Abstract

The aims of the present study are formulated to test theoretical assumptions of the incivility spiral presented by Andersson and Pearson (1999). The first aim is to investigate possible longitudinal outcomes of witnessed workplace incivility, in the form of instigated incivility and well-being. An additional aim is to explore whether witnessed workplace incivility is indirectly related to instigated incivility or well-being over time, via lower levels of perceived organizational justice. Lastly, we aim to explore if control, social support (from coworkers and supervisors), and job embeddedness moderate the relationship between witnessed and instigated incivility over time. An online questionnaire was distributed to a panel of Swedish engineers at three time points over one year with about six months between waves. Longitudinal data were provided by 341 respondents. Results from longitudinal structural equation panel models showed that witnessed workplace incivility, over time, predicted subsequent higher levels of instigated incivility but not lower levels of well-being. In addition, witnessed incivility predicted lower levels of perceived organizational justice over time but perceived organizational justice did not mediate the relationship between witnessed and instigated incivility or well-being. Finally, the results showed that control, social support from supervisors (but not coworkers), and job embeddedness partly moderated the relationship between witnessed and instigated incivility over time. The relationship between witnessed and instigated incivility between time 1 and time 2 was stronger when levels of control, support and job embeddedness were high. However, job embeddedness was the only robust moderator of the relationship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Workplace incivility has been described as a pervasive problem in organizations (Andersson and Pearson 1999). Incivility is defined as “low intensity deviant behavior, with ambiguous intent to harm the target” (Andersson and Pearson 1999, p. 457), and research has shown that it is a common workplace stressor associated with detrimental outcomes (for a recent review, see Vasconcelos 2020). Studies have reported that as many as 99% of employees have witnessed incivility in the workplace (Porath and Pearson 2010), where 10% reported witnessing it on a daily basis (Pearson and Porath 2005). In a recent Swedish study, 75% reported having witnessed incivility from coworkers, and 58% had witnessed incivility from superviors at some point during the past year (Torkelson et al. 2016). Previous research has also suggested that workplace incivility can spread like a virus in the workplace, contaminating the behavior of others (Foulk et al. 2016). This indicates that incivility is a ubiquitous work environment issue, and that the adverse consequences of incivility can be substantial.

Considering the negative impact of incivility, it is important to explore how, when, and why it spreads in the workplace. In their seminal publication on workplace incivility, Andersson and Pearson (1999) suggested that incivility can spread through reciprocal exchanges between coworkers, such as retaliating or responding in kind to the incivility of others. But they also suggested that bystanders merely observing uncivil exchanges subsequently could mirror the behavior of the instigator in a type of crossover effect, and instigate incivility towards others, as norms for civility are eroded in the workplace (Andersson and Pearson 1999). In this way, it has been hypothesized that incivility can spread in the workplace over time, where an uncivil culture may develop as rude behaviors permeate the organization (Leiter 2019). However, the proposition that incivility can spread to bystanders over time has not yet been explored empirically. Despite the large increase of research on workplace incivility over the past two decades, relatively few studies have focused on bystanders that witness incivility in the workplace (Schilpzand et al. 2016). In the present study we approach the question of whether there is a crossover effect, by investigating whether witnessed incivility is related to instigated incivility over time. We define a crossover effect as when deviant behavior is transmitted from one person (the instigator) to another (the bystander) (Ming et al. 2020). This is operationally defined as the relationship between witnessed and instigated incivility over time. Specifically, it is important to investigate crossover effects longitudinally, as this provides initial information about whether witnessed incivility impacts subsequent behavior, or if the behavioral effect on the observer dissipates over time.

In addition, in order to understand why and under what circumstances incivility spreads in the workplace, it is important to explore mediators and moderators of the spreading process. Studies on mediators and moderators of the spreading process have been scarce (Schilpzand et al. 2016). In their model, however, Andersson and Pearson (1999) proposed that interactional justice could be an important mechanism. They argued that perceptions of injustice will increase after an uncivil incident, which could result in a desire to reciprocate. From the bystander perspective, they proposed that as individuals became aware of increased incivility occurring in the workplace, distrust will rise, and that this will give way for even more uncivil conduct (Andersson and Pearson 1999). As trust and perceived organizational justice are strongly correlated (Mittal et al. 2017), it is possible that perception of justice could be a mechanism in the relationship between witnessed and instigated incivility, although this remains to be tested empirically. In the present study, we address the question whether witnessed incivility leads to reduced levels of perceived justice over time, and whether this over time is followed by an increase in instigated incivility. Exploring these relationships provides a theoretical contribution, as this tests two central assumptions of Andersson and Pearson’s model, that witnessed incivility can spread to bystanders’ behavior over time, and that perceived justice is a mechanism in this relationship. This would provide additional insight into the utility of Andersson and Pearson’s (1999) model, and whether justice is an important factor in understanding why bystanders engage in incivility.

As both vicarious incivility and perceived injustice have been linked to reduced levels of well-being (Ford and Huang 2014; Lim et al. 2008), we also investigate whether witnessed incivility is directly or indirectly related to lower levels of well-being over time via low levels of perceived organizational justice. The focus in the present study is on psychological well-being, which comprises components such as positive mood, interest and energy (Bech et al. 2003), as vicarious experiences of incivility previously have been directly linked to lower levels of psychological well-being (Lim et al. 2008). By exploring the possible long-term effect of witnessed incivility on well-being, we contribute theoretically by testing the theorized assumption that incivility is detrimental to well-being over longer periods of time because of chronic exposure to a low-intensity stressor (Cortina et al. 2001). Exploring long term consequences of witnessed incivility is an important step in understanding the extent of harm that vicarious incivility may, or may not, cause over time. In other words, this could provide information about if employees recover from such strain, or if it has a more lasting impact.

Additionally, the present study aims to make a methodological contribution. Few studies have yet investigated boundary conditions of the relationship between witnessed and instigated incivility. Although two cross-sectional studies have shown that psychosocial work factors such as control, social support and job embeddedness enhance the relationship between witnessed and instigated incivility (Holm et al. 2015, 2019), indicating that a culture of incivility has been created in the organization, the contribution of these factors has not yet been investigated over longer time periods. By investigating these moderator effects over time, it is possible to explore the robustness of how these contextual factors impact the spread of workplace incivility, and if they constitute potential risk factors in the development of an uncivil culture. Replicating such observed cross-sectional interactions over time would provide a methodological development, as well as a contribution of knowledge about how incivility interacts with perceived psychosocial factors over time.

Over the years, longitudinal work on workplace incivility has frequently been requested (Cortina et al. 2017; Lim et al. 2008; Lim and Lee 2011; Loi et al. 2015; Martin and Hine 2005), and it has been argued that longer time frames may be suitable, as it can take time to recognize a pattern of incivility in the workplace (Cortina et al. 2017). Longer time frames are also necessary to test Andersson and Pearson’s proposition that workplace incivility spreads over time. Consequently, a time lag of six months between waves was chosen in the present study, as it may take time for norms to erode and incivility to spread in the workplace (i.e., a ‘pattern of incivility’ to develop). Although the relationship between witnessed and instigated incivility has been observed cross-sectionally (Holm et al. 2015, 2019), there is still no knowledge about how persistent this effect may be over a longer time, which warrants a longer window of exploration. Similarly, it could take time for change to occur in perceptions of justice and well-being, that are relatively stable phenomena (Braun et al. 2017; Silva and Caetano 2014). In relation to well-being, it may take time for strain to accumulate, which could result in more long-lasting effects than has been observed in studies with shorter time frames (Matthews and Ritter 2019). For the relationships investigated in the present study, a time frame of six months may therefore be reasonable in order to observe potential long-term consequences of witnessed incivility. Currently, little is known about the long-term effects of incivility on bystanders’ behavior and well-being. The present study aims to address this gap by investigating longitudinal outcomes of witnessed incivility over a one year time period, as well as a possible mediator (perceived organizational justice) and moderators (control, social support and job embeddedness) of the relationships.

