Abstract

Many companies have recently created a new Chief Innovation Officer (CIO) position as a mechanism to help strengthen firm innovation capabilities, but little research is available to help them structure and support it for success. This paper works to illuminate key features and challenges associated with these positions. It does so by integrating findings from roundtable discussions among innovation management executives with scholarly organizational design concepts including competitive strategy, exploration and exploitation, organizational ambidexterity, alignment, change, and power. The paper’s centerpiece is a strategic contingency framework designed to tailor CIO position configurations to different core firm strategies. The framework is built around the well-established and validated Miles and Snow strategic typology. It defines key roles and responsibilities of a CIO position depending on their firm’s strategic orientation (i.e., Defender, Prospector, or Analyzer). The framework also identifies specific organizational resources and support needed for the CIO in each case. The paper concludes by discussing broader insights from our analysis of the CIO position and implications for management practitioners and scholars.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As global economic competition becomes increasingly innovation-driven, many companies have responded by creating a C-level “chief innovation officer” (CIO) position to fuel innovation and drive business growth (Wedell-Wedellsborg 2014). The trend towards CIOs is inspiring and promising in its goals, but some practitioners and consultants report this novel position is a challenging one to implement (Di Fiore 2014; Stevenson and Euchner 2013). The CIO position also represents an important change in the adopting firm’s top executive constellation and by implication its organizational structure (Hambrick and Cannella 2004). Yet, little research has appeared in the scholarly literature to help structure the position and identify factors that can lead to its success. Consequently, companies must rely on intuition or trial-and-error approaches, speaking to a need for systematic work to better inform their efforts.

To help managers more fully realize the potential of CIO positions and inform scholars about this distinctive C-suite position, our paper reports on a multi-stage inquiry to learn more about this emerging phenomenon. We started by inviting a group of senior executives in innovation management (including CIOs) to a roundtable event to explore how practitioners think about the CIO’s role. The discussion questions asked about participants’ views of appropriate goals for CIOs, how the position should be defined, key tasks and challenges, and needed organizational support. We analyzed the discussions to identify key themes in participants’ responses. We extended the analysis by bringing in conceptual perspectives (e.g., regarding competitive strategy, exploration and exploitation, organizational ambidexterity, alignment, change, and power) to develop broader insights about possibilities and challenges associated with the CIO position. Finally, we drew on the analyses to develop a strategic contingency framework that managers can use to connect their firm’s strategic approach with different ways to effectively configure the CIO position and build innovation capabilities.

This paper aims to make three contributions. First, we seek to illuminate the CIO position itself for both practitioners and scholars, through the analyses and framework just described. For practitioners, we hope to play a translational role by bringing conceptual insights and frameworks to bear in service of helping them configure the position and succeed with it. For scholars, we hope to extend existing work on the CIO position and provide some conceptual grounding around key aspects of the position to help guide future research.

Second, the paper adds to the growing literature on the “rise of the C-suite” (Groysberg et al. 2011; Guadalupe et al. 2014) by applying an organization design perspective to examine a prominent new “Chief Officer” position. We examine the CIO’s job within the larger organizational design challenge of aligning a firm’s internal components (structure, processes, culture) with its strategy (Tushman and O’Reilly 2002). Our analysis starts with the recognition that senior executive positions (and their respective offices) constitute an important part of a firm’s organizational structure (Guadalupe et al. 2014; Hambrick and Cannella 2004; Ma et al. 2022). The CIO position specifically represents an important design move, as it realigns the organizational “division of labor” through bringing existing and new innovation-oriented tasks under the CIO’s aegis. The CIO is also intended as a powerful innovation-oriented integration mechanism (Lawrence and Lorsch 1967; Tushman and O’Reilly 2002). We explicate opportunities and tensions that appear to arise from such design changes. We also explain how to align the CIO position with the firm’s strategy and structure to help the firm’s effective functioning in its competitive environment.

Finally, the paper contributes through a novel application of Miles and Snow’s well-established strategic typology (Miles and Snow 1978; see also Hambrick 2003). Specifically, we use the typology’s logic to develop our strategic contingency framework. We demonstrate the typology’s utility in characterizing innovation problems faced by firms with different strategic orientations and how these can be addressed through different configurations of the CIO position. This extension adds to the typology’s utility as an analytic framework for practitioners and identifies areas for future research by scholars to advance theory.

Chief innovation officer roundtable

The roundtable event was held in Chicago in late 2018, when the global economy was still going strong before the Covid-19 pandemic. A total of 36 participants attended, representing a wide range of industries including agriculture, consumer goods, electronics, energy, food production, pharmaceuticals, professional services (consulting, financial, legal), universities, and others. Participants took part in two 45-min roundtable discussion sessions, with 8–10 persons at each roundtable led by a facilitator who took notes during the session.

Each of the two discussion sessions were guided by a set of questions. The first set of questions asked about key responsibilities and tasks of the chief innovation officer’s job:

-

As a chief innovation officer, how would you define innovation for your organization?

-

What should be the main goal or charge of the chief innovation officer’s job?

-

What are the top three to four tasks or activities the chief innovation officer would need to perform in order to accomplish the main goal stated above?

The questions for the second discussion session focused on identifying the organizational support needed for the chief innovation officer, that is the “how to” succeed component:

-

What are the top three to four challenges facing a chief innovation officer’s job?

-

What organizational support would be most needed for the chief innovation officer to succeed?

-

How should the chief innovation officer position be structured regarding reporting relationships, budget and resource access, staff support, performance criteria, etc.?

Findings from roundtable discussions

Participants offered highly engaged responses to our questions, and we provide a summary of the main ideas expressed in the Appendix. We analyzed participants’ responses through an open-ended qualitative approach in which we grouped participants’ own interpretations of questions into first-order themes (Gioia et al. 2013). This initial analysis revealed several distinct themes in answers to each discussion question, which often reflected diverse perspectives and contrasting points of view. We summarize these themes in this section and present a more in-depth analysis in a separate following section.

