Abstract

While dynamic capabilities (DCs) are recognized as an important enabler of digital transformation, research lacks knowledge about the underlying challenges and adequate responses of building these capabilities. More specifically, this study aims to shed light into successful digital business model innovation (BMI) by adopting a micro-foundational approach that covers both challenges and successful measures on this path for incumbent industrial firms. Therefore, six case studies building on qualitative empirical research are analyzed that either focus on Internet of Things (IoT)-driven platform BMI or software as a service (SaaS) BMI. The results offer a variety of insights regarding challenges and respective responses. These findings are attributed to DCs and its subdimensions of sensing, seizing and transforming, further revealing the interplay of various factors for specific contexts. Additionally, the study reveals that many challenges and thus required responses are the result of individuals, processes, and structures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The value of business model innovation (BMI) as an adequate strategic mechanism for responding to turbulent environments and changing market conditions (Chesbrough 2010; Mitchell and Coles 2003; Zott and Amit 2010) and for exploiting opportunities arising from digital transformation (Westerman et al. 2014) is widely recognized. Still, BMI in digital transformation remains a complex process and challenging endeavor for many incumbent companies (Favoretto et al. 2021; Volberda et al. 2021). Several companies fail to seize the opportunities of digital transformation due to inadequate responses and strategies (Björkdahl 2020; McAfee and Brynjolfsson 2017).

Recent findings show that the effectiveness of digital transformation is not simply a function of technological challenges and resources (Kane et al. 2019; Vial 2019; Björkdahl 2020). Rather, it concerns building new capabilities and forms of organizing and strategizing (Volberda et al. 2021), as digital transformation is associated with continuous change and an ongoing process of strategic renewal (Vial 2019; Warner and Wäger 2019; Witschel et al. 2019). For this reason, scholars have begun to move towards relevant capabilities when investigating the determinants of digital transformation (Kane et al. 2019). For example, successful firms being originally or long-term driven by digital technologies such as Netflix or Samsung show particularly strong capabilities in this regard. In contrast, incumbent industrial companies seeking to enter digital markets, such as General Electric, are struggling to adapt to digital BMI and, in particular, to a digital platform (Lanzolla et al. 2021; Song et al. 2016). Hence, this paper focuses on the latter type of firms that are threatened by new market entrants, from global software players to start-up companies, attacking their leading market positions (Verhoef et al. 2021).

Several scholars note that dynamic capabilities (DCs) represent such capabilities and promote successful BMI (Achtenhagen et al. 2013; Teece 2018). Particularly in highly turbulent environments (Teece 2012), such as in digital transformation, DCs are continuously required to proactively exploit new business opportunities and respond to environmental threats (Teece 2018; Warner and Wäger 2019; Witschel et al. 2019, 2022). DCs consider environmental dynamics and the associated need for changes in existing resources and capabilities both internally and regarding external partners (Schoemaker et al. 2018; Teece 2007, 2018).

In the context of digital transformation, the increasing transformation of corporate boundaries towards business ecosystems, managing new technologies, and resulting new forms of BMI require DCs to remain competitive (Amit and Han 2017; Teece 2018). While DCs are regarded as a key mechanism of digital transformation (Hanelt et al. 2021; Kraus et al. 2022), less attention is paid to what forms of DCs incumbents need for successful digital BMI (Bresciani et al. 2021; Favoretto et al. 2021; Trischler and Li-Ying 2023; Verhoef et al. 2021).

Therefore, this paper attempts to contribute to the following research gaps: First, building the necessary capabilities for digital BMI in incumbent industrial firms represents a challenging endeavor. This is because it breaks with the logic of offering physical products that has been prevalent among industrial companies, or with forms of value creation such as pay-per-use that are uncommon in the business-to-business or industrial context. In addition, it includes value creation relying on external partners or even entire digital ecosystems that challenge independence (Rachinger et al. 2019; Schmidt et al. 2021). Hence, the subdimensions of DCs, i.e., sensing the right opportunities, seizing them for the respective market environment and transforming extant logics, structures, and processes are affected by digital BMI (Witschel et al. 2019).

Second, DC literature emphasizes the need to go beyond the abstract and generic view of DCs and shift the focus to lower-level mechanisms. Understanding the specific individual’s skills, processes, and organizational structures—the so-called micro-foundations of DCs (Felin et al. 2012; Suddaby et al. 2020)—is important. They reveal relevant factors how firms identify, develop, and implement digital business models (Loon et al. 2020; Witschel et al. 2022). Likewise, this paper contributes to the underlying challenges organizations face in building DCs (Bojesson and Fundin 2021; Helfat et al. 2007; Soluk and Kammerlander 2021). While micro-foundations relevant for building DCs and respective challenges are subject of extant literature (Soluk and Kammerlander 2021; Warner and Wäger 2019; Witschel et al. 2019), a comprehensive understanding of the underlying challenges and barriers remains elusive (Favoretto et al. 2021; Kraus et al. 2022).

Building on the two research gaps described above, this work addresses the following research questions (RQs):

RQ 1

Which are the challenges of building DCs for digital BMI?

RQ 2

How can challenges be attributed to the micro-foundations of DCs and which clusters exist regarding different forms of digital BMI?

In doing so, this research is among the first to provide an in-depth understanding of challenges that companies experience when building DCs for digital BMI. By taking a micro-foundational perspective, it goes beyond exploring challenges to digital BMI, particularly illustrating the most prevalent challenges attributed to the DCs dimensions—sensing, seizing, and transforming—and their underlying micro-foundations. As challenges in building DCs are often generalized or observed in isolation, this study is an important first step towards a comprehensive understanding of how companies can effectively build DCs for digital BMI.

To adequately address the importance of this research context for academia and practice alike, it builds on a multiple-case study among six leading incumbent industrial firms from German-speaking countries. While the understanding of DCs required for digital BMI is limited in general, choosing incumbents on the transition towards digital BMI enables a current research context in which required DCs are likely subject to change (Witschel et al. 2019).

The remainder of this research is structured as follows: Sect. 2 gives the theoretical background of digital BMI, the role of DCs and their interplay, while Sect. 3 describes the method and sample. Section 4 presents the empirical approach, followed by a pattern analysis and interpretation in Sect. 5. Theoretical and managerial contribution as well as limitations and future research are presented and discussed in Sect. 6.

2 Theoretical Background

2.1 Digital Business Model Innovation

Digital transformation has been identified as a driver and an enabler for new forms of BMI (Sorescu 2017; Vial 2019). This can be attributed to a large amount of data generation by companies, products, and customers (Vial 2019). Through their interconnection via the Internet of Things (IoT), those can be leveraged by, e.g., Artificial Intelligence (AI) solutions (Sjödin et al. 2021) and big data analytics capabilities (Ferraris et al. 2019; Mariani and Wamba 2020). Besides technological foundations of digital transformation and enablers of BMI, structural changes, organizational barriers and adequate strategic responses of companies undergoing digital transformation are required (Vial 2019).

One of the major trends of digital BMI can be attributed to service-driven business models (Müller and Buliga 2019). Servitization describes a form of BMI that complements or even replaces physical products as value offers (Linde et al. 2023, Paiola and Gebauer 2020). In this context, generated data can be used to create new value-adding solutions and data-driven services that are tailored to customer demands (Günther et al. 2017; Kaiser et al. 2021). Further, service-based business models monetize data by selling customer-tailored offers like implementation, consulting, or optimization. Additionally, data or insights gained can be monetized by selling it to third parties (Loebbecke and Picot 2015; Müller and Buliga 2019). In this context, software as a service (SaaS) is an approach that is based on Cloud Computing, offering a certain software flexibly via the Cloud. Often, this includes a revenue model where the customer only pays per usage when a certain software is required rather than selling it to customers (Susarla et al. 2009).

