Abstract

Working from the perspective of Leech’s (The Pragmatics of Politeness. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2014) modification to Blum-Kulka et al.’s (Cross-cultural pragmatics: Requests and apologies. Norwood, NJ, Ablex, 1989) approach to classifying requests, this study investigates how far impositive directive speech acts are found in spoken Irish English, a variety of English which is well-known for avoiding face threats. The study further investigates how these impositive speech acts are influenced by the genre of the spoken category. In order to do so, this study uses data from the southern component of SPICE-Ireland, a pragmatically annotated corpus of spoken Irish English, and analyses data from six different genres of spoken conversation: Broadcast discussions, Business transactions, Classroom discussions, Face-to-face conversations, Legal presentations and Telephone conversations. These genres are classified in terms of the concepts of ‘language of distance’ versus ‘language of immediacy’. In the data, impositive strategies are frequently found, particularly so in private settings of ‘language of immediacy’. In the more public and formal settings of ‘language of distance’, by contrast, indirect strategies are more prominent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In comparative research on the pragmatics of Irish English, it has been found that speakers of Irish English are especially careful not to threaten their interlocutors’ face (e.g. Barron, 2008; Kallen, 2005). If face-threatening acts are avoided whenever possible in Irish English, we would assume that we would rarely find impositive directives, directives which create pressure to perform a certain action and by this threaten the addressee’s self-esteem. Not all directives are equally impositive, of course, and different kinds of directives with different levels of impositiveness have been observed (Blum-Kulka et al., 1989; Leech, 2014). For Irish English, we would then expect that in order to preserve the interlocutors’ face needs, few highly impositive directives should be used in this variety. To test this assumption, an investigation is carried out of select data from different spoken genres of the pragmatically annotated SPICE-Ireland Corpus (Kallen & Kirk, 2012).

The study hypothesizes that the amount of impositive directives will vary according to the speech situation. It assumes that in informal situations, if speakers know each other well, they are more likely to pay much less attention to overt politeness in their interaction with their interlocutors than in less personal, more formal contexts. In order to investigate this assumption, spoken genres of different degrees of formality are selected from SPICE-Ireland. The assessment of how formal a genre is has been informed by the classifications of language of immediacy and language of distance by Koch and Oesterreicher (1985/2012). This model combines the investigation of language choices in the context of oral versus written medium, with the context of typical written or spoken delivery to create a framework of classifying distance and immediacy. The current study investigates whether the formality of the textual genres coincides with the number and types of directives in the SPICE-Ireland data sets. If so, we would expect a correlation between the presence of impositive strategies with personal, informal situations, and fewer and less impositive strategies in formal situations.

On the basis of these hypotheses, the current study aims to demonstrate first, in how far impositive directive speech acts are found in spoken Irish English corpus data. Second it asks whether these findings can be shown to correlate with the level of formality of the text.

In order to answer the research questions, directive speech acts have been extracted semi-automatically from six spoken categories of SPICE-Ireland (Kallen & Kirk, 2012), namely Broadcast discussions, Business transactions, Classroom discussions, Face-to-face conversations, Legal presentations and Telephone conversations. The data have then been analysed manually. The directives have been subclassified according to the annotation scheme by Leech (2014), itself based on Blum-Kulka et al. (1989), in order to determine the degree of directness in the investigated SPICE-Ireland directives. Questions are considered within the directive paradigm, yet in line with the models used, the focus in this contribution is put on declarative structures. The mixed methods approach used in this study constitutes an improvement over earlier exclusive form-function approaches to corpus searches (e.g. Kohnen, 2002) in that it allows us to observe both the qualitative and quantitative distribution of speech acts. In this case it also enables us to correlate the use of these linguistic features with further, non-linguistic features to – automatically – learn more about differences in spoken genres. As a restricted data set has been investigated so far, this research remains exploratory and will require further extension in the future.

The description of these issues in the paper is structured as follows: after this introduction, the different types of directive speech acts are discussed, then data and methodology are introduced. Next, the results are presented and discussed against the background of what is known about directive speech acts before conclusions are offered.

Theoretical Background

The Classification of Directives

According to Searle (1976), directive speech acts are used by speakers to try and encourage an addressee to carry out an action (Searle, 1976: 11). By request, we mean a verbal action, either a command or a request (e.g. Blum-Kulka et al., 1989), whose illocutionary point is to get someone to do something. In order to make an order or a command, the speaker needs to be in a position of power over the addressee. However, a request may not be acted upon (cf. discussion in Leech, 2014: 134–136). Directives can take various forms: frequently, directive speech acts consist of imperatives, or mood derivables, such as shut the door. Other common types are interrogatives, would you shut the door, or declaratives, I hate that open door (Sinclair & Coulthard, 1974: 28). Directive functions are also fulfilled by the speaker-implicating let- constructions or insubordinated if-structures, for example let’s shut the door, or if you could shut the door? (Mato-Míguez, 2016; Moessner, 2010).

These different kinds of directives vary in the degree of imposition which the utterances express: some structures are more, others are less impositive. The degree of impositiveness of directive speech acts has been studied by various researchers (Blum-Kulka et al., 1989; Ervin-Tripp, 1976; Kohnen, 2002, 2008; Leech, 2014; Moessner, 2010). In these approaches, different, but largely related classifications have been suggested for the degree of imposition constituted by individual types of directives.

Blum-Kulka et al. (1989), in their influential approach, subdivide directives into broad categories of impositive strategies, and also of conventionally and non-conventionally indirect strategies. Developing the model of Blum-Kulka et al. further, Leech (2014) addresses issues raised in relation to the earlier model and provides an adapted version, which forms the basis of the current investigation, albeit with some slight modifications suggested by the characteristics of the data in hand.

According to Leech (2014), directive strategies can belong to the following types.

Direct Strategies

Direct strategies are those that do not use any devices to reduce face threats. These can be imperatives (example 1) or performatives (example 2).

-

1.

Clean up that mess.

-

2.

I am asking you to clean up the mess.

The specific performative verb that is used has a strong impact on the impositiveness of the utterance. Demand is more impositive than ask or even entreat (Leech, 2014: 148). Leech further points out that, while the progressive form of the verb may be included in the performative as in example 2, performatives softened by hedges form a separate category. By contrast, Blum-Kulka et al. (1989) include hedged performatives such as I would like to ask you to give your presentation a week earlier than scheduled amongst the impositive strategies.

