Abstract

Wellness tourism is a fast-growing tourism industry segment and major wellness tourism destinations are found in the Asia–Pacific region, including India. The region of Kerala in India has an abundant natural, cultural and entrepreneurial resources for the development of wellness tourism. These resources are centered on the unique and traditional Ayurveda treatment, complemented by impressive natural landscapes and rich cultures and history. Despite the abundance and quality of resources and services provided by a large number of stakeholders, Kerala lacks a branding strategy for differentiating Kerala as a wellness tourism destination to compete in international markets. A stakeholder-based participatory process was developed to co-create a branding strategy, involving a destination audit supported by an online conjoint analysis survey to discover the relative importance of ‘high-level’ attributes associated with Kerala’s wellness tourism resources. The most important attributes are ‘Fits with strategic priorities of the organisation’ and ‘Ability to integrate into wellness tourism packages’. The main resources complementing wellness services are natural features and cultural heritage. This research contributes to stakeholder-based participatory methods for destination branding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Tourism is a significant economic activity that benefits local and national economies around the world. It increases employment opportunities, incomes and living standards (Mondal, 2020). Wellness tourism is a fast-growing tourism segment which accounted for US$639 billion of spending worldwide in 2017 (Romão et al., 2017; Yeung and Johnston, 2018; Kazakov and Oyner, 2021). Wellness tourism can be broadly defined as travel by people who “proactively pursue activities that maintain or enhance their personal health and wellbeing, and who are seeking unique, authentic or location-based experiences and therapies not available at home” (Johnston et al., 2011). Major wellness tourism destinations are found in the Asia–Pacific region, including India (the subject of this article).

With 56 million domestic and international wellness tourists and $16.3 billion of spending (supporting 3.7 million jobs), India was the seventh-largest wellness tourism market in 2017—second only to China in the Asia–Pacific region (Kumar, 2019). During 2015–17, wellness-related trips increased by 20.4% for India and 20.6% for China—the fastest country growth rates in the region (Yeung and Johnston, 2018). Despite wellness tourism being an important tourism segment in India, its branding has been weak (Ravichandran and Suresh, 2010). Countries in the Asia–Pacific compete against each other in attracting wellness tourists, and so branding has become an important factor for creating a perception of a destination’s distinctiveness (Poorani and Jiang, 2017).

Page and Cornell (2020) proposed that destination branding must contribute to differentiating and distinguishing each destination by promoting its attractive features in a credible, plausible and deliverable way. A brand should rely on favourable attributes of the destination that are important to the target segment, so that its positioning guarantees congruence between identity and image. Pike (2021) defines branding as a co-creation process that includes: the identification of the brand community, a destination audit to identify sources of competitive advantage, an analysis of a brand image, and the production of a brand charter for stakeholders. Such a process may contribute to the consolidation of local knowledge and networks, which are perceived as crucial elements of the “soft infrastructure” of a “learning destination” (Campbell, 2009; Benckendorff et al., 2019). By using Information Technologies (IT) to involve local stakeholders, this process of co-creation (Binkhorst and Dekker, 2009) opens up new opportunities for interaction and cooperation between stakeholders to develop “learning destinations”.

Learning destinations are characterised as providing ubiquitous access to new IT tools to stakeholders, enabling systematic and effective instruments for accessing knowledge and information, encouraging a culture that favours innovation and mechanisms to ensure active participation of all stakeholders (Racherla Hu and Hyun, 2008). These advancements are also expected to support new forms of destination management and governance (Sigala and Marinidis, 2012), as proposed for consolidating smart tourism destinations (Boes et al., 2016). Moreover, the generalisation of these collaborative practices based on IT offers a clear contribution to the development of managerial roles and competencies related to data management and analytics by local stakeholders (Busulwa et al., 2021).

The territorial context of this study is Kerala, a region in India popularly known as “God’s own country”. Kerala has abundant natural, cultural and entrepreneurial resources for the development of wellness tourism centred on the unique and traditional Ayurveda treatment complemented by impressive natural landscapes and rich cultures and history. However, despite the abundance and quality of relevant wellness-related resources and services provided by a large number of stakeholders, Kerala lacks a branding strategy for differentiating itself as a wellness tourism destination to compete in international markets (Thornton, 2015; Ravisankar, 2018). Supported by well-established concepts and methodologies for the definition of branding strategies, the main contribution of our study is to reveal that such a strategy can be effectively built with the strong participation of the local community, in a process of co-creation based on a solid theoretical framework. This study also demonstrates the relevance of a specific digital tool (1000 minds software) and analytical method (PAPRIKA) in order to perform a conjoint analysis, a suitable methodology for these purposes.

Based on the results of the conjoint analysis, principles for a strategic branding process for Kerala are presented and discussed by identifying the resources perceived as main sources of competitive advantage and assessing the main attributes for their effective utilisation within a strategy for wellness-tourism development. This approach considers previous studies focusing on the role and importance of local resources for this type of tourism (Heung and Kucukutsa, 2013; Medina‐Muñoz and Medina‐Muñoz, 2014) while integrating local stakeholders in an innovative participatory strategic assessment. By achieving clear, objective and relevant results, this process can be seen as a meaningful form of collaboration (Blichfeldt, 2018), with a high potential to open up opportunities for further developments based on collaborative practices.

