Abstract

While previous research has indicated that segmenting work and home is beneficial to employees’ recovery, this study, which includes 130 dual-earner couples, investigates if and when integrating work and home by receiving work-related support from one’s partner fosters employees’ recovery experiences (i.e., psychological detachment, relaxation, mastery). Moreover, we examine couples’ work-linkage (i.e., both partners working in the same organization and/or the same occupation) as a moderator. Additionally, we consider the consequences of offering work-related support for the supporting partner’s recovery experiences. We used the actor-partner interdependence model to account for the dependent structure of dyadic data. Results of multiple group analyses comparing work-linked with non-work-linked couples showed that receiving work-related support from a partner was associated with increased relaxation and mastery experiences, at least among work-linked couples. Work-related support was not associated with employees’ detachment. Providing work-related support was positively related to employees’ mastery experiences in non-work-linked couples only, whereas it was unrelated to psychological detachment and relaxation both in couples with and without work-linkage. Drawing on conservation of resources theory and on boundary theory, the findings of this study shed light on work-related spousal support as an enabler of recovery experiences in work-linked couples, extending the limited view that segmenting work and home is the only beneficial approach for recovery during leisure time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Recovery from work during off-job time is crucial for keeping employees healthy and productive (Sonnentag et al. 2017). For example, employees’ recovery experiences (e.g., psychological detachment, relaxation, mastery) are associated with increased psychological and psychosomatic well-being (Bennett et al. 2018; Sonnentag and Fritz 2007; Steed et al. 2019). However, when employees are exposed to high levels of job stress, they may find it particularly difficult to unwind and replenish their resources during their off-job time, as their job stressors may spill over into their private lives and hinder their recovery processes (Sonnentag 2018; Steed et al. 2019). Hence, building on the effort-recovery model (Meijman and Mulder 1998) and the stressor-detachment model (Sonnentag and Fritz 2015), scholars have argued that segmenting work and non-work domains should enable better recovery, as impermeable boundaries ensure that job demands do not enter the home domain and hinder employees’ recovery processes (Kinnunen et al. 2016; Sonnentag and Fritz 2015). Empirical research has provided initial support for this view (Derks et al. 2014a, b; Park et al. 2011; Sonnentag et al. 2010; Wepfer et al. 2018). For instance, Kinnunen et al. (2016) found that employees who kept their work and private lives separate reported higher detachment, relaxation, and control during leisure time.

However, this view is limited, as it neglects to consider that segmenting work and private life may result in blocking resources that may aid employees’ recovery processes from entering the home domain. For example, when employees separate their work and home lives, they do not share and discuss work-related experiences (e.g., work problems and successes) with their partners. In other words, refraining from discussing work-related problems with one’s partner might lead to missing out on one important source of support. Within the conservation of resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll 1989), partner support is viewed as an important resource that helps in dealing with job stress and facilitates the replenishment of further resources. Initial research has shown that work-related support from a spouse or partner as a specific form of social support is associated with better work–family balance and subsequent family and job satisfaction (Ferguson et al. 2016). However, it is unclear whether work-related spousal support (WRSS) as a form of integration of work and home also contributes to employees’ recovery processes, given that previous research has predominantly focused on segmentation as facilitator of recovery (Kinnunen et al. 2016; Park et al. 2011). Further, it is not clear if work-home integration in the form of WRSS is equally beneficial for all dual-earner couples or if it might be particularly effective for some types of dual-earner couples. Research by Ferguson et al. (2016), for instance, suggests that couples who share a workplace and/or a job (i.e., work-linked couples) particularly benefit from WRSS.

In this study, we draw on COR theory (Hobfoll 1989) and boundary theory (Ashforth et al. 2000) to address these gaps in the literature. First, we examine whether receiving and providing WRSS are associated with increased recovery experiences (i.e., psychological detachment, relaxation, mastery) in a sample of dual-earner couples. The number of dual-earner couples has been steadily increasing (OECD 2011, 2017), and it is important to understand how these couples successfully recover from job stress, given that both partners face the challenge of juggling work and family demands (ten Brummelhuis et al. 2010). The dyadic design of our study not only allows us to investigate the potential benefits of receiving WRSS, but also the potential consequences of providing WRSS. Second, we investigate whether the relationships between WRSS and recovery experiences are stronger among couples with a work-linkage. As work-linked couples have more integrated work and home lives (Halbesleben et al. 2010), resource transfer between work and home and between partners should be facilitated (Bakker and Demerouti 2013). Hence, work-linked partners may particularly benefit from their spouses’ work-related support.

Our study makes several contributions to the literature. First, we add to boundary management literature (Kreiner et al. 2009) as we extend previous research that predominantly focused on work–home segmentation as facilitator of recovery (Hahn and Dormann 2013; Kinnunen et al. 2016; Park et al. 2011; Wepfer et al. 2018). While this line of research rests on the underlying assumption that segmentation prevents stressors from entering the home domain, we advance the perspective that work–home integration may provide resources that promote the replenishment of further resources—that is, employees’ recovery processes. We further contribute to boundary management research by specifying for whom work–home integration may be particularly beneficial as we focus on a couple’s work-linkage as a moderator. Second, we add to recovery literature by extending the limited knowledge regarding contextual predictors of recovery experiences in the home domain (Steed et al. 2019). While previous research has shown that partners may help employees to recover by supporting engagement in recovery activities (Park and Fritz 2015) and distracting them from their work-related problems through absorption in joint activities (Hahn et al. 2012), we examine whether addressing work-related problems also presents an effective strategy for helping employees to recover. Thereby, we complement previous research on predictors of recovery in dual-earner couples (Hahn et al. 2012; Haun et al. 2017; Park and Haun 2017) and help to identify potential points of intervention to promote dual-earner couples’ recovery. Third, this study extends the knowledge about the understudied population of work-linked couples (Fritz et al. 2019). As this special type of couple is characterized by high work-family integration, work-linked couples have a deeper understanding of each other’s work situation and are therefore able to provide unique resources, tailored to the requirements of their partners (Halbesleben et al. 2010; Halbesleben et al. 2012). By examining couples’ work-linkage as a moderator, we clarify how work-linked and non-work-linked couples differ from each other in their recovery prerequisites and needs. Thereby, we answer calls to examine interindividual differences in employees’ recovery processes (Sonnentag et al. 2017) and help to refine recovery theory. Increased knowledge about boundary conditions will help in the development of more targeted practical recommendations for employees in both work-linked and non-work-linked relationships. Finally, the dyadic design of our study allows us to consider consequences of receiving and providing WRSS at the same time, and thereby contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of WRSS.

Theoretical Background

Dual-Earner Couples’ Recovery Experiences

Recovery is conceptualized as a process opposite to the stress process, as cognitive, emotional, and physical systems that were activated during work are halted and return to their baseline levels (Meijman and Mulder 1998). Two complementary theories—the effort-recovery model and COR theory—have been used as predominant frameworks to explain employee recovery. According to the effort-recovery model (Meijman and Mulder 1998), recovery can occur when no further demands are put on the individual. According to COR theory (Hobfoll 2001), recovery can occur when resources are replenished. The basic tenet of COR theory is that people “strive to obtain, retain, foster, and protect those things they centrally value,” i.e., resources (Hobfoll et al. 2018, p. 104). Generally speaking, resources can be anything that is valued in its own right or that drives goal achievement (Halbesleben et al. 2014). COR theory posits that through resource investment, people protect themselves against resource loss and gain additional resources. Therefore, people are motivated to create and to protect resources (Hobfoll 2002). More specifically, having resources available enables the acquisition of new resources, so that resource caravans develop (Hobfoll 2011). In addition, individuals who have greater resources are less likely to lose resources and more capable of gaining resources.

