac Sci Technol A Vac Surf Films 35:05C204

Zabel R (1935) A simple high speed oil diffusion pump. Rev Sci Instrum 6:54–55

Powell CF, Oxley JH, Blocher JM, Klerer J (1966) Vapor deposition. J Electrochem Soc 113:266C

Malygin AA, Drozd VE, Malkov AA, Smirnov VM (2015) From VB Aleskovskii’s “Framework” hypothesis to the method of molecular layering/atomic layer deposition. Chem Vapor Depos 21:216–240

Zhang J, Li Y, Cao K, Chen R (2022) Advances in atomic layer deposition. NanoManuf Metrol 5:191–208

Luo Y, Ghose S, Cai Y, Haratsch EF, Mutlu O (2018) Improving 3D NAND flash memory lifetime by tolerating early retention loss and process variation. J Proc ACM Meas Anal Comput Syst 2:1–48

Chen M-L et al (2020) A FinFET with one atomic layer channel. Nat Commun 11:1205

Chhowalla M, Liu Z, Zhang H (2015) Two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenide (TMD) nanosheets. Chem Soc Rev 44:2584–2586

Huang HH, Fan X, Singh DJ, Zheng WT (2020) Recent progress of TMD nanomaterials: phase transitions and applications. Nanoscale 12:1247–1268

Wang L et al (2018) 2D photovoltaic devices: progress and prospects. Small Methods 2:1700294

Lin Z et al (2016) Defect engineering of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. 2D Mater 3:022002

Romanov RI et al (2021) Thickness-dependent structural and electrical properties of WS(2) nanosheets obtained via the ALD-Grown WO(3) sulfurization technique as a channel material for field-effect transistors. ACS Omega 6:34429–34437

Ki Min B et al (2015) Electrical double layer capacitance in a graphene-embedded Al2O3 gate dielectric. Sci Rep 5:16001

Lin H, Lin KT, Yang T, Jia B (2021) Graphene multilayer photonic metamaterials: fundamentals and applications. Adv Mater Technol 6:2000963

Novoselov KS et al (2004) Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science 306:666–669

Chen R et al (2022) High-damage-threshold chirped mirrors for next-generation ultrafast, high-power laser systems. IEEE Photonics Technol Lett 34:93–96

Jasik A et al (2014) Design and fabrication of highly dispersive semiconductor double-chirped mirrors. Appl Phys B Lasers Opt 116:141–146

Pervak V, Razskazovskaya O, Angelov IB, Vodopyanov KL, Trubetskov M (2014) Dispersive mirror technology for ultrafast lasers in the range 220–4500 nm. Adv Opt Technol 3:55–63

Pervak V et al (2007) 1.5-octave chirped mirror for pulse compression down to sub-3 fs. Appl Phys B Lasers Opt 87:5–12

Wonisch A et al (2006) Design, fabrication, and analysis of chirped multilayer mirrors for reflection of extreme-ultraviolet attosecond pulses. Appl Opt 45:4147–4156

Sinha A, Levinstein H, Smith T (1978) Thermal stresses and cracking resistance of dielectric films (SiN, Si3N4, and SiO2) on Si substrates. J Appl Phys 49:2423–2426

Orji NG et al (2018) Metrology for the next generation of semiconductor devices. Nat Electron 1:532–547

Jin Y, Yu K (2021) A review of optics-based methods for thickness and surface characterization of two-dimensional materials. J Phys D Appl Phys 54:393001

Tsuru T, Tsutou T, Hatano T, Yamamoto M (2005) Accurate measurement of EUV multilayer period thicknesses by in situ automatic ellipsometry. J Electron Spectrosc Relat Phenom 144:1083–1085

Tian SIP et al (2020) Rapid and accurate thin film thickness extraction via UV–Vis and machine learning. In: 2020 47th IEEE photovoltaic specialists conference (PVSC) 0128-0132

Lorusso GF et al (2019) Electron beam metrology for advanced technology nodes. Jpn J Appl Phys 58:SD0801

