Abstract

Objectives

Evaluate the cost of illness associated with the 90-day period following acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and the implication of care pathway (percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI] vs medical management [MM]), in order to assess the potential financial risk incurred by providers for AMI as an episode of care.

Perspective

Reimbursement payment systems for acute care episodes are shifting from 30-day to 90-day bundled payment models. Since follow-up care and readmissions beyond the early days/weeks post-AMI are common, financial risk may be transferred to providers.

Setting

AMI hospitalization Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) standard analytical files between 10/1/2015 and 9/30/2016 were reviewed.

Methods

Included patients were Medicare beneficiaries with a primary diagnosis of AMI subsequently treated with either PCI or MM. Payments were standardized to remove geographic variation and separated into reimbursements for services during the hospitalization and from discharge to 90 days post-discharge. Results were stratified by Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Groups (MS-DRGs) individually and grouped between patients treated with MM and PCI. Risk-adjusted likelihood of utilization of post-acute nursing care and all-cause readmission was assessed by logistic regression.

Results

A total of 96,546 patients were included in the analysis. The highest total mean payment (US$32,714) was for MS-DRG 248 (PCI with non-drug-eluting stent with major complication or comorbidity). Total payments were similar between MM and PCI patients, but MM patients incurred the majority of costs in the post-acute period after discharge, with the converse true for PCI patients. MM without catheterization was associated with a twofold increase in risk of requiring post-acute nursing care and 90-day readmission versus PCI (odds ratio [95% confidence interval]: 2.01 [1.92–2.11] and 2.17 [2.08–2.27]). Smaller hospital size, diabetes, peripheral arterial disease, prior AMI, and multivessel disease were predictors of higher healthcare utilization.

Conclusions

MS-DRGs associated with the lowest reimbursements (and presumably, lowest costs of inpatient care) incur the highest post-discharge expenditures. As the CMS Bundled Payment for Care Improvement and similar programs are implemented, there will be a need to account for heterogeneous post-discharge care costs.

Video abstract (MP4 274659 KB)

Plain Language Summary

Around 805,000 heart attacks occur annually in the US. With an average age over 65 years, many heart attack patients qualify for Medicare health insurance. Under Medicare, hospitals (or ‘providers’) receive reimbursements for the cost of care associated with ‘acute care episodes’ (e.g., heart attacks) as a ‘bundled’ payment. The bundled reimbursements are typically based on pre-defined prices, with hospitals paying the difference if actual costs exceed these. Reimbursements are typically given for care costs from the initial heart attack through to hospital discharge and care in the 30-day post-discharge period. However, recently introduced reimbursement models such as BPCI Advanced have moved to expand this to 90 days. Since follow-up care and additional cardiovascular readmissions are common beyond 30 days, extension of the reimbursement period to 90 days could increase financial risk to hospitals/providers if these additional costs are not included in reimbursements. To assess the potential impact of this, we investigated the cost of illness for heart attack and the implication of type of care: medical management (standard medication given after heart attack) vs. percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI; standard medication plus a non-surgical procedure to widen heart blood vessels). We found that 90-day costs after heart attack are substantial regardless of type of care. We found that post-discharge costs were generally high, but higher for medically managed patients than those receiving PCI. Our analysis also suggests Medicare disease classifications associated with lowest payments for heart attack (and presumably, lowest hospitalization costs) are associated with the highest post-discharge expenditures. Overall, our study suggests that new payment models should account for variable post-discharge care costs, and new therapies are needed to reduce additional events, readmissions, and associated costs in heart attack patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Substantial post-acute myocardial infarction costs are incurred through the 90-day post-discharge period irrespective of the care pathway, suggesting that moving from traditional 30-day payment models to 90-day payment models may increase financial risk to hospital providers. |

Costs of post-acute care are substantially higher for medically managed patients than for those receiving percutaneous coronary intervention, highlighting an unmet need for therapies that reduce recurrent cardiovascular events and readmissions in these patients. |

Heterogeneous post-discharge costs of care must be considered when implementing the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Bundled Payment for Care Improvement and similar programs. |

