Abstract

This study introduces a first set of uncertainty indexes for Uruguay (a newspaper-based index and a composite index-based) to analyze how economic uncertainty impacts domestic variables in a small and open economy such as Uruguay, which is exposed to international, regional, and local uncertainty. The analysis covers approximately 15 years and uses the vector autoregressive methodological framework. The main findings suggest that economic uncertainty significantly impacts the real economy and does not impact the nominal variables. These findings which differentiate from other results found in the empirical literature, can be associated with the stability of the Uruguayan economy and the strong institutions, which may help mitigate external shocks. To assess the capability of the proposed uncertainty model to predict macroeconomic variables, we evaluate its predictive performance within the last major uncertainty shock due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The economic literature has extensively documented the adverse effects of economic uncertainty, which is crucial in macroeconomic fluctuations, mainly in consumption and investment. In the context of uncertainty, agents become cautious, skeptical, and likely to postpone investment decisions, ultimately leading to a decline in economic activity (Bernanke, 1983; Bértola et al., 2005; Dixit & Pindyck, 1994).

Two research strands related to economic uncertainty have experienced significant growth in recent years. One strand is the development of new empirical and computational methodologies aimed at constructing indicators that measure economic uncertainty. Although this subject has been present in recent decades, the 2008 global financial crisis underscored the importance of quantifying uncertainty and having indicators that measure its impact in real time to detect early signs of the economic climate and contribute to timely decision-making.

The other research strand studies the effect of uncertainty indicators on the main macroeconomic variables, such as output, employment, and investment.

Understanding this bond is essential for agents and policymakers since two main economic policy challenges are avoiding overreaction and aligning and coordinating agents’ expectations with economic policy objectives.

Most studies on the effect of economic uncertainty at a macroeconomic level focus on developed economies, while the evidence for emerging countries is incipient.

Continuing with previous efforts for emerging economies, we aim to contribute to the empirical literature on this topic by analyzing and modeling the effects of economic uncertainty in the case of Uruguay. We evaluate the predictive performance of the proposed uncertainty model within the last major uncertainty shock due to the COVID-19 pandemic to assess its capability to predict macroeconomic variables.

The Uruguayan economy presents unique characteristics. First, it is a small and open economy located in South America between two big countries, Argentina and Brazil. It is mainly a commodity exporter, taking prices from international markets, and operates under a flexible exchange rate system. Additionally, it is a dual currency economy, where the U.S. dollar plays a significant role as a reserve of value: real estate and durable goods transactions are traded in this currency.

As a small and open economy, the interrelations and interdependencies between Uruguay and its relevant trading partners sometimes lead to a lack of autonomy or loss of effectiveness of specific local economic policies. Being located amid two highly volatile economies and a member of Mercosur,Footnote 1 where Brazil is a primary destination of Uruguayan exports, Argentina plays a vital role in the Uruguayan tourism industry and the financial markets, regional uncertainty becomes considerably relevant for Uruguay. Thus, foreign policies from relevant partners can impact the Uruguayan economy due to its exposure to external shocks. Hence, although Uruguay may have a relatively well-ordered economic and institutional policy, it is exposed to international, regional, and domestic uncertainty. This makes the Uruguayan case interesting to analyze and differentiates it from other countries of the region.

This study has two purposes. First, it presents the computed uncertainty indexes for Uruguay based on different methodologies. We consider three different measures as proxies for economic uncertainty, namely, the Economic Policy Uncertainty index (EPU), the economic uncertainty index based on Latent Dirichlet Allocation modeling (LDA),Footnote 2 and the Uncertainty Composite Index (CPU). The first two are newspaper-based indexes following the methodology of Baker et al. (2016) and Azqueta-Gavaldón (2017). The third is a composite index built following the methodology of Lanzilotta et al. (2018). This methodology combines the external uncertainty captured by the EPU index of Brazil and the Global index with domestic uncertainty measured as the standard deviation of the 12-month exchange rate forecasts collected by the Central Bank of Uruguay (BCU). To the best of our knowledge, in the case of Uruguay, these are the first uncertainty indexes computed and the first research that addresses this issue using this framework.

Second, it explores the short-run impact of economic uncertainty on critical macroeconomic variables, using the three uncertainty indexes computed through vector autoregressive models’ framework with exogenous variables (VAR-X). Our findings suggest that economic uncertainty has an adverse impact on the real economy, with the most significant impact on capital goods imports and car sales. In contrast, we find no evidence of an impact on the nominal variables considered. The predictive evaluation of the model for the CPU uncertainty index shows that our model performs adequately even under periods subject to large shocks.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the literature on economic uncertainty. Section 3 presents the uncertainty index for Uruguay. Section 4 introduces the data and empirical approach used for the analysis. Section 5 presents the main results. Finally, Sect. 6 concludes the study.