Ophus C (2019) Four-dimensional scanning transmission electron microscopy (4D-STEM): from scanning nanodiffraction to ptychography and beyond. Microsc Microanal 25:563–582

Petford-Long AK, Chiaramonti AN (2008) Transmission electron microscopy of multilayer thin films. Ann Rev Mater Res 38:559–584

Shkurmanov A, Krekeler T, Ritter M (2022) Slice thickness optimization for the focused ion beam-scanning electron microscopy 3D tomography of hierarchical nanoporous gold. NanoManuf Metrol 5:112–118

Guo C, Kong M, Gao W, Li B (2013) Simultaneous determination of optical constants, thickness, and surface roughness of thin film from spectrophotometric measurements. Opt Lett 38:40–42

Ohlídal M, Vodák J, Nečas D (2018) Optical characterization of thin films by means of imaging spectroscopic reflectometry. In: Stenzel O, Ohlídal M (eds) Optical characterization of thin solid films. Springer, Cham, pp 107–141

Irene EA (1993) Applications of spectroscopic ellipsometry to microelectronics. Thin Solid Films 233:96–111

Woollam JA, Snyder PG (1990) Fundamentals and applications of variable angle spectroscopic ellipsometry. Mater Sci Eng: B 5:279–283

Hilfiker JN et al (2008) Survey of methods to characterize thin absorbing films with spectroscopic ellipsometry. Thin Solid Films 516:7979–7989

Orlando A et al (2021) A comprehensive review on Raman spectroscopy applications. Chemosensors 9:262

Yin Z et al (2021) Recent progress on two-dimensional layered materials for surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy and their applications. Mater Today Phys 18:100378

Ferrari AC, Basko DM (2013) Raman spectroscopy as a versatile tool for studying the properties of graphene. Nat Nanotechnol 8:235–246

Passeri D, Bettucci A, Rossi M (2010) Acoustics and atomic force microscopy for the mechanical characterization of thin films. Anal Bioanal Chem 396:2769–2783

Kanja J et al (2021) Non-contact measurement of the thickness of a surface film using a superimposed ultrasonic standing wave. Ultrasonics 110:106291

Kim M-G, Pahk H-J (2018) Fast and reliable measurement of thin film thickness profile based on wavelet transform in spectrally resolved white-light interferometry. Int J Precis Eng Manuf 19:213–219

Park J, Kim J-A, Ahn H, Bae J, Jin J (2019) A review of thickness measurements of thick transparent layers using optical interferometry. Int J Precis Eng Manuf 20:463–477

Ghim Y-S, Kim S-W (2006) Thin-film thickness profile and its refractive index measurements by dispersive white-light interferometry. Opt Express 14:11885–11891

Dong J-t, Lu R-s (2012) Sensitivity analysis of thin-film thickness measurement by vertical scanning white-light interferometry. Appl Opt 51:5668–5675

Tikhonravov AV, Trubetskov MK (2004) Online characterization and reoptimization of optical coatings. Adv Opt Thin Films Proc SPIE 5250:406–413

Price J, Hung PY, Rhoad T, Foran B, Diebold AC (2004) Spectroscopic ellipsometry characterization of HfxSiyOz films using the Cody–Lorentz parameterized model. Appl Phys Lett 85:1701–1703

Allgair JA et al (2009) An inverse ellipsometric problem for thin film characterization: comparison of different optimization methods. In: Metrology, inspection, and process control for microlithography XXIII (Proceedings of the SPIE), vol 7272, pp 1122–1128

Amotchkina TV, Trubetskov MK, Pervak V, Romanov B, Tikhonravov AV (2012) On the reliability of reverse engineering results. Appl Opt 51:5543–5551

Gao L, Lemarchand F, Lequime M (2011) Comparison of different dispersion models for single layer optical thin film index determination. Thin Solid Films 520:501–509

