Abstract

The Jing-Wei Floodplain, located in Shaanxi, China, has been home to various groups of people over the last 5000 years. Drawing together evidence from archaeology, paleobotany, geomorphology, climate sciences, and history, this paper provides a longue durée study of the local (pre)history of human occupation in this area with a special focus on human adaptation strategies and environmental history. In particular, the study summarizes and evaluates archaeological and geomorphological field research conducted over the last ten years and connects it with often overlooked local historical accounts and recent climate research in the Wei River Valley and observations on recent economic developments and their impact on both the environment and the people living in it. In spite of a rather long hiatus in occupation from the second century BCE to the twelfth century CE, the evidence shows that there are close similarities in human-environment relations and even continuities into the modern period. Though being a highly localized study, this paper can serve as an example for how such longue durée studies may be conducted in other regions, and it provides some suggestions for future field and laboratory research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This paper addresses the environmental history and human adaptation strategies of a local community in Shaanxi 陕西, China, over the past 5000 years. This small-scale, nuanced study is meant to shed some light on the relationship between humans and their environment in this location but also provide an example for longue durée studies in other locations and some suggestions for future field and laboratory research.

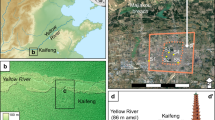

This paper focuses in particular on the Jing 泾 Wei 渭 floodplain around the archaeological site of Yangguanzhai 杨官寨 (YGZ), a large mid- to late Yangshao 仰韶 period (3500–3000 cal. BCE) village located in the central Wei River Valley on the first terrace of the Jing River. The Jing is the largest tributary of the Wei River and flows in from the north. More than ten years of fieldwork have revealed hundreds of features covering an area close to one square kilometer (Fig. 1). Located near one of China’s largest and most active river systems, the site was greatly affected by its immediate environment. Over the last ten years, about 20,000 square meters of excavation area have been exposed at YGZ, allowing some insights into the site structure, its history, and relationship with other Yangshao sites in the Wei River Valley (Shaanxi 2009; Shaanxi sheng 2009; Shaanxi sheng and Baishui xian 2011; Shaanxi sheng and Zhong Mei 2018; Wang and Lee 2010).

Jing-Wei Floodplain in Shaanxi showing the location of the Yangguanzhai Neolithic settlement, Ming cemeteries mentioned in the text, and the Zhengguo Canal (after Shaanxi sheng and Zhong Mei 2018: Fig. 1)

2 Prehistoric life on the Jing-Wei floodplain

The first known settlers of YGZ were farmers who lived in a village, ca. 4000–3000 BCE. The main settlement (usually referred to as Beiqu 北区, northern section) is surrounded by a trapezoidal ditch, averaging 2 to 4 m deep and 6 to 9 m wide, the widest part reaching 13 m.Footnote 1 This imposing ditch is the largest feature of the site, with a total length of approximately 1945 m. The area enclosed by the ditch is close to 24 ha in size (Fig. 2).

Outside the southern portion of the ditch, to the southwest of the Beiqu, is another settlement named Nanqu 南区 (south section) which borders on an ancient gully or river channel located on its southern side which contained thick sand deposits (personal communication by Zhang Pengcheng, Shaanxi Academy of Archaeology, 2012). It is unclear how the two settlements were related chronologically since a modern road cuts between them. As far as ceramic assemblages are concerned, the ditched area of Beiqu and the northern part of Nanqu contained mostly Yangshao ceramics of Miaodigou 庙底沟 style (ca. 3500–3300 BCE), while the rest of Nanqu is characterized by Yangshao ceramics of Banpo 半坡 IV style (ca. 3300–3000 BCE), the latest phase of the Yangshao period. So far, the stratigraphy at both sections reveals no overlap of the two cultural phases, and it is difficult to say how the transition of ceramic styles took place at YGZ, i.e., if there was a temporal rupture, abrupt transition, or gradual transformation (Shaanxi sheng 2009).

In addition to the prominent ditches, the features discovered at YGZ include semi-subterranean dwellings, other types of houses, postholes, hearths, kilns, child burials, pits of various types, ditches for water drainage, and there is also a single pond. Among these, pits account for over 80% of all excavated Neolithic features. Historic remains and artifacts were also found, including tombs from various periods, water canals, a brick and tile kiln, and trash deposits, which will be discussed below.

About 400 m east of the ditched settlement is a Miaodigou period cemetery. Surveys show that it extends over about 9 ha, measuring 530 m from east to west, and 170 m from north to south. Archaeologists have identified 343 Miaodigou tombs (Shaanxi sheng 2018a) and 21 Ming tombs (Shaanxi sheng 2018b; Yang 2018) (Fig. 3).

2.1 Neolithic cemetery

The Neolithic cemetery contained only single burials. Tomb sizes varied little, the graves usually being just large enough to hold the body. Based on the preliminary archaeological report of the cemetery published so far, only 3% of the excavated tombs (11 out of 343) contained ceramic vessels, usually only one or two ceramic vessels each, including cups, jars, or basins (Shaanxi sheng 2018a). Only one tomb held an amphora, laid next to the body. A few tomb occupants had personal ornaments such as bone hairpins, beads, bracelet, or pendants. If differences in tomb size and tomb furnishing are an indicator of social hierarchy, then the YGZ cemetery suggests a society established on egalitarian principles with no differentiation by age, sex, or social status, at least in death.

2.2 Settlement layout

In size, the area within the ditch at YGZ is about twenty times larger than any of the earlier Neolithic sites in the Wei River Valley, such as Banpo (Zhongguo 1963) or Jiangzhai 姜寨 (Xi’an et al. 1988), which are estimated to have measured about 5 ha. Deposits at Banpo and Jiangzhai indicate that the two sites were “occupied discontinuously but repetitively” (Chang 1987: 114). YGZ presents a different picture. Although overlapping features discovered in various parts of YGZ reflect house repairs or house reconstruction in the same spot, the cultural layers in the residential areas are relatively thin and homogeneous compared to the thick deposits of Banpo and Jiangzhai, which include different cultural components from late Neolithic to Bronze Age. Nevertheless, deposits in deep features such as the ditches and pits are thick, indicating intense impact of both human activity and nature.

One similarity shared by YGZ and earlier sites is the spatial separation of the living and the dead; in all cases, the cemeteries were outside the residential area. Other than that, YGZ presents a very different layout. Excavations so far revealed no central plaza like those in the early sites where houses or clusters of houses surrounded an open area in the middle, and there were no large communal houses. An important feature of Banpo and Jiangzhai is the separation of the residential area from its ceramic workshops, but that is not the case at YGZ. There, houses and ceramic workshops were intermingled, sitting side by side. This reminds us of the Fulinbao 福临堡 site on the western end of the Wei River Valley and the Quanhucun 泉护村 site on its easternmost extension (Baoji shi et al. 1993; Shaanxi sheng et al. 2014). Both had a layout similar to that of YGZ and the number of pits at these sites is much higher than that of any other type of feature, as well.

