Abstract

Background and Objective

Several novel methods have been suggested to extend a conventional value assessment to capture a more comprehensive perspective of value from a patient perspective. The objective of this research was to demonstrate a framework for implementing a combined qualitative and quantitative method to elicit and prioritize patient experience value elements in rare diseases. Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder was used as a case study.

Methods

The method for eliciting and prioritizing patient experience value elements involved a three-step process: (1) collecting potential patient experience value elements from existing literature sources followed by deliberation by a multi-stakeholder research team; (2) a pre-workshop webinar and survey to identify additional patient-reported value elements; and (3) a workshop to discuss, prioritize the value elements using a swing weighting method. Outcomes were prioritized value elements with normalized weights for patients considering a treatment for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder.

Results

A literature review and deliberation resulted in the following initial value elements: ability to reach important personal milestones, patient’s financial burden, value of hope/balance or timing of risks and benefits, Uncertainty about long-term benefits and safety of the treatment, Patient empowerment through therapeutic advancement and technology, Caregiver/family’s financial burden, patient experience related to treatment regimen, Therapeutic options, and Caregiver/family’s quality of life. Eight patients with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder participated in the case study. In the online survey, participants found the nine proposed patient experience value elements both understandable and important with no additions. During the workshop, ‘Uncertainty about long-term benefits and safety,’ ‘Patient experience related to treatment regimen,’ and ‘Patient’s financial burden’ were found to be the most important patient experience value elements, with a respective weight of 25%, 19.2%, and 14.4% (out of total 100%).

Conclusions

This case study provides a framework for eliciting and prioritizing patient experience value elements using direct patient input. Although elements/weights may differ by disease, and even in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder, additional research is needed, value frameworks, researchers, and manufacturers can use this practical method to generate patient experience value elements and evaluate their impact on treatment selection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

A conventional value assessment may not capture the full spectrum of value for patients. |

This paper describes a practical method to engage patients in eliciting and prioritizing patient experience value elements. |

A rare neurological disease, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder, was used as a case study. |

1 Introduction

The increasing public pressure about rising drug prices highlights the importance of assessing the value of health technologies. Two main questions are raised regarding the value of new healthcare technologies: (1) what value elements are important for different stakeholders, including patients, caregivers, healthcare professionals, and payers/insurance? (2) What is a fair price premium for the added value of new technologies? A common critique of conventional value assessment is the lack of formal representation of additional value elements beyond regulatory approval endpoints such as patient-centered and societal value elements [1]. Several alternative methods have been suggested to broaden a conventional value assessment in capturing a more complete perspective on value. In recent years, multiple value frameworks have been published or updated to capture a broader list of potential value elements [2,3,4,5]. Methods to include these additional value elements in value assessment applications are emerging and include an augmented cost-effectiveness analysis and a multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) [6,7,8,9,10,11].

Guidance documents suggest that multiple stakeholders, including payers/decision makers, healthcare providers, academic researchers, and patients and informal caregivers should be involved to elicit the relative importance of value elements as various stakeholders have different perspectives and decision contexts [12,13,14]. Different decision contexts may exacerbate information asymmetry, for example, decision makers may not be aware of patient experiences (PEx) related to different health technologies. According to the guidance of the US Food and Drug Administration, PEx data may be collected by any persons and are intended to provide information about PEx with a disease, or the related treatment [15]. While conventional value elements derived largely from regulatory approval studies (e.g., survival, safety) are included in value assessment applications and weighed by a multi-stakeholder group (where patients and their family caregivers are also represented) [16], the relative importance of subdomains within patient-centered value should be determined by patients and their families [17].