2 Background

In the literature on developed countries, we find the studies of Bloom (2009), Baker et al. (2012), Baker et al. (2016), and Caldara et al. (2016), who examine the impact of uncertainty shocks in the U.S. economy. Bachmann et al. (2013) analyze the impact of uncertainty on the production level of Germany and the U.S., and Colombo (2013) studies the effect of U.S. EPU and its spillover into the European Union’s economics. In the Asian-Pacific region, we find the works of Moore (2016) and Arbatli et al. (2017), who study the impact of uncertainty in Australia and Japan, respectively. In comparative terms, uncertainty impacts have been extensively studied and are more widely known in developed than developing countries. For developing economies, studies concentrate on a few countries. For example, Godeiro and Régis de Oliveira Lima (2017), Barboza and Zilberman (2018), and Costa Ferreira et al. (2019) examine the impact of uncertainty on Brazil’s economic activity, and Cerda et al. (2017) elaborate on an uncertainty index and analyze its impact on the Chilean economy. Following the same line, Sahinoz and Cosar (2020) develop an uncertainty index and identify its impact on the Turkish economy. Additionally, Carrière-Swallow and Céspedes (2013) investigate the different responses of developed and emerging countries to uncertainty shocks, and Abid and Rault (2020) study the link between uncertainty and exchange rate for emerging markets. Although these studies differ in the uncertainty index, they rely on the vector autoregressive framework.

For developed countries, most research finds a significant impact of uncertainty on the main variables, such as growth, investment, and employment. In some cases, they also find that uncertainty increases the household saving ratio and reduces the growth of durable goods consumption, in line with the “precautionary savings” channel of uncertainty (Moore, 2016). Considering developing countries, all studies find significant impacts of uncertainty on industrial activity and investment. Some also find the impact of “wait and see” on consumption and investment decisions (Bloom, 2009; Bontempi et al., 2021; Caggiano et al., 2014).

More recently, a growing literature has focused on analyzing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on uncertainty and the economy worldwide. Leduc and Liu (2020) analyze its effects on uncertainty in the U.S. economy and find evidence that by raising uncertainty, the coronavirus affects the economy similarly to a decline in aggregate demand. Nevertheless, through the uncertainty channel, the pandemic is likely to weigh on the economy persistently beyond the short-term, also affecting the supply-side effects such as supply chain disruptions and labor shortages. However, Baker et al. (2020) point out that the effects of COVID-19 developments and policy responses on the U.S. stock market are without historical precedent. Altig et al. (2020) consider several economic uncertainty indicators for the U.S. and U.K. (stock market volatility, newspaper-based policy uncertainty, and forecaster disagreement about future gross domestic product (GDP) growth) before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. They find large uncertainty jumps in reaction to the pandemic and its economic fallout, and most indicators reach their highest values on record. They also highlight that the COVID-19 pandemic and its economic fallout lack close historic parallels because of the suddenness and massive job losses and the severity of the economic contraction relative to the size of the mortality shock. They fit VARs to estimate the relationship between output and employment to uncertainty in the U.S. data and find that COVID-size innovation represents a 19% fall in industrial production (approximately quadruples the drop during the 2008/09 crisis). They point out that ongoing high levels of uncertainty do not bode well for complete and rapid economic recovery; because elevated uncertainty generally leads to consumers and enterprises being more cautious, retarding investment, hiring, and expenditures on consumer durables.

2.1 Uncertainty Measures

A consensus exists among researchers that uncertainty is vital to understanding economic performance. They also agree that no single measure accurately captures this phenomenon. Several proxy uncertainty indicators have been defined to measure economic uncertainty and its impact on economic activity.

The seminal paper of Bloom (2009) is one of the most important contributions to the empirical literature. The author documents a strong relationship between stock market volatility and other measures of uncertainty related to real activity (e.g., the standard deviation of firm profit growth and GDP forecasts). Using stock market volatility as a proxy for economic uncertainty, the author finds that an increase in uncertainty leads to a sudden fall and a subsequent overshooting in employment, output, and productivity growth.

Measures of financial volatility are the most common and widely used indicators of uncertainty, but they are not the only ones. Other measures include discrepancies in survey-based forecasts made by experts (Ferderer, 1993) and managers (Bachmann et al., 2013; Bloom et al., 2017). The idea behind these measures is to capture the uncertainty of decision-makers, who play an essential role in investment and innovation decisions.

More recently, the uncertainty measures developed by Baker et al. (2016) set a turning point in studying the effects of uncertainty shocks on real activity. They introduce a novel indicator of economic uncertainty, the EPU index, a uniform methodology based on newspaper text searching. This indicator is currently being used in a wide range of countries in the developed and developing world. Moreover, the EPU index methodology is used to generate complementary measures. For example, Bontempi et al. (2021) estimate another uncertainty indicator using information from Internet queries. Fundação Getúlio Vargas develop a composite index based on a weighted sum of EPUs for different countries (FGV, 2016). Additionally, Ahir et al. (2019) construct a World Uncertainty Index (WUI) for 143 countries using the Economist Intelligence Unit country report with quarterly frequency. This is an uncertainty index for a panel of developed and emerging economies.

