Abstract

The article offers a large-scope assessment of archaeological and ethnoarchaeological research on foodways within the core Mediterranean heartlands of the Ottoman Empire. It integrates evidence from a range of historical and archaeological sources, both terrestrial and underwater. After presenting an overview of 30 years of scholarship on the subject, it introduces the Ottoman manner of eating, cooking, and dining with the help of glazed tablewares and unglazed coarse wares from archaeological contexts. Furthermore, it shows the means of transportation and the trade routes for foodstuffs, as well as the ways in which they were cooked and consumed, from the sultan’s court to country folk in rural villages.

Resumen

En el artículo se ofrece una evaluación de gran alcance de la investigación arqueológica y etnoarqueológica sobre las vías alimentarias en el corazón mediterráneo del Imperio Otomano. Se incluyen evidencias de una variedad de fuentes históricas y arqueológicas, tanto terrestres como submarinas. Después de presentar una descripción general de 30 años de estudios sobre el tema, se aborda la manera otomana de comer, cocinar y cenar con la ayuda de vajillas vidriadas y artículos toscos sin vidriar de contextos arqueológicos. Además, se muestran los medios de transporte y las rutas comerciales para los productos alimenticios, así como las formas en que se cocinaban y consumían, desde la corte del sultán hasta los campesinos de las aldeas rurales.

Résumé

L'article propose une évaluation de grande ampleur de la recherche archéologique et ethno-archéologique sur les pratiques alimentaires au cœur des centres principaux méditerranéens de l'Empire Ottoman. Il incorpore des indices tirés d'un éventail de sources historiques et archéologiques, tant de nature terrestre que sous-marine. Suite à la présentation d'un aperçu général de la recherche accomplie sur ce thème depuis 30 ans, il expose la manière ottomane de manger, de cuisiner et de se restaurer à l'aide d'objets de vaisselle vernissée et d'ustensiles grossiers non vernis provenant de contextes archéologiques. En outre, il décrit les moyens de transport et les routes commerciales des denrées alimentaires, ainsi que les façons dont elles étaient cuisinées et consommées, de la cour du sultan aux paysans dans les villages ruraux.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It is probably an understatement to suggest that food has always been, and will always be, the key aspect of human life. “Dis-moi ce que tu manges, je te dirai ce que tu es” (Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you what you are), wrote the French politician and gastronome Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin in 1826 for good reason, although he was overtaken in brevity 40 years later by Ludwig Feuerbach's diagnosis: “Der Mensch ist, was er ißt” (Man is what he eats) (Brillat-Savarin 1826; Feuerbach 1866:3). Very recently the World Economic Forum endorsed this perspective by concluding: “The history of food is the history of human development” (Broom 2020).

However, beyond this wisdom awaits the work, namely the task of writing such a history of food. It is my intention to present here an overview of Ottoman foodways in the Eastern Mediterranean from an archaeological perspective, with an emphasis on certain ceramics used for consumptive practices and for food processing in the Ottoman Empire.Footnote 1 This Islamic empire existed between ca. 1300 and 1923, starting with Osman I (1258–1323/4), the founder of the Ottoman dynasty, and ending on 1 November 1922, when the Turkish provisional government formally declared the Ottoman Sultanate and Empire to be abolished. Between the 16th and 18th centuries the empire experienced its heyday, including the introduction of a plantation economy and of new crops (tobacco, coffee, sugar, and maize), as well as of the impact of all this on material culture and daily life in the Ottoman territories; see, e.g., Faroqhi (1984) and Singer (2011).

As foodways are a vital part of daily life, changes in the material culture related to food consumption and food preparation indicate developments in a wider socioeconomic context, both for the elites and for all other strata in a society. This is precisely where archaeology has the potential to offer crucial contributions to the understanding of Ottoman foodways in particular and daily life in the empire in general. As pottery is the most durable and omnipresent artifact found on Mediterranean sites of any historical period, changes in its forms and technology offer information about changing patterns of human behavior in the past. In other words, pottery may provide answers to questions about what, where, and how certain foodstuffs were consumed in the Eastern Mediterranean during Ottoman times, as well as to questions about the processes of consumer choice and when new preparation techniques and related new ceramic shapes for food processing were introduced.

This article is based on research carried out on Ottoman foodways in general, covering the period between the 15th and the early 20th centuries. Evidently, this is a vast and complex subject of which I can present here only a first survey of the archaeological data and an indication of possibilities for further research. So, after a concise introduction of Ottoman foodways, the focus is on several selected topics and a case study to illustrate the ways in which archaeology can shed light on what ordinary and elite people were eating and drinking during Ottoman times and what they maintained and changed in their diets over time. One of the subjects is the preference for and the availability of certain food products, as well as the appearance of new consumption habits and changing dining practices in multiethnic Ottoman society. Another subject is shipwrecks and their cargoes as time capsules and sources of information that tell the story of maritime food trade and the movement of foodstuffs within the Ottoman Empire and beyond. Furthermore, the spread of new cooking techniques will be explored in relation to excavated ceramic utensils for food processing in urban and rural contexts in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East.

Finally, a case study addressing foodways in a peripheral region in the Ottoman Empire is discussed. It concerns ethnoarchaeological fieldwork in Aetolia, an isolated mountain landscape in central Greece, where time and technology seem to have stopped between the early Middle Ages and the 1950s. Based on village interviews conducted in the 1980s and 1990s, the focus is on the longue durée genre de vie, including use of food networks, domestic utensils, and culinary dishes in small rural communities in this region during early modern times. The results of these interviews are combined with information from ethnographic research carried out in Aetolia in the early 20th century on the intraregional exchange of traditional foodways seemingly not influenced by modernization processes in Greece, as well as with archaeological data from an extensive survey carried out 50 years later.

Ottoman Foodways: A Survey of Prior Research

In the past 30 years, there has been a considerable interest in food consumption within the Ottoman Empire, which has resulted in an explosion of Ottoman food studies in both academic and popular literature (Reindl-Kiel 1993, 1995, 2003; Arsel 1996; Kadioğlu Çevik 2000; Yerasimos 2005; Gürsoy 2006; Faroqhi 2009). However, these publications are often written from a strictly historical perspective and almost exclusively based on written texts. Also, the focus is predominantly inward-looking, ignoring consequential influences from abroad. Compared to the extensive discussion on the “Columbian Exchange,”Footnote 2 research on the “Trans-Eurasian Exchange” with respect to the movement of crops and livestock to Ottoman territories is still less developed (Boivin et al. 2012; Laudan 2013). In any discussion about Ottoman foodways it is essential to keep in mind that certain crops (such as rice, sugar, and exotic fruits from Asia, or corn, potatoes, and tomatoes from the Americas) moved across continents between East and West, shaping new diets, improving agricultural products, and resulting in the creation of new landscapes and agricultural estates (çiftliks) within the Ottoman Empire in order to facilitate these new tastes (Watson 1983; Given 2000; Van der Veen 2011; Vroom 2020b).

On a more regional scale, the study of tax registers (tahrir defters) provides valuable information on the production and consumption of certain food products in towns and villages under Ottoman rule (Faroqhi 1977; Kiel 1997). Also, interesting ethnographic and sociological studies of rural settlements in the Ottoman Empire have been carried out based both on archival documents and oral history (S. Bommeljé et al. 1987; Ionas 2000; Ziadeh-Seely 2000). For instance, not only were traditional village and domestic architectural forms (single-story longhouses for country folk) explored in Ottoman central Greece (Stedman 1996), but also the changing function of an Ottoman farmstead (qasr) in Jordan (Carroll et al. 2006). Furthermore, the network of Ottoman inns (khans) providing accommodation and food to travelers was mapped together with land routes and bridges in the Greek Pindos Mountains (Y. Bommeljé and Doorn 1996).

Of relevance to the study of Ottoman food production is a surface survey in the eastern Peloponnese in which practices of land exploitation and agricultural estates (çiftliks) were a focus of research (Gregory 2007). In addition, Ottoman grain mills and olive presses in eastern Crete and in Stari Bar (Montenegro) were recorded, as well as the use of water mills in the Near East (McQuitty 1995; Brumfield 2000; Zanichelli 2008). Ottoman food systems in general received attention (LaBianca 2000; Singer 2011), with research on animal-bone finds in Hungary and in Stari Bar (Pluskowski and Seetah 2006), and on plants and crop husbandry in Turkey (Nesbitt 1993). In addition, ceramic evidence for beekeeping was recognized in Palestine under the Mamluk Sultanate (ca. mid-13th to early 16th centuries) and in the following period under Ottoman rule (ca. early 16th to early 20th centuries) (Taxel 2006).

Although little exists in the way of specific archaeological research on Ottoman nutrition (studies in archaeobotany, archaeozoology, and osteology; food residue; and isotope analyses), a good deal of research has been carried out in written sources with respect to food prices, street “fast” food, public soup kitchens (imarets), religious rules regarding diet, and travelers’ accounts on the use of food (Faroqhi and Neumann 2003; Ergin et al. 2007; Singer 2011).Footnote 3 These accounts make it clear that most European travelers found Ottoman food too plain and simple for their liking, noticing in particular the lack of sauces, gravy, or garnishes (de Nicolay 1576:177–178; Moryson 1617:128; D’Ohsson 1791:23); compare Vroom (2003:336–337). This opinion was expressed in no uncertain terms by a Spaniard who served as a physician to Sinan Pasa (admiral of the Ottoman fleet) in the 16th century and complained that common Ottomans were not particularly concerned with food: “If you ask me, they eat to live, not because they take pleasure in food” (Solalinde 1919:254–257).