On-Record Indirect Strategies: Statements

Less face-threatening than the impositive strategies above are indirect directive strategies. In contrast to the impositive strategies, indirect strategies are less likely to lead to the loss of face if a request is not fulfilled. In on-record indirect statements, the addressee needs to derive the directive force by using a number of inferential steps. Often, modal auxiliaries are used from which the illocutionary force is inferred (Leech, 2014: 148–149). The impositiveness of these strategies decreases from prediction statements (example 3) to strong and weaker obligation statements (4 and 5) to volitional and ability/possibility statements (examples 6 and 7; all examples from Leech, ibid.),

-

3.

You will just fill out that work ticket. It’ll be your responsibility to fill it out correctly […].

-

4.

You must record testing times for all three tests.

-

5.

Weaker obligation statement, e.g. You should give me all your old clothes Lisa.

-

6.

I want you to bend your knees. [at a skating lesson]

-

7.

You can hang out with my mom for a while [Longman Corpus of Spoken American English (LCSAE) 135401]

A further directive strategy, the use of let’s, is included by Leech (2014) amongst his examples of vocatives (2014: 172), which he groups within the more indirect end of directives.

-

8.

Let’s go home in your car. [Leech, 2014: 138]

Leech raises the possibility of such “semi-formulae” lowering the level of imposition, but, without discussing the matter, thinks it probable that they do not (Leech, 2014: 138, fn.).

Other authors see this structure as adhortative, used with the intention of doing something together (Moessner, 2010), or as an assertive directive, using the first person plural pronoun to mitigate the face-threat (Collins, 2004; Mato-Míguez, 2016).

On-Record Indirect Strategies: Questions

Like statements, questions can also be used to make interlocutors carry out an action. In the indirect question strategies, the hearers’ volition or ability to carry out the action is asked for. In contrast to indirect statements, however, the interlocutors’ consent is queried and thus the interlocutor is approached with greater indirectness than in an indirect strategy statement (Leech, 2014: 152). However, Leech also adds that while a statement could be ignored by the interlocutor, a question expects an answer, and depending on the social position of the interactants, a positive reply may be necessary.

Different levels of directness can also be observed for questions. Questions about volition with will are most direct, would encodes unreal events and thus offers a more indirect form of questioning volition (Leech, 2014: 150; examples 9 and 10).

-

9.

Will you bring a spoon when you bring my pudding? [BNC KBL, Leech, 2014: 153]

-

10.

Would you explain to us what subject you have chosen? [BNC J40; Leech, 2014: 153]

Leech notes that will is mainly used in familiar discourse, where the cost of the action for the interlocutor is relatively low.

In addition to enquiring about the interlocutors’ willingness to carry out an action, the speaker may also ask for their ability or possibility. Leech (2014: 154) notes that this is more indirect than asking for volition, as it is asking for a preparatory condition, ability, rather than for the willingness to carry out the action as in

-

11.

Could you tell me the answer?

-

12.

Is it possible, Larry, to send me a copy of that? [LCSAE 14101, Leech, 2014: 155]

Leech (2014: 154-155) regards ability questions with can/could as more indirect than those with will/would, but also points out that the differences between would and can are difficult to capture.

Nonsentential Strategies

Nonsentential strategies do not use full sentences to make a request. Leech (2014: 156) gives examples like another cup, please; Next?; or a return to Glasgow, please. Leech points out that nonsentential requests are often routinized and do not contain indirectness devices and may thus seem rude. Yet the meaning needs to be inferred by the addressee, and in public service encounters, where these are often found, please or honorifics are often added. Further, Leech (2014: 157) includes in this category replies to offers, such as example (13) or suggestion formulae like how about…? as in example (14), and also adverbial if clauses (cf. Mato-Míguez, 2016), example (15)

-

13.

Would you like Parmesan cheese? Yes, please, thanks [LCSAE 128701, Leech, 2014: 157]

-

14.

If you’re doing nothing, how about giving me a hand? [BNC FNW, Leech, 2014: 157]

-

15.

(…), if the other person could say nothing at all, and then if you could both change over (…) (Leech, 2014: 157, citing from Hill 2007: 188)

Leech (2014) situates nonsentential strategies between the indirect question strategies and hints. Formally, all the above strategies indeed have in common that they do not consist of complete sentences. However, not all the above examples appear to have the same degree of imposition. An immigration official’s on-record request for Passport? seems more impositive than the adverbial if- clause or the how about … ? clause, which are indirect requests for preparatory conditions. In the SPICE-Ireland data investigated here, the prosodic annotation helps to disambiguate the level of imposition in some cases.

Hints

In addition to on-record indirect strategies, we further find directives that constitute off-record indirect strategies. These do not mention the action that is intended by the speaker, instead, it is left to the hearer to infer what is meant (Blum-Kulka et al., 1989; Leech, 2014). Leech (2014: 158–159) subdivides hints into statement hints and question hints.

Statement Hints

Hints can be made as statements which are more or less indirect. Blum-Kulka et al. (1989) distinguish between strong hints, which can be easily decoded, such as you have left the kitchen in a right mess and mild hints, in which the hearers need to infer the meaning, as for Blum-Kulka et al.’s example I am a nun, given in response to a persistent hassler. Leech (2014: 158), too, identifies different degrees of indirectness in hints, but does not subdivide the category into stronger and milder items. Instead, he points out that statement hints in general are not very polite and as a consequence often use further politeness markers like apologies.

Question Hints

Question hints are used to find out whether the preconditions for satisfying a request exist. In answering the question hint, the addressee can negate the precondition, or they can react to the implicit request and help the speaker to fulfil their needs as in examples (16) and (17).

-

16.

Are you going to the train station? (Leech, 2014: 159)

-

17.

Do you have his telephone number (BNC JT5; Leech, 2014: 159)

If they fulfil the preconditions, the addressees may offer the speakers a lift to the train station or, in a dialogue, provide the answer.

Pragmatic Modifiers

The categories mentioned above can be modified by a variety of pragmatic markers. These may mitigate the directive force of a request, typically by increasing the optionality of the request (Blum-Kulka et al., 1989; Leech, 2014). The modifiers can either be internal, and thus be included in the same utterance as the head act, or external to it. In addition, we find modification by supporting moves. In particular, these internal and external modifiers are supporting moves that can elaborate the requests (Leech, 2014: 160).

