Abstract

How are financial incentives and innovative activity linked? We analyze how firms’ use of financial incentives is associated with their employees’ innovative activity. The presence and transparency of financial incentives matter for the link between incentives and innovative activity, just like the activity profile of those receiving incentives. In a study of managers and workers in small German manufacturers, we find that financial incentives and explorative and exploitative innovative activity do interact. Financial incentives for managers (workers) are positively (negatively) associated with exploitative innovative activity, and negatively with exploratory innovative activity for both groups of employees. Furthermore, a transparent compensation system counteracts the negative association of financial incentives for workers on innovation activity, especially exploration. Our study qualifies the claim that extrinsic motivation crowds out innovative activity and specifies under which conditions the use of financial incentives in a firm is associated with different degrees of organizational exploitative and explorative innovative activity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Understanding what drives innovative activity is a core question in the management and organizational design literatures. Specifically, how do firms manage the tradeoff between exploiting and refining existing knowledge and exploring new avenues (Levinthal and March 1993; Rothaermel and Deeds 2004; Andriopoulos and Lewis 2009; Raisch et al. 2009Eisenhardt et al. 2010)? Prior work recognizes that environmental (Beckman et al. 2004; Jansen et al. 2005), organizational (Jansen et al. 2006; Sidhu et al. 2004), and top-management factors (Smith and Tushman 2005; Tushman and O’Reilly 1996) will affect the success of pursuing these different goals concurrently. In practice, firms such as Google and 3M run programs that give their employees 20% of their time to pursue innovative projects. However, little is known about how to channel individuals’ activities towards specific innovative activities conducive to the organization (O’Reilly and Tushman 2013; Raisch and Birkinshaw 2008).

A fundamental question of organization design is: how should a firm’s internal workings be organized so that individual activities translate into firm performance? We focus on variable financial incentivesFootnote 1 as a design feature used to motivate individuals to exert effort to the firm’s benefit. We study small firms, because we expect individuals’ activities to affect firm performance more directly than in large conglomerates and because structural measures to promote innovation may be unavailable to small firms, leaving financial incentives as a key instrument to encourage innovation. Our main research question is, therefore: How are financial incentives associated with innovative activity in small firms?

This broad question opens up a number of further questions: Will different employee groups respond differently to the presence of financial incentives? Are exploitative and exploratory innovative activity associated with variable financial incentives in the same way? Furthermore, does the transparency of the incentive system matter for the association between innovative activity and variable financial incentives? We explore all three in small manufacturing firms, a useful setting to assess the association of individual incentives and firm innovative activity. To our knowledge, the role of financial incentives in employee activities along different dimensions of innovation and different groups of employees is new to the literature, which often assumes homogeneous responses across the workforce and a single innovative activity. Likewise, the transparency of incentive systems has not received prior attention in the context of innovation.

We study the heterogeneous role of incentives in innovative activity beyond prior work on individual-level innovation (Baumann and Stieglitz 2014; Ederer and Manso 2013; Lee and Meyer-Doyle 2017). While most research finds that incentives motivate individual performance and productivity (Lazear 2000a; Prendergast 1999), little is known on how financial incentives correlate with corporate innovation (Charness and Grieco 2019), let alone different kinds of innovative activity, especially as high levels of extrinsic motivation can crowd out intrinsic motivation and thereby hinder innovation (Amabile 1997; Deci and Ryan 1985). We fill this gap by asking if the use of financial incentives in a firm is associated with different degrees of organizational exploitative and explorative innovative activity.

Innovative activity is not simply a function of effort, because it is inherently uncertain, and different innovative activities differ in their degree of risk. Exploration—the addition and integration of new knowledge into the firm’s knowledge base—is considered more risky than exploitation—the recombination of existing knowledge (Katila and Ahuja 2002; Lin et al. 2013). We offer predictions on the differential roles of financial incentives for innovative activity based on the employee’s position and compensation. We test these predictions on small firms in the German manufacturing sector. Small firms face specific challenges in designing their incentive system to foster innovation. On the one hand, small firms face the same competitive and environmental pressures to jointly pursue exploitative and explorative innovative activity as large and established firms (Hitt et al. 2011; Ireland et al. 2003; Ketchen et al. 2007). On the other hand, they often lack the (slack) resources and the kind of hierarchical administrative systems to create an ambidextrous organization that simultaneously pursues exploration and exploitation, for example through structurally separate business units (Ireland et al. 2003; Lubatkin et al. 2006). Smaller firms simply may not be able to afford employees or teams to focus on just one activity. Hence, small firms have to resort to coordination mechanisms, such as incentive systems and their transparency (Aschenbrücker and Kretschmer 2018; Puranam et al. 2014) to direct their employees’ search activities.Footnote 2

We use semi-structured survey questions to gather information on the firms’ strategies, organization designs, and compensation systems (Bloom and Van Reenen 2007). We study financial incentives for production managers, who are less involved in operational tasks and in charge of developing the firm, and production workers, who can work both on operational tasks and on innovative tasks. We find that while financial incentives for managers are indeed positively associated with exploitative innovative activity, financial incentives for workers are negatively associated with exploitative innovative activity. Furthermore, the interaction of financial incentives for workers and a transparent compensation system is positively related with both types of innovative activity. The implications of our results are far-reaching: We show if and when firms may use financial incentives alongside different types of innovative activity. As such, we highlight a possible path for firms to balance exploration and exploitation (Hitt et al. 2001; Snow 2007). Our study is one of the first on the design of tasks and compensation in small firms, and on how organization design can affect both the intensity of firms’ innovative activity as well as its direction, i.e., towards exploration or exploitation.

Theory and hypotheses development

Exploitative and exploratory innovative activity

We think of innovative activity, broadly defined, as covering all behavior aimed at improving firm performance either through improving current processes and products or by expanding the firm’s range of activities. It is a search process for better solutions that can be close or distant to the current solution, i.e., recombine existing knowledge or generate and integrate new knowledge (Huber 1991; Winter 1984; Katila and Ahuja 2002; Lin et al. 2013).Footnote 3

We build on March’s (1991) notion of exploitation and exploration as different types of innovative activity (Andriopoulos and Lewis 2009). Exploitation requires efficiency and convergent thinking to make use of existing knowledge, skills, processes and structures in well-understood ways, thus continuously improving the product-market efficiency (Wadhwa and Kotha 2006; He and Wong 2004; Lewin et al. 1999). Exploration requires distant search and experimentation, leveraging varied and dispersed knowledge in new ways to enter new product-market domains catering for emerging customers or markets (Benner and Tushman 2003; Taylor and Greve 2006). Hence, while exploration and exploitation are different innovative activities, they compete for scarce firm resources, which simultaneously creates tensions and synergies (Gupta et al. 2006; Tushman and O’Reilly 1996).

Firms try to steer and manage innovative activity (Ahuja et al. 2008; Zimmermann et al. 2015) at inter-organizational (Lavie and Rosenkopf 2006; Lin et al. 2007; Rothaermel and Deeds 2004), organizational (Jansen et al. 2006; Nohria and Gulati 1996; Sidhu et al. 2004; Voss et al. 2008), team (Auh and Menguc 2005; Haas 2010; McGrath 2001), and individual levels (Mom et al. 2009, 2007; Raisch et al. 2009). For example, many firms have established continuous improvement processes, Kaizen policies, or employee suggestion systems (Fairbank and Williams 2001; Recht and Wilderom 1998). The underlying logic for all of these is that individual search efforts can be a valuable source of firm-level innovation (Siggelkow and Levinthal 2003; Siggelkow and Rivkin 2005; Baumann and Stieglitz 2014). Corporate entrepreneurship or innovation tournaments also capitalize on the notion of decentralized search efforts (Baumann and Stieglitz 2014). Individuals’ innovative activities are not contractible, i.e., the extent or direction of innovative activity cannot be centrally mandated.