Similarly, the IoT plays a crucial role offering significant potential to create new business models. Through company-spanning interconnection of products, humans and customers, large amounts of data can be generated, transmitted, and analyzed to create value for several stakeholders (Langley et al. 2021; Laudien and Daxböck 2016; Leminen et al. 2020; Paiola and Gebauer 2020). In this context, digital platforms are viewed as a facilitator of IoT-based BMI by directly connecting multiple stakeholders that previously relied more on peer-to-peer data exchange. Further, so-called multi-sided platforms enable the integration of various groups of providers and customers, such as connecting both while selling analytics data to third parties (Tian et al. 2021; Veile et al. 2022).

Extant research has analyzed several forms of antecedents for enabling digital BMI, such as the role of digital and organizational capabilities (Müller et al. 2021; Matarazzo et al. 2021; Muhic and Bengtsson 2021; Soluk et al. 2021; Warner and Wäger 2019; Witschel et al. 2019, 2022), cultural issues (Tronvoll et al. 2020) such as entrepreneurial orientation (Ciampi et al. 2021), or the role of strategy (Brenk et al. 2019; Müller et al. 2021; Soto Setzke et al. 2021; Warner and Wäger 2019).

In addition, several technological, organizational, and environmental challenges, barriers and risks for implementing digital BMI have been examined (Brillinger 2018; Favoretto et al. 2021; Kiel et al. 2017; Linde et al. 2021; Muhic and Bengtsson 2021; Rachinger et al. 2019).

Likewise, extant literature investigates the mechanisms of the digital BMI process, i.e., its stages and progressions (Garzoni et al. 2020; Linde et al. 2023; Rong et al. 2018; Tesch et al. 2017), organizational processes (Garzella et al. 2021; Kamalaldin et al. 2020; Latilla et al. 2020; Warner and Wäger 2019; Witschel et al. 2019), relationships (Linde et al. 2021, 2023; Paiola and Gebauer 2020; Rachinger et al. 2019), and supporting tools or frameworks (Kaiser et al. 2021; Linde et al. 2021, 2023).

Nevertheless, the understanding of how companies approach digital BMI is still nascent and fragmented (Caputo et al. 2021; Hausberg et al. 2019). While there are several publications regarding digital skills and organizational capabilities (for an overview, see Bresciani et al. 2021; Konopik et al. 2022; Verhoef et al. 2021), the DCs perspective on digital BMI could still be extended (Bresciani et al. 2021; Vial 2019; Warner and Wäger 2019; Witschel et al. 2019, 2022), as described in more detail in the following two subsections.

2.2 Dynamic Capabilities and Business Model Innovation

Teece et al. (1997) define DCs as a “firm’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competences to address rapidly changing environments. DCs thus reflect an organization’s ability to achieve new and innovative forms of competitive advantage given path dependencies and market positions” (p. 516). DCs are a result of an organizational learning process and are non-imitable, idiosyncratic, and company specific. Strong DCs enable a firm not only to adapt to changes in their business environments but also to shape them actively (Schoemaker et al. 2018). Teece (2007) suggests a threefold processual conceptualization, i.e., the ability of firms to sense and shape new digital business opportunities and threats, seize these digital opportunities, and maintain competitiveness by enhancing, combining, protecting, and reconfiguring a firm’s tangible and intangible assets. In short, DCs can be seen as essential to avoid disruption in changing environments (Schoemaker et al. 2018) on strategic and performance levels (Scheuer and Thaler 2022; Witschel et al. 2022). DCs can be traced back to the behavioral theory of the firm (Cyert and March 1963), suggesting that firms search for superior alternatives for their required performance criteria and trying to implement them in their organizations (Pandza and Thorpe 2009).

DCs have received attention in the field of BMI (e.g., Achtenhagen et al. 2013; De Silva et al. 2021; Heider et al. 2021; Inigo et al. 2017; Leih et al. 2015; Loon et al. 2020; Mezger 2014; Weimann et al. 2020). Likewise, the role of DCs in digital transformation has been investigated by several studies (e.g., Akter et al. 2020; Cannas 2021; Ellström et al. 2022; Ghosh et al. 2022; Magistretti et al. 2021; Sousa-Zomer et al. 2020; Tortora et al. 2021; Vrontis et al. 2020). Combining both research streams, studies acknowledging the role of DCs in digital BMI have started to evolve (Matarazzo et al. 2021; Muhic and Bengtsson 2021; Soluk et al. 2021; Warner and Wäger 2019; Witschel et al. 2019, 2022).

Hanelt et al. (2021) describe DCs as a mechanism to enable BMI as an outcome of digital transformation. Further, they particularly highlight the interrelations between both dimensions alongside contextual conditions resulting from digital transformation. Karimi and Walter (2015) further highlight that DCs and capabilities related to digital platforms are interrelated, as investigated in three out of six cases in this study.

Nevertheless, recent reviews state a limited understanding of how organizations build DCs (Konopik et al. 2022; Kraus et al. 2022; Steininger et al. 2021; Verhoef et al. 2021). In particular, most studies primarily describe DCs for digital BMI as a subdimension and do not offer a comprehensive view of underlying mechanisms, but rather on an aggregate level (Rachinger et al. 2019; Muhic and Bengtsson 2021). Examples include the enabling role of specific DCs such as knowledge exploitation, risk management, and marketing capabilities (Soluk et al. 2021) or big data analytics as a subtype of DCs (Ciampi et al. 2021).

2.3 The Role of Micro-Foundations for Digital Business Model Innovation

Despite emerging findings that strong DCs are essential for digital BMI (Soluk et al. 2021; Witschel et al. 2022), DCs remain criticized in current literature as an overly abstract and highly aggregated analytical construct. It lacks explanatory power and insufficient consideration of the lower levels of DCs, the so-called micro-foundations (Arndt et al. 2022; Bojesson and Fundin 2021; Felin et al. 2012, 2015; Teece 2007). Following Felin et al. (2012) these micro-foundations encompass individuals, processes, interactions and structures, and determine how DCs are developed, manifested and implemented within an organization. The individual level relates to individual skills, cognition, knowledge, or experience and predict individual or collective behavior and actions. Processes and interactions determine how integration, cooperation, and coordination occur, while structures specify the conditions that hinder or facilitate information and knowledge processes, knowledge building, coordination, and individual or collective actions (Bendig et al. 2018; Felin et al. 2012, 2015; Teece 2007). In a nutshell, DCs are described as a “multilevel phenomenon” (Wilden et al. 2016, p. 1027), and thus require an analysis of the role of these subordinate micro-foundations and their interactions to increase the theoretical understanding of the development of DCs (Arndt et al. 2022; Bojesson and Fundin 2021; Foss and Pederson 2016; Magistretti et al. 2021; Santa-Maria et al. 2022; Schilke et al. 2018; Vial 2019). This enables to provide deeper insights for practitioners on how companies can successfully drive BMI (Helfat and Peteraf 2015, Loon et al. 2020; Witschel et al. 2022).

While still nascent, a small number of publications has turned its focus on the micro-foundational perspective on DCs for digital BMI (Soluk et al. 2021; Warner and Wäger 2019; Witschel et al. 2019, 2022). These authors suggest a set of different micro-foundations that are particularly relevant in the digital context, while maintaining a set of established DCs and respective micro-foundations that are consequently developed and adapted along the path towards digital BMI. Witschel et al. (2019) also demonstrate that some micro-foundations relate to a specific DC dimension of sensing, seizing, or transforming. This highlights the necessity of understanding DCs and respective micro-foundations in their interrelations and orchestration (Felin et al. 2012; Feiler and Teece 2014). These capabilities are underpinned by specific skills, activities, and organizational processes and structures (Teece 2007; Warner and Wäger 2019; Witschel et al. 2019), as shown in Table 1.

