Abstract

Employees in high-risk occupations like the military are often provided resilience training as a way to improve mental health and performance. This training typically reflects a one-size-fits-all model, even though employees likely differ in their readiness to receive resilience training. Borrowing from the readiness to change literature, the present study examined whether employees could be categorized in terms of their readiness to receive resilience training and whether this categorization was related to perceptions of the utility of resilience training, as well as self-reported resilience and mental health symptoms. Data were collected with an anonymous survey of 1,751 U.S. soldiers in a brigade combat team. Survey items assessed readiness for resilience training, self-reported resilience, mental health symptoms, and perceptions of unit-based resilience training. Following a factor analysis that identified three categories underlying readiness for resilience training (pre-contemplation, contemplation, and action), a finite mixture analysis resulted in the identification of four classes: receptive (71%), resistant (16%), engaged (9%), and disconnected (4%). In a sub-set of the sample (n = 1054) who reported participating in unit-based resilience training, those in the engaged class reported the most positive evaluations of the program. Relative to the other three classes, soldiers in the engaged class also reported the highest level of resilience and fewest mental health symptoms. Thus, those least receptive to resilience training may have been those who needed it most. These results can be used to tailor resilience interventions by matching intervention approach to the individual’s level of readiness to receive the training.

Similar content being viewed by others

Organizations like the military spend copious amounts of resources trying to strengthen the resilience of their workforce (Crane et al., 2022; Dragonetti et al., 2020), and yet most studies demonstrate small to moderate effects, if any, from these interventions (Vanhove et al., 2016). By adapting what is known about individual readiness to change, organizations may be able to shift how they address resilience training and substantially boost the impact such training has on individuals, teams, and the organization as a whole. In this paper, we offer an initial look into how readiness to change theory can be applied to resilience training in an occupational context.

In high-risk occupations like the military, mandated resilience training programs have been disseminated with the expectation that employees who go through the training will be better able to respond to the stressful demands that they encounter (Britt et al., 2016b; Sarkar & Fletcher, 2017; Vanhove et al., 2016). These programs are priorities for high-stakes organizations because when individuals falter under stress, they potentially endanger themselves, their teammates, and their mission. The effectiveness of these resilience training programs is influenced by various factors, including the format of the training (online vs. in-person) and whether the training is delivered in a group or individual setting (Sarkar & Fletcher, 2017).

In the present study, we examine an additional factor that could influence the effectiveness of resilience training programs: whether employees are ready and motivated to receive the training. Being “ready” for resilience training was conceptualized as being prepared for and willing to learn resilience-related concepts and skills. Our goal was to use stages of change theory (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983) to provide insights into understanding individuals’ perceptions of training and characterizing their well-being and overall work and interpersonal functioning. Such insights can contribute to a pragmatic framework for training recommendations and other approaches to improving resilience.

In the remainder of the introduction, we examine how resilience is conceptualized, then describe resilience training efforts, the stages of change model, and how this model may apply to resilience training in high-risk occupations. Through this initial assessment of readiness for resilience training, this study is designed to provide a unique contribution in shaping efforts to improve the resilience of individuals expected to operate under high-stakes conditions.

Conceptualizing Resilience and Resilience Training

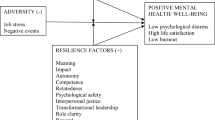

The U.S. Army has defined resilience as “the mental, physical, emotional, and behavioral ability to face and cope with adversity, adapt to change, recover, learn, and grow from setbacks” (Department of the Army, 2014). This definition is consistent with other resilience definitions, including the presence of some kind of adversity and evidence of positive adaptation. For example, Britt et al. (2013) defined resilience as “the demonstration of positive adaptation in the face of significant adversity” (p. 6), and Fisher et al. (2019) defined resilience as “the process by which individuals are able to positively adapt to substantial difficulties, adversity, or hardship” (p. 592).

Resilience matters to high-risk occupations like the military because studies have found that service members exposed to occupation-related stressors are more at risk of reporting mental health difficulties (e.g., Britt et al., 2017; Russell & Russell, 2019) and functional impairment (e.g., Thomas et al., 2011). Interventions like resilience training typically aim to both reduce mental health difficulties and increase individual functioning. In the Army, unit-based resilience training is an annual requirement. As a result, all soldiers are relatively familiar with the construct of resilience and the training materials (Dragonetti et al., 2020), allowing for a common frame of reference. In addition, even though they have experienced resilience training in the past, soldiers also still expect to receive resilience training in the future. The training material is not individualized, but rather delivered in a one-size-fits-all framework (e.g., Adler et al., 2009; Adler et al., 2015a; Vanhove et al., 2016). Given the need to implement training at scale, as well as timing constraints, resource constraints, and the interest in training units together in order to reinforce cohesion through shared experiences, training is typically created to meet the needs of the group as a whole. This method is consistent with resilience training conducted in other high-risk occupational settings (e.g., Crane et al., 2022; Fikretoglu et al., 2019; Vanhove et al., 2016).

The U.S. Army’s training program in resilience (Dragonetti et al., 2020; Orhon, 2020; Reivich et al., 2011) covers topics such as problem solving, challenging thinking traps, regulating emotions, effective communicating, and maintaining connection (Reivich et al., 2011). The skills that are trained in resilience training are consistent with healthy coping skills that have been linked to fewer mental health symptoms in the presence of occupation-related stress (Britt et al., 2016a, 2017; Thomas et al., 2011). Using the framework proposed by Fisher et al. (2019), we consider these training targets to be resilience promoting factors (e.g., cognitive behavioral skills) that should help military personnel enact resilience mechanisms (e.g., effective coping with demands) when they encounter significant adversity in the future.

As a demonstration of the importance with which resilience training is regarded, the military has invested a great deal of resources into various training programs (Dragonetti et al., 2020) and developed doctrine to match (Department of the Army, 2014). To date, resilience training in various settings has been found to have variable effectiveness (Brassington & Lomas, 2021; Chmitorz et al., 2018; Doody et al., 2019; Joyce et al., 2018). For example, some studies have found resilience skills training has had a positive impact on the performance and well-being of service members (e.g., Adler et al., 2015a; Cacioppo et al., 2015; Cohn & Pakenham, 2008; Jha et al., 2020; Williams et al., 2004), whereas other studies have failed to find much positive effect (e.g., Adler et al., 2015b; Cigrang et al., 2000; Fikretoglu et al., 2019; Taylor et al., 2011) or have even found harmful effects under certain circumstances (Fikretoglu et al., 2019). Furthermore, even studies that have shown positive effects report small to modest effect sizes (e.g., Adler et al., 2009; Adler et al., 2015a; Cacioppo et al., 2015; Castro et al., 2012; Mulligan et al., 2012).

Such small effect sizes may be expected given the universal application of the intervention (Bliese et al., 2011), and small effect sizes can be balanced out by the reach of universal programs and the lack of drop-out found in tertiary care (Zatzick et al., 2009). Still, other components of the training experience should be systematically examined in order to adjust approaches designed to support resilience. There could be various reasons why resilience training has resulted in estimates of variable effectiveness, including that the training content is not relevant, the method of delivery is inadequate, or that training itself is not a good solution for improving service member outcomes. While each of these explanations should be considered, one component of training that may be useful to pursue is the degree to which individuals are motivated by or interested in the training topic. Material that is designed as a one-size-fits-all solution may not resonate with individuals if it assumes they are equally open to learning the information.

Stages of Change

As Salas et al. (2012) noted, conducting a job-task and person analysis can lead to training that is more effective. In particular, employee motivation and readiness to learn are both important predictors of training success (Goldstein & Ford, 2002; Salas et al., 2012) and would therefore be expected to be important for the effectiveness of resilience training programs.

