Abstract

Post-1500 archaeology has undergone many changes in western Mediterranean Europe over the last three decades. This article explores how these changes have developed by focusing on the publishing of post-1500 archaeology in Italy, Spain, and France. Taking Italy as the primary example, it demonstrates that the path taken is intertwined with that of Northern Europe, but that it also deviates in its beginnings, its place in law, and its current place in academic and professional archaeology.

Resumen

La arqueología posterior a 1500 ha sufrido muchos cambios en la Europa mediterránea occidental durante las últimas tres décadas. En este artículo se explora cómo se han desarrollado estos cambios, centrándose en la publicación de la arqueología posterior a 1500 en Italia, España y Francia. Al tomar a Italia como el ejemplo principal, se demuestra que el camino emprendido se entrelaza con el del norte de Europa, pero que también se desvía en sus inicios, su lugar en la ley y su lugar actual en la arqueología académica y profesional.

Résumé

L'archéologie postérieure à 1500 a fait l'objet d'évolutions nombreuses dans l'Europe méditerranéenne occidentale au cours des trois dernières décennies. Cet article est une étude du mode de développement de ces évolutions, axée sur la publication de l'archéologie postérieure à 1500 en Italie, en Espagne et en France. Prenant l'Italie à titre d'exemple principal, il démontre que la voie adoptée est étroitement liée à celle de l'Europe du Nord, mais qu'elle s'écarte également quant à ses prémisses, sa place en matière légale et son positionnement actuel dans l'archéologie universitaire et professionnelle.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In an international setting characterized by varied terms used to indicate post-1500 archaeology, the term postmedieval archaeology is undoubtedly one of the most frequently used in Europe. The same term, however, has taken on different meanings in different research contexts, more or less adhering to the older British chronological definition in which postmedieval archaeology extends to the beginning of industrialization (although the Society for Post-Medieval Archaeology now includes the contemporary period under the same heading). It extends from the great transformations of urban landscapes, material culture, and many other archaeological indicators that happened from 1500 (as per convention) to the present. This long-term view allows the avoidance of unnecessary chronological and academic-disciplinary borders. Yet it has at times, as will be shown, impeded the development of post-1500 archaeology as a discipline. Furthermore, the development of its own publication outlets varies greatly across the Mediterranean region, with some countries boasting dedicated journals that have been running for decades, and others in which post-1500 archaeology is rare or nonexistent.

At the official founding congress of Italian postmedieval archaeology (in Sassari, Italy, in 1994) a broad comparison at the European level was conducted. After almost 30 years it is pertinent to reflect on the current state of postmedieval archaeology and on the growth of this research field in western Mediterranean Europe.

Unifying factors, starting from the 1970s, emerged in the methodological revolution that took place in the archaeology of areas of the Western Mediterranean, particularly with the widespread use of stratigraphic excavation (instead of the unscientific excavation, disinterested in stratigraphy, used previously), urban archaeology, and “preventive archaeology” (i.e., the documentation of archaeological heritage at risk of destruction during public or private construction works that involve underground interventions). France was faster than Italy and Spain in affirming preventive archaeology and its legislative framework. The role that the English theoretical reflection on stratigraphic excavation has brought to European archaeology in the last decades of the 20th century is well known and evident. It may be sufficient to recall the diffusion of the documentation system of stratigraphic units, the Harris matrix, and a diachronic vision of the stratigraphic sequence where (in particular in urban archaeology) post-1500 archaeology also acquired its own position in law supported by a methodological vision of continuity and by the explicit historiographic purposes of archaeological excavation.

It is a European process (albeit with differences) that has contributed—among other things—to building the common foundation of European postmedieval archaeology, with shared ideas, practices, and orientations. Significant results, such as a growing awareness of archaeology as a profession with its own scientific procedures, have been defined at the theoretical level.

The relationship that the archaeology of the most recent centuries (19th–20th centuries) establishes with current societies is also significant, with a more direct impact than archaeologies focusing on more distant periods. This allows the identification of the strong social utility of this archaeology, with an involvement of local communities typical of “Public Archaeology,” often caused by the greater temporal proximity and research on sensitive themes, as clearly appears in the archaeology of World War I, the Spanish Civil War, and the more recent Balkan conflict. In Italian postmedieval archaeology (archeologia postmedievale), the theoretical definition devised in the 1990s remains important, as it indicates a chronological arc of maximum continuity (Milanese 2021).

The aim of this essay is to present an assessment of post-1500 archaeology in western Mediterranean Europe, namely Italy, Spain, and France. Considering publication outlets as primary indicators of a research field, this article also discusses developments in each of these countries in terms of postmedieval archaeology’s institutional and university standing––see also Palmer and Given (this issue) for a Mediterranean-wide overview of post-1500 archaeology publications.

The German-speaking European tradition must also be mentioned, which prefers the term “historische Archäologie” instead of “postmedieval archaeology,” with a post-1500 chronology up to today that is defined in the editorial of the online magazine Historische ArchäologieFootnote 1 (beginning 2009). This editorial represents an interesting document that traces an international overview of the problem, but which ignores the Italian journal Archeologia Postmedievale (beginning 1997) and its diachronic line from 1500 to today.

The primary focus of this article will be mainly based on the author’s native Italy, reflecting direct experience in the discipline’s development, before expanding the discussion to include Spain and France.

First Steps

Post-1500 archaeology appeared explicitly as “postmedieval archaeology” in the Western Mediterranean area at the beginning of the 1970s. In Italy, however, there are examples of the application of archaeological methodologies to post-1500 heritage in the previous decade. It is an apparent paradox that postmedieval archaeology did not appear explicitly until the 1970s in western Mediterranean archaeology, even though the region was the birthplace of archaeology in the 17th century. This can be attributed to the strong connection and identification of Italian and Mediterranean archaeology with the history of ancient art and the dominance of classical archaeology, which prevented the development of postclassical archaeology until the 1970s.