One way of understanding why witnessed incivility spreads to observers is via social learning theory (Bandura 1977). Social learning theory builds on the premise that individuals use social information around them as determinants of their own behavior (Bandura 1977). Individuals learn how to behave by observing how others around them behave. In the case of workplace incivility, witnessed incivility may be a social cue that triggers the observer to also engage in incivility. Individuals who witness rude conduct at work may imitate the behavior and respond in kind, contributing to an erosion of norms and an uncivil culture (Andersson and Pearson 1999; Leiter 2019). Such changes in behavior would subsequently take time to develop. Consistent with Andersson and Pearson’s (1999) model, witnessed incivility has been related to increased levels of instigated incivility in a few studies (Holm et al. 2015, 2019; Torkelson et al. 2016). Reich and Hershcovis (2015) also found that witnesses to incivility had a higher tendency to punish instigators. Overall, studies on outcomes of witnessed incivility have been scarce (Schilpzand et al. 2016), and the long-term persistence of how observed incivility spreads, and possible emergence of an uncivil culture, has not yet been investigated. Based on Andersson and Pearson’s (1999) model, we hypothesize that:

-

H1:

Witnessed workplace incivility is directly positively related to instigated incivility at a subsequent time point (i.e. from t1 to t2, and from t2 to t3).

Moreover, workplace incivility has been conceptualized as a stressor that despite its low intensity is taxing over time (Cortina et al. 2001). Dormann and Zapf (2004) specified that there is a class of social job stressors that can cause psychological or physical strain. These include conflicts with coworkers, poor group climate, and unfair or unjust treatment (Choi, Kim, Lee and Lee 2014). If the effect of stressors accumulate over time (Zapf et al. 1996), witnessing incivility may be straining to the individual which subsequently could impact their psychological well-being. Similarly as with the development of an uncivil culture, it may take time for consequences of well-being to develop. In line with the stressor-strain framework, vicarious experiences of incivility, such as reports of incivility at the workgroup level, have been shown to be predictive of lower levels of health (Lim et al. 2008). Similarly, witnessing bullying in the workplace has been associated with detriments in well-being six months later for observers (Sprigg et al. 2019). This suggests that witnessing mistreatment at work is stressful, but few studies have focused on health-related outcomes of a low intensity stressor such as witnessed incivility. Cortina et al. (2001) argued that minor stressors such as incivility can be detrimental to well-being when repeated over long time-spans. It is therefore possible that witnessed incivility is negatively related to psychological well-being over time. We hypothesize:

-

H2:

Witnessed workplace incivility is directly negatively related to psychological well-being at a subsequent time point (i.e. from t1 to t2, and from t2 to t3).

Andersson and Pearson (1999) described that workplace incivility can shape perceptions of interactional injustice. Further, they argued that the perceived injustice would lead to a desire to reciprocate the behavior that was perceived as unfair. This indicates a process of mediation, where low levels of perceived justice indirectly link the occurrence of workplace incivility with retaliation, e.g. instigated incivility. Their proposition aligns with deontic theory, which posits that individuals expect each other to uphold standards of fairness and to react negatively when moral norms of interpersonal behavior are violated (Folger 2001). In the case of workplace incivility, perceived injustice could erode norms for respect in the workplace, increasing the risk of uncivil behaviors being instigated. In contrast to interactional injustice described in Andersson and Pearson’s (1999) model, Folger (2001) highlights the importance of overall justice perceptions. For instance, Skarlicki and Folger (1997) found that an interaction of low levels of procedural, distributive and interactional justice predicted retaliatory behaviors directed at the organization or its members above and beyond justice at the facet level. Similarly, Ambrose and Schminke (2009) advocated focusing on overall justice perceptions as overall justice perceptions predict behavior. Overall justice perceptions could therefore be a more central mechanism than interactional justice in how incivility spreads to observers.

A few studies have explored the relationship between incivility and the different facets of justice defined by Colquitt and Greenberg (2003). For instance, Griffin (2010) found that experienced organizational-level incivility negatively predicted interactional justice climate, which refers to perceptions of fair interpersonal treatment. Blau and Andersson (2005) found that distributive (perceived unfair distribution of resources), but not procedural (perceived unfairness of organizational processes) and interactional injustice, was related to increased instigated incivility over time. However, Sayers et al. (2011), found both procedural and interactional justice to be negatively correlated with instigated incivility. Although these studies report on facets of justice, they may indicate a link between workplace incivility and overall justice perceptions. For instance, Mohammad et al. (2019) found that perceptions of justice are mediated via overall justice, which suggests it to be an overarching mechanism. Similarly, Ambrose and Schminke (2009) have stated that individuals make holistic judgments of justice. In light of this, the relationship between overall perceived organizational justice and instigated incivility may be more informative to explore, rather than the inconclusive facet-level correlations found in previous studies. From a bystander perspective, Porath et al. (2010) found that customers who witnessed a manager engage in incivility towards a subordinate reported higher levels of anger, and desire for revenge towards the manager, which was mediated by their perceptions of deontic injustice.

Another interpretation of deontic theory is that lack of justice constitutes a stressor. Likewise as incivility, unjust treatment and perceived organizational injustice have been conceptualized as stressors which cause strain over time (Choi et al. 2014; Ford and Huang 2014). Accordingly, low levels of organizational justice have consistently been linked to lower well-being in several studies (for a review, see Ford and Huang 2014). Perceived injustice has also been found to mediate the relationship between witnessed incivility towards women and observer’s occupational well-being (Miner and Cortina 2016). In light of this, we hypothesize:

-

H3a:

There is an indirect relationship between witnessed incivility at time 1 and instigated incivility at time 3 via low levels of perceived organizational justice at time 2.

-

H3b:

There is an indirect relationship between witnessed incivility at time 1 and well-being at time 3 via low levels of perceived organizational justice at time 2.

Currently, few studies have explored boundary conditions between witnessed and instigated workplace incivility. However, Holm et al. (2019) found that control and social support, from coworkers and supervisors, as well as job embeddedness interacted with witnessed incivility, in predicting instigated incivility. The associations between the incivility variables were stronger when levels of the moderator were high. This may seem counterintuitive, as control and social support usually are conceptualized as job resources, which have a buffering impact on strain-related outcomes of stressors (Bakker and Demerouti 2017; Karasek and Theorell 1990). However, a similar result as found by Holm et al. has been found in a study on job stressors and counterproductive workplace behaviors (CWB), where high levels of autonomy were shown to enhance the association between the stressors and CWBs (Fox et al. 2001). Theoretically, Holm et al. (2019) argued that a negative spiral can be reinforced vicariously if an instigator appears to be rewarded for negative behaviors. For instance, witnessing coworkers engage in CWB without punishment can signal to the observer that CWBs are tolerated and accepted in the workplace (Ju et al. 2019). If the instigator in addition is an important role model, this may lead to even more incivility from bystanders. Consequently, when bystanders conform to perceived behavioral norms, they could be rewarded with job resources, in line with a negative spiral.

