Abstract

In response to pressures imposed on the energy sector, several countries in the Middle East-North Africa (MENA) region have committed to increasing the percentage of renewable energy to reach 15–50% of the energy supply by 2030. New governance models are required to conceptualise and guide the energy transition into a more sustainable direction. Therefore, this paper employed the transition management governance framework to answer the questions of who is governing the renewable energy transition in Palestine, and in what ways it is achieved. The analysis is based on three levels: strategic (problem structuring and envisioning), tactical (coalition building, developing transition agenda), and operational (mobilising actors and implementing experiments). Accordingly, key energy-related institutions are examined in terms of their visions, capacities and scope of influence using semi-structured interviews, roundtable discussions, and a survey. The conducted policy analysis suggests that the Palestinian energy sector started experiencing profound changes that affected all actors who had to adapt or transform to remain active, in addition to the rise of various multi-level actors. The analysis also shows that actors are more connected compared to the conventional energy system. Findings suggest that the spread of renewable technologies was not the outcome of only top–down schemes; instead, it is achieved throughout the collaboration of multi-level institutions and increasing reliance on horizontal-based governance networks. The paper uses examples to imply that it is possible to overcome the agglomeration of restrictions imposed on the Palestinian energy sector due to conflict if established regimes support governance networks and local-level initiatives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Several countries in the Middle East-North Africa (MENA) region have committed to increasing the percentage of renewable energy to reach 15–50% of the energy supply by 2030 [1]. These targets are based on the enhancement of energy security, economic development and encountering resources scarcity [2]. Subsequently, conventional energy supply chains will be subjected to fundamental transformation to shift its reliance on sustainable resources. Governing the energy transition into a sustainable path is a complicated process because of the diffusion of new decentralised technologies [3], the involvement of diverse multi-level actors [4], and the need for an original mix of policies [5].

Transitioning from conventional energy systems is not a change of technology only but also requires shifts in societal practices [6], institutions [7] and conventional governance models. Current societal systems are considered to be unsustainable from a long-term viewpoint and require structural changes to restore balance in the environment based on values of equity and justice [8]. Tackling these issues needs to reconsider the socio-technical, economic, institutional and environmental factors [9]. This is where transition theory is needed and can be effective, because it “provides an integrated analytical approach to conceptualise and understand complex, long-term processes of societal change as multi-causal, multi-actor, multi-level and multi-phase processes, and suggests a new mode of governance, transition management” [5].

The Middle East-North Africa (MENA) region, for instance, showcases a set of selection pressures imposed on their energy systems, characterised by volatile political situations, financial crisis and high rate of urbanisation. In addition to unavailability of natural resources in net importing oil countries [10]. Simultaneously, higher living standards, the growth of the middle class and the growing volume of industrial activities are leading towards a tremendous increase in energy demand [11]. These pressures are pushing MENA governments to find alternative routes to provide continuous energy supply from diverse sources such as renewable energy, which marks the beginning of the energy transition [12]. The case of Palestine was chosen because it captures the situation in various oil-dependent countries in the MENA region in three ways. First, it is a country that has been under conflict for decades, where energy security is leading political agendas focused on meeting the rising growth in demand and stabilising the energy market [13]. Second, Palestine primarily depends on energy imports from neighbouring countries, because in 1967, Israel occupied its territories and prevented the energy sector from extracting resources and generating its energy [14]. Third, since 2009, the energy market started experiencing profound changes that are valuable to examine. These changes are originated by the introduction of renewable energy, especially the diffusion of Solar PV rooftop and utility-scale initiatives (Table 5 in “Appendix”). The establishment of a legislative system accompanied these projects throughout releasing a series mix of policies, strategies and instructions supporting renewable energy (Fig. 5). Moreover, the market witnessed the rise of actors from multiple governance levels who are collaborating, launching initiatives, creating funding opportunities and implementing projects. Hence, the analysis provided in this paper shows that the energy transition in Palestine is not only a discourse, but also the energy system is already changing at a slow pace due to conflict forces.

Most studies in the MENA region focus on assessing the feasibility of renewable energy for energy supply from a technical viewpoint [10, 15, 16] whilst giving little consideration to socio-technical dynamics, governance and institutional issues [4]. Accordingly, this paper will tackle this gap using the transition management (TM) approach as a new integrative governance framework that connects theory and practice [8]. The transition management approach merges long-term ambitions with short-term action. It does so in multiple levels and phases by identifying the problems, then establishing a long-term transition vision and agenda, and creating networks to develop the process. To make the transition feasible and tangible, pilot projects are implemented before scaling up, followed by an evaluation phase for learning, and adaptation [17].

The purpose of this paper is to investigate the renewable energy transition in Palestine to provide scholarly analysis and aid in the upcoming stages of policy design. The research will focus on changes in policies, governing actors, networks and niche projects. The main research questions guiding this paper are (1) What is the value of promoting renewable energy transition in conflict contexts such as Palestine? (2) What are the key institutions governing the renewable energy transition and how it is achieved? (3) How does the agency of niche activities and governance networks influence the renewable energy transition? These questions will be explored throughout the three transition management abstraction levels because of their effectiveness in conceptualising complex systems. On the strategic level (section 64), this paper will show how problem structuring is a vital step and resulted in a significant change of perspective towards the potential of the renewable energy transition in the Palestinian context. After problem structuring, a transition vision is established to move forward. As for the tactical level (section 65), it is explored by analysing policy reforms (post-2009) in the Palestinian energy sector, which resembles the commencement of socio-technical transitions. This level also intends to highlight coalition building efforts, which could potentially empower institutions in conflict contexts through capacity building. Then comes the operational level (section 6), which focuses on mobilising actors and implementing pilot projects. A typology of the key governing actors will be presented concerning their visions, capacities, internal changes and niche projects to understand how they shape the transition (Fig. 1).

The conventional energy system is based on top-down and centralised governance structures. However, this research hypothesises that governing the renewable energy transition will be attained throughout multi-level actors horizontally coordinating resources and capabilities, with increased significance for both niche and local initiatives [18]. Instead of merely discussing transition outcomes as numbers, this research will incorporate qualitative methods, including interviews, roundtable discussions, a survey, and documentary analysis (Sect. 3). Qualitative methods are process-oriented, which will allow the researchers to untangle the interconnected complex issues at play [19].

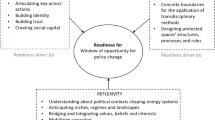

The Palestinian energy transition is considered to be in the pre-development phase [5], which is the most flexible in terms of changing paradigms. Accordingly, findings from this paper will contribute to the ongoing policy discourses by providing novel insights. Even though TM is not fully adopted by Palestinian institutions, the application of its holistic governance framework (Fig. 2) will highlight potential gaps in existing governance structures. The framework will also illustrate new ways to think about and guide the renewable energy transition. Moreover, results from this paper will be shared with Palestinian energy-related institutions in communication events (e.g. policy briefs). The available literature tends to concentrate primarily on low-carbon development in the Global North. Consequently, this paper will contribute to the field of energy transition by showing new perspectives from the Global South, where policy agendas are driven by energy security instead of decarbonisation. 40% of the population in Arab countries are estimated to live in conflict condition by 2030 [20]; hence, results may be extended to benefit other contexts under conflict with similar conditions to Palestine.

Source: Loorbach and Rotmans (2009) [17]

Activity clusters in transition management framework.

