Abstract

Empathy plays a crucial role in the workplace, associated with positive outcomes, including helping behavior and task performance. While most studies have treated empathy as a unidimensional and trait-like characteristic, empathy is best understood as a two-dimensional construct, encompassing stable and fluctuating aspects. Considering this conceptualization, our research explores the relationship between the two dimensions – affective and cognitive empathy – with well-being and prosocial behavior, both at the trait and state levels. We hypothesized that affective empathy is positively associated with fatigue, whereas cognitive empathy is positively related to provided support. Furthermore, we predicted that these relationships would be especially pronounced on days when employees witness conflicts in the workplace. Our results, drawn from two diary studies (Ns = 119 and 179), indicated that affective empathy was related to fatigue, and cognitive empathy was related to provided support on the trait level, supporting our hypotheses. However, the distinctions between the two empathy dimensions were less prominent at the state level, and these effects did not depend on observed conflicts. These findings suggest that affective and cognitive empathy have differential effects, emphasizing the need for balanced and beneficial utilization of empathy in both theoretical development and practical workplace contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Empathy is a concept that garners widespread interest, evident among both lay people’s doubled Google searches over the last decade (Google Trends, 2022), and among scholars across various disciplines, with more than 370′000 entries in Google Scholar in the last five years. In the field of work psychology, this interest is particularly pronounced due to empathy’s association with important work outcomes such as performance (Aw et al., 2020) and helping behavior (Batson et al., 2007). Despite this attention, research on empathy often lacks accuracy in its conceptualization and operationalization (Clark et al., 2019). Contemporary perspectives regard empathy as a concept with two components, namely affective empathy, which is experiencing an affective state congruent to others’ affective state, and cognitive empathy, which is understanding the other’s affective state (e.g., Brazil et al., 2023; Clark et al., 2019). Of importance, while most research in work psychology has largely overlooked the multidimensionality nature of empathy, the few studies that made a distinction revealed differential effects for affective and cognitive empathy (e.g.,Brazil et al., 2023; Urbonaviciute & Hepper, 2020).

Furthermore, while empathy can yield positive outcomes, such as fostering altruism (Batson et al., 1988), it may also include downsides that have yet to receive comprehensive exploration. The plausibility of these downsides is underscored by empathy’s inherent high sensitivity to the emotional states of others (Burch et al., 2016). As we delve into below, affective and cognitive empathy may assume different roles in this context. Affective empathy, characterized by feeling the same emotion as the other, may result in exhaustion if individuals around us experience negative emotions. Conversely, cognitive empathy, rooted in the understanding of these emotional states, might act as a buffer against being overwhelmed by the negative emotions of others. Further research is warranted to unravel the difference of affective and cognitive empathy with common work events eliciting emotional responses in others, such as observing a conflict between colleagues and the resulting emotional outcomes. In the present study, we thus extend our investigation beyond the benefits and downsides of affective and cognitive empathy in the workplace. Additionally, we examine how the two components of empathy relate to observing conflicts, which may either have a detrimental impact on well-being by depleting resources or exert a positive influence in providing support to others.

The present research offers four contributions to the existing literature. Firstly, it delves into the distinct effects of affective and cognitive empathy on employee behaviors and well-being, a distinction frequently overlooked in many studies (e.g.,Burch et al., 2016; Decety & Cowell, 2014). Often, studies have mistakenly inferred conclusions about empathy from related concepts such as sympathy (Schroeder et al., 2015), emotional contagion (e.g., Batson et al., 2007), or perspective-taking (Longmire & Harrison, 2018). However, existing evidence from the limited studies that have made this distinction suggests that affective and cognitive empathy yield different effects. For instance, while cognitive empathy has been associated with prosocial behavior, affective empathy has not (Brazil et al., 2023). In contrast, while affective empathy has been linked to distress, cognitive empathy has not (Powell, 2018). These mixed findings emphasize the distinct roles played by the two components of empathy, thereby prompting a reevaluation of the common practice in work psychology to consider empathy as a unidimensional concept. Consequently, the present study helps tackling the issue of differential effects by explicitly discriminating between affective and cognitive empathy, a distinction that is critical to achieve a more precise conceptualization of empathy.

Secondly, this study not only expands our understanding of empathy but also makes a significant contribution by diversifying empathy’s outcomes investigated. Most existing research in the work context has focused on positive behavioral outcomes, such as enhanced task performance (Ployhart & Hakel, 1998) and increased helping behaviors (Batson et al., 2007), as well as its associations with personality (Brazil et al., 2023). In contrast, our study takes a comprehensive approach, exploring the effect of empathy on both behavior and well-being in the workplace. While empathy fosters prosocial behavior, empathy is also resource intensive, as highlighted in the work of Cameron et al. (2019), which implies its potential to exert a detrimental influence on well-being. Consequently, the present study not only investigates the positive impact of empathy through providing support but also delves into its potential negative impact on well-being.

Thirdly, we investigate the interplay between empathy and emotionally charged situations. Guided by the DIAMONDS model (Rauthmann et al., 2014) and the trait activation theory (TAT; Tett & Burnett, 2003), we postulate that empathy is more likely to be activated in empathy-relevant situations. These empathy-relevant situations involve the observable emotional states of others, such as relationship conflicts among coworkers. We therefore seek to unravel how affective and cognitive empathy shapes one’s behavioral reaction (i.e., providing support) and well-being (i.e., fatigue), especially when observing an emotionally laden event such as a conflict at work.

Finally, this study responds to a recent call in the organizational psychology field to investigate empathy on both the trait and the state level (Clark et al., 2019), by further delving into the nuances of empathy-related situations. The TAT (Tett & Burnett, 2003) and DIAMONDS model (Rauthmann et al., 2014) inform our understanding of why empathy may fluctuate depending on empathy-relevant contexts. Traditionally, research predominantly examined empathy as a stable, trait-like characteristic, with numerous studies adopting this perspective (e.g.,Andreychik & Lewis, 2017; Koopman et al., 2021). Nevertheless, evidence suggests that empathy may vary daily and exhibit within-person variations over short timeframes (e.g., Nezlek et al., 2001; Toomey & Rudolph, 2018). Therefore, this study adopts a dual approach, examining both dispositional, stable (i.e., trait) and situational, fluctuating (i.e., state) aspects of empathy. We aim to explore whether the proposed associations of empathy with well-being and support provision exist both for stable interindividual differences in trait empathy (and short-term fluctuations in state empathy. While we do not expect differential effects for trait and state empathy, testing the effects on both levels is critical and can inform theory as the relationship between two constructs at state (within-person) level may differ from the relationship between the analogous constructs at the trait (between-person) level in size or sign (e.g., Dalal et al., 2014; Hamaker, 2012).

Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses Development

In the realm of empathy research, a predominant focus has been on viewing empathy as a stable trait, akin to a personality characteristic. This perspective, reflected in studies (e.g., Koopman et al., 2021; Longmire & Harrison, 2018), has uncovered valuable insights into interindividual differences in empathy and their association with prosocial behaviors. However, this line of inquiry has largely overlooked empathy’s variability within individuals. Diary-based research, as highlighted by Nezlek et al. (2001), has revealed significant daily fluctuations in empathy, emphasizing its dynamic nature and the varying degrees of empathy experienced in different circumstances. Empirical evidence has demonstrated that empathy can exhibit within-person variations not only over several days (Nezlek et al., 2001) but also within the same day (Nezlek et al., 2007; Toomey & Rudolph, 2018). This body of research underscores empathy’s dynamic character, suggesting that it functions as a state responsive to situational cues. Experimental and neuroscience studies have pointed to the role of situational factors in activating state empathy, such as exposure to others’ affective states (Jackson et al., 2005; Rameson et al., 2012).

Responding to this evolving understanding, scholars have emphasized the need for research encompassing both trait and state empathy (e.g., Clark et al., 2019). While previous research has mainly focused on the antecedents of state empathy, such as the exposure to others’ affective states and pain (Jackson et al., 2005), direct interactions with others (Nezlek et al., 2007; Westman et al., 2013), perspective taking (Batson et al., 2002), and one’s own affective experience (Nezlek et al., 2001), studies examining its outcomes are notably lacking. Furthermore, research on state empathy has often failed to distinguish between its affective and cognitive components (for an exception, see Powell & Roberts, 2017). Our study aims to address this gap by testing hypotheses concerning both trait and state empathy. However, we do not make differential assumptions for trait and state empathy and instead propose the same hypotheses for both.

As we explore empathy as both a trait and state, it is crucial to recognize its two key components: affective empathy, which is experiencing an affective state congruent to others’ affective state, and cognitive empathy, which is understanding the other’s affective state (Clark et al., 2019). To illustrate these facets abstractly, one may laugh and feel the joy of a baby laughing without understanding why (affective empathy). Conversely, one might imagine understanding the emotions of a stranger crying at a funeral without personally feeling their sadness (cognitive empathy). Despite their interchangeability in the literature, it is noteworthy that the two facets exhibit only a moderate relationship with each other (r = 0.31) (Reniers et al., 2011) and involve distinct cognitive processes. Specifically, affective empathy is considered to be automatically elicited (Cuff et al., 2016), whereas cognitive empathy relies on controlled processes (Heyes, 2018). In light of these distinctions, we argue that differentiating between these two facets is crucial and that positive outcomes, such as providing social support, are mainly driven by cognitive empathy, while negative outcomes, such as impaired well-being, are mainly driven by affective empathy.

Empathy and Social Support

The Empathy-Altruism hypothesis (Batson et al., 1981) posits that experiencing empathy leads to altruistic behavior and support for others. This hypothesis is supported by research indicating that conditions eliciting high empathic responses to individuals in distress result in helping, even when helping is not easy to do (Fultz et al., 1986). Conversely, conditions evoking low empathic responses lead to helping only when it is difficult to escape, aligning with the hypothesis that empathic emotions drive altruistic motivation and behavior to alleviate another’s distress. In line with this, social support is often defined to encompass empathy (e.g., “emotional social support includes talking, listening, and expressing concern or empathy for a distressed individual.”; Zellars & Perrewé, 2001, p. 459). Previous studies further reinforce this connection by demonstrating that empathy is positively linked with provided social support (e.g., Brazil et al., 2023; Hafenbrack et al., 2020; Longmire & Harrison, 2018; Scott et al., 2010).

However, while previous research mainly treated empathy as a unidimensional construct (for an exception, see Brazil et al., 2023), we suggest that cognitive and affective empathy, despite potentially differing in their impact, both positively influence support behavior. Cognitive empathy, which helps to understand other persons’ emotions, may encourage more supportive behavior by enhancing confidence in effectively addressing others’ emotional needs (Cameron et al., 2019; Schroeder et al., 2015). On the other hand, affective empathy involves a deep emotional understanding that, while it strongly motivates helping behaviors, may sometimes lead to emotional overload, potentially complicating the support process. Nevertheless, neuroscience has shown that affective empathy not only involves mirroring the pain of others but also fosters feelings of concern and a strong motivation to help (de Vignemont & Singer, 2006). Therefore, despite these differences, we hypothesize that both cognitive and affective empathy are positively associated with social support:

-

Hypothesis 1: (a) Cognitive and (b) affective empathy are positively related to given social support.

Empathy and Fatigue

While empathy can yield positive effects on interpersonal behavior, it is not without its associated costs. Individuals are keenly aware of these costs, often perceiving empathy as psychologically taxing and subsequently attempting to circumvent it to protect their well-being (Cameron et al., 2019). As highlighted by Hoffman (1981, p. 133),”empathy […] has the property of transforming another person’s misfortune into one’s own feeling of distress’’. Notably, the act of observing another individual’s pain and experiencing one’s own pain activates the same neuronal areas (Preston & de Waal, 2002), underscoring the potentially detrimental aspects of empathy. Moreover, the process of regulating negative emotions depletes our limited psychological resources pool (e.g., Muraven & Baumeister, 2000), ultimately contributing to emotional exhaustion (Grandey, 2003). Correspondingly, empathic concern was found to drain psychological resources, leaving employees emotionally exhausted (Lin et al., 2022).

We posit that the two types of empathy may exhibit differential associations with fatigue. Affective empathy, involving the absorption of others’ negative emotions, might lead to feelings of being overwhelmed, consequently depleting one’s psychological resources for emotional regulation. Lewis (2010) introduces the concept of "empathic overarousal", suggesting that bystanders may redirect their attention to their own distress, or engage in cognitive strategies to disengage from distressing images of the victim, highlighting a potential mechanism through which affective empathy could contribute to heightened personal distress and, subsequently, impaired well-being. In contrast, cognitive empathy could enable individuals to comprehend the emotions of the other person without necessarily sharing those emotions. Supporting this notion, previous research has revealed that feeling the emotions of others (affective empathy) is related to personal distress, whereas focusing on the understanding of emotional reactions (cognitive empathy) is linked to reduced personal distress (Decety & Cowell, 2014). Therefore, based on our theoretical reasoning and empirical evidence, we postulate the following hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis 2: (a) Cognitive empathy is negatively related to fatigue and (b) affective empathy is positively related to fatigue.