One important scope-setting observation is that roundtable participants uniformly discussed the CIO position as an independent, stand-alone one. That is, no one referenced a less common situation where an existing senior executive (e.g., head of R&D) “added on” the CIO role. Consequently, in the analysis and discussion that follows we treat the CIO as participants did.

Definitions of innovation from the CIO perspective

A key finding was of basic differences in how the roundtable executives conceptualized innovation from the perspective of the CIO position. The finding arose from the first question regarding how to define innovation as a CIO. We expected that since discussants were primed towards the CIO role, they would emphasize exploratory themes such as breakthrough or disruptive innovations. Several participants did just this, using terms such as disruption, “the next big thing”, “the next big leap”, and strategic innovation. These comments embrace a longer-term, expansive view of value creation and business growth through innovation. However, multiple other participants (unexpectedly) tied desirable innovation tightly to short-term business performance improvement instead. For instance, one participant pushed back against others at his table, emphasizing that in his firm innovations had to show a clear (and relatively quick) path to sales growth. For these latter participants innovation should produce promptly usable knowledge and opportunities whose exploitation can quickly begin.

We also noted some more basic commonalities in these discussions. For one, participants viewed innovation as more than just generating novel ideas and instead viewed it as a means to business success. They also recognized several different types of innovation, for instance product/service as well as process oriented, incremental as opposed to breakthrough, and technological or non-technological in nature (e.g., business models and organizational forms).

Goals for the CIO

When asked about the main goal or charge of the CIO’s job, participants articulated a number of different ideas that seemed to coalesce into three main themes:

-

Taking a leadership role in developing the firm’s innovation agenda, particularly in terms of identifying and prioritizing innovation opportunities. For instance, one participant talked in terms of systematically balancing strategic and tactical opportunities.

-

Uniting the organization behind an innovation agenda, which includes educating and evangelizing about technology trends as well as working across units to align their innovation goals. One participant captured the essence of several comments by saying the key was “getting other people to want to do it”, meaning to work on a broader innovation agenda rather than what was going on in individual functions.

-

Building an innovation culture that energizes people across the firm to pursue innovation. Several participants noted that cultural change requires support from other organizational elements such as process, structure, and people.

Key tasks and challenges

The next set of discussion questions inquired about key tasks and challenges CIOs face. Here, themes reflected a broad range of key tasks:

-

Monitoring innovation/technology trends and best practices in the industry. Different aspects of this theme were mentioned by many participants, and participants also emphasized the need to translate and demonstrate the value of technology trends (e.g., blockchain).

-

Creating internal infrastructure and mechanisms to support innovation. Here, many participants’ ideas tended towards ways to overcome specific obstacles they had encountered—for example, by “breaking the system”, in one participant’s terms—rather than overarching realignment as is typically discussed in organizational design scholarship (e.g., Tushman and O’Reilly 2002).

-

Leading organizational change. Participants also identified tasks and challenges that evoked organizational change as much as innovation as such. These included addressing resistance to change, overcoming bureaucracy and organizational politics, and striking the right balance between quick-and-small wins vs. strategic-and-big ones. Garnering small wins early particularly is an established technique to establish new roles (Reay et al. 2006).

Support and structure

We next asked participants about sources of organizational support and ways to structure the CIO position. The answers clustered into two major areas:

-

Strong relationships with powerful players. Participants noted that CIOs did not have authority to achieve goals on their own, so relationships—formal (i.e., reporting) and informal—are critical. Many indicated it was critical for the CIO to report to the Chief Executive Officer. Wide support from others also was frequently mentioned, with participants specifically citing heads of business units, heads of functions, the board, and investors. Trust and empowerment from the top came up in various ways.

-

Ensuring resource availability. A second theme focused on resource availability for innovation activities. Some participants discussed establishing a central authority and/or separate funding for innovation. Others emphasized that innovation funding tended to be vulnerable to cuts, for instance during downturns or from pressure by other executives wishing to redirect it for parochial purposes. One colorfully said it is critical to “build a wall around innovation”, which to us captured the essence of this theme.

Learnings from roundtable findings

To gain a deeper understanding of the roundtable findings, we brought the basic findings just described together with scholarly ideas from the organizational and innovation literature. We aimed to develop broader insights about the CIO position that were interesting to scholars as well as managers. We present the most interesting findings from this analysis in the form of four underlying tensions facing CIOs as they perform their jobs.

Tension between exploratory vs. exploitative focus for CIOs

The first discussion question—how CIOs should define innovation—revealed differences across participants and their firms. The difference connects to the broader question of how firms balance between exploration and exploitation as they adapt to change (March 1991).Footnote 1 As mentioned, some participants emphasized clearly exploratory innovations such as breakthrough or disruptive ones. This focus is consistent with the CIO position as a counterbalance to the tendency of business units or functional areas to focus on innovations (often incremental ones) that can be exploited quickly (Di Fiore 2014). However, some participants surprised us by defining innovation with reference to relatively short-term performance improvements. For them innovation—even that driven by the CIO—was more exploitative in nature. This suggests the CIO can be less a counterbalancing role than one that bridges between the external environment and immediate needs of business units and functions. The view that is prevalent at a given firm clearly has implications for how the chief innovation officer would help accelerate and enable innovation.

The larger point for CIOs to consider, though, is that their efforts may not be as well insulated from time pressures as they might expect. Even if an exploratory focus is initially encouraged, CIOs should anticipate pressures for a return on innovation investment. This is an important caution if the CIO intends to have a more strategic impact and to act as the counterbalance just described. For scholars, this finding highlights a perhaps unexpectedly fungible dimension of this relatively new position. That is, our findings show the position is driven by the firm’s own definition of innovation problems rather than “automatically” being a largely exploratory one. Accounting for this issue would be important, for example, when researching antecedents or consequences of CIO positions.