Employees’ activities and their inherent risk as drivers of innovation

In search for better solutions, employees (workers and managers) choose a combination of innovative activities according to their cost of effort and the expectations the firm has in them (i.e., their job description). Some of these activities may use existing knowledge and be aimed at mastering known and well-defined tasks. Advancements along those lines are then based on learning through repetition, e.g., through minimizing faults, idle or lead times.

Other activities may involve the (re-)combination of different types of existing knowledge. Understanding the tasks and workflows of an adjacent line worker, an employee can for example improve the handover to this worker. Likewise, managers can improve inter-departmental collaboration by connecting different elements of their existing knowledge base.

Innovative activities may also involve the integration of new knowledge. By exploring new alternatives through trial and error, employees can extend their knowledge base and as such the solution space for novel combinations of knowledge. For example, a machine operator may redefine her core activity by performing several steps in parallel rather than sequentially, or a manager can initiate the development and investment into revolutionary new products. Glenn Bradley for example, then-president of contact lens producer Ciba Vision placed a bet on six such products devoting all company resources to their success, which helped the firm catch up with competitors by entering new businesses in the early 1990s (O’Reilly and Tushman 2011).

We can think of the combination of these three kinds of activities in the form of an activity profile bearing a degree of (aggregate) risk. Comparing the activities, the exploration and integration of new knowledge elements is riskier than the combination of existing knowledge which in turn is riskier than simple investments in task proficiency. The latter come with an almost deterministic rate of progress, exploitative innovative activities lead to “positive, proximate, and predictable” returns and exploratory innovative activities are “uncertain, distant, and often negative” (March 1991, p. 85). Moreover, the outcomes of these activities become more ambiguous with risk. Superiors may not be able to evaluate the outcome of exploratory innovative activities accurately, while improvements in task proficiency are easy to assess, and exploitative innovative activities lie in between the two. Hence, increased risk of an activity comes with increased assessment bias of its outcomes.

However, this risk ordering does not necessarily lead to an exclusive focus on one kind of activity. Each of the activities will experience decreasing marginal returns as the improvement along any dimension of search is only possible until its intrinsic performance limit is reached (Dosi 1988). Activities aimed at task proficiency are limited by perfect mastery, exploitative innovative activity is limited by the size of the existing knowledge base (Fleming and Sorenson 2001; March 2006), and exploratory innovative activity by its variety increasing the probability of failure (Heiner 1986, p. 84; Levinthal and March 1993).

The influence of financial incentives on employees’ search activities

Financial incentives play an important role in motivating individuals (Kreps 1997), in coordinating their activities (Kretschmer and Puranam, 2008; Puranam et al. 2014), and in affecting their (search) efforts (Lazear 2000a; Bandiera et al. 2007) and activities (Lee and Meyer-Doyle 2017; March 1991; Khashabi et al. 2021). However, the link between financial incentives and innovative activity has not been studied extensively (O’Reilly and Tushman 2013; Raisch and Birkinshaw 2008) with a few notable exceptions. Manso (2011) studies optimal incentive schemes to foster innovation and emphasizes the use of long-term financial incentives to promote effort that benefits the firm in the long term, such as innovation. This intuition is then tested and confirmed in Ederer and Manso (2013) in a lab experiment. Furthermore, Failla and Amore (2020) study the role of incentives on innovative activity, but they consider the dispersion (rather than provision) of incentives in boards and focus on the extent rather than the direction of innovative activity. Finally, Laureiro-Martinez et al. (2015) show that incentive pay influences both the extent and the direction of efforts.

If no variable incentives are in place, employees exert a minimum level of effort and allocate this effort across the different kinds of activities to maximize actual output. With incentives in place, employees will choose the overall level of effort as well as the allocation of search activities to maximize perceived performance. That is, employees consider the risk inherent in these activities as well as the risk from how their performance is assessed if incentives are in place. Specifically, employees may consider the risk of not receiving the (full) incentive as a threat of punishment (Hossain and List 2012; Kohn 1999) and their willingness to take risks is reduced as performance is usually evaluated on a short-term basis (Lee and Meyer-Doyle 2017). Perceived performance is also noisy by nature, as noted above. While environmental turbulence may drive some of this noise,Footnote 4 another part of it is due to assessment bias by supervisors. Even if supervisors aim to evaluate employees’ performance in an unbiased way and manage this on average, supervision is incomplete (Kieser and Ebers 2014) so that supervisors will sometimes miss or misinterpret at least some information on employee output.

Thus, if financial incentives are in place, the overall risk of the same set of activities to the employee is higher than without incentives given the assessment uncertainty. Employees will then adjust their activities and resort to less risky and easier to assess activities to offset this effect of an incentive scheme compared to the case without financial incentives.

Differences between managers and non-managerial employees

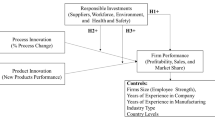

Managers and workers, or non-managerial employees, assume different roles in an organization resulting in different tasks, responsibilities, and activities. In particular, managers typically do not perform operational tasks themselves anymore, or only to a very limited extent. Instead, they delegate and administer such tasks and engage in strategic and business planning as they move up in the organizational hierarchy. Managers thus typically have larger and broader knowledge bases than their non-managerial colleagues, which puts them in a relatively better position to pursue exploitative and exploratory innovative activities. Non-managers are more likely to engage in increasing their task proficiency as they correspond better to their clearly defined tasks as well as their relatively more limited knowledge resources. Thus, compared to workers, the activity sets of managers are likely to contain more risky activities on average (Hackman and Oldham 1976; Kohn 1999). We visualize these relationships in Fig. 1.

Accordingly, we expect a differential influence of financial incentives on employees’ search activities for managers and workers due to their different activity profiles and the associated risk. As exploratory innovative activities are the riskiest type of activity for both managers and workers, we expect their share of any employee’s overall activities to be lower if incentives are in place.Footnote 5

Considering exploitative innovative activities, however, we expect managers and workers to react differently. Given that managers are expected to engage in more risky activities by virtue of their role description and their larger and broader knowledge bases on average, they are restricted in their ability to reduce the risk of their activity sets further. Hence, while both groups of employees will aim to offset the additional risk exposure of incentives and the corresponding performance evaluation by shifting their activities towards less risky alternatives, which of these alternatives are available makes a difference. Workers can lower the risk of their search activities further than managers, i.e., they can spend more time on task proficiency enhancements. That is, under an incentive scheme, we expect workers to engage less in exploratory innovative and exploitative innovative activities. Conversely, managers will shift activity profile from exploratory innovative activity to exploitative innovative activity. Building on Siggelkow and Levinthal’s (2003) concept of decentralized search, we further argue that individual employee activities accumulate at firm level in a sense that the aggregated innovative activity of employees affects the overall firm’s innovation. This leads to the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1a (H1a): Firms using financial incentives for non-managerial employees display less exploratory innovative activity than firms not using them.

Hypothesis 1b (H1b): Firms using financial incentives for managers display less exploratory innovative activity than firms not using them.

Hypothesis 2a (H2a): Firms using financial incentives for non-managerial employees display less exploitative innovative activity than firms not using them.

Hypothesis 2b (H2b): Firms using financial incentives for managers display less exploitative innovative activity than firms not using them.