A number of items can function as internal modifiers. These can be downtoners (perhaps, maybe, possibly), politeness markers (please), deliberate, appreciative or hedged performative openings (I wonder, do you think; I’d be grateful, I’d appreciate if; or may I ask, I must insist respectively), negative bias (I don’t mind, I wouldn’t mind), happenstance indicators (Do you happen to...?, by any chance), temporal availability queries (do you have the time to…?), past tense use with hypothetical (would, could, might) or past time reference (I wondered, I wanted to…), progressive aspect (I was wondering, I was wanting) or tag questions (will you? Could you? Okay?) (Leech, 2014: 160–171).

External modifiers can be found before or after the head act of the directive utterance. External modification can take place with apologies (Excuse me, sorry), anticipatory expression of gratitude for fulfilling the request (Can you do the next one James please, thank you [BNC F7L] Leech, 2014: 172), or vocatives. While vocatives can single out hearers, they can also serve to establish social relationships. In addition to personal names used to signal a personal relationship, honorifics (Madam, Sir) show respect, terms of endearment show closeness (love, darling).

In the data analysis in the current study, mitigating effects of such modifiers are taken into account by the creation of less impositive subcategories such as Modified Performatives in addition to Performatives or Modified Direct Questions in addition to Direct Questions.

Direct Questions

In addition to the indirect question strategies and question hints mentioned above, questions may also serve to direct the hearers to carry out an action (Kallen & Kirk, 2012: 30). The current study adds the category of direct question to the schemas introduced by Blum-Kulka et al. (1989) and Leech (2014) in order to classify direct questions types which are marked as directives in the study’s data source, SPICE-Ireland (Kallen & Kirk, 2012). As Blum-Kulka et al.’s (1989) and Leech’s (2014) framework are followed in this study, a more in-depth analysis of questions must, however, be postponed.

In contrast to the indirect question strategies, the direct questions do not ask for a preparatory condition for carrying out the action, such as volition or ability. As in the other directives discussed above, questions can likewise vary in their directness and be personal and direct, either unmodified (18) or modified (19), they can be direct but not addressed to a single person (20 and, in a modified version, 21), or they may be rhetorical and not expect an answer at all (22).

-

18.

Are you coming tonight?

-

19.

Can I ask you if you are also coming tonight?

-

20.

Is anyone coming tonight?

-

21.

Can I ask if anyone is coming tonight?

-

22.

Do pigs fly?

We can observe in the above types of directives that they are increasingly less impositive and increasingly less threatening to the addressees’ face. The last category of questions, rhetorical questions, is least impositive as the hearer is not really required to act on them.

Imposition in Irish English

We know from previous studies of Irish English that in comparison with other varieties of English, Irish English tends to be less direct and it marks politeness extensively. Thus, in comparison with both English English and American English, hedging devices, especially I would/’d say, are used more frequently in Irish English than in the other two varieties in order to soften face-threatening acts (Farr & O’Keeffe, 2002). It is also found that, in contrast to American English, Irish English uses more and more varied thank minimisers (Schneider, 2005). Further, in comparison to English English, Irish English speakers take greater care to decrease face threats in the context of offers and of requests (Barron, 2005, 2008). Kallen (2005), discussing politeness strategies in Irish English, observes that the speakers of this variety generally avoid being overly assertive and direct. Their politeness strategies typically emphasize group identity and conventional optimism. As a consequence, even in asymmetrical power relations, such as in teacher-student meetings, strategies of minimizing inherent power differentials are frequent (Farr, 2005).

Given Farr and O’Keeffe’s (2002) finding that the hedging devices I would or I’d say are frequent in Irish English, it is not surprising that comparable structures are also identified in the corpus materials in hand. As a result, we find modified, hedged obligation statements, especially with the structure you would have to, as well as the hedged volitional statements, such as you would want to. As they are both indirect and hedged, the categories of modified obligation (23) and want statements (24) were added to the classification:

-

23.

You would have to have it in by Monday.

-

24.

You would want to be there early.

Given these findings, we would expect that in line with previous research, Irish English would be likely to avoid face threats in directives and replace impositive strategies by indirect strategies whenever possible. However, other research also specifies that face threats and impoliteness can appear in Irish English, especially in swearing as documented e.g. in Murphy (2009), Ronan (2014) or Schweinberger (2018). In the following, we will test the hypothesis that impositive strategies are dispreferred in (spoken) Irish English, using the pragmatically annotated SPICE-Ireland Corpus (Kallen & Kirk, 2012), described in Sect. "Data and Method" below. Before turning to the data and method used, we briefly compare the types of discourse analyzed here.

Determining the Effect of Genre

For the classification of genre differences in English, the corpus linguistic approach by Biber (1988) is central. However, for the conceptualisation of how close interactants are and how private or public the setting is in which the communication takes place, a model developed by Koch and Oesterreicher (1985/2012) can profitably be applied. Koch and Oesterreicher (1985/2012) consider not only the basic difference between spoken and written language, and the mode of communication, namely phonic, oral and aural, or graphic, written, mode, but also features of (conceptual) distance between the language users. This model is chosen here as it allows us to take into account whether an utterance is made in written or spoken form and additionally, whether it has originally been written down to then be spoken, whether it is spoken without being written down, whether it is written from spoken language or purely written. Koch and Oesterreicher (1985/2012) work on the premise that different spoken genres show a cline from prototypical spoken features towards prototypical written features:

intimate conversations > telephone conversations with a friend > interviews > job-interviews > sermons > lectures

These prototypically spoken genres can also be represented in graphic form: at a level of formality between the interview and the job interview, Koch and Oesterreicher (1985/2012: 444) first place printed interviews, then diary entries, then private letters. Written genres more formal than a lecture are articles in quality newspapers and, most formally, administrative regulations. Koch and Oesterreicher (1985/2012: 445–446) further observe that various communicative parameters play a role in the conceptualization of that observed continuum. These parameters include social relationships between the participants, the number of participants, their location in time and space, the degree of exposure to the public, spontaneity and involvement and the context. Ultimately, no linear continuum from spoken to written language can be argued for, rather the influence of different variables leads to a multi-dimensional space that is situated between the poles of language of immediacy and language of distance. The conceptualizations that underlie Koch and Oesterreicher’s model are represented in Table 1.

