Abstract

This study provides insight into how having COVID-19 shifted Black and older Hispanic adults’ organizational perceptions and experiences. We used data from 30 Black and Hispanic full-time men and women over the age of 45 who have had COVID-19, and most have co-occurring physical and mental chronic illness, to examine how having COVID-19 shapes their perceptions of their workplace and organizational interactions. We examine how older Black and Hispanic adults’ intersectional identities further shape their work experiences. Further, we illuminate how COVID-19-related enhanced safety protocols impacted these workers’ emotional and interpersonal experiences by increasing feelings of safety and support, while simultaneously widening relational gaps among coworkers and increasing mental health concerns. We end with workplace practice recommendations, centering an intersectional and Total Worker Health® (TWH) approach, to reduce work-related health and safety hazards with efforts to promote and improve the well-being of older Black and Hispanic workers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic caused employment shocks including workplace shutdowns, decreased staffing, and transitions to remote work (Coates et al., 2020). In the wake of these shocks, workers from disadvantaged groups were more likely to experience pandemic-related disruptions in their employment than those from more advantaged groups (Cortes & Forsythe, 2023). Specifically, older adults and minoritized racial groups experienced disproportionate negative work-related impacts compared to younger and White workers in the U.S. (Goda et al., 2023; Yavorsky et al., 2021). For example, older adult workers experienced worse labor market returns compared to their younger counterparts, including decreased engagement rates, increased unemployment, and longer stints of unemployment threatening their health and economic well-being (Goda et al., 2023). Indeed, an analysis of federal employment data revealed millions of workers over the age of 55 lost their jobs during the COVID-19 pandemic and experienced greater job loss during the period than during the 2007–2009 Great Recession (Gould, 2021). Taken together, these findings suggest older workers experienced substantively negative outcomes as a result of the pandemic downturn and continue to face adverse employment outcomes (Gould, 2021).

Workplaces have adopted COVID-19 protocols to lower the risk of exposure and adapted work processes to accommodate high-risk populations, but COVID-19 remains a health concern for older workers who are at higher risk for infection and serious illness/death from the disease (CDC, 2023). Given that older workers comprise a substantial proportion of the U.S. workforce (17%; U.S., Department of Labor Statistics, 2023), organizations benefit substantially from the presence of older and experienced workers (e.g., Bersin & Chamorro-Premuzic, 2019; Pletzer, 2021), and the importance of creating workplaces that promote well-being for both workers and their organizations (e.g., Fabius & Phares, 2021), it is important to examine how older workers are experiencing the “new normal” of the post-COVID-19 workplace. Further, little is known about how embodying other minoritized identities simultaneously with advanced age might complicate these experiences, given research suggesting that holding multiple minoritized identities may result in compounded disadvantage both inside and outside the workplace (e.g., Moen et al., 2022; Ridgeway & Kricheli-Katz, 2013).

In addition to variations in impact by age, research has also demonstrated that COVID-19-related employment outcomes affected people differently by racial identity (Gemelas et al., 2022). A supplemental survey of the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (2021) 1997 cohort revealed that, of the 41% of individuals reporting not having worked for pay in the prior week, the highest proportions of endorsement came from non-Hispanic Black (56%) and Hispanic respondents (42%) (Auginbaugh & Rothstein, 2022). Further, among those remaining employed, Black and Hispanic workers disproportionately worked in low-income, essential jobs that put them at increased risk for COVID-19 infection (Brown, 2022; Dubay et al., 2020). From an intersectional standpoint, research also indicated that not only were people of color more likely to experience negative work-related outcomes as a result of the pandemic compared to Whites, but that women of color experienced more negative impacts compared to both Whites (men and women) and men of the same race (e.g., higher unemployment rates and slower employment recovery; Yavorsky et al., 2021).

During the pandemic, employers had the option of offering support to workers that may have mitigated negative outcomes for older Black and Hispanic workers. For example, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) issued guidance encouraging employers to implement several public health measures to prevent the spread of SARS-CoV-2, such as time off for vaccination, policies requiring sick and exposed workers to stay home, social distancing, masking, education and training, ventilation, and cleaning and disinfection (OSHA, 2021). Workplaces could also adopt strategies to make organizations more inclusive by age (e.g., by promoting workplace flexibility, matching work tasks to abilities, and providing accommodations; NIOSH, 2023) and expand diversity, equity, access, and inclusion efforts to include an emphasis on worker health and well-being (Sherman et al., 2021). It is unclear whether and how these and other employer actions ultimately affected the experiences of older Black and Hispanic workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Thus, the current research asks the question “How has COVID-19 impacted the workplace experiences of older workers of color?” Using an intersectional lens, (Collins & Bilge, 2020; Crenshaw, 1991) we explore how the COVID-19 pandemic influenced the workplace experiences of older Black and Hispanic workers. An intersectional approach acknowledges that experiences are shaped and influenced by individuals at the intersections of their identities, thereby placing older workers of color in positions of unique vulnerability for poor work and life outcomes. Intersectionality helps explain how life experiences are situated within larger systems of oppression (e.g. ageism, racism) by connecting subjective experiences to social structures, thus illuminating how processes of differentiation shape peoples’ lived experiences. To address our research question, we used an open-text response survey to gather the perspectives of 30 Black and Hispanic full-time workers over the age of 45 who had been diagnosed with COVID-19 at least once. Applying thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) to the resultant textual response data, we generate descriptive themes that provide insight into the unique factors shaping experiences of older minoritized workers in the post-pandemic workplace and, using these themes, propose strategies for strengthening key workplace supports to improve well-being for this population.

Background

Challenges for Working Older Adults

Prior to COVID-19, the workplace was already a challenging place for older workers. First, advanced age is an established risk factor for chronic illness (Anderson & Durstine, 2019), which has been related to both decreases in workability (Boyd & Fortin, 2010; Koolhaas et al., 2013; McGonagle et al., 2022) and work productivity; as well as increases in “presenteeism” (i.e., being present at work, but unable to maximize performance due to health complications; Schultz & Edington, 2007). Physical ability is a major consideration in workforce engagement, but workability is also adversely impacted by mental illness (Emptage et al., 2005; Jason & Erving, 2022; McGonagle et al., 2022). This is especially the case for older adults, as depression in later life is often comorbid with physical issues (Blazer, 2003; Christ et al., 2007), contributing to morbidity, limited functioning (Whiteford et al., 2013), decreased work performance (Wang, 2005), increased work impairment, disability, and absence (Greenberg et al., 2015; Stewart et al., 2003). The health complications that accompany advancing age can thus make the workplace more difficult to navigate and remain engaged with for older workers compared to healthy, younger workers.

Second, advancing age is often accompanied by negative work-related stereotypes that can make the psychological experience of work challenging for older workers (e.g., Turek et al., 2022). Ageism in the workplace persists in the U.S., with age-based stereotypes associating older workers with lower technological competence, resistance to change, and lower engagement creating negative experiences for older workers who bring important institutional knowledge, experience, and wisdom to the workplace (Levy et al., 2022; Nelson & Quick, 2019). Recent investigations have demonstrated an increase in ageism against older adults since the onset of COVID-19 (Levy et al., 2022), suggesting negative age-based workplace experiences (real or perceived) may also have intensified.