Below, several challenges for building DCs’ micro-foundations for the respective dimensions of sensing, seizing, and transforming are described.

Sensing refers to the ability to identify new business opportunities and threats in order to proactively drive BMI (Teece 2014; Schoemaker et al. 2018). Digital transformation implies a high degree of environmental dynamism and short technological and innovation cycles, making market and customer scanning and early identification of trends and new technologies challenging (Achtenhagen et al. 2013; Feiler and Teece 2014; Day and Schoemaker 2016; Warner and Wäger 2019; Witschel et al. 2019). To gain a profound understanding of customer latent needs and to obtain and integrate customer feedback at an early stage, it is essential to involve customers directly in the ideation process. This, in turn, implies to adapt established ideation processes that are typically rather of closed nature in incumbent industrial firms (Mezger 2014; Warner and Wäger 2019; Witschel et al. 2019). A further challenge is the ability to understand customer requirements and to translate these into a central value proposition, while incumbent industrial firms are rather product-driven and even struggle with servitization-driven BMI (Müller and Buliga 2019; Witschel et al. 2019). Similarly, collaborations with partners and suppliers allow the successful integration and reconfiguration of external competencies (Feiler and Teece 2014). This is thus considered an important micro-foundation within sensing (Inigo et al. 2017), such as an open innovation approach (Bogers et al. 2019; Westerman et al. 2014). Likewise, while having many testbed-like approaches, both open innovation and BMI struggle in many incumbent industrial firms (Müller et al. 2021; Witschel et al. 2019).

Seizing is subsequently required to exploit new business opportunities based on the appropriate organization of key competencies and the ability to adopt an agile and iterative approach to BMI. As for sensing capabilities, this implies challenges in adopting agile methods in traditional industrial environments (Mezger 2014; Warner and Wäger 2019; Witschel et al. 2019). Customer involvement in development allows to identify problems at an early stage in order to develop a business model that fully meets customer expectations (Amit and Han 2017; Teece et al. 2016; Witschel et al. 2019). In this context, especially smaller industrial firms struggle to present non-finished offers to customers due to established logics and culture (Müller et al. 2021). Finally, when introducing digital business models, ensuring the security and robustness of data and systems is a crucial competitive factor. Similarly, many industrial firms struggle to build and continuously develop the required competencies outside their traditional domains (Kiel et al. 2017; Porter and Heppelmann 2015; Witschel et al. 2019).

Transforming enables firms to adapt, expand, and renew their resource base to create a sustainable organization for business success in the long term (Day and Schoemaker 2016; Inigo et al. 2017; Witschel et al. 2019). Hence, building and developing key competencies is seen as an essential micro-foundation (Feiler and Teece 2014; Mezger 2014; Witschel et al. 2019). In this context, effective and open internal information exchange strengthens employee commitment and motivation (Achtenhagen et al. 2013; Song et al. 2016; Teece 2007; Witschel et al. 2019). However, this is not easily implemented for many incumbent industrial firms due to traditional communication culture (Müller et al. 2021). Also, maintaining existing partners while adding new ones with complementary resources towards ecosystem development are of great importance within transforming (Bogers et al. 2019; Day and Schoemaker 2016; Mezger 2014; Warner and Wäger 2019; Witschel et al. 2019). Incumbents struggle to transform established peer-to-peer relationships into platform-like or ecosystem-driven forms of communication and exchange, especially when adding new partners (Müller et al. 2021; Veile et al. 2022).

Conclusively, while there are several insights on challenges of building micro-foundations of DCs towards digital BMI, a comprehensive overview and analysis on interrelations is still missing (Bojesson and Fundin 2021; Soluk and Kammerlander 2021; Witschel et al. 2019). Hence, this paper develops a multiple case study approach, as described in the next section.

3 Methodology

3.1 Research Design and Case Selection

Since research on DCs’ micro-foundations and respective challenges are in a nascent research stage, this study follows an explorative multiple-case study design (Eisenhardt 1989). It is suitable for nascent research subjects (Edmondson and McManus 2007), as it enables “how” and “why” questions, examination of new insights, and in-depth understanding of specific and complex phenomena in a real-life context (Yin 2009). A multiple case study further provides increased rigor, robustness, reliability, and generalizability of findings compared to single-case studies (Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007; Yin 2009).

The sampling approach (Creswell 2013) was chosen to offer comparability while cases should still differ in certain characteristics to enable theory-building (Yin 2009). Thus, established industrial companies from German-speaking countries were selected that operate in various industries and run digital BMIs. This approach ensured better comparability among cases due to cultural proximity while offering generalizability due to a variety of industry sectors. However, it also limits the results in terms of generalizability to other geographical contexts.

Due to the novelty of the research field, the sampling approach follows a theoretical sampling strategy (Glaser and Strauss 2017), offering insights into the largest traditional industry sectors of Germany, Austria and Switzerland. All companies required to have (a) successfully completed digital BMI, (b) represent an incumbent firm in their industry and (c) represent large firms in contrast to start-ups, having at least 10,000 employees. Further, we deliberately decided to exclude companies from digital or IT-driven sectors such as the software industry. The case selection process was supported by a consulting firm to identify leading companies and contacts for interviews.

Initially, eight relevant case studies were identified. However, after the first round of data analysis, theoretical saturation was achieved (Yin 2009). We then decided to cede data collection at this point since the potential two further case companies would not have brought further insights into already represented industry sectors.

The final case study sample consists of six companies. Those are active in different industries, such as transport, logistics, energy, rail, tire, and industrial technologies (as described in Sect. 3.3) and engage in different forms of digital BMI. Still, homogenous factors include that all companies have successfully undergone digital BMI as per the selection criteria, have a long-standing corporate history that spans several decades. Further, several case companies are considered heavyweights on the German stock market index (DAX).

3.2 Data Collection

Semi-structured interviews with executives and senior managers represent the primary source of data collection, which allow flexibility and openness relating to the exploratory nature of this study (Yin 2009). We thus developed a semi-structured interview protocol (as shown in the Appendix) that was informed by extant literature but allowed themes to emerge during the interviews.

The experts were selected based on the criteria of experience with BMI, particularly their involvement and high degree of decision-making power in digital BMI. For each case study (except for EnerCo), one expert provided details on strategic and organizational aspects, while a second represented technical expertise. Thus, the inclusion of heterogeneous perspectives allowed for a complementary and in-depth discussion of the interview content.

Initial interviews were collected beginning in 2018 and complemented by follow-up data collection until 2019 to update and validate upcoming themes in the analysis process. To complement the interviews, verify statements and gain a deeper understanding of the case studies, various secondary data were collected from internal documents such as internal reports or corporate presentations that were made available by participants. Additionally, external documents, such as media reports, company websites and press releases were consulted to enrich the researchers understanding during the data analysis process. To ensure validity and reliability, the interviews were audio-recorded and verbatim transcribed for data analysis.

3.3 Case Descriptions

MobiCo

MobiCo is active in the mobility sector and offers a variety of mobility solutions to its customers. After several years of development and an orchestrated BMI search process for nearly ten years, the SaaS BMI provided by MobiCo offers applications and data services for mobility solutions. A team of over 30 internal employees works on innovative pricing offers for intermodal transport. Customers can now obtain pricing and purchasing options that are optimized based on the SaaS application.

TrailCo

TrailCo provides transport and freight solutions mainly based on rail solutions, but also intermodal with road transport. Their SaaS BMI aims to offer data-based services in rail freight transport, especially for increasing the predictability of routes, deviations, and other influencing factors for route optimization. In this way, TrailCo aims to close the gap to road-based logistics and service providers that can so far offer higher flexibility.

EnerCo

EnerCo is active in energy provision and operates energy networks, offering solutions up to the end customers. The SaaS BMI offered by EnerCo entails applications and data services based on smart grid technologies for energy solutions in order to offer an integrated service to customers that integrated energy provision, smart home applications, feeding-in power by customers, and electric vehicles.

