Abstract

Workplace weight discrimination is pervasive and harms both individuals and organizations. However, despite its negative effects on employees and employers, the social and psychological processes linking weight discrimination and workplace outcomes remain unclear. Rooted in evidence that people regularly dehumanize and dismiss the emotions of heavier individuals, the current work tests one socioemotional pathway linking workplace weight discrimination and professional outcomes: social pain minimization (SPM). SPM refers to feelings of emotion invalidation when people share negative social experiences with others and feel their hurts are discounted and dismissed by their colleagues. Across two studies using cross-sectional and prospective designs (Ntotal = 661), the current work provides evidence that workplace weight discrimination increased feelings of SPM, which in turn was associated with greater burnout, lower job satisfaction, and more counterproductive work behaviors. In the wake of workplace weight discrimination, subsequent SPM negatively affects workplace outcomes. For those experiencing workplace weight discrimination, mistreatment and invalidation frequently operate as a one-two punch to critical organizational outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Weight discrimination is a pervasive and far-reaching stressor associated with negative health and professional outcomes (Puhl et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2020). Higher weight individuals are stereotyped as lazy and incompetent, and these stereotypes bias professional evaluations and foster workplace mistreatment including discriminatory hiring, promotion, and termination (Roehling, 1999; Roehling et al., 2007). Further, although pervasive throughout the U.S., there is no federal legislation protecting employees from weight-based discrimination (Sabharwal et al., 2020). For many higher weight individuals, the workplace is an identity-threatening place where employees report frequent stigmatization (Puhl & Brownell, 2001; Puhl & Heuer, 2009). The stress related to weight stigma has been linked to numerous health problems (e.g., increased allostatic load, markers of cellular aging, caloric restriction, symptoms of anxiety and depression; Hunger et al., 2015, 2020, for reviews). However, despite evidence of weight discrimination’s harmful health and organizational effects, little research has identified the specific psychological and social processes linking weight discrimination and negative work outcomes.

The current research addresses these empirical gaps by examining the impact of weight discrimination on critical employee outcomes that are transmitted via social support processes and feelings of emotion invalidation, termed social pain minimization (SPM). Social pain is defined as the psychological distress caused by negative social experiences and SPM refers to feelings that social hurts have been discounted by others (Benbow et al., 2022). The current work tests whether weight discrimination triggers experiences with SPM, which then undermines work outcomes like burnout, job satisfaction, and counterproductive work behaviors (CWBs). The current work focuses on these three outcomes because of their critical role in employee well-being and job success (e.g., Judge et al., 2001; Schaufeli et al., 2008). Heavier individuals are regularly dehumanized and marginalized, which likely sets the stage for their emotions to be invalidated. As such, we hypothesized weight discrimination’s negative effects on employee performance and well-being would be partially mediated by feelings of SPM. Two studies using cross-sectional and prospective designs tested this primary hypothesis.

Social Identity Threat Framework

The current research uses a social identity threat framework to consider weight discrimination’s effect on work outcomes. Social identities stem from individuals’ belonging to various groups (e.g., race, gender, professional roles). Although membership in these social groups provides a key sense of belonging, affiliation, and fulfills central psychological needs (e.g., connectedness, purpose; Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Tajfel & Turner, 1986), social identities also include group-based stereotypes (i.e., traits and characteristics associated with social group membership). Critically, even if they do not personally endorse them, individuals are aware of stereotypes about their groups (Major & O'Brien, 2005). Moreover, since stereotype application frequently leads to discrimination (Dovidio et al., 2010), recognition of group-based stereotypes contributes to individuals’ concerns that they will be treated negatively based on their identity (Major & O'Brien, 2005; Steele et al., 2002), an experience which is termed social identity threat.

Weight-based social identity threat is caused by situational cues that people are devalued due to their weight (Hunger et al., 2015; Major & O'Brien, 2005). Consequently, in certain settings, weight stigma elicits psychological and physiological stress (e.g., increased cortisol secretion, feelings of strain; Jackson et al., 2016; Tomiyama, 2014). This identity-based stress is associated with various negative outcomes including decreased physical and mental health, reduced regulatory resources, and increased engagement in dangerous health behaviors (Hunger et al., 2015). For instance, recent data suggest that weight stigma was positively related to disordered eating, alcohol consumption, and sleep disturbances (Lee et al., 2021). These findings highlight that weight discrimination is stressful and contributes to numerous health problems.

Like other social settings, workplaces are rife with weight-based identity threats. First, there are well-documented biases against higher weight individuals in employment settings and higher weight individuals report considerable workplace weight discrimination (Vanhove & Gordon, 2014). In one study, HR professionals evaluated target individuals and judged heavier individuals to be less suitable for high prestige occupations and supervisory positions relative to thinner individuals (Giel et al., 2012). These data are further complemented by evidence that women are financially penalized for being higher weight, and some estimates suggest heavier women may earn nearly $19,000 less annually than average weight women with comparable backgrounds (e.g., educational attainment, tenure, job complexity, industry; Judge & Cable, 2011). As these findings attest, weight discrimination creates numerous barriers to success for heavier individuals.

In addition to external biases, weight stigma also creates internal concerns and stressors that hinder heavier employees’ health. For example, heavier individuals exposed to messages about pervasive weight bias in organizational contexts consumed more calorie-rich food and reported reduced self-efficacy compared to thinner participants and individuals exposed to identity-neutral information (Major et al., 2014). Moreover, merely anticipating negative weight-based judgments (even in the absence of experienced discrimination) is psychologically stressful and associated with lower self-esteem, more self-conscious emotions, and reduced executive functioning (Blodorn et al., 2016). Similarly, anticipated weight stigma can reduce heavier employees’ job efficacy (Zacher & von Hippel, 2022). Together, actual and anticipated experiences of workplace weight discrimination are stressful and impede heavier employees’ health and work success.

Social Pain Minimization as Mechanism

Social pain minimization (SPM) refers to feelings of invalidation that occur when employees share harmful interpersonal work experiences and colleagues discount their hurts. From this perspective, heavier employees encounter some painful work event (e.g., discrimination, exclusion), share their emotions with coworkers and supervisors, and ultimately feel listeners underestimate or ignore their negative emotions. For example, after hearing disparaging fat jokes in the office, heavy employees might share their hurt with colleagues, only to feel their emotions were minimized and invalidated. Thus, SPM is by definition a subjective, internal perception of insufficient social support, grounded in the lived experience of those encountering social mistreatment.

Critically, SPM is also distinct from general emotion invalidation in at least two ways: First, whereas general emotion invalidation can apply to non-social forms of misfortune (e.g., disappointing performance evaluations, anxiety surrounding unexpected household expenses, distress at dire medical diagnoses), as the name implies, SPM is inherently social and focuses on hurtful interpersonal experiences with others (e.g., disrespectful clients, unfair managers, isolating and exclusionary office politics), which threaten core psychological needs for personal value, control, and belonging (Benbow & Kunstman, 2024). Second, although general emotion invalidation can include positive emotions (e.g., joy at a promotion dismissed by coworkers; pride at landing a big client devalued by unappreciated supervisors), by centering painful events, SPM focuses exclusively on the neglect of negative emotions (e.g., anger following supervisor disrespect, sadness at being excluded from professional happy hours). Compared to general emotion invalidation, SPM focuses on interpersonal hurts and negative emotions.

Recent evidence suggests that several categories of responses can lead to feelings of SPM. Guided by Gable et al. (2004) bidimensional conception of social support, which categorizes care responses on orthogonal factors of active/passive and constructive/destructive, Benbow and Kunstman (2024) found that among Black Americans, both active-destructive (e.g., explicit emotion denial) and passive-destructive responses (e.g., apathy to distress) predicted SPM and subsequently worse mental health. Additionally, although this work linked deficits in support provisions (e.g., reassurance of worth, attachment, guidance, alliance; Cutrona & Russell, 1987) to SPM, when all these support features were entered as simultaneous predictors of SPM, passive-destructive responses and threats to personal worth emerged as the strongest unique predictors of minimization. These results suggest that in some situations, apathetic reactions and responses that threaten personal value may be especially likely to trigger SPM. In the context of weight stigma, coworkers who ignore the negative emotions of heavier employees and respond in ways that threaten personal worth (e.g., downplaying hurt feelings caused by disrespectful weight-based humor) might be particularly likely to foster weight-related SPM.