Holm et al. (2019) also suggested that social support as a job resource could be a reward for conforming to uncivil workplace norms, further reinforcing instigation of negative behavior. Similarly, Ramsay et al. (2011) have argued that groups with aggressive social norms are more likely to condone aggressive behaviors within the group, and that deviating from such group rules could lead to victimization for the deviator. Consequently, it is possible that those who conform also have been more socially included, which could explain why social support enhances the association between witnessed and instigated incivility. Regarding job embeddedness, Holm et al. (2019) argued that individuals to a higher degree may adjust to negative behavior they witness by instigating relatively more incivility towards others, if they are highly embedded in the workplace, because they are prone to conform to workplace norms and more susceptible to the influence of role models. The presence of these moderator effects could therefore be due to an uncivil culture in the organization, in line with Andersson and Pearson’s (1999) model. However, these moderation effect have only been demonstrated cross-sectionally. It is necessary to extend these predictions within a longitudinal framework in order to explore the robustness of the contextual factors influencing the relationship between witnessed and instigated incivility. Thus, we investigate factors that may enhance the spread of incivility over time. Specifically, we explore whether the moderation effects that emerged in the cross-sectional studies replicate when explored over time. When testing longitudinal moderation over three waves, the recommendation is to test the moderation effect at each measurement point (Little 2013). Methodologically, finding the effect over all waves is considered a replication of the effect over time, which would signal a very robust moderation effect (Little 2013). Theoretically, this also maps well onto the possible presence of an uncivil culture, where there would be no reason to suspect that the moderating effects would dissipate from one measurement point to the next. Rather, it should continue to demonstrate the same pattern of relationships consistently. We therefore hypothesize:

-

H4:

Control moderates the relationship between witnessed incivility and instigated incivility over time (from t1 to t2, and from t2 to t3), in the way that the relationship is stronger when levels of control are higher.

-

H5:

Social support (from coworker and supervisor) moderates the relationship between witnessed incivility and instigated incivility over time (from t1 to t2, and from t2 to t3), in the way that the relationship is stronger when levels of social support are higher.

-

H6:

Job embeddedness moderates the relationship between witnessed incivility and instigated incivility over time (from t1 to t2, and from t2 to t3), in the way that the relationship is stronger when levels of job embeddedness are higher.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Over three waves, 1005 individuals (622 males, 380 females, 3 undisclosed) participated in the study. The participants were members of a worker union organizing engineers in Sweden. Their mean age was 45.0 (SD = 10.1) years. They had on average been working in their current workplace for 8.6 (SD = 8.6) years. The engineers were working within information technology, product development, construction and logistics, maintenance and operations, research and development, quality assessment and evaluations, administration, management and project management, as well as business development, sales, and risk management, amongst others. An online survey was sent to 5073 individuals at time 1, 4878 at time 2 and 4630 at time 3, of which 517 responded at time 1 (10.2%), 498 at time 2 (10.2%) and 490 at time 3 (10.6%). A total of 341 individuals (206 males, 134 females, 1 undisclosed) had complete data for at least two of the measurement occasions, whereas 664 individuals merely responded to one survey at either of the three occasions. The overall response rate was 19.8%.

The survey was administered at three occasions. The union randomly sampled a pool of about 5000 of their members. The survey was then administered via e-mail to everyone in the pool at each respective occasion. Time gaps between measurement occasions were roughly 6 months. Responses were matched over time via a unique identification code for each participant. The survey had a full-panel design, meaning that all study variables were measured at all three occasions.

Materials

Demographic Measures

Questions about gender, age, supervisor position, length of employment (tenure), and occupational category were included in the survey. One question at time 2 and 3 assessed whether the respondent was working in the same workplace since the previous survey.

Witnessed Workplace Incivility

Witnessed incivility was measured with a Swedish translation (Schad et al. 2014) of the Workplace Incivility Scale (WIS; Cortina et al. 2001). The scale consists of 7 items. Stems were modified to reflect observed rather than experienced incidents. Participants were asked how often they had witnessed the seven behaviors the last month, with response options ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (most of the time). A sample item was: “during the last month in your workplace, have you witnessed a supervisor or coworker: make demeaning or derogatory remarks about others?” Chronbach’s alpha (α) = .91 (t1), .92 (t2), and .92 (t3).

Instigated Workplace Incivility

To measure instigated incivility, Blau and Andersson’s (2005) modified version of the WIS was used. This scale reflects participants’ own behavior over the last month, for the same seven items. The response options for this scale ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (most of the time). A sample item was: “during the last month in your workplace, how often have you: ignored or excluded someone from professional camaraderie?” α = .80, .68, .78.

Perceived Organizational Justice

To measure perceptions of organizational justice the 4-item justice scale (“Are conflicts resolved in a fair way?”, “Are employees appreciated when they have done a good job?”, “Are all suggestions from employees treated seriously by the management?”, “Is the work distributed fairly?”) of the second edition of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ II; Pejtersen et al. 2010) was used. We complemented the scale with two items (“Employees are treated with respect”, “Employees are treated fairly”) from Donovan et al. 1998), and three items (“Overall, I’m treated fairly by my organization”, “In general, I can count on this organization to be fair”, “In general, the treatment I receive around here is fair”) from Ambrose and Schminke (2009). These items were added because the COPSOQ justice measure primarily focus on the role of management. With these additions, the 9-item measure was designed to reflect overall justice perceptions, rather than the specific justice dimensions. The scale was pilot tested on a convenience sample of 120 participants, where it showed high reliability (α = .96) and correlated significantly negatively with workplace incivility, and significantly positively with the COPSOQ-measures and well-being. Response alternatives ranged from 1 (to a very small extent) to 5 (to a very large extent). α = .94, .94, and .94.

Control

Control was measured with four items from COPSOQ II. Response alternatives ranged from 1 (never/almost never) to 5 (always). A sample item was: “can you influence the amount of work assigned to you?” α was .83, .80, and .80.

Social Support from Coworkers

Three items from COPSOQ II assessed social support from coworkers, with response options ranging from 1 (never/almost never) to 5 (always). A sample item was: “how often do you get help and support from your colleagues?” α = .75, .68, .69.

Social Support from Supervisors

Three items from COPSOQ II measured support from supervisors. Response alternatives ranged from 1 (never/almost never) to 5 (always). A sample item was: “how often is your nearest supervisor willing to listen to your problems at work?” α = .85, .84, and .84. A Swedish translation (Berthelsen et al. 2014) was used for all COPSOQ-scales.

Job Embeddedness

A Swedish translation (Holm et al. 2019) of Crossley et al. (2007) job embeddedness-scale was used. It consisted of 7 items, with response options ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A sample item was: “it would be difficult for me to leave this organization”. α = .88, .91, and .89.

Well-Being

Well-being was measured with five items from the WHO-5 well-being index, a measure of psychological well-being (Bech et al. 2003). Response options ranged from 1 (never) to 6 (all of the time). A sample item was: “Over the last two weeks: I have felt active and vigorous”. α = .87, .86, and .88.

Ethical Considerations

A consent form was presented at all three measurement occasions. The consent form informed participants that participation was voluntary, that their responses would be treated confidentially, and that raw data would not be shared with the union. The study protocol was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Board (dnr 2016/926).