2.2 Transmission Channels

A strand of literature studies the effect of uncertainty transmission channels based on their importance for economic activity. One major branch of this literature studies how uncertainty shocks drive fluctuations and explain the volatility in the business cycle through its negative impact on consumption and investment. This line of research seeks to find a linkage between the financial and monetary sectors and the real economy. For example, Leduc and Liu (2016) study how uncertainty shocks affect aggregate economic activity through the interaction between labor search frictions and an aggregate-demand channel associated with nominal rigidities. They find that uncertainty shocks contribute to a rise in unemployment and declines in inflation and the nominal interest rate. Moreover, uncertainty can lead to an economic recession when adding search frictions.

In contrast, Punzi (2020) investigates the international transmission of uncertainty between the financial and real sectors. Here, the spillover effect arises through the banking channel, where domestic banks suffer from decreasing demand from foreign households. Finally, Abid (2019), through an ARDL model, explores the effects of EPU on exchange markets, focusing on emerging economies for two main reasons. First, they usually experience strong currency fluctuations, and second, trade structures are mainly based on commodities whose prices are exposed to significant volatility in international markets. The countries included in the study are South Korea, India, Brazil, Mexico, and Chile. The main finding is that in the long run, the uncertainty measured through EPU has a negative impact on exchange rate movements.

Ahir et al. (2019) investigate the relationship between uncertainty in output and investment. They estimate impulse response functions for a one standard deviation increase of the WUI uncertainty index, finding that an increase in uncertainty can lead to a decline in output and investment. According to these authors, the average effects mask important differences across countries depending on the level of institutional quality. Specifically, the effect of uncertainty is significant and persistent in countries with relatively lower institutional quality and is smaller and short-lived in countries with relatively high institutional quality.

Despite the increasing interest among economists in studying uncertainty shocks, most studies refer to developed economies, where financial markets are highly developed. Carrière-Swallow and Céspedes (2013) make a significant contribution, comparing the uncertainty effects on the economic activity of emerging and developed countries. Using an open-economy VAR approach, they estimate investment and private consumption response to global uncertainty shocks for forty heterogeneous countries, consisting of twenty developed and twenty emerging economies. Their results point to the different reactions of emerging and developed countries to global uncertainty shock. Regarding emerging countries, they find an average fall in investment that is approximately four times larger than in developed countries. Moreover, developing economies experience a sharp drop in private consumption, whereas developed countries do not experience such an impact. They also note that, on average, the recovery time from such a shock is much longer for emerging markets.

Delving specifically into the evidence for South American countries, we find the work of Barboza and Zilberman (2018), which studies the uncertainty effects on Brazilian economic activity, and Cerda et al. (2017), which analyzes the Chilean case. For the Brazilian case, Barboza and Zilberman (2018) construct several proxies to capture the impact of domestic and external uncertainty (measured as the uncertainty of Brazil’s main trading partners) and estimate structural VARs following Baker et al. (2016). Using monthly data from 2002 to 2016, they find that uncertainty significantly affects economic activity, especially investment. Furthermore, their results show that the effects of domestic uncertainty outweigh the effects of external uncertainty. This evidence leads them to conclude that domestic uncertainty is an essential variable as a determinant of the Brazilian economic cycle. Additionally, Costa Ferreira et al. (2019) propose an economic uncertainty measure based on news and business forecasts for the Brazilian economy (IIE-Br). They study its impact, especially in the severe economic recession of 2014–2016. They find statistically significant decreases in economic activity variables in the months following the uncertainty shock, empirically supporting that uncertainty shocks generate an economic downturn in subsequent periods.

Cerda et al. (2017) reach a similar result for the Chilean economy from 1992 to 2015. This case is of particular interest to Uruguay because Chile and Uruguay share similar characteristics, being small and open economies and mainly exporters of commodities, with the exception for Chile of copper price. Based on Baker et al. (2016), Cerda and Valente construct an economic uncertainty index similar to the EPU index using the newspaper “El Mercurio”. Through the estimation of VAR models, they find that an increase in economic uncertainty leads to a fall in GDP, investment, and employment with adverse effects on the economy, even in the long run.

