Abstract

Background

In Ireland, health technology assessment (HTA) submissions for orphan drugs or drugs for rare diseases have increased in recent years but have not been explicitly analysed. All evaluations are conducted by the National Centre for Pharmacoeconomics (NCPE).

Objectives

The objectives of this study were to ascertain the number of orphan drug submissions to the NCPE and determine how these drugs proceeded through the NCPE critical evaluation process compared with non-orphan drug submissions.

Methods

This was a retrospective analysis of applicant rapid review submissions made to the NCPE from January 2012 to December 2017 inclusive. Drugs were categorised according to the following definitions: orphan (non-cancer) drug, orphan (cancer) drug and ultra-orphan drug. In each of the three categories, the outcome of rapid review appraisal, and where relevant, the outcome of the subsequent HTA was recorded.

Results

During the period of study, 280 rapid review submissions were made to the NCPE, of which 21 were for orphan (non-cancer) drugs, 24 were for orphan (cancer) and ten were for ultra-orphan drugs. After rapid review, 44%, 78% and 100% of orphan (non-cancer) drugs, orphan (cancer) drugs and ultra-orphan products, respectively, were recommended for full HTA. When the outcome of the rapid review process was compared between orphan drugs and non-orphan drugs, a statistically significant difference was detected in the proportion of rapid reviews for which the outcome was ‘HTA recommended’ (Pearson’s Chi-squared test; p = 0.04).

Conclusions

The number of submissions to the NCPE for orphan drugs has increased in recent years. The rapid review and HTA process in Ireland plays a role in supporting the reimbursement decision-making process for orphan drugs in a similar manner to the process established for non-orphan drugs. However, the outcome of the reimbursement process for orphan drugs versus non-orphan drugs (in terms of access for patients) has yet to be quantified.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Orphan drugs are therapeutic agents designed for the management of rare diseases. Working definitions of rare diseases vary widely across organizations around the world. In the USA, the Orphan Drug Act of 1983 established a definition for use by the US FDA based on a prevalence of not more than 200,000 individuals, which—taking into account the size of the US population—would represent approximately 1 in 1500 individuals [1]. The EU’s definition, which was introduced through legislation in the year 2000, affects joint public health actions and regulatory submissions to the European Medicines Agency (EMA). It is somewhat lower, at not more than 5 per 10,000 (1 per 2000) individuals [2]. In the EU, this legislation implies that the pharmaceutical industry can (1) obtain scientific advice on clinical trial protocols at a reduced charge, (2) gain access to the EMA centralized licensing procedure, (3) get reduced registration costs, and (4) benefit from 10 years of market exclusivity after registration [3]. Japan considers diseases to be rare if they affect not more than 50,000 patients, or less than 1 in 2500 individuals given current population estimates. The 2015 report from the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) Rare Disease Special Interest Group [4], which provided an overview of rare disease definitions currently used globally, concluded that there was some global consistency in using the terms ‘rare disease’ and ‘orphan drug’ to describe the technology associated with the rare disease. Based on the results of their systematic literature review, they proposed that the terminology ‘rare disease’, coupled with a prevalence threshold in the range of 40–50 cases per 100,000 (1 in 2000–2500) individuals, could present a realistic starting point for a harmonised definition of rare disease.

Globally, the lack of an explicit definition used by regulatory processes to identify a boundary between rare and ‘ultra-rare’ diseases is noted. Many countries have established separate procedures for consideration of funding treatments for patient populations that are much smaller than the lower bounds of the standard population size eligible for an orphan drug [3]. For example, the health technology assessment (HTA) agency in Italy considers a disease prevalence of 1 per 1,000,000 to represent an ultra-rare disease, whereas the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) restricts entry into a separate assessment track named the Highly Specialized Technologies (HST) programme to diseases with a prevalence of not more than 1 per 50,000 individuals [5, 6].

Despite the commercial incentives made available to encourage orphan drug development and manufacture, the costs of orphan drugs are high. Factors that reportedly influence their price setting include research and development (R&D), costs, clinical effectiveness, drug quality and disease prevalence [7, 8]. However, the effectiveness of some orphan drugs has not been clearly demonstrated, and the evidence regarding their safety is often sparse at the time of regulatory approval [9]. Furthermore, in the UK, for example, some funders of care under the NHS have refused to fund certain orphan drugs because they are not considered cost effective, thereby denying patients access to potentially useful drug interventions [10].

