Abstract

Background

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) has been associated with great healthcare and non-healthcare resource consumption. The aim of this study was to estimate the burden of AD in Spain according to disease severity from a societal perspective.

Methods

A self-administered questionnaire was designed by the researchers and completed by the informal caregivers of patients with AD, reporting data on themselves as caregivers and on the AD patients for whom they care. The patients’ sociodemographic and clinical data, their healthcare and non-healthcare resource consumption in the previous 12 months, and the impact of the disease on labor productivity were compiled. Data collected on informal caregivers included sociodemographic data and the impact of caring for a person with AD on their quality of life and labor productivity. Costs were estimated by multiplying the number of consumed resources by their unit prices. The cost of informal care was assessed using the proxy good method, and labor productivity losses were estimated using the human capital method. Costs were estimated by disease severity and are presented per patient per year in 2021 euros (€).

Results

The study sample comprised 171 patients with AD aged 79.1 ± 7.4 years; 68.8% were female, time from diagnosis was 5.8 ± 4.1 years, diagnosis delay was 1.8 ± 2.3 years, and the mean Cumulative Illness Rating Scale–Geriatric (CIRS-G) total was score 8.2 ± 6.0. According to disease severity, 14% had mild cognitive impairment or mild AD, 43.9% moderate AD, and 42.1% severe AD. The average annual cost per patient was €42,336.4 in the most conservative scenario. The greatest proportion of this cost was attributed to direct non-healthcare costs (86%, €36,364.8), followed by direct healthcare costs (8.6%, €3647.1), social care costs (4.6%, €1957.1), and labor productivity losses (less than 1%, €367.4). Informal care was the highest cost item, representing 80% of direct non-healthcare costs and 69% of the total cost. The total direct non-healthcare cost and total cost were significantly higher in moderate to severe disease severities, compared to milder disease severity.

Conclusions

AD poses a substantial burden on informal caregivers, the national healthcare system, and society at large. Early diagnosis and treatment to prevent disease progression could reduce this economic impact.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The average annual cost per patient with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in Spain is €42,336 in the most conservative scenario. |

Informal care represents the largest proportion of the total costs associated with AD. |

The total direct non-healthcare cost and total cost are significantly higher in moderate to severe disease severities, compared to milder disease severity. |

1 Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by short-term memory loss and a cognitive impairment in language, visuospatial, and executive functions [1]. The severity of cognitive deterioration varies according to the phase of the disease, progressing from no evident symptomatology (preclinical phase), through subjective and mild impairment, until reaching dementia [2]. Patients with mild cognitive impairment usually maintain their functional independence, while dementia is marked by a loss of independence and impaired daily functioning [1, 2]. Time to progression is highly variable between patients and depends on several factors [3]. While 10-year life expectancy has been reported for AD [4], patients can live with the disease for up to 20 years [5]. Both environmental and genetic factors contribute to the onset of AD, with age being the most important risk factor [6]. Other potentially modifiable risk factors include metabolic comorbidities (such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, obesity), smoking, depression, physical inactivity, and low educational level [1, 2].

Currently, AD is considered the leading cause of dementia worldwide, accounting for 75% of the overall cases [2, 7]. In a meta-analysis of the prevalence of AD in Europe and the United States (US), the prevalence of AD was estimated to range between 3.0 and 7.0% [8]. In Spain, the prevalence was estimated to range between 2.4 and 6.9% in people aged 65 or over [8, 9], and it is likely to increase in the coming years due to the progressive aging of the population [10]. The estimated overall age-adjusted incidence rate of AD in Spain was estimated at 4.5 to 5.5 cases per 1000 person-years [11], which applied to official population data [12] would represent between 210,000 and 260,000 people in Spain.

Some studies in Spain have estimated the total annual cost per AD patient at €28,198 (2001 €) [13] and up to €64,354 (2013 €) [14]. In addition, monthly costs per AD patient in Spain (2013 €) have been estimated at €1514 (mild AD), €2082 (moderate AD), and €2818 (severe AD) [15]. The high economic impact of AD has also been reported for other European countries, with 18-month costs per patient estimated at €33,339 in France, €38,197 in Germany, and €37,899 in the UK [16]. In Italy, monthly costs per AD patient (2013 €) range from €1850 to €2728 depending on disease severity [17]. Moreover, in the US, the monthly cost per patient with early stage AD has been estimated at $4243 (2017 US dollars) [18].

AD imposes a significant social, psychological, and economic burden for patients, their families, and society [2]. The loss of autonomy is a life-altering factor, not only for the patients but also for those around them. AD patients often require formal and informal care, the latter being generally provided by family members [13, 14, 19]. Informal caregivers can spend more than 10 h/day caring for AD patients [20]. It is not surprising that AD carries heavy consequences on the caregiver´s quality of life and health [21,22,23]. Factors that have been associated with an increased caregiver burden include being the sole carer, spending more daily hours on caring activities, and living with the patient [24]. Moreover, the work and professional lives of caregivers can also be jeopardized by their role as carers [25]. In Spain, state-funded social care for AD patients is available in the form of outpatient services, mainly day-care centers and nursing homes with mid-stay and long-stay units [26]. Although access to these services is not based on income, access to them is limited and in need of reinforcement and further development [27].