The dearth of PEx value elements in value assessment applications is even more apparent for therapies focused on treating patients with rare diseases. Many novel technologies for rare disease, such as cell and gene therapies, are approved based on limited evidence (e.g., single-arm studies, small sample sizes) at the regulatory approval stage compared to non-rare diseases [18, 19]. Further, novel treatments can raise significant affordability concerns, even in high-income countries. The combination of data gaps and affordability concerns can lead to significant uncertainty for both patients and payers. An example case of a rare disease where the recent approval of breakthrough treatments has limited evidence and may benefit from further data on patient insights is neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) [20,21,22]. Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder is a rare recurrent inflammatory disorder of the central nervous system that commonly presents with recurrent attacks of optic neuritis and transverse myelitis and affects approximately 0.5–4/100,000 patients globally, making the recruitment of patients for both pivotal clinical trials and post-marketing research a challenge [23]. Neurologic injury in NMOSD is often severe, leading to blindness and/or paralysis. As a result, its impact on patients and their families, as well as society, is substantial. However, the impact of NMOSD on patients and their families is not well documented and understood. To fill gaps in the NMOSD literature on PEx, we used common MCDA weighting methods to prioritize the multiple criteria that drive treatment decisions in NMOSD and compare the relative value of PEx value elements. Specifically, the objective of this research was to implement a combined qualitative and quantitative approach to elicit and prioritize the most important PEx value elements for patients with rare disease, with NMOSD as a case study.

2 Materials and Methods

Our method for eliciting and prioritizing PEx value elements involves a three-step process: (1) collecting potential PEx value elements from existing literature sources identified in a targeted literature review, and preparing an initial list of value elements through deliberation by the multi-stakeholder research team; (2) a pre-workshop webinar and surveys to identify additional PEx value elements; and (3) a workshop to prioritize the value elements using the swing weighting method commonly used in MCDA.

2.1 Patient Experience Value Element List Development

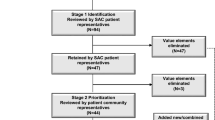

The sources of the initial PEx value element list are shown in Fig. 1. Identification of the initial list of value elements was based on two foundation works of US value frameworks: the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research Value Flower [2, 4] and the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review Value Assessment Framework [3]. These were extended with the results of two previously published studies: a systematic literature review that aimed to collect and analyze PEx value elements in published value frameworks [24] and an original research article applying mixed methods [5]. In the paper by Inotai et al. [24], based on the systematic literature review, a multidisciplinary research team developed five potential PEx value elements that were challenged, discussed, and approved by a panel of international payer experts. The original research article by dosReis et al. [5] aimed to identify patient-informed value elements that can be used to make value assessments more patient centered. This mixed-method study, including one-on-one discussions with patients from a diverse set of disease areas, identified 42 value elements organized into five domains: short-term and long-term effects of treatment, treatment access, cost, life impact, and social impact [5].

Initial selection and merging overlapping value elements from the four included papers to minimize redundancy was conducted iteratively through deliberations by a multi-stakeholder research team. The team included an NMOSD clinical expert (USA), a European Patients’ Academy on Therapeutic Innovation-trained [25] non-NMOSD patient expert (Hungary), and four academic researchers (from the USA and Hungary) experienced in value framework and MCDA development, in compliance with the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research MCDA Emerging Good Practices Task Force report’s principles [26]. Value elements were then flagged as (1) conventional value elements, (2) additional PEx value elements, and (3) additional societal value elements. Description and categorization of value elements were challenged by members of the research’s Steering Committee including internationally recognized health economists. Domains of PEx value elements (as described in this paper) were ranked and weighted by patients with NMOSD in a workshop, societal value elements will be ranked and weighted by a multi-stakeholder group in a future workshop.

2.2 Case Study Population

Patients with NMOSD (aged ≥ 18 years) who were positive for serum aquaporin-4 autoantibodies and fluent in English were recruited at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus (Protocol #21-3409). Participants received a gift card for their time and effort in the research.

