Abstract

Background

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC), the most aggressive form of lung carcinoma, represents approximately 15% of all lung cancers; however, the economic and healthcare burden of SCLC is not well-defined.

Objective

The aim of this study was to explore the impact of SCLC on healthcare costs through a systematic literature review (SLR).

Methods

Using the OVID search engine, the SLR was conducted in PubMed, MEDLINE In–Process, EMBASE, EconLIT and the National Health Service Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED). Searches were limited to studies published between January 2005 and 24 February 2016, and excluded preclinical studies. Additional internet-based searches were conducted. In total, 229 abstracts were retrieved and systematically screened for eligibility, with 17 publications retained.

Results

The majority of publications provided data on limited and extensive disease of SCLC. The reported burden was categorised as direct costs and indirect costs, with the majority of the publications (n = 16) reporting on direct costs and one reporting on both direct and indirect costs. The only indirect costs reported for SCLC were lost productivity (premature mortality costs) and caregiver burden. Chemotherapy, diagnostic costs and treatment costs were identified as significant costs when managing SCLC patients, including the associated treatment costs such as hospitalisation, nurse visits, emergency room visits, follow-up appointments and outpatient care.

Conclusions

SCLC and its treatment have a substantial impact on costs. The scarcity and heterogeneity of economic cost data negated meaningful cost comparison, highlighting the need for further research. Capturing the economic burden of SCLC may help patients and clinicians make informed treatment choices and improve SCLC management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Chemotherapy and associated costs were identified as major cost components in several publications; costs related to screening methods and administering screening were also high. |

Treatment costs represented a significant proportion of direct costs, specifically small cell lung cancer (SCLC) medication costs or surgical costs, which included high associated costs from hospitalisation, nurse visits, emergency room visits, follow-up appointments and outpatient care. |

Only limited information on the indirect costs of SCLC is available in the published literature (namely, data on productivity loss due to premature death). |

The varied nature of the studies captured indicates that a more uniform and consistent approach is needed when reporting on the costs of SCLC. |

1 Introduction

Lung cancer is the second most prevalent cancer worldwide, with more than one quarter (27%) of all cancer deaths in 2015 attributed to lung cancer [1]. It is a leading cause of cancer mortality, responsible for 1.69 million deaths worldwide in 2015 [2]. As the symptoms associated with lung cancer are often non-specific, it is frequently diagnosed in the late stages; this is reflected in a 5-year survival rate estimated at <20% [3].

SCLC accounts for approximately 15% of all lung cancers and has its highest occurrence in smokers [4]. While representing a comparatively small proportion of lung cancers, SCLC is the most aggressive from of lung cancer, with faster growth and earlier metastasis than any other pulmonary cancer [5]. It is characterised by a rapid doubling time and early onset of dissemination [5]. Although SCLC is initially sensitive to existing forms of chemotherapy, progression occurs rapidly and a high incidence of recurrence has been observed [4, 6]. Surgical resection is the mainstay of treatment for patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), however nearly 70% of patients present with metastatic or locally advanced disease [7]. Compared with NSCLC, curative surgery is rarely an option in SCLC as most patients present with already widely metastatic or locally advanced disease at diagnosis. Untreated patients typically have a median lifespan of 2–4 months following diagnosis [8].

The limited rate of early diagnosis, rapid development of resistance to existing treatment, and low 5-year survival rates present a significant unmet need in the disease area [6]. Although SCLC is only a small subset of total lung cancers, it is still a considerable social, economic and humanistic burden, with close to 30,000 new cases being reported in the US annually [6, 8].

The overarching objective of this systematic literature review (SLR) was to conduct a comprehensive search to synthesise the direct and indirect costs associated with SCLC in Australia, Brazil, Canada, Europe, Japan, Russia and the US. The authors deemed these populous regions to represent various levels of socioeconomic development, across five continents.

Key components and drivers of the economic burden of SCLC were examined across different SCLC patient subpopulations. Economic burden was defined as any direct and indirect costs of SCLC, including diagnosis and treatment costs, loss of work productivity, or costs to caregivers or family members.

2 Methodology

The primary objective of this literature review was to summarise the economic burden of SCLC and to define and understand the key drivers and factors that underpin these impacts. These included social costs (e.g. lost productivity, caregiver burden, absenteeism, presenteeism, out-of-pocket expenses, burden of premature mortality) and healthcare costs (e.g. direct medication costs, primary care costs and secondary care costs, such as hospital admissions). The secondary objectives were to understand how the cost burden associated with SCLC varies across different patient subpopulations, where data allowed. The following subpopulations were examined when analysing the results: smokers and non-smokers; programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) positive and PD-L1 negative; relapse/refractory disease (second-/third-line therapy) and non-advanced (first-line therapy) SCLC; limited- and extensive-stage disease; and brain metastases associated with SCLC. A further exploratory objective investigated in the SLR was the potential to distinguish between ‘disease symptom burden’ and ‘treatment burden’.