Empathy and Observed Conflicts

Our previous focus has centered on understanding the impact of empathy on behavior and well-being regardless of the context. However, by incorporating insights from the DIAMONDS model (Rauthmann et al., 2014) and aligning with the principles of the Trait Activation Theory (Tett & Burnett, 2003) – both highlighting the interplay between individual characteristics and situational cues – our study delves into the dynamics of how empathy responds to contextual factors, particularly in scenarios highly relevant to empathy, such as workplace conflicts. Serving as a conceptual guide, the DIAMONDS model illustrates how individuals process objective situations concurrently with various person aspects, ultimately giving rise to unique psychological situations. Building upon this conceptual foundation, our study extends the understanding of how empathy reacts to contextual factors. According to the DIAMONDS model, objective situations such as conflicts among coworkers are linked with psychological situations, and how they are understood and interpreted depend on individual facets such as affective or cognitive empathy. This interpretation, in a cascading effect, shapes subsequent behavior, leading to outcomes such as the provision of social support or fatigue. Affective empathy, for instance, may influence individuals to perceive conflicts through the DIAMONDS model’s facet of Negativity lens, anticipating negative emotions. This aligns with affective empathy's aspect of emotional absorption, illustrating how individuals empathetically respond to emotionally charged conflicts, resulting in fatigue. Conversely, cognitive empathy may be linked to the Sociality facet, potentially leading to the provision of support after observing conflicts. Here, the DIAMONDS model’s facet of Adversity becomes pertinent, framing observed conflicts as situations containing problems, conflicts, or criticism. A nuanced exploration of empathy within specific situational contexts, guided by the DIAMONDS model, enhances our understanding of how individual characteristics and contextual factors intertwine, shaping empathetic responses and consequential behaviors.

Shifting our focus from the DIAMONDS model, we turn to the Trait Activation Theory (Tett & Burnett, 2003), which further underscores the influence of contextual factors on the activation and expression of specific personal traits. In line with this theory, we posit that empathy is likely responsive to contextual factors or empathy-relevant situations, especially those involving the observation of relationship conflicts at work. Glomb (2002) showed that over half of unpleasant workplace interactions have witnesses, increasing the likelihood of observing a conflict at work. It is plausible that witnessing a conflict triggers empathy in the observer, given the display of negative emotions by the conflict’s participants, aligning with the premises of Trait Activation Theory. Notably, empathy is characterized by heightened arousal in social situations and increased vigilance to others’ reactions (Nezlek et al., 2001). Consequently, individuals with strong empathic tendencies tend to perceive conflicts more readily (LeBlanc et al., 2012) and are more adept at detecting minor quarrels (Van Lissa et al., 2017).

Our focus on relationship conflicts is grounded in the notion that they tend to have a more severe impact than other types of conflicts such as task conflicts and are most likely to result in observable emotional outcomes (Meier et al., 2013). Relationship conflicts are more personal and are associated with more intense reactions and well-being consequences (De Dreu et al., 2004). Observing a relationship conflict among colleagues often leads to the experience of negative emotions (e.g., Honeycutt et al., 2014; Matthews et al., 2017). Regulating these emotions can deplete one’s psychological resources (Tice et al., 2001), resulting in fatigue. Simultaneously, observing conflicts may also lead to providing support to the individuals involved in the conflict to reassure and comfort them.

Building upon on our previous rationale, the act of observing relationship conflicts in conjunction with affective empathy is expected to result in heightened fatigue and reduced support provision. Contrastingly, cognitive empathy, which involves cognitive reframing and emotional distancing from others’ negative emotions (Decety & Cowell, 2014), is likely to mitigate the negative impact of observing conflicts. Consequently, cognitive empathy is expected to lead to lower fatigue and increased provision of social support in the context of observed conflicts. In line with this reasoning, we postulate the following hypotheses:

-

Hypothesis 3: (a) Observing relationship conflicts is positively related to given social support. (b) This effect is moderated by cognitive empathy; it is stronger among individuals with high (compared to low) cognitive empathy. Moreover, (c) this effect is moderated by affective empathy; it is weaker among individuals with high (compared to low) affective empathy.

-

Hypothesis 4: (a) Observing relationship conflicts is positively related to fatigue. (b) This effect is moderated by cognitive empathy; it is weaker among individuals with high (compared to low) cognitive empathy. Moreover (c), this effect is moderated by affective empathy; it is stronger among individuals with high (compared to low) affective empathy.

The Present Study

The aim of the present study is to address the call within the scientific literature (e.g., Aw et al., 2020; Clark et al., 2019) to comprehensively explore empathy in its multidimensionality on the trait and state level. Affective empathy’s potential to lead to heightened sensitivity to the negative emotions of others, potentially resulting in emotional overwhelm, contrasts with cognitive empathy’s capacity to provide emotional distance to these negative emotions, optimizing positive behavioral reactions and safeguarding well-being. Given these divergent effects, our objective is to examine the differential outcomes of affective and cognitive empathy, particularly in the context of observing workplace relationship conflicts. To achieve this, we present the results of two daily diary studies. Study 1 focused on trait empathy, while Study 2 delved into both trait and state empathy.

Transparency and Openness

Data and code for both studies are available on the Open Science Framework (OSF; https://osf.io/2tb6h/).

Study 1

Method

Participants and Procedure

One hundred and eighty-two Swiss employees working at least 60 percent of full-time employment (equivalent to a minimum 25 h/week) were invited to participate in a diary study about organizational well-being and were recruited with the help of Master’s students. Participants were first sent a link by email to fill in a baseline questionnaire. At the beginning of the following week, they began completing daily surveys for two weeks (weekends excluded, thus 10 days). Each day, participants filled in the survey before leaving work (response window of four hours). As compensation, at the end of the study, participants received individual feedback about their work situation and well-being and took part in the draw of gift cards.

Of the initial sample of 182 participants, 37 persons did not fill in the baseline survey. Additional 26 participants were excluded from the analyses due to providing insufficient data (i.e., completing less than four daily surveys), resulting in a final sample of 119 participants who filled in 926 daily surveys.

The final sample consisted of a majority of women (60%), working on average 40.94 h per week (SD = 8.91), aged from 19 to 61 years old (M = 34.97, SD = 12.38), and mean tenure in their ongoing job of 6.01 years (SD = 7.68). Moreover, 9 percent had completed nine years or less of schooling (i.e., elementary and middle school), 25 percent had completed 12 years of education, 34 percent had a Bachelor’s degree, 25 percent had a Master’s degree, and 7 percent had a doctorate. Thirty-seven percent of participants had a supervisor status.

Measures

All items were presented in French. The original English measures were translated and back-translated by a native English speaker (Brislin, 1970).