In Ireland, all new drugs are considered for HTA prior to a reimbursement decision by the health payer. All HTAs for pharmaceuticals are conducted by the National Centre for Pharmacoeconomics (NCPE). The NCPE evaluation process has been described previously [11]. In short, the relevant applicant pharmaceutical company (‘the applicant’) submits a rapid review dossier to the NCPE. Each rapid review dossier submission pertains to one drug for one indication. The NCPE critically appraises all elements of the dossier. The outcome of the rapid review process (which is a 4-week process) is determined by uncertainty in either the clinical or the economic domains or a combination of both (e.g. lack of robust clinical evidence, no evidence of therapeutic benefit, potentially large budget impact). In doing so, the NCPE determines the requirement for a full HTA submission from the applicant. Where there is a recommendation for a full HTA to be submitted, a prescriptive critical appraisal process (which is a 90-day process) is followed, the outcome of which is an NCPE recommendation to the National Drugs Committee (i.e. the decision maker) on whether or not to reimburse the drug. Likewise, the National Drugs Committee (i.e. decision maker) of the Health Services Executive (HSE), in arriving at their decision, consider all of the criteria set out in the Health (Pricing and Supply of Medical Goods) Act 2013, including the extent of clinical benefit, cost effectiveness, budget impact and available resources. Confidential price negotiations can also take place, which are usually informed by the NCPE appraisal process [11]. In the case of drugs for cancer, the National Cancer Control Programme (NCCP) Technology Review Committee also advises the National Drugs Committee on pertinent criteria, including clinical benefit, disease severity and unmet need.

HTAs, by definition, are tools that help decision making by systematically evaluating properties, effects and/or impacts of health technologies and interventions in order to inform policy, especially on how best to allocate limited funds to health interventions and technologies [16]. In Ireland, the NCPE maintains transparency in the evaluation process and in doing so delivers an independent review of comparative effectiveness and cost effectiveness of the new drug. Summary reviews are available on the NCPE website, with full reviews available to decision makers and payers. Strategies (in the form of managed entry agreements) have been developed in recent years that have helped the decision maker reach a positive decision on financing drugs, for example, patient-access scheme (PAS) agreements. However, the impact of these reimbursement models for products for rare diseases is unknown.

The National Rare Diseases Plan for Ireland 2014–2018 was published in July 2014 [12]. This was a policy framework for the prevention, detection and treatment of rare diseases based on the principles of high-quality care and equity and seeks to be patient focused. A number of recommendations about access to appropriate drugs and technologies were contained in the plan. One key recommendation was that the HSE develop a Rare Diseases Technology Review Committee (RD TRC) that could operate in the drug assessment system in a similar way to that for drugs for cancer established under the NCCP. This RD TRC has now been established.

The number of applicant submissions to the NCPE that pertain to orphan drugs has increased in recent years but has not been explicitly analysed. The aim of this study was to ascertain the number of submissions made to the NCPE that pertained to orphan drugs (from 2012 to 2017 inclusive) and to determine how these drugs proceeded through the NCPE critical evaluation process. In terms of the prevalence, a threshold of 5 cases per 10,000 individuals was used to define ‘orphan drugs’, and 1 case per 50,000 individuals was used to define ‘ultra-orphan drugs’ (informed by the EU definition and NICE, respectively), for the treatment of the indicated rare diseases. Drugs for cancer that also had EMA orphan designation were also included in the analysis. Thus, the aim was to analyse submissions received in three categories: orphan (non-cancer) drugs, orphan (cancer) drugs and ultra-orphan drugs. Specifically, the study was a retrospective analysis to

determine the number of drugs in each category submitted to NCPE from January 2012 to December 2017 inclusive,

determine how these drugs have proceeded through the NCPE evaluation processes and

compare the movement of these orphan drugs with non-orphan drugs in terms of proportions recommended for full HTA after going through the rapid review process.