A literature search was conducted to identify publications relating to the costs of SCLC. The following computerised bibliographic databases were searched using the OVID search engine for the economic burden SLR: PUBMED (MEDLINE), MEDLINE® In-Process, EMBASE, EconLIT and National Health Service economic evaluation database (NHS EED). The search was limited to studies published in the past 10 years (1 January 2005–24 February 2016) and excluded preclinical studies. To ensure all publications of interest were captured, both English and non-English language publications were included in the search. The search utilised a combination of disease and cost burden subject headings and free-text searching in order to ensure that the most relevant literature was identified and reviewed (see Appendix A).

All abstracts identified in the search were screened for full-publication review by two independent reviewers (MP and RW). Any disagreement was resolved by a third senior researcher (AE). Publications reporting costs associated with patients without specific reference to SCLC, or reporting data on treatment efficacy/interventional data in SCLC, which did not assess the economic burden, were excluded. Publications reporting data for patients <16 years of age, study populations of <30 patients, or publications consisting of letters, editorials or commentaries, as well as publications with no study length restrictions, were also excluded.

Publications were included in the full-text review based on the following inclusion criteria: publications presenting data specific to or including SCLC patient populations in the following geographical regions: Australia, Brazil, Canada, Europe, Japan, Russia or the US; publications reporting the direct or indirect costs associated with the management of SCLC across these countries and regions; and publications presenting data specific to or including patients with SCLC.

All included publications were assessed for quality against an adapted version of the DRUMMOND checklist [9]. Some publications identified through the primary search were abstracts and posters, therefore a full quality assessment was not possible.

As recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration [10], when studies provided sufficient methodological information, cost data were converted to a common currency and year (2016 US$) using a cost converter tool provided by the Campbell and Cochrane Economics Methods Group and the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (see Appendix B) [11].

An additional internet-based search was conducted to identify any further relevant literature. This internet-based search was conducted using a combination of keywords and included both non-peer-reviewed publically available information and peer-reviewed publications that may not yet be indexed in databases such as PUBMED or Embase, because of their recent publication date, or because they were published in journals that are not indexed within these databases. Conference proceedings from the annual European, US, Asia–Pacific and Latin American congresses of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR), the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) annual meeting, the annual European Cancer Congress (ECC), European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) and the annual World Conference on Lung Cancer (WCLC) were reviewed.

3 Results

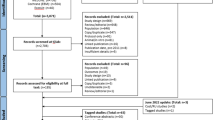

A total of 229 publications were identified: 217 in the OVID search and 12 in the additional internet-based search. As the search retrieved only a small number of publications, indicating a paucity of primary studies on the cost burden of SCLC, it was decided that the review should also capture secondary evidence such as economic modelling studies, if these presented evidence on the costs of the disease. Primary references within existing systematic reviews were also examined to identify further relevant data, even if these primary sources were not captured directly by this search.

Following abstract screening and full-text review, a total of 12 full-text publications from the OVID search [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25] were taken forward for inclusion in the SLR (Fig. 1). OVID searching identified four conference abstracts and one poster that were relevant in the context of this review, however full-text publications could not be sourced [26,27,28]. These publications will be referred to as ‘grey literature’ throughout this manuscript. As there was a paucity of publications identified on the cost burden of SCLC, these grey literature sources were included in the final SLR, resulting in a total of 17 inclusions [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28].

No further publications were retained from the search of internet-based sources (such as disease-specific and patient advocacy websites and conference proceedings from ISPOR, ASCO, ECC, ESMO and the WCLC), as the 12 conference abstracts identified did not provide data specific to SCLC and costs [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40].

The number of publications identified and the type of publications included in the SLR are presented in Fig. 2. Three literature reviews were included in this review as they undertook economic evaluations of SCLC costs; however, the primary publications reported in these reviews did not report SCLC-specific costs and were therefore not included in the review [15, 19, 21].

The publications were grouped based on the costs reported in direct and indirect costs.

The majority of publications reported on direct costs (n = 16) and only one publication reported on both direct and indirect costs (n = 1). Further details of publications included within the SLR are presented in Table 1.

