Abstract

The substantive view of the ancient economy argues that social considerations and especially the quest for status featured prominently in ancient Greece. Paying for liturgies, the private finance of public expenditure by wealthy individuals, offered the opportunity to acquire status by choosing the level of contributions to outperform rival providers. Effectively, liturgies were a system of finance of public provision through redistributive taxation sidestepping state administration of taxes and expenditures. Applying the insights of the economic approach to status, the paper examines status competition in ancient Athens and compares paying for liturgies with a hypothetical system of explicit income taxation of the rich. It is concluded that status seeking increased aggregate provision of public goods. The results formalise important aspects of substantivism and illustrate the value of formal economic analysis in the investigation of the ancient Greek economy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

People care about status, their relative position in society, because of the honour it carries and because it brings wealth and power. Vying for status and being jealous of each other, people enter social contests whose results establish the position of the elites in political and social hierarchies. It does not come as a surprise to read that notions of status, glory, honour and envy were fixtures of the values of the ancient Greek society, as the opening quote says. The present paper studies status seeking by integrating economic, political and social factors and shows how competition for individual status may improve social outcomes. Although the focus is ancient Greece the analysis of the paper is of broader interest as it studies important aspects of status seeking behaviour.

According to the prominent ancient historian Moses Finley the ancient decision-maker strived to maximise status rather than income or profits. But Finley saw status as “an admirably vague word with considerable psychological element” (1979:51). He continued: “a model of economic choices … in antiquity would give considerable weight to this factor of status. I do not say it was the only factor that it weighed equally with all members of any order or status-group, nor do I know how to translate what I have said into a mathematical equation” (ibid:60). The present study takes up the latter challenge and studies formally status seeking in ancient Greece by employing the insights of modern economic literature to status.

Finley’s so-called substantivist view that economic activities in antiquity were embedded in the political, social and religious spheres has been immensely influential in shaping the debate about the nature of the ancient economy. However, his emphasis on the significance of social values and his legacy of rejecting the applicability of profit maximisation to the ancient economy has led, perhaps inadvertently, to a more extreme rejection of the suitability of formal economic modelling to investigate the ancient economy. This is unfortunate because it has deprived the development of a complete understanding of several issues of interest which can be pursued more carefully by using a formal framework. The concern here is to trace carefully some aspects of status contests in ancient Greece, and especially Athens, by a suitable formal economic model which uses tools and insights of modern theory.

The investigation considers individuals engaging in acts which elevate their social status among their peers by paying for liturgies (literally, works for the people), a specific institution by which rich individuals were obliged to privately finance the provision of public goods and services including defence, and benefited payers and non-payers alike. The analysis explicitly recognises that (a) when status is desirable, individuals may increase their status by using up resources which can serve other objectives, (b) the status of an individual depends on the amount of resources spent to acquire status in comparison to what other individuals spend, and (c) the outcome of status contests by performing liturgies is comparable to a system of tax payment for public services. The analysis shows that although the quest for status was a negative externality for the contestants, it generated social benefits, because private spending for status was channelled to finance public provision.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews modern economics literature on status whose insights guide the present inquiry focusing on early economics contributions to status concerns, how contemporary research formalises status seeking, and the presumed effects of status seeking on income distribution. Section 3 introduces the basic elements of the debate between substantivism and formalism regarding the nature of the ancient Greek economy. Section 4 describes juridically defined status groups, that is, the tripartite distinction citizens-metics-slaves, where different groups enjoy different formal legal rights, and group membership is formally and rigidly delineated; it then looks at factors whose presence conferred high social esteem to citizens and especially the ideal of land ownership. Section 5 discusses liturgies which in the competitive society of ancient Greece featured prominently as a stage for the pursuit of status. Section 6 examines a formal choice model of the quest for status, where status is defined as the relative position of the individual on the social ladder, by paying for liturgies. It shows how paying for liturgies generated significant positive externalities to poorer individuals who benefited from the largess of the status seekers, a result of wider interest and importance. It then compares the size of public provision under liturgies to its analogue under income tax payments by the rich. Section 7 concludes.

2 A Selective Review of the Economics of Status

2.1 Precursors

Throughout history people have desired status intrinsically, because they like it, and instrumentally, because it enables them to do things that they otherwise could not do (Frank and Heffetz 2011). Status considerations mean that the individual is concerned with his or her relative position on the social ladder. Weiss and Fershtman (1998 p. 802) define social status as “a ranking of individuals (or groups of individuals) in a given society, based on their traits, assets, and actions.” Status-seeking has a long pedigree in modern economic thought and has spawned a large and expanding theoretical and empirical literature. Veblen (1899) spoke of social recognition and prestige as the chief motives of human action. In what has become known as the relative income hypothesis of consumption, Duesenberry (1949) theorised that individual consumption is influenced by that of one’s neighbours. Hirsch (1976) saw the pursuit of social position as an important determinant of utility, while Pollak (1976) uncovers the properties of static and dynamic models of consumer preferences which depend on other people's past consumption.

