Abstract

The present paper takes a corpus-pragmatic approach to an issue traditionally situated at the interface of sociolinguistics, grammatical prescriptivism and syntax: the use of the hypercorrect structures <X and I> and <I and X> in object position and British and American English speakers’ usage of such pronoun binomials as prestige constructions. Here, we dedicate significant space to the meta-methodological level pertaining to the corpus-linguistic challenges entailed in systematically identifying relevant occurrences of coordinated noun phrases that feature at least one nominal component unambiguously case-marked. We use a self-compiled corpus of 14,165,810 words of transcribed telecinematic discourse in order to not only establish the extent of any hypercorrect usage, but also to see it in relation with unmarked and both grammatically correct and incorrect uses of the subject and object forms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction: Object and Objectives of This Study

Yet all too often nowadays we find people saying, or even writing ‘Between you and I’ or ‘From the wife and I’ or ‘To Maggie and I.’ This oddity, which seems to have emerged only in the last twenty or so years, presumably arises from a feeling of discomfort about using the word me, a sense that it is somehow impolite or ‘uneducated.’ (Cochrane, 2003: 14 ff.)

What Cochrane classified as an emerging phenomenon in the early 2000s seems to have further increased in salience since then, manifesting in numerous examples of specifically spoken spontaneous speech. Examples such as (1) and (2), which we ourselves came across by chance, suggest a tendency amongst English native speakers to use the subject pronoun I where it should, prescriptively speaking, be the object case-marked pronoun me. They also confirm Angermeyer and Singler’s observation that ‘[t]hese days it is the form that celebrities […] use when chatting on the Tonight Show’ (2003: 199).

-

(1)

[…] we had a very lovely conversation. […] That’s what happened with Donald and I. (Alicia Silverstone on Stephen Colbert’s Late Show, June 2018); transcribed from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jm1lWu_xEaI&feature=youtu.be, from approx. 4:00)

-

(2)

When my father would go to work on the weekends, […] he would take my brother and I and drop us off at this music store. (Lucy Liu on Stephen Colbert’s Late Show, April 2018); transcribed from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lJDuuKq9BU4&feature=youtu.be, from approx. 1:20)

The present paper takes a corpus-pragmatic and methodological approach to a sociolinguistic issue traditionally situated at the interface of grammatical structure and syntax: the subject-case marked <I> in <X and I>-structures in object position (as in (1) and (2)) – a form that stands in contrast to both the prescriptively correct <me> in object position and the correct, but rather markedly high-style use of <I> in subject position, as shown in (3).

-

(3)

This was a situation where we were frustrated, both Reese and I, at the things we were being offered. (Nicole Kidman on Stephen Colbert’s Late Show, November 2017; transcribed from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TIKeDV69158, from approx. 05:00)

While the grammatically incorrect use of I instead of me in object position has been receiving attention and criticism by a good number of (popular-scientific) publications for years (see, e.g., Batko and Rosenheim, 2004; Cochrane, 2003; Norris, 2016), and even though a number of scholars have remarked on and noted the <and I>-structure’s incorrect usage growing more salient in use, hardly any studies have made the effort to corpus-linguistically zoom in on this issue to add a quantitative layer to this discussion. The present study attends to this gap by focusing on some of the corpus-pragmatic challenges involved in not only classifying coordinated structures like <X and I> but also in finding and identifying them within larger corpora to begin with. In fact, the focus and aim of the present study is a methodological one, demonstrating the analytical (manual as well as corpus-assisted) steps necessary for systematically isolating hypercorrect uses of subject-case pronouns in what we shall here be calling pronoun binomials. This will be showcased by employing a corpus of 14,165,810 words of transcribed scripted telecinematic discourse (2,755 episodes from 44 US/UK scripted TV series), which we compiled and analyzed on the platform Sketch Engine. We introduce a detailed search and coding protocol that demonstrates a rather wide array of coordinated (pro)noun phrases as our starting point, and, ultimately, zeroes in on the patterns <X and me/myself/I> and <me/myself/I and X>. As such, this paper should be able to serve as a replicable template for efficiently conducting corpus searches for pronoun binomials and similarly evasive functional patterns.

Before we attend to our methodological corpus-pragmatic core sections, we will put the study object into its relevant academic context. Thus, the section titled “Reviewing the Relevant Literature and Settling on Suitable Terminology” provides a literature review of the (re)search history on coordinated noun phrases (NPs) in general, and on the formulae <X and I>, <X and me>, <I and X> and <me and X> in particular (cf. “On Traditionally Prescriptive Tendencies in Describing Coordinated (Pro)Noun Formulae”). So far, the only corpus-based study into hypercorrect phenomena we are aware of was produced by Collins (2021). We continue with a discussion of the sociolinguistic and pragmatic aspects of correct and incorrect/hypercorrect strategic uses of prestige constructions (cf. “A Methodological Focus on Coordinated Phrases, Formulae and Binomials”). The section “Research Questions and Data” addresses our data and the methods apply to systematically search the former (“Tracking Down Hypercorrect Pronoun Binomials: A Corpus-Pragmatic Methodological Demonstration”). The section “Results: Our Focus Dataset of Potentially Hypercorrect PBs in Object Position” presents and discusses our results. “Conclusions, Outlook and Limitations of Our Study” concludes the paper.Footnote 1

Reviewing the Relevant Literature and Settling on Suitable Terminology

This section reviews the literature available on coordinated pronoun patterns, prestige constructions and hypercorrection.

On Traditionally Prescriptive Tendencies in Describing Coordinated (Pro)Noun Formulae

The distinctive use of coordinated subject and object pronouns, especially of <you and I> versus <you and me>, appears to have almost exclusively been an issue addressed by grammarians and syntacticians (e.g., Biber et al., 1999; Jespersen, 1949; Quirk et al., 1985). Prescriptive grammarians would generally agree that the use of the subject pronoun I instead of the object pronoun me after a preposition (e.g., between) is unequivocally unacceptable. Several standard grammars do, however, descriptively acknowledge the inverse case, i.e., that native speakers themselves do show tendencies to incorrectly use the object form of the first person singular personal pronoun me in place of I in particular patterns: ‘Although the prescriptive grammar tradition stipulates the subjective case form, the objective form is normally felt to be the natural one, particularly in informal style’ (Quirk et al., 1985, Sect. 6.3).Footnote 2 Our examples (4) and (5) show this widely accepted, yet, technically, grammatically incorrect use of object pronouns in subject complement position, while (6)–(8) provide contrasting examples of forms that are correct but would generally be perceived as highly odd or archaic, which is why we mark them with asterisks.

-

(4)

It was them [they] at the door.

-

(5)

She is faster than him [he].

-

(6)

*It was we [us] who called.

-

(7)

*Mary is smarter than they [them].Footnote 3

-

(8)

*Mary and they [them] went to the movies.