Sonnentag and Fritz (2007) proposed specific off-job experiences that enable employees to get a break from job demands and replenish drained resources. These recovery experiences include psychological detachment, relaxation, mastery experiences, and control during leisure time. In line with previous research (Hahn et al. 2012; Sonnentag et al. 2008), we focused on the first three recovery experiences mentioned above. Psychological detachment refers to “the individual’s sense of being away from the work situation” (Etzion et al. 1998, p. 579). It does not relate primarily to an individual’s physical absence, but to the psychological component of distance such as mental disengagement from work-related issues. Therefore, detachment is a cognitive-emotional state that occurs during specific experiences in leisure time (Fritz et al. 2010). Relaxation refers to mental experiences that are associated with low activation (Sonnentag and Fritz 2007), such as lower blood pressure (Friedman et al. 1996), decreased heart rate or muscle tension (Smith 2005), feelings of serenity, and reduced perception of external stimuli (Stetter 1998). Mastery experiences comprise leisure activities that are challenging but not overtaxing. Typical examples include learning something new in non-work domains or participating in sports (Sonnentag and Fritz 2007). Mastery experiences contribute to recovery because new internal resources like abilities, skills, or self-efficacy can be built up (Hobfoll 1998). Where detachment and relaxation are effective recovery strategies because they do not demand the functional systems that were taxed during work, mastery experiences help with recovery by building up new resources (Sonnentag and Fritz 2007).

According to Newman et al. (2014), recovery experiences represent psychological mechanisms that help employees cope with stressful situations and thus enable subjective well-being. Furthermore, previous research has shown that recovery experiences are important predictors of employees’ health and well-being (Bennett et al. 2018; Newman et al. 2014; Sonnentag and Fritz 2007; Steed et al. 2019). As recovery experiences, over and above work characteristics, substantially contribute to employees’ well-being (Bennett et al. 2018), it is crucial to learn more about their antecedents and how they can be enhanced.

Work–Home Boundaries and Recovery

Given that employees’ recovery processes during leisure time can be impaired by job stressors (Sonnentag 2018; Steed et al. 2019), scholars have proposed segmentation of work and home lives as one approach to prevent job stressors from harming employees’ recovery (Sonnentag and Fritz 2015). Boundary theory explains how people create, maintain, or change boundaries between life domains like work and home, assuming that people have different roles in life domains (Ashforth et al. 2000). Nippert-Eng (1996) proposes that the roles of two different life domains can be highly segmented or highly integrated, depending on the person’s individual preference. Employees vary in the extent to which they desire to integrate or to segment work and private life (Rothbard et al. 2005). In this context, segmentation is defined as “the degree to which aspects of each domain (such as thoughts, concerns, physical markers) are kept separate from one another – cognitively, physically, or behaviorally” (Kreiner 2006, p. 485). This means that for employees who prefer to separate their work and home roles, it is more difficult to cross temporal, physical, and social boundaries (Ashforth et al. 2000) at the end of the working day. In contrast, highly integrated roles overlap, are characterized by similarity, and “are not tied to specific places and times” (Ashforth et al. 2000, p. 479). Both high segmentation and high integration of work and home roles can be beneficial or detrimental for employees (Wepfer et al. 2018). On the one hand, high integration makes role transitions easier. For instance, positive mood because of success at work can spill over to the home domain (Halbesleben et al. 2010), which may lead to positive outcomes like work–family enrichment (Greenhaus and Powell 2006). On the other hand, with high integration it is possible for role demands to overlap and role blurring to occur (Ashforth et al. 2000) .

Previous research investigating the role of work–home boundaries on employee recovery predominantly employed the perspective that high segmentation prevents the spillover of negative work experiences into private life and can help people to recover from work (Park et al. 2011; Sonnentag et al. 2010). This perspective is based on the assumptions of the effort-recovery model, which holds that recovery can occur when employees are no longer exposed to job demands (Meijman and Mulder 1998). However, this perspective does not embrace the possibility that resources that stem from the work domain or the integration of the work–home domain may help employees to recover as well—resources may promote the acquisition and replenishment of further resources, as put forward by COR theory (Hobfoll 2001). In this study, we will address this gap in the literature by examining the providing and receiving of WRSS as a work–home integration strategy and its effects on the recovery experiences of employees and their partners.

WRSS as Work–Home Integration Strategy

According to COR theory (Hobfoll 1989), social support is an important resource that can help to preserve existing resources and to gain new resources, which in turn prevents stress reactions. WRSS constitutes a specific form of social support, defined as “the emotional and instrumental support provided by one spouse to the other regarding work related activities” (Ferguson et al. 2016, p. 38).Footnote 1 Generally, providing and receiving WRSS refers to sharing and discussing work-related matters with one’s partner, which implies integrating work into the home domain. More specifically, WRSS comprises four subdimensions, each of which describes a specific work-related feature as beneficial for supporting and understanding one’s partner (Janning 2006). First, shared network refers to knowing the partner’s colleagues, which provides the partner with a better understanding when the employee talks about work issues and mentions the people involved. Second, sensitive companion refers to knowing the partner’s work environment. This may be the case, for example, when a physician’s partner understands that during particular time periods, the physician is on call or may have to return to work in case of an emergency. Third, understanding of subject matter denotes understanding the content of the partner’s job. When partners have job-related field knowledge, they can be more supportive when talking about work issues. Finally, logistics/time together refers to the possibility of seeing one’s spouse during working hours, for example, during a coffee break or in a common area. Together, these subdimensions represent the encompassing level of support from the partner to the employee, made up of both instrumental and emotional forms of support (Ferguson et al. 2016).

It is important to note that knowing and understanding the content of a partner’s job and organizational and social work environment do not require employees to work in the same organization or to have the same job, as work-linked couples do. Sharing work experiences with one’s partner and discussing work-related issues with that partner gives them insight into critical aspects of one’s job and enables employees to understand their partners’ work environment and job without being part of it. Admittedly, it may be easier for work-linked couples to provide WRSS; however, previous research has revealed that the differences in WRSS between work-linked and non-work-linked couples were not substantial (Ferguson et al. 2016), which indicates that all partners—with and without a work-link—can provide WRSS. However, as the subdimension logistics/time together is probably predominantly available to work-linked couples, we decided to focus on the first three subdimensions (shared network, sensitive companion, and understanding of subject matter), in order to be able to separate the effects of WRSS and a couple’s work-linkage.

Work-Related Support and Recovery Experiences

Drawing from COR theory, we propose that WRSS facilitates employees’ recovery because it provides an important resource that helps individuals to preserve and produce other valued resources (Hobfoll 2002). Specifically, we suggest that receiving WRSS should promote psychological detachment, relaxation, and mastery experiences. WRSS may support employees’ recovery experiences through different pathways, as it may require different preconditions to occur.