Transitions and transition management

Transitions are complex processes that structurally transform societal systems from one established stable system to another throughout the coevolution of technologies, policies, institutions, markets, and even behaviours [21]. Transitions are stimulated from a multitude of forces and have many outcomes. Transition theory is developed as multi-phase and multi-level (Fig. 1). These two analytical concepts are merged to understand the temporal dimension and the dynamics of transitions in terms of its state and potential to trigger fundamental change [8]. Transition management is the central approach utilised in this paper to provide insights about pragmatic governance strategies that are effective in guiding the energy transition into a sustainable direction.

The central assumption in transition theory is that societal structures undergo long phases of relative stability, proceeded by short periods of fundamental change, whereby new structures emerge as a result [8]. In energy transitions, structural changes do not occur in phases only, but they are also caused by multiple actors at different levels [5]. Therefore, it is essential to consider the analysis of the system as a whole, including the dominant structures, new configurations (niche initiatives) and the surrounding environment (context). The multiple level perspective (MLP), derived from technology and innovation studies, is one of the most frequently utilised models when analysing socio-technical transitions [22].

MLP embodies energy systems as regimes captured between two interrelated levels (Fig. 1). First is the landscape level, which includes social and physical dynamics such as policy paradigms, political coalitions, socio-cultural norms and economic conditions. Overall, it represents the external conditions for the regime level [23]. Second, are niche configurations at the bottom level, where innovations emerge by conducting pilot projects, in addition to developing new methods to fulfil social demand [24]. As for the regime level (middle), it provides the selection environment (existing conditions) for the introduction of novel technologies from the niche level [25]. Regimes are naturally stable and resilient to change, meaning that they can hinder innovations if incompatible with the regimes’ vision. This phenomenon is known as technological lock-in [26], which explains why regimes prefer stability over changing. Nonetheless, regime transitions are possible and achievable [27]. MLP suggests that niches do not automatically replace incumbent regimes. Instead, niches have to destabilise regimes, which can occur in various non-linear pathways such as proving their effectiveness, or when external pressures are applied on the landscape level [5]. This is witnessed in the Palestinian energy sector, where renewable energy projects are proving their feasibility and slowly attempting to find ways to become one of the main sources in the future energy mix (Fig. 8).

This research will employ the cyclical multi-level governance framework (Fig. 2) developed by Rotmans and Loorbach (2009) to analyse the Palestinian renewable energy transition from a pragmatic viewpoint. The framework distinguishes four activity clusters on four different levels [17]. First is the strategic level, where understanding and defining the problem take place. The purpose of this level is to develop a long-term vision that gives direction to social development throughout leadership capacity and strategic discussions. The purpose of the vision is about guidance more than imposing fixed set rules. Visions, even if disturbed, are necessary for conflict contexts such as Palestine. Visions ensure efforts are being directed in a particular direction, especially when the energy sector is heavily influenced by many forces. Second is the tactical level that aims to foster new networks and coalition amongst actors. The end product of this level is creating a transition agenda including new policies, strategies and medium-term goals at the sector level. Actors in Palestine are geographically separated because of the Israeli physical barriers (Fig. 4). For example, knowledge transfer of successful projects is difficult under current circumstances to the extent that actors are not aware of what is happening in other regions of the country (e.g. Gaza-Strip- and West-Bank). Therefore, TM encourages creating and maintaining networks as an effective way to unite and magnify efforts. The third activity cluster is the operational level, which entails translating the transition vision, and intermediate goals into concrete projects and practices. These efforts act as experiments for the sake of learning and refining the proposed strategies. Implementing pilot projects to enable the transition is crucial for Palestine, to explore ways to overcome obstacles because each region has its own set of complexities due to conflict. The last level is the evaluation and monitoring, which is a comprehensive review process that takes place on all levels and stages of the transition, to allow for reflection and adaptation. Evaluation is often overlooked in projects in Palestine. Hence, adopting the TM process will force involved actors to systemically achieve such a vital step to complete the TM cycle.

Many scholars have criticised transition management because it is considered as a type of social engineering, which focuses only on technocratic issues and overlooks external forces [28]. In other words, it can be argued that TM is not suitable for conflict scenarios, because it aims to manage the transition [29], where the notion of management in such contexts is often interrupted by external forces. However, the management aspect of TM is not meant to impose rules, but to challenge the notion of top-down approach by creating an arena for frontrunners to take action. Therefore, TM is beneficial in adverse situations as it offers a grand framework that supports actors to work in an organised and organic manner to facilitate the transition process. Whilst it is true that TM might be slowed down or interrupted due to uncertainties, it is essential to note that TM is ingrained in complex systems theory that deals with uncertainty, complexity, and unexpected outcomes [28]. In practice, it can accommodate activities that coevolve spontaneously without a clear order, and without distinction between actors to determine who is inside or outside the transition arena. Actors are not quite like transition managers; instead, they have a particular role in the transition process. Hence, TM is chosen in this paper because it is a model for exploring new paths through a reflexive policy that can handle risks and unforeseen events in adverse political conditions such as Palestine.

The literature on MLP tends to overlook the analysis of niche level interventions in the governance and development of the energy sector [30]. This research will approach this gap by considering the role of local authorities as niche actors in the energy sector. Although local authorities hold a minor position in the current centralised energy system, there is a growing literature tracing their increased engagement in the realm of sustainable energy. Fudge et al. [31] identified three reasons why local authorities are suitable as niche actors because of their political influence on local level; their capability of accessing and engaging with citizens (participatory); and their efficacy to deal with the implementation of distributed nature of new technologies in terms of planning and its related legal concerns (e.g. community microgeneration and district heating).

Methodology

Palestine’s energy sector exhibits various characteristics and challenges prevailing in the MENA region and other countries under conflict that are valuable to examine. This paper will focus on reforms post-2009 aiming to promote domestic electricity generation from renewable sources (primarily solar energy). Geographically, it will focus on the West-Bank because Gaza-Strip is challenging to access due to the political situation. The methodological approach aims to integrate the transition management framework in Fig. 2 with empirical reflections from data collected from a fieldwork conducted in January 2019. Therefore, a set of qualitative research methods will be applied including semi-structured interviews, roundtable discussions, surveys and documentary analysis, to identify intervention points [32] by highlighting changes in the institutional context and actors’ networks.

Qualitative methods are process-oriented allowing the researchers to obtain a precise and vivid representation of energy governance [19]. They are more flexible and reflective compared to quantitative methods [33]. Instead of merely focusing on the outcomes, qualitative methods are effective in examining complex systems, decisions, and various conditions that lead to the outcomes. A review of energy-related projects and initiatives was conducted (see Table 5 in “Appendix”) in conjunction with the ministry of energy to identify a list of the most relevant contacts. Then, a total of 28 semi-structured interviews were conducted during the fieldwork using nonprobability sampling method, in addition to two roundtable discussions (see Table 2 in “Appendix”). Interviews included government officials, private sector representatives, international development organisations, financial institutions and academics. The researchers are aware that bias might arise from this type of sampling process. However, the response sample includes all key energy-related actors from diverse projects across Palestine in different geographical areas and scales. Moreover, the sample covers the views of both existing and potential key actors related to the energy sector.

Questions and discussions with participants were divided into three categories: the dimensions of the Palestinian energy system and the changing status quo; policy approaches and projects of governing institutions; and interactions, partnerships and networks formed. Most interviews were held in Arabic, transcribed and analysed after translating them to English. An exploratory analysis was applied to highlight the main features of the energy transition and the governing institutions. Moreover, the analysis focused on spotting patterns of changes in response to the renewable energy transition.

In addition to the interviews that acted as the primary data collection method, a survey was distributed across 20 municipalities in Palestine. 11 responses were collected (including six of the biggest municipalities) and analysed by filtering the results, creating graphs and research themes from the data to draw findings. The purpose of the survey is to explore the engagement of municipalities in the energy sector; and moreover, to gauge to which extent municipalities are influencing the energy transition to assess whether they can be considered as one of the main actors responsible for delivering the transition agenda or not.