The paper proceeds as follows. An overview of wellness tourism in Kerala is presented in the next section, including a description of the complex network of stakeholders involved in the provision of core, facilitating and supporting services that constitute the “augmented product” (Kotler et al., 2017) for wellness tourism. In Sect. 3, the innovative contribution of this work as a meaningful form of developing collaborative practices with a strategic purpose is framed within the literature on branding studies, aimed at defining principles for a stakeholder-based branding strategy for Kerala. In Sect. 4, the conjoint analysis survey used to conduct the destination audit of Kerala is explained, followed by a discussion of the survey results. Finally, the paper closes with a discussion of the policy and managerial implications of the study’s findings and opportunities for further research to define a common branding strategy and reinforce participatory ‘smart’ governance principles.

2 Literature review

Wellness practices and their associated travel motivations have very ancient roots (Steward, 2012; Walton, 2012). The emergence of modern forms of wellness tourism, albeit often rooted in traditional practices, are based on contemporary trends in health care (Cohen and Bodeker, 2008). These contemporary trends include preventive, proactive and holistic behaviours intended to increase emotional, personal, physical and spiritual wellbeing. In a recent study, Smith and Diekmann (2017) synthesised the main motivations of wellness tourists as pleasure and hedonism (fun, rest and relaxation), meaningful experiences (education and self-development) and community engagement (environmental-friendly consumption patterns or actions in support of local communities).

Based on this synthesis, Romão et al. (2018) developed a framework for systematising the resources, activities and entrepreneurial initiatives needed to develop wellness tourism in rural areas. The authors’ framework considered three spatial levels: the establishment (accommodation, food and beverages and diverse wellness services), the destination (natural landscapes and cultural heritage) and the broader region (transport systems, alternative tourism attractions or urban areas). This framework is embraced in the current study, leading to the systematisation of local services and stakeholders.

Achieving a competitive position in the global wellness tourism industry depends on the uniqueness and differentiation of each wellness tourism experience (Chen et al., 2008; Huijbens, 2011). The development of wellness practices based on traditional aspects of local cultural heritage is linked to special characteristics; and, in addition, natural landscapes may support strategies for product differentiation. In the case of Kerala, which is predominantly a rural area with abundant and rich natural resources, traditional Ayurveda practices can constitute the core element of this type of strategic approach, complemented by other local resources to create a competitive ‘augmented product’, deeply embedded in local resources and communities. However, the implementation of such a strategy for wellness tourism development implies strong coordination between different stakeholders (Page et al., 2017), relying on the same territorial resources (Kotler et al., 2017), which can be seen as a process of co-creation of tourism experiences (Binkhorst and Dekker, 2009).

To promote a destination with abundant local resources for wellness tourism in an international market, the region needs to develop a strong and recognisable brand. According to Blain et al. (2005), in general terms, a strong and recognisable brand should reflect and synthesise the main ideas and attributes defining an identity (from the point of view of producers) and an image of the services (from the perspective of consumers). A brand involves defining a name (or wordmark) and graphic symbols identifying and distinguishing the destination, which should create expectations of a memorable experience while reinforcing the emotional connection between tourists and destinations. However, Morrison (2019) suggests that the branding process is more related to the management of a destination’s reputation than to the creation of logos and slogans. The main objective of creating a brand identity is to promote a positive image differentiating the destination from its competitors, while increasing its awareness, recognition and memorability over time to potential visitors.

In contrast to branding by individual companies, the creation of brands for tourism destinations implies the need for a large number and wide range of stakeholders to be involved (Ruiz-Real et al., 2020; Cox et al. 2014; Hosany et al., 2006; Hankinson, 2009). This diversity of stakeholders constrains their individual ability to influence the image and reputation of the destination as perceived by tourists (Govers et al., 2007). As the destination comprises different types of tourism services, the brand must be widely recognised and accepted by the stakeholders involved, which increases its complexity (Fyall and Garrod 2020). On the other hand, branding a territory implies an interactive process in which all stakeholders involved assume a common understanding and strategic purpose, which entails the co-creation of relevant and meaningful forms of communication between them (Blichfeldt, 2018). A destination brand that has evolved through co-creation is considered a source of long-term competitive advantage for all stakeholders within the tourism ecosystem (Giannopoulos et al., 2021).

The advantages of stakeholder collaboration are well documented in the literature, generating different types of positive effects. Moscardo (2019) emphasises the contribution for capacity building with local communities arising from their involvement in tourism planning processes, while Kotler et al. (2017) focuses on the “collaborative advantages” arising from the joint efforts of organised stakeholders, defining key characteristics for such a process as the independence of stakeholders, the emergence of solutions based on a constructive discussion of differences, joint ownership of the decisions, collective responsibility for the resulting decisions and actions, and collaboration is an emergent process. By assuming these characteristics in the co-creative process developed in this work, we expect to contribute to the achievement of the potential benefits of stakeholder collaboration systematised by Bramwell and Lane (2000): mobilisation of knowledge from the involvement of many and diverse stakeholders facing similar problems and challenges, diffuse decision-making power and control, increasing responsibility for implementation and social acceptance of solutions, more constructive attitudes towards planning outcomes, potential inter-organisational learning and related innovation capabilities, better coordination in action and collective use of resources, and sensitivity to local circumstances.

In this context, Pike (2021) adapts the formulations proposed by Keller (2000) to propose several steps in the definition of a destination brand identity: identification of the brand community, a destination audit to identify the main sources of competitive advantage, an analysis of the brand image, and the production of a brand charter for stakeholders. The present study focuses on the first two steps of this process: identification of the brand community (through an exhaustive list of the relevant stakeholders for the production of wellness services), followed by identification of the most important attributes associated with wellness tourism resources supporting a competitive strategy for destination differentiation in Kerala. Several techniques for performing a destination audit are identified in the literature (Pike, 2021), involving the evaluation of macro aspects (focusing on a broad context of tourism development) or micro aspects (focusing on the organisation). These techniques include STEEPL analysis (oriented to the identification of possible opportunities and threats in the macro environment), SWOT analysis (combining internal and external factors influencing the development of tourism destinations), and the VRIO resource model (focusing on the resources of the destination as potential sources of competitive advantage).