1 Introduction

In the United States, there are an estimated 805,000 incidences of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) per year, and with an average age of 65.6 years for males and 72.0 for females for first AMIs [1], a substantial proportion of AMI patients are eligible for federally sponsored health insurance under Medicare (i.e., ≥ 65 years). In fee-for-service Medicare, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) reimburses hospitals for inpatient services based on Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Groups (MS-DRGs) [2]. These MS-DRG payments are typically standardized and designed to cover all charges associated with inpatient stay. Reimbursements under Medicare to hospitals for acute care episodes, such as AMI, have been typically linked to services used during a 30-day period [3]. However, in 2013, CMS introduced a voluntary bundled payment system, the Bundled Payment for Care Improvement (BPCI) Program [4], which involves a single payment for services used during an episode of care and extends the period up to 90 days after discharge [5]. The current model in place up to December 31, 2023 is BPCI advanced (year 4) [6]. Under the current model, CMS reimburses episodes based on pre-defined, yearly fixed target prices. Target prices are compared with actual episode costs at the end of each year, and providers must pay the difference if actual costs exceed the target price [6].

Because hospitals are often the accountable provider for managing bundled payments, extended 90-day reimbursement programs such as BPCI present implications for providers when applied to AMI as an episode of care. First, treatment of AMI is complex and usually includes follow-up appointments that extend beyond discharge. Second, patients with AMI are at high risk of subsequent cardiovascular (CV) events, such as recurrent AMI, stroke, and CV death [1]. Of the 805,000 AMIs that occur in the United States per year, it is estimated that a quarter are recurrent, with recurrent AMIs associated with a twofold increase in 5-year mortality versus index AMIs [1, 7]. Costs associated with CV-related hospitalizations have been found to be $20,000 higher than non-CV related hospitalizations (all costs reported in this article are in US dollars) [8], and Medicare expenditures for AMI in the 30-day period have been found to be higher than for other CV-related conditions such as heart failure [9]. Moreover, there is growing evidence that readmission burden for AMI extends beyond the typical 30-day period [9, 10]. A recent study found that approximately a quarter of AMI episodes in the USA are associated with readmission within 90 days, an increase of approximately 65% on the proportion readmitted within 30 days [11]. There are, therefore, concerns that programs such as BPCI may increase financial risk to enrolled providers.

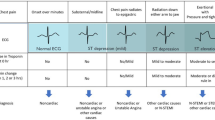

A key factor to consider relating to provider burden early after AMI is the treatment pathway of the index event, specifically with non-surgical interventions whereby patients are treated by either percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or purely managed pharmacologically (i.e., medical management [MM]). As PCI is associated with higher cost of acute care for AMI, CMS segregates payments for AMI between those who are medically managed and those who undergo PCI [5]. Depending on the clinical presentation and treatment prognosis, primary PCI may be the preferred pathway of care for patients with AMI [12,13,14,15] and data show that between 7.9 and 27.4% of AMI events are medically managed [16]. However, the need and suitability for PCI depends upon many clinical factors, including if the event was associated with ST-segment elevation, and other factors including individual anatomy and comorbidities [12,13,14,15, 17]. Further, there are numerous patient factors that increase clinical burden following AMI, including age, sex, and comorbidities such as diabetes, peripheral arterial disease (PAD), and multivessel disease (MVD) [11, 18,19,20].

To investigate the potential extent of risk faced by hospitals enrolled in an extended 90-day bundled payment system, in a Medicare claims analysis, we evaluated payments and healthcare utilization associated with AMI as an episode of care up to 90 days post-discharge and the impact of treatment pathway (PCI or MM). A further aim was to evaluate the association of pathway of care and patient comorbidities, with particular focus on MVD, on post-discharge healthcare utilization and costs.

2 Methods

The present study was a retrospective analysis of Medicare claims (October 1, 2015 to September 30, 2016).

2.1 Data Sources

The analytic file was derived from the CMS 100% Standard Analytic Files (SAFs) for AMI hospitalizations. These contain adjudicated medical claims submitted by inpatient hospital providers for payment for services provided, including complete information on diagnoses, procedures, MS-DRG, dates of service, reimbursement amounts, provider, and beneficiary demographics. These claims data are compiled into a limited dataset, which only contains one data element of protected health information (date of service) and are standardized to remove geographic variation.