Documentary analysis was also conducted to analyse the case under examination. Official policy documents, regulations and instructions published by the government were collected and integrated into the analysis to determine the government’s position and comprehend the driving factors shaping the energy transition pathways (Section 5.1). Moreover, other studies and reports from international organisations, and other non-state actors were also analysed to obtain a comprehensive overview of the various perspectives in the Palestinian energy sector.

Strategic: problem structuring and envisioning

The purpose of the strategic level of TM is to establish a vision to mobilise potential and encourage actors to commit to an overarching goal that guides the transition. However, before formulating the vision, it is essential to agree on a new shared approach on how problems at the system level should be tackled. For the energy system, it means identifying and understanding the selection pressures that are disturbing the current system and demanding change. This section will begin by briefly discussing the key features of the Palestinian energy system, highlight the selection pressures, then present the new energy transition vision.

The geopolitical situation Palestine is experiencing yielded a distinctive energy sector compared to countries in the MENA region [10]. In 1967, the Palestinian territories were occupied by Israel, controlling all aspects of infrastructure. As a result, the Palestinian energy sector was dismantled from its generation and transmission capacities throughout a deliberate, incremental process resulting in a dependent consumer market [14]. Until now, Palestine meets its energy needs by being predominantly dependent on imports from neighbouring countries (Fig. 3). The Israeli Electric Corporation (IEC) provides more than 90% of electricity to Palestine [34]. The rest of imports are distributed between other neighbouring countries of Jordan and Egypt. In addition, Gaza Power Plant (GPP) supplies energy to Gaza-Strip with a generation capacity of 140 MW (currently rated at 90 MW).

Palestine showcases two completely different situations. Gaza-Strip with high unserved demand resulting in more than 8 h of daily electricity blackouts (GPP was destroyed by Israeli attacks in 2014) [35]. On the other hand, the West-Bank has a continuous power supply but with a high cost comprising 9% of household expenditure, which is the highest in the MENA region [36]. The challenge of achieving energy security is also complicated, especially with the annual upsurge in energy demand of an approximate average rate of 3.5% due to urbanisation and economic growth [11].

Interview data are showing that it is no longer feasible to depend on IEC for electricity imports. Because it is difficult to get permissions from IEC to expand the capacity of electricity imports to meet the growing demand (interviews 14 and 15), and it is cost inefficient [34]. From a legal perspective, the Palestinian energy sector requires substantial upgrading for the regulations and legislation to encourage niche activities whilst maintaining energy supply balance [38]. Another issue is Israeli legislation, which adds another layer of obstruction to introduce any change. From a technical point of view, Palestine is not allowed to build a national transmission system, nor it is easy to get permissions to establish new connection points where power can be discharged [39]. Moreover, Palestinian distribution companies are not allowed to connect their electrical grids (Fig. 9), which results in a high power loss during distribution [11]. These sample pressures imply that new solutions should consider electricity generation to be near production, which is achievable in case renewable energy technology is supported.

The imposed restrictions from the Israeli occupation as presented above are indeed the strongest force on the Palestinian energy sector. It is also one of the main reasons that pushed the Palestinian Government and energy-related actors to search and adopt alternative paths to progress the energy sector (interview 6). Instead of focusing on obstacles only, this paper seeks to shift the focus lens and highlight the available unexploited potential in the renewable energy sector under the current political situation. Several interviews stated that restructuring the energy sector has the potential to empower institutions, increase justice and create new partnerships (interviews 3, 5 and 23). All of this can put Palestine on the track to achieve energy independence. The change of actors’ perspective means that a structural change is required on the systems level, which is not confined to a change in technology only. Instead, it is a national necessity with numerous benefits. This change of perspective is equivalent to ‘problem structuring’ step introduced by transition management.

Based on the problem structuring phase, the Palestinian energy sector released a vision with four main pillars [37]: (1) increase the volume of domestic generation by exploiting local resources to reduce reliance on energy imports; (2) increase the percentage of renewable energy in the energy mix; (3) enhance and implement energy efficiency measures from production to consumption; and (4) reach energy security throughout diversification of sources, which includes establishing regional connectivity and power exchange with neighbouring countries. As the energy sector is still predominantly controlled by Israel, a new agreement entitled ‘Establishment of a New Market in Palestine’ was signed between the Palestinian and Israeli parties under the supervision of international bodies (Office of the Quartet) pursuing to transfer significant control and authority over the electricity sector in the West-Bank to PENRA [39]. Another agreement was reached in 2018 worth $775 million. In which the Palestinian Electricity Transmission Company (PETL) will control the delivery of electricity to the West-Bank, throughout the establishment of four high-voltage power plants [40]. For renewable energy, a strategy was developed in 2012 [41] by only PENRA and its related institutions (Fig. 7), in addition to international organisations for technical and financial assistance. The feasibility was based on conducted on-ground measures and studies alongside few established pilot projects that encouraged the government and many multi-level actors to consider investing in renewable energy systems. Although the energy vision was initially created in a top-down manner, the government is now more aware that the market expanded, where diverse actors and their experiences and business models should be included to be inclusive (interview 6). For example, PENRA invited a wide range of multi-level actors to contribute to the creation of the 2020 renewable energy strategy. Overall, it is essential to note that the origin of the Palestinian energy vision and strategies emanate from the necessity to both acquire independence from the Israeli occupation and advance the energy sector.

Despite the wide-ranging energy supply options the national vision aspires to develop, renewable energy is the only energy source that can be generated on Palestinian land under the current Israeli restrictions. In contrary, building a fossil fuel-based power station, for example, requires continuous fuel imports (for operation) and permissions, which is difficult to obtain from the Israeli side (RD1). Therefore, renewable energy projects are relatively easier to implement under current conditions. Solar, wind and biomass feature high potential in Palestine [10]. Solar energy holds the highest potential that can be relied upon with 3000 sunshine hours annually [15]. In heating applications, 57% of Palestinian households have solar water heater systems, which is the highest installation percentage in the Middle East [42]. Moreover, promoting domestic generation from renewable sources is not only socially and technically feasible but economically viable. In 2022, the cost of electricity per megawatt generated from renewables is expected to be cheaper than imported options [34]. Having an excellent solar potential, embedded social practices (abundance of solar heaters is an encouraging factor for the success of solar PV [43]) and economic feasibility are essential factors for decision-makers and investors when building their transition agenda in the tactical level.

The deployment of renewable technologies depends on the availability and accessibility of land. Hence, it is essential not to overlook the spatial constraints shown in Fig. 4. Regarding solar electricity, the technical potential (from PV and CSP) in the West-Bank is estimated to be 103 MW in areas A and B, and a staggering 3374 MW in Area C (not accessible due to Israeli constraints) [34]. Although renewable energy is crucial in the new energy mix for Palestine, it is still not waived from complexities of the conflict. The agglomeration of restrictions on the Palestinian land (Fig. 4) imposes tremendous pressures on decision-makers to find solutions to overcome the issue of land such as national rooftop schemes (see “Massader energy infrastructure developer (frontrunner)”).

The geopolitical administrative divisions by Osolo II accord in 1995, which divides the West-Bank into three categories: Area A, B, and C [10]. Area A designates full civil and security control for the Palestinian government. Area B allocates civilian issues to Palestine, but security under Israeli control. As for Area C, Israel administers both civil and security affairs. It is worth noting that 60% of Palestine’s land in the West-Bank is classified as Area C with more than 140 Israeli distributed settlements and more than 250 closures between Palestinian cities, town, and villages [10].

