Abstract

Financial worries, a distressing emotional state prompted by perceived threats to financial resources, are particularly prevalent among employees during economic downturns. This study investigates associations between financial worries and employees’ health and career behaviors, drawing on conservation of resources theory and the self-regulation literature. We propose that financial worries are not only positively related to health complaints, but also positively related to employees’ career exploration as a coping mechanism. In addition, we explore how financial worries are associated with action crises—internal conflicts about whether to leave one’s job—and how these crises may help explain the relationships between worries and employee outcomes. In a two-month time-lagged study with 312 employees, we observed a positive association between financial worries and health complaints, but no significant association with career exploration. Furthermore, the experience of an action crisis mediated the relation between financial worries and health complaints. Action crises were positively related to subsequent career exploration, and we established a significant indirect effect of financial worries on career exploration through action crises. This research contributes to a better understanding of the potential health-related and behavioral outcomes of financial worries by introducing action crisis as a cognitive–emotional mechanism. It also expands the limited research on antecedents and consequences of action crises and responds to calls for research on the predictors of career exploration as a career self-management behavior. We discuss the study’s implications for theory, research, and practice in light of the its limitations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Financial resources are an important means of acquiring the essentials for survival. Many individuals also desire financial resources for comfort and enjoyment, and these resources are perceived as an indicator of personal accomplishment and a source of satisfaction and positive self-image (Hobfoll et al., 2018; Meuris & Leana, 2018; Sinclair & Cheung, 2016). When individuals become concerned about their financial resource status and when resources are at risk, financial worries arise (Ryu & Fan, 2023; Sinclair & Cheung, 2016). Various polls conducted with employees across Europe, the United States, and elsewhere during the past few years (e.g., Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2022; OECD, 2020; PwC, 2023) have revealed that financial worries are a widespread issue of concern and one of the most extensive sources of stress—mainly for individuals with low income, but also for higher-income employees (De Bruijn & Antonides, 2020).

This study examines financial worries—people’s negative emotional reactions toward their financial situations (Ryu & Fan, 2023; Sinclair & Cheung, 2016)—as a double-edged sword regarding employees’ health and career self-management behaviors. Drawing upon conservation of resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, 1989), we argue that financial worries are negatively related to the physical and mental health of employees (Höge et al., 2015; Klug et al., 2020); however, financial worries may also be positively related to explorative career behaviors, which entail the search for new and potentially better-paid or more secure employment (McFarland et al., 2020) to cope with financial worries and improve one’s situation (Lebel et al., 2023; Staufenbiel & König, 2010).

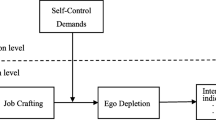

Beyond its associations with health impairments and exploratory career-related behaviors, financial worries may also have the potential to stimulate internal conflicts, doubts, and indecisiveness concerning one’s job—aspects that are integral to the state of an action crisis (Brandstätter et al., 2013). The concept of an action crisis is embedded in the self-regulation literature and described as a decisional conflict in goal pursuit wherein individuals find themselves torn concerning goal engagement (i.e., remaining persistent in pursuing one’s goals and activities) and disengagement (Brandstätter & Schüler, 2013; Herrmann & Brandstätter, 2015). Action crises are multifaceted and include cognitive-emotional aspects, such as perceptions of goal setbacks and unfulfilling goal pursuit, rumination about goals, doubts about behavior and mental conflicts between competing paths of action, prolonged procrastination, indecisiveness, implemental disorientation (i.e., not knowing how to continue), and disengagement impulses (i.e., the tendency to abandon a particular action or activity) (Brandstätter et al., 2013; Kačmár et al., 2023). Action crisis has so far mostly been studied in student samples (e.g., Ghassemi et al., 2017; Herrmann & Brandstätter, 2013; Holding et al., 2021) and received little consideration in the work context (with a few exceptions, e.g., Ivanova & Tornikoski, 2022). We apply this concept to the context of financial worries and their relations with employee health and career-related behaviors. We argue that financial worries tend to elicit intrapsychic decisional conflicts, that is, whether to stay in one’s job or to pursue alternative opportunities given an increasing awareness of the fact that one’s financial security is under threat. Moreover, we investigate the role of action crisis as a potential mechanism that may help explain the relations between financial worries and employee outcomes. Specifically, we assume that financial worries have negative indirect effects on employee health outcomes via action crisis. For the outcome of career exploration, we develop competing hypotheses based on research perspectives arguing that experiencing an action crisis due to financial worries may have the potential to either impair or strengthen one’s efforts to explore alternative career opportunities. Our research model is show in Fig. 1. We tested our model in a 3-wave study using a sample of employees whose employment was adversely impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, increasing the likelihood that financial worries became a significant personal concern.

In this study, we aim to contribute to the literature on financial worries and their links with employee health and career self-management behaviors. By combining COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989; Hobfoll et al., 2018) with perspectives on self-regulation, specifically the concept of action crisis (Brandstätter et al., 2013), we aim to better understand how financial worries may result in health-related and career self-management outcomes. Specifically, by investigating action crises as a potential mechanism, we advance the limited research on the cognitive − emotional pathways that may explain the health-related and behavioral consequences of financial worries (De Bruijn & Antonides, 2020; Ryu & Fan, 2023; Sinclair & Cheung, 2016). At the same time, we enrich the limited literature on the nomological net of action crises (Marion-Jetten et al., 2022), particularly in the context of work, and answer the call for studies on career exploration as career self-management behavior (Jiang et al., 2019).

Financial Worries are Positively Related to Health Complaints

Accumulating financial resources to earn a living is a key manifest function of employment (Jahoda, 1982). Individuals have a strong need to secure valued financial resources (Hobfoll et al., 2018; Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012). When such resources are under threat, negative emotions, such as worries, are provoked (Kelloway et al., 2023; Meuris & Leana, 2018). Worries are broadly conceptualized as a central cognitive component of anxiety (Berenbaum et al., 2007; Borkovec et al., 1998). They denote adverse states characterized by uncontrollable cognitive preoccupation and tension, reflecting negative, future-oriented thoughts. Financial worries arise from one’s subjective assessment of financial constraints or threatened financial security that potentially hinder the achievement of one’s goals and hamper one’s personal development (Meuris & Leana, 2018; Podsakoff et al., 2023). Other terms frequently used in the literature are financial stress (Starrin et al., 2009), financial strain (Kahn & Pearlin, 2006), and financial hardship (Crosier et al., 2007).

According to COR theory, when individuals encounter financial worries resulting from the experienced or expected loss of resources (e.g., a shortage of money due to potentially losing one’s job), their health and well-being suffer (Hobfoll et al., 2018; Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012). Accordingly, empirical studies have revealed that financial worries exert detrimental effects on employees’ mental health outcomes; for instance, they positively predict low quality of life, emotional exhaustion, depression, and sleep difficulties (e.g., Dijkstra-Kersten et al., 2015; Wilson et al., 2020). Furthermore, financial worries are a risk factor for developing physical health issues, such as headaches, gastrointestinal symptoms, and diabetes (Höge et al., 2015). Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis 1: Financial worries are positively related to (a) mental health complaints and (b) physical health complaints.