There is, on the other hand, a plethora of literature on the sumptuous dining habits of the sultan’s court and of the Ottoman elite, often based on archival documents and reports by Western travelers. The subjects of these studies range from political dining (ambassadors’ lunches and receptions), ceremonial feasting, and outdoor meals (picnics) to etiquette, table equipment, and aspects of courtly cooking, including the imperial kitchen, its staff, and its porcelain and metal utensils (Erdoğdu 2000; Kut 2000; Türkoğlu 2000; Bilgin 2009; Vroom 2011, 2017:910–911, figure 9.6.5). A distinction between an “Eastern model” and a “Western model” of dining habits could be revealed in certain parts of the Ottoman Empire, apparent by differences in furniture, cutlery, and pottery shapes (Table 1); compare Vroom (2003:349–352, table 12.5).

Apart from the archaeological study of the Ottoman food-related material culture, the study of pictorial evidence of Ottoman dining scenes is also a valuable way of adding perspective to the information provided by written sources, such as the accounts by Western travelers (Fig. 1). Quite informative, for example, are paintings depicting festivities of the Ottoman court and the capital’s elite, and the considerable number of colorful miniatures (such as those by the famous miniaturist Levnî) with dining scenes in books, such as Hünername and Surnâme-i Vehbi (Atasoy 1971; Irepoğlu 1999; Bağcι et al. 2010; Yeniṣehirlioğlu 2020).

Use of food products at the Ottoman court and upper classes, as shown in miniatures (left) and in recipes from a 19th-century cookbook (right) (Vroom 2003:343, tables 12.2–12.4, 346, figures 12.3–12.4).

Ottoman Foodways: Widening Rims, Changing Dining Habits

According to Western travelers who reported on Ottoman dining habits, most of the ordinary houses in the Ottoman Empire had no specific dining area, since all rooms were multipurpose and suitable for dining (Moryson 1617:126–127; D’Ohsson 1791:32; Dodwell 1819). In traditional households (especially among the well-to-do classes) during official meals the men ate separately from the women (who ate in the harem and women’s quarters) (Gürsoy 2006:108–113; Bilgin 2009:82–84). In houses of the Ottoman elite, servants would file in carrying food in lidded serving dishes made of metal (gold, silver, gold-plated copper) or “porcellana.” The only cutlery available on the dining table was spoons; otherwise, food was brought to the mouth with three fingers of the right hand (de Nicolay 1576:176; D’Ohsson 1791:32). The tendency of refining a meal with a pleasant scent led to the creation of rosewater dispensers and censers, thus adding another sensory stimulus to wining and dining (Forrest and Murphy 2013). Furthermore, the ceremony of the washing of hands before and after a meal involved a basin (leğen) and a spouted vessel (ibrik). In upper-class households the ibrik was often made of metal (tinned copper) and was brought round by a servant with a towel, while other classes used ceramic versions for hand washing (Vroom 2007b).

With the rise of a new, prosperous “middle class” in the Ottoman provinces during the 16th and 17th centuries, there was a growing demand for new delicacies and luxurious possessions related to the preparation and consumption of food (Gerö 1978; Bikić 2003; Establet and Pascual 2003; Kovács 2005). One of the many manifestations of this new affluence was an increase in the variety of ways in which food was prepared and in the amount of effort that was invested in dining in style, with luxury tablewares for specific functions and fashions (Carroll 1999, 2000; Vroom 2017:909–912). The use of fashionable tin-glazed tablewares from Ottoman pottery production centers (such as Iznik and Kütahya in western Turkey) played an important part in the dining rituals of the empire (Atasoy and Raby 1989; Carswell 1998; J. Rogers 2000; Vroom 2005:158–161,168–171). A new shape in the glazed-tableware repertoire of the 16th and 17th centuries was, for instance, a large flanged dish with an expanded flat rim, the diameter of which varied between 24 and 32 cm (Vroom 2000:204–206).

During this period the average rim width of Ottoman tablewares increased notably compared to the previous late Byzantine period (17–20 cm) (Vroom 2003:234–235, table 7.3). The new wide-rimmed glazed dishes were probably used for food that contained a lot of fat or liquid, such as soup, which in the 16th century became one of the most common dishes in the Ottoman Empire (containing, for instance, legumes and trachana). These liquid mixtures were probably eaten communally from a centrally placed large dish into which everybody who was sitting around it dipped his or her spoon (Fig. 1, left); compare Ursinus (1985) and Vroom (2003:346, figures 12.3–12.4).

The 19th century was, for the Ottoman Empire, a period of transition in which food consumption was transformed from an oriental table setting to a “modern” or Westernized dining style. By then the Eastern model and the Western model of dining habits could exist concurrently in some parts within the Ottoman Empire (Vroom 2003:349–351). In those regions where the Western style of dining was gaining ground, this meant an increase in the quantity, shapes, and variety of tableware (ranging from tureens to bowls for sherbet, compote, or halvah) and by the appearance of matching collections of personalized settings (among which were cutlery sets). This seems to be in accordance with the growing significance of individual dining in the Ottoman territories—and the related move to smaller/medium-sized individual plates for appetizers, desserts, or snacks—that took place as a result of the increasing influence of Westernized “bourgeois” consumption behavior (François 2001–2002, 2008; Samancι 2003:180–181, 2009; Vroom 2003:351–352).

Ottoman Food Products: 253 Recipes, 12 Ingredients, and 1 Tradition

Although Ottoman cookbooks have been used as historical sources, specific analyses of the ingredients listed in them have seldom been undertaken. Still, these ingredients can provide valuable information about the food, tastes, and diets of the well-to-do classes in Ottoman cities (Albala 2012). An important 19th-century Turkish cookbook, Melceü’t-tabbâhîn (literally “Refuge for Cooks,” based on earlier recipes), was translated into English as Turkish Cookery Book and offered an excellent “entry” for a Western audience into Ottoman cuisine (Kut 1996:67; Vroom 2003:342–344, figure 12.2). It contains 253 recipes divided into 20 sections, varying from meat stocks to jams and preserves. When one counts all ingredients in these recipes one arrives at a total of around 120, of which the 10 most-used are: (1) salt, 161 times; (2) butter, 128 times; (3) pepper, 113 times; (4) onions, 89 times; (5) sugar, 87 times; (6) eggs, 76 times; (7) mutton, 68 times; (8) flour, 51 times; (9) lemons, 48 times; and (10) cinnamon, 45 times (Fig. 1, top right); compare Vroom (2003:table 12.2).

The second place for butter (and sheep fat) suggests a high regard for this ingredient in the Ottoman kitchen, which seems quite normal in preindustrial nomadic societies of the East (Araz 2000; Şavkay 2000); see also the 15th- to 16th-century recipes in Yerasimos (2005) for the favorite ingredients of the Ottoman elite of that era: “rice, sugar and butter.” Olive oil, which was of course not readily available outside the Mediterranean area of the Ottoman Empire (but which had been much used in Greek/Roman/Byzantine cuisine), is quite uncommon in these recipes; it appears only in recipes for fish soups and a few fish dishes.Footnote 4

Mutton or lamb as the main ingredient of meat dishes also forms an important group in the recipes (in seventh place); fish, poultry, and game are not so popular. The meat dishes were prepared with a wide range of cooking techniques, including frying, roasting, and boiling, and are sometimes sweetened, revealing the Eastern preference for sugar, which is in fifth place in these recipes (Vroom 2003:344).

Pepper, salt, and cinnamon are the most popular spices (Fig. 1, right center); see also Neumann (2003), Vroom (2003:table 12.3), and Balta and Yιlmaz (2004). Other common spices, which are used in much smaller quantities, are garlic, mixed spices, cumin, nutmeg, and sago. Parsley and lemon juice are also regularly used as seasonings (Fig. 1, right bottom); see also Vroom (2003:table 12.4). Food products from the New World, such as potatoes, tomatoes, and maize were of course known in the 19th century, but not important in the cuisine featured in this Turkish Cookery Book.

The information from this cookbook is confirmed by other written sources, including account lists of food consumption in imarets that give detailed insight into the budget, the menu, and the rules of hospitality of these pious foundations that offered free meals to the poor (Faroqhi 1984:328, table 33; Singer 2009, 2011). Furthermore, an important task of the Ottoman state was to guarantee a continuous supply of the most essential foodstuffs to Istanbul (most notably bread) (Murphey 1988:230–234; İnalcik et al. 1997:180). In its hinterland, excavated archaeobotanical evidence from a small settlement in central Turkey seems to corroborate a grain-based diet for common Ottomans. A sample of charred plant remains from Ottoman times suggests that bread wheat was the main crop, followed (at a distance) by two-row hulled barley and rye (Nesbitt 1993; Fairbairn, 2002:206–207; Piskin and Tatbul 2015); see also Balta (1992) for the use of and trade in grain in Ottoman Greece.

Shipwrecks: The Archaeology of Sunken Networks

Many food provisions arrived in Istanbul by ship. A 17th-century register of market dues shows that imports of grain (barley and millet), olives, fruits, and cheese came from the Aegean, whereas other provisions (such as nuts and apples) came in middle-sized boats from the Black Sea region. Large galleons (kalyon) from Egypt provided the capital with more exotic food products, such as rice, spices, and sugar (Panzac 1992; Ḯnalcik et al. 1997:180–181, table I.36).