The CMS March 2018 Provider of Services File was utilized to obtain information on whether the hospitals have cardiac catheterization rooms and cardiac surgical units. In addition, the Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS) Final Rule Impact File was used to obtain information relating to community size (number of residents: < 50,000, 50,000 to < 1 million, and ≥ 1 million), hospital size (number of beds: < 250, 250–499, and ≥ 500), readmission adjustment factor (the adjustment made by CMS to yearly payments because of readmission performance measures, with a high of 1 [100%] and a low of 0.97), and percentage of hospital days paid by Medicare as a percentage of total days.

2.2 Sample

The sample included Medicare beneficiaries (continuously enrolled in Medicare Part A and B for 9 months prior to admission through 3 months after the discharge date) with a primary diagnosis for AMI (10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems [ICD-10] code I21.x) on an inpatient claims record from an IPPS hospital and discharged with an MS-DRG of 280–282 or 246–251. The identification and selection of eligible study participants, including the exclusion criteria applied, is detailed in Figure 1. Patients for whom PCI would be usually contraindicated (e.g., those with kidney disease, sepsis) or not be performed (e.g., patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting [CABG] surgery) were excluded from the analysis to minimize confounders in the assessment of economic costs associated with pathway of care. In addition, 5735 visits for patients who were not treated at hospitals that participate in CMS’ IPPS were excluded. This exclusion was applied because the data on facility characteristics was not available for those hospitals.

Flow diagram to identify population eligible for analysis. AMI acute myocardial infarction, CABG coronary artery bypass grafting, FFS fee for service, IPPS Inpatient Prospective Payment System, MI myocardial infarction, MS-DRG Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Groups. *Patients may have multiple hospital stays if they suffer ≥ 1 AMI during the 1-year evaluation period. †Death prior to the 90-day post-acute window does not exclude patients. ‡Patients who undergo a CABG during or immediately after the inpatient stay (within 45 days) are excluded from the study; however, a history of CABG qualifies a patient as having multivessel disease and does not exclude a patient from the study

2.3 Measures

Distribution of acute and post-discharge costs across facilities was assessed. Each hospitalization was assigned to a pathway of care: MM without referral to catheterization lab, MM following referral to catheterization lab, PCI, or CABG (Table 1). Patients were assigned a diagnosis of multivessel coronary artery disease (MVD) if multiple vessels were treated with a PCI or atherectomy, or if the patient had previously had a CABG. Other comorbidities diagnosed during the inpatient stay were captured.

2.4 Analyses

Patient demographics were compared between groups using chi-square tests for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables. Medicare payments were standardized to remove geographical variation and separated into reimbursements for services during hospitalization and from discharge to 90 days post-discharge. Results were stratified by MS-DRG individually, and mean payments are reported. Costs presented represent actual costs during the study time frame and are not updated to current year dollars. The mean for utilizers is the total costs for a service (e.g., emergency department [ED] visits) divided by the total number of utilizers of a service (e.g., MS-DRG 280 discharged patients who visit an ED within 90 days of discharge). Median and interquartile range (IQR) payments are also reported.

Payments were separately estimated for the two bundles under study (i.e., PCI or MM), which are described in Table 1. Chi-square tests were used to evaluate the significance of relationships between categorical variables, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for categorical and ratio level variables.

Excess hospital readmissions are penalized by CMS, and, therefore, may be a primary source of financial risk for hospitals. Post-acute care (in the form of skilled nursing facilities and, to a lesser extent, home health, long-term care hospitals, and inpatient rehabilitation hospitals) is another potential source of cost and risk. Because pathway of care (i.e., PCI vs MM) is related to the utilization of post-acute nursing care, which is in turn related to likelihood of rehospitalization, logistic regression was used to evaluate the risk-adjusted likelihood of utilization of post-acute nursing care and all-cause readmission.

All analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.4.