Data Analysis

The analyses were conducted using R v. 3.6.2. The lavaan-package (Rosseel 2012) was used to estimate all models in R. First, as measures were gathered at three time points, measurement (temporal) invariance of the measures was assessed to ascertain that the factor structure did not differ as a function of time (van de Schoot et al. 2012). Next, two autoregressive latent path models were estimated to test hypotheses 1–3 concerning direct and indirect effects, one for each dependent variable. Items for the scales witnessed incivility, instigated incivility, perceived organizational justice, and well-being were used as indicators of each latent variable. Cross-lagged item-level residuals were free to covary across measurement occasions in the models in line with recommendations for longitudinal panel models (Cole and Maxwell 2003; Little 2013). The maximum likelihood (ML) estimator was used in model estimation, as this allows for the use of the full information of the data set to estimate missing data points in the model via full information maximum likelihood (FIML)-estimation (Collins et al. 2001). Thus, the model can use all information in the data set of 1005 individuals for assessing the within-time covariances, and participants only needed to provide data for a minimum of two of the three time points to be included in the cross-time analyses. The models were assessed against criteria suggested in the literature, CFI > .95, RMSEA < .06, SRMR < .08, and the χ2-test of the model implied covariance matrix (Hu and Bentler 1999). In the tests of mediation, we estimated 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals for indirect effects via bootstrapping (1000 draws).

For the moderation hypotheses, we estimated models with interaction terms. To reduce analytical complexity, observed rather than latent constructs were used to test the interaction hypotheses. These models are specified in the same way as the structural equation models, but with scales rather than latent variables, including all three time points of the predictor, the moderator and the dependent variables, with autocorrelations between waves, and intercorrelations within time points. The only difference is the addition of interaction terms between the predictor and moderator within the model (one at time 1 and one at time 2). One model was assessed for each moderator, to test their influence independently. When testing moderation over three time-waves, the influence of the moderator is tested for each consecutive measurement occasion, i.e. between time 1 and 2, as well as 2 and 3. We included interaction terms between witnessed incivility and each moderator at each time point (t1witnessed incivility x t1moderator, and t2witnessed incivility x t2moderator, mean-centered) with paths predicting t2 and t3 instigated incivility respectively (Little 2013). The interaction terms are entered as saturated correlates of all other variables at all time points in the model, apart from the dependent variable it is predicting, where a direct path is specified. In such models, a significant path between the interaction term and the subsequent measure of the dependent variable indicates evidence for the presence of a longitudinal moderation effect (Little 2013).

Results

Pearson’s correlations within and between time waves, scale means and standard deviations are presented in Table 1.

To explore whether study dropout was associated with any of the study variables, we conducted a series of independent sample t-tests between those who did not answer a follow up survey (dropout group, N = 431), and those who had provided longitudinal data (retention group, N = 341) on all study variables. The dropout group was defined as participants who had only completed the time 1 survey, or only participated at time 2. Time 3 participants were not included in this group as they, rather than dropped out, attempted to join at the last time point. Significant differences were found in participants’ age at both t1 and t2, where those who dropped out on average were younger (M = 43.41t1 t(491) = 2.01, p = .045, and M = 43.71t2, t(379.24) = 2.11, p = .035, compared to M = 45.2t1, and M = 45.78t2) than those who completed follow up surveys. Participants who only completed the t2-survey also had significantly lower tenure (M = 7.29 vs M = 8.82 years, t(472) = 2.06, p = .040) than those who provided longitudinal data. As for the focal variables, participants only differed on social support from coworkers at time 2, where dropouts reported higher levels of support (M = 3.78, compared to M = 3.61, t(390.93) = −2.65, p = .008). There were no other significant differences between the retention and dropout group.

Tests of Temporal Invariance of the Measures over the Three Time Points

We assessed the measures’ temporal invariance over the three time points. We estimated a series of nested models, starting with a baseline-model testing for configural invariance, that we compared the following models to. The items of a construct at t1, t2 and t3 were simultaneously loaded on to a latent factor for each measurement wave in a confirmatory factor analysis-model. If the items from each measurement occasion load similarly onto their corresponding latent variable, and the model displays satisfying fit statistics, the model is considered to have configural invariance. In the next step, all factor loadings are fixed to be equivalent over measurement occasions to test metric invariance. Item 1 from the scale is fixed to load equivalently to item 1 at time 2 onto their corresponding latent variable, and so on. This is also referred to as weak invariance (Little 2013), and is evaluated based on CFI, that should not differ more than .01 from the configural model. If weak invariance is achieved, strong (scalar) invariance can be tested by also fixing the intercepts of items to be equal across time. Again, this is evaluated based on CFI, where a shift > .01 is considered failure of the invariance test.

Table 2 summarizes the test of invariance for all study variables. Most CFI-values did not reach > .95, but were > .90, which is often considered acceptable (Lai and Green 2016), particularly in combination with other fit measures within the acceptable range. All factor loadings for scale items were significant (p < .001) in each measurement model and ranged from .36 to .92. Items from the composed justice-measure loaded in the range of .68 to .92 on the overall justice dimension. As demonstrated in Table 2, all study variables achieved strong invariance, and were considered temporally invariant. One exception was the initial fit of the instigated incivility measure. The configural model for instigated incivility had a slightly lower CFI-value than the usual threshold recommendations χ2 (165) = 469.0, p < .001, CFI = .897, RMSEA = .043, SRMR = .066. However, when adding one error correlation between two item residuals at time 2, the model fit became acceptable. This error correlation was included in all subsequent tests, as recommended by Little (2013).

Hypotheses Testing

Direct and Indirect Relationships

Before exploring change over time, we removed individuals who reported to have changed jobs since the previous measurement occasion (N = 23), to not bias the models with erroneous crossover effects (i.e. justice perceptions of a new workplace influenced by witnessed incivility at a prior workplace). To test the hypotheses about direct and indirect effects (via perceived justice) of witnessed incivility on instigated incivility and well-being, we estimated two longitudinal structural equation models. As the correlation between instigated incivility and well-being was relatively low (r = −.29t1, −.24t2 and -.22t3, p < .001) and the models were complex, we chose to estimate two separate models. In the first model, instigated incivility was the dependent variable. In the second model, well-being was the dependent variable.

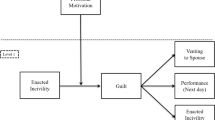

The first model had a good fit to the data χ2 (2187) = 5199.9, p < .001, CFI = .88, RMSEA = .037, SRMR = .075. The fit statistics were in an acceptable range, but the CFI was slightly low. This is however a common issue in models containing many items, which tends to reduce CFI (Cheung and Rensvold 2002). The model is displayed in Fig. 1. The latent factors demonstrated strong within-wave correlations. Apart from the strong and significant autoregressive paths between measurement waves, there was also a significant path, β = .27, p = .003, from witnessed incivility at t1 to instigated incivility at t2. The path from witnessed incivility at t2 to instigated incivility at t3 was however not significant, β = −.02, p = .83. Hypothesis 1, that witnessed incivility was directly related to instigated incivility over time, was therefore partly supported. The model also showed a small negative significant path, β = −.15, p = .003, from witnessed incivility at time 1, to perceived justice at time 2, and from witnessed incivility at time 2 to perceived justice at time 3, β = −.20, p < .001. Perceived justice at time 2 also negatively predicted instigated incivility at time 3, −.20, p = .004, consistent with the proposed mediation hypothesis. To explore possible mediation, the indirect effect from witnessed incivility t1 to instigated incivility at t3 via perceived justice t2 was calculated. The indirect effect was significant, and the confidence interval for the unstandardized coefficient did not range over zero, β = .03, p = .038, B = .01, [.001–.029]. However, this effect was not significant when 1000 bootstraps were drawn to estimate 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals for the indirect effect, β = .03, p = .127, B = .01, [−.001–.027]. Hypothesis 3a concerning mediation was therefore not supported.