Grammar and syntax experts have conventionally taken inherently and legitimately rule-based approaches to the correct and incorrect use of certain pronoun forms in their designated syntactic positions – an overall approach that can also be found in most discussions within the field of Language Education. However, since the 1980s, there seems to have been something of a divide emerging between academics who do, in fact, take more descriptive and investigative approaches to the issue on the one hand (cf. Crystal, 1988; Honey, 1995; Krejčová, 2009, 2011, 2012), and non-academic practitioners who take a rather strong stance in favor of pertinent rules to be followed on the other (cf., e.g., Batko and Rosenheim, 2004; Cochrane, 2003; Norris, 2016).

Studies into language change and sociolinguistic focus areas have, overall, been taking more descriptive approaches to the (in)correct use of subject and object pronoun forms, and pragmaticist Louise Cummings (2018: 7) has passionately rejected lay accounts of the type that use condemning labels such as ‘bad English’ (e.g., Cochrane, 2003) altogether. Even so, it seems that sociolinguists and pragmaticists overall have so far missed this traditionally grammar-claimed issue as a whole as one that is right down their own alley, considering that the (hypercorrect) use of prestige formulae is, essentially, positive face work on one’s own account. This, however, is not the focus we will be taking in this paper.

A Methodological Focus on Coordinated Phrases, Formulae and Binomials

Finding and identifying formulae such as <X and I>, <X and me>, etc. in a comprehensive manner can be a highly complex procedure, but even talking about them often proves difficult. Any attempt at labelling or classification runs the risk of neglecting the high level of variability that such formulae contain, both in terms of their exchangeable (pro)nominal components on the one hand and of the (implicitly hierarchical) order of entailed components on the other.Footnote 4 Therefore, one of the initial issues to settle for the sake of cohesive metalanguage in this paper concerns our notional decisions. What adds to this challenge is that, as far as we could find, little academic interest has been expressed in finding an appropriate label for these formulae or attending to their use overall. Many sources merely mention the phenomenon in passing. The few sociolinguistic and variational studies that have taken an interest in our object of investigation mostly adopt and adapt Quirk et al.’s (1985) notion of ‘coordinated pronouns’. Angermeyer and Singler (2003) speak of ‘co-ordinate [sic] noun phrases in object position’, Krejčová (2011, 2012) uses the notions ‘coordinated constructions’ and ‘coordinated phrases’, and Quinn (2005) talks about ‘pronoun case in coordinates’.

Unlike some smaller-scale studies (e.g., Boyland, 2001), Angermeyer and Singler (2003) take a relatively wide scope in considering pronoun variations between <me and X>, <X and I>, <X and me>, <myself and X> and <X and myself>. In addition to providing a thorough review of the relevant literature, they offer quantitative insights into a mixed dataset of 549 relevant ‘co-ordinate noun phrases’ collected from experimentally framed oral interviews with American English native speakers on the one hand, and authentic examples of coordinate NPs observed in use in their own everyday conversations on the other.

Note that none of the notions discussed so far seems to entirely fit the formulaic patterns we are investigating in this study: the notion of ‘coordinate(d) noun phrases’ seems too much restricted to a syntactic pattern, while the notion of binomial – which has been used in no study we are aware of in reference to coordinated pronouns – describes coordinated elements of potentially any open word class. Both the syntactic features and the formulaic makeup of coordinated (noun) phrases are entailed within the notion of binomials, i.e., such formulae consisting of two words coordinated by and or or that are ‘syntactically symmetrical, i.e., belong to the same word class and have the same syntactic function’ (Hatzidaki, 1999: 136; see also Kopaczyk and Sauer, 2017).

At the same time, binomials have also been defined based on the lexical meaning they entail. It has been argued that the two elements in binomials typically display traits such as synonymy (kith and kin, safe and sound, fair and square) or antonymy (black and white, more or less, make or break), often in combination with rhyming or assonance (meet and greet, hustle and bustle, out and about) or alliteration (tried and true, mix and match, now or never). This being said, binomials are inherently formulaic in their makeup. We contend that our object of study represents a very special kind of binomial, which we shall call ‘pronoun binomial’ (PB), believing that this notion is fitting both on a morpho-syntactic and a semantic level. For one, pronoun binomials contain two elements, coordinated by and or or, with at least one of these elements being a pronoun and the other, if not itself a pronoun, an element (e.g., a noun phrase) that could be replaced by one. Semantically speaking, the elements in a PB may not demonstrate the standard relations mentioned above, but they do have an implicitly co-hyponymic relationship. We thus choose this notion not only because it will allow us to use a referring label that is both broad and specific enough, but which also acknowledges that the characteristics of the elements exceed the scope of mere morphology and syntax altogether.

Hypercorrect Pronoun Binomials

As Quirk et al. (1985: Sect. 6.5) suggest, ‘the prescriptive bias in favour of subjective forms appears to account for their hypercorrect use in coordinate noun phrases in “object territory”’, as is the case for between you and I, or as for Jane and I. What is more, they argue that ‘x and I is felt to be a polite sequence which can remain unchanged, particularly in view of the distance between the preposition and I’ (ibid.). Labov (1964) explains hypercorrection as being driven by the lower middle class as they attempt to emulate upper middle-class speakers of the prestige variety. Thus, lower middle-class speakers may latch onto a linguistic form that is used by prestige speakers but use it in contexts where the latter might not (i.e., in object position). Equipped with insecurely set hypercorrect examples, speakers will thus likely overgeneralize the rule and follow their intuition that the prestige form is the correct form in all positions.Footnote 5 In that regard, between you and I (and other PBs following prepositions) has been particularly salient in discussions on prestige and hypercorrect patterns (see, e.g., Honey, 1995; Krejčová, 2009).

We follow Angermeyer and Singler (2003) in assuming that English has competing orders for pronouns/NPs in coordination (e.g., Jane and me/I vs. me/I and Jane), which essentially needs to be feasibly transferred or translated into our corpus-pragmatically methodological approach. They call these ‘vernacular’ versus ‘polite’ orders, with the former postulating that the first person is put first in a coordinate phrase (which is what we call ‘informal’), whereas the polite order aligns with the modesty rule, i.e., requires the first person pronoun to be placed last (2003: 176; cf. Quirk et al., 1985: 335). Within these orders, they distinguish three different patterns with regard to case-marked elements, i.e., the standard pattern (cf. (9), (10)), the vernacular pattern (cf. (11)), and the polite pattern (cf. (12)).

-

(9)

Robin and I will go there later today.

-

(10)

He cornered Robert and me before the meeting.

-

(11)

Me and Sasha are going to the video store. (Angermeyer and Singler, 2003: 177)

-

(12)

The teacher divided the prize between Sasha and I.

We will refer to what Angermeyer and Singler (2003) call ‘standard’ as the grammatically correct use of pronoun binomials (so long as they are, prescriptively speaking, used correctly either in their subject or object position in a sentence); their ‘vernacular’ covers what we call colloquial or informal (i.e., object-case pronouns used in subject (complement) position that are commonly used but, prescriptively, considered incorrect or bad/informal style); their ‘polite’ pattern is what we refer to as hypercorrect pronoun binomials whenever such subject-case pronouns are used (grammatically incorrectly) within a binomial in object position (see also Silverstein, 1986/1995: 532). As opposed to the terms ‘standard’ and ‘vernacular’, we prefer the more graspable (yet, inherently prescriptive) notions ‘correct’ and ‘incorrect’ within the specific context of this study and its methodological nature. By object position we refer to direct, indirect and prepositional objects. Examples of PBs in their correct, incorrect and hypercorrect use are given in Table 1.