RailCo

RailCo is a large player in the rail industry, offering solutions in the field of rail rolling stock automation. The case study analyzed in this research is an IoT platform-based predictive data services for rail and infrastructure that integrates different datasets for the operators of trains and infrastructure in order to improve maintenance. Active for two years at the time of the interviews, a separate business unit was launched for running this digital BMI with over 100 employees.

TireCo

TireCo is a leading first-tier supplier to the automotive industry. Running several divisions, the case study on TireCo focuses on tire manufacturing and services. While traditional tires are not analyzed by digital means, TireCo offers predictive data services for utility vehicles’ tires. Based on a set of data across an entire vehicle fleet, the requirement to change tires can be optimized for the operators of utility vehicles, a digital BMI TireCo offers based on a closed IoT platform.

SensCo

SensCo is one for the largest providers for industrial sensors for several different applications. Based on new sensor technologies that are able to generate a large set of interconnected real-time data, the digital BMI is based on an IoT platform. Since traditional customers might not require the capabilities of the new generation of sensor technology yet, SensCo is actively targeting new customers with this IoT platform. For instance, it covers sensor technology for chemical surface analysis that allows data generation and evaluation on the IoT platform.

Table 2 provides further information on the sample and data sources.

3.4 Data Analysis

As a method of analysis, this study follows an abductive logic approach, allowing inductive-deductive reasoning and iterations between theoretical concepts and empirical data (Dubois and Gadde 2002). Thereby, a theory-guided framework (Urquhart 2013) that is organized according to the three generic process dimensions of DCs—sensing, seizing, and transforming (Teece 2007) serves as an analytical framework for data analysis. It is further divided into the underlying micro-foundations relevant to digital BMI (Witschel et al. 2019) as described in Table 1. This enables the allocation of the inductively derived challenges in building DCs for digital BMI to each micro-foundation and thus increases the internal validity of findings (Yin 2009).

Open, axial, and selective coding were used to analyze data (Gioia et al. 2013). First, the interview transcripts and secondary data were carefully reviewed. Hereby, fundamental text passages (e.g., words, paragraphs, or quotes) of specific challenges that were explicitly and implicitly associated with the related micro-foundations of DCs and their related activities and processes for digital BMI were labeled with initial codes. Based on this open coding, first-order categories were identified. Next, axial coding was performed to examine thematic links and patterns among the first-order categories (Strauss and Corbin 1998).

Different sub-challenges such as “prioritization and selection of the right idea” and “find problem to developed solution” were aggregated into the overarching second-order theme “selecting the right idea”. Furthermore, the sub-challenges “lack of knowledge about customer requirements” and “difficulties to find and understand market need” were aggregated into “capturing and understanding market requirements”.

To avoid confirmation bias (Gioia et al. 2013), data analysis up to this point was performed inductively, i.e., without considering the theory-informed micro-foundations of DCs for digital BMI. Finally, selective coding was performed combining the second-order themes, e.g., “selecting the right idea” and “capturing and understanding market requirements” to the aggregate dimension “recognizing market dynamics and trends” that represents the respective micro-foundation of sensing capabilities.

This approach resulted in 98 underlying sub-challenges (first-order concepts) and 39 categories of challenges (second-order themes), referring to 13 micro-foundations of DCs.

4 Empirical Findings

This section presents the observed challenges associated with building DCs for digital BMI illustrated by sample quotes of the interviewees. It is organized into the subdimensions of DCs, sensing, seizing, and transforming (Teece 2007), further divided into micro-foundations relevant to digital BMI (Witschel et al. 2019).

4.1 Sensing

Figure 1 presents the date structure on sensing, which is further described below.

4.1.1 Recognizing Market Dynamics and Trends

Although TrailCo, EnerCo, and RailCo having initial ideas about which markets or market segments they want to be active in, they do not know exactly what the customers require.

When trying to counteract this, companies face difficulties when attempting to obtain information through benchmarking. TireCo and RailCo have to make assumptions including non-specific data due to lacking market transparency. Hence, obtaining information is difficult and time-consuming, while evaluating data then poses further challenges.

New approaches and ideas are further hard to identify. EnerCo, for example, state that project teams are often structured homogeneously in terms of expertise. Hence, problems are mostly viewed from the same angle, potentially overlooking alternative solutions. This can be counteracted by involving customers in projects at a very early stage or by setting up explicitly interdisciplinary and non-conventional project teams from the outset (TrailCo 2).

Even after developing an understanding of market needs, the challenge of selecting the right idea from the pool of generated opportunities arises. TrailCo’s expert explains this as follows: “Well, the main difficulty was certainly not losing focus in the forest of opportunities. The difficulty was rather the selection of these many opportunities that we had. […] the difficulty was to select what was feasible within the framework that we had.” On the one hand, this is due to the large number of ideas generated (TrailCo 1). On the other hand, certain technical innovations offer great potentials, but are not desired or accepted by their customers yet (SensCo). Additionally, future projects must always be selected in line with a company’s strategic orientation and must not conflict with it, which might not be suitable for some forms of digital BMI (EnerCo).

4.1.2 Integrating Customers into the Ideation

Experts from RailCo, EnerCo, and SensCo state that for involving customers, innovation teams are often dominated by technical employees, who are less profound in integrating customers’ problems and feedback. Further, customers are often involved in long-term pilot projects that are typically associated with a higher expenditure of time and money.

Thus, alternative methods, such as workshops, co-creation, and special partnership programs are increasingly applied to involve customers at an early stage. However, according to MobiCo and RailCo, not every customer is suitable for co-creation due to, e.g., lack of market understanding and low degree of innovativeness. So-called “educational sessions” can increase market understanding among customers, but are time-consuming and risky.

Besides generating feedback form customers, its utilization represents a challenge as in MobiCo: “Even though we receive feedback from our customers, the quality is often a problem. Customers don’t always have the necessary know-how to interpret or classify their problems and solutions correctly. And that’s where we have to ask a lot of people: Does this fit? What do you like, what don’t you like? That’s time-consuming, but very important.” But even if relevant feedback is available, it cannot be generalized easily for other customers (SensCo) and thus must be evaluated in resource-intensive processes: “[…] one workshop is not enough. You have to deal with it in greater depth and think about it more” (MobiCo).

4.1.3 Modeling Value Capture Mechanism

TireCo and SensCo state challenges in selecting among a variety of potential revenue models, such as pay-per-use, one-time payments, leasing, and freemium. Legal issues and customers’ acceptance mostly influence this choice while the selection of the right marketing strategy represents a challenge of its own (EnerCo): “And then a lot of brainstorming, methodology, creative methodology got started and we tested […] 30 different marketing approaches, so we really looked with promotional booths at the university, what would be well received, pushed on Facebook […] so we admittedly got a bit lost and spent too long on it.”

Further, additional skills are required for implementation such as if a company that focused on the B2B sector now attempts to enter B2B segments (MobiCo). Trying to train employees and transfer knowledge from other business units remains challenging in this context.

4.1.4 Integrating External Partners into Ideation

In general, the involvement of external partners in idea generation process is not perceived as a significant challenge except for project-specific situations. However, generating actionable results is seen as a challenge (MobiCo) due to “superficial discussion topics” in workshops. With digital collaboration dominating, direct personal exchange is often lacking, or hampered by a lack of communication tools. Another problem is collaboration with competitors. As a result of the competitive situation, an open exchange of information is only possible in complementary topics and often requires a moderator such as a university. This requires, however, complex cooperation agreements (MobiCo): “[…] a platform consists of many partners being connected to a platform, and for each of these partners you need a contract.”

By contrast, the search for suitable partners can be a challenge. For EnerCo. for example, start-ups represent attractive partners for technologies and new approaches. To address the challenge of contacting and integrating start-ups, an external interface was recently created, and a process for screening start-ups was defined.