2.3 Pre-workshop Webinar and Online Survey

The pre-workshop webinar, embedded to an anonymous online survey (using SurveyMonkey [27]), provided a concise lay-language audio-visual summary of the rationale of value assessment of health technologies and the study objective. The main research question—what do patients consider to be valuable when selecting a treatment for NMOSD?—was made explicit to participants of the case study at every stage of the process. The introduction was followed by short audio-visual explanations for each of the nine value elements, backed up with illustrations and real-life examples to ease understanding. After watching the short video for each value element, participants were asked to (1) rate the level of understanding of the value element on a five-level discrete rating scale (where 1 is “Very poor” and 5 is “Excellent”), with the opportunity to provide suggestions or comments for the concept or wording in a free text format, (2) rate the level of importance of each value element for themselves in their treatment decisions (where 1 is “Not important at all” and 5 is “Extremely important”), with the opportunity to add any personal experience on why it is, or why it is not important for people with NMOSD and their families. Finally, (3) participants were asked whether they think the list of value elements presented cover all important aspects of a new treatment for patients with NMOSD and their families, and if not, what might be missing. This step ensured that participants had the opportunity to propose additional value elements to extend findings from the literature. During the online survey, participants had the opportunity to pause and re-watch the prerecorded short videos on the value elements and navigate forward and backward among the questions. The pre-workshop webinar and online survey were pilot tested with two patients with NMOSD (who did not participate in the research) who were then interviewed to capture their impressions and suggestions. The voting exercises of the workshop were tested with university students for technical difficulties and feasibility.

2.4 Workshop

Participants were asked to contribute to the subsequent workshop only if they watched the pre-workshop webinar and completed the anonymous online survey. The workshop was held in a hybrid form, i.e., participation was possible face-to-face (onsite) or virtually (Zoom). The first part of the workshop was a group discussion, moderated by a trained facilitator, aimed to discuss (1) the objective of the research, (2) each value element (with a special focus on those items with a fair or worse understanding in the online survey), and (3) NMOSD-specific experience of participants gathered from the survey results and the comprehensiveness of the list of value elements.

The second part of the workshop was the ranking and weighting exercise, aiming to elicit participants’ preferences on the relative importance of the PEx value elements by anonymous voting through Mentimeter [28]. Mentimeter is an interactive polling software that allows users to develop advanced ranking and weighting exercises. To test participants’ understanding on voting questions and to make sure their Mentimeter was operating properly, both ranking and weighting exercises were preceded with similar questions on an everyday topic (i.e., important value elements of a good night’s sleep). To reduce the cognitive burden of the ranking exercise, participants were asked to select the three most important value elements in the first voting. These items (ranked by the entire group) were then removed from the list and participants were asked to repeat the voting and again select the next three most important value elements from the remainder of six. Finally, in a third voting, they were asked to rank the remainder value elements. Draws were acceptable voting outcomes.

The swing weighting method conducted is a commonly used preference elicitation technique in MCDA development to weight ranked value elements [29]. Participants were asked to indicate how much more a value element is important to them compared to the one ranked just below. First, a value element ranked #8 regarding its relative importance was compared to a value element ranked #9; then a value element ranked #7 was rated relative to #8, until the value element considered the most important #1 was compared to #2. In their votes for relative importance between each value element pairs, responders could select a value on a continuous scale between 0% (i.e., equally important) and + 50% (i.e., huge difference). Relative importance (mean of differences in percent) between element pairs were then converted to weights, summing up 100% for the total of nine value elements [9]. The final weights were then presented to the participants and discussed together with the moderator of the workshop.

3 Results

3.1 Participants

Eleven patients with NMOSD agreed to participate in the case study. Ten patients completed the pre-workshop survey and watched the webinar between 9 July and 19 July, 2021, and eight patients participated in the workshop on 22 July, 2021, allowing 3–13 days to consider the value elements. One participant could not take part in the ranking and weighting part of the workshop because of the accessibility issues of the voting platform (not accessible for the severely visually impaired). Out of eight participants who completed all steps of the case study, 50% were non-white and 25% of Hispanic origin. Over 35% had a time from diagnosis greater than 15 years, and 75% identified as female. The full description of the demographics and disease background of participants is provided in Table 1.

3.2 List of Value Elements

Table 2 describes the short descriptions and the Appendix in the Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM) shows the additional illustrations of the nine value elements presented to research participants both throughout the online survey and the workshop. In the pilot and during the online survey and the workshop, all responders confirmed the completeness of the list of value elements (i.e., no additional elements were proposed, and no recommendations were received regarding textual phrasing).