Trait Empathy

Affective and cognitive trait empathy were assessed in the baseline survey using the QCAE – Questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy (Reniers et al., 2011). Response format ranged from completely disagree (1) to completely agree (5). Affective empathy consisted of 12 items; an example is: ‘’I am inclined to get nervous when others around me seem to be nervous.’’ Cognitive empathy consisted of 19 items; an example is: ‘’I can tell if someone is masking their true emotion.’’.

Observed Relationship Conflicts

At the end of the workday, observed relationship conflicts at work were assessed with three items from Jehn (1995) that we adapted to the observer’s perspective. Response format ranged from not at all (1) to extremely (5). An example is: ‘’Today, how much did you observe tensions between people at work?’’.

Given Social Support

At the end of the workday, given social support was assessed with four items from Deeter-Schmelz and Ramsey (1997) that we adapted to the protagonist’s perspective. Response format ranged from not at all (1) to extremely (5). An example is: ‘’Today, how much did you show concern towards people at work’s problems?’’.

Fatigue

At the end of the workday, fatigue was assessed with three items from Ciarocco et al.’s scale (2007). Response format ranged from not at all (1) to extremely (5). An example is: “I feel mentally exhausted.’’.

Results and Discussion

Means, standard deviations, intraclass coefficients, and zero-order correlations for the main variables are shown in Table 1. Given that we had nested data (multiple measures per employee), we conducted multilevel random coefficient modeling using the R package lme4 (Bates et al., 2014). The Level 1 variable (observed conflict) was group mean-centered, whereas the Level 2 variables (affective and cognitive empathy) were grand mean-centered. Table 2 presents the results from the multilevel analyses.

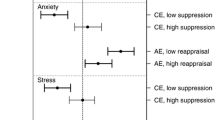

Results indicate partial support for Hypotheses 1 and 2. Only trait cognitive empathy (B = 0.62, p < 0.003) but not affective empathy (B = 0.12, p = 0.454) was positively related to given social support. In the case of hypothesis 2, only trait affective empathy was related to fatigue (B = 0.56, p < 0.001) supporting Hypothesis 2b. However, diverging from Hypothesis 2a, cognitive empathy was unrelated to fatigue (B = 0.05, p = 0.804).

Regarding hypotheses 3 and 4, observed conflicts were positively related to fatigue (B = 0.13, p = 0.005), supporting Hypothesis 4a; however, in contrast to Hypothesis 3a, it was unrelated to given social support (B = 0.09, p = 0.198). Furthermore, neither trait affective nor trait cognitive empathy did moderate the effect of observed conflicts on given social support and fatigue; thus, leading to the rejection of Hypotheses 3b, 3c, 4b, and 4c.

In sum, these results offer some first evidence for differential effects of affective and cognitive empathy on behaviors and well-being. Whereas trait cognitive empathy seems to have beneficial effects, trait affective empathy rather reflects a vulnerability factor for employees.

Study 2

Study 2 was conducted to replicate and extend Study 1. By examining both trait and state empathy, we offer a more fine-grained understanding of the role of affective and cognitive empathy.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The data collection procedure was the same as in Study 1. Among the 244 participants recruited, 192 answered the baseline survey. Thirteen persons completed less than four daily surveys and hence were excluded from the analyses resulting in a total sample of 179 participants who filled in 1,330 daily surveys.

In the final sample, 90 participants were women, 88 were men and one person did not want to answer, age ranged from 19 to 64 years (M = 33.72, SD = 12.28), mean tenure in the current job was of 5.91 years (SD = 7.86) and on average, participants worked 40.11 h per week (SD = 8.86). With respect to educational degree, 42 percent had a high school diploma or below, 30 percent had a bachelor’s degree, 25 percent has a master’s degree and 2 percent had a PhD. Thirty percent had a supervisor status.

Measures

Trait Empathy

As in study 1, affective and cognitive trait empathy were assessed with the scale from Reniers et al. (2011) in the baseline survey.

State Empathy

At the end of the workday, affective and cognitive state empathy was assessed using the Measure of State Empathy (Powell & Roberts, 2017). Affective empathy consisted of three items and response format ranged from not at all (1) to completely (7). An example is: ‘’Today, the feelings of others were transferred to me.’’ Cognitive empathy consisted of three items and response format ranged from not at all (1) to completely (7). An example is: ‘’Today, I understood how individuals I was interacting with were feeling.’’.

Observed Relationship Conflicts

As in study 1, observed relationship conflicts were assessed with the scale from Jehn (1995) at the end of the workday.

Given Social Support

As in study 1, given social support was assessed with the scale Deeter-Schmelz and Ramsey (1997) at the end of the workday.

Emotional Fatigue

At the end of the workday, emotional fatigue was assessed with the three items from Frone and Tidwell (2015). Response format ranged from not at all (1) to extremely (5). An example is: ‘’To which extent do you agree, at the current moment: I feel emotionally exhausted.’’.

Results and Discussion

Means, standard deviations, intraclass coefficients, and zero-order correlations for the main variables are shown in Table 3. Intraclass coefficients indicate that there is a variance between and within individuals for empathy (ICC for affective empathy = 0.489; for cognitive empathy = 0.476), showing that affective and cognitive empathy fluctuates considerably across days. Findings concerning trait empathy obtained in in Study 1 were replicated with trait cognitive empathy positively correlated to given social support and trait affective empathy positively related to fatigue. State empathy showed more nuanced effects.

Table 4 presents the results from the multilevel analyses. Regarding trait empathy, consistent with Hypothesis 1a and divergent from Hypothesis 1b, only trait cognitive empathy (B = 0.64, p < 0.001), but not affective empathy (B = 0.01, p = 0.897) was positively associated with given social support. In the case of Hypothesis 2, only trait affective empathy was positively associated with fatigue (B = 0.66, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 2b. In contrast to Study 1, where cognitive empathy was unrelated to fatigue, Study 2 showed a trend toward our expectations, despite still diverging from Hypothesis 2a (B = -0.31, p = 0.076). Regarding hypotheses 3 and 4, observed conflicts were positively related to fatigue (B = 0.10, p = 0.029), supporting Hypothesis 4a; however, in contrast to Hypothesis 3a, they were unrelated to given social support (B = 0.04, p = 0.342). Furthermore, as in study 1, neither trait affective nor trait cognitive empathy did moderate the effect of observed conflicts on given social support and fatigue; thus, leading to the rejection of Hypotheses 3b, 3c, 4b, and 4c.

Regarding state empathy, consistent with Hypothesis 1a and 1b, both state cognitive empathy (B = 0.13, p < 0.001) and state affective empathy (B = 0.18, p < 0.001) were positively associated with given social support. In the case of Hypothesis 2, only state cognitive empathy was negatively associated with fatigue (B = -0.14 p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 2a. However, diverging from Hypothesis 2b, state affective empathy was unrelated to fatigue (B = 0.03, p = 0.291). As on the trait level, neither state affective nor state cognitive empathy did moderate the effect of observed conflicts on given social support and fatigue; thus, leading to the rejection of Hypotheses 3b, 3c, 4b, and 4c.