The first investigations occurred in the coastal region of Liguria, where the application of the stratigraphic method to urban rescue archaeology highlighted at an early stage the informative potential of postmedieval archaeology (Mannoni 1969). Starting from 1971, the activities of Hugo Blake (2011) and a large English research group in the urban excavations of Genoa facilitated the comparison of the stratigraphic excavation methods used in Liguria with important concepts coming from the Anglophone sphere, where postmedieval archaeology (usually defined then as incorporating the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries) had already begun to become established. In May 1971, the Fourth International Ceramics Conference (in Albisola, Liguria, Italy) saw the participation of Tiziano Mannoni, Hugo Blake, and David Whitehouse. The largest session of the congress was devoted to postmedieval ceramics.

In the important synthesis of 1973 devoted to medieval archaeology in Italy (Mannoni and Blake 1973), the terms “postmedieval archaeology” and “postclassical archaeology” were both used several times, not as synonyms, but with different meanings. From that moment on, the term “postclassical archaeology” became popular, indicating a long-term perspective that extended from the fall of the Roman Empire to the beginning of the industrial age, the terminal chronological limit (ca. 1750) agreeing with that already identified for British postmedieval archaeology. While the term “postmedieval archaeology” continued to be used, Italian postclassical archaeologists were at that time mainly engaged in developing a new research agenda focusing on medieval archaeology and establishing stratigraphic excavation methodologies as the norm. The excavations in Genoa, therefore, continued to play an important role in laying the first foundations for Italian postmedieval archaeology (Milanese 1976; Andrews and Pringle 1977; Gardini and Milanese 1979).

At the beginning of the 1980s, postmedieval archaeology gained ground as the agenda of urban archaeology reached Rome. The investigations involved the extensive and systematic use of stratigraphic excavation (Manacorda 1982), which necessitated uncovering large and important post-1500 deposits. Carried out not only in the nation’s capital city, but also in one of the most significant centers in the ancient Mediterranean world, the excavations brought, for the first time, national attention to postmedieval archaeology. Unifying factors at the European level as the most significant drivers for the first experiences in Mediterranean postmedieval archaeology were the spread of stratigraphic excavation, urban archaeology, heritage protection, professional archaeology, and ceramic studies from an archaeological point of view; see also Palmer and Given (this issue). At different times and in different ways, the linguistic cast and footprint of postmedieval archaeology penetrated Mediterranean archaeology, indicating the adhesion by some groups of archaeologists to a research area identified immediately as postmedieval archaeology (Czech Republic), differently defined as archeologia postmedievale (Italy), arqueología postmedieval (Spain), or archéologie post-médiévale (France, Switzerland). And while British postmedieval archaeology has certainly influenced post-1500 archaeology in the western European Mediterranean, Italian archaeology has, like that of France and Spain, developed its own path in the field of the archaeology of more recent centuries since the 1970s.

The Italian Route to Postmedieval Archaeology

After the pioneering phase of the 1970s, the impetus gained from new methodological perspectives spawned a more chronologically and thematically inclusive type of protection of the archaeological heritage in urban areas. While this was a positive move, there was a danger that Italian postmedieval archaeology would remain limited within the confines of heritage protection and thus stagnate, rather than develop its own research agenda.

Despite the spread of stratigraphic excavation methods and a resulting increase in the quality of data being generated, the mere production of data from rescue excavations seemed to be a weak point for postmedieval archaeology. This was due in part to the fragmentary and occasional nature of data acquisition, but more notably to the lack of a research agenda and an absence of deeper theoretical reflection (Milanese 1983, 1997b:80–81). Throughout the 1980s, urban archaeology strengthened its position, both in Italy and in many European countries (Francovich and Milanese 1987). This process is also documented by the publication of large rescue excavations in Rome and Genoa dedicated entirely to post-1500 archaeology (Manacorda 1984; Milanese 1985). This phase of intense scientific activity in the field and of optimism among practitioners encouraged critical reflection that was to form the epistemological foundation of Italian postmedieval archaeology.

The space of Italian postmedieval archaeology was increasingly configured within the new professional archaeology, archaeological conservation, and the protection of archaeological heritage. At the same time, postmedieval archaeology became distinct and dislocated from Italian medieval archaeology, which itself was chronologically moving back the nodal points of its agenda toward the phenomenon of castles appearing in European medieval landscapes (Francovich and Milanese 1990) and the dynamics of transformation from the ancient world to the early Middle Ages (Brogiolo and Gelichi 1988).

Italian postmedieval archaeology was surrounded by skepticism or indifference, viewed on the one side by classical archaeologists and prehistorians as one of the most methodologically backward areas of Italian archaeology, and on the other all but ignored by medieval archaeologists, who were exploring topics that were completely distant in terms of chronology and objectives.

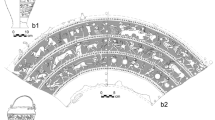

At the beginning of the 1990s, epistemological reflection identified the need to build a large European scientific community interested in the topic of postmedieval archaeology. In 1994 the international conference held in Sardinia, “Archeologia Postmedievale: l’esperienza europea e l’Italia” (Sassari, Italy, 17–20 October 1994) (Fig. 1), gathered together archaeologists representing five European nations, in addition to Italy (Milanese 1994–1997; Milanese 1997b:79): Belgium (Frans Verhaege), France (Philippe Bruneau, Pierre-Yves Balut), Great Britain (David Crossley), Spain (Fernando Amores), and the Netherlands (Jan Baart) (Milanese 1994–1997:9; Courtney 2009:175–176). The aim was to allow Italian postmedieval archaeology to compare itself with other European experiences, while also considering local factors and to think in a structured and expansive way about its own disciplinary definition. Methodological reports were given on the relationship between postmedieval archaeology and different areas of investigation, the relationship with global archaeology (Tiziano Mannoni), with protection (Piero Guzzo), with rural archaeology (Diego Moreno), and of abandoned sites (Juan Antonio Quiròs Castillo), with the history of material culture (Enrico Giannichedda), and the archaeology of architecture (Isabella Ferrando Cabona). Summaries of postmedieval archaeology in 13 (of 20) Italian regions were presented by archaeologists responsible for investigations of postmedieval archaeology, which encompassed varied and differentiated lines of research (Milanese 1994–1997:9–10). During that congress, a roadmap for Italian postmedieval archaeology was drawn, with its own specific declination and interpretation, starting from a chronology that also included the 19th and 20th centuries, taking its remit up to the then–present day (Milanese 1997a:16–17). This direction not only eliminated the obstacle of a chronology (the last couple of centuries) that many considered too recent for archaeological study, which is really a false problem (Milanese 2014:41–42), but also highlighted the centrality of information potential in judging the value of the archaeological record.

