Abstract

Despite much progress in the research on pivots as a response to crisis, the nature of temporary pivots remains unclear. This article investigates how a venture responded to the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic by performing a temporary pivot. Drawing on an inductive, longitudinal case study of the fast-growing young venture “Gazelle,” we developed a process model of temporary pivots that encompasses three phases: what evokes a temporary pivot; how it is enacted; and what effects it has on the venture. Our findings suggest that temporary pivots require effectual decision-making and the reversibility of changes made. Our research contributes to the growing literature on pivoting by conceptualizing the temporary pivot as a short-term entrepreneurial response to exogenous shocks and part of a long-term strategy of perseverance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The COVID-19 crisis had a global impact on firms and their business models. Notably, new ventures with scarce resources and diminishing sales faced a liquidity and, ultimately, survival threat (Kuckertz et al. 2020). Since new ventures are affected by “liabilities of newness” (Stinchcombe 1965) and “liabilities of smallness” (Aldrich and Auster 1986), they are unlikely to survive by applying defensive crisis responses. Unlike more established firms, they lack the ability to adopt a pure retrenchment or persevering strategy (Wenzel et al. 2020) over an extended period without new revenue streams (Clauss et al. 2022; Guckenbiehl and Corral de Zubielqui 2022). These ventures face the pressure of making swift decisions amid high uncertainty, driven by the need to navigate the unknown duration of the crisis (Sanasi and Ghezzi 2022). However, “smallness” permits new ventures to be more agile and flexible, allowing them to rapidly adapt to market changes (Katila and Shane 2005). The close-knit nature of small teams fosters better collaboration and the exchange of ideas; consequently, flexible and adaptable structures allow new ventures to be more innovative (Mintzberg 1989). In acute crisis scenarios, innovating seems to be the most viable response to a crisis (e.g., Klyver and Nielsen 2021; Lee and Trimi 2020; Morgan et al. 2020; Wenzel et al. 2020). Especially when the crisis also creates new opportunities for ventures, striking a new path may help combat the crisis (Clampit et al. 2021; Manolova et al. 2020; Miklian and Hoelscher 2021).

In the entrepreneurship context, one approach to innovation is “pivoting.” A pivot entails the rapid transformation of a new venture’s current business model because it is no longer viable due to an actual or potential organizational failure (Boddington and Kavadias 2018; Grimes 2018; Hampel et al. 2020; Kirtley and O’Mahony 2020; McDonald and Gao 2019; Ries 2011; Teece 2018). As such, pivots differ from other organizational changes, such as optimization (Flechas Chaparro and de Vasconcelos Gomes 2021) or diversification (Rumelt 1982).

Past studies have investigated pivots as a response to crises, such as COVID-19, or unexpected events (Berends et al. 2021; Manolova et al. 2020; Sanasi and Ghezzi 2022). However, “entrepreneurship researchers have not actually determined whether most firms pivot from necessity, or pursue new opportunities arising from an exogenous shock or whether the pivoting decision is based on a combination of such factors” (Morgan et al. 2020, p. 375). Since high time constraints and elevated uncertainty force ventures to act swiftly, a pivot triggered by an exogenous shock is less about repositioning and progressing a venture than it is about devising a temporary crisis resolution strategy to endure the turmoil and eventually revert to the original business model. We therefore argue that the understanding of pivoting as a form of innovating is less applicable in crises, where the emphasis is often on swift adaptation and survival rather than pursuing novel and transformative changes. Indeed, the literature calls for further exploration of the nuanced dynamics of how pivoting functions as a response to crises, particularly in terms of its distinctiveness from non-crisis situations (Dushnitsky et al. 2020; Morgan et al. 2020; Sanasi and Ghezzi 2022).

Since crises are transient phenomena with discernible beginnings and ends, young ventures need temporary solutions to sustain themselves throughout the crisis duration. The expectation is that the venture’s original business model will regain its viability post-crisis. We thus propose the concept of a “temporary pivot.” The essence of temporary pivots lies in preserving resources and capabilities to ensure the reversion to the business model after the crisis subsides. Unlike further development or optimization of the business model, temporary pivots involve a transitory alteration to sustain the original model over the long term. Consequently, we ask: How can ventures leverage temporary pivots as an entrepreneurial response to crisis?

To answer our research question, we present a process study of the young venture “Gazelle,” which temporarily transformed its business model in response to the COVID-19 crisis. It not only adapted or changed parts of its business model but entered an entirely new market, leveraging a new business opportunity. Based on our analysis, we developed a temporary pivot model outlining what evoked the pivot, how Gazelle enacted it, and what effects it had on the venture. The temporary pivot enabled the venture to resume its original business model after the crisis without significant structural changes.

We make two contributions to scholarship on pivoting and entrepreneurial responses to crises: First, we introduce the temporary pivot as a distinct form of pivoting aimed not at repositioning the venture but at responding to an exogenous shock; i.e., bridging a crisis as a temporary solution. With the concept of the temporary pivot, we heed the call of Dushnitsky et al. (2020) for further research on the heterogeneous nature of entrepreneurial responses to crises. We propose that temporary pivots are a suitable crisis response for young ventures and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) for which an exclusive retrenchment or perseverance strategy is not an option due to a lack of resources but which, at the same time, wish to continue with their existing business model beyond the crisis. We suggest that taking the temporality of the crisis into account helps to uncover the interplay between short-term crisis responses and long-term strategic objectives (Kraus et al. 2020). As opposed to clearly separating pivoting from persevering (cf. Berends et al. 2021; Flechas Chaparro and de Vasconcelos Gomes 2021; Wenzel et al. 2020), we understand temporary pivots as part of a long-term perseverance strategy, which “relates to measures aimed at sustaining a firm’s business activities” (Wenzel et al. 2020, p. V9).

Second, our study contributes to the debate on entrepreneurial crisis responses in general by exploring the interrelation between different crisis response concepts when considering the temporal dimension. Our case challenges the binary choice between pivoting and persevering (Berends et al. 2021), highlighting that ventures can adjust temporal commitments and continue their past, even when they choose a “distant” pivot that at least partly requires changes of their relational commitments. In this light, pivoting and persevering can intersect as a sequential crisis response. Building on the idea of narrow and exploratory perseverance by Muehlfeld et al. (2017), we show that temporary pivots can be a form of exploratory perseverance, which entails a venture preserving the current business while temporarily enacting new opportunities at the same time. With this approach, we further develop the idea that crisis response strategies can be combined (Kraus et al. 2020) and that they can be “narrow” or “broad” over time (Klyver and Nielsen 2021).

2 Theoretical Background

The COVID-19 pandemic has ushered in a period of unprecedented global disruption, testing the resilience and adaptability of entrepreneurs across industries. Especially young ventures and SMEs faced the pressing imperative of responding strategically to evolving challenges (Cowling et al. 2020; Kuckertz et al. 2020; Trunk and Birkel 2022). In the midst of uncertainty, two distinct entrepreneurial responses surfaced as essential strategies: pivoting and persevering (Berends et al. 2021). Both are “potentially effective strategic responses to crisis in the medium and long(er) run, […] however, essentially build on the availability of slack resources, whether internally or externally, which may become scarce rather quickly in times of crisis” (Wenzel et al. 2020, p. V15). Particularly for young ventures, the limited reservoir of resources and operational experience can render the exclusive reliance on perseverance problematic (Agusti et al. 2021). Persevering (i.e., maintaining a course of action) can be disadvantageous because of market disruption, missed opportunities for adaptation and innovation, increased competitive risks, and stakeholder expectations for agility and responsiveness. Pivoting can be more beneficial in this case because young ventures can strategically realign their offerings, resources, and activities to seize new growth avenues or fill emerging gaps in the market (Manolova et al. 2020; Morgan et al. 2020; Sanasi and Ghezzi 2022). This responsiveness to changing circumstances can enhance the venture’s resilience and increase its chances of surviving and thriving in the face of adversity.