2 Methods

This was a retrospective analysis of applicant rapid review submissions made to the NCPE from January 2012 to December 2017 inclusive. Drugs were categorised according to the following definitions: orphan (non-cancer) drug, orphan (cancer) drug, ultra-orphan drug and other (i.e. all other pharmaceutical submissions received by the NCPE). Prevalence thresholds of 5 cases per 10,000 individuals [17] and 1 case per 50,000 individuals [18] were used to define ‘orphan drugs’ and ‘ultra-orphan drugs’, respectively. These were validated by the NCPE Technology Review Group for each submission using www.orpha.net. Indication was used to define orphan (cancer) drugs. Drugs in the ‘other‘category were not analysed further as this category has been previously analysed [11].

The number of submissions in each of the three categories outlined above was recorded. In each of the three categories, the outcome of rapid review appraisal and, where relevant, the outcome of the subsequent HTA appraisal was recorded. The outcomes of the rapid review evaluations for orphan drugs versus non-orphan drugs were investigated. Pearson’s Chi squared test was used to determine whether there was a statistically significant difference in the proportion of rapid reviews for which the outcome was ‘HTA recommended’. Analysis was conducted in SPSS Statistics 24.

Explanatory terminology used in NCPE recommendations (Table 1) can be accessed at: http://www.ncpe.ie/submission-process/public-consultation-2/.

3 Results

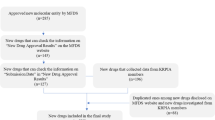

From January 2012 to December 2017 inclusive, 280 rapid review submissions were made to the NCPE, of which 21 were for orphan (non-cancer) drugs, 24 were for orphan (cancer) and ten were for ultra-orphan drugs (Table 2). The movement of submissions through the rapid review process can be seen in Fig. 1, which also depicts the outcome of the rapid review (i.e. requirement for HTA or not).

The drugs for which an HTA was recommended were investigated further. Figures 2, 3 and 4 show the outcomes of the NCPE Review Group’s appraisal of these submissions.

For orphan (non-cancer) drugs (Fig. 2), where a HTA was recommended in six (of 21) cases (29%), the outcome of the HTA was ‘not recommended at the submitted price’ in four cases, indicating that a positive recommendation could be considered if the applicant was willing to negotiate a lower price for the product. In two cases, the outcome of the HTA was ‘not recommended for reimbursement’, indicating that relative clinical benefit was not demonstrated in the submission or the economic evaluation presented was not sufficiently robust to estimate a plausible incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER).

For orphan (cancer) drugs (Fig. 3), where 14 (of 24) drugs (58%) were recommended for HTA, reimbursement was ‘not recommended at the submitted price’ in five cases. Reimbursement was not recommended in eight cases. HTAs had not yet been received in one case at the time of analysis.

For ultra-orphan drugs, where an HTA was recommended in all cases (n = 10), the outcome of the HTA was ‘not recommended at the submitted price’ in three (30%) cases. Similarly, there were five (50%) cases where the outcome of the HTA was ‘not recommended for reimbursement’. At the time of analysis, one product was reimbursed following HTA, subject to the continuing availability of a discounted price. Also, at the time of analysis, one product was going through the HTA appraisal process.

When the outcome of the rapid review process was compared between orphan drugs (31/55) and non-orphan drugs (79/225), a statistically significant difference was detected in the proportion of rapid reviews for which the outcome was ‘HTA recommended’ (Pearson’s Chi-squared test; p = 0.04).

4 Discussion

The European regulation on orphan drugs established in the year 2000 [13] has encouraged the development of therapies for rare diseases, which has in turn led to an increase in the number of authorisations for orphan drugs [14] in Europe [13].

The results of the present study highlight the annually increasing volume of orphan drug submissions received by the NCPE in the 6-year period from 2012 to 2017. After categorising orphan products using the prevalence threshold criteria of 5 cases per 10,000 and 1 case per 50,000 to categorise orphan (non-cancer) drugs and ultra-orphan drugs, respectively, as well as products that are indicated for use in cancer (orphan—cancer), the number of submissions received at rapid review stage was estimated and, where relevant, the outcome (i.e. an NCPE recommendation or non recommendation) of the subsequent HTA was recorded. Overall, ultra-orphan, orphan (non-cancer) and orphan (cancer) products constituted 3.6%, 7.5% and 8.6%, respectively, of rapid reviews received by the NCPE during the 6-year study period. Regarding the outcome of the rapid review process, there was a statistically significant difference in the proportion of orphan drugs going for full HTA, compared with non-orphan drugs during the same time period. This is undoubtedly a reflection of the uncertainty associated with the clinical data (both efficacy and safety) as well as uncertainty around the value (opportunity cost) of the orphan products compared with the non-orphan products.