Murphy KP (2012) Machine learning: a probabilistic perspective. MIT Press

Egerton RF (2005) Physical principles of electron microscopy. Springer, New York

Erni R, Rossell MD, Kisielowski C, Dahmen U (2009) Atomic-resolution imaging with a sub-50-pm electron probe. Phys Rev Lett 102:096101

Egerton RF, Watanabe M (2022) Spatial resolution in transmission electron microscopy. Micron 160:103304

Uhlemann S, Muller H, Hartel P, Zach J, Haider M (2013) Thermal magnetic field noise limits resolution in transmission electron microscopy. Phys Rev Lett 111:046101

Stegmann H, Engelmann H-J, Zschech E (2006) Transmission electron microscopy in semiconductor manufacturing. Sci Technol Educ Microsc Overview 66:187–199

Shohjoh T et al (2021) Inspection and metrology challenges for 3 nm node devices and beyond. In: 2021 IEEE international electron devices meeting (IEDM) 3.3.1–3.3.4

Muller DA (2009) Structure and bonding at the atomic scale by scanning transmission electron microscopy. Nat Mater 8:263–270

Yoon J et al (2010) GaAs photovoltaics and optoelectronics using releasable multilayer epitaxial assemblies. Nature 465:329–333

Lu W et al (2017) 10-nm fin-width InGaSb p-channel self-aligned FinFETs using antimonide-compatible digital etch. In: 2017 IEEE international electron devices meeting (IEDM), 17.7.1–17.7.4

Zhang Z et al (2022) The trends of in situ focused ion beam technology: toward preparing transmission electron microscopy lamella and devices at the atomic scale. Adv Electron Mater 8:2101401

Ohashi T et al (2018) Precise measurement of thin-film thickness in 3D-NAND device with CD-SEM. J Micro-Nanolithogr MEMS MOEMS 17:024002. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.JMM.17.2.024002

Kondo T et al (2021) Massive metrology and inspection solution for EUV by area inspection SEM with machine learning technology. Metrol Inspect Process Control Semicond Manuf XXXV SPIE 11611:210–219. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2583691

Zhong Z et al (2017) Automated STEM/EDS metrology characterization of 3D NAND devices. Microsc Microanal 23:1458–1459

Anjum DH et al (2020) Nano-characterization of silicon-based multilayers using the technique of STEM-EELS spectrum-imaging. Mater Today Commun 25:101209

Yu WJ et al (2013) Vertically stacked multi-heterostructures of layered materials for logic transistors and complementary inverters. Nat Mater 12:246–252

Kang K et al (2017) Layer-by-layer assembly of two-dimensional materials into wafer-scale heterostructures. Nature 550:229–233. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature23905

Baek K et al (2017) In situ TEM observation on the interface-type resistive switching by electrochemical redox reactions at a TiN/PCMO interface. Nanoscale 9:582–593. https://doi.org/10.1039/c6nr06293h

Mendes RG et al (2019) Electron-driven in situ transmission electron microscopy of 2D transition metal dichalcogenides and their 2D heterostructures. ACS Nano 13:978–995

Giannuzzi LA, Stevie FA (1999) A review of focused ion beam milling techniques for TEM specimen preparation. Micron 30:197–204

Bodermann B, Wurm M, Diener A, Scholze F, Groß H (2009) EUV and DUV scatterometry for CD and edge profile metrology on EUV masks. In: 25th European mask and lithography conference, pp 1–12

Tanksalvala M et al (2021) Nondestructive, high-resolution, chemically specific 3D nanostructure characterization using phase-sensitive EUV imaging reflectometry. Sci Adv 7:eabd9667. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abd9667

Shanblatt ER et al (2016) Quantitative chemically specific coherent diffractive imaging of reactions at buried interfaces with few nanometer precision. Nano Lett 16:5444–5450. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b01864

Wiesner F et al (2022) Characterization of encapsulated graphene layers using extreme ultraviolet coherence tomography. Opt Express 30:32267–32279

McGahan WA, Johs B, Woollam JA (1993) Techniques for ellipsometric measurement of the thickness and optical constants of thin absorbing films. Thin Solid Films 234:443–446