The moderating role of the compensation system

Our reasoning for H1 and H2 builds on the employees’ aggregated reactions to increased risk exposure under a financial incentive scheme. This risk is at least partly due to supervisors’ assessment bias, and the influence of this assessment bias on perceived performance and consequently the employees’ activities depends on the transparency of the firm’s compensation system. If the compensation system is not transparent and difficult to understand, the risk for employees when deviating from the operational status quo is high. If employees change the way of doing things, it is unclear how superiors will assess this deviation. Conversely, if goals and rules of performance evaluation are explicit and measurable upfront, employees know what to optimize, which in turn reduces the risk from assessment bias. Hence, a defined set of rules setting performance goals and measurement criteria reduces the impact of supervisor bias. Consequently, the employee will allocate relatively more effort towards riskier search activities under a transparent compensation system. Hence, the transparency of the compensation system affects employees’ choice of innovative activities by reducing the risk compared to non-transparent financial incentives (while it is still higher than for fixed pay only).

Again, we argue that managers and non-managerial employees are affected differently. In line with the respective task profiles, measuring managers’ task performance typically occurs with respect to departmental or firm performance. Workers, in contrast, are typically evaluated against measures within their own control. For a production manager this could mean that she is expected to increase department output by 5% per year or to reduce overall scrap rate by 2%. For individual line workers these goals are broken down into more immediate targets. A line worker may be expected to assemble 120 widgets per hour or to make sure that 95% of her monthly widget production meets the desired quality. A transparent compensation system will have more impact for activities that are easy to measure and assess. Hence, we expect the link between meeting transparent targets and the effort invested to meet them to be more immediate for workers with a higher share of easy-to-measure activities. Hence, we only hypothesize an interaction between a transparent compensation system and financial incentives for non-managerial employees.

Hypothesis 3a (H3a): The negative association between financial incentives for non-managerial employees and exploitative innovative activity is less pronounced if the compensation system is transparent than if it is not.

Hypothesis 3b (H3b): The negative association between financial incentives for non-managerial employees and exploratory innovative activity is less pronounced if the compensation system is transparent than if it is not.

Figure 2a, b summarizes our hypotheses regarding the influence of financial incentives on exploratory and exploitative innovative activity for managerial and non-managerial employees as well as the influence of transparent compensation systems.

Empirical approach

A thought experiment

Our theory is based on the logic that an employee faces a set of tasks in their work. This set of tasks is determined by the employee’s role in the firm. An ideal experiment to test our theory would take the activity profile of any worker in an organization and a respective assessment of the level of risk (at the task and subsequently the employee level). Following the randomized introduction of (transparent or non-transparent) financial incentives, employees would respond by adjusting their activity set. Studying the change of the activity set, i.e., the extent to which employees change the extent to which they choose to perform more or less easy-to-measure tasks, would let us test our theoretical predictions. As data at this level of detail is difficult to obtain, we use the distinction between managers and workers to proxy for the type of activity set of the worker and observe firm-level innovative activity to proxy for the aggregate activity set of the firm’s employees. Thus, our observational study can uncover suggestive correlations consistent with our theoretical predictions.

Setting and data collection

We gathered a sample of 294 firms through telephone interviews run at LMU Munich. The sampling frame was constructed in August 2015 from the Bureau van Dijk Amadeus data set for Germany, choosing manufacturing firms with less than 6.000 employees as we were especially interested in the role of organization design in small firms. We filtered out established mid-sized companies by restricting the sample to firms with less than 1000 employees. The average firm in our sample employs 250 people (standard deviation 180).

The survey addressed production managers or similar rolesFootnote 6, because they are typically part of upper middle management allowing them insights into both day-to-day production issues and processes as well as higher level strategies and organization design. A narrowly defined group of respondents also ensures more consistent interpretation of constructs and responses (Gold et al. 2001; Lee and Choi 2003).

Following Podsakoff et al. (2003), we adopted two measures to reduce the potential risk of biased responses as much as possible. First, interviewees were assured that there were no good or bad answers, asking them to be as sincere and honest as possible. This approach aimed at reducing their fear of being evaluated and to prevent them from giving socially desirable or appropriate answers. Second, the construction of the items was very careful in trying to avoid any potential ambiguities. For this purpose, the questionnaire included simple and concise questions as well as definitions of those terms with which interviewees might be less familiar to facilitate their understanding. In line with these precautions, Harman’s single factor test (Jarvenpaa and Majchrzak 2008; Pavlou et al. 2006) also shows no evidence of bias. Including all variables in principal-component factor analysis followed by varimax rotation revealed five factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.0. Together these five factors accounted for 58% of the total variance. No single factor accounted for more than 15%. We confirmed these results for the respective subsets of variables used in any regression.

The preparation of the survey questionnaire involved several stages. First, we surveyed previous studies devoted to organizational design and innovative activity. Second, we discussed the preliminary draft with an extended group of experts (academics and practitioners) to ensure content validity. Third, five research assistants were hired to conduct the interviews by phone, following a two-stage hiring process and extensive training for 3 days regarding background, methodology, questionnaire and software. Fourth, a pilot test with 27 interviews held under realistic conditions was conducted. The questionnaire was launched after that stage.

After a 2-week period, 152 interviews had been conducted and the questionnaire was slightly adjusted, mainly in the opening questions to increase participation. An additional 142 interviews were conducted in another 2-week period. We achieved a response rate of 24% from the firms contacted by the five research analysts: a high success rate given the voluntary nature of participation and the duration of the interviews (45 min on average). 47% of the firms contacted declined an interview. For the remaining 29%, it was not possible to schedule an interview with the production manager due to time constraints. This mostly affected firms contacted towards the end of the survey period.

We checked the representativeness of the sample as well as potential non-response bias (Tomaskovic-Devey et al. 1994) using variables with known values for the sample population, such as activity sector, number of employees, sales, and profit margins (Armstrong and Overton 1977). χ2 and Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney difference tests reveal no significant differences between respondents and non-respondents.

In addition to the above measures, interview quality was secured through continuous monitoring by two supervisors who also listened in to 20% of the interviews to ensure adherence to the questionnaire and to maintain best interviewing practices. Regular team meetings further contributed to quality assurance. 95% of the interviewees consented to being recorded and all recorded interviews were second-coded by a different interviewer. Diverging evaluations in the two codings have been solved by group discussion.

We matched the survey responses with information from the firms’ annual reports retrieved from the Bureau van Dijk Amadeus database 1 year after the survey. After removing observations with missing data, we ended up with 181 firms as a basis for our analyses.

Measurement and validation of constructs

Exploitative and exploratory innovative activity

In keeping with March (1991), we treat the organization as our unit of analysis and hence consider exploitative and exploratory innovative activity at the organizational level. In line with previous research, we argue that the existence of incentives influences individual level efforts and problem solving activities, which in turn aggregate to shifts in organizational level activity (Gibson and Birkinshaw 2004; Hossain and List 2012). We thereby acknowledge the scarcity of resources at the individual level (Amabile 1996; Audia et al. 2000) leading to a trade-off between investments in exploitative and exploratory innovative activities.

Considering that organizations operate in multiple domains and that not all of these domains are tightly coupled via specialized interfaces (Gupta et al. 2006), the division of labor allows for a relatively unconstrained allocation of resources between exploitative and exploratory innovative activities (March 1991) and hence, organizations can pursue both exploitative and exploratory innovative activity. In line with previous literature (Jansen et al. 2006; Katila and Ahuja 2002), we conceptualized exploitation and exploration as two distinct dimensions of firms’ innovative activity (Nelson and Winter 1982) describing the extent to which firms use and combine existing knowledge (exploitative innovative activity) and the extent to which they add unrelated, new knowledge domains to these combinations (exploratory innovative activity).