Tension between expansive goals for CIOs and need for organizational (re)alignment

The second discussion question—about goals for CIOs—produced responses suggesting the CIO should aim for strategic impact by establishing an innovation agenda and unifying the firm behind it. One the one hand, this sounds like a natural set of goals for C-suite executive. On the other hand, with some reflection the breadth of these goals seems to us expansive and eye-catching. Achieving them would require sustained agreement from multiple executives who will likely have contrasting perspectives and incentives, for instance.

The larger point for the CIO, though, is to recognize that achieving those goals may set up a quite difficult implementation challenge. The danger is that the CIO is successful on the goals side, but subsequent implementation problems reflect back negatively on them. The issue is that much more than agreement is required to implement the agenda. Success will likely depend on instituting a carefully orchestrated corresponding change in organizational design elements such as systems, processes, and structures. The reasoning here lies in the concept of organizational alignment, which emphasizes that organizational components (e.g., strategy, culture, people, systems, processes, structure) are interdependent (Tushman and O’Reilly 2002). Thus, realizing a new innovation agenda depends on organizational elements being realigned in support of the required activities. The CIO would need to assess the likelihood of this happening and set a realistic goal for achievement to avoid the blowback described above.

Tension between evangelism and change leadership

Findings from the third discussion question regarding key tasks point to two central and quite distinct potential roles for the CIO. On the one hand, they need to be a subject matter and communication expert to advocate for enhanced innovation activities within the firm, consistent with an exploratory view of the position. This can include an “evangelistic” component, but this role does not place them deep in the later implementation stages of the change process. On the other hand, participants also suggested the CIO should play an activist and change leader role, where the task is less informing and persuading than implementing. The latter area was where much of the energy in our executives’ discussions occurred.

Here, the larger point for the CIO is to consider the two roles (advocacy vs. change leadership) in light of their position’s strengths. The former role seems to play to the position’s charter and CIO’s own knowledge, and by its nature draws in allies. The latter role puts the CIO in the position of directly influencing others, potentially working against the existing organizational design and against powerful leaders. Later-stage change leadership especially seems to require support from business unit leaders and functional unit heads (Tichy 1983). The challenge is also likely to revolve around the pacing, as change efforts of the magnitude likely in play take considerable time, but leaders face pressure for quick results (Kotter 2012). Evidence consistent with these points is seen in two CIOs’ comments from the roundtable. One reported great frustration by their very limited ability to generate change in the face of high expectations and more powerful business unit leaders who were “stuck” in a traditional view of their markets, products, and technologies. The other CIO reported success in a similar effort, but also described a carefully paced approach. “You have to bring them along”, he said, referring to business unit leaders, “you have to show them how it can happen.” While this took considerable time and effort, the executive set expectations appropriately and reported his efforts were seen as a success.

Tension between expansive goals and CIOs limited power

In the last roundtable segment, participants discussed how CIOs can be supported effectively. Participants often mentioned that the CIO’s position operates in a political environment, and that the CIO had limited formal authority and resources. Political perspectives on organizations have long been prominent in scholarly work (Pfeffer 1992; Tichy 1983). Roundtable participants’ recommendations for CIOs to establish multiple connections to the powerful as well as protections for innovation-oriented resources appear quite compatible with such perspectives.

A politics and power perspective, though, also brings to mind the expansive goals that participants recommended for CIOs that were discussed above. A politics and power perspective might suggest that such goals gain legitimacy from the CIO’s “Chief Officer” title, wherein the symbolism is of an executive “in charge” of innovation. Yet, participants describe the CIO’s reality as lacking in power. This suggests a tension between what might be expected of a CIO, based on those expansive goals, and what even a politically astute CIO might reasonably expect to deliver.

The point for the CIO is to exercise caution in conceiving of their role, and particularly to consider the “in charge” symbolism of their title carefully. It is natural to be pulled towards that symbolism, but establishing distance from the “in charge” symbolism may well be more effective. Instead, as already suggested, CIOs should carefully calibrate expectations and emphasize the need for collective action, in light of their limited tangible power resources. The contrasting experiences of the two CIOs just mentioned above speaks to the value of such an approach.

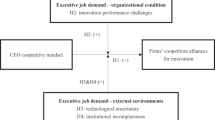

A strategic contingency framework for CIO positions

This section presents a systematic approach to connecting different types of firm strategies to correspondingly different CIO-driven innovation strategies. Our motivation started with roundtable findings that CIO positions and relevant definitions of types of innovation are quite varied, as already explained. We noted this variance resonates with scholarly work wherein innovation plays different roles and manifests in different forms depending on a company’s basic strategic type (Miles and Snow 1978). Organizational designers thus must make important choices as they configure the CIO’s position and innovation agenda. But, there is little available guidance as to how to approach these choices. Our framework aims to fill this void.

We describe our approach to configuring CIO positions as a strategic contingency framework. The core idea is that depending on (i.e., contingent on) the firm’s competitive strategy, effective CIO positions must focus on different types of innovation and be configured differently.Footnote 2 The framework is built around a prominent and well-established typology of strategic types of firms—that of Miles and Snow (1978).Footnote 3 Miles and Snow, among others, argue that firms’ competitive strategies and designs can be classified into a few broad strategic types. Their strategic types are based on the relative emphasis a company places on pursuing external market opportunities versus internal operational efficiency. This approach is similar to that of several other strategic typologies, which see that same distinction as a defining characteristic of competitive strategy (Cheng and Kesner 1997; Jaworski and Kohli 1993; Prahalad and Doz 1987). Miles and Snow describe three main strategic types using this distinction:

-

Defenders are operations-driven companies that emphasize cost-effectiveness and the efficient use of existing internal resources as a basis for competition.

-

Prospectors are market-driven companies that compete on being first in entering new product/market areas and exploiting external resources as they become available.

-

Analyzers take a hybrid approach, attempting to balance the two approaches.

Our strategic contingency framework brings the three Miles and Snow strategic types to the CIO position. The framework’s central idea is that the CIO’s position should be configured consistently (i.e., in alignment) with the firm’s overall strategy. We do this separately for each of Miles and Snow’s three strategic types. Importantly, the typology identifies strengths as well as weaknesses of each strategic type.