Longitudinal panel model of the study relationships concerning hypotheses 1 and 3a. WI = Witnessed Incivility; PJ = Perceived Justice; II = Instigated Incivility. All coefficients are standardized. Indicators of the latent variables are not depicted in the figure. * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001

In the next model, well-being was the dependent variable. The model fit the data well, χ2 (1807) = 3740.23, p < .001, CFI = .92, RMSEA = .033, SRMR = .071. The model is displayed in Fig. 2. Besides significant inter-wave correlations and autoregressive paths, the only significant paths were from witnessed incivility at t1 to perceived justice at t2, β = −.15, p = .002, and from witnessed incivility at t2 to perceived justice at t3, β = −.19, p = .001. There were no significant paths from either witnessed incivility or perceived justice to well-being. Hypotheses 2 concerning direct effects of witnessed incivility on well-being, and 3b concerning indirect effects via perceived justice, were therefore not supported. As the incivility variables are highly right skewed, we also tested both models with robust maximum likelihood. The MLR-estimator has been shown to be a consistent estimator, comparable to weighted least squares, with means and variance-adjusted estimation (WLSMV) for ordinal variables (Li 2016). The robust models demonstrated the same pattern of relationships as the original models. The only difference was that their fit indices were slightly better than the ML-models, and p-values for the significant direct effects at all time points, and some within-time covariances, were slightly higher, but still significant at the p < .01, and p < .05-level.

Moderation Analyses

Next, we tested hypotheses concerning moderation by control (H4), social support from coworkers and supervisors (H5), and job embeddedness (H6), of the relationship between witnessed and instigated incivility. Longitudinal manifest panel models revealed that there were significant interaction terms for control, social support from supervisors and job embeddedness between time 1 and time 2, but not between time 2 and 3. Social support from coworkers did not significantly interact with witnessed incivility in predicting instigated incivility at any of the time points. H4 concerning moderation by control, H5 concerning social support (from coworkers and supervisors), and H6 concerning job embeddedness were therefore only partly supported. Table 3 shows autoregressive paths from instigated incivility, standardized and unstandardized beta coefficients of predictors and moderators, as well as standard errors, and p-values for each model, predicting instigated incivility at time 2 and time 3 respectively. The interaction terms indicate that the relationship between witnessed incivility at t1 and instigated incivility at t2 was slightly stronger when levels of control, support and embeddedness at t1 were higher. We further plotted the three significant interactions, see Figs. 3, 4 and 5. The results of simple slope analyses for the significant interactions are presented in Table 4. Participants who reported higher levels of witnessed incivility and higher levels of control, social support from supervisors and job embeddedness, also on average reported relatively higher levels of instigated incivility towards others six months later, but this effect was not observed after an additional six-month period. When using robust estimation, only the interaction between witnessed incivility and job embeddedness at time 1 remained significant. We did therefore not find robust support for hypothesis 4 concerning moderation by control, and 5 concerning moderation by social support, and partial support for hypothesis 6, concerning moderation by job embeddedness.

Discussion

To test Andersson and Pearson’s (1999) theoretical assumptions of how incivility influences bystanders, we investigated direct relationships between witnessed incivility and the two outcomes, instigated incivility and well-being. We also investigated perceived organizational justice as a potential mediator, and control, social support (from supervisors and coworkers) and job embeddedness as potential moderators of the relationship between witnessed and instigated incivility. The results indicate that reports of witnessed incivility predict subsequent reports of slightly higher instigated incivility six months later, when controlling for baseline instigated incivility, but not lower levels of well-being. Witnessed incivility was not indirectly linked to instigated incivility or well-being over time, via lower perceptions of justice. The results also demonstrate that control, social support from supervisors, but not coworkers, and job embeddedness partly moderated the relationship between witnessed and instigated incivility over time. The relationships were slightly stronger when levels of control, support and embeddedness were higher.

The direct effect of witnessed incivility at t1 on subsequent instigated incivility at t2 can be interpreted in line with Andersson and Pearson’s (1999) suggestion that witnessed incivility can affect bystanders’ behavior as norms are eroded over time. This provides initial support for a crossover effect, where witnesses to incivility subsequently engage in uncivil behaviors. However, the main effect was not observed from t2 to t3, which suggests that there is not consistent support for this direct relationship over time, at least when considering time lags of six months. This is not consistent with continuous norm erosion and detriment of a workplace culture as suggested in previous studies (Andersson and Pearson 1999; Leiter 2019). It is possible that other unmeasured factors influence the presence of a relationship between witnessed and instigated incivility over time, resulting in an effect between t1 and t2, but not between t2 and t3. Such factors could possibly be work environment initiatives, resistance to an uncivil culture, individual coping processes, or other covariates leading to buffering effects. These could potentially explain the different effects of witnessed incivility on instigated incivility over time. Although Andersson and Pearson (1999) highlighted justice as an important mechanism in explaining increased instigated incivility for those previously exposed to incivility, the results did not support such an indirect effect in the present study, in contrast to the process described in deontic theory. It is possible that witnessed incivility affects facets of justice (such as, distributional, procedural, interactional) differently, in line with the conflicting facet-level evidence previously found in relation to incivility (Blau and Andersson 2005; Sayers et al. 2011), and that the overall justice dimension therefore is not a sufficiently precise mechanism in the relationship between witnessed incivility and either instigated incivility or well-being.

In contrast to the strain-hypothesis (Cortina et al. 2001), there was no evidence of witnessed incivility predicting lower levels of psychological well-being over time. Effects have only previously been demonstrated in cross-sectional studies (Lim et al. 2008; Holm et al. 2015). In line with this, there were cross-sectional correlations between witnessed incivility and well-being at t1 and t2, but no cross-lagged effects. These results may perhaps be interpreted in line with stress adaption theory as suggested by Matthews and Ritter (2019), which posits that individuals adapt to stressors over time. The results differ from the findings of Sprigg et al. (2019), however. Potentially because workplace bullying is a more powerful stressor. It is therefore possible that witnessing incivility has an impact on well-being in the short term, after which adaption occurs and the effect dissipates over time.

It is also possible that such an adaption process may have already occurred prior to the study, and that the three measures included in the present study therefore did not capture any long-term variability in well-being to be explained by witnessed incivility. There is always an issue of identifying the ‘starting point’ of a process in observational studies, which only can be remedied by complementary experimental designs where control of the process is stricter. However, it is not straight-forward to design an experimental study on witnessed incivility and well-being due to the potential harm of exposing people to incivility. Instead, one possibility is to implement a workplace intervention designed to reduce the overall amount of workplace incivility, and assess whether this causes increased well-being over time for both those reporting previous victimization and those reporting having been bystanders. Although such a quasi-experimental design still would be limited by external factors, it may give a stronger indication of whether there is a relationship or a null effect between witnessed incivility and well-being over time. Nevertheless, Hershcovis et al. (2017) designed an experimental vignette study to explore observer reactions to witnessed incivility. Although their study focused on behavioral outcomes of witnessed incivility and not well-being, a similar design could potentially be used to explore the impact of witnessed incivility on a well-being indicator. For instance, exploring elevated levels of distress in response to a vignette describing incivility in the workplace.