Tactical level: coalition building and developing transition agendas

After creating a new discourse and establishing a vision, a transition agenda should be created, which is the objective of the tactical level. This entails translating the vision into specific goals, and strategies whilst simultaneously building networks to innovate, manage, and sustain the process [8]. Transition images and paths are used as instruments to produce the agenda, which are defined as the collective images that formulate the overall vision, and the required routes to reach those images through intermediate milestones [17]. This section will briefly present the main transition paths and coalition building efforts.

Transition path

In the past decade, the Palestinian energy sector witnessed a drastic transformation from only importing electricity and petroleum products towards comprehensive reforms which call for energy supply diversification and infrastructure development. After analysing various documents and interview data from several actors, the energy transition in Palestine can be categorised into three main paths: renewable energy technologies (Fig. 5), energy efficiency measures (Fig. 6) and fossil fuel-based infrastructure. Collectively, this will require a new set of policy approaches and institutional setup.

Renewable energy laws and regulations (y-axis); renewable energy targets (x-axis). PENRA created few mechanisms and tools to expedite the execution of the renewable strategy, including feed-in tariffs, net metering scheme, and competitive biddings. Despite the slow start, 157 MW (16% of West-Bank capacity) of permits were granted by PENRA to the private sector be implemented until 2021 [50]; meaning renewable energy generation will increase by sixfold in 3 years.

Source: Author’s aggregation based on World Bank [11]

The graph is showing NEEPII target which is proposed to reduce the total consumption of electricity, during 2020–2030 by 5%, in addition to the three phases of the implementation strategy.

This paper will focus on the first path, which is the promotion of renewable energy throughout a series of new laws, regulations and strategies (Fig. 5). In 2012, the Council of Ministers issued a decision that established the legal base for the utilisation of renewables in Palestine and approved the “General Strategy for Renewable Energy in Palestine” (see Table 4 in “Appendix”). The target seeks to achieve 10% (130 MW) of electricity production from renewable sources by 2020 [41]. For the period 2020 until 2030, the energy authority (PENRA) expanded the target to achieve 500 MW (the target would be 300 MW in case Area C is not still not accessible). In addition to new policies and strategies, the declining prices of renewable technologies contributed to growth of renewable energy capacity. For example, the value of Solar PV systems imports increased from 590,000$ in 2013 to 3,915,000$ in 2017 [44].

The second pillar is energy efficiency measures, which can add a valuable contribution to energy security, where growth in renewable energy must be coupled with considerable measures to reduce energy demand. Energy efficiency measures are crucial, especially for the residential sector in Palestine, which is the highest consumption segment absorbing 62% of final energy [36]. A new strategy was established with the collaboration of PENRA, World Bank and French Development Agency (AFD) entitled “National Energy Efficiency Action Plan II (NEEAP II)”. Unlike previous plans that focused only on reducing energy demand (NEEAP I) [11], NEEAP II offers an additional layer that proposes to restructure the market. The plan seeks to introduce new sector-wide concepts such as demand side management as well as the utilisation of smart technologies (Fig. 6).

The third path is fossil fuels-based technologies and supporting infrastructure ranging from natural gas power stations to oil field exploration. Since energy transition in Palestine is triggered by the need to enhance energy security as a priority, the development of natural gas resources alongside renewables is significant for economic growth (interview 9). Unlike countries in the global north, where decarbonising efforts lead their energy agendas. All three paths presented above are developed with the intention of breaking from Israeli control and restrictions by diversifying energy sources (interview 5). This explains the support for renewable energy, primarily Solar PV, because it is relatively the easiest to implement compared to other paths.

Networking and coalition building

Coalition building is essential to enable the creation and implementation of the transition agenda. These efforts were observed in two situations; the first was in the development of an institutional setup that is capable of overseeing and steering the process. After extensive efforts in the last decade to formalise, legitimise and organise the energy arena, the Palestinian energy sector now displays proper legal and regulatory frameworks, a suitable market model, well-defined institutions, and identifiable market players as shown in Fig. 7.

The second type of observed coalition building was in the recently initiated Renewable Energy Group (REWG) in 2016 by the Applied Research Institute in Jerusalem (ARIJ) [45]. The purpose of creating REWG is to leverage existing resources, by bringing various stakeholders together from the government, private sector, NGOs and international community. This platform is the first of its kind in the Palestinian energy sector to be created for knowledge sharing and assembling actors on an equal footing to discuss pressing energy-related issues. The network mandates the formation of effective communication and coordination efforts between stakeholders to share best practices, experiences, and local knowledge to empower the renewable energy sector. In addition, REWG seeks to resolve contestation, inform policy, and conduct capacity-building activities.

Currently, the group is still in the phase of building the inter-organisational relationship between actors and expanding the membership by inviting relevant stakeholders; in addition to undertaking field visits to solar PV projects to share lessons learned. REWG launched an online “Innovative Energy Platform” that grants members the access to projects’ monitoring, publications, and training material, which enhanced the group’s internal management. Simultaneously, REWG is gaining more influence because of its hybrid structure comprising a diverse range of influential actors from the public and private sectors. For example, actors are able throughout this group to channel their feedback on energy policy directly to the government via its representatives. Even though the process of influencing policy in REWG is still informal, this network is expected to be more involved in future energy policy discourses.

Until now, actors in the Palestinian energy sector still have the 'competing mindset' more than the collaborating one (interview 28). The Palestinian energy transition can benefit from TM as it reinforces collaboration as one of the vital steps before moving to the implementation phase, which is needed in conflict contexts to unite efforts and minimise resistance to change.

Operational level: mobilising actors and implementing transition experiments

The focus of the operational level of TM is developing pilot projects (experiments) that use new ideas, insights and knowledge to make the transition vision and agenda tangible [17]. This level entails nurturing niches of innovation by engaging actors in networking events and concrete projects. The operational level is essential for social learning, coevolution of institutions and technology, and building the necessary confidence to scale-up operations [5]. Renewable energy investments in Palestine are currently widespread and made by diverse actors (Table 5 in “Appendix”). Before these investments were prevailing, international organisations in collaboration with Palestinian public institutions conducted few pilot projects. For example, Jericho’s Solar PV station is one of the earliest small-scale pilot projects that encouraged the government and many actors to consider investing in renewable energy systems (interview 22). Another example is the Palestinian Environment Quality Authority, which conducted successful pilot projects on schools’ rooftops. Following a phase of pilot projects, several utility-scale investments (1–5 MW) came from many local entrepreneurs with available lands in Area A and B and factory owners, especially in the northern part of Palestine such as Tubas, Ya’bad, and Ajeh. Section “Operational level: mobilising actors and implementing transition experiments” will present a typology of the multi-level actors involved in the transition. The aim is to highlight changes in implemented projects, organisational structures, and governance tactics.

Incumbent regime

Palestinian energy authorities

The Palestinian Energy and Natural Resources (PENRA) is established in 1995 and delegated to be the responsible institution for the stability of energy supply. In addition, PENRA is the official representative of Palestine with neighbouring countries to facilitate energy imports. Since 2009, PENRA was leading the sectorial and policy reforms. Concurrently, PENRA experienced profound changes both in terms of internal organisational change, and throughout the creation of few specialised institutions (PERC, PETL, PEC, and energy efficiency unit; see Fig. 7) to meet the wide-ranging demands of the energy sector. Whilst this shows the government’s understanding of the complexity of the energy transition, their role remains centralised as all decisions are made either by PENRA or institutions under its influence. However, these new institutions are responsible for producing significant structural changes in the energy sector throughout promoting niche initiatives.