Polgár O, Fried M, Lohner T, Bársony I (2000) Comparison of algorithms used for evaluation of ellipsometric measurements random search, genetic algorithms, simulated annealing and hill climbing graph-searches. Surf Sci 457:157–177

Huo S et al (2021) Measuring the multilayer silicon based microstructure using differential reflectance spectroscopy. Opt Express 29:3114–3122. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.414033

Forker R, Gruenewald M, Fritz T (2012) Optical differential reflectance spectroscopy on thin molecular films. Annu Rep Prog Chem Sect C Phys Chem 108:34–68

Qu J et al (2019) Evaporable glass-state molecule-assisted transfer of clean and intact graphene onto arbitrary substrates. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 11:16272–16279. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.8b21946

Ghim YS, Rhee HG (2019) Instantaneous thickness measurement of multilayer films by single-shot angle-resolved spectral reflectometry. Opt Lett 44:5418–5421

Choi G, Kim M, Kim J, Pahk HJ (2020) Angle-resolved spectral reflectometry with a digital light processing projector. Opt Express 28:26908–26921. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.405204

Amotchkina T, Trubetskov M, Janicki V, Sancho-Parramon J (2022) Reverse engineering of e-beam deposited optical filters based on multi-sample photometric and ellipsometric data. Appl Opt 62:B35–B42

Fan L et al (2021) Thin-film neural networks for optical inverse problem. Light Adv Manuf 2:395–402. https://doi.org/10.37188/lam.2021.027

Choi JE, Song J, Lee YH, Hong SJ (2020) Deep neural network modeling of multiple oxide/nitride deposited dielectric films for 3D-NAND flash. Appl Sci Converg Technol 29:190–194

Tsuru T, Yamamoto M (2008) Precise determination of layer structure with EUV ellipsometry data obtained by multilayer polarizing elements. Phys Status Solidi C 5:1129–1132

Politano GG, Versace C (2021) Variable-angle spectroscopic ellipsometry of graphene-based films. Coatings 11:462

Politano GG et al (2021) Variable angle spectroscopic ellipsometry characterization of spin-coated MoS2 films. Vacuum 189:110232

Rauch N et al (2022) A model for spectroscopic ellipsometry analysis of plasma-activated Si surfaces for direct wafer bonding. Appl Phys Lett 121:081603

Herzinger CM et al (1996) Studies of thin strained InAs, AlAs, and AlSb layers by spectroscopic ellipsometry. J Appl Phys 79:2663–2674

Herzinger CM et al (1995) Determination of AlAs optical constants by variable angle spectroscopic ellipsometry and a multisample analysis. J Appl Phys 77:4677–4687

Hilfiker JN, Pribil GK, Synowicki R, Martin AC, Hale JS (2019) Spectroscopic ellipsometry characterization of multilayer optical coatings. Surf Coat Technol 357:114–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2018.10.003

Budai J, Hanyecz I, Szilágyi E, Tóth Z (2011) Ellipsometric study of SixC films: analysis of Tauc–Lorentz and Gaussian oscillator models. Thin Solid Films 519:2985–2988

Paschotta R (2021) Sellmeier formula. Wiley, New York

Minamikawa T et al (2017) Dual-comb spectroscopic ellipsometry. Nat Commun 8:610. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-00709-y

Kwak H et al (2021) Non-destructive thickness characterisation of 3D multilayer semiconductor devices using optical spectral measurements and machine learning. Light Adv Manuf 2:9–19. https://doi.org/10.37188/lam.2021.001

Rédei L, Fried M, Bársony I, Wallinga H (1998) A modified learning strategy for neural networks to support spectroscopic ellipsometric data evaluation. Thin Solid Films 313:149–155

Liu J, Zhang D, Yu D, Ren M, Xu J (2021) Machine learning powered ellipsometry. Light Sci Appl 10:55

Fried M, Masa P (1994) Backpropagation (neural) networks for fast pre-evaluation of spectroscopic ellipsometric measurements. J Appl Phys 75:2194–2201