Research Questions and Data

This section introduces our research questions and elaborates on the data we analyze.

Hypotheses and Former Findings to Be Checked

Based on earlier studies that have paved some of the way for us, here are some previous findings that we seek to systematically examine in our own corpus-linguistic methodological approach:

-

i.

As suggested by grammarians and sociolinguists alike, object pronoun forms are saliently used in both slots within the pronoun binomial type of coordinate noun phrases, and these PBs are used in both subject and object positions (cf. Quinn, 2005: 107).

-

ii.

Given that the formula between you and I has been discussed and addressed so saliently, is it more frequent than other hypercorrect PBs following other prepositions?

-

iii.

The PB you and me is the most frequent coordinated NP in both subject and object position in Angermeyer and Singler (2003)’s data, followed by you and I, me and him, and he and I.Footnote 6

-

iv.

Krejčová (2011) proposes that <and I> is a fixed unit in itself, which would go against more traditional approaches (e.g., Boyland, 2001; Honey, 1995) that have considered <you and I> as a fixed unit altogether. We will explore whether our data affirms this notion.

-

v.

Speakers will not stick exclusively to one variant (e.g., the hypercorrect nominative or objective), but will fluctuate between them (see Sobin, 1994: 57, 1997, 2009; Angermeyer and Singler, 2003). We shall test this hypothesis by looking into specific scripted characters in a selection of TV series in our corpus.

In addition to the hypotheses just mentioned and based on the existing literature, our corpus allows us to also pose the following questions:

-

vi.

Are hypercorrect uses significantly more frequent in the UK series than in the US samples in our corpus, given that UK English is usually associated with a higher level of prestige?

-

vii.

Does the saliency of hypercorrect pronoun forms in binomials have an accepting effect on the hypercorrect use of single case marked pronouns after prepositions (e.g., *important for I)?

The Data: A Self-Compiled Corpus of TV Series Post-Transcripts

As our target phenomenon pertains to current (or at least fairly recent) occurrences of the type of PBs described above in both British and US English, our text type of choice – in alignment with, e.g., Bednarek (2018, 2020) – is originally scripted telecinematic dialogue between characters which was transcribed at the post-production stage. Our corpus compilation focused on serialized telecinematic fiction that had been originally written and filmed in US or British English and had aired at any point since 1990. We made every effort to include a variety of genres and settings, and our selection was made accordingly, though it was of course constrained by the authors’ being aware of a series’ existence, and then by the availability of good quality transcripts.Footnote 7 All in all, our corpus includes 2,755 episodes from 44 TV series (25 US, 19 UK) that originally aired in the last 25 years (1994–2019), resulting in a compiled corpus of all in all 14,165,810 tokens.Footnote 8

Our corpus data are homogenously fictional (being transcriptions of originally scripted TV series dialogues) but, as we argue, still inherently authentic and naturally occurring for two reasons: For one, we did not compile our corpus with a view to the phenomenon of interest but first and foremost with the goal of collecting data of a homogenous nature; second, we did not elicit the data in any way. The quality of our dataset overall will not only help us establish the extent of any hypercorrect usage within a relatively large text corpus, but also allow us to see it in relation with unmarked and both grammatically correct and incorrect uses of the subject and object forms. The latter is a desideratum that we specifically pursue by adhering to corpus-linguistic methods here: The present study is the first to not only identify and describe hypercorrect pronoun binomial patterns in absolute numbers in a dataset, but to also carve out their occurrence, among other things, in relation to the absolute number of pronoun binomial constructions in our corpus.

Tracking Down Hypercorrect Pronoun Binomials: A Corpus-Pragmatic Methodological Demonstration

Our main focus in this paper is on the methodological demonstration of how we conducted, refined and adapted our corpus search protocol in order to efficiently and comprehensively extract correct, incorrect and hypercorrect pronoun binomials from our corpus. Certain aspects of this process were particularly challenging and required us to not only conduct several rounds of testing and refining for our search protocol but also to complement the latter with meticulous manual analyses. For one, we had to figure out what the PoS (parts of sentence) tags in Sketch Engine would and would not find; for another, there was no efficient way to electronically search for or determine whether a PB was occurring in subject (complement) or object position, which is why the latter had to be done manually.Footnote 9

What We Were Looking for

We built and expanded considerably on Boyland (2001), who focused on hypercorrect/correct <X and I> versus correct/incorrect <X and me> only,Footnote 10 Angermeyer and Singler’s (2003) solely quantitative study, and Krejčová (2011), although her methods and data are rather opaque. Table 2 gives an overview of the various possible combinations of different components within the four elements of the PBs we were targeting in our initial search of the corpus.Footnote 11

Translating Search Strings into Query Language

An early step was familiarizing ourselves with the Corpus Query Language (CQL) used for advanced concordance searches in Sketch Engine.Footnote 12 We additionally compiled a dummy corpus made up of prototypical sentences of different lengths that contained a variety of prepositions, verbs in various tenses and modes, different pronouns, numerous types of NPs, and so forth in order to test out individual queries.Footnote 13 We then went on to translate the search strings into CQL, considering all of the following categories:

The category ‘preposition’ (E1) contained all the prepositions listed in Query 1. Note that Krejčová (2011) had only considered six of them (i.e., like, between, for, from, by, at, of) in her corpus study.Footnote 14

[lc="about|above|after|against|apart from|at|before|behind|beside|besides|between|beyond|by|except |for|from|including|in|into|like|near|next to|of|on|over|to|toward|towards|under|with|without”] |

The category ‘Verb phrases’ (E1; Query 2) contained all verb phrases tagged as VV in Sketch Engine. This covers verbs in all tenses, modal verbs as well as non-standard (and contracted) forms such as gonna.Footnote 15

[tag="VV.?“] |

The category ‘Conjunctions’ (E3; Query 3) was limited to the coordinators and and or.

[lc=“and|or”] |

The category ‘Pronouns’ (E2 and E4; Query 4) included those pronouns tagged as personal (PP) in Sketch Engine (I, you, he, she, it, we, you, they, me, him, her, us, them), but excluded possessive pronouns (PPZ) that function as determiners, such as my, your, his, their. Reflexive pronouns (myself, yourself, himself, herself, itself, ourselves, themselves) and more unusual pronouns (ye, thou, thee, y’all) had to be added manually.

[tag="PP.?“ & tag!="PPZ.?“ | lc=”.*self|.*selves” | lc="ye|thou|thee”] [lc="y”] [lc=”.*”] [lc="all”] |

The category ‘Noun phrases’ (E2 and E4; Query 5) contained any combinations of 1–7 words tagged by Sketch Engine as nouns (N), proper nouns (NP), prepositions or subordinating conjunctions (IN), predeterminers (PDT; all, both), possessive pronouns (PPZ; my, her, their), determiners (DT; the, a), numerals and cardinal numbers (CD; 4, fifteen), adverbs (RB), or adjectives (J). Additional determiners not caught by tags (thy, yon) were added manually.