3.3 Understandability and Importance of Value Elements (Quantitative Results)

In the online survey, responders found the value elements understandable (range 4.3–4.7 out of a maximum 5), which was also reflected in their minimum scores not less than 3 (“Fair”) for any of the value elements. The online survey discovered the responders’ individual perception on the importance of each element on a 5-point scale, while the workshop revealed the relative importance of the value elements (i.e., the group’s mean percent difference) in the ranking and weighting exercise according to the group’s preference. Quantitative results are summarized in Table 3.

3.4 Participants’ Quotes on the Value Elements (Qualitative Results)

Participants were asked to reflect on each value element and their importance also in a free text format: first in the online survey, then in the group discussion part of the workshop. Table 4 contains the most illustrative participant quotes (edited for grammar, clarity, and brevity while maintaining intended content) associated with each value element from the online survey (S) and the workshop (W), respectively.

3.5 Additional Themes from the Workshop Discussion

In the online survey, workshop participants addressed some additional themes not directly related to the value elements discussed. Two participants stated their preferences for value elements are different at the time of the workshop as compared with earlier stages of the disease: (1) “Those were my three most important. Maybe it’ll change years down the line.” (2) “I’m looking at it through a filter of where I’m at today in terms of my disease progression and if there’s any clinical or subclinical concerns. Whereas prior, I would have considered the filter of where my values were at the point, where I was in an acute state or recently navigating the diagnosis. I don’t know but the value shift is very dynamic.” Participants also reflected on the significance of the relative importance of the value elements: “I think this has been great. Thinking back to attributes of each element and the magnitude of difference between them. I think it's always a false choice to choose one versus the other, but I don’t think I've ever thought about the space between my top choices.” For some patients, participating in the workshop offered new connections to other patients with NMOSD and emphasized the value of personal connections with peers who are having similar PEx.

4 Discussion

4.1 Ensuring Completeness of Value Elements

We applied multiple steps to ensure the completeness of the final list of value elements, including robust literature sources, multiple iterations with stakeholders (steering committee, pilot), and providing multiple opportunities for participants to revise the list of value elements or propose new elements while (1) completing the online survey (individual feedback) and (2) sharing their experiences in the workshop (group interaction). Consequently, in the online survey, we observed high scores on understandability (Table 3), relevant NMOSD-specific examples and, during the workshop, no emergence of missing value concepts.

4.2 Consistency of Quantitative Results in the Online Survey and the Workshop

Individual preferences regarding the importance of value elements in the pre-workshop online survey and group ranking during the workshop were overall consistent. For example, the two value elements considered to be the most important by responders (Patient’s financial burden, 4.6; and Uncertainty about long-term benefits and safety of the treatment, 4.5) were also ranked in the top 3 during the workshop by the group, where participants had to make trade-off decisions during a priority setting. Interestingly, in Ranking Vote 1, 2 and 3, although value elements changed their rankings, they tended to maintain their rank groupings (i.e., being ranked within #1–3, 4–6 or 7–9).

4.3 Importance of Qualitative Data

In research on PEx, collecting quantitative evidence is desirable but may not show the full picture without supplementary qualitative data. Patients, even with the same disease area and stage, might have completely different experiences with their condition and how it is affecting their own life. Individual patient quotes may reveal additional aspects of value otherwise hidden in numbers. We therefore recommend that regardless of the decision tool (i.e., conventional value assessment, MCDA), the collection of both qualitative and quantitative data is essential.

4.4 Conducting Patient-Centered Research

A major part of the framework was ensuring that patients are engaged in a truly meaningful manner through multiple steps: (1) patient-centric design of research through the involvement of a trained patient expert; (2) piloted each step with patients with NMOSD; (3) invested time to translate terminology into lay language and to create helpful visual tools for patients; (4) allocated fair compensation for participants for their time; and (5) considered the maximum time spent with tasks requiring concentration (which may depend on the nature of the disease). Methodology ensured all participants have a chance to (1) think about the value elements thoroughly, (2) interact with others to facilitate discussion and create consensus, and (3) share an informed view on PEx value elements. We commend the National Health Council on their recommendations and confirm the use of the Patient Engagement Rubric [30] helped enrich our study.