The present study employs a methodology inspired by the VRIO model. Under the realistic assumption that wellness tourism currently benefits from a highly favourable external context with increasing market opportunities—i.e. India is already a well-recognised tourism destination—the analysis will focus on the resources of the region of Kerala. The set of resources to be evaluated and analysed was initially defined taking into consideration the major motivation of wellness travellers identified in the literature (Chen et al. 2008; Smith and Diekman, 2017), the related classification of territorial resources proposed by Romão et al. (2018) and their potential contribution of the differentiation of wellness destinations, as suggested by Huijbens (2011). Moreover, the adequacy of this set of resources would be confirmed through a detailed expert assessment before the distribution of the survey to local stakeholders. Collaboration between a destination’s various stakeholders is a useful strategy for achieving its tourism potential (Fyall et al., 2012). Involving local stakeholders in the implementation of destination branding strategies has been tested in several places (Eugenio-Vela et al., 2020; García et al., 2012), with important limitations having been observed for the relationship between differentiation strategies, stakeholder involvement and destination management, as discussed by Blain et al. (2005).

A major original contribution of the present study is the utilisation of digital technologies for the implementation of a participatory methodology, involving a representative and large sample of relevant stakeholders, thereby generating clear and meaningful results. The objective is to combine a macro-approach (identifying the most relevant resources to support a strategy of differentiation for wellness tourism markets) with a micro-approach (how can these resources be efficiently used by the organisations involved) that can be used to mobilise the local stakeholders for a common strategic approach to wellness tourism branding. An online survey implementing conjoint analysis was implemented incorporating the potentially most relevant resources (as identified in the literature) with attributes for differentiating between them (defined by expert assessment) and involving experts in trading off resources based on the multiple attributes. Such a process based on the expert judgement has been adopted in previous tourism studies (Crouch, 2011; Moutinho et al., 1996). Digital (online) technologies can stimulate interaction and cooperation between stakeholders in new forms of destination management and governance (Sigala and Marinidis, 2012), offering relevant and meaningful results (Blichfeldt, 2018), while contributing to the implementation of governance models in accordance with the principles proposed for the emergence of smart tourism destinations (Boes et al., 2016).

3 Research setting

Kerala, a south-western state of the Republic of India, is lined with 600 km of sandy beaches bordering the Arabian Sea on one side and spice, tea and rubber plantations and the Western Ghats’ forests on the other side. With its “God’s Own Country” super brand, Kerala is an important tourism destination in India and a major hub of Ayurveda-based wellness services.

Rated by a BBC travel survey as the most preferred tourist destination among foreign travellers (IBEF 2018) and branded as the “Land of Ayurveda”, Kerala has been promoted as a truly authentic place of wellness tourism (Global Wellness Institute, 2019). Outlook Traveller magazine judged Kerala as India’s best wellness destination because of its Ayurveda and traditional holistic healing processes (Department of Tourism, Kerala, 2020). Kerala uses wellness tourism to differentiate itself from other states in India (Bandyopadhyaya and Nair, 2019), offering wellness packages with new-age Ayurveda combined with a pleasant holiday under the palm trees (Kannan and Frenz, 2019).

In 2018, more than 1.09 million foreign tourists and 15.60 million domestic tourists visited Kerala, an increase of 0.42% and 6.35% respectively relative to 2017 (Kerala Tourism Statistics, 2018). Overall, the state recorded a 6% increase in tourist arrivals in 2018 – despite having been affected by a Nipah virus scare and flooding (The Hindu, 2019). Total revenue (direct and indirect) from tourism in 2018 was US$5299.33 million, an annual increase of 8.61%, with US$1252.06 million of foreign exchange earnings, an annual increase of 4.44% (Kerala Tourism Statistics, 2019). Ayurveda, a traditional Indian system of medicine, is a unique selling proposition for Kerala as a wellness tourism destination. Supported by a large number of Ayurveda wellness centres spread across the state, the most commonly offered Ayurveda wellness services are detoxification, rejuvenation, weight loss, stress relief, anti-aging and skin and hair care (Ramesh and Kurian, 2012). Ayurveda is also used to treat back pain, arthritis, asthma, diabetes, neurological disorders and other lifestyle-related diseases.

These wellness services are mostly offered by Ayurveda hospitals and Wellness, massage, spa and therapeutic centres attached to hotels, resorts and standalone Ayurveda centres. The scale of operation ranges from two-bed Ayurveda massage centres to sophisticated Ayurveda hospitals with up to 360 beds offering speciality Ayurveda care for eye, arthritis, skincare, mental health and obesity-related ailments. Condé Nast Traveller, a renowned international travel magazine, identified some of Kerala’s best Ayurveda centres and brands (Kumari, 2017), including Kottakkal Arya Vaidysala, Vidya Ratnam, Sarovaram, Somatheeram, Kairali, Perumbayil and Athreya. As well as the Ayurveda system of medicine, Naturopathy, Siddha and Unani also contribute to Kerala’s wellness infrastructure (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, 2014). Data on the availability of these four types of wellness services are presented in Table 1.