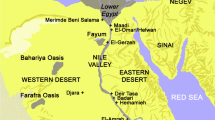

An archaeological perspective on Ottoman maritime movement of foodstuffs is provided by the “Sadana Island Shipwreck,” which was found 35 km south of Hurghada in the northwestern part of the Red Sea off the Egyptian coast. The wreck’s excavation resulted in detailed information about the ship, which was 50 m long, 18 m wide, and able to carry 900 tons of cargo. It probably sank in the 1760s, a period in which economic activity and maritime trade had increased in the Red Sea (Ward 2000). Ward (2000) mentions additional examples of Ottoman shipwrecks.

The cargo of this mid-18th-century ship included not only Chinese porcelain of the Qing dynasty (which was specially manufactured for the Middle Eastern market), but also glass bottles (transporting liquor), 50 copper artifacts related to food processing and serving (including a coffeepot), as well as ca. 800 unglazed clay water jars (qulal) of some 30 different types (Ward 2000:figures 7.4–7.5). Furthermore, most of the cargo consisted of organic material. Archaeobotanists detected spices from western India (such as pepper, coriander, cardamom, and nutmeg), frankincense from Oman, coffee beans, coconuts, food products from the Mediterranean (hazelnuts, grapes, figs, olives), as well as bones from sheep, goats, birds, and fish (Ward 2000:185,197–198). This varied cargo suggests that the ship sank on its way back to Ottoman territory coming from its far eastern borderlands (and perhaps beyond).

Other Ottoman shipwrecks seem to confirm this trade along the maritime Silk Road.Footnote 5 For instance, around 1,000 Ottoman ceramic pots were recovered in the northern Red Sea as cargo of a ship that sank in the Bay of Sharm-el-Sheikh near the southern tip of the Sinai (Raban 1971; Ward 2000:187). Most of these items seem to be unglazed water jugs (qulal) with sieves in their interior necks. Furthermore, tobacco-pipe bowls and implements for smoking opium were found in the shipwreck as well as fragments of Chinese porcelain cups of the late Kangxi period, dated to the first half of the 18th century (Raban 1971:151–152).

Recently, a British-led group of underwater archaeologists discovered 12 shipwrecks between the Lebanese and Cypriot coastlines, among which were the remains of a large 17th-century Ottoman merchant boat 43 m long and capable of carrying 1,000 tons of cargo (The History Blog 2020). The ship sank around 1630 during the reign of Sultan Murad IV (reigned 1623–1640), apparently on its way between Egypt and Istanbul. Its cargo included at least 588 artifacts of a wide variety of cultural origins, ranging from Yemeni water jars to painted jugs from Italy. Furthermore, it yielded peppercorns from India, incense from Arabia, and a copper coffeepot (Middle East Monitor 2020).

These items not only shed light on maritime trade routes, but also on daily life at sea in the Ottoman era. The wreck seems to be evidence of a maritime route running from China and India to the Persian Gulf and Red Sea, and into the eastern Mediterranean, most probably ending in Istanbul. The wreck’s cargo contained 360 cups, dishes, and a Chinese porcelain bottle that were made in the kilns of Jingdezhen during the reign of Chongzhen (1611–1644), the last Ming emperor; compare Raby (1986). Decorated with idyllic pastoral scenes, figures, and floral motifs, these blue-and-white cups were at first designed for sipping tea (Pitts 2017). Nevertheless, the Ottomans adapted them for the new consumptive fashion then spreading across the East: coffee drinking.

Coffee Drinking: The Typo-Chronology of a National Pastime

The shipwrecks yielded both local and imported ceramics, among which delicately made cups related to the spread of coffee consumption in the Ottoman Empire are prominent (Vroom 1996, 2003:354–356). These small glazed cups (known as finçan) have received much attention in Ottoman archaeology. This is due to the fact that coffee cups are easily identifiable in ceramic assemblages from excavations and surface surveys. Vroom (1996, 2020a:688) demonstrates that Ottoman coffee cups have even been recovered in archaeological contexts outside the Ottoman Empire, showing that the Ottomans were trendsetters in coffee drinking. Moreover, their production typologies offer a valuable chronological tool, as is shown by quite solidly dated, colorful decorated examples excavated from rubbish pits at Thebes in central Greece (Fig. 2); compare Vroom (2006:181–233, 2007a:81–83, figure 4.12–14). The presence of these high-quality 18th-century ceramics among the Theban waste appears to represent the discards of a well-to-do provincial household that was able to import decorative tableware from the heart of the Ottoman Empire.

Thebes, Greece: finds of Kütahya coffee cups in rubbish pits (Vroom 2006:figures 19–22,30–31).

In fact, the majority of such glazed coffee cups excavated in the Ottoman territories came not as imports from southeastern China or from European factories (like the ones made in Meissen, Vienna, and Sèvres ca. 1730–1740), but were in fact produced at Kütahya in northwestern Turkey (Lane 1939:236, 1957:65). This new type of thin-walled tableware, made of a fine buff-colored fabric, made its way from Kütahya to other parts within and beyond the Ottoman Empire during the 18th century; see, for example, finds in shipwrecks off the southern French coast (Amouric et al. 1999:159–168). Kütahya ware was strongly influenced by imported Chinese porcelain and is therefore sometimes described as a cheap substitute for real porcelain or as “peasant-porcelain” (Lane 1957:65).

Late 18th- to 19th-century decorated Kütahya ware was also found in the refuse in various Ottoman pithoi (large storage jars), pits, and wells in the Athenian agora in Greece (Frantz 1942; Vroom 2019:190–191, figure 3). These coffee cups were found in substantial numbers specifically in the central part of the agora (in and around the “Late Roman Palace” and near the demolished church of Vlassarou), confirming that coffee was regularly consumed on this spot from the 18th century onwards. In a late 18th-century engraving, some British travelers can be detected here, studying the nearby monument of Philopappos in Athens, while the Janissary who escorted them prepared coffee on a tripod in the open air (Stuart and Revett 1762–1830[3]:5.1).

In the course of the 18th century coffee drinking became a popular pastime all over the Ottoman Empire, resulting in the introduction of special equipment, such as coffee burners, grinders, sieves, and brewers. After meals, diners in well-to-do households washed their hands and drank coffee from delicately painted cups, sometimes with matching saucers, as hot and as black as possible, which was considered to aid the digestion (Dodwell 1819:157); compare François (2012:482–486, plate 5) and Yenişehiroǧlu (2017). However, archaeological finds clearly indicate that the new stimulant was not only drunk after meals at home or in the harem, but also in bathhouses (hammam), in gardens, and in open fields (probably during picnics) throughout the empire (Karababa and Ger 2011; Sabbionesi 2014).

The delicacy of the Kütahya-ware cups suggests that they were primarily made for intimate gatherings of the Ottoman affluent classes, but their success also made them suited for more mundane use in coffeehouses and bazaars (Hattox 1985; Işin 2003; Georgeon 2009). In his famous travel account, Evliya Çelebi recorded at least 300 coffeehouses and 500 coffee merchants in Istanbul alone (Evren 1996). Coffee cups found during excavations in the markets of Istanbul yielded a wide spectrum of coffee-cup types, each apparently associated with varying levels of social prestige (Kut 1996; Baram 1999, 2002, 2009; Yenişehiroǧlu 2017). Eventually, imperial edicts were even issued against coffeehouses, as these popular establishments for both Muslims and non-Muslims often became places beyond government control (and developed into locations that fostered conservation and the transfer of ideas) (Beeley 1970; Karababa and Ger 2011).

Cooking Techniques: Baking, Boiling, Roasting in a Separate Place

Apart from the imperial kitchens of the Topkapι Palace in Istanbul (about which there are many written sources and accounts––compare Faroqhi and Neumann (2003), Gürsoy (2006:95–111), and Bilgin (2009)––it is not easy to find archaeological evidence of kitchens, kitchen furniture (ovens, hearths), and equipment in other parts of the Ottoman Empire (an ethnographical approach is provided by Koṣay and Ülkücan [1961]. Taking into account that the imperial kitchens would skew perception of other more modest cooking spaces, it seems that during Ottoman times most kitchens were separate places, situated away from the living quarters (for instance, in a court- or backyard, including a kitchen garden), and this practice still continues in some parts of present-day Turkey (Koṣay and Ülkücan 1961:plates 1–7). Food and bread were also cooked in a public bakery (firin) or bought in a shop (Yerasimos 2005). All this was common to most of the Mediterranean and large parts of the Middle East, not just the Ottoman Empire.

The transfer of several cooking techniques (such as baking, boiling, roasting, and frying) from areas outside the empire can provide additional information on Ottoman kitchens. It is likely, for instance, that the spread of Turko-Islamic cuisines and of tannur ovens in Eurasia and Africa is related to 16th-century trade routes to the eastern parts of the Ottoman Empire (Laudan 2013:map 4.3). The tannur (or tandir, tabun) used here was an enclosed structure made of clay and heated from within. These built-up ovens were specifically used for the cooking and heating of dishes, as well as for the baking of flat bread (pide).

According to ethnoarchaeological research, four types of permanent built fire installations could be discerned in traditional villages in modern Syria (which very well may reflect the situation in villages all over the eastern parts of the Ottoman Empire): (1) a cylindrical, hollow clay installation, ca. 1 m high and ca. 45–50 cm wide with a small opening at the bottom for fuel (tannur, tandoor); (2) a smaller “igloo-shaped” clay installation, partly dug into the floor, ca. 45 cm high and ca. 60 cm wide at the bottom, with a small opening at the bottom for fuel (tabun); (3) a domed metal pan, placed on bricks with fuel in between (saj); and (4) a domed cylinder-shaped clay installation, ca. 80–100 cm high, with a shelf and a large opening on the front side (waqdiah) (Mulder-Heymans 2002:198). Depending on the oven shape, different varieties of bread were baked either on the inside or outside of the installation, while dishes could be cooked or meat roasted in the sintering fire. The fuel provision varied (wood, charcoal, animal dung, agricultural residues), but was always from local sources (Smith 1998).