The emergence of COVID-19 likely exacerbated existing physical and psychological challenges, while potentially creating new ones. For example, social isolation and loneliness are considered major public health risks for older adults (e.g., Blazer, 2020) that contribute to poor health and well-being outcomes (e.g., Santini et al., 2020; Shankar et al., 2017). Workplaces provide key sources of social interaction with others, but COVID-19 substantively reduced and changed social interactions in the workplace, with work-from-home measures, masking, and social distancing placing greater physical separation between individuals (e.g., Calbi et al., 2021). Both the reduced contact between employees, as well as the altered nature of social interactions brought about by COVID-19 may have created greater experiences of isolation and loneliness for older workers, potentially contributing to new, or exacerbating any pre-existing, physical or mental health issues. Thus, workplace changes encouraging distance among employees, combined with pandemic-related health risk fears about working closely with others, may have set in motion a cyclical process whereby older workers experience isolation that complicates health issues, which consequently leads to more isolation, further exacerbating health issues, and so on, making the post-COVID world of work a more precarious place for this population than it was before the pandemic.

Older Workers of Color: Embodying Multiple Minoritized Identities in the Workplace

Although much of the existing literature identifies pandemic effects separately by age and race, workers experience them simultaneously. Prior research suggests holding multiple minoritized identities (i.e., older age, non-White) may compound the negative experiences associated with each identity separately for a greater experience of disadvantage, collectively. For older workers of racially minoritized populations, this can mean a greater risk for negative health outcomes that impact work ability as well as the “double jeopardy” of experiencing compounding effects of ageism and racism at work (Chatters et al., 2020). For example, older Black and Hispanic people have been found to have poorer health outcomes due to experiencing higher levels of negative bias and discrimination over the life course compared to dominant racial groups (Chatters et al., 2021; Gee & Ford, 2011). Research has also found that adults exposed to regular discrimination are disproportionately burdened by chronic illness, including mental illness, and face greater challenges continuing employment (Shadmi, 2013; Ward & Schiller, 2013); especially their ability to work in later life. Given the potential for older workers to experience negative bias and discrimination related to both older age and their non-White identity, these workers may be at heightened risk for negative physical and mental health outcomes that impact their workplace experiences.

Further, ageism and racism work in similar ways to disadvantage a person or group based on negative stereotypes about older adults and racial minorities. For example, Black and Hispanic adults may be associated with negative stereotypes at work such as laziness and aggression (Dixon & Rosenbaum, 2004), lack of competence and warmth (He et al., 2019), and the Angry Black Woman archetype (Motro et al., 2022) which can lead to unfair race-based evaluations of work-ethic and commitment that may lead to subtle and overt discrimination in job selection and promotion (Quillian et al., 2017). Similarly, stereotypes of older adults as unhealthy, less productive, and expected to retire soon promote ageism in workplace interactions, makes work more challenging, and encourages their transition out of the workforce (Jason & Erving, 2022).

The potential negative implications of navigating multiple minoritized identities in the workplace for older workers were present before the pandemic, but COVID-19 and corresponding historical events added another layer of difficulty by making negative stereotypes associated with both aging and non-Whiteness more salient. Older workers of color experienced more than just baseline double jeopardy. They also had even greater potential for compounded negative experiences, as their age status and negative stereotypes of fragility became more prevalent to their coworkers and employers. For example, Spaccatini et al., (2022) found that the COVID-19 pandemic increased ageism against older adults whereby younger individuals attributed blame to older individuals for the severity of pandemic-related restrictions.

At the same time that ageism increased, major historical events occurred highlighting racial injustice in the U.S. that heightened the salience of racial identity (e.g., the death of George Floyd, #Black Lives Matter movement, anti-immigration political agenda; etc.; Carter et al., 2023; Sanchez & Bennett, 2022) and the disproportionately negative impacts of social structures (e.g., policing, healthcare, immigration policy, etc.) experienced by people of color, making work and everyday life even more mentally and emotionally exhausting for racially minoritized workers (Winters, 2020; Sanchez & Bennett, 2022). Older workers of color remain at higher risk of severe illness and death from COVID-19 compared to White workers but also continue to have higher potential for experiences of ageism and racism simultaneously both inside and outside of the workplace.

The Current Study

The workplace and the socio-political landscape in the United States have changed dramatically since the onset of COVID-19, begging the question of how workers currently experience work in the “new normal” in the aftermath of the pandemic. The discussion above demonstrates how older, racially minoritized populations experience unique challenges both inside and outside of work that affect their experiences of the workplace. However, there is limited extant literature on how the COVID-19 pandemic may have altered the experiences of these older minoritized workers, shaped by the intersections between race, racism, age, and ageism (Jason et al., 2023). Thus, the current research uses qualitative data from Black and Hispanic workers to gain initial insights into whether and how COVID-19 has impacted the work experiences of this unique and critical population of workers using an intersectional lens. Understanding how older Black and Hispanic workers experience the post-COVID workplace may provide important insight into how organizations might support the unique needs of this higher-risk population to encourage both better organizational and individual well-being outcomes.

Data and Methods

Respondents

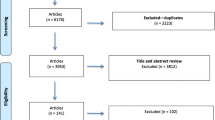

Respondents were recruited via Prolific, an online data collection platform (Palan & Schitter, 2018; Peer et al., 2017). Prolific maintains a panel of over 130,000 vetted respondents from whom researchers can recruit and collect data. To be included in the study, potential respondents needed to indicate they were Black or Hispanic, aged 45 + , worked full time either entirely onsite or in a hybrid work modality, resided in the U.S., and had been diagnosed or strongly suspected they had COVID-19. We used 45 years of age as the cutoff for "older" workers" because of its association with the onset of decreased functional capabilities for some kinds of work (WHO, 1993), increased risk of fatal workplace injuries (Bravo et al., 2022), and higher need for recovery after work (Kiss et al., 2008). We limited the sample to only those workers who were diagnosed (or strongly suspected of a diagnosis) with COVID-19 to gain insights from a population with the greatest likelihood of having their work lives saliently affected by the virus. Given the stigma Black and Hispanic individuals often experience around seeking medical care (Turner-Musa et al., 2020), we believed it was important to include individuals who were not officially tested/diagnosed, but believed they experienced COVID-19 in the sample to ensure we captured a full range of individuals directly impacted by COVID-19 at work.

After deleting responses that did not meet inclusion criteria (1 response), we obtained a final sample of 30 respondents ranging in age from 45 to 63 years old (see Table 1 for full demographic information). The final sample used for analysis included 11 Black men, 8 Black women, 3 Hispanic men, and 8 Hispanic women. Twenty-four of 30 respondents indicated having at least one chronic illness in addition to having had COVID-19. The primarily physical chronic illnesses reported by respondents included high blood pressure (8 respondents), diabetes (7 respondents), heart disease/condition (3 respondents), arthritis (2 respondents), cirrhosis (1 respondent), asthma (1 respondent), and cancer (1 respondent). Notably, 17 respondents (57%) indicated having chronic anxiety or depression, with 15 indicating having at least one of these mental health diagnoses co-occurring with another chronic illness diagnosis.

Procedure

Data Collection

The data collection occurred in March 2023 and was administered to potential respondents from the United States. Upon meeting our inclusion criteria, respondents were shown the study recruitment message in Prolific and presented with the informed consent. Consenting respondents were taken to an online qualitative questionnaire (see Appendix for full list of questions) designed to elicit qualitative responses regarding the workplace experiences of this older working population, specifically concerning the COVID-19 pandemic, and their experiences with racism/ageism in the workplace. The questionnaire included demographic questions as well as twelve questions (a mix of multiple choice and open-ended short answer questions) about respondents’ experiences at work after having COVID-19 including if they thought or felt that having COVID-19 impacted their job opportunities, job security, workplace relationships, assignments, or coworkers’ perceptions of them. Questions ranged from asking specifically about changes in perceptions of work and the workplace (e.g., “Has having COVID-19 changed how you think and/or feel about your workplace?”), to perceptions of the most meaningful supports or safety features in workplaces since having COVID-19 (e.g., “What workplace supports are most meaningful to you after having COVID-19?”). Given the increased likelihood for older adults to have one or more chronic illnesses, we also asked respondents to share any current chronic illness diagnoses to see if COVID-19 presented unique challenges different from or beyond those associated with chronic illness. Respondents indicating they also had at least one chronic illness (e.g., heart disease, diabetes, anxiety, depression) had the opportunity to answer an additional three questions related to their chronic illness in the workplace including any workplace challenges or supports that influence their well-being and job success. Finally, several questions were asked about respondent’s current perceptions of health-related resources at work (e.g., supervisor or coworker support) and perceived challenges for their well-being and job success, including challenges related to racial identity and age. Respondents who completed the survey received approximately $15 in exchange for their responses (rate of $45/hr; average survey completion time = 27.6 min).