First, receiving WRSS should help employees to distance themselves from work and unwind from job stress. Empirical research suggests that employees have difficulties in recovering when they face problems at work, such as conflicts or unfinished tasks (Volmer et al. 2012; Weigelt and Syrek 2017). Unfinished tasks or work problems keep the mind preoccupied with work (Martin and Tesser 1996). Thus, working on a solution to finish the tasks cognitively should help employees attain peace of mind (Weigelt and Syrek 2017). Therefore, we propose that partners’ work-related support should help employees to detach from work. By providing the employee with emotional and instrumental support, their partner can help to resolve work problems that hinder effective recovery. Partners who know the employees’ colleagues and understand their work environments and job contents can be supportive by helping to resolve work problems together. At first glance, addressing work issues to mentally disengage from work sounds contradictory. Discussing work-related issues with a partner may indeed lower psychological detachment in the short term; however, addressing problems may help to solve these problems and facilitate detachment in the long run, thus enabling higher overall levels of detachment. Hence, although WRSS may impair employees’ detachment in the moment of receiving it (e.g., during the conversation at dinner time), it should facilitate better detachment afterwards (e.g., during the rest of the evening or during the following evenings). Moreover, the feeling that one is able to reach out for support if needed (perceived support availability; Bolger et al. 2000; Wethington and Kessler 1986) can be a relief in itself and might facilitate detachment from work. COR supports this view by positing that the effects of resources are rather long-term across time and different circumstances (Hobfoll et al. 2018).

Second, when employees are still occupied with work issues at the end of the working day, they have more trouble relaxing (Cropley and Millward Purvis 2009). Having a supportive partner who understands the employee’s work situation can help the employee to calm down and to reduce physiological activation. Empirical research provides first support for these hypotheses. Sonnentag and Fritz (2007) found emotional social support to be associated with increased psychological detachment and relaxation. In a recent study, Haun et al. (2017) found partners’ general social support to be associated with increased detachment.

Third, we propose that receiving WRSS is associated with increased mastery experiences. As mastery experiences refer to challenging activities such as sports or learning a new hobby, they require the investment of resources. Receiving WRSS should help employees to accumulate the resources necessary for investment in mastery experiences. COR theory emphasizes the process of resource accumulation (Hobfoll 2011). The more resources individuals already possess, the more capable they are of acquiring additional resources, which results in the accumulation of resources, or so-called resource caravans (Hobfoll 2011). Having a partner who tries to understand work-related issues and assists in solving work problems should lead to resource gains. For example, resolving work-related issues with the help of a partner makes the employee feel competent and self-confident as s/he finds ways to cope with difficult situations. Hence, employees may feel more motivated to engage in challenging activities. Furthermore, successful work-related support can be energy-providing, which results in employees who are inspired to use their acquired resources during leisure time. Hence, they are more likely to engage in challenging leisure activities that facilitate mastery experiences. Previous research supports the idea that resolving problems promotes mastery experiences as Sonnentag and Fritz (2007) found active coping as a problem-focused strategy is positively associated with mastery experiences. Further, research by Park and Fritz (2015) suggests that having a supportive spouse facilitates employees’ mastery experiences. Taken together, we propose the following:

-

H1:

WRSS is positively associated with a) psychological detachment, b) relaxation, and c) mastery experiences.

The Moderating Role of Couples’ Work-Linkage

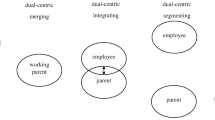

With the growing number of two-income households, it is becoming more likely for couples to work at the same company or have the same profession. For example, Hyatt (2015), who investigated microdata from the US Census 2000, indicated that 11 to 13% of dual-earner couples in the US work for the same employer. In Germany, 29% of dual-earner academic couples are employed in the same occupational sector (German micro census 2004; Rusconi and Solga 2007). According to Halbesleben et al. (2010), “work-linked couples can be linked by their work in one of three ways: sharing only an occupation (e.g., both are nurses but at different hospitals), sharing only a workplace (e.g., both work at the same hospital, but one as a nurse and one as a sonographer), or sharing both an occupation and a workplace (e.g., both are nurses at the same hospital)” (p. 372).

The special situation of work-linked couples can be described by boundary theory (Janning 2006). As already mentioned, work and home roles vary from highly segmented to highly integrated depending on the individual (Nippert-Eng 1996). Work-linked couples are likely to have highly integrated work and home roles because their work and home roles are more similar: they are accompanied by the same person in both roles (either physically, when partners have the same workplace, or mentally, when they have the same occupation), creating closeness between the partners (Janning 2006). Empirical evidence has confirmed that work-linked couples are characterized by higher work–family role integration (Halbesleben et al. 2010) and positive work-to-family spillover (Moen and Sweet 2002), which can provide unique resources.

We propose that couples’ work-links strengthen the relationship between WRSS and recovery experiences, as work-linked partners should be able to provide more efficient WRSS. According to COR theory, the most effective resources are those that are highly relevant to one’s specific situation and needs (Hobfoll 2001). As work-linked couples know each other’s work and family/home situations and have a deeper understanding of each other’s work and/or organizational situations (Halbesleben et al. 2012), they are able to tailor their support provision to the unique requirements of their partner. Furthermore, in line with boundary theory, work-linked couples’ work and home roles are blurred (Janning 2006), which can mean that resource movement across the two roles and domains requires less effort. More specifically, the support-providing partner can reinvest his/her work resources more easily and the support-receiving partner is more likely to benefit from the support (Ferguson et al. 2016). Spouses working in the same company or having the same occupation have a better understanding of their partners’ working conditions (Janning 2006). Thus, work-linked partners may be more sensitive to their partners’ needs and be more willing to support their partner during stressful times than non-work-linked partners. For instance, work-linked partners should be more likely to assist in solving their partner’s work issues, thereby facilitating recovery. When partners work together, they do not have to explain their current work situation to their spouse because s/he is already aware of it. Likewise, when partners have the same occupation, they can share work-related perspectives and opinions and can rely on their own experiences when supporting their spouse. As a result, due to their work-related similarity, work-linked couples could give advice that is more helpful so that work problems are discussed in a more satisfactory and faster way, which should enable employees to recover from work-related stress. Empirical research supports the idea that work-related support is more efficient when provided by a work-linked partner. For example, Halbesleben et al. (2010) showed that for couples with work-linkage, spousal instrumental support is related to decreased emotional exhaustion, while for couples without work-linkage this was not the case. Ferguson et al. (2016) found that WRSS was associated with increased family and job satisfaction in work-linked couples only.

-

H2:

A couple’s work-link moderates the associations between WRSS and a) detachment, b) relaxation, and c) mastery experiences, such that the positive associations are stronger for work-linked couples compared with non-work-linked couples.

Potential Consequences of WRSS for the Supporting Partner

While we argue that receiving WRSS should be beneficial for employees’ recovery experiences, it is unclear if providing WRSS is associated with consequences for the support provider’s own recovery experiences and whether these consequences are positive or negative. On the one hand, providing WRSS to the partner may distract a person from their own work-related thoughts and thus enable psychological detachment. Similarly, providing support may mean spending time with one’s partner and becoming absorbed in joint activities. Absorption in joint activities with one’s partner facilitates relaxation (Hahn et al. 2012). Furthermore, providing support to their partners may make employees feel competent and needed (e.g., Williamson and Clark 1989), which might constitute a mastery experience in itself and may motivate employees to engage in further mastery activities.