The role of PENRA and its related institutions is focused on legitimation. They are responsible for translating the vision into policies to make domestic generation from renewable sources available and suitable for other actors. This engagement resulted in the creation of multiple policy instruments and regulations, which illustrates the government’s flexibility to respond to the increasing demand for renewables (Fig. 5). Interviews show that PENRA’s vision by 2030 aims to diversify the energy supply by increasing domestic generation from various sources whilst ensuring imports do not exceed 50% of the energy mix (Fig. 8). In addition to policymaking, PENRA has been involved in several niche initiatives and experiments themselves. For example, they launched the Palestinian Solar Initiative (PSI) in 2011, which entails the installation of solar PV systems on the rooftops of 1000 households. Although PSI completed only 400 homes [38], this residential scheme was suspended due to insufficient financial capabilities, because this program was subsidised using a fixed feed-in-tariff [46]. Despite the slow start, the government updated and released new instructions, laws and targets until 2030, to grant investors a stimulating environment to foster their confidence to participate.

Source: World Bank [34]

PENRA’s vision for 2030 is to diversify electricity supply and limit dependency on external sources to a maximum of 50%. Simultaneously, diminishing unserved demand in Gaza-Strip is a priority on the short-term.

Another successful project conducted by PENRA in partnership with few international organisations was using renewable energy to provide critical infrastructure with continuous energy supply. For example, powering surgical rooms in hospitals using solar PV where the gird was damaged due to the conflict. Instead of paying a range of US$6–US$10 million annually to provide electricity for hospitals in Gaza, PENRA is diverting a portion of the amounts to establish solar PV systems on hospitals’ rooftops. This scheme is an alternative to importing fuel for generators at a fraction of the cost. Despite the extensive damage caused on Gaza power plant and its import lines, efforts to harness the abundant energy of the sun through rooftop solar systems have increased by tenfold in Gaza-Strip [34]. After a series of feasible pilot projects, more than 500KW rooftop installations were completed by 2018. Moreover, 34 critical units within ten hospitals in Gaza are prepared with an expected cost of US$4 million [47]. Another similar initiative where PENRA leveraged renewable energy was in refugee camps and displaced communities, where the grid is not accessible. Renewable energy, especially solar, has significantly contributed to various humanitarian relief efforts for being easily accessible, safe, and economically and environmentally viable.

Electricity distribution companies

Despite the small size of Palestine, there are six operating distribution companies (DISCOs); five of them operate in West-Bank and one in Gaza-Strip (Fig. 9). Moreover, there are few additional distributors in the West-Bank, such as municipalities attempting to meet the demand of their geographically separated localities. The new mix of policies and regulations adopted by the government imposes challenges on DISCOs as they are required to change the way they operate substantially, as explained by JEDCO:

“We see change characterised in three ways: decentralisation, decarbonisation, and digitalisation; none of them is compatible with the way we operate…. we are using a new suite of tools and business models. Currently, the energy sector has ambitious strategies that oblige us to integrate and manage hundreds of megawatts of renewables into our grdid, which is less predictable and less controllable” (Interview 17).

Before the 2009 electricity sector reforms, DISCOs were the sole institution responsible for all electricity-related activities in their ‘island-like’ areas (cities and towns not connected due to Israeli barriers). The interviewed DISCOs are concerned about their position and future in the changing energy sector. One reason for this is that they are not systematically included in the sector decision-making process taking place at PENRA. They believe they have different insights, capacities and resources to offer. Moreover, interviews suggest that DISCOs perceive themselves until now (post-reforms) to be the principal decision-makers and visionaries for their areas. However, the nature of the renewable energy transition is pushing DISCOs to be more collaborative and align their visions with other actors if they want to cope with the ongoing structural changes.

In response to the changing energy landscape, interviews show that all DISCOs have seen considerable changes in their institutional structure, thinking, and methods. For instance, renewable energy departments in diverse forms are established inside the structure of DISCOs to facilitate the integration of renewable energy into their grid. Moreover, few companies such as JEDCO established new technical and academic training centres (e.g. a renewable lab at the Palestinian Incubator for Energy) to provide training sessions to staff, graduate students, and start-ups. The purpose of such efforts is to enable participants to join the new renewable energy market, in addition to raising awareness to members of the civil society. Developing digitalisation capacities is another aspect witnessed amongst DISCOs, which is reflected in decisions taken based on simulations, scenario planning, and investing in building computational proficiencies to aid strategic planning (e.g. NEPLAN software). DISCOs are also working on introducing elements of demand side management to enhance energy efficiency as a response to PENRA’s efficiency strategy (NEEAP II) by interacting with customers throughout pre-paid and smart meters [48].

The role of DISCOs is intermediary as they partially control and possess in-depth technical knowledge about the grid. This means that changes experienced by DISCOs are valuable and having them on board is essential to progress the transition. However, as the electrical grid is shared and controlled by Israel and was not initially designed to integrate generation from renewable sources and in a bi-directional manner, there is a limitation to the capacity allowed to integrate renewables. DISCOs are increasingly investing in their infrastructure to integrate renewable projects better. However, this process is complicated as DISCOs have to get permissions from the Israeli side for any expansion they aim to execute, as noted by TEDCO:

“Recently we released a bid to construct the first wind turbine in Palestine…at first, we faced rejection from Israel claiming it is for safety reasons…we re-adjusted the design several times in different ways such as reducing the overall height, even though it will reduce the generation capacity and increase the investment cost. Our tactics depend on perseverance…. we will continue adjusting the design, involve international parties, and negotiate; eventually, we will get our permission” (RD 1).

It is essential to bear in mind that the spatial aspects can drastically hinder or encourage DISCOs in executing more renewable energy projects. For example, Tubas, where TEDCO, is a small town in the north of West-Bank with a vast amount of land categorised as Areas A and B. TEDCO has more room to build solar plants compared to other DISCOs located in highly urbanised areas or zones categorised in Area C that are controlled by Israel. Uneven development might arise from these restrictions, and it becomes crucial to integrate spatial consideration in energy planning in the upcoming phases of the transition.

Niche actors, projects and networks

The Palestinian Ministry of Education and Higher Education (MoEHE) executed more than 154 solar PV projects by 2018 over public schools’ rooftops. Interview data imply that MoEHE is considered to be a dynamic player in the renewable energy transition. This is primarily because they are utilising the vast unused space on schools’ rooftops for microgeneration, given the geopolitical situation that limits access to land. Some of the early projects were established in cooperation with the private sector, the government and international originations as experiments before scaling up. After proving their feasibility, MoEHE hired a developer (Massader) to expand their operations.

Massader energy infrastructure developer (frontrunner)

The largest investment institution and the driver of the Palestinian economy, the Palestinian Investment Fund (PIF), established Massader in 2015 to implement and lead projects worth $2.5 billion in the energy field. Despite their young age, they launched the ‘Noor Program’ to accomplish projects with a total capacity of 200 MW by 2026, which represents 17% of Palestinian’s peak load [49]. Due to the well-established history between PIF and the government, PENRA opened the door for Massader to obtain the required regulations for their projects from the Palestinian Cabinet to establish and lead ambitious projects. Massader gained this access because of their technical expertise, financial capabilities, and national and international connections.

Massader was selected by MoEHE to be the project developer responsible for the installation of rooftop solar PV systems for 500 public schools [50]. The $35 million 4-year investment is planned to generate a capacity of 35 MW. Even though the project is planned to be completed in 2021, it influenced national plans to expand this project to cover all 2700 schools in Palestine (interview 7). Initial results are showing that the feasibility and availability of electricity microgeneration on rooftops is an effective solution to overcome land restrictions (interview 8). Nonetheless, distributed power generation over hundreds of buildings is a complex process because it requires liaising with numerous stakeholders. Therefore, project actors formulated a network to transfer the set of proficiencies they developed to achieve the target of covering Palestinian schools’ rooftops with solar PV systems.