Italian postmedieval archaeology rejects the futile search for a recent chronological boundary and now goes as far as the 21st century, as can be seen from the excavation of 19th- to 21st-century rural settlements (Milanese and Biagini 1998), investigations rooted in historical ecology (Maggi et al. 2002). Moreover, archaeological approaches to the recent past or present are constantly evolving that foreground the archaeological gaze as a point of view (Milanese 2018; Stagno 2018) while operating in close connection with sociology, anthropology, oral history, and ethnography. The strongly interdisciplinary structure of Italian postmedieval archaeology allows it to extend its field of research to the contemporary age, right up to the present time, and therefore with a chronological limit in continuous evolution (unlike in the Aegean; see Lekakis [this issue]). This occurs in an interdisciplinary scenario of increasing articulation, particularly when it comes to investigating current or sub-actual phenomena of high sociological and anthropological complexity with tones and nuances of a past-present.

The archaeology of the recent past has always been on the research agenda of Italian postmedieval archaeology, as can be seen clearly in the special issue of the journal Archeologia Postmedievale dedicated to ethnoarchaeology (Archeologia Postmedievale 2000), as well as in investigations of the relationship between oral history and postmedieval archaeology (Milanese 2005). This link, however, is often not understood, and it is wrongly assumed that the archaeological heritage of the contemporary age is excluded from postmedieval archaeology, whereas, on the contrary, it is completely part of it. This view also removes the misconception that industrial archaeology can entirely cover and coincide with contemporary archaeology. This is not the case, because industrial archaeology is a thematic archaeology that studies only one sector, however important, of the contemporary age. Moreover, Italian industrial archaeology, unlike more recent European and American approaches (Casella and Symonds 2007), tends not to use the methodologies of archaeological research, and archaeologists are frequently absent, as is well known, from the scientific community of this discipline (Milanese 2002). It is also for this reason that Italian postmedieval archaeology has, for almost 30 years now, declared that the archaeology of contemporary and industrial societies also falls within its field of research; indeed, there is a rural archaeology of the industrial age (unrelated to the processes of industrialization), an urban archaeology, and an archaeology of industrialized or nonindustrialized societies. Finally, Italian postmedieval archaeology has the further aim of presenting itself as an area of innovation and experimentation that is also available to other archaeologies, thanks to the wealth of different kinds of sources that it sometimes has at its disposal (Milanese 1997a:15).

Italian postmedieval archaeology is today going through a moment of liveliness and intense activity. While this is a positive situation, there remain some semantic misunderstandings due to an excessive variety of terminology, which causes confusion, disagreement, and a discussion about definitions rather than content. Faced with a definition of postmedieval archaeology that is a European reference in its multi-period and widely accepted definition, the terms modern archaeology (or of the modern age), modern and contemporary archaeology (or of the modern and contemporary ages), or contemporary archaeology (or of the contemporary age), archaeology of the present time, archaeology of the recent past, and archaeology of industrial societies are also used, often not very coherently. The real problem, however, is not terminology (although terminology is important), but the actual structured, systematic, theorized, and planned use of archaeology from the late Middle Ages to the present time.

High-quality individual studies, such as Giuliano de Felice’s (2020) landscape study of traces of 20th-century war in the Apulian Maguira, that are also highly specific and therefore limited in their topic, make important and welcome additions. What is needed, however, is a broad range of research topics concerning post-1500 societies up to the 21st century. This necessitates investigations that highlight the informative potential of the application of archaeological research methodologies. Such a point of view has long been on the research agenda of Italian postmedieval archaeology, which is, however, confronted with the difficulty of fragmenting data from intensive institutional protection activities. Some of these results are often only known by short preliminary reports in annual reports and scientific journals. The “Italian post-medieval archaeology newsletter” published in Archeologia Postmedievale in 2020, for example, consists of over 60 records of excavations and territorial investigations distributed over a good sample of Italian regions (12 out of 20). These are mainly excavations carried out in contexts of preventive archaeology and, to a lesser extent, research sites, but also surveys and case studies of epigraphy; the chronology of the contexts of these searches extends all the way to the 20th century.

The birth of the journal Archaeologia Postmedievale (1994–1997) was intended to provide a space for open and continuous discussion around the most representative topics of the new discipline, with an inclusive multi-period agenda encompassing the end of the Middle Ages to the 21st century. The aim is also to create an open and continuous tool, a space for experimenting with the application of archaeological research approaches to the material past of the most recent centuries, offering constant visibility to the archaeology of the contemporary age, but also to the archaeological study of conflict. Moreover, this extends beyond Italian borders, with World War I or World War II (Fig. 2), the Spanish Civil War, the Cold War, and the ethnic-religious wars of the late 20th century in the Balkan area after the devastating conflicts following the dissolution of Yugoslavia (1990), the Italian wars of conquest in Libya, and Rwandan massacres all finding a place in the journal.

Cover of the 22nd issue of the scientific review Archeologia Postmedievale, 2018, dedicated to the archaeology of World War I. (Image by author, 2018.) An image of human remains has been purposely concealed in this figure. To view the original journal cover, go to <https://www.insegnadelgiglio.it/prodotto/apm-archeologia-postmedievale-22-2018/>.