In contrast to the strain-hypothesis, and our expectations from previous studies (Ford and Huang 2014; Miner and Cortina 2016), perceived justice did not predict well-being over time in the present study. However, the cross-sectional association between justice and well-being remained moderate to strong at all time points, possibly reflecting that organizational justice perceptions are more salient for employee’s well-being in the short term, rather than over longer time periods where coping processes may have had time to occur.

We only found partial support for the interaction hypotheses. This is interesting, as the study sought to replicate cross-sectional findings on control, social support (Holm et al. 2015, 2019), and job embeddedness (Holm et al. 2019). The effects, which were quite small, were only observed at the second measurement occasion, suggesting that there is only weak support for a moderating effect over time. However, the effect sizes were comparable to those previously reported (Holm et al. 2019). Due to the relatively small size of effect, and the sample size, it is possible that the statistical power to detect significant effects across both time points was too low. Interaction effects are particularly sensitive to measurement error and consequently hard to detect (Aiken and West 1991). This could perhaps explain why there was no moderation by social support from coworkers, as the scale measuring this factor was the least reliable of the moderators.

Previous researchers have suggested that the reason why control, social support and job embeddedness may moderate such a relationship could be because job resources, in the form of control and social support, are vicarious reinforcements for conforming to normative (in this case, uncivil) behavior (Holm et al. 2019). They also argued that individuals could be embedded into a negative environment, and thereby to a higher extent conform to the environment. On the other hand, Fox et al. (2001) argued that individuals with higher levels of control may have more powerful positions, allowing them to engage in CWBs without fear of repercussions. Ju et al. (2019), expanding on this hypothesis, found that the effect of control in strengthening the relationship between abusive supervision and engaging in CWB was conditional on workgroup norms for CWB. If individuals had a higher degree of latitude to engage in CWB, and their workgroup norms also favored CWB, they were more likely to respond with CWB after having experienced abusive supervision (Ju et al. 2019). Similarly, workgroup norms can possibly explain why individuals with high levels of control, social support, and job embeddedness engage in relatively more instigated incivility over time after having witnessed incivility.

Theoretical and Methodological Contributions

The present study makes several important theoretical and methodological contributions. Specifically, the present study furthers our theoretical understanding of workplace incivility by testing and providing some support for one of the core assumptions of Andersson and Pearson’s (1999) model, that incivility spreads and influences bystanders’ behavior over time. This informs us of a long-term persistence of an effect previously only found in cross-sectional or experimental research, indicating that the effect of witnessing incivility on behavior may be more pronounced than previously known. In addition, the present study tests and finds no support for another assumption of Andersson and Pearson, that perceived injustice is a mechanism in the spreading process. This suggests that other mechanisms may be more relevant in explaining the spreading process. Another theoretical contribution is that we did not find any long-term impact on bystanders’ well-being. This advances our knowledge about the role of witnessed incivility as a stressor, as the results suggest that the theorized nature of incivility as taxing over time (Cortina et al. 2001), does not seem to extend to witnessed incidents. Lastly, the present study contributes methodologically by testing the robustness of the contextual factors influencing the relationship between witnessed and instigated incivility, extending cross-sectional findings, showing that factors such as control, social support and job embeddedness also partly can slightly enhance the spread of incivility over time. This is, to the best of our knowledge, the first study to focus explicitly on witnessed incivility over time, and its possible implications for behavior and well-being, as well as mediators and moderators involved in such models.

Practical Implications

The present study partially supported that incivility may spread to bystanders over time, even if this was not consistent over waves. This finding is important from a practical point of view, as this is the first study to demonstrate long-term effects of incivility on the bystanders’ own behavior. Consequently, there is a risk that bystanders become increasingly involved in negative workplace behavior over time due to prior vicarious exposure. Organizations would therefore need to consider not only those that are targeted by incivility, but also those who witnesses it. Interventions aimed at reducing incivility would therefore need to encompass the entire workplace or workgroup as well as address norms holistically in the workplace, rather than focusing on specific individuals that have been pointed out as involved in the process. An example of such an intervention that has been successful in previous research is the Civility, Respect and Engagement in the Workforce-program (Osatuke et al. 2009). The present study reinforces their approach of focusing on the entire work unit, rather than specific individuals.

From a practitioner perspective, the results concerning witnessed incivility and well-being are also interesting. Although there was no long-term impact of witnessed incivility on well-being, the moderate cross-sectional correlations indicated that witnessed incivility still can be straining for employees in a short perspective. Thus, it is important to be cognizant of the secondary impact incivility may have beyond targets, with potential to affect witnesses’ well-being as well, at least over shorter time frames. Additionally, the present study also showed that perceptions of justice were negatively impacted over time. Consequently, organizations should attempt to reduce the risk of incivility in the workplace, in order to avoid that employees feel unfairly treated, as well as negative health effects for both targets and witnesses (Lim et al. 2008; Torkelson et al. 2016). Lastly, as witnessed incivility was related to increased instigation of incivility over time, organizations need to immediately address incivility when it occurs to reduce the risk of future incivility, and prevent new possible targets from suffering its consequences. Practically, some measures that could be made by organizations include HR-practices such as educational and training initiatives about interpersonal conduct and conflict management (Pearson et al. 2000). Pearson et al. (2000) also mention that organizations can swiftly issue corrective feedback to instigators, and set expectations of civil behavior through organizational policies specifying appropriate social behavior at work. For additional practical suggestions on how to address incivility in the workplace, see Pearson et al. (2000).

Limitations and Future Research

Some limitations should be noted. Considering the low response rate, the results are not generalizable to the population of Swedish engineers. However, as the association between witnessed and instigated incivility has been demonstrated in several studies of diverse samples (Holm et al. 2015, 2019), it is probable that this limitation concerns attenuation or inflation of the true effect size of the relationship due to restriction of range, rather than type I errors of false population effects. Attenuation due to range restriction has previously been found in the relationship between counterproductive workplace behaviors and justice dimensions (Greco et al. 2015). Regardless, the sample consisted of engineers. The results may therefore not be generalizable to other work sectors. Future research efforts could be made to compile data over how workplace incivility vary over sectors, in order to explore how pervasive incivility is across the labor market.

Moreover, dropouts differed systematically in terms of age, tenure and social support from coworkers, compared to those who completed several surveys. Although it is possible that dropout was influenced by unmeasured factors, it appears unlikely to have influenced the results of the study, as dropouts did not differ significantly on any of the main measures. Further, the assessments were self-reports, introducing the risk of common method bias (Podsakoff et al. 2003). For instance, common method bias could be an alternate explanation to why there were observed cross-sectional, but not longitudinal, associations between witnessed incivility, perceived organizational justice and well-being. In the case of common method bias, reports provided at the same measurement occasion could be inflated due to common method factors, thus causing the intra-wave correlations to be stronger than inter-wave correlations. However, meta-analytical evidence from Berry et al. (2012) suggests that self-reports are a valid and reliable method for assessing counterproductive workplace behaviors. Considering the similarity to workplace incivility, this possibly applies to incivility measurements as well. Lastly, a global well-being measure was used in the study. Future studies could focus on the possible impact of witnessed incivility on more specific work-related well-being factors.