However, the different crisis responses to COVID-19 should not be viewed as strictly separate from one another, because firms can combine them (Kraus et al. 2020). Additionally, during dynamic and unforeseeable crises, the temporal dimension of crisis responses gains prominence (Berends et al. 2021). The effectiveness of various strategies, even when combined, is intricately tied to the sequence, timing and temporality they adopt (Klyver and Nielsen 2021). As Morgan et al. (2020, p. 376) illustrate, we should be aware of the “dangers inherent in trying to develop the one-size-fits-all approach to deal with exogenous shocks.” The determinants guiding the choice of a crisis response are manifold, and though some insights have emerged, further research is needed to comprehensively illuminate this complex landscape (Bingham et al. 2007; Dushnitsky et al. 2020; Knudsen and Lien 2015; Zheng and Mai 2013). “A focus here should be on research into the medium- to long-term change and adaptation of the strategies. The question arises whether companies […] will continue to pursue the same strategies after [the crisis] is over” (Kraus et al. 2020, p. 1082). Additionally, Kuckertz et al. (2020, p. 3) for example, explain that innovative startups should “embrace iterative and flexible approaches” to reacting to crises. Consequently, we explore the diversity and nuances of pivoting as a response to crisis; i.e., how pivots might be combined with other approaches (e.g., persevering) or adapted over time, and how they differ from pivots in non-crisis situations.

2.1 The Concept of “Pivoting”

Recently, pivoting has become a fruitful topic for research (Berends et al. 2021; Hampel et al. 2020; Kirtley and O’Mahony 2020; McDonald and Gao 2019) after having existed in practice for some time (Arteaga and Hyland 2013; Blank and Dorf 2012; Maurya 2012). Ries (2011, p. 149) coined the term “pivot,” defining it as a “strategic course correction of a young venture to test a new fundamental hypothesis about a product, business model or engine of growth.” In contrast to more established concepts, such as strategic change (e.g., Greenwood and Hinings 1996) or business model innovation (e.g., Chesbrough 2010), pivoting lacks a consistent definition within the literature. As Flechas Chaparro and de Vasconcelos Gomes (2021) recently summarized, scholars have used the term “pivot” when referring to a type of change (Axelson and Bjurström 2019; Camuffo et al. 2020; Tekic and Koroteev 2019), a type of strategic decision (Hampel et al. 2020; Pillai et al. 2020), a mechanism related to correction or replacement in case of failure (Conway and Hemphill 2019; Leatherbee and Katila 2020; McMullen 2017; Shepherd and Gruber 2020), a process or an event (Camuffo et al. 2020; Hampel et al. 2020; Ghezzi 2019) and a state or condition (Bahrami and Evans 2011). We agree that pivots should be understood as processes instead of one-time events since they unfold over time and include consecutive events, decisions and actions (Flechas Chaparro and de Vasconcelos Gomes 2021; Ghezzi 2019; Hampel et al. 2020; Sanasi and Ghezzi 2022). A pivot is related to an entrepreneurial decision mainly occurring under the conditions of uncertainty and resource constraints. A pivot is a more radical version of strategic change (Hampel et al. 2020) and happens in a somewhat unplanned manner; entrepreneurs must take actions quickly to exploit “unexpected windows of opportunity” (Hoffman and Casnocha 2013, p. 71). For new ventures, such a change is not unusual. With their simple structure (Mintzberg 1989), they can react flexibly and rearrange their resources and capabilities more quickly than large companies to respond to a business opportunity (Manolova et al. 2020). Based on these considerations, we understand pivoting as seizing a new opportunity by significantly altering a venture’s business model in response to changing conditions.

In addition, scholars distinguish different types of pivots; for example, Hampel et al. (2020, p. 6) differentiate between early-stage “conceptual pivots” and later-stage “live pivots”. Early-stage pivoting is a sub-process of the “lean startup” methodology, focusing on startups (Boddington and Kavadias 2018; Ghezzi 2019; Ries 2011). In this context, a pivot involves experimentation through testing diverse opportunities and continually optimizing the business model (Camuffo et al. 2020; Ghezzi 2019). Accordingly, Boddington and Kavadias (2018) argue that a pivot is an evolutionary process of searching to achieve a successful outcome, consisting of the four stages: ideation, prototype building, testing, and, validating and growing. The process ends with the successful validation of a venture. Similarly, Ghezzi (2019) views pivoting as a process in which a venture undertakes a series of consecutive iterations until it devises an action plan.

Later-stage pivots (on which this case focuses) are enacted by ventures that have “embarked on a particular strategic path for a sustained period” (Hampel et al. 2020, p. 48). The distinction between early-stage and later-stage pivoting is significant due to the differing dynamics they involve. A radical business model change by a later-stage venture risks disrupting relationships with key stakeholders “who may be shocked” (Hampel et al. 2020, p. 48; McDonald and Bremner 2020; McDonald and Gao 2019). For instance, stakeholders, such as user communities or employees, may have difficulties identifying with the new business approach (Hampel et al. 2020). This may lead to, for example, a lack of customer acceptance. Investors and banks may also shy away, threatening a venture’s existence, particularly if it relies on external funding. In contrast, early-stage ventures face fewer issues in this regard, given their less established relationships. Another key difference is the impact of the pivot on the venture’s image. Once the venture establishes itself on the market, communication about pivots becomes even more critical since it significantly influences relationships with supporters and key partners (McDonald and Gao 2019). Emerging external feedback can influence the venture’s actions, whether early- or later-stage (Domurath et al. 2020; Grimes et al. 2018; Hampel et al. 2020).

In addition, pivots can be distinguished based on what triggers them. Most scholars agree that, in principle, a pivot is triggered by identifying a (potential) organizational failure (Flechas Chaparro and de Vasconcelos Gomes 2021). Yet, the decisive factor in pivoting is how the (potential) organizational failure comes about—and at what speed. We distinguish between two central paths here: First, a pivot can be evoked by difficulties with the business model that accumulate over time, such as a small market niche leading to declining revenues (Hampel et al. 2020), lack of interest in the product by potential customers (Kirtley and O’Mahony 2020) or emerging technologies that threaten a firm’s offering (Pillai et al. 2020). Second, pivots can be triggered by sudden, unexpected events that threaten the current business model, such as financial crises (Berends et al. 2021) or the COVID-19 pandemic (Sanasi and Ghezzi 2022). Against the backdrop of our research interest, we will explore the characteristics of crisis-induced pivots in more detail.

2.2 Pivots in Response to Crisis

Crises result in immense temporal pressure on a venture to act and prompt the need for an immediate response (Sanasi and Ghezzi 2022). For a young venture or SME, the necessity to ensure the business model’s viability is exceptionally high (Miklian and Hoelscher 2021; Morgan et al. 2020). At the same time, there is a high level of uncertainty about how the crisis may unfold. Manolova et al. (2020, p. 489) argue that pivots in response to exogenous shocks “must simultaneously reduce risk and seize opportunities.” Ventures may even use short-term opportunities to seize potential growth prospects while conserving resources for survival during and after the crisis (Dushnitsky et al. 2020). This approach aligns with studies illustrating that resource reconfiguration post-exogenous shocks enhances performance outcomes, emphasizing the strategic value of adapting to external changes (Colombo et al. 2021; Dushnitsky et al. 2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic showed that exogenous shocks could lead ventures to radically change their business models in the short term to respond to the crisis but reverse these changes when the crisis subsided (Clauss et al. 2022; Manolova et al. 2020; Sanasi and Ghezzi 2022). Consequently, Sanasi and Ghezzi (2022, p. 6) propose “that there is a need to investigate how pivots in situations of crisis may deal with the possible temporariness of the crisis that requires firms to balance the tension between immediate survival and long-term consistency.” The need for reversibility of the pivot is a vital consideration due to the dynamic and uncertain nature of crises. Pivoting within such circumstances acknowledges the necessity for flexibility and the potential need to revert to pre-pivot conditions once the crisis subsides, especially if the newly pursued opportunity is also induced by the crisis (Manolova et al. 2020; Sanasi and Ghezzi 2022). Once the crisis has subsided, the question arises of “what happens to the [firm] when it returns to ‘business as usual’” (Morgan et al. 2020, p. 376) and whether these temporary pivots have an impact on the firm in the long run (Manolova et al. 2020). In contrast, non-crisis pivots may involve more irreversible resource commitments driven by longer-term strategic considerations (Pillai et al. 2020). These distinctions highlight how contextual urgencies influence the nature and outcomes of pivoting.