Triggered by negative social experiences like discrimination, SPM is expected to negatively affect outcomes related to work and well-being.Footnote 1 In keeping with this theorizing, recent research links racial discrimination to greater feelings of SPM and subsequently more life stress, symptoms of depression and anxiety, poorer sleep, and heightened suicidality (e.g., Benbow & Kunstman, 2024; Benbow et al., 2022; Kinkel-Ram et al., 2021; Kunstman et al., 2024). Critically, in each of these cases, SPM partially mediated discrimination’s negative effects, providing evidence it acts as a consistent mechanism by which discrimination harms health and well-being. Informed by these results, the current studies tested whether SPM shapes health and work outcomes in the context of weight stigma. Guided by past findings, we predicted that weight discrimination would set the stage for SPM and negatively affect professional outcomes.

There are several reasons to anticipate that experiencing weight-based discrimination will be associated with greater SPM. First, the dehumanization of higher weight employees may lead coworkers and supervisors to underestimate and disregard their emotions and distress. Consistent with this thinking, higher weight individuals are regularly dehumanized (Bernard et al., 2014; Jeon et al., 2019). For example, Kersbergen and Robinson (2019) found that higher weight individuals were judged to be less evolved and more animalistic than average weight individuals. Other research finds that heavier individuals are denied central human capacities (e.g., mental agency, autonomy) and seen as unfit for professional roles requiring these abilities (Sim et al., 2022). Further, fatness has been pathologized, treated as a disease (CDC, 2022), and linked to dehumanizing emotional reactions (i.e., disgust; Hodson & Costello, 2007). Indeed, heavier individuals are rated as more disgusting than thinner individuals (Vartanian, 2010), and this disgust leads people to physically and psychologically distance themselves from targeted individuals (Lieberman et al., 2012).

Second, weight stigma may lead to SPM because heavier people face considerable social marginalization. For example, heavier children and adolescents are more likely to be isolated and marginalized in their social networks relative to thinner peers (Crosnoe et al., 2008; Strauss & Pollack, 2003). Heavier individuals are also marginalized in social relationships and tend to have fewer friends and romantic partners than thinner individuals (Marathe et al., 2013; Pearce et al., 2002; Schmidt et al., 2023). As this work illustrates, higher weight seems to set the stage for greater social isolation and marginalization.

Finally, higher weight employees may be particularly susceptible to SPM because expressing anti-fat attitudes is a socially acceptable form of prejudice (e.g., Crandall et al., 2009). Weight is often perceived as a controllable aspect of identity and individuals are viewed as personally responsible for their weight (Weiner et al., 1988). That is, people believe that if they tried hard enough, heavy individuals could lose weight (Puhl & Brownell, 2003). Fueled by beliefs about weight controllability, many people, even health practitioners, endorse the notion that weight stigma may motivate heavier individuals to lose weight (Major et al., 2014, 2020). Hence, prejudice toward higher weight individuals is viewed as more acceptable than prejudice directed toward other groups (Puhl & Brownell, 2003). Yet, weight stigma actually contributes to poorer eating habits, less motivation for physical activity, and weight gain over time (for a review, see Hunger et al., 2020). Although exposure to weight stigma may heighten the motivation to lose weight, it does so out of an anxiety regarding further stigmatization and spurs the willingness to lose weight via disordered means (e.g., purging; Major et al., 2020). Further, the stress caused by weight stigma is associated with chronically elevated cortisol, which leads to increased fat storage and other health conditions (e.g., hypertension, cardiovascular disease; Tomiyama, 2014). From this perspective, beliefs that stigma can motivate and result in weight loss may encourage coworkers and supervisors to minimize the hurts and distress of heavier individuals (i.e., colleagues may believe SPM is for heavy employees’ own good).

Social Pain Minimization and Workplace Outcomes

SPM is stressful, upsetting, and expected to negatively impact workers’ health and performance. Past research documents the stressful nature of emotion invalidation and highlights how emotion invalidation increases negative affect, rumination, disrupts emotion regulation, and threatens core psychological needs (e.g., esteem; Pollak et al., 2000; Richman & Leary, 2009; Young & Widom, 2014). As this work illustrates, emotion invalidation is consistently linked with distress, poor mental health outcomes, and even suicidality (e.g., Benbow et al., 2022; Kinkel-Ram et al., 2021; Zielinski et al., 2023). Guided by these findings, the current research tests whether SPM mediates workplace weight discrimination’s effect on the following organizational outcomes: burnout, job satisfaction, and counterproductive work behaviors (CWBs).

Burnout is an important workplace health outcome characterized by emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced perceptions of personal accomplishment (Halbesleben & Bowler, 2007; Maslach et al., 2001). A meta-analysis conducted by Halbesleben (2006) found that social support resources significantly predicted all dimensions of burnout and low support environments fuel burnout. Importantly, increased burnout is associated with worse physical and mental health (Peterson et al., 2008) and workplace behaviors including absenteeism and reduced productivity (Maslach et al., 2001). Since weight discrimination and SPM are linked to stress and threats to core psychological needs (Benbow & Kunstman, 2024), we predict SPM will positively relate to burnout.

Hypothesis 1

Workplace weight discrimination will be positively related to SPM, which in turn will predict greater burnout.

Work stress (i.e., discrimination, SPM) also negatively affects job satisfaction. Due to its strong connection to performance (Judge et al., 2001), job satisfaction is one of the most important and commonly studied job attitudes and is defined as an evaluative judgment about how favorably employees view their jobs (e.g., Judge et al., 2017; Weiss, 2002). When people experience work-related stress, they are more likely to report job dissatisfaction (Gao et al., 2013). We anticipate that stress caused by weight discrimination and SPM will be associated with lower job satisfaction.

Hypothesis 2

Workplace weight discrimination will be positively related to SPM, which in turn will predict lower job satisfaction.

Finally, employees may respond to workplace stressors with CWBs (Dalal, 2005). CWBs are intentional employee behaviors that harm the organization and its members (Cullen & Sackett, 2003). CWBs may include stealing, wasting time and resources, disrupting productivity, and behaviors that create a hostile working environment (Penney & Spector, 2005). When employees experience work stress (i.e., discrimination and SPM), they may respond by engaging in CWBs to cope with strain, regain a personal sense of control, and retaliate against sources of stress and abuse (Krischer et al., 2010). CWBs are key organizational outcomes because they hinder organizational goals and cost organizations millions (Bennett & Robinson, 2000).

Hypothesis 3

Workplace weight discrimination will be positively related to SPM, which in turn will predict more CWBs.

The Current Work and Contribution

With two studies using cross-sectional and prospective designs, the current research examines the relations between workplace weight discrimination and burnout, job satisfaction, and CWBs as a function of SPM. This work offers several contributions to both social and organizational psychology. First, although workplace weight discrimination is pervasive (e.g., Wang et al., 2020), little organizational scholarship has tackled workplace weight stigma (see Lemmon et al., 2024 for recent calls for more weight-related research in I/O psychology) and even less research has identified the intervening psychological and social mechanisms linking weight stigma with negative work outcomes (cf., Gerson, 2024; Johnson & Kunstman, 2024). The current research addresses both these gaps in the empirical literature by highlighting SPM as a mechanism linking workplace weight discrimination and key indicators of workers’ health (i.e., burnout) and performance (i.e., job satisfaction, CWBs). One primary contribution of this work is that it engages the pressing but understudied phenomena of weight stigma and provides empirical evidence for SPM as a socioemotional mechanism linking weight discrimination and negative work outcomes.