Several theoretical models have described the way in which motivation and enacting behavior change operate together (Schwarzer & Luszczynska, 2008). These models include continuum models such as the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991), and stage models such as the Health Action Process Approach (Schwarzer, 2008; Zhang et al., 2019) and the transtheoretical model of change (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983). While each of these models addresses the prediction of particular behaviors, rather than motivation for training in resilience, we based the present study on a stage model because of its link to tailored recommendations for intervention.

To tackle this readiness for change issue, Prochaska theorized that at any given time a person can be at a different “stage of change” and what stage a person is in impacts how well a particular intervention works with that individual (Norcross et al., 2011; Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983). The transtheoretical model of change posits there are five stages of behavioral change: pre-contemplation (no intention to change), contemplation (change is being considered), preparation (individuals commit to change), action (individuals engage in change), and maintenance (individuals consolidate gains and focus on relapse prevention; Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983). Behavior change is regarded as a process that involves moving through a sequence of these stages; interventions that match the individual’s stage of readiness can facilitate the change process by helping the individual transition to the next stage of readiness, rather than, for example, discussing actions to take when the individual is still in the pre-contemplation stage. Thus, intervention success can be predicted by the individual’s stage of change, and when the intervention is tailored to match that stage, the intervention is more effective (Noar et al., 2007).

Much of the work on validating the stages of change concept has focused on addressing health-related behaviors or mental health, such as alcohol problems (e.g., Mitchell & Angelone, 2006), smoking cessation (e.g., DiClemente et al., 1991), and psychotherapy (e.g., Brogan et al., 1999; Norcross et al., 2011). Besides applying the concept to medical conditions, the stages of change paradigm has also been successfully applied to employees in health promotion programs designed to increase physical activity and stress management (Prochaska et al., 2008) and welfare recipients in a work training program (Lam et al., 2010).

The conceptualization of readiness to change can provide a framework for deconstructing the one-size-fits-all approach found in the organizational training literature. That is, different people are “ready” for different types of development, and the “readiness for resilience” construct can be used as a method for matching individuals with interventions. Rather than focus blame on individuals for resilience training being ineffective, this approach may enable organizations to consider different resilience-building efforts tailored to individual differences. Improving such efforts matters in organizations like the military, where getting efforts right has implications for resourcing on a massive scale and for real-world performance.

The Present Study

Using the stages of change model (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983), we examined whether military personnel could be classified based upon their readiness to receive resilience training. We then examined whether these classes would differ on their evaluation of their unit’s resilience training program, as well as their self-reported resilience, mental health symptoms, and overall work and interpersonal functioning. Specifically, we focused on three research goals.

The first goal was to determine whether there were different classes of personnel in terms of their readiness for resilience training. Following the dimensional or clustering approach of Lam et al. (2010) and McConnaughy et al. (1983), research has identified that the stages of change may not be discrete and allows for the identification of different classes based on individuals’ responses to stages of change constructs. Since many of the items used in the present study were adapted from the measure used by Lam et al. (2010), we hypothesized that our classes would match the three classes identified by Lam et al., including indifferent (primarily pre-contemplation), ambivalent (equally moderate on pre-contemplation, contemplation and action) and readiness/action (highest on action). This expectation appeared the most parsimonious given the dearth of alternative categorizations. We also expected our results would be consistent with those of Lam et al. because like Lam et al., our sample was work-related and non-clinical (vs. psychotherapy patients; McConnaughy et al., 1983).

The second research goal was to examine how different classes evaluated resilience training. Taking into account the original concept of readiness to change (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983), it follows that individuals who are not ready for resilience training would be less positively inclined to a one-size-fits-all attempt that assumes they are interested in developing their resilience, and would therefore evaluate the training more negatively. Thus, individuals in classes characterized by less readiness for resilience training were hypothesized to evaluate mandated resilience training more negatively than those who were in classes characterized by more readiness. There are different possible reasons why this relationship might be observed, including doubt that the intervention is needed or that it can be effective, as well as psychological reactance from being required to participate (e.g., Gans & Zhan, 2023; Taylor & Asmundson, 2021; Wiium et al., 2009).

In addition to these two hypotheses, we also had a research question that examined whether individuals categorized into different readiness for resilience training classes would differ on measures of self-reported resilience, mental health, and overall functioning. In terms of the relevance of these outcomes, self-reported resilience is not only the focus of resilience training, but has also been shown to be predictive of how service members manage stress (Britt et al., 2021). In addition, we examined depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and anger. These mental health symptoms were selected because numerous studies with military populations have documented substantial symptom levels across these problem areas (e.g., Adler et al., 2020; Hruby et al., 2021; Levin-Rector et al., 2018), particularly following combat deployment. These symptoms are also associated with diminished work and interpersonal functioning, a metric with relevance for both the larger organizational mission and individual quality of life (e.g., Herrell et al., 2014). Thus, mental health symptoms and the ability for service members to perform their jobs are meaningful markers of resilience for high-risk occupations like the military (Chmitorz et al., 2018).

The categories of readiness for resilience training could be related to these kinds of mental health and overall functioning variables in different ways. On the one hand, people higher in mental health symptoms and lower in self-reported resilience and functioning might be more ready for resilience training because of their need for change compared to those with fewer mental health symptoms. In other words, those higher in mental health symptoms and lower in resilience and functioning may be experiencing dissatisfaction with their lives and may be eager to embrace possible methods of self-improvement. On the other hand, the transtheoretical model of intentional behavior change (DiClemente et al., 2011) suggests mental health symptoms may complicate change efforts due to barriers such as low motivation, poor decision-making, lack of planning, and an array of other difficulties that can distract individuals from engaging in new behaviors. Thus, people who are higher in mental health symptoms and lower in self-reported resilience and functioning might be less ready for resilience training because their symptoms interfere with their attention, energy, and interest in the opportunity provided by resilience training. For example, their symptoms may contribute to their sense of apathy, leaving them too stressed and irritated to focus on resilience training content. If results find that those most in need of resilience training are the least ready, then that would strengthen the argument in favor of tailoring interventions to meet individuals where they are in terms of their level of readiness.

Method

Study Design and Participants

Study participants were U.S. soldiers on active duty in a brigade combat team stationed in Germany that had returned from a combat deployment approximately 1 month earlier. The unit was selected because they were engaged in a concerted effort to provide resilience training activities to units (referred to as “the program” here to preserve unit anonymity), encouraged by the senior leadership, and integrated across various organizations on the Army post. The brigade’s resilience training activities consisted of the Army’s standard resilience training (Orhon, 2020; Reivich et al., 2011) and was supplemented by other resilience training activities (e.g., wellness classes in nutrition and exercise, ropes courses to build confidence). These activities were described as part of the brigade’s resilience training program and were not specific to the post-deployment context nor specific in terms of timing and being on a set schedule. Data were collected during this post-deployment period, reflecting the real-world constraints of coordinating with operational units, yet this period is also associated with soldiers being able to demonstrate (or not demonstrate) their resilience in terms of reporting mental health symptoms following deployment. Training was delivered at the unit level; thus, individual soldiers were not able to self-select in terms of participation.

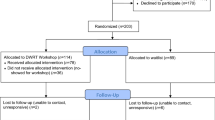

Surveys were anonymous and administered to large groups in a gymnasium. Participants were provided informed consent under a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research. At immediate post-deployment, a total of 2,914 individuals provided their consent, out of 3,475 soldiers who were briefed on the survey (84%). We excluded (a) those who had not deployed to Afghanistan with the Brigade, and (b) those who did not report unit information, as detailed in the Data Analysis section. Using these two filters, 1,751 participants (50.3% of the full sample) were identified for these analyses. Overall, the sample was primarily male (95.6%) and consisted of junior enlisted personnel (50.8%). See Table 1 for a complete description of demographics.