The internal management of this network is handled formally throughout the creation of a project company in the form of a special purpose vehicle (SPV) structure (Fig. 10) that aims to assign clear scope of works to actors whilst ensuring all parties benefit in different ways. Furthermore, the program has a broader impact by creating awareness in public schools and weaving sustainable energy practices into Palestine’s teaching sphere (interview 6). This collaboration won the rooftop solar project for the year 2019 acknowledged by the Middle East Solar Association (MESA). The decentralised nature of renewables made Massader develop and use new business models that rely on connecting multi-level actors (Fig. 10). The model resulted in the establishment of novel partnerships whilst utilising hundreds of rooftops to compensate for the unavailability and inaccessibility of land due to conflict.

Source: Modified from [50]

Schools Project Business Model administered by Massader, which is responsible for mobilising the financials for the rooftop solar systems. The project will cover the full energy expenses of the involved schools, as well as providing a small amount of petty cash during high-generation months. Excess electricity will be sold to Palestinian DISCOs at competitive rates compared to imported electricity (0.35 USD/KhW), in addition to reducing technical losses as generation is close to the grid. At the national level, PENRA were able to obtain a special regulation from the Palestinian cabinet for this network to enable the business model over a large scale.

Municipalities

According to Articles (27) and (34) of the 2009 General Electricity Law [38], electricity distribution agencies, including municipalities, are considered illegal and are obliged to join an established distribution company. The law reduced municipalities’ involvement in the energy sector (interview 26). However, the fact that municipalities are still involved in electricity distribution (Fig. 9) raises questions about their potential role of in the energy transition. Survey results show that all 11 municipalities surveyed (including the biggest six municipalities) have reported projects implemented at different scales whether on their facilities with rooftop solar PV systems, or utility-scale (300 KWp—5 MWp solar station), or even investing in LED technology for street lighting.

Table 3 in Appendix shows that all surveyed municipalities have also developed either their own independent renewable energy plans (sustainable energy action plans, SEAP), or integrated specific goals in their overall strategic municipal plan as a response to the increasing demand on renewable energy. Some of the municipalities such as Tubas, Nablus, and Jericho have taken this further to increase their scope of influence by establishing strategic energy bodies to manage, plan, and promote renewable energy.

The analysis of local municipal activities indicates that they embody the agency of niche level, according to TM and MLP. For example, the Municipality of Ajeh (Jenin governate) reached 35–40% of its electricity from renewable sources. Furthermore, it has plans to reach 100% in case a transmission line is established to evacuate energy to other areas. Citizens and local investors collaborated to raise capital to support the municipality to build solar energy stations in Ajeh. The model in Fig. 11 demonstrated its effectiveness because the municipality has a broad citizen access and can mobilise local investors for renewable energy projects, which is difficult to be attained by higher authorities’ centralised approach. Moreover, the municipal boundaries include abundant land under the Palestinian control (Areas A and B) to establish solar plants.

Municipalities are the closest institution to citizens and have been historically the main legitimate players even before the establishment of the Palestinian government [51]. Their role in the energy sector decreased in the past two decades and so their involvement in decision-making at the national level (interview 26). However, survey results show that municipalities have been voluntarily engaged in the field of renewable energy, and initial indicators are showing that their efforts are effective. It is worth mentioning that 11 municipalities were chosen by Clima-Med (Acting for Climate in South Mediterranean) to conduct Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plan (SECAP) (interview 1). Therefore, the role of local authorities should be further investigated, and systemically included in the transition vision, agenda, and projects to accelerate the transition towards sustainable energy system.

Other key actors

The presence of International Development Organisations (IDOs) in sustainable infrastructure projects in Palestine is substantial. IDOs are considered to be a dynamic actor as they facilitate (between the Palestinian and Israeli side), strengthen and support the renewable energy sector at different levels (strategic to operational) through policy transfers, projects and initiatives. The review of case studies shows that IDOs aim to rehabilitate the energy sector to reduce Palestine’s dependency on foreign aid and power their operations to meet the growing energy demand. Currently, IDOs’ role is significant in Palestine because of their financial and technical contribution. However, this means that IDOs can influence the way energy policy formulation and projects’ implementation. Gradually, their involvement is expected to have more impact on the shape of the energy transition as the sector continues to grow. This might shift Palestinian’s dependence from one source to another, which is a subject to be considered in future research.

Financial institutions are also emerging on the energy sector radar. The establishment of the ‘Revolving Fund’ project is a good example to illustrate how the inclusion of diverse actors such as banks in decision-making can yield in innovative proposals by identifying and developing unexploited potential in the realm of energy transition. Currently, each line of ministry in Palestine is responsible for powering up their buildings with no common standards for energy fixtures. However, all energy bills are paid by one entity, the Ministry of Finance (MOF). Since ministries do not pay the bills themselves (not part of their expenses), they have little or no incentive to reduce their energy consumption. To overcome this obstacle, the ‘Revolving Fund’ was created to enable investments in energy efficiency (EE) measures, which aims to reduce the energy bills of Palestinian ministries paid by MOF [52]. The unique business model (Fig. 12) grants one ministry at a time with funds to reduce their energy consumption. Then, a part of these savings from the implemented EE measures are transferred back to the fund to finance another ministry, creating a revolving effect to benefit various projects.

Source: Author’s illustration based on PEC [52]

The financial flow model of the revolving fund; closed continuous cycle where savings from one project are mobilised for another energy efficiency project.

Financial institutions such as banks operate in a unique political and economic environment, where the adverse political conditions led to strengthening their capabilities to confront the various risks facing the financial sector in Palestine (interview 24). Lack of certainty and occupation control over the economic resources in Palestine has implications such as difficulties in reaching Palestinian areas (e.g. Gaza-Strip, Area C) due to Israeli military barriers and security measures. This entails additional costs for money transfers and providing further logistical requirements for the branches. Moreover, the absence of local currency, in addition to trading in three currencies in Palestine, is not encouraging for long-term lending, a crucial issue for renewable energy projects.

The financial sector, with the help of the Palestinian Monetary Authority (PMA), was able to develop tools and measures necessary to overcome such risks, in addition to launching conferences (e.g. Renewable Energy and Finance Opportunities in 2016) [53]. PMA issued instructions and procedures that focus on the overall stability of the Palestinian financial system such as adding requirements for capital buffers and reserves, enhancing risk management, and strengthening the internal control environment. These improvements attracted new projects like SUNREF, which was launched in January 2019 in collaboration by AFD to provide local banks with an amount of 28 million euros to finance renewable and energy efficiency projects [54]. The initiative targets households and businesses to establish and foster their small-scale generation projects. Accordingly, financial institutions are considered now one of the key actors in the Palestinian energy transition. As banks focus on financial feasibility, spatial considerations might be overlooked, an aspect that should be taken into consideration in future policy documents to avoid uneven development of renewable energy projects.

The ongoing efforts towards renewable energy transition are showing growth in governance networks. Actors mapping in Fig. 13 shows that horizontal interactions are prevailing in the renewable energy transition compared to conventional energy system that relies on top-down policy networks. Even though the government is the official body responsible for the energy sector, fieldwork findings are showing new emerging patterns between multi-level actors. These interactions are steering the renewable energy transition and generating transition dynamics.