On the other hand, providing WRSS involves talking about the partners’ work in order to give advice. Talking about work may stimulate thoughts about one’s own work, and thus, hinder psychological detachment (cf. Hahn and Dormann 2013). Likewise, providing support may require refraining from relaxing activities and taking over some of the partner’s obligations. In addition, providing WRSS may deplete resources that are necessary for engagement in mastery activities. Hence, providing support may decrease mastery experiences. Therefore, since there are competing arguments for positive and negative associations between providing WRSS and recovery experiences, we do not present specific hypotheses, but rather, formulate open research questions regarding the relationship between providing WRSS and recovery experiences.

Research question 1: Is providing WRSS associated with employees’ recovery experiences?

Research question 2: Are the relationships between providing WRSS and employees’ recovery experiences stronger among work-linked couples?

Method

Sample and Procedure

We collected data from German dual-earner couples living in a heterosexual relationship in which both partners worked at least 10 h per week. We recruited participants via online advertisements in social media community groups (i.e., groups for dual-earner-couples, (trainee) teachers, research associates, and working mothers) and via information leaflets about our study distributed in local facilities in several German cities (i.e., in cafés, shops, dance schools, and childcare facilities). According to local regulations, no formal research ethics scrutiny was undertaken. All participants received detailed information about the study before they registered for participation. Participation was voluntary. When registering for participation, all participants provided their informed consent to take part in the study. Data provided by the participants was handled in a way to ensure anonymity. Once the data was collected, participants received a report on the outcomes of the study, as well as recommendations for managing work stress as a couple. In addition, all participants were eligible to take part in a lottery drawing of online gift cards.

A total of 465 participants filled in a web-based survey individually (i.e., independent of their partners) and were asked to invite their partners to fill in the same web-based survey. In addition, we sent participants’ partners an invitation to participate in the study. We matched individual surveys by a code created by each couple consisting of both partners’ birth dates. We could not match the data for 205 of the individuals because their partners did not participate in the study, which resulted in a final sample of 130 heterosexual dual-earner couples (N = 260 individuals). We tested whether the individuals in the final sample of couples differed from those individuals whose partners did not participate. We did not find any significant differences across these groups regarding the study variables and couple characteristics (years in relationship, children, age).

The majority of the couples (83.8%) lived together,Footnote 2 and 25.4% of the couples had at least one child living in their household. The average relationship length was 8.01 years (SD = 7.51). On average, the male partners were 34.64 years old (SD = 8.55) and worked 40.43 (SD = 10.40) hours per week. The female partners were 31.98 years old (SD = 8.13) and worked 36.46 (SD = 12.80) hours per week. Our participants were quite well-educated, with 69.9% holding an academic degree.

Measures

In our web-based survey, all participants provided demographic and work-related information (age, gender, education, children living in the household, duration of relationship, working hours).

Work-Related Spousal Support

We used nine items from three subdimensions of the recently developed work-related spousal support scale (Ferguson et al. 2016).Footnote 3 Participants indicated on a five-point Likert scale the extent to which they agreed with the following examples: “It is easy to discuss work issues with my spouse because s/he understands the people involved” (shared network), “My spouse is sensitive to the unique environment I work in and can help me manage my many demands” (sensitive companion), and “When I run into a problem at work my spouse can help me solve it because s/he knows the subject matter” (understanding of subject matter; 1 = I do not agree at all to 5 = I fully agree). Cronbach’s alpha was .93 for male and .94 for female participants. Consistent with Ferguson et al. (2016), we used an overall WRSS score in our analyses.

Recovery Experiences

To assess recovery experiences, we used nine items of Sonnentag and Fritz’s (2007) Recovery Experience Questionnaire. Participants indicated, on a five-point Likert scale, the extent to which they agreed with the following examples: “During leisure time, I forget about work” (detachment), “During leisure time, I use the time to relax” (relaxation), and “During leisure time, I do things that challenge me” (mastery experiences; 1 = I do not agree at all to 5 = I fully agree). Cronbach’s alpha of the subscale detachment was .83 among men and .85 among women. Cronbach’s alpha of the subscale relaxation was .80 among men and .81 among women. Cronbach’s alpha of the subscale mastery experiences was .87 among men and .77 among women.

Work-Linkage

Similar to Halbesleben et al. (2010), we asked participants to answer the following two statements: “Your partner works in the same occupation as you,” and “Your partner works in the same company as you” (0 = no, 1 = yes). Following previous research (Ferguson et al. 2016; Halbesleben et al. 2012), we created a variable by dummy-coding those who answered “yes” to one or both of the questions as 1 and those who replied “no” as 0. In our sample, 37.7% of the couples (n = 49) were work-linked. More specifically, 10% (n = 13) worked only in the same occupation, 11.5% (n = 15) worked only at the same company and 16.2% (n = 21) worked both in the same occupation and at the same company.

Data Analysis

Responses from individuals in a couple are interdependent, due to shared experiences (Kenny et al. 2006). To account for this nonindependence and mutual influence between partners, we used the actor-partner interdependence-model (APIM; Kenny et al. 2006). In the APIM, the dyad is the unit of analysis, and both the actor effects (an employee’s dependent variable is regressed on their own independent variable), as well as the partner effects (an employee’s dependent variable is regressed on their partner’s independent variable) are estimated simultaneously. In the APIM, there are two types of correlations: 1) the exogenous predictor variables, and 2) the error terms of the outcome variables.

We tested our hypotheses in Mplus Version 7.3 (Muthén and Muthén 1998-2012). Our model consisted of two exogenous predictor variables (Partner A’s and Partner B’s WRSS, respectively) and six endogenous outcome variables (Partner A’s and Partner B’s recovery experiences, respectively). We used full information maximum likelihood estimation.

Results

In Table 1, the mean scores, standard deviations, and intercorrelations between the study variables are shown. Women’s and men’s WRSS were highly positively related while women’s recovery experiences were unrelated to men’s recovery experiences.

Preliminary Analyses

Although men and women differ on a conceptual level, Kenny et al. (2006) recommended to test for empirical distinguishability, that is, whether the conceptual distinguishability actually matters in terms of differences in means, variances, and covariances in the study variables (WRSS and recovery experiences) for the dyad members (Kenny et al. 2006). Constraining parameters to be equal simplifies the model, and thus complies with the parsimony principle in structural equation modeling (Kline 2016). Therefore, we performed an omnibus test of distinguishability: we compared the fit of a model in which means, variances, and covariances of the study variables were constrained to be equal across both partners in dyads against another model in which they were free to vary (Ackerman et al. 2011). As men and women did not differ (χ2(20) = 25.00, p = .20), we treated men and women as indistinguishable, that is, we constrained means, variances, and covariances, as well as actor and partner effects, to be equal across men and women.

Hypothesis Testing

Our gender-equated model fit the data well (χ2(20) = 25.00, p = .20, CFI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.04). The effect estimates are presented in Table 2. Hypotheses 1 (a through c) stated that WRSS is positively associated with detachment, relaxation, and mastery, respectively. The data did not support Hypothesis 1a, as there was no significant association between WRSS and detachment. We found a significant main effect of WRSS on relaxation, which supported Hypothesis 1b. The results also showed that WRSS was not significantly related to mastery experiences, failing to support Hypothesis 1c.