As shown in Table 1, Koch and Oesterreicher assign typical characteristics to language of immediacy and language of distance. Written interaction between interactants who are close to each other typically is dialogic, as for example in a letter that refers back to previous communication, et cetera. Expressivity and affectiveness can also be features, even more so when the genre moves closer towards spoken levels. Written interaction between interactants who are distanced typically is monologous, as for example in a book or a law text. At the spoken level, the interaction between close interactants shows low levels of planning, lower information density et cetera. Spoken interaction between distanced interactants typically shows higher levels of planning, higher information density and so on.

With the help of this model, we can classify the spoken genres that are investigated in this study as situated on the continuum of language of immediacy and distance. This issue will be taken up again in the analysis in Sect. "Analysis".

Data and Method

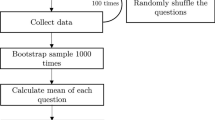

This study uses a corpus-driven approach which is based on the SPICE-Ireland Corpus (Kallen & Kirk, 2012). SPICE-Ireland belongs to the ICE family of corpora, the International Corpus of English (Nelson et al., 2002), compiled to facilitate comparison of different varieties of English. Each ICE corpus consists of one million words, in chunks of roughly 2,000 word texts each, stemming from different written and spoken genres. Spoken genres account for 60% of the content, and written ones for 40%, and the genre types are identical in the corpora of each variety. SPICE-Ireland represents the spoken subset of the Ireland component of the ICE corpus, ICE-Ireland (Kallen & Kirk, 2008), and has been pragmatically annotated and the data have been pre-coded and tagged for pragmatic and intonation features by the corpus editors. This tagged, computer-readable corpus thus allows us to compile an exhaustive, corpus-driven collection of specific pragmatic features by searching for any given pragmatic tag. In our given case, all speech acts marked as directives (<dir>) were searched for with AntConc (Anthony, 2018). This data-driven approach has the advantage that the full set of directives in the source data can be evaluated, and a more comprehensive overview of different structures in different types can be created than would be possible in a manual analysis.

For the current analysis, thirty files of spoken language have been selected that are representative of genres (Broadcast discussions, Business transactions, Classroom discussions, Face-to-face conversations, Legal presentations and Telephone conversations) with different levels of formality. In each case the first five files have been selected from the Southern Irish English components of the SPICE-Ireland (Table 2). Though SPICE-Ireland, like ICE-Ireland, consists of a northern component, representative of Northern Irish English, and a southern component, representative of Southern Irish English, for the current study only files from the southern component have been selected. This has been done as Northern and Southern Irish English are usually considered as two different varieties of Irish English, with Northern Irish English showing strong influence from Scots (Kallen & Kirk, 2008; Corrigan, 2010; but cf. Kallen & Kirk, 2007 for four hypotheses concerning possible relationships between the two geo-political zones). As no studies on potential pragmatic differences between speech acts in the two varieties exist to date, the restriction to one variety seemed prudent until differences or identity of the pragmatic systems can be confirmed. This would clearly be a research desiderate.

In the thirty files specified in Table 2, totalling about 60,000 words, 1,085 directives were found. After extraction, these directives were classified manually into the different strategies according to Leech (2014) namely into direct strategies, on-record indirect strategies, statements and questions, nonsentential strategies and hints. Further direct questions were divided into questions as direct or modified personal questions, non-personal or indirect questions, and rhetorical questions, as well as the modified obligation and want statements including you would have to, and you would want to-types also observed to be frequent in Farr and O’Keeffe (2002).

The different types of directives found in the corpus data were then quantified and compared within the different genre categories. A small number of directives could not be assigned clearly to Leech’s categories. However, this number remains small at 3.3% of the examples.

The results of this analysis are presented in the following.

Analysis

Attestations of Directives

In the thirty SPICE-Ireland files investigated, 1,085 directives were found. They were assigned to Leech’s (2014) categories of direct strategies, on-record indirect strategies (statements and questions), nonsentential strategies and hints, as well as to the category of direct questions (Kallen & Kirk, 2012). The focus of this study will be on those strategies whose impositiveness can be graded clearly (Strategies 1 – 5 in Fig. 1.). An overview of the different strategies found in the corpus is given in Fig. 1.

Apart from questions, which are not the main focus of this study, Leech’s (2014) direct strategies are most frequent in the data set (116 examples, 10.7% of all directives), followed closely by hints (108 examples, 10% of all directives), by on-record indirect statements (84 examples, 7.7% of all directives), and on-record questions (26 examples, 2.4%), and nonsentential structures (24 examples, 2.2% of all directives). The type of directive according to Leech’s categories could not be clearly determined in 3.3% of the cases (36 examples). The largest number of examples (691, 63.7%), consist of further question strategies (i.e. direct or modified personal questions, non-personal or indirect questions, and rhetorical questions).

Direct strategies

A large number of the directives in the corpus material, 116 (10.7%) of 1,085 examples, is accounted for by direct strategies (see Fig. 1). Of these, imperatives are the more numerous category (examples 25, 26). Performatives (example 27), which are less impositive than imperatives, are rare in the corpus, accounting for two examples only.

-

25.

<#><P1A-050$A>The fourth of July right* yeah@* </rep> <#> <dir> Come on </dir> <#> <dir> Send up another one til[l] I look </dir>

-

26.

<P1A-050$C> <rep> For God 's sake 'twas gone an hour ago </rep> <#>

-

<$B> <dir> Shut up </dir> <#> <rep> It was not </rep> <#>

-

27.

</dir><P2A-067>1I believe you will be 1compElled to 1fInd% <,> and I 5requIre you% to 1sO find% <,> that there was 1nO 1fActual basis% to 1jUstify the 1chAnge in Mr 1REynolds '% 1assEssment of my 1cOnduct% or 1sUItability for 1Office% <,>

While examples 25 and 26 stem from private conversations between friends, example 27 comes from legal presentations in front of a parliamentary committee. Example 27 thus stems from a context which, according to Koch and Oesterreicher’s (1985/2012) categories, is very different from private conversations between friends (see Table 1): the occasion is public, the participants are not (all) familiar, and the language at the legal hearing is not spontaneous or, in the business conversation, not expressive. In contrast to Koch and Oesterreicher’s ‘prototypical’ spoken interaction represented by examples 25 and 26, in example 27, we are dealing with a category of spoken interaction that is very high or high on the scale of the language of distance. Generally, we find that direct strategies are notably more frequent in face-to-face conversations than in the other genres (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of directive strategies according to Leech (2014) in the investigated SPICE-Ireland genres. Direct strategies are notably more frequent in the most intimate interaction genres, personal communication and telephone conversations among friends (Koch & Oesterreicher, 1985/2012), than in the more distanced genres.