Measures

Background

Demographic variables included gender, rank, marital status, education, and combat deployment experiences. Combat deployment experiences were used as a control variable in the primary analyses and were assessed with a 22-item scale (Adler et al., 2009; Britt et al., 2021).Footnote 1 The measure assessed whether soldiers had ever experienced different types of combat events (e.g., receiving small arms fire, seeing dead bodies or human remains). Participants rated their degree of occurrence with each event using a 4-point scale (Never, One Time, Two to Four Times, Five or More Times). Following prior research (e.g., Britt et al., 2021), items were recoded into whether participants had experienced the combat event or not and then summed.

Readiness for Resilience Training

We began by developing a measure to assess readiness for resilience training using the four-factor University of Rhode Island Change Assessment (URICA) short form (Mander et al., 2012) as a foundation. The original URICA (McConnaughy et al., 1983) has 32 items, 8 items for each of the four stages (pre-contemplation, contemplation, action, and maintenance) and is the most widely used dimensional measure of stages of change. The 16-item URICA short form (URICA-S) was developed to reduce survey burden and redundancy, and potentially increase compliance among study participants scoring high on precontemplation. Although the URICA-S has been validated with a range of medical outcomes (e.g., depression, somatoform and eating disorders), items had to be substantially adapted for an intervention context that was not focused on problems but rather was focused on positive psychology, resilience, and performance enhancement (e.g., Reivich et al., 2011). For example, instead of asking individuals about their problems (e.g., “I have worries but so does the next guy. Why spend time thinking about them?”), we focused on attitudes toward resilience training itself (e.g., “It is not worth time talking about resilience training because everyone has problems.”).

Twelve items that addressed the four dimensions were developed for this study by the first author and another experienced researcher in military psychology. Items and their corollary to the URICA-S, where relevant, are presented in Table 2. These items covered all four stages of change, and the number of URICA-S items was reduced to decrease survey burden further. Specifically, 2 of the 4 pre-contemplation items, 3 of the 4 contemplation items, 3 of the 4 action items, and 1 of the 4 maintenance items from the URICA-S were included. These items were selected based on relevance to resilience training. Three additional items were also included. One of these items was adapted from Lam et al. (2010) and described the training as a “waste of time.” Two items were developed specifically for this study. These items were created to be face valid descriptions of action (“I am interested in increasing my resilience.”) and maintenance (“I am interested in resilience training so I can maintain my resilience.”). Consistent with both the URICA and URICA-S, items reflecting the preparation stage were combined with items reflecting the action stage. Items in the present study were adapted for the context of enhancing resilience rather than decreasing negative behaviors. In all, there were three items in the pre-contemplation stage, four items in the contemplation stage, three items in the action stage, and two items in the maintenance stage. Items were rated on a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree).

Resilience Training Participation and Evaluation

In items developed for this study, participants were asked “Have you taken part in [the unit’s] Resilience Training program (such as: attended training, activities or classes)?” Responses to this item were Yes or No. Those responding yes were then asked about the training’s utility. We note that individuals who responded “no” to this item would still have participated in the Army’s mandatory resilience training prior to joining the unit being surveyed, so we included these individuals in the other analyses for the study. Perception of Training Utility was measured with two items in terms of the past month: “How much are you using the skills you’ve learned in [the unit’s] Resilience Training),” and “How useful is [the unit’s] Resilience Training for you?” Responses were scored using five options (1 = not at all to 5 = a lot). The two items were summed. Cronbach’s alpha for this two-item scale was .93.

Self-Reported Resilience

Perceived resilience was measured using the six-item Brief Resilience Scale measure (Smith et al., 2008). These items (e.g., “I tend to bounce back quickly after hard times,” “I have a hard time making it through stressful events” [reverse coded]), were rated on a five-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The BRS has been evaluated as a useful self-report measure of resilience without including confounding variables that predict resilience (Rodriguez-Rey et al., 2016). This measure has exhibited excellent psychometric characteristics and has been correlated with behavioral health outcomes among military personnel (Britt et al., 2021; Cabrera et al., 2022). Three of the items were worded negatively and were thus reverse-coded, and the six items were summed to create the resilience construct. In this study, the BRS demonstrated good reliability (α = .85).

Mental Health Symptoms and Functional Impairment

Depression symptoms were measured using the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; Spitzer et al., 1999). These items (e.g., “Little interest or pleasure in doing things,” “Feeling tired or having little energy”) were scored in terms of the last two weeks using four response options (0 = not at all to 3 = nearly every day). The PHQ-9 has been used in previous military research (e.g., Adler et al., 2009; Castro et al., 2012; Duma et al., 2010; Hoge et al., 2014; Hruby et al., 2021). Items were summed to create the construct. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was good (α = .87).

Anxiety symptoms were measured using the seven-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7; Spitzer et al., 2006). Items (e.g., “Feeling nervous, anxious or on edge,” “Worrying too much about different things”) were scored in terms of the last two weeks using four response options (0 = not at all to 3 = nearly every day). The GAD-7 has been used in previous military research (e.g., Duma et al., 2010; Hoge et al., 2014; Hruby et al., 2021). Items were summed to create the anxiety construct. The reliability value for this scale was good (α = .91)

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) symptoms were measured using the 17-item PTSD Checklist (PCL; Weathers et al., 1993). Items (e.g., “Repeated, disturbing memories, thoughts, or images of the stressful experience,” “Avoiding thinking about or talking about the stressful experience or avoiding having feelings related to it”) were scored in terms of the past month using five response options (1 = not at all to 5 = extremely). The PCL has been used in previous military research (e.g., Adler et al., 2009; Britt et al., 2021; Castro et al., 2012; Hruby et al., 2021). Items were summed and demonstrated good reliability (α = .95).

Anger and aggression were measured using four items from previous military surveys (e.g., Adler et al., 2017; Cabrera et al., 2016). These anger reaction items, which reflected increasing intensity (e.g., “Get angry at someone and yell or shout at them,” “Get into a fight with someone and hit the person”) were rated on a 5-point scale in terms of frequency in the past month (1 = never to 5 = five or more times). Items were summed, with a Cronbach’s alpha value of .72.

Functional impairment was measured with the 14-item Walter Reed Army Institute of Research Functional Impairment Scale (WRAIR-FIS; Herrell et al., 2014). Items cover the physical, occupational, social, and personal domains (e.g., “Your ability to complete assigned tasks”; “Your ability to get along with your coworkers”) and were rated on a 5-point scale (1 = no difficulty at all to 5 = extreme difficulty). This scale has been used in previous military research (e.g., Hoge et al., 2014). Items were summed and showed good reliability (α = .93).

Data Analysis Plan

Analyses were performed using SAS software (v9.4; SAS Institute Inc, 2016), MPlus (v8.6; Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2017) and the R Statistical Software (v4.1.3; R Core Team, 2022). The broad analytic plan was based on a five-part process: (1) calculation of intraclass correlation coefficients for each item, to assess the degree of non-independence in the data due to individuals’ membership in their assigned platoon groupings; (2) exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with the 12 items used in the survey, using a random half of the sample ; (3) confirmatory analysis (CFA) of factors derived in step (2), using the other randomly-drawn half of the sample; (4) mixture modeling utilizing confirmed factors as continuous indicators of a latent categorical variable, representing differential groupings; (5a) a linear mixed model where latent classes were used to assess individuals’ ratings of a unit-based resilience program; and (5b) linear mixed modeling, where the latent groupings were used to predict self-reported resilience, mental health and overall functioning. In a secondary analysis, combat experiences were also used as an outcome. As combat exposure was a count variable, it was modeled as an overdispersed Poisson process, leveraging the glmmPQL function within the MASS package in R(Venables & Ripley, 2002).