Second, our work also contributes to scholarship on SPM by demonstrating that interpersonal invalidation occurs in weight-related contexts, stems from negative interactions with coworkers, and ultimately contributes to negative indicators of work health (i.e., burnout) and performance (i.e., job satisfaction, CWBs). These studies extend research on SPM beyond groups stereotyped as tough and invulnerable (e.g., Black Americans) to those facing other forms of marginalization (i.e., weight stigma) and illustrate that invalidation from coworkers—rather than primary support providers (e.g., friends, family; Benbow & Kunstman, 2024), can also damage health and work outcomes.

Finally, most research on workplace weight discrimination has focused on outcomes associated with evaluators’ judgments of heavier employees (e.g., hiring decisions, performance evaluations; Rudolph et al., 2009) rather than the firsthand experiences of individuals negatively impacted by weight discrimination. By centering the experiences of those affected by weight discrimination, the current work adds a critical first-person perspective to a literature that has primarily focused on biases in third-person judgments (Johnson & Kunstman, 2024; Rudolph et al., 2009).

Guided by a social identity threat framework, we hypothesized that workplace weight discrimination will trigger SPM, which ultimately will be positively associated with burnout and CWBs and negatively associated with job satisfaction. Study 1 tested hypotheses cross-sectionally. Study 2 then used a two-point prospective design to test workplace weight discrimination and SPM’s effects on burnout, job satisfaction, and CWBs.

Study 1

The current study provided an initial test of the hypothesized relations between workplace weight discrimination, SPM, and organizational experiences. Specifically, the current study used a cross-sectional design to examine the effects of workplace weight discrimination and SPM on burnout, job satisfaction, and CWBs.

Participants shared their work experiences with weight discrimination, SPM, burnout, job satisfaction, and CWBs. After assessing the latent structure of these measures for validity, we tested whether workplace weight discrimination and SPM would be positively related to burnout and CWBs and negatively related to job satisfaction. We further hypothesized workplace SPM would partially mediate discrimination’s effects on these organizational outcomes.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Using estimates from past research examining racism’s relation to SPM (Benbow et al., 2022), we recruited 342 full and part-time U.S. employed participants via Prolific data collection platform. We included an attention check embedded within one of the measures (i.e., “select ‘Never (1)’ to indicate you are reading and responding carefully). All participants responded correctly, yielding a final sample of 342 (Mage = 34.87, SDage = 10.93; 74.6% White, 8.8% Black, 8.2% Asian, 5% Latinx, 2.3% Bi- or Multiracial, 0.9% described an unlisted category; 58.2% female, 40.6% male, 0.9% nonbinary, 0.3% did not disclose). Subjective weight was assessed on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (very underweight) to 7 (very overweight; Hunger et al., 2018). More participants rated themselves above the scale midpoint (53.8%) than below the midpoint (6.2%), with 40.1% of participants selecting the midpoint option (i.e., about the right weight). Using correlations between the predictor, mediator, and outcome variables and their standard deviations, Monte Carlo simulation power analyses (Schoemann et al., 2017) with 5000 replications and 20,000 draws per replication indicated over 96% power to detect a significant indirect effect. Data and syntax are available at (OSF).

After providing informed consent, participants completed measures for weight discrimination and SPM (in that order). The three organizational outcome measures (i.e., burnout, job satisfaction, and CWBs) were then randomly presented.Footnote 2 Participants then completed demographics and were debriefed.

Materials

Weight Discrimination

Weight discrimination was assessed by modifying the Everyday Discrimination Scale (Williams et al., 1997) to assess workplace weight discrimination (Hunger & Major, 2015). Guided by instructions, “In your daily work life, how often do any of the following things happen because of your weight in the workplace?”, participants responded to items on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all often) to 7 (very often; α = 0.88; “You are treated with less courtesy or respect than other people are; You are called names or teased”).

Social Pain Minimization

Social pain minimization (SPM) was assessed with an eight-item measure modified to focus on workplace experiences. Participants responded on a Likert response scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree; Benbow et al., 2022; α = 0.96; When I tell coworkers and supervisors about times I’ve been treated unfairly, I feel they underestimate my hurt; coworkers and supervisors minimize my pain when I tell them about negative social experiences I’ve had). Across existing datasets, Benbow et al. (2022) measure consistently produces medium to large relations with measures of discrimination, workplace mistreatment, and incivility (rrange: 0.52-0.60), demonstrates appropriate test–retest reliability (rrange: 0.60-0.74), loads onto a single latent factor, and covaries as expected with negative work and health outcomes (e.g., burnout, stress, defensive silence; rrange: 0.36-0.41; Benbow & Kunstman, 2024; Benbow et al., 2024; Kunstman et al., 2024).

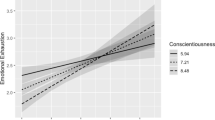

Burnout

Burnout was assessed using the 14-item Shirom-Melamed Burnout Questionnaire (SMBQ; Gerber et al., 2018; Melamed et al., 1999), which includes subscales for fatigue (e.g., I feel tired, α = 0.96), cognitive weariness (e.g., I feel I’m not thinking clearly, α = 0.92), and emotional exhaustion (e.g., I feel I am not capable of investing emotionally in coworkers and customers, α = 0.89). Participants responded on a Likert response scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Preliminary analyses examining each subscale separately produced the same results as a combined measure. To be parsimonious, we combined the subscales (α = 0.96).

Job Satisfaction

Job satisfaction was assessed with the three-item job satisfaction subscale of the Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire (Bowling & Hammond, 2008; Cammann et al., 1979). Participants responded using a Likert response scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), α = 0.94 (e.g., In general, I like working at my job).

Counterproductive Work Behaviors

Counterproductive work behaviors (CWBs) were assessed using a shortened version of the Counterproductive Work Behavior Checklist (Spector et al., 2006, 2010). Five items in the measure described behaviors targeting the organization (e.g., I purposely wasted my employer’s materials/supplies, α = 0.71) and five items targeting individuals in the organization (e.g., I started an argument with someone at work, α = 0.82). The subscales were combined, and participants responded on a Likert response scale ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (very often), α = 0.83.

Results and Discussion

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted including measures of weight discrimination, SPM, burnout, job satisfaction, and CWBs using the lavaan package in R (Rosseel, 2012). As recommended by Little et al. (2002), parcels were created for the measures of SPM, burnout, and CWBs. We created 3 parcels for burnout by averaging items from each subscale of the burnout measure. We created 4 parcels for SPM by averaging 2 items for each parcel. Finally, we created 5 parcels for CWBs by averaging 2 items for each parcel. The fit of a proposed five-factor model was assessed in which the parcels for each of the five measures were allowed to load on separate factors using robust maximum likelihood estimation. The proposed model had acceptable fit (χ2 (142) = 363.13, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.07, SRMR = 0.07), so the five measures were treated as assessing distinct factors.

Bivariate Relationships

Table 1 summarizes the bivariate correlations between study variables. As predicted, workplace weight discrimination was positively related to SPM, burnout, and CWBs and negatively related to job satisfaction. Workplace SPM was also positively related to burnout and CWBs and negatively related to job satisfaction.

Mediation Analyses

We tested an SEM model with 10,000 bias-corrected bootstrap replications to test the indirect effect of SPM on the relation between weight discrimination and burnout, job satisfaction, and CWBs. This path analysis was conducted in R using the lavaan package (Rosseel, 2012). The coefficients indicated that weight discrimination was positively related to SPM, b = 0.66, SE = 0.07, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.52, 0.79]. Further, weight discrimination also had direct effects on burnout (b = 0.37, SE = 0.10, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.18, 0.56]), job satisfaction (b = − 0.28, SE = 0.10, p < 0.001, 95% CI [− 0.49, − 0.08]), and CWBs (b = 0.11, SE = 0.05, p = 0.046, 95% CI [0.01, 0.21]).