Indeed, the relevance and suitability of HTA as a decision-making tool for reimbursement of orphan drugs has been the subject of debate for some time now [19]. However, we argue that HTA works best in the decision-making domain when used adjunctively rather than as a driver of decisions. A recent additional step to the reimbursement process for orphan (non-cancer) drugs in Ireland has seen the establishment of an RD TRC. This committee comprises (in the main) clinicians with expertise in rare or highly specialised diseases, pharmacists, HTA expertise, patient representatives and representation from the healthcare payer (i.e. HSE) and the Health Information and Quality Authority (HIQA) [20]. Their remit is to advise the National Drugs Group (of the national health service) on any additional benefit provided by the drug that may not have been captured as part of the HTA process. The committee draws on relevant clinical experts for the specific rare disease as well as patient representatives. It is envisioned that the way in which this committee operates will serve to strengthen the drug reimbursement process for the benefit of patients with rare diseases in Ireland. Future research is needed to determine whether any correlation exists between this committee reviewing an orphan drug and positive recommendations (i.e. access for patients) for orphan drugs.

The annual increase in orphan drug submissions seen in this study concurs with the following global trend: although rare diseases are, by their definition, rare, if examined in their totality, they are in fact numerous. For example, if all the estimated 5000–8000 rare diseases are taken together, 6–8% of the European population will experience a rare disease during their lifetime [21]. Numbers such as these will inevitably place a large impact on public health systems, in terms of not only healthcare resource use but also orphan drug reimbursement. Figures from the USA show that orphan drugs now account for more than one-third of new drugs approved by the FDA, and the number of new orphan designations per year has increased dramatically, from 50 to 100 per year from 1987 to 2003, and to 291 new designations in 2014 [15]. The first issue that this raises from a decision-making point of view relates to the higher prices commanded for orphan drugs—this implies increasing budget impact for payers and raises the question of affordability. From a cost-effectiveness point of view, Jayasundara et al. [22] did not observe any significant differences in point estimates of ICERs for drugs that treat common versus rare cancers in a sample of published cost-utility analyses. Second, the increasing number of orphan indications per year raises concern not only over affordability but more fundamentally over potential bias toward R&D in orphan drugs, to the relative neglect of therapy classes that cannot qualify for orphan drug status, such as dementia or antibiotics.

Our study has several limitations. First, while it may seem that the review was limited to submissions made to the NCPE, the NCPE is in fact the national HTA agency for pharmaceuticals in Ireland. There are also procedural aspects in the Irish system that may be of interest to other jurisdictions, for example, the pragmatic approach adopted in the HTA process. The rapid review process has been particularly beneficial in triaging those products where uncertainty is greatest from those where outcomes are more certain. Second, the number of submissions of products for rare diseases is relatively small. This limitation is probably a reflection of the nature of the diversity in rare diseases and rare diseases research. While the total number of submissions to the NCPE has risen over the 6-year period, there are still relatively few submissions for rare diseases compared with submissions for drugs that treat less rare diseases. Third, prevalence for a disease may vary across different geographic locations both within and across countries. However, to our knowledge, the prevalence figures used for this study are also relevant to Europe.

5 Conclusion

The number of submissions to the NCPE for drugs for rare diseases has increased in recent years, but the numbers are still small in absolute terms when compared with the number of submissions for drugs that treat less rare diseases. The rapid review and HTA process in Ireland plays a beneficial role in supporting the reimbursement decision-making process for all drugs. In particular, our study indicates that a greater proportion of orphan products than non-orphan products were subject to a full HTA, a reflection of where uncertainty is greatest. Future work is needed to decipher how the reimbursement outcome in terms of access to these drugs for patients compares across groups.