Data Analysis

The data collection resulted in a textual corpus for analysis (not including answers to multiple choice responses) consisting of 12,105 words (about 26 pages of double-spaced text). To analyze the open-ended text data, we employed thematic analysis techniques (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Specifically, we used thematic analysis as a way to “report experiences, meanings and the reality of participants” (Braun & Clarke, 2006, p.81) to describe and advance understanding of how COVID-19 has shaped workplace experiences for older workers of color (our research question). In asking our respondents to answer open-ended questions regarding how their experiences have changed and been influenced by COVID-19, we were able to capture participants’ various interpretations of reality and analyze these for patterns that may shed light on the contemporary needs and challenges faced by these groups in the modern workplace.

This method involves an iterative process of open coding, interpretation, and code refinement to inductively allow major themes to emerge from the data (Braun & Clarke, 2006). As our goal for this research is to describe and interpret experiences of older workers of color in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, we chose a semantic level of analysis, allowing participants’ own words to drive our interpretations (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The first phase of analysis involved an open coding process, whereby the first two authors and one trained graduate research assistant independently read through the data and created codes describing interpretations of the primary drivers of participant responses to prompts (for each participant at the question response level). Codes were assigned freely and without predetermined criteria or labels based on the specific phrases submitted by participants, enabling the researchers to assess the meaning of each response in an inductive, yet data-driven way (Braun & Clarke, 2006, p.84). Open codes were recorded alongside the data set in files unique to each researcher and included notes with questions and descriptions or explanations of codes for use in later interpretive discussions.

After the open coding process was finished, the coders engaged in a second phase where they shared their observations and coding schemes, discussing possible interpretations and possibilities for refinement. An iterative process of re-reviewing the data, discussing observations, and refining codes and themes continued over several meetings across a two-month time period, in between which independent reviewing of refined codes and consulting the data occurred until agreement was reached on the final list of emergent themes (Tracy, 2019). Table 2 provides an illustration of this evolution of open codes to thematic categories.

Findings

Having COVID-19 Heightened Occupational Health Concerns

A majority of respondents affirmed that experiencing COVID-19 increased their concerns about their health as it related to work. Physical, mental, and social well-being concerns were among the most prevalent topics reported by respondents, with several indicating they still experience high levels of fear and anxiety about coming to work given the potential transmission of COVID-19. Notably, these concerns seemed to transcend racial and gender lines with 14 of 18 Black, 8 of 12 Hispanic, 10 of 15 men, and 12 of 15 women indicating that COVID-19 changed how they thought and felt about their workplaces. Lingering anxiety around health and safety risks at work emerged across the sample in responses such as, “I worry about getting sick and endangering the health of my children” (Hispanic woman, age 45, office manager, hybrid work), “I feel more fearful now about being around my co-workers than ever before” (Hispanic man, age 50, business administrator, hybrid work), “I am more anxious around people. I feel self-conscious when I'm the only person wearing a mask. Group meeting in rooms with closed doors make me very nervous” (Black woman, age 61, assistant professor, hybrid work), and “I have become more cautious of my health and my interactions” (Black man, age 62, architect, hybrid work). While much of the messaging around COVID-19 from political and organizational leaders at the time of the survey centered around the idea that COVID-19 was “over” (Ellis, 2023), this was not the experience of respondents in this study.

Mental Illness Impact at Work Exacerbated by COVID-19

There was no clear association between infection with COVID-19 and chronic physical illness in our study data. However, many respondents described how the COVID-19 pandemic increased chronic mental health struggles, such as experiencing more stress, anxiety, and depression during the height of the pandemic, with some indicating a sustained increase in mental health struggles. For example, a 45-year-old Hispanic woman (supervisor, works onsite) noted, “I think [my depression and anxiety] got worse in the beginning [of COVID-19] from fear of the unknown, but have gradually gotten better. My anxiety is not as bad as what it first was”, while a 52-year-old Black man (consultant, works onsite) noted, “I experienced worsened [depression and anxiety] symptoms after contracting the virus…”.

For the few respondents whose physical chronic illness got worse during the pandemic (i.e., over the last three years), in most of these cases, worsening physical health was comorbid with worsening mental illness. For instance, a 50-year-old Black woman (healthcare nurse, works onsite) with high blood pressure, depression, and anxiety noted, “I do have more heart palpitations than before and my anxiety gets worse at times.” A 50-year-old Hispanic woman (business administrator, hybrid work) described how her anxiety has gotten worse and how it matters for her work experience:

Even after having COVID a year ago, I still don't feel the energy that I used to have…I also continue to have a difficult time concentrating on work projects that before COVID were easy for me.

Another Black woman, age 61(assistant professor, hybrid work), had similar concerns:

My anxiety has increased since stay-at-home orders were relaxed. Staying at home was one of the happiest times of the last few years. Anyone who is not wearing a mask can be COVID-positive. While my employer encourages vaccinations, they are not mandated and HIPAA protocol means I can't ask people if they've been vaccinated. Any medication to treat congestion threatens to increase my blood pressure.

A Hispanic woman, age 54, (support clerk, hybrid work) stated, “I feel [my illnesses] are a bit worse, like my anxiety… I can’t feel safe and [I worry] something is gonna happen.” When the respondent noted “something is going to happen,” it was similar to other respondents who were concerned about COVID-19 exposure at work and or that their immune systems would be compromised. A 51-year-old Black woman (nurse, hybrid work) explained:

I got so scared to interact with people, especially those without any form of protection or nose mask on. People began to think I was too paranoid because of my fear of having physical contact with them at work.

As these workers explained, one cannot untangle the relationship and impact of COVID-19, mental health, and work experiences. In some cases, working from home during quarantine helped with anxiety and depression, in other cases the overwhelming concerns about COVID-19 were not buffered by home quarantine. Either way, workers noted the cognitive effort required in managing their thoughts and social interactions at work.

Employer Response to COVID-19 Shifted Employee Perceptions about their Organization

Respondents indicated that their organizations’ handling of health and safety measures during and after the height of COVID-19 restrictions changed how they viewed and felt about their organization. Some respondents described how they found a new appreciation for their workplaces after seeing “how much they care about their employees through their actions taken during COVID” (Hispanic man, age 52, VP Technology, works onsite). “Before the pandemic, I used to take my workplace for granted. I saw it as a mundane part of my daily routine that I had to endure to earn a living,” one respondent (Black man, age 52, consultant, works onsite) said. “However, since the outbreak of COVID-19, my perspective has shifted dramatically. I have come to appreciate the safety measures put in place to protect employees from the virus.” Comments like this suggest that older Black and Hispanic workers who perceived their organizations as taking meaningful steps toward protecting their health and safety with COVID-specific efforts experienced a positive change in their attitudes toward the organization as a whole.