These wars were not only cruelly inflicted on the civilian population with ethnic cleansing strategies (De Bernardi 2018), but monumental heritage itself was destroyed to erase the identity (Perring and van der Linde 2009) in areas where today conservation, valorization, or reconstruction are dramatically intertwined in complex ways, among memory, oblivion, and economic availability, in support of different national and religious identities (Todorova 2004) in a framework of high complexity. All this without losing sight of the archaeology of the great transformations and changes produced by the introduction of gunpowder in the modern age on townscapes and rural landscapes, and the new scenarios provided by maritime archaeology on Atlantic navigation, naval architecture, and trade.

Postmedieval archaeological research dramatically increases archaeological heritage, if only for the high number of postmedieval sites, but it also offers a cultural heritage that was previously invisible, enriching the understanding and appreciation of the Italian past as well as providing a rich cultural resource for the tourist industry and economy generally. A critical discussion of the situation of postmedieval archaeology in Italy must reserve at least a reference to university training, which is fundamental for the future of this research area. To date, there are only a few Italian universities where there are specific classes in postmedieval archaeology: Venice, Sassari, Cagliari, Genoa, Siena, and Bari (Pisa and Lecce). These classes have enabled many archaeologists who now work in state structures and in the profession more broadly to develop a consistent activity in research and protection of postmedieval heritage.

Post-1500 Mediterranean Archaeology in Spain and France

The appearance of disciplinary journals is certainly an important signal to assess the consensus and visibility that an area of research has received from the scientific community. However, this step is not always binding, and in Mediterranean Europe there are different situations under the present influence of the British journal Post-Medieval Archaeology. Add a nod to Spanish and French colonial archaeology, so familiar to readers of Historical Archaeology.

In Spain, there was no scientific journal dedicated to postmedieval archaeology until 2018, when Rodis: Journal of Medieval and Postmedieval Archaeology published its first issue. The journal is published by Universitat de Girona (Catedra Roses d'Arqueologia i Patrimonio Arqueologic) and, so far, includes thematic issues dedicated to the townhouse, urban planning, port infrastructures, and closed archaeological contexts between the 16th and 17th centuries. However, the Grup de Recerca d'Arqueologia Medieval i Postmedieval (GRAMP-UB), based at the Universitat de Barcelona, had been publishing a dedicated book series, Monografies d'Arqueologia Medieval i Postmedieval, since 1995. The research group was at that time directed by Manuel Riu and was particularly devoted to the study of postmedieval ceramics. As in Italy, the study of ceramics remains a particularly strong area of Spanish postmedieval archaeology (Coll Conesa, this issue).

Similarly, professional archaeology and extensive documentation practices of preventive archaeology have also played an important role in the development of postmedieval archaeology, but so has university education. There are many Spanish universities that offer specific classes in “Arqueologia Medieval y Postmedieval,” indicating a widespread rooting of the discipline. Moreover, recent years have seen a particularly enriched education landscape, with dedicated university courses in “Arqueologia Postmedieval” being offered in Alicante, Barcelona, Granada, Jaen, Pais Vasco, and Seville. This phase of growth is the subject of recent commentaries and analyses (Belén 2017; López et al. 2017; García-Contreras Ruiz and Tejerizo-García 2021).

The last decade or so has also seen two important book-length interventions. The first is an introductory text written for Spanish university education by Juan Antonio Quirós Castillo and Bengoetxera Rementeria Belén, entitled Arqueologia III. Arqueologia Medieval y Posmedieval (Quirós Castillo and Belén 2010). It presents an overview of Spanish postmedieval archaeology, starting with aspects of terminology before examining the main research areas. The second and more recent is a volume that focuses on the situation in the Pais Vasco (Basque Country). It consists of essays edited by Idoia Grau-Sologestoa and Juan Antonio Quirós Castillo, which, collectively, aim to develop an overview and critical assessment of the archaeology of the modern age in this northern region of the Iberian Peninsula (Grau-Sologestoa and Quirós Castillo 2020). The book starts with a theoretical discussion with reference to a broad European framework of postmedieval archaeology. However, the choice of entitling it “Modern Archaeology” creates a new chronological border, as it limits the discipline’s focus to the 16th–earlier 19th centuries, excluding the era of major industrialization that encompassed the later 19th and 20th centuries, creating a partition that seems to pose more problems than it solves. Nevertheless, the book is particularly interesting and useful, as it is dedicated to in-depth research in a specific region; there are papers on classic themes, such as urban areas, rural areas, productive activities, the archaeology of death, communication routes, maritime archaeology, and coastal landscapes.

The archaeology of the Spanish Civil War has had, in the last few years, a particular impact on Spanish society, especially the research and excavation of mass graves of massacres, with strong political values and with the search for “truth” guiding the archaeological activity. The work of Alfredo Gonzalez-Ruibal (2020), in particular, has made this research accessible to an international audience. Collective political-identity processes and the social demand for justice are at the heart of Spanish Civil War archaeology; excavations of mass graves from that conflict have a strong forensic archaeological soul, and this type of archaeology in Spain is also discussed in heated parliamentary debates (Milanese 2010:106–107; Carrasco 2018; Ramos Ruiz 2018).

Although postmedieval archaeology in Spain has only recently attained a thematic scientific journal, the overall picture of post-1500 archaeological research is a lively one. In fact, there is good provision for the university teaching of postmedieval archaeology, for theoretical reflection, and for the research and protection of postmedieval archaeological heritage during professional archaeology interventions.