On-Record Indirect Strategies: Statements

Leech (2014) separates on-record indirect directive statements into prediction statements, strong and weaker obligation statements, volitional statements and ability statements. To this category, we may also add let’s clauses, which are not discussed as a separate entity by Leech (2014).

The most impositive category, prediction statements, are not found in the corpus. Frequent in the data are obligation statements, especially strong obligation statements (example 28).

-

28.

<P1A-048$A> <dir> Oh you 're going to have to live up to that </[> </dir> <dir> You 're going to have to live up to that </dir>

-

<$B><rep> I 'm fucked up yeah@* </rep>

Strong obligation statements account for 40 examples (47.6% of the 84 on-record indirect statements strategies). Example 28 stems from Face-to-face communication between close participants. While some examples stem from Classroom discussions (5 examples), and Face-to-face communication (6 examples), the largest number (n = 27) are found in Broadcast discussions, where the examples predominantly consist of nominations by the talk show hosts, as in example 29, where the talk show host nominates the next speaker from the audience.

-

29.

</dir><P1B-032$B><dir> Okay* <,> 1cEntre of the middle 1rOw% <exp> yeah* sorry </exp> 1bAck middle row 1cEntre% </dir> <#> <dir> 1YEAh%

-

<#><$G> <rep> I would 1lIke to 1sAy Mr Chairman%

Even though these structures are frequent in a non-private, language of distance genre, we can explain why these impositive structures are used so frequently here: the high-status talk-show host has given the floor to the next speaker. A certain status-inherent power differential is also found in a classroom discourse, though, where a teacher calls upon, i.e. nominates, a student (30) and asks them to take the floor. The example is marked as having a falling intonation in the end (%), which makes this a clear nomination.

-

30.

<P1B-011$A> <,> 1whAt are the implications for <&French> 1mOI </&French> <,,> </rep> <#> <dir> 1ROnan% </dir>

That there are only five instances in the 30,000 words of Classroom discussion shows that this power differential is not verbalized in class very often, an observation that is supported by Farr’s (2005) study.

Weak obligation statements are rare in the corpus (7 examples). In particular, they stem from contexts of committee hearings, business communication, telephone conversations and face-to-face communication in a larger group. Generally, these could be described as domains where a more distanced language is called for, such as in the following example from a Government accounts meeting (example 31).

-

31.

<P2A-066$B ><#> <dir> Uh I 1nOte 1Also uh Minister% that you 1accEpted a 1repOrt from 1IBEC 1yEsterday% uh 1dEAling with this same 1Issue% and 1mAybe you might 1Use this 1occAsion% to uh 1respOnd to their 1concErns% </dir>

A further type of on-record strategy, which is lower down the scale of imposition, is that of volitional-statements (Leech, 2014). In the data, we particularly find modified examples with the less impositive would like (cf. Leech, 2014: 150; example 32), and even more weakened verbs like hope (example 33).

-

32.

< P2A-069$A> <#> <dir> But that's one of the areas that I would like the Minister to you-know* to take a lead in getting a solution for </dir>

-

33.

<P2A-069$A><dir> I would hope Minister that that report will not be ignored <,> and that some action will be taken on the recommendations of that report <,> and that they will be taken very very quickly </dir> <#>

Both 32. and 33. stem from committee hearings. Examples are rare in the corpus, with the majority (6 of 8 examples overall) stemming from public and distanced genre of committee hearings, where keeping the interlocutor’s public face is particularly important (Barron, 2005, 2008).

Further, we find examples of ability and possibility statements. As Leech (2014: 151) points out, ability and possibility are closely related concepts which are often expressed by can or the more hypothetical equivalent could (examples 34 and 35), with the past tense modal being even less impositive (Leech, 2014: 150).

-

34.

<P1A-099$B> <#> <dir> You can borrow something belonging to me if you want to </dir> <#> <rep> I don't know if I have anything </rep>

-

<$A> <#> <dir> What uh what have you got </dir>

-

35.

<P1A-100$A> <#> <rep> Uhm 1nO%* you 're not on 1hOld% </rep>

-

<$B> <#> <dir> You could 1pUt me on hold% </dir>

-

<$A> <#> <rep> 5NO%* <,> I just 1yElled over my 1shOUlder at my 1dAd% </rep> <#

A further category to be added here is the let’s – structure, which presents a request as a suggestion and involves the speaker and the addressees (Leech, 2014: 138, fn.).

36. <P1B-011$A> <#> <dir> 8LEt 's 9jUst* 1sEE% </dir <dir> Let 's weigh 1Up all these 5possibIlities% </dir> <#> <dir> Let 's 1consIder the 2trEnds% </dir> <#> <dir> And let 's 1tAke it from 1thEre% </dir>

At 16 examples (19% of the 84 examples on-record statements), indirect structures are the second most frequent in the category. We find them in Classroom discussions (8 examples, 9.5% of the on-record statements) and Broadcast discussions (5 examples, 5.9%) in particular, but also in the Face-to-face and Legal communications. As in example 36, uttered by a lecturer, we can most typically find the let’s structures used where a speaker determines the course of the conversation and subsequent action. This finding ties in with Leech’s (2014: 138, fn.) observation that let’s often implies that the hearers’ interests are served even though in reality the speakers’ interests are pursued. An overview of the on-record strategies used in the different genres is given in Fig. 3.

In Fig. 3 we can see that of the on-record strategies, strong obligation statements are the most frequent, followed by let’s constructions. They are not evenly distributed, however. Obligation statements mainly exist in the nominations in Broadcast discussions, let’s constructions in Classroom and Broadcast discussions. In this category of on-record strategies in the SPICE-Ireland data, the largest number of impositive directives are used by speakers of high authority in the discourse situation: hosts of talk shows nominating speakers or lecturers organizing classroom discourse.

On-Record Indirect Strategies: Questions

Like on-record statements, on-record questions also show differing degrees of imposition. As Leech (2014: 152) points out, questions seem to leave the decision of how to react to an event to the hearer and thus imply greater politeness. However, as stated in 2. above, a question does expect an answer, particularly if the asker is in a powerful social position, and may in fact demand agreement. Typical of on-record indirect question strategies are queries about a preparatory condition, such as volition of the hearer or their ability to comply with the request. Overall, on-record questions have lower frequencies than direct strategies or on-record statements, accounting for 26 of the 1085 directives in the corpus (2.4% of the examples).