3.1 Quality Assessment

To assess the quality of all included publications, an adapted DRUMMOND checklist for economic evaluation quality assessment was used [9]. The assessment included three aspects (study design, data collection, and analysis and interpretation of results) and a total of 36 criteria. Each publication was independently assessed for quality by two researchers and given a score of 0 = not reported, 1 = not clear, or 2 = reported (or NA if not applicable). Scores were then summed and a percentage given for each publication from the number of questions that were applicable to that publication.

For example, a publication may have information reported for five items (equating to 10 points), not reported for three items (=0 points), not clear for three items (=3 points) and not applicable for two items, totalling 13 points. In this case, the total number of applicable items (items that score 0, 1, or 2) is 11, and hence the total number of possible points is 22; therefore, the publication’s final quality score is 59% [(13÷22) × 100].

The assessed publications received a high-quality score, ranging from 73.1 to 91.7% (see Table 2). Four publications could not be assessed in this way as they were abstracts or posters only and therefore could not be scored [22, 26,27,28]. However, due to the paucity of data retrieved from the primary search, these publications were included in the final SLR.

3.2 Direct Costs

The direct costs of SCLC were reported in 17 studies. The research focus varied across publications and different cost items were reported, as described in Table 1.

Direct cost components were chosen arbitrarily by the authors on the basis of their respective objective, and could not be compared. This was indicative of the paucity of data found on SCLC costs and the varied nature of how they were reported. Several direct cost components were identified as potential cost drivers for the economic burden of SCLC. Chemotherapy and associated costs were identified as major cost components in five publications [12,13,14, 16, 26]. Diagnostic costs were high in SCLC, including costs of computed tomography, positron emission tomography (PET), chest x-ray, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), cytohistology, bone scans and screening administration [12, 16, 18, 20, 21, 28]. Treatment costs represented a significant proportion of direct costs, specifically SCLC medication costs or surgical costs, which included high associated treatment costs, such as hospitalisation, nurse visits, emergency room visits, follow-up appointments, and inpatient and outpatient care [12, 16, 17, 20, 23, 25, 27].

Several publications investigated cost components of lung cancer [12, 13, 16, 27]. In Turkey, the mean total cost per lung cancer patient was reported by Cakir and Karlikaya as $14,306 (USD, cost year not specified), and the median total cost per patient was reported by Turk et al. as €910 (€, cost year not specified) [12, 27]. High costs were reported in treatment and inpatient services in Turkey, as well as direct medical costs (Table 3) [12]. Costs in the US were $896.73 per chemotherapy visit or $10,760.85 per course of treatment (Table 4) [13]. In Australia, the median cost per month of survival for all lung cancer (SCLC and NSCLC) patients was AU$1854 (AU$, review of patient records 2005–2008, applying 2005 Australian Medicare Benefits Schedule costings, adjusted to 2016 US$) [16]. Hospitalisation and chemotherapy were the highest direct costs reported (see Table 5) [16].

Chemotherapy costs were also a major component of lung cancer costs [12, 27]. Intravenous chemotherapy administration and other visit-related drugs and services accounted for nearly half of the total cost per intravenous visit day in one study [13]. A substantial economic burden on patients with extensive-stage SCLC and NSCLC was observed in the US (see Table 6) [17]. The primary drivers of costs were hospitalisation, office visits, and hospital outpatient visits, and chemotherapy use was significantly more prevalent in SCLC compared with NSCLC [17].

In Italy, the economic impact of patients enrolling in sponsored clinical trials on national healthcare spending was examined [14]. The costs of chemotherapy agents were reported to be high and the enrolment of 44 patients in sponsored clinical trials produced a saving of 30% of the pharmaceutical expenses for antineoplastic agents, however no specific cost data were reported [14].

In Japan, median hospital length of stay was longer for SCLC (20 days) than NSCLC (18 days) patients, and total charges (US$, cost year not specified) differed significantly between SCLC ($6015) and NSCLC patients ($6993) [18]. A review investigated PET-based staging for SCLC in Australia, reporting its cost to be AU$1189.10 per patient, compared with conventional staging costs of AU$1194.29 (2010 Australian Medicare Benefits Schedule costings, adjusted to 2016 US$) [21]. The costs of SCLC and NSCLC management were investigated in Australia, where the costs of managing NSCLC and SCLC were found to be comparable [16].

3.2.1 Direct Costs of Limited- and Extensive-Stage Small Cell Lung Cancer (SCLC)

Several publications reported on direct costs of extensive-stage SCLC specifically [12, 15,16,17,18,19, 21, 22, 25, 27]. Kang et al. investigated the costs of SCLC management and found that the median cost of lung cancer in Australia was highest for limited-stage SCLC ($19,046 vs. $12,688 for extensive-stage) [AU$, review of patient records 2005–2008, applying 2005 Australian Medicare Benefits Schedule costings, adjusted to 2016 US$]. Patients with extensive-stage SCLC had the highest proportion of their management costs spent on hospitalisation (see Table 5) [16].