The situation of the archaeology of the most recent centuries in France presents another complex yet lively picture in which the issue of the current absence of a specific journal must be discussed carefully. France was the first country in Mediterranean Europe to start a specific journal of this type, Ramage: Revue d'archéologie moderne et d'archéologie générale, which was founded in 1982 and ran for a total of 14 issues until folding in 2002. This initiative was instigated by the founding editors, Philippe Bruneau and Pierre-Yves Balut, at the Institut d'art et d'archéologie—Centre d'archéologie moderne et contemporaine, Université de Paris-Sorbonne.

Looking back, Ramage appears as highly innovative in the context of French (and European) archaeology of the 1980s, with a strong methodological stance that highlighted the marginality of the classical methods of archaeological research, most notably, traditional archaeological excavation. Only nine papers in the more than 20 years of Ramage’s life were in fact dedicated to case studies related to archaeological excavations in a journal that had two fundamental preoccupations, as declared in its title: modern archaeology and general archaeology. Much attention was paid to the discipline’s relationships with the history of art, the history of archaeology, archaeological theory, and heritage management. An “undisciplined” discipline that challenged many of the fixed points of a discipline was firmly rooted, as in the rest of Europe, in the humanities. The interdisciplinary nature of post-1500 archaeology posed a shock to academia and to students themselves due to the revolutionary directions of the journal’s initiators (Bellan 2018:33–34). Although it has been out of publication for 20 years, Ramage is still a journal full of interesting insights thanks to its strongly unconventional nature. However, Ramage was also a very academic journal, distant from the concrete realities developing in French preventive archaeology during the 1980s and 1990s. An important turning point came at the end of the 1980s, when the principles of preventive archaeology were being established in France, as elsewhere on the European continent, with increasing credibility and scientific authority—a fundamental step that did not receive attention in Ramage. The journal did not discuss, for example, the spectacular scientific and media impact, even among the public, that numerous finds from World War I trenches, collective burials, and battle areas had produced in those years. The particular vivacity of French debate on the national legislation of preventive archaeology (Demoule 2002) represented a point of reference nationally and for other European countries from the perspective of overcoming rescue archaeology and forming a multi-period vision that also included post-1500 archaeology. The most important and structural outcome of this debate was the birth of the dynamic organizational structure of Inrap (Institute Nationale de Recherche Archéologique Prévéntive), established in 2002 for the management of national preventive archaeology, which is a model of great effectiveness and transparency with its extraordinary Website, a model that, unfortunately, has not been followed elsewhere in Europe.

Preventive archaeology was applied to the routes of large public railways (e.g., TGV Nord) and French motorway infrastructures (e.g., A29, A16) that intersected the Franco-German border. Yves Desfossés was the protagonist of this phase and a pioneer of World War I archaeology in France (Desfosseès et al. 2007). He emphasized the difficulties faced by the archaeologists involved in this work in 1988–1989: They were traditionally trained archaeologists, but on construction sites they had to dig the remains of military trenches, ammunition dumps, evidence of the daily lives of fighters, and, above all, the remains of soldiers who died during battles. The discovery of collective burials of many fallen soldiers had a considerable media impact, such as the well-known multiple grave site at Saint-Rémy-la-Calonne (Meuse) in 1991 that contained the burial of French writer Alain Fournier. This unexpected discovery aroused deep emotion and became an extraordinary national and international media witness that affirmed the scientific, cultural, and social value of World War I archaeology.

Inrap also boasts a remarkable Website, which, although it is not aimed specifically at the scholarly community, is an exceptional and continuously updated information tool for post-1500 archaeological excavations in France. It is the best online news source to study the French situation in relation to preventive archaeology beyond the numerous regional archaeology journals, which are, however, more difficult to consult and have a general and multi-period character. Modern and contemporary archaeology appears in this Website as one of the more vibrant areas of French preventive archaeology, with excavations and research mainly directed at conflict archaeology (World War I and World War II), production archaeology, fortifications, the archaeology of places of religious faith, and funerary archaeology.

In the continuing French debate on postmedieval/modern and contemporary archaeology, one further journal merits discussion, even though it is not thematically or chronologically specific: Les nouvelles de l'archéologie. With some dedicated dossiers, the journal has been more careful than the purely academic focus of Ramage to give theoretical reflection to the first structured experiences of French postmedieval archaeology between 2004 and 2014, although the discussion still often revolves around the issue of legitimation and the acceptance of this field of research.

Joëlle Burnouf and Florence Journot (2004:5) highlighted the still “opportuniste et dérobé de l'archéologie du passé récent”Footnote 2 character and the fragmentary nature of the data recovered via preventive archaeology, and that it promulgates postmedieval archaeology without a real research agenda. Ten years later, Séverine Hurard, Yves Roumégoux, and Dorothée Chaoui-Derieux reflected again on the definition “opportuniste et dérobé de l'archéologie du passé recent” and hypothesized a shift “[d]e l'opportunisme à la maturité”Footnote 3 (Hurard et al. 2014:3). The authors distinguish “modern archaeology,” which would still be fully on the agenda of medievalist archaeologists (a completely different position from the Italian one), from a more distant “contemporary archaeology,” which instead marks a stronger detachment from medieval archaeology and takes on a sociological and humanitarian role.

It is no coincidence that the Manuel d'archéologie médiévale et moderne by Joëlle Burnouf, Danielle Arribet-Deroin, Bruno Desachy, Florence Journot, and Anne Nissen-Jaubert (Burnouf et al. 2020) (Fig. 3), first published in 2009 but now in its second edition, associates medieval archaeology with modern archaeology. The role of preventive archaeology, such as excavations of the Louvre by Pierre-Jean Trombetta (2004), is emphasized, but also the role of the journal Ramage, with the idea of a modern archaeology based on more methodologies, including nontraditional archaeology.