Our measures for exploitative and exploratory innovative activity are based on items from other studies on corporate level innovative activity (He and Wong 2004; Lubatkin et al. 2006). Production managers were asked to prioritize firm’s objectives for innovation projects realized in the last 3 years using a five-point scale ranging from 1(very low) to 5(very high). Exploitation (short for exploitative innovative activity) is the unweighted average of: (a) the improvement of existing product quality, (b) the reduction of production cost, and (c) the improvement of the yield or the reduction of material consumption. Exploration (short for exploratory innovative activity) is the unweighted average of: (d) the introduction of new product generations, (e) the extension of the product range, and (f) the opening of new markets.

Financial incentives and the compensation system

To indicate whether a firm is using performance-based variable financial incentives for managers and for non-managerial production workers, we introduced two dummy variables taking value one if the answer to “is part of the financial compensation to the managers/non-managerial production workers in your firm performance-based?” was positive.Footnote 7 To measure the transparency of the compensation system, we asked production managers open questions about the design of the compensation system. The answers were then scored by the interviewers on a scale from one to five. Interviewers had a set of prepared follow-up questions to ask to establish a conversation regarding the design of the compensation system. They were also provided with anchoring answers for the scores 1, 3, and 5. Scores 2 and 4 were used for intermediate cases. The dialogue between interviewers and production managers continued until the interviewer had sufficient information to decide on a score. These measures ensured that interviewers could confidently assign a score to the respective items and generated richer insights than closed Likert scales while reducing the risk of social desirability as answers were not predefined (Bloom et al. 2011). We defined the cutoff point for a transparent compensation at answer score 4. Hence, the dummy variable transparent compensation assumes value 1 for companies with a written, detailed and transparent set of rules governing compensation. The survey instrument including the anchoring answers grid is in Appendix.

Control variables

Organizational structure plays a critical role for firms’ innovative activity (Jelinek and Schoonhoven 1990). Organizational structure captures coordination mechanisms that direct attention, resources and interdependent functions needed for innovation (Van de Ven 1986). We include variables for centralization and formalization that previous literature has found to drive exploitation and exploration (Cardinal 2001; Jansen et al. 2006), specifically by implementing ongoing incremental improvements (exploitation) through centralized decision making while encouraging more exploratory innovative activities (exploration) through decentralized decision making structures. Centralization describes the extent to which decision making is concentrated at the highest levels of hierarchy in an organization and, the (inverse) extent of organizational participation in decision making (Duncan, 1976). The formalization of processes and goals describes the organizational emphasis on following specific procedures and rules in problem solving (Duncan 1976) and the extent to which these procedures and rules are codified or written down (Khandwalla 1977).

While we used one set of questions for centralization, we combined two sets of questions in a single measure for formalization, taking the unweighted sum of the scores: one relating to the formalization of operational activities, the other to the formalization of goals. While goal setting and operational activities are different concepts in the control literature (Goold and Quinn 1990), they are both crucial to describe firms’ overall oversight behavior (McGrath 2001).

Whereas innovative activity was measured at the organizational level, we measured centralization and formalization relating to non‐managerial production workers to avoid aggregation problems (Bresnahan et al. 2002; Brynjolfsson and Hitt 1998; Mahr and Kretschmer 2010). This group of employees is relatively homogenous, large and important in manufacturing firms, so that our measures of organizational structure capture the overall degree of centralization and formalization in the surveyed firms well (Hitt and Brynjolfsson 1997).

Although all the firms in our sample can be described by the same reduced form production function (Bresnahan et al. 2002), their organizational setup differs in terms of organizational breadth and depth (Colombo and Delmastro 1999). Hierarchical levels create links in communication channels (Hull and Hage 1982) and hence hamper communication between levels and the corresponding flow of innovative ideas (Damanpour 1991). Accordingly, we included the natural logarithms of the number of hierarchy levels and the span of control (measured at the production manager level) as controls.

We also control for past firm performance by including past ROA as the average return on assets of 3 years preceding the survey. ROA is widely used in other studies of compensation (Balkin et al. 2000; Gomez-Mejia et al. 2003). We further included industry dummies to control for industry-specific environmental turbulence.

We also controlled for interviewers’ and the interviewees’ characteristics. As 95% of respondents agreed to a recording of the interviews and these interviews have been second-coded, we do not include interviewer effects for these cases to save on degrees of freedom.

By selecting a narrowly defined group of respondents, we minimized systematic bias arising from different knowledge at different hierarchical levels. However, the knowledge about the production site and the firm itself as well as the openness of respondents to share more than general information varied. We asked the interviewers to rank both respondents’ knowledge and openness on a five-item Likert scale. The standardized values were included as controls.

Analysis and results

Statistical method and analysis

We study two dependent variables of interest, exploitative and exploratory innovative activity, that both are part of a firm’s innovative activity. The errors when estimating the levels of these two dimensions are, therefore, likely to be correlated. Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression would, therefore, not provide efficient estimates, so that we need to estimate the equations on exploitative and exploratory innovative activity simultaneously. We followed Zellner’s (1962) Seemingly Unrelated Regressions (SUR) approach taking the correlation between the error terms into account and allowing us to obtain efficient estimates. A Breusch–Pagan test of independence with \({\chi }^{2}=4.469\) confirms the correlation between the errors to the 5%-confidence level justifying the choice of method.

Table 1 summarizes the descriptive statistics and correlation matrix of the variables used in the sample. Hierarchy and span of control have been transformed to their natural logarithm in the regressions, but we report the raw value in Table 1 to ease interpretation. The remaining continuous variables have been standardized to facilitate interpretation. There are 84 companies in the analyzed sample with no (variable) financial incentives in place. 20 companies have incentives for managers only, 36 have incentives for non-managerial employees only and the remaining 41 companies have financial incentives for both. 87 of the companies in the sample have a transparent compensation system, 94 do not.

The correlation matrix suggests that the correlations among the main variables are low. Calculating variance inflation factors (VIF) for all regression models confirms this. The maximum VIF was 1.77, well below the rule-of-thumb cutoff of 10 (Neter et al. 1990).

Incentives and innovative activity

Table 2 presents the results of the SUR analyses on exploitative and exploratory innovative activity. Columns 1 and 2 report the baseline model with centralization, formalization, past ROA, interviewer and interviewee controls. In Models 3 and 4 we introduce incentives for managers and incentives for workers to assess their association with corporate innovative activity.

H1a and H1b state that financial incentives for workers and managers, respectively, will be negatively related to exploratory innovative activity. In Model 4 of Table 2, the coefficient for incentives for workers \((\beta =-0.235, n.s.)\) is not significant, as is the coefficient for incentives for managers \((\beta =0.211, n.s.)\). Therefore, both, H1a and H1b are not supported and financial incentives and exploratory innovative activity are not negatively associated.

In H2a, we predict a negative relationship between financial incentives for workers and exploitative innovative activity. The negative coefficient of incentives for workers in Model 3 provides strong support for H2a \((\beta =-0.506, p<0.00)\). Likewise, the positive coefficient of financial incentives for managers in Model 3 supports H2b that financial incentives for managers are positively related to exploitative innovative activity \((\beta =0.358, p<0.03)\).

Interaction between transparent compensation and incentives

We test the interaction between a transparent compensation system and financial incentives for managers and workers in models 5 and 6 of Table 2. H3a proposes that the interaction of financial incentives for workers and a transparent compensation system is positively related to exploitative innovative activity. In Model 5 in Table 2, the coefficient of this interaction is positive and significant, supporting H3a \((\beta =0.828, p<0.01)\). This interaction term is also positive and significant in Model 6 in Table 2\((\beta =0.835, p<0.01)\), supporting H3b. The interaction of incentives for workers and a transparent compensation system is positively related with exploratory innovative activity.