Turk et al. examined the diagnosis costs of SCLC patients hospitalised in Turkey (€, cost year not specified) and reported the total cost of diagnosis per patient as €937 in limited-stage SCLC and €502 in extensive-stage SCLC [27]. Furthermore, Patrice et al. found that the addition of thoracic radiation therapy to prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI) in extensive-stage SCLC patients in the US resulted in a $4066 cost increase (US$, cost year not specified) [26].

Karve et al. reported on healthcare costs per patient for extensive-stage SCLC and metastatic NSCLC in the US (US$, cost year not specified). In both the SCLC and NSCLC cohorts, hospitalisation was the predominant cost driver, accounting for approximately half of all costs (see Table 6). SCLC disease-related costs were a larger percentage of total (all-cause) costs compared with NSCLC (62.6% vs. 56.4%) [17].

Seven other publications reported on extensive- and limited-stage SCLC, however the costs reported were not separated by extensive and limited SCLC [12, 15, 18, 19, 21, 22, 25].

3.2.2 Direct Costs of Prophylactic Therapies

Prophylactic therapy costs were reported frequently, with two modelling and one observational publication reporting on the direct costs of multiple prophylactic therapies, or presenting mean costs of prophylactic therapy [22,23,24]. Timmer-Bonte et al. investigated the economic burden of secondary prophylactic use of different prophylactic strategies in extensive-stage SCLC patients at risk of febrile neutropenia in The Netherlands and found that the most expensive strategy was antibiotics plus granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), with a mean cost of $13,338 per patient (converted from 2002 € to 2016 US$; original cost year derived from a further publication on the same study, cited within the captured publication) [41] (Table 7). The relatively high price of administering G-CSF was the determining cost factor [24].

In France, the economic implications of using pegfilgrastim to prevent febrile neutropenia induced by chemotherapy in SCLC were explored [23]. The difference in the costs of preventing and managing febrile neutropenia between the two strategies was €1743 for the pegfilgrastim strategy and €1466 for the G-CSF strategy (€, cost years not consistently reported). Pegfilgrastim was more costly than first-generation G-CSF; however, concern about the excess cost may be reduced by the perceived convenience of the pegfilgrastim strategy [23].

The cost of PCI with hippocampal avoidance was reported as $13,377.61 versus $6388.28 for PCI in limited-stage SCLC patients in the US (Medicare’s 2014 reimbursement rate adjusted to 2016 US$) [22].

3.2.3 Direct Costs of Bone Metastatic Disease

As part of the secondary objectives of this SLR, the costs of bone metastasis were investigated. A French prospective, observational study reported on bone metastasis in SCLC [25]. The total cost of bone metastatic disease for both SCLC and NSCLC was €1,715,213 (cost year not specified) for the entire cohort of patients (n = 554) [25]. The mean management cost during the first year after onset was €3999, of which 49.5% was linked to the management of patients with skeletal-related events. Metastatic bone disease presented a significant driver of oncology costs, with skeletal-related events being the most burdensome cost of bone metastatic disease management [25].

3.2.4 Cost of SCLC by Subpopulations

The economic burden of disease in different SCLC subgroups was also explored in this review. Due to the diverse study designs of publications presenting smoking and non-smoking populations, comparisons could not be made on any variation in cost between these subpopulations.

The costs of SCLC staging were investigated in two publications, with Kang et al. presenting cost differences between each stage of SCLC in Australia [16], while Karve et al. reported on the most used first-, second- and third-line treatments in extensive SCLC in US [17]. Kang et al. reported that the median total cost increased along with progressing stage for NSCLC and SCLC, with the median total cost for limited SCLC reported as AU$20,826, and AU$13,874 for extensive-stage SCLC (AU$, review of patient records 2005–2008, applying 2005 Australian Medicare Benefits Schedule costings, adjusted to 2016 US$). The median cost per patient was highest for limited-stage SCLC (see Table 5), while the median cost per month of survival for all lung cancer (SCLC and NSCLC) patients was AU$1854 [16]. Hospitalisation and chemotherapy were the greatest components of cost, representing 44 and 22% of total costs, respectively. Overall, the total costs of managing SCLC and NSCLC were comparable [16].

Karve et al. also reported on high hospitalisation costs in both the extensive-stage SCLC and metastatic NSCLC cohorts, accounting for approximately half of all costs [17]. Chemotherapy use was significantly more prevalent in extensive-stage SCLC compared with metastatic NSCLC, while surgery and radiation therapy were more prevalent in metastatic NSCLC. Utilisation of haematopoietic growth factors and some supportive care therapies were significantly higher in extensive-stage SCLC patients, however the authors did not explore the reasons for this [17].