The social and economic burden of AD is naturally related to the severity of the disease, with more severe patients implying higher costs [28, 29]. To date, few studies have explored the economic burden of AD in Spain and, to our knowledge, only two have stratified the costs by disease severity [13, 14]. Cost data from these previous studies are outdated. More research and more recent evidence are therefore needed. The main objective of this study was to estimate the economic burden of AD in adult patients in Spain from a societal perspective, considering direct healthcare costs (DHC), direct non-healthcare costs (DNHC), and indirect costs (IC), differentiating among stages of disease severity.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design and Participant Population

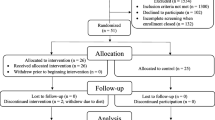

A retrospective cross-sectional observational study was carried out through an online self-administered questionnaire aimed at informal caregivers (i.e., a relative or close friend who takes non-professional care of the patient without payment). The link to access this questionnaire was distributed by the main cluster of AD patient associations in Spain (Confederación Española de Alzheimer—CEAFA). Data were collected between December 2021 and February 2022.

Inclusion criteria were related to the characteristics of the AD patients being cared for: having an AD diagnosis at least 12 months before the survey completion date, being 18 years old or older, and residing in Spain. A subgroup analysis according to disease severity was done. Disease severity was indicated by informal caregivers according to the last clinical report from the specialist. Disease severity was broken down into four categories according to the commonly used disease classification stages in clinical practice in Spain [2, 26, 30]: mild cognitive impairment, mild dementia, moderate dementia, and severe dementia. For statistical analysis purposes, the first two categories were combined to obtain a larger subsample of AD patients (this merged category will be referred to as the “mild stage”). Thus, subgroup analyses are presented according to three stages of AD: mild (mild forgetfulness, problems with concentration), moderate (important memory loss, help needed for self-care, disoriented in time and often in space), and severe (severe memory loss, loss of autonomy outside of home, significant help needed for self-care).

A convenience sampling method was used. CEAFA distributed the link to access the online survey among their members, and those informal caregivers who were willing to participate and met the inclusion criteria, completed the survey via the link provided. Although this non-random sample may not be fully representative of all AD patients living in Spain (sampling error of 7.5% for a confidence level of 95%), the patients included lived all across the country and, more specifically, in 14 out of the 19 autonomous communities/cities of Spain. Including patients from different regions acknowledges regional healthcare and social differences and their impact on AD management. Those informal caregivers who voluntarily agreed to participate were included in the study. The present study conforms with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study did not require approval by any ethics committee as according to the Spanish law (“Ley 14/2007, de 3 de julio, de Investigación biomédica”) research projects carried out on human beings or their biological material have to be approved by a research ethics committee, excluding observational studies where patient treatment or intervention is not modified. A multidisciplinary advisory committee (comprising a clinical expert in dementia, a senior health economist, and a representative of CEAFA) critically revised the study methodology and results.

2.2 Variables

The questionnaire was specifically designed to gather information on AD patients and their informal caregivers, based on literature research. The study was reported to Farmaindustria (the National Trade Association of the pharmaceutical industry) following their best practice standards, and CEAFA critically revised and validated the questionnaire through pilot testing among a small sample of informal caregivers of AD patients. Information on AD patients included sociodemographic and clinical data, information on diagnosis, healthcare, social care, and non-healthcare resource consumption in the previous 12 months, and labor productivity losses due to the disease. Informal caregivers’ sociodemographic data, and labor productivity losses due to AD patient care were also recorded (see the full questionnaire in the electronic supplementary material, Supplementary information 1).

In addition, three validated instruments were included to measure patients´ impairment and performance of daily activities, and caregivers´ burden. The Cumulative Illness Rating Scale–Geriatric (CIRS-G) is used for assessing physical impairment in several domains; it contains 14 items rated from 0 (no problem) to 4 (extremely severe problem) [31]. The Katz Index was developed to measure performance of activities of daily living, and it is used to obtain an indication of the degree of dependency/independency of the person in six domains, which are scored in three degrees (independence, partial dependence, and complete dependence) [32]. The Caregiver Strain Index measures the burden of caregivers and is a 13-item questionnaire, with answers being “yes” (1 point) or “no” (0 points) [33]. The score is determined by adding up the “yes” answers, with a score of 7 or greater indicating high levels of stress.

2.3 Costs

Costs were estimated from a societal perspective and included direct costs (i.e., healthcare, non-healthcare, and social care-related costs) and IC (i.e., costs incurred from the cessation or reduction of work productivity due to the disease) related to the 12 months before the survey completion date.

DHC, direct social care costs (DSCC), either privately or publicly financed, DNHC, and IC related to the patients’ labor productivity losses were estimated. The sum of these categories represented the total costs (TC). All these costs are reported per patient with AD per year. The cost of diagnosis (associated with clinical visits and tests leading to diagnosis) is not included in the TC as it is a one-time cost that occurred more than 12 months from survey completion, and as such, is reported separately as additional information.

The reference year for the costs was 2021, except for the cost of medication, which was obtained from the Consejo General de Colegios Oficiales de Farmacéuticos drug database [34] (consultation date: February 17, 2022). Costs reported with a reference year before 2021 were updated using the consumer price index (CPI), except for those reported in official bulletins of the Spanish autonomous communities, which were updated following the indications provided in each bulletin.