Financial Worries are Positively Related to Career Exploration

COR theory further states that individuals try to find ways to prevent (financial) resource loss and conserve remaining resources (Hobfoll, 1989; Hobfoll et al., 2018). This focus on the retention and conservation of financial resources in the context of financial worries implies a motivational element by potentially prompting individuals to invest energy and attention in certain actions to cope with and improve the situation (Lebel et al., 2023; Lebert & Voorpostel, 2016). Based on this motivational perspective, we focus on employees’ career exploration as a core approach-oriented career behavior that is potentially initiated by financial worries. In other words, we argue that facing financial worries may provide external motivation to explore one’s environment (Fa-Kaji et al., 2023) and search for other career options with the goal of securing one’s financial resources and mitigating worries.

The literature distinguishes between two central aspects of career exploration: (i) self-exploration, involving self-reflection to gain a comprehensive understanding of one’s vocational desires, values, and abilities, and (ii) environmental exploration, focused on investigating specific career possibilities and gathering information about jobs, industries, and organizations (Blustein, 1997; Kleine et al., 2021). We focus on environmental exploration, which is considered the behavioral dimension of exploration. Career exploration is viewed as a form of career self-management (Hirschi et al., 2018; Sonnentag, 2017) and has mainly been conceptualized and studied through a proactivity lens—as self-initiated and agentic form of career behavior, implying that individuals must exercise agency to pursue career goals (Sonnentag, 2017). It has been considered to be triggered by curiosity and one’s desire to explore, and has often been studied in early career stages, particularly in students (Jiang et al., 2019; Kleine et al., 2021). However, career exploration is also relevant in later career stages and can be motivated by external triggers (Akkermans & Hirschi, 2023). For example, it can be encouraged by contexts in which individuals must adapt to difficult career circumstances arising from life transitions and work- and non-work-related changes (Jiang et al., 2019; Zikic & Klehe, 2006). In the context of coping with changes and crises (e.g., organizational downsizing), career exploration functions as an adaptive mechanism (Savickas, 1997) that is closely linked to employees’ decisions to leave the organization (Zikic & Klehe, 2006; Zikic & Richardson, 2007). Drawing on the research on career exploration as being potentially externally motivated (e.g., employees reacting to external pressure), we conceptualize career exploration as a behavioral response to financial worries (Akkermans & Hirschi, 2023).

-

Hypothesis 2: Financial worries are positively related to career exploration.

The Role of Action Crises

Financial Worries, Action Crises, and Health Complaints

Along with their motivational potential that could enhance approach-oriented behaviors, such as career exploration, we argue that financial worries may have the potential to elicit motivational conflicts between diverging forces toward letting go of, or persisting with, one’s job. We draw on the self-regulatory concept of an action crisis (Brandstätter et al., 2013; Herrmann & Brandstätter, 2015) to explain the phenomenon wherein financial worries make people question their commitment and willingness to continue with their jobs.

Brandstätter et al. (2013) introduced the concept of an action crisis as a state of decisional conflict characterized by feelings of doubt about what to do when contexts or conditions change or when barriers or setbacks threaten people’s progress toward achieving personally valuable goals. An action crisis comprises a conceptually similar state as rumination about one’s goals (Richter et al., 2020). However, action crises are related to future possibilities, while rumination is more strongly oriented toward the past. Moreover, an action crisis is conceptually broader; apart from ruminating about goals, it refers to various cognitive-emotional aspects, such as individuals’ confusion about making decisions and taking action, doubts about goal-related behaviors, mental conflicts about competing paths of action, perceptions of repeated setbacks, implemental disorientation and impulses to disengage from goals, as well as procrastination regarding one’s actions (Brandstätter & Schüler, 2013; Brandstätter et al., 2013; Kačmár et al., 2023).

We apply the concept of an action crisis to the question of whether to remain in one’s current job or to search for other opportunities when experiencing financial worries. Given people’s strong need to secure financial resources (Hobfoll et al., 2018; Jahoda, 1982; Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012), financial worries function as expected barriers to goal pursuit and personal development because they indicate that one’s financial security is under threat, which in turn should prompt decisional and behavioral conflicts in the sense of action crises (Brandstätter & Schüler, 2013; Brandstätter et al., 2013). Links between worries and aspects of an action crisis can be drawn from previous research. Anxiety and worry have been shown to predict risk aversion, procrastination, decision-making difficulties, indecision, and doubt (Arbona et al., 2021; Borkovec et al., 1998; Germeijs et al., 2006; Van Eerde, 2000). For example, research with college students revealed that general worry in students was positively related to procrastination, and that students’ anxiety predicted different facets of career decision-making difficulties (Arbona et al., 2021). Therefore, we derive the following hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis 3: Financial worries are positively related to action crises.

Experiencing action crises due to financial worries is cognitively draining. Individuals feel caught between persistence in, and disengagement from, their jobs and face doubts about decisions and actions (Ivanova & Tornikoski, 2022). Various studies have shown that experiencing such cognitive–emotional conflicts is associated with reduced well-being and compromised mental and physical health (e.g., Herrmann et al., 2019; Holding et al., 2021).

-

Hypothesis 4: Action crises are positively related to (a) mental health complaints and (b) physical health complaints.

In summary, we suggest that people who experience financial worries may be torn between continuously engaging with, or disengaging from, their jobs, and this decisional crisis is associated with mental and physical health issues. Thus, financial worries may be indirectly related to health complaints by activating the cognitive-emotional processes of indecisiveness regarding job pursuit, which are positively related to health complaints. Therefore, we derive the following hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis 5: Financial worries have a positive indirect effect on (a) mental health complaints and (b) physical health complaints through action crises.

Financial Worries, Action Crises, and Career Exploration

Action crises triggered by financial worries may not only have health-related, but also cognitive-behavioral consequences for career self-management behaviors in terms of career exploration. However, we argue that the direction of the relations between action crises and career exploration could either be positive or negative, based on competing perspectives and approaches.

On the one hand, based on research on action crises that highlight their motivational potential (Herrmann & Brandstätter, 2015; Holding et al., 2017), we argue that experiencing an action crisis may have detrimental motivational and behavioral consequences for individuals (Holding et al., 2017). Experiencing a decisional conflict inherent in an action crisis may demand cognitive resources that are then unavailable for problem solving through direct action. This drain on cognitive resources and the subsequent prolonged procrastination, doubts about goal-related behavior, indecisiveness, and implemental disorientation that characterize an action crisis impair employees’ ability to focus on exploring career options. Instead, employees experiencing action crises may show avoidance reactions (Van Eerde, 2000), leading to a state of inactivity. For instance, procrastination, indecisiveness, and rumination as components of action crises have been repeatedly found to result in the postponement of problem solving and delays in goal-oriented behavior, task implementation, and decision making (Ferrari & Dovidio, 2000; Van Eerde, 2000; Watkins & Roberts, 2020). Therefore, we argue that facing an action crisis reduces employees’ likelihood of developing and implementing solutions and actively exploring alternative career opportunities.

-

Hypothesis 6: Action crises are negatively related to career exploration.

Based on COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989), we previously argued that career exploration might help alleviate financial worries, thus stating a positive relationship. However, through the mechanism of an action crisis, this effect may be blocked, suggesting a negative indirect effect of financial worries on career exploration through action crises.