So far, the results convey a clear message. First, economic uncertainty plays a significant role in determining real activity, and second, the effects on emerging economies, compared with developed countries, are significantly more profound. In particular, open and emerging economies are more vulnerable to global uncertainty and face more constraints than developed economies in finding an orderly way out. Moreover, interrelations and interdependencies among economies could facilitate receiving external uncertainty shocks and amplify domestic uncertainty in developing economies. Our study explores the possible relationship between uncertainty and some economic variables regarding Uruguay. It contributes to the scarce empirical literature on economic uncertainty for small and open economies in the developing world. In the following section, we provide insight into the available measures of uncertainty for Uruguay, which will be our input for analyzing uncertainty shocks on economic activity.

3 Uncertainty Indexes for Uruguay

A set of uncertainty indexes has been recently developed for the Uruguayan economy. This study considers three alternative domestic uncertainty indexes with a monthly frequency. Two are elaborated by Crocco et al. (2019): EPU and LDA, and one is based on our previous work, Lanzilotta et al. (2018), but developed for this study, CPU.

The first index, EPU Uruguay (Crocco et al., 2019), follows the methodology proposed by Baker et al. (2016), which consists of counting the relative monthly frequency of newspaper articles containing a trio of terms related to the economy (E), politics (P), and uncertainty (U). Here, Crocco et al. (2019) use the local newspaper “El Observador” as the source of news articles.Footnote 3

The second selected uncertainty index for Uruguay from Crocco et al. (2019) was constructed following Azqueta-Gavaldón (2017) and using an LDA model. Generally, LDA-based models are a form of text data mining and statistical machine learning, which consist in clustering words into “topics”, clustering documents into a “mixture of topics”, and then applying a Bayesian inference model that associates each document with a probability distribution of topics; where the probability distribution of words determine the topics. Specifically, LDA, following the Dirichlet distribution, initially assigns the probability \({p}_{d,t}\) that document d belongs to topic t. Using an alternative procedure based on Jagarlamudi et al. (2012) and Crocco et al. (2019) initialize the LDA index through topical seeds, which reference the same categories used in the EPU index. The idea behind this method is to add probability to each word influenced by the Dirichlet distribution and the initial topics. Therefore, a new uncertainty indicator for Uruguay is obtained through a semi-supervised machine-learning algorithm named the LDA index on the base of the newspaper “El Observador”. As far as we know, this is the first index constructed by following this methodology for Uruguay, which makes it an original contribution that expands the methodologies for developing news-based uncertainty indexes. Table 2 in the Appendix shows the final topics obtained after applying this approach.

Finally, we built a new index, CPU, following our previous work, Lanzilotta et al. (2018), that was constructed as a composite index, following the methodology proposed by Fundação Getúlio Vargas (2016). Through the weights obtained by principal components analysis, it combines the EPU of Brazil (Fundação Getúlio Vargas, 2016) and the Global EPU,Footnote 4 with the standard deviation of the 12-month forecast of the Uruguayan peso to the U.S. dollar exchange rate (calculated from a survey conducted by the BCU among economic analysts and experts).

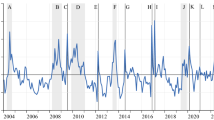

The idea behind the latest indicator is to capture the external uncertainty that relies on the evolution of the aforementioned EPU indexes and domestic uncertainty, reflected in the deviation of exchange rate expectations. As stated, Uruguay is a price taker in international markets and has operated under a flexible exchange rate system since 2002. Hence, a good approach to internal economic uncertainty is to consider deviations in exchange rate forecasts. Figure 1 shows the evolution of these three indices.Footnote 5

Figure 1 shows that the fluctuations in the three indicators of uncertainty estimated for Uruguay are similar. The series move close together, with few exceptions. The relative co-movement of the indexes with the events that occurred in the U.S. during this period is evident. For example, the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers (Sep-2008), the fiscal stimulus package (Jan-2009), and the U.S. debt downgrade (Aug-2011) are the most relevant. Other global episodes also impacted these indexes: the global financial crisis (Oct-2008), the Panama papers scandal (Mar-2016), and Brexit (Jun-2016). At a regional level, the Uruguayan uncertainty indexes spike at the time of Dilma Rousseff’s impeachment (Apr-2016). Finally, it is essential to point out that the newspaper-based uncertainty indexes in Uruguay show a peak in June 2002, when one of the greatest crises in the country’s history occurred. This implies that the Uruguayan indexes capture both domestic and global uncertainty. Figure 5 (in the Appendix) compares the evolution of the global uncertainty index with the Uruguayan uncertainty index.

4 Data and Empirical Strategy

4.1 Data

As in Albagli et al. (2019), we a priori consider a set of real and nominal variables that could (theoretically) be affected by economic uncertainty: devaluation and inflation rate, the percentage of deposits in foreign currency over total deposits, and a set of real variables: industrial production index (IPI), imports of capital goods index, employment, new car sales, and domestic value-added tax (VAT) revenue.