At YZG, various types of features were found on both sides of the ditches, either close to the edge or right on the edge of the ditch. This suggests that the ditches were neither used for defensive purposes nor symbolic in nature (Fig. 4). At present, there is too little data to be entirely sure about the function of the ditch; furthermore, the function may have changed over time, starting for instance as a settlement demarcation that may have become less relevant in later periods when the settlement grew beyond what was originally envisioned. At least for part of the usage period, however, it seems highly likely that the large ditches were utilized for water/flood management. Mathew Fox’s (2014) study on the ditch formation process indicates that overland flow formed the bottom unit of the ditch deposits, and that flood water was the major force responsible for forming the deposits above. Jennifer Kielhofer’s (2013) research on the reconstruction of the paleoenvironment and Hu Ke’s (2017) study on ancient river courses demonstrate that the site was flooded numerous times during and after the Neolithic period. These indicators suggest that water/flood control must have been on the minds of the YGZ inhabitants when building the ditches.

Other features that may have been related to water management include a potential reservoir and drainage ditches. In the central part of the ditched area, on a mild slope, is a large, irregular-shaped, sunken spot measuring close to 340 square meters with a depth from 2.8 to 3.1 m (Shaanxi sheng 2018). Two step-like platforms were found next to the bank, which are thought to have been footsteps used when fetching water (Shaanxi sheng 2018). Signs of cutting at the bottom of the bank are understood to be the result of removing silt. More convincing evidence is a small channel found at the lower end of the potential reservoir which led to a densely occupied area of houses, kilns, child burial, and pits (Fig. 5).

As mentioned above, hui keng 灰坑, literally “ash pits,” generally interpreted as garbage dumps, account for over 80% of the features excavated at YGZ and other places in the Wei River Valley such as Quanhucun mentioned above. These pits have generally attracted little interest as objects of research; however, their history can be complex as they may have gone through several incarnations of usage such as dwellings or storage pits before having served as dumps and then closed after having been filled with trash. So far, only one such pit, H85, has been excavated and researched in great detail, and we will discuss it further below due to its complex history (Shaanxi sheng and Zhong Mei 2018).

In addition to over 49 houses, 896 so-called ash pits, 9 ditches, and 32 urn burials, a total of 26 kilns were found in Beiqu and Nanqu.Footnote 2 Several kilns were dug into the banks of the ditch. In several places, there are layers of pottery sherds in the ditch, as for instance recorded near the “West Gate” of the trenched area. Many of these sherds are restorable (Shaanxi 2009; Wang and Lee 2010). In Nanqu, a development postdating the ditched area, archaeologists found several kilns and 13 cave dwellings arrayed along an ancient cliff, many of them in alternating sequence of kilns and dwellings (Fig. 6). Some of these cave dwellings differed from other houses in the number of hearths found inside: one contained three, another two. The excavators believe that this area was devoted to pottery making and that the cave dwellings next to the kilns served as working spaces, but they do not say why more than one hearth should be needed in some of them. Among the many pits in this area, one (H402) contained a group of complete ceramic vessels, including 22 amphoras, 19 jars, 16 bowls, 9 basins, 5 urns, some unfired pottery, and one object that investigators believe to be a potter’s wheel (Fig. 7).Footnote 3

It seems that this large settlement had no “center” or “central place.” The clusters of houses scattered around the site likewise showed no indication of settlement planning. The buildings were orientated in a variety of directions, and pits were scattered everywhere in between. The anthropogenic deposits at the site consist mostly of household waste, including fragmented building materials of daub, burnt earth, residential matting or floors of animal enclosures, organic waste, and a large amount of broken or otherwise unusable ceramics (Fox 2013). Waste associated with pottery productions were found in many places, some of them deformed pottery but mostly vitrified chunks from broken kilns, and it has thus been suggested that the site may have been a ceramic production center, though further excavation work is necessary to test this hypothesis (Hein et al. forthcoming). The two well-preserved kilns found in the northeast section have intact fire boxes and fire chambers, where the walls show the provenience of the vitrified materials. Household hearths produced no vitrified materials despite repeated firing, indicating that the temperature was not high enough for vitrification.

2.3 Special-purpose buildings

The houses at YGZ were constructed with wattle and daub similar to other Neolithic dwellings in the Wei River Valley. Largely missing at YGZ are large houses of square or rectangular shape as they have been found in earlier or contemporary sites in the valley (Shaanxi sheng and Baishui xian 2011). Most houses found at YGZ were round-shaped, above ground or semi-subterranean dwellings. Some house floors were covered with calcium carbonate nodules. House sizes varied, the large ones having a diameter of close to 9 m.

One of the many pits mentioned above, H85, was characterized by a large number of layers with a complex deposition history and two platforms on the bottom (Fig. 8) (Shaanxi sheng and Zhong Mei 2018). H85 had an oval opening and measured 4 by 2.3 m on the top with a diameter of 3.85 m on the bottom and a depth of 3.2 m. Careful excavation and testing of the deposits of this pit led us to suggest that it was used as a subterranean dwelling for a special purpose.Footnote 4 A similar sized pit found in Quanhu had a hearth at the bottom and postholes around the pit opening and a staircase along the pit wall (Shaanxi sheng et al. 2018). The internal deposition layers were similar in character and contents to those of H85. The primary deposit at the bottom of H85 consisted of ash, sand-size charcoal, charred seeds, animal bones, shells, and restorable ceramic vessels. Cooking pot lids and serving bowls were leaning on the wall upon excavation. Above, the pit contained alternating bands of grey and brownish colored deposits that were household garbage paved over with fresh dirt making a new living surface, covered again with garbage, followed by a new living surface, and so on.