In their alternative to the Manuel, Florence Journot and Gilles Bellan (2011), in Archéologie de la France moderne et contemporaine, still discuss the “opportuniste et dérobé de l'archéologie du passé recent” cited by Burnouf. Starting from this initial reference, Journot and Bellan present a national synthesis organized by research themes. This book is very useful because it presents many case studies referring to environmental archaeology, rural archaeology, urban archaeology, production and industrial archaeology, archaeology and anthropology, ceramics, road archaeology, underwater archaeology, maritime archaeology, and religiosity. The reference bibliography is very scattered in regional venues, in conference proceedings, and in journals that are not specifically post-1500 in focus, but attentive to the moving scenarios of archaeological research, such as the journal Les nouvelles de l'archéologie. The authors identify a correspondence between the definition of postmedieval archaeology, which they take into consideration, but which they consider “timid,” and modern archaeology, with a different position from the Italian idea of a postmedieval archaeology with its inclusive responsibility, from 1500 to the present time.

Another aspect that needs to be assessed is that of the training in post-1500 archaeology in French universities, which is completely neglected in the manuals and rarely mentioned elsewhere. The situation echoes the reality in which post-1500 archaeology today seems to be extremely rarely taught at French universities, with those in Paris, Nantes, and Rennes being rare exceptions.

Conclusion

The embeddedness of postmedieval archaeology in Italy, France, and Spain within a broader continental framework reflects the desire to share a common European perspective, something that has developed unevenly since the 1990s. At the same time, each nation has its own priorities, pasts, and archaeological traditions with which to contend.

The theme of the different Mediterranean and European traditions or interpretations of post-1500 archaeology is a very broad and complex subject, but it will have to be addressed in a global way. At the moment a self-referential perspective prevails, which leads individual parts of the European (or global) framework to ignore the others, also as a result of language barriers, which make it difficult for all researchers to access journals, papers, and bibliographies in German, English, French, and Italian. The solution is probably that of a translation into English of at least the most important scientific works and the development of special thematic volumes of broad international planning. However, the picture is not static. On the contrary, it is highly dynamic, just thinking of the growing international diffusion of an archaeology applied to the 20th century, up to the present, with an approach closely linked to sociology and anthropology. The extension of post-1500 archaeological research up to the present is a constitutive line of Italian postmedieval archaeology since the years of its theoretical consolidation (starting from 1994–1997), but this Italian interpretation of the term of a postmedieval archaeology without chronological barriers is ignored in the international bibliography.

Even with this difference and hybrid form, Italian postmedieval archaeology owes much to the English stratigraphic tradition, brought to Italy by numerous British research groups in the 1970s, for whom postmedieval archaeology was an accepted cultural concept. The French interpretation is still different, as has been discussed in the text, and the concept of modern archaeology should in general be further explored, as it is often also applied to a fully contemporary chronology, such as 1900. The debate is open, or, more precisely, it should be opened, without overestimating the terminological aspects of the many post-1500 archaeologies, but trying instead to look more at the aspects of content and substance.

In the case of Italian postmedieval archaeology, the last 25–30 years have witnessed important changes and advances. From the 1990s, the range of themes has expanded from preoccupations with pottery and material culture alone to include urban archaeology, thanks to the strong growth of preventive archaeology along with more recent endeavors in rural archaeology. Moreover, the development of the discipline has led to a greater awareness of postmedieval archaeology as a highly interdisciplinary research area.

From the fragmentary data generated by rescue and preventive archaeology, an era in which the archaeological record is harnessed to identify new, archaeologically anchored, historical questions is being approached. Such a transformation could not have happened without the construction and continual updating of a disciplinary research agenda. Particularly crucial to this development has been the centrality of the thematic journal Archeologia Postmedievale (1997–2022), which has provided not only a repository of data and research findings, but a nexus of communication between archaeologists practicing postmedieval archaeology in Italy and beyond.

Perhaps, most importantly, government authorities and heritage agencies have become more aware of the social and economic role postmedieval archaeology can play in the processes of urban regeneration and the enrichment of social life, as well as offering insights into rapidly changing communities and landscapes in rural, marginal, and fragile territories.

If postmedieval European archaeology in the next decade wishes to achieve a profound maturation of its own, it will be essential that European university education in this field of research is recognized as a priority in the archaeological heritage sector. A survey of the Websites of Italian, French, and Spanish universities highlights a substantial weakness in training, with only a few university courses dedicated specifically to postmedieval archaeology. The occasionality and rarity with which courses in the discipline are found indicate that most European archaeology students still do not study postmedieval archaeology. In the future, they will therefore be completely unprepared to evaluate it in the field as archaeologists in charge of protecting archaeological heritage or to design its future strategies as archaeologists dedicated more specifically to research.

Notes

Translation: opportunistic and stolen from the archaeology of the recent past.

Translation: from opportunism to maturity.

References

Andrews, David, and Denys Pringle 1977 Lo scavo dell’area sud del Convento di San Silvestro a Genova (1971–1976) (The excavation of the southern area of the Convent of San Silvestro in Genoa [1971–1976]). Archeologia Medievale 4:100–161.

Archeologia Postmedievale 2000 Primo Convegno Nazionale di Etnoarcheologia (First National Convention of Ethnoarchaeology). Special issue, Archeologia Postmedievale 4.

Bellan, Gilles 2018 Archéologie sous influence: Retours d’experience (Archaeology under influence: Feedback). Tetralogiques 23:33–46.

Bengoetxea, Belén 2017 La arqueología del mundo moderno y contemporáneo y la academia (The archaeology of the modern and contemporary world and the academy). La Linde: Revista Digital de Arqueología Profesional 8:59–83.

Blake, Hugo 2011 Professionalizzazione e frammentazione. Ricordando l’archeologia medievale nel lungo decennio 1969–1981 (Professionalization and fragmentation. Recalling medieval archaeology in the long decade 1969–1980). PCA: European Journal of Post-Classical Archaeologies 1:452–480.

Brogiolo, Gian Pietro, and Sauro Gelichi 1988 La città nell’alto medioevo Italiano: Archeologia e storia (The city in the Italian early Middle Ages: Archaeology and history). Laterza, Rome, Italy.