2.3 The Puzzle: how Ventures Use Temporary Pivots to Combat Crisis

Wenzel et al. (2020, p. V13) state that since “long-lasting crises leave irrevocable traces in the business landscape that render a return to the previous order impossible,” pivoting becomes a crucial and potentially necessary strategic response to ensure the long-term survival of the firm. Still, what if the return to the previous order is possible and desirable? We propose that it is necessary to distinguish between pivots that are temporary and aim to sustain existing conditions beyond the crisis and those seeking to catalyze irreversible change.

Integrating a temporal dimension offers a dynamic lens to capture the ongoing adjustments, strategic shifts and adaptations as young ventures respond to exogenous shocks (Branzei and Fathallah 2021; Doern et al. 2019). It acknowledges that the pivot decision is not a static point in time but the starting point of a continuous process of evaluation and adaptation. Crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic exhibit fluidity, causing circumstances to change rapidly and unexpectedly (Shepherd 2020). Ventures must make decisions based on current information at the outset of the crisis. However, the evolving nature of crises introduces a dynamic element with rapidly shifting and unpredictable circumstances, necessitating ongoing adjustments beyond the initial decision-making phase. Plans set in motion at one point may need to be refined, revised or even reversed as new information emerges or circumstances evolve.

To better understand the nature of temporary pivots and how ventures can ensure the reversibility of their business model, we ask the following research question: How can ventures leverage temporary pivots as an entrepreneurial response to crisis?

3 Methods

To answer our research question, we conducted a longitudinal case study of how the venture “Gazelle” (a pseudonym) performed a temporary pivot in the period from January 2020 to June 2021 as a response to the COVID-19 crisis.

3.1 Case Selection

We chose the case of Gazelle as it illustrates the whole process of a temporary pivot, from evocation, to enactment, to subsequent effects. Our study benefited from comprehensive data access facilitated by an existing research project, enabling us to engage extensively with the venture. Indeed, a unique strength of single case studies is high exposure, which refers to “the number of hours the researcher expects to spend either interviewing individuals or conducting observation” (Small and Calarco 2022, p. 157).

We started observing Gazelle in January 2020. As we saw in real-time how the COVID-19 pandemic challenged the firm’s existing business model and how managers and employees reacted to the emerging fundamental crisis, we started to chronicle the process and collect data. Over time, it became apparent that we were observing an “extreme case” (Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007; Starbuck 2006) of a pivot process driven by a disruptive event. Studying an extreme case such as Gazelle’s temporary pivot can enhance theory development and lay the groundwork for future research as it provides a rich, in-depth exploration of how a new venture responds to a crisis, challenging existing theoretical assumptions about crisis response strategies and enabling the discovery of new insights (Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007; Eisenhardt 2021; Volmar and Eisenhardt 2020). To ensure a thorough analysis, we adopted an in-depth and longitudinal case study approach, which allowed us to gather contextually rich data and understand the intricate social dynamics at play during the pivot process (Gehman et al. 2018; Yin 2009).

3.2 Empirical Context

Gazelle was founded in 2018 and manufactures innovative, award-winning consumer tech products such as smartphone accessories and headphones. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Gazelle employed about 80 people at its headquarters in Germany, and another 60 employees worked for a joint venture in China responsible for sourcing and manufacturing. Since its foundation, the young venture has been on a solid growth trajectory and is mainly financed by venture capital. Gazelle’s revenue doubled in the first two years and was in the double-digit millions in 2019. The venture has three business units: 1) the co-branding segment, in which Gazelle markets high-quality promotional items and custom product designs; 2) the retail segment, in which the venture sells its products to resellers; 3) the online segment, in which Gazelle sells its products directly to end consumers via multiple online marketplaces. Before the COVID-19 crisis, Gazelle focused on in-flight shopping and airport shop sales, delivering its products to 55 countries, 25 airlines and more than 50 airport shops worldwide. Gazelle’s strategy was strongly growth-oriented and focused on differentiating its products from competitors and diversifying into new market opportunities.

At the end of January 2020, Gazelle was directly affected by the COVID-19 crisis. The joint venture discontinued production because of the increasing spread of the coronavirus in China. A few weeks later, measures adopted by Germany and many other countries to impede the spread of the pandemic led to a sharp decline in Gazelle’s sales. At the same time, a new business opportunity emerged as Gazelle began receiving requests from external partners to provide medical protective equipment. Gazelle’s management subsequently decided on a radical organizational change to avoid substantial cost-cutting measures (such as layoffs) and test the potential opportunity (see Fig. 1 for timeline). By rapidly reallocating existing resources and activating its network in China, Gazelle began to import face masks, which were in short supply in Germany and Europe. However, the pivot was intended not to be permanent but to be a temporary solution to bridge the crisis.

3.3 Data Collection

To answer our research question and triangulate our findings we used three main strategies to collect qualitative data: semi-structured interviews, participant observation and secondary data (see Table 1).

3.3.1 Interviews

We derived key data from 27 in-depth, semi-structured interviews conducted in two periods in 2020 and 2021 (see Fig. 1) to examine the venture’s developments over time. We interviewed Gazelle’s chief executive officer (CEO), co-founders and management, the manager of the China-based joint venture, employees from all departments, and business partners. We used prior informal interviews to determine the individuals most involved in organizing the temporary pivot. To understand the societal need for masks at the beginning of the pandemic, we also spoke to charities that received mask donations from Gazelle. Table 1 shows a list of interviewees. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. We conducted interviews until we achieved theoretical saturation, denoting the point at which no new patterns or insights emerge (Glaser and Strauss 2009). The interviews lasted approximately 40 min on average and were primarily conducted in person, except for a few which were conducted via telephone or Skype.

3.3.2 Participant Observation

The first author was a participant-observer, working part-time as an unpaid intern within the business development team at Gazelle for ten months (July 2020 to April 2021). She engaged in approximately 134 h of participant observation at the office and joined meetings and social activities with the team and Gazelle’s management. The participant observation enabled formal interviews, informal conversations and valuable insights that allowed us to understand Gazelle’s pivot process and its impact on the venture in detail. In particular, it allowed us to observe and document the return to the original business model and the effects of the temporary pivot in real time. Approximately half of the time, observations could be made on-site at Gazelle’s headquarters, and during the other half, observations were made remotely via emails, video conferencing and phone calls due to home office regulations. The first author documented the participant observations through field notes in a diary format. She took additional notes over the period to reflect upon the critical dynamics of the pivot process.

3.3.3 Secondary Data

Third, we collected and analyzed relevant archival data to chronicle what evoked the temporary pivot, how Gazelle enacted it, and how it affected the venture. Starting in January 2020, we communicated regularly with members of Gazelle’s management, such as the Head of human relations (HR), the chief operating officer (COO) and the CEO’s assistant via email and phone. We collected 72 pages of internal documents, including these emails. Internal emails, documents and noted phone conversations are cited as “personal communication.” To better understand Gazelle’s actions and how it communicated these, we collected 46 newsletters that the venture sent its employees and business partners, as well as 83 social media posts (Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn), 15 pages of public data, such as web pages, 40 min of social media video footage (YouTube campaign videos and Instagram Live) and 47 pages of press articles and releases. Finally, to gain a thorough contextual understanding of the case, we also collected and reviewed scientific articles, institutional reports (e.g., from the World Health Organization) and documentary film footage related to the COVID-19 pandemic and the global face mask trade.