[tag="N.*|NP.?|IN.?|PDT.?|PPZ|DT|CD|RB.*|J.*” | lc="ye|yer|thy|yon|yonder”]{1,7} |

Our trialing found that none of the PoS tags would recognize all of the possessive pronouns that can stand alone rather than functioning as determiners to a noun (mine, yours, his, hers, ours, theirs, thine), so we added a manual search. The second line of the query targets his (standalone possessive pronoun only) while aiming to eliminate its determiner homonym (E2 and E4; Query 6).

[lc="mine|yours|hers|ours|theirs”] [tag="IN.?“]? [lc="his”] [tag!="N.*|NP.?|IN.?|PDT.?|PPZ|DT|CD|RB.*|J.*” & lc!=”.*ing”] |

These ‘building blocks’ (Queries 1–6) were then assembled into full CQL strings to search our corpus for the types of PB listed in Table 2 using Sketch Engine.

Paring Down the Hits

We soon decided to exclude the results of searches 3 and 6 (of the type ‘[preposition/verb] [noun phrase] and/or [noun phrase]’; cf. Table 2)Footnote 16 and to focus on the results generated by queries for Types 1, 2, 4 and 5, which yielded a compiled total of over 18,000 ‘raw’ hits. We began paring these down manually by correcting hits where necessary, by eliminating hits that were not dialog (e.g., stage directions/descriptions, transcribed lyrics to non-diegetic songs) and by eliminating doublesFootnote 17. To facilitate further analysis, Elements 1–4 were tagged for their word classes.Footnote 18 Some items that contained more than two coordinated elements (e.g., (13), (14)) were additionally tagged as ‘3 + elements’. At this stage and later, we eliminated those hits where E1 was not a verb or preposition but, e.g., a subordinating conjunction as in (15), or in which neither E2 nor E4 actually contained a personal pronoun.Footnote 19

-

(13)

I’m trying to save you and me and him and your father. (Billions, S1E6)

-

(14)

She never said anything directly bad about me or the diner or anything else concerning me. (GG, S5E7)

-

(15)

He was on this case long before you and I came into the picture. (Suits, S3E13)

Next, the verbs and prepositions in E1 were examined as to whether they demanded the object or subject case. Then, the words in E2 and E4 (first and second position) were checked to see if they gave a clear indication of being in subject case (SC; e.g., she, they) or object case (OC; e.g., her, them), or not (IND; e.g., you, proper names, noun phrases). Items where neither E2 nor E4 contained an element that showed clear case marking (you and your brother, Hank and yourself, etc.) were excluded from further analysis. In the case of pronouns ending in -self/-selves, we differentiated between reflexive use (16) and non-reflexive use (17).Footnote 20 The former were excluded, but those items in which the -self/-selves pronoun could plausibly be substituted with its non-reflexive twin (e.g., me) were seen as containing the OC and kept.

-

(16)

I was so concerned with saving myself and my reputation I pushed all my friends a way. (B99, S2E19)

-

(17)

that’s what it’s come to between my wife and myself. (John from Cincinnati, S1E3)

Those hits that remained in the pool were manually classified with regard to the diatopical allocation (broadly, US or UK English spoken in dialogues) and their setting (‘contemporary’, i.e., set at the time of production, meaning the 1990s or later; ‘20th century’, i.e., set between the 1950s and 1970s; ‘(pseudo-)historical’, i.e., set in the 1910s or earlier, or set in a medieval or renaissance-like fantasy setting).

Preliminary Analysis and Final Focus Criteria

We decided to conduct a first examination of the reduced dataset. A total of 77 hypercorrect hits were found. In all of these, hypercorrect subject case occurred after the coordinator (in E4). In two hits ((18), (19)), both E2 and E4 were hypercorrect.

-

(18)

But if you can’t tell the difference between he and I, perhaps you need to ask the General for your old job back. (Prison Break, S4E17)

-

(19)

Are you suggesting that Victoria’s sanity depends on she and I having no more children? (Victoria, S3E3)Footnote 21

Of the 77 hypercorrect phrases, only (20) did not contain the hypercorrect first-person singular pronoun I at all, and only (21) featured the coordinator or.

-

(20)

Okay, just the idea of you and he and all these women. (Friends, S7E5)

-

(21)

That is a vital part of the great city of Meereen, which existed long before you or I and will remain standing long after we have returned to the dirt. (GoT, S5E9)

Given the generally low incidence of the coordinator or and of hypercorrect pronouns other than the first person singular, we decided to exclude both from our final focus dataset.Footnote 22

Results: Our Focus Dataset of Potentially Hypercorrect PBs in Object Position

Hypercorrect Forms by Syntactic/Grammatical Structure

Our finalized focus dataset included only PBs (a) which were introduced by a preposition or transitive verb phrase, (b) whose elements were coordinated by and, and (c) in which the hypercorrect use of the subject-case pronoun I did occur or plausibly could have occurred (i.e., which contained me or myself).Footnote 23 All results discussed in this section are based on this final focus dataset, i.e., those items from the full corpus of 44 TV series that fit the final selection conditions just described. The 977 hits in this subset were tagged with the six category markers listed in Table 3.

For the last category, hits containing the structure <me and X>, though grammatically correct, were categorized as ‘informal style’, rather than ‘okay/correct’, if the second position (E4) referred to a person (cf. (22), (23)); i.e., if the PB violated the modesty rule (see “A Methodological Focus on Coordinated Phrases, Formulae and Binomials” and “Hypercorrect Pronoun Binomials”).

-

(22)

Sarge gave me and Scully the case. (B99, S1E17)

-

(23)

You’re hiding from me and the kids. (Ozark, S2E6)

In the vast majority of cases, the element that was not the pronoun I, me or myself referred to a person rather than a concept or a non-human entity, meaning it contained either a proper noun or name, a personal pronoun, or a noun phrase referring to a person. Overall, only 43 out of 977 items (4%) contained a different type of element (e.g., between me and Armageddon, kiss your oxen and me). Among the 73 hits in the focus set containing the hypercorrect <X and I>, all the elements in E2 referred to a person.Footnote 24 28 were pronouns (1 she, 1 he, 26 you), 35 were names or proper nouns, and 10 were possessive + noun (e.g., your brother).