Conclusion

In response to pressures imposed on the Palestinian energy sector, a new vision was released [37] to increase domestic generation and limiting imports to a maximum of 50% by 2030. This paper argued that new governance models are required to conceptualise and guide the transition into a more sustainable direction. Transitioning towards renewable energy is not a change of technology only, but also a change in all societal domains and institutions. Accordingly, this paper employed the transition management framework to answer the questions of who is governing the renewable energy transition in Palestine, and in what ways it is achieved. The choice of a Transition Management approach provided a better understanding of the renewable energy transition. TM framework offered a useful conceptualisation of the energy sector, between the strategic, tactical and operational levels of governance, to analyse the involvements of multi-level actors and complement the existing governance structures.

Overall, the new strategies and projects related to the Palestinian energy transition are already changing the energy system but at a slow pace due to conflict forces. The analysis showed that actors are now closer to each other compared to the conventional energy system. This is because of efforts to connect actors to execute exemplary projects, which require a variety of capabilities and scope of influence from them. Moreover, interviews show that actors are keeping active and connected to remain updated and accumulate new knowledge to cope, adapt or transform to encountered change. However, actors’ efforts are still dispersed because of the geographical separation from conflict. Hence, the future of the Palestinian energy transition depends on how successfully actors maintain collaboration throughout periodic meetings and networks.

After examining the key renewable energy initiatives, it is concluded that the value of the energy transition in Palestine is beyond technological change, but a road for independence. Moreover, the engagement of various multi-level actors raised attention towards the value of renewable energy as a solution for the persistent problems in the energy sector. The analysis also showed that governance capabilities are still not comprehensive or fully developed because traditional governance models are embedded in the institutional structures. Nevertheless, governance tactics in the field of renewable energy are progressively changing as actors are showing flexibility and gradual growth in networks and niche projects.

Regarding the governing actors, fieldwork findings showed that all of them experienced change and engaged with niche activities in one way or another. Three trends were spotted where change was manifested in actors. First, the establishment of new institutions to fill gaps in the energy sector and to reorganise and monitor the energy market (Fig. 7). Second is the creation of new renewable energy departments within the internal structure of institutions. Third is the rise of new actors into the energy sector radar. The constellation of actors is found to be adding value to ongoing and future developments. Actors are bringing novel perspectives and expertise to tackle the various energy issues on different levels, instead of a single institution responsible for directing the entire process. It is worth mentioning that the conflict is embedded in the Palestinian culture, which often blurs actors from moving forward. However, the energy transition is giving actors the chance to consider conflict forces to be one of the obstacles amongst others (e.g. economic, technology) to be able to maneuverer and implement their projects. For example, the flexibility and ease of execution of Solar PV systems allow actors to implement their project on a utility scale, and if rejected because of the political situation, to rescale or even change the location until approved. Unlike fossil fuel-based projects, such as establishing a gas-fired power plant, where conflict forces can hinder the entire development (e.g. gas imports are controlled by Israel).

The analysis of niche actors indicates that when existing regimes support them, it substantially enhances their performance, which is in line with the initial research hypothesis. This is witnessed in the government’s effort to support new institutions like Massader, which is accelerating the transition throughout novel schemes. The same can be applied to municipalities, where this paper contributed by investigating their current and potential role in the transition. This is to assess whether municipalities can be a potential candidate to be supported by high-level authorities. Survey results confirm the initial assumption and literature [31, 55, 56] by highlighting that local authorities’ role is significant in the energy transition. Moreover, the analysis of local activities indicates that they embody the agency of niche level, according to MLP, which is challenging to be identified and executed by higher authorities’ centralised methodology.

Interview results revealed that the spread of renewable technologies was not the outcome of only top-down schemes; instead, throughout the collaboration of multi-level institutions and increasing reliance on horizontal-based networks, which is also in accord with both the researchers’ hypothesis and the various literature that support networks over singular centralised efforts [57]. The emergence of governance networks in the Palestinian energy sector implies that a single institution would be incompetent in managing the substantial socio-technical changes [18].

The application of the transition management approach on the Palestinian renewable energy transition revealed a few intervention points and recommendations. They include (1) acknowledge and deal with the energy system as a complex but adaptive system whilst appreciating the context; (2) be more inclusive by reconsidering the role of existing and potential multi-level actors; (3) encourage new combination of strategies, technologies, and systematise knowledge sharing through governance networks; (4) be reflexive during the governance process by monitoring interventions and revising policies accordingly; (5) align and connect national policies with the local level; and (6) breakdown conflict forces and assign them to TM levels to assess how and where it influences the energy transition to overcome them.

This paper employed the transition management framework to acquire a better understanding of the renewable energy transition in Palestine. Future research should be directed towards an in-depth analysis of each level and phase of the transition. For example, how the transition agenda should address the spatial features of the energy transition; an aspect raised by many actors in various projects. Finally, research should assess transition pathways and whether existing capabilities and resources in Palestine can achieve them.

Abbreviations

- CSP:

-

Concentrated solar power

- DISCO:

-

Distribution Company

- GEDCO:

-

Gaza Electricity Distribution Company

- GWh:

-

Gigawatt hour

- GPP:

-

Gaza power plant

- IEC:

-

Israeli Electric Corporation

- IPP:

-

Independent power producer

- HEPCO:

-

Hebron Electricity Distribution Company

- IDO:

-

International Development Organisations

- JDECO:

-

Jerusalem District Electricity Company

- JICA:

-

Japan International Cooperation Agency

- MENA:

-

Middle East and North Africa

- MW:

-

Megawatt

- MLP:

-

Multiple level perspective

- NEDCO:

-

Northern Electricity Distribution Company

- PCBS:

-

Palestinian Central Bureau of Statics

- PEC:

-

Palestinian Energy and Environmental Research Centre

- PENRA:

-

Palestinian Energy and Natural Resources Authority

- PERC:

-

Palestinian Electricity Regulatory Council

- PETL:

-

Palestinian Electricity Transmission Company

- PMA:

-

Palestinian Monetary Authority

- PSI:

-

Palestinian solar initiative

- PPA:

-

Power purchase agreement

- PV:

-

Photovoltaic

- SELCO:

-

Southern Electricity Distribution Company

- TEDCO:

-

Tubas Electricity Distribution Company

- TM:

-

Transition management

References

IRENA: Renewable energy in the Arab Region: overview of developments. International Renewable Energy Agency, Abu Dhabi (2016)

Verdeil, É., Arik, E., Bolzon, H., Markoum, J.: Governing the transition to natural gas in Mediterranean Metropolis: The case of Cairo, Istanbul and Sfax (Tunisia). Energy Policy 78, 235–245 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2014.11.003

Broto, V.C.: Energy landscapes and urban trajectories towards sustainability. Energy Policy 108, 755–764 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2017.01.009

Kucharski, J.B., Unesaki, H.: An institutional analysis of the Japanese energy transition. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 29, 126–143 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2018.07.004

Loorbach, D., Brugge, R.V.D., Taanman, M.: Governance in the energy transition: practice of transition management in the Netherlands. Int. J. Environ. Technol. Manag. 9(2/3), 294 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1504/IJETM.2008.019039

Williamson, O.E.: The new institutional economics: taking stock, looking ahead. J. Econ. Lit. 38(3), 595–613 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.38.3.595

Andrews-Speed, P.: Applying institutional theory to the low-carbon energy transition. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 13, 216–225 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2015.12.011

Loorbach, D.: Transition management: new mode of governance for sustainable development: nieuwe vorm van governance voor duurzame ontwikkeling = Transitiemanagement. Internat. Books, Utrecht (2007)

Huang, P., Castán Broto, V., Liu, Y., Ma, H.: The governance of urban energy transitions: a comparative study of solar water heating systems in two Chinese cities. J Clean Prod 180, 222–231 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.01.053