Hypotheses 2a through 2c stated that the associations between WRSS and recovery experiences are moderated by a couple’s work-link. Table 3 displays the relationships between WRSS and recovery experiences for couples with and without a work-link. Through multiple group analyses, we compared work-linked couples with non-work-linked couples. In order to test for significant differences between the two groups, we compared two models: first, a model in which the regression coefficient between the two relevant variables is constrained to be equal across work-linked and non-work-linked couples; and second, a model in which the regression coefficient between the two relevant variables is free to vary across the two groups. Regarding the association between WRSS and detachment, the equality constraints did not change model fit significantly (Δχ2(1) = 0.001, p = .975), showing that the association between WRSS and detachment for work-linked couples did not differ significantly from the association of non-work-linked couples. Thus, our data did not support Hypothesis 2a. Setting equality constraints regarding the association between WRSS and relaxation (Hypothesis 2b) decreased model fit significantly (Δχ2(1) = 4.779, p = .029). Thus, the two groups differed significantly, showing that among work-linked couples, WRSS was positively associated with relaxation (B = 0.322, p = .006), whereas among non-work-linked couples there was no significant association (B = 0.050, p = .323). Therefore, Hypothesis 2b was supported. Regarding the association between WRSS and mastery experiences, the equality constraints decreased model fit significantly (Δχ2(1) = 4.355, p = .037), showing a significant moderation effect. Among work-linked couples, there was a positive association between WRSS and mastery experiences (B = 0.259, p = .049), whereas this association was not significant among non-work-linked couples (B = −0.019, p = .784). Thus, Hypothesis 2c was supported.

To answer our open research questions, we inspected the partner effects of WRSS on recovery experiences, since the partner effects of receiving WRSS indicate the effects of providing WRSS. For research question 1, the associations between providing WRSS and employees’ detachment, relaxation, and mastery experiences, respectively, were non-significant (see Table 2). To test research question 2, the potential moderator effect of work-linkage, we compared couples with and without work-linkage (see Table 3). We found no significant associations between providing WRSS and employees’ detachment and relaxation, respectively, among work-linked and non-work-linked couples. There was a positive association between providing WRSS and employees’ mastery experiences for non-work-linked couples only. As outlined above, we set equality constraints regarding the association between providing WRSS and employees’ mastery experiences in order to check for differences between couples with and without work-linkage. This decreased model fit significantly (Δχ2(1) = 4.227, p = .040), showing that only for non-work-linked couples, providing WRSS was positively related to employees’ mastery experiences.

Additional Analyses

To further explore the relationships between WRSS and recovery experiences, we investigated the associations of the three WRSS subfacets—shared network, sensitive companion, and understanding of subject matter—with recovery experiences, by including the three subscales as predictors of both employees’ and their partners’ recovery experiences.Footnote 4 Overall, we found one significant actor effect: the sensitive companion subscale was positively related to employees’ relaxation (B = 0.138, p = .029). The remaining associations between employees’ WRSS subscales and employees’ recovery experiences were non-significant. Regarding partner effects (i.e., employees’ WRSS as predictors of partners’ recovery experiences), the shared network subscale was negatively associated with partners’ relaxation (B = −0.105, p = .013), whereas the remaining associations between employees’ WRSS subscales and partners’ recovery experiences were non-significant.

Regarding the moderating role of a couple’s work-link, we found that the relationship between sensitive companion and relaxation differed among work-linked and non-work-linked couples. The sensitive companion subscale was associated with employees’ increased relaxation in work-linked couples (B = 0.271, p = .014), but not in non-work-linked couples (B = 0.089, p = .303). Furthermore, the relationship between the understanding of subject matter subscale and mastery also differed between work-linked couples (B = 0.259, p = .009) and non-work-linked couples (B = −0.081, p = .258). There was only one significant difference in the partner effects of the WRSS subscales: the relationship between employees’ understanding of subject matter and their partners’ mastery was non-significant among work-linked couples (B = −0.178, p = .168) and significant among non-work-linked couples (B = 0.246, p = .003).

Discussion

The aim of this study of dual-earner couples was to investigate whether WRSS as a strategy to integrate work and home is beneficial to employees’ recovery experiences. Further, we examined whether the hypothesized relationships differed among couples with and without a work-link. We found that WRSS was positively associated with relaxation and mastery experiences in work-linked couples, but not in couples without work-link. WRSS was unrelated to psychological detachment both in couples with and without work-linkage. In addition, we examined the consequences of providing WRSS on recovery experiences. We found that providing WRSS was positively related to employees’ mastery experiences in non-work-linked couples only. Providing WRSS was not related to psychological detachment or relaxation, both in couples with and without work-linkage.

WRSS and Recovery Experiences in Couples with and without a Work-Link

Regarding the link between WRSS and recovery experiences, we found that receiving WRSS is beneficial to work-linked couples only. As work-linked couples are connected via their work, they are more likely to benefit from their partners’ work-related help in terms of increased relaxation. Furthermore, due to their greater similarity with their partners, work-linked couples seem to be able to reinvest the resources they gained by receiving social support into challenging activities during leisure time (mastery experiences). Adding to recent findings on the link between types of partners’ support and employees’ recovery (Haun et al. 2017; Park and Fritz 2015; Park and Haun 2017), we showed that for work-linked couples, receiving WRSS is effective in promoting relaxation and mastery experiences. Thus, our results support COR theory (Hobfoll 2002) by showing that partner support is an important resource that facilitates employees’ recovery processes. In contrast to previous research that found that work–home integration hinders employee recovery (Kinnunen et al. 2016; Wepfer et al. 2018), our findings suggest that not all forms of work–home integration are detrimental to employees’ recovery. Our results show that, at least for work-linked dual-earner couples, integrating work and home by receiving work-related support from a partner during leisure time is useful. However, for non-work-linked couples, receiving WRSS was not a significant predictor of recovery experiences. Partners without work-linkage may not be able to provide efficient WRSS, as they lack field knowledge regarding employees’ work tasks and contexts. Therefore, discussing work-related problems with a non-work-linked partner may simply be a reminder of work rather than a helpful resource, and it does not contribute to their recovery. Hence, our findings suggest that couples without work-linkages do not benefit from high work–home integration (in terms of high WRSS), but may be more likely to profit from other types of spousal support for their recovery, such as general or recovery-specific support (Haun et al. 2017; Park and Fritz 2015; Park and Haun 2017). A couple’s work-link seems to be the precondition under which receiving WRSS is beneficial to recovery in dual-earner couples. This finding highlights the importance of investigating interindividual differences in recovery (Sonnentag et al. 2017) and contributes to boundary management literature (Kreiner et al. 2009) by extending the limited view that segmenting work and home is the only way to help employees recover. As previous studies mainly focused on technology use at home being a detrimental work–home integration strategy (Derks et al. 2014a, b; Park et al. 2011), we advanced boundary management by showing that another type of integration, namely WRSS, can be beneficial for some employees, namely those employees living in work-linked relationships.

Results of our additional analyses suggest that different facets of WRSS may be particularly relevant for different recovery experiences of work-linked couples. On the subscale level, the sensitive companion subdimension was associated with increased relaxation, whereas the understanding of subject matter subdimension was associated with increased mastery experiences. These findings suggest that for employees to relax during off-job time, having a partner who understands the special demands of one’s work (i.e., sensitive companion) seems more important than having a partner who knows the people at work (i.e., shared network) or the job contents (i.e., understanding of subject matter). In contrast, for employees to have mastery experiences, having a work-linked partner who understands the subject matter seems to be the most relevant dimension of WRSS.