-

Hypothesis 7: Financial worries have a negative indirect effect on career exploration through action crises.

On the other hand, action crises may be positively related to career exploration. An action crisis, which is characterized by questioning one’s current behavior, weighing the pros and cons of continuing with or withdrawing from one’s job, and indecisiveness about the next steps, indicates a need for gathering knowledge and further information for decision making (Brown et al., 2012), which prompts an environmental search for alternative career options.

Furthermore, research on action crises in the self-regulation framework on goal (dis)engagement has suggested that the characteristic decisional conflict of an action crisis often leads individuals to devalue and finally withdraw from their goals (Ghassemi et al., 2017; Herrmann & Brandstätter, 2015). Research has repeatedly supported this positive effect of an action crisis on goal disengagement (Herrmann & Brandstätter, 2013). In the context of the present study, career exploration can be seen as an indicator of the tendency to disengage from one’s current job, thus implying a positive relationship. Therefore, similar to the motivational potential of threatened resource loss (Hobfoll et al., 2018; Lebel et al., 2023), people may cope with an action crisis by disengaging from their jobs since the action crisis constitutes an aversive state that people would want to overcome quickly. Thereby, career exploration functions as a self-protective response to an action crisis, offering a way to improve one’s personal situation (Lebel et al., 2023; Staufenbiel & König, 2010).

Recognizing that financial worries result in doubts, procrastination, and rumination could serve as a strong additional motivator for people who realize that they are or will probably be unable to meet their financial obligations to start exploring alternative career options (Lebel et al., 2023). This would intensify the need for finding a solution and thus enhance the motivating potential of action crises triggered by financial worries. Based on this reasoning, we derive the following hypotheses:

-

Hypothesis 8: Action crises are positively related to career exploration.

-

Hypothesis 9: Financial worries have a positive indirect effect on career exploration through action crises.

Method

Procedure and Participants

We conducted a 3-wave study between the end of May and beginning of August 2021, during the COVID-19 pandemic, to test the hypotheses. The pandemic had a considerable impact on the levels of, and variability in, financial, health, and career-related circumstances and concerns of many employees worldwide (Rudolph et al., 2021) and, therefore, provided an adequate context to study the hypothesized relationships. Economic disruptions forced companies to restructure, downsize, and cut employees’ working hours, place their employees on temporary leave, or even lay off a part of their workforce (Grandey et al., 2021). While countries attempted to buffer the negative financial consequences of the pandemic for the benefit of businesses and their employees, the measures taken could not adequately ease the strain (Bareket-Bojmel et al., 2021; Lee & Sanders, 2013). With the progression of the pandemic, career insecurity and instability continued and, since 2021, a great number of employees, especially in the service industry (Miller & Jhamb, 2022; Serenko, 2022), left their jobs to pursue better alternatives.

A time-lagged design was used to separate the measurement of financial worries at Time (T) 1, action crisis (T2), and health complaints and career exploration (T3) as dependent variables (for a similar design, see Duffy et al., 2021). The study was part of a larger research project. The data has been used in another article that had a different conceptual focus and included different substantive variables (Schmitt & Scheibe, 2023, Study 3). There was no item overlap apart from the demographic variables of age and gender.Footnote 1

We recruited the participants from the website Prolific (Palan & Schitter, 2018) using the prescreening filter option. We invited employees who faced heightened economic challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic (Grandey et al., 2021), because they had experienced a reduction in working hours. Specifically, we recruited employees whose jobs had either been temporarily paused (such as through unpaid leave or furlough) or who had undergone a transition from full-time to part-time employment, or from part-time to working fewer than part-time hours. Moreover, eligible participants had to be native English speakers. In alignment with recommendations from methodologists (Cooper et al., 2020) and following similar studies (Kleine et al., 2023; Weiss et al., 2022), we implemented a four-week time lag between the measurements. We considered this time interval appropriate to minimize memory effects, such as recalling one’s responses to financial worries, which might impact answers to questions related to action crisis and outcomes (Cooper et al., 2020). The participants were compensated with £1.75 for the 13-min-survey at T1 and £1.40 for the 10-min-surveys at T2 and T3. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Department of Psychology at the University of Groningen. Participants were informed about the purpose of the study and the option to withdraw without having to provide a reason and without any negative consequences. Individuals could only participate after providing their informed consent.

At T1, 352 individuals completed the online survey and all passed the four attention check items, which we used as a measure to assure data quality (Newman et al., 2021). After excluding five self-employed participants, 347 were invited for the T2 survey one month later with 306 employees responding. Five participants had to be excluded because they failed one or more attention check items. 301 participants were invited for the T3 survey one month later, and 228 responded. Among these, two participants were excluded due to at least one failed attention check item. In addition, 28 participants were excluded because their job status changed in the study period (i.e., because their working hours increased again, they quit their jobs, or found new jobs), and these changes could have introduced bias in relation to our study focus. In total, 198 participants provided complete data across all three waves.

In our analyses, we applied full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation to accommodate missing variables. FIML uses all available data from participants and is superior to alternative approaches, such as complete case analysis, because it produces unbiased estimates and standard errors given that data are at least missing at random (Enders & Bandalos, 2001). Specifically, the analyses are based on the sample of 312 people who provided valid data at T1 (excluding self-employed workers), who were not removed due to failed attention check items, and whose job status did not change across the study period. However, participants who dropped out at T2 or T3 or had missing scores on single items or scales were not removed (for a similar approach, see e.g., Baillien et al., 2019; Klug et al., 2020; Zacher & Rudolph, 2023).

We did not find differences with regard to key demographic variables (i.e., age, gender, educational degree, job status, employment contract, organizational tenure) and financial worries at T1 between the complete responders (who provided data across all three waves) and the incomplete responders (who provided data at one or two waves only). Mean comparisons ranged between t(307) = -0.235, p = 0.815 to t(310) = -1.135, p = 0.257 for demographic variables and were t(310) = -0.07, p = 0.944 for financial worries. At T1, we also measured individuals’ general health status during the past 4 weeks (answer format ranging from 1 = poor to 5 = excellent). Complete and incomplete responders did not significantly differ in their general health status (t(201.52) = -1.393, p = 0.165).

Of the 312 participants, 66.7% were female and participants’ mean age was 37.38 years (SD = 13.19). The majority of respondents (57.4%) held a university degree. Information on participant gender and educational status were missing for 1% and 13% did not provide information on age. 33.0% were married, and participants had on average 0.68 children under the age of 18 years. Most participants (63.2%) came from the United Kingdom. The others came from other English-speaking countries, such as the USA, Canada, South Africa, and Australia. The participants worked in different industries and sectors (e.g., education, health and welfare, hospitality and tourism, trade, and the construction industry) with 64.4% being white-collar workers (e.g., CEO, project manager, clerical worker) and 35.6% being blue-collar workers (e.g., foreman, manual worker). Participants’ mean organizational tenure was 5.5 years (SD = 5.5), and most (67.9%) had a permanent employment contract.

Measures

All survey items were presented in English and they referred to participants’ experiences in the respective past four weeks.