The selection of nominal variables reflects that Uruguay lacks a developed financial market and is a highly dollarized economy (which explains the high proportion of foreign currency deposits in domestic banks, 74% in 2019). Noteworthy, nominal variables are often the channels through which uncertainty is transmitted to real variables.

Regarding the selection of variables of real activity, we consider monthly proxies for GDP (industrial production and employment rate), capital investment (imports of capital goods), durable consumption (new car sales), and overall consumption (domestic VAT receipts); since measures of production, investment, and consumption in the National Accounts are not available monthly. Additionally, a set of global variables is introduced to account for the potential effect of strictly exogenous shocks on global activity, prices, and international uncertainty: the price index of Uruguayan exports, the Global-EPU index (GEPU), and the VIX volatility index.Footnote 6

All the series are of monthly frequency and cover approximately 15 years (February 2005 to September 2018), except for the CPU uncertainty index, which extends to December 2020. This index is constructed following our proposal in Lanzilotta et al. (2018).

A brief description of the final variables considered in the models is given in Table 3. The series are in logarithms (if applicable), and those identified as non-stationary, in their first difference.

4.2 Empirical Strategy

We propose a VAR with exogenous variables (a VAR-X model) to capture interactions between uncertainty and macroeconomic variables. Thus, we adopt the methodology used in the economic literature to study these phenomena because the causality between uncertainty and domestic macroeconomic variables is difficult to identify (Sahinoz & Cosar, 2020). As Altig et al. (2020) point out, drawing causal inferences from VARs is challenging, partly because policy, and policy uncertainty, can respond to current and anticipated future economic conditions. Despite these challenges, VARs help characterize dynamic relationships. At a minimum, they allow us to gage whether uncertainty innovations foreshadow weaker macroeconomic performance conditional on standard macro and policy variables.

The conventional reduced-form of VAR-X (p,q) models can be specified as follows:

where \(Y_{t}\) is a column vector k × 1 of endogenous variables, p is the VAR model order, \(X_{t}\) is a column vector l × 1 of exogenous variables, q is the contemporaneous values, and first q lags of the exogenous variables,Footnote 7\(A_{0}\) is a constant vector, \(u_{t}\) is a k × 1 vector of innovations (i.e., processes without serial correlation), with \(Var\left( {u_{t} } \right) = \sum\nolimits_{u} {}\) constant. The number of lags is determined by considering the last significant lag (of at least one variable). The selection of the best model is guided by the Akaike information criterion. The VAR model is estimated using ordinary least squares.

By computing the impulse response function (IRF), this model helps to analyze the impact of the variable of interest after a shock of another variable included in the VAR system. Additionally, VAR models also allow us to forecast the entire system (all the endogenous variables) and look at the future behavior of the variables of interest. Specifically, through shock simulations on the various random disturbances in the system, the IRF shows the size of the impact of uncertainty on each macroeconomic variable and its persistence over time. We adopt a Cholesky decomposition from the most exogenous to most endogenous variables to interpret the relationship between endogenous variables.

Three models are estimated for each uncertainty index. Figure 6 (in Annex) plots all endogenous variables in the final models for the analysis. To analyze the impact of COVID-19 shock, we use the CPU index, through the same VAR-X methodology, calculating forecasts of selected variables twelve steps ahead.

5 Results

5.1 Main Findings

As the nominal variables are not significant, they are excluded from the final models. This is an unexpected result, given that previous studies indicate that emerging economies tend to show significant shocks to their nominal variables (Fernández-Villaverde et al., 2011; Matsumoto, 2011).

Therefore, in the initial set of endogenous variables, the significant ones are four real variables: uncertainty index, imports of capital goods index, IPI, and new car sales. For the endogenous variables, the estimated lags are 15 [therefore, in Eq. (1), k = 4 and p = 15]. However, an alternative VAR with p = 12 and p = 3 lags is run as a robustness check of the results. The single exogenous variable Global-EPU (GEPU) is significant in the final models and lag 0 [therefore, l = 1 and q = 0 in Eq. (1)].

Figure 2 shows the IRFs after an orthogonalized shock of one standard deviation in our three versions of the local uncertainty index. All responses are shown for a 12-month horizon and are accompanied by Killian’s unbiased confidence intervals (Kilian, 1998), which explicitly corrects the bias and skewness in the impulse response estimator that arises due to small samples.Footnote 8 The order of the variables (from most exogenous to most endogenous) in all models is the same: uncertainty index, IPI, imports of capital goods index, and total sales of new cars.

The propagation of the specific shocks of the EPU and LDA uncertainty indices on themselves (included in Fig. 6 of the Appendix) is significant in the first period and then quickly stabilizes to a reduced magnitude. In the case of the CPU (whose shock is smaller than that of the EPU and LDA), stabilization to a reduced magnitude is gradual (takes longer periods).