On the other hand, respondents who perceived their organization as doing too little, or nothing at all, to protect their health and safety during the pandemic experienced a serious negative shift in attitudes toward and about their organization. One respondent (Hispanic woman, age 57, healthcare management, works onsite) commented “I no longer have the same respect and trust in my employers because of the negative way I was treated when I was exposed to COVID at my job and when I fell ill,” suggesting her experience with COVID-19 at her organization has altered her overall opinion of the company for the worse. Similarly, another respondent (Black man, age 46, maintenance manager, works onsite) explained that he “lost a little trust and respect for upper management and HR due to how they handled issue[s] with COVID. I started to ask more questions about policy and raising issues with how things are being done.”

Relationships and Social Perceptions Changed after COVID-19

Although some respondents reported that the COVID-19 pandemic increased their coworkers’ awareness of and sympathy for their health considerations, over one-third of the sample indicated negative changes to the quality of their work relationships as a result of the pandemic in their responses. Respondents offered several explanations for why their workplace relationships suffered. First, the transition from working in person to working from home increased feelings of isolation. Although many individuals in our sample described the benefits of working from home to ensure health and safety, a perceived social downside to flexplace was also present. Multiple respondents relayed that work-from-home measures had diminished their existing relationships; for example, one respondent stated, “due to reduction of hours and employees allowed to work from home, I no longer feel as close to fellow peers who I interacted with daily” (Hispanic woman, age 47, director of management, works hybrid). Another respondent shared “With more working from home there is not as much interaction with coworkers, so the work relationships are not built” (Hispanic man, age 46, equipment specialist, works hybrid).

Second, respondents made personal decisions to distance themselves from coworkers to protect their health. An unintended consequence of their social distancing was a loss of closeness with their peers. One respondent (Black woman, age 48, consultant, works hybrid) said “I used to sit in groups for lunch and laugh over issues and have discussions. I think about these actions too much today and try my possible best to limit groups.” Another respondent (Black man, age 62, architect, works hybrid) explained that this loss of closeness was made worse in his case by coworkers’ perceptions that he was being overly cautious regarding COVID-19:

My workplace relationships have drastically changed, I have become less touchy and more cautious. Due to that, most people have developed a different perception about me and feel as though I am overreacting.

Third, some respondents felt that their workplace relationships had declined not because of their actions but because of coworkers’ decisions to socially distance. A few respondents who caught COVID-19 felt that some of their coworkers judged and stigmatized them for taking risks and getting sick. As one respondent (Black man, age 52, consultant, works onsite) explained:

My colleagues view me differently as someone who has contracted the virus. They are worried about getting infected themselves or feel sympathy for me. This has resulted in a change in the way we interact and work together… Some see me as irresponsible for contracting the virus or not taking enough precautions. Others view me with empathy and understanding.

Multiple respondents noted such stigma remaining in the workplace, with another respondent reporting that “no matter how careful you are, [if] you happen to catch COVID, people look at you as not being clean. I feel that they think you are being reckless and not follow[ing] COVID protocols” (Hispanic woman, age 54, support clerk, works hybrid).

Race(ism) and Age(ism) Impacts

Notably, when asked, “Do you think your age and/or race impact your experiences at work?”, respondents did not indicate a perceived direct connection between racial identity, age, and having COVID-19 at work. However, approximately half our sample agreed that their racial identity and/or older age influenced their general workplace experiences, with a greater proportion of Black respondents endorsing this sentiment than Hispanic respondents (72% of Black respondents compared to 25% of Hispanic respondents, respectively). Further, the content of responses indicated that race and/or age affected workplace experiences differently for Hispanic respondents and Black respondents. For instance, of the three Hispanic respondents who reported that their age or race affected their work experiences, two said that their coworkers made inappropriate comments or jokes that were racist. A respondent (Hispanic woman, age 45, office manager, works hybrid) shared:

My manager frequently makes xenophobic and racist comments that make me feel frustrated and upset and yet she wants me to agree with her, but I am not White like her, and she gets angry if I don't collude with her.

Experiences of ageism among Hispanic respondents were mixed. Although one respondent described colleagues making inappropriate ageist comments, another Hispanic respondent (man, age 52, VP technology, works onsite) described a positive effect of his age on his experiences, stating “Well, since I’m older, my peers look up to me a lot more because of my experience and work knowledge. They look to me as a leader and a coach for new employees and leaders.”

Two Black respondents similarly described how their race or older age positively impacted their workplace experiences due to benefits of seniority or the perspective their race/age gives them to learn about others, while the other Black respondents described both personal instances of microaggression and other kinds of negative race- and age-based experiences including discrimination, bias, and stereotyping. Black respondents discussed experiences with race-based hostility at work, reflected in respondent comments such as “Because I am Black, I tend to face microaggressions or hostile behavior from coworkers or supervisors” (Black man, 48, architect, works onsite), as well as having their self-image and opportunities limited by racial stereotypes:

I have experienced discrimination and microaggressions based on my race and age. These experiences have included being passed over for promotions or not being given the same opportunities as my non-Black colleagues. I have also experienced racial bias and stereotyping in the workplace, which can impact my confidence and sense of belonging.

Further, there was recognition of intersectional race-based bias in Black respondents’ responses. Specifically, respondents noted negative workplace experiences related to intersectional race, age, gender, and health status. One respondent (Black man, age 63, technical analyst, works onsite) described, “Racism and ageism are everywhere, including the work environment”, suggesting his race and age combine to affect his real or perceived workplace success. Regarding the intersection of race and gender, one respondent noted, “Women of color experience both racism and sexism in professional settings, which can lead to decreased job opportunities and lower wages” (Black woman, age 49, manager, works hybrid). Regarding race and health status, one respondent (Black woman, age 51, nurse, works hybrid) explained:

My race had an impact on some of the experiences I face at work. This is because I realized sometimes, management was biased towards people who are White and assumed that people of color should be able to do the work even when they are not in the best position due to health issues.

Together, these findings illustrate that the Black respondents in our sample experienced higher perceptions of negative race-based experiences at work, including those that include other intersecting identities, compared to the Hispanic individuals we surveyed.

Discussion and Conclusion

Findings from this investigation suggest COVID-19 continues to meaningfully impact the workplace experiences of older Black and Hispanic workers. While much of the world seems eager to move on or get “back to normal” from the pandemic (Philips, 2022), residual fear and anxiety around health and safety at work remain major concerns for older Black and Hispanic workers in this study. These concerns are consistent with the context of health disparities associated with COVID-19 and other illnesses (CDC, 2023). Our results indicate that employers’ past and current actions to address COVID-19 affected how Black and Hispanic respondents feel about their employers. However, enhanced safety protocols seem to have had unintended consequences on these workers’ emotional and interpersonal experiences, specifically, simultaneously increasing feelings of safety and support while widening relational gaps among coworkers and increasing mental health concerns. Based on these results, future research might explore how employers can enhance the well-being of older Black and Hispanic workers by improving support for psychological safety and social well-being.

Intersectional Considerations

While patterns of perceived COVID-19 impacts did not appear to meaningfully differ by race or age of respondents, we did see meaningful patterns of reports of negative race-based and intersectional experiences at work. Specifically, Black respondents reported higher perceived negative racialized experiences compared to Hispanic individuals in our data. We do not suggest that older Hispanic workers do not experience race-based negativity in the workplace, but our findings do pose the question of whether racialized experiences may be more salient for older Black workers compared to other older Hispanic workers. Future research might continue to interrogate how experiences of racism and discrimination vary across racial and ethnic groups.