Diagnosis costs were estimated by multiplying medical visits and tests by the corresponding unit price (Table A1 in the Supplementary information 2). Similarly, DHC were estimated by multiplying the resource consumed by its corresponding unit price (Table A1 in Supplementary information 2), except for the cost of pharmacological treatment. The latter was obtained by multiplying the price per milligram of each active ingredient [34] by the recommended average daily dose according to the World Health Organization [35], and by the number of days that the patient had taken the medication in the previous 12 months (assuming 30.44 days per month). Moreover, the minimum cost per milligram was used to match the recommended daily dose (Table A2 in Supplementary information 2). Recommended doses can be found in Table A3 in Supplementary information 2.

To estimate DSCC, different methods were used depending on the funding received. If the costs were completely covered by the public system, the number of months that the patient had used each resource because of AD in the last 12 months was multiplied by the monthly price of that resource [36] (Table A4 in Supplementary information 2). If the costs were partially or completely covered by the patient and/or family, the monthly cost reported in the questionnaire was multiplied by the months that the resource had been used.

Within the DNHC category, the cost of informal care was estimated using the proxy good method. Accordingly, the time spent on family care was quantified by applying the cost that would have been incurred had a caregiver been hired during that time. Two different scenarios have been estimated using two different financial proxies: on the one hand, the hourly wage of an unskilled worker established for domestic employees [37], and on the other, the average hourly cost of a home help service (Table A5 in Supplementary information 2). Thereafter, these hourly costs were multiplied by the number of weekly hours of informal care reported in the questionnaire (including both the main and other caregivers) and by the number of months that the patient received such care, assuming 4.33 weeks per month. The number of hours of caregiving per day was censored to a maximum of 16 h, considering the remaining 8 h of the day being used for basic aspects of the informal caregiver’s life (rest, food, self-care), as a conservative criterion [19]. Scenario 1 and scenario 2 represent costs estimated using the lowest (household employee) and highest financial proxy (home help service), respectively.

Furthermore, 12-month expenditures reported directly by informal caregivers (i.e., professional care, housing adaptation, orthopedic devices, and other out-of-pocket expenses) were included as DNHC. Self-reported expenditures in less than 12 months were extrapolated to yearly expenditures. Finally, regarding transportation, the patients’ expenditure on commuting to health centers was calculated as follows:

-

In the case of having used a private vehicle, cab, or public transport: If the cost was covered by the patient and/or family, this was estimated using the cost per complete trip reported in the questionnaire, multiplied by the number of trips made; if the cost was covered by the public system, a price of €0.19/km was used [38], multiplied by the distance traveled per trip (km) and by the number of trips.

-

In the case of having used an ambulance (non-urgent transport): If the cost was covered by the patient and/or family, this was estimated using the cost per complete trip reported in the questionnaire, multiplied by the number of trips made; if the cost was covered by the public system, a price of €0.69/km was used [39], multiplied by the distance traveled per trip (km) and by the number of trips.

Regarding commuting of informal caregivers to visit the patient, costs were estimated following the same procedure, yet multiplied by 12, as only monthly commutes were reported in the questionnaire.

IC were estimated using the human capital method, through lost or non-earned wages because of AD. The earnings lost by the working patients due to previous sick leave or leave of absence associated with the disease were estimated as the average annual wage per worker according to sex and age range [40], proportional to the reported months in such a situation within the previous 12 months. Moreover, the earnings lost by the working patients due to reduced working hours or recurrent days of absence associated with AD were estimated by assigning the national average cost per normal working hour according to sex and type of work (employed or freelance) to the number of hours reduced/lost [41], considering the average working hours per day according to sex and type of work [42] (Table A6 in Supplementary information 2). In addition, the earnings lost by the working patients due to occasional hours of absence because of AD were estimated by assigning the national average cost per normal working hour according to sex and type of work to the number of hours lost according to sex and type of work [41]. Finally, earnings lost by patients on temporary/permanent leave or early retirement were estimated as the average annual earnings per worker according to sex and age range [40], proportional to the reported months in such a situation within the previous 12 months. All unit prices related to labor productivity losses can be found in Table A7 in Supplementary information 2.

TC represent the sum of DHC, DSCC, DNHC, and IC associated with the patients’ labor productivity losses. Though common, informal caregivers’ work productivity loss was excluded from the TC as it would duplicate the cost associated with informal care.

The cost per patient and year is the average cost that a patient with AD places on both the Spanish National Health System and society at large over 1 year.

2.4 Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for continuous variables, and absolute frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Nonparametric techniques were used to compare groups (Chi-square, Mann-Whitney U test, and Kruskal-Wallis test) due to the nature of the data. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A log link generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) assuming a gamma distribution of costs was applied to estimate predictors of DHC and DNHC, and TC. As DSCC were not suitable for this distribution (due to a high presence of zero values), a two-part model with a logit in the first part and ordinary least squares (OLS) with logged dependent variable in the second part was used. Predictors for IC were not estimated as it was a residual cost among AD patients. Covariates included were sex, age, place of residence of the patients (on their own, with the informal caregiver, or in a nursing home), CIRS-G total score, years from diagnosis, the Caregiver Strain Index, and disease severity.