Juaidi, A., Montoya, F.G., Ibrik, I.H., Manzano-Agugliaro, F.: An overview of renewable energy potential in Palestine. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 65, 943–960 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2016.07.052

Njore, M.M.: West Bank and Gaza—Energy efficiency action plan for 2020–2030. World Bank Group, Washington, D.C (2016) (ACS19044)

Alabduljabbar, A.A., Efird, B.: Preface. Energy Transit. 5, 9 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41825-017-0001-8

MAS: Encouraging Solar Electricity Production in the OPT: Is It Just a Slogan? Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute, Ramallah (2015)

Jabary Salamanca, O.: Hooked on electricity: the charged political economy of electrification in the Palestinian West Bank. In Working paper (February) presented in the symposium “Political Economy and Economy of the Political”, Brown University, pp. 1–25 (2014)

Ismail, M.S., Moghavvemi, M., Mahlia, T.M.I.: Analysis and evaluation of various aspects of solar radiation in the Palestinian territories. Energy Convers. Manag. 73, 57–68 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2013.04.026

Kousksou, T., et al.: Renewable energy potential and national policy directions for sustainable development in Morocco. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 47, 46–57 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.02.056

Rotmans, J., Loorbach, D.: Complexity and transition management. J. Ind. Ecol. 13(2), 184–196 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-9290.2009.00116.x

Sorensen, E., Torfing, J.: Theories of democratic network governance, 1st edn. Palgrave mcmillian, UK (2007)

Locke, L., Spirduso, W., Silverman, S.: Proposals that work: a guide for planning dissertations and grant proposals. Sage, London (2014)

Abdellatif, A., Pagliani, P., Hsu, E.: Leaving no one behind: towards inclusive citizenship in Arab countries, U. N. Dev. Programme, p. 48 (2019)

Cherp, A., Vinichenko, V., Jewell, J., Brutschin, E., Sovacool, B.: Integrating techno-economic, socio-technical and political perspectives on national energy transitions: a meta-theoretical framework. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 37, 175–190 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2017.09.015

Geels, F.W.: Technological transitions as evolutionary reconfiguration processes: a multi-level perspective and a case-study. Res. Policy 31(8–9), 1257–1274 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(02)00062-8

Geels, F.W., Schot, J.: Typology of sociotechnical transition pathways. Res. Policy 36(3), 399–417 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2007.01.003

Kemp, R., Schot, J., Hoogma, R.: Regime shifts to sustainability through processes of niche formation: the approach of strategic niche management. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 10(2), 175–198 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1080/09537329808524310

Smith, A., Voß, J.-P., Grin, J.: Innovation studies and sustainability transitions: The allure of the multi-level perspective and its challenges. Res. Policy 39(4), 435–448 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2010.01.023

Unruh, G.C.: Understanding carbon lock-in. Energy Policy 28(12), 817–830 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-4215(00)00070-7

Fouquet, R.: The slow search for solutions: lessons from historical energy transitions by sector and service. Energy Policy 38(11), 6586–6596 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2010.06.029

Rotmans, J., Loorbach, D., Kemp, R.: Transition management: its origin, evolution and critique. Erasmus University, Rotterdam (2007)

Shove, E., Walker, G.: Caution! Transitions ahead: politics, practice, and sustainable transition management. Environ. Plan. Econ. Space 39(4), 763–770 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1068/a39310

Bolton, R., Foxon, T.J.: Urban infrastructure dynamics: market regulation and the shaping of district energy in UK cities. Environ. Plan. Econ. Space 45(9), 2194–2211 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1068/a45575

Fudge, S., Peters, M., Woodman, B.: Local authorities as niche actors: the case of energy governance in the UK. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 18, 1–17 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2015.06.004

Hartley, J.: ‘Case study research’, in Essential Guide to Qualitative Methods in Organizational Research. SAGE, London (2004)

Sarantakos, S.: Social research, 4th edn. Palgrave Macmillan, New York, NY (2013)

Badiei, S., Foster, V., Coma-Cunill, R., Kwesi, S., Ogua, E.: Securing energy for development in the west bank and Gaza. World Bank, Washington, D.C

OCHAOPT: Gaza Strip electricity supply. United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs - occupied Palestinian territory (2019). https://www.ochaopt.org/page/gaza-strip-electricity-supply. Accessed 18 May 2019

Missaoui, R., Ben Hassine, H., Bida, A.: Energy efficiency indicators in RCREEE member states, Regional Center for Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency, Cairo (2014)

PENRA: ‘Palestine Power Sector Overview. In: Presented at the Sectorial Working Group Meeting. Ramallah, Palestine (2019)

PENRA: Renewable energy in Palestine achievements and challenges. In: Presented at the Palestinian Energy & Natural Resources Authority (PENRA), Ramallah

PWC: Establishment of a new market in Palestine, Ramallah, Project Document (2017)

Scheer, S., Sawafta, A., Al-Mughrabi, N.: Israel to shift West Bank power supply to Palestinian Authority in $775 million deal, Reuters, Jerusalem (2018)

PENRA: General Strategy for Renewable Energy in Palestine. Palestinian Energy and Natural Resources Authroity (2012)

PCBS: Press Release on Results of Household Energy Survey (2015). http://www.pcbs.gov.ps/post.aspx?lang=en&ItemID=1439. Accessed 14 May 2019

Huang, P., Liu, Y.: Renewable energy development in china: spatial clustering and socio-spatial embeddedness. Curr. Sustain. Energy Rep. 4(2), 38–43 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40518-017-0070-8

Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics: Renewable energy investment opportunities. Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, Ramallah (2017)

ARIJ: ARIJ held a workshop to create a Palestinian working group for renewable energy (2016). http://www.arij.org/component/content/article/126-latest/775-arij-held-a-workshop-to-create-a-palestinian-working-group-for-renewable-energy.html

Al-Arda, M.A.D., Sharqieh, O., Taha, M.: Recommended national sustainable urban and energy savings actions. Cleaner Energy Saving Mediterranean Cities (2015)

WHO: WHO Special Situation Report Gaza, occupied Palestinian territory October to November 2017. World Health Organization, Gaza (2017)

JDECO: Jerusalem District Electricity Company Annual Report. Jerusalem District Electricity Company, Ramallah, Annual Report (2017)

Willuhn, M.: Palestine to bring online its first PV plant, at 7.5 MW. PV Magazine International (2019). https://www.pv-magazine.com/2019/05/24/palestine-to-bring-online-its-first-pv-plant-at-7-5-mw/. Accessed 28 May 2019

Massader: Public Schools Pv Systems Rollout. Ministry of Higher Education (2017)

Pro Poor Integrity (PPI) and Palestinian Local Authorities. The Applied Research Institute, Jerusalem (ARIJ), Bethlehem (2009)

PENRA: Promotion of energy efficiency and renewable energy in strategic sectors in Palestine. Palestinian Energy and Natural Resources Authority, Ramallah, Information Report (2016)

Palestinian Monetary Fund: Renewable Energy and Finance Opportunities, Palestine International Banking Conference Opens on 21st of November. http://www.pma.ps/Media/PressReleases/TabId/343/ArtMID/957/ArticleID/1014/Palestine-International-Banking-Conference-Opens-on-21st-of-November.aspx. Accessed 16 Nov 2016

AFD: SUNREF Palestine: the lending programme that promotes green growth, French Development Agency, Ramallah, Functional Report (2019)

Bale, C.S.E., Foxon, T.J., Hannon, M.J., Gale, W.F.: Strategic energy planning within local authorities in the UK: A study of the city of Leeds. Energy Policy 48, 242–251 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2012.05.019