From the analysis of the propagation path of the shocks (of the three uncertainty indices), it is noteworthy that although the signs of the responses are the same and in the expected direction, the magnitudes of the impact on the variables differ.

Considering the EPU shock, the impact is different from zero after 2 months on new car sales and after 9 months on capital goods imports. The shock has no significant and stable impact on industrial production. The responses to an uncertainty shock considering the LDA index are similar for the imports of capital goods and new car sales. Again, the IPI response is not different from 0 at the 90% confidence level (the response became significant after relaxing the statistical precision levels).

The responses of the different variables to CPU shock differ. In this last case, new car sales lose impact as more months are considered, and on the contrary, imports of capital goods show a more significant (and quicker) impact than in the other cases.

In short, the vital thing that comes out of this analysis is that uncertainty, regardless of the measure chosen, significantly impacts relevant real variables in the economy. As noted above, we discarded the nominal variables in the final model because they did not provide relevant information to the model. This may be due to the particularity of the Uruguayan economy, which is small with underdeveloped financial markets. Additionally, financial sector in Uruguay acquired an important strength after the brutal hit of the 2002 crisis,Footnote 9 where in later years, it has been subject to increased supervision and requirements. Therefore, the impact of uncertainty is mostly verified in the real variables.

5.2 Forecasting Performance

For any model studying the short-run impact of variables, it is essential to analyze its predictive power. For this purpose, we forecast all variables in the three models from October 2018 onwards (Fig. 3). We evaluate the predictive performance of each model (corresponding to each uncertainty index) by computing the root mean square error statistic for each variable for the forecast period (Table 1).

From the predictive evaluation 1 year ahead, the model that includes the CPU as an indicator of uncertainty has the best performance, whatever real variable is taken as a reference. The EPU and LDA models perform similarly.

5.3 COVID-19 Shock

To show the impact of the recent COVID-19 shock on the Uruguayan economy, we re-estimate the VAR-X model until December 2019. We forecast real variables 12 months ahead, conditional on the observed CPU index values (the uncertainty index with best performance in the predictive evaluation). Figure 4 shows the result of the model forecast, comparing it with the results of the variables from January to December 2020.

Noteworthy, the impact on these variables is limited to the first few months, and then the model can incorporate the shock into its dynamics. In the case of IPI and the sale of new cars, the series values fall outside the margins of one and two standard deviations of the original model’s forecast during the months following the pandemic outbreak in Uruguay in March 2020. Thus, albeit in different magnitude, the adverse effects of the coronavirus in terms of industrial production and durable goods (new car sales) are similar to those found in recent international literature.

On the contrary, we cannot say the same for capital goods imports, whose forecast is within the limits of the confidence interval. This result reveals that the model can accurately capture the effect of the COVID-19 crisis on this variable.

6 Final Remarks

This study contributes to the literature on economic uncertainty, analyzing the case of a South American emerging economy. We introduce the first set of uncertainty indexes calculated for Uruguay using different techniques and explore the impact of economic uncertainty on key macroeconomic variables for Uruguay.

As a small and open economy, the Uruguayan economy is considerably exposed to international and regional shocks, which have been partially mitigated in recent decades because of its strong institutions. Moreover, it is a dual currency economy in which the U.S. dollar plays a vital role as a store of value, especially in periods of volatility and uncertainty.

Our findings are broadly consistent with theories and earlier empirical studies highlighting the adverse economic effects of uncertainty shocks. The results show that the impact of economic uncertainty shocks in Uruguay is significant on almost all real variables, similar to those found in Abid (2019) and Carrière-Swallow and Céspedes (2013).

The IRFs show a significant impact of the uncertainty represented by the three indices on capital goods imports and new car sales, with marginal variations in magnitude and timing, depending on which index is shocked.

Moreover, the results of the predictive evaluation performance illustrate the usefulness of these novel measures of domestic uncertainty for anticipating the effects of adverse shocks. Additionally, among the three estimated models of the three uncertainty indicators, the one corresponding to the CPU shows the best performance. Additional effort is needed to fully understand the transmission channels of uncertainty in the case of Uruguay to design actions that could adequately mitigate the harmful effects.

We include an evaluation of the predictive performance of the CPU model for the period most affected by the COVID-19 crisis to complement this analysis. We compare the observed values of the series and the model projections with information up to December 2019, when neither the domestic nor global uncertainty index had yet registered the shock of the pandemic outbreak in Uruguay. The results show that the impact on industrial production and the consumption of durable goods is limited to the first few months. Thereafter, the model can incorporate the shock into its dynamics. In contrast, the forecast of capital goods imports falls within the confidence interval limits, revealing that the model accurately captures the effect of the COVID-19 shock on this variable. Additionally, the negative effects of the pandemic are similar to those found in the recent international literature (Altig et al., 2020; Baker et al., 2020; Leduc & Liu, 2020). Moreover, we find that only in the case of IPI and new car sales do the observed values fall outside the confidence interval of the projections, which occurs only for 2 to 3 months.