Our framework concentrates on tailoring CIO positions to strengthen the firm’s overall strategy by addressing weaknesses in each strategic type in the innovation area specifically. We chose this approach of addressing weaknesses while building on the existing strategy based on the roundtable findings. Specifically, a core finding was that CIO responsibilities are driven by problems—by things the firm is having trouble doing in the innovation space.

The framework’s main message regards how to focus the CIO’s core responsibilities. It goes beyond that, though, by providing advice regarding the structuring and support of CIO positions. That latter advice must account for other design elements such as the organization’s culture and systems. For example, appropriate structure and support will depend on whether action tends to occur through formal channels and processes, or through less formal influence and networks. Here the Miles and Snow typology is again useful, as it describes not just the strategies for each type but also that each type’s typical organizational design features. We tailor our advice accordingly.

Before presenting the framework itself, we point out some scope conditions. First, we focus on recommendations for configuring a new CIO position under the assumption the firm will retain its existing overall strategy and the CIO position should be configured to strengthen its innovation agenda. Second, we conceptualize innovation broadly (i.e., as product or process, as incremental or radical, as technological or non-technological). We do this because the framework is cast at an overall level and companies have different innovation needs and strengths. This approach accords with comments of roundtable participants, who also conceptualized innovation broadly. Third, as reported above, roundtable discussions cast some aspects of CIO positions as generally applicable, for instance recommendations that the CIO report to the CEO directly. The section that follows does not take back those ideas, but adds to them. Finally, we expect the CIO’s role will be primarily in innovation-oriented areas. As a top management team member, they may participate in other issues, for instance those around operations efficiency or marketing effectiveness, but these will not be a major focus of their role.

CIOs in Defender firms

We start by developing recommendations for CIOs in Defender-type firms. Defenders’ strategies tend to focus on particular product-market domains and these firms often work to establish a fortress-like competitive position within them (Miles and Snow 1978). They compete on operational excellence, emphasizing low cost and reliability (Treacy and Wiersema 1993). Innovation in these operations-driven companies is driven by improving the firm’s position in the existing domains more than by entering new product-market spaces. Innovation accordingly tends to focus on process efficiency improvements and cost savings within the existing primary basis of competition, as in the case of GE under Jack Welch, low-cost airlines such as Southwest, and McDonald’s in the fast-food industry.

CIO roles and responsibilities in Defender firms

While Defenders have notable strengths as just described, these firms are also limited in their ability to respond to changes outside their core product and technology domain (Miles and Snow 1978). In the current business environment, multiple technologies in new domains (many digitally driven) have become operationally important, so inability to promptly adopt such technologies raises significant concerns. For instance, such a firm may have trouble realizing the potential of new online marketing technologies—which increasingly are integrated into the operational core of the firm—if that firm had historically focused on more traditional production-oriented technologies. Comments supporting these concerns occurred at several points in the roundtable discussions. Notably, some CIOs characterized their firms as stuck with a narrow focus on existing markets and products. They reported that in these firms innovation outside traditional areas, notably towards digitalization, was neither highly valued nor supported.

Our strategic framework suggests that CIO roles at Defender firms should focus on addressing these weaknesses. Specifically, the CIO’s responsibilities should be tailored to improve the firm’s ability to absorb (Cohen and Levinthal 1990) process-related technologies outside the firm’s existing domain. Monitoring industry advances in process technologies is critical here, including customer-related ones (e.g., customer acquisition, service, and retention). We also expect that the CIO will devote considerable attention to early-stage implementation work with new technologies, such as arranging pilot and demonstration projects. Such efforts provide tangible evidence of the technology’s value and catalyze its adoption. These responsibilities allow a focused CIO role. Overall, the CIO should aim less for radical product or service innovation, given the limited innovation capabilities of Defender-type firms. They should aim more to strengthen the firm’s position in existing product and service domains.

CIO structure and support in Defender firms

What kind of organizational support and structure would help the CIO at Defender firms with the just-described tasks? The most important structural recommendation is the CIO should have relatively high levels of formal authority and resource control in these firms. This is because Defender firms tend to be “command and control” oriented, with clear divisions of responsibility and a culture that respects formal authority (Miles and Snow 1978). The structure of the CIO position should be aligned with this environment, for instance through centralizing authority and separately allocating budget funds in the CIO for all innovation initiatives that are outside the existing domain. Such a structural arrangement, however, might work against business unit heads accustomed to dominating allocation of innovation budgets through their likely higher positional power—a political phenomenon that was mentioned in the roundtable discussions more than once. Because support of business unit leaders is nevertheless critical, the firm should retain the existing budget for business unit-led innovations within established areas.

Regarding support, a CIO in Defender firms will particularly benefit from direct support of the CEO for specific initiatives. The logic is the same as above—a command and control orientation is driven by formal authority and clarity of responsibilities. So, while the CIO will rely on and look to gain wide support from others to drive implementation through the firm, the willingness of those others to support the CIO is likely to depend on clearly evident support of the CEO and other top C-Suite executives (e.g., the COO). Such support can help protect the CIO from the trap of having to push innovation initiatives too hard on their own, and so be seen as encroaching on functional territories which are closely guarded in the more formal cultures often seen in Defender firms. We emphasize this last point as roundtable participants emphasized the difficulty of overcoming resistance towards innovation outside the firms’ primary domain.

CIOs in Prospector firms

Next, we consider CIOs at firms of the Prospector strategic type. These firms’ strategies and capabilities contrast markedly with those of Defenders. Prospectors’ strengths are their capability to explore and pursue radical or “new-to-industry” innovations on a sustained basis (Miles and Snow 1978). For these market-driven companies, product/market innovation is critical to their business success. Innovation often comes in the form of radical or “new-to-industry” products/services with novel or revolutionary features. These are companies such as Apple in 1980s with desk-top computers, FEDEX in the same period with overnight mail delivery, and Tesla more recently in electric self-driving cars.