3.4 Data Analysis

We were interested in how Gazelle leveraged the temporary pivot as an entrepreneurial response to crisis. Our analysis followed an inductive, explorative approach that builds upon the interaction between data, existing theoretical frameworks in the literature, and emerging theory (Maxwell 2013; Orton 1997). Inductive methods are well suited to study process questions (Glaser and Strauss 2009; Langley 1999). We used an iterative process of collecting, coding and categorizing “empirical material as a resource for developing theoretical ideas” (Alvesson and Kärreman 2011, p. 12) to identify key themes and construct a temporary pivot model. This process also entailed linking categories to emerging themes and reflecting them with existing frameworks (Maxwell 2012, 2013; Strauss and Corbin 1998). We adhered to the guidelines specified by Strauss and Corbin (1998) for constant comparison techniques, in which the collection of the data is iteratively intertwined with the data’s actual analysis. For the coding process, we used the software MAXQDA.

We analyzed the data in three steps: First, we developed a chronology depicting the events of the pivot process to acquire a comprehensive understanding of the sequence of occurrences (Langley 1999; see Fig. 1). We conducted open coding to anchor our process study in the phenomenon. In this phase, our coding was primarily focused on interviews with Gazelle’s management, participant observation by the first author and archival data generated by Gazelle, including newsletters and press releases. Employing a sentence- and paragraph-level coding approach, we initially identified codes for enacting the pivot, such as “bridge the loss in revenues” or “build on existing networks and collaborate.” In total, we identified 26 first-order codes, at which we arrived after multiple iterations and the removal of repetitive codes. We show quotes for each first-order code across the findings and in a supplementary data table (see Table 2).

In the second step, we followed Langley’s (1999) recommendations by using a combination of “temporal bracketing” and “visually mapping” to distinguish between the distinct phases of the pivot process. This allowed us to display how specific conditions and events unfolded. We progressed from intensely delving into data to dynamically cycling between data, theory and emergent patterns, shifting our focus from grounding to organizing strategies (Langley 1999). Through this approach, we turned the first descriptive codes (e.g., “react rapidly to changing market developments”; “change and adapt any potential plans”; and “build on existing networks and collaborate”) into fewer, more conceptually abstract ones (e.g., “effectual decision-making”) (Strauss and Corbin 1998). Through this analysis, we ultimately arrived at ten second-order themes.

In the third step, we discerned the three higher-level theoretical dimensions that governed our data. The three overarching dimensions (namely, first “evoke”; second “enact”; and third “effect”) simultaneously stand for the three phases of the temporary pivot process. The first dimension describes the evoking events that triggered the temporary pivot. The second dimension concerns Gazelle’s actions; i.e., how the venture enacted the temporary pivot. The third dimension summarizes how the temporary pivot impacted Gazelle after the venture returned to its original business. To increase the rigor of our analysis, we engaged in multiple rounds of cross-checking the critical aspects of the process with additional information gained from other data sources (Gioia et al. 2013). We devised the following coding structure (see Fig. 2).

In line with an inductive approach, coding does not produce theory without an “uncodifiable creative leap” (Langley 1999, p. 691). We discussed possible, more abstract categories and reflected on existing literature from different fields. To increase the validity of our study, we exploited various opportunities to receive feedback on preliminary findings at different stages of the study (e.g., member check). Finally, we visually mapped our findings, showing the relationships between external factors, the entrepreneurial response and outcomes over time. We iteratively refined these models until we formulated a comprehensive process model elucidating the underlying mechanisms of the temporary pivot (Langley 1999; York et al. 2016).

4 Case Study: the Temporary Pivot at Gazelle

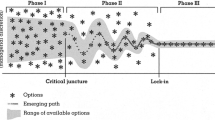

The case unfolds over three phases (see Fig. 3 for our model): Phase 1 focuses on how the temporary pivot was evoked; phase 2 is about the enactment of the temporary pivot; phase 3 describes how the temporary pivot affected the venture. Each phase explicitly addresses the mechanisms that distinguish temporary pivots as a response to crisis from non-temporary pivots.

4.1 Phase 1: Evoking the Temporary Pivot

Expect (potential) failure due to exogenous shock. The first event that directly alerted Gazelle to a potential crisis was the lockdown in Wuhan, China, starting on January 23, 2020. Gazelle’s CEO was informed by business partners in China that it was unclear whether the joint venture’s work would resume after the Chinese New Year celebrations: “Everything is no longer normal with such great panic” (Interview Joint Venture Manager). Curfews and travel restrictions were increasingly imposed across China as COVID-19 cases rose quickly during February. Initially, the plan was to restart production as soon as possible, but when the first COVID-19 cases occurred in Europe, it became apparent that the spread of the coronavirus would directly impact Gazelle’s business. The joint venture manager explained: “After Chinese New Year, it was several weeks, even months, during which the joint venture had no orders.”

COVID-19 had multiple impacts on all of Gazelle’s business segments. The co-branding segment, which accounted for about 75% of the revenues, slowed down the most since “all trade shows and events through which Gazelle’s clients usually purchased co-branded promotional items were cancelled” (personal communication, May 15, 2020).

“Our sales drivers are companies that use such promotional products in the ‘incentive sector’: trade fairs, events and so on. This is completely cancelled by Corona and accordingly the market collapsed further and further.” (Interview Gazelle CSO & Co-Founder)

The international stationary trade was also severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic due to lockdowns and air travel restrictions, leading to a sharp decline in Gazelle’s in-flight shopping and airport store sales. As a result, Gazelle’s management realized that the venture was on the brink of failure because its current business model was no longer viable under the COVID-19 pandemic. The limited financial resources put pressure on them to act quickly. As a young venture, Gazelle could not draw on accumulated capital to bridge the crisis “without having to take extreme cost-cutting measures” (Interview CEO & Founder). In addition, there was high uncertainty about future developments. For Gazelle’s management, it was unclear how severe and prolonged the looming crisis would be. Therefore, the COVID-19 crisis as an exogenous shock served as a primary trigger for Gazelle’s temporary pivot (see Fig. 3).

Decide to enact pivot opportunity. Since the coronavirus mainly spreads via aerosols, face masks are essential in the fight against COVID-19 (Gereffi 2020). At the beginning of the pandemic, China was the leading producer of masks, accounting for approximately half of world production (OECD 2020). Gazelle’s managing team saw a significant crisis looming over the venture and started seeking different opportunities to respond to the exogenous shock (see Fig. 3). In light of the unprecedented crisis, it became apparent among the management and employees: “We rapidly have to do something” (Interview Head of HR). Simultaneously, in mid-February 2020, long-time sales partners from abroad, primarily Switzerland, Spain and Italy, asked if Gazelle “could make face masks available” (Interview Employee #10Footnote 1) with their contacts in China. Initially surprised by these inquiries, the company’s leadership began to ask themselves “Why are we being contacted? Is the demand extremely high? How can we help here? Why is this even happening?” (Interview CTO & Co-Founder).

As the requests accumulated and Gazelle’s team developed an awareness of the face mask shortage across Europe, the management started to recognize the opportunity that arose from the crisis. Due to the decline in sales, many departments were operating at a labor surplus and Gazelle was able to reallocate resources and capabilities, including those of the joint venture partner, towards the face mask business:

“We have the infrastructure in China, we have here on site, a very good, agile, dynamic team, which can simply handle exactly this situation. [Existing business] was at a standstill, nobody knew where things were going at that point and that’s when we could really pivot.” (Interview CTO & Co-Founder)

The management formed a task force that quickly examined whether it would be legally, economically and logistically feasible to import and sell face masks. Besides the availability of released resources, other preconditions were not as promising, as the venture had no prior competence or track record in sourcing and distributing medical devices:

“No one was familiar with [the business], the market and our competitors. Which certificates do you actually need for masks, how must they be certified, what must be written on them […].” (Interview Employee #3).

However, the market for medical devices and personal protective equipment in Europe had turned into a “pure seller’s market” (Interview CSO & Co-Founder), where anyone who could deliver had market access; i.e., traditional barriers to entry such as reputation, customer contacts and distribution channels became irrelevant due to dramatic supply shortages. In addition, Gazelle’s founders have consistently exhibited a propensity for taking risks and possessed a high level of self-confidence. Gazelle’s CEO, for example, once told a newspaper that his motto is to “never give up” and that he wants to “accomplish great things” (Press article #15, 2017). With regard to the COVID-19 crisis and the pivot opportunity, the CTO and Co-Founder said:

“The mindset here in the company, the corporate culture, is actually not to bury our heads in the sand when faced with difficulties, but to look at how we can solve this situation […] We only ever have plan A.”