Outliers were previously identified and excluded from analysis to get more robust results and better model performance. Data analysis was performed with the statistical software IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 23 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

3 Results

A total of 31 outliers were identified and excluded from the analyses. The final sample comprised 171 AD patients that met the inclusion criteria. Overall, 14.0% of the patients were in the mild stage of AD, 43.9% in the moderate stage, and 42.1% in the severe stage. Table 1 shows the characteristics of patients and informal caregivers for the total sample according to disease severity.

The cost of diagnosis per patient with AD amounted to €1111.8 ± 774.0. In scenario 1, the annual TC per patient with AD amounted to €42,336.4. The greatest proportion of the TC was attributed to DNHC, accounting for 86% (€36,364.8), followed by DHC with 8.6% (€3647.1), DSCC with 4.6% (€1957.1), and IC accounting for less than 1% of the TC (€367.4). Moreover, in scenario 2, the annual TC per patient with AD amounted to €70,445.1. In scenario 2 (similarly to scenario 1), the greatest proportion of the TC was attributed to DNHC, accounting for 92% (€64,473.5), followed by DHC with 5.2% (€3647.1), DSCC with 2.8% (€1957.1), and IC accounting for less than 1% of the TC (€367.4). Table 2 shows the total annual cost per patient for the entire sample and according to the category of costs.

Table 3 shows the total annual costs per patient according to AD severity and category of costs. Overall, costs show a tendency to increase with disease severity. Specifically, significant differences were observed for DNHC and TC between mild and moderate, and mild and severe stages (p < 0.01). No significant differences were observed between disease severity stages regarding the cost of diagnosis, DHC, or DSCC.

3.1 Multivariate Analysis

Table 4 shows the results of the adjusted multivariate analysis. Model 1 showed that sex of the patient, CIRS-G total score, and the Caregiver Strain Index were predictors of DHC, with male sex and higher scores in the CIRS-G scale and the Caregiver Strain Index being related to higher DHC (p < 0.05). No significant predictors of DSCC were found in model 2. Finally, models 3 and 4 indicated that moderate and severe disease stages and higher scores in the Caregiver Strain Index significantly predicted higher DNHC and TC (p < 0.05).

4 Discussion

The present study estimated the economic burden of AD in adult patients in Spain according to disease severity stage. Results show that the average annual cost per patient with AD ranges between €42,336.4 (scenario 1) and €70,445.1 (scenario 2). The greatest proportion of the cost is attributed to DNHC, ranging between €36,364.8 (scenario 1) and €64,473.5 (scenario 2), followed by DHC (€3647.1), DSCC (€1957.1), and IC (€367.4). Taking AD severity stage into account, the costs associated with moderate and severe stages are greater than those associated with milder stages.

The total annual costs estimated in the present study are similar to those reported in recent studies in Spain [13, 14]. In those studies, DNHC (mainly informal care) also accounted for the greatest proportion of TC. Regarding informal care, Darbà et al. (2015) estimated an average cost per patient of €32,177.3 for a 6-month period, using the cost per hour of a professional caregiver (€15.71) as a proxy to calculate the cost of informal care. Extrapolated to 1 year, informal care estimated by this study closely resembles that of scenario 2 in the present study, in which the average cost per hour of home help service (€14.81) was used as a proxy of the cost per hour of informal care. Similarly, Lopez-Bastida et al. (2006) reported a DNHC of €28,198 per patient, which resembles that of scenario 1 in the present study. In both cases, the hourly rate per hour of unskilled work established for domestic employees (€7.55/h) was used as a proxy for the cost per hour of informal care. Regarding DHC and IC, the results of our study are in line with those of Darbà et al. and Lopez-Bastida et al., with IC having the lowest weight on the TC [13, 14].

High AD costs have also been reported for other European countries. Reed et al. (2017) explored 18-month resource utilization and differences in costs of AD between France (€33,339), Germany (€38,197), and the UK (€37,899) [16]. In line with our results, informal care contributed the most (between 54% and 65%) to the TC in these three countries. Differences in costs among these countries were attributed to different unit costs as well as variations in resource consumption and availability associated with each specific healthcare system. Regarding unit costs, those applied to informal care in the UK were lower than in Germany and France. Moreover, regarding resource consumption and availability, French patients used more community care services and, thus, caregivers spent less time on informal care. In contrast, German patients were less likely to be institutionalized or use temporary accommodation. Therefore, the availability of community care services influences the time that caregivers spend on informal care, which in turn has a direct impact on the TC of AD. In our study, costs are higher than those estimated for these three European countries, which could be explained by the cost of informal care, as DNHC contributed 86% (scenario 1) to 92% (scenario 2) to TC and informal care costs were the largest proportion of DNHC. Similar to these findings, in the US, the greatest part of the cost associated with mild AD was explained by informal caregiver costs (45%) [18].