Descriptive statistics, reliability analyses, and composite variable creation were conducted in SAS. The estimation of intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) was conducted using the multilevel package (Bliese, 2022) in the R software. Factor analyses and mixture modeling were carried out in MPlus, using robust estimation and full-information maximum likelihood estimation, and leveraging Hu and Bentler (1999) criteria for the assessment of model fit. Finally, post-hoc analyses were carried out using the nlme package (Pinheiro et al., 2022) in the R software.

Results

Step 1: ICC Analyses

Individuals in Brigade Combat Teams (BCTs) are assigned to platoon-sized groupings. One can expect that responses within these groups will be correlated with each other, based on individuals’ shared experiences and context. The result can be non-independence in response patterns. The degree of non-independence can be assessed by calculating the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient, or ICC1: an index of the amount of variance in responses due to group membership (Bliese, 2000). Where the ICC1 shows a substantive amount of variance due to group membership, then estimates will tend to show a bias stemming from failure to properly model the non-independence in the data.

The analytic sample consisted of 1,751 individuals who provided data on the platoon to which they belonged, and who had deployed with the Brigade Combat Team. For Step 1, we conducted intraclass correlation coefficient analyses of each item, which yielded ICC1 values ranging from .019 to .050. This range of values indicated that approximately 1.9–5% of the variance in item responses could be ascribed to group membership alone. Consequently, this non-independence in the data was incorporated in all subsequent analyses, yielding adjusted standard errors and tests of significance to control for this platoon-level influence.

Steps 2 and 3: Factor Analyses of the Readiness to Change Items

For factor analyses conducted in Steps 2 and 3 below, the sample was divided into random halves (i.e., split-sample approach). One half was used for exploratory analyses (EFA), and the remaining half was used for confirmatory analyses (CFA).

In Step 2, an EFA was used as the extraction method, utilizing the full 12 items from the re-integration survey. The goal was not necessarily to reduce items, but to elucidate the underlying factor structure. Sequential tests modeling up to four latent factors were run in the MPlus software, with oblique (oblimin) rotation, robust estimation, and adjustment for non-independence via the cluster option in MPlus. We retained items if they loaded at least .6 on any factor; this relatively high threshold was selected because it enhanced the identification of robust factors for future work (Gibson et al., 2020).

The initial run, with 12 items, yielded a factor with an eigenvalue of 6.67, and a second factor with an eigenvalue of 1.78.Footnote 2 These were marked for retention (Kaiser, 1960). The third factor had an eigenvalue of .767, and yielded two items that met the threshold and aligned generally to the “contemplation” concept (Table 3). Thus, there were substantive statistical and conceptual grounds on which to retain this third factor for further work, even if the eigenvalue was below 1 (Thompson, 2004). The fourth factor had an eigenvalue of .603, and did not have any items that met the target threshold. Therefore, solutions were limited to three factors in a second EFA run. These results yielded three items that did not meet loading thresholds on any of the three factors, so these items were removed. A final EFA run, limited to the remaining nine items and three factors, resulted in a solution that met model fit and factor loading metrics for subsequent work.

In Step 3, a CFA was conducted to confirm the fit of this nine-item, three-factor solution. The CFA was conducted in MPlus, using robust estimation and adjusting for non-independence. Results yielded a good factor structure (RMSEA = .059; CFI = .972; TLI = .958; SRMR = .034). Using the nomenclature from Mander et al. (2012), the three factors were named: (1) “pre-contemplation”, denoting a resistance to change; (2) “contemplation”, denoting consideration of change without necessarily engaging in change; and (3) “action”, denoting a readiness to change and actions towards change. The overall mean value for Pre-Contemplation was 8.9 (SD = 3.0), with a possible range of 3–15; for Contemplation, the overall mean value was 5.3 (SD = 1.9), with a possible range of 2 to 10; and for Action, it was 12.0 (SD = 4.1), with a possible range of 4 to 20. Cronbach’s alpha values were .84 for pre-contemplation; .78 for contemplation; and .94 for action. Table 3 lists the nine items comprising the solution derived from the EFA procedure, which was verified in the CFA test. Table 4 lists the means, standard deviations and correlations for all primary variables.

Step 4: Latent Mixture Modeling

In Step 4, the full analytic sample (n = 1,751) was used to execute cross-sectional multivariate mixture modeling (Berlin et al., 2014; McLachlan & Peel, 2000) to identify underlying latent classes of respondents. That is, the three factors extracted and confirmed through factor analysis were used as continuous manifest indicators of a latent categorical variable representing classes of cross-sectional respondents. Analysis focused on the derivation of an unconditional model (i.e., without covariates) representing the optimal number of classes (Vermunt, 2010). With each iteration, one additional class was extracted, and model indices were reviewed to assess whether the k + 1 solution (e.g., 3 classes) provided superior fit relative to a k-class solution (e.g., 2 classes). In addition to review of model indices, the size, interpretability, and fundamental characteristics of each additional class were also evaluated. Utilizing this combined approach, analyses proceeded until the attempted extraction of five classes. Here, a very small class (n = 31) showed characteristics indicative of response ambivalence (i.e., high endorsement on what are conceptually conflicting factors). Based on substantive and methodological grounds, the four-class solution was thus selected as the final unconditional model for subsequent analysis. Entropy for the selected solution was 0.90.

The four classes showed differences in response patterns (Fig. 1). Classes were labeled based on how individuals within each class scored relative to the overall mean values on each factor (see Step 3, above). Thus, the largest class (71%; n = 1198) was termed receptive, as individuals aligned to this class scored below the average on pre-contemplation (M = 8.6), but above average on both contemplation (M = 6.2) and action (M = 13.2). The second class (16%; n = 267) was termed resistant, with individuals scoring above average on pre-contemplation (M = 12.9), and below average on both contemplation (M = 2.5) and action (M = 6.4). The third class (9%; n = 152) was named engaged, as these individuals scored below average on both pre-contemplation (M = 6.3) and contemplation (M = 4.1), but above average on action (M = 16.4). The final class (4%; n = 60) was named disconnected, as these individuals scored well below average on all factors: pre-contemplation (M = 4.4), action (M = 5.1), and contemplation (M = 2.5).

Step 5a: Differences between Classes in Evaluations of a Resilience Training Program

In Step 5a, class assignment information derived from latent mixture modeling was exported for subsequent analyses. That is, a four-level variable was extracted which contained the class (e.g., engaged, disconnected) to which that individual was most likely to belong, based on that individual’s responses on the three stages of change factors.

This four-level variable was subsequently used in a sub-set of the sample (n = 1054) who reported participating in the brigade’s resilience training program. Individuals’ perceptions of this unit-based program were set as the outcome variable. Three additional terms were also included in each of these models: (a) combat exposure, as a contextually-relevant index of adversity (e.g., Adler et al., 2009; Hoge et al., 2014; Rivera et al., 2022); (b) rank, as an organization-specific marker for place in the organizational hierarchy and occupational tenure; and (c) a random term to control for non-independence of errors associated with platoon membership.

Those in the engaged class reported significantly more positive perceptions of the resilience program compared to those in the remaining three classes (Table 5). This finding suggests that individuals in the engaged class are the most strongly oriented to the benefits of resilience training, in the abstract (i.e., based on their response patterns on the readiness-for-resilience scale) and in terms of their views of a resilience training program.