The so-called “Easterlin paradox” and the work of Kahneman and Tversky (1979) generated further impetus to research on status. Easterlin (1974) found that, contrary to the prediction of standard theory, despite substantial real income growth in Western countries reported happiness levels did not increase. Kahneman and Tversky (1979) explained that decisions are affected by changes from a reference point rather than absolute states of wealth. In the context of status, the reference point is the average income or consumption of other individuals in a group used for comparisons (see Frey and Stutzer 2005, and Clark et al. 2008 for wide ranging reviews of how relative income may affect individual happiness). Queries about the economic effects of status are part of the “happiness literature”, a research program closely related to behavioural economics. Behavioural economics incorporates insights from psychology into economic behaviour to investigate how individuals actually behave when they are characterised by bounded rationality and biased preferences, as opposed to how they would behave if they had perfect foresight.

2.2 Status Seeking and Utility

Concern with relative position introduces a negative externality into the standard utility maximisation framework. Formalization of status considerations by augmenting the utility function rests on the contention of behavioural economics that individual preferences are, to some degree at least, endogenous (or “internal”) to the particular institutional and social context where actions take place, and are shaped by ideologies including religion (see Bowles 1998 and Hargreaves Heap 2013 for surveys of the theoretical literature and evidence from experiments). Individuals may be motivated by ethical considerations and possess social preferences such as altruism or envy, reciprocity, intrinsic motivation and a desire to uphold ethical norms. Thus, individual preferences are not confined to material self-interests only, as formation of preferences is part of the process of socialization (Postlewaite 2011).

Frank and Heffetz (2011) reviewed the empirical work on the hypothesis that people care about their status in society. They concluded that there is plenty of evidence to support the hypothesis that preferences for status are an important determinant of economic outcomes. They point to three main features of social status which confer utility to the individual, positionality (or rank), desirability, and non-tradability. Since status is positional, it enters the utility function as a positional good, that is, as a good whose value depends on how it compares with the quantity of that good owned by others. Specifically, an agent’s utility depends negatively on what others have. As a result, competition for status leads individuals to spend on status-promoting activities but such expenses affect the distribution of status without creating social gains. Status-seekers will tend to overinvest in status-promoting activities creating deadweight losses for the society. Second, status is desirable, because it represents a means to acquire other resources (for example, a person of high status can access resources that are not available to those of lower status, may command authority and respect, etc.). Third, status is non-tradable, in the sense that since it is the society which confers status, there is no explicit market where one can “buy” it.

Like economic rents, the quest for status generates status-seeking activities. Frank (1985) shows that status seekers tend to overinvest in status seeking activities, which redistribute rather than create wealth. However, contrary to the negative externality effects of the status-seeking game, Congleton (1989) observes that many contests for status generate benefits for individuals not participating in the contest, like higher consumption of entertainment, or technological externalities in the form of knowledge which reduces the cost of producing both status and non status goods. Further, he shows that “micro-status games”, that is, contests where the number of status-seekers is smaller than the population (like a footrace), which generate deadweight losses over time will tend to be replaced by games which generate positive externalities. However, no such clear-cut conclusion arises in the case of “macro-status games”, where all members of society gain or lose status from the activities involved. Since all members of the society participate in macro-status games, individual incentives to devise new, more efficient, status games diminish. For example, if status is determined by holdings of productive capital, and capital is accumulated through saving and entrepreneurship, the status game leads to higher production. But if status is determined by consumption, or abstinence from worldly activities, or emerging victorious from conflicts, welfare enhancing effects are absent.

2.3 Effects of Status Seeking on Income Distribution

Turning to how status concerns may affect government policy, Pham (2005) examines the distribution of wealth and the formation of fiscal policy using a two-class inter-temporal growth model where individuals care about both consumption and social status, which is assumed to increase with individual wealth but decrease with average wealth. He finds that individuals with stronger status motive, rather than wealth endowment, end up holding a higher level of wealth. Moreover, if one class has a stronger incentive to accumulate wealth, higher wealth inequality is associated with higher growth, but a higher growth rate may reduce welfare of one class of agents and increase welfare of the other one. Finally, his model predicts that when the fiscal policy is endogenously determined through a voting mechanism, an increase in the strength of the status motive of the majority class may lead to a political-equilibrium characterised by a lower growth rate.

Charness et al. (2013) used experiments to examine whether the quest for status leads to unethical activities such as sabotage or cheating to improve one’s ranking. They found that people care about their relative position, and that social comparisons even in the absence of monetary rewards increase motivation for work. However, they also report evidence that some individuals increase their rank by expending resources to sabotage other people’s work, to the detriment of group performance. Chaudry and Garner (2013) show that a greater degree of inside country income comparison leads to policies which limit the risk that the rich may become poor but this bias leads to lower growth. On the other hand, a greater degree of income comparison between the home country and foreign countries leads to greater growth.