3 Results

3.1 Study Population

In total, 96,546 unique patient stays were identified (Fig. 1). The study population had a mean age of 74 years, were predominantly white, and more were male (Table 2). Characteristics including age, sex, race, and MVD status were significantly different between MM and PCI treated patients (all p < 0.001; Table 2). Additional observations of note were that female patients were significantly older than male patients (75.3 vs 72.0 years, p < 0.0001; Table 2), patients treated with PCI were significantly younger than MM patients (71.5 vs 76.1 years, p < 0.0001; Table 2), a significantly greater proportion of white patients were treated with PCI than African Americans (48,986/84,428 [58.0%] vs 3393/7067 [48.0%], p < 0.0001; Table 2), and more male than female patients were treated with PCI (34,536/53,051 [65.1%] vs 20,741/43,495 [47.7%], p < 0.0001; Table 2).

3.2 Payments for Healthcare Services for AMI Patients

The overall mean cost for an AMI episode of care (weighted by the number of individuals discharged under each DRG) was $22,034 (median $17,561, IQR $13,065) from hospital admission through 90 days post-discharge (Table 3). Within both PCI and MM MS-DRG families, inpatient (acute) and outpatient (post-acute) payments varied substantially but were highest amongst patients with major complications or comorbidities. The largest total mean payment was associated with MS-DRG 248 (PCI with non-drug eluting stent with major complication/comorbidity or ≥ 4 vessels/stents; mean $32,714, median [IQR] $27,007 [$15,486]), followed by MS-DRG 250 (PCI without coronary artery stent without major complication/comorbidity; mean $31,963, median [IQR] $24,478 [$16,669]), MS-DRG 246 (PCI with drug-eluting stent with major complication/comorbidity or ≥ 4 vessels/stents; mean $30,879, median [IQR] $26,287 [$11,433]), and MS-DRG 280 (AMI, discharged alive with major complication/comorbidity; mean $29,164, median [IQR] $19,983 [$22,047]). The lowest mean costs were associated with MS-DRG 282 (AMI, discharged alive without complication/comorbidity or major complication/comorbidity; mean $17,752, median [IQR] $9910 [$15,240]).

Payments for acute services were considerably higher for patients who had undergone PCI than for those who were medically managed ($16,230 vs $8536). However, post-acute services represented a higher proportion of the total expenditure in MM patients (55–62%) compared with PCI patients (26–41%) (Figure 2).

3.3 Utilization of Post-discharge Services

Utilization of post-discharge services by MS-DRGs is shown in Supplementary Table 1 (see the electronic supplementary material). Non-ED post-discharge care was the most frequently used classification of post-discharge service, and the least utilized services were long-term care facilities. Compared to patients receiving PCI, MM patients were significantly more likely to be readmitted (30.5% vs 15.4%, p < 0.0001), to require home health agency services (16.7% vs 8.2%, p < 0.0001), to be discharged to a skilled nursing facility (16.5% vs 5.0%, p < 0.0001), to receive rehabilitation services (23.7% vs 21.8%; p < 0.0001), and to require an additional ED visit (1.2% vs 0.6%; p < 0.0001). In contrast, PCI-managed patients used significantly more outpatient (non-ED) services than MM patients (65.8% vs 58.3%, p < 0.0001).

3.4 Factors Associated with Utilization of Post-acute Nursing Care

Apart from dementia, the strongest predictor of the requirement for post-acute nursing care was MM without catherization versus PCI, with these patients around twice as likely to be referred than those who received PCI (odds ratio [OR] 2.01, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.92–2.11; Table 4). Multiple comorbidities predicted need for post-acute care, the strongest of which being dementia, followed by malnutrition, and sepsis. Comorbidities that typically correlate with MVD (e.g., diabetes with/without complications, treatment for diabetes, PAD, coronary atherosclerosis, and a history of AMI) were more likely to be referred to post-acute care (Table 4). Referral rates to post-acute care were higher in hospitals without open heart surgical units, located in more populous areas (over a million residents), and in which Medicare paid for more than 45% of days (Table 4). Female gender and older age were also significantly associated with an increased likelihood of referral to post-acute care.