Of the 977 PBs in the final focus dataset, 751 (77%) were introduced by prepositions, 226 (23%) by a verb. Among the 73 hypercorrect hits, the distribution was similar, with 50 (68%) preceded by a preposition and only 23 (32%) by a verb.Footnote 25 Among the 751 PBs that began with a preposition, 50 (7%) were hypercorrect. Surprisingly, while between (278), about (100), and with (94), occurred most frequently, both overall and among the hypercorrect hits (13, 5, and 4, respectively), these were not the prepositions that were most likely to trigger <X and I>: Among all the PBs introduced by between where the hypercorrect form could have occurred (278), it only actually did so in 15 (5%); for about, the proportion was identical (5 out of 100; 5%). This frequency was over four times as high for the preposition of (11 out of 48; 23%), and somewhat higher for for (11 of 88; 13%), from (1 of 14; 7%), and on (1 of 15; 7%). Among the 226 PBs introduced by a verb, 23 (10%) were hypercorrect.Footnote 26

We also noticed that it is not just what precedes a PB, but also what follows it that is relevant for the occurrence of a hypercorrect form. After categorizing the text to the right of the PB as ‘plain infinitive’ (18 hits, 4 of them hypercorrect), ‘to-infinitive’ (37/13), ‘present participle’ (36/13) or ‘other’ (886/43), we found the following: The percentage of the five non-hypercorrect PB types followed by a plain infinitive, a to-infinitive or a present participle ranged from 0 to 8% (61 out of 904; 7%, for the five types cumulatively). For hypercorrect forms, in contrast, this proportion was 41% (30 out of 73; cf. examples below).

Hypercorrect forms were far more likely than non-hypercorrect forms to be followed by a present participle: Of the 36 PBs followed by an -ing form, 13 (36%) were hypercorrect, with the remaining 23 (64%) divided up among the 5 non-hypercorrect types. Within these, this percentage ranged from 0 to 4%, and was 3% cumulatively (23 hits out of 904); within the 73 hypercorrect phrases, 13 (18%) were followed by a present participle (e.g., (19), (24), (25)). Interestingly, of the 13 hypercorrect PBs followed by an -ing form, only 1 was introduced by a verb (see), and 9 were introduced by the preposition of.

-

(24)

This is about Stella and I finally communicating. (HIMYM, S4E6)

-

(25)

There are pictures of you and I shaking hands. (HoC, S2E7)

Hypercorrect PBs were also overrepresented among those PBs that were followed by a to-infinitive: Of 37 total occurrences, 13 (35%) were hypercorrect (e.g., (26), (27)).Footnote 27

-

(26)

There’s only one thing for you and I to discuss. (Prison Break, S4E6)

-

(27)

Rory, I appreciate you wanting Mom and I to get along. (GG, S1E6)

The case was similar though slightly less pronounced among PBs followed by a plain infinitive: 4 of the 18 total occurrences (22%) were hypercorrect (cf. (28), (29)). All these 4 were introduced either by the verb make or let.

-

(28)

I think that’s what made Liz and I work. (The Blacklist, S3E20)

-

(29)

Why don’t you go in there and get drunk with them, let the Sheriff and I finish our talk? (Deadwood, S3E8)

Hypercorrect Forms by Source Material (Setting, English Variety)

After considering the structural aspects, we turned our attention to the characteristics of the source material in which the various PBs had occurred. As mentioned above, each series had been categorized as using either UK or US English, and according to its temporal setting (contemporary, mid-twentieth century, or (pseudo-)historical; cf. Table S6). What needs to be stressed is that counting mere frequencies of PB types would have been tremendously misleading, even with the great differences in tokens per series mitigated: Had we decided to just go by occurrence per 100,000 tokens (see Table S4), then the series with the highest occurrence of the hypercorrect PBs <X and I> would be Gilmore Girls, Suits, Reign, Friends, The Blacklist, Mad Men, How I met your Mother, The Big Bang Theory, House of Cards, and The West Wing. However, we also found that these series contain a much higher occurrence of all six types of target PBs per 100,000 tokens. We therefore decided to analyze the number of places where any of these six types, but especially the type <X and I>, could plausibly have occurred and then actually did or did not.Footnote 28 By doing so we acknowledged that there were choices to be made on the part of the scriptwriters or performing actors, who would go with their own preferred form or the form they felt fit for the character and setting being portrayed. Therefore, unless stated otherwise, frequencies in the following refer to the number of occurrences of a specific PB type (e.g., the hypercorrect <X and I>) relative to the total number of places it could have occurred (i.e., the sum of all six PB type occurrences in the final focused dataset of 977 hits).

A brief analysis of the two PB types containing the non-reflexive myself (26 occurrences in total, cf. Table S3) found that only 12 out of 44 series contain these at all, with the highest frequencies appearing in The Crown, Merlin, The West Wing, Sherlock and House of Cards.Footnote 29The West Wing and House of Cards are both set in contemporary US Washington politics, but other than that, the only thing these five series have in common is that their protagonists tend to be upper class / educated.

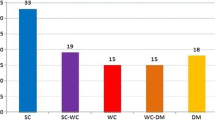

When focusing on our main target, hypercorrect PB tokens of <X and I>, we found that they were more frequent in British than in US English (14% vs. 6%), due perhaps in part to the stronger prevalence of the informal <me and X> pattern in the US English series (53% in US vs. 34% in UK).Footnote 30 A look at series separated by setting showed that <X and I> occurred more often in series set in the mid-twentieth century (16%) or in (pseudo-)historical worlds (15%) than in contemporary settings (6%). A further subdivision by English variety + setting shows that the occurrence of hypercorrect forms within contemporary series was virtually identical in US and UK English (6%). However, in the non-contemporary settings, two subcategories contain only one series and the proportions of settings within the English type is far from balanced (percent of tokens from contemporary series: within UK = 21%; within US = 94%), so we took a closer look at individual series for a clearer picture. The series with the highest frequency of <X and I> are Victoria (UK; 1840s), Mad Men (US; 1960–1970), Merlin (UK; medieval fantasy setting), and Reign (UK; 1557 onwards). All four are set at least 50 years before the present day; three use British English.Footnote 31 Another thing they have in common is that their protagonists and most other characters hail from a high-status social background, with the three UK series being set in and around the (English) royal court, and Mad Men revolving around well-to-do higher-ups at a prestigious New York advertising firm. These findings confirm our expectation that the hypercorrect prestige pattern <X and I> is being employed in our data to produce speech that sounds particularly posh, royal or noble and overall historical. However, other series that fit the (pseudo-)historical type do not show this pattern,Footnote 32 whereas several series that are very much contemporary and not necessarily set among a high-prestige social set are not that far behind in their use of <X and I>.Footnote 33

This leads us to the final issue we sought to tackle, i.e., the question of whether hypercorrect patterns are consistently scripted into the mouths of particular characters or whether the hits are distributed unsystematically and in alternation with correct or informal uses, as suggested for authentic and naturally occurring speech (cf. Sobin, 1994: 57). To analyze this more closely, we selected those 11 series with at least three hypercorrect instances each; in the 9 series where we were still able to retrieve the broadcast episodes or transcripts with speakers listed, we labeled each utterance from within the focus set with the diegetic speaker. This gave us a set of 494 utterances (47 of them hypercorrect) attributable to 159 distinct speakers. 100 of the speakers had only one utterance each (8 of them hypercorrect) and were therefore not analyzed any further. Of the 59 speakers with at least two utterances, 37 did not use any hypercorrect forms at all. Among the 22 characters who did use the hypercorrect PB in object position at least once, there was only one who used it consistently and exclusively: Prince Albert in Victoria did so in 5 out of 5 utterances, once doubly so (see (19)). The only other characters who come close are Lane Pryce in Mad Men (2 out of 2; the character is an Englishman) and Luc Narcisse in Reign (2 out of 3; a Frenchman rendered in British English). The other 19 speakers, who had between 2 and 33 utterances each, used the hypercorrect between 1 and 3 times (i.e., in 3–50% of the utterances where they could have), showing that characters, for the most part, mix correct and hypercorrect forms. In fact, 9 characters noticeably use both hypercorrect and non-hypercorrect forms following the same preposition (about, between, for, of, with; see, e.g., (30)–(34).