Burnouf, Joëlle, Danielle Arribet-Deroin, Bruno Desachy, Florence Journot, and Anne Nissen-Jaubert 2020 Manuel d'archéologie médiévale et modern (Manual of medieval and modern archaeology), 2nd edition. Armand Colin, Paris, France.

Burnouf, Joëlle, and Florence Journot 2004 L’archéologie moderne: Une archéologie opportuniste et dérobée? Dossier préparé par J. Burnouf et F. Journot (Modern archaeology: An opportunist and derailed archaeology? Dossier prepared by J. Burnouf and F. Journot). Les Nouvelles de l’archéologie 96:5–6.

Carrasco, Inmaculada 2018 Arqueologia en conflictos contemporàneos (Archaeology of contemporary conflicts). Romula 17:7–12.

Casella, Eleanor Conlin, and James Symonds (editors) 2007 Industrial Archaeology: Future Directions. Springer, New York, NY.

Courtney, Paul 2009 The Current State and Future Prospects of Theory in European Post-Medieval Archaeology. In International Handbook of Historical Archaeology, Teresita Majewski and David Gaimster, editors, pp. 161–190. Springer, New York, NY.

De Bernardi, Chiara 2018 Molila sam ih da me ubiju: Voci di donne vittime di violenze durante le guerre degli anni Novanta in Bosnia (I begged them to kill me: Voices of women victims of violence during the wars of the 1990s in Bosnia). Qualestoria. Rivista di Storia Contemporanea 46(2):110–122.

De Felice, Giuliano 2020 Archeologia di un paesaggio contemporaneo. Le guerre del Novecento nella Murgia pugliese (Archaeology of a contemporary landscape. The wars of the twentieth century in the Apulian Murgia). Edipuglia, Bari, Italy.

Demoule, Jean-Paul 2002 Rescue Archaeology: The French Way. Public Archaeology 2(3):170–177.

Desfosseès, Yves, Alain Jacques, and Gilles Prilaux 2007 Quelle archéologie pour les traces de la Grande Guerre? (What archaeology for traces of the Great War?). In L’archéologie préventive dans le monde, Jean-Paul Demoule, editor, pp. 151–162. La Découverte, Paris, France.

Francovich, Riccardo, and Marco Milanese 1987 Una nota sull'archeologia urbana in Italia (A note on urban archaeology in Italy). Urbanistica 88:13–15.

Francovich, Riccardo, and Marco Milanese 1990 Lo scavo archeologico di Montarrenti e i problemi dell'incastellamento medieval: Esperienze a confronto (The archaeological excavation of Montarrenti and the problems of the medieval fortification: Compared experiences). All’Insegna del Giglio, Florence, Italy.

García-Contreras Ruiz, Guillermo, and Carlos Tejerizo-García 2021 Más allá de los castella tutiora: La ocupación de asentamientos fortificados en el noroeste peninsular (siglos IV–VI) (Beyond the guardian castle: The occupation of fortified settlements in the northwest peninsula [4th–6th centuries]). Gerión Revista de Historia Antigua 39(2):717–745.

Gardini, Alexandre, and Marco Milanese 1979 L'archeologia urbana a Genova negli anni 1964–1978 (Urban archaeology in Genoa in the years 1964–1978). Archeologia Medievale 6:129–170.

Gonzalez-Ruibal, Alfredo 2020 The Archaeology of the Spanish Civil War. Routledge, London, UK.

Grau-Sologestoa, Idoia, and Juan Antonio Quirós Castillo (editors) 2020 Arqueología de la Edad Moderna en el País Vasco y su entorno (Archaeology of the modern age in the Vasco Country and its surroundings). Archaeopress, Oxford, UK.

Hurard Séverine, Yves Roumegouz, and Dorothéè Chaoui-Derieux 2014 L’archéologie à l’épreuve de la modernité (Archaeology put to the test of modernity). Le Nouvelles de l’archéologie 137:3–9.

Journot, Florence, and Gilles Bellan (editors) 2011 Archéologie de la France moderne et contemporaine (Archaeology of modern and contemporary France). La Découverte, Paris, France.

López, M. Dolores, Karen Álvaro, and Esther Travé 2017 GRAMP-UB: Una trayectoria de investigación y docencia en arqueología medieval y postmedieval (GRAMP-UB: A trajectory of investigation and teaching in medieval and postmedieval archaeology). La Linde: Revista Digital de Arqueología Profesional 8:84–111.

Maggi, Roberto, Carlo Montanari, and Diego Moreno (editors) 2002 L’approccio storico-ambientale al patrimonio rurale delle aree protette (The historical-environmental approach to the rural heritage of protected areas). Special issue, Archeologia Postmedievale 6.

Manacorda, Daniele 1982 Archeologia urbana a Roma: Il progetto della Crypta Balbi (Urban archaeology in Rome: The Crypta Balbi project). All’Insegna del Giglio, Florence, Italy.

Manacorda, Daniele (editor) 1984 Un “mondezzaro” del XVIII secolo. Lo scavo dell’ambiente 63 del Conservatorio di S.Caterina della Rosa (An 18th-century “garbage collector.” The excavation of room 63 of the Conservatory of St. Caterina della Rosa). All’Insegna del Giglio, Florence, Italy.

Mannoni, Tiziano 1969 Gli scarti di fornace e la cava del XVI secolo in via S. Vincenzo a Genova. Dati geologici ed archeologici. Analisi di materiali (Furnace waste and the 16th-century quarry in Via St. Vincenzo in Genoa. Geological and archaeological data. Material analysis). Atti della Società Ligure di Storia Patria, new ser., 9(2):249–272. Società Ligure di Storia Patria <https://www.storiapatriagenova.it/Docs/Biblioteca_Digitale/SB/396b22c37e8bbc6c44c30828fc127900/Estratti/f51d56936f8c5c57443932a1a341f6b4.pdf>. Accessed 21 September 2023.