We then examined the proposed mediation model to test if weight discrimination would lead to SPM, which would then predict burnout, job satisfaction, and CWBs (Fig. 1). The path analysis indicated SPM mediated weight discrimination’s effects on burnout, b = 0.23, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.14, 0.34], job satisfaction, b = − 0.19, SE = 0.06, p = 0.001, 95% CI [− 0.30, − 0.08], and CWBs b = 0.08, SE = 0.03, p = 0.002, 95% CI [0.04, 0.14]. More frequent experiences with workplace weight discrimination increased SPM, which then fueled burnout, decreased job satisfaction, and increased CWBs.

Social pain minimization mediates the effect of weight-based discrimination on burnout, job satisfaction, and CWBs: Study 1. Indirect effects are significant for burnout, b = .23, SE = .05, p < .001, 95% CI [.13, .34], job satisfaction, b = − .19, SE = .06, p = .001, 95% CI [− .30, − .08], and CWBs, b = .08, SE = .03, p = .002, 95% CI [.04, .15]. Note. *p ≤ .05. **p ≤ .01. ***p ≤ .001

Discussion

The current study’s results provide preliminary support for relations between workplace weight discrimination and key measures of employee performance and well-being (i.e., burnout, job satisfaction, CWBs). Further, we found that workplace weight discrimination was associated with increased feelings of SPM, which in turn predicted burnout, job satisfaction, and CWBs. That is, the more employees experienced weight-related unfairness, the greater their feeling of workplace SPM, which in turn predicted greater burnout, lower job satisfaction, and more CWBs. These data offer initial evidence for the prediction that weight discrimination and subsequent experiences of SPM are associated with negative workplace outcomes.

Although Study 1 provides support for the hypothesis that SPM mediates weight discrimination’s effects on work outcomes, this study has limitations. First, whereas modifying scales to focus on the workplace assured that participants reported on their professional (v. non-work) experiences, modifying scales can negatively affect validity (see Heggestad et al., 2019). Second, the current study was cross-sectional. To provide stronger evidence of a causal relationship in our proposed models, Study 2 employed a time-lagged design. Lagged designs offer insights on individuals’ experiences beyond a single time point to help establish temporal precedence (e.g., weight discrimination precedes SPM; Mathieu & Taylor, 2006).

Study 2

To replicate effects and provide stronger evidence for the causal role of weight discrimination and SPM on work outcomes, we collected a new sample of participants and employed a two-point lagged design. Participants completed the same measures in Study 1 at two time points across a six-week period. The six-week study duration was informed by past works suggesting short time lags (e.g., 4–6 weeks) are appropriate and even optimal for applied psychology research (Dormann & Griffin, 2015). Compared to cross-sectional designs, a lagged approach offers greater insights into temporal effects. Specifically, a lagged design will enable us to examine how experiences at Time 1 (T1) predict experiences at Time 2 (T2), helping establish a temporal relation between the measured variables. We hypothesized that across the study’s six-week period, T1 workplace weight discrimination would be associated with more SPM at T2, which would in turn mediate T1 discrimination’s effect on T2 burnout, CWBs, and job satisfaction.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Responses were again collected via the Prolific data collection platform with a new sample of employee participants. In anticipation of attrition, we oversampled at T1, collecting responses from 405 participants (Mage = 36.17, SDage = 11.92; 79.5% White, 59.8% female). Participants who completed the T1 survey were invited to participate in the second survey six weeks later, resulting in a final sample of 319 participants that closely resembled demographics of the larger T1 sample (Mage = 36.63, SDage = 11.91; 79.3% White, 6.9% Asian, 5.3% Latinx, 4.1% Black, 3.4% Bi- or Multiracial, 0.9% did not disclose; 62.4% female, 36.7% male, 0.6% transgender or nonbinary, 0.3% did not disclose). Data were Missing Completely at Random (MCAR, p = 0.60). All participants passed the study’s attention check, resulting in an analyzable sample of 319. The subjective weight ratings for the T2 sample were similar to the previous study, such that more participants rated themselves above the midpoint (52%) than below (5.3%), with 42.6% selecting the midpoint option. Using the same sensitivity analysis described for the previous study, the Monte Carlo power analyses indicated 99% power to detect a significant indirect effect.

The measures described in Study 1 were used in the current study. The T1 and T2 surveys were identical and included measures of weight discrimination (αT1 = 0.81, αT2 = 0.88) and SPM (αT1 = 0.95, αT2 = 0.97) in the workplace. Then, participants were randomly presented with the three organizational outcome measures of burnout (αT1 = 0.95, αT2 = 0.96), job satisfaction (αT1 = 0.94, αT2 = 0.93), and CWBs (αT1 = 0.83, αT2 = 0.82). Participants reported demographic information and received a virtual debriefing statement.

Results and Discussion

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

We first conducted a CFA where measures of weight discrimination, SPM, burnout, job satisfaction, and CWBs loaded on their respective factors using the lavaan package in R (Rosseel, 2012). Like Study 1, we created 3 parcels for burnout by averaging items from each subscale of the burnout measure. We created 4 parcels for SPM by averaging 2 items for each parcel. Finally, we created 5 parcels for CWBs by averaging 2 items for each parcel. The fit of a proposed five-factor model was acceptable (χ2 (142) = 469.94.13, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.08, SRMR = 0.06), suggesting that the five measures were distinct from one another.

Bivariate Relationships

Table 2 presents the bivariate relationships between the weight discrimination, SPM, and organizational outcome measures at both time points. Consistent with Study 1, weight discrimination was positively correlated with SPM, and SPM was positively associated with burnout and CWBs and negatively related to job satisfaction.

Mediation Analyses

We then tested the mediating effect of SPM on the relation between weight discrimination and the three outcome variables. To test this model, we used an SEM approach with 10,000 bias-corrected bootstrap replications (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). This analysis was conducted in R using the lavaan package (Rosseel, 2012). For this analysis, we entered the T1 weight discrimination factor as the predictor, T2 SPM as the mediator, and T2 constructs of burnout, job satisfaction, and CWBs as outcomes. Additionally, we controlled for T1 scale scores of the three outcome variables. In line with predictions, T1 weight discrimination was positively related to T2 SPM, b = 0.64, SE = 0.08, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.48, 0.80]. None of the direct effects of T1 weight discrimination significantly predicted the three outcomes (i.e., burnout, job satisfaction, and CWBs).

Turning to the proposed mediation model of weight discrimination operating through SPM to impact burnout, job satisfaction, and CWBs (see Fig. 2), the path analysis identified a significant indirect effect of T1 weight discrimination on T2 burnout through T2 SPM, b = 0.14, SE = 0.04, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.07, 0.21]). The path analysis also identified a significant indirect effect of T1 weight discrimination on T2 job satisfaction through T2 SPM, b = -0.08, SE = 0.03, p = 0.002, 95% CI [-0.13, -0.03]). Finally, there was a significant indirect effect of T1 weight discrimination on T2 CWBs through T2 SPM, b = 0.06, SE = 0.02, p = 0.001, 95% CI [0.02, 0.10]). T1 weight discrimination operated through T2 SPM to predict increased burnout and CWBs and decreased job satisfaction.

T2 Social pain minimization mediates the effect of T1 weight-based discrimination on T2 burnout, job satisfaction, and CWBs: Study 2. Indirect effects are significant for burnout, b = .14, SE = .04, p < .001, 95% CI [.07, .22], job satisfaction, b = − .08, SE = .03, p = .012, 95% CI [− .15, − .02], and CWBs, b = .06, SE = .02, p = .005, 95% CI [.02, .10]. We also tested the mediating effect of T1 SPM on the relationship between T1 weight-based discrimination and burnout, job satisfaction, and CWBs. Our results indicated that T1 SPM did not mediate the relationship between weight-based discrimination and any of the three outcomes. Note. *p ≤ .05. **p ≤ .01. ***p ≤ .001

Discussion

The current results replicate and extend the findings from Study 1. Specifically, these results provide stronger evidence for the proposed relations between workplace weight discrimination, SPM, and downstream work outcomes. Across the study’s six-week period, workplace weight discrimination was positively associated with SPM, which predicted decreased job satisfaction and increased burnout and CWBs. In keeping with our integrated COR and social identity framework, these data provide evidence that identity-related stressors (i.e., workplace weight discrimination) set the stage for emotion invalidation, which ultimately negatively impacts workplace health, attitudes, and behavior.