Gershman (2014) explores the combined effects of actual inequality, tolerance to inequality and opportunities for investment on growth. He investigates a two-stage dynamic envy game between two individuals. In the first stage each individual may choose to allocate part of his time to productive investment, which in combination with his endowment, raises his future productivity. In the second stage the individual divides his time between own production and the disruption of the other individual’s production process. If the initial inequality in the distribution of endowments is low, tolerance for inequality (which is determined by the level of protection of property rights) is high, and peaceful investment opportunities are abundant, then in equilibrium individuals compete peacefully for their status resulting in high effort and output, a so-called “keeping up with the Joneses” equilibrium. On the other hand, if initial inequality is high, tolerance for inequality is low, and investment opportunities are scarce, the resulting “fear” equilibrium is one where the better endowed individual lowers effort to avoid destructive envy of the relatively poor. Finally, if inequality is high, tolerance for inequality is very low, and the productivity of investment is low, a “destructive” equilibrium arises, where there is actual conflict and time is used unproductively to destroy property.

Jaikumar et al. (2018) argue that conspicuous consumption might result in an improved sense of economic well-being, as it allows households to signal higher social status and their ability to ‘keep up with the Joneses’. They provide evidence that this is indeed the case and this effect is even more pronounced among households at the bottom of the income pyramid.

3 The Nature of the Ancient Greek Economy

The nature of the ancient Greek economy has been the subject of a long scholarly debate between the primitivist-substantivist and the modernist-formalist schools of thought. Starting in 1893 with Karl Bücher, building on Max Weber’s analysis and culminating with the writings of Finley, the primitivist-substantivist view considered the economy as embedded in politics and religion, with actors lacking interests in profit maximization, enterprise and growth. Production remained small-scale focused on household activity in pursuit of self-sufficiency at the household and city-state level, exchanges were based on reciprocity and redistribution via the state rather than the market, and individual choices were determined by social values (for extension and embellishments of this view, see Humphreys 1970; Austin and Vidal-Naquet 1977; Millet 1991; Sallares 1991; Engen 2010). On the other hand, the modernist-formalist view inspired by 1895 Eduard Meyer’s reply to Bücher argues that the ancient economy was market-based, populated by specialised production units, relied on inter-connected markets independent of social relations, employed sophisticated contracts of exchange, and ran according to commercial principles (Burke 1992; Cohen 1992; Harris 2002; Amemiya 2007).

Finley has been hugely influential in the study of the ancient Greek economy. His substantivist theory denies that the ancient economy existed as an area of activity independent of social relations, and rejects that standard economics has anything to contribute to the analysis of the ancient economy.Footnote 1 In Finley's view, the value system of ancient Greece which emphasised the wellbeing of the community over that of the individual dominated individual actions and as a result economic activities were subordinate to social and political pursuits. We may breakdown Finley’s view into two essential elements, a theoretical and an empirical. The theoretical is that the economy was embedded in religion and politics; the empirical was that the economy did not grow. By now a large body of historical evidence has revealed that the latter assertion does not stand up to scrutiny: During the period 800–300 BCE, ancient Greece experienced an unprecedented efflorescence characterised by significant population growth, rise in the standard of living, urbanisation and cultural achievements (see Morris 2004; Scheidel 2010; Harris and Lewis 2015; Ober 2015; Bresson 2016). However, there is value in the theoretical argument that the economy was embedded, since all economies are conditioned on their socio-cultural and institutional environments.

Whether economic activity may or may not be dominated by politics is taken up by North et al. (2009). They consider the link between economics and politics as a fundamental part of the long-run development process (although they left the nature of the ancient economy out of their book). They draw a distinction between natural or limited access and open access order states. Natural, states are those where “personal relationships, who one is and who one knows, form the basis of social organization and constitute the arena for individual interaction” (p. 13) and entail economies embedded in social relationships. They consider all states as natural states up to the fifteenth or sixteenth centuries (p. 164). On the contrary, in an open access order, “impersonal categories of individuals interact over a wide area of social behaviour with no need to be cognizant of the individual identity of their partners” (ibid: 2); an open access order implies a market or disembedded economy. Centralised Sparta and Macedon were probably typical natural states; however, during the fifth and fourth centuries, democratic and economically successful Athens, where free and politically equal (male only) citizens collectively governed the polis, was not a natural state but had transformed to an open access state (Ober 2015; Carugati et al. 2019). This embedded v disembedded part of the debate still animates research in the ancient Greek economy.Footnote 2

4 Status in Ancient Greece

4.1 Juridical Status

In Finley’s view of the ancient society “invariably what are conventionally called ‘class struggles’ in antiquity prove to be conflicts between groups at different points in the spectrum disputing the distribution of specific rights and privileges” (1979:68). Specifically, drawing on Max Weber, Finley rejected the term “class” in its Marxist sense of “class struggle” and “class exploitation” as an explanation of ancient social and economic relations, and emphasises the presence of “orders”. Order is “a juridically defined group within a population, possessing formalized privileges and disabilities in one or more fields of activity, governmental, military, legal, economic, religious, marital, and standing in a hierarchical relation to other orders” (Finley 1979:45, emphasis in the original).Footnote 3