To encourage quality standards and uniformity, the Indian Government’s Department of Tourism introduced an accreditation system whereby accredited wellness centres are classified into two categories: Green Leaf or Olive Leaf (DeMicco, 2017). Green Leaf centres focus on luxury, hospitality, customer experience, and treatment outcomes, whereas Olive Leaf centres are expected to fulfil minimum-prescribed quality and service standards. Wellness centres have to go for reaccreditation every five years. In 2019, the Government of Kerala introduced a new accreditation system for wellness centres with three categories: Ayur Silver, Ayur Gold or Ayur Diamond. Ayur Silver-rated centres ensure minimum standards are met, and, at the other extreme, Ayur Diamond-rated centres promise top-end wellness-service infrastructure and luxury customer experiences. All classified Ayurvedic wellness centres are required to append the term “Kerala Tourism Ayurveda Centre’ to their name on brochures, signage and communications (Hindu, 2019). The number of accredited wellness centres in Kerala’s districts (Department of Tourism, Kerala, 2019) is reported in Table 2. In addition, more than a thousand wellness centres are not accredited. The data in the table reveal that accredited Ayurveda wellness centres are unevenly distributed: 80% of the centres are located across just five of Kerala’s districts.

Kerala—India’s tourism super brand—is perceived by researchers, branding professionals and wellness service providers to aspire to being an international wellness brand (Ravisankar, 2018). Unfortunately, however, many observers consider that Kerala’s “God’s Own Country” brand has lost some of its vigour, charm, and magnificence to attract international travellers from around the world. Strategic weaknesses include the absence of unified branding by stakeholders, the lack of harmonised efforts to promote the state as a world-class wellness destination and an inability to project the complementary nature of Ayurveda with Allopathy treatments (Thornton, 2015; Ravisankar, 2018). Therefore, it is time to reinvigorate Kerala’s branding strategy via a participatory process. Furthermore, creating synergies among all tourism and health care service providers is key to Kerala becoming a global leader (Thornton, 2015).

4 Methods

Supported by a detailed overview of the resources and stakeholders involved in wellness tourism services centred on Ayurveda, this work adopts an exploratory approach for destination audit in Kerala, based on a participatory process involving a large number of local stakeholders via a conjoint analysis (Green and Srinivasan, 1978) supported by digital technologies. By analysing and prioritising crucial resources to redefine potential core and facilitating products (Kotler et al., 2017), such a participatory process enables a more accurate identification of Kerala’s competitive advantages, along with the potential to mobilise the community of local stakeholders for the common strategic purpose of promoting the development of wellness tourism. When there is no legal requirement for a common brand to be used for a destination, this mobilisation may contribute to a generalised adoption by individual stakeholders, which depends on common territorial resources and may achieve better results via collaboration than working individually (Fyall et al., 2019; Mason, 2019). By involving the brand community via a conjoint analysis, a more precise, informed and representative assessment of the relevant resources and their attributes for the evaluation of their commercial potential can be achieved (Munro et al., 2006). The participatory process for identifying the brand community, the attribute and their weights and applying them to rank Kerala’s five most important wellness tourism resources is summarised in Fig. 1.

This participatory process is also expected to reinforce the social capital and involvement of the local community with the development of the brand, and may contribute to improving the level of organisation of retreat operators, which, as observed by Kelly (2010), appears to be less structured than spa-oriented services within the wellness tourism industry. Though this research provides a solid background for the implementation of the next steps for a branding strategy proposed by Pike (2021), an analysis of the brand image (Souiden et al., 2017) may constitute a next stage before the production of a brand charter for local stakeholders.

Conjoint analysis—also known as choice modelling or discrete choice experiments (McFadden, 1974)—is a widely used technique for marketing research and social science research (depending on the area of application) for finding out what people care about when making choices involving trade-offs between the alternatives of interest. In the present context, local stakeholders were surveyed to discover the relative importance of various ‘high-level’ attributes associated with Kerala wellness tourism resources for differentiating Kerala as a wellness tourism destination to compete in international markets. These attributes associated with Kerala wellness tourism resources for differentiating Kerala as a wellness tourism destination were determined in consultation with a sub-group of stakeholders accessed through the fourth and fifth authors’ professional and personal networks. Because the weights on the attributes, representing their relative importance to stakeholders—often referred to as ‘part-worth utilities’ in the conjoint analysis literature—are to be determined using an online survey (explained below), the attributes, and the levels within each attribute, need to be specified concisely using language that most survey participants would be likely to understand. The final specification of the attributes and levels was validated and refined in consultations with the sub-group of stakeholders and the survey was pilot-tested before being implemented in full. The six attributes (and their levels) are presented in Table 3.

The conjoint analysis survey was implemented using 1000minds software (www.1000minds.com), which implements the PAPRIKA method – an acronym for Potentially All Pairwise RanKings of all possible Alternatives (Hansen and Ombler, 2008). The software and method have been used in a wide range of business-related areas; recent examples include measuring businesses’ reputations (Whiting et al., 2017), transport infrastructure planning (Miller and Gransberg, 2017), marketing research (Mirosa et al., 2020; Parsad et al., 2019) and for understanding wellness tourism in Japan (Romão et al., 2018).

In the present context, the PAPRIKA method involves survey participants being asked to pairwise rank two hypothetical Kerala wellness tourism resources, defined on two attributes at a time, in terms of which resource is more important for differentiating Kerala as a wellness tourism destination to compete in international markets. Each choice requires the participant to confront a trade-off between the two attributes included for the pair of wellness tourism resources (where the four other attributes are, in effect, assumed to be the same for both resources). An example of a pairwise-ranking question appears in Fig. 2.