Step 5b: Differences between Classes in Resilience and Mental Health

In the final step, a similar set of analyses was conducted using a series of linear mixed models for study outcomes. The continuous outcomes analyzed were: (1) self-reported resilience; (2) depression; (3) PTSD; (4) anxiety; (5) anger reactions; and (6) functional impairment. Each model used the same covariates as in Step 5a (i.e., combat exposure, rank, and platoon-membership). As part of a secondary analysis, combat exposure was also analyzed as an outcome in its own right. Although combat exposure was not considered an outcome from a theoretical standpoint, the analysis enabled us to examine whether combat exposure differed by the four latent classes. For this mixed model, the terms were: (1) the class variable; (2) rank; and (3) a random term to control for non-independence of errors associated with platoon membership.

For all models, the engaged class was selected as the referent group, given its position as the optimal response, and contrasted to the remaining three classes. Also, an alpha adjustment method was used to control for the large number of unique contrasts (24)Footnote 3 executed in these analyses (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995). Contrasts noted as statistically significant were those where the adjusted Benjamini-Hochberg p-value was .05 or lower (Table 5).

Results of these linear mixed models were consistent with the argument that those personnel with the highest perceived resilience and the lowest mental health symptoms and functional impairment, were the most ready for resilience training. Those individuals in the engaged class reported significantly higher mean self-reported resilience scores than did individuals in each of the other three classes. Moreover, those in the engaged class reported significantly lower depression and anger reaction scores than those in the resistant and disconnected classes.

The most consistent finding was significant differences between the engaged and disconnected classes on almost all outcomes studied. Those in the disconnected class reported significantly lower mean self-reported resilience and significantly higher levels of depression, anxiety, and anger reactions than did those in the engaged class. Although there was no significant difference between the disconnected class and the engaged class on functional impairment, the resistant class scored significantly lower than the engaged class on this variable. However, there were no statistically significant differences between the engaged class and the resistant and receptive classes on anxiety, and there were no class differences on PTSD. Finally, analyses of combat exposure as an outcome did not yield any significant class differences (results available from the second author).

Discussion

The present study examined how the new construct of readiness for resilience training was related to perception of resilience training utility and indices of mental health and overall functioning in a large sample of U.S. soldiers. The results of an initial factor analysis with a new scale assessing readiness for resilience training resulted in nine items loading onto three factors that assessed different levels of readiness (pre-contemplation, contemplation, and action). Multivariate mixture modeling identified four distinct classes (receptive, resistant, engaged, and disconnected) based on these three factors. Results regarding these classes suggest that Army training, particularly training following a combat deployment, could be tailored to potentially address these distinct classes with the intent of shifting those individuals who are not engaged into a more open frame of mind, such that the training (or other efforts) can be beneficial to individuals regardless of their readiness stage.

In terms of readiness for resilience training factors, it is interesting to note that we found similar factors identified by Lam et al. (2010), which aligned with the precontemplation, contemplation and action factors reported by Prochaska and DiClemente (1983). In contrast, the classes that were derived from these factors differed slightly from those reported by Lam et al. (2010) and given these patterns, we opted to rename them. Of the four latent classes, two of these classes, receptive and engaged, reflected moderate to high levels of readiness for resilience training, and two of these classes, resistant and disconnected, reflected low levels. These four classes address the first hypothesis regarding the expectation that classes in the present study would be similar to the classes reported by Lam et al. (2010). The hypothesis was partially supported.

Specifically, the resistant class in the present study was similar to the indifferent class reported by Lam et al. (2010) in that both were characterized primarily by endorsement of pre-contemplation items; however, unlike Lam et al., where the scores on contemplation were in the low to mid-range, the resistant class scored well below average on contemplation. Thus, the name “indifferent” seemed like a misnomer since respondents did not appear to be indifferent but rather appeared actually negative (i.e., “resistant”) toward the training. The receptive class also appeared comparable to Lam et al.’s ambivalent class, although Lam et al.’s class was average on the three factors, with pre-contemplation being the highest whereas in the present study contemplation and action were both above average and higher than pre-contemplation. Thus, the term “receptive” seemed more apt than the term “ambivalent”. Finally, our engaged class was comparable to the readiness/action class reported by Lam et al. because both were highest on the action factor, but our engaged class was characterized by being below average on contemplation whereas Lam et al. found their readiness/action class had a moderate score on contemplation. Thus, we opted to emphasize the engaged nature of this class, and also selected the term engaged to avoid using the same name as one of the factors (“action”). Finally, in contrast to Lam et al., we identified a fourth class, characterized as disconnected because respondents were low on all three factors.

Our second hypothesis assessed the degree to which classes characterized by relatively lower levels of readiness for resilience training would report more negative attitudes regarding the utility of their unit’s resilience training than those classes characterized by relatively high levels. Our hypothesis was supported. Specifically, both of the negative classes (i.e., the resistant and disconnected classes) had a significantly less positive perception of resilience training utility than those in the engaged class. The engaged and receptive classes were not statistically different in their attitudes toward the training.

The pattern of findings suggests that the resistant class may have been oriented against resilience training. They may view such training as a waste of time and unnecessary (given their endorsement of pre-contemplation items) and thus take an active stance in opposition to the training. Individuals in this class might be at risk for disrupting the training, potentially undermining the training experience of others (Gans & Zhan, 2023). In comparison, the disconnected class may demonstrate a degree of apathy with regard to resilience training. These individuals appear to be unable to muster the energy to oppose training, and it may be useful to think of them as detached observers.

In terms of the research questions on the relationships between readiness class, self-reported resilience, mental health, and overall functioning, the engaged class responded most positively compared to the other three classes. For example, the engaged class scored higher on self-reported resilience compared to all three other classes. Nevertheless, there were unique patterns for each of the classes compared to the engaged class.

The receptive class did not differ from the engaged class on any of the mental health symptoms but reported more functional impairment than those in the engaged class. In contrast, the resistant and disconnected classes both scored higher on symptoms of depression and anger than the engaged class. Nevertheless, they differed from one another in relation to the engaged class with respect to functional impairment and anxiety. The resistant class reported more functional impairment than the engaged class, but no difference in anxiety symptoms. The reverse was true for the disconnected class, which scored higher on anxiety compared to the engaged class but not significantly different in terms of functional impairment. We note, however, that there were no differences by class in terms of PTSD symptoms. The lack of significant differences could be because PTSD symptoms are largely driven by combat exposure, which was controlled for in the analyses.

Collectively, analyses comparing the engaged and disconnected classes provide a stark contrast between the two classes. Individuals who report a strong orientation toward resilience principles and knowledge report the most adaptive scores on the outcomes examined here. In contrast, individuals in the disconnected class displayed a maladaptive pattern of responses overall in terms of mental health symptoms. However, individuals in the disconnected class did not report more functional impairment, suggesting the possibility that although they were highest in terms of depression, anxiety, and anger symptoms, other (unmeasured) variables may be impacting these relationships. Future research should examine whether these individuals may be using a coping strategy that enables them to maintain their work and interpersonal functioning even in the context of experiencing mental health symptoms.

Considering the results as a whole, it would appear that individuals in the two classes least ready for resilience training (i.e., the disconnected and resistant classes) are the most likely to need some form of support given their lower self-reported resilience and greater levels of depression and anger. Unfortunately, the resilience training may not be addressing their needs, as evidenced by their reporting the training was relatively less useful to them. These findings suggest that training developers may need to be vigilant in crafting material that helps those who are resistant and who do not seem to care about the training itself or organizations may need to consider other, non-training efforts that support their employees.

Interestingly, although this study was conducted after the brigade had returned from a combat deployment, combat exposure was not significantly associated with any particular readiness class. Although it is not clear the degree to which our results would generalize to non-military populations, the fact that degree of combat exposure was not associated with a specific class suggests occupational stress exposure may be independent of attitudes toward training in resilience. This pattern suggests that adapting resilience-oriented efforts to match resilience training readiness levels can be useful as an overarching strategy independent of specific occupationally-relevant stressors.