There is evidence to support focused attention on anti-Black racism in the workplace. Anti-Black racism has been a central social issue in the United States for centuries given its history of Black slavery and segregation of Black citizens. However, current events and social movements surrounding unequal negative Black experiences in the U.S. have made anti-Black racism a particularly salient issue for Americans in recent years, with social and political movements centering the issue during the height of the pandemic (Lavalley & Johnson, 2022). It is not only possible that older Black workers continue to experience significant levels of race-based hardship and challenges at work, but that these experiences remain particularly salient in their lives given their magnified presence in political and social public discourse. Thus, these workers may be at particularly high risk for negative work outcomes as the combination of their race, age, and health statuses increase the likelihood of multiple and co-occurring physical, psychological, and social challenges at work.

We recommend that organizations employing older minoritized workers be mindful that these populations already endure more negative workplace experiences compared to majority workers, at baseline, due to race and intersecting minority identities (Ray, 2019). Despite progress regarding diversity, equity, accessibility, and inclusion efforts, these initiatives continue to be questioned and threatened (e.g., Chen & Weber, 2023) while racial minority workers, and perhaps Black workers, especially, continue to experience negative interactions at work. These negative racialized experiences may combine with negative experiences associated with other identities (e.g., advancing age, gender, health status), and can be exacerbated by the presence of chronic illness and the trauma of the global pandemic, to put such workers at high risk for poor health and work-related outcomes.

Although our sample yielded Black and Hispanic workers who may have some socio-economic protections (e.g., being overall younger (mean = 50 years), gainfully employed, college-educated, disproportionally partnered or married, 80% in white-collar jobs, often in management), they were still highly likely to have had both chronic physical and mental health diagnoses on top of reports of higher anxiety and social isolation brought about by COVID-19 workplace practices and policies. As such, even the buffers that may lead to being healthier and economically secure than their more socio-economically vulnerable counterparts did not protect them from the harmful impacts of COVID-19.

Workplace Practice Implications

Total Worker Health® (TWH) approaches, which combine efforts to reduce work-related health and safety hazards with efforts to promote and improve worker well-being (Lee et al., 2016), may help improve the well-being of older Black and Hispanic workers. TWH grew out of research suggesting that integrating protection and promotion strategies may lead to better worker outcomes than focusing on protection or promotion alone (NIOSH, 2012). The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) developed a National Occupational Research Agenda to advance TWH, which emphasizes that employers should consider the unique needs of aging workers and those with higher health risks to protect and advance worker well-being (NIOSH, 2016). A newer NIOSH agenda reflects that research gaps remain in our understanding of how worker characteristics relate to worker experiences and outcomes (NIOSH, 2020). This agenda specifically suggests that researchers develop a better understanding of workplace disparities and best practices for supporting affected workers (NIOSH, 2020).

TWH approaches to advance the well-being of older Black and Hispanic workers in light of pandemic challenges might take the form of many different policies, programs, and practices. Of most direct relevance, employers can adopt public health measures designed to protect workers from COVID-19. Specifically, respondents in the current sample emphasized the importance of continuing to offer flexible work arrangements (e.g., working from home), maintaining and encouraging rigorous cleaning and sanitizing protocols (e.g., hand washing, surface sanitization, mask-wearing, enhanced ventilation systems, etc.), and paid time off for COVID-19 recovery as the most impactful physical health and safety measures they appreciated or desired from their employers. Importantly, the fact that the majority of individuals we surveyed (80%) also had one or more chronic illnesses in addition to having had COVID-19 supports prior research finding older minority workers are at greater risk for chronic illness (Erving & Frazier, 2021). This suggests the maintenance of such health and safety protocols may be critical to both the physical and mental well-being of these worker populations.

It is also important for workplaces to acknowledge mental challenges such as anxiety and depression for workers and coordinate to adjust the work environment according to worker’s mental conditions (Fukuura & Shigematsu, 2021). In addition to the negative personal mental health challenges that our respondents reported, one can consider that resentment related to how employers handled COVID-19 may have the power to carry over and negatively affect relationships with their respective organizations. Thus, both employees and organizations alike would likely benefit from continuing to incorporate protective health measures, mental health, and social supports, both related to COVID-19 and other health concerns, into core organizational policies and practices.

We recommend organizations test the proposed supports for workers’ physical, mental, and social well-being in their workplaces. Our respondents’ comments regarding practices during the pandemic indicate that their workplace responses to COVID-19 meaningfully shaped important internal employee workplace attitudes. Taking action steps perceived as protective of one’s health and safety may enhance attitudes, such as perceived organizational support (the degree to which an organization is viewed as caring about employees, (Eisenberger et al., 2020) and affective commitment (i.e., the emotional attachment a person feels with their organization) (Meyer & Allen, 1997). These employee attitudes have both been shown to affect worker well-being and key organizational outcomes, such as reducing turnover and increasing job performance (Kurtessis et al., 2017). However, employer inaction risked the opposite effect; respondents who perceived that their employers had not taken adequate steps to protect workers’ health reported more negative attitudes about their organizations than they had prior to the pandemic.

Limitations and Future Research

While our study, as an initial investigation into the post-COVID-19 work experiences of older Black and Hispanic workers, offers many helpful insights, it is not without limitations. First, this study is based on a convenience sample of 30 respondents and the results presented here do not represent the experiences of all older Black and Hispanic workers. Of note, respondents in the sample were highly educated, and most were partnered or married, both of which provide financial security nets and social support that low-wage/single-income and lower-educated workers may not have. In addition, the Black workers we surveyed worked in a variety of occupations and sectors, including blue-collar jobs and white-collar jobs with a mix of individual contributor and supervisory positions represented. Our sample of Hispanic individuals, however, did not include any blue-collar workers, and the majority held supervisory positions at the management level. As such, this initial investigation lays a great foreground to inform a future study with a more diverse sample. Second, using an online short-answer questionnaire prevented us from probing respondent responses or clarifying questions for respondents. Although Prolific has demonstrated its legitimacy as a scientific data collection tool (Eyal et al., 2021), more nuanced information regarding workers’ experiences may be obtained with in-depth interviews in the future, especially for potential respondents with less education. Future research could further replicate, test, and extend this study with a nationally representative sample of workers, including White workers, to gain insights into larger patterns of behavior and analyze comparable work experiences among different worker demographics.

Conclusion

In this study, we have provided a foundation for researchers, employers, and policymakers to understand the experiences of, and strategize how to best support, older minoritized workers in the post-pandemic workplace. For many older Black and Hispanic adults, the workplace was already a challenging environment. Our findings suggest the health and social impacts of COVID-19 exacerbated employment, workability, and health challenges (including mental health) for older minoritized workers. These findings compel us to acknowledge the impacts of intersectionality on marginalized working adults and support the application of TWH approaches to best meet their needs as they continue to work longer.

Data Availability

Data from this study are not currently shared as researchers have not completed planned or expected analyses for future publications. Contact corresponding author for inquiries.

References

Anderson, E., & Durstine, J. L. (2019). Physical activity, exercise, and chronic diseases: A brief review. Sports Medicine and Health Science, 1(1), 3–10.

Auginbaugh, A., & Rothstein, D. S. (2022). How did employment change during the COVID-19 pandemic? Evidence from a new BLS survey supplement. Beyond the Numbers: Employment and Unemployment, 11(1). Retrieved April 22, 2023, from https://www.bls.gov/opub/btn/volume-11/how-did-employment-change-during-the-COVID-19-pandemic.htm

Bersin, J., & Chamorro-Premuzic, T. (2019, September 26). The Case for Hiring Older Workers. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2019/09/the-case-for-hiring-older-workers

Blazer, D. G. (2003). Depression in late life: Review and commentary. The Journals of Gerontology Series a: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 58(3), M249–M265.