Requests for volition may use a present tense modal, will, or the past-tense modal, would. Additionally, modified varieties of such requests, such as would you want to… also exist (Leech, 2014: 154). In the current corpus, would you care to (examples 37, 38) is found thrice.

-

37.

<P1B-013$A> <#> < <dir> Take the eighty-one to eighty-nine period </dir> <#> <dir> Would somebody else comment on that now </dir> <#>

-

38.

<P1B-013$A> <dir> What about this business of uh regional dispersal </dir> <#> <dir> Would anybody care to comment on that <,> </dir> <#> <dir> Have the multinationals an impact in dispersing jobs to certain regions </dir> <#>

In the corpus, questions enquiring about the hearer’s volition (19 examples, 73% of all on-record questions) are more frequent than those enquiring about ability (7 examples, 27% of the on-record questions). Interestingly, more specific formulations than can (example 39) or could are also used to qualify the ability that is needed: asking for remembering or for information on the topic (examples 40 and 41).

-

39.

<P1B-013$A> <#> <dir> Can you use the data to <,> to you-know* be a bit more explicit than saying that multinationals you-know* dispersed more widely </dir>

-

40.

<P1B-013$A> <dir> I don't imagine you 'll remember all <,> all the figures but would you be able to remember any particular figures from the table </dir> <#>

-

41.

<P1B-014$A> <#> <dir> Would you have any information to support the view that uhm multinationals essentially employ uh those good employees whereas uhm the Irish firms would have you-know* middle management and top management would be Irish whereas with the multinationals it would be essentially foreigners who control the upper echelons </dir> <xpa> <unclear> 4 sylls </unclear> </xpa>

The majority of the on-record questions, 10 of 26 (38.5%) stem from Classroom discussions, where the instructors try to activate student knowledge, followed by Face-to-face and Business communications (4 examples each). Thus we can see that this somewhat less impositive strategy is used to a large extent in the semi-public and semi-distanced classroom setting. As Farr (2005) points out, highly impositive strategies, such as imperatives, are avoided here to avoid face threats to the students. In the more intimate genres, on-record questions are comparatively rare, and they are absent in the highly formalized legal genre of committee hearings.

Nonsentential Strategies

As indicated in “Theoretical Background” above, Leech’s (2014: 156–157) nonsentential strategies are a category that comprises different types of utterances. They are characterized by the formal criterion that they do not consist of full sentences. Thus Leech includes shortened requests by officials like Passport? or Tickets please, as well as semi-formulae such as how about...? or what about…?, or adverbial if-clauses (Mato-Míguez, 2016) here.

In the current corpus, such nonsentential strategies are also comparatively rare, accounting for 24 examples (2.2%). Like on-record questions, they are most frequent in Classroom discussions, where 13, 54.2% of the 24 examples, are found.

-

42.

<P1B-013$A> <#> <#> <dir> What about this business of uh regional dispersal </dir> <#>

-

43.

<P1B-015$A> <#> <dir> None at all </dir> <#> <dir> How about last week 's lectures <,,> </dir> <&> laughs </&> <#> <dir> Anybody <{> <[> </dir> <#> <dir> Uh </[> <,> so you all you all thought then that the religious stuff was okay <,> yeah@* </dir> <#> <dir> Julian of Norwich </dir>

A large percentage of the nonsentential strategies (11 of 24, 45.8%) are accounted for by what about and how about questions (examples 42 and 43). These are non-targeted questions which are comparatively low in their level of imposition and the fact that a large percentage stem from classroom discussions show us that they, too, are used by lecturers to elicit student responses. Example 43, which provides two nonsentential strategies, contains a second nonsentential strategy in the clause, Anybody, which explicitly encourages responses from any of the students present. Thus, in the current corpus the nonsentential strategies also are most frequent in semi-public, semi-distanced genres like Classroom discussions, followed by the rather formal category of Business transactions.

That nonsentential strategies are comparatively rare might be due to the fact that day-to-day interactional, routinized processes such as shop or restaurant interactions are not represented to a large extent in the ICE-Corpora, including the SPICE-Corpus.

Hints

Hints, subsumed under the label non-conventionally indirect strategies by Blum-Kulka et al. (1989) are the least impositive strategy in Leech’s (2014) model. Their messages need to be decoded by the recipients and as they are quite indirect they are also the most face-saving approach. As Irish English tends to avoid directness and face threats (Barron, 2005, 2008; Kallen, 2005), we would hypothesize that indirect strategies should generally be preferred to impositive ones. In the corpus materials hints are one of the more frequent strategies at 108 examples (10% of all directives). Statement hints are illustrated by examples 44 and 45.

-

44.

<P1B-032$D> <dir> So it's going to be allowed to go into opposition </dir> <#> <P1B-032$B> <rep> I I most certainly believe yes … .

-

45.

<P1A-050$C> <#> <exp> I wish it'd go <&> makes funny noise </&> </exp> <&> laughter <&> <#> <dir> I don't know what 's so funny </dir>

-

<$B> <rep> This house gets more like living in Rainman every day </rep>

Examples 44 and 45 show how the respondent is prompted by the hint to engage with the statement. With 100 examples, the category of statement hints constitutes the large majority (93%) of hints in the corpus. These hints may be ignored by the conversation partners and thus only constitute a low imposition.

Question hints are less frequent than statement hints, accounting for 8 of the 108 examples of hints in the corpus. A typical example is illustrated by (46)

-

46.

<P1A-050$B> <#> <rep> If you have six and a few shots of bourbon </rep>

-

<$C> <#> <dir> Okay* <,> has anybody got <{> <[> poiti/n </[> </dir>

-

<$B> <#> <rep> <[> In case </[> </{> anybody 's listening </rep> <&> laughter </&>

This example suggests that if somebody has poitín, illegally brewed whiskey, the speaker would like some of it to drink.

A further point is noteworthy here, namely the annotation of laughter in the data set. While classifying the data, high instances of laughter were noted in the data sets associated with language of proximity. Numbers of directives and laughter appear to show some correlation, which seem further influenced by text category. The discussion of this issue, however, is beyond the scope of the present paper and will be taken up elsewhere.

Hints are found in all genres. They are frequently used in the genres that are most distanced and formal in Koch and Oesterreicher’s (1985/2012) approach, Broadcast discussions and Legal presentations. But they are also frequent in the private, but formal Business transactions, while they are rarer in the least distanced Face-to-face and Telephone conversations.