Furthermore, cross-lagged path models have been criticized for not differentiating between- and within-individual variance (Hamaker et al. 2015). Instead, the random intercept cross-lagged panel model has been suggested (Hamaker et al. 2015). We attempted to estimate models with random intercepts, but this resulted in convergence issues, and unreliable parameter estimates (e.g. negative autocorrelations, standardized paths exceeding 1). We likely lacked power to estimate such models successfully. We therefore opted for our original cross-lagged panel models. However, the interpretation of these models should be cautioned by that we could not differentiate within and between-individual variance. On the other hand, as the aim of this study was to explore mediators and moderators, rather than to specifically estimate within-individual trajectories, cross-lagged path models are a viable option. Cross-lagged path models have been suggested to be preferable when the goal is to estimate covariations and/or explore mediation hypotheses (Little 2013). Nevertheless, future studies focused on individual trajectories of incivility experiences would benefit from estimating both within and between-individual effects separately.

In the present study, the interaction analyses were conducted on observed, rather than latent, variables. Currently, latent variable interaction is not available in the R-package Lavaan, which was used to estimate the models in the study. Although these analyses therefore may be limited by the influence of measurement error, this is not likely to call the validity of the observed interactions into question. Measurement error has been shown to have a relatively stronger impact on interaction effects than first-order effects, which attenuates the moderator effect (Aiken and West 1991). It is therefore more probable that the interaction effects found for the observed variables are underestimated due to measurement error, compared to interactions with latent variables, rather than vice versa. This could also possibly explain the quite small effect sizes of the observed interactions, and why they did not replicate from t2 to t3.

Although measuring overall justice perceptions has been suggested to be preferable, as justice perceptions are mediated via overall justice (Mohammad et al. 2019), future studies could explore specific justice dimensions, (distributive, procedural and interpersonal) in models of workplace incivility. Further, more research is needed on other possible moderators that may attenuate the impact of witnessed incivility on detrimental outcomes, such as coping responses (Hershcovis et al. 2018). Future studies could also explore whether meso-level factors, such as change in workgroup norms or organizational culture are predictive of incivility and/or its outcomes. Lastly, future studies could implement workplace interventions focused at reducing incivility and consecutively measure well-being indicators for those involved in the intervention, before, during and afterwards. With an instigated change process, latent growth curve models could be estimated to investigate whether individuals’ well-being trajectories follow the levels of witnessed incivility, or remain stable over time.

Conclusion

Extant research has been carried out on targets of workplace incivility over the past two decades. The bystander perspective, on the other hand, still remains far less explored. Particularly, little has been known about long-term outcomes of witnessed incivility. The present study demonstrates both short and long-term outcomes of witnessing incivility in the workplace, suggesting that incivility in part can spread to bystanders’ behavior over time. In light of this, more research is warranted on bystanders to uncivil experiences, and the consequences of incivility beyond direct targets. Extending research models to include the bystander perspective is important in order to better understand the processes of which incivility spreads in the workplace, and the additional impact incivility may have on an organization and its members beside those directly targeted. Until such efforts are made, the full ramifications of workplace incivility will be difficult to overview.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousands Oaks: SAGE.

Ambrose, M., & Schminke, M. (2009). The role of overall justice judgments in organizational justice research: A test of mediation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(2), 491–500. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013203.

Andersson, L. M., & Pearson, C. M. (1999). Tit for tat? The spiraling effect of incivility in the workplace. Academy of Management Review, 24(3), 452–471. https://doi.org/10.2307/259136.

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000056.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Bech, P., Olsen, L. R., Kjøller, M., & Rasmussen, N. K. (2003). Measuring well-being rather than absence of distress symptoms: A comparison of the SF-36 mental health subscale and the WHO-five well-being scale. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 12(2), 85–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.145.

Berry, C. M., Carpenter, N. C., & Barratt, C. L. (2012). Do other-reports of counterproductive work behavior provide an incremental contribution over self-reports? A meta-analytical comparison. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97, 613–636.

Berthelsen, H., Westerlund, H. and Søndergård Kristensen, T. (2014). Copsoq II – en uppdatering och språklig validering av den svenska versionen för kartläggning av den psykosociala arbetsmiljön [Copsoq II – An update and lingual validation of the Swedish version for mapping the psychosocial work environment]. Stockholm: Stress Research Institute.

Blau, G., & Andersson, L. (2005). Testing a measure of instigated workplace incivility. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 78, 595–614. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317905x26822.

Braun, T., Schmukle, S. C., & Kunzmann, U. (2017). Stability and change in subjective well-being: The role of performance-based and self-rated cognition. Psychology and Aging, 32(2), 105–117. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000153.

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 233–255.

Choi, C. H., Kim, T., Lee, G., & Lee, S. K. (2014). Testing the stressor–strain–outcome model of customer-related social stressors in predicting emotional exhaustion, customer orientation and service recovery performance. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 36, 272–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2012.09.009.

Cole, D. A., & Maxwell, S. E. (2003). Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112, 558–577. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558.

Collins, L. M., Schafer, J. L., & Kam, C. M. (2001). A comparison of inclusive and restrictive strategies in modern missing data procedures. Psychological Methods, 6, 330–351.

Colquitt, J. A., & Greenberg, J. (2003). Organizational justice: A fair assessment of the state of the literature. In J. Greenberg (Ed.), Organizational behavior: The state of the science (p. 165–210). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Cortina, L. M., Magley, V. J., Williams, J. H., & Langhout, R. D. (2001). Incivility in the workplace: Incidence and impact. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 6(1), 64–80. https://doi.org/10.1037//1076-8998.6.1.64.

Cortina, L. M., Kabat-Farr, D., Magley, V. J., & Nelson, K. (2017). Researching rudeness: The past, present, and future of the science of incivility. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 299–313. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000089.

Crossley, C. D., Bennett, R. J., Jex, S. M., & Burnfield, J. L. (2007). Development of a global measure of job embeddedness and integration into a traditional model of voluntary turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(4), 1031–1042.

Donovan, M. A., Drasgow, F., & Munson, L. J. (1998). The perceptions of fair interpersonal treatment scale: Development and validation of a measure of interpersonal treatment in the workplace. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(5), 683–692. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.83.5.683.

Dormann, C., & Zapf, D. (2004). Customer-related social stressors and burnout. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 9(1), 61–82.

Folger, R. (2001). Fairness as deonance. In S. Gilliland, D. D. Steiner, & D. P. Skarlicki (Eds.), Theoretical and cultural perspectives on organizational justice (pp. 3–33). Greenwich, Connecticut: Information Age Publishing.

Ford, M. T., & Huang, J. (2014). The health consequences of organizational injustice. In S. Leka & R. R. Sinclair (Eds.), Contemporary occupational health psychology (pp. 35–50). Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd..

Foulk, T., Woolum, A., & Erez, A. (2016). Catching rudeness is like catching a cold: The contagion effects of low-intensity negative behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(1), 50–67. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000037.

Fox, S., Spector, P. E., & Miles, D. (2001). Counterproductive work behavior (CWB) in response to job stressors and organizational justice: Some mediator and moderator tests for autonomy and emotions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 59, 291–309.

Greco, L. M., O’Boyle, E., & Walter, S. L. (2015). Absence of malice: A meta-analysis of nonresponse bias in counterproductive work behavior research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(1), 75–97. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037495.

Griffin, B. (2010). Multilevel relationships between organizational-level incivility, justice and intention to stay. Work and Stress, 24(4), 309–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2010.531186.