Limitations

This study is the first to examine the readiness to change model in an occupational context like the U.S. military. Despite the large sample size and unique contribution, there are limitations to consider. First, the data are based on self-report and are not validated by archival records. In addition, this reliance on self-report introduces the risk of common method variance. Second, the readiness for resilience training items do not reflect all possible attitudes toward resilience training but are adapted versions of previous measures. This adaptation required some adjustments to the original items, resulting in some items that were not fully analogous to the original items by Prochaska and DiClemente (1983). Furthermore, at least one of the factors resulted in a two-item solution. These limitations suggest that further systematic scale development with additional items would be useful. Third, details around the training in question were not included in the survey. For example, it is unclear how much time had elapsed between training experiences and survey completion. Fourth, data were cross-sectional and did not address temporal aspects of resilience as recommended by Britt et al. (2016a) and Fisher et al. (2019). Similarly, it was beyond the scope of this study to examine whether the resilience training being assessed was effective. Fifth, the item “I don’t need resilience training” could be potentially interpreted either as a sign of disengagement or mastery. However, given that the item factored with the pre-contemplation items, and this factor had an alpha of .84, we believe the first interpretation is reasonable. Finally, this analysis was focused on soldiers returning from deployment, although the resilience training assessed here was unit-based training and not specific to deployment. Still, other patterns may emerge for soldiers who are in a purely garrison or training environment.

Implications and Future Directions

In terms of practical applications, our findings suggest that broad-based resilience training would have the highest likelihood of success among those in the engaged class, followed by those in the receptive class. This finding is somewhat ironic given that the engaged class would appear to need resilience training least; however, given that resilience training is designed to strengthen individuals and enhance their performance, individuals with few mental health symptoms should still be able to benefit and potentially grow from resilience training. As noted, they rated resilience training high on usefulness. In contrast, individuals in the resistant and disconnected classes may be the least interested and yet have the most to gain from resilience initiatives. Individuals in these last two classes may benefit from alternative modalities, or personalized approaches that address their most pressing concern.

Although it would be tempting to consider the three different readiness to change phases (pre-contemplation, contemplation and action) as if they were discrete stages, and create recommendations for training based on these stages, our analysis (and the analysis of others such as Lam et al., 2010) indicates that for many individuals, the stages overlap with one another. That is, an individual might be high on two of the three factors, low on all three, or high on all three. So instead of being able to simply categorize individuals within a specific readiness to change stage, individuals may be more meaningfully categorized in terms of their overall latent class. By using these four empirically-derived classes, recommendations from the readiness to change literature (Mander et al., 2012; Norcross et al., 2011; Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983) can then be adapted as appropriate. Below, we offer recommendations for how the four classes might be addressed in tailored approaches to resilience training. These recommendations are based directly on the stages of change and motivational interviewing literature (Bundy, 2004; DiClemente et al., 2011; Norcross et al., 2011; Prochaska et al., 1992; Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983).

Individuals aligned to the engaged class, who are highest in the action phase, may have the intent to commit to resilience training or be actively working to adopt new skills. These individuals appear motivated and invested in their own resilience and in the tools provided by resilience training. This class may benefit from goal setting in terms of when to use new skills (Barrett, 2024) and positive reinforcement (Prochaska et al., 1992). Given that the maintenance items were not tested as an independent stage of change, it may also be useful for training to encourage those who are succeeding within the action phase to address the need to sustain their changes, handle setbacks, and employ reminder systems, as recommended in the behavior change literature (Barrett, 2024; Bundy, 2004; Prochaska et al., 1992; Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983).

Individuals in the receptive class appear to possess some measure of skepticism regarding resilience training (as indicated by their pre-contemplation scores), but they seem to be willing to listen to the potential benefits of this training (contemplation) and may be willing to test out concepts (action). For these individuals, the benefits of training should be emphasized, small practical examples provided to demonstrate the utility of the training, and potential barriers to uptake identified (Barrett, 2024; Bundy, 2004; Prochaska et al., 1992; Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983).

Individuals in the resistant class, who score highest on pre-contemplation, do not appear to have an intention to adopt the skills being offered. Thus, it might be helpful for any instructional strategy to avoid confronting resistance (Westa & Aviram, 2013) and instead listen to their concerns and provide information about advantages and disadvantages of resilience training (Frey et al., 2021; Prochaska et al., 1992).

Individuals in the disconnected class represent the most maladaptive class in terms of mental health symptoms. Due to their low endorsement of the three factors (pre-contemplation, contemplation, and action), these individuals may benefit from other types of efforts such as individually-based intervention aimed at reducing disconnection. Future research might consider more closely examining this class, perhaps through mixed methods and an assessment of the degree to which this disconnection impacts other components of their life. Their high scores on our measure of problematic anger are particularly important to note. Given that problematic anger is associated with higher risk for non-response to traditional treatment, greater difficulties in maintaining relationships, and increased risk of harm to self and others (Forbes et al., 2022), this class warrants particular attention. Their level of non-response to traditional resilience training methods may signal a need for psychological screening or other more individualized intervention and skill building.

Despite these recommendations, we realize that the military tends to use one-size-fits-all approaches to training. Thus, addressing differences in training readiness may be best achieved through a combination of strategies, including leveraging individual computer-based training modules, integrating different approaches within each training event to ensure everyone’s perspective is addressed, and preparing leaders to recognize different levels of readiness for resilience training. Although beyond the focus here, it is important to acknowledge that besides training designed for individuals, efforts that target the organization’s structure, policies, processes, and demands may positively impact individual resilience-related outcomes as well. Indeed, individuals in the resistant or disconnected classes might respond better to these efforts than to training in individual skills, particularly if their response to training reflects an overall antipathy toward the organization.

We encourage future research to build on these initial findings by focusing on measurement development to ensure scale items are comprehensive and that additional items are considered so that each factor has a sufficient number of items. Future research may also benefit from examining readiness for resilience training as a predictor of training outcomes. For example, if readiness for resilience training is assessed prior to training, to what degree do individual expectations predict training efficacy? Relatedly, subsequent studies could also assess attitudes held by individuals who have not yet had exposure to resilience training or who received resilience training prior to experiencing a significant stressor such as a combat deployment. It would also be useful to adopt a mixed methods approach to better understand the experience of the different classes.

Moreover, future research should determine whether the readiness-for-change framework would also be usefully applied to the general training readiness context, beyond mandatory training requirements and in other occupational settings where resilience may be less of a high-stakes proposition. Future research should also examine if training elements are successful in moving individuals from one readiness category to another. In addition, follow-on work would benefit from expanding beyond mental health symptoms and difficulties in functioning, and instead examine positive outcomes such as thriving and life satisfaction.

The findings in this study have implications for research and practice. In terms of research, including measures of readiness for resilience training may be useful in understanding the impact of training. We also believe that the latent profiles derived from the stages of change model can, and should, be adopted by training developers as a means for improving the effectiveness of training being implemented across an organization like the military. By being deliberate in understanding the role of individual differences in training readiness, resilience efforts can be improved across organizations, optimizing the resources expended to support these programs.

Notes

In order to investigate whether readiness for resilience training classes were associated with degree of combat exposure, combat experiences were also treated as an outcome variable in a secondary analysis reported in the results.

A scree plot has been included in the Supplementary Materials.

A total of 24 class contrasts were executed for this study. Twenty one of these contrasts were aligned to the seven constructs listed in this section; the remaining 3 contrasts were executed in Step 5a (Differences Between Classes in Evaluations of a Resilience Training Program).