In ancient Athens, the richest and best documented ancient Greek polis, juridical status described the distinction between the free citizens enjoying full political and civic rights and two groups lacking such rights, foreign-born residents called “metics”, and slaves. Hansen (1999:86) writes “The division shows that Athens was a society based on ‘orders’ rather than ‘classes’, for the tripartition was by legal status, i.e. it was based on privileges, or otherwise, protected by law. Membership of a group was typically inherited.”Footnote 4 Stylistically, land-owning citizens were farmers. The landless poor found employment in the navy and the crafts, and drew payments from the state when serving in public posts. Slaves were the property of their masters; however, they could not be killed by their masters and could seek asylum in designated shrines and then ask to be sold to other masters. Slaves were used in domestic services and as skilled and unskilled labour in the farms, workshops and mines, but after paying their masters they could work on their own account in the crafts and the services including banking. However, they were not protected by the courts; their testimonies were accepted only if extracted by torture, and were given physical punishments which were forbidden for free citizens. Metics were artisans and traders, but could also work as farm tenants; they had to choose an Athenian citizen as a sponsor, paid special poll taxes, were required to serve in the army and were not allowed to own land or houses.

Yet another legal distinction within the free citizen body was that between male and female. Women had no political rights, neither did they participate in the assemblies of the demos, nor did they occupy political office. In legal matters they were represented by a male guardian, father, husband, or relative. The decision to marry was taken by their fathers. The legislation regarding dowries of divorced women, or married women if died childless, and properties of heiresses without brothers aimed to ensure that property would remain within the family rather than going to outsiders. Nor could women run commercial enterprises, although Spartan women enjoyed more freedom in managing estates, as Spartan men were preoccupied with military interests.

5 Economic Pursuits and Relative Social Status

The focus of this study is the actions which individuals may take to gain social status, in the sense of achieving higher relative position and commanding respect. We therefore leave aside juridical status which was rigid allowing little, if any, room for individual choiceFootnote 5 and turn to status as relative social standing among free citizens, which in the context of ancient Greece connoted honour (timê). We focus on the factors which chosen by the individual could bring high social status.

Millet (2000) argues that around the Aegean Sea about half the total population earned its living from farming. In ancient Greece the basic unit of economic and social organization was the household (oikos) comprising, the house as a building, its land and equipment, the persons living in the house and their belongings. The land-owning elite viewed wealth from commercial and industrial activities with contempt, and disdained dependent work as unbecoming for a free man. Possession of large tracts of land was the most important determinant of status. Self-employed free artisans and traders offered their services as independent operators rather than employees for limited tasks and times, and for different clients. Further, craftsmen who earned their living from manual labour were held in low social esteem, because they performed vulgar or brutal (“banausic”) work. Finley argued that the traditional values of the elite in favour of possession of agricultural land and participation into political activity are found in the literary evidence, and prevailed from the time of Homer, ninth century BCE, to the end of the Roman Empire, third century CE. However, not only would one expect attitudes to vary through that very long period (so that there may not be a single ideal to characterize “the Greek society” over such a long period), but, as the authors of the surviving texts were members of the elite, the ideal of landed wealth was not necessarily shared by the entire population.

During the Archaic period 800–500 BC, social status among free male citizens was related to birth within the land-owning aristocracy. Politics was their principal pursuit; participation in political activity conferred a higher status than economic-commercial pursuits. The land-owning aristocrats were the ruling class holding the offices of state. The stage changed in the fifth and fourth centuries with the gradual establishment and deepening of democracy, the enfranchisement of the middle and poorer classes and full access to public office. In Athens, the sons of aristocratic families with political ambitions had to compete for influence in the Assembly of the Demos, where power of argument and rhetorical ability carried the day (see Tridimas 2019 and the literature cited therein). Nevertheless, members of the elite with oligarchic tendencies resisted democracy not only because of the financial burdens it levied on them, but also because democratic decision making by the poor majority denied their superior social status the freedom to conduct policy. During that period individuals of lower birth could also acquire social status by their achievements in the battlefield. Displaying andreia (translated as masculinity), bravery and courage when fighting for the city-state as a hoplite or as a sailor, brought high social esteem. Financial contributions to the polis by rich landowners or successful business people could also bring social status.

6 Performing Liturgies and the Pursuit of Status

Social status and glory are attributes conferred by the society; there are no open markets where status can be directly bought or sold. On the other hand, as already said, there are actions which can be easily observed by the society and when performed confer status. Socrates tells Aristippus: “what about those who labour so that they … do good deeds for their fatherland? Surely one should know that these both labour for such things with pleasure and take delight in living, since they admire themselves and are praised and emulated by others” (Xenophon, Memorabilia 2.1.19) … “if you desire to be honoured by some city, you must benefit the city” (ibid 2.1.28) – emphasis added. Rahe (1984:286) commented: “The polis … provided the citizen with the hope of achieving through his contributions to its welfare at least a shadow of the eternal fame”. Contributions to the welfare of the polis took the form of payment for liturgies, the compulsory private financing of public expenditure, and opened the opportunity for contest for status.