Financial Worries (T1)

We measured financial worries with four items using the scale by Meuris and Leana (2018). An example item is “I was worried about my financial situation.” Response options ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.88.

Action Crisis (T2)

We adapted the six-item action crisis scale (ACRISS; Brandstätter & Schüler, 2013; Holding et al., 2017) to capture action crisis throughout the past four weeks with regards to participants’ jobs (for a similar approach, see Brandstätter et al., 2013; Kačmár et al., 2023). The items covered different aspects that constitute action crises: rumination (“I repeatedly ruminated about my job”), disengagement impulse (“I have thought about quitting my job”), setbacks (“Pursuing my job went without any problems,” reversed coded), conflict (“I doubted whether I should continue my job or quit”), implemental disorientation (“When pursuing my job, I was repeatedly confronted with situations where I did not know how to continue”), and procrastination (“I repeatedly did not engage in my job despite the intention to do so”). The participants completed the items on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.84.

Mental and Physical Health Complaints (T3)

Health complaints in the last four weeks were assessed using the measure by Bono et al. (2013). We asked about participants’ mental health complaints using three items (e.g., “I felt tired or fatigued”) and physical health complaints using four items (e.g., “Neck or back pain,” “Headache”). The items were completed on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (severely). Cronbach’s alphas were 0.78 for both mental and physical health complaints.

Career Exploration (T3)

Career exploration was measured with the three items from the Career Resources Questionnaire (Hirschi et al., 2018). An example item is “I regularly collected information about career opportunities.” The participants completed the items on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.93.

Control Variables (T1)

Participants’ age (in years), gender (1 = female, 2 = male), and job contract (0 = temporary, 1 = permanent) were statistically controlled in the analyses (Richter et al., 2020). Evidence suggests that women report lower mental health (e.g., higher emotional exhaustion) and physical health (Brewer & Shapard, 2004; Carmel & Bernstein, 2003; Kleine et al., 2023). Men facing economic constraints were found to more likely experience voluntary turnover (Lebert & Voorpostel, 2016), and should show higher career exploration than women. Older employees are on average less likely to voluntarily change their employers (Weisberg & Kirschenbaum, 1991), and are thus less likely to explore other job opportunities (Richardson & Zikic, 2007). We also expected that employees with a temporary contract, who usually experience more uncertainty, should show higher career exploration (Richardson & Zikic, 2007).

Statistical Analysis

We applied structural equation modeling (SEM) in Mplus 8.9 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017) to test the hypotheses. We first tested the measurement model to assess distinctiveness of the latent factors by conducting a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). We compared the expected five-factor model with a four-factor model that combines physical and mental health complaints, a three-factor model that combines the constructs that were assessed at each respective time point, and a one-factor model. Next, we conducted SEM using the bias-corrected bootstrapping method (MacKinnon et al., 2004; Preacher & Hayes, 2008) based on 10,000 bootstrap draws and maximum likelihood estimation.

We assessed the model fit, with a comparative fit index (CFI) of ≥ 0.90 indicating acceptable fit and ≥ 0.95 denoting excellent fit. For the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), scores of ≤ 0.07, and for the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), scores of ≤ 0.08, are considered indicative of good model fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1993; Hu & Bentler, 1999). FIML was utilized as the principal method within Mplus for SEM to address issues of missing data. Notably, FIML applies to the dependent variables only, not to covariates. Since some of our control variables (age and gender) had missing data, we estimated the variances of these variables by naming and incorporating them into the model command in Mplus. This allowed Mplus to consider them as dependent variables, thereby enabling the application of FIML to these variables as well (e.g., Klug et al., 2020).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

As shown in Table 1, the hypothesized five-factor model fitted the data better than alternative models with fewer factors. The model had an acceptable fit with the data: χ2 = 351.846, df = 160, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.926; RMSEA = 0.062, SRMR = 0.059. Modification indices indicated that the model fit would improve slightly (χ2 = 304.644, df = 159, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.943; RMSEA = 0.054, SRMR = 0.053) if the error terms of two action crisis items were to be correlated. However, we decided not to adjust the model following this data-driven approach because there was no clear theoretical rationale for specifying correlated errors, and it was unclear if such an adjustment would represent some peculiar characteristics of our data, thus likely resulting in overfitting (MacCallum et al., 1992).Footnote 2 The standardized factor loadings across scale items ranged from 0.49 to 0.94.

Bivariate correlations of the variables are reported in Table 2. Older participants reported lower financial worries at T1 and lower health complaints at T3. Women reported significantly more health complaints at T3. Both financial worries at T1 and action crisis at T2 were positively related to all three outcome variables at T3.

Hypothesis Tests

We tested the direct and indirect relationships proposed in Hypotheses 1 to 9 by estimating all paths simultaneously. The fit of the model was acceptable (χ2 = 418.969, df = 205, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.918; RMSEA = 0.058, SRMR = 0.056). Figure 2 depicts the unstandardized path coefficients and the 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals (two-tailed). Effects are considered significant if the confidence interval excludes zero.

Structural equation model. Note. N = 312. Unstandardized coefficients are shown. The measurement model and the demographic control variables are not presented to improve clarity. 95% CI = 95% Bootstrap confidence interval based on 10,000 samples. R2 = Proportion of variance explained in the respective variable. *p ≤ .05. **p ≤ .01. Apart from the main effect of financial worries at T1 on career exploration at T3, all paths (direct and indirect effects) are significant

Supporting Hypothesis 1, financial worries at T1 positively predicted mental (B = 0.31, SE = 0.07, 95% CI = [0.17, 0.46]) and physical (B = 0.17, SE = 0.05, 95% CI = [0.10, 0.28]) health complaints at T3. In contrast, financial worries at T1 did not significantly predict career exploration at T3 (B = 0.14, SE = 0.09, 95% CI = [− 0.03, 0.40]). Thus, Hypothesis 2 could not be supported. Financial worries at T1 positively predicted action crises at T2 (B = 0.26, SE = 0.07, 95% CI = [0.13, 0.40]), supporting Hypothesis 3. Action crises positively predicted mental and physical health complaints (B = 0.32, SE = 0.06, 95% CI = [0.20; 0.31] and B = 0.18, SE = 0.05, 95% CI = [0.10; 0.29]), supporting Hypothesis 4. The indirect effect of financial worries at T1 on health complaints at T3 through action crisis was positive and significant for employees’ mental (B = 0.08, SE = 0.03, 95% CI = [0.02, 0.15]) and physical health complaints (B = 0.05, SE = 0.02, 95% CI = [0.02, 0.10]). Hypothesis 5 was supported.

Regarding career exploration, we proposed competing hypotheses based on literature suggesting either negative or positive relations with action crises. We found a positive main effect of action crises at T2 on career exploration at T3 (B = 0.21, SE = 0.08, 95% CI = [0.06, 0.38]; see Fig. 2). This supports Hypothesis 8 but not the competing Hypothesis 6. The indirect effect of financial worries at T1 on career exploration at T3 through action crises at T2 was positive and the 95% CI did not include zero (B = 0.06, SE = 0.03, 95% CI = [0.02, 0.13]), which supports Hypothesis 9 but not the competing Hypothesis 7. This suggests that financial worries are positively related to action crises, which in turn are positively related to career exploration.Footnote 3 Overall, however, only 9.3% of the variance in career exploration could be explained by the model variables, whereas the variables explained substantial proportions of 45.0% and 34.4% of the variances in mental and physical health complaints, respectively.