3.5 Predictors of All-Cause Readmissions

The strongest predictor of 90-day hospital readmissions was utilization of post-acute nursing care, which was associated with more than a fourfold increase in the likelihood of 90-day readmission (OR 4.38, 95% CI 4.21–4.55; Table 4). There was also an influence of hospital size/type on all-cause readmission rates, with readmissions more likely from hospitals with fewer beds, hospitals without open heart surgical units, and Medicare-dependent hospitals (Table 4). Other predictors of readmission were generally similar to predictors of post-acute nursing care. Again, MM was associated with greater utilization than PCI, with MM patients treated without catheterization being the most likely to be readmitted. Notable exceptions were that MVD was associated with greater odds of readmission, the lack of association between sex and readmissions, and that increasing age was associated with a decrease in the chance of 90-day readmission.

4 Discussion

In this Medicare claims analysis, we found the 90-day period after AMI was associated with substantial economic burden irrespective of the pathway of care (MM or PCI), and that post-acute care spending (i.e., up to 90 days post-discharge) encompassed a significant proportion of total healthcare spending for AMI as an episode of care. Interestingly, the pathway of care influenced when the bulk of these costs are incurred; MM incurred up to approximately two-thirds of costs in the post-acute period, whereas in PCI-managed patients, the majority of spending was for services delivered in hospital. Importantly, our results suggest that this was not purely due to the higher cost of PCI treatment relative to MM, as costs for post-acute care settings such as inpatient readmissions were higher in MM patients than in PCI patients. This is also supported by our finding that MM was associated with a twofold increase in the likelihood to require post-acute nursing care and be readmitted to hospitals.

We found that comorbidities such as MVD, diabetes, PAD, and prior myocardial infarction (MI) were associated with a higher risk of 90-day readmission and, similarly, smaller hospitals with less surgical cardiac expertise were associated with higher rates of 90-day readmission. Conversely, increasing age was weakly associated with a decreased likelihood of 90-day readmission, although this should be treated with caution, since age is correlated with other comorbidities used in our model and thus may be subject to collinearity. These results are in line with a prior Medicare analysis by Culler et al. [5], which also reported that MM is associated with higher readmissions within 90 days versus PCI and higher rates of comorbidities, and showed that PAD, diabetes, and prior MI are associated with higher frequency of readmissions. Taken together with our cost analysis, our findings build upon this by demonstrating that this high clinical risk is associated with a substantial economic burden.

Prior analyses of hospitals participating in the BPCI for various episodes of care, which included AMI, have reported that despite covering costs incurred over an extended 90-day period, the BPCI is associated with unchanged or lower payments for acute care episodes compared to 30-day payment programs [21,22,23,24]. This is important given recent evidence of high hospitalization burden in the 90 days post-discharge, with readmission rates ranging between 24–28% [5, 11]. Moreover, 38% of major adverse CV event readmissions after AMI in the United States occur between 30 and 90 days after discharge [25], and the 90-day post-AMI period has been reported to be associated with an approximate 65% increase in AMI readmissions versus the 30-day period [11]. Thus, if reimbursements for acute care episodes in 90-day models are comparable to those of 30-day payment programs [21,22,23,24], moving from a typical 30-day reimbursement model to a 90-day model such as BPCI may increase the financial risk incurred by hospitals since they must pay the difference if the actual cost of care exceeds the fixed reimbursement given by the payment program [6]. This is particularly relevant to medically managed AMI patients, for whom we found around two-thirds of costs are incurred in the post-acute period up to 90 days after discharge.

Interestingly, we found that higher PCI use and centers with cardiac units were associated with lower post-discharge expenditure; this is supported by Pandey et al. [26], who found these factors to be associated with higher post-discharge ‘home time,’ which may be a better metric of hospital performance. Moreover, although the MM MS-DRGs incurred the highest post-discharge expenditures, they have the lowest reimbursements (and presumably, lowest costs of inpatient care). This may result in a situation where hospitals become financially incentivized to perform PCI, despite it not always being clinically appropriate/possible, e.g., due to high bleeding risk [27]. Despite the BCPI aiming to reduce costs and improve quality, when applied to CV care in general, it has been shown that the program has not significantly improved quality of care or reduced spending [28].