General Discussion

Weight discrimination is a common and damaging form of workplace mistreatment (Roehling et al., 2007). Coworkers and supervisors perpetrate weight discrimination and this mistreatment occurs across several critical employment contexts (e.g., selection, promotion, termination; Puhl & Brownell, 2006; Roehling, 1999). Despite these documented harms, little organizational research has engaged workplace weight stigma (see Lemmon et al., 2024 for calls for more research), and even less scholarship has considered intervening psychological processes that lead weight discrimination to harm work outcomes. The current research addresses these key gaps in the research literature by providing evidence for a socioemotional mechanism linking workplace weight discrimination and negative work experiences: social pain minimization. Although social support processes are sometimes considered as moderators of discrimination’s effects (e.g., Ajrouch et al., 2010), given the inherent dependency between experiencing social pain (i.e., discrimination) and having that pain minimized (i.e., an experienced deficit in social support), the current work considered SPM as a mediator of discrimination’s damaging effects on work life. We hypothesized that weight discrimination would be positively related to SPM, which would then predict greater burnout, lower job satisfaction, and greater CWBs. Two studies using cross-sectional and prospective designs provide consistent support for these predictions.

Study 1 provided initial evidence of the hypothesized links between workplace weight discrimination, SPM, and employee performance and well-being. Workplace weight discrimination positively related to SPM from coworkers and supervisors. In turn, workplace SPM mediated weight discrimination’s effects, such that workplace minimization predicted greater burnout, lower job satisfaction, and more CWBs. Study 2 then tested these hypotheses with a prospective design and found more weight discrimination at T1 predicted greater SPM at T2, which in turn predicted increased burnout and CWBs and decreased job satisfaction at T2. Altogether, this work identifies SPM as a mediating mechanism that partially explains weight discrimination’s negative effects on workplace outcomes.

Implications

The current research makes several contributions to research on workplace weight discrimination, SPM, and organizational outcomes. First and foremost, the current work engages weight stigma, a pervasive but understudied workplace problem. Moreover, the current research provides evidence for SPM as a socioemotional mechanism linking weight discrimination and negative indicators of workers’ health (i.e., burnout) and performance (i.e., job satisfaction, CWBs). This empirical evidence both answers recent calls to generate more organizational weight-related research (Lemmon et al., 2024) and provides additional evidence for the rarely studied psychological processes that link weight discrimination and negative work outcomes.

Second, the current work extends research on SPM by providing evidence for its damaging effects in the context of weight stigma and in the workplace. Theoretically, this extension is valuable because it illustrates that SPM is not exclusive to groups stereotyped as tough, strong, and invulnerable (i.e., Black Americans), but also extends to group members that face dehumanization and other forms of stigma (i.e., heavy individuals). Stereotypes and stigma yield many paths to SPM. Practically, this workplace extension is noteworthy because it illustrates that work interactions can also fuel SPM and its downstream consequences. Heretofore, SPM research has tacitly assumed that invalidation stemmed primarily from key social support providers (i.e., friends, family, romantic partners; Benbow & Kunstman, 2024), whereas these results illustrate that SPM also occurs at the hands of coworkers and supervisors. SPM isn’t limited to friends and family. Coworker invalidations are also damaging. These results advance scholarship on SPM by providing evidence that interpersonal invalidation occurs in the contexts of both weight stigma and the workplace, ultimately impacting workers’ health via burnout and key indicators of job performance like job satisfaction and CWBs.

Third, the current work contributes to research on workplace weight discrimination by centering the firsthand experiences of heavier employees. By comparison, past research has largely focused on perpetrators’ biases against heavy individuals (e.g., discriminatory judgments about the hire-ability and promotability of heavier employees; Rudolph et al., 2009). Although these findings are valuable for understanding how weight discrimination is perpetrated, the tendency to focus on evaluators’ perspectives fails to fully account for higher-weight employees’ experiences (Johnson & Kunstman, 2024). As such, the current work centers the perspectives of heavier employees to better understand and appreciate their complex workplace experiences. Experiencers’ perspectives are critical to a comprehensive understanding of workplace weight discrimination.

Finally, the current research offers insights for practitioners to develop interventions addressing workplace weight discrimination and SPM. Since the current work highlights that colleagues may fail to validate the negative emotional experiences of heavier employees, practitioners may use empathy and allyship initiatives to reduce pain minimization. Past research finds that empathy-based interventions (e.g., enhancing an empathy mindset, perspective-taking, developing cultures of appreciation) both reduce discrimination and foster healthier and more supportive workplaces (e.g., Dovidio et al., 2010; Nowack & Zak, 2020). Similarly, allyship programs, which aim to help workers with dominant identities (e.g., White individuals, average weight persons) consider their privilege, interrupt systems of workplace inequity, and amplify the voices of coworkers from stigmatized groups (Erskine & Bilimoria, 2019), have also been linked to less discriminatory and more fulfilling workplaces (e.g., Ashburn-Nardo et al., 2008; Collier-Spruel & Ryan, 2024). Encouraging active allyship may be one means of reducing both workplace weight discrimination and the SPM experienced by heavy employees. For example, allyship behaviors that challenge common assumptions about the controllability of weight and weight-related stereotypes and recognize the humanity, emotions, and lived experiences of heavier employees may be one way to combat discrimination and SPM (Waterbury et al., 2024). By providing avenues for considering the emotional experiences of heavier employees and validating those experiences by confronting weight stigma, empathy and allyship programs may reduce workplace weight discrimination, SPM, and their harmful effects.

Limitations and Future Directions

Limitations of the current work offer opportunities for future research. The current work is limited by the use of self-report measures to examine employee experiences and behaviors. Although common practice, bias is a concern with self-report measures (Spector, 1994), particularly for indices of socially undesirable behaviors in the workplace (e.g., CWBs; Donaldson & Grant-Vallone, 2002). Despite concerns, meta-analytic comparisons of self and other-reported CWBs support the acceptability of using self-reports of CWBs, and self-reports may actually be more accurate and comprehensive than other-reported CWBs (Berry et al., 2012). That said, future research might use alternative methods for assessing CWBs (e.g., supervisor and coworker evaluations). Further, when studying encounters with mistreatment and emotion invalidation, self-report is necessary to assess the constructs of interest.

Another limitation of the current work is the use of cross-sectional and two wave prospective designs. Cross-sectional designs are limited by the potential for spurious correlations (Spector, 2019). Additionally, Study 2 used only two waves of data collection, and most researchers agree that longitudinal results are better served by at least three measurement waves (Ployhart & Ward, 2011). Although two time points offer some insight into temporal effects by controlling for T1 outcome variables, this design cannot assess nonlinear relations between variables across time (Rogosa, 1995). To test for non-linear effects, future research might employ a true longitudinal design with at least three waves of measurement. Future research might also pursue experimental approaches to understanding these relationships, as interventions and manipulations offer systematic tests of causal relations (Spector, 2019). For example, compared to experimental controls, manipulations that signal workplace weight stigma (e.g., weight-based workplace wellness plans; Täuber et al., 2018) might also increase anticipated SPM and undermine workplace expectations. Together, future work using longitudinal and experimental methods might provide stronger causal evidence for relations underlying the current work.