In our data, hypercorrect PBs tend, for the most part, to be spread across characters. Within certain shows, however, it becomes clear that hypercorrect forms are put into the mouths of certain characters but not others. For instance, among the six main characters in Friends, Chandler, Monica, Rachel and Ross do not use any hypercorrect forms, while Joey (the loveable dimwit) is responsible for 3 out of the 4 hypercorrect forms that occur in the series (the fourth is uttered by Phoebe). This reflects claims about hypercorrect prestige constructions often being used by the less educated seeking to adapt to the style of the higher educated. The fact that Joey also uses the <and I>-pattern in subject position elsewhere and furthermore make use of <and me> in both object and subject positions seems to demonstrate his (scripted) unawareness of when the grammatical and stylistic rules pertaining to I and me in PBs do in fact apply (cf. (30)–(34)).

-

(30)

Look, Ross, about, about Rachel and I. Listen, you don’t have to worry about that, okay? (S10E2)

-

(31)

All right! I’ll try! But if I can’t, you can stay with Chandler and I until you get settled. (S4E4)

-

(32)

Listen uh, you wanna get some dinner with me and Kathy tonight? (S4E5)

-

(33)

I’m saying maybe you and I crank it up a notch. (S5E16)

-

(34)

Hey! Don’t you hang up on me! I’ll marry you and me right now! (S7E23)

In House of Cards, both main characters Claire and Francis Underwood are highly educated and intelligent, yet all three hypercorrect forms in the series (cf. (35)–(37)), are uttered by Francis, while neither Claire nor any other character uses them. Francis’ speech is, however, not comparable to that of Joey in Friends or other characters: Apart from the three hypercorrect forms, Francis’s use of PBs is consistently correct in object position, and interestingly, there is no single instance of <X and me> or <me and X> in subject position scripted into his mouth. Neither does he use PBs with the non-reflexive ‘myself’. These choices may have been deliberate on the writers’ part so as to create his idiosyncratic, consistently high style.

-

(35)

He’s doing it as a favor to the president and I. (S1E9)

-

(36)

There are pictures of you and I shaking hands. (S2E7)

-

(37)

Someone or someones tried to make my wife and I lose the election by keeping underground today. (S5E7)

Further analyses focusing, for instance, on whether the characteristics and relationship of the speaker and addressee(s) influence the use of hypercorrect PBs may yield interesting results but are beyond the scope of this paper and the size of the dataset.

Conclusions, Outlook and Limitations of Our Study

In this paper we have focused on correct vs. hypercorrect uses of pronoun binomials in object position following a verb or preposition, e.g., the use of between you and I vs. between you and me/between me and you. A core concern of ours was to demonstrate our corpus-pragmatic search protocol, which we applied to a self-compiled corpus, some 14 million tokens in size and made up of transcribed dialogue from 44 US and UK television series (1994–2019). Our final focus dataset of PBs that this corpus-linguistic protocol generated is fairly small, which is why no rigorous quantitative conclusions about the general linguistic behaviors of the diegetic speakers in our data can be drawn. Even so, the size of the dataset in relation to the corpus of TV series dialogue from which we extracted it shows that a complex, multi-layered search protocol is necessary in a study dealing (maybe especially) with formulae that seem utterly common if not trivial, like <you and I> and <me and you>.

Given that our main focus in this paper was set on corpus-linguistic methods and decisions to be made in order to generate a dataset of specific interest, the following points deserve mention. As we have made transparent, a complex sequence of analytical steps went into extracting a set of, at the end of the day, only 977 relevant PBs for close analysis. These items were introduced by either a verb phrase or preposition that requires the object case; they contained two elements – one of them a first person pronoun (I, me, myself), the other a pronoun, name or noun phrase – coordinated by and. Based on our mixed analyses, former findings can be affirmed or refuted as follows:

-

i.

As expected, our data, too, demonstrates that object pronoun forms are used in both the first and second positions within PBs, and that PBs containing these object pronoun forms can be found within both subject and object position.Footnote 34

-

ii.

Between, about and with were the prepositions that appeared most frequently in absolute terms (i.e., preceding both correct and hypercorrect PBs) within our focus dataset. Contrary to expectations, however, the prepositions of, for, from and on were more likely to precede or ‘trigger’ the hypercorrect <X and I> (as opposed to, e.g., <X and me> or <me and X>) than between, about or with. We also found that hypercorrect forms were far more likely than other (correct) forms to occur when followed by a plain infinitive, a to-infinitive or a present participle.

-

iii.

In Angermeyer and Singler (2003)’s data, the PB you and me was the most frequent coordinated noun phrase in both subject and object position, followed by you and I (20 hits), me and him (13 hits), and he and I. In our focus dataset (in which we looked only at the object position and includes only PBs containing I, me, or myself), the most frequent diads containing only pure pronouns are you and me (194 hits), me and you (34 hits), you and I (26 hits), her/him and me (10 hits), me and her/him (10 hits).Footnote 35 However, we found far more occurrences of diads containing one pronoun coupled with a reference to a third person in the form of a name/proper noun or noun phrase (also including a possessive) (e.g., Emma, Dr. Clarkson, the President, your brother).Footnote 36 Our data therefore also finds a high prevalence of <you and me>, but further comparison is difficult due to the differences in the datasets and the approach to analysis.

-

iv.

Our data supports Krejčová’s (2011) proposal that <and I> is a fixed unit in itself: after all, the <and/or I> is what determines the hypercorrect nature of PBs in our data and as such combines prolifically with other elements in first position of PBs. In our data we found only hypercorrect PB that did not contain I and only one with the conjunction or. No item contained a hypercorrect pronoun in the first position exclusively (cf. “Hypercorrect Forms by Syntactic/Grammatical Structure”).

-

v.

A brief analysis of individual characters found that only two used hypercorrect forms exclusively and one more near-exclusively; the others alternated between hypercorrect and non-hypercorrect forms, often following the same preposition (about, between, for, of, with).

-

vi.

Our data does not allow us to make strong claims about whether hypercorrect uses would be significantly more frequent in UK series than in US samples in general.Footnote 37 If we compare contemporary series in our corpus only, the occurrence rate of hypercorrect PBs are virtually identical in UK and US series (6% hypercorrect forms out of those places where they could have occurred). However, we did find that hypercorrect uses are significantly more frequent in specific TC genres (e.g., historical drama) than others, i.e., they are more saliently associated with archaic frames.

-

vii.