Our analysis supports that MVD is associated with higher rates of readmission within 90 days. This is interesting given the increasing focus on MVD as a key driver of poor outcomes following AMI, with the risk of recurrent AMI events increasing in a stepwise manner with the increasing number of non-culprit plaque/vessels [29, 30]. There is growing evidence that complete revascularization, i.e., treatment of culprit as well as non-culprit lesions in a single or staged procedure, improves clinical outcomes, and consequently, standard of care is moving towards complete revascularization where clinically appropriate [17, 31, 32]. Nonetheless, the increased risk of 90-day readmissions among MVD patients supports that higher atherosclerotic burden in these patients translates into higher risk of 90-day readmission.

The finding that post-acute nursing care utilization was more likely in more populous areas suggests that availability was lower in rural areas, as higher post-acute care utilization did not translate into higher 90-day readmissions in more populous areas. The finding that smaller, presumably rural, hospitals showed worse 90-day readmissions may be related to the provision of standard of care medications, which has been shown to be less comprehensive by rural hospitals [33]. In this regard, pharmacist-led transition of care programs have been shown to significantly decrease readmissions [34]. Similarly, we found that a lack of specialized cardiac units was associated with increased readmissions; in addition to this, there could be variation between individual surgeons. However, as previously surmised [5], Medicare claims data highlight an overall unmet need in preventive therapeutics in the high-risk 90-day period post-AMI, and that new strategies are required. Currently, therapies that reduce the pro-atherogenic lipoprotein low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (i.e., statins, ezetimibe, and proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitors) take several months to years to have a pronounced effect on CV events [35, 36]. Pharmacological interventions targeting atherosclerotic plaque may be needed for those who do not receive PCI and have comorbidities placing them at high risk, particularly MVD. This may in turn reduce the financial risk on providers in a 90-day bundled payment system.

This study had some limitations. First, since there is currently no ICD-10 diagnosis code for MVD, the approach used, as described in the methods, may have been unable to capture all true MVD patients. Second, the exclusion criteria used to minimize confounders in the assessment of economic costs associated with the pathway of care may have introduced bias in the reported clinical outcomes. Third, although the CMS data files used were the most recent available at study conception, future studies using currently available CMS data are warranted to incorporate changes in clinical practice and implementation of new treatment modalities. Fourth, the analysis did not include non-fee-for-service Medicare populations, e.g., Medicare Advantage and commercially insured or Medicaid populations. These populations may have different post-discharge risks and costs. Finally, AMI episodes of care were only included where AMI was the primary diagnosis; patients treated for AMI in combination with other conditions may also have had different post-discharge risks and costs.

5 Conclusions

The 90-day post-AMI period is associated with significant post-acute care costs, particularly among patients who are medically managed. Care pathway impacts the timing that costs are incurred, with medically managed patients incurring higher costs in the post-acute period in relation to some care settings compared to those undergoing PCI. As the CMS BPCI and similar programs are implemented, there will be a need to account for these heterogeneous post-discharge costs of care. Centering payments for AMI around a 90-day model further highlights that the clinical and economic burden of AMI goes beyond the immediate discharge period, representing a current unmet need in preventative cardiology. There is a particular need for additional preventative measures in those who are medically managed, both in a clinical sense, and to reduce financial risk to hospitals/providers.

Change history

28 September 2022

A peer-reviewed video abstract and a peer-reviewed plain language summary were retrospectively added to this publication.

27 September 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-022-00367-x

References

Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2020 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141(9):e139–596.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. MS-DRG classification and software. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/MS-DRG-Classifications-and-Software. Accessed 26 Jan 2021.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Bundled payments for care improvement (BPCI) initiative: General information. https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/bundled-payments#:~:text=Initiative%3A%20General%20Information-,Bundled%20Payments%20for%20Care%20Improvement%20(BPCI)%20Initiative%3A%20General%20Information,during%20an%20episode%20of%20care. Accessed 26 Jan 2021.

Wadhera RK, Yeh RW, Joynt Maddox KE. The rise and fall of mandatory cardiac bundled payments. JAMA. 2018;319(4):335–6.