Questions

Questions are a category of directives identified by Searle (1976). Questions require the addressees to react—not with a physical response but a linguistic one. Correspondingly, questions are also annotated as directives in the SPICE-corpus (Kallen & Kirk, 2012). Leech (2014) considers on-record indirect question strategies, but we can observe different degrees of directness in questions: questions addressed directly to an interlocutor are most impositive. The question may impact on the interlocutor’s negative face; it cannot remain unanswered without loss of face to at least one of the participants. Example 47 is a direct personal question, in a Broadcast discussion, where the respondent, the former Taoiseach, i.e. head of government, Garret Fitzgerald is invited to give an answer very publically.

-

47.

<P1B-034$H> <#> <icu> Right </icu> <#> <dir> Garret Fitzgerald what 's the life span in your view <,> </dir><P1B-034$A> <rep> Eight years possibly </rep> <&> laughter </&>

This category is not only the largest category of questions in the corpus (601 of 691, 87%), but also the largest single category of directives in the corpus (601 of 1085, 55.4%).

Hedged personal questions are less threatening to the respondents’ negative face; this is illustrated in example 48, asked by a student in a Classroom discussion.

-

48.

<P1B-013$D> <dir> Would it be necessary to actually quote figures or would it just be more of a a general ideas of proportions you-know@* </dir> <#> <dir> Like if we were saying say <,> there would you have to quote say the exact figures relating to how many people foreign firms uh were employing on the eastern seaboard or would it just be better to say the uhm that the the Irish firms employ twice as many as the foreign firms or would you actually be looking for figures </dir>

These hedged personal questions are rare (6 examples of the 601 personal questions, 1%). But it is noteworthy that all 6 examples stem from students asking instructors in the Classroom discussions. Here it seems as if the power differential in the classroom led the students to hedge the questions.

In addition to personal questions, we also find questions that are asked indirectly, or to no-one in particular. As a result, the question that is indirect or not aimed at a specific respondent does not put an individual under the same amount of obligation to answer as a direct personal question, which, in contrast to the indirect question strategies, asks for action rather than querying the preconditions to the action. Example 49 is asked in a workplace, 50 is asked inside a classroom, to no specific person.

-

49.

<P1B-078$A> <rep> The <,> just the dysphagia policy was to be altered </rep> <#> <dir> Did anyone know about that </dir> <#> <P1B-078$B>

-

<rep> Oh yes </rep> <#>

-

50.

<P1B-011$B> And you have to give them you’re their legal statutory right </rep> <dir> isn't it three months off isn't-it </dir>

This category is relatively infrequent in the corpus (22 examples of the total of 691 questions, 3.1%). It is most frequent in the Broadcast discussions, where the questions may be addressed to a larger panel of participants rather than one specific interlocutor.

Finally, rhetorical questions or implied questions do not expect an answer.

-

51.

<P1B-011$A> I saw CIaran standing up here last week as some kind of class rep <,> </rep> <dir> correct or <,> no <,,> </dir> <#> <rep> situation announcing him <,>

-

52.

<P1A-098$B> <#> <com> <[> Aye* well* I 'll tell you what </[> </{> the thing 2Is 2rIght%@* </com> <#> <xpa> I am actually uhm <,> I am actually <,> </xpa> <dir> 1whAt am I 1dOing% </dir> <#> <rep> I 'm changing 1wArds% </rep> <#>

In examples 51 and 52, the speakers answer their own questions, no verbal uptake is needed from the interlocutors. 68 of the 691 questions (9.8%) in the corpus belong to this category. The largest percentage of these is found in the Face-to-face discussions (38 of 68, 55.9%). However, particularly in the Classroom discussions, we also repeatedly find that the lecturers are answering their own rhetorical questions (15 of 68 examples, 22.1%).

Generally, questions account for the largest category annotated as directives in the investigated categories in the SPICE-corpus (691 of 1,085 directives, 63.7%). The presence of questions is extremely dependent on the genre of text: while the Legal presentations only contain 1 example of a question (0.1% of all questions), a rhetorical one, Face-to-face communications lead at 256 examples (37%), followed by Classroom discussions at 110 examples (15.9%). This overview shows us that the category of text plays a large role in the number of questions and overall directives in the data.

The Impact of Immediacy and Distance of the Genre

The highest attestation of directives is found in Face-to-face conversations, followed by Telephone conversations, Classroom discussions, Business conversations, Broadcast discussions and Legal interactions (Fig. 4).

Figure 4 shows that in the most private type of conversations, Face-to-face communications, the number of directives is highest. By contrast, directives are rare in the most formal categories, the Legal presentations, and occupy a middle ground where the spoken language has traits that are more typical of language of distance (Koch & Oesterreicher, 1985/2012): there is either a spatial distance between familiar participants who cannot see each other (Telephone conversations) or the setting is public (Classroom or Broadcast discussions) or reflective and detached (Business transactions). We may hypothesize that people who are close need to be less polite and informal situations will allow for more directness than more formal ones. Table 3 and Fig. 5 show how the different categories of directives are distributed amongst the genres investigated here.

Table 3 and Fig. 5 show that not only questions but also direct strategies are best attested in the private, Face-to-face communication. In the more public Broadcast and Classroom discussions, the less direct on-record statements and hints are comparatively more frequent. Thus it indeed seems that to preserve your interlocutor’s face is more relevant in more public interaction than in more private discourse.

Overall, the data from the select SPICE categories shows that in spite of the well-known high-considerateness style of Irish English (Barron, 2005, 2008; Kallen, 2005), impositive strategies are the most frequent type of directive in the data, besides questions, which are not the main focus of this study. Of the impositive strategies, the maximally impositive direct strategies are the most attested strategies. These appear particularly frequently in private, familiar discourse, Koch and Oesterreicher’s (1985/2012) “language of immediacy”. In the less private, more public genres, which correspond more to “language of distance”, the use of indirect strategies is more frequent than in private genres, here the public preservation of face is of large importance. This observation, however, awaits confirmation from the investigation of larger data sets.

Conclusion

The present study has shown that the pragmatically annotated SPICE-Ireland corpus provides an excellent tool for the investigation of speech acts. On the basis of naturally occurring data, we can obtain both qualitative and quantitative information.