Contrary to our expectations, WRSS was not associated with employees’ detachment, neither among work-linked nor among non-work-linked couples. We supposed that WRSS would help employees to find solutions for work-related problems that keep them from switching off mentally during off-job time. Successfully solving work problems with the partner, then, should facilitate detachment from work during leisure time. In addition, we suggested that knowing that support is available (perceived support availability; Bolger et al. 2000; Wethington and Kessler 1986) may be a relief in and of itself, and therefore may facilitate detachment. However, WRSS requires that at first, employees must deal with work-related thoughts and discussions so that work demands are cognitively activated, and therefore, detachment is impeded. Given our cross-sectional data, we cannot unravel these possible temporal sequences of WRSS and detachment, which could explain the non-existing association between WRSS and detachment in our study. Another explanation for the non-significant results regarding detachment might be that employees may have perceived their partners’ work-related support as threat to their self-esteem rather than as a helpful resource. According to the threat-to-self-esteem model (Nadler and Jeffrey 1986), receiving support may evoke feelings of dependency, indebtedness, and incompetence (Gleason et al. 2003). When employees are focused on why they were not able to solve their difficulties on their own, the feeling of detachment cannot occur.

Although the consequences of receiving WRSS for employees’ recovery experiences were the focus of this study, the dyadic design of this study allowed us to investigate the consequences of providing WRSS. Given that previous theoretical and empirical research did not allow clear conclusions, we examined the consequences of providing support in a more exploratory way. Overall, providing support (i.e., partner effects of receiving work-related support) was not associated with recovery experiences. However, among couples without work-linkage, providing WRSS was associated with increased mastery, whereas this was not the case among couples with work-linkage. This finding suggests that providing support is an energy-providing experience for non-work-linked partners, making them more likely to experience mastery. Supporting others evokes feelings of competence and being needed (Williamson and Clark 1989), which may already constitute a mastery experience in itself, and which may stimulate employees to engage in further mastery activities. Being able to support one’s partner in work-related issues may be particularly beneficial for non-work-linked partners as they might not necessarily expect that they can be of help given that they may have only limited insights into their significant other’s work-related problems. Hence, providing work-related support may make them feel particularly competent, thereby stimulating the experience of mastery and the engagement in further mastery activities. The results of our additional analyses seem to support this notion, as understanding of subject matter was the most relevant subfacet driving the positive relationship between providing work-related support and one’s own mastery experiences among non-work-linked couples. Being able to understand a partner’s job content, and thereby be of help to one’s partner, should boost the employees’ feelings of competence, which can, in turn, trigger mastery experiences.

As we investigated couples’ work-linkage as a boundary condition, our study also extends current knowledge regarding the understudied population of work-linked couples (Fritz et al. 2019). We showed that for work-linked couples, high work–home integration is especially conducive to their recovery. With this finding, we supplement empirical evidence on work-linked couples pertaining to the benefits of having work as common ground (Ferguson et al. 2016; Halbesleben et al. 2010). In addition to positive associations between WRSS and work–family balance (Ferguson et al. 2016), we found WRSS was positively related to two different recovery experiences (relaxation and mastery experiences). Thus, our results underline the distinctiveness of work-linked couples.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

When interpreting our results, the study’s limitations should be considered. By using dyadic data, we considered the existing non-independence in couples and were able to separate the influence of each individual’s own predictors from their partner’s. However, the cross-sectional design of our study does not allow causal inferences. While we proposed that receiving WRSS should aid employees’ recovery experiences, it might also be the case that employees who enjoy better recovery experiences are more likely to provide support to their partners. Longitudinal or experimental (intervention) studies are needed to clarify causal relationships and to test for reverse causation. For example, in an intervention study, employees could receive training on how to provide work-related support to their partners. Increases in partners’ recovery experiences after training would provide support for the causal link between WRSS and recovery experiences.

We found no effect of WRSS on employees’ detachment. The one-time measurement of our study variables does not allow the investigation of the temporal dynamics of recovery processes. First, it is possible that in the beginning, WRSS hinders detachment, but when successfully completed, it facilitates detachment. That is, in a first step, when employees start talking about work with their partners, work-related thoughts will arise and impede detachment, but after resolving their work problems through discussions with their partners, employees may be more likely to detach. Second, when WRSS is given may be of importance. Receiving WRSS early during after-work hours may facilitate recovery experiences, whereas receiving WRSS at the end of the evening (shortly before going to bed) may be too late to increase employees’ recovery experiences. Future studies should use diary designs with multiple measurement points during the evening over several days to test the idea that receiving WRSS has immediate negative but lagged positive effects on employees’ detachment. Further, growth modelling techniques (Grimm et al. 2017) could be used to shed more light on the role of time by studying the trajectory of detachment after situations of receiving WRSS.

Based on previous empirical findings and theoretical considerations, we argued that providing and receiving WRSS should affect employees’ recovery experiences and we suggested several underlying mechanisms (e.g., by solving work-related problems, boosting feelings of competence). However, as we did not measure these mechanisms, we cannot explicitly test whether the WRSS effects are indeed explained by these presumed mechanisms. As our study is the first to investigate the link between receiving and providing WRSS and recovery experiences, it can stimulate future research to explore the mediating mechanisms in the link between WRSS and recovery experiences.

In our study, we focused on three recovery experiences: psychological detachment, relaxation, and mastery experiences (Hahn et al. 2012; Sonnentag et al. 2008); but we did not assess control during leisure time, another recovery experience proposed by Sonnentag and Fritz (2007). Previous research has shown that segmenting work and home is associated with increased control during leisure time (Kinnunen et al. 2016; Rexroth et al. 2016). However, receiving WRSS and solving work-related problems with one’s partner may also increase an employee’s feeling of control during leisure time, and thus, enable recovery. Therefore, future research should include control during leisure time when investigating the impact of WRSS on recovery experiences.

As we were interested in the consequences of work–home integration for employees’ recovery, we chose WRSS as the specific type of support for our research. However, to identify the relative importance of a particular type of support, multiple types of social support (e.g., work-related support, recovery-related support, home-based instrumental support) could be compared. Different types of support address different needs (Cutrona 1990), depending on the situation. For instance, an employee that has an urgent work problem to solve may prefer work-related support, whereas an employee that has recently worked a lot of overtime may prefer recovery-related support. Future studies should examine which kind of support is appropriate in different situations and whether different types of support may compensate each other in order to determine the relative importance of different types of support in predicting recovery.

Moreover, having a partner who knows and understands an employee’s work network, working conditions, and job content may also be relevant when the employee has positive experiences at work and can share them with their partner. Gable et al. (2004), for instance, found that having a partner who gives enthusiastic support (e.g., active-constructive responses) increases relationship well-being. Tremmel et al. (2018) showed that positive work-related conversations during after-work hours were positively related to positive affect the next morning. Hence, to provide a more complete view of the predictors and outcomes of WRSS, future studies should consider employees’ positive and negative work experiences as antecedents of WRSS.

Practical Implications

Our findings suggest the importance of partners for work-linked couples’ recovery. Thus, we recommend couples with work-linkages use each other as a resource for their recovery. As we found that discussing work-related issues with a partner is beneficial, we encourage work-linked couples to spend time talking about work with their partners. For non-work-linked couples, receiving WRSS had neither a positive nor a negative consequence regarding recovery experiences. Thus, for now, we recommend couples without work-linkages use other types of partner support, such as general social support or recovery support, which have been proven to be beneficial to dual-earner couples’ recovery in previous studies (Haun et al. 2017; Park and Fritz 2015; Park and Haun 2017).