4.5 Cognitive Burden of the Study

Concerns have been raised on the cognitive burden of certain preference elicitation methods and its effect on the reliability of results [31]. We addressed this limitation by dividing the ranking into three consecutive votes, asking only for the top three of the 9, 6 and 3 value elements, respectively. (Notably, this did not only reduce the cognitive burden of participants, but also enabled them to change their priorities reflecting the group dynamics).

4.6 Relation to Other Research on Patient Value

The specific role of patient preferences in value assessment applications is still emerging [13, 31Previous research continues to test ways of incorporating patient preferences (e.g., discrete choice experiments) into decision contexts such as early-phase clinical development, benefit-risk assessment (regulatory specific), and health technology assessments [32]. For example, Bouvy et al. suggested presenting patient preference research as a stand-alone and distinct evidence source alongside a conventional cost-effectiveness analysis, instead of attempting to incorporate those preferences into modeling efforts [33]. Overall, our exercises are quite similar in nature to such efforts in the field, with some differences that highlight the nuance of the PEx through qualitative discussions, rankings, and weighting all in one session.

4.7 Applicability in Value Assessment

Value elements proposed in this framework could be used to support deliberative decision making by standardizing and prioritizing the list of value attributes to consider if aiming to understand the impact of health technologies on patients in a holistic manner. Alternatively, value elements can be integrated within existing value assessment frameworks through an augmented cost-effectiveness analysis, by including patient-centric domains in the calculation of incremental costs or effectiveness, or using them as cost-effectiveness threshold modifiers. Finally, value elements could be incorporated into existing or future MCDA tools with an explicit decision rule to guide decision making [24]. For developers, the inclusion of these value elements in decision making would provide a signal for additional evidence generation in a holistic manner and, if benefit claims are supported by adequate scientific evidence, those efforts will be rewarded [9, 12].

4.8 Limitations

There are some limitations of this research. First, eliciting PEx elements from existing frameworks as an initial step may introduce a selection bias toward what constitutes value. Second, while sample size is challenging in rare disease, the sample size of the current case study can be considered small. The dropout of the patient with visual difficulties highlights a potential selection bias with a possible impact on results (patients’ priorities may vary with progressing disease; however, the proposed methodology may be applicable primarily in mild or moderate disease stage), as well as a lesson to be learned for future studies including patients with severe symptoms. Nevertheless, there was another patient with NMOSD participating in the program who was blind and was still able to fully take part remotely even in the voting, using assistive devices at home. Where possible in future research, increased efforts should be made to account for recruitment and accessibility issues especially in rare diseases. It should be noted, however, that in a combined qualitative and quantitative session, larger sample sizes may increase the complexity and lose the nuance of the discussion. In addition, because NMOSD is a rare disease with treatments that were approved based on approximately 40 patients per study arm, we made every attempt to ensure a broader representation in descriptive characteristics (i.e., across age, race, and disease stage); however, a small sample size did not allow assessment of the heterogeneity of quantitative data. In terms of sample size, our case study is consistent with other patient involvement efforts such as the study by dosReis et al. where the analysis included 14 patients (representing various disease areas) [5]. Regardless, we plan to expand our analysis to at least two more rare disease areas to compare the importance of value elements across rare diseases.

Third, although this study represents engagement rather than a conventional research study that seeks to extract quantitative data alone, there were limitations to the extent patients were engaged throughout the design of the case study. One patient expert has been involved from the very beginning, but ideally, a panel of patients with NMOSD could have served as an advisory board for the research team during the full process. The pilot with two patients with NMOSD could partly counterbalance this limitation.

Fourth, the discussion during the workshop did not blind participants to the ranking results between the three consecutive cycles of voting. However, this is considered a minor source of bias, as part of the objective of the moderated discussion and voting exercises was to facilitate a consensus on the worth of PEx value elements at a group or averaged level.