In our dataset, we found no instance that would suggest that the saliency of using hypercorrect pronoun case forms in binomials might have an enhancing effect on hypercorrect use of single subject case-marked pronouns following prepositions. The only case we did find in the entire corpus is a deliberate grammatical error: ‘The lessons you give I […] are precious to I’ (cf. GoT, S4E8) is put into the mouth of Grey Worm, a learner of the Westerosi Common Tongue (rendered in the series as English), who is choosing the first person singular subject-case form by mistake or possibly due to interference from his L1 (cf. GoT, S4E8).

The present paper has sought to share our corpus-pragmatic approach to occurrences of hypercorrect pronoun binomials in relation to grammatically correct forms. By dedicating significant space to the methodological levels, we have sought to make transparent the many corpus-methodological challenges entailed in systematically identifying relevant occurrences of pronoun binomials in mid-sized corpora. While we would encourage colleagues to imitate and refine our search paradigms for use in other and potentially larger corpora, we also need to stress that our study has not been able to cover all issues of interest in the matter. For instance, while we have limited this study to correct vs. hypercorrect use of diads coordinated by and containing me/myself and I in object position, future research might wish to expand on foci on, e.g., the use of object case (‘me’ only / me, her, him, us, them) vs. subject case (‘I’ only / I, he, she, we, they) in subject position or whether and to what extent there might be (non-)correlations between hypercorrect uses of I in object position and me in subject position.

Notes

For professional transparency we provide an electronic folder containing supplementary files via: https://1drv.ms/u/s!AgY8EFuwgCExkLda8wTxuLtTRArIVw?e=gH014Q. Tables in that folder are subsequently numbered and cited as S1, S2 etc.

This is, as Quirk and colleagues elaborate, due to the fact that, ‘in informal English, […] the objective pronoun is the unmarked case form, used in the absence of positive reasons for using the subjective form. It is this which accounts for the use of me, him, them etc. in subject complement function in conversational contexts’ (1985, Sect. 6.5; our italics). See Upton and Widdowson (2006: 75) on the diatopical distribution of [there are just] we two versus us two.

On than-comparatives also see, e.g., He and Wen (2015).

The best-known example of a prescriptive rule determining the order of elements or pronouns in such formulae is what is commonly called the modesty rule. It refers to the injunction against naming oneself first in a diad (e.g., ‘John and me’ being considered better than ‘me and John’; see Krejčová, 2011; Wales, 1996: 103).

Inversely, speakers might then also believe that Suzan and me is always prescriptively incorrect (cf. Silverstein, 1986/1995: 532).

She/he and myself did not occur in their dataset.

Transcripts were found using internet search engines. Texts were copy-pasted from websites including the BBC writers’ room, transcripts.foreverdreaming.org, www.springfieldspringfield.co.uk, and various blogs and fandom pages between January and September of 2019. Spot checks for accuracy (comparing the transcribed text with the original broadcast) were conducted before transcripts were included in the corpus.

Cf. Table S1 in our supplementary materials folder.

All this was in addition to the fact that that we had to make many manual corrections to the search hits, manually eliminate countless doubles and also exclude non-dialogue hits (see “Paring Down the Hits”).

Boyland’s study (2001) on hypercorrect pronoun cases in English was probably the first synchronic one to deal with competing patterns in which <X and I> and <X and me> occur. However, her dataset (written data sampled from usenet newsgroups) was relatively small and contained only 9 cases of nominative use in coordinate noun phrases.

We generated this set of types on the basis of a pilot study employing a dummy corpus. Note that Types 3 and 6 were not included in the analysis and therefore did not form part of the final dataset.

For this, we initially used manuals and tutorials provided on the website. At later stages, we also contacted the Sketch Engine helpdesk for assistance when problems arose with specific queries. We are very grateful to the helpdesk team, in particular to Vlasta Ohlídalová, for their prompt and generous help.

This ‘dummy’ test corpus was expanded and revised in numerous iterations and finally contained some 630 dummy sentences. This allowed us to ‘test-drive’ and refine the different CQL queries in order to make sure our searches would not miss any relevant items they were supposed to be targeting, but at the same time would exclude irrelevant items as far as possible. What proved particularly challenging here were the PoS (parts of speech) tags that Sketch Engine automatically assigned to our corpus (the ‘English TreeTagger PoS tagset with Sketch Engine modifications’ can be found here: https://www.sketchengine.eu/english-treetagger-pipeline-2/). Only extensive trialing revealed which words a particular PoS tag would catch and which words it would miss (see CQL in Queries 1–6). For instance, the tag PP (personal pronouns) would not catch reflexive pronouns ending in -self/selves or unusual pronouns like ye/y’all/thou/thee. None of the PoS tags would catch standalone possessive pronouns (mine, theirs). These therefore had to be added to the queries manually.

We decided to enter them into the CQL query phrase manually rather than using a PoS (parts of speech) tag after finding that the PoS tag for ‘preposition, subordinating conjunction’ (IN) in Sketch Engine did not recognize certain prepositions (apart from, including, next to).

Queries starting with this building block only targeted items where the pronoun binomial immediately followed the verb; constructions with verbs that demand a preposition (e.g., come between, go with) fell under the category ‘preposition’ (cf. Query 1).

Not only did searches for Types 3 and 6 produce tens of thousands of hits (including many doubles), they also did not find the structures we were targeting, namely PBs containing at least one personal pronoun.

Since Q5 targeted noun phrases up to 7 words in length, it could produce up to 7 quasi-identical hits for the same item in the corpus.

Tags included, e.g., E1: ‘verb’, ‘preposition’; E2/4: ‘personal pronoun’, ‘personal pronoun with -self/-selves’, ‘noun phrase’, ‘noun phrase: proper noun/name’, ‘noun phrase: with possessive (pronoun)’, etc.

Also cf. Table S2 on word group tags in our supplementary materials folder.

We are aware that (18) and (19) may be distinguished based on she and I in (19) functioning as the subject of the non-finite clause, whereas in (18) he and I is the object of the preposition between and thus a more salient case of a hypercorrect PB. However, following the general rule that non-finite clauses, by definition, do not feature a finite verb and thus no ruling subject, we include cases like (19) into our set of hypercorrect PBs in this study.

In addition, we excluded all hits with more than two elements.

Certain types of formulae that matched these criteria were nonetheless also excluded from analysis, if the insertion of the hypercorrect type <X and I> did not sound natural or plausible; these included formulae consisting of three or more elements, formulae containing a repeated preposition or an additional word, and, finally, formulae containing a long noun phrase in E4 that would have made putting me after the conjunction cumbersome, and thus made the use of the hypercorrect <X and I> sound unnatural.

In the one exception that contained a non-human NP, this element referred to a personified concept: If you will ride with me, I will consider fortune and I even. (Heroes, S2E2)

Cf. Table S3 for the overall distribution of prepositions with the percentage of hits per PB category for each.

No verbs in our data stood out as being especially likely to trigger a hypercorrect PB.

8 of the 13 were introduced by the preposition for.

Cf. ‘places where <X and I> are plausible (977)’ in Table S5.

We leave John from Cincinnati aside here, as we hesitate to draw conclusions from a series with fewer than 5 places where the target PB could have occurred.