The large contribution of informal care costs to AD TC has been broadly acknowledged in the literature [15,16,17,18, 43, 44]. It has been estimated that in Spain approximately 80% of patients with AD are cared for by their families [9, 19]; moreover, it is suggested that these families cover 88% of the TC of the disease [45]. A study found that, on average, informal caregivers spend 80 h/week in caregiving activities, with disease severity and level of dependency being strongly correlated with the number of caregiving hours [19]. Accordingly, in our study 84% of patients live with the caregiver and caregivers spend an average of 71 h/week caring for the patient. This leads to an undeniable high psychological and economic burden on the caregivers and families. Indeed, in this study, 77% of the caregivers reported a high strain and workload involved in the care provided to the patients. The overload on the families is influenced by factors such as the presence of behavioral disorders and functional disruption in the patients as well as the lack of social support for the caregivers [9].

The results of this study show that the costs of AD increase with disease progression. More specifically, the annual TC associated with moderate (€42,315.9 [scenario 1]; €72,676.9 [scenario 2]) and severe stages of AD (€47,894.6 [scenario 1]; €77,597.2 [scenario 2]) are significantly higher compared with the mild stage (€25,725.8 [scenario 1]; €42,014.2 [scenario 2]) (p < 0.01). In line with the results of this study, several studies have found that the costs associated with AD are higher in more severe stages of the disease [13,14,15, 17, 43, 46, 47]. A literature review study among European countries shows that in general, despite methodological differences among the studies (inclusion criteria, method of follow-up or cost items, among others), there is a strong association between costs of care and disease severity, with costs being higher for more severe stages of the disease [46]. Other studies have shown that this is also the case in Spain [13,14,15, 47]. Results from our multivariate analysis are in line with these findings, as moderate and severe disease stages, along with greater caregiver burden, are associated with higher costs. Patients at an advanced stage of disease have a lower ability to perform activities of daily living [48]. It has been found that greater impairments in activities of daily living are associated with greater informal caregiving time and higher AD costs [48]. These associations shed light upon the differences in costs depending on the severity of the disease. In this line, slowing disease progression seems to be a way to reduce social and economic burden associated with AD.

Although annual TC differ among disease stages, no statistically significant differences are found for DHC specifically. Evidence from other studies in Spain is mixed, with some showing significant differences in DHC among disease stages [14], while others state no differences [15, 47]. In this study, DHC represent a relatively small proportion of the total annual costs (8.6% [scenario 1]; 5.2% [scenario 2]); similarly, in these other studies, DHC stay low in proportion to the TC [14, 15, 47].

A challenge of AD burden studies is the difficulty of recruiting patients within the mild severity stage, due to the high rates of underdiagnosis. A study performed on the Spanish population found that 70% of patients with dementia had not been previously diagnosed by healthcare services, especially those patients with mild dementia [49]. Moreover, it has been observed that at the time of the diagnosis, 64% of Spanish patients showed scores of moderate AD (Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE] score 10–20) and 6% showed scores of advanced AD (MMSE < 10) [30]. The patients in our study had on average 1.8 ± 2.3 years of diagnosis delay, that is, the time elapsed between first symptoms experienced and diagnosis. Similarly, a previous study has reported an average diagnosis delay of 28.4 ± 21.3 months [30]. It is important that healthcare systems prioritize the early detection and treatment of AD to prevent disease progression. In turn, this would have an impact on health outcomes, the quality of life of patients and their families, and society at large.

The current Spanish national strategy for AD and other dementias places early diagnosis as a primary objective. Lines of action include an opportunistic screening in primary care settings, training health professionals for the detection of early disease signs and symptoms, development and implementation of protocols for up-to-date diagnostic assessment, and streamlining coordination between healthcare levels to reduce waiting times, among others [27]. In addition, and considering the high strain of AD on the caregivers, efforts should also be made to prevent disease progression. Apart from the need of innovative pharmacological solutions, non-pharmacological alternatives such as cognitive stimulation therapies should also be considered. One of the goals of the mentioned Spanish national strategy is to increase the rate of patients receiving these types of therapies [27]. Healthcare professionals recognize the benefits of cognitive stimulation, including improvements in the quality of life of AD patients and caregivers [50]. However, access to these options is currently very limited, and there is significant misinformation among healthcare professionals, patients, and families [27]. Some data suggest that 36% of caregivers are unaware of memory maintenance workshops or programs, and for 15%, these are not available in their area [50].

One of the main strengths of the present study is the classification of patients according to AD severity stage, providing a greater understanding of how disease-related costs vary according to disease progression. Moreover, a wide range of resources was considered to estimate the costs associated with the disease (i.e., healthcare, social care, non-healthcare, and labor productivity losses). Finally, data collection was performed jointly with CEAFA, allowing the inclusion of patients and informal caregivers from different regions in Spain and contributing to obtaining a more representative sample of the Spanish population. Moreover, CEAFA actively provides training and information to its members, which contributes to greater health literacy and, therefore, greater validity of the data provided by the caregivers in this study.