Ceramic Utensils for Food Processing: Casseroles, Frying Pans, and Beyond

Domestic utensils made of earthenware (pots, vessels, frying pans), which may be related to these built fire installations, have been found in various excavated Ottoman contexts (such as those shown in Figures 3 and 4). Although regional variation in these coarse wares existed, there was also a clear standardization of some specific types of utilitarian wares that were used for food processing (including food preparation and cooking). A system for diagnosing the typo-chronology of unglazed coarse wares of Ottoman times from stratigraphic excavations at Istanbul was developed by John Hayes. His first preliminary report on these wares came from excavations of the Bodrum Djami (or Myrelaion), followed by a more extensive publication from the Saraçhane Djami excavations 11 years later (Hayes 1981, 1992:chapters 13–24). About 190 vessel types were listed in a preliminary conspectus of the types used in Istanbul during early Ottoman times (Hayes 1992:233).

Early Ottoman unglazed ceramics produced and used in Istanbul differed significantly from their (late) Byzantine predecessors. One of the most striking new features in the Saraçhane Djami assemblages was the total disappearance of commercial amphorae for bulk goods (wine, olive oil), which were probably replaced by wooden barrels (Vroom 1998). Furthermore, one may notice the replacement of thin-walled, unglazed cooking pots by simple lead-glazed types, with a glaze applied directly on the clay body (rather than applied on a slip in between). Consequently, the quantities of glazed wares in the Saraçhane contexts increased substantially, to around 35%–40% of finds in early Ottoman contexts, with a further rise in the 18th/19th centuries, when glazed wares came to predominate (ca. 60%–80%) (Hayes 1992:233).

In addition, the Saraçhane assemblages clearly show that new shapes of coarse wares appeared in early Ottoman times. In contrast to those of earlier periods, the late 15th- to 17th-century deposits contained high-stemmed bowls (goblets or cups, perhaps for drinking sherbet, ayran, or just water), spouted jugs (the so-called ibrik), tall two-handled flagons, basket-handled jars, and two-handled jars, sometimes with a glaze at the bottom (Hayes 1992:figures 103–133). The function of these last ones was described by Hayes as “stew pots,” by others as “chamber pots” (Bakirtzis 1980; Hayes 1992:286, figure 105; Bikić 2003:figure 35; François and Ersoy 2011:385–386, figure 7). They had an interior coated with a lime deposit, which could indeed reasonably point to sanitary uses (Vroom 2006:195, figures 58,61).

Similar typological changes in the ceramic repertoire can be seen in other parts of the Ottoman Empire. On Cyprus, for instance, the introduction of new shapes (together with decorative motifs) took place in unglazed domestic wares, especially in hand-formed manufactured vessels that existed side by side with wheel-made pots (Gabrieli 2009:71–72). At Paphos in western Cyprus, a 15th- to 16th-century kitchen assemblage varied from typical cooking pots and fireproof boiling jars to newly introduced casseroles (oven dishes), bowls, pans, and plates for food preparation (Gabrieli 2009:figures 6.5–6.7). Similar-looking local handmade cooking pots, casseroles, jugs, jars, and frying pans came from four sealed 16th- and 17th-century deposits under an excavated house at Nicosia (François 2017:figure 11,D37,C17).

In Middle Eastern assemblages there is evidence for continuity in the production and use of handmade coarse vessels at rural settlements from the 15th century into Ottoman times (Milwright 2000:193–195, 2008). Deep, hole-mouth, globular cooking pots (both handmade and wheel-made ones) seem to dominate Ottoman kitchen assemblages in Israel and Palestine—a shape that seemed to be spreading to other parts of the Eastern Mediterranean (Fig. 3) (Hahn 1997:plate 55 no. 6229, plate 57; Gabrieli 2009:figure 6.5 nos. 1,6, figure 6.7 nos. 1,3; London 2016:243). This is shown by excavated early Ottoman examples at Khirbal Birzeit, Ti‘innik, Emmaus Qubayba, Tel Jezreel, and Jerusalem (Abu Khalaf 2009; Avissar 2009).Footnote 6 Such cooking pots could, for instance, be directly placed in hot embers/charcoal, on a metal tripod, and on a cooking installation (such as the tannur), or were perhaps hung from above on a pothook.

In addition, excavations at various sites in the Middle East (among which are Khirbat Birzeit, Ti‘innik, Sataf, and Karak in Jordan) have shown an increase of finds of open, shallow utilitarian vessels, such as casseroles (known in Turkish as “güvec”), cooking bowls, pans, and basins (the latter are known in Greek as “lekani”). They varied in size and form (Fig. 4). Their shapes made them suitable for multifunctional food processing, among which the simmering of tough meat cuts (such as lamb shank) in saucy stews, the baking of (savory) bread in an oven, as well as the soaking of beans or chickpeas, the cleaning of lentils, and the kneading of bread or dough for pies and pastries; compare Kyriakopoulos (2015:256).

Then again, late Ottoman pottery assemblages start to show more variety in domestic utensils. Excavations of a late Ottoman house at Izmir (old Smyrna) yielded, for example, different types of cooking, serving, and tablewares dated to the second half of the 18th century (François and Ersoy 2011). The batterie de cuisine found at this cosmopolitan household consisted not only of locally made casseroles, cooking bowls, glazed conserve pots, and glazed basins, but also of imported casseroles and basins from workshops at Savona or Albisola in Liguria (northern Italy) and imported casseroles and a frying pan/saucepan (testo) from ateliers in Vallauris/Biot (southern France) (François and Ersoy 2011:figures 2–4).

During the 19th century, imported cooking utensils with glazed interiors began to appear at various sites in the Eastern Mediterranean: not only from southern France (Vallauris/Biot) and northern Italy (Savona/Albisola) as in the case of Smyrna, but also from the Greek island of Siphnos (Fig. 5). These imported vessels have been found in excavated contexts at Chania, Ephesus, Paphos, Tel Yoqne’am, and Jerusalem, where they were mostly dated from the second half of the 18th to the early 19th century (Hahn 1997:plate 57 no. 80-P 0354/0358; Avissar 2009:figure 2.2 no. 6, figure 2.11 no. 15; Gabrieli 2009:figure 6.7 nos. 6–7; François 2015:figure 1 no. 3; Vroom and Fιndιk 2015:plate 35 no. 139). It is not unlikely that they were brought by “stewpot sellers” to Ottoman households, as is shown for a later period on old photographs of Ottoman crafts and guilds in Istanbul (Fig. 5, top right) (Evren 1999:199).

Distribution map of 19th-century glazed cooking dishes (“stew pots”) in the Eastern Mediterranean (Map by author, 2021); and right: old photo of an Ottoman “stewpot seller” (Evren 1999:199).

The Siphniote glazed cooking dishes (known in Greek as “tsoukali” or “tsikali”) were widely exported (in particular from the 1840s onward) on boats from coastal workshops on the island to other parts of the Aegean, the Ionian islands, Cyprus, and the Middle East (Jones 1986:figure 12.5; Kyriakopoulos 2015:261–264). The good reputation of the cooking wares from Siphnos for boiling, frying, or baking was based on the special heat-resistant properties of their very micaceous and iron-rich fabrics. In addition, in the early 18th century the French botanist/traveler Joseph Pitton de Tournefort praised the quality of Siphniote lead, a lead as hard as pewter, which “makes the seething pots of the island exceeding good” (de Tournefort 1717:letter IV). Due to these reasons, the Siphniote vessels were said to have been preferred by Cretan housewives even above locally made cooking wares (Blitzer 1984:145).

An Ethnoarchaeological Case Study: A Periphery without Pottery

Ethnoarchaeological research and ethnographical collections can provide additional information on foodways and the use of related domestic ceramic utensils in rural settlements during Ottoman and more recent times in the sense that they try to reconstruct actual daily life in a traditional preindustrial society (Kohl 1989:241; London 2000, 2016). Ethnographical collections often show complete objects and nicely decorated pots, whereas oral history may provide information on daily life that cannot always be found in written sources. An example of ethnoarchaeological research is the study on long-term subsistence strategies and food behavior in remote Greek mountain villages by the Aetolian Studies Project (S. Bommeljé et al. 1987:114–135). By using both surface surveys and structured interviews in nearly 300 villages in Aetolia in central Greece, this multidisciplinary project aims to shed light on the history of habitation and the long-term “genre de vie” in this inhospitable mountain region from prehistoric times to the end of the premodern era (ca. 1950, when the end of the Greek Civil War came with the introduction of passable dirt roads, electricity, and even of utensils made of plastic or aluminum). The data of the surface survey and the village interviews were supplemented by information retrieved from Ottoman tax registers, early population counts, historical agricultural statistics, and reconstruction of the network of footpaths, bridges, and inns (Doorn 1989; Y. Bommeljé and Doorn 1996).

The interviews were conducted between 1981 and 1990 in 278 villages and several hamlets, as well as in old inns along transhumance routes that were still more or less in use, all situated in the modern eparchies of Evrytania, Trikhonis, Mesolongion, Navpaktia, and Doris. A structured questionnaire was used that contained questions on various aspects of economic and domestic life in the pre–Second World War period (Doorn et al. 1987:54–60).