Discussion

Financial worry is an aversive emotional state that becomes salient to many individuals during economic downturns, as was the case during the COVID-19 pandemic (Bareket-Bojmel et al., 2021; Fa-Kaji et al., 2023). Beyond the pandemic, financial worries will likely remain relevant in the future due to economic recession, consumer price inflation, and rising costs of living. Building on COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989) and the self-regulation literature, our study aimed to uncover the role of financial worries as a double-edged sword for employees’ health complaints and career exploration.

We attempted to replicate well-established positive relations between financial worries and mental and physical health complaints, while arguing that financial worries could also relate positively to individuals’ thoughts and behaviors regarding the exploration of alternative career options (Lebel et al., 2023; Staufenbiel & König, 2010). Another objective of our study was to explore whether an action crisis (Brandstätter et al., 2013)—defined as experiencing internal decisional conflicts about whether to persist in or leave one’s current job—constitutes a mechanism that helps transmit the positive effects of financial worries on health complaints and either mitigates or enhances the positive effect of financial worries on career exploration.

We found evidence for positive relations between financial worries and both mental and physical health complaints. Additionally, these relations were mediated by action crises. Although financial worries were not significantly related to career exploration, action crises had a positive association with career exploration, and financial worries had a positive indirect effect on career exploration through action crises.

Theoretical and Practical Implications

Our study contributes to the literature by providing evidence for the role of financial worries as a double-edged sword regarding employees’ health complaints and career exploration. Linking COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989) with the self-regulation literature (Lebel et al., 2023; Lebert & Voorpostel, 2016; Staufenbiel & König, 2010), particularly the notion of action crisis (Brandstätter & Schüler, 2013), facilitates the understanding of the effects of financial worries on health and career-related outcomes. Specifically, our study extends COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989) by suggesting that the positive associations between financial worries on health complaints may be explained by action crises. Our findings further advance the literature on the adverse consequences of anxiety (and worries, in particular) for decision-making, doubts and procrastination (e.g., Arbona et al., 2021; Borkovec et al., 1998; Van Eerde, 2000), and literature on the well-being and health-reducing effects of action crises (e.g., Holding et al., 2021) by applying these concepts to the work context.

The finding that financial worries have a positive indirect effect on career exploration via action crisis has implications for studies on career exploration and self-regulation in dealing with financial worries. First, drawing on the career self-management literature (Hirschi et al., 2018; Jiang et al., 2019), we argue that career exploration is a desirable, albeit possibly externally motivated (Akkermans & Hirschi, 2023) response to financial worries, with potentially positive long-term consequences for the employee (e.g., finding a new and better job). As career construction theory (Savickas, 1997) notes, challenging experiences, such as financial problems and stress, can activate individuals’ psychosocial career resources (i.e., career adaptability), which may result in career exploration. However, our study could not underpin this argument since there was no direct effect of financial worries on career exploration. Instead, our results suggest that it is the action crisis rather than financial worries that prompts employees’ exploration of alternative career options in their environments. The positive link between action crises and career exploration supports previous literature stating that action crises frequently result in goal withdrawal (Ghassemi et al., 2017; Herrmann & Brandstätter, 2015), and in the context of our study, career exploration can be seen as an indicator of disengagement from one’s job. Disengaging by exploring other career options may be a functional cognitive-behavioral response and coping strategy to help find solutions, overcome an action crisis, and thereby prevent further financial resource loss inherent in financial worries, which determine the action crisis (Hobfoll et al., 2018; Lebel et al., 2023; Lebert & Voorpostel, 2016). The results thus suggest that an action crisis may serve as a motivator that drives employees to act by searching for information and exploring alternative career options.

We also presented an alternative reasoning in favor of negative rather than positive effects of financial worries—through action crisis—on career exploration. Specifically, an action crisis could be expected to demand the use of cognitive resources that consequently become unavailable for problem solving, such as action directed at exploring alternative career options. Instead, it might result in avoidance behavior, inactivity, and delay in decision-making (Ferrari & Dovidio, 2000; Van Eerde, 2000). However, this perspective was not supported. Notably, one limitation of our study design is our focus on the one-month time-lagged effects without exploring the concurrent effects of an action crisis on career exploration. Despite its benefits for preventing artificially inflated relations between the study variables (Cooper et al., 2020), this design does not allow us to distinguish between the immediate and (medium-term) lagged effects of an action crisis. Consequently, we may have missed out on the negative short-term or concurrent effects of an action crisis on career exploration. In other words, experiencing indecisiveness, doubts, and inner conflicts could initially hinder or delay career exploratory action, likely resulting in avoidance behavior (Ferrari & Dovidio, 2000). However, after a one-month period, employees might have managed to overcome this state, and the action crisis could enfold its motivational potential and activate exploratory behavior (Lebel et al., 2023; Lebert & Voorpostel, 2016). This indicates that the effects of action crises on career exploration are more complex and that the element of time plays an important role, such that effects may vary, depending on the time point of measurement. This underscores the importance of considering both short-term and long-term relations in future research.

Regarding practical implications, it is crucial for employees and organizations to learn that both financial worries and action crises are negatively related to employees’ health complaints over the periods of one and two months, respectively. Additionally, whereas action crises were positively related to career exploration one month later, these relations are rather small. The findings indicate that organizations and other stakeholders, such as unions, should take financial worries seriously, given their negative health-related consequences. Physical and mental health complaints can have adverse effects on employees and organizations, such as absenteeism and early retirement (Kelloway et al., 2023; van den Berg et al., 2010). From an organizational perspective, career exploration might be perceived as a negative outcome if it leads to increased employee turnover and the subsequent need to hire new staff. Thus, organizational leaders should discuss financial well-being with their employees and measure it in employee surveys. Organizations could also consider implementing targeted interventions that combine psychological and financial advice and consultation, connect employees with financial professionals, and establish employee assistance funds to help employees deal with unexpected economic difficulties (Odle-Dusseau et al., 2018; Ryu & Fan, 2023; Zikic & Richardson, 2007).

Limitations and Implications for Future Research

This study has several limitations that should be addressed in future research. First, we conducted a 3-wave longitudinal study, which allowed us to temporally separate the predictor, mediator, and outcome variables. However, we did not implement a fully time-lagged design with repeated assessments of all variables. Our results are thus based on correlational data, subject to key drawbacks. For example, we cannot prove that experiencing an action crisis is the crucial mechanism that produces the effect of financial worries on the outcome variables. Reversed causal effects could have been alternative explanations. For instance, health complaints might intensify action crises and result in more worries (Arbona et al., 2021). Therefore, caution is advised when drawing conclusions about causal claims in our study. Implementing a fully time-lagged design with repeated assessments of all variables would not only have allowed us to study both concurrent and lagged effects, as mentioned above, but would also have enabled us to separate variability at the between-person level from variability at the within-person level, and thus, to consider the potential dynamics within individuals and the episodic character of the variables (Hamaker et al., 2015). Moreover, our study design did not allow us to examine how long the action crises lasted. Some preliminary evidence suggests that the state of an action crisis may last for several weeks or months (Holding et al., 2021; Ivanova & Tornikoski, 2022). Assessing the duration of an action crisis is key to determining its consequences since it is shown that the longer the period spent by individuals in a state of action crisis, the worse the consequences are for their well-being, and potentially, for career exploration (Ivanova & Tornikoski, 2022).