Pit H85 (after Shaanxi sheng and Zhong Mei 2018: Fig. 2)

The large number of ceramic rings found in the pit – 87 in total – suggest that it may have been a communal dwelling for mothers and their infants. It has long been speculated that Yangshao ceramic rings were used as bracelets, and this was finally proved by the discovery of a cemetery at YGZ were ceramic rings were indeed found on the wrists of many tomb occupants, both male and female, adults and children. They serve as diagnostic artifacts to differentiate age groups: smaller sizes for children and larger ones for adults. Several skeletons, including a child, had rings on their wrists upon excavation. In H85, a total of 87 ceramic rings were found, 44 of them from the bottom layers, all of them ranging from 3.3 to 6 cm in diameter (Shaanxi sheng and Zhong Mei 2018). Modern-day bangles for women usually measure around 6.5 cm in diameter, suggesting that the ones found in H85 were worn by adult women or men and children. While the rings in the upper layers were larger in diameter (mostly between 5.5 and 7.7 cm, only 11 measuring 5 cm or less), of the 44 rings from the bottom layers, 36 (82%) had an inner diameter equal to or smaller than 5 cm; of these, 12 were equal to or smaller than 4 cm (Shaanxi sheng and Zhong Mei 2018: Table 1) (Fig. 9). Additionally, an infant skeleton was found in a structure right next to H85 and three burials of older children were found within 30 m east of H85, supplying further support to the hypothesis of H85 being a dwelling for women and children.Footnote 5 The remains of animal bones, such as fresh water turtles, yellow-cheek fish, and gold eagle, and plenty of domestic and wild plants as well as various kinds of herbs identified via paleobotanical analysis on floatation samples may indicate the special care that the dwellers of this pit received from the community.

2.4 Subsistence and medical knowledge

The YGZ community subsisted on millet cultivation, pig husbandry, wild animal hunting, fishing, and wild plant gathering. Systematic samples taken from one pit (H85) for paleobotanical research show that of all identifiable charred seeds, 31% are foxtail grasses, followed by millet (27%), and legumes (16%) (Ma 2016; Tang et al. forthcoming). Well-developed agriculture and a sedentary way of life enhanced the inhabitants’ familiarity with their surroundings and vegetation. A concentration of herbs, including Xiazhicao 夏至草 (Lagopsis supina), Tuchuanghua 秃疮花 (Dicranostigma leptopodum) and Nihucai 泥胡菜 (Hemistepta lyrate) were found at the bottom layers of the pit (Fig. 10). All of these are commonly used in Chinese medicine today for treatment of gynecological disorders and ailments, bringing down a fever, staunching bleeding from wounds, and even insect control. Xiazhicao is widely used to treat gynecological illness of amenorrhea, dysmenorrhea, irregular menstruation, excessive postpartum hemorrhage, postpartum uterine contraction and other postpartum related ailments. Tuchuanghu, a Papaveraceae, is able to bring down fever, help with detumescence, analgesia, sore throat, and lymphatic tuberculosis, and it is also used in insect control. Nihucai is used to treat all kinds of sores, hemorrhoids, and wounds (Tang et al. forthcoming). Without more extensive archaeobotanical studies of other parts of the site, it is still too early to draw a conclusion that the YGZ residents had already acquired knowledge of certain herbs and their medical effect. Yet, a concentration of such herbs with similar function in treatment found in the bottom of the pit implies that the inhabitants of the dwelling had certain demand for them.

Paleobotanical samples from H85: 1. Schoenoplectus mucronatus 水毛花, H85④; 2. Carex 薹草属, H85⑨; 3. Corydalis bungeana 地丁草, H85.14; 4. Dicranostigma leptopodum 秃疮花, H85.14; 5. Lagopsis 夏至草, H85.14; 6. Perilla frutescens 紫苏, H85.14; 7. Hemistepta lyrate 泥胡菜, H85.14; 8. Asteraceae flower heads 菊科头状花序, H85.14; 9. Patrinia scabiosifolia 黄花龙牙, 2013H85②; 10. Sour jujube 酸枣, 2013H85⑦; 11. Geraniaceae 牻牛儿苗, 2013H85④; 12. Thorn 刺状物, 2013H85③; 13. Bulb front and base 鳞茎, H85.14; 14. Bulb base 鳞茎 (same as 13, enlarged), H8514; 15. Bulb, enlargement of internal cell structure (same as 13 and 14), H85.14; 16. Bulb 鳞茎, H8514; 17. Bulb 鳞茎, H85.14; 18. Bulb 鳞茎, 2014H85⑨ (after Tang et al. forthcoming)

As elsewhere in the Wei River Valley during this period, pigs were raised for meat consumption. At YGZ, the slaughtering age for pigs was around two years or younger (Hu et al. 2011; Shaanxi sheng and Zhong Mei 2018). Other domesticated animals include chicken, perhaps ox, and dog; however, among the remains of domesticated animals, pigs were by far the most common. The two published sets of fauna collections from YGZ are from two different locales, the “West Gate” next to the ditch and H85. They show different results. This is likely due to different sampling methods (screening vs. non-screened),Footnote 6 but differences in locale may also be a factor. For the ditch, investigators identified 11 species; among these, domesticated pig accounts for 78% of all bones. For H85, of the twenty identified species, pig bones accounts for only 6%. However, in both places, wild animals were far more common than domestic animals: in the ditch, 63% are wild animal bones (7 out of 11 species); in H85, wild animals account for 90% of all the recovered bones (18 out of 20 species). Flad et al.’s (2007 and 2009) study on meat consumption in Northwest China has reached a similar conclusion for this region during the Neolithic period.

2.5 Communication with the outside world

Portable XFR analysis conducted on the clay composition of 932 sherds from 11 features of both Miaodigou and Banpo IV phases of YGZ was conducted in 2015 and 2016. The data seem “consistent with a more homogenous clay composition in the Banpo IV period than in the earlier Miaodigou period” (Bradly et al. 2017). This is consistent with the fact that during the Banpo IV phase, the settlement was compressed to a much smaller space and ceramic production was carried out in a more centralized fashion. More notable is the fact that by “using bivariate plots, a difference between H402 and other YGZ features in terms of clay is apparent” (Bradly et al. 2017). The ceramic types found in H402 were common at sites throughout the Wei River Valley at the time, especially the broad-shouldered amphora with scratched swirling patterns, mostly found in the vicinity of present-day Xi’an (personal communication with Shao Jing, 2019). YGZ did have other ceramic items that were likely imported, mostly small portable items such as the white paste bracelets, either plain or with red-painted patterns. So far, archaeological finds in the Wei River valley have not produced any locally made white paste ceramics, so we conclude that they were imported from outside the valley, mostly likely from today’s Henan 河南 province.