In most mountain villages a surplus of animal produce and dairy products existed, while there were structural shortages of olives/olive oil, grains (such as wheat), and fruits. Vegetables, wine, and fruit were produced exclusively for the household (Doorn et al. 1987:59, table 5.6). In most lower-lying villages a (small) surplus of agricultural products existed, while there were structural shortages of animal and dairy products. So, an intraregional exchange of foodstuffs took place between villages. Common for all villages was a very basic level of technology and possessions. Many households in the mountain villages had hardly any ceramic cooking utensils. Copper kettles as well as wooden dishes and plates were the rule, and in extremely hard times onion peels were used as spoons (Vroom 1998:151–154). In fact, wood and copper do not survive in archaeological contexts, which results in “sherdless sites” (Vroom 1998).

The information from these village interviews by the Aetolian Studies Project forms a regional perspective in addition to local ethnographic research in the same region. The Greek ethnographer Dimitris Loukopoulos (1874–1943) discussed, for instance, the production and consumption of foods (and drinks) in specific villages in this mountainous landscape (Loukopoulou 1984:107–138). In total, Loukopoulos described 81 domestic utensils, of which most were made of metal (37%), followed by artifacts made of wood (29%) and of textile (10%), whereas only 6% of the implements were made of earthenware (Fig. 6). The functions of these utensils in Aetolian households ranged from food processing (37%), storage and transfer (24%), food and beverage service/consumption (both 15%) to various household activities (such as washing and lighting) (Fig. 7).

As for food products related to these domestic utensils, those most mentioned by villagers were liquids (33%) and cereals (21%), followed by dairy products (17%) and meats and fish (10%), while sweets and fruits (7%), flavors (7%), and vegetables and legumes (5%) appeared to be less frequent (Fig. 8). The findings of Loukoupoulos confirm the data of the Aetolian Studies Project: In these mountainous villages, everything was focused on a subsistence strategy of survival in a harsh environment; thus food was preserved and stored for as long as possible. Because the milk of goats and sheep could not be preserved, it was hardly consumed but immediately made into cheese and butter.

In total, Loukopoulos mentions ca. 55 ingredients of food dishes cooked in Aetolian households (Loukopoulou 1984:107–138). Meals were simple, if not basic, and the 10 most-used ingredients were olive oil, meat, flour, butter, eggs, cheese, salt, onions, rice, and pepper; except for the olive oil, this is comparable to the 19th-century recipe book mentioned earlier (Fig. 9). Furthermore, the five most-used domestic utensils for the processing of these foodstuffs in Aetolian households were metal ones (often copper): a baking tin or pan (tapsi), a portable lid/oven (gastra), a cauldron/cooking pot (chytra), a frying pan (tigania), and a double-handled frying pan or casserole (sagani) (Fig. 10). Of these, the portable copper gastra were easier to use and clean than permanent, large built ovens, and they were smaller, faster, and less expensive alternatives for the outdoor baking of bread or food, as they needed less firing wood; compare Kyriakopoulos (2015:256), who mentions that on the Greek islands ceramic charcoal braziers, known as “foufou,” were used.

The five most-used domestic utensils for food processing in Aetolia. (Graph by author, 2021; images from Loukopoulou (1984:figures 32,33,35–37).)

The preference for metal utensils in Aetolian households is confirmed by archaeological evidence. In general, virtually no postmedieval pottery was found during the survey in the Aetolian mountains (Vroom 1998:147–150). A recurrent theme in the village interviews and from the written sources is that transport of ceramics into the Aetolian mountains was difficult and very expensive in terms of loss of items that broke on the way (Vroom 2007a:89). People were, therefore, eating from wooden bowls with wooden spoons (Vroom 1998:figure 14c). Furthermore, metal objects were very much in favor (especially in transhumant households; compare M. Rogers [1986]). In the long run they were cheaper, since, when broken, they could be repaired and reused several times. In the kitchen and storerooms, baskets of all kinds held charcoal, vegetables, and indeed all kinds of food, for there were no sacks or wooden tubs or metal containers to store food. Water was stored in leather bags and buckets, but also in wooden flasks (Vroom 1998:figure 15). This genre de vie, which presumably existed for centuries, including the Ottoman era, is virtually invisible archaeologically.

However, a major change in this way of life appeared in Greece in the 19th century with the introduction of industrial manufactured wares, which were cheaper and mass-produced in the West. The archaeological record shows that consumption patterns in Greece started to change, evident in the large amounts of transfer-printed plates from Europe in Greek collections (Vroom 1998:146–147, figure 11, 2003:236–237; Liaros 2016; Palmer, this issue). Sparse finds of these Western wares in Aetolia suggest a slow spread of change in the mountains. For the rest of Greece it is clear that the introduction of the industrial manufactured wares was only part of fundamental socioeconomic changes (for instance, an increase in consumer purchasing power, an intensification of commercial agriculture, and new means of transport and distribution methods, such as steam ships). These changes included changes in dining habits. These are reflected in the substantial quantities of mass-produced, industrially manufactured, late Ottoman and early modern ceramics (mainly of the 19th and 20th centuries) that archaeological survey teams collect on the surface in Mediterranean regions (Vroom 1998:figures 4–10). In the Aetolian mountains, however, the archaeological record shows that substantial parts of the region witnessed only a very marginal influx of these wares, and in some deserted late Ottoman and early modern villages no ceramics at all are to be found among the ruins of the houses, as all household utensils continued to be made of metal or perishable materials for many decades after Greek independence (Vroom 1998:151–158).

Concluding Remarks

Every piece of broken pottery tells a story, and that holds true for pieces of Ottoman pottery: rim fragments speak of changing dining habits and diets, a piece of porcelain whispers about the extent of long-distance trade, a coffee cup declares the rise of new consumptive fashions with unforeseen consequences for society and politics, the tiniest fragment of coarse ware may inform about cooking techniques and food processing in all levels of society, and even the absence of broken pottery gives testimony on historical realities well beyond the scope of written sources. Although this storytelling is more often than not an incomprehensible mumbling, as the primary problem of dating and classifying finds is never easy and never definitive, it is clear that archaeology has the potential to add crucial layers of information and perspective on the social history of Ottoman foodways in the Eastern Mediterranean and in the Middle East.

In fact, archaeological data illuminate the material culture and related social behavior of all strata of past societies, including the Ottoman Empire. In this way archaeology certainly can reveal daily life practices of people in the Ottoman era whose voices are unheard in written texts and who are invisible in miniatures or paintings. And, beyond this, archaeology is also able to shed light on the movement of foodstuffs, on the introduction of new crops, of new tastes, of new dining habits, and of new trends in consumptive behavior, and how these spread through society. Archaeology has to offer a range of local, regional, and metaregional geographical perspectives that make it possible to link retrieved artifacts to networks of exchange, to long distance maritime trade, or to changing political situations. Thus it becomes possible to piece together an understanding of the movement of food products in the Ottoman world, including exotic products, such as Chinese porcelain tablewares and spices from the East. In this way even a humble chibouk clay bowl that is excavated in an urban rubbish pit or retrieved from a shipwreck (where it was probably used as a personal item by the captain or a crewmember during the ship’s journey) can offer a glimpse into how new consumption habits spread in the vast Ottoman Empire over various regions and different classes.

On the other hand, written sources may help in understanding archaeological finds. Ottoman cookbooks are a good example: they not only offer information on the use of certain ingredients at the sultan’s court and by the Ottoman elite, they also mirror the trickle-down effect of these food products to the middle classes in the provinces or even to country folk in villages, food products that could only be used by introducing appropriate kitchen utensils. In general, recipes in Ottoman cookbooks appear to be quite modest, reflecting a simple traditional diet for both the elite and ordinary people. Meat (mutton, chicken), bread, and rice were regularly consumed, at first in a communal Eastern dining style, followed from the 19th century onward in a more individual, Westernized manner.

From early Ottoman times onward, both the cookbooks and the archaeological repertoire reflect a growing demand for new delicacies and foreign products entering the Ottoman diet, such as sugar, maize, potatoes, tomatoes, and exotic fruits. Also, the written and material sources indicate that there was a development toward the refinement of dining habits with extra rituals (hand washing) and extra utensils (coffee cups, rosewater dispensers). The archaeological record all over the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East clearly indicates an increase in the quantity of glazed tableware as well as in the variety of decorations and shapes (among which are wide-rimmed glazed dishes and bowls), suggesting that such vessels became more affordable for ordinary folk in the Ottoman Empire.

In the Ottoman diet the central role of butter and animal fat seems to point to the nomadic roots of the Turks (coming from Central Asia) and less to the Mediterranean inclination toward olive oil, which was typical for the classical and Byzantine world. This is not to say that the Ottoman kitchen did not develop over time. Archaeological finds have revealed the spread of new cooking techniques and the introduction of new cooking installations (such as the tannur oven from the East) and related new pottery types for food processing both in Ottoman towns and rural settlements since the 16th century. These pottery types in excavated kitchenware assemblages not only had new shapes and sizes, but also gradually became more extensively lead-glazed on their interiors (which made their cleaning easier).

Eventually, ceramic cooking vessels started to be replaced by metal (copper) ones in Ottoman households in the Eastern Mediterranean. This development is, for instance, evident from the ethnoarchaeological and ethnographic research in the remote region of Aetolia in central Greece. In this poor Ottoman province the cheaper and more durable metal vessels were preferred as part of a subsistence strategy in which earthenware pottery proved less suited for local food preparation. Here, meals were simple, containing hardly anything more than the very basic ingredients of olive oil, meat, flour, butter, eggs, and cheese, which leaves the archaeologist of today quite empty-handed. Still, the very lack of Ottoman pottery finds in this periphery of the empire enables archaeology to contribute to the story of intraregional exchange of food products to balance the shortages and thus of long-term human survival in a harsh environment far away from the bright lights of the big city, Istanbul.