At the same time, a critical limitation these firms face is potential for fragmentation and loss of cohesion in their innovation efforts. The very decentralization and autonomy that allows extensive exploration works against coordination across units. These firms also can encounter difficulty developing operational efficiencies and maintaining profitability, given their exploration focus. These issues are likely to loom large in today’s environment of cross-cutting technologies, rapid change, and intense performance focus even while introducing new products.

CIO roles and responsibilities in Prospector firms

Our strategic framework accordingly frames the CIO’s job at Prospector firms around establishing coherence and coordinating in this strategic type’s trademark decentralized innovation efforts. The issue is less expanding the range of innovation, as with the Defender. Instead, the CIO should work on blind spots in the innovation-friendly Prospector type, with emphasis on developing a coherent, synergistic innovation agenda. To do so, the CIO should catalyze implementation of effective procedures to help senior executives identify (often longer-term) initiatives that cut across multiple business units (e.g., platform technologies) as well as to evaluate and prioritize innovation opportunities. To achieve coordination and coherence, the CIO should encourage high participation by key executives consistent with these firm’s decentralized structure and influence-based culture.

This role and responsibility profile aligns with roundtable participants’ descriptions of firms wherein top executives self-consciously valued innovation, as in the Prospector strategic type. Interestingly, though, these participants also reported that these executives’ perspectives on innovation nevertheless appeared relatively short-term and narrow. The CIOs thus saw their role as broadening the executives’ views to include promising long-term technological trends (e.g., blockchain). That is, they characterized their role as about education and energizing broader innovation efforts across the firm. We see this as a positive situation, as it does not run afoul of concerns raised by the several tensions we described earlier.

A specific responsibility worth noting for CIOs in Prospector firms involves external partnerships. These have become increasingly important in major innovation initiatives as industry boundaries become porous and the value of rapid access to critical resources increases, for instance as in the recent partnership between Pfizer and BioNTech with the COVID vaccine. For a Prospector, major partnerships can be challenging because they typically require strong corporate leadership which may work against the decentralized ethos of these firms. CIO responsibilities can also include focusing in this area by providing a key integration point to explore, build support for, and initiate external partnerships to acquire critical resources.

We do caution that CIOs probably should not focus on addressing the Prospector’s difficulties in developing operational efficiencies. While one could imagine an innovation agenda wherein process (or efficiency-oriented) innovation plays a central role, this runs the risk of undercutting the Prospectors’ strategic strength in product (or market-oriented) innovation. It might well put the CIO in a difficult, if not untenable position given expectations of their role as helping to implement the firm’s existing innovation-driven competitive strategy.

CIO structure and support in Prospector firms

The structure and support for CIOs in Prospector firms should be consistent with a culture based on informal influence more than formal authority, and on decentralized decision-making. Hence, the CIO’s job should be structured more around a broad charter (from the CEO) to lead integrative activities, such as an overall innovation agenda and corporate initiatives, than to have clear formal authority and dedicated resources as in the Defender case. To ensure complementarity and synergy, the CIO and business unit heads would need to work together and decide jointly on the combined portfolio of innovation projects regarding budget, schedule, and deliverables. Thus, the CIO’s very viability will be dependent on their own efforts to maintain support and credibility across the organization.

CIOs in Analyzer firms

While most companies adopt Defender or Prospector strategic types, Analyzer type firms adopt a hybrid approach that seeks to pursue both market opportunities and operational efficiency. Examples include Amazon in e-commerce, Samsung in consumer electronics, and USA Today in media. Successful Analyzers will be able to reap the benefits of being a first mover in capturing emerging trends in both market opportunities and operational efficiencies. These companies often adopt an ambidextrous organizational structure that integrates exploratory and exploitative innovation efforts at the top management level, but allows for separation between the two (and their associated activities) at other levels within the company (O’Reilly and Tushman 2008).

CIO roles and responsibilities in Analyzer firms

For companies that adopt a hybrid competitive strategy like an Analyzer, the CIO’s job will be substantially different from—but to a certain extent combine–those in market-driven Prospector and operations-driven Defender companies. Instead of the primary task being either enabling adoption of the novel operations-oriented (e.g., process, customer experience) technologies or integrating market-oriented innovation initiatives across business units, the CIO of an Analyzer firm will need to do both. Doing this brings a challenge of balance—that is, how to avoid over-emphasizing one dimension at the expense of the other. The organizational requirements for these two competitive strategies are quite different (Miles and Snow 1978), so implementation of one approach could damage the other core capability. For instance, when 3M implemented the Six-Sigma (process improvement) methodology, its innovation capabilities suffered (Cannato et al. 2013).

Because execution of the CIO’s two tasks (i.e., drive both product/service and process innovation) has differing requirements, the CIO would do well using the idea of ambidexterity in structuring their own position. A CIO could monitor and evangelize process improvement technologies through innovation centers, for instance, but rely on executives in the Analyzer firm’s different business units to determine the degree to which process improvements are central to each unit’s innovation agenda. At the same time, the CIO could work to build coherence between more exploratory units (as with the Prospector) through creation of separate coordination tools, such as an executive committee for evaluating new innovation opportunities like those discussed in the Prospector profile. Beyond this two-pronged approach, the CIO could orchestrate programs to recruit and train employees with synthetic thinking and integrative problem-solving skills. This would help them work effectively in environments with opposing demands such as developing novelty in products/services and efficiency in operational processes.

CIO structure and support in Analyzer firms

Because Analyzer companies compete on both market opportunities and operational efficiency, one would need shared authority and decision-making between the CIO and other senior corporate executives in charge of firm-wide operations (e.g., IT, logistics, manufacturing) and business units with established products/services. This can be accomplished by (1) having the CIO chair a Corporate Innovation Committee that includes these executives as core members, and (2) tasking it to oversee all matters related to advancing firm-wide technology/process operations and new product/service development with the aim of integrating the two to create synergy. To do this, the committee will need a multi-year budget to fund innovation projects at the firm-level which is separate from and supplemental to those provided to the business units.