4.2 Seizing

Figure 2 illustrates the data structure of the seizing dimension of DCs.

4.2.1 Organizing Key Development Competencies

The organization of development teams for digital BMI is described as particularly challenging, requiring interdisciplinary knowledge (TireCo): “People suddenly come onto the tray, we weren’t even aware before that we needed them […].” By linking experts with diverse backgrounds, development teams represent heterogeneous skills (RailCo). Further, the development of new IT capabilities is required, such as visual and UX/UI designers and app developers. Both are rare and are typically obtained externally (EnerCo). Besides, top management often lacks technical expertise and processual understanding, impacting decision-making and implementation paths negatively (TireCo): “[…] the top manager who makes the decision, who sets the budget, has to get deeply involved so that he understands it. […] if that doesn’t happen, then the project manager talks to someone who doesn’t understand him, and he then very quickly falls back on his old stuff and on his old-learned methods, and so on. So, the project is slow. He gives a completely wrong direction.”

Due to the lack of IT knowledge and digital skills, external expertise is required for digital BMI (RailCo): “So, in addition to the whole agile way of working, we have recognized that we can’t do everything ourselves, don’t want to, and don’t have expertise in everything.” Collaboration with external service providers poses challenges that lead to complexity and delays, such as a lack of understanding of specific technologies and processes.

Offshore developments often represent cost-efficient resources but pose further challenges due to different time-zones and the resulting time-shifts, leading to challenges in communication and coordination. Cultural challenges include the lack of a feedback culture abroad and different perception of quality in products and its developers. Hence, a mixture between offshore and onshore development is sought, which, however, entails further challenges in building intercultural teams.

Finally, the organization of key competencies entails specific risks, while Day and Schoemaker (2016) see the capacity for organizational change as a key success factor in adapting to changing environmental conditions. For instance, separation from the core business can make it more difficult to access important competencies (EnerCo): “Sure, you’d wish you had a lawyer sitting right on your lap that you didn’t have to go to appointments every two weeks first. The same goes for a data protection officer. […] you actually have a couple of problems, a couple of bottlenecks that went faster somewhere else.” Non-team members often have skepticism or disapproval fearing a “two-tier workforce”, leading to cultural resistance (TrailCo).

4.2.2 Agile Working Methods

The transition to agile working methods is challenged by rigid routines and lacking experience (MobiCo, TireCo, and SensCo). The need to work in short and fast sprints due to rapid market changes or technological developments requires agile changes in digital BMI to reduce time-to-market. Further, technology firms’ development speed cannot compete with pure digital service providers (SensCo): “[…] than what you know from this engineering-to-order, especially in the automotive environment […]. You have to be fast, and if necessary, you also have to take unusual paths in order to set up a digital or cloud-based business model.” The ability to change direction is illustrated by MobiCo: “[…] so you just start in one direction and realize it’s not the right direction and have to adapt, that’s very difficult.” Selecting and applying the right methods and tools is also challenging (SensCo): “[…] that fits the problem as well as possible. But this is a challenge in a certain way, because the different business units may also have different development processes. And if you’re not careful, you can spend a lot of time simply discussing which process to use.”

In addition, incumbents have difficulties in creating agile working conditions (EnerCo): “[…] very simple tools that would make every day work faster, better, are crossed off the list, are not allowed […]. These are long-established company specifics that we have to fight with and struggle with here.” Also, managers struggle with agile principles, such as delegating responsibility to qualified personnel and decreasing hierarchies. Agile methods also raise resistance among employees, requiring training sessions and promoting a feedback culture for which implementation is a time consuming and complex process (MobiCo):“[…] that’s easy to say, but it’s not so easy to implement. And when something goes wrong, it’s not a question of ‘who’s to blame, i.e., which individual is to blame?’, but where did we do something wrong as a team […]. We first had to learn that we regularly have these retrospectives, that we collect this feedback, that we also create a culture where people give this feedback.”

4.2.3 Integrating Customers into Development

While learning effects arise through close customer involvement, close exchange between companies and pilot groups entails high organizational efforts, such as the selection and composition of the pilot customer group. If chosen without pre-defined criteria or if customer involvement is too close it can hamper the development process (RailCo): “[…]these kinds of projects in this industry take time and […] the savings can’t be implemented overnight, you need a certain amount of breath. So, the pilots you have to say they have quite a long duration, you can say you’re almost over a year, so up to a year these are and that ultimately led us to say we tie up too much capital with a pilot over such a long period of time.” Similarly, TireCo’s expert suggests in this context: “[…] rather start with something small, minimal and continue there, because it comes quite differently than you think anyway. So, when I look at my requirement book today, I would say, ‘Okay, there was a tenth in there of what we ended up doing and then we turned in a different circle anyway.’ So, start quickly, sit closely together, align closely with management, and build a minimum viable product first.”

Further, understanding customer requirements is time-consuming. Particularly in a “… young business environment, where the experience is simply not there, where the customers also don’t know exactly what they want, it’s just as important to find that out […]. With the help of co-creation, intensive discussions with customers, and when you have developed something, you pilot it, try it out, and all these mechanisms that we use to know whether we have the right thing” (RailCo). In addition, customers are not aware of their own requirements, as in the case of MobiCo“[…] we get really great solutions, technically and also the reference, and then the customer says, ‘Yes, but what do I get out of it?’ And if we stand there stupidly and don’t have an answer, then it’s all over straight away, even though we’ve already done it all 20 times.”

4.2.4 Implementing Key IT Activities

An effective implementation of data management represents a challenge in almost all case companies. In particular, data protection, data handling, and data security are described as complex and time-consuming. For instance, data-related laws and regulations across national borders represents a challenge (SensCo): “Often there is a legal component to it, that you have to look at the whole thing from a legal point of view, whether the whole business model works like this, because very quickly it comes out that ‘this is critical, especially with data.’ Data protection is a huge issue, but taxation is also a huge issue, especially when you move data across national borders, you not only have data protection and tax issues, but also data security, how do you design it so that the solution you build cannot be hijacked by a hacker and used for malicious purposes, or that customer data can be read.” Data protection and standardization issues need to be integrated into the development process at an early stage (MobiCo): “If you come up with something great, but it’s not possible from a data protection standpoint, it’s stillborn, so very early in the process you have to get that input in […] in the prototype definition.” Likewise, TireCo’s expert describes: “If I give the data to country xy, am I allowed to store it here at all or do I have to put it on an xy server first? We were not even aware of such questions in advance. No, we realized all that in the middle of it.”

Challenges in software development result, e.g., an unexpectedly high level of complexity with regard to security features (TireCo) “The device has to be registered via a certificate, it has to be secure, the website has to be secure, all the security stories, the security approval, […] that come at you, where you realize, ‘Oh that’s not quite so simple’.” Moreover, iteration cycles between software, hardware, BMI, and the execution of approval tests must be coordinated since “[…] we don’t want to find out at the end, on the 1st of May, we want to launch and then Apple says ‘no, what you’ve come up with, that’s not going to work,’ we’ll do that beforehand and for me that’s still a construction site that I’m not quite able to assess yet” (EnerCo). Equally important is a transparent conceptual design for the software architecture (TrailCo): “Yes, the topic of architecture, it was just that time was very, very tight at the beginning and I think, maybe the topic of architecture should have been given more time, because we have already built up a few technical debts, which we are currently working off. […] clear architectural image, which scales well, invest time there in any case and not break something just because time is pressing […].”

4.3 Transforming

Figure 3 shows the data structure of DCs’ transforming dimension.