Finally, NMOSD has a large representation of Spanish-speaking patients in the USA. We plan to update our framework with Spanish language materials to ensure we represent all communities not only with NMOSD but in other rare diseases moving forward.

4.9 Next Steps

The research will continue aiming to test the hypothesis if patients with different rare diseases (with variations across the nature of disease and age at onset) have different preferences towards PEx value elements. Additionally, the relative importance of conventional value elements, including clinical outcomes (i.e., survival, safety, quality of life) and cost, and the aggregate weight of additional PEx (where relative importance of PEx elements are estimated per disease basis, following the method proposed in this study) and societal value elements will be determined by a multi-stakeholder group (involving patients and their family caregivers, but also payers/decision makers, healthcare providers, academic researchers). The-long term objective is to complete a value framework for health technologies for rare diseases inclusive of PEx, societal, and conventional value elements.

We demonstrated that a combined qualitative and quantitative method is feasible and efficient, even in a rare disease such as NMOSD. For example, prioritized PEx value elements may inform value assessment applications through improving deliberations on “Other Benefits and Contextual Considerations” [3]. Specifically, instead of relying on deliberation panels to perceive the additional benefits of PEx value elements, patients can prioritize and weight those PEx value elements themselves as a separate exercise during the appraisal process. Continued applications of the proposed process will produce efficiencies over time and reduce current study duration from 6 months to 2–3 months. Furthermore, the PEx value elements need not be confined to deliberation. The findings may also flow to an “impact inventory” of all PEx value elements important to patients, providing a valuable resource for future researchers in value assessments [34,35,36]. Disease-specific impact inventory tables may inform an augmented cost-effectiveness analysis and MCDA applications in addition to overall evidence generation for future health technologies.

5 Conclusions

This research provides a framework for prioritizing the most important PEx value elements with a case study in rare disease. Using the method described in this study, we have demonstrated this method to be both feasible, efficient, and acceptable by patients. The process can inform value framework applications and may facilitate PEx evidence generation in early phases of health technology development to ultimately improve PEx with relevance specifically to rare diseases.

References

Diaby V, Ali A, Montero A. Value assessment frameworks in the United States: a call for patient engagement. Pharmacoecon Open. 2018;3(1):1–3.

Neumann P, Willke R, Garrison L. A health economics approach to US value assessment frameworks: introduction: an ISPOR Special Task Force Report [1]. Value Health. 2016;21(2):119–23.

Institute for Clinical and Economic Review. ICER 2020–2023 value assessment framework. 2020. https://icer.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/ICER_2020_2023_VAF_102220.pdf. Accessed 17 Jan 2021.

Lakdawalla D, Doshi J, Garrison L, Phelps C, Basu A, Danzon P. Defining elements of value in health care: a health economics approach: an ISPOR Special Task Force Report [3]. Value Health. 2018;21(2):131–9.

dosReis S, Butler B, Caicedo J, Kennedy A, Hong YD, Zhang C, et al. Stakeholder-engaged derivation of patient-informed value elements. Patient. 2020;13(5):611–21.

Thokala P, Devlin N, Marsh K, Baltussen R, Boysen M, Kalo Z, et al. Multiple criteria decision analysis for health care decision making: an introduction: report 1 of the ISPOR MCDA Emerging Good Practices Task Force. Value Health. 2016;19(1):1–13.

Lakdawalla D, Phelps C. Health technology assessment with diminishing returns to health: the Generalized Risk-Adjusted Cost-Effectiveness (GRACE) approach. Value Health. 2021;24(2):244–9.

Garrison L, Zamora B, Li M, Towse A. Augmenting cost-effectiveness analysis for uncertainty: the implications for value assessment: rationale and empirical support. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2020;26(4):400–6.

Inotai A, Brixner D, Maniadakis N, Dwiprahasto I, Kristin E, Prabowo A, et al. Development of multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) framework for off-patent pharmaceuticals: an application on improving tender decision making in Indonesia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):1–12.

Endrei D, Molics B, Ágoston I. Multicriteria decision analysis in the reimbursement of new medical technologies: real-world experiences from Hungary. Value Health. 2014;17(4):487–9.