Two publications reported on patients with brain metastases but did not present separate costs for patients with these metastases, therefore no conclusions could be drawn [19, 22]. The lack of information on the costs of brain metastases in SCLC highlights this as a crucial area where more research is needed.

3.2.5 Symptom Burden versus Treatment Burden

Despite the systematic nature of this review, no publications were found that distinguished between symptom and treatment burden directly, therefore no conclusions could be drawn.

3.3 Indirect Costs

Indirect SCLC costs, such as lost productivity (e.g. absenteeism), care costs (indirect costs associated with caring and house work), out-of-pocket expenses, income foregone due to illness-related early retirement, and presenteeism were investigated in this SLR. The i ndirect costs of SCLC were captured in a single publication by Cakir and Karlikaya and included lost productivity due to premature death (total $866,870; US$, cost data not specified; 59% of total lung cancer costs) [12]. This study found that the indirect costs experienced by patients in Turkey varied widely, ranging from $500 to $99,000 [12]. Indirect costs were high in relation to the total costs presented, however these costs were not compared with indirect costs of other cancers [12]. Work productivity was the only indirect cost component reported for SCLC patients, highlighting the need for more studies in this area.

4 Discussion and Conclusions

The publications included within this SLR varied widely in methodology, patient characteristics (e.g. age, proportion of male patients, cancer stage), analytical methods, type of reported costs (costs associated with, for example, diagnosis, surgery, treatment), and cost components (e.g. inpatient costs, outpatient costs, administration). Publications also varied by region of interest, including studies conducted in Europe [12, 14, 15, 19, 20, 23,24,25, 27], North America [13, 17, 22, 26], Oceania [16, 21], and Asia [18].

The majority of identified publications were observational studies (n = 10), followed by modelling studies (n = 4) and SLRs (n = 3). Most publications (9/17) reported data for both SCLC and NSCLC patients, while only eight studies reported on SCLC patients only [13, 15, 19, 21,22,23, 25, 26]. Generally, SCLC patients were the minority of lung cancer patients, while NSCLC patients were the majority, results that are aligned with the general population of lung cancer patients [42]. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first SLR of the economic burden of SCLC and the results summarised here will contribute significantly to the understanding of the true magnitude of costs associated with SCLC. The varied nature of the studies captured indicates the need for a uniform and consistent approach when reporting on costs of SCLC, as well as a clear need for more research in this field.

It must be noted that the authors of the identified publications based the reported costs (e.g. costs associated with diagnosis, surgery, treatment, hospitalisation) on different sources, such as published literature, databases, operative unit reviews and individual hospital data. They also used different currencies, and the cost components (e.g. inpatient costs, outpatient costs, administration) contributing to reported total costs varied widely and were chosen arbitrarily by the authors of the identified publications, in accordance with the research questions the research was trying to address. To this end, the data included in this review are very heterogeneous in type and magnitude, making direct comparison and conclusions challenging.

In comparison to a systematic review previously conducted on NSCLC, there were very limited data on the indirect costs of SCLC [43]. The only indirect costs of SCLC captured were lost productivity due to premature death [12]. The most commonly reported indirect cost in NSCLC was lost productivity, along with caregiver burden, although only five papers reported on indirect costs in that review [43]. As information on indirect costs of SCLC was scarce in the peer-reviewed literature, grey literature sources were identified to augment the findings of the SLR. Increased caregiver work and activity impairment in lung cancer were reported in conference proceedings [29], and a high economic burden of lung cancer illness was also reported [39]; however, none of these additional findings investigated SCLC directly, providing only limited information for this literature review.

Direct costs, including drug costs and cost of hospital admissions, were the most commonly reported costs for both NSCLC and SCLC (n = 17). Many publications included in this SLR reported on general lung cancer costs that included SCLC (9/17), but the proportion of SCLC patients was not always reported, creating uncertainty about the relevance of the data. Due to the heterogeneity and limited availability of the economic burden of SCLC data, the results from this systematic review and grey literature search have been presented as a narrative synthesis, without any direct comparisons made.

A secondary objective of the SLR was to identify whether any differences exist between patient subpopulations. The following patient subpopulations were reported in the publications included within this review: smokers and non-smokers [20, 28], SCLC-stage costs [16, 17] and brain metastases [19, 22], and SCLC versus NSCLC [16,17,18, 27]. However, due to the heterogeneity of costs reported, no conclusive evidence for how costs vary between these subpopulations could be provided. The SLR found no published data on the PD-L1 subgroup in SCLC. While PD-L1 expression strongly correlates with benefit for patients with NSCLC, there is a lower prevalence of PD-L1 expression in SCLC, which is likely the reason for the paucity of data found in this SLR [44,45,46]. A larger population analysis is required to establish whether PD-L1 expression correlates with benefits in SCLC [44].