The results replicated our findings of study 1, highlighting the different roles of affective and cognitive empathy with fatigue and providing support. Of interest, the analysis on state empathy bespeaks a lesser difference between affective and cognitive empathy. Both are associated with given social support, which underlines the positive impact of both components of state empathy.

General Discussion

This paper investigated the effects of affective and cognitive empathy on given social support and the experience of fatigue at work within the context of observing relationship conflicts in two daily diary studies. Our findings reveal that trait affective empathy is positively associated with fatigue, whereas trait cognitive empathy is positively associated with providing social support. Interestingly, contrary to our assumptions, the effects of empathy were not intensified in an emotionally laden situation, such as observing conflicts among others. The findings from our first study thus suggest that trait affective empathy may primarily play a more negative and emotionally driven role, while trait cognitive empathy may have a more positive and behavioral impact. Addressing the call of scholars (Clark et al., 2019) to explore state empathy, our second study highlights relatively weaker distinctions between affective and cognitive empathy on the state level when compared to the trait level. Notably, in contrast to trait empathy, state empathy appears to have predominantly positive effects. Both affective and cognitive state empathy were positively associated with provided social support, and cognitive state empathy was negatively associated with fatigue. This may suggest that state empathy not only positively contributes to positive behaviors but, in the case of cognitive empathy, may also potentially play a role in promoting to enhanced well-being.

Our study aligns with a limited body of research emphasizing the crucial distinction between affective and cognitive empathy, shedding light on its significance, often overlooked in prior studies (e.g., Burch et al., 2016; Decety & Cowell, 2014). This relevance is affirmed by our replication and support of previous findings (e.g. Brazil et al., 2023; Petrocchi et al., 2021; Powell, 2018) demonstrating that cognitive empathy is positively related to social support provision, while affective empathy correlates with fatigue. Specifically, cognitive empathy seems to enhance the understanding of others’ emotional states, thereby fostering greater social support. This is consistent with a cross-sectional study among adolescents that found a stronger relationship between cognitive empathy and prosocial behavior than affective empathy (Brazil et al., 2023). Conversely, high levels of affective empathy may overwhelm individuals with their own emotions, limiting their ability to support others. Supporting this, research has shown that while cognitive empathy is associated with reduced distress, affective empathy correlates with increased distress, reinforcing the notion that empathically experiencing others’ negative emotions can diminish psychological well-being (Powell, 2018). These results contribute to the ongoing discourse on the distinct roles these empathy components play at work.

Furthermore, our findings not only expand upon the discussion initiated by Clark et al. (2019) regarding the examination of empathy at both trait and state levels but also enhance our comprehension of how empathy-related situations shape employee behavior and well-being. By integrating the DIAMONDS model (Rauthmann et al., 2014) and Trait Activation Theory (Tett & Burnett, 2003), we offer an approach to understanding the fluctuation of empathy in response to contextually relevant situations. Indeed, empirical evidence has supported the variability of empathy in reaction to specific situational triggers (Jackson et al., 2005; Rameson et al., 2012). Our research contributes to this advancing field by delving deeper into the impact of diverse empathy-related situations on employee behavior and well-being. Additionally, our study underscores the importance of examining both stable and situational aspects of empathy by assessing it at both trait and state levels. Through demonstrating the variability of empathy across different days and individuals, we further explored the concept of state empathy. Importantly, our study highlights the predominantly positive effects of state empathy on employee well-being and prosocial behavior.

Expanding the scope of our examination beyond the effects of empathy, our study resonates with emerging research focusing on the impact on workplace bystanders witnessing conflicts or mistreatment, aligning with vicarious mistreatment literature (Dhanani & LaPalme, 2019). Bystanders of conflicts undergo stress responses, manifesting as psychological and physiological strains (Sonnentag & Frese, 2003). In line with this research, observing conflict was related to fatigue in both studies. Bystander intervention research also underscores the role of the social environment (e.g., presence of others) on the likelihood of taking action (Darley & Latané, 1968), such as providing social support. Bystander intervention research emphasizes the role of the social environment, influencing actions such as providing social support, as highlighted by the empathy-altruism hypothesis (Batson et al., 1981), as it explores the egoistic or altruistic motivations underlying the desire to assist someone in need. This underscores that the significance lies more in the type of empathy and the resources needed for emotional regulation, rather than the motivation or social evaluation (Fultz et al., 1986), aligning with the concept that bystanders seek cues from their social environment for intervention (Mayer et al., 2013).

Recognizing the impact of power differences and individual relationships provides a more nuanced perspective on the role of empathy in bystander responses to workplace conflicts. Power dynamics, as evidenced by Hershcovis et al. (2017), play a crucial role in shaping how individuals respond to interpersonal stressors, with those in positions of power more inclined to intervene in instances of incivility. Furthermore, the propensity to empathize with others, influenced by multiple factors and referred to as the empathy bias (Bloom, 2017), is notably contingent on the nature of the relationship. Individuals often exhibit greater empathy and a heightened inclination to provide support to members of their own group (e.g. de Waal & Preston, 2017; Klimecki, 2019). However, in our research, we did not consider the specific individuals involved in conflicts or broader contextual factors like power or relationship dynamics. Nevertheless, these aspects may have played a significant role in shaping the affective and cognitive empathy experienced by our participants, subsequently influencing their well-being and behavioral responses, potentially explaining null-findings for observed conflict and interaction effects. Nevertheless, despite these null findings, the importance of considering the broader context and social environment should be reinforced when addressing workplace bystanders witnessing conflicts.

Theoretical and Practical Implications

The present findings offer practical and theoretical implications. From a practical standpoint, the results provide insights for occupational health professionals. Firstly, the experience of affective empathy in the workplace is related to fatigue, emphasizing the importance of finding ways to mitigate its negative consequences. A promising approach is to enhance positive emotions. Research has shown that positive affect can effectively help individuals cope with the emotional exhaustion that often accompanies empathetic experiences (Lin et al., 2022). One avenue to foster positive emotions is through mindfulness techniques. Engaging in present-focused attention while providing support to others has been demonstrated to predict positive emotions and simultaneously prevent negative emotions (Cameron & Fredrickson, 2015).