The interaction terms provide insights into our non-finding regarding H1a. The positive interaction term of financial incentives and a transparent compensation system is similar in magnitude to the significant and negative linear coefficient in Model 6 \((\beta =-0.601, p<0.01)\) of Table 2. While H1a, therefore, holds if the compensation system is not transparent, the negative relation is offset if a transparent compensation system is in place.

This argument does not hold for the non-finding on H1b. Analyzing the design of the incentive scheme for managers in more detail, however, may provide some insights. Ederer and Manso (2013) find that the combination of tolerance for early failure and reward for long-term success is more effective in motivating exploration in individuals compared to fixed-wage and standard pay-for-performance incentive schemes. Given the nature of their tasks and responsibilities, standard pay-for-performance incentive schemes do not work well for managers. Instead, managers’ performance appears to be more loosely coupled to incentive pay, typically in terms of departmental performance.

Robustness and endogeneity

We ran several robustness tests by including additional measures and by changing the operationalization of existing measures. To address a potential omitted variable bias, we included the presence of non-financial incentives. For example, if financial and non-financial incentive packages would typically be offered jointly, the presence of financial incentives could simply proxy for the effect of non-financial incentives. Our variable for non-financial incentives is based on a survey question asking for the importance of non-financial incentives on a Likert-scale from 1 to 5. The results replicating the specification of models 1–4 of Table 2 are in Models 1 and 2 in Table 3, those replicating the specification of models 5–6 of Table 2 are in Models 1 and 2 in Table 4. All of our results remain economically relevant and statistically significant at the 1% to 10% level.

In columns 3 and 4 of Tables 3 and 4, respectively, we replace our 3-year measure of past performance by the ROA of the year preceding the survey. In columns 5 and 6, we disaggregate the ROA measure into its size and performance components of Total Assets and Net Income, both measured in the year preceding the survey and see that results remain unchanged. Under these specifications we even find weak support for H1a to the 10% level, namely, in Models 4 \((\beta =-0.271, p<0.08)\) and 6 \((\beta =-0.262, p<0.09)\).

In columns 7 and 8, we replace our SIC-based industry dummies with a more granular breakdown leading to 16 (instead of 5) subdivisions within manufacturing. We decided not to use the breakdown for the main analyses, but our test shows that results do not change if we do.

The self-selection effect of more able employees into jobs, where they expect their compensation to be higher (Lazear 2000b, 2005) is not expected to bias our results. While the effect surely is relevant for simple piece-rate cases, most compensation systems are more complex and especially less transparent up-front. Moreover, the German manufacturing context we study is characterized by long-lasting employment relationships making this kind of rent-seeking behavior unlikely (Rhein 2010).Footnote 8

Finally, it is plausible that while employees react rationally to changes in the firm’s incentive system, firms will also select the incentive system rationally to generate optimum output. If this were the case, there would be no variation around the independent variable and the coefficient could not identified. We believe that this concern is not fundamental to our study and its results for a number of reasons: First, we are studying the direction, not the extent, of innovative activity as our outcome variable. Most incentive systems have at their heart the goal to encourage more effort in any activity and will consider the resulting shift in relative weight placed on different activities secondary. Specifically, if a firm wanted to encourage a certain type of innovative activity, it would be much more efficient (and predictable) to simply incentivize it directly than to issue incentives based on overall performance. Second, the use of incentives, even if economically optimal, may trigger significant costs, including (social) comparison cost among employees (Nickerson and Zenger 2008). These costs are likely to be idiosyncratic to firms and may result in some firms choosing a more compressed (and less performance-sensitive) wage structure than optimal considering employees’ implied rational responses to it (Obloj and Zenger 2022). This again suggests that firms choose their incentive system as part of a set of organization design activities that constrains their choices and consequently leads to sufficient variation in incentive choices and innovation outcomes to obtain a statistically powerful and economically meaningful coefficient. What we cannot rule out, however, is the possibility that employees self-select into firms that offer variable incentive schemes. That is, workers and managers in firms with variable incentives may be systematically less (or more) inclined to engage in risky activities, leading to the results we get. Given our cross-sectional setup, we cannot address self-selection or matching by firms and employees. Indeed, we are fairly open to this mechanism being a possible driver for our result, which would not change the managerial implications of our study.

Conclusions and discussion

We examined how financial incentives for managers and workers relate to firms’ innovative activity and looked specifically at the design of the compensation system. We investigated the relation between these individual-level characteristics and firm-level innovative activity (Siggelkow and Levinthal 2003; Lavie et al. 2010). Implementing a survey method inspired by the World Management Survey (WMS), we used a detailed data set covering 181 small German manufacturing firms to study the relationship empirically.

Our study extends existing work by showing that employees at different levels (managerial or non-managerial) react differently to financial incentives regarding their focus on different types of innovative activities. Our results are consistent with the core mechanism we propose, namely, that managers face a riskier task set than non-managers on average. Furthermore, we find that transparency of the compensation system can help offset the negative effects of financial incentives on innovative activity if the expected output can be assessed accurately in the first place, which holds predominantly for non-managers. This supports our logic that uncertainty of output is due to both outcome uncertainty and assessment bias by superiors.

We contribute to knowledge on how financial incentives shape corporate search. We leverage Siggelkow and Levinthal’s (2003) concept of decentralized search in explicating the role of incentives for individuals regarding corporate exploitation and exploration, building a bridge between individual incentives and aggregate innovative activity at the firm level. This is important since organizations’ implicit choice between exploitative and exploratory innovative activity is, as March stated in his seminal paper, “buried in many features of organizational forms and customs, for example, […] in incentive systems” (1991, p. 2). We further add to the literature on (small) innovative firms by showing how opportunity-seeking and advantage-seeking activity can be motivated at the individual level and aligned at the corporate level (Hitt et al. 2001; Snow 2007).

Prior work on (financial) incentives has frequently focused on their effects on performance and productivity (Lazear 2000a; Prendergast 1999). A key contribution of our study lies in the connection of financial incentives and innovation, an interface only recently examined by few authors in specific settings, typically concentrating on individual innovation only (Baumann and Stieglitz 2014; Ederer and Manso 2013; Lee and Meyer-Doyle 2017).

We show that the relation between financial incentives and innovation is nuanced and depends on employees’ roles and the design of the compensation system. We chose production managers and production workers as prototypes at opposite ends of the task spectrum. For managers, we find a positive relationship between financial incentives and exploitative innovative activity, while the respective relationship is negative for workers. Regarding exploratory innovative activity, we do not find support for our hypotheses that the relationship is negative for both managers and workers. At least for workers, this can be explained by the interaction between incentives and the design of the compensation system: the effect of financial incentives for workers on exploratory innovative activity under a non-transparent compensation system is almost completely offset by the positive effect of financial incentives for workers on exploratory innovative activity under a transparent compensation system. We also find support for our claim that the interaction between a transparent compensation system and managerial incentives is positively related to exploitative innovative activity.

By showing if and when firms may use financial incentives to direct employee activities in line with different innovation trajectories, we qualify social psychologists’ claim that high levels of extrinsic motivation preclude high levels of intrinsic motivation and thereby crowd out innovation (Amabile 1997; Deci and Ryan 1985). Specifically, this argument only holds for exploitative innovative activity if tasks are well-defined, as for production workers, but compensation is only loosely coupled to performance (what we call a non-transparent compensation system). A transparent compensation system counteracts the negative effect so that exploitative innovative activity does not suffer from financial incentives. For a more loosely defined task design, as for a manager, we come to a result that might seem surprising at first: Exploitative innovative activity even benefits from financial incentives.