Liturgies were an integral and distinct component of Athenian public finances, where the richest Athenians, about twelve hundreds of them, covered the cost of a number of public services. Each year the appropriate magistrates announced the liturgies to be performed and called for volunteers. If fewer volunteers than the number of liturgies came forward, the magistrates called upon wealthy citizens who had not volunteered. There were about one hundred annual liturgies falling into three broad categories, public festivals, pre-payment of the property tax levied on the rich, and defence. Liturgies for festivals related to payments for public banquets (“hestiasis”) which were the main occasions for consuming meat, torch-race (“gymnasiarchy”), maintaining an embassy to Panhellenic games and festivals (“architheoria”), organising processions carrying the veil of the goddess Athena (“arrephoria”), and training and equipping choirs performing at festivals and theatre plays (“choregia”).Footnote 6 The vast majority of Athenians did not pay direct income or wealth taxes as personal taxation was a sign of servitude.Footnote 7 A property tax was levied only to the richest Athenians. Another liturgy, the ‘proeisphora’, formalised in 378 worked as follows. Those liable to pay the property tax were divided into one hundred groups and the top three or so richest individuals of each group performed the liturgy of paying the tax for the entire group. They would then recover the taxes due from the rest of the members of the group.

The most expensive liturgy was the “trierarchy” (established ca 480) consisting of the command, outfitting, and maintenance of a trireme ship for one year at a cost of one talent (6000 drachmas).Footnote 8 The “trierarch” (person responsible) was chosen between the 300–1200 richest citizens. “To be one of the rich citizens who performed liturgies a man would have to have a property of at least 3 or 4 talents. 1 talent equals what an ordinary Athenian could earn in the course of more than ten years, so that the property of any one of the roughly 1200 liturgists would represent a lifetime’s ordinary earnings” (Hansen 1999:115). Individuals performing liturgies in one year were exempt from the obligation of another liturgy in the following year; trierarchs were normally exempt from other liturgies. Upon successful completion liturgists were awarded golden crowns, while in the case of successful raids the trierachy yielded war booty too.

Liturgists could pay as much as they chose for the liturgy assigned. Those refusing to undertake liturgies faced penalties including fines, loss of property and even loss of citizenship. Since there was no bureaucracy to assess the wealth of citizens, the Athenians operated a system partly based on self-assessment and partly on assessment by others with disputes resolved by the courts. A system of so-called property exchange (“antidosis”) purported to find out whether rich individuals concealed their wealth to avoid liturgies: The nominee for a liturgy could challenge another person, who in his view ought to perform the liturgy, either to pay for the liturgy or to exchange his property with that of the nominee and then the nominee would perform the liturgy. The challenged citizen could then either accept the liturgy or exchange property with the nominee, or demand that the matter would be resolved by a court.Footnote 9 Out of the surviving records for 492 trierarchs, 110 are known to have gone to court. Hansen reports that there is “not a single example of an exchange of property actually taking place” (1999:112).

During the period of democracy, performing a liturgy was considered a duty and an honour for a rich Athenian (Lyttkens, 2013). Citizens competing for social recognition demonstrated their higher social status and wealth by performing liturgies. “Gift-giving [to the polis] … was a major social area in which members of the elite could challenge one another” (Gygax 2016:15). For those harbouring political ambitions, paying for a liturgy simultaneously offered the opportunity to promote their chances for election to public office. Lyttkens (2013:80) brings attention to the signalling role of liturgies, “the most effective way of signalling great wealth was to give things away for free”. Harding (2015:89) calls liturgies “a canny exploitation of the ambition for distinction [philotimia – pride] of the elite members of the society”. Paying for liturgies aligned private incentives for status seeking with the public interest in providing public goods like warships, other services deemed socially desirable like festivals characterised by non-rivalry (up to capacity constraint), and plain private goods like banquets. The expectation of the liturgist to receive honours and social recognition implies a certain element of reciprocity between the liturgist and the citizenry, not unlike the concepts emphasised by the substantivist view of the economy. Gygax (2016) dwells on two aspects of these reciprocal relationships. First, it was not straightforward to calculate the monetary equivalent of a liturgy to what the liturgist received in return. Second, for the liturgist the gift was deferred, since he received the honours at a later, uncertain, time.

However, in so far as those liable to perform liturgies disbursed similar sums but had unequal assets, liturgies were regressive. Given that the cost of liturgies, and especially trierarchies, was substantial, the literary sources indicate that from the end of the fifth century and during the fourth century, wealthy individuals were accused of trying to avoid them by hiding their wealth. After the demise of democracy in 322, the trierarchy was abolished. Remaining festivals were financed through “benefactions”, payments by a single individual who was obliged to make the payment only once in his lifetime and whose contribution was matched by public funds (see Davies 2008, Harding 2015, and Gygax 2016, for details).Footnote 10

7 A Formal Model of Liturgy Spending for Status Seeking

7.1 Taxes, Public Goods and Liturgies

There is a dearth of economic analysis of liturgies. Carmichael (1997) considers a model where rich citizens may engage in costly concealment of their wealth to avoid paying for a liturgy. His simulation results show that when liturgists receive private benefits, like the goodwill of the demos, which compensate them for their expenses, liturgies are an efficient form of paying for public services. Kaiser (2007) offers a game theoretic analysis of liturgies as a mechanism to achieve simultaneously efficient provision of public goods and their voluntary private funding (voluntary in the sense of choosing how much to spend). Her empirical results show that trierarchs paid for the liturgy not only for prestige and power but also because by complying with the regulation they protected their assets and long-run financial interests. The present study adds to this meagre stock by investigating payment for liturgies as a status seeking expense.