References

Adler, A. B., Bliese, P. B., McGurk, D., Hoge, C. W., & Castro, C. A. (2009). Battlemind debriefing and battlemind training as early interventions with soldiers returning from Iraq: Randomization by platoon. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology,77(5), 928–940. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016877

Adler, A. B., Bliese, P. D., Pickering, M. A., Hammermeister, J., Williams, J., Harada, C., Csoka, L., Holiday, B., & Ohlson, C. (2015a). Mental skills training with basic combat training soldiers: A group randomized trial. Journal of Applied Psychology,100(6), 1752–1764. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000021

Adler, A. B., Williams, J., McGurk, D., Moss, A., & Bliese, P. D. (2015b). Resilience training with soldiers during basic combat training: Randomisation by platoon. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-being,7(1), 85–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12040

Adler, A. B., Brossart, D. F., & Toblin, R. L. (2017). Can anger be helpful? Soldier perceptions of the utility of anger. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease,205(9), 692–698. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000712

Adler, A. B., LeardMann, C. A., Roenfeldt, K. A., Jacobson, I. G., & Forbes, D. (2020). Magnitude of problematic anger and its predictors in the Millennium Cohort. BMC Public Health,20, 1168. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09206-2

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes,50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Barrett, S. (2024). Motivational interviewing: facilitating behaviour change. Don't forget the bubbles. https://dontforgetthebubbles.com/motivational-interviewing-facilitating-behaviour-change/ . Accessed 09 Apr 2024.

Benjamini, Y., & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological), 57(1), 289–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x

Berlin, K., Williams, N., & Parra, G. (2014). An introduction to latent variable mixture modeling (part 1): Overview and cross-sectional latent class and latent profile analyses. Journal of Pediatric Psychology,39(2), 174–187. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jst084

Bliese, P. D. (2000). Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: Implications for data aggregation and analysis. In K. J. Klein & S. W. Kozlowski (Eds.), Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations (pp. 349–381). Jossey-Bass.

Bliese, P. D. (2022). Multilevel: Multilevel functions. R package version 2.7. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=multilevel. Accessed 21 Jan 2024.

Bliese, P. B., Adler, A. B., & Castro, C. A. (2011). Research-based preventive mental health care strategies in the military. In A. B. Adler, P. B. Bliese, & C. A. Castro (Eds.), Deployment psychology: Evidence-based strategies to promote mental health in the military (pp. 103–124). American Psychological Association.

Brassington, K., & Lomas, T. (2021). Can resilience training improve well-being for people in high-risk occupations? A systematic review through a multidimensional lens. The Journal of Positive Psychology,16(5), 573–592. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2020.1752783

Britt, T. W., Sinclair, R. R., & McFadden, A. C. (2013). Introduction: The meaning and importance of military resilience. In R. R. Sinclair & T. W. Britt (Eds.), Building psychological resilience in military personnel: Theory and practice (pp. 3–17). American Psychological Association.

Britt, T. W., Crane, M., Hodson, S. E., & Adler, A. B. (2016a). Effective and ineffective coping strategies in a low autonomy work environment. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology,21(2), 154–168. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039898

Britt, T. W., Shen, W., Sinclair, R. R., Grossman, M., & Klieger, D. (2016b). How much do we really know about employee resilience? Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Perspectives on Science and Practice,9, 378–404. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2015.107

Britt, T. W., Adler, A. B., Sawhney, G., & Bliese, P. D. (2017). Coping strategies as moderators of the association between combat exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. Journal of Traumatic Stress,30(5), 491–501. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22221

Britt, T. W., Adler, A. B., & Fynes, J. (2021). Perceived resilience and social connection as predictors of adjustment following occupational adversity. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology,26(4), 339–349. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000286

Brogan, M. M., Prochaska, J. O., & Prochaska, J. M. (1999). Predicting termination and continuation status in psychotherapy using the transtheoretical model. Psychotherapy: Theory Research Practice Training,36(2), 105–113. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0087773

Bundy, C. (2004). Changing behaviour: using motivational interviewing techniques. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine,97(Suppl), 43–47.

Cabrera, O. A., Adler, A. B., & Bliese, P. D. (2016). Growth mixture modeling of post-combat aggression: Application to soldiers deployed to Iraq. Psychiatry Research,246, 539–544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.10.035

Cabrera, O. A., Trachik, B. J., Ganulin, M. L., Dretsch, M. N., & Adler, A. B. (2022). Factor structure and measurement invariance of the brief resilience scale in deployed and non-deployed soldiers. Occupational Health Science. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41542-022-00138-4

Cacioppo, J. T., Adler, A. B., Lester, P. B., McGurk, D., Thomas, J. L., Chen, H., & Cacioppo, S. (2015). Building social resilience in soldiers: A double dissociative randomized controlled study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,109(1), 90–105. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000022

Castro, C. A., Adler, A. B., McGurk, D., & Bliese, P. D. (2012). Mental health training with soldiers four months after returning from Iraq: Randomization by platoon. Journal of Traumatic Stress,25(4), 376–383. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21721

Chmitorz, A., Kunzler, I., Helmreich, O., Tüscher, R., Kalisch, T., Kubiak, M., Wessa, K., & Lieb, K. (2018). Intervention studies to foster resilience – A systematic review and proposal for a resilience framework in future intervention studies. Clinical Psychology Review,59, 78–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.11.002

Cigrang, J. A., Todd, S. L., & Carbone, E. G. (2000). Stress management training for military trainees returned to duty after a mental health evaluation: Effects on graduation rates. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology,5(1), 48–55. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.5.1.48

Cohn, A., & Pakenham, K. (2008). The efficacy of a cognitive-behavioral program in improving psychological adjustment amongst soldiers in recruit training. Military Medicine,173(12), 1151–1157. https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED.173.12.1151

Crane, M. F., Falon, S. L., Kho, M., Moss, A., & Adler, A. B. (2022). Developing resilience in first responders: Strategies for enhancing psychoeducational service delivery. Psychological Services,19(S2), 17–27. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000439

Department of the Army (2014). Comprehensive soldier and family (AR 350 – 53). https://www.armyresilience.army.mil/ard/images/pdf/Policy/AR%20350-53%20Comprehensive%20Soldier%20and%20Family%20Fitness.pdf. Accessed 09 Apr 2024.

DiClemente, C. C., Prochaska, J. O., Fairhurst, S. K., Velicer, W. F., Velasquez, M. M., & Rossi, J. S. (1991). The process of smoking cessation: An analysis of precontemplation, contemplation, and preparation stages of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology,59(2), 295–304. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.59.2.295

DiClemente, C., Schumann, K., Greene, P., & Earley, M. (2011). A Transtheoretical model perspective on change: Process focused interventions for mental health and substance abuse. In D. Cooper (Ed.), Principles of intervention in mental health-substance use (pp. 69–87). Radcliff.