Notes

By “foodways” I do not mean just diet, but the totality of material and immaterial traditional food habits of a group, encompassing feeling, thinking, and behavior towards food and of food-related material culture, such as ceramic forms or vessels in other materials (wood, metal, leather, basketry). By “cuisine” I mean food practices (the art of cooking).

The term “Columbian Exchange” was introduced in 1972 to refer to the widespread exchange of animals, plants, culture, human populations, diseases, and ideas between the American and Afro-Eurasian hemispheres following the voyage to the “New World” by Christopher Columbus in 1492.

Unfortunately, there have not been developments in the study of Ottoman foodways, in the context of independence, of certain places by local academics. To my knowledge, there are also not many studies yet on archaeobotany, archaeozoology, osteology, food residue, and isotope analyses for the Ottoman period in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Apparently, until the 18th century olive oil was used by Ottoman Turks mostly for lighting and for pharmaceutical purposes; compare Yerasimos (2005:11).

I have not looked into the matter of harbor deposits; I have no knowledge whether they exist.

References

Abu Kahalf, Marwan 2009 The Ottoman Pottery of Palestine. In Reflections of Empire: Archaeological and Ethnographic Studies on the Pottery of the Ottoman Past, Bethany Walker, editor, pp. 15–22. ASOR, Boston, MA.

Albala, Ken 2012 Cookbooks as Historical Documents. In Oxford Handbook of Food History, Jeffrey Pilcher, editor, pp. 227–240. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

Amouric, Henri, Florence Richez, and Lucy Vallauri 1999 Vingt mille pots sous les mers: Le commerce de la céramique en Provence et Languedoc du Xe au XIXe siècle (Twenty-thousand pots under the sea: The ceramic trade in Provence and Languedoc from the 10th to the 19th century). Édisud, Aix-en-Provence, France.

Araz, Nezihe 2000 Ottoman Cuisine. In Imperial Taste: 700 Years of Culinary Culture, Nihal Kadioğlu Çevik, editor, pp. 7–20. Ministry of Culture, Ankara, Turkey.

Arsel, Sehamat (editor) 1996 Timeless Tastes. Turkish Culinary Culture. Vehbi Koç Vakfi, Istanbul, Turkey.

Atasoy, Nurhan, and Julian Raby 1989 Iznik. The Pottery of Ottoman Turkey. Laurence King, London, UK.

Atasoy, Nurhan 1971 The Documentary Value of the Ottoman Miniatures. In IVème Congress International d’Art Turc, pp. 2–17. Éditions de l'Université de Provence, Aix-en-Provence, France.

Avissar, Miriam 2009 Ottoman Pottery Assemblages from Excavations in Israel. In Reflections of Empire: Archaeological and Ethnographic Studies on the Pottery of the Ottoman Past, Bethany Walker, editor, pp. 7–14. ASOR, Boston, MA.

Avissar, Miriam 2005 Tel Yoqne’am: Excavations on the Acropolis. Israel Antiquities Authority, Jerusalem, Israel.

Bağcι, Serpil, Filiz Çağman, Günsel Renda, and Zeren Tanιndι 2010 Ottoman Painting. Ministry of Culture and Tourism, Istanbul, Turkey.

Bakirtzis, Charalambos 1980 Didymoteichon: Un centre de céramique post byzantine (Didymoteichon: A post-Byzantine ceramic center). Balkan Studies 21(1):147–153.

Balta, Evangelia 1992 The Bread in Greek Lands during the Ottoman Rule. Tarih Araştırmaları Dergisi 16(27):199–226.

Balta, Evangelia, and Fehmi Yιlmaz 2004 Salinas and Salt in Greek Lands during the Ottoman Period. In Tuz Kitabi, Emine Gürsoy Naskali and Mesut Şen, editors, pp. 248–257. Kitabevi, Istanbul, Turkey.

Baram, Uzi 1999 Clay Tobacco Pipes and Coffee Cup Sherds in the Archaeology of the Middle East: Artifacts of Social Tensions from the Ottoman Past. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 3(3):137–151.

Baram, Uzi 2002 The Development of Historical Archaeology in Israel: An Overview and Prospects. Historical Archaeology 36(4):12–29.

Baram, Uzi 2009 Above and Beyond Ancient Mounds: The Archaeology of the Modern Periods in the Middle East and Eastern Mediterranean. In International Handbook of Historical Archaeology, Teresita Majewski and David Gaimster, editors, pp. 647–662. Springer, New York, NY.

Beeley, Brian W. 1970 The Turkish Village Coffeehouse as a Social Institution. Geographical Review 60(4):475–493.

Bikić, Vesna 2003 Gradska Keramika Beograda (16–17.vek)/Belgrade Ceramics in the 16th–17th Century. Arheološki Institut, Belgrade, Serbia.

Bilgin, Arif 2009 De Ottomaanse Paleiskeuken tijdens de Klassieke Periode (15de–17de eeuw) (The Ottoman palace kitchen during the classic period [15th–17th century]). In Haremnavels, Leeuwenmelk en Aubergines. Culinair Erfgoed uit het Ottomaanse Rijk, pp. 70–93. Faro, Brussels, Belgium.

Blitzer, Harriet 1984 Traditional Pottery Production in Kentri, Crete: Workshops, Techniques and Trade. In East Cretan White-on-Dark Ware, Philip P. Betancourt, editor, pp. 143–157. University of Pennsylvania Museum, Philadelphia.

Boivin, Nicole, Dorian Q. Fuller, and Alison Crowther 2012 Old World Globalization and the Columbian Exchange: Comparison and Contrast. World Archaeology 44(3):452–469.

Bommeljé, Sebastiaan, Peter Doorn, Michiel Deylius, Joanita Vroom, Yvette Bommeljé, Roland Fagel, and Henk van Wijngaarden 1987 Aetolia and the Aetolians: Towards the Interdisciplinary Study of a Greek Region. Parnassus Press, Utrecht, the Netherlands.

Bommeljé, Yvette, and Peter K. Doorn 1996 The Long and Winding Road: Land Routes in Aetolia (Greece) since Byzantine Times. In Interfacing the Past. Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology CAA95, Hans Kamermans and K. Fennema, editors, pp. 343–351. University of Leiden, Leiden, the Netherlands.

Brillat-Savarin, Jean Anthelme 1826 Physiologie du goût ou, méditations de gastronomie transcendante (Physiology of taste or, meditations of transcendent gastronomy). A. Sautelet et Cie Librairies, Paris, France.

Broom, Douglas 2020 A History of the World in 5 Foods, 23 November. World Economic Forum <https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/11/fivefoods-that-shaped-human-history/>. Accessed 16 August 2023.

Brumfield, Allaire 2000 Agriculture and Rural Settlement in Ottoman Crete, 1669–1898: A Modern Site Survey. In A Historical Archaeology of the Ottoman Empire: Breaking New Ground, Uzi Baram and Lynda Carroll, editors, pp. 37–78. Kluwer/Plenum, New York, NY.

Carroll, Lynda 1999 Could’ve Been a Contender: The Making and Breaking of “China” in the Ottoman Empire. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 3(3):177–190.

Carroll, Lynda 2000 Towards an Archaeology of Non-Elite Consumption in Late Ottoman Anatolia. In A Historical Archaeology of the Ottoman Empire: Breaking New Ground, Uzi Baram and Lynda Carroll, editors, pp. 161–180. Kluwer/Plenum, New York, NY.

Carroll, Lynda, Adam Fenner, and Øystein S. LaBianca 2006 The Ottoman Qasr at Hisban: Architecture, Reform, and New Social Relations. Near Eastern Archaeology 69(3&4):138–145.

Carswell, A. John 1998 Iznik Pottery. British Museum Press, London, UK.

de Nicolay, Nicolas 1576 Vier Bücher von de Raisz und Schiffart in die Turckey (Four books of the journey and boat trip in Turkey). Willem Silvius, Antwerp, Belgium.

de Tournefort, Jean Pitton 1717 Relation d'un Voyage du Levant Fait par Ordre du Roy (Account of a voyage to the Levant made by order of the King). Imprimerie Royale, Paris, France.

Dodwell, Edward 1819 A Classical and Topographical Tour through Greece during the Years 1801, 1805 and 1806, Vol. 1. Rodwell and Martin, London, UK.

D’Ohsson, Ignatius Mouradgea 1791 Tableau général de l'Empire othoman, divisé en deux parties, dont l'une comprend la législation mahométane; l'autre, l'histoire de l'Empire othoman (General table of the Ottoman Empire, divided into two parts, one of which includes the Mohammedan legislation; the other, the history of the Ottoman Empire), Vol. 4. Imp. de monsieur [Firmin Didot], Paris, France.

Doorn, Peter K. 1989 Population and Settlements in Central Greece: Computer Analysis of Ottoman Registers of the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries. In History and Computing II, Peter Denley, Stefan Fogelvik, and Charles Harvey, editors, pp. 193–208. Manchester University Press, Manchester, UK.

Doorn, Peter K., Yvette Bommeljé, and Roland Fagel 1987 An Early Modern Subsistence Economy: Aetolia since 1821. In Aetolia and the Aetolians: Towards the Interdisciplinary Study of a Greek Region, pp. 59–61. Parnassus Press, Utrecht, the Netherlands.