4.1 Limitations

Certain limitations were noted during the course of this SLR. The broad research question of the SLR resulted in the identification of publications reporting a disparity of cost aspects related to SCLC disease diagnosis and management. Differences in study design, study objective and methodology increased heterogeneity in data reporting, and, as a result, no quantitative analysis, such as a meta-analysis, could be performed.

Additionally, only a minority of the studies provided sufficient information to allow their cost results to be converted to a fixed price-year, as is recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration [10]. The majority of studies providing relevant cost data were not eligible for conversion: six studies stated when resource use had been captured, but failed to provide the year of costing information [12, 17, 18, 23, 25, 27], and one provided neither of these [26]. This limitation identified within the captured studies therefore extends to this review, increasing the difficulty of comparing between studies.

The time horizon of the literature search was 10 years and publications reporting on cost analyses performed in 2005 or after were included. However, it is important to note that some of these publications include patient or disease management data collated prior to 2005. Whether data presented in this report can be extrapolated to the wider SCLC patient population in Australia, Brazil, Canada, Europe, Japan, Russia and the US would require further research.

A key step of the systematic review process is to ensure all publications included within the final analysis and reports are assessed for quality. In light of this, each publication was assessed for quality against an adapted version of the DRUMMOND checklist, which has been developed for the purpose of assessing the quality of economic evaluations [9]. This checklist was used as it was perceived as being the only published quality control guidance applicable to the objectives of this review; however, it was not directly relevant to all publications reviewed. In this capacity, the DRUMMOND checklist was of limited application to some publications reviewed (some publications were abstracts or posters and presented limited information, i.e. no full justification of the methods etc., and some checklist questions were specific to modelling studies and were therefore not applicable to all types of publications).

Several non-peer-reviewed publications were included in this review as grey literature with the aim of augmenting the findings of this SLR, particularly with regard to the economic burden, which could have limited validity [17, 22, 26,27,28]. In addition to this, the inclusion of secondary sources, such as economic models and literature reviews, within this review may reduce its validity [47].

4.2 Summary of Results

In conclusion, the publications included within this review assessed the economic burden and/or indirect and direct costs of SCLC in Australia, Brazil, Canada, Europe, Japan, Russia and the US. Generally, there was a paucity of publications identified in this review reporting on economic burden and indirect costs, indicating a severe lack of research in this area. SCLC accounts for approximately 15% of all lung cancers, however few publications report on its economic burden compared with NSCLC [4, 43]. When reported, economic burden and indirect costs were high in relation to the total costs presented [12]. Despite the direct costs being reported in numerous publications identified within this review, the costs reported were diverse, ranging from costs of diagnosis to costs for specific treatments and cost comparison analyses [27]. In addition, the way in which costs were evaluated/analysed and reported varied, making direct comparisons difficult to conduct. Although diverse, all direct cost publications reported high direct costs in the context of the total costs associated with SCLC.

This review found that only a limited number of publications provided sufficient context for costs to be converted, and reinforces the finding that the available cost data in SCLC are diverse, both in magnitude and the treatments or resources for which they are available. Further research into the cost of SCLC is recommended, along with improved reporting to allow comparability.

References

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(1):5–29.

World Health Organization. Cancer—fact sheet, February 2017. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en/. Accessed 12 Apr 2017.

National Cancer Institute. Cancer Stat Facts: Lung and Bronchus Cancer Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/lungb.html. Accessed 11 Apr 2017.

Gorman G. New and emerging strategies for the treatment of small cell lung cancer. J Pharm Sci Emerg Drugs. 2012;1(1):1–2.

Abidin A, Garassino M, Califano R, Harle A, Blackhall F. Targeted therapies in small cell lung cancer: a review. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2010;2(1):25–37.

National Cancer Institute. Small cell lung cancer treatment—for health professionals. 2016; http://www.cancer.gov/types/lung/hp/small-cell-lung-treatment-pdq. Accessed 26 Apr 2016.

Molina JR, Yang P, Cassivi SD, Schild SE, Adjei AA. Non-small cell lung cancer: epidemiology, risk factors, treatment, and survivorship. In: Paper presented at Mayo Clinic Proceedings; 2008.

Behera M, Ragin C, Kim S, Pillai R, Chen Z, Steuer CE, et al. Trends, predictors, and impact of systemic chemotherapy in small cell lung cancer patients between 1985 and 2005. Cancer. 2015;122(1):50–60.