References

Office of Inspector General. United States Department of Health and Human Services. The Orphan Drug Act implementation and impact. 2001. http://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-09-00-00380.pdf.

European Medicines Agency. Orphan Designation. 2017. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/overview/orphan-designation-overview. Accessed Feb 2019.

Orphan incentives. European Medicines Agency. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/humanregulatory/research-development/orphan-designation/orphan-incentives. Accessed Mar 2019.

Richter T, Nestler-Parr S, Babela R, Khan ZM, Tesoro T, Molsen E, Hughes DA. Rare disease terminology and definitions—a systematic global review: report of the ISPOR rare disease special interest group. Value Health. 2015;18(6):906–14.

Kanavos P, Nicod E. What is wrong with orphan drug policies? Suggestions for ways forward. Value Health. 2012;15(8):1182–4.

NICE and NHS England consultation on changes to the arrangements for evaluating and funding drugs and other health technologies assessed through NICE’s technology appraisal and highly specialised technologies programmes.: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; March 15 2017.

Scherer FM. The link between gross profitability and pharmaceutical R&D spending. Health Aff. 2001;20(5):216–20.

Van Ekdom L. Price setting orphan drugs-identifying the influential factors on the price setting of orphan drugs. MSc thesis. 2006. http://www.ppge.ufrgs.br/ats/disciplinas/1/vanekdom-2006.pdf.

McCabe C, Claxton K, Tsuchiya A. Orphan drugs and the NHS: should we value rarity? Br Med J. 2005;331(7523):1016

Hawkes N, Cohen D. What makes an orphan drug?. Br Med J (Online). 2010;341:c6459.

McCullagh L, Barry M. The pharmacoeconomic evaluation process in Ireland. PharmacoEconomics. 2016;34(12):1267–76.

National Rare Disease Plan for Ireland 2014–2018 (Dept. of Health, Hawkins House, Dublin 2, Ireland). https://health.gov.ie/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/EditedFile.pdf. Accessed Mar 2019.

Westermark K. European regulation on orphan medicinal products: 10 years of experience and future perspectives. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10(5):341.

Hughes-Wilson W, Palma A, Schuurman A, Simoens S. Paying for the Orphan Drug System: break or bend? Is it time for a new evaluation system for payers in Europe to take account of new rare disease treatments? Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7(1):74.

EvaluatePharma. Orphan Drug Report 2015. http://info.evaluategroup.com/rs/607-YGS-364/images/EPOD15.pdf. Accessed Mar 2019.

World Health Organisation. https://www.who.int/health-technology-assessment/about/Defining/en/ technology assessment/informing decision makers.

European Medicines Agency (EMA) Article 3(1)(a) of Regulation (EC) No 141/2000. Criteria for orphan designation at the time of marketing authorisation.

NICE Citizens council report ultra orphan drugs. 2016 Jul 14; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1885144/pdf/bcp0062-0264.pdf. Accessed Mar 2019.

Drummond MF. Assessing the economic challenges posed by orphan drugs. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2007;23(1):36–42.

Rare Diseases Ireland. Launch of Rare Diseases Technology Review Committee http://rdi.ie/menu/news-and-events/. Accessed Mar 2019.

European Medicines Agency (EMA) Orphan drugs and rare diseases at a glance. 2016 Jul 13; http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Other/2010/01/WC500069805.pdf. Accessed Mar 2019.

Jayasundara K, Krahn M, Mamdani M, et al. Differences in incremental cost-effectiveness ratios for common versus rare conditions: a case from oncology. PharmacoEconomics Open. 2017;1:167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-017-0022-7.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept was conceived and drafted by CU. CU and LMcC performed data analyses, LT and MB reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

CU, LMcC, LT and MB have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Funding

No sources of funding were used to conduct this study or prepare this manuscript.

Data availability statement

All data used in this study can be accessed at http://www.ncpe.ie.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Usher, C., McCullagh, L., Tilson, L. et al. Analysis of Health Technology Assessments of Orphan Drugs in Ireland from 2012 to 2017. PharmacoEconomics Open 3, 583–589 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-019-0136-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-019-0136-1