Managerial implications

The relevance of our findings for firms and decision makers lies at hand: transparency is key. Our results indicate that there does not have to be a trade-off between innovative activity and the efficiency-enhancing effect of financial incentives. Distinguishing by type of innovative activity, we show that incentives for managers even contribute to exploitative innovative activity, while we did not find a negative association with exploratory innovative activity. Incentives for workers are detrimental to both exploitative and exploratory innovative activity only if the compensation system is not transparent. This effect can be mitigated by structuring the compensation system so that incentive payments are transparent and linked to pre-defined performance criteria. Implemented with care, incentives need not harm firm innovativeness, while a positive effect is limited to exploitative innovative activity triggered by financial incentives for managers. These findings are especially important to managers of smaller firms that cannot access structural fallback options, such as the creation of separate exploitation and exploration spin-offs.

Limitations and future research directions

Our study has several limitations. First, we connect fairly coarse individual-level incentives with a firm-level analysis of exploitative and exploratory innovative activity. By design, we, therefore, assume that individual effects accumulate so they can be measured at the organizational level. While this assumption is well-established (Lavie et al. 2010; Siggelkow and Levinthal 2003), studying both individual and firm-level information would be promising. Innovative activities at the individual level will likely represent the biggest bottleneck for this research. A first-best experiment, however, would randomly assign different financial incentive schemes (target rate, piece rate, bonus groups, team incentives etc.) to individuals and measure both individual and aggregate innovative activity. Such a setup would capture both the precise effect monetary compensation systems have on innovative activity and the extent to which individual innovative activity aggregates up to firm-level innovation. Second, we cannot rule out common method bias and unobserved heterogeneity although our survey method and the temporal separation of dependent and independent variables addresses this to some extent. While our factor analysis and extensive sensitivity analyses further reduced our concerns, future work may consider repeat surveys to examine how financial incentives affect exploitative and exploratory innovative activity over time. Finally, we focus on small firms, because many alternative (structural) measures to balance explorative and exploitative innovative activity are only available to larger organizations. Extending this study to large firms to ask if financial incentives and other measures are complements or substitutes would be promising.

Notes

We interpret incentives broadly as any variable part of the overall compensation that is triggered if employees generate certain (desired) outcomes.

Some factors facilitate innovative activity in smaller firms. For example, monitoring is easier and employees may be intrinsically more motivated. Our argument posits that individual activity affects firm performance more directly and firms have fewer structural options to embed different types of innovative activity.

We use innovative activity in a broader sense than the more limited term “innovation”, which implies an activity with an implied nontrivial degree of novelty and importance to the firm. We think of innovative activity as any attempt to improve performance and distinguish between those that build on and refine existing activities and those that create “true” novelty (which would be classified as innovation in the narrow sense).

Empirically, we capture environmental turbulence by including industry fixed effects.

The analyzed sample includes 175 production managers, 2 deputy production managers, 2 CEOs, and 2 managers from different departments.

Note that we do not differentiate between long- and short-term incentives, their magnitude, or other more subtle sources of heterogeneity across incentive schemes. While this would add richness to our data, our limited sample size would make it difficult to estimate differential correlations depending on the type and extent of incentive schemes. This would make for promising future research. Note also that this was the initial question posed by the interviewer. In keeping with the semi-structured nature of the interviews, interviewers could ask follow-up questions until they were satisfied that performance-based compensation was indeed variable and designed to give performance incentives.

To the extent that a transparent or non-transparent compensation system could be an indicator of organizational culture, we might get self-selection effects in this dimension. Unfortunately, in our cross-sectional data, we do not have a way of controlling for that.

References

Ahuja G, Lampert CM, Tandon V (2008) Moving beyond Schumpeter: management research on the determinants of technological innovation. Acad Manag Ann 2:1–98

Amabile TM (1996) Creativity in context: update to “the social psychology of creativity.” Westview Press, Boulder

Amabile TM (1997) Motivating creativity in organizations: on doing what you love and loving what you do. Calif Manage Rev 40:39–58

Amabile TM, Pillemer J (2012) Perspectives on the social psychology of creativity. J Creat Behav 46:3–15

Andriopoulos C, Lewis MW (2009) Exploitation-exploration tensions and organizational ambidexterity: managing paradoxes of innovation. Organ Sci 20:696–717

Armstrong JS, Overton TS (1977) Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. J Market Res 14:396–402

Aschenbrücker K, Kretschmer T (2018) Balanced Control as an Enabler of Organizational Ambidexterity, In: Organization Design, Advances in Strategic Management. Emerald Publishing Limited, p. 115–144

Audia PG, Locke EA, Smith KG (2000) The paradox of success: an archival and a laboratory study of strategic persistence following radical environmental change. Acad Manag J 43:837–853

Auh S, Menguc B (2005) The influence of top management team functional diversity on strategic orientations: the moderating role of environmental turbulence and inter-functional coordination. Int J Res Mark 22:333–350

Balkin DB, Markman GD, Gomez-Mejia LR (2000) Is CEO pay in high-technology firms related to innovation? Acad Manag J 43:1118–1129

Bandiera O, Barankay I, Rasul I (2007) Incentives for managers and inequality among workers: evidence from a firm-level experiment. Quart J Econ 122:729–773

Baumann O, Stieglitz N (2014) Rewarding value-creating ideas in organizations: the power of low-powered incentives. Strateg Manag J 35:358–375

Beckman CM, Haunschild PR, Phillips DJ (2004) Friends or strangers? Firm-specific uncertainty, market uncertainty, and network partner selection. Organ Sci 15:259–275

Benner MJ, Tushman ML (2003) Exploitation, exploration, and process management: the productivity dilemma revisited. Acad Manag Rev 28:238–256

Bloom N, Van Reenen J (2007) Measuring and explaining management practices across firms and countries. Quart J Econ 122:1351–1408

Bloom N, Kretschmer T, Van Reenen J (2011) Are family-friendly workplace practices a valuable firm resource? Strateg Manag J 32:343–367

Bresnahan TF, Brynjolfsson E, Hitt LM (2002) Information technology, workplace organization, and the demand for skilled labor: firm-level evidence. Quart J Econ 117:339–376

Brynjolfsson E, Hitt L, (1998) Information Technology and Organizational Design: Evidence from Micro Data. Working Paper, MIT Cambridge, MA

Cardinal LB (2001) technological innovation in the pharmaceutical industry: the use of organizational control in managing research and development. Organ Sci 12:19–36

Charness G, Grieco D (2019) Creativity and financial incentives. J Eur Econ Assoc 17:454–496

Colombo MG, Delmastro M (1999) Some stylized facts on organization and its evolution. J Econ Behav Organ 40:255–274

Damanpour F (1991) Organizational innovation: a meta-analysis of effects of determinants and moderators. Acad Manag J 34:555–590

Deci EL, Ryan RM (1985) The general causality orientations scale: self-determination in personality. J Res Pers 19:109–134

Dosi G (1988) Sources, procedures, and microeconomic effects of innovation. J Econ Lit 26:1120–1171

Duncan RB (1976) The Ambidextrous organization: designing dual structures for innovation. In: Kilmann RH, Pondy LR, Slevin D (eds) The management of organization. North-Holland, New York, pp 167–188

Ederer F, Manso G (2013) Is pay for performance detrimental to innovation? Manage Sci 59:1496–1513

Failla V, Amore M (2020) Pay dispersion and executive behaviour: evidence from innovation. Br J Manag 31:487–504

Fairbank JF, Williams SD (2001) Motivating creativity and enhancing innovation through employee suggestion system technology. Creat Innov Manag 10:68–74

Fleming L, Sorenson O (2001) Technology as a complex adaptive system: evidence from patent data. Res Policy 30:1019–1039