From an organizational perspective, most organizations are aware that healthy, well-recovered employees are crucial for an organization’s success. As we found WRSS to be helpful for work-linked dual-earner couples, we would recommend organizations remain sensitive to the special requirements of these couples and attempt to involve their work-linked employees’ partners to a larger extent, so that their partners can improve their understanding of the job and the working environment. For instance, organizations may arrange open day events or company parties with employees’ families so that partners can get to know the employees’ colleagues and their work environments.

In addition, findings from this study could be used to design more effective interventions to promote employees’ recovery. On the one hand, recovery interventions (Hahn et al. 2011) might highlight the role of the partner in employee recovery, and on the other hand, boundary management interventions (Rexroth et al. 2016) might be complemented with information regarding instances in which some degree of integration (in the form of WRSS), rather than segmentation, is conducive to employee recovery.

Conclusion

Where previous research highlighted the importance of segmenting work and home for ensuring recovery during leisure time, our study investigated whether integrating work and home by receiving work-related support from one’s spouse facilitated employees’ recovery processes in dual-earner couples. Our study confirmed spousal work-related support as a possible enabler of recovery experiences, at least among work-linked couples, challenging the predominant view that work–home segmentation is preferable for employee recovery. Hence, our findings contribute to a more nuanced view of the relationship between work–home boundaries and recovery and will hopefully serve as springboard for future research on the beneficial and harmful effects of work–home integration and segmentation for recovery.

Change history

15 December 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41542-021-00104-6

Notes

Following Ferguson et al. (2016), we use the term and definition of work-related spousal support. However, we included both married and unmarried couples who were in a stable relationship.

As some couples did not live together, we checked whether couples’ cohabitating status affected our results. Therefore, we conducted additional analyses that included only couples who were living together. Excluding non-cohabiting couples did not change the pattern of our results.

The original scale includes three more items stemming from the subdimension logistics/time together. As explained earlier, we did not include this subdimension as it might be predominantly available for work-linked couples only.

The complete results of the additional analyses are available upon request from the first author.

References

Ackerman, R. A., Donnellan, M. B., & Kashy, D. A. (2011). Working with dyadic data in studies of emerging adulthood: Specific recommendations, general advice, and practical tips. In F. D. Fincham & M. Cui (Eds.), Advances in personal relationships: Romantic relationships in emerging adulthood (pp. 67–97). Cambridge University Press.

Ashforth, B. E., Kreiner, G. E., & Fugate, M. (2000). All in a day's work: Boundaries and micro role transitions. Academy of Management Review, 25(3), 472–491. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2000.3363315 .

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2013). The spillover-crossover model. In J. G. Grzywacz & E. Demerouti (Eds.), New frontiers in work and family research (pp. 54–70). Psychology Press.

Bennett, A. A., Bakker, A. B., & Field, J. G. (2018). Recovery from work-related effort: A meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(3), 262–275. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2217 .

Bolger, N., Zuckerman, A., & Kessler, R. C. (2000). Invisible support and adjustment to stress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(6), 953–961. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.6.953.

ten Brummelhuis, L. L., Haar, J. M., & van der Lippe, T. (2010). Crossover of distress due to work and family demands in dual-earner couples: A dyadic analysis. Work & Stress, 24(4), 324–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2010.533553 .

Cropley, M., & Millward Purvis, L. (2009). How do individuals ‘switch-off’ from work during leisure? A qualitative description of the unwinding process in high and low ruminators. Leisure Studies, 28(3), 333–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614360902951682 .

Cutrona, C. E. (1990). Stress and social support—In search of optimal matching. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 9(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1990.9.1.3 .

Derks, D., ten Brummelhuis, L. L., Zecic, D., & Bakker, A. B. (2014a). Switching on and off …: Does smartphone use obstruct the possibility to engage in recovery activities? European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 23(1), 80–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2012.711013 .

Derks, D., van Mierlo, H., & Schmitz, E. B. (2014b). A diary study on work-related smartphone use, psychological detachment and exhaustion: Examining the role of the perceived segmentation norm. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 19(1), 74–84. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035076 .

Etzion, D., Eden, D., & Lapidot, Y. (1998). Relief from job stressors and burnout: Reserve service as a respite. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(4), 577–585. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.83.4.577 .

Ferguson, M., Carlson, D., Kacmar, K. M., & Halbesleben, J. (2016). The supportive spouse at work: Does being work-linked help? Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 21(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039538 .

Friedman, R., Myers, P., Krass, S., & Benson, H. (1996). The relaxation response: Use with cardiac patients. In R. Allan & S. S. Scheidt (Eds.), Heart & mind: The practice of cardiac psychology (1st ed., pp. 363–384). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10210-013 .

Fritz, C., Park, Y., & Shepherd, B. R. (2019). Workplace incivility ruins my sleep and yours: The costs of being in a work-linked relationship. Occupational Health Science, 3(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41542-018-0030-8 .

Fritz, C., Yankelevich, M., Zarubin, A., & Barger, P. (2010). Happy, healthy, and productive: The role of detachment from work during nonwork time. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(5), 977–983. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019462 .

Gable, S. L., Reis, H. T., Impett, E. A., & Asher, E. R. (2004). What do you do when things go right? The intrapersonal and interpersonal benefits of sharing positive events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(2), 228. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.2.228 .

Gleason, M. E. J., Iida, M., Bolger, N., & Shrout, P. E. (2003). Daily supportive equity in close relationships. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(8), 1036–1045. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167203253473 .

Greenhaus, J. H., & Powell, G. N. (2006). When work and family are allies: A theory of work-family enrichment. Academy of Management Review, 31(1), 72–92. https://doi.org/10.2307/20159186 .

Grimm, K. J., Ram, N., & Estabrook, R. (2017). Growth modeling: Structural equation and multilevel modeling approaches. Guilford Press.

Hahn, V. C., Binnewies, C., & Haun, S. (2012). The role of partners for employees' recovery during the weekend. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(2), 288–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.12.004 .

Hahn, V. C., Binnewies, C., Sonnentag, S., & Mojza, E. J. (2011). Learning how to recover from job stress: Effects of a recovery training program on recovery, recovery-related self-efficacy, and well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 16(2), 202–216. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022169 .

Hahn, V. C., & Dormann, C. (2013). The role of partners and children for employees' psychological detachment from work and well-being. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(1), 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030650 .

Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J.-P., Paustian-Underdahl, S., & Westman, M. (2014). Getting to the “COR”. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1334–1364. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314527130 .

Halbesleben, J., Wheeler, A. R., & Rossi, A. M. (2012). The costs and benefits of working with one's spouse: A two-sample examination of spousal support, work–family conflict, and emotional exhaustion in work-linked relationships. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(5), 597–615. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.771 .

Halbesleben, J., Zellars, K. L., Carlson, D., Perrewé, P. L., & Rotondo, D. (2010). The moderating effect of work-linked couple relationships and work–family integration on the spouse instrumental support-emotional exhaustion relationship. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15(4), 371–387. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020521 .

Haun, V. C., Haun, S., & Himmel, T. (2017). Benefits and drawbacks of partner social support in dual earner couples’ psychological detachment from work. Wirtschaftspsychologie, 19(3), 51–63.

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513 .