Such questions (always involving a trade-off between the attributes, two at a time) are repeated with different pairs of hypothetical Kerala wellness tourism resources. Each time the participant answers a question—i.e. ranks a pair of resources (including potentially ranking them equally)—all other pairs of resources that could be pairwise ranked by applying the logical property of transitivity are identified and eliminated by the software. For example, if a person prefers wellness tourism resource X to resource Y and Y to Z, then—by transitivity—X is also preferred to Z (and so is not asked about by the software). Also, each time a person answers a question, based on all preceding answers, PAPRIKA adapts with respect to choosing the next question (always one whose answer is not implied by earlier answers). Thus, PAPRIKA is a type of adaptive conjoint analysis. This adaptivity combined with the above-mentioned elimination procedure based on transitivity results in the number of questions a participant is asked being minimised while ensuring they end up having pairwise ranked all possible hypothetical Kerala wellness tourism resources defined on two attributes at a time, either explicitly or implicitly (by transitivity).

From the participant’s explicit pairwise rankings (i.e. answers to the questions) the software uses quantitative methods to derive weights (‘part-worth utilities’) for the levels on each attribute; for technical details, see Hansen and Ombler (2008). As well as weights for each participant, these individual outputs are averaged across all participants to derive mean weights for the sample as a whole. The quality of participants’ answers to the pairwise-ranking questions was assessed in several ways by the 1000minds software, with the objective of identifying and excluding ‘low quality’ data from the final dataset. The consistency of each participant’s choices was tested by repeating two previously answered pairwise-ranking questions at the end of the survey. Also, the time each participant took to answer each question was recorded. Participants who answered both repeated questions inconsistently and/or answered their questions implausibly quickly (median time of less than three seconds per question) were excluded from the final dataset.

Finally, the mean weights were applied to ratings produced by local stakeholders of Kerala’s five most important wellness tourism resources—wellness services, natural attractions, cultural resources, local gastronomy and handicrafts and recreational and recreational activities—to produce a ‘total score’ for each resource. The aim of this process is to rank the resources, based on their total scores, in terms of their overall importance for differentiating Kerala as a wellness tourism destination, to compete in international markets.

5 Results

5.1 Survey participants

The conjoint analysis survey was completed by 263 people, including service providers from the wellness, hospitality and tourism industries and tourism planners in the private and government sectors. Seventy participants were excluded because they failed the data quality checks: 38 answered both repeated questions inconsistently and/or 32 answered their questions implausibly quickly. Thus, the final dataset comprised 193 participants. These participants answered 28 questions each on average (mean), taking most of them 5–10 min in total. Of the 193 participants, 115 (60%) were male and 78 (40%) female; 62 (32%) were aged 18–24, 39 (44%) aged 25–45, and 3 (24%) older than 45. With respect to their sector, 61 (32%) people worked in hospitality services, 52 (27%) were wellness service providers, 31 (16%) provided tourism-related services and 25 (13%) were in tourism-related institutions of both state and central government. With respect to their education, 74 (38%) had bachelor degrees, 89 (46%) had master degrees and 30 (16%) had either matriculation or a diploma.

5.2 Attribute weights and relative importance

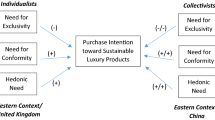

The mean weights of the six attributes and their levels, representing their relative importance to participants on average, are reported in Table 4. The relative importance of the six attributes is also represented in the radar chart in Fig. 3.

As can be seen in the table and figure, on average the most important attribute in terms of resources for differentiating Kerala as a wellness tourism destination to compete in international markets is ‘Fits with strategic priorities of the organisation’ (22% relative importance). The second-most important attribute is ‘Ability to integrate into wellness tourism packages’ (18%), followed by ‘Attractiveness for wellness tourists’ (17.3%), ‘Perceived quality of the resource’ (15.2%) and ‘Cost-effectiveness’ (14.1%). The least important attribute is ‘Possibility of being used in a short time’ (13.5%).

Based on each participant’s set of weights and their corresponding ranking of the six attributes, the proportions of the 193 participants who ranked the attributes first to sixth are reported in Table 5.

5.3 Ranking of Kerala’s wellness tourism resources

The rating of Kerala’s five most important wellness tourism resources by local stakeholders, their total scores (out of a maximum of 100%) from applying the mean weights (Table 4) to the ratings and their ranking are reported in Table 6. The top-ranked resource is wellness services, achieving the maximum possible score of 100% due to its high rating on each of the six attributes, followed by natural attractions. Cultural resources, local gastronomy and handicrafts and leisure and recreational activities are ranked third, fourth and fifth respectively.

6 Discussion and conclusions

The branding of tourism destinations is important as it differentiation and helps in sustaining competitive advantages (Morrison, 2019). Whereas the creation of branding strategies for a firm’s products typically involves just a few individuals, destination branding is a more complex activity that requires the involvement of a large number and wide range of stakeholders in a systematic process of co-creation (Binkhorst and Dekker, 2009). The complexity intrinsic to destination branding mainly arises due to a general shortage of mechanisms to identify and integrate the various stakeholders. A community participatory process is vital when creating a destination branding strategy because it reduces the negative environmental and social consequences of tourism development (Hankinson, 2009; Cooper and Hall, 2008; Hosany et al., 2006). Destination branding performed behind closed-doors is useless at reaching out to the brand community, and it usually unsuccessful (Baker, 2007).

The primary objective of this research was to implement a stakeholder-based participatory method for destination branding. Policy-makers, tour operators, travel agents, members of hospitality institutions, tourism-related entrepreneurs and wellness service providers were involved in the community participatory process to identify the most relevant tourism resources with respect to their strategic capabilities (Fyall et al., 2019). A spatial level framework for wellness tourism proposed by Romão et al. (2018) was adopted to identify the stakeholders and destination resources. Via a conjoint analysis survey, stakeholders were involved in prioritising the resources to be emphasised in branding Kerala as a wellness destination. Even though this case study does not propose a new conceptual or theoretical development for the definition of branding strategies, we create the conditions to support a process of collective decision with a rigorous and relevant theoretical framework. By achieving clear, meaningful and original results, expressing the unique point of view of the local community regarding their priorities for the implementation of a branding strategy, our work allows for the replication of similar methodologies in other contexts.