Discussion

This paper has sought to advance management practice and scholarly understanding by examining the role of the CIO position and how it can be leveraged to fuel innovation and drive business growth. The paper was motivated by the paucity of evidence-based guidance about how to configure Chief Innovation Officer positions. There is a clear need for such guidance, as these “C-Suite” positions have increasingly been adopted and are clearly challenging ones (Stevenson and Euchner 2013). We presented findings about the CIO position from an executive roundtable involving participants from diverse industries, drawing on the broader organizational design literature in our analysis and conclusions. We also developed a strategic contingency framework to help companies align their CIO positions with their competitive strategy. Below we highlight implications of some key findings for practitioners and scholars.

Implications for practitioners

We believe the roundtable findings illuminate the CIO position by revealing key tensions and even pitfalls that the CIOs are likely to face. We came into the roundtable having a sense that the CIO position was about having a strategic impact through enhancing innovation-related activities. While this is of course true, roundtable discussions and our subsequent analysis revealed several tensions associated with the position. Two stand out as key examples:

-

Problem orientation can pressure for rapid results. CIOs are sometimes appointed as solutions to current problems. This appeared to push these CIOs away from exploratory goals (i.e., breakthrough innovation) towards bridging exploration and exploitation (i.e., finding innovations that produce quick business success). These CIOs were pressured to do something their position was not well structured for—to act more as change leaders rather than pathfinders.

-

Title can lead towards expansive goals. There was a notable tension between the “Chief Officer” title, with its powerful symbolism suggestive of a broad, encompassing role on the one hand, and the limited authority and resources of the CIO position on the other hand. A danger is establishing unrealistic expectations that do not sufficiently account for the challenges involved in the position.

The overall advice that emerges is for CIOs to work for a realistic scope and time frame, having a clear idea the pressures and limitations they may face. As part of that, work to secure independent authority and resources. Also, recognize that the position does not exist in an organizational vacuum so changes to align the organization with the CIO’s mission are likely as important as the position itself (Stevenson and Euchner 2013).

The strategic contingency framework provides guidance that connects the firm’s strategy with a recommended configuration for the CIO position. Specifically, the framework builds on the idea that a firm’s innovation needs are likely quite different, depending on its strategic orientation. We focus on a firm’s relative emphasis on pursuing external market opportunities (i.e., Prospector) vs. internal operational efficiency (i.e., Defender) to achieve competitive advantage. The framework’s key message is that the main goal for a CIO is to not only build on the company’s strengths, but also address its weaknesses in the innovation space in ways that are consistent with and advance the company’s adopted competitive strategy. The latter is an intended contribution of our paper, as it extends Miles and Snow’s organizational typology to include analysis of the unique problems faced by firms with different strategic orientations and how these can be addressed via the CIO role. Through these points, the framework provides a focused definition of tasks and support in the face of the broad range of possibilities that the CIO position potentially offers (summarized in Table 1).

Implications for scholars

The CIO position is in significant contrast with existing approaches to innovation management which emphasize the importance of decentralized decisions and authority, for instance well-established concepts such as ambidexterity (Tushman and O’Reilly 1996) or organic structure (Burns and Stalker 1961). The CIO is part of a larger trend in top management teams, the so-called “rise of the C-suite”, which instead tends to increase power at the apex of the organization—that is, to centralize decision-making and authority (Guadalupe et al. 2014). From this perspective, the tensions described earlier seem as interesting conceptually as they are in practice. For one, the tendency to assign expansive goals to the CIO (as our participants did) is consistent with the centralization ethos and symbolic power associated with the title. However, we noted it is also difficult for CIOs to achieve those expansive goals, as CIOs possess limited actual decision-making power and resource authority, and significant organizational re-alignment and redesign may be needed as well. This disconnect raises key questions not only about appropriate roles and goals for CIOs, but also about their likely effectiveness.

The other key tension we mentioned arose from pressure to move away from an exploration focus. This is conceptually interesting because such a focus is a natural one to associate with CIOs, but it is also common for firms to act to solve their current problems (e.g., Cyert and March 1963) as many apparently did in creating the CIO position. We believe these findings suggests fruitful directions for future scholarly research and gain importance because of the concomitant rise of the C-suite and related positions (e.g., Chief Technology Officers).

We acknowledge our inquiry is an exploratory one with attendant limitations. The four-hour length of the roundtable and its format restricted the depth of the comments we could collect. The sample of participating executives was based on their interest, rather than systematic sampling. Consequently, the findings and analysis should be seen as preliminary, though consistent with our aim to provide some practically useful and potentially impactful initial datapoints. To further advance scholarly understanding of the CIO position, we suggest the following research questions for future investigation:

-

What kinds of companies have a higher propensity to have a CIO position? Do these companies have an innovation performance advantage over those that don’t?

-

How do companies define, structure, and support their CIO positions? Is their approach consistent with the strategic contingency framework presented in this paper? Is it better to create a separate CIO position or to add the CIO title (and responsibilities) to an existing senior executive?

-

What are the organizational mechanisms through which a CIO position can help enhance or strengthen company innovation performance? How do these mechanisms differ from those of other C-suite positions in areas such as marketing, finance, operations, or R&D?

-

What are the downside risks of creating a CIO position within the company? How can companies mitigate these risks?

-

What personal attributes, professional backgrounds, and prior work experiences separate the successful CIOs from the others? What are implications for training and recruitment?

We also suggest one additional avenue for future research on CIOs. Our framework applied a well-established analytic approach wherein structure (here the CIO position configuration) follows the firm’s strategy (e.g., Chandler 1962). However, some work in strategic management, notably that taking a process view (Burgelman 1994), posits an opposite causality can also exist. That is, the firm’s existing structure can shape firm strategy, wherein strategy takes a more emergent character and its formulation also depends on which executives are actually involved. The CIO position, with its innovation and change orientation, seems likely to impact strategy emergence over time. Accordingly future work could examine how CIOs shape a firm’s competitive strategy as it emerges, and how strategic choices depend on the varying configurations of CIO positions along the lines discussed here.