Blazer, D. (2020). Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults—A Mental Health/Public Health Challenge. JAMA Psychiatry, 77(10), 990–991. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1054

Boyd, C. M., & Fortin, M. (2010). Future of multimorbidity research: How should understanding of multimorbidity inform health system design? Public Health Reviews, 32(2), 451–474. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03391611

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bravo, G., Viviani, C., Lavallière, M., Arezes, P., Martínez, M., Dianat, I., ... & Castellucci, H. (2022). Do older workers suffer more workplace injuries? A systematic review. International journal of occupational safety and ergonomics, 28(1), 398–427.

Brown, J. L. (2022). Addressing racial capitalism’s impact on Black essential workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: Policy recommendations. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-022-01346-y

Calbi, M., Langiulli, N., Ferroni, F., Montalti, M., Kolesnikov, A., Gallese, V., & Umiltà, M. A. (2021). The consequences of COVID-19 on social interactions: An online study on face covering. Scientific Reports, 11(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-81780-w

Carter, M. K. A., McGill, L. S., Aaron, R. V., Hosey, M. M., Keatley, E., & Sanchez Gonzalez, M. L. (2023). We still cannot breathe: Applying intersectional ecological model to COVID-19 survivorship. Rehabilitation Psychology, 68(2), 112–120. https://doi.org/10.1037/rep0000495

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). CDC COVID data tracker. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved April 22, 2023, from https://COVID.cdc.gov/COVID-data-tracker/#datatracker-home

Chatters, L. M., Taylor, H. O., & Taylor, R. J. (2020). Older Black Americans during COVID-19: Race and age double jeopardy. Health Education & Behavior, 47(6), 855–860. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198120965513

Chatters, L. M., Taylor, H. O., & Taylor, R. J. (2021). Racism and the life course: Social and health equity for Black American older adults. Public Policy & Aging Report, 31(4), 113–118. https://doi.org/10.1093/ppar/prab018

Chen, T.-P., & Weber, L. (2023). The Rise and Fall of the Chief Diversity Officer—WSJ. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/chief-diversity-officer-cdo-business-corporations-e110a82f

Christ, S. L., Lee, D. J., Fleming, L. E., LeBlanc, W. G., Arheart, K. L., Chung-Bridges, K., ... & McCollister, K. E. (2007). Employment and occupation effects on depressive symptoms in older Americans: does working past age 65 protect against depression?. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 62(6), S399-S403.

Coates, B., Cowgill, M., Chen, T., & Mackey, W. (2020). Shutdown: estimating the COVID-19 employment shock. Melbourne: Grattan Institute.

Collins, P. H., & Bilge, S. (2020). Intersectionality. John Wiley & Sons.

Cortes, G. M., & Forsythe, E. (2023). Heterogeneous labor market impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic. ILR Review, 76(1), 30–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/00197939221076856

Crenshaw, K., (1991). Mapping the Margins: Identity Politics, Intersectionality, and Violence Against Women. Stanford Law Review 43(6): 1241–1299

Dubay, L., Aarons, J., Brown, K. S., & Kenney, G. M. (2020). How risk of exposure to the coronavirus at work varies by race and ethnicity and how to protect the health and well-being of workers and their families. Washington DC: Urban Institute. Retrieved April 22, 2023, from https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/103278/how-risk-of-exposure-to-the-coronavirus-at-work-varies_1.pdf

Dixon, J. C., & Rosenbaum, M. S. (2004). Nice to know you? Testing contact, cultural, and group threat theories of anti-Black and anti-Hispanic stereotypes. Social Science Quarterly, 85(2), 257–280. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0038-4941.2004.08502003.x

Eisenberger, R., Rhoades Shanock, L., & Wen, X. (2020). Perceived organizational support: Why caring about employees counts. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 7, 101–124. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012119-044917

Ellis, R. (2023). Who leader expects end of COVID pandemic in 2023. WebMD. Retrieved April 22, 2023, from https://www.webmd.com/COVID/news/20230318/who-leader-expects-end-of-COVID-pandemic-in-2023

Emptage, N. P., Sturm, R., & Robinson, R. L. (2005). Depression and comorbid pain as predictors of disability, employment, insurance status, and health care costs. Psychiatric Services, 56(4), 468–474. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.56.4.468

Erving, C. L., & Frazier, C. (2021). The association between multiple chronic conditions and depressive symptoms: Intersectional distinctions by race, nativity, and gender. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 62(4), 599–617. https://doi.org/10.1177/00221465211040174

Eyal, P., David, R., Andrew, G., Zak, E., & Ekaterina, D. (2021). Data quality of platforms and panels for online behavioral research. Behavior Research Methods, 54(4), 1643–1662. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-021-01694-3

Fabius, R., & Phares, S. (2021). Companies That Promote a Culture of Health, Safety, and Well-being Outperform in the Marketplace. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 63(6), 456. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000002153

Fukuura, Y., & Shigematsu, Y. (2021). The work ability of people with mental illnesses: A conceptual analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(19), 10172. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910172

Gee, G. C., & Ford, C. L. (2011). Structural racism and health inequities: Old issues, new Directions. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 8(1), 115–132. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1742058x11000130

Gemelas, J., Davison, J., Keltner, C., & Ing, S. (2022). Inequities in Employment by Race, Ethnicity, and Sector During COVID-19. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 9(1), 350–355. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-00963-3

Goda, G. S., Jackson, E., Nicholas, L. H., & Stith, S. S. (2023). The impact of COVID-19 on older workers’ employment and Social Security spillovers. Journal of Population Economics, 36(2), 813–846. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-022-00915-z

Gould, E. (2021). Older workers were devastated by the pandemic downturn and continue to face adverse employment outcomes. Economic Policy Institute. Retrieved April 22, 2023, from https://www.epi.org/publication/older-workers-were-devastated-by-the-pandemic-downturn-and-continue-to-face-adverse-employment-outcomes-epi-testimony-for-the-senate-special-committee-on-aging/

Greenberg, P. E., Fournier, A. A., Sisitsky, T., Pike, C. T., & Kessler, R. C. (2015). The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2005 and 2010). The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 76(2), 155–162. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.14m09298

He, J. C., Kang, S. K., Tse, K., & Toh, S. M. (2019). Stereotypes at work: Occupational stereotypes predict race and gender segregation in the workforce. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 115, 103318.

Jason, K., & Erving, C. L. (2022). The Intersecting consequences of race-gender health disparities on workforce engagement for older workers: An examination of physical and mental health. Social Currents, 9(1), 45–69.

Jason, K., Wilson, M., Catoe, J., Brown, C., & Gonzalez, M. (2023). The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Black and Hispanic Americans’ Work Outcomes: a Scoping Review. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 1–16.

Kiss, P., De Meester, M., & Braeckman, L. (2008). Differences between younger and older workers in the need for recovery after work. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 81, 311–320.

Koolhaas, W., van der Klink, J. J., Vervoort, J. P., de Boer, M. R., Brouwer, S., & Groothoff, J. W. (2013). In-depth study of the workers’ perspectives to enhance sustainable working life: Comparison between workers with and without a chronic health condition. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 23(2), 170–179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-013-9449-6

Kurtessis, J. N., Eisenberger, R., Ford, M. T., Buffardi, L. C., Stewart, K. A., & Adis, C. S. (2017). Perceived organizational support: A meta-analytic evaluation of organizational support theory. Journal of Management, 43(6), 1854–1884. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315575554

Lavalley, R., & Johnson, K. R. (2022). Occupation, injustice, and anti-Black racism in the United States of America. Journal of Occupational Science, 29(4), 487–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2020.1810111

Lee, M. P., Hudson, H., Richards, R., Chang, C. C., Chosewood, L. C., & Schill, A. L. (2016). Fundamentals of total worker health approaches: essential elements for advancing worker safety, health, and well-being. Retrieved April 22, 2023, from https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/43275

Levy, S., Lytle, A., & Macdonald, J. (2022). The worldwide ageism crisis. Journal of Social Issues, 78, 743–767. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12568

McGonagle, A. K., Bardwell, T., Flinchum, J., & Kavanaugh, K. (2022). Perceived work ability: A constant comparative analysis of workers’ perspectives. Occupational Health Science, 6, 207–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41542-022-00116-w

Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1997). Commitment in the workplace: Theory, research, and application. Sage publications.