Secondly, cognitive empathy is associated with an increased inclination to provide support while preserving well-being. This insight highlights a promising area for interventions aimed at enhancing cognitive empathy. Practitioners can consider strategies such as encouraging perspective-taking and helping individuals put themselves in the shoes of others. For instance, an effective intervention involves training team members to share personal information, actively listen, and discuss differences and similarities in perspectives, as demonstrated by Jungert et al. (2018). These efforts have the potential to promote cognitive empathy, leading to more constructive behavioral responses. It is, however, crucial to design these interventions thoughtfully, ensuring a specific emphasis on enhancing cognitive empathy to harness the benefits of perspective-taking while minimizing potential adverse effects of affective empathy.

From a theoretical standpoint, the implications of our empathy study contribute to a nuanced understanding of empathy in organizational contexts. Firstly, our findings underscore the importance of differentiating between affective and cognitive empathy in measurement tools, given their distinct impacts on employee behavior and well-being. This distinction is crucial for researchers and practitioners aiming to accurately capture the multifaceted nature of empathy, guiding interventions, and strategies tailored to specific empathic components. Moreover, our study prompts further exploration into the realm of state empathy, advocating for a comprehensive investigation into both affective and cognitive empathy in varying situational contexts. Traditional research often focused on trait empathy as a stable characteristic, but our study emphasizes the relevance of examining empathy’s fluctuating aspects, shedding light on how daily variations in empathy is linked to employee well-being and prosocial behavior.

Overall, our theoretical contributions extend beyond the conventional understanding of empathy, paving the way for more refined conceptualizations and measurement approaches in organizational psychology.

Limitations and Future Research

The current study should be understood in light of its limitations. Firstly, we focused only on affective and cognitive empathy but did not consider behavioral empathy, which encompasses the outward expression of affective and cognitive empathy (Clark et al., 2019). We omitted behavioral empathy for two reasons. Firstly, the use of self-report measures in our research posed a challenge, as behavioral empathy is typically assessed with methodologies like behavioral mirroring (Chartrand & Larkin, 2013) and empathic communication (Kerig & Baucom, 2004), making it more suited for studies with other-report (Clark et al., 2019). Secondly, given our focus on social support, the primary emphasis of our study, we prioritized investigating the concept of support provision as a specific behavioral consequence of affective and cognitive empathy rather than delving into the broader domain of behavioral empathy. In future research, it may be valuable to measure behavioral empathy to provide a more comprehensive understanding of empathy, its mechanisms, and its outcomes within workplace contexts.

Secondly, the modest sample size may limit statistical power, particularly for detecting interaction effects. Despite having a relatively large number of participants (compared to other diary studies; Gabriel et al., 2019), Mathieu et al.’s (2012) simulation study suggests that a higher number of daily measures per participant is needed for adequate statistical power in detecting cross-level interaction effects. As such, our null findings for the moderator effects may be a consequence of insufficient statistical power. Additionally, our reliance on self-report measures, especially in assessing state empathy, introduces potential methodological concerns. The unexpectedly high correlation between state affective and cognitive empathy warrants further investigation into the distinctiveness and reliability of these measures.

Finally, while the use of a daily diary study approach helped us to capture the employees’ experiences at work as it is lived (Bolger et al., 2003), including its fluctuations from day to day and with little retrospective bias, the way we measured the observation of conflicts has also some limitations. Given that we did not measure specific conflict episodes, information is missing about duration of the conflict. It is plausible that conflict episodes extend beyond a single day and continued throughout the study period. Our study design does not allow for the examination of the development of conflicts over time. Future studies may, therefore, employ a different design, repeatedly asking about specific conflict episodes and examining how the trajectory is associated with empathy and its impact on the provision of support.

Conclusion

In a world where 90% of people experience an average of at least four emotions daily (Wilhelm et al., 2004), the significance of empathy, characterized by the capacity to both share and understand the emotional states of others, is underscored. Its importance within the realm of social interactions, particularly in the workplace where interpersonal relationships are capital for organizational effectiveness, cannot be overstated. Building upon earlier studies that have raised pertinent concerns in the conceptualization of empathy (e.g., Coll et al., 2017), this research extends beyond theoretical discussions to provide empirical evidence of the differential effects of affective and cognitive empathy, with one being related to increased fatigue while the latter is related to greater provision of social support. These findings emphasize the need for a nuanced approach to the study of empathy, dispelling the notion of empathy as a single, unidimensional construct.

Data Availability

Data and code for both studies are available on the Open Science Framework (OSF; https://osf.io/2tb6h/).

References

Andreychik, M. R., & Lewis, E. (2017). Will you help me to suffer less? How about to feel more joy? Positive and negative empathy are associated with different other-oriented motivations. Personality and Individual Differences, 105, 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.09.038

Aw, S. S. Y., Ilies, R., & De Pater, I. E. (2020). Dispositional empathy, emotional display authenticity, and employee outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(9), 1036–1046. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000471

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2014). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67, 1–48. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.1406.5823

Batson, C. D., Duncan, B. D., Ackerman, P., Buckley, T., & Birch, K. (1981). Is empathic emotion a source of altruistic motivation? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 40(2), 290–302. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.40.2.290

Batson, C. D., Dyck, J. L., Brandt, J. R., Batson, J. G., Powell, A. L., McMaster, M. R., & Griffitt, C. (1988). Five studies testing two new egoistic alternatives to the empathy-altruism hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55(1), 52–77. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.55.1.52

Batson, C. D., Chang, J., Orr, R., & Rowland, J. (2002). Empathy, attitudes, and action: Can feeling for a member of a stigmatized group motivate one to help the group? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(12), 1656–1666. https://doi.org/10.1177/014616702237647

Batson, C. D., Eklund, J. H., Chermok, V. L., Hoyt, J. L., & Ortiz, B. G. (2007). An additional antecedent of empathic concern: Valuing the welfare of the person in need. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(1), 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.1.65

Bloom, P. (2017). Empathy and Its Discontents. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 21(1), 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2016.11.004

Bolger, N., Davis, A., & Rafaeli, E. (2003). Diary methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annual Review of Psychology, 54(1), 579–616. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145030

Brazil, K. J., Volk, A. A., & Dane, A. V. (2023). Is empathy linked to prosocial and antisocial traits and behavior? It depends on the form of empathy. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science / Revue Canadienne Des Sciences Du Comportement, 55(1), 75–80. https://doi.org/10.1037/cbs0000330

Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910457000100301

Burch, G. F., Bennett, A. A., Humphrey, R. H., Batchelor, J. H., & Cairo, A. H. (2016). Unraveling the complexities of empathy research: A multi-level model of empathy in organizations. In N. M. Ashkanasy, C. E. J. Härtel, & W. J. Zerbe (Eds.), Research on Emotion in Organizations (Vol. 12, pp. 169–189). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1746-979120160000012006

Cameron, C. D., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2015). Mindfulness facets predict helping behavior and distinct helping-related emotions. Mindfulness, 6(5), 1211–1218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-014-0383-2

Cameron, C. D., Hutcherson, C. A., Ferguson, A. M., Scheffer, J. A., Hadjiandreou, E., & Inzlicht, M. (2019). Empathy is hard work: People choose to avoid empathy because of its cognitive costs. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 148(6), 962–976. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000595

Chartrand, T. L., & Lakin, J. L. (2013). The antecedents and consequences of human behavioral mimicry. Annual Review of Psychology, 64(1), 285–308. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143754

Ciarocco, N. J., Twenge, J. M., Muraven, M., & Tice, D. M. (2007). The state self-control capacity scale: Reliability, validity, and correlations with physical and psychological stress. Unpublished manuscript, Department of Psychology, Monmouth University, Monmouth, NJ.