We hope the insights presented here help practitioners and inform scholars. For managers, we hope the findings and strategic contingency framework can act as a guide that enables them to avoid some potential tensions and pitfalls of a trial-and-error approach. For scholars, we hope our paper inspires interest in this new C-suite position and provides some promising directions for future research.

Notes

That is, the degree to which organizations work to open new opportunities through new knowledge and capabilities (exploration) as compared to leveraging existing knowledge and capabilities to achieve marketplace success (exploitation).

Contingency approaches have long been used by management scholars to help make academic research more useful in solving real-world problems by treating situational contexts as analytical (contingency) variables (Cheng and McKinley 1983; Donaldson 2006; Galbraith 2012). They are of value to practitioners because context-embedded theories can help them solve problems that they face in their own environment (Cheng 1994; Cheng and McKinley 1983; Murmann 2014).

We chose the Miles and Snow typology for several reasons. It is well-established (cited over 20,000 times) and has been successfully applied in numerous empirical studies. The strategic types are based on a widely recognized distinction between firms that pursue internal operational efficiency and those that pursue external market opportunities, which is applicable to firms operating in diverse industries and business environments. It also meshes effectively with our efforts to develop different configurations of the CIO position specifically.

References

Burgelman RA (1994) Fading memories: a process theory of strategic business exit in dynamic environments. Adm Sci Q 39:24–56

Burns T, Stalker GM (1961) Mechanistic and organic systems. Classics of organizational theory. Routledge, New York, pp 209–214

Canato A, Ravasi D, Phillips N (2013) Coerced practice implementation in cases of low cultural fit: cultural change and practice adaptation during the implementation of Six Sigma at 3M. Acad Manag J 56(6):1724–1753

Chandler AD (1962) Strategy and structure: chapters in the history of the industrial empire. Cambridge Mass

Cheng JLC (1994) On the concept of universal knowledge in organizational science: implications for cross-national research. Manag Sci 40:162–168

Cheng JLC, Kesner IF (1997) Organizational slack and response to environmental shifts: the impact of resource allocation patterns. J Manag 23:1–18

Cheng JLC, McKinley W (1983) Toward an integration of organization research and practice: a contingency study of bureaucratic control and performance in scientific settings. Adm Sci Q 28:85–100

Cohen WM, Levinthal DA (1990) Absorptive capacity: a new perspective on learning and innovation. Adm Sci Q 35:128–152

Cyert RM, March JG (1963) Behavioral theory. In: A behavioral theory of the firm. Englewood Cliffs

Di Fiore A (2014) A chief innovation officer’s actual responsibilities. Harv Bus Rev published on hbr.org Nov 26

Donaldson L (2006) The contingency theory of organizational design: challenges and opportunities. In: Burton RM, Håkonsson DD, Eriksen B, Snow CC (eds) Organization design, vol 6. Information and organization design series. Springer, Boston

Galbraith JR (2012) The future of organization design. J Organ Des 1:1–4

Gioia DA, Corley KG, Hamilton AL (2013) Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: notes on the Gioia methodology. Organ Res Methods 16:15–31

Groysberg B, Kelly LK, MacDonald B (2011) The new path to the C-suite. Harv Bus Rev 89(3):60–68

Guadalupe M, Li H, Wulf J (2014) Who lives in the C-suite? Organizational structure and the division of labor in top management. Manag Sci 60(4):824–844

Hambrick DC (2003) On the staying power of defenders, analyzers, and prospectors. Acad Manag Perspect 17(4):115–118

Hambrick DC, Cannella AA Jr (2004) CEOs who have COOs: contingency analysis of an unexplored structural form. Strateg Manag J 25(10):959–979

Jaworski BJ, Kohli A (1993) Market orientation: antecedents and consequences. J Market 57(3):53–70

Kotter JP (2012) Leading change. Harvard Business Press, Boston

Lawrence PR, Lorsch JW (1967) Organization and environment: managing differentiation and integration. Irwin, Homewood

Ma S, Kor Y, Seidl D (2022) Top management team role structure: a vantage point for advancing upper echolons research. Strateg Manag J 43(8):1–28

March JG (1991) Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organ Sci 2(1):71–87

Miles RC, Snow CC (1978) Organizational strategy, structure, and process. Free Press, New York

Murmann JP (2014). Reflections on choosing the appropriate level of abstraction in social science research. Manag Organ Rev 10(3):381-389

O’Reilly CA III, Tushman ML (2008) Ambidexterity as a dynamic capability: resolving the innovator’s dilemma. Res Organ Behav 28:185–206

Pfeffer J (1992) Managing with power: politics and influence in organizations. Harvard Business Press, Boston

Prahalad CK, Doz YL (1987) The multinational mission: balancing local demands and global vision. Free Press, New York

Reay T, Golden-Biddle K, Germann K (2006) Legitimizing a new role: small wins and microprocesses of change. Acad Manag J 49(5):977–998

Stevenson JE, Euchner J (2013) The role of the chief innovation officer. Res Technol Manag 56(2):13–17

Tichy NM (1983) Managing strategic change: technical, political, and cultural dynamics, vol 3. Wiley, New York

Treacy M, Wiersema F (1993) Customer intimacy and other value disciplines. Harv Bus Rev 71:84–93

Tushman ML, O'Reilly III CA (1996). Ambidextrous organizations: managing evolutionary and revolutionary change. California Manag Rev 38(4):8–29

Tushman ML, O’Reilly CA (2002) Winning through innovation: a practical guide to leading organizational change and renewal. Harvard Business Press, Boston

Wedell-Wedellsborg T (2014) What it really means to be a chief innovation officer. Harv Bus Rev published on hbr.org Dec 5, pp 1–5.

Acknowledgments

This is an equally coauthored paper. We would like to thank Deepak Somaya, John Reid, Rich Niemiec, the Editor-in-Chief and two anonymous reviewers of JOD for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper.