Erdoğdu, Ayṣe 2000 Utensils Used in the Ottoman Kitchen. In Imperial Taste: 700 Years of Culinary Culture, Nihal Kadioğlu Çevik, editor, pp. 61–74, Ministry of Culture, Ankara, Turkey.

Ergin, Nina, Christoph K. Neumann, and Amy Singer (editors) 2007 Feeding People, Feeding Power. Imarets in the Ottoman Empire. Eren, Istanbul, Turkey.

Establet, Colette, and Jean-Paul Pascual 2003 Cups, Plates, and Kitchenware in late Seventeenth- and Early Eighteenth-Century Damascus. In The Illuminated Table, the Prosperous House, Suraiya Faroqhi and Christoph K. Neumann, editors, pp. 185–197. Egon Verlag, Würzburg, Germany.

Evren, Burçak 1996 Eski Istanbul’da Kahvehaneler (Coffeehouses in old Istanbul). Milliyet Yayιnlarι, Istanbul, Turkey.

Evren, Burçak 1999 The Ottoman Craftsmen and Their Guilds. Doğan Kitap, Istanbul, Turkey.

Fairbairn, Andy 2002 Archaeobotany at Kaman-Kalehöyük 2001. Anatolian Archaeological Studies/Kaman-Kalehöyük 11:201–209.

Faroqhi, Suraiya 1977 Rural Society in Anatolia and the Balkans during the Sixteenth Century, I. Turcica 9(1):161–195.

Faroqhi, Suraiya 1984 Towns and Townsmen of Ottoman Anatolia: Trade, Crafts and Food Production in an Urban Setting, 1520–1650. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Faroqhi, Suraiya 2009 Eten, Drinken en Gezelligheid (Eating, drinking and socializing). In Haremnavels, Leeuwenmelk en Aubergines. Culinair Erfgoed uit het Ottomaanse Rijk, pp. 46–67. Faro, Brussels, Belgium.

Faroqhi, Suraiya, and Christoph K. Neumann (editors) 2003 The Iluminated Table, the Prosperous House: Food and Shelter in Ottoman Material Culture. Egon Verlag, Würzburg, Germany.

Feuerbach, Ludwig 1866 Sämtliche Werke (Collected works). Verlag von Otto Wigand, Leipzig, Germany.

Forrest, Beth M., and Deidre Murphy 2013 Food and the Senses. In Routledge International Handbook of Food Studies, Ken Albala, editor, pp. 352–363. Routledge, Abingdon, UK.

François, Véronique 2001–2002 Production et consommation de vaisselle à Damas, à l'époque Ottomane (Production and consumption of tablewares in Damascus during the Ottoman period). Bulletin d’Études Orientales 53–54:157–174.

François, Véronique 2008 Jarres, terrailles, faïences et porcelaines dans l’empire Ottoman (XVIIIe–XIXe siècles) (Jars, earthenware, faïence and porcelain in the Ottoman Empire [18th–19th centuries]). Turcica 40:81–120.

François, Véronique 2012 Objets du quotidien à Damas à l’époque Ottomane. (Everyday objects in Damascus during the Ottoman period). Bulletin d’Études Orientales 61:475–506.

François, Véronique 2015 ‘Occidentalisation’ des vaisseliers des classes populaires dans l’empire Ottoman au XVIIIe siècle (‘Westernization’ of dressers of the popular classes in the Ottoman Empire in the eighteenth century). In Medieval and Post-Medieval Ceramics in the Eastern Mediterranean—Fact and Fiction, Joanita Vroom, editor, pp. 91–115. Brepols, Turnhout, Belgium.

François, Véronique 2017 Fragments d’histoire II: La vaisselle de table et du quotidien à Nicosie au lendemain de la conquête Ottomane (Fragments of history II: Tableware and daily use in Nicosia after the Ottoman conquest). Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique 141(1):354–387.

François, Véronique, and Akin Ersoy 2011 Fragments d’histoire: La vaisselle de table et du quotidien à Nicosie au lendemain de la conquête Ottomane (Fragments of history: Tableware and daily use in Nicosia after the Ottoman conquest). Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique 135(1):377–419.

Frantz, Allison 1942 Turkish Pottery from the Agora. Hesperia 11(1):1–28.

Gabrieli, Ruth Smadar 2009 Stability and Change in Ottoman Coarse Wares in Cyprus. In Reflections of Empire: Archaeological and Ethnographic Studies on the Pottery of the Ottoman Past, Bethany J. Walker, editor, pp. 67–77. ASOR, Boston, MA.

Georgeon, François 2009 De Koffiehuizen in Istanbul op het Einde van het Ottomaanse Rijk (The coffeehouses in Istanbul at the end of the Ottoman Empire). In Haremnavels, Leeuwenmelk en Aubergines. Culinair Erfgoed uit het Ottomaanse Rijk, pp. 140–173. Faro, Brussels, Belgium.

Gerö, Gyözö 1978 Turkische Keramik in Ungarn. Einheimische und Importierten Waren (Turkish ceramics in Hungary. Domestic and imported wares). In Fifth International Congress of Turkish Art, Geza Fehér, editor, pp. 363–384. Akademiai Kiado, Budapest, Hungary.

Given, Michael 2000 Agriculture, Settlement and Landscape in Ottoman Cyprus. Levant 32(1):209–230.

Gregory, Timothy E. 2007Contrasting Impressions of Land Use in Early Modern Greece: The Eastern Corinthia and Kythera. In Between Venice and Istanbul: Colonial Landscapes in Early Modern Greece, Siriol Davies and Jack L. Davis, editors, pp. 173–198. American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Princeton, NJ.

Gürsoy, Deniz 2006 Turkish Cuisine in Historical Perspective, Joyce H. Matthews, translator. Oğlak Güzel Kitaplar, Istanbul, Turkey.

Hahn, Margarethe 1997 Modern Greek, Turkish and Venetian Periods. In The Greek-Swedish Excavations at the Agia Aikaterini Square Kastelli, Khania 1970–1987, Vol. I,1: From the Geometric to the Modern Greek Period, Erik Hallager and Birgitta P. Hallager, editors, pp. 79–192. Paul Åströms Förlag, Stockholm, Sweden.

Hattox, Ralph S. 1985 Coffee and Coffeehouses. The Origins of a Social Beverage in the Medieval Near East. University of Washington Press, Seattle.

Hayes, John W. 1981 The Excavated Pottery from the Bodrum Camii. In The Myrelaion (Bodrum Camii) in Istanbul, Cecil L. Striker, editor, pp. 36–41. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

Hayes, John W. 1992 Excavations at Saraçhane in Istanbul, Vol. 2: The Pottery. Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, DC.

Ḯnalcik, Halil, Donald Quataert, and Suraiya Faroqhi (editors) 1997 An Economic and Social History of the Ottoman Empire, Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Ionas, Ioannis 2000 Traditional Pottery and Potters in Cyprus. The Disappearance of an Ancient Craft in the 19th and 20th Centuries. Ashgate, Aldershot, UK.

Irepoğlu, Gül 1999 Levni: Painting, Poetry, Colour. Ministry of Culture, Istanbul, Turkey.

Işin, Ekrem 2003 Coffeehouses as Places of Conservation. In The Illuminated Table, the Prosperous House: Food and Shelter in Ottoman Material Culture, Suraiya Faroqhi and Christoph K. Neumann, editors, pp. 199–208. Ergon Verlag, Würzburg, Germany.

Jones, Richard E. (editor) 1986 Greek and Cypriot Pottery: A Survey of Scientific Studies. British School at Athens, Athens, Greece.

Kadioğlu Çevik, Nihal (editor) 2000 Imperial Taste. 700 Years of Culinary Culture. Ministry of Culture, Ankara, Turkey.

Karababa, Eminegül, and Güliz Ger 2011 Early Modern Ottoman Coffeehouse Culture and the Formation of the Consumer Subject. Journal of Consumer Research 37(5):737–760.

Kiel, Machiel 1997 The Rise and Decline of Turkish Boeotia, 15th–19th century (Remarks on the Settlement Pattern, Demography and Agricultural Production according to Unpublished Ottoman Turkish Census and Taxation Records). In Recent Developments in the History and Archaeology of Central Greece, John Bintliff, editor, pp. 315–359. British Archaeological Reports, International Series 666. Archaeopress, Oxford, UK.

Kohl, Philip L. 1989 The Material Culture of the Modern Era in the Ancient Orient: Suggestions for Future Work. In Domination and Resistance, Daniel Miller, Michael Rowlands, and Chris Tilley, editors, pp. 240–245. Unwin Hyman, London, UK.

Koṣay, Z. Hamit, and Akile Ülkücan 1961 Anadolu Yemekleri ve Türk Mutfağı (Anatolian dishes and Turkish cuisine). Milli Eğitim Yayınları, Ankara, Turkey.

Kovács, Gyöngyi 2005 Iznik Pottery in Hungarian Archaeological Research. In Turkish Flowers. Studies on Ottoman Art in Hungary, Ibolya Gerelyes, editor, pp. 69–86. Hungarian National Museum, Budapest, Hungary.

Kut, Günay 1996 Turkish Culinary Culture. In Timeless Tastes. Turkish Culinary Culture, Sehamat Arsel, editor, pp. 38–61. Vehbi Koç Vakfi, Istanbul, Turkey.

Kut, Günay 2000 Past, Present and Future of the Kitchen on Our Daily Lives. In Imperial Taste: 700 Years of Culinary Culture, Nihal Kadioğlu Çevik, editor, pp. 39–50. Ministry of Culture, Ankara, Turkey.