Some limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of the present study. The estimates of resource consumption over the previous 12 months were based on data collected from a questionnaire completed by proxy informants (i.e., informal caregivers). Consequently, results may carry a recall and/or question misinterpretation bias; however, this method is commonly used in burden studies and, more specifically, in AD socioeconomic impact studies [13,14,15]. Moreover, when comparing responses between patients and caregivers, several studies have shown that the latter are capable of reporting valid healthcare information on the patient [51,52,53]. Similarly, disease severity was indicated by the caregivers based upon the last clinical report, which can also be susceptible to recall bias. Moreover, the estimation of disease severity can be confounded by the fact that there is a lack of a standard staging system used in clinical practice. In addition, the sample of the present study is relatively small, with a sampling error of 7.5%. Consequently, the survey results may not be fully representative of all AD patients in Spain and should be interpreted (and used) with caution. Nevertheless, information was collected from most regions in Spain, accounting for healthcare and social variability between regions. Moreover, a low proportion of patients in the sample had a mild disease severity. The overall average cost per patient could be potentially inflated given that most of the patients included in the study had moderate and severe disease stages. However, it is not uncommon in AD studies to have a lower proportion of participants with mild disease severity, considering the underdiagnosis of AD and the difficulty of finding patients with mild symptoms, as they do not frequently join patient associations. Nevertheless, statistical power was increased by combining patients with mild cognitive impairment and those in the mild AD severity stage.

The present study highlights the importance of understanding the economic burden of AD according to the type of cost and disease severity. Specifically, informal care represents the largest proportion of the TC associated with AD. Understanding the burden of AD is not only being aware of its social and economic impact from different perspectives, but visualizing potential benefits that could arise from preventing disease progression, hence, improving early diagnosis and treatment. In addition, this may further contribute to the design of equitable and efficient AD prevention and management policies.

References

Knopman DS, Amieva H, Petersen RC, Chételat G, Holtzman DM, Hyman BT, et al. Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers [Internet]. 2021 May 13 [cited 2022 Jun 30];7(33). https://www.nature.com/articles/s41572-021-00269-y

Manzano MS, Fortea J Villarejo, Alberto, Sánchez del Valle R. Guía oficial de práctica clínica en demencias. 2018. (Guías diagnósticas y terapéuticas de la Sociedad Española de Neurología).

Musicco M, Palmer K, Salamone G, Lupo F, Perri R, Mosti S, et al. Predictors of progression of cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease: the role of vascular and sociodemographic factors. J Neurol. 2009;256(8):1288.

Dementia Care Central. Stages of Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Durations & Scales Used to Measure Progression: GDS, FAST & CDR [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2022 Mar 1]. https://www.dementiacarecentral.com/aboutdementia/facts/stages/

Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. 2020;16(3):391–460.

Sheppard O, Coleman M. Alzheimer’s Disease: Etiology, Neuropathology and Pathogenesis. In: Alzheimer’s Disease: Drug Discovery [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2022 Jul 4]. p. 1–21. https://doi.org/10.36255/exonpublications.alzheimersdisease.2020.ch1

Qiu C, Kivipelto M, von Strauss E. Epidemiology of Alzheimer’s disease: occurrence, determinants, and strategies toward intervention. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2009;11(2):111–28.

Takizawa C, Thompson PL, van Walsem A, Faure C, Maier WC. Epidemiological and Economic Burden of Alzheimer’s Disease: a Systematic Literature Review of Data across Europe and the United States of America. JAD. 2014;43(4):1271–84.

Villarejo Galende A, Eimil Ortiz M, Llamas Velasco S, Llanero Luque M, López de Silanes de Miguel C, Prieto Jurczynska C. Report by the Spanish Foundation of the Brain on the social impact of Alzheimer disease and other types of dementia. Neurologia (Engl Ed). 2021;36(1):39–49.

Tola-Arribas MA, Yugueros MI, Garea MJ, Ortega-Valín F, Cerón-Fernández A, Fernández-Malvido B, et al. Prevalence of Dementia and Subtypes in Valladolid, Northwestern Spain: The DEMINVALL Study. Ikram MA, editor. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10): e77688.

Andreu-Reinón ME, Huerta JM, Gavrila D, Amiano P, Mar J, Tainta M, et al. Incidence of Dementia and Associated Factors in the EPIC-Spain Dementia Cohort. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;78(2):543–55.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Población en España a 1 de Enero de 2021. [Internet]. INE. 2021 [cited 2022 Jan 11]. https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736176951&menu=ultiDatos&idp=1254735572981

Lopez-Bastida J, Serrano-Aguilar P, Perestelo-Perez L, Oliva-Moreno J. Social-economic costs and quality of life of Alzheimer disease in the Canary Islands, Spain. Neurology. 2006;67(12):2186–91.

Darbà J, Kaskens L, Lacey L. Relationship between global severity of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and costs of care in Spain; results from the co-dependence study in Spain. Eur J Health Econ. 2015;16(8):895–905.

Olazarán J, Agüera-Ortiz L, Argimón JM, Reed C, Ciudad A, Andrade P, et al. Costs and quality of life in community-dwelling patients with Alzheimer’s disease in Spain: results from the GERAS II observational study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2017;29(12):2081–93.

Reed C, Happich M, Argimon JM, Haro JM, Wimo A, Bruno G, et al. What Drives Country Differences in Cost of Alzheimer’s Disease? An Explanation from Resource Use in the GERAS Study. JAD. 2017;57(3):797–812.

Bruno G, Mancini M, Bruti G, Dell’Agnello G, Reed C. Costs and Resource Use Associated with Alzheimer’s Disease in Italy: Results from an Observational Study. J Prev Alz Dis. 2018;5(1):55–64.