Again cf. Table S5 in the supplementary materials.

It should be noted that the actors in Reign speak with UK accents, although it is actually a US/Canadian production. The majority of screenwriters, episode directors, and a fair portion of the principal cast members are US-American and Canadian.

Cf. Versailles, The Crown, Downton Abbey, Deadwood, Outlander, Game of Thrones and Taboo; cf. Table S4.

Cf. Bates Motel, The Blacklist, Ozark, Sherlock, Sex and the City, Heroes, Prison Break, Friends; cf. Table S5.

Note that we did not examine subject positions in this study, but focused solely on PBs in object position following a verb or preposition.

Also cf. me and them (3 hits), he and I, me and himself, she and I, them and me (1 hit each).

Here, the most frequent patterns were me and [name] (296 hits), me and [poss. + person] (116 hits), [name] and me (108 hits), [name] and I (35 hits), [poss. + person] and me (33 hits), [name] and myself (11 hits), [poss + person] and I (10 hits), myself and [name] (6 hits), [poss + person] and myself (2 hits), myself + [poss. + person] (1 hit).

The corpus is not balanced and representative in this regard: All the historical series in our corpus are UK English, with the exception of Deadwood (US English) and Reign, which is a US/Canadian production but in which characters speak UK English.

References

Angermeyer, P. S., & Singler, J. V. (2003). The case for politeness: Pronoun variation in co-ordinate NPs in object position in English. Language Variation and Change, 15(02), 171–209. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954394503152027

Batko, A., & Rosenheim, E. (2004). When Bad Grammar Happens to Good People: How to Avoid Common Errors in English. Franklin Lakes: Red Wheel Weiser. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/gbv/detail.action?docID=5531094

Bednarek, M. (2018). Language and television series: A linguistic approach to TV dialogue. The Cambridge applied linguistics series. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108559553

Bednarek, M. (2020). The Sydney Corpus of television dialogue: Designing and building a corpus of dialogue from US TV series. Corpora, 15(1), 107–119. https://doi.org/10.3366/cor.2020.0187

Biber, D., Johansson, S., Leech, G., Conrad, S., & Finegan, E. (1999). Longman grammar of spoken and written English. Harlow: Pearson Longman.

Boyland, J. T. (2001). Hypercorrect pronoun case in English? Cognitive processes that account for pronoun usage. In J. Bybee, & P. Hopper (Eds.), Typological Studies in Language: Vol. 45. Frequency and the emergence of linguistic structure (45 vol., p. 383). Amsterdam: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/tsl.45.19boy

Cochrane, J. (2003). Between you and I: A little book of bad English. Cambridge: Icon.

Collins, P. (2021). Hypercorrection in English: An intervarietal corpus-based study. English Language and Linguistics, 26(2), 279–305.

Crystal, D. (1988). The English Language. London: Penguin.

Cummings, L. (2018). Working with English grammar: An introduction. New York NY: Cambridge University Press: Cambridge United Kingdom.

Hatzidaki, O. (1999). Part and Parcel: A Linguistic Analysis of Binomials and its Application to the Internal Characterization of Corpora [unpublished PhD thesis]. University of Birmingham.

He, Q., & Wen, B. (2015). Reflections on the grammatical category of the than element in English comparative constructions: A corpus-based systemic functional approach. Ampersand, 2, 101–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amper.2015.08.001

Honey, J. (1995). A new rule for the Queen and I? English Today, 11(4), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1017/S026607840000852X

Jespersen, O. (1949). A modern english grammar on historical principles: Part 7. Copenhagen: E. Munksgaard.

Kopaczyk, J., & Sauer, H. (2017). Defining and exploring binomials. In J. Kopaczyk, & H. Sauer (Eds.), Binomials in the history of English: Fixed and flexible (pp. 1–24). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Krejčová, E. (2009). It is for you and I. Variation in the Pronominal System in American English. In J. Tárnyiková, & M. Janebová (Eds.), Anglica: Vol. 3. Acta Universitatis Palackianae Olomucensis: Anglica III Linguistica (1st ed., pp. 25–37). Olomouc: Univerzita Palackého.

Krejčová, E. (2011). “That’s an interesting question, indeed, not only for you and I”: A (Non-Systematic) fluctuation of personal pronoun forms. Brno Studies in English, 37(1), 63–78. https://doi.org/10.5817/BSE2011-1-4

Krejčová, E. (2012). ‘Default Case in Coordinate Constructions’ in R. Trušník, K. Nemčoková, and G. J. Bell (eds.) Zlín Proceedings in Humanities: Vol. 3. Theories and Practices: Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Anglophone Studies, pp. 65–77. Zlín: Univerzita Tomáše Bati ve Zlíně.

Labov, W. (1964). Stages in the Acquisition of Standard English. In R. W. Shuy (Ed.), Social Dialects and Language Learning (pp. 77–104). Ill.: National Council of Teachers of English: Champaign.

Norris, M. (2016). Between you & me: Confessions of a Comma Queen (Di 1 ban). New York: W.W. Norton and Company.

Parker, F., Riley, K., & Meyer, C. (1988). Case Assignment and the Ordering of Constituents in Coordinate Constructions. American Speech, 63(3), 214–233. https://doi.org/10.2307/454819

Quinn, H. (2005). The distribution of pronoun case forms in English. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Quirk, R., Greenbaum, S., Leech, G., & Svartvik, J. (1985). A comprehensive grammar of the English language. London: Pearson Longman.

Silverstein, M. ([1986] 1995). ‘Language and the culture of gender: At the intersection of structure, usage, and ideology’ (Originally published in E. Mertz and R. Parmentier (eds.) Semiotic mediation. Orlando: Academic. pp. 220–259.) In B. G. Blount (Ed.), Language, culture, and society: A book of readings, 2nd ed. (pp. 513–550). Prospect Heights, Ill: Waveland Press.

Sketch Engine (2003–). Available online at https://www.sketchengine.eu/

Sobin, N. (1994). An acceptable ungrammatical construction. In S. D. Lima, R. Corrigan, & G. K. Iverson (Eds.), Studies in language companion series: Vol. 26. The reality of linguistic rules (pp. 51–65). Amsterdam: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/slcs.26.07sob

Sobin, N. (1997). Agreement, default rules, and grammatical viruses. Linguistic Inquiry, 28(2), 318–343.

Sobin, N. (2009). Prestige Case Forms and comp-trace Effect. Syntax, 12(1), 32–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9612.2008.01113.x

Upton, C., & Widdowson, J. D. A. (2006). An atlas of English dialects, 2nd ed. London: Routledge. Retrieved from http://www.loc.gov/catdir/enhancements/fy0654/2005020803-d.html

Wales, K. (1996). Personal Pronouns in Present-day English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Innsbruck and Medical University of Innsbruck.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kirner-Ludwig, M., Oberhofer, K. & Heiss, J. Between You and I: A Methodological, Mixed-method Corpus-pragmatic Approach to Hypercorrect Uses of Subject Pronouns in Object Position. Corpus Pragmatics 7, 377–399 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41701-023-00152-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41701-023-00152-z