“[I]t just took a week” (Interview Head of HR) for Gazelle’s management to “la[y] opportunities side by side” (Interview CEO & Founder) and determine that the mask trade was a viable opportunity that could save the venture from significant changes, such as cost cutting or reducing working hours for the employees. Based on their positive assessment of the opportunity, the venture’s management decided to enact the pivot. “One has seen the opportunities, but also the risks,” the CEO’s assistant summarized (Interview Employee #10). Accepting those risks, Gazelle’s management rapidly proceeded with their plans to pivot. As such, the COVID-19 pandemic led the venture into crisis but simultaneously created a new business opportunity. In short, the exogenous shock played a decisive role in the decision to pivot.

4.2 Phase 2: Enacting the Temporary Pivot

Use opportunity to combat crisis. The managing team realized it could leverage its network for the mask trade and this opportunity could lead to revenues compensating for the loss in sales in the consumer tech product business. At the same time, they would address a critical societal need during the COVID-19 pandemic. Through personal contacts, the CEO and Gazelle’s managers had learned about the risks facing frontline healthcare providers working without adequate protection:

“The physician assistants, they really took their mask home, washed it, hung it up, put it on the next day, the filter doesn’t work at all, it’s broken, but they still wear that mask. It was a disaster.” (Interview CEO)

These stories motivated them “not only to get through the Corona period well [them]selves, but also to show solidarity and make the masks available, especially regionally” (Interview Employee #5). Alongside selling masks, Gazelle also launched a fundraising campaign, donating face masks, to benefit organizations supporting the homeless, cancer patients and other high-risk groups. The donations “came at exactly the right time […] when [masks] were really hard to get” (Interview Donation Recipient #2). Gazelle’s management said the company was driven by three main motivators to contribute to society: First, the venture was one of the first firms in Germany to provide masks and thus “wanted to do something good” (Interview CCO) to “fac[e] the pandemic and the lack of protective equipment” (Press article #6, 2020); second, becoming a mask supplier was an “image issue” (Interview CEO), because the CEO “wanted to be the man who simply supports the entire region […], show[ing] people, we can do this significantly faster than all the others”; third, it motivated the venture’s employees, or, as one employee summed up the charity approach: “This gives real meaning to the work” (Interview Employee #11).

Effectual decision-making. The simple organizational structure of the venture turned out to be a particular strength because it made it possible to “flexibly adapt work processes” and react rapidly to changing market developments (personal communication, April 4, 2020). Entrepreneurially oriented, Gazelle’s managing team decided to seize the mask trade opportunity despite high uncertainty and the risk of lacking knowledge about the market and product. “There was much improvisation, but in the end, it somehow worked out” (Interview Employee #4). As Gazelle received more and more orders for face masks, the venture completely pivoted, including all departments, “allowing everyone to continue to work […]. That was from one moment to the next” (Interview Head of HR). Even though Gazelle could use existing networks, processes and resources, the team also had to develop new competencies:

“And then in Sales […], we had to do training. So first we had a really technical training, where it was about facts: What is an FFP2 mask? What is an FFP3 mask? What is the difference between occupational health and safety and the medical requirements? We learned everything.” (Interview Employee #5)

Plans had to be adapted flexibly, as Gazelle constantly faced unexpected challenges. There were three main reasons for this: First, the face mask market was highly volatile at the time: “The market was extremely fast, dynamic, and it was really like the stock market, [or the] wild west” (Interview CSO & Co-Founder). Mask prices changed hourly, occasionally spiking to extreme highs. Every day, new factories and trading companies entered the market, and it became increasingly difficult to distinguish reliable from unreliable suppliers. Corruption, theft and quality defects became significant problems. “Many people threw money at fixing the mask problem. What the Chinese produced for customer A was sometimes simply sold for twice the price to customer B” (Interview CSO & Co-Founder).

Second, maintaining the supply chain became another significant challenge as the number of global cases of COVID-19 continued to rise in April 2020. Although the company could use existing structures in logistics, heavy restrictions on international air traffic repeatedly led to delivery problems. Consequently, Gazelle often could not meet delivery targets, and the logistics team had to find new delivery routes at short notice. In April, the delivery problems finally led the venture to charter its own aircraft and transport about nine million face masks to meet delivery targets of customers in Germany (Facebook Post, May 20, 2020). Gazelle had to rent additional storage capacities to store the masks because their original facility was “at 200 percent capacity” (Interview Employee #9).

Third, Gazelle’s financial risks also grew as the venture primarily paid for supplies in advance in an effort to close deals ahead of many competitors. “I have lost an awful lot of money in this whole phase […]. I did much ramp-up with my own money in the first phase” (Interview CEO & Founder). Gazelle’s management, therefore, constantly sought new investors and business partners who wanted to support the mask trade, such as Business Partner #2: “Usually doing business as one of the largest medium-sized and independent companies in the energy sector, [Business Partner #2] helps [Gazelle] prefinance respiratory protection masks” (Press statement #10).

Ensure reversibility of business model. The multiple challenges also jeopardized Gazelle as they cost significant effort and investment, although the pivot to the mask trade was intended to be a “temporary project” (Interview Employee #11). To ensure they would eventually be able to return to their original business model, Gazelle’s management had to continually evaluate their risk appetite as well as the extent of organizational change they were prepared to enact.

“We are creating a certain buffer here, of course, so that the company can continue to exist. But the goal was actually to make a cut at some point, to bring it to a close, and to move forward with [Gazelle] as soon as this crisis […] is more or less wrapped up” (Interview Co-Founder #H).

Although Gazelle considered maintaining the mask business as a longer-term “second mainstay” (Interview CCO), its main intention for the pivot was to survive the COVID-19 crisis in an effort to resume its original business afterward. As one employee put it: “We’re now going to move [Gazelle] to the back and [the face mask brand] to the front. Never completely. […] [I]t was never about somehow shutting down [Gazelle] completely” (Interview Employee #11). To ensure the reversibility of the business model, Gazelle’s management deliberately paid attention to three factors: First, as mentioned above, the mask trade was only an option because the venture could implement it with existing resources, capabilities and networks. “So, in a very short time, we completely changed our sales network, everything that we normally have, to this mask business” (Interview Employee #1). Second, Gazelle’s management prioritized job security and made it a key objective for the pivot: “The aim was to secure jobs with this new organization, with this project, and to ensure that we can emerge from the crisis stronger in the future” (Interview CTO & Co-founder). Most employees appreciated their new tasks and that they were actively employed while work was at a standstill in other companies:

“But looking back, it was really cool, it was really exciting. We also worked a lot overtime, but it was just great (…) I thought it was kind of cool that I could still keep working and I didn’t notice anything from Corona.” (Interview Employee #4)

One of the HR department’s main tasks during this period was to “keep [the employees] in a good mood” (Interview Head of HR). A third important factor to ensure the reversibility of the business model was to keep the mask business separate from the original business. “That’s why they launched the [face mask brand] Internet platform” (Press article #9). As Gazelle’s chief customer officer (CCO) described: “I then took care that we could create a whole corporate identity, a new brand, in a very short time.” The new brand name was printed on the masks and used for all business materials and websites. The marketing team also created separate social media channels for the face mask brand. The company endeavored to ensure that the new business model would not damage the existing brand or confuse consumers: “There should be a clear separation, of course. […] That was definitely always the case, that the goal was not to mix the two” (Interview Employee #10). Ultimately, these efforts to separate the old and new business models failed to achieve the desired results, as we will discuss below.