Robinson RL, Rentz DM, Andrews JS, Zagar A, Kim Y, Bruemmer V, et al. Costs of Early Stage Alzheimer’s Disease in the United States: Cross-Sectional Analysis of a Prospective Cohort Study (GERAS-US). J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2020;75(2):437–50.

Peña-Longobardo LM, Oliva-Moreno J. Economic valuation and determinants of informal care to people with Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Health Econ. 2015;16(5):507–15.

Georges J, Jansen S, Jackson J, Meyrieux A, Sadowska A, Selmes M. Alzheimer’s disease in real life—the dementia carer’s survey. Int J Geriat Psychiatry. 2008;23(5):546–51.

Serrano-Aguilar PG, Lopez-Bastida J, Yanes-Lopez V. Impact on Health-Related Quality of Life and Perceived Burden of Informal Caregivers of Individuals with Alzheimer’s Disease. Neuroepidemiology. 2006;27(3):136–42.

Vérez Cotelo N, Andrés Rodríguez NF, Fornos Pérez JA, Andrés Iglesias JC, Ríos LM. Burden and associated pathologies in family caregivers of Alzheimer’s disease patients in Spain. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2015;13(2):521.

El-Hayek YH, Wiley RE, Khoury CP, Daya RP, Ballard C, Evans AR, et al. Tip of the Iceberg: Assessing the Global Socioeconomic Costs of Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias and Strategic Implications for Stakeholders. JAD. 2019;70(2):323–41.

Conde-Sala JL, Turró-Garriga O, Calvó-Perxas L, Vilalta-Franch J, Lopez-Pousa S, Garre-Olmo J. Three-Year Trajectories of Caregiver Burden in Alzheimer’s Disease. JAD. 2014;42(2):623–33.

Peña-Longobardo LM, Oliva-Moreno J. Caregiver Burden in Alzheimer’s Disease Patients in Spain. JAD. 2014;43(4):1293–302.

Grupo de trabajo de la GPC sobre la atención integral a las personas con enfermedad de Alzheimer y otras demencias. Guía de práctica clínica sobre la atención integral a las personas con enfermedad de Alzheimer y otras demencias [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2023 Jun 27]. https://scientiasalut.gencat.cat/handle/11351/1272

Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar Social. Plan Integral de Alzheimer y otras Demencias (2019–2023). Sanidad; 2019.

Gustavsson A, Brinck P, Bergvall N, Kolasa K, Wimo A, Winblad B, et al. Predictors of costs of care in Alzheimer’s disease: a multinational sample of 1222 patients. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2011;7(3):318–27.

Khandker RK, Ritchie CW, Black CM, Wood R, Jones E, Hu X, et al. Multi-National, Cross-Sectional Survey of Healthcare Resource Utilization in Patients with All Stages of Cognitive Impairment, Analyzed by Disease Severity, Country, and Geographical Region. JAD. 2020;75(4):1141–52.

Poveda J, Baquero M, González-Adalid GM. Estadio evolutivo de los pacientes con enfermedad de Alzheimer que acuden a la consulta especializada en España. Estudio EACE. Neurologia. 2013;28(8):477–87.

Rosas-Carrasco O, González-Flores E, Brito-Carrera AM, Vázquez-Valdez OE, Peschard-Sáenz E, Gutiérrez-Robledo LM, et al. Evaluación de la comorbilidad en el adulto mayor. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc. 2011;49(2):153–62.

Cabañero-Martínez MJ, Cabrero-García J, Richart-Martínez M, Muñoz-Mendoza CL. The Spanish versions of the Barthel index (BI) and the Katz index (KI) of activities of daily living (ADL): a structured review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;49(1):e77-84.

López Alonso S, Serrano M. Validación del Indice de Esfuerzo del Cuidador en la población española [Validation of the Caregiver Strain Index in Spanish population]. Enfermeria Comunitaria. 2005;1:12–7.

Consejo General de Colegios Oficiales de Farmacéuticos. Botplusweb.portalfarma.com. BOT Plus 2. Base de Datos de Medicamentos [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2022 Mar 1]. https://botplusweb.portalfarma.com/botplus.aspx

WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. Norwegian Institute of Public Health. ATC/DDD Index [Internet]. [cited 2022 Mar 1]. https://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/

Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Informe 2016: Las personas mayores en España. Datos estadísticos estatales y por comunidades autónomas. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad; 2017 p. 540.

España. Real Decreto 817/2021, de 28 de septiembre, por el que se fija el salario mínimo interprofesional para 2021 [Internet]. 2021. https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2021/09/29/pdfs/BOE-A-2021-15770.pdf

Agencia Tributaria. Manual práctico de Renta 2020. 2021;1466.