Since research on SPM has to date focused exclusively on visible identities (e.g., race, weight), future research should explore minimization among members of groups with concealable identities (e.g., sexuality; gender-identity; neurotypicality). Competing predictions emerge for identity visibility. From one perspective, visible cues to group membership (e.g., skin tone, body size) may cue the rapid cognitive activation of group stereotypes that results in greater SPM for members of visible v. concealable identities. Alternatively, there is also considerable evidence that actively concealing central social identities (e.g., sexuality, gender-identity) is both stressful and isolating (e.g., Jones & King, 2014; Newheiser & Barreto, 2014; Newheiser et al., 2017), which directly undermines feelings of authenticity and likely sets the stage for the invalidation of both emotions and identity (e.g., Morgenroth et al., 2024). Hence, although the pathways may differ, there’s reason to predict that individuals with concealable identities may regularly experience SPM. Future research should investigate SPM among individuals with concealable social identities.

Future work might consider factors that moderate the relation between weight discrimination, SPM, and workplace outcomes. For instance, worker individual differences (e.g., self-esteem, personal coping strategies) might moderate the relation between weight discrimination and SPM and workplace outcomes (Corning, 2002; Noh & Kaspar, 2003). Past work finds personal and collective self-esteem and effective coping strategies (e.g., confrontation) buffer discrimination’s negative effects on mental health (Noh & Kaspar, 2003; Kong, 2016). Moreover, although research on grievance structures and reporting mechanisms can be mixed (Burris et al., 2013), procedural justice research suggests processes that empower employees’ voice can provide organizational support in the wake of discrimination (e.g., Hershcovis et al., 2010). Workplace structures that emphasize employee voice and allyship might buffer against the organizational costs of workplace weight discrimination. Future work should examine the worker and organizational moderators of weight stigma, SPM, and its negative outcomes.

Concluding Remarks

Weight discrimination is an unfortunate yet common work experience (Vanhove & Gordon, 2014). The current studies provide consistent support for one socioemotional mechanism underlying weight discrimination’s negative organizational effects: social pain minimization. In the wake of workplace weight discrimination, minimization was associated with higher burnout, lower job satisfaction, and more CWBs. These findings highlight the need to protect heavier employees from dual stressors of weight discrimination and social pain minimization at work and better appreciate the complex social and emotional experiences of individuals with stigmatized identities in the workplace.

Data Availability

Notes

In comparison to work that treats social support as a moderator of discrimination’s effects (e.g., Ajrouch et al., 2010), the current work considers SPM as a mediating mechanism that links weight discrimination and workplace outcomes. We consider SPM as a mediator because of the inherent dependency between social pain and its subsequent minimization. Painful social events must occur for emotions to be subsequently minimized. As such, we treat SPM as a mediator, because individuals must first have a negative experience that leads them to seek support and ultimately encounter SPM. See Butler et al. (2018) and Prelow et al. (2006) for other conceptions of social support as mediators of discrimination’s effects on health and well-being.

The current research is part of a larger project that investigated weight discrimination and health and workplace outcomes. Additional measures related to health (e.g., sleep) were included in the survey, and data for these measures can be requested by contacting the corresponding author.

References

Ajrouch, K. J., Reisine, S., Lim, S., Sohn, W., & Ismail, A. I. (2010). Perceived everyday discrimination and psychological distress: Does social support matter? Ethnicity & Health, 15(4), 417–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2010.484050

Ashburn-Nardo, L., Morris, K. A., & Goodwin, S. A. (2008). The confronting prejudiced responses (CPR) model: Applying CPR in organizations. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 7(3), 332–342. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2008.34251671

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529.

Benbow, K.L, Sawhney, G., & Kunstman, J.W. (2024, invited revision). Incivility toward black employees fuels social pain minimization and defensive silence.

Benbow, K. L., & Kunstman, J. W. (2024). Quantity and quality: Dimensions and provisions of social support inform the role of social pain minimization in the discrimination-to-mental health relation among Black Americans. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 43(1), 81–102. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2024.43.1.81

Benbow, K. L., Smith, B. L., Tolbert, K. J., Deska, J. C., & Kunstman, J. W. (2022). Race, social pain minimization, and mental health. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 25(7), 1861–1879. https://doi.org/10.1177/13684302211040864

Bennett, R. J., & Robinson, S. L. (2000). Development of a measure of workplace deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(3), 349–360. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.3.349

Bernard, P., Mangez, N., & Klein, O. (2014). Obese people = Animals? Investigating the implicit “animalization” of obese people. Romanian Journal of Applied Psychology, 16(2), 40–44.

Berry, C. M., Carpenter, N. C., & Barratt, C. L. (2012). Do other-reports of counterproductive work behavior provide an incremental contribution over self-reports? A meta-analytic comparison. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(3), 613–636. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026739

Blodorn, A., Major, B., Hunger, J., & Miller, C. (2016). Unpacking the psychological weight of weight stigma: A rejection-expectation pathway. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 63, 69–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2015.12.003

Bowling, N. A., & Hammond, G. D. (2008). A meta-analytic examination of the construct validity of the Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire Job Satisfaction Subscale. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 73(1), 63–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2008.01.004

Burris, E. R., Detert, J. R., & Romney, A. C. (2013). Speaking up vs. being heard: The disagreement around and outcomes of employee voice. Organization Science, 24(1), 22–38. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1110.0732

Butler, L. D., Maguin, E., & Carello, J. (2018). Retraumatization mediates the effect of adverse childhood experiences on clinical training-related secondary traumatic stress symptoms. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 19(1), 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2017.1304488

Cammann, C., Fichman, M., Jenkins, D., & Klesh, J. (1979). The Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire. Unpublished Manuscript, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2022). Causes of obesity. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/basics/causes.html. Accessed May 2023.

Collier-Spruel, L. A., & Ryan, A. M. (2024). Are all allyship attempts helpful? An investigation of effective and ineffective allyship. Journal of Business and Psychology, 39(1), 83–108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-022-09861-9

Corning, A. F. (2002). Self-esteem as a moderator between perceived discrimination and psychological distress among women. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 49(1), 117–126. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.49.1.117

Crandall, C. S., Merman, A., & Hebl, M. (2009). Anti-fat prejudice. In T. D. Nelson (Ed.), Handbook of prejudice, stereotyping, and discrimination (pp. 469–487). Psychology Press.

Crosnoe, R., Frank, K., & Mueller, A. S. (2008). Gender, body size and social relations in American high schools. Social Forces, 86(3), 1189–1216. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.0.0004

Cullen, M. J., & Sackett, P. R. (2003). Personality and counterproductive workplace behavior. Personality and Work: Reconsidering the Role of Personality in Organizations, 14(2), 150–182.

Cutrona, C. E., & Russell, D. W. (1987). The provisions of social relationships and adaptation to stress. Advances in Personal Relationships, 1(1), 37–67.

Dalal, R. S. (2005). A meta-analysis of the relationship between organizational citizenship behavior and counterproductive work behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 1241. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1241

Donaldson, S. I., & Grant-Vallone, E. J. (2002). Understanding self-report bias in organizational behavior research. Journal of Business and Psychology, 17(2), 245–260. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1019637632584

Dormann, C., & Griffin, M. A. (2015). Optimal time lags in panel studies. Psychological Methods, 20, 489–505. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000041

Dovidio, J. F., Johnson, J. D., Gaertner, S. L., Pearson, A. R., Saguy, T., & Ashburn-Nardo, L. (2010). Empathy and intergroup relations. In M. Mikulincer & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Prosocial motives, emotions, and behavior: The better angels of our nature (pp. 393–408). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/12061-020

Erskine, S. E., & Bilimoria, D. (2019). White allyship of Afro-Diasporic women in the workplace: A transformative strategy for organizational change. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 26(3), 319–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051819848993

Gable, S. L., Reis, H. T., Impett, E. A., & Asher, E. R. (2004). What do you do when things go right? The intrapersonal and interpersonal benefits of sharing positive events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(2), 228–245. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.2.228

Gao, Y., Shi, J., Niu, Q., & Wang, L. (2013). Work–family conflict and job satisfaction: Emotional intelligence as a moderator. Stress and Health, 29(3), 222–228. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2451

Giel, K. E., Zipfel, S., Alizadeh, M., Schäffeler, N., Zahn, C., Wessel, D., et al. (2012). Stigmatization of obese individuals by human resource professionals: an experimental study. BMC Public Health, 12, 1–9.