Moen, P., Flood, S. M., & Wang, J. (2022). The Uneven Later Work Course: Intersectional Gender, Age, Race, and Class Disparities. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 77(1), 170–180. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbab039

Motro, D., Evans, J. B., Ellis, A. P. J., & Benson, L. I. I. I. (2022). Race and reactions to women’s expressions of anger at work: Examining the effects of the “angry Black woman” stereotype. Journal of Applied Psychology, 107(1), 142–152. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000884

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) (2023). Productive aging and work. Retrieved October 2, 2023, from https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/productiveaging/default.html

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). (2012). Research compendium: The NIOSH Total Worker Health (™) Program: Seminal research papers 2012. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH). https://doi.org/10.26616/nioshpub2012146

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health/NIOSH. (2016). National occupational research agenda (NORA)/national Total Worker Health® agenda (2016–2026): A national agenda to advance total worker health® research, practice, policy, and capacity. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). Retrieved April 22, 2023, from https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2016-114/pdfs/nationaltwhagenda2016-1144-14-16.pdf

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health/NIOSH. (2020). National occupational research agenda for healthy work design and well-being. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). Retrieved January 19, 2024, from https://www.cdc.gov/nora/councils/hwd/pdfs/Final-National-Occupational-Research-Agenda-for-HWD_January-2020.pdf

Nelson, D. L., & Quick, J. (2019). OrgB6. Cengage.

Occupational Safety and Health Administration. (2021). Protecting workers: Guidance on mitigating and preventing the spread of COVID-19 in the workplace. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Retrieved April 27, 2023, from https://www.osha.gov/coronavirus/safework

Palan, S., & Schitter, C. (2018). Prolific.ac—a subject pool for online experiments. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 17, 22–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbef.2017.12.004

Peer, E., Brandimarte, L., Samat, S., & Acquisti, A. (2017). Beyond the Turk: Alternative platforms for crowdsourcing behavioral research. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 70, 153–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2017.01.006

Phillips, S. (2022). This is the phase of the pandemic where life returns to normal. Time Magazine. Retrieved April 22, 2023, from https://time.com/6203058/COVID-19-pandemic-return-to-normal-column/

Pletzer, J. L. (2021). Why older employees engage in less counterproductive work behavior and in more organizational citizenship behavior: Examining the role of the HEXACO personality traits. Personality and Individual Differences, 173, 110550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110550

Prolific.co (2023). Is online crowdsourcing a legitimate alternative to lab-based research? Prolific. Retrieved April 22, 2023, from https://researcher-help.prolific.co/hc/en-gb/articles/360009223133-Is-online-crowdsourcing-a-legitimate-alternative-to-lab-based-research-

Quillian, L., Pager, D., Hexel, O., & Midtbøen, A. H. (2017). Meta-analysis of field experiments shows no change in racial discrimination in hiring over time. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(41), 10870–10875. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1706255114

Ray, V. (2019). A Theory of Racialized Organizations. American Sociological Review, 84(1), 26–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122418822335

Ridgeway, C. L., & Kricheli-Katz, T. (2013). Intersecting Cultural Beliefs in Social Relations: Gender, Race, and Class Binds and Freedoms. Gender & Society, 27(3), 294–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243213479445

Sanchez, G., R., & Bennett, C. (2022). Anti-immigrant campaign ads negatively impact Latinos’ mental health and make them feel unwelcome in the United States. Brookings. Retrieved September 30, 2023, from https://www.brookings.edu/articles/anti-immigrant-campaign-ads-negatively-impact-latinos-mental-health-and-make-them-feel-unwelcome-in-the-united-states/

Santini, Z. I., Jose, P. E., Cornwell, E. Y., Koyanagi, A., Nielsen, L., Hinrichsen, C., Meilstrup, C., Madsen, K. R., & Koushede, V. (2020). Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and symptoms of depression and anxiety among older Americans (NSHAP): A longitudinal mediation analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 5(1), e62–e70. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30230-0

Schultz, A. B., & Edington, D. W. (2007). Employee health and presenteeism: A systematic review. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 17(3), 547–579. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-007-9096-x

Shadmi, E. (2013). Disparities in multiple chronic conditions within populations. Journal of Comorbidity, 3(2), 45–50. https://doi.org/10.15256/joc.2013.3.24

Shankar, A., McMunn, A., Demakakos, P., Hamer, M., & Steptoe, A. (2017). Social isolation and loneliness: Prospective associations with functional status in older adults. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 36(2), 179–187. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000437

Sherman, B. W., Kelly, R. K., & Payne-Foster, P. (2021). Integrating Workforce Health Into Employer Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Efforts. American Journal of Health Promotion, 35(5), 609–612. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890117120983288

Spaccatini, F., Giovannelli, I., & Pacilli, M. G. (2022). “You are stealing our present”: Younger people’s ageism towards older people predicts attitude towards age-based COVID-19 restriction measures. The Journal of Social Issues, 78(4), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12537

Stewart, W. F., Ricci, J. A., Chee, E., Hahn, S. R., & Morganstein, D. (2003). Cost of lost productive work time among US workers with depression. JAMA, 289(23), 3135–3144. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.23.3135

Tracy, S. J. (2019). Qualitative research methods: Collecting evidence, crafting analysis, communicating impact. John Wiley & Sons.

Turek, K., Oude Mulders, J., & Stypińska, J. (2022). Different Shades of Discriminatory Effects of Age Stereotypes in the Workplace: A Multilevel and Dynamic Perspective on Organizational Behaviors. Work, Aging and Retirement, 8(4), 343–347. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/waac019

Turner-Musa, J., Ajayi, O., & Kemp, L. (2020). Examining social determinants of health, stigma, and COVID-19 disparities. Healthcare, 8(2), 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8020168

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2023). Employed persons by detailed occupation and age: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat11b.htm

Wang, J. (2005). Work stress as a risk factor for major depressive episode(s). Psychological Medicine, 35(6), 865–871. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291704003241

Ward, B. W., & Schiller, J. S. (2013). Prevalence of multiple chronic conditions among US adults: Estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 2010. Preventing chronic disease, 10. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd10.120203

Whiteford, H. A., Harris, M. G., McKeon, G., Baxter, A., Pennell, C., Barendregt, J. J., & Wang, J. (2013). Estimating remission from untreated major depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 43(8), 1569–1585. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291712001717

Winters, M.-F. (2020). What Is Black Fatigue, and How Can We Protect Employees from It? Greater Good Magazine. https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/what_is_black_fatigue_and_how_can_we_protect_employees_from_it

World Health Organization (WHO) (1993). Aging and Working Capacity. Geneva: World Health Organization Technical Report Series 835.

Yavorsky, J. E., Qian, Y., & Sargent, A. C. (2021). The gendered pandemic: The implications of COVID-19 for work and family. Sociology Compass, 15(6), e12881. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12881

Acknowledgements

This work is funded by RTI International University Scholars Program by which Dr. Kendra Jason was a 2022-2023 fellow.