Radaelli G, Lettieri E, Masella C, Merlino L, Strada A, Tringali M. Implementation of Eunethta Core Model® in Lombardia: the Vts framework. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2014;30(1):105–12.

Inotai A, Nguyen HT, Hidayat B, Nurgozhin T, Kiet PHT, Campbell JD, et al. Guidance toward the implementation of multicriteria decision analysis framework in developing countries. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2018;18(6):585–92.

Mühlbacher A, Johnson F. Giving patients a meaningful voice in European health technology assessments: the role of health preference research. Patient. 2017;10(4):527–30.

Jakab I, Whittington MD, Franklin E, Raiola S, Campbell JD, Kaló Z, et al. Patient and payer preferences for additional value criteria. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:1588.

US Food and Drug Administration. Patient-focused drug development: collecting comprehensive and representative input. 2018. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/patient-focused-drug-development-collecting-comprehensive-and-representative-input. Accessed 14 Jan 2021.

Garrison L, Pauly M, Willke R, Neumann P. An overview of value, perspective, and decision context: a health economics approach: an ISPOR Special Task Force Report [2]. Value Health. 2018;21(2):124–30.

Perfetto E. National Health Council project update: Patient-Centered Core Impact Sets (PC-CIS). 2021. https://nationalhealthcouncil.org/blog/project-update-patient-centered-core-impact-sets-pc-cis/. Accessed 15 Oct 2021.

Meekings KN, Williams CSM, Arrowsmith JE. Orphan drug development: an economically viable strategy for biopharma R&D. Drug Discov Today. 2012;17(13–14):660–4.

Sasinowski FJ, Panico EB, Valentine JE. Quantum of effectiveness evidence in FDA’s approval of orphan drugs: update, July 2010 to June 2014. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2015;49(5):680–97.

Wingerchuk DM, Lennon VA, Lucchinetti CF, Pittock SJ, Weinshenker BG. The spectrum of neuromyelitis optica. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(9):805–15.

Wingerchuk DM, Hogancamp WF, O’Brien PC, Weinshenker BG. The clinical course of neuromyelitis optica (Devic’s syndrome). Neurology. 1999;53(5):1107–14.

Tenembaum S, Yeh EA, Guthy-Jackson Foundation International Clinical Consortium (GJCF-ICC). Pediatric NMOSD: a review and position statement on approach to work-up and diagnosis. Front Pediatr. 2020;8:339.

Hor JY, Asgari N, Nakashima I, Broadley SA, Leite MI, Kissani N, et al. Epidemiology of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder and its prevalence and incidence worldwide. Front Neurol. 2020;11:501.

Inotai A, Jakab I, Brixner D, Campbell JD, Hawkins N, Kristensen LE, et al. Proposal for capturing patient experience through extended value frameworks of health technologies. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2021;27(7):936–47.

European Patients’ Academy on Therapeutic Innovation (EUPATI). Patient engagement through education. 2022. https://eupati.eu/. Accessed 12 Feb 2022.

Marsh K, Ijzerman M, Thokala P, Baltussen R, Boysen M, Kaló Z, et al. Multiple criteria decision analysis for health care decision making: emerging good practices: report 2 of the ISPOR MCDA Emerging Good Practices Task Force. Value Health. 2016;19(2):125–37.

SurveyMonkey. 2021. www.surveymonkey.com. Accessed 15 Apr 2021.

Mentimeter. 2021. www.mentimeter.com. Accessed 12 Jun 2021.

Németh B, Molnár A, Bozóki S, Wijaya K, Inotai A, Campbell JD, et al. Comparison of weighting methods used in multicriteria decision analysis frameworks in healthcare with focus on low-and middle-income countries. J Comp Eff Res. 2019;8(4):195–204.

National Health Council. The National Health Council rubric to capture the patient voice: a guide to incorporating the patient voice into the health ecosystem. 2019. https://nationalhealthcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/NHC_Patient_Engagement_Rubric.pdf. Accessed 15 Sep 2021.