Kyriakopoulos, Yiorgos 2015 Aegean Cooking-Pots in the Modern Era (1700–1950). In Ceramics, Cuisine and Culture. The Archaeology and Science of Kitchen Pottery in the Ancient Mediterranean, Michela Spataro and Alexandra Villing, editors, pp. 252–268. Oxbow, Oxford, UK.

LaBianca, Øystein S. 2000 Daily Life in the Shadow of the Empire: A Food Systems Approach to the Archaeology of the Ottoman Period. In A Historical Archaeology of the Ottoman Empire: Breaking New Ground, Uzi Baram and Lynda Carroll, editors, pp. 203–217. Kluwer/Plenum, New York, NY.

Lane, Arthur 1939 Turkish Peasant Pottery from Chanak and Kutahie. Connoisseur 104:232–259.

Lane, Arthur 1957 Later Islamic Pottery: Persia, Syria, Egypt, Turkey. Faber and Faber, London, UK.

Laudan, Rachel 2013 Cuisine and Empire: Cooking in World History. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Liaros, Nikos 2016 The Materiality of Nation and Fender: English Commemorative Dinnerware for the Greek Market in the Second Half of the 19th Century. In In and Around. Ceramiche e comunità. Secondo convegno tematico dell’AIECM3, Margherita Ferri, Cecilia Moine, and Lara Sabbionesi, editors, pp. 102–111. All’Insegna del Giglio, Florence, Italy.

London, Gloria 2000 Ethnoarchaeology and Interpretations of the Past. Near Eastern Archaeology 63(1):2–8.

London, Gloria 2016 Ancient Cookware from the Levant. An Ethnoarchaeological Perspective. Equinox, Sheffield, UK.

Loukopoulou, Dimitrios 1984 Αιτωλικαί οικήσεις, σκεύη και τροφαί (Aetolian settlements, utensils and food). Dodoni, Athens, Greece.

McQuitty, Alison 1995 Watermills in Jordan: Technology, Typology, Dating and Development. Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan 5:745–751.

Middle East Monitor 2020 Ottoman Shipwreck Found in the Eastern Mediterranean, 23 April. MEMO: Middle East Monitor <https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20200423-ottoman-shipwreck-found-in-the-easternMediterranean>. Accessed 14 September 2023.

Milwright, Marcus 2000 Pottery of Bilad al-Sham in the Ottoman Period: A Review of the Published Archaeological Evidence. Levant 32(1):189–208.

Milwright, Marcus 2008 Imported Pottery in Ottoman Bilad al-Sham. Turcica 40:213–237.

Moryson, Fynes 1617 An Itinerary Written by Fynes Moryson Gent, First in the Latin Tongue, and Then Translated by Him into English. John Beale, London, UK.

Mulder-Heymans, Noor 2002 Archaeology, Experimental Archaeology and Ethnoarchaeology on Bread Ovens in Syria. Civilisations 49(1&2):197–221.

Murphey, Rhoads 1988 Provisioning Istanbul: The State and Subsistence in the Early Modern Middle East. Food and Foodways 2(1):217–264.

Nesbitt, Mark 1993 Ancient Crop Husbandry at Kaman-Kalehöyük: 1991 Archaeobotanical Report. In Essays on Anatolian Archaeology, Takahito Mikasa, editor, pp. 75–97. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden, Germany.

Neumann, Christoph K. 2003 Spices in the Ottoman Palace: Courtly Cookery in the Eighteenth Century. In The Iluminated Table, the Prosperous House: Food and Shelter in Ottoman Material Culture, Suraiya Faroqhi and Christoph K. Neumann, editors, pp. 127–160. Egon Verlag, Würzburg, Germany.

Panzac, Daniel 1992 International and Domestic Maritime Trade in the Ottoman Empire during the 18th Century. International Journal of Middle East Studies 24(2):189–206.

Piskin, Evangelia, and Mustafa Tatbul 2015 Archaeobotany at Komana: Byzantine Plant Use at a Rural Cornucopia. In Komana’da Ortaçağ Yerleşimi, Burcu Erciyas and Mustafa N. Tatbul, editors, pp. 139–166. Ege Yayınları, Istanbul, Turkey.

Pitts, Martin 2017 Globalization and China: Materiality and Civilité in Post-Medieval Europe. In The Routledge Handbook of Archaeology and Globalization, Tamara Hodos, editor, pp. 566–579. Routledge, London, UK.

Pluskowski, Aleks, and Krish Seetah 2006 The Animal Bones from the 2004 Excavations at Stari Bar, Montenegro, Sheila Hamilton-Dyer, contributor. In The Archaeology of an Abandoned Town. The 2005 Project in Stari Bar, Sauro Gelichi, editor, pp. 97–111. All’Insegna del Giglio, Florence, Italy.

Raban, Avner 1971 The Shipwreck off Sharm-el-Sheikh. Archaeology 24(2):146–155.

Raby, Julian 1986 The Porcelain Trade Routes. In Chinese Ceramics in the Topkapi Saray Museum Istanbul, Vol. 1, Regina Krahl, Nurdan Erbahar, and John G. Ayers, editors, pp. 55–63. Philip Wilson/Sotheby’s, London, UK.

Reindl-Kiel, Hedda 1993 Die Lippen der Geliebten: Betrachtungen zur Geschichte der Türkische Küche (Lover's lips: Reflections on the history of Turkish cuisine). Mitteilungen der Deutsch-Türkische Gesellschaft 116:13–23.

Reindl-Kiel, Hedda 1995 Wesirfinger und Frauenschenkel: Zur Sozialgeschichte der türkische Küche (Vizier finger and woman's leg: On the social history of Turkish cuisine). Archiv für Kulturgeschichte 77(1):57–84.

Reindl-Kiel, Hedda 2003 The Chickens of Paradise: Official Meals in the Mid-Seventeenth Century Ottoman Palace. In The Iluminated Table, the Prosperous House: Food and Shelter in Ottoman Material Culture, Suraiya Faroqhi and Christoph K. Neumann, editors, pp. 59–88. Egon Verlag, Würzburg, Germany.

Rogers, Jeffrey M. 2000 Archaeology vs. Archives: Some Recent Approaches to the Ottoman Pottery of Iznik. In The Balance of Truth. Essays in Honour of Professor Geoffrey Lewis, Çigdem Balim Harding and Colin Imber, editors, pp. 275–292. Isis Press, Istanbul, Turkey.

Rogers, Michael 1986 Plate and Its Substitutes in Ottoman Inventories. In Pots and Pans: A Colloquium on Precious Metals and Ceramics in the Muslim, Chinese and Graeco-Roman Worlds, Michael Vickers, editor, pp. 117–136. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

Sabbionesi, Lara 2014 “Caffè Nero Bollente”: Tazzine in Contesto (“Boiling black coffee”: Cups in context). In Bere e Fumare ai Confine dell’Impero. Caffè e Tobacco a Stari Bar nel Periodo Ottoman, Sauro Gelichi and Lara Sabbionesi, editors, pp. 88–97. All’Insegna del Giglio, Florence, Italy.

Samancι, Özge 2003 Culinary Consumption Patterns of the Ottoman Elite during the First Half of the Nineteenth Century. In The Iluminated Table, the Prosperous House: Food and Shelter in Ottoman Material Culture, Suraiya Faroqhi and Christoph K. Neumann, editors, pp. 161–184. Egon Verlag, Würzburg, Germany.

Samancι, Özge 2009 De Culinaire Cultuur van het Ottomaanse Paleis and Istanbul Tijdens de Laatste Periode van het Rijk (19de eeuw) (The culinary culture of the Ottoman palace and Istanbul during the last period of the empire [19th century]). In Haremnavels, Leeuwenmelk en Aubergines. Culinair Erfgoed uit het Ottomaanse Rijk, pp. 118–137. Faro, Brussels, Belgium.

Şavkay, Tuğrul 2000 On Drinking and Eating in the Daily Life. In Imperial Taste: 700 Years of Culinary Culture, Nihal Kadioğlu Çevik, editor, pp. 21–38, Ministry of Culture, Ankara, Turkey.

Singer, Amy 2009 Liefdadigheid op het Menu: De Ottomaanse Publieke Keuken (Charity on the menu: The Ottoman public kitchen). In Haremnavels, Leeuwenmelk en Aubergines. Culinair Erfgoed uit het Ottomaanse Rijk, pp. 196–115. Faro, Brussels, Belgium.

Singer, Amy (editor) 2011 Starting with Food. Culinary Approaches to Ottoman History. Markus Wiener, Princeton, NJ.

Smith, Wendy 1998 Fuel for Thought: Archaeobotanical Evidence for the Use of Alternatives to Wood Fuel in Late Antique North Africa. Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 11(2):191–205.

Solalinde, Antonio G. (editor) 1919 Viaje de Turquia. Atribuido a Christóbal de Villalón (Voyage to Turkey. Attributed to Christóbal de Villalón). Calpe, Madrid, Spain.

Stedman, Nancy 1996 Land Use and Settlement in Post-Medieval Central Greece: An Interim Discussion. In The Archaeology of Medieval Greece, Peter Lock and Guy D. R. Sanders, editors, pp. 179–192. Oxbow, Oxford, UK.

Stuart, James, and Nicholas Revett 1762–1830 The Antiquities of Athens: Measured and Delineated by James Stuart F.R.S. and F.S.A. and Nicholas Revett Painters and Architects, 5 vol. John Haberkorn, London, UK.