Return to original business. s the global face mask market began to stabilize in early May 2020, Gazelle’s sales team noticed “an abrupt drop in demand so that prices also collapsed” (Interview CSO & Co-Founder). Chinese companies ramped up mask production capacities. It was now possible to produce large quantities of masks due to “new factories” (Interview Joint Venture Manager). By this point, many established, well-networked competitors “who have been on the market for years” (Interview CTO & Co-Founder) were meeting demand. At the same time, COVID-19 infections in Europe and China had reached a comparatively low level, and Gazelle’s consumer tech product business began to recover from the crisis. Gazelle’s managers determined that it was time to exit the mask business, mainly due to the declining demand and retail prices:

“The market was also collapsing extremely strongly at that time. You saw every day, from one day to the next, that the price kept going down, and we also had the last batch that we delivered to [Client X], which we also delivered at a loss.” (Interview CEO & Founder)

With the recovery of the original business, it was also clear that Gazelle had to reallocate resources again: “[W]e only have one team. […] I actually need the same employee to be doing one thing, but somehow to also be doing something else at the same time” (Interview CCO). As planned, Gazelle initially had all the necessary resources to return to its original business model: “That is somehow our passion” (Interview Employee #10). The temporary pivot helped bridge the crisis (see Fig. 3); however, as outlined in the next section, the pivot had ambivalent effects on the venture.

4.3 Phase 3: Effect of the Temporary Pivot

Face negative consequences. As predicted by Gazelle’s chief sales officer (CSO), “you never get straight out of the market.” According to the CEO: “That’s always the case in an opportunistic business. When you first ramp up, you can’t get out of the market like that, you have to go out with a fast curve.” Despite the significant decline in demand, Gazelle still had large stocks of masks. The management decided to sell the remaining inventory (3.9 million masks, according to its newsletter) to an intermediary in late June, who resold them to the German Federal Ministry of Health (Gazelle Newsletter #20). Since Gazelle had already made a “smaller delivery to the government via an intermediary [in March] where [Gazelle] received payment [and] the inspection must have been positive” (Interview CSO & Co-Founder), Gazelle’s management assumed a safe deal this time as well. This time, the Federal Ministry had backed German companies with an assurance to buy masks at a fixed price under a so-called “open-house scheme” in which it issues contracts giving any interested company a right to join during the contract term, meaning that there is no selection decision between the various offers, and no exclusion (Willenbruch 2017). The German Federal Ministry of Health established this program to ensure that a sufficient quantity of masks would be quickly available in Germany. However, when Gazelle sold the masks in June, the Federal Ministry claimed that many of the masks did not meet the specified quality requirements for Germany.

Consequently, neither the intermediary nor Gazelle received payment for these masks. As of July 2023, the Federal Ministry’s claims of quality defects had still not been conclusively confirmed (cf. Newspaper article, July 14, 2023). Over time, more than 140 lawsuits were filed against the Federal Ministry by companies with similar complaints (Newspaper article, July 14, 2023). As a result, “[Gazelle] lost five million euros” (Interview CEO & Founder), which resulted in the venture’s bankruptcy.

“We are facing trouble due to defaults on payments resulting from the sale of COVID-19-related masks. Following a denied deferral request from the tax office and a credit line being called in by one of our house banks, we have filed for insolvency proceedings in self-administration.” (Gazelle Newsletter #200904)

The venture filed for bankruptcy on August 31 (Local Court Notice, August 31, 2020). Consequently, it implemented cost-cutting measures, including “la[ying] off more than ten employees” (observation, October 07, 2020), significantly reducing its vehicle fleet and vacating office space (observation, January 07, 2020). The insolvency and allegations that Gazelle had supplied defective masks to the German government also became a topic in national politics and the press:

“The affair about faulty and not legally accounted respiratory masks of the company [Gazelle] reaches the sphere of politics. Yesterday, the parliamentary group of the Green party in the state parliament filed two brief inquiries on ‘Inconsistencies in the awarding of contracts for mask deliveries by the insolvent company [Gazelle]?’” (Press Article #5)

The negative press coverage about the mask business led to reputational damage for Gazelle, but mainly at the local level. It did not have significant business-damaging effects: “We have not noticed that just because there are these articles, we now have declines in sales or something like that” (Interview Employee #10).

Expand networks. In contrast, a positive effect of the temporary pivot was that Gazelle’s managers greatly expanded their business network. “[Y]ou got in touch with a lot more partners than you would have otherwise in the regular business. So, we really made many, many exciting contacts” (Interview CTO & Co-Founder). The CSO was also convinced that the mask trade had a positive impact on their network:

“I alone have collected over 200 different contacts from customers and suppliers in a very short period of time. We have built up an extreme network of partners such as [Consulting firm X] and others.”

During the bankruptcy period, a prominent German private investor who came into contact with Gazelle during their time in the mask trade expressed interest in the venture, indicating that he was impressed by how the team had responded to the COVID-19 crisis and the flexibility of the young, dynamic team, and noting that the venture’s rapid crisis response signaled “unusual entrepreneurial foresight and an innovative spirit” (personal communication, May 11, 2021). As Gazelle’s original business model was “absolutely healthy” (Press article #8) before the pandemic, the investor expressed his appreciation for Gazelle’s return to the tech product business and took a stake in the venture (Press release, March 1, 2021). The new investment enabled the venture to restructure within a few months following a self-administered insolvency plan. The CEO summarized in spring 2021:

“We now have 50 employees despite the whole story here. And [we] are now beyond the Corona phase, […] we are debt-free, we have a new investor, we have the warehouse full of products.”

Gain new knowledge and capabilities. In addition to expanding the venture’s business network, the temporary pivot led to new knowledge and capabilities at Gazelle. Especially for the management, it was also an impetus for rethinking and reflecting on existing routines and processes:

“We have learned a lot, and, I would say, we have also questioned many things. […] When you switch back from [the mask business] to the core business, there are of course many things where you simply take a much more reflective approach.” (Interview CTO & Co-Founder)

Some employees have grown and developed because they have “taken on more responsibility” (Interview CTO & Co-Founder) during the pivot: “[Y]ou can somehow achieve a lot by adapting to new situations. […] I also trust myself to do things and say, ‘Yes, I can do that’” (Interview Employee #1). Organizational learnings and personal development led to improved processes and internal communication, such as “new forms of meetings and more transparency regarding the business situation” (observation, December 07, 2020).

Fulfilling a social need during the COVID-19 pandemic with mask donations left a lasting impression on some employees, “because [donation recipients] show you a completely different kind of gratitude than some major customers” (Interview Employee #11). These experiences were, among other things, the impetus for planning a corporate social responsibility (CSR) strategy. Gazelle’s management developed plans to make the venture “more sustainable and socially committed” (observation, March 12, 2021):

“We thought maybe we could adopt something […] towards sustainability, that we also generate donations. We are still working on making our packaging completely plastic-free […] And everything that we save there, for example, we then donate to [the World Wide Fund for Nature].” (Interview CCO)

Persevere during crisis. Even though the temporary pivot also negatively impacted Gazelle by leading to the venture’s bankruptcy, almost everyone at Gazelle agrees that it was “worth it” (Interview CTO & Co-Founder). “It has definitely paid off economically because we have had full employment here for months. […] This allowed us to bridge a lot of money and time” (Interview CCO). The initial high sales volumes of the mask business made up for sales shortfalls from the consumer tech product business, enabling Gazelle to conserve resources throughout the COVID-19 crisis and keep most employees on the payroll, even throughout the bankruptcy proceedings. “I still have my job, which I am glad about, and I think it has something to do with the masks” (Interview Employee #6). Another employee agreed: “If we hadn’t done [the face mask trade], it would have been difficult, I think, in the Corona period, to survive here without layoffs somehow” (Interview Employee #2).

Gazelle made clear that the temporary pivot was not driven by innovation but by the necessity to bridge the crisis: An internal newsletter reassured employees that “day-to-day business with our tech accessories continues as usual” (Newsletter #15). Even if this was not the case during the mask trade, it helped employees to accept the new business model as a temporary project: “[W]e’ve just mainly been building the [Gazelle] brand for years, and we want to continue to build it up. [The face mask brand] was really a temporary project here, with the purpose of offering short-term help” (Interview Employee #11). Gazelle thus enacted its temporary pivot as a means of preserving its original business while pursuing other opportunities; i.e., exploring during a state of perseverance.