Gibson CB, Birkinshaw J (2004) The antecedents, consequences, and mediating role of organizational ambidexterity. Acad Manag J 47:209–226

Gold AH, Malhotra A, Segars AH (2001) Knowledge management: an organizational capabilities perspective. J Manag Inf Syst 18:185–214

Gomez-Mejia LR, Larraza-Kintana M, Makri M (2003) The determinants of executive compensation in family-controlled public corporations. Acad Manag J 46:226–237

Goold M, Quinn JJ (1990) The paradox of strategic controls. Strateg Manag J 11:43–57

Gupta AK, Smith KG, Shalley CE (2006) The interplay between exploration and exploitation. Acad Manag J 49:693–706

Haas MR (2010) The double-edged swords of autonomy and external knowledge: analyzing team effectiveness in a multinational organization. Acad Manag J 53:989–1008

Hackman JR, Oldham GR (1976) Motivation through the design of work: test of a theory. Organ Behav Hum Perform 16:250–279

He Z-L, Wong P-K (2004) Exploration vs. exploitation: an empirical test of the ambidexterity hypothesis. Organ Sci 15:481–494

Heiner RA (1986) Uncertainty, signal-detection experiments, and modeling behavior. Langlois (ed.): Economics as a Process. Essays in the New Institutional Economics 59–115

Hitt LM, Brynjolfsson E (1997) Information technology and internal firm organization: an exploratory analysis. J Manag Inf Syst 14:81–101

Hitt MA, Ireland RD, Camp SM, Sexton DL (2001) Strategic entrepreneurship: entrepreneurial strategies for wealth creation. Strateg Manag J 22:479–491

Hitt MA, Ireland RD, Sirmon DG, Trahms CA (2011) Strategic entrepreneurship: creating value for individuals, organizations, and society. Acad Manag Perspect 25:57–75

Hossain T, List JA (2012) The behavioralist visits the factory: increasing productivity using simple framing manipulations. Manage Sci 58:2151–2167

Huber GP (1991) Organizational learning: the contributing processes and the literatures. Organ Sci 2:88–115

Hull F, Hage J (1982) Organizing for innovation: beyond burns and stalker’s organic type. Sociology 16:564–577

Ireland RD, Hitt MA, Sirmon DG (2003) A model of strategic entrepreneurship: the construct and its dimensions. J Manag 29:963–989

Jansen JJP, Van Den Bosch FAJ, Volberda HW (2005) Managing potential and realized absorptive capacity: how do organizational antecedents matter? Acad Manag J 48:999–1015

Jansen JJP, Van Den Bosch FAJ, Volberda HW (2006) Exploratory innovation, exploitative innovation, and performance: effects of organizational antecedents and environmental moderators. Manage Sci 52:1661–1674

Jarvenpaa SL, Majchrzak A (2008) Knowledge collaboration among professionals protecting national security: role of transactive memories in ego-centered knowledge networks. Organ Sci 19:260–276

Jelinek M, Schoonhoven CB. (1990) Managing innovation in high technology firms: challenges to organization theory. In Gomez-Mejia LR, Lawless MW (Eds.), Organizational Issues in High Technology Management. Monographs in Organizational Behavior and Industrial Relations, vol. 11, pp. 3–17

Katila R, Ahuja G (2002) Something old, something new: a longitudinal study of search behavior and new product introduction. Acad Manag J 45:1183–1194

Ketchen DJ, Ireland RD, Snow CC (2007) Strategic entrepreneurship, collaborative innovation, and wealth creation. Strateg Entrep J 1:371–385

Khandwalla PN (1977) The design of organizations. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York

Khashabi P, Heinz M, Zubanov N, Kretschmer T, Friebel G (2021) Market competition and the effectiveness of performance pay. Organ Sci 32:334–351

Kieser A, Ebers M (2014) Organisationstheorien, 7th edn. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart

Kohn A (1993) Why incentive plans cannot work. Harv Bus Rev 71:54–60

Kohn A (1999) Punished by rewards: the trouble with golden stars, incentive plans, A’s, praise, and other bribes. Houghton Mifflin, New York

Kreps DM (1997) Intrinsic motivation and extrinsic incentives. Am Econ Rev 87:359–364

Laureiro-Martínez D, Brusoni S, Canessa N, Zollo M (2015) Understanding the exploration-exploitation dilemma: an fMRI study of attention control and decision-making performance. Strateg Manag J 36:319–338

Lavie D, Rosenkopf L (2006) Balancing exploration and exploitation in alliance formation. Acad Manag J 49:797–818

Lavie D, Stettner U, Tushman ML (2010) Exploration and exploitation within and across organizations. Acad Manag Ann 4:109–155

Lazear EP (2000a) The power of incentives. Am Econ Rev 90:410–414

Lazear EP (2000b) Performance pay and productivity. Am Econ Rev 90:1346–1361

Lazear EP (2005) Output-based pay: incentives, retention, or sorting? Res Labor Econ 23:1–25

Lee H, Choi B (2003) Knowledge management enablers, processes, and organizational performance: an integrative view and empirical examination. J Manag Inf Syst 20:179–228

Lee S, Meyer-Doyle P (2017) How performance incentives shape individual exploration and exploitation: evidence from micro-data. Organ Sci 28:19–38

Levinthal DA, March JG (1993) The myopia of learning. Strateg Manag J 14:95–112

Lewin AY, Long CP, Carroll TN (1999) The coevolution of new organizational forms. Organ Sci 10:535–550

Lin Z, Yang H, Demirkan I (2007) The performance consequences of ambidexterity in strategic alliance formations: empirical investigation and computational theorizing. Manage Sci 53:1645–1658

Lin H-E, McDonough EF, Lin S-J, Lin CY-Y (2013) Managing the exploitation/exploration paradox: the role of a learning capability and innovation ambidexterity. J Prod Innov Manag 30:262–278

Lubatkin MH, Simsek Z, Ling Y, Veiga JF (2006) Ambidexterity and performance in small-to medium-sized firms: the pivotal role of top management team behavioral integration. J Manag 32:646–672

Mahr, F., Kretschmer, T., 2010. Complementarities between IT and Organizational Structure: The Role of Corporate Exploration and Exploitation. Münchener Wirtschaftswissenschaftliche Beiträge (BWL).

March JG (1991) Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organ Sci 2:71–87

March JG (2006) Rationality, foolishness, and adaptive intelligence. Strateg Manag J 27:201–214

McGrath RG (2001) Exploratory learning, innovative capacity, and managerial oversight. Acad Manag J 44:118–131

Mom TJM, Van Den Bosch FAJ, Volberda HW (2007) Investigating managers’ exploration and exploitation activities: the influence of top-down, bottom-up, and horizontal knowledge inflows. J Manage Stud 44:910–931

Mom TJM, van den Bosch FAJ, Volberda HW (2009) Understanding variation in managers’ ambidexterity: investigating direct and interaction effects of formal structural and personal coordination mechanisms. Organ Sci 20:812–828

Nelson RR, Winter SG (1982) The Schumpeterian Tradeoff Revisited. Am Econ Rev 72:114–132

Neter J, Wasserman W, Kutner M (1990) Applied linear statistical models, 2nd edn. Irwin, Boston

Nickerson JA, Zenger TR (2008) Envy, comparison costs, and the economic theory of the firm. Strateg Manag J 29:1429–1449. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.718

Nohria N, Gulati R (1996) Is slack good or bad for innovation? Acad Manag J 39:1245–1264

O’Reilly CA, Tushman ML (2011) Organizational ambidexterity in action—how managers explore and exploit. Calif Manag Rev 53:5–22