The obligation of the rich to perform liturgies was effectively a system of a progressive tax combined with hypothecation of the tax revenue to specific uses with two important characteristics. First, the tax basis was the number of rich individuals rather than the size of their incomes. Redistribution was achieved by obliging only the rich to pay for public services which were then consumed by the poor and rich alike. Second, those liable to tax did not transfer any money to the treasury but financed the assigned public service directly. Not only did they seek the suppliers and organise provision, but they also chose how much to spend, in the quest to win the gratitude of the demos. On the one hand, this mode of provision minimised the transaction costs of the public service as it bypassed both tax collection and public provision by a state agent. The ancient Greeks did not collect statistical information regarding the size of income activity; the cost of calculating the latter in a decentralised economy of agricultural and handicraft production was formidable. Moreover, the intellectual environment of free citizens was most likely hostile to a centralized bureaucracy; even the army was in truth a militia of free citizens. On the other hand, with the system of liturgies rich citizens retained considerable influence over public finances and ultimately power. This made the system a lot more palatable to the rich reducing social tensions, while it also put in public use the competitive instincts of the elite. Liturgies were therefore in line with the tenets of the New Institutional Economics. That is, in response to ubiquitous uncertainty, actors set up formal and informal institutions to decrease the cost of uncertainty by regulating conflict and governing exchanges. Lyttkens (2103:110) sees “the formalisation of the liturgical system … as the creation of a market for honour, with the government selling positions of honour to increase revenue”. Further, “there was clearly an honorific element involved: people sometimes paid out more than they had on their liturgies, as lavish spending could be useful both politically and in front of the popular courts” (ibid: 111).

7.2 Individual and Collective Liturgy Payments

Formally, we assume a society with two classes of citizens, the poor majority, indexed by \(p\) and the rich elite further divided into two players 1 and 2 who are liable to pay for liturgies. The model takes the number of rich taxpayers as decided in a previous stage and therefore exogenous; we leave the question of how the number of taxpayers liable was chosen for future research. Let \({C}_{h}\),\({L}_{h}\) and \(G\) denote respectively private consumption, leisure, and a public good collectively consumed by the society, and let \({W}_{h}\) denote the labour productivity of \(h=p,\mathrm{1,2},\) where \({W}_{1}>{W}_{p}\) and \({W}_{2}>{W}_{p}\). We approximate the system of private finance of the public goods by liturgies as follows.Footnote 11 There are no income taxes in the economy, but the poor force the two rich individuals to pay for the public good\(G\). The two rich individuals then chose to provide the quantities \({G}_{1}\) and\({G}_{2}\), so that the poor consume a total quantity of the public good \({G}_{S}={ G}_{1}+{ G}_{2}\). It is assumed that each rich individual fully accepts the obligation to pay for the liturgy, so questions of free riding and incentive compatibility do not arise. We further assume that each liturgist provides the same quality of the public good and pays the same price—unit cost for the quantity of the public goods provided, but is free to choose different quantities.

As per standard treatment it is posited that individuals have identical utility functions. Assuming Cobb–Douglas utility function,Footnote 12 the representative poor chooses \({C}_{p}\) and \({L}_{p}\) to maximise

The latter is subject to the budget constraint, where \(Y\) denotes income

That is, income is spent entirely on consumption. Solving the above, we obtain the equilibrium expressions

The utility of each rich person is assumed to depend positively on the total size of the public good, but vying for social status the marginal utility from own provision exceeds that of the provision by the other person. That is,\({G}_{2}\) confers to individual 1 less utility than \({G}_{1}\), and vice versa, by a proportion \(\gamma\) with \(0\le \gamma \le 1\).Footnote 13 This modelling of status follows the formulation of envy or rivalry used in the literature where the individual compares his spending to the rest of the society (see Frank 1985; Solnick and Hemenway 1998; Layard 2005).

The utility of \(i=\mathrm{1,2}; i\ne j\) is then written as

In the above expression the \(\gamma\) parameter shows how much individual \(i\) cares for his relative status; a larger \(\gamma\) indicates that \(i\) is more concerned with his status and derives less utility from the contribution of \(j\) to the public good. The externality is absent in the extreme case of \(\gamma =0\). In the opposite extreme of \(\gamma =1\) envy is at its highest so that the provision by individual 2 does not confer utility to 1 and vice versa. With \(P\) denoting the relative unit price of the public good relative to the private consumption, the budget constraint of \(i=\mathrm{1,2}\) is

Substituting into (4) into (1.A) and maximising with respect to \({L}_{i}\) and \({G}_{i}\) yields the reaction functions of \(1\) and \(2\) (not shown). Upon solving the latter we obtain the Nash equilibrium solutions for leisure, private consumption, income, and liturgy provision of each \(i=\mathrm{1,2};i\ne j\)