4.3.1 Designing and Transforming a Sustainable Organization

All case companies perceive the management of transformation and scaling processes as most difficult. Despite efforts towards digital transformation, lacking commitment on the part of employees persists: “Of course, there are employees who were more in the traditional role, who could not understand what was going on. Or they didn’t have the foresight at that early stage to see that what was being developed was more than just a crank” (TrailCo). Comparably transferring the mindset to management and to obtain support for far-reaching transformation processes represents a challenge (EnerCo): “And one of the most important points, in my opinion, is the internal stakeholder management, to convince the bosses that these digital business models now make sense.” Scaling digital business models requires patience which requires an understanding by management, as it can take longer to gain profitability than established products (SensCo). In rapidly growing organizational units, maintaining a vision and balancing the speed of growth is equally important as not to lose focus (RailCo): “I think that the major organizational challenge and the experience is that it starts from a small very kind of start-up mindset, there are 5 or 10 people looking in it, and then actually keeps increasing because the size becomes so big that you actually need certain standards, certain processes without which the business cannot exist or grow. So, I think this is the big organizational challenge, one is to retain the people that you actually have and second is how do you manage this transformation from being earlier a start-up and then become a driving organization. How do you make this transition?”

In addition, redesigning established structures to integrate digital business models appears to be a major challenge for incumbents with established structures and processes over decades. For instance, large-scale production at SensCo is designed for large quantities and efficient processes. Implementing a small series production of new sensors was not possible, outsourcing production to external providers. Companies that are pursuing a separation from their core business can make access to important skills, e.g., legal, more difficult (EnerCo) and raise cultural resistance (TrailCo). “Fear of losing power and control” also play a key role (TireCo): “Proving that it’s a good idea was the biggest challenge, because many also said: ‘Why do you want to change something? Everything’s great the way it is. It worked, look, the project worked well, it was successful after all …’ but first of all we have to prove that a separate organization makes sense, because of course the department which first has to hand over responsibility would of course resist tooth and nail.”

Further, incumbents struggle to adapt and develop their organization in terms of IT structures and systems. Outdated IT structures and systems that no longer satisfy the new requirements result in performance problems (TrailCo) or a loss of know-how (RailCo). Rapid adaptation to new tools requires noticeable financial investments, and flexibly replacing standard tools and components (RailCo) does not resemble long-term planning processes of incumbents (TireCo): “Yes, so first of all, in such a large company, there is a certain planning process [to continue building up IT resources], […] so you always have to think a year in advance or really with a very, very great deal of effort when something like this is done.”

In this context, incumbents in particular perceive their size as a major weakness in terms of their slow pace of change such as for agile methods (TireCo): “[…] generally in large companies, until the processes are all up and running and all the specifications […], that only contradicts the agile approach and scrum approach […] they really don’t have the time.” Long reaction times are the result of path dependencies in incumbent firms. Long-established employees with a lack of openness, fixed thinking patterns and lacking courage to adopt new approaches can impair BMI and must thus be tackled (EnerCo, MobiCo).

4.3.2 Providing and Developing Key Competencies

Specialized knowledge is required in many contexts, such as skills to sell the digital BMI, since completely new technologies have to be explained to customers (TireCo):“What we found, […] now we have the solution ready, but that doesn’t mean that we’re simply going to be able to sell it quickly, because we realize that today we’ve been selling tires for 140 years, but selling sensors, […] explaining a software solution is completely different […].” Other examples for skills include rights and standards for hardware and software, especially in other countries (RailCo): “[…] so if you had certain data from the train, you also need a domain expert to understand not just how the data is going to be, but what does it mean in the context of the customers’ business, so you need the sales guy, you need the analytics guy, who can understand the data and maybe make the algorithms, but then you also need the domain expert as well […]. So, you need different people, people with different skillsets.”

The “war for talents” includes acquiring and retaining suitable employees who can quickly understand complex processes and familiarize themselves with new subject areas (TireCo): “Well, these 5 people [mathematicians, theoretical physicists and architects, who mostly come from IT and telecommunications] are enormously important […] you have to be very, very careful with them so that they don’t migrate.” “In other words, since there is high demand for specialists on the job market, other companies often try to entice them away.” (RailCo).

Training measures, such as raising the willingness towards lifelong learning, are seen as further challenges (RailCo): “[…] it is a new way of doing business, so everybody has to learn, and the traditional guys or the guys who are in the traditional business have to learn because a lot of the times digital services is not stand-alone, it is part of a, let’s say, larger train opportunity.”. Regarding building sustainable knowledge, the importance of the aspect of time becomes apparent (MobiCo):“It’s [about] skills, about speed, speed, speed, speed.”

However, the results also show that “new digital” skills are not exclusively important, but also maintaining traditional skills (SensCo): “All the software will not somehow run in a vacuum but will still need hardware […], but I think you have to do one without completely neglecting the other in the future. That’s also what we’re trying to do.”

4.3.3 Enhancing Know-How Exchange and Communication

Despite the importance for digital BMI, half of the case companies show resistance to knowledge and information exchange. For instance, conflicts of interest between departments and power struggles hinder the sustainable exchange and development of knowledge (RailCo): “I would think there is a lot of conflict, because everybody is trying to protect their own, let’s say island or business, and try to defend their own interest instead of actually saying: ‘It is good for the company, let us work together.’”

Difficulties also arise in the bundling and coordination of information, as different departments are forced to collaborate towards digital BMI and thus lack motivation to share knowledge (SensCo): “[…] that with these digital business models in particular, the divisional structure as we have it now is no longer really appropriate. Instead, the business units are almost always compelled, forced, motivated to work together.” Communication and coordination challenges also arise as teams are sometimes thrown together from different knowledge domains and backgrounds that have not previously worked together (TireCo): “Bringing that together, coordinating that, is not easy […].”

Closely related, the lack of transparency results from unknown responsibilities and stakeholders (TireCo): “Basically, it is important first of all to create transparency and to tell people or show colleagues what is going on here and to try to be present, I would say, at all corners.” Further, information overload and unavailable information both hamper digital BMI (MobiCo): “[…] they are all in the same building, and they really work according to the principle: It is better to develop than to document. And there is little fungible information available, so you can’t exchange that with them, and we can’t expect that from them, so we can’t ask them to sit down and write some documents for days […] the task is on our side, we have to go there and extract the knowledge in a way that we don’t disturb the day-to-day business.”

4.3.4 Supporting and Interacting with Customers

To retain existing customers and interact with them “it is particularly necessary in the IT area to quickly provide solutions to a customer’s problems so that the customer does not have to record any failures in day-to-day business. However, this […] is usually not a process that takes an hour, like changing a tire, but rather days. And with a larger issue, someone might program on it longer.” (TireCo). Also in this regard, lacking understanding by customers can negatively impact customer satisfaction.

Finally, rapidly changing market requirements and customer needs require long-term proximity to the customer respecting regional differences. While this requires efforts and time, it can determine long-term success or failure of digital BMI.

4.3.5 Scaling the Business Model

Appropriate ecosystem management is required at technological, economic, and legal levels, creating win-win situation that allow partners to generate own revenue (RailCo). Obtaining technological understanding of the ecosystem and defining the relevant contractual and data protection aspects is further required (MobiCo): “[…] people often only think about the technical level, which is the one closest to us as a technology provider. But there is also a commercial level and also a legal level and that you have to clarify all three before it works […] so we already have to know how it can work, because without this knowledge, we are also not able to build the right technology for it.”

In scaling the business model, data protection and data security plays an important role, especially when scaling the business idea, while complying with changing regulations. Competitors might benefit from inadequate data protection (EnerCo), or hackers exploit lacking data security (SensCo). When expanding across national borders, data protection and tax legislation is equally required as trust among partners (SensCo, MobiCo).

Finally, partner management includes search for and selection of partners, e.g., finding reputable and long-term partners who do not violate the value proposition of the digital BMI. Even more challenging are design and implementation of technical partner integration and its financial viability, especially for digital BMI in form of IoT platforms.