Second, based on our data and referring to previous findings (e.g., Kačmár et al., 2023), we see some potential in the improvement of the ACRISS measure for the assessment of action crisis. Exploring the modification indices of our CFA revealed that the error terms of two action crisis items correlated. Unfortunately, the vast majority of studies using the ACRISS did not report and validate its factor structure (Herrmann et al., 2019; Holding et al., 2017). The factorial validity and psychometric properties of the ACRISS should be considered, and future studies should systematically report the theory-derived measurement model to determine and possibly fix potential weaknesses of the scale.

Third, given that this study investigated the experiences of employees during the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic, with most employees residing in the United Kingdom, future research should test the model in other historical and geographical contexts and use different time lags to strengthen the generalizability of the results (Odle-Dusseau et al., 2018). Fourth, we argued that in the context of financial worries, career exploration is likely to function as a cognitive-behavioral concept that is externally caused and controlled rather than autonomously motivated (Akkermans & Hirschi, 2023). However, we did not measure the sources of motivation to explore alternative career options (e.g., self-determined or feeling forced to explore career options) in our study.

Finally, future research could expand on our study and model to examine the relations among financial worries, action crises, and individual outcomes from a more detailed and holistic perspective. Our results could have been driven by third variables that were not addressed in our model. For example, financial worries, action crises, and health complaints might be determined by personal characteristics, such as trait anxiety, (low) self-confidence, and neuroticism (e.g., Brandstätter et al., 2013). Similarly, we did not consider moderators or boundary conditions that could have either facilitated or debilitated the effects of financial worries and action crises on the outcome variables. Relationship might be contingent on individual and contextual factors (Höge et al., 2015; Ryu & Fan, 2023), such as personality traits (Fa-Kaji et al., 2023; Jiang et al., 2019), and emotional and instrumental social support from family, friends, or career counselors (Jiang et al., 2019; Kleine et al., 2021). For instance, trait resiliency (i.e., people’s tendency to overcome adversity) has been found to increase the effect of worrying about financial insecurity on employees’ proactivity (Fa-Kaji et al., 2023). Future research could also investigate other relevant work-related outcomes in the context of financial worries and action crises. When people feel worried about their financial resources, various behavioral reactions are possible next to career exploration. For example, employees could also decide to improve their personal situations by discussing internal possibilities or negotiating work conditions with their current employers, or resort to engaging in unethical or counterproductive behaviors (Lebel et al., 2023; Lebert & Voorpostel, 2016; Staufenbiel & König, 2010). An action crisis might be an important determinant of these behaviors as well.

Conclusion

This study revealed that financial worries are positively associated with mental and physical health complaints, but not directly associated with employees’ active exploration of alternative career opportunities. Financial worries were also positively related to the experience of action crises, which in turn were positively associated with mental and physical health complaints. Interestingly, individuals who experienced stronger action crises due to financial worries were also more likely to engage in career exploration. Overall, the study highlights financial worries and action crises as double-edged swords regarding health and career-related outcomes, but the negative effects were somewhat stronger.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Notes

The other study (Schmitt & Scheibe, 2023, Study 3) used career engagement and career learning measured at T3 as dependent variables. According to the career self-management literature (Hirschi et al., 2014, 2018; Jiang et al., 2019), career exploration, learning, and career engagement are conceptually different variables. We conducted confirmatory factor analyses to confirm the conceptual structure and distinction of the three constructs. The hypothesized three-factorial model provided the best fit with the data (χ2 = 229.541, df = 87, p < .001; CFI = .939; RMSEA = .091, SRMR = .060). It fitted the data better than a two-factor model with career exploration and engagement as one factor and career learning as a second factor (χ2 = 534.018, df = 89, p < .001; CFI = .809; RMSEA = .159, SRMR = .081), a two-factor model with career exploration and learning as one factor and career engagement as a separate factor (χ2 = 536.566, df = 89, p < .001; CFI = .808; RMSEA = .159, SRMR = .113), and a single- factor model (χ2 = 743.482, df = 90, p < .001; CFI = .720; RMSEA = .191, SRMR = .094). All items loaded significantly on their respective factors (standardized factor loadings ranged between .57 and .93). A correlation analysis showed that career exploration at T3 correlated positively and significantly with career engagement at T3 (r = .63, p < .001) and with career learning at T3 (r = .49, p < .001). Overall, the results reveal that the three variables represent related but distinct concepts.

We reran the analyses and tested the hypotheses based on correlated error terms for the two action crisis items. The results, as described in the following paragraph, did not change as a result of this.

The results from the hypotheses tests did not change with the control variables age, gender, and employment contract being removed from the analyses. Moreover, we repeated the analyses using listwise deletion (i.e., based on N = 198, who completed all three study waves). The pattern of results was similar to the findings gathered based on the FIML analyses.

References

Akkermans, J., & Hirschi, A. (2023). Career proactivity: Conceptual and theoretical reflections. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 72(1), 199–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12444

Arbona, C., Fan, W., Phang, A., Olvera, N., & Dios, M. (2021). Intolerance of uncertainty, anxiety, and career indecision: A mediation model. Journal of Career Assessment, 29(4), 699–716. https://doi.org/10.1177/10690727211002564

Baillien, E., Griep, Y., Vander Elst, T., & De Witte, H. (2019). The relationship between organisational change and being a perpetrator of workplace bullying: A three-wave longitudinal study. Work & Stress, 33(3), 211–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2018.1496161

Bareket-Bojmel, L., Shahar, G., & Margalit, M. (2021). COVID-19-related economic anxiety Is as high as health anxiety: Findings from the USA, the UK, and Israel. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 14(3), 566–574. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41811-020-00078-3

Berenbaum, H., Thompson, R. J., & Pomerantz, E. M. (2007). The relation between worrying and concerns: The importance of perceived probability and cost. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(2), 301–311. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018790003416

Blustein, D. L. (1997). A context-rich perspective of career exploration across the life roles. The Career Development Quarterly, 45(3), 260–274. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.1997.tb00470.x

Bono, J. E., Glomb, T. M., Shen, W., Kim, E., & Koch, A. (2013). Building positive resources: Effects of positive events and positive reflection on work-stress and health. Academy of Management Journal, 56(6), 1601–1627. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0272

Borkovec, T. D., Ray, W. J., & Stober, J. (1998). Worry: A cognitive phenomenon intimately linked to affective, physiological, and interpersonal behavioral processes. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 22(6), 561–576. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018790003416

Brandstätter, V., Herrmann, M., & Schüler, J. (2013). The struggle of giving up personal goals: Affective, physiological, and cognitive consequences of an action crisis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(12), 1668–1682. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167213500151

Brandstätter, V., & Schüler, J. (2013). Action crisis and cost–benefit thinking: A cognitive analysis of a goal-disengagement phase. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49(3), 543–553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.10.004

Brewer, E. W., & Shapard, L. (2004). Employee burnout: A meta-analysis of the relationship between age or years of experience. Human Resource Development Review, 3(2), 102–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484304263335

Brown, S. D., Hacker, J., Abrams, M., Carr, A., Rector, C., Lamp, K., Telander, K., & Siena, A. (2012). Validation of a four-factor model of career indecision. Journal of Career Assessment, 20(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072711417154

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Sage.