Vašková H (2011) A powerful tool for material identification: Raman spectroscopy. Int J Math Model Methods Appl Sci 5:1205–1212

Kumar N et al (2020) Phase-microstructure of Mo/Si nanoscale multilayer and intermetallic compound formation in interfaces. Intermetallics 125:106872

Wolverson D, Crampin S, Kazemi AS, Ilie A, Bending SJ (2014) Raman spectra of monolayer, few-layer, and bulk ReSe2: an anisotropic layered semiconductor. ACS Nano 8:11154–11164

Li S-L et al (2012) Quantitative Raman spectrum and reliable thickness identification for atomic layers on insulating substrates. ACS Nano 6:7381–7388. https://doi.org/10.1021/nn3025173

Stenger I et al (2017) Low frequency Raman spectroscopy of few-atomic-layer thick hBN crystals. 2D Mater 4:031003. https://doi.org/10.1088/2053-1583/aa77d4

Nong H et al (2022) Layer-dependent Raman spectroscopy and electronic applications of wide-bandgap 2D semiconductor beta-ZrNCl. Small 18:e2107490

No YS et al (2018) Layer number identification of CVD-grown multilayer graphene using Si peak analysis. Sci Rep 8:571

Hajiyev P, Cong C, Qiu C, Yu T (2013) Contrast and Raman spectroscopy study of single- and few-layered charge density wave material: 2H-TaSe(2). Sci Rep 3:2593

Jawhari T (2000) Micro-Raman spectroscopy of the solid state: applications to semiconductors and thin films. Analusis 28:15–21

Sadezky A, Muckenhuber H, Grothe H, Niessner R, Pöschl U (2005) Raman microspectroscopy of soot and related carbonaceous materials: spectral analysis and structural information. Carbon 43:1731–1742

Yuan X, Mayanovic RA (2017) An empirical study on Raman peak fitting and its application to Raman quantitative research. Appl Spectrosc 71:2325–2338

Liang L et al (2017) Low-frequency shear and layer-breathing modes in Raman scattering of two-dimensional materials. ACS Nano 11:11777–11802

Zhang K, Feng Y, Wang F, Yang Z, Wang J (2017) Two dimensional hexagonal boron nitride (2D-hBN): synthesis, properties and applications. J Mater Chem C 5:11992–12022

Wang Y, Ni Z, Shen Z, Wang H, Wu Y (2008) Interference enhancement of Raman signal of graphene. Appl Phys Lett 92:043121

Yoon D et al (2009) Interference effect on Raman spectrum of graphene onSiO2/Si. Phys Rev B 80:125422

Qiu W et al (2016) Measurement of residual stress in a multi-layer semiconductor heterostructure by micro-Raman spectroscopy. Acta Mech Sin 32:805–812

Duan X et al (2014) Lateral epitaxial growth of two-dimensional layered semiconductor heterojunctions. Nat Nanotechnol 9:1024–1030

Baranov AV et al (2004) Polarized Raman spectroscopy of multilayer Ge∕Si(001) quantum dot heterostructures. J Appl Phys 96:2857–2863

Tatian B (1984) Fitting refractive-index data with the Sellmeier dispersion formula. Appl Optics 23:4477–4485

Gooch JW (2007) Cauchy’s dispersion formula. Springer, New York

Jellison GE, Modine FA (1996) Parameterization of the optical functions of amorphous materials in the interband region. Appl Phys Lett 69:371–373

Ruder S (2016) An overview of gradient descent optimization algorithms. arXiv:1609.04747. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.41609.04747.