Mediana de las tarifas sanitarias oficiales de las Comunidades y Cuidades Autónomas, previa actualización de cada tarifa según las indicaciones del boletín regional correspondiente.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Encuesta Anual de Estructura Salarial - Año 2019. Resultados Nacionales y por Comunidades Autónomas. Ganancia media anual por trabajador. [Internet]. INE. 2019 [cited 2022 Feb 18]. https://ine.es/jaxiT3/Tabla.htm?t=28201&L=0

Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Encuesta Anual de Estructura Salarial—Año 2019. Resultados Nacionales y por Comunidades Autónomas. Ganancia por hora normal de trabajo. [Internet]. INE. 2019 [cited 2022 Feb 10]. https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Datos.htm?t=28205.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Encuesta de Población Activa. Número medio de horas efectivas semanales trabajadas por los ocupados que han trabajado por situación profesional, sexo y ocupación (empleo principal) [Internet]. INE. 2020 [cited 2022 Feb 18]. https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Datos.htm?t=4873

Wimo A, Reed CC, Dodel R, Belger M, Jones RW, Happich M, et al. The GERAS Study: A Prospective Observational Study of Costs and Resource Use in Community Dwellers with Alzheimer’s Disease in Three European Countries—Study Design and Baseline Findings. JAD. 2013;36(2):385–99.

Dodel R, Belger M, Reed C, Wimo A, Jones RW, Happich M, et al. Determinants of societal costs in Alzheimer’s disease: GERAS study baseline results. Alzheimer’s Dementia. 2015;11(8):933–45.

Coduras A, Rabasa I, Frank A, Bermejo-Pareja F, López-Pousa S, López-Arrieta JM, et al. Prospective one-year cost-of-illness study in a Cohort of Patients with Dementia of Alzheimer’s Disease Type in Spain: the ECO Study. JAD. 2010;19(2):601–15.

Jönsson L, Wimo A. The Cost of Dementia in Europe: a review of the evidence, and methodological considerations. Pharmacoeconomics. 2009;27(5):391–403.

López-Pousa S, Garre-Olmo J, Turon-Estrada A, Hernández F, Expósito I, Lozano-Gallego M, et al. Análisis de los costes de la enfermedad de Alzheimer en función del deterioro cognitivo y funcional. Med Clin. 2004;122(20):767–72.

Reed C, Belger M, Vellas B, Andrews JS, Argimon JM, Bruno G, et al. Identifying factors of activities of daily living important for cost and caregiver outcomes in Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2016;28(2):247–59.

Zunzunegui Pastor MV, Rodríguez-Laso A, Rodríguez-Laso A. Prevalencia de la incontinencia urinaria y factores asociados en varones y mujeres de más de 65 años. Atención Primaria. 2003;32(6):337–42.

Alvarez PML. Actitudes, dudas y conocimientos de los colectivos implicados en la atención del paciente con Alzheimer: resultados de la encuesta del proyecto kNOW Alzheimer. Farmacéuticos comunitarios. 2016;8(1):13–23.

Neumann PJ, Araki SS, Gutterman EM. The use of proxy respondents in studies of older adults: lessons, challenges, and opportunities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(12):1646–54.

Oczkowski C, O’Donnell M. Reliability of proxy respondents for patients with stroke: a systematic review. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2010;19(5):410–6.

Østbye T, Tyas S, Mcdowell I, Koval J. Reported activities of daily living: agreement between elderly subjects with and without dementia and their caregivers. Age Ageing. 1997;26(2):99–106.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Confederación Española de Alzheimer for its collaboration in this study, and the informal caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease who participated in the survey. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Guillermo García-Ribas (University Hospital Ramón y Cajal, Spain), María Dolores Almagro Cabrera (Confederación Española de Alzheimer, Spain), and Dr. Luz María Peña-Longobardo (University of Castilla-La Mancha, Spain) for their participation as experts on the advisory committee.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was funded by Biogen Spain S.L.U. The funder was not involved in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation of data, or the writing of this article.

Conflict of interest

LGM and RMF are employees of Biogen Spain S.L.U. and hold shares or stocks as part of their remuneration. ALA, PMH, and MM are employees of Vivactis Weber, a company that received fees from Biogen Spain S.L.U. to develop this study.

Ethics approval

The present study conforms with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study did not require approval by any ethics committee as according to Spanish law (“Ley 14/2007, de 3 de julio, de Investigación biomédica”) research projects carried out on human beings or their biological material have to be approved by a research ethics committee, excluding observational studies where patient treatment or intervention is not modified. The study was communicated to Farmaindustria (the National Trade Association of the pharmaceutical industry).

Consent to participate

According to Spanish law (“Ley 41/2002, de 14 de noviembre, básica reguladora de la autonomía del paciente y de derechos y obligaciones en materia de información y documentación clínica el consentimiento informado”), informed consent has to be signed only when the activity of the study can affect patient’s health status. Since our study is observational and patient data were obtained using an online anonymous survey, it was not necessary for caregivers to sign an informed consent in this study.

Consent for publication

By voluntarily completing the questionnaire, informal caregivers of Alzheimer´s disease patients gave their consent for the data to be used confidentially (only aggregated data are reported).

Availability of data

The datasets may be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code for data cleaning and analysis may be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author contributions

LGM, RMF, and MM participated in the conception and design of the study. ALA, PMH, and MM participated in the acquisition of data. All authors participated in the analysis and interpretation of data. ALA and MM wrote the draft of the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version to be published.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gómez Maldonado, L., de Mora-Figueroa, R., López-Angarita, A. et al. Cost of Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease in Spain According to Disease Severity. PharmacoEconomics Open 8, 103–114 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-023-00451-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-023-00451-w