Drummond M, Jefferson T. Guidelines for authors and peer reviewers of economic submissions to the BMJ. The BMJ Economic Evaluation Working Party. BMJ. 1996;313(7052):275–83.

Shemilt I, Mugford M, Byford S, Drummond M, Eisenstein E, Knapp M, et al. 15.6.1 Presenting results in tables. Cochraine Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Version 5.1.0. 2011. http://handbook.cochrane.org/chapter_15/15_incorporating_economics_evidence.htm. Accessed 6 Apr 2017.

CCEMG-EPPI-Centre. CCEMG—EPPI-Centre Cost Converter 2016. https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/costconversion/. Accessed 6 Apr 2017.

Cakir Edis E, Karlikaya C. The cost of lung cancer in Turkey. Tuberkuloz ve Toraks. 2007;55(1):51–8.

Duh MS, Reynolds Weiner J, Lefebvre P, Neary M, Skarin AT. Costs associated with intravenous chemotherapy administration in patients with small cell lung cancer: a retrospective claims database analysis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(4):967–74.

Grossi F, Genova C, Gaitan ND, Dal Bello MG, Rijavec E, Barletta G, et al. Free drugs in clinical trials and their potential cost saving impact on the national health service: a retrospective cost analysis in italy. Lung Cancer. 2013;81(2):236–40.

Hartwell D, Jones J, Loveman E, Harris P, Clegg A, Bird A. Topotecan for relapsed small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Cancer Treat Rev. 2011;37(3):242–9.

Kang S, Koh ES, Vinod SK, Jalaludin B. Cost analysis of lung cancer management in South Western Sydney. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2012;56(2):235–41.

Karve SJ, Price GL, Davis KL, Pohl GM, Smyth EN, Bowman L. Comparison of demographics, treatment patterns, health care utilization, and costs among elderly patients with extensive-stage small cell and metastatic non-small cell lung cancers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:555.

Kuwabara K, Matsuda S, Fushimi K, Anan M, Ishikawa KB, Horiguchi H, et al. Differences in practice patterns and costs between small cell and non-small cell lung cancer patients in Japan. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2009;217(1):29–35.

Loveman E, Jones J, Hartwell D, Bird A, Harris P, Welch K, et al. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of topotecan for small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2010;14(19):1–220.

Pertile P, Poli A, Dominioni L, Rotolo N, Nardecchia E, Castiglioni M, et al. Is chest X-ray screening for lung cancer in smokers cost-effective? Evidence from a population-based study in Italy. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2015;13:15.

Ruben JD, Ball DL. The efficacy of PET staging for small-cell lung cancer: a systematic review and cost analysis in the Australian setting. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7(6):1015–20.

Louie AV, Qu MX, Bauman GS, Slotman BJ, Mehta MP, Gondi V, et al. Cost-effectiveness of prophylactic cranial irradiation with hippocampal avoidance in limited stage small cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;1:S92.

Tan Sean P, Chouaid C, Hettler D, Baud M, Hejblum G, Tilleul P. Economic implications of using pegfilgrastim rather than conventional G-CSF to prevent neutropenia during small-cell lung cancer chemotherapy. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25(6):1455–60.

Timmer-Bonte JNH, Adang EMM, Termeer E, Severens JL, Tjan-Heijnen VCG. Modeling the cost effectiveness of secondary febrile neutropenia prophylaxis during standard-dose chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(2):290–6.

Decroisette C, Monnet I, Berard H, Quere G, Le Caer H, Bota S, et al. Epidemiology and treatment costs of bone metastases from lung cancer: a French prospective, observational, multicenter study (GFPC 0601). J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6(3):576–82.

Patrice GI, Patrice SJ, Lester-Coll NH, Yu JB. Exploring the cost-effectiveness of thoracic radiation therapy in extensive-stage small cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;1:S92.

Turk M, Yildirim F, Yurdakul AS, Ozturk C. Hospitalization costs of lung cancer diagnosis in Turkey: Is there a difference between histological types and stages? Tuberk Toraks. 2016;64(4):263–8.

Weycker D, Boyle P, Lopez A, Jett JR, Detterbeck F, Kennedy TC, et al. Cost-effectiveness of screening older adult smokers for lung cancer with an autoantibody test (AABT). Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:A2937.

Goren A, Gilloteau I, Penrod J, Jassem J. Assessing the burden of caregiving for patients with lung cancer in Europe. Value Health. 2013;16(7):A403.

Fritschel E, Wang L, Li L, Zhang J, Baser O. An assessment of clinical and economic outcomes of U.S. veteran lung cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(suppl. 15):e19122–e19122.