Culler SD, Kugelmass AD, Cohen DJ, Reynolds MR, Katz MR, Brown PP, et al. Understanding readmissions in Medicare beneficiaries during the 90-day follow-up period of an acute myocardial infarction admission. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(21):e013513.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Bundled payments for care improvement advanced. BPCI advanced model year 4 fact sheet. https://innovation.cms.gov/media/document/bcpi-model-overview-fact-sheet-my4. Accessed 1 Feb 2021

Nakatani D, Sakata Y, Suna S, Usami M, Matsumoto S, Shimizu M, et al. Incidence, predictors, and subsequent mortality risk of recurrent myocardial infarction in patients following discharge for acute myocardial infarction. Circ J. 2013;77(2):439–46.

Punekar RS, Fox KM, Richhariya A, Fisher MD, Cziraky M, Gandra SR, et al. Burden of first and recurrent cardiovascular events among patients with hyperlipidemia. Clin Cardiol. 2015;38(8):483–91.

Wang Y, Eldridge N, Metersky ML, Sonnenfeld N, Rodrick D, Fine JM, et al. Association between medicare expenditures and adverse events for patients with acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, or pneumonia in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(4):e202142.

Vallabhajosyula S, Payne SR, Jentzer JC, Sangaralingham LR, Kashani K, Shah ND, et al. Use of post-acute care services and readmissions after acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiac arrest and cardiogenic shock. In: Mayo Clinic Proceedings: innovations, quality & outcomes; 2021.

Khera R, Jain S, Pandey A, Agusala V, Kumbhani DJ, Das SR, et al. Comparison of readmission rates after acute myocardial infarction in 3 patient age groups (18 to 44, 45 to 64, and >/=65 years) in the United States. Am J Cardiol. 2017;120(10):1761–7.

Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, Casey DE Jr, Ganiats TG, Holmes DR Jr, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(24):e139–228.

Collet JP, Thiele H, Barbato E, Barthelemy O, Bauersachs J, Bhatt DL, et al. 2020 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(14):1289–367.

Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: the Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39(2):119–77.

O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Casey DE Jr, Chung MK, de Lemos JA, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(4):485–510.

Vora AN, Wang TY, Hellkamp AS, Thomas L, Henry TD, Goyal A, et al. Differences in short- and long-term outcomes among older patients with ST-elevation versus non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction with angiographically proven coronary artery disease. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2016;9(5):513–22.

Riley RF, Henry TD, Mahmud E, Kirtane AJ, Brilakis ES, Goyal A, et al. SCAI position statement on optimal percutaneous coronary interventional therapy for complex coronary artery disease. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;96(2):346–62.

Bansilal S, Bonaca MP, Cornel JH, Storey RF, Bhatt DL, Steg PG, et al. Ticagrelor for secondary prevention of atherothrombotic events in patients with multivessel coronary disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(5):489–96.

Bhatt DL, Eagle KA, Ohman EM, Hirsch AT, Goto S, Mahoney EM, et al. Comparative determinants of 4-year cardiovascular event rates in stable outpatients at risk of or with atherothrombosis. JAMA. 2010;304(12):1350–7.

Jernberg T, Hasvold P, Henriksson M, Hjelm H, Thuresson M, Janzon M. Cardiovascular risk in post-myocardial infarction patients: nationwide real world data demonstrate the importance of a long-term perspective. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(19):1163–70.

Dummit LA, Kahvecioglu D, Marrufo G, Rajkumar R, Marshall J, Tan E, et al. Association between hospital participation in a Medicare Bundled Payment Initiative and payments and quality outcomes for lower extremity joint replacement episodes. JAMA. 2016;316(12):1267–78.

Joynt Maddox KE, Orav EJ, Zheng J, Epstein AM. Evaluation of Medicare’s bundled payments initiative for medical conditions. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(3):260–9.

Joynt Maddox KE, Orav EJ, Zheng J, Epstein AM. Learning and the “early joiner” effect for medical conditions in Medicare’s Bundled Payments for Care Improvement program: retrospective cohort study. Med Care. 2020;58(10):895–902.

Rolnick JA, Liao JM, Emanuel EJ, Huang Q, Ma X, Shan EZ, et al. Spending and quality after three years of Medicare’s bundled payments for medical conditions: quasi-experimental difference-in-differences study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1780.