5 Pattern Analysis and Interpretation of Findings

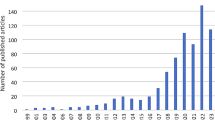

Encompassing 13 micro-foundations the results reveal 39 different challenges: 12 within the sensing dimension, 10 within the seizing dimension, and 17 challenges are related to the transforming dimension. In all case studies, challenges occurred within all three DC dimensions, varying significantly between 9 and 31 among cases (see Table 3).

5.1 Challenges Among Different Types of Digital BMI: SaaS Vs. IoT Platforms

In general, IoT platforms are expected to face more challenges than SaaS business models. This is attributed to the higher complexity of IoT platforms in comparison to SaaS business models. For IoT platforms, a multitude of actors on a platform must be cross-linked, exacerbating the challenges in hardware and software co-development, data management, data mining, privacy, and data security (Lee and Lee 2015, Veile et al. 2022). As illustrated in Table 3, digital BMI driven by IoT platforms overall face significantly more challenges (n = 76), particularly in seizing and transforming, than for SaaS solutions (n = 53). However, if one considers the sensing dimension, a different picture emerges. Figure 4 summarizes patterns relating to the similarities and differences between the two business model types.

In the sensing dimension, more mentions of challenges for SaaS (n = 19) compared to IoT platforms (n = 11) occur. Further, SaaS business models have specific challenges not relevant for IoT platforms, such as formation of technical silos or deadlocked mental patterns that impede the idea-generation phase.

In the dimension of seizing, IoT platforms are confronted with most challenges (26 out of 41). Aspects such as difficulties encountered in the organization of development teams or lack of experience towards agile methods are more pronounced for IoT platforms. In addition, cooperation with external service providers and organizational efforts towards customer integration are challenges that are not found for SaaS.

Regarding the absolute mentions within the dimension of transforming, by far most challenges (39 out of 58) are encountered for IoT platforms. As stated, this can be attributed to the high complexity of IoT solutions and digital platforms with multiple actors (Tian et al. 2021; Veile et al. 2022). This becomes particularly evident for the micro-foundations sustainable provision and development of key competencies, complex bundling and coordination of information, providing fast customer solutions, and complexities within the technical partner integration.

5.2 Origins of Challenges—The Role of Individuals, Processes, and Structures

Since DCs and their micro-foundations are attributed to people, processes, and structures (Barney and Felin 2013; Felin et al. 2012), Table 4 in the Appendix illustrates different patterns that explain how and where challenges are manifested.

Notably, most challenges are found at the individual and process levels, while the structural level is mainly relevant for the dimension of transforming. Moreover, the results show that as the role of customers and partners in building DCs for digital BMI increases (Witschel et al. 2019), an increasing number of challenges occurs at the interface between internal and external levels.

Further, several sub-challenges are interrelated within and between different building blocks, as well as across second-order challenges. For instance, regarding the ability to recognize market dynamics and trends, the underlying (sub‑)challenges are primarily rooted in individuals. Those are also manifested, albeit less pronounced, at the level of processes and structures. On the one hand, lack of individual (or group) knowledge or limited cognition implies difficulties in identifying and understanding customer and market requirements; alternatively, technological developments negatively influence a company’s ability to recognize new business opportunities (Grégoire et al. 2010). On the other hand, lacking transparency and knowledge on competitors and markets constrains the ability of individuals to recognize customer requirements and market developments (Teece 2007). Comparably, structural (e.g., formation of functional silos) or individual challenges (e.g., presence of old thought patterns) impede cognitive abilities of individuals to identify new managerial approaches (Helfat and Peteraf 2015). Overall, these results underline Felin et al. (2012) who emphasize the interdependencies across micro-foundations.

6 Discussion and Conclusion

6.1 Research Contribution

Regarding RQ 1, the study illustrates that building DCs for digital BMI is a complex and multifaceted process characterized by various challenges in all three dimensions of DCs, while transforming being most affected. Further, concerning RQ 2, through adopting the micro-foundational lens, the study allows a more nuanced understanding of the prevailing challenges facing each specific micro-foundation. The results highlight that challenges can be attributed to clusters and different forms of digital BMI, whereby IoT platforms encounter more difficulties in building DCs that SaaS-driven BMI.

In doing so, this research contributes to the emerging research stream that examines DCs from a micro-foundational perspective with respect to digital BMI (Soluk and Kammerlander 2021; Warner and Wäger 2019; Witschel et al. 2019) by investigating the so-far lacking understanding of challenges towards building DCs. While proactively building and managing DCs is a certain asset towards digital BMI, we argue that comprehensive understanding of the underlying challenges opens a valuable perspective for research and adapting management strategies (Helfat and Peteraf 2015; Radic et al. 2022). Therefore, this study provides empirical insights from six case studies that illustrate the challenges of building DCs relevant for digital BMI from a micro-foundational lens. In doing so, the study responds to numerous calls to extend the understanding of micro-foundations in the context of digital transformation in general (Konopik et al. 2022; Steininger et al. 2021; Verhoef et al. 2021; Vial 2019), particularly factors preventing firms from building DCs (Bojesson and Fundin 2021; Favoretto et al. 2021; Helfat et al. 2007; Kraus et al. 2022; Soluk and Kammerlander 2021; Witschel et al. 2019). More specifically, this research extends literature by making the following contributions:

First, the study comprehensively investigates challenges towards building DCs for digital BMI. Therefore, it confirms and extends extant knowledge that digital BMI is challenging for incumbents in several regards. To begin with, digital BMI requires established routines and path-dependencies to consider new forms of value offer, such as turning from product-driven approaches to service-driven or data-driven value offers (Paiola and Gebauer 2020). More precisely, value creation exceedingly requires new partners with complementary competencies or even ecosystem-based approaches while incumbents often prefer internal value creation to dominate (Müller et al. 2021). Finally, value capture mechanisms that are not built upon sales of products might challenge incumbents, requiring to rethink their logic of generating profit towards fulfilling customer requirements (Müller and Buliga 2019; Witschel et al. 2019). Further, the paper provides insights into different types of digital BMI, resembling the complexity of IoT-based platform BMI in challenges of building DCs and its micro-foundations (Tian et al. 2021; Veile et al. 2022) in comparison to SaaS BMI.

A second contribution to literature is that challenges associated with building DCs in the context of digital BMI have different origins and manifest themselves at the individual, process-related, and structural levels. This extends research on micro-foundations of DCs (Barney and Felin 2013; Felin et al. 2012), which has rather focused on facilitating effects than challenges regarding micro-foundations. While individual- and process-related issues represent most challenges, structure-related issues manifest themselves less often. This might be related to the fact that digital BMI is often structurally easier to separate as it includes own value capture mechanisms rather than digital products alone that must be integrated into existing value capture structures (Rachinger et al. 2019). Conclusively, building DCs for digital BMI is rooted on different levels that are intertwined and should thus not be regarded as standalone traits (Barney and Felin 2013; Felin et al. 2012; Magistretti et al. 2021).

Third, this study also considers the nature of underlying challenges. Through examining the different types of challenges, we provide insights on requirements to change corporate culture as well as knowledge and information exchange towards digital BMI (Eriksson 2014; Foss and Saebi 2015), suggesting that organizational transformation requires the ability to change corporate culture. Partially in contrast to extant findings (Favoretto et al. 2021), purely technological or data-related challenges show a less important role for digital BMI when considering building DCs. Further, as shown by Müller et al. (2021) in their study on absorptive capacity and its role to provide ambidexterity and thus enable digital BMI, this study confirms the role of recognizing market dynamics and trends within sensing and the appropriate organization of development competencies within seizing. Moreover, the transforming dimension highlights effective know-how exchange and internal communication, and to scale the business model through partnerships as the most challenging areas. This extends Witschel et al. (2019) regarding the role of transformation as an important enabler of DCs, but an even more important challenge to address in order to develop micro-foundations of digital BMI.