Mannoni, Tiziano, and Hugo Blake 1973 L’archeologia medievale in Italia (Medieval archaeology in Italy). Quaderni Storici 8(24):833–860.

Milanese, Marco 1976 La ceramica postmedievale di Santa Maria di Castello in Genova: Contributo alla conoscenza della maiolica ligure dei secoli XVI e XVII (The postmedieval ceramics of Santa Maria di Castello in Genoa: Contribution to the knowledge of Ligurian majolica of the 16th and 17th centuries). In Atti del IX Convegno Internazionale della Ceramica, Sauro Gelichi, editor, pp. 269–310. All’Insegna del Giglio, Florence, Italy.

Milanese, Marco 1983 Archeologia medievale e postmedievale. Qualche riflessione (Medieval and postmedieval archaeology. Some reflections). Notiziario di Archeologia Medievale 36:19–20.

Milanese, Marco 1985 L'area dell'ex monastero di S.Margherita ed il versante occidentale del colle di Carignano in Genova. Campionature stratigrafiche di salvataggio d'emergenza in siti sottoposti a rinnovi urbanistici con distruzione totale delle evidenze storico-archeologiche (The area of the former monastery of St. Margherita and the western slope of the hill of Carignano in Genoa. Emergency rescue stratigraphic samples in sites undergoing urban renewal with total destruction of historical-archaeological evidence). Archeologia Medievale 12:17–128.

Milanese, Marco 1997a Archeologia postmedievale: Questioni generali per una definizione disciplinare (Postmedieval archaeology: General questions for a disciplinary definition). In Archeologia Postmedievale: L'esperienza europea e l'Italia, Marco Milanese, editor, pp. 13–17. All’Insegna del Giglio, Florence, Italy.

Milanese, Marco 1997b Quale archeologia postmedievale in Italia? (What postmedieval archaeology in Italy?). In Archeologia Postmedievale: L'esperienza europea e l'Italia, Marco Milanese, editor, pp. 79–87. All’Insegna del Giglio, Florence, Italy.

Milanese, Marco 2002 L’Archeologia postmedievale e industrial (Postmedieval and industrial archaeology). In Enciclopedia Archeologica Treccani, 4 vol., pp. 95–97. Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, Rome, Italy.

Milanese, Marco 2005 Voci delle cose. Fonti orali, archeologia postmedievale, etnoarcheologia (Voices of things. Oral sources, postmedieval archaeology, ethnoarchaeology). Archeologia Postmedievale 9:11–30.

Milanese, Marco 2010 Per un’archeologia dell’Età Contemporanea: Guerra, violenza di guerra e stragi (For an archaeology of the contemporary age: War, war violence and massacres). Archeologia Postmedievale 14:103–108.

Milanese, Marco 2014 Dall’archeologia postclassica all’archeologia postmedievale. Temi e problemi, vecchie e nuove tendenze (From postclassical to postmedieval archaeology. Themes and problems, old and new trends). In Quarant’anni di Archeologia Medievale in Italia. La rivista, i temi, la teoria e i metodi, Sauro Gelichi, editor. Special issue, Archeologia Medievale:41–40.

Milanese, Marco 2021 Ancora su Archeologia Postmedievale e cronologie. Un postulato metodologico? (More on postmedieval archaeology and chronology. A methodological postulate?). Archeologia Postmedievale 25:41–45.

Milanese, Marco (editor) 2018 L’archeologia della Prima Guerra Mondiale. Scenari, progetti, ricerche/The Archaeology of the First World War. Research Background, Projects and Case Studies. Special issue, Archeologia Postmedievale 22.

Milanese, Marco (editor) 1994–1997 Archeologia Postmedievale: L'esperienza europea e l'Italia (Postmedieval archaeology: The European experience and Italy). All’Insegna del Giglio, Florence, Italy.

Milanese, Marco, and Marco Biagini 1998 Archeologia e storia di unalpeggio dell’appennino ligure orientale. I Casoni della Pietra nella Valle Lagorara (Maissana, SP) (XVII–XX sec.) (Archaeology and history of a mountain pasture in the eastern Ligurian Apennines. The Casoni della Pietra in the Lagorara Valley [Maissana, La Spezia] [17th–20th cent.]). Archeologia Postmedievale 2:9–54.

Perring Dominic, and Sjoerd van der Linde 2009 The Politics and Practice of Archaeology in Conflict.Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites 11:197–213.

Quirós Castillo, Juan Antonio, and Bengoetxera Rementeria Belén 2010 Arqueologia III. Arqueologia Medieval y Posmedieval (Archaeology III. Medieval and Postmedieval Archaeology). UNED, Madrid, Spain.

Ramos Ruiz, Jordi 2018 La arquelogìa de la guerra civil espanola en Cataluña (The archaeology of the Spanish Civil War in Catalonia). Romula 17:133–154.

Stagno, Anna 2018 Gli spazi dell’archeologia rurale. Risorse ambientali e insediamenti nell’Appennino ligure tra XV e XXI secolo (The spaces of rural archaeology. Environmental resources and settlements in the Ligurian Appenines between the 15th and 21st centuries). All’Insegna del Giglio, Florence, Italy.

Todorova, Maria 2004 Balkan Identities, Nation and Memory. New York University Press, New York, NY.

Trombetta, Pierre-Jean 2004 Du Louvre à la Concorde: chronique archéologique d'un quartier parisien des Temps modernes. Une redécouverte majeure: Bernard Palissy (From the Louvre to the Concorde: archaeological chronicle of a Parisian district in modern times. A major rediscovery: Bernard Palissy). In La France archéologique: vingt ans d'aménagements et de découvertes, Jean-Paul Demoule, editor, pp. 210–215. Hazan, Paris, France.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Sassari within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Milanese, M. Practicing and Publishing Post-1500 Mediterranean Archaeology in Italy, Spain, and France. Hist Arch 57, 1110–1123 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41636-023-00472-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41636-023-00472-6