Ruhe A (1979) Accelerated Gauss-Newton algorithms for nonlinear least squares problems. BIT 19:356–367

Ranganathan A (2004) The Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm. Tutor LM Algorithm 11:101–110

Whitley D (1994) A genetic algorithm tutorial. Stat Comput 4:65–85

McDonald GC (2009) Ridge regression. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Comput Stat 1:93–100

Cheng B, Titterington DM (1994) Neural networks: a review from a statistical perspective. Stat Sci 9:2–30

Gu J et al (2018) Recent advances in convolutional neural networks. Pattern Recognit 77:354–377

Smola AJ, Schölkopf B (2004) A tutorial on support vector regression. Stat Comput 14:199–222

Silver D et al (2017) Mastering the game of Go without human knowledge. Nature 550:354–359

Chen CL et al (2016) Deep learning in label-free cell classification. Sci Rep 6:21471

Genty G et al (2021) Machine learning and applications in ultrafast photonics. Nat Photonics 15:91–101

Zahavy T et al (2018) Deep learning reconstruction of ultrashort pulses. Optica 5:666–673

Salmela L et al (2021) Predicting ultrafast nonlinear dynamics in fibre optics with a recurrent neural network. Nat Mach Intell 3:344–354

Ziletti A, Kumar D, Scheffler M, Ghiringhelli LM (2018) Insightful classification of crystal structures using deep learning. Nat Commun 9:2775

Tranter AD et al (2018) Multiparameter optimisation of a magneto-optical trap using deep learning. Nat Commun 9:4360

Teğin U et al (2020) Controlling spatiotemporal nonlinearities in multimode fibers with deep neural networks. APL Photonics 5:030804

Lillicrap TP, Santoro A, Marris L, Akerman CJ, Hinton G (2020) Backpropagation and the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci 21:335–346

Glorot X, Bordes A, Bengio Y (2011) Deep sparse rectifier neural networks. In: Proceedings of the fourteenth international conference on artificial intelligence and statistics, vol 15, pp 315–323

Srivastava N, Hinton G, Krizhevsky A, Sutskever I, Salakhutdinov R (2014) Dropout: a simple way to prevent neural networks from overfitting. J Mach Learn Res 15:1929–1958

Chen Z, Wang J, He H, Huang X (2014) A fast deep learning system using GPU. In: 2014 IEEE international symposium on circuits and systems (ISCAS), pp 1552–1555

Jiang YL, Zur RM, Pesce LL, Drukker K (2009) A study of the effect of noise injection on the training of artificial neural networks. In: IJCNN: 2009 international joint conference on neural networks, pp 1428–1432

Bae H-J et al (2018) A Perlin noise-based augmentation strategy for deep learning with small data samples of HRCT images. Sci Rep 8:17687

Ioffe S, Szegedy C (2015) Batch normalization: accelerating deep network training by reducing internal covariate shift. Int Conf Mach Learn 37:448–456

Amotchkina TV et al (2009) Measurement of group delay of dispersive mirrors with white-light interferometer. Appl Opt 48:949–956

Kwak H et al (2021) Angstrom-accuracy multilayer thickness determination using optical metrology and machine learning. Opt Meas Syst Ind Inspect XII 11782:178–182

Zur RM, Jiang Y, Pesce LL, Drukker K (2009) Noise injection for training artificial neural networks: a comparison with weight decay and early stopping. Med Phys 36:4810–4818

Zur R, Jiang Y, Metz CE (2004) Comparison of two methods of adding jitter to artificial neural network training. Int Congr Ser 1268:886–889

Wolpert DH, Macready WG (1997) No free lunch theorems for optimization. IEEE Trans Evol Comput 1:67–82

Sui X, Wu Q, Liu J, Chen Q, Gu G (2020) A review of optical neural networks. IEEE Access 8:70773–70783

Zhang H et al (2021) An optical neural chip for implementing complex-valued neural network. Nat Commun 12:457

Lin X et al (2018) All-optical machine learning using diffractive deep neural networks. Science 361:1004–1008

Funding

National Research Foundation of Korea (Grants 2021R1A2B5B03001407 and 2021R1A5A1032937).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JK conceived the idea for the article. HK performed the literature search and drafted the article. JK revised the article. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kwak, H., Kim, J. Semiconductor Multilayer Nanometrology with Machine Learning. Nanomanuf Metrol 6, 15 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41871-023-00193-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41871-023-00193-7