Doody, C. B., Robertson, L., Uphoff, N., Bogue, J., Egan, J., & Sarma, K. M. (2019). Pre-deployment programmes for building resilience in military and frontline emergency service personnel. Cochrane Database Systematic Review, CD013242. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013242

Dragonetti, J., Gifford, T., & Yang, M. (2020). The process of developing a unit-based army resilience program. Current Psychiatry Reports,22(9), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-020-01169-w

Duma, S. J., Reger, M. A., Canning, S. S., McNeil, J. D., & Gahm, G. A. (2010). Longitudinal mental health screening results among postdeployed U.S. soldiers preparing to deploy again. Journal of Traumatic Stress,23(1), 52–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20484

Fikretoglu, D., Liu, A., Nazarov, A., & Blackler, K. (2019). A group randomized control trial to test the efficacy of the Road to Mental Readiness (R2MR) program among Canadian military recruits. BMC Psychiatry, 19, 326. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2287-0

Fisher, D. M., Ragsdale, J. M., & Fisher, E. C. (2019). The importance of definitional and temporal issues in the study of resilience. Applied Psychology,68(4), 583–620. https://doi.org/10.1111/APPS.12162

Forbes, D., Metcalf, O., Lawrence-Wood, E., & Adler, A. B. (2022). Problematic anger in the military: focusing on the forgotten emotion. Current Psychiatry Reports,24(12), 789–797. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-022-01380-x

Frey, A. J., Lee, J., Small, J. W., Sibley, M., Owens, J. S., Skidmore, B., Johnson, L., Bradshaw, C. P., & Moyers, T. B. (2021). Mechanisms of motivational interviewing: a conceptual framework to guide practice and research. Prevention Science,22, 689–700. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-020-01139-x

Gans, R., and Zhan, M. M. (2023). Let’s Influence That Attitude Before It’s Formed: Inoculation Against Reactance to Promote DEI Training. International Journal of Business Communication, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/23294884231216952

Gibson, T. O., Morrow, J. A., & Rocconi, L. M. (2020). A modernized heuristic approach to robust exploratory factor analysis. The Quantitative Methods for Psychology,16(4), 295–307. https://doi.org/10.20982/tqmp.16.4.p295

Goldstein, I. L., & Ford, J. K. (2002). Training in organizations: Needs assessment, development, and evaluation (4th ed.). Wadworth.

Herrell, R. K., Edens, E. N., Riviere, L. A., Thomas, J. L., Bliese, P. D., & Hoge, C. W. (2014). Assessing functional impairment in a working military population: The walter reed functional impairment scale. Psychological Services,11(3), 254–264. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037347

Hoge, C. W., Riviere, L. A., Wilk, J. E., Herrell, R. K., & Weathers, F. W. (2014). The prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in U.S. combat soldiers: a head-to-head comparison of DSM-5 versus DSM-IV-TR symptom criteria with the PTSD checklist. The Lancet Psychiatry,1(4), 269–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)702

Hruby, A., Lieberman, H. R., & Smith, T. J. (2021). Symptoms of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder and their relationship to health-related behaviors in over 12,000 U.S. military personnel: Bi-directional associations. Journal of Affective Disorders,283, 84–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.01.029

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling,6(4), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.424

Jha, A. P., Zanesco, A. P., Denkova, E., Rooks, J., Morrison, A. B., & Stanley, E. A. (2020). Comparing mindfulness and positivity trainings in high-demand cohorts. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 44(4), 311–326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-020-10076-6

Joyce, S., Shand, F., Tighe, J., Laurent, S. J., Bryant, R. A., & Harvey, S. B. (2018). Road to resilience: a systematic review and meta-analysis of resilience training programmes and interventions. British Medical Journal Open,8(6), e017858. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017858

Kaiser, H. F. (1960). The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educational and Psychological Measurement,20(1), 141–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316446002000116

Lam, C. S., Wiley, A. H., Siu, A., & Emmett, J. (2010). Assessing readiness to work from a stages of change perspective: Implications for return to work. Work (Reading, Mass),37(3), 321–329. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-2010-1085

Levin-Rector, A., Hourani, L. L., Van Dorn, R. A., Bray, R. M., Stander, V. A., Cartwright, J. K., Morgan, J. K., Trudeau, J., & Lattimore, P. K. (2018). Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, and any mental health condition among U.S. soldiers and marines, 2001–2011. Journal of Traumatic Stress,31(4), 568–578. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22316

Mander, J., Wittorf, A., Teufel, M., Schlarb, A., Hautzinger, M., Zipfel, S., & Sammet, I. (2012). Patients With depression, somatoform disorders, and eating disorders on the stages of change: Validation of a short version of the URICA. Psychotherapy,49(4), 519–527. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029563

McConnaughy, E. A., Prochaska, J. O., & Velicer, W. F. (1983). Stages of change in psychotherapy: Measurement and sample profiles. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 20(3), 368–375. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0090198

McLachlan, G., & Peel, D. (2000). Finite mixture models. Wiley.

Mitchell, D., & Angelone, D. J. (2006). Assessing the validity of the stages of change readiness and treatment eagerness scale with treatment-seeking military service members. Military Medicine,171(9), 900–909. https://doi.org/10.7205/milmed.171.9.900

Mulligan, K., Fear, N. T., Jones, N., Alvarez, H., Hull, L., Naumann, U., Wessely, S., & Greenberg, N. (2012). Postdeployment battlemind training for the U.K. armed forces: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology,80(3), 331–341. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027664

Muthen, L. K., & Muthen, B. O. (2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Muthen & Muthen.

Noar, S. M., Benac, C. N., & Harris, M. S. (2007). Does tailoring matter? Meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychological Bulletin,133(4), 673–693. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.673

Norcross, J. C., Krebs, P. M., & Prochaska, J. O. (2011). Stages of change. Journal of Clinical Psychology: In session,67(2), 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20758

Orhon, M. (2020). The leader’s guide to building resilient soldiers. NCO Journal. https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Journals/NCO-Journal/Archives/2020/September/The-Leaders-Guide-to-Building-Resilient-Soldiers/. Accessed 09 Apr 2024.

Pinheiro, J., Bates, D., & the R Core Team. (2022). Nlme: Linear and nonlinear mixed effects models. R package version 3.1–157. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme. Accessed 21 Jan 2024.

Prochaska, J. O., & DiClemente, C. C. (1983). Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology,51(3), 390–395. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.51.3.390

Prochaska, J. O., DiClemente, C. C., & Norcross, J. C. (1992). In search of how people change: applications to addictive behaviors. American Psychologist,47(9), 1102–1114. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.47.9.1102

Prochaska, J. O., Butterworth, S., Redding, C. A., Burden, V., Perrin, N., Leo, M., …, Prochaska, J. M. (2008). Initial efficacy of MI, TTM tailoring, and HRI’s in multiple behaviors for employee health promotion. Preventive Medicine,46(3), 226–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.11.007

R Core Team (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed 21 Jan 2024.

Reivich, K. J., Seligman, M. E. P., & McBride, S. (2011). Master resilience training in the U.S. Army. American Psychologist,66(1), 25–34. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021897

Rivera, A. C., LeardMann, C. A., Rull, R. P., Cooper, A., Warner, S., Faix, D., Deagle, E., Neff, R., Caserta, R., & Adler, A. B. (2022). Combat exposure and behavioral health in U.S. Army Special Forces. PLoS ONE,17(6), e0270515. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270515

Rodriguez-Rey, R., Alonso-Tapia, J., & Hernansaiz-Garrido, H. (2016). Reliability and validity of the brief resilience scale (BRS) Spanish version. Psychological assessment,28(5), e101. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000191

Russell, D. W., & Russell, C. A. (2019). The evolution of mental health outcomes across a combat deployment cycle: A longitudinal study of the Guam Army National Guard. PLoS ONE,14(10), e0223855. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0223855

Salas, E., Tannenbaum, S. I., Kraiger, K., & Smith-Jentsch, K. A. (2012). The science of training and development in organizations: What matters in practice. Psychological Science in the Public Interest,13(2), 74–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100612436661

Sarkar, M., & Fletcher, D. (2017). How resilience training can enhance wellbeing and performance. In M. F. Crane (Ed.), Managing for resilience: A practical guide for employee wellbeing and organizational performance (pp. 227–237). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

SAS Institute Inc. (2016). SAS/BASE® 9.4. SAS Institute Inc.

Schwarzer, R. (2008). Modeling health behavior change: How to predict and modify the adoption and maintenance of health behaviors. Applied Psychology: An International Review,57(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2007.00325.x