Conclusively, this paper is among the first to provide a comprehensive understanding of building DCs towards digital BMI while taking a micro-foundational perspective. Further, the study illustrates that digital transformation is not just about technology, but rather it is an issue of human factors and their capabilities, processes, and structures that must be regarded in interplay with technological potentials (Björkdahl 2020; Kane et al. 2019; Vial 2019; Volberda et al. 2021).

Figure 5 summarizes the main findings.

6.2 Managerial Implications

The results of this study derive several implications for practitioners and decision-makers. In the following, several prominent aspects are highlighted.

First, relating to sensing capabilities, the results reveal that several challenges are attributed to information or knowledge deficits. Mainly found in the micro-foundation of recognizing market dynamics and trends at an early stage, this challenge is also present concerning the interaction with customers and partners. Countermeasures include securing knowledge, skills, and tools for sensing opportunities. To enhance market, customer, competitor, and technology-related knowledge, internal networks, interdisciplinary teams, cross-industry or region-spanning search represent possible options. Simultaneously, tools and method include design thinking, value stream analysis, co-creation workshops, feedback sessions with customers, or the creation of user stories. Finally, although not exclusive to the sensing dimension, cultural challenges must be solved at the outset. Foremost, management should create an open communication culture, involving employees in decisions and changes at an early stage.

Second, the study’s findings show that building DCs in the seizing dimension leads to knowledge-related challenges at both individual and process levels. Hence, firms must effectively manage, orchestrate, and coordinate knowledge processes including a culture that encourages knowledge sharing and transparency among all actors internally and externally. Integrating external IT expertise or combining market knowledge with IT expertise can assist to develop digital skills. Likewise, investments in IT tools, forming heterogeneous development teams, or cross-departmental knowledge sharing can facilitate the creation of interdisciplinary knowledge. To overcome the challenges related to external actors (e.g., service providers, customers, offshore developers), close information exchange and generating mutual understanding is advised. Regarding data handling and security, additional investments in technologies and competencies is required while running penetration tests that involve partners and customers from early on.

Third, the dimension of transforming shows most challenges and should thus be regarded in particular. The results reveal that focusing on individuals, in addition to process-related issues such as coordination and communication difficulties, promises to be an important lever to overcome challenges. The results clearly show that individuals are pivotal for the success of transforming activities. While specialists with new skillsets are required, they are difficult to recruit and retain, and they must be able to support the development of DCs within the existing team. Traits such as flexibility, independent learning, communication, curiosity and openness must be connected within teams in this context. In particular, incumbent firms with pronounced path dependencies must support cultural change and path-breaking activities. Further, management must balance coordinating and motivating employees to create suitable framework conditions and resources. Hence, top management must create a congruence between strategic orientation and organizational design. On the one hand, digital BMI must be integrated into corporate strategy as a key element. On the other hand, organizational design must resemble strategic projects. Structural options include establishing separate digital units for BMI or a central unit for cross-departmental support and coordination. Especially for incumbents, digital BMI can unfold separately complex established processes and routines of the core business. Finally, communication management must resemble internal and external levels, most notably improvement of communication channels and structures across teams, projects, and companies.

6.3 Limitations and Future Research

Several limitations are to be mentioned based on the multiple case study design that limits generalizability. Moreover, the case studies are limited to two business model types, i.e., SaaS and IoT platforms by incumbent industrial firms from German-speaking countries. This regional focus enhances comparability among our cases due to cultural similarities, but also limits the generalizability of results to other geographical and cultural contexts.

Hence, future studies should include further variables to obtain more far-reaching insights. For instance, considering further business model types, firm sizes, regions, or industries would enhance theory-building. Further, companies with less prominent path dependencies than the incumbent firms analyzed, such as start-ups or hidden champions may uncover different challenges. Potentially, the DCs required for digital BMI are then affected by distinct micro-foundations, as well as underlying challenges associated. Hence, additional qualitative studies should attempt to understand the micro-foundations of digital BMI in different contexts. Moreover, longitudinal studies could investigate how DCs emerge over time and during changing environmental conditions. In addition, how firms manage challenges that arise while building capabilities could be of additional value for future research. Likewise, detailed strategies towards the challenges investigated would allow to enhance the rather superficial results of this study.

Further, we acknowledge that our findings are limited to specific cases of digital BMI. While this allows to focus on the required DCs for BMI, some DCs might not be specific for digital BMI as such. Thus, we recommend for future studies to investigate the differences of required DCs between digital BMI and BMI, for instance by investigating both forms of BMI in the same companies.

Despite these limitations, the presented study serves as a starting point for understanding how and where challenges in building DCs for digital BMI occur. Further, it provides guidelines for practitioners to identify critical issues in building DCs proactively.

References

Achtenhagen, L., L. Melin, and L. Naldi. 2013. Dynamics of business models—Strategizing, critical capabilities and activities for sustained value creation. Long Range Planning 46(6):427–442.

Akter, S., S. Motamarri, U. Hani, R. Shams, M. Fernando, M. M. Babu, and K. N. Shen. 2020. Building dynamic service analytics capabilities for the digital marketplace. Journal of Business Research 118:177-188.

Amit, R., and X. Han. 2017. Value creation through novel resource configurations in a digitally enabled world. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 11:228–242.

Arndt, F., P. Galvin, R. Jansen, G. Lucas, and P. Su. 2022. Dynamic capabilities: New ideas, microfoundations, and criticism. Journal of Management & Organization 28(3):423–428.

Barney, J., and T. Felin. 2013. What are microfoundations? Academy of Management Perspectives 27(2):138–155.

Bendig, D., S. Strese, T. Flatten, M. da Costa, and M. Brettel. 2018. On micro-foundations of dynamic capabilities: A multi-level perspective based on CEO personality and knowledge-based capital. Long Range Planning 51(6):797–814.

Björkdahl, J. 2020. Strategies for digitalization in manufacturing firms. California Management Review 62(4):17–36.

Bogers, M., H. Chesbrough, S. Heaton, and D. Teece. 2019. Strategic management of open innovation: a dynamic capabilities perspective. California Management Review 62(1):77–94.

Bojesson, C., and A. Fundin. 2021. Exploring microfoundations of dynamic capabilities—challenges, barriers, and enablers of organizational change. Journal of Organizational Change Management 34(1):206–222.

Brenk, S., D. Lüttgens, K. Diener, and F. Piller. 2019. Learning from failures in business model innovation: Solving decision-making logic conflicts through intrapreneurial effectuation. Journal of Business Economics 89(8–9):1097–1147.

Bresciani, S., K.H. Huarng, A. Malhotra, and A. Ferraris. 2021. Digital transformation as a springboard for product, process and business model innovation. Journal of Business Research 128:204–210.

Brillinger, A.-S. 2018. Mapping business model risk factors. International Journal of Innovation Management 22(05):1840005.

Cannas, R. 2021. Exploring digital transformation and dynamic capabilities in agrifood SMEs. Journal of Small Business Management. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2020.1844494.

Caputo, A., S. Pizzi, M.M. Pellegrini, and M. Dabić. 2021. Digitalization and business models: Where are we going? A science map of the field. Journal of Business Research 123(3):489–501.

Chesbrough, H. 2010. Business model innovation: Opportunities and barriers. Long Range Planning 43(2–3):354–363.

Ciampi, F., S. Demi, A. Magrini, G. Marzi, and A. Papa. 2021. Exploring the impact of big data analytics capabilities on business model innovation: The mediating role of entrepreneurial orientation. Journal of Business Research 123(6):1–13.

Creswell, J.W. 2013. Qualitative inquiry & research design, 3rd edn., Thousand Oaks: SAGE.