Human occupation at YGZ ended quite abruptly. The abandonment of the settlement was likely caused by floods. When the settlement moved south and closer to the Jing River, the chances for the site being flooded increased. Nine profiles of test trenches at YGZ indicate that overbank flooding occurred on several occasions (Kielhofer 2013). Evidence of slack water deposits (SWDs) found on the profile south of the site indicate that at the end of Mid-Holocene Climatic Optimum, extraordinary floods occurred along the Jing and Wei rivers (Gu et al. 2012; Huang et al. 2010, 2011). Geomorphological studies show that between the lower paleosol and the upper paleosol at YGZ, five major floods occurred one after another (Gu et al. 2012; Huang et al. 2010, 2011). The OSL dates indicate several lower SWDs between 4200 and 4000 BP and an upper SWD between 3200 and 2800 BP (Gu et al. 2012). The floods covered the first terrace of the Jing River, land instability occurred (Gu et al. 2012). Nonetheless, radiocarbon dating from human bone from the YGZ cemetery (3637–2918 cal. BCE) (Shaanxi 2018a) does not exactly match the OSL dating. Thus, although we are not certain if the abandonment of YGZ was caused by a specific flood, flood water was a key element to consider. After the Neolithic residents left YGZ, the area was deserted for over 3000 years. The eight other known Yangshao settlements along the Jing and Wei Rivers in the vicinity of YGZ were abandoned, as well. Two late Neolithic Longshan 龙山 cultural sites were found on the secondary terrace of the Wei River and on a knoll respectively (Guo jia wen wu ju 1998: vol. 2, 133). The next sign of human activities at YGZ appeared only around the second century BCE, with a single sacrificial event that took place during the Western Han 汉 dynasty, leaving a large ceramic vessel next to two small lambs in the ruins of the Neolithic village (Sino-American Field School 2012).

3 Qin and Han period YGZ (fourth century BCE to third century CE)

YGZ was not used as a settlement during the very long and eventful period from the late Neolithic to the Iron Age. Even after the land stabilized and pedogenesis occurred as reflected by the soil unit above the SWDs, people did not return to YGZ. Historically, from the fourth to third centuries BCE, the vast area stretching from just north of the Jing and Wei Rivers to the hills of the loess plateau (known to locals as Beishan 北山 or northern mountains) was controlled by the Qin 秦 State, and later the Qin Dynasty (Li 1984: 175–189). Historians often treat the 383 BC move of the Qin capital from Yongcheng 永城 at the western end of the Wei River Valley to Liyang 溧阳 at the foothills of the loess plateau as the prologue to the unification of China some 200 years later. Not long after that, in 349 BC, the Qin moved its capital again to Xianyang 咸阳, a fertile area in the heart of the alluvial plain of the Jing and the Wei. The Qin stayed there for over 144 years until Xiang Yu 项羽 and his troops burned down the city in 206 BC. YGZ sits right in the middle of the two capitals, 33 km southwest of Liyang and 16 km northeast of the Qin’s Xianyang capital (Li 1984: 175–189).

Critical to the transformation examined in this study was the construction of the Zheng Guo Canal 郑国渠 in 246 BC. Sima Qian (first century BCE) tells the dramatic story of its construction in his Shi ji 史记, or Records of the Grand Historian: the failed political plot, the persuasion of the hydraulic engineer Zheng Guo 郑国, and the visionary Duke of the Qin, all working in the end to bring the canal to completion. The result was amazing: it was 300 li long, running “along the foot of the northern mountains, carrying water of the Jing to fall into the Luo 洛河 river in the east… When it was finished, rich silt-bearing water was led through it to irrigate more than 40,000 qing 頃 (667,000 acres) of alkali land. The harvest from these fields attained the level of one zhongFootnote 7 per mu 亩. Thus, Guanzhong 关中 became a fertile land without recorded poor harvests. Qin became rich and powerful, and in the end was able to conquer all the other feudal states” (Sima Qian: vol. 29, 1408).Footnote 8

Archaeological surveys revealed the original dam and canal of the third century BCE as well as many later dams and canals from the Han to the 1930s (Qin et al. 2006) (Fig. 1). Although the survey report could not link all the dams and canals unequivocally with those mentioned in the histories, the surveys found over 30 dams and 17 water channels and identified more than 20 hydraulic projects in a 10 square km area near Gukou 谷口 in Jingyang 泾阳 County (Qin et al. 2006: Fig. 1-3).

The move of the Qin capital to the hillside above the valley in the fourth century BCE was initially a political tactic, but in the end it lifted the Guanzhong agricultural economy to an unprecedented level. By the end of the third century BCE, when the Western Han had established its capital in the valley south of the Wei River, the Jing-Wei plain had become one of the richest areas in Han China. Population numbers boomed due to the policy of “strengthening the center and weakening the outlying areas” (qiang guan ruo zhi 强干弱枝) of the early Western Han, when the court promoted the coercive and voluntarily relocation of the powerful feudal families to stabilize the Han polity. In addition, mausoleum construction north of the Wei River also needed a large labor force. Ling yi 陵邑, mausoleum townships, were built on the secondary terraces to hold the migrant laborers. According to the Shi ji and Hanshu, by the beginning of the first century CE, the population of the mausoleum townships reached over 400,000 (Yu Xi 2013). One of them, Yangling 阳陵 township, was located less than 3 km across the Jing River from YGZ. According to the ca. CE 110 Gu et al. 1997 汉书, household surveys of 2 CE (Song 1370: 2) show that Changling 长陵 had 50,057 households and a population of 179,469; Maoling 茂陵, 60,187 households and 277, 277 population (Ban Gu et al.: vol. 28, 1545–47). No household numbers are known for Yangling. When the township was established, the household and population numbers were likely lower. The results of archaeological excavations conducted at Yangling township have been reported in detail (Yan et al. 2013; Yang 2011, 2014, 2017).

These rapid developments during the Qin-Han period seem to have spared YGZ. The result of the first (1956) and second (1981–1989) nationwide cultural heritage surveys and subsequent fieldwork in the area show no Han remains along the first terrace of the Jing River near YGZ, but on a higher knoll south of the Jing River there were few (Guo jia wen wu ju 1998: vol. 2, 133–134). It is plausible that concerns over flooding played a role in people staying away from YGZ while the irrigated land north of YGZ seems to have been more attractive to them. In addition, since YGZ was so close to the political center at the time, people may not have been able to choose freely where to settle in this area. When concrete evidence liberates us from the realm of guesswork, time had already raced to the AD fifteenth century. In other words, for over 4000 years, YGZ left no archaeological remains.

4 The Ming (1368–1644) tombs

Within the confines of the YGZ Neolithic cemetery, archaeologists also found 21 Ming 明 dynastic period tombs (Shaanxi 2018a, Yang 2018). Among them, four had epitaphs dating between 1531 and 1603 (Fig. 11). The tombs belong to at least three generations of the Zhang 張 family who belonged to the local elite, tracing their ancestors back five or six generations, living in three villages within less than 4 km. The epitaphs briefly traced their ancestors’ origins and family history, listing the names of three villages where the family had resided and that still exist today. From the epitaphs, we learn that the Zhang family had lived near YGZ for over 200 years. Their forebears lived in Hancun 寒村, a port village on the northern bank of the Jing River. Later, the family moved to Afanzhai 阿藩寨, and finally settled in Xuwucun village 徐吾村 in the early Yuan 元 dynasty (AD 1260–1368) (Fig. 12). The epitaphs do not reveal the cause or dates of the moves, but they seem to have been unrelated to either social turmoil or natural disasters since the moves were very local. The most likely reason was family partition, a common practice as members moved nearby when a family grew too large to be accommodated in the same settlement.