The conjoint analysis survey revealed that a resource’s fit with the organisation’s strategic priorities is the most important attribute for differentiating Kerala as a wellness tourism destination, followed by the ability to integrate into wellness tourism packages and the attractiveness for wellness tourists while deciding on the resources. Correspondingly, natural resources are perceived as the most important territorial assets to complement wellness tourism services, followed by cultural heritage. Once these features have been identified by the relevant stakeholders operating in the market, the utilisation of these territorial features is to differentiate Kerala as a wellness destination in a credible, plausible and deliverable way (as defined by Page and Cornell, 2020). As such, further developments of this analysis may lead to the subsequent stages of a branding process, by using these preferences to support the creation of a brand image and a brand charter for local stakeholders (Pike, 2021).

Globally, destinations that aim to position themselves as wellness destinations have to develop a holistic wellness model that integrates health, wellbeing and supporting services (Kazakov and Oyner, 2021). Kerala, with its unique natural resources, local culture and wellness resources such as Ayurveda, is capable of delivering a memorable experience to wellness tourists. Therefore, destination marketers in Kerala, in their effort to brand the state as a wellness destination, need to emphasise natural resources followed by wellness and other resources at the centre of their marketing communications. A destination’s uniqueness and differentiation are key to achieving competitive positioning—and so Kerala needs to package its tourism offerings by combining traditional wellness practices, including Ayurveda as a core element, along with natural resources and cultural heritage. Destination marketers need to emphasise these elements to strengthen Kerala’s brand as a wellness tourism destination.

The relevant, clear and meaningful results achieved (Blichfeldt, 2018) through a co-creation process reveal the adequacy of the online tools and methodologies implemented for this participatory strategic assessment. As a first contribution, this research reveals a process for identifying and involving multiple stakeholders and integrating them as a brand community using a spatial framework. This research may contribute to paving the way for the development of other collaborative practices in the future and to the consolidation of governance mechanisms consistent with the principles of smart tourism development (Boes et al., 2016).

Second, the study confirms the supportive role of technology in involving the brand community. A cost-effective online survey tool was utilised to enhance stakeholders’ participation in destination branding, allowing for the mobilisation of a large and diverse set of local stakeholders, while effectively integrating their individual perspectives to achieve a common, objective, relevant and meaningful result. This process reveals a good level of competencies of the local stakeholders for the utilisation of digital tools in data management and analytics (as defined by Busulwa et al., 2021), while reinforcing the mechanisms for their active participation in tourism planning and management (Racherla et al., 2008) and the “soft infrastructure” of a “learning region” (Benckendorff et al., 2019).

Third, the study extends prior works on the significance of destination resources and its strategic capabilities as perceived by stakeholders. The study also reveals the stakeholders’ priorities in selecting resources for destination branding. From a methodological point of view, the study confirmed the relevance of the conjoint analysis for this type of application involving diverse individual perspectives about different alternatives and related trade-offs. Moreover, the study revealed that the PAPRIKA method (implemented by 1000minds software) can be a powerful tool for the effective integration and assessment of these different perspectives due to its simplicity and intuitiveness to users, which is enhanced by the effectiveness of the associated online platform.

Though this research successfully demonstrated how to go about a stakeholder-based participatory destination branding exercise, it has several potential limitations. The data were collected from stakeholders who are recognised by the local government tourism board, which may limit the generalisability of the findings as there are also many small and family-owned wellness service providers in Kerala. The strategic capabilities of resources were determined a priori using expert opinions before the conjoint analysis survey; focus groups or qualitative interviews and discussions with different stakeholders may have revealed different perspectives on the strategic capabilities of tourism resources. As this study only considers the identification of a brand community and a destination audit to identify the source of competitive advantage, future studies could consider the analysis of brand image and the production of a brand charter for stakeholders. Notwithstanding these limitations, this explorative research work contributes to a better understanding of stakeholder-based participatory methods for destination branding. In the process, the co-creation methodology contributes to the reinforcement of ties between different stakeholders and local social capital, thereby opening up opportunities for further implementation of new collaborative strategic processes in tourism planning and management.

Availability of data

The data for the current study is available at Mendeley Data. https://doi.org/10.17632/96t8bknjc8.1.

References

Baker B (2007) Destination branding for small cities: the essentials for successful place branding. Creative Leap Books, Portland

Bandyopadhyay R, Nair BB (2019) Marketing Kerala in India as god’s own country! for tourists’ spiritual transformation, rejuvenation and well-being. J Destin Mark Manag 14:100369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2019.100369

Benckendorff PJ, Xiang Z, Sheldon PJ (2019) Tourism information technology. CABI, Oxfordshire

Binkhorst E, Den DT (2009) Agenda for co-creation tourism experience research. J Hosp Leis Mark 18:311–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368620802594193

Blain C, Levy SE, Ritchie JRB (2005) Destination branding: insights and practices from destination management organizations. J Travel Res 43:328–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287505274646

Blichfeldt BD (2018) Co-branding and strategic communication. In: Liburd L, Edwards D (eds) Collaboration for sustainable tourism development. Good Fellow Publishers, Oxford, pp 35–54

Boes K, Buhalis D, Inversini A (2016) Smart tourism destinations: ecosystems for tourism destination competitiveness. Int J Tour Cities 2:108–124. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-12-2015-0032