For an interior solution of (5.1) it must be \({0<L}_{iS}, { L}_{jS}<1\). With \(1-\left(1-\beta \right){\left(1-\gamma \right)}^{2}>0\) we are guaranteed that \({L}_{iS}>0\) and\({L}_{jS}>0\). For \({L}_{iS}<1\) and \({L}_{jS}<1\) the conditions \(\frac{\beta \left(1-\alpha -\beta \right)\left(1-\gamma \right)}{\alpha \left(1-{\left(1-\beta \right)\left(1-\gamma \right)}^{2}\right)+\beta }<\frac{{W}_{j}}{{W}_{i}}\) and \(\frac{\beta \left(1-\alpha -\beta \right)\left(1-\gamma \right)}{\alpha \left(1-{\left(1-\beta \right)\left(1-\gamma \right)}^{2}\right)+\beta }<\frac{{W}_{j}}{{W}_{i}}\) must hold simultaneously. Since \(\frac{\beta \left(1-\alpha -\beta \right)\left(1-\gamma \right)}{\alpha \left(1-{\left(1-\beta \right)\left(1-\gamma \right)}^{2}\right)+\beta }<1\) the two inequalities are consistent with each other for a large range of parameter values; we assume that the parameters are such that the conditions hold. With \({0<L}_{iS}, { L}_{jS}<1\) we are also guaranteed that \({Y}_{iS}>0\) and \({Y}_{jS}>0\). Next, for \({Y}_{iS}>{Y}_{P} , i=1, 2,\) that is, the income of each one of the highly productive individuals exceeds the income of the poor individual, it must be \(\frac{\left(\alpha +\beta -\alpha \left(1-\beta \right){\left(1-\gamma \right)}^{2}\right){W}_{i}-\beta \left(1-\alpha -\beta \right)\left(1-\gamma \right){W}_{j}}{1-{\left(1-\beta \right)}^{2}{\left(1-\gamma \right)}^{2}}\frac{1-\beta }{\alpha }>{W}_{P}; i\ne j\) for \(i=1, 2\). Again, we assume that the parameters are such that the inequalities hold. Further, regarding the incomes of the two most productive individuals using (5.2) and manipulating we obtain that \({Y}_{iS}-{Y}_{jS}=\frac{-\alpha \left(1-\beta \right)}{1-{{\left(1-\beta \right)}^{2}\left(1-\gamma \right)}^{2}}\left(1-\gamma +\frac{1}{1-\beta }\right)\left(1-\gamma -\frac{\alpha +\beta }{\alpha }\right)\left({{W}_{i}-W}_{j}\right)>0\)(since\(0\le \gamma \le 1\)), which yields \({Y}_{iS}>{Y}_{jS}\) for\({{W}_{i}>W}_{j}\). That is, the highest productivity individual is also the individual with the highest income.

Turning to the sizes of the liturgies, from (5.4) we have that for both \({G}_{iS}\) and \({G}_{jS}\) to be positive it must be simultaneously

Since \(1>\left(1-\beta \right)\left(1-\gamma \right)\) the two inequalities are consistent with each other for a large range of parameter values; we assume that the parameters are such that the conditions in (5.5) hold, so that \({G}_{iS}>0\) and \({G}_{jS}>0\).

Next, taking the difference between \({G}_{1S}\) and \({G}_{2S}\), we have

That is, among the rich, the most productive individual makes a larger contribution to public provision than the less productive individual. Regarding the effect of status seeking on individual provision upon differentiating (5.4) we derive \(\frac{\mathrm{d}{G}_{iS}}{\mathrm{d}\gamma }=\frac{\beta \left(1-\beta \right)}{{\left(1-{\left(1-\beta \right)}^{2}{\left(1-\gamma \right)}^{2}\right)}^{2}P}\left[\left(1+{\left(1-\beta \right)}^{2}{\left(1-\gamma \right)}^{2}\right){W}_{j}-2\left(1-\beta \right)\left(1-\gamma \right){W}_{i}\right]\) which yields

If \({W}_{j}> {W}_{i}\) and noting that \(\frac{1+{\left(1-\beta \right)}^{2}{\left(1-\gamma \right)}^{2}}{2\left(1-\beta \right)\left(1-\gamma \right)}>1\), the liturgy payment of the less wealthy individual \(i\) increases with the size of the status parameter \(\gamma\). However, the response of the more productive individual to a change in \(\gamma\) is ambiguous.

Further, upon dividing (5.4) by (5.2), we identify the ratio of liturgy payment to income, that is, the implicit personal tax rate levied on \(i\) by the obligation to provide a liturgy.

The latter shows that the implicit tax rate depends on the difference of the earning abilities of the taxpayers. With \({Y}_{iS}>\) and \({G}_{iS}>0\) we are assured that \({t}_{iS}>0\) for \(i=\mathrm{1,2}\).