4.4 Epilogue

During its time in the mask trade, Gazelle sold “over 29 million masks to about 150 different B2B customers” (personal communication, November 29, 2020). The venture donated “over 30,000 masks to ten different charities” (personal communication, November 29, 2020). In June 2021, Gazelle announced it had become a “subsidiary” of the corporation of the private investor discussed in the previous section (Press release, June 24, 2021). Gazelle’s management team remained in place. One year later, a media report indicated that Gazelle had “bought back its shares and is operating independently again with immediate effect” (Press article, June 3, 2022).

5 Discussion

Our study explores how young ventures leverage temporary pivots as an entrepreneurial response to crisis. Accordingly, we conducted a qualitative process study of Gazelle, a fast-growing manufacturer of consumer tech products that pivoted its business model towards trading personal protective equipment in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Even though the new business opportunity required a radical and effortful change, the pivot was only a temporary solution to combat the crisis. Gazelle aimed to keep its business model reversible to ensure a return to its original business once the crisis subsided. Based on this case, we developed a process model of a temporary pivot, elucidating its unique characteristics and establishing a connection with the concept of perseverance (see Fig. 3). Gazelle’s experience underscores the importance of maintaining a balance between seizing new opportunities and safeguarding the core business during a temporary pivot. Our paper contributes to research by theorizing temporary pivots as an entrepreneurial response to crisis and advancing theory on ventures’ reactions to exogenous shocks in general.

5.1 Temporary Pivot as a Response to Crisis

A temporary pivot, as opposed to a non-temporary one, implies no long-term changes or significant adaptations of the business model after returning to the original business. It contributes to sustaining the original business in the long run and facilitates a balance between immediate survival needs and the long-term imperative of maintaining a consistent strategic position and alignment. Based on the understanding of pivots as processes (Flechas Chaparro and de Vasconcelos Gomes 2021; Hampel et al. 2020; Sanasi and Ghezzi 2022), we flesh out how a temporary pivot emerges, evolves and terminates over time through an interplay of activities and events (Langley 1999; van de Ven 1992). In our case study of Gazelle, we identified three essential phases of a temporary pivot (see Fig. 3 for an overview of our process model).

The first phase involves evoking the temporary pivot due to a (potential) crisis caused by an exogenous shock, disrupting the venture’s existing business model and simultaneously presenting a new business opportunity. The kind of pivot depends on the nature of the crisis or unforeseen shock. In the context of a temporary pivot, an exogenous shock disrupts economic processes, labor markets and established business models (Li and Tallman 2011). Nevertheless, these unique challenges also offer emerging entrepreneurial opportunities, at least for some time (Morgan et al. 2020). As we have seen in the case of Gazelle, young ventures dealing with exogenous shocks must navigate high uncertainty, risk and time constraints, challenging their ability to balance contradictory demands such as exploring new opportunities while exploiting what is left of the existing business model or balancing operational retrenchment with strategic recovery (Förster et al. 2022).

As the case of Gazelle illustrates, acting promptly plays an essential role because it helps demonstrate a proactive approach to dealing with the crisis and mitigating the negative impact on the current business. In particular, acting fast to find new opportunities offsetting the old business is essential to sustain existing resources, confidence among partners, and the motivation of employees. In contrast to previous research that regards pivots as response to crisis as experimentation (Sanasi and Ghezzi 2022), Gazelle engaged in only limited experimentation or opportunity testing because of the urgency of their decision-making. This is because exploring entirely new opportunities requires resources, and during external disruptions, these resources, as in the case of Gazelle, can be significantly limited (Morgan et al. 2020). Furthermore, crisis-induced opportunities often demand quick entrepreneurial moves because “first-movers” (Lieberman and Montgomery 1988) or “early entrants” (Lambkin 1988) aim to capitalize on the market’s growth potential before competitors can take market share from them. Consequently, the initially promising returns diminish over time. In sum, our study shows that a temporary pivot necessitates rapid assessment, risk-taking and fast decision-making to mitigate the impact of the crisis on the venture and take advantage of emerging temporary windows of opportunity.

In the second phase, the temporary pivot’s enactment, the venture seizes the identified opportunity to combat the crisis (Manolova et al. 2020; Sanasi and Ghezzi 2022). As observed at Gazelle, a temporary pivot emphasizes leveraging existing resources and flexible, adaptive decision-making based on what resources are readily available to redeploy for exploring an emerging opportunity. Crisis-induced opportunities such as the emerging mask business involve ambiguities, where venture management may lack a clear vision of the end goal or the path forward (Santos and Eisenhardt 2009). Effectual decision-making (Sarasvathy 2009) adapts to these ambiguities, allowing goals and means to emerge iteratively. Effectuation, with its feedback-seeking and feedback-incorporating process, aligns well with our process-oriented study (Reymen et al. 2015). The adaptability ensures that effectual decision-making remains open, enabling the venture to capitalize on unexpected events (Chandler et al. 2011).

To enact a temporary pivot, the venture must ensure the reversibility of the new business model by using existing resources, capabilities and networks, minimizing the need for significant investments or long-term commitments (Morgan et al. 2020). This allows the venture to preserve essential resources such as its workforce, which is crucial to returning to the original business as soon as the crisis subsides. For management in particular, achieving internal cohesion and agreement on overall decisions, including the timing for reverting to the original business model, is essential. These decision-making processes are closely associated with the principles of the effectuation logic. The unforeseen disruption and subsequent uncertainty revert the firm to a state akin to an “idea phase” during venture creation. This phase necessitates a significant reliance on effectuation (Reymen et al. 2015). By showing how Gazelle utilized existing resources in a means-oriented approach during crisis, we contribute a more nuanced understanding of the role of effectuation principles in guiding new ventures in the dynamic landscape of entrepreneurial responses to crisis. Following an effectuation logic is necessary for enacting a temporary pivot.

The third phase contains the effects of the temporary pivot on the venture after the decision to return to the original business. While a temporary pivot can lead to positive outcomes, such as expanded networks and new knowledge and capabilities, it might also result in negative consequences (Morgan et al. 2020). In Gazelle’s case, these included financial turbulences that ultimately led to insolvency and local reputational damage. As the study by Clauss et al. (2022) suggests, temporary changes to the business model, as also observed at Gazelle, potentially harm the original business model and jeopardize the venture’s reputation. Our case shows that a possible avenue to attenuate reputational contamination is to establish a distinct brand as a boundary between the new and original business operations. Gazelle’s experience underscores the complexity and dynamic nature of responding to a crisis through pivoting, highlighting the need to consider potential long-term consequences.

In sum, temporary pivots are, by nature, geared towards addressing immediate challenges and uncertainties triggered by exogenous shocks. They involve temporal, radical changes to the business model, allowing the venture to navigate crises efficiently. However, these changes are made with the underlying goal of preserving the venture’s existing resources and capabilities, thereby ensuring the continued existence of the original business in the long term. In this context, we propose that the temporary pivot serves as a tactical maneuver within the larger framework of another entrepreneurial crisis response—namely, perseverance. While we regard a temporary pivot as a short-term tactical response, it ultimately connects to a more encompassing long-term strategy of perseverance (see Fig. 3).

5.2 From Narrow to Exploratory Perseverance

Current literature mostly understands pivoting as a form of innovation (Clauss et al. 2022; Guckenbiehl and Corral de Zubielqui 2022; Kraus et al. 2020; Ries 2011) and not as a form of perseverance. In addition, previous research contrasts pivots with perseverance as an either/or response to unexpected events; i.e., firms choose to either change or continue their existing business model (Berends et al. 2021). Nevertheless, we identify Gazelle’s temporary pivot as a form of perseverance in response to an exogenous shock, offering new insights into how pivoting and persevering are connected.