Gerber, M., Colledge, F., Mücke, M., Schilling, R., Brand, S., & Ludyga, S. (2018). Psychometric properties of the Shirom-Melamed Burnout Measure (SMBM) among adolescents: Results from three cross-sectional studies. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1841-5

Gerson, M. J. (2024). Acknowledging the ramifications of weight-based stereotype threat in the workplace. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 17(1), 121–125. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2023.88

Halbesleben, J. R. (2006). Sources of social support and burnout: A meta-analytic test of the conservation of resources model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(5), 1134–1145. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.5.1134

Halbesleben, J. R., & Bowler, W. M. (2007). Emotional exhaustion and job performance: The mediating role of motivation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(1), 93–106. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.1.93

Heggestad, E. D., Scheaf, D. J., Banks, G. C., Monroe Hausfeld, M., Tonidandel, S., & Williams, E. B. (2019). Scale adaptation in organizational science research: A review and best-practice recommendations. Journal of Management, 45(6), 2596–2627. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206319850280

Hershcovis, M. S., Parker, S. K., & Reich, T. C. (2010). The moderating effect of equal opportunity support and confidence in grievance procedures on sexual harassment from different perpetrators. Journal of Business Ethics, 92, 415–432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0165-2

Hodson, G., & Costello, K. (2007). Interpersonal disgust, ideological orientations, and dehumanization as predictors of intergroup attitudes. Psychological Science, 18(8), 691–698. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01962.x

Hunger, J. M., Blodorn, A., Miller, C. T., & Major, B. (2018). The psychological and physiological effects of interacting with an anti-fat peer. Body Image, 27, 148–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2018.09.002

Hunger, J. M., & Major, B. (2015). Weight stigma mediates the association between BMI and self-reported health. Health Psychology, 34(2), 172. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000106

Hunger, J. M., Major, B., Blodorn, A., & Miller, C. T. (2015). Weighed down by stigma: How weight-based social identity threat contributes to weight gain and poor health. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 9(6), 255–268. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12172

Hunger, J. M., Smith, J. P., & Tomiyama, A. J. (2020). An evidence-based rationale for adopting weight-inclusive health policy. Social Issues and Policy Review, 14(1), 73–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/sipr.12062

Jackson, S. E., Kirschbaum, C., & Steptoe, A. (2016). Perceived weight discrimination and chronic biochemical stress: A population-based study using cortisol in scalp hair. Obesity, 24(12), 2515–2521. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.21657

Jeon, Y. A., Koh, H. E., Ahn, J., & Coleman, R. (2019). Stigma activation through dis-identification: Cognitive bias triggered by media photos of people with obesity. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 47, 485–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909882.2019.1682181

Johnson, B. N., & Kunstman, J. W. (2024). Organizational research on weight stigma must center targets’ perspectives. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 17(1), 115–120. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2023.84

Jones, K. P., & King, E. B. (2014). Managing concealable stigmas at work: A review and multilevel model. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1466–1494.

Judge, T. A., Thoresen, C. J., Bono, J. E., & Patton, G. K. (2001). The job satisfaction–job performance relationship: A qualitative and quantitative review. Psychological Bulletin, 127(3), 376–407. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0033-2909.127.3.376. Accessed May 2023.

Judge, T. A., Weiss, H. M., Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D., & Hulin, C. L. (2017). Job attitudes, job satisfaction, and job affect: A century of continuity and of change. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(3), 356–374. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/apl0000181. Accessed May 2023.

Judge, T. A., & Cable, D. M. (2011). When it comes to pay, do the thin win? The effect of weight on pay for men and women. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(1), 95–112. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020860

Kersbergen, I., & Robinson, E. (2019). Blatant dehumanization of people with obesity. Obesity, 27, 1005–1012. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22460

Kinkel-Ram, S. S., Kunstman, J., Hunger, J. M., & Smith, A. (2021). Examining the relation between discrimination and suicide among Black Americans: The role of social pain minimization and decreased bodily trust. Stigma and Health. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000303

Kong, D. T. (2016). Ethnic minorities’ paranoia and self-preservative work behaviors in response to perceived ethnic discrimination, with collective self-esteem as a buffer. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 21(3), 334–351. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/ocp0000013. Accessed May 2023.

Krischer, M. M., Penney, L. M., & Hunter, E. M. (2010). Can counterproductive work behaviors be productive? CWB as emotion-focused coping. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15(2), 154–166. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/a0018349. Accessed May 2023.

Kunstman, J.W., Kinkel-Ram, S.S., Benbow, K.L., Hunger, J.M., Smith, A.R., Troop-Gordon, W., Nadorff, M.R., & Maddox, K.B. (2024, invited revisions). Social pain minimization mediates discrimination’s effect on sleep.

Lee, K. M., Hunger, J. M., & Tomiyama, A. J. (2021). Weight stigma and health behaviors: Evidence from the Eating in America Study. International Journal of Obesity, 45(7), 1499–1509. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-021-00814-5

Lemmon, G., Jensen, J. M., & Kuljanin, G. (2024). Best practices for weight at work research. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 17(1), 85–105. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2023.50

Lieberman, D. L., Tybur, J. M., & Latner, J. D. (2012). Disgust sensitivity, obesity stigma, and gender: Contamination psychology predicts weight bias for women, not men. Obesity, 20(9), 1803–1814. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2011.247

Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., & Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 151–173. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_1

Major, B., Hunger, J. M., Bunyan, D. P., & Miller, C. T. (2014). The ironic effects of weight stigma. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 51, 74–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2013.11.009

Major, B., & O’Brien, L. T. (2005). The social psychology of stigma. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 393–421.

Major, B., Rathbone, J. A., Blodorn, A., & Hunger, J. M. (2020). The countervailing effects of weight stigma on weight-loss motivation and perceived capacity for weight control. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 46(9), 1331–1343. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167220903184

Marathe, A., Pan, Z., & Apolloni, A. (2013). Analysis of friendship network and its role in explaining obesity. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology (TIST), 4(3), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1145/2483669.2483689

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 397–422.

Mathieu, J. E., & Taylor, S. R. (2006). Clarifying conditions and decision points for mediational type inferences in organizational behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(8), 1031–1056.

Melamed, S., Ugarten, U., Shirom, A., Kahana, L., Lerman, Y., & Froom, P. (1999). Chronic burnout, somatic arousal and elevated salivary cortisol levels. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 46(6), 591–598. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(99)00007-0

Morgenroth, T., van der Toorn, J., Pliskin, R., & McMahon, C. E. (2024). Gender nonconformity leads to identity denial for cisgender and transgender individuals. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 15(1), 46–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/19485506221144148

Newheiser, A. K., & Barreto, M. (2014). Hidden costs of hiding stigma: Ironic interpersonal consequences of concealing a stigmatized identity in social interactions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 52, 58–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2014.01.002

Newheiser, A. K., Barreto, M., & Tiemersma, J. (2017). People like me don’t belong here: Identity concealment is associated with negative workplace experiences. Journal of Social Issues, 73(2), 341–358. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12220

Noh, S., & Kaspar, V. (2003). Perceived discrimination and depression: Moderating effects of coping, acculturation, and ethnic support. American Journal of Public Health, 93(2), 232–238.

Nowack, K., & Zak, P. (2020). Empathy enhancing antidotes for interpersonally toxic leaders. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 72(2), 119–133. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/cpb0000164. Accessed May 2023.