Clark, M. A., Robertson, M. M., & Young, S. (2019). “I feel your pain”: A critical review of organizational research on empathy. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(2), 166–192. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2348

Coll, M.-P., Viding, E., Rütgen, M., Silani, G., Lamm, C., Catmur, C., & Bird, G. (2017). Are we really measuring empathy? Proposal for a new measurement framework. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 83, 132–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.10.009

Cuff, B. M. P., Brown, S. J., Taylor, L., & Howat, D. J. (2016). Empathy: A review of the concept. Emotion Review, 8(2), 144–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073914558466

Dalal, R. S., Bhave, D. P., & Fiset, J. (2014). Within-person variability in job performance: A theoretical review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1396–1436. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314532691

Darley, J. M., & Latane, B. (1968). Bystander intervention in emergencies: Diffusion of responsibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 8(4, Pt.1), 377–383. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0025589

De Vignemont, F., & Singer, T. (2006). The empathic brain: How, when and why? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 10(10), 435–441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2006.08.008

De Waal, F. B. M., & Preston, S. D. (2017). Mammalian empathy: Behavioural manifestations and neural basis. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 18(8), 498–509. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn.2017.72

De Dreu, C. K. W., Van Dierendonck, D., & Dijkstra, M. T. M. (2004). Conflict at work and individual well-being. International Journal of Conflict Management, 15(1), 6–26. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb022905

Decety, J., & Cowell, J. M. (2014). Friends or foes: Is empathy necessary for moral behavior? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 9(5), 525–537. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614545130

Deeter-Schmelz, D., & Ramsey, R. P. (1997). Considering sources and types of social support: A psychometric evaluation of the House and Wells (1978) instrument. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 17(1), 49–61.

Dhanani, L. Y., & LaPalme, M. L. (2019). It’s not personal: A review and theoretical integration of research on vicarious workplace mistreatment. Journal of Management, 45(6), 2322–2351. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206318816162

Frone, M. R., & Tidwell, M.-C.O. (2015). The meaning and measurement of work fatigue: Development and evaluation of the Three-Dimensional Work Fatigue Inventory (3D-WFI). Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 20(3), 273–288. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038700

Fultz, J., Batson, C. D., Fortenbach, V. A., McCarthy, P. M., & Varney, L. L. (1986). Social evaluation and the empathy–altruism hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50(4), 761–769. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.50.4.761

Gabriel, A. S., Podsakoff, N. P., Beal, D. J., Scott, B. A., Sonnentag, S., Trougakos, J. P., & Butts, M. M. (2019). Experience sampling methods: A discussion of critical trends and considerations for scholarly advancement. Organizational Research Methods, 22(4), 969–1006. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428118802626

Glomb, T. M. (2002). Workplace anger and aggression: Informing conceptual models with data from specific encounters. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 7(1), 20–36. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.7.1.20

Google Trends. (2022). Search term: Empathy. Retrieved February 14, 2023, from https://trends.google.com

Grandey, A. A. (2003). When “the show must go on”: Surface acting and deep acting as determinants of emotional exhaustion and peer-rated service delivery. Academy of Management Journal, 46(1), 86–96. https://doi.org/10.2307/30040678

Hafenbrack, A. C., Cameron, L. D., Spreitzer, G. M., Zhang, C., Noval, L. J., & Shaffakat, S. (2020). Helping people by being in the present: Mindfulness increases prosocial behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 159, 21–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2019.08.005

Hamaker, E. L. (2012). Why researchers should think “within-person”: A paradigmatic rationale. In M. R. Mehl & T. S. Conner (Eds.), Handbook of methods for studying daily life (pp. 43–61). Guilford Press.

Hershcovis, M. S., Neville, L., Reich, T. C., Christie, A. M., Cortina, L. M., & Shan, J. V. (2017). Witnessing wrongdoing: The effects of observer power on incivility intervention in the workplace. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 142, 45–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2017.07.006

Heyes, C. (2018). Empathy is not in our genes. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 95, 499–507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.11.001

Hoffman, M. L. (1981). Is altruism part of human nature? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 40(1), 121–137. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.40.1.121

Honeycutt, J. M., Keaton, S. A., Hatcher, L. C., & Hample, D. (2014). Effects of rumination and observing marital conflict on observers’ heart rates as they advise and predict the use of conflict tactics. In J. M. Honeycutt, C. R. Sawyer, & S. A. Keaton (Eds.), The influence of communication on physiology and health (pp. 73–92). Peter Lang.

Jackson, P. L., Meltzoff, A. N., & Decety, J. (2005). How do we perceive the pain of others? A window into the neural processes involved in empathy. NeuroImage, 24(3), 771–779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.09.006

Jehn, K. A. (1995). A multimethod examination of the benefits and detriments of intragroup conflict. Administrative Science Quarterly, 40(2), 256–282. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393638

Jungert, T., Van Den Broeck, A., Schreurs, B., & Osterman, U. (2018). How colleagues can support each other’s needs and motivation: An intervention on employee work motivation. Applied Psychology, 67(1), 3–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12110

Kerig, P. K., & Baucom, D. H. (2004). Couple observational coding systems. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates (1st ed.). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410610843

Klimecki, O. M. (2019). The role of empathy and compassion in conflict resolution. Emotion Review, 11(4), 310–325. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073919838609

Koopman, J., Conway, J. M., Dimotakis, N., Tepper, B. J., Lee, Y. E., Rogelberg, S. G., & Lount, R. B. (2021). Does CWB repair negative affective states, or generate them? Examining the moderating role of trait empathy. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(10), 1493–1516. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000837

LeBlanc, D., Gilin, D. A., Calnan, K., & Solarz, B. (2012). Perspective taking, empathy, and relational conflict at work: An investigation among participants in a workplace conflict resolution program. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2086578

Lewis, M. (Ed.). (2010). Handbook of emotions (3. ed., paperback ed). Guilford Press.