Marsh K, De Bekker-Grob E, Cook N, Collacott H, Danyliv A. How to integrate evidence from patient preference studies into health technology assessment: a critical review and recommendations. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2021;37(1):E75. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462321000490

van Overbeeke E, Janssens R, Whichello C, Schölin Bywall K, Sharpe J, Nikolenko N, et al. Design, conduct, and use of patient preference studies in the medical product life cycle: a multi-method study. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:1395.

Bouvy JC, Cowie L, Lovett R, Morrison D, Livingstone H, Crabb N. Use of patient preference studies in HTA decision making: a NICE perspective. Patient. 2020;13(2):145–9.

McQueen RB, Slejko JF. Toward modified impact inventory tables to facilitate patient-centered value assessment. Pharmacoeconomics. 2021;39(4):379–82.

Neumann PJ. Toward better data dashboards for US drug value assessments. Value Health. 2021;24(10):1484–9.

Perfetto E, Oehrlein E, Boutin M, Reid S, Gascho E. Value to whom? The patient voice in the value discussion. Value Health. 2017;20(2):286–91.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the great work of Grace Honce, who moderated the workshop discussion, and Chan Voong for coordinating the logistical and technical aspects of the patient engagement process.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

The University of Colorado received institutional funding from the PhRMA Foundation and the University of Colorado Data Science to Patient Value Initiative, the University of Colorado School of Medicine, Anschutz Medical Campus.

Conflict of interest

R. Brett McQueen, Nicholas D. Mendola, and Kavita V. Nair received funding for this work through the PhRMA Foundation Center of Excellence Grant—Center for Pharmaceutical Value (pValue), paid for by the University of Colorado. R. Brett McQueen received a grant paid to the University of Colorado by Eli Lilly and consulting fees from the Monument Analytics and Institute for Clinical and Economic Review. Kavita V. Nair received grants through the University of Colorado by Genentech, Biogen, Novartis, Gilead Sciences, Bristol Meyers Squibb, and Rocky Mountain MS Center, received consulting fees from Biogen, Novartis, and Celgene, honoraria from Sanofi, and support for attending meetings from the American Academy of Neurology and Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers. Kavita V. Nair reports a leadership role as the Vice Chair at Payment, Policy and Coding Subcommittee, American Academy of Neurology. Ivett Jakab, Bertalan Németh, András Inotai, and Zoltán Kaló are employed by Syreon Research Institute. Syreon Research Institute received funding from the University of Colorado for this work. Ivett Jakab reports leadership positions as a member of the Board of Trustees, European Patients’ Academy on Therapeutic Innovation Foundation, and the President of European Patients’ Forum Youth Group. Jeffrey Bennett received institutional grants or contracts from Novartis, Mallinckrodt, Alexion, and the National Institutes of Health. Jeffrey Bennett reports both institutional and personal royalties or licenses and a patent of Aquaporumab, and consulting fees from MedImmune/Viela Bio/Horizon Therapeutics, Alexion, Chugai, Genentech, Genzyme, Mitsubishi-Tanabe, Reistone Biopharma, Roche, Beigene, and Abbvie. Jeffrey Bennett reports participation on a data safety monitoring board/advisory board of Roche/Genentech and Clene Nanomedicine.

Ethics approval

This study was deemed exempt by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board under protocol #21.340.

Availability of data and material

The manuscript and the ESM contain all data generated during the study.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

RBM, IJ, BN, AI, and ZK made contributions to the concept and design of the study. The manuscript was drafted by RBM, IJ, and AI. Analysis and interpretation of data were performed by BN, IJ, and AI. Critical revision of paper for important intellectual content was conducted by RBM, ZK, JB, and KVN. RBM, KVN, JB, and NM contributed to the provision of the patients, and administrative, technical, and logistic support. RBM, ZK, and JB supervised the study.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

McQueen, R.B., Mendola, N.D., Jakab, I. et al. Framework for Patient Experience Value Elements in Rare Disease: A Case Study Demonstrating the Applicability of Combined Qualitative and Quantitative Methods. PharmacoEconomics Open 7, 217–228 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-022-00376-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-022-00376-w