Entrepreneurial perseverance has traditionally been associated with sticking to a specific course of action despite setbacks, often driven by a deep commitment to a particular business idea or model (Berends et al. 2021; Lamine et al. 2014). Perseverance as a crisis response is about “preserving the status quo and mitigating the adverse impacts of the crisis” (Wenzel et al. 2020, p. V9). In contrast, pivoting represents a shift in strategy, suggesting a departure from the current path to explore new alternatives. A temporary pivot acknowledges the necessity for change in response to crises while not abandoning the long-term goals of a venture. Temporary pivots, therefore, can be understood as part of a perseverance strategy rather than an innovation strategy. This distinction becomes evident when we consider their primary objectives: adapting to immediate threats, safeguarding the venture’s current state and preserving its long-term viability. Temporary pivots are about “pivoting to sustain,” an idea related to the concept of “exploratory perseverance” advanced by Muehlfeld et al. (2017, p. 534) which in turn aligns with the notion that ventures “keep going back to other options, despite setbacks,” signifying a readiness to adapt and discover new pathways, even while maintaining their existing business model. In this context, temporary pivots manifest exploratory perseverance by allowing entrepreneurs to simultaneously preserve their ongoing ventures while actively exploring emerging crisis-induced opportunities (see Fig. 3). The adaptability demonstrated during a temporary pivot reflects a core element of perseverance: resilience in the face of adversity (Lamine et al. 2014). In this context, entrepreneurs are not abandoning their original businesses but demonstrating the determination to withstand the crisis by embracing change. Here, exploratory perseverance is a long-term strategy that encompasses a steadfast commitment to the venture’s enduring vision and objectives. Unlike temporary pivots initiated in response to crises, exploratory perseverance endures beyond these crises, consistently guiding the venture toward its established goals.

5.3 Limitations and Future Research Opportunities

Our study contributes valuable insights into the dynamics of temporary pivots as a response to crises. However, several limitations warrant consideration. First, the data for this study derives from a single case, which restricts the statistical generalizability of our findings. Nevertheless, when generating new concepts that challenge existing theorizing, single case studies offer possibilities for analytical generalization (see Gioia et al. 2013; Polit and Beck 2010; Yin 2009). Our proposed temporary pivot model could be applied in the case of, for example, short-term market fluctuations, sudden changes in consumer behavior, supply chain disruptions or economic uncertainties due to external factors (e.g., a global event). Second, our study is limited by its specific context. The dynamics of temporary pivots may vary across industries, organizational sizes and cultural contexts. Thus, the applicability of our findings to different contexts should be approached with caution. Third, experiencing multiple crises may be the “new normal.” However, exogenous shocks come in various forms, ranging from economic downturns to natural disasters, each with unique characteristics and impacts on young ventures. While our study delves into the specific case of COVID-19 as an exogenous shock, it is essential to acknowledge that different shocks might yield different responses by young ventures.

Future research opportunities emerge from these limitations. Specifically, investigating boundary conditions within our context and extending the analysis to other contexts could elucidate variations in the dynamics of temporary pivots. In addition, we should explore whether temporary pivots exhibit similar trajectories when responding to other types of exogenous shocks. Given our findings on the nature of temporary pivots, another intriguing avenue for future research is the interplay between pivoting and persevering during crises. Additionally, delving into the responses of various types of firms from varying industries to exogenous shocks could provide a comprehensive understanding of the underlying dynamics.

Furthermore, our study hints at the potential impacts of temporary pivots, but a more in-depth exploration of these ambivalent effects over a longer time frame would enrich our understanding (Manolova et al. 2020; Morgan et al. 2020). Investigating the lasting implications of temporary pivots on firms’ performance and trajectory could offer valuable insights into their strategic value during crises and beyond. Exploring the fluidity of organizations’ or founders’ identities during temporary pivot processes could enhance our understanding of the interplay between identity and temporality within the context of temporary pivots (e.g., Lex et al. 2022). Finally, future research should explore the potential impact of temporary pivots on firms’ long-term strategic orientations, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the transformative consequences.

6 Conclusion

Pivoting has emerged as a vital crisis response strategy. The urgency to act within a limited timeframe and amidst high levels of uncertainty shapes the dynamics of pivoting, necessitating rapid adaptation. Temporary pivots that aim to sustain a business model in the long term should be managed with a clear strategy for reversibility, ensuring that the venture can return to its original business model when the crisis subsides. As firms navigate the intricate landscape of strategic responses to crises, our study contributes by shedding light on the nuanced interplay of pivoting and persevering, providing valuable insights into the dynamic nature of pivoting as a strategic choice.

Notes

In case the position/identity of the interviewee is not specified, we have assigned a number for identification purposes.

References

Agusti, M., J.L. Galan, and F.J. Acedo. 2021. Saving for the bad times: slack resources during an economic downturn. Journal of Business Strategy 43(1):56–64.

Aldrich, H.E., and E. Auster. 1986. Even dwarfs started small: liabilities of age and size and their strategic implications. Research in Organizational Behavior 8:165–198.

Alvesson, M., and D. Kärreman. 2011. The use of empirical material for theory development. In Qualitative research and theory development: mystery as method, 1–22. SAGE.

Arteaga, R., and J. Hyland. 2013. Pivot: How top entrepreneurs adapt and change course to find ultimate success. John Wiley & Sons.

Axelson, M., and E. Bjurström. 2019. The role of timing in the business model evolution of spinoffs: the case of C3 technologies. Research Technology Management 62(4):19–26.

Bahrami, H., and S. Evans. 2011. Super-flexibility for real-time adaptation: perspectives from silicon valley. California Management Review 53(3):21–39.

Berends, H., E. van Burg, and R. Garud. 2021. Pivoting or persevering with venture ideas: recalibrating temporal commitments. Journal of Business Venturing 36(4).

Bingham, C., K. Eisenhardt, and N.R. Furr. 2007. What makes a process a capability? Heuristics, strategy, and effective capture of opportunities. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 1(1/2):27–47.

Blank, S., and B. Dorf. 2012. The startup owner’s manual. Houston: K&S Ranch.

Boddington, M., and S. Kavadias. 2018. Entrepreneurial pivoting as organizational search: Defining pivoting in early stage ventures. Academy of Management Proceedings (Vol. 2018, No. 1, p. 12065). Briarcliff Manor, NY 10510: Academy of Management.

Branzei, O., and R. Fathallah. 2021. The end of resilience? Managing vulnerability through temporal resourcing and resisting. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice 47(3):831-863.

Camuffo, A., A. Cordova, A. Gambardella, and C. Spina. 2020. A scientific approach to entrepreneurial decision making: evidence from a randomized control trial. Management Science 66(2):564–586.

Chandler, G.N., D.R. DeTienne, A. McKelvie, and T.V. Mumford. 2011. Causation and effectuation processes: a validation study. Journal of Business Venturing 26(3):375–390.

Chesbrough, H. 2010. Business model innovation: opportunities and barriers. Long Range Planning 43(2–3):354–363.

Clampit, J.A., M.P. Lorenz, J.E. Gamble, and J. Lee. 2021. Performance stability among small and medium-sized enterprises during COVID-19: A test of the efficacy of dynamic capabilities. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship 1–17.

Clauss, T., M. Breier, S. Kraus, S. Durst, and R.V. Mahto. 2022. Temporary business model innovation—SMEs’ innovation response to the Covid-19 crisis. R and D Management 52(2):294–312.

Colombo, M.G., E. Piva, A. Quas, et al, 2021. Dynamic capabilities and high-tech entrepreneurial ventures’ performance in the aftermath of an environmental jolt. Long Range Planning 54(3).

Conway, T., and T. Hemphill. 2019. Growth hacking as an approach to producing growth amongst UK technology start-ups: an evaluation. Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship 21(2):163–179.

Cowling, M., R. Brown, and A. Rocha. 2020. Did you save some cash for a rainy COVID-19 day? The crisis and SMEs. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship 38(7):593–604.

Doern, R., N. Williams, and T. Vorley. 2019. Special issue on entrepreneurship and crises: business as usual? An introduction and review of the literature. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 31(5–6):400–412.