Newcomer L (ed). Cost and duration of illness for lung cancer in national payer database. In: American society of clinical oncology annual meeting; 2010.

Rogalewicz V, Šimrová J, Vojtíšek R, Barták M (eds). The analysis of costs and reimbursements for lung cancer treatment in the Czech Republic. Value Health. 2013;16(7):A407.

Mahar A, Fong R, Johnson A. The economic impact of treating early lung cancer: a systematic review. Value Health. 2011;14(7):A440.

Ramsey S, Henk H, Sullivan J, Teitelbaum A, Akhras K, Sollano J, et al. First and second line lung cancer treatment utilization patterns and associated costs in a United States health care claims database. Value Health. 2011;14(7):A442–3.

Raymakers A, Whitehurst D, FtizGerald J, Lam S, Mayo J, Lynd L. Cost-effectiveness analyses of lung cancer screening strategies using low dose computed tomography: a systematic review. Value Health. 2015;18(3):A46.

Patel B, Kamal K, Atreja N. Inpatient resource utilization in bronchial and lung cancer: analysis of 2007 healthcare utilization and project (HCUP) data. Value Health. 2010;13(3):A43.

Ferreira C, Santana C, Rufino C, Paloni E, Campi F. Economic burden of lung cancer from a private healthcare system perspective in Brazil. Value Health. 2015;18(3):A195.

Roth J, Sullivan S, Ravelo A, Sanderson J, Ramsey S. Projected clinical, resource, and budget impact of implementing low-dose computed tomography lung cancer screening in the United States. Value Health. 2014;17(3):A75–6.

Nadpara P, Tworek C, Madhavan S. The cost of treating lung cancer in the United States: an analysis of the medical expenditure panel survey. Value Health. 2010;13(3):A48.

Stefani S, Brandalise P. Use of health resources in lung cancer patients: a Brazilian analysis in the private payer perspective. Value Health. 2008;11(3):A57–8.

Timmer-Bonte JN, Adang EM, Smit HJ, Biesma B, Wilschut FA, Bootsma GP, et al. Cost-effectiveness of adding granulocyte colony-stimulating factor to primary prophylaxis with antibiotics in small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(19):2991–7.

Cancer.org. What is small cell lung cancer? http://www.cancer.org/cancer/lungcancer-smallcell/detailedguide/small-cell-lung-cancer-what-is-small-cell-lung-cancer. Accessed 26 Apr 2016.

Enstone A, Panter C, Manley Daumont M, Miles R. Societal burden and impact on health related quality of life (HRQoL) of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Value Health. 2015;18(7):A690.

Antonia SJ, López-Martin JA, Bendell J, Ott PA, Taylor M, Eder JP, et al. Nivolumab alone and nivolumab plus ipilimumab in recurrent small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 032): a multicentre, open-label, phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(7):883–95.

Grigg C, Rizivi NA. PD-L1 biomarker testing for non-small cell lung cancer: truth or fiction? J Immunother Cancer. 2016;4:48.

Hellmann MD. Using PD-L1 expression for lung cancer treatment planning. Cure. 2016. http://www.curetoday.com/articles/using-pdl1-expression-for-lung-cancer-treatment-planning. Accessed 6 Apr 2017.

Schünemann HJ OA, Vist GE, Higgins JPT,Deeks JJ, Glasziou P, Guyatt GH. 12.2.2 Factors that decrease the quality level of a body of evidence. Cochraine Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Version 5.1.0. 2011. http://handbook.cochrane.org/chapter_15/15_incorporating_economics_evidence.htm. Accessed 6 Apr 2017.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable. All data used in this SLR are derived from published studies and are thus already available.

Funding

Financial support for this research was provided by Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS).

Conflict of Interest

Penrod J. and Yuan Y. are employees of BMS. Enstone A., Greaney M., Povsic M., Wyn R.are employees of Adelphi Values, who received a consulting fee from BMS to undertake this work. The authors have no other conflicts of interest. Preliminary results of this SLR have been presented as a poster at the ISPOR 19th Annual European Congress, Vienna, Austria, 29 October–2 November 2016. Enstone A., Greaney M., Povsic M., Wyn R., Penrod J.R. and Yuan Y. acknowledge that they contributed to all of the following aspects of the work: conception and planning of the work that led to the manuscript or acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data, or both; drafting and/or critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; and approval of the final submitted version of the manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Enstone, A., Greaney, M., Povsic, M. et al. The Economic Burden of Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Systematic Review of the Literature. PharmacoEconomics Open 2, 125–139 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-017-0045-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-017-0045-0