Sreenivasan J, Abu-Haniyeh A, Hooda U, Khan MS, Aronow WS, Michos ED, et al. Rate, causes, and predictors of 90-day readmissions and the association with index hospitalization coronary revascularization following non-ST elevation myocardial infarction in the United States. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;20:1–10.

Pandey A, Keshvani N, Vaughan-Sarrazin MS, Gao Y, Girotra S. Evaluation of risk-adjusted home time after acute myocardial infarction as a novel hospital-level performance metric for medicare beneficiaries. Circulation. 2020;142(1):29–39.

Ahmad M, Mehta P, Reddivari AKR, Mungee S. Percutaneous coronary intervention. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL); 2020.

Sukul D, Eagle KA. Value-based payment reforms in cardiovascular care: progress to date and next steps. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J. 2020;16(3):232–40.

Brener SJ, Mintz GS, Cristea E, Weisz G, Maehara A, McPherson JA, et al. Characteristics and clinical significance of angiographically mild lesions in acute coronary syndromes. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5(3 Suppl):S86-94.

Ozcan C, Deleskog A, Schjerning Olsen AM, Nordahl Christensen H, Lock Hansen M, Hilmar GG. Coronary artery disease severity and long-term cardiovascular risk in patients with myocardial infarction: a Danish nationwide register-based cohort study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2018;4(1):25–35.

Ibrahim H, Sharma PK, Cohen DJ, Fonarow GC, Kaltenbach LA, Effron MB, et al. Multivessel versus culprit vessel-only percutaneous coronary intervention among patients with acute myocardial infarction: Insights from the TRANSLATE-ACS observational study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(10):e006343.

Panaich SS, Arora S, Patel N, Schreiber T, Patel NJ, Pandya B, et al. Comparison of in-hospital mortality, length of stay, postprocedural complications, and cost of single-vessel versus multivessel percutaneous coronary intervention in hemodynamically stable patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (from nationwide inpatient sample [2006 to 2012]). Am J Cardiol. 2016;118(7):950–8.

Baldwin LM, Chan L, Andrilla CH, Huff ED, Hart LG. Quality of care for myocardial infarction in rural and urban hospitals. J Rural Health. 2010;26(1):51–7.

Bae-Shaaw YH, Eom H, Chun RF, Steven FD. Real-world evidence on impact of a pharmacist-led transitional care program on 30- and 90-day readmissions after acute care episodes. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2020;77(7):535–45.

Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, McCagg A, White JA, Theroux P, et al. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(25):2387–97.

Schwartz GG, Steg PG, Szarek M, Bhatt DL, Bittner VA, Diaz R, et al. Alirocumab and cardiovascular outcomes after acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(22):2097–107.

Acknowledgements

Medical Writing assistance was provided by Meridian HealthComms Ltd, Plumley, UK, funded by CSL Behring.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was sponsored by CSL Behring LLC.

Conflict of interest

KBA is a consultant to CSL Behring. JEA is a partner of Healthcare Compliance Management LLC. JNL is Chief Operating Officer at Health Analytics LLC. SG is an employee of CSL Behring.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The analyses performed in this study were in accordance with the 1964 declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. The study used only de-identified data that were obtained from an existing database (Centers for Medicare and Medicare services Standard Analytical, Provider of Service and Inpatient Prospective Payment System Final Rule Impact Files) and did not involve the collection, use, or transmittal of individually identifiable data. All database records are statistically de-identified and certified to be fully compliant with US patient confidentiality requirements set forth in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA). As the database used in the study is fully de-identified and compliant with the HIPPA, this study was exempted from Institutional Review Board approval and informed consent was not required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

The authors declare that the data associated with this study are available upon reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

KBA, JEA, JNL, and SG wrote and approved the final version of the manuscript and contributed to interpretation of the data. JNL and SG conducted data collection and analysis.

Additional information

The original online version of this article was revised: A peer-reviewed video abstract and a peer-reviewed plain language summary were retrospectively added to this publication.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Allen, K.B., Alexander, J.E., Liberman, J.N. et al. Implications of Payment for Acute Myocardial Infarctions as a 90-Day Bundled Single Episode of Care: A Cost of Illness Analysis. PharmacoEconomics Open 6, 799–809 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-022-00328-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-022-00328-4