Carmel, S., & Bernstein, J. H. (2003). Gender differences in physical health and psychosocial well being among four age-groups of elderly people in Israel. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 56(2), 113–131. https://doi.org/10.2190/87yh-45qn-48ty-9hn8

Cooper, B., Eva, N., Fazlelahi, F. Z., Newman, A., Lee, A., & Obschonka, M. (2020). Addressing common method variance and endogeneity in vocational behavior research: A review of the literature and suggestions for future research. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 121, 103472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103472

Crosier, T., Butterworth, P., & Rodgers, B. (2007). Mental health problems among single and partnered mothers: The role of financial hardship and social support. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 42, 6–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-006-0125-4

De Bruijn, E.-J., & Antonides, G. (2020). Determinants of financial worry and rumination. Journal of Economic Psychology, 76, 102233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2019.102233

Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., Singer, D., & Ansar, S. (2022). The global findex database 2021: Financial inclusion, digital payments, and resilience in the age of COVID-19. World Bank Publications.

Dijkstra-Kersten, S. M. A., Biesheuvel-Leliefeld, K. E. M., van der Wouden, J. C., Penninx, B. W. J. H., & van Marwijk, H. W. J. (2015). Associations of financial strain and income with depressive and anxiety disorders. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 69(7), 660–665. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2014-205088

Duffy, R. D., Prieto, C. G., Kim, H. J., Raque-Bogdan, T. L., & Duffy, N. O. (2021). Decent work and physical health: A multi-wave investigation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 127, 103544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2021.103544

Enders, C. K., & Bandalos, D. L. (2001). The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling, 8(3), 430–457. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0803_5

Fa-Kaji, N. M., Silver, E. R., Hebl, M. R., King, D. D., King, E. B., Corrington, A., & Bilotta, I. (2023). Worrying about finances during COVID-19: Resiliency enhances the effect of worrying on both proactive behavior and stress. Occupational Health Science, 7, 111–142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41542-022-00130-y

Ferrari, J. R., & Dovidio, J. F. (2000). Examining behavioral proceses in indecision: Decisional procrastination and decision-making style. Journal of Research in Personality, 34(1), 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.1999.2247

Germeijs, V., Verschueren, K., & Soenens, B. (2006). Indecisiveness and high school students’ career decision-making process: Longitudinal associations and the mediational role of anxiety. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(4), 397–410. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.53.4.397

Ghassemi, M., Bernecker, K., Herrmann, M., & Brandstätter, V. (2017). The process of disengagement from personal goals: Reciprocal influences between the experience of action crisis and appraisals of goal desirability and attainability. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 43(4), 524–537. https://doi.org/10.1177/014616721668905

Grandey, A. A., Sayre, G. M., & French, K. A. (2021). “A blessing and a curse”: Work loss during coronavirus lockdown on short-term health changes via threat and recovery. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 26(4), 261–275. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000283

Hamaker, E. L., Kuiper, R. M., & Grasman, R. P. (2015). A critique of the cross-lagged panel model. Psychological Methods, 20(1), 102–116. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038889

Herrmann, M., & Brandstätter, V. (2013). Overcoming action crises in personal goals – Longitudinal evidence on a mediating mechanism between action orientation and well-being. Journal of Research in Personality, 47(6), 881–893. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2013.09.005

Herrmann, M., & Brandstätter, V. (2015). Action crises and goal disengagement: Longitudinal evidence on the predictive validity of a motivational phase in goal striving. Motivation Science, 1(2), 121–136. https://doi.org/10.1037/mot0000016

Herrmann, M., Brandstätter, V., & Wrosch, C. (2019). Downgrading goal-relevant resources in action crises: The moderating role of goal reengagement capacities and effects on well-being. Motivation and Emotion, 43, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-019-09755-z

Hirschi, A., Nagy, N., Baumeler, F., Johnston, C. S., & Spurk, D. (2018). Assessing key predictors of career success: Development and validation of the career resources questionnaire. Journal of Career Assessment, 26(2), 338–358. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072717695584

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.44.3.513

Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J.-P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5, 103–128. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640

Höge, T., Sora, B., Weber, W. G., Peiró, J. M., & Caballer, A. (2015). Job insecurity, worries about the future, and somatic complaints in two economic and cultural contexts: A study in Spain and Austria. International Journal of Stress Management, 22(3), 223–242. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039164

Holding, A. C., Hope, N. H., Harvey, B., Marion Jetten, A. S., & Koestner, R. (2017). Stuck in limbo: Motivational antecedents and consequences of experiencing action crises in personal goal pursuit. Journal of Personality, 85(6), 893–905. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12296

Holding, A. C., Moore, E., Moore, A., Verner-Filion, J., Ouellet-Morin, I., & Koestner, R. (2021). When goal pursuit gets hairy: A longitudinal goal study examining the role of controlled motivation and action crises in predicting changes in hair cortisol, perceived stress, health, and depression symptoms. Clinical Psychological Science, 9(6), 1214–1221. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702621995214

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Ivanova, S., & Tornikoski, E. T. (2022). Termination of nascent entrepreneurship: The central effects of action crisis in new venture creation. Journal of Small Business Management. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2022.2140160

Jahoda, M. (1982). Employment and unemployment: A social-psychological analysis. Cambridge University Press.

Jiang, Z., Newman, A., Le, H., Presbitero, A., & Zheng, C. (2019). Career exploration: A review and future research agenda. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 110, 338–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.08.008

Kačmár, P., Wolf, B., Bavoľár, J., Schrötter, J., & Lovaš, L. (2023). S-ACRISS R: Slovak adaptation of the action crisis scale. Current Psychology, 42, 18317–11833. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02955-w

Kahn, J. R., & Pearlin, L. I. (2006). Financial strain over the life course and health among older adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 47(1), 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/002214650604700102

Kelloway, E. K., Dimoff, J. K., & Gilbert, S. (2023). Mental health in the workplace. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 10(1), 363–387. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-120920-050527

Kleine, A.-K., Rudolph, C. W., Schmitt, A., & Zacher, H. (2023). Thriving at work: An investigation of the independent and joint effects of vitality and learning on employee health. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 32(1), 95–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2022.2102485

Kleine, A.-K., Schmitt, A., & Wisse, B. (2021). Students’ career exploration: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 131, 103645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2021.103645

Klug, K., Selenko, E., & Gerlitz, J.-Y. (2020). Working, but not for a living: A longitudinal study on the psychological consequences of economic vulnerability among German employees. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 30(6), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2020.1843533

Lebel, R. D., Yang, X., Parker, S. K., & Kamran-Morley, D. (2023). What makes you proactive can burn you out: The downside of proactive skill building motivated by financial precarity and fear. Journal of Applied Psychology, 108(7), 1207–1222. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0001063