Notes

Mercosur, officially known as the Southern Common Market, is a South American trade block established by the Treaty of Asunción in 1991 and the Protocol of Ouro Preto in 1994. It comprises Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Venezuela, and Uruguay and is one of Latin America’s most essential integration processes.

The probabilistic modeling method is used in natural language processing to discover abstract topics in a collection of documents. It is also known as Topic Modeling. See Blei and Lafferty (2003) for more details.

Following the same methodology, Crocco et al. (2019) constructed another EPU index that combines the frequency of articles in three different local newspapers: “La Diaria” (from August 2009), “Búsqueda” (from April 2012), and “El Observador” (from 2002). In these indices, the overlapping period shows the same extreme events. However, in the case of the index that collects news from the three newspapers, the events appear moderate.

Cross correlation between the three indices:

EPU

1.000000

0.838326

0.562828

LDA

0.838326

1.000000

0.715700

CPU

0.562828

0.715700

1.000000

VIX: the Chicago Board Options Exchange’s CBOE Volatility Index.

The lag structure of the exogenous variables may be relaxed, allowing different lags for each variable.

IRFs were also run for a 24-month horizon, estimated with alternative shock identification methods (Generalized Impulse definition) and with a confidence level of 70%, to ensure that the responses stabilize at the end of the simulations and to check their robustness. These results are also available upon request to the authors.

In 2002, the Uruguayan economy suffered a deep crisis, which had been brewing since 1999, when as a consequence of the Russian moratorium, Brazil devalued its currency. Argentina and Uruguay remained faithful to their fixed exchange rate policy. However, in December 2001, Argentina could not pay its debts and went into default, which triggered a bank run that resulted in the freezing of bank deposits. Uruguay, with many deposits from Argentine citizens and companies, experienced a bank run, with several successive bank failures, and in July 2002, abandoned the exchange rate commitment. After that, with the substantial devaluation of the currency and the Central Bank almost without international reserves, a national bank holiday was declared, several banks were definitively closed, and the largest bank deposits were frozen. This generated a deep economic crisis, with the bankruptcy of companies, high unemployment, acceleration of inflation, and a substantial loss of real income.

References

Abid, A. (2019). Economic policy uncertainty and exchange rates in emerging markets: Short and long runs evidence. Finance Research Letters. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2019.101378

Abid, A., & Rault, C. (2020). On the exchange rate and economic policy uncertainty nexus: A panel VAR approach for emerging markets. IZA Discussion Paper No. 13365, https://ssrn.com/abstract=3627067

Ahir, H., Bloom, N., & Furceri, D. (2019). The world uncertainty index. Stanford Mimeo.

Albagli, E., Fornero, J., Fuentes, M., & Zúñiga, R. (2019). On the effects of confidence and uncertainty on aggregate demand: Evidence from Chile. Economía Chilena, 22(3), 8–33.

Altig, D., Baker, S., Barrero, J. M., Bloom, N., Bunn, P., Chen, C., & Davis, S. J. (2020). Economic uncertainty before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Public Economics, 191, 104274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104274

Arbatli, E. C., Davis, S. J., Ito, A., Miake, N., & Saiton, I. (2017). Policy uncertainty in Japan, volume 2017, issue 128. Asia and Pacific Department. IMF Working Paper. https://doi.org/10.5089/9781484300671.001

Azqueta-Gavaldón, A. (2017). Developing news-based economic policy uncertainty index with unsupervised machine learning. Economic Letters, 158, 47–50.

Bachmann, B. R., Elstner, S., & Sims, E. R. (2013). Uncertainty and economic activity: Evidence from business survey data. American Economic Association, 5(2), 217–249.

Baker, S. R., Bloom, N., & Davis, S. J. (2012). Has economic policy uncertainty hampered the recovery?. Chicago Booth Research Paper No. 12–06.

Baker, S. R., Bloom, N., & Davis, S. J. (2016). Measuring economic policy uncertainty. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 131(4), 1593–1636.

Baker, S. R., Bloom, N., Davis, S. J., Kost, K., Sammon, M., & Viratyosin, T. (2020). The unprecedented stock market reaction to COVID-19. White Paper June 2020. Becker Friedman Institute.

Barboza, R. D. M., & Zilberman, E. (2018). Os efeitos da incerteza sobre a atividade econômica no Brasil. Revista Brasileira De Economia, 72(2), 144–160.

Bernanke, B. (1983). Irreversibility, uncertainty, and cyclical investment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 98(1), 85–106.

Bértola, G., Guiso, L., & Pistaferri, L. (2005). Uncertainty and consumer durables adjustment. Review of Economic Studies, 72(4), 973–1007.