Epitaph of Mr. Zhang Mianshan (1488–1560) of the Ming and his wives Shishi (1487–1541) and Gaoshi (1510–1567) 明故处士面山张公暨配石氏高氏合葬墓志铭. He is described as chu shi 处士, denoting that he is a person with virtue who lives in seclusion and does not want to be an official or a scholar and who has not attained an office. He was the oldest son of the Zhang family. He travelled to Suzhou and Hangzhou when he was young and came to be well-known among the literate class. Following the wishes of his father, he returned home eventually and took over family affairs (Shaanxi sheng 2018b:22)

The Zhang’s forebears were known to locals as the Pontoon-Bridge Zhang 桴橋張家, as stated on the epitaph of tomb M54, since each year they built a pontoon bridge across the Jing River at Hancun, a port on the northern bank of the Jing River. This port is also known as Huangjiadu 黄家渡, as mentioned in the 1541 Gaoling 高陵 gazetteer.Footnote 9 Today’s Hancun is further from the Jing River, likely due to a shift in the water course to the south and erosion of the bank. Nonetheless, it is still the closest village to the river. A modern cement bridge was built in the year 2000.

The two villages mentioned in the fourteenth century tomb epitaphs, Hancun 韩村 and the Xuwucun 徐武村, bear the same names as two villages close to the YGZ Ming tombs, and they both first appeared in the Gaoling county gazetteer published in 1541 (Gaoling xian 2000) (Fig. 13). The character for the han 寒 of Hancun differs between the epitaphs and modern usage (韩村), but based on location, these refer to the same village. The character of wu for the Xuwucun is also different in the epitaphs. Three of the four epitaphs used the character wu 吾 that is used today, but one chose a different character, wu 吴. The newest Gaoling gazetteer, published in 2000, uses both 吾 and 吴 for Xuwucun and in the map of the 1541 gazetteer, wu 吴 is printed as ju 具, likely a printing mistake (Gaoling xian 2000). All in all, it is highly likely that these all refer to the same place. The only village name that appeared in the epitaphs but not in the Ming gazetteer is Afanzhai, the place the Zhang family moved prior to their final residence in Xuwucun. Afanzhai appears in a much later edition (1732) of the Gaoling County Gazetteer, as Afanzhai Wangjia 阿藩寨王加, later called Jiangwangjia 酱王家, and today, Jiangwang 酱王 (Xi’an shi 2017a) (Fig. 14).

Map in the Gaoling county gazetteer showing YGZ (1524) (after Ma Li 1541 (2020): vol. 2, Fig. 4)

One of the epitaphs mentions that the family cemetery was located west of Xuwucun and that it is a newly established family cemetery (xin ying 新茔). Today, Xuwucun has two clusters: Upper and Lower Xuwucun (Shang Xuwu 上徐吾and Xia Xuwu 下徐吾). The YGZ Ming tombs are located west of Upper Xuwucun and north of Lower Xuwucun, indicating that Upper Xuwucun is the older of the two villages.

It is clear that the Zhang family never lived at Yangguanzhai, as YGZ is not mentioned in the epitaphs, but it appears on the maps of the 1541 county gazetteer (Ma Li 1541 (2020): vol. 2, Fig. 4). The 1732 gazetteer specifies YGZ as occupied by jun hu 军户, military/garrison households (Xi’an shi 2017). It may have become a garrison already in the early half of the thirteenth century when Ogodei Khan of the Yuan ordered the tun tian 屯田 system of agriculture to be applied to land irrigated by the Sanbai Canal 三白渠. The tun tian system originated during the Han period with soldiers converting newly conquered land into farmland whose crops were used to supply the army. Later, the tun tian system came to be applied to civilians as well, who were given land and farming implements in exchange for half their harvest, which they had to give to the government (Luo et al. 2017). A tun tian office had been set up in the neighboring county of Jingyang, which claimed 1020 qing of land (Yuan shi vol. 60, p. 1424). At the peak of the tun tian program during the latter half of the thirteenth century, under the Shaanxi Tuntian Command 陕西屯田总管府, the government claimed a total of 5853 qing of land from the valley and controlled over 7000 farming households (民屯) (Li 1993). In the process of land reclamation, Gaoling County participated actively in the construction of another Jing River canal, the Hongkou Canal 洪口渠, to ensure that their land was irrigated. Although the military did not control the Sanbai irrigation tun tian land, it was heavily involved in taxation and in recruiting labor to work the reclaimed land and transport supplies to the military (Song Lian 1370: vol. 65, 1629–1631). It is possible that YGZ and its adjacent land was once reclaimed land, used to support the military.

5 Conclusion

In sum, despite all the missing information on some periods and details of life at YGZ over the past 5000 years that still need to be traced via further fieldwork, the available data from the late Neolithic and the Ming Dynasty provide some interesting insights into human-landscape connections. The land, which sits on the alluvial plain of the Jing and the Wei Rivers, is environmentally rich but subject to flooding by a very active river system. During the Holocene climate optimum, the first settlers came to YGZ and settled on the first terrace of the Jing River. They were farmers with sophisticated skills in pottery making, practicing millet cultivation, raising pigs, chickens, and dogs, hunting animals on land and water, and gathering wild plants and herbs. They had forged relationships, directly and indirectly, with other groups living in the same valley and further afield. No clear social hierarchy is evident from their burials or habitation sites. Perhaps young children and women were treated differently, but at present the evidence is inconclusive. We hope that future excavation will pay close attention to ditches and pits, as they preserve the most valuable archaeological data, as in-depth analysis of H85 has shown.