The question of in how far impositive directive speech acts are found in spoken Irish English data has received the answer that, apart from the highly frequent questions which merit more intense investigation elsewhere, impositive strategies are the most frequently used strategy in the corpus data, and that the strategies with the highest level of imposition, direct strategies, are the most frequently used strategies. In answer to the second research question, it has further been argued that we indeed observe an influence of the level of familiarity of the discourse: in more private the discourse, interactants use more impositive strategies. By contrast, categories that represent language of distance, where the participants either are less close or where the discourse is more public or more formal, show higher incidences of indirect strategies.

However, the analysis is so far based on a small data set, and more detailed study on the basis of larger data sets is desirable to confirm the results.

Availability of data and material

The ICE Ireland and SPICE corpora are freely available after registration,

Code availability

Not applicable

References

Anthony, L. (2018). AntConc (Version 3.5.7) [Computer Software]. Waseda University. Available from https://www.laurenceanthony.net/software.

Barron, A. (2005). Offering in Ireland and England. In A. Barron & K. P. Schneider (Eds.), The Pragmatics of Irish English (pp. 14–176). Mouton de Gruyter.

Barron, A. (2008). The Structure of Requests in Irish English and English English. In A. Barron & K. P. Schneider (Eds.), Variational Pragmatics: A focus on regional varieties in pluricentric languages (pp. 35–67). Mouton de Gruyter.

Barron, A., & Schneider, K. P. (2005). The Pragmatics of Irish English. Mouton de Gruyter.

Biber, D. (1988). Variation across speech and writing. Cambridge University Press.

Blum-Kulka, S., House, J., & Kasper, G. (Eds.). (1989). Cross-cultural pragmatics: Requests and apologies. Ablex.

Collins, P. (2004). Let-imperatives in English. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, 9(2), 299–319.

Corrigan, K. P. (2010). Dialects of English: Irish English, Northern Ireland. Edinburgh University Press.

Ervin-Tripp, S. (1976). Is Sybil there? The structure of some American English directives. Language in Society, 5(1), 25–66.

Farr, F. (2005). Relational strategies in the discourse of professional performance review in an Irish academic environment: The case of language teacher education. In A. Barron & K. P. Schneider (Eds.), The Pragmatics of Irish English (pp. 203–233). Mouton de Gruyter.

Farr, F. & O’Keeffe, A. (2002). Would as Hedging Device in an Irish Context: An Intra-Varietal Comparison of Institutionalised Spoken Interaction. In R. Reppen, S. M. Fitzmaurice & D. Biber (Eds.), Using Corpora to Explore Linguistic Variation (pp. 25–48). John Benjamins.

Kallen, J. L., & Kirk, J. M. (2007). ICE-Ireland: Local Variations on Global Standards. Synchronic DatabasesIn J. C. Beal, K. P. Corrigan, & H. L. Moisl (Eds.), Creating and Digitizing Language Corpora (Vol. 1, pp. 121–162). Palgrave Macmillan.

Kallen, J. (2005). Politeness in Ireland: ‘In Ireland, It’s Done Without Being Said’. In L. Hickey & M. Stewart (Eds.), Politeness in Europe (pp. 130–144). Multilingual Matters.

Kallen, J. L., & Kirk, J. M. (2008). ICE-Ireland: A User’s Guide. Cló Ollscoil na Banríona.

Kallen, J.L., & Kirk, J. M. (2012). SPICE-Ireland: A User’s Guide. Cló Ollscoil na Banríona.

Koch, P., & Oesterreicher, W. (1985/2012). Language of Immediacy – Language of Distance: Orality and Literacy from the Perspective of Language Theory and Linguistic History. In C. Lange, B. Weber & G. Wolf (Eds.), Communicative Spaces. Variation, Contact, and Change: Papers in Honour of Ursula Schaefer. (pp. 441–473). Peter Lang.

Kohnen, T. (2008). Directives in old English: Beyond politeness? In A. H. Jucker & I. Taavitsainen (Eds.), Speech acts in the history of English (Pragmatics & Beyond New Series 176) (pp. 27–44). Benjamins.

Kohnen, T. (2002). Methodological problems in corpus based historical pragmatics. The case of English directives. In K. Aijmer & B. Altenberg (Eds.), Language and Computers, Advances in Corpus Linguistics. Papers from the 23rd International Conference on English Language Research on Computerized Corpora (ICAME 23). Göteborg 22-26 May (pp. 237–247). Rodopi.

Leech, G. (2014). The pragmatics of politeness. Oxford University Press.

Mato-Míguez, B. (2016). The expression of directive meaning: A corpus-based study on the variation between imperatives, conditionals and insubordinated if-clauses in spoken British English. In M. J. López-Couso, B. Méndez-Naya, P. Núñez-Pertejo & I. Palacios-Martínez (Eds.), Corpus linguistics on the move: Exploring and understanding English through corpora (Language and Computers Series) (pp. 291–312.). Brill/Rodopi.

Moessner, L. (2010). Directive speech acts. A cross-generic diachronic study. Journal of Historical Pragmatics11(2), 219–249.

Murphy, B. (2009). “She’s a fucking ticket”: The pragmatics of FUCK in Irish English – an age and gender perspective. Corpora, 4(1), 85–106.

Nelson, G., Wallis, S., & Aarts, B. (2002). Exploring natural Language: Working with the British component of the International Corpus of English. Benjamins.

Ronan, P. (2014). Talking about friggin’ health food: Expletives in Irish English. In A. Soltysik & A. Langlotz (Eds.), Emotion, Affect, Sentiment: The Language and Aesthetics of Feeling (pp. 157–176).

Schneider, K. P. (2005). No problem, you’re welcome, anytime: Responding to thanks in Ireland, England and the USA. In A. Barron & K. P. Schneider (Eds.), The Pragmatics of Irish English (pp. 101–139). Mouton de Gruyter.

Schweinberger, M. (2018). Swearing in Irish English – A corpus-based quantitative analysis of the sociolinguistics of swearing. Lingua, 209, 1–20.

Searle, J. R. (1976). A Classification of Illocutionary acts. Language in Society, 5(1), 1–23.

Sinclair, J. M., & Coulthard, M. R. (1974). Towards an analysis of discourse. Oxford University Press.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This research is not supported by external funding

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Not applicable

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interests

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ronan, P. Directives and Politeness in SPICE-Ireland. Corpus Pragmatics 6, 175–199 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41701-022-00122-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41701-022-00122-x