Lin, S.-H.J., Poulton, E. C., Tu, M.-H., & Xu, M. (2022). The consequences of empathic concern for the actors themselves: Understanding empathic concern through conservation of resources and work-home resources perspectives. Journal of Applied Psychology, 107(10), 1843–1863. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000984

Longmire, N. H., & Harrison, D. A. (2018). Seeing their side versus feeling their pain: Differential consequences of perspective-taking and empathy at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(8), 894–915. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000307

Mathieu, J. E., Aguinis, H., Culpepper, S. A., & Chen, G. (2012). Understanding and estimating the power to detect cross-level interaction effects in multilevel modeling. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(5), 951–966. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028380

Matthews, G., Zeidner, M., & Roberts, R. D. (2017). Emotional intelligence, health, and stress. In C. L. Cooper & J. C. Quick (Eds.), The Handbook of Stress and Health (pp. 312–326). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118993811.ch18

Meier, L. L., Gross, S., Spector, P. E., & Semmer, N. K. (2013). Relationship and task conflict at work: Interactive short-term effects on angry mood and somatic complaints. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 18(2), 144–156. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032090

Muraven, M., & Baumeister, R. F. (2000). Self-regulation and depletion of limited resources: Does self-control resemble a muscle? Psychological Bulletin, 126(2), 247–259. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.247

Nezlek, J. B., Feist, G. J., Wilson, F. C., & Plesko, R. M. (2001). Day-to-day variability in empathy as a function of daily events and mood. Journal of Research in Personality, 35(4), 401–423. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.2001.2332

Nezlek, J. B., Schütz, A., Lopes, P., & Smith, C. V. (2007). Naturally occurring variability in state empathy. In Farrow, T. F. D. & Woodruff, P. W. R. (Eds.), Empathy in Mental Illness (1st ed., pp. 187–200). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511543753.012

Petrocchi, S., Bernardi, S., Malacrida, R., Traber, R., Gabutti, L., & Grignoli, N. (2021). Affective empathy predicts self-isolation behaviour acceptance during coronavirus risk exposure. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 10153. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-89504-w

Ployhart, R. E., & Hakel, M. D. (1998). The substantive nature of performance variability: Predicting interinvidual differences In intraindividual performance. Personnel Psychology, 51(4), 859–901. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1998.tb00744.x

Powell, P. A. (2018). Individual differences in emotion regulation moderate the associations between empathy and affective distress. Motivation and Emotion, 42(4), 602–613. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-018-9684-4

Powell, P. A., & Roberts, J. (2017). Situational determinants of cognitive, affective, and compassionate empathy in naturalistic digital interactions. Computers in Human Behavior, 68, 137–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.024

Preston, S. D., & de Waal, F. B. M. (2002). Empathy: Its ultimate and proximate bases. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 25(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X02000018

Rameson, L. T., Morelli, S. A., & Lieberman, M. D. (2012). The neural correlates of empathy: Experience, automaticity, and prosocial behavior. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 24(1), 235–245. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn_a_00130

Rauthmann, J. F., Gallardo-Pujol, D., Guillaume, E. M., Todd, E., Nave, C. S., Sherman, R. A., Ziegler, M., Jones, A. B., & Funder, D. C. (2014). The situational eight DIAMONDS: A taxonomy of major dimensions of situation characteristics. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107(4), 677–718. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037250

Reniers, R. L. E. P., Corcoran, R., Drake, R., Shryane, N. M., & Völlm, B. A. (2011). The QCAE: A questionnaire of cognitive and affective Empathy. Journal of Personality Assessment, 93(1), 84–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2010.528484

Schroeder, D. A., Graziano, W. G., Batson, C. D., Lishner, D. A., & Stocks, E. L. (2015). The Empathy–Altruism Hypothesis. In D. A. Schroeder & W. G. Graziano (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Prosocial Behavior. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195399813.013.023

Scott, B. A., Colquitt, J. A., Paddock, E. L., & Judge, T. A. (2010). A daily investigation of the role of manager empathy on employee well-being. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 113(2), 127–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2010.08.001

Sonnentag, S., & Frese, M. (2003). Stress in organizations. Comprehensive Handbook of Psychology, 12, 453–491.

Tett, R. P., & Burnett, D. D. (2003). A personality trait-based interactionist model of job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(3), 500–517. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.3.500

Tice, D. M., Bratslavsky, E., & Baumeister, R. F. (2001). Emotional distress regulation takes precedence over impulse control: If you feel bad, do it! Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(1), 53–67. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.80.1.53

Toomey, E. C., & Rudolph, C. W. (2018). Age-conditional effects in the affective arousal, empathy, and emotional labor linkage: Within-person evidence from an experience sampling study. Work, Aging and Retirement, 4(2), 145–160. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/wax018

Urbonaviciute, G., & Hepper, E. G. (2020). When is narcissism associated with low empathy? A meta-analytic review. Journal of Research in Personality, 89, 104036. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2020.104036

Van Lissa, C. J., Hawk, S. T., Koot, H. M., Branje, S., & Meeus, W. H. J. (2017). The cost of empathy: Parent–adolescent conflict predicts emotion dysregulation for highly empathic youth. Developmental Psychology, 53(9), 1722–1737. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000361

Westman, M., Shadach, E., & Keinan, G. (2013). The crossover of positive and negative emotions: The role of state empathy. International Journal of Stress Management, 20(2), 116–133. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033205

Wilhelm, P., Schoebi, D., & Perrez, M. (2004). Frequency estimates of emotions in everyday life from a diary method’s perspective: A comment on Scherer et al.’s survey-study “Emotions in everyday life.” Social Science Information, 43(4), 647–665. https://doi.org/10.1177/0539018404047712

Yang, L.-Q., Wang, W., Huang, P.-H., & Nguyen, A. (2022). Optimizing measurement reliability in within-person research: Guidelines for research design and R Shiny Web application tools. Journal of Business and Psychology, 37(6), 1141–1156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-022-09803-5

Zellars, K. L., & Perrewé, P. L. (2001). Affective personality and the content of emotional social support: Coping in organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 459–467. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.459

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Neuchâtel. The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Armelle Vallette d’Osia and Laurenz Meier. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Armelle Vallette d’Osia and Laurenz Meier commented, reviewed, and edited previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

At the time of data collection, no procedure for ethical approval for questionnaire studies existed. However, all two studies followed the APA ethics policy regarding the treatment of participants and data was handled in accordance with European guidelines (General Data Protection Regulation, GDRP).

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Competing Interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vallette d’Osia, A., Meier, L.L. Empathy in the Workplace: Disentangling Affective from Cognitive Empathy. Occup Health Sci (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41542-024-00197-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41542-024-00197-9