Bramwell B, Lane B (2000) Introduction. In: Bramwell B, Lane B (eds) Tourism, collaboration and partnerships: policy practice and sustainability. Channel View Publications, Clevedon, pp 1–23

Busulwa R, Evans N, Oh A, Kang M (2021) Hospitality management and digital transformation. Routledge, London

Campbell T (2009) Learning cities: knowledge, capacity and competitiveness. Habitat Int 33:195–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2008.10.012

Chen JS, Prebensen N, Huan T (2008) Determining the motivation of wellness travelers. Anatol An Int J Tour Hosp Res 19(1):37–41

Cohen M, Bodeker G (2008) Understanding the global spa industry: spa management. Elsevier, London

Cox N, Gyrd-Jones R, Gardiner S (2014) Internal brand management of destination brands: exploring the roles of destination management organisations and operators. J Destin Mark Manag 3:85–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2014.01.004

Crouch GI (2011) Destination competitiveness: an analysis of determinant attributes. J Travel Res 50:27–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287510362776

DeMicco F (2017) Medical tourism and wellness: hospitality bridging healthcare (H2H). CRC Press, London

Department of Tourism, Kerala (2019) Kerala Tourism Statistics 2018, Thiruvananthapuram: Department of Tourism. Government of Kerala. Retrieved from https://www.keralatourism.org/tourismstatistics/tourist_statistics_2018_book20191211065455.pdf.

Department of Tourism, Kerala (2020) Kerala adjudged Best Wellness Destination by Outlook Traveller. Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, India. Retrieved from https://www.keralatourism.org/articlesonkerala/23_02_202020200224050715_1.pdf.

Eugenio-Vela JDS, Ginesta X, Kavaratzis M (2020) The critical role of stakeholder engagement in a place branding strategy: a case study of the Empordà brand. Eur Plan Stud 28:1393–1412. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1701294

Fyall A, Garrod B (2020) Destination management: a perspective article. Tour Rev 75:165–169. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-07-2019-0311

Fyall A, Garrod B, Wang Y (2012) Destination collaboration: a critical review of theoretical approaches to a multi-dimensional phenomenon. J Destin Mark Manag 1:10–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2012.10.002

Fyall A, Legohérel P, CrochetI WY (2019) Marketing for tourism and hospitality—collaboration, technology and experience. Routledge, New York

García JA, Gómez M, Molina A (2012) A destination-branding model: an empirical analysis based on stakeholders. Tour Manag 33:646–661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.07.006

Giannopoulos A, Piha L, Skourtis G (2021) Destination branding and co-creation: a service ecosystem perspective. J Prod Brand Manag 30:148–166. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-08-2019-2504

Global Wellness Institute (2019) Global wellness tourism economy. Global Wellness Institute, Miami

Govers R, Go FM, Kumar K (2007) Promoting tourism destination image. J Travel Res 46:15–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287507302374

Green PE, Srinivasan V (1978) Conjoint analysis in consumer research: issues and outlook. J Consum Res 5:103. https://doi.org/10.1086/208721

Hankinson G (2009) Managing destination brands: establishing a theoretical foundation. J Mark Manag 25:97–115. https://doi.org/10.1362/026725709X410052

Hansen P, Ombler F (2008) A new method for scoring additive multi-attribute value models using pairwise rankings of alternatives. J Multi Criteria Decis Anal 15:87–107. https://doi.org/10.1002/mcda.428

Heung VCS, Kucukusta D (2013) Wellness tourism in China: resources, development and marketing. Int J Tourism Res 15(4):346–359

Hosany S, Ekinci Y, Uysal M (2006) Destination image and destination personality: an application of branding theories to tourism places. J Bus Res 59:638–642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.01.001

Huijbens EH (2011) Developing wellness in Iceland. theming wellness destinations the Nordic way. Scand J Hosp Tour 11:20–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2011.525026

Johnston K, Puczko L, Smith M, Elis S (2011) Wellness tourism and medical tourism: where do spas fit? Global Spa and Wellness Summit, Miami

Kannan S, Frenz M (2019) Seeking health under palm trees: ayurveda in Kerala. Glob Public Health 14:351–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2017.1417458

Kazakov S, Oyner O (2021) Wellness tourism: a perspective article. Tour Rev 76:58–63. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-05-2019-0154

Keller P (2000) Destination marketing: Strategic areas of inquiry. In: Manente M, Cerato M (eds) From destination to destination marketing and management. CISET, Venice, pp 29–44

Kelly C (2010) Analysing wellness tourism provision: a retreat operators’ study. J Hosp Tour Manag 17:108–116. https://doi.org/10.1375/jhtm.17.1.108

Kotler P, Bowen JT, Makens JC, Baloglu S (2017) Marketing for hospitality and tourism. Pearson, Boston

Kumar A (2019) Wellness tourism: taking a step forward. retrieved from travel trends today: https://www.traveltrendstoday.in/news/india-tourism/item/7482-wellness-tourism-taking-a-step-forward.

Kumari J (2017) 15 Ayurveda resorts in Kerala for every kind of traveller. Condé Nast Traveller. Retrieved from https://www.cntraveller.in/story/15-ayurvedic-resorts-in-kerala-to-help-you-heal/.

Mason P (2019) Tourism impacts, planning and management. Routledge, London

McFadden D (1974) Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behaviour. In: Zarembka P (ed) Frontiers in econometrics. Academic Press, New York, pp 105–142

Medina-Muñoz DR, Medina-Muñoz RD (2014) The attractiveness of wellness destinations: an importance-performance-satisfaction approach. Int J Tour Res 16(6):521–533

Miller MC, Gransberg D (2017) Measuring users’ impact to support economic growth through Transportation Asset Management planning. Int J Public Pol 13:323–336. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJPP.2017.087875

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (2014) State-wise distribution of AYUSH (Ayurveda, Yoga, Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha, Sowa-Rigpa and Homoeopathy), hospitals, beds and dispensaries. Retrieved from data.gov.in: https://data.gov.in/catalog/state-wise-distribution-ayush-ayurveda-yoga-naturopathy-unani-siddha-sowa-rigpa-and?filters%5Bfield_catalog_reference%5D=91751&format=json&offset=0&limit=6&sort%5Bcreated%5D=desc.