Pearce, M. J., Boergers, J., & Prinstein, M. J. (2002). Adolescent obesity, overt and relational peer victimization, and romantic relationships. Obesity Research, 10(5), 386–393. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2002.53

Penney, L. M., & Spector, P. E. (2005). Job stress, incivility, and counterproductive work behavior (CWB): The moderating role of negative affectivity. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 26(7), 777–796. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.336

Peterson, U., Demerouti, E., Bergström, G., Samuelsson, M., Åsberg, M., & Nygren, Å. (2008). Burnout and physical and mental health among Swedish healthcare workers. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 84–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04580.x

Ployhart, R. E., & Ward, A. K. (2011). The “quick start guide” for conducting and publishing longitudinal research. Journal of Business and Psychology, 26, 413–422. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-011-9209-6

Pollak, S. D., Cicchetti, D., Hornung, K. G., & Reed, A. (2000). Recognizing emotion in faces: Developmental effects of child abuse and neglect. Developmental Psychology, 36(5), 679–688. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.36.5.679

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891.

Prelow, H. M., Mosher, C. E., & Bowman, M. A. (2006). Perceived racial discrimination, social support, and psychological adjustment among African American college students. Journal of Black Psychology, 32, 442–454. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095798406292677

Puhl, R. M., Andreyeva, T., & Brownell, K. D. (2008). Perceptions of weight discrimination: Prevalence and comparison to race and gender discrimination in America. International Journal of Obesity, 32, 992–1000. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2008.22

Puhl, R., & Brownell, K. D. (2001). Bias, discrimination, and obesity. Obesity Research, 9(12), 788–805.

Puhl, R. M., & Brownell, K. D. (2003). Psychosocial origins of obesity stigma: Toward changing a powerful and pervasive bias. Obesity Reviews, 4(4), 213–227. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1467-789X.2003.00122.x

Puhl, R. M., & Brownell, K. D. (2006). Confronting and coping with weight stigma: An investigation of overweight and obese adults. Obesity, 14(10), 1802–1815.

Puhl, R. M., & Heuer, C. A. (2009). The stigma of obesity: A review and update. Obesity, 17(5), 941–964. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2008.636

Richman, L. S., & Leary, M. R. (2009). Reactions to discrimination, stigmatization, ostracism, and other forms of interpersonal rejection: A multimotive model. Psychological Review, 116(2), 365–383. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015250

Roehling, M. V. (1999). Weight-based discrimination in employment: Psychological and legal aspects. Personnel Psychology, 52(4), 969–1016. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1999.tb00186.x

Roehling, M. V., Roehling, P. V., & Pichler, S. (2007). The relationship between body weight and perceived weight-related employment discrimination: The role of sex and race. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 71(2), 300–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2007.04.008

Rogosa, D. R. (1995). Myths and methods: “myths about longitudinal research” plus supplemental questions. In J. M. Gottman (Ed.), The analysis of change (pp. 3–66). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48, 1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Rudolph, C. W., Wells, C. L., Weller, M. D., & Baltes, B. B. (2009). A meta-analysis of empirical studies of weight-based bias in the workplace. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 74(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2008.09.008

Sabharwal, S., Campoverde Reyes, K. J., & Stanford, F. C. (2020). Need for legal protection against weight discrimination in the United States. Obesity, 28(10), 1784–1785. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22974

Schaufeli, W. B., Taris, T. W., & Van Rhenen, W. (2008). Workaholism, burnout, and work engagement: Three of a kind or three different kinds of employee well-being? Applied Psychology: An International Review, 57, 173–203.

Schmidt, A. M., Jubran, M., Salivar, E. G., & Brochu, P. M. (2023). Couples losing kinship: A systematic review of weight stigma in romantic relationships. Journal of Social Issues, 79(1), 196–231. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12542

Schoemann, A. M., Boulton, A. J., & Short, S. D. (2017). Determining power and sample size for simple and complex mediation models. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 8(4), 379–386. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617715068

Sim, M., Almaraz, S. M., & Hugenberg, K. (2022). Bodies and minds: Heavier weight targets are de-mentalized as lacking in mental agency. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 48(9), 1367–1381.

Spector, P. E., Bauer, J. A., & Fox, S. (2010). Measurement artifacts in the assessment of counterproductive work behavior and organizational citizenship behavior: Do we know what we think we know? Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(4), 781–790. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/a0019477. Accessed May 2023.

Spector, P. E. (1994). Using self-report questionnaires in OB research: A comment on the use of a controversial method. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 15(5), 385–392.

Spector, P. E. (2019). Do not cross me: Optimizing the use of cross-sectional designs. Journal of Business and Psychology, 34(2), 125–137. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.1.2.145

Spector, P. E., Fox, S., Penney, L. M., Bruursema, K., Goh, A., & Kessler, S. (2006). The dimensionality of counterproductivity: Are all counterproductive behaviors created equal? Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68(3), 446–460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2005.10.005

Steele, C. M., Spencer, S. J., & Aronson, J. (2002). Contending with group image: The psychology of stereotype and social identity threat. In Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 34, pp. 379–440). Academic Press.

Strauss, R. S., & Pollack, H. A. (2003). Social marginalization of overweight children. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 157(8), 746–752. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.157.8.746

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relation (pp. 7–24). Hall Publishers.

Täuber, S., Mulder, L. B., & Flint, S. W. (2018). The impact of workplace health promotion programs emphasizing individual responsibility on weight stigma and discrimination. Frontiers in Psychology, 9(2206), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02206

Tomiyama, A. J. (2014). Weight stigma is stressful. A review of evidence for the Cyclic Obesity/Weight-Based Stigma model. Appetite, 82, 8–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2014.06.108

Vanhove, A., & Gordon, R. A. (2014). Weight discrimination in the workplace: A meta-analytic examination of the relationship between weight and work outcomes. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 44, 12–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12193

Vartanian, L. R. (2010). Disgust and perceived control in attitudes toward obese people. International Journal of Obesity, 34(8), 1302–1307. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2010.45

Wang, Y., Beydoun, M. A., Min, J., Xue, H., Kaminsky, L. A., & Cheskin, L. J. (2020). Has the prevalence of overweight, obesity and central obesity levelled off in the United States? Trends, patterns, disparities, and future projections for the obesity epidemic. International Journal of Epidemiology, 49(3), 810–823. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyz273

Waterbury, C. J., Martinez, L. R., Bernard, L., & Smith, N. A. (2024). Becoming and acting as an ally against weight-based discrimination. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 17(1), 142–147. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2023.75

Weiner, B., Perry, R. P., & Magnusson, J. (1988). An attributional analysis of reactions to stigmas. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55(5), 738–748.

Weiss, H. M. (2002). Deconstructing job satisfaction: Separating evaluations, beliefs and affective experiences. Human Resource Management Review, 12(2), 173–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-4822(02)00045-1

Williams, D. R., Yu, Y., Jackson, J. S., & Anderson, N. B. (1997). Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology, 2(3), 335–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910539700200305

Young, J. M., & Widom, C. S. (2014). Long-term effects of child abuse and neglect on emotion processing in adulthood. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(8), 1369–1381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.03.008

Zacher, H., & von Hippel, C. (2022). Weight-based stereotype threat in the workplace: Consequences for employees with overweight or obesity. International Journal of Obesity, 46(4), 767–773. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-021-01052-5

Zielinski, M. J., Veilleux, J. C., Fradley, M. F., & Skinner, K. D. (2023). Perceived emotion invalidation predicts daily affect and stressors. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 36(2), 214–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2022.2033973

Funding

The current research was not supported by any external funding awards.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics

This research was approved and conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the human subjects committee at Auburn University.

Conflicts/Competing Interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest or competing interests in this work.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Johnson, B.N., Hunger, J.M., Sawhney, G. et al. Weight in the Workplace: Weight Discrimination Impacts Professional Outcomes as a Function of Social Pain Minimization. Occup Health Sci (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41542-024-00208-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41542-024-00208-9