Funding

Open access funding provided by the Carolinas Consortium.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr. Kendra Jason and Amanda Sargent contributed to the study conception and design. Data collection and analysis were performed by Kendra Jason, Amanda Sargent, and Julianne Payne. The analysis and first draft of the manuscript was written by all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics approval

IRB Approval (IRB-23–0680) was granted by the Ethics Committee of the University of North Carolina at Charlotte on March 7, 2023.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to publish

The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent for publication of the non-identifying data.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Online Questionnaire

Prescreening Questions

-

1.

What is your age in years? [numerical entry only]

-

2.

Please indicate your ethnicity (i.e. peoples’ ethnicity describes their feeling of belonging and attachment to a distinct group of a larger population that shares their ancestry, colour, language or religion)? [drop-down]

-

African

-

Black/African American

-

Caribbean

-

East Asian

-

Latino/Hispanic

-

Middle Eastern

-

Mixed

-

Native American or Alaskan Native

-

South Asian

-

White/Caucasian

-

Other (please feel free to let us know your ethnicity via email

-

White/Sephardic Jew

-

Black/British

-

White Mexican

-

Romani/Traveller

-

South East Asian

-

-

3.

What is your employment status?

-

Full-Time

-

Part-Time

-

Due to start a new job within the next month

-

Unemployed (and job seeking)

-

Not in paid work (e.g. homemaker', 'retired or disabled)

-

Other

-

-

4.

Where do you primarily work?

-

I always work from a central place of work

-

I sometimes work from a central place of work and sometimes remotely

-

I always work remotely

-

My place of work changes regularly

-

None of the above / Other

-

-

5.

Please describe your experience with the COVID-19 virus (coronavirus):

-

I have been officially diagnosed with COVID-19 (tested by a licensed medical professional), and was treated in a hospital.

-

I have been officially diagnosed with COVID-19 (tested by a licensed medical professional), and stayed at home during my recovery.

-

I strongly suspect that I have or have had COVID-19, but have not been officially tested.

-

I have experienced some of the COVID-19 symptoms, but I believe it was another illness/physical ailment/chronic condition.

-

I have not experienced any symptoms of COVID-19.

-

I strongly suspect that I have or have had COVID-19, and have been tested, but it was a negative result.

-

Don't know / other

-

Main Survey

-

1.

Has having COVID -19 changed how you think and/or feel about your workplace? [Text entry]

-

2.

If yes—Please write a few sentences about how COVID-19 has changed how you think and/or feel about your workplace. [Text entry]

-

3.

Has having COVID-19 impacted any of the following for you (Select all that apply)? [Matrix question]

-

Future job opportunities

-

Job security

-

Advancement in your organization

-

Workplace relationships

-

Kinds of assignments you receive

-

Peoples’ perceptions of you at work

-

-

4.

Please write a few sentences about how COVID-19 has impacted any of the choices you selected above [in question 3] [Text entry]

-

5.

Are there any equipment and/or practices in place at your workplace that make you feel more protected from COVID-19 exposure? [Text entry]

-

6.

If yes, Please write a few sentences about what equipment and/or practices make you feel more protected from COVID-19 exposure. [Text entry]

-

7.

What workplace supports are most meaningful to you after having COVID-19? (These can be supports you currently have or wish you had) [Text entry]

-

8.

Select any chronic illnesses you have been diagnosed with below

-

high blood pressure

-

cancer

-

lung disease

-

heart disease/condition

-

stroke

-

Diabetes

-

Arthritis

-

Depression

-

Anxiety

-

Other (please type below) [Text entry]

-

-

9.

Have your chronic illness(es) been worse, better, or the same since you had COVID-19? Please explain why you feel this way. [Text entry]

-

10.

Have your chronic illness(es) impacted any of the following for you (Select all that apply)? [Matrix question]

-

Future job opportunities

-

Job security

-

Advancement in your organization

-

Workplace relationships

-

Kinds of assignments you receive

-

Peoples’ perceptions of you at work

-

-

11.

Please write a few sentences about how your chronic illness(es) has impacted any of the choices you selected above? [in question 8] [Text entry]

-

12.

In what ways are your direct supervisors supportive (or unsupportive) of you in managing your health at work? [Text entry]

-

13.

In what ways are your coworkers (not including supervisors) supportive (or unsupportive)? [Text entry]

-

14.

What workplace challenges do you face that get in the way of your optimum well-being at work? [Text entry]

-

15.

What workplace challenges do you face that get in the way of your optimum job success? [Text entry]

-

16.

Do you think your age and/or race impact your experiences at work? [Text entry]

-

17.

If yes, please write a few sentences about how your age and/or race impact your experiences at work. [Text entry]

-

18.

If you have any other comments or relevant experiences to share that would help us better understand chronic illness or COVID-19 supports in your workplace, and/or how you manage your health at work, please describe in a few sentences below. [Text entry

-

19.

How long have you been at your current job?

-

Less than 6 months (started after November 2022)

-

Between 6 months and 1 year (started between March 2022- October 2022)

-

Between 1–3 years (started January 2020-February 2023)

-

Between 3–5 years (started between March 2018 -March 2023)

-

More than 5 years ago (started before March 2018)

-

-

20.

How would you best describe your role in your current job?

-

Entry level

-

Intermediate level (i.e., higher technical work but no supervisory requirements)

-

Management

-

-

21.

Which type of work do you most identify with in your current job?

-

White Collar- Jobs such as managerial, professional/technical, sales, clerical, health services, or personal services professions

-

Blue Collar- Jobs that require physical rigor/manual labor or industrial professions

-

-

22.

Which occupational group do you most identify with in your current job?

-

Architecture and Engineering

-

Arts and Design

-

Building and Grounds Cleaning

-

Business and Financial

-

Community and Social Service

-

Computer and Information Technology

-

Construction and Extraction

-

Education, Training, and Library

-

Entertainment and Sports

-

Farming, Fishing, and Forestry

-

Food Preparation and Serving

-

Healthcare

-

Installation, Maintenance, and Repair

-

Legal

-

Life, Physical, and Social Science

-

Management

-

Math

-

Media and Communication

-

Military

-

Office and Administrative Support

-

Personal Care and Service

-

Production

-

Protective Service

-

Sales

-

Transportation and Material Moving

-

Demographic Questions

-

1.

Are you currently employed in the United States of America?

-

Yes

-

No

-

-

2.

How many times have you had COVID-19?

-

Once

-

Twice

-

Three times

-

More than three times

-

Please type your age below.

-

-

3.

Which of the following best describes your gender identity?

-

Woman

-

Man

-

Non-Binary

-

Transgender

-

I would prefer to write my own answer:

-

I prefer not to answer

-

Which racial group best describes your racial identity (Select all that apply)?

-

Hispanic/Latina/o/Latinx/Latine American

-

Black/African American

-

White/Caucasian American

-

Another race not listed above (please type below) [Text entry]

-

-

4.

Which of these options best describes your highest level of education?

-

Some high school, did not graduate

-

High school diploma or equivalency (e.g., GED)

-

Some college or trade school, did not graduate

-

Trades school diploma/apprenticeship certificate

-

Undergraduate degree

-

Some graduate education, did not graduate

-

Graduate/Professional degree or higher (e.g., Master’s, PhD, JD)

-

-

5.

What is your relationship status?

-

Single

-

Partnered, cohabitating

-

Partnered, living separately

-

Divorced/widowed

-

Married

-

I prefer not to answer

-

-

6.

What is your current country of residence?

-

United States

-

A different country (please type below) [Text entry]

-

-

7.