Mirosa M, Liu Y, Bremer P (2020) Determining how Chinese consumers that purchase western food products prioritise food safety cues: a conjoint study on adult milk powder. J Food pro Mark 26(5):358–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/10454446.2020.1782796

Mondal MR (2020) Tourism as a livelihood development strategy: a study of Tarapith Temple Town, West Bengal. Asia-Pacific J Reg Sci 4:795–807. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41685-020-00164-6

Morrison AM (2019) Marketing and managing tourism destinations. Routledge, London.https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315178929

Moscardo G (2019) Rethinking the role and practice of destination community involvement in tourism planning. In: Andriotis K, Stylidis D, Weidenfeld A (eds) Tourism policy and planning implementation. Routledge, London

Moutinho L, Rita P, Curry B (1996) Expert systems in tourism marketing. Routledge, London

Munro A, King B, Polonsky MJ (2006) Stakeholder involvement in the public planning process—the case of the proposed twelve apostles visitor centre. J Hosp Tour Manag 13:97–107. https://doi.org/10.1375/jhtm.13.1.97

Page SJ, Connell J (2020) Tourism—a modern synthesis. Routledge, London

Page SJ, Hartwell H, Johns N et al (2017) Case study: wellness, tourism and small business development in a UK coastal resort: Public engagement in practice. Tour Manag 60:466–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.12.014

Parsad C, Chandra CP, Suman S (2019) A product feature prioritisation-based segmentation model of consumer market for health drinks. Int J Strat Dec Sci 10(2):70–83. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijsds.2019040104

Pike S (2021) Destination marketing: essentials. Taylor and Francis, London

Poorani A, Jiang N (2017) The branding of medical tourism in China: A snapshot using a strategic model analysis. In: DeMicco Frederick J (ed) Medical tourism and wellness: hospitality bridging healthcare (H2H). Apple Academic Press, New Jersey

Racherla P, Hu C, Hyun MY (2008) Exploring the role of innovative technologies in building a knowledge-based destination. Curr Issues Tour 11:407–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500802316022

Ramesh U, Kurian J (2012) A study to develop an advanced marketing strategy for wellness tourism in Kerala based on the prevailing scenario. Int J Multi Res 1:211–222

Ravichandran S, Suresh S (2010) Using wellness services to position and promote brand India. Int J Hosp Tour Adm 11:200–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/15256481003732873

Ravisankar K (2018) It’s time for a rebrand, Brand Kerala. p 7. Retrieved from https://issuu.com/brandkerala/docs/page1-58_2n.

Romão J, Machino K, Nijkamp P (2017) Assessment of wellness tourism development in Hokkaido: a multicriteria and strategic choice analysis. Asia Pacific J Reg Sci 1:265–290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41685-017-0042-4

Romão J, Machino K, Nijkamp P (2018) Integrative diversification of wellness tourism services in rural areas—an operational framework model applied to east Hokkaido (Japan). Asia Pacific J Tour Res 23:734–746. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2018.1488752

Ruiz-Real JL, Uribe-Toril J, Gázquez-Abad JC (2020) Destination branding: opportunities and new challenges. J Destin Mark Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100453

Sigala M, Marinidis D (2012) E-Democracy and web 2.0: a framework enabling DMOs to engage stakeholders in collaborative destination management. Tour Anal 17:105–120. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354212X13330406124052

Smith MK, Diekmann A (2017) Tourism and wellbeing. Ann Tour Res 66:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.05.006

Souiden N, Ladhari R, Chiadmi NE (2017) Destination personality and destination image. J Hosp Tour Man 32:54–70

Steward JR (2012) Moral economies and commercial imperatives: Food, diets and spas in central Europe: 1800–1914. J Tour Hist 4:181–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/1755182X.2012.697487

The Hindu (2019) Ayurveda Centres in Kerala Tourism’s Quality Net. Retrieved on 23 July 2019 www.thehindu.com/news/national/kerala/ayurveda-centres-in-kerala-tourisms-quality-net/article28693004.ece.

Thornton, G (2015) Transformative evolution: from ‘wellness’ to ‘medical wellness’ tourism in Kerala. New Delhi: Grant Thornton India. Retrieved from http://gtw3.grantthornton.in/assets/Grant_Thornton_report-Transformative_Evolution.pdf.

Walton JK (2012) Health, sociability, politics and culture. Spas in history, spas and history: an overview. J Tour Hist 4:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/1755182x.2012.671372

Whiting RH, Hansen P, Sen A (2017) A tool for measuring SMEs’ reputation, engagement and goodwill: a New Zealand exploratory, Analysin. J Intellect Cap 18:217–240

Yeung O, Johnston K (2018) Global wellness economy monitor. Global Wellness Institute, Miami

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our utmost gratitude to Professor Paul Hansen, University of Otago and Franz Ombler, Co-founder of 1000minds for providing academic scholarship to access to the use of 1000Minds software.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Romão, J., Seal, P.P., Hansen, P. et al. Stakeholder-based conjoint analysis for branding wellness tourism in Kerala, India. Asia-Pac J Reg Sci 6, 91–111 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41685-021-00218-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41685-021-00218-3