The lack of human occupation and cultural remains after the Neolithic has generated many questions. Although surface collection in and around the Neolithic settlement include a few pottery and porcelain sherds from the second century BCE to the twelfth century CE, archaeologists found no cultural remains of this period. There is some evidence for rather limited human occupation in the vicinity for the early imperial period, though not at YGZ itself. At first sight, this seems surprising, considering that the Guanzhong Plain became the political center and home to the capital for the early empire and beyond. Indeed, we see a large gap between Neolithic and Ming dynasty remains. The main reason that we can see at present is a change in river courses, bringing with it an increase in flooding that made the area around YGZ less attractive to settle in. Even prior to such changes, which are geomorphologically attested, living in this area was always somewhat risky, though the access to water, fertile soil, and routes of exchange seems to have outweighed these risks at least in the view of the Neolithic inhabitants, though not thereafter. The lack of occupation for the Qin and Han period in particular may have been connected to the establishment of the capitals of the Qin and Han in the Guanzhong Plain, i.e., in the immediate vicinity, attracting large numbers of people with business opportunities and hopes for a better life. Nevertheless, these cities required an extensive hinterland to supply them with grain and other food and raw materials, so one would expect there to have been a number of farmsteads and villages making use of the fertile land. We hope that further geoarchaeological research will establish more accurate readings of the river’s movement, the floods, and human land use in the river valley. Additionally, newly excavated texts may provide further insights into administrative structure and population movements at least for the Qin and Han periods (Korolkov and Hein 2020).

The modern landscape of YGZ had already taken shape by the thirteenth century. The three villages mentioned in the Ming epitaphs still exist today. Some villages, such as Xuwucun, split up into two or more villages; others remained one community but expanded in size. YGZ, which was not mentioned in the epitaphs for reason that the village had never been a destination of the Zhang family, appears first in the Gaoling gazetteer of the Ming. It is to say, that although we do not know when the first terrace of the Jing River was reclaimed, we are certain that for centuries, even though flooding still posed a threat to people, they still lived there (Gu et al. 2015) . We also noticed that the Neolithic burial ground for its community turned into the Zhang family’s cemetery of the Ming centuries later. We cannot tell why that plot of land was perceived as a place for the dead by the residents, whether they lived 5000 years ago or 500 years ago: we see discontinuity of human settlement in this location, as well as continuity of human behavior in terms of land use.

The landscape around YGZ has been continuously changing since 2004 when the Shaanxi provincial government designated the area as an economic development zone. Change has accelerated after the announcement of the Belt and Road Initiative. Another terminal has been added to the Xianyang-Xi’an airport, and an inland free trade port has been erected, all within a radius of 15 km from the site. The impact of economic developments on the environment is enormous, as we have noticed intensely during our fieldwork over the past ten years as we have worked on a project that attempts to understand the relationship between human activity and the natural environment.

Notes

The ditch has been only partially excavated on the east and west side. The north and south sides of the ditch are unclear in their dimensions because modern buildings and a paved road prevent further survey and excavation.

These numbers do not include kilns excavated after 2009 which have not yet been reported, or features indicating open firing without kilns which have not been systematically collated yet.

Nearly identical “potter’s wheels” have also been found at Banpo and Anban (Kaogu 1963).

Research on this feature is still ongoing and micromorphological samples taken from the bottom of the pit still await analysis.

There was no burial equipment such as an urn for the infant body. The International Archeological Field School (IRF) excavated the body. Elizabeth Berger identified the skeleton is 36–40 weeks old. Micromorphological samples were taken where the skeleton was found, and they now await analysis.

The International Archaeological Field School, IFR, excavated H85. A screen with a mesh of 0.5 × 0.5 cm was used and samples were taken separately for each layer. No screen was used at the West Gate excavation. Rowan Flad and his Chinese colleagues discussed this problem in Chinese archaeological practice in 2007 (Flad et al. 2007). Even though collecting fauna remains improved somewhat since 2007, screening is still not common in many archaeological sites, especially in rescue projects.

One zhong = 64 dou 斗, 1 dou (in the Han Dynasty) = 7.5 kg. Thus this represents a harvest of 480 kg per mu.

The translation is based on Needham 1971: 283. The story was that after the Duke of Han 韓 learnt about the ambitions of the Qin, he sent the hydraulic engineer Zheng Guo to Qin to persuade them to open a canal to link the Jing and the Luo Rivers. The purpose was to exhaust the Qin’s power with this grand public project. Later, after the Duke of Qin had been made aware of this plan, he wanted to kill Zheng Guo. Zheng Guo admitted his deceitfulness but told the Duke that “when the canal is completed, it will be of great benefit to Qin.” The Duke listened and let Zheng Guo finish the project. Joseph Needham has compiled a detailed analysis from the historic accounts of the project.

Lu Nan 吕柟 wrote the first Gaoling zhi 高陵志 (Gaoling County Gazetteer) in 1541. Two more were compiled in 1732 (the tenth year of the Yongzheng 雍正 reign) and 1881 (the seventh year of the Guangxu 光绪 reign). The two latest editions were published in 1941 and 2000.

References

Ban Gu 班固, Ban Zhao 班昭, and Yan Shigu 顏師古. 1997 edition (c. CE 110). Han shu: [100 juan] 漢書:[100卷]. Xianggang: Xianggang zhong hua shu ju 香港中華書局.

Baoji shi kao gu gong zuo dui 宝鸡市考古工作队, Shaanxi sheng kao gu yan jiu suo Baoji gong zuo zhan 陕西省考古研究所宝鸡工作站. 1993. Baoji Fulinbao: Xin shi qi shi dai yi zhi fa jue bao gao 宝鸡福临堡:新石器时代遗址发掘报告 (Baoji Fulinbao: Excavation report of a Neolithic site). Beijing: Wen wu chu ban she.

Bradley, Veronica C., Margaret C. Tojo, Corinne C. Deibel, Michael A. Deibel, Ye Wa, and Yang Liping. 2017. Analysis of ancient Chinese pottery using portable XFR and portable diffuse FTIR spectroscopy. Poster presented at the annual meeting of the Society for American Archaeology, Vancouver.

Chang, Kwang-chih. 1987. The archaeology of ancient China. 4th ed. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Flad, Rowan K. 傅羅文, Yuan Jing 袁靖, and Li Shuicheng 李水城. 2009. Zhongguo xi bei di qu zui zao dong wu xun hua de dong wu kao gu xue zi liao 中国西北地区最早动物驯化的动物考古学资料 (Zooarchaeological data on the earliest animal domestication in China). Kao gu 考古 2009.5: 80–86.

Flad, Rowan K., Yuan Jing, and Li Shuicheng. 2007. Zooarcheological evidence for animal domestication in Northwest China. In Late Quaternary climate change and human adaptation in arid China, Development in quaternary sciences Vol, ed. David B. Madsen, Chen Fa-Hu, and Xing Guo, vol. 9, 167–203. London: Elsevier.

Fox, L. Mathew. 2013. A micromorphological analysis of Miaodigou refuse at Yangguanzhai, Wei River Valley, China: The geoarchaeology of Yangshao midden deposits and Neolithic moats. Master’s Thesis. University of Arizona, School of Anthropology.