Hobfoll, S. E. (1998). Stress, culture, and community: The psychology and philosophy of stress. The Plenum series on stress and coping. Plenum Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-0115-6 .

Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology, 50(3), 337–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00062 .

Hobfoll, S. E. (2002). Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Review of General Psychology, 6(4), 307–324. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.6.4.307 .

Hobfoll, S. E. (2011). Conservation of resource caravans and engaged settings. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 84(1), 116–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.2010.02016.x .

Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J.-P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 103–128. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640 .

Hyatt, H. (2015). Co-working couples and the similar jobs of dual-earner households (Working paper series CES-15-23). https://www2.census.gov/ces/wp/2015/CES-WP-15-23.pdf

Janning, M. (2006). Put yourself in my work shoes: Variations in work-related spousal support for professional married coworkers. Journal of Family Issues, 27(1), 85–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X05277811 .

Kenny, D. A., Kashy, D. A., & Cook, W. L. (2006). Dyadic data analysis. The Guilford Press.

Kinnunen, U., Rantanen, J., de Bloom, J., Mauno, S., Feldt, T., & Korpela, K. (2016). The role of work–nonwork boundary management in work stress recovery. International Journal of Stress Management, 23(2), 99–123. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039730 .

Kline, R. B. (Ed.). (2016). Methodology in the social sciences. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (fourth edition). Guilford Press.

Kreiner, G. E. (2006). Consequences of work-home segmentation or integration: A person-environment fit perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(4), 485–507. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.386 .

Kreiner, G. E., Hollensbe, E. C., & Sheep, M. L. (2009). Balancing borders and bridges: Negotiating the work–home interface via boundary work tactics. Academy of Management Journal(52), 704–730. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2009.43669916 .

Martin, L. L., & Tesser, A. (1996). Some ruminative thoughts. In R. S. Wyer (Ed.), Advances in social cognition: Vol. 9. Ruminative thoughts (pp. 1–47). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Meijman, T. F., & Mulder, G. (1998). Psychological aspects of workload. In P. J. D. Drenth, H. Thierry, & C. J. de Wolff (Eds.), Handbook of work and organizational psychology (pp. 5–33). Psychology Press.

Moen, P., & Sweet, S. (2002). Two careers, one employer: Couples working for the same corporation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61(3), 466–483. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2002.1886 .

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998-2012). Mplus User's Guide. Seventh Edition. Muthén & Muthén.

Nadler, A., & Jeffrey, D. (1986). The role of threat to self-esteem and perceived control in recipient reaction to help: Theory development and empirical validation. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 19, pp. 81–122). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60213-0 .

Newman, D. B., Tay, L., & Diener, E. (2014). Leisure and subjective well-being: A model of psychological mechanisms as mediating factors. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(3), 555–578. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9435-x .

Nippert-Eng, C. E. (1996). Home and work: Negotiating boundaries through everyday life. University of Chicago Press.

OECD. (2011). Doing better for families. http://www.oecd.org/social/family/doingbetter

OECD. (2017). How do partners in couple families share paid work? http://www.oecd.org/gender/data/how-do-partners-in-couple-families-share-paid-work.htm

Park, Y., & Fritz, C. (2015). Spousal recovery support, recovery experiences, and life satisfaction crossover among dual-earner couples. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(2), 557–566. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037894 .

Park, Y., Fritz, C., & Jex, S. M. (2011). Relationships between work–home segmentation and psychological detachment from work: The role of communication technology use at home. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 16(4), 457–467. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023594 .

Park, Y., & Haun, V. C. (2017). Dual-earner couples' weekend recovery support, state of recovery, and work engagement: Work-linked relationship as a moderator. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(4), 455–466. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000045 .

Rexroth, M., Feldmann, E., Peters, A., & Sonntag, K. (2016). Learning how to manage the boundaries between life domains. Zeitschrift Für Arbeits- Und Organisationspsychologie, 60(3), 117–129. https://doi.org/10.1026/0932-4089/a000197 .

Rothbard, N. P., Phillips, K. W., & Dumas, T. L. (2005). Managing multiple roles: Work-family policies and individuals’ desires for segmentation. Organization Science, 16(3), 243–258. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1050.0124 .

Rusconi, A., & Solga, H. (2007). Determinants of and obstacles to dual careers in Germany. Zeitschrift Für Familienforschung, 19(3), 311–336. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-58150.

Smith, J. C. (2005). Relaxation, meditation, and mindfulness: A mental health practitioner's guide to new and traditional approaches. Springer Publishing Co.

Sonnentag, S. (2018). The recovery paradox: Portraying the complex interplay between job stressors, lack of recovery, and poor well-being. Research in Organizational Behavior, 38, 169–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2018.11.002 .

Sonnentag, S., Binnewies, C., & Mojza, E. J. (2008). "did you have a nice evening? " a day-level study on recovery experiences, sleep, and affect. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(3), 674–684. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.3.674 .

Sonnentag, S., & Fritz, C. (2007). The recovery experience questionnaire: Development and validation of a measure for assessing recuperation and unwinding from work. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12(3), 204–221. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.12.3.204 .

Sonnentag, S., & Fritz, C. (2015). Recovery from job stress: The stressor-detachment model as an integrative framework. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(S1), S72–S103. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1924 .

Sonnentag, S., Kuttler, I., & Fritz, C. (2010). Job stressors, emotional exhaustion, and need for recovery: A multi-source study on the benefits of psychological detachment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 76(3), 355–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2009.06.005 .

Sonnentag, S., Venz, L., & Casper, A. (2017). Advances in recovery research: What have we learned? What should be done next? Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 365–380. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000079 .

Steed, L. B., Swider, B. W., Keem, S., & Liu, J. T. (2019). Leaving work at Work: A Meta-Analysis on Employee Recovery From Work. Journal of Management, Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206319864153 .

Stetter, F. (1998). Was geschieht, ist gut. Entspannungsverfahren in der Psychotherapie [What happens is good. Relaxation techniques in Psychotherapy]. Psychotherapeut, 43(4), 209–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002780050118.

Tremmel, S., Sonnentag, S., & Casper, A. (2018). How was work today? Interpersonal work experiences, work-related conversations during after-work hours, and daily affect. Work & Stress, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2018.1496158 .

Volmer, J., Binnewies, C., Sonnentag, S., & Niessen, C. (2012). Do social conflicts with customers at work encroach upon our private lives? A diary study. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 17(3), 304–315. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028454 .

Weigelt, O., & Syrek, C. J. (2017). Ovsiankina's great relief: How supplemental work during the weekend may contribute to recovery in the face of unfinished tasks. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(12). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14121606 .

Wepfer, A. G., Allen, T. D., Brauchli, R., Jenny, G. J., & Bauer, G. F. (2018). Work-life boundaries and well-being: Does work-to-life integration impair well-being through lack of recovery? Journal of Business and Psychology, 33(6), 727–740. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-017-9520-y .

Wethington, E., & Kessler, R. C. (1986). Perceived support, received support, and adjustment to stressful life events. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 27(1), 78. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136504 .

Williamson, G. M., & Clark, M. S. (1989). Providing help and desired relationship type as determinants of changes in moods and self-evaluations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(5), 722–734. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.56.5.722 .

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Walter, J., Haun, V.C. Work-Related Spousal Support and Recovery Experiences among Dual-Earner Couples - Work-Linkage as Moderator. Occup Health Sci 4, 333–355 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41542-020-00066-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41542-020-00066-1