Funding

The authors thank Jeff Brown and Pradeep Khanna for funding the Illinois Corporate Innovation Roundtables at DPI in their respective roles as Dean of Gies College of Business and Associate Vice Chancellor for Corporate Relations at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. The Roundtables provided the forum for collecting the qualitative data reported in the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix

Ideas expressed by participants during roundtable discussions

-

1.

As a chief innovation officer, how would you define innovation for your organization?

Innovation as value creation

-

Innovation is more than creativity; doing something new while building the business

-

Product or process that is new and brings economic or social value

-

New and add value

Innovation as business growth

-

Business growth; not science experiments

-

New ways to generate revenue

-

Growth and sustainability

Innovation as performance improvement

-

Increase bottom-line (i.e., profitability)

-

Risk reduction

-

Maintaining relevance

-

How well you solve problems

Different types of innovation

-

Product-led vs. service-led innovation

-

Breakthrough or disruptive innovation in the right amount

-

Business model innovation

-

-

2.

What should be the main goal or charge of the chief innovation officer’s job?

Lead innovation agenda development

-

Set the agenda for innovation

-

Identify trends and where the firm needs to focus

-

Where is business going, what is the hot new thing, how do we get there first?

-

What technology will allow the business to succeed?

-

Focus company on technology

-

Align to company strategy and goals; influence perspectives based on information and data

-

Determine what to do internally to develop new products or extend current brands

-

Determine which projects to move forward and set priority

-

Balance tactical moves and strategy

-

Allocate resources to support innovation

-

Seed new ventures, from proof of concept to scale

-

Where are we going, what are the measures?

Unite behind innovation

-

Educate leaders on what’s going on (evangelizing).

-

Help people see the disruption; what is the next big leap?

-

Align across units; determine what roles are really needed

-

Integrate toward common goals across functions

-

Create cross-functional teams, break down silos, keep things moving.

-

Liaise with IT and support digital innovation officer

Build an innovation culture

-

Unleash creativity of the firm

-

Develop a culture of innovation

-

Help company become more nimble, a major challenge for large established firms

-

Create grass roots innovation … from the bottom up… have it permeate the organization

-

-

3.

What are the top three to four tasks or activities the chief innovation officer would need to perform in order to accomplish the main goal stated above?

Knowledge building and external monitoring

-

Gather competitive intelligence and understand trends

-

Partner with universities and start-ups

-

Identify and harness outside innovation opportunities

Creating innovation infrastructure and mechanisms

-

Work with all internal leaders and stakeholders

-

Collaborate across business units (i.e., assist in)

-

Meet with areas within the company to understand what innovation means to them

-

Develop and implement a consistent definition of innovation

-

Get employees to set goals and priorities for innovation within their specific areas as part of their performance management process

-

Get others to want to innovate or adopt new technology; do this through evangelizing with line managers, senior executives, and the board

-

Enable others to be creative

-

Provide innovation training for people throughout the entire company; tap into the collective curiosities

-

Develop a technology road map rather than a strategy; road map indicates what needs to be done and when so it puts a harder edge on discussion about commitment and priority

-

Develop a “playbook” of best practices for a technology and share it across units

Building credibility/early wins

-

Get some quick wins to energize focus and make innovation real

-

Look for low hanging fruits to gain credibility

-

Build business cases through trial-and-error; piloting projects

-

Find a new technology that can easily be implemented to show potential

Other comments

-

Be able to identify and understand pain points.

-

Know how to prioritize (what ideas to move forward); understand opportunity cost.

-

Be able to synthesize ideas from diverse sources and perspectives.

-

Embrace failure; be comfortable with failing fast, and know when to pull the plug.

-

-

4.

What are the top three to four challenges facing a chief innovation officer’s job?

Resistance to change

-

Changing the mindset and culture to allow for rapid innovation

-

Bringing in new technology

-

History: “We have tried that already and it did not work”

-

Breaking the system (hardest part)

-

Getting the company to think like a start-up; nimbleness

Bureaucracy and politics

-

Dealing with internal legal department

-

Line managers: They don’t think they have a problem with innovation; they say they are doing it, and don’t see the CIO as a solution; they focus on incremental innovation

-

Tension between speed vs. red tape

-

Getting buy-in from leadership

-

Determining what internal processes are required based on the innovation stage you’re in

-

Balancing competing priorities

Acquiring/protecting innovation resources

-

Protecting innovation budget when business performance is down

-

Finding time to evangelize

-

Insufficient funding

-

Finding people with the right skills

Measuring innovation and tolerating failures

-

Intolerance for experimentation and failure

-

Generating ideas but failing to implement

-

Measuring success

Other comments

-

Inconsistent definition of innovation across the firm

-

Not knowing what you don't know

-

Managing partnerships

-

Staying connected to the business and customers while innovating

-

-

5.

What organizational support would be most needed for the chief innovation officer to succeed?

Empowerment/trust from the top

-

CEO buy-in and signaling of importance

-

Have incentives from CEO for innovation

-

C-Suite buy-in and backing to overcome roadblocks

-

Ensure that there is enough credibility in the position so it becomes part of company strategy

-

CEO’s willingness to change corporate culture to support innovation

Support from other Stakeholders

-

Buy-in from investor partners

-

Support from the legal department

-

Alignment and collaboration with business units

-

-

6.

How should the chief innovation officer position be structured regarding reporting relationships, budget and resource access, staff support, performance criteria, etc.?

Reporting

-

Have marketing, R&D, and strategy be all part of the responsibilities of the chief innovation officer

-

Direct report to CEO

-

Set-up an innovation lab or entity outside of the existing organization

-

Establish a wall to protect innovation

Budget

-

Centralize funding for innovation; eliminate innovation budgets within business units.

-

Have both a project budget and a strategic initiative budget

Performance criteria

-

What have we done to deliver a new sustainable revenue stream? Where are we hedging? Is what we’re doing making the firm famous?

-

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng, J.L.C., Love, E. Designing chief innovation officer positions: a strategic contingency framework. J Org Design 11, 115–128 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41469-022-00126-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41469-022-00126-6