Gaoling xian di fang zhi bian zuan wei yuan hui 高陵县地方志编纂委员会 (editor). 2000. Gaoling xian zhi 高陵县志 (Gaoling County gazetteer). Xi’an: Xi’an chu ban she.

Guo jia wen wu ju 国家文物局. 1998. Zhongguo wen wu di tu ji: Shaanxi fen ce 中国文物地图集:陕西分册 (atlas of Chinese cultural relics: Shaanxi). Xi’an: Xi’an di tu chu ban she.

Gu Hongliang 顾洪亮, Huang Chunchang 黄春长, Zhou Yali 周亚利, Pang Jiangli 庞奖励, Zha Xiaochun 查小春, and Zhang Yuzhu 张玉柱. 2012. Guanzhong pen di Yangguanzhai yi zhi gu hong shui shi jian shi guang ce nian 关中盆地杨官寨遗址古洪水事件释光测年 (OSL dating on the paleoflood events recorded at the Yangguanzhai Neolithic site in the Guanzhong Basin). Di li yan jiu 地理研究 31 (10): 1837–1848.

Gu Jing 顾静, Huang Heqing 黄河清, Zhou Jie 周杰, and Zhao Jingbo 赵景波. 2015. Jinghe liu yu 1644-2003 nian hong lao zai hai he hong shui chen ji te zheng yan jiu 泾河流域1644-2003年洪涝灾害和洪水沉积特征研究 (characteristics of flood disaster and flood deposition in Jinghe River basin from the years 1644-2003). Zai hai xue 灾害学 Journal of Catastrophology 30 (1): 16–20.

Hein, Anke, Ye Wa, and Yang Liping. Forthcoming. Soil, hands, and heads – An ethnoarchaeological study on local preconditions of pottery production in the Wei River valley (northern China). Advances in Archaeomaterials.

Hu Ke. 2017. The influence Holocene changes in hydrological conditions and river course migration of the Jing and Wei rivers on the Yangguanzhai settlement. Paper presented at Yangguanzhai conference, Gaoling, Shaanxi, November 2017.

Hu Songmei 胡松梅, Wang Weilin 王炜林, Guo Xiaoning 郭小宁, Zhang Wei 张伟, and Yang Miaomiao 杨苗苗. 2011. Shaanxi Gaoling Yangguanzhai huan hao xi men zhi dong wu yi cun fen xi 陕西高陵杨官寨环壕西门址动物遗存分析 (analysis of animal remains from the west gate of Yangguanzhai site, Gaoling, Shaanxi). Kao gu yu wen wu 考古与文物 2011.6: 97–107.

Huang, Chun Chang, Jiangli Pang, Xiaochun Zha, Yali Zhou, Su Hongxia, and Yuqing Li. 2010. Extraordinary floods of 4100−4000 a BP recorded at the late Neolithic ruins in the Jinghe River gorges, middle reach of the Yellow River, China. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 289: 1–9.

Huang, C.C., J. Pang, X. Zha, Y. Zhou, H. Su, H. Wan, and B. Ge. 2011. Sedimentary records of extraordinary floods at the ending of the mid-Holocene climatic optimum along the upper Weihe River, China. The Holocene 22 (6): 675–686.

Kielhofer, R. Jennifer. 2013. Geoarchaeological investigations at Yangguanzhai: An examination of soil-stratigraphic sequences at a middle Neolithic site in the Wei River valley, Northern China. Master’s Thesis, University of Arizona, School of Anthropology.

Korolkov, Maxim, and Anke Hein. 2020. State-induced migration and the creation of state spaces in early Chinese empires: Perspectives from archaeology and history. Journal of Chinese History.

Li Xueqin 李学勤. 1984. Dong Zhou yu Qin dai wen ming 东周与秦代文明 (eastern Zhou and the Qin civilizations). Beijing: Wen wu chu ban she.

Li Yu 李蔚. 1993. Shi lun Yuan dai xi bei tun tian de ruo gan wen ti 试论元代西北屯田的若干问题 (discussion on the tun tian in Northwest China during the Yuan dynasty). Lanzhou da xue xue bao 兰州大学学报 21 (2): 94–100.

Luo, L., X. Wang, J. Liu, H. Guo, W. Ji, C. Liu, and R. Lasaponara. 2017. Uncovering the ancient canal-based tuntian agricultural landscape at China’s northwestern frontiers. Journal of Cultural Heritage 23: 79–88.

Ma Li 马理. 1541 (2020). Chong ke Gaoling xian jiu zhi 重刻高陵县旧志 Reprinting the Gaoling gazetteer, compiled by Lü Nan 吕柟 in 1541. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.32044068031921&view=1up&seq=1, last updated on 13 April 2020, accessed on 27 May 2020.

Ma, Mitchell. 2016. Enhancing the interpretative value of flotation sampling: Preliminary results from Yangguanzhai, Shaanxi Province, People's Republic of China. Master Thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of Toronto.

Needham, Joseph. 1971. Science and civilization in China. Vol. 4, Physics and Physical Teconology, part III: Civil Engineering and Nautics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Qin Jianming 秦建明, Yang Zheng 杨政, Zhao Rong 赵荣. 2006. Shaanxi Jingyang xian Qin Zhengguo qu shou lan he ba gong cheng yi zhi diao cha 陕西泾阳县秦郑国渠首拦河坝工程遗址调查 (Survey of the hydraulic projects at the head of the Zheng Guo Canal of the Qin). Kao gu 2006.4: 12–21.

Shaanxi sheng kao gu yan jiu yuan 陕西省考古研究院. 2018a. Shaanxi Gaoling Yangguanzhai Miaodigou wen hua mu di fa jue jian bao 陕西高陵杨官寨庙底沟文化墓地发掘简报 (preliminary excavation report of the Miaodigou culture cemetery at Yanguanzhai, Gaoling, Shaanxi). Kao gu yu wen wu 2018.4: 3–17.

Shaanxi sheng kao gu yan jiu yuan 陕西省考古研究院. 2018b. Shaanxi Gaoling Shangxuwucun Ming dai mu zang fa jue jian bao 陕西高陵上徐吾村明代墓葬发掘简报 (preliminary excavation report of the Ming tombs at Shangxuwu village, Gaoling County, Shaanxi). Wen bo 文博 2018.5: 15–30.

Shaanxi sheng kao gu yan jiu yuan 陕西省考古研究院. 2009. Shaanxi sheng Gaoling xian Yangguanzhai xin shi qi shi dai yi zhi 陕西省高陵县杨官寨新石器时代遗址 (the Yangguanzhai Neolithic site, Gaoling, Shaanxi Province). Kao gu 2009.7: 3–9.