Lebert, F., & Voorpostel, M. (2016). Turnover as a strategy to escape job insecurity: The role of family determinants in dual-earner couples. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 37(3), 407–421. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-016-9498-z

Lee, S., & Sanders, R. M. (2013). Fridays are furlough days: The impact of furlough policy and strategies for human resource management during a severe economic recession. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 33(3), 299–311. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X1347726

MacCallum, R. C., Roznowski, M., & Necowitz, L. B. (1992). Model modifications in covariance structure analysis: The problem of capitalization on chance. Psychological Bulletin, 111(3), 490–504. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.490

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., & Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the produce and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39(1), 99–128. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4

Marion-Jetten, A. S., Taylor, G., & Schattke, K. (2022). Mind your goals, mind your emotions: Mechanisms explaining the relation between dispositional mindfulness and action crises. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 48(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167220986310

McFarland, L. A., Reeves, S., Porr, W. B., & Ployhart, R. E. (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on job search behavior: An event transition perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(11), 1207–1217. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000782

Meuris, J., & Leana, C. (2018). The price of financial precarity: Organizational costs of employees’ financial concerns. Organization Science, 29(3), 398–417. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2017.1187

Miller, A. L., & Jhamb, S. (2022). A comprehensive programmatic investigation of the antecedents and consequences related with the great resignation of individuals and organizations–A COVID-19 strategic review and research agenda. Journal of Management Policy & Practice, 23(2), 48–57. https://doi.org/10.33423/jmpp.v23i2.5264

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2017). 1998–2017. Mplus User’s Guide. Muthén & Muthén.

Newman, A., Bavik, Y. L., Mount, M., & Shao, B. (2021). Data collection via online platforms: Challenges and recommendations for future research. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 70(3), 1380–1402. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12302

Odle-Dusseau, H. N., Matthews, R. A., & Wayne, J. H. (2018). Employees’ financial insecurity and health: The underlying role of stress and work–family conflict appraisals. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 91(3), 546–568. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12216

OECD. (2020). OECD (2020), OECD/INFE 2020 International Survey of Adult Financial Literacy. www.oecd.org/financial/education/launchoftheoecdinfeglobalfinancialliteracysurveyreport.htm. Accessed 5 Jan 2024.

Palan, S., & Schitter, C. (2018). Prolific. ac—A subject pool for online experiments. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 17, 22–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbef.2017.12.004

Podsakoff, N. P., Freiburger, K. J., Podsakoff, P. M., & Rosen, C. C. (2023). Laying the foundation for the challenge–hindrance stressor framework 2.0. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 10, 165–199. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-080422-052147

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects on multiple mediator models. Behavioral Research Methods, 40, 879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

PwC. (2023). 2023 PwC Employee financial wellness survey. https://www.pwc.com/us/en/services/consulting/workforce-of-the-future/library/employee-financial-wellness-survey.html. Accessed 5 Jan 2024.

Richardson, J., & Zikic, J. (2007). The darker side of an international academic career. Career Development International, 12(2), 164–186. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430710733640

Richter, A., Vander Elst, T., & De Witte, H. (2020). Job insecurity and subsequent actual turnover: Rumination as a valid explanation? Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 712. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00712

Rudolph, C. W., Allan, B., Clark, M., Hertel, G., Hirschi, A., Kunze, F., Shockley, K., Shoss, M., Sonnentag, S., & Zacher, H. (2021). Pandemics: Implications for research and practice in industrial and organizational psychology. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 14(1–2), 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2020.48

Ryu, S., & Fan, L. (2023). The relationship between financial worries and psychological distress among U.S. adults. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 44(1), 16–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-022-09820-9

Savickas, M. L. (1997). Career adaptability: An integrative construct for life-span, life-space theory. Career Development Quarterly, 45(3), 247–259. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.1997.tb00469.x

Schmitt, A., & Scheibe, S. (2023). Beliefs about the malleability of professional skills and abilities: Development and validation of a scale. Journal of Career Assessment, 31(3), 493–515. https://doi.org/10.1177/10690727221120367

Serenko, A. (2022). The Great Resignation: The great knowledge exodus or the onset of the Great Knowledge Revolution? Journal of Knowledge Management. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-12-2021-0920

Sinclair, R. R., & Cheung, J. H. (2016). Money matters: Recommendations for financial stress research in occupational health psychology. Stress and Health, 32(3), 181–193. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2688

Sonnentag, S. (2017). Career proactivity. In S. K. Parker & U. K. Bindl (Eds.), Proactivity at work: Making things happen in organizations (pp. 67–94). Routledge.

Starrin, B., Åslund, C., & Nilsson, K. W. (2009). Financial stress, shaming experiences and psychosocial ill-health: Studies into the finances-shame model. Social Indicators Research, 91, 283–298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-008-9286-8

Staufenbiel, T., & König, C. J. (2010). A model for the effects of job insecurity on performance, turnover intention, and absenteeism [Article]. Journal of Occupational & Organizational Psychology, 83(1), 101–117. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317908X401912

Ten Brummelhuis, L. L., & Bakker, A. B. (2012). A resource perspective on the work-home interface: The work-home resources model. American Psychologist, 67(7), 545–556. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027974

van den Berg, T., I. J., Elders, L. A. M., & Burdorf, A. (2010). Influence of health and work on early retirement. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 52(6), 576–583. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45009632

Van Eerde, W. (2000). Procrastination: Self-regulation in initiating aversive goals. Applied Psychology, 49(3), 372–389. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00021

Watkins, E. R., & Roberts, H. (2020). Reflecting on rumination: Consequences, causes, mechanisms and treatment of rumination. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 127, 103573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2020.103573

Weisberg, J., & Kirschenbaum, A. (1991). Employee turnover intentions: Implications from a national sample. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 2(3), 359–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585199100000073

Weiss, D., Weiss, M., Rudolph, C. W., & Zacher, H. (2022). Tough times at the top: Occupational status predicts changes in job satisfaction in times of crisis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 139(1), 103804. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2022.103804

Wilson, J. M., Lee, J., Fitzgerald, H. N., Oosterhoff, B., Sevi, B., & Shook, N. J. (2020). Job insecurity and financial concern during the COVID-19 pandemic are associated with worse mental health. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 62(9), 686–691. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000001962

Zacher, H., & Rudolph, C. W. (2023). Subjective wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic: A three-year, 35-wave longitudinal study. The Journal of Positive Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2023.2224757

Zikic, J., & Klehe, U.-C. (2006). Job loss as a blessing in disguise: The role of career exploration and career planning in predicting reemployment quality. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69(3), 391–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2006.05.007

Zikic, J., & Richardson, J. (2007). Unlocking the careers of business professionals following job loss: Sensemaking and career exploration of older workers. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/revue Canadienne Des Sciences De L’administration, 24(1), 58–73. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjas.5

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Antje Schmitt. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Antje Schmitt and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics Approval

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Department of Psychology at the University of Groningen, the Netherlands (reference number PSY-2021-S-0478).

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schmitt, A., Heihal, T.I. & Zacher, H. Financial Worries, Health Complaints, and Career Exploration: The Role of Action Crises. Occup Health Sci (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41542-024-00182-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41542-024-00182-2