Blei, D., & Lafferty, J. (2009). Topic models. http://www.cs.columbia.edu/~blei/papers/BleiLafferty2009.pdf

Bloom, N. (2009). The impact of uncertainty shocks. Econometrica, 77(3), 623–685.

Bloom, N., Davis, S. J., Foster, L., Lucking, B., Ohlmacher, S., & Saporta Eksten, I. (2017). Business-level expectations and uncertainty. Available at SSRN 3085377.

Bontempi, M. E., Frigeri, M., Golinelli, R., & Squadrani, M. (2021). EURQ: A new web search-based uncertainty index. Economica, 88, 969–1015.

Caggiano, G., Castelnuovo, E., & Groshenny, N. (2014). Uncertainty shocks and unemployment dynamics in US recessions. Journal of Monetary Economics, 67, 78–92.

Caldara, D., Fuentes-Albero, C., Gilchrist, S., & Zakrajsek, E. (2016). The macroeconomic impact of financial and uncertainty shocks. NBER Working Paper 22058. http://www.nber.org/papers/w22058

Carrière-Swallow, Y., & Céspedes, L. F. (2013). The impact of uncertainty shocks in emerging economies. Journal of International Economics, 90, 316–325.

Cerda, R., Silva, A., & Valente, J. (2017). Impact of economic uncertainty in a small open economy: The case of Chile. Applied Economics, 50, 2894–2908. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2017.1412076

Colombo, V. (2013). Economic policy uncertainty in the US: Does it matter for the Euro area? Economics Letters, 121(1), 39–42.

Costa Ferreira, P., Vieira, R., Silva, F., & Oliveira, I. (2019). Measuring Brazilian economic uncertainty. Journal of Business Cycle Research, 15(1), 25–40.

Crocco, S., Dizioli, G., & Herrera and S. (2019). Construcción de un indicador de incertidumbre económica en base a las noticias de prensa. Tesis de Grado. Biblioteca Central de la Facultad de Ingeniería, Universidad de la República, Uruguay.

Dixit, A., & Pindyck, R. (1994). Investment under uncertainty. Princeton University Press.

Ferderer, P. J. (1993). Does uncertainty affect investment spending? Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 16(1), 19–35.

Fernández-Villaverde, J., Guerrón-Quintana, P., Rubio-Ramírez, J., & Uribe, M. (2011). Risk matters: The real effects of volatility shocks. American Economic Review, 101, 2530–2561.

Fundação Getúlio Vargas (FGV) - Instituto Brasileiro de Economia. (2016). Metodologia para o cálculo do indicador de incerteza da economia Brasil (IIE-Br), 3.

Godeiro, L., & Régis de Oliveira Lima, L. (2017). Medindo incerteza macroeconômica para o Brasil. Economia Aplicada, 21(2), 311–334. https://doi.org/10.11606/1413-8050/ea156958

Jagarlamudi, J., Daume, I., & Raghavendra, U. (2012). Incorporating lexical priors into topic models. In Proceedings of the 13th conference of the European chapter of the association for computational linguistics (pp. 204–2013).

Kilian, L. (1998). Small-sample confidence intervals for impulse response functions. Review of Economics and Statistics, 80, 218–230.

Lanzilotta, B., Mordecki, G., & Umpierrez, V. (2018). Political economic uncertainty in a small and open economy: The case of Uruguay. IECON, UDELAR, DT 05/2018. ISSN/ISBN: 1688–5090.

Leduc, S., & Liu, Z. (2016). Uncertainty shocks are aggregate demand shocks. Journal of Monetary Economics, 82, 20–35.

Leduc, S., & Liu, Z. (2020). The uncertainty channel of the coronavirus. Economic Letter. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

Matsumoto, A. (2011). Global liquidity: Availability of funds for safe and risky assets. IMF Working Paper 11/136.

Moore, A. (2016). Measuring economic uncertainty and its effects. Research Discussion Paper 2016–01. February 2016. Economic Research Department. Reserve Bank of Australia.

Punzi, M. T. (2020). The impact of uncertainty on the macro-financial linkage with international financial exposure. Journal of Economic and Business. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconbus.2020.105894

Sahinoz, S., & Cosar, E. (2020). Quantifying uncertainty and identifying its impacts on the Turkish economy. Empirica, 47(2), 365–387.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Human and Animal Rights

This research does not involve human participants and/or animals.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

See Figs. 5, 6, 7 and Tables 2, 3 and 4.

Source: https://www.policyuncertainty.com/ and Crocco et al. (2019)

Evolution of Global EPU vs. LDA URU uncertainty index.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lanzilotta, B., Merlo, G., Mordecki, G. et al. Understanding Uncertainty Shocks in Uruguay Through VAR Modeling. J Bus Cycle Res 19, 399–419 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41549-023-00081-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41549-023-00081-5