Shaanxi sheng kao gu yan jiu yuan 陕西省考古研究院 and Baishui xian wen wu lü you ju 白水县文物旅游局. 2011. Shaanxi Baishui xian Xiahe yi zhi Yangshao wen hua fang zhi fa jue jian bao 陕西白水县下河遗址仰韶文化房址发掘简报 (preliminary report on the excavation of Yangshao house remains at Xiahe, Baishui, Shaanxi). Kao gu 2011.12: 47–59.

Shaanxi sheng kao gu yan jiu yuan 陕西省考古研究院, Weinan shi wen wu lü you ju 渭南市文物旅游局, and Huaxian wen wu lü you ju 华县文物旅游局. 2014. Huaxian Quanhucun, 1997 nian kao gu fa jue bao gao 华县泉护村——1997年考古发掘报告 (Huaxian Quanhucun, report of the 1997 excavation season), 2 vols. Beijing: Wen wu chu ban she.

Shaanxi sheng kao gu yan jiu yuan 陕西省考古研究院 and Zhong Mei guo ji tian ye kao gu xue xiao 中美国际田野考古学校. 2018. Shaanxi Gaoling Yangguanzhai yi zhi H85 fa jue bao gao 陕西高陵杨官寨遗址H85发掘报告 (Excavation report of H85 at Yangguanzhai site, Gaoling, Shaanxi). Kao gu yu wen wu 2018. 6: 3–21.

Shaanxi sheng kao gu yan jiu yuan shi qian kao gu yan jiu shi 陕西省考古研究院史前考古研究室. 2018. 2008-2017 Shaanxi shi qian kao gu zong shu 2008-2017 陕西史前考古综述 (summary of Shaanxi prehistoric archaeology from 2008-2017). Kao gu yu wen wu 2018.5: 10–40.

Sima Qian 司馬遷 (first c. BCE), 1987 edition. Shi ji: [130 juan] 史記:[130卷]. Shanghai: Shanghai gu ji chu ban she.

Sino-American Field School. 2012. Unpublished field notes of the Sino-American Field School excavation season of 2012.

Song Lian 宋濂 (comp.). 1370, 1997 edition. Yuan shi 元史. Beijing: Zhong hua shu ju.

Tang Liya 唐丽雅, Mitchell Ma, Ye Wa 叶娃, Yin Yupeng 殷宇鹏, Yang Liping 杨利平, Liu Xiaoyuan 刘晓媛, Wang Weilin 王炜林, Zhao Zhijun 赵志军. forthcoming. Gaoling Yangguanzhai yi zhi H85 chu tu zhi wu yi cun yan jiu 高陵杨官寨遗址H85出土植物遗存研究 (Study of the botanic remains of feature H85, Yangguanzhai site, Gaoling). Kao gu yu wen wu.

Wang, Weilin, and Lee Yun Kuen. 2010. The Neolithic site at Yangguanzhai, Gaoling, Shaanxi. Chinese Archaeology 10: 6–14.

Xi’an Banpo bo wu guan 西安半坡博物館, Shaanxi sheng kao gu yan jiu suo 陝西省考古研究所, and Lintong xian bowuguan 临潼县博物馆. 1988. Jiangzhai: xin shi qi shi dai yi zhi fa jue bao gao 姜寨:新石器时代遗址发掘报告 (Jiangzhai: Neolithic site excavation report). Beijing: Wen wu chu ban she.

Xi’an shi Gaoling qu ren min zheng fu 西安市高陵区人民政府. 2017. Di qing zi liao: “cun luo ji yi” “Chonghuang jie dao zhi Jingwang cun 地情资料:《村落记忆》“崇皇街道之井王村” (Local information, village memory, Jingwang village, Chonghuang township]. In Gaoling di fang zhi 高陵地方志 [Gaoling Gazetteer]. http://www.gaoling.gov.cn/html/ztzl/gldfz/dqs/cljy/201703/28189.html. Published 7 March 2017, accessed 27 May 2020.

Xi’an shi Gaoling qu ren min zheng fu. 2017. Di qing zi liao: “cun luo ji yi” “Jijia guan wei hui zhi Yangguanzhai” 地情资料:《村落记忆》“姬家管委会之杨官寨” (Local information, village memory, Yangguanzhai of Jijia community]. In Gaoling dI fang zhi 高陵地方志 [Gaoling Gazetteer]. http://www.gaoling.gov.cn/html/ztzl/gldfz/dqs/cljy/201703/28288.html. Published 9 March 2017, accessed 27 May 2020.

Yan Yongjie 颜永杰 and Xu Weimin 徐卫民. 2013. Wei bei Xi Han di ling de ying jian yu zi ran huan jing guan xi yan jiu 渭北西汉帝陵的营建与自然环境关系研究 (the relationship between the Western Han mausoleums on the northern Wei River and its surrounding environment. Xi bei da xue xue bao (zi ran ke xue ban) 西北大学学报(自然科学版) Journal of Northwest University (Science Edition) 43(5): 821–825.

Yang Liping 杨利平. 2018. Shaanxi Gaoling Shangxuwucun Ming dai mu di chu bu yan jiu 陕西高陵上徐吾村明代墓地初步研究 (study of the Ming tombs in the Shangxuwucun village of Gaoling county, Shaanxi). Wen bo 2018.5: 31–38.

Yang Wuzhan 杨武站. 2011. Han Yangling chu tu feng ni kao 汉阳陵出土封泥考 (a study of clay seals unearthed from the Han Yangling mausoleum). Kao gu yu wen wu 2011.4: 59–66.

Yang Wuzhan 杨武站. 2014. Xi Han ling yi ying jian xiang guan wen ti yan jiu 西汉陵邑营建相关问题研究 (on the construction of the mausoleums of the Western Han]. Wen bo 2014.6: 39–43.

Yang Wuzhan. 2017. Lun Xi Han ling yi de gong neng 论西汉陵邑的功能 (on the functions of the mausoleum towns of the Western Han). Kao gu yu wenwu 2017.3: 88-93+122.

Yu Xi 喻曦. 2013. Xi Han jing ji di qu cheng shi gui mo chu tan 西汉京畿地区城市规模初探 (a preliminary study of the size of cities around Chang’an capital). Gan han qu zi yuan yu huan jing 干旱区资源与环境 Journal of Arid Land Resources and Environment 27 (3): 27–31.

Zhongguo ke xue yuan kao gu yan jiu suo 中國科學院考古研究所. 1963. Xi’an Banpo 西安半坡. Beijing: Wen wu chu ban she.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wa, Y., Hein, A. A buried past: five thousand years of (pre) history on the Jing-Wei floodplain. asian archaeol 4, 1–15 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41826-020-00036-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41826-020-00036-0