O’Reilly CA, Tushman ML (2013) Organizational ambidexterity: past, present, and future. Acad Manag Perspect 27:324–338

Obloj T, Zenger T (2022) The influence of pay transparency on (gender) inequity, inequality, and the performance-basis of pay. Nat Hum Behav 6(5):646–655

Osterloh M, Frey BS (2000) Motivation, knowledge transfer, and organizational forms. Organ Sci 11:538–550

Pavlou PA, Liang H, Xue Y (2006) Understanding and mitigating uncertainty in online environments: a principal-agent perspective. MIS Q 31:105–136

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, Podsakoff NP (2003) Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol 88:879

Prendergast C (1999) The provision of incentives in firms. J Econ Lit 37:7–63

Puranam P, Alexy O, Reitzig M (2014) What’s “new” about new forms of organizing? Acad Manag Rev 39:162–180

Raisch S, Birkinshaw J (2008) Organizational ambidexterity: antecedents, outcomes, and moderators. J Manag 34:375–409

Raisch S, Birkinshaw J, Probst G, Tushman ML (2009) Organizational ambidexterity: balancing exploitation and exploration for sustained performance. Organ Sci 20:685–695

Recht R, Wilderom C (1998) Kaizen and culture: on the transferability of Japanese suggestion systems. Int Bus Rev 7:7–22

Rhein T (2010) Beschäftigungsdynamik im internationalen Vergleich: Ist Europa auf dem Weg zum “Turbo-Arbeitsmarkt”? IAB-Kurzbericht 2010(19):1–6

Rothaermel FT, Deeds DL (2004) Exploration and exploitation alliances in biotechnology: a system of new product development. Strateg Manag J 25:201–221

Shearer B (2004) Piece rates, fixed wages and incentives: evidence from a field experiment. Rev Econ Stud 71:513–534

Sidhu JS, Volberda HW, Commandeur HR (2004) Exploring exploration orientation and its determinants: some empirical evidence. J Manage Stud 41:913–932

Siggelkow N, Levinthal DA (2003) Temporarily divide to conquer: centralized, decentralized, and reintegrated organizational approaches to exploration and adaptation. Organ Sci 14:650–669

Siggelkow N, Rivkin JW (2005) Speed and search: designing organizations for turbulence and complexity. Organ Sci 16:101–122

Smith WK, Tushman ML (2005) Managing strategic contradictions: a top management model for managing innovation streams. Organ Sci 16:522–536

Snow CC (2007) Innovation. Strat Entrepreneurship J 1:101–102

Taylor A, Greve HR (2006) Superman or the fantastic four? Knowledge combination and experience in innovative teams. Acad Manag J 49:723–740

Tomaskovic-Devey D, Leiter J, Thompson S (1994) Organizational survey nonresponse. Adm Sci Q 39:439–457

Tushman ML, O’Reilly CA (1996) The ambidextrous organizations: managing evolutionary and revolutionary change. Calif Manage Rev 38:8–30

Van de Ven AH (1986) Central problems in the management of innovation. Manage Sci 32:590–607

Voss GB, Sirdeshmukh D, Voss ZG (2008) The effects of slack resources and environmental threat on product exploration and exploitation. Acad Manag J 51:147–164

Wadhwa A, Kotha S (2006) Knowledge creation through external venturing: evidence from the telecommunications equipment manufacturing industry. Acad Manag J 49:819–835

Winter SG (1984) Schumpeterian competition in alternative technological regimes. J Econ Behav Organ 5:287–320

Zellner A (1962) An efficient method of estimating seemingly unrelated regressions and tests for aggregation bias. J Am Stat Assoc 57:348–368

Zimmermann A, Raisch S, Birkinshaw J (2015) How is ambidexterity initiated? The emergent charter definition process. Organ Sci 26:1119–1139

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Survey items for organization design variables

-

(1)

Transparent compensation

Note: Dummy variable assumes value 1 for scores 4 and 5, 0 otherwise.

Prepared questions | ||

How is the salary composition and salary level determined? How transparent are the remuneration models? Do all the employees know why they make how much? To which extent do collective bargaining agreements, operating agreements and other voluntary agreements affect your company’s remuneration? Are there fixed salary bands? Are performance indicators or KPIs the basis for remuneration decisions? … and for promotion decisions? How exactly does this look like? | ||

Example answer for score 1 | Example answer for score 3 | Example answer for score 5 |

The award of promotions, pay increases or bonuses is not transparent | In the company, there are some established and well-known patterns of remuneration, e.g., salary bands, collective agreements (e.g., ERA) | There is a written, detailed and transparent set of rules that regulates remuneration and promotion. This is done, e.g., on the basis of regularly collected and tracked performance indicators |

-

(2)

Centralization of decision making

Prepared questions | ||

Who takes important production decisions at your site? Do you delegate these decisions to your employees, do you have to coordinate with your superior or do you take them yourself? Imagine that production should be increased by 10% per day by means of overtime or increased production speed—who decides if and how? Who determines the weekly production targets? Imagine production batches, setup and idle times would need to be determined. Who takes these decisions? Let’s assume the product-lineup at your site would be changed or adjusted. How would that work? Who would initiate this process, who would be involved and who would take the final decision? | ||

Example answer for score 1 | Example answer for score 3 | Example answer for score 5 |

Most production and process decisions are being delegated to the executing position | The majority of decisions remains with me or they are delegated and taken by top management to roughly the same extent | Decisions are mostly taken by top management and handed down |

-

(3)

Formalization of processes and goals

Prepared questions | ||

In which way are tasks and processes defined in your firm? I’m particularly interested in how structured and formalized tasks and processes are designed What is the role of certifications like, e.g., ISO9001 with regard to task design? How do you deal with changes in tasks or assignments? Could you elaborate on an example? How formalized is this process? | ||

Example answer for score 1 | Example answer for score 3 | Example answer for score 5 |

There are no formal tools defining tasks. Responsibilities and workflow are often unclear. Employees carry out their tasks without detailed instructions. Adjustments are being made on a spontaneous and autonomous basis | Tasks and workflows are roughly defined. The precise design of workflows and their adjustments are not arranged in detail. In general, adjustments do not require internal approval | There are comprehensive written job descriptions for the majority of tasks. Responsibilities and workflows are formally defined by, e.g., manuals, formal job analysis or ISO certification (score 4–5) and adjustments do require internal approval |

Prepared questions | ||

Are these corporate goals [discussed in the previous section] written down? If so, in which way? In which way are these goals being communicated to employees? In which way do you measure and track goal achievement? What is the role of key performance indicators (KPI) in this context? Could you please name an example? Do you adjust the goals based on last period’s goal achievement? | ||

Example answer for score 1 | Example answer for score 3 | Example answer for score 5 |

Planning and controlling happen on an ad hoc basis. The selection of goals/KPIs takes place in a non-systematic way (if at all).Goals are not written down and goal achievement is not tracked with methodical sophistication. Communication of goal achievement is informal and without consequences. Deviations from goals are not scrutinized or do not lead to adjustments | Planning and controlling are systematic. Goals are written down and goal achievement is tracked (even if in part rudimentarily). Budgets and goals are based on past performance and are not adjusted during the year | Planning and controlling are integral components of corporate strategy and culture. An extensive KPI-system, quality matrices or balance score cards etc. are essential for management and potentially integrated in an IT system. There are clear reporting structures and guidelines. Deviations from goals are under permanent scrutiny and may i.a. be used for adjustments during the year |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Aschenbrücker, K., Kretschmer, T. Performance-based incentives and innovative activity in small firms: evidence from German manufacturing. J Org Design 11, 47–64 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41469-022-00124-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41469-022-00124-8