Hamaker, E. L., Kuiper, R. M., & Grasman, R. P. P. P. (2015). A critique of the cross-lagged panel model. Psychological Methods, 20(1), 102–116. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038889.

Hershcovis, M. S., Neville, L., Reich, L., Christie, A. M., Cortina, L. M., & Shan, J. V. (2017). Witnessing wrongdoing: The effects of observer power on incivility intervention in the workplace. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 142, 45–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2017.07.006.

Hershcovis, M. S., Cameron, A.-F., Gervais, L., & Bozeman, J. (2018). The effects of confrontation and avoidance coping in response to workplace incivility. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(2), 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000078.

Holm, K., Torkelson, E., & Bäckström, M. (2015). Models of workplace incivility: The relationships to instigated incivility and negative outcomes. BioMed Journal International, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/920239.

Holm, K., Torkelson, E., & Bäckström, M. (2019). Exploring links between witnessed and instigated workplace incivility. International Journal of Workplace Health Management, 12(3), 160–175. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJWHM-04-2018-0044.

Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55.

Ju, D., Xu, M., Qin, X., & Spector, P. (2019). A multilevel study of abusive supervision, norms, and personal control on counterproductive work behavior: A theory of planned behavior approach. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 26(2), 163–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051818806289.

Karasek, R., & Theorell, T. (1990). Healthy work: Stress, productivity and the reconstruction of working life. New York: Basic Books.

Lai, K., & Green, S. B. (2016). The problem with having two watches: Assessment of fit when RMSEA and CFI disagree. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 51(2–3), 220–239.

Leiter, M. P. (2019). Costs of incivility in workplaces and potential remedies. In R. J. Burke, & A. M. Richardsen, (Eds.), Creating Psychologically Healthy Workplaces (pp. 235–250). ludwig.lub.lu.se/https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788113427

Li, C.-H. (2016). Confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data: Comparing robust maximum likelihood and diagonally weighted least squares. Behavioral Research, 48, 936–949. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-015-0619-7.

Lim, S., & Lee, A. (2011). Work and non-work outcomes of workplace incivility: Does family support help? Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 16(1), 95–111.

Lim, S., Cortina, L. M., & Magley, V. J. (2008). Personal and workgroup incivility: Impact on work and health outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(1), 95–107. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.1.95.

Little, T. D. (2013). Longitudinal structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press.

Loi, N. M., Loh, J. M. I., & Hine, D. W. (2015). Don’t rock the boat: The moderating role of gender in the relationship between workplace incivility and work withdrawal. Journal of Management Development, 34(2), 169–186. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-12-2012-0152.

Martin, R. J., & Hine, D. W. (2005). Development and validation of the uncivil workplace behaviour questionnaire. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 10(4), 477–490. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.10.4.477.

Matthews, R. A., & Ritter, K.-J. (2019). Applying adaptation theory to understand experienced incivility processes: Testing the repeated exposure hypothesis. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 24(2), 270–285. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000123.

Miner, K. N., & Cortina, L. M. (2016). Observed workplace incivility toward women, perceptions of interpersonal injustice, and observer occupational well-being: Differential effects for gender of the observer. Frontiers in Psychology, 7(482), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00482.

Ming, X., Bai, X., & Lin, L. (2020). Kick the cat: A serial crossover effect of supervisors’ ego depletion on subordinates’ deviant behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 11(1314), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01314.

Mittal, S., Shubham, S., & A. (2017). Multidimensionality in organizational justice-trust relationship for newcomer employees: A moderated-mediation model. Current Psychology, 38, 737–748. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-017-9632-6.

Mohammad, J., Quoquab, F., Idris, F., Al Jabari, M., & Wishah, R. (2019). The mediating role of overall fairness perception: A structural equation modelling assessment. Employee Relations: The International Journal, 41(3), 614–636. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-10-2017-0243.

Osatuke, K., Moore, S. C., Ward, C., Dyrenforth, S. R., & Belton, L. (2009). Civility, respect, engagement in the workforce (CREW): Nationwide organization development intervention at veterans health administration. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 45, 384–410. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886309335067.

Pearson, C. M., & Porath, C. L. (2005). On the nature, consequences and remedies of workplace incivility: No time for “nice”? Think again. Academy of Management Executive, 19(1), 7–18.

Pearson, C. M., Andersson, L. M., & Porath, C. L. (2000). Assessing and attacking workplace incivility. Organizational Dynamics, 29(2), 123–137.

Pejtersen, J., Kristensen, T. S., Borg, V., & Bjørner, J. B. (2010). The second version of the Copenhagen psychosocial questionnaire. Scand Journal of Public Health, 38, 8–24. https://doi.org/10.1077/1403494809349858.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Porath, C. L., & Pearson, C. M. (2010). The cost of bad behavior. Organizational Dynamics, 39(1), 64–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2009.10.006.

Porath, C., MacInnis, D., & Folkes, V. (2010). Witnessing incivility among employees: Effects on consumer anger and negative interferences about companies. Journal of Consumer Research, 37, 292–303. https://doi.org/10.1086/651565.

Ramsay, S., Troth, A., & Branch, S. (2011). Work-place bullying: A group processes framework. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 84, 799–816. https://doi.org/10.1348/2044-8325.002000.

Reich, T. C., & Hershcovis, M. S. (2015). Observing workplace incivility. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(1), 213–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036464.

Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36.

Sayers, J. K., Sears, K. L., Kelly, K. M., & Harbke, C. R. (2011). When employees engage in workplace incivility: The interactive effect of psychological contract violation and organizational justice. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 23, 269–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10672-011-9170-6.

Schad, E., Torkelson, E., Bäckström, M., & Karlson, B. (2014). Introducing a Swedish translation of the workplace incivility scale. Lund Psychological Reports, 14(1), 1–15.

Schilpzand, P., de Pater, I. E., & Erez, A. (2016). Workplace incivility: A review of the literature and agenda for future research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37, 57–88. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1976.

Silva, M. R., & Caetano, A. (2014). Organizational justice: What changes, what remains the same? Journal of Organizational Change Management, 27(1), 23–40. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-06-2013-0092.

Skarlicki, D. P., & Folger, R. (1997). Retaliation in the workplace: The roles of distributive, procedural, and interactional justice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 434–443.

Sprigg, C. A., Niven, K., Dawson, J., Farley, S., & Armitage, C. J. (2019). Witnessing workplace bullying and employee well-being: A two-wave field study. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 24(2), 286–296. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000137.

Torkelson, E., Holm, K., & Bäckström, M. (2016). Workplace incivility in a Swedish context. Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies, 6(2), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.19154/njwls.v6i2.4969.

van de Schoot, R., Lugtig, P., & Hoox, J. (2012). A checklist for testing measurement invariance. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 9(4), 486–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2012.686740.

Vasconcelos, A. F. (2020). Workplace incivility: A literature review. International Journal of Workplace Health Management. Online first publication. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJWHM-11-2019-0137.

Zapf, D., Dormann, C., & Frese, M. (1996). Longitudinal studies in organizational stress research: A review of the literature with reference to methodological issues. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 1(2), 145–169. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.1.2.145.

Code Availability

Software code is available from the corresponding author upon request.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Lund University. The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Holm, K., Torkelson, E. & Bäckström, M. Longitudinal Outcomes of Witnessed Workplace Incivility: a Three-Wave Full Panel Study Exploring Mediators and Moderators. Occup Health Sci 5, 189–216 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41542-021-00083-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41542-021-00083-8