Turning to the aggregate performance of the economy, we obtain that the sums of consumption and income of the rich and total size of the public good provided to the poor are respectively

Examining the responses of \({Y}_{S },{ C}_{S}\) and \({G}_{S}\) to the status parameter \(\gamma\) we have

The above establish unequivocally that as a result of status seeking the rich collectively generate a higher income (7.1), consume less (7.2) and provide more public goods (7.3) than without status seeking. Most importantly for the welfare of the poor, under liturgies, when the paying rich compete against each other for status, the resulting size of public provision available is larger than in the absence of status seeking.Footnote 14 This finding confirms Congleton’s result obtained in a different setting that contests for status bring positive external effects for those not taking part in the contest. It also follows that when the opportunities to gain prestige and reputation by private outlays for public services decline (as the sources allude for the fourth century), the size of liturgies declines too. Finally, in accordance to intuition, (7.3) shows that the size of provision increases as the economy becomes richer (\({W}_{1}\) and/or \({W}_{2}\) rise), but falls as the public good becomes more expensive to produce (\(P\) rises).

7.3 Comparison between Liturgies and Tax Financed Public Expenditures

If public expenditures are covered by an income tax on the rich at a proportional rate of \(t\) and the unit cost of public provision remains equal to that paid by liturgists, upon denoting the resulting size of public provision by \({G}_{T}\), the government budget constraint is

In this setting, the budget constraint of \(i=\mathrm{1,2}\) is written as \({Y}_{i}={\left(1-t\right)W}_{i}\left(1-{L}_{i}\right)={ C}_{i}\). The rich then choose \({L}_{i}\) to maximise\({U}_{i}= aln{\left(1-t\right)W}_{i}\left(1-{L}_{i}\right) +\beta ln{G}_{T}+\left(1-\alpha -\beta \right)ln{L}_{i}\). The latter yields the equilibrium solutions \({L}_{i}=\frac{1-\alpha -\beta }{1-\beta }{, Y}_{i}=\frac{\alpha }{1-\beta }{W}_{i}\) and \({C}_{i}=\frac{\alpha \left(1-t\right)}{1-\beta }{W}_{i}\). The indirect utility of \(i\) is then written as

Assuming as per standard practice that the tax rate is chosen by maximising the sum of the utilities of the two taxpayers \({U}_{1}+{ U}_{2}\) and solving, we derive the optimal tax rate as

The corresponding individual equilibrium levels of consumption and income of the rich are

At this level of generality we cannot identify unambiguously whether individual consumption and income are greater or smaller under the liturgy system or income taxation. We can however compare their sums under the two different systems. The sums of consumption and income of the rich, and of public provision are

Note that in the present setting of no taxes for the poor and a Cobb–Douglas utility function, the equilibrium levels of consumption and leisure of the poor remain the same regardless of the fiscal regimes of liturgies or explicit taxation of the rich; only the level of public services differs. Whether or not the poor are better off with liturgies or explicit taxes on the incomes of the rich, depends on the difference between \({G}_{S}\) and \({G}_{T}\). From (6.3) and (11.3) we have

The latter implies.

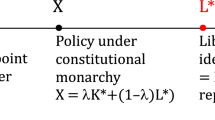

That is, at the present level of generality it is ambiguous which of the two systems of finance brings the largest level of public goods. The threshold value of the status competition parameter \({\gamma }^{*}\) is positive for values such that\(\alpha >\beta \left(1-\beta \right)\), a condition which is assumed to hold. From (12.1) we also have that the difference is increasing in \(\gamma\) since\(\frac{d\Delta G}{d\gamma }=\frac{d{G}_{S}}{d\gamma }>0\); that is, the greater the quest for status the larger the difference between liturgy and income tax provision. Figure 1 graphs the relationship between \(\Delta G\) and\(\gamma\), and indicates the extreme values of\(\Delta G\), (those for \(\gamma =0\), and\(\gamma =1\)). From inequality (12.2) we have that for values of the status externality parameter greater than the \({\gamma }^{*}\) threshold the system of liturgy finance secures a higher size of public goods than an income tax paid by the rich. We may call a setting with high\(\gamma\), meaning\(\gamma >{\gamma }^{*}\), an “agonistic” one, that is, one of intense status competition between the rich. Accordingly, in such an environment the poor majority is better off under liturgies rather than income taxation of the rich (and vice versa). The qualitative properties of \({\gamma }^{*}\) are discussed in the Appendix.

For completion we also examine the effects of paying for liturgies and paying income taxes on the size of income, tax burden and consumption of the rich individuals. Comparing first the sum of incomes of the rich under the two different fiscal regimes and upon taking the difference between (6.1) and (10.1), we have

That is, the sum of the incomes of the rich is higher when in the pursuit for status they are taxed implicitly through liturgies.

Further, comparing the implicit and explicit tax rates in (5.5) and (10.1) we have

Inequality (12.4) demonstrates the different tax burdens that the liturgies impose on the different members of the group of the rich. However, nothing in the inequality precludes that \({t}_{i}> {t}_{T}\) for both \(i=\mathrm{1,2}\), that is, all members of the rich group pay higher implicit taxes through liturgies. In turn, this may explain why during the fourth century liturgies were resisted by rich Athenians with different levels of wealth.

Finally, comparing the sum of consumption under payment of liturgies and payment of income taxes, (6.2) and (11.2) respectively, we have

The sign of (12.5) is unequivocally positive because \(\frac{-\beta }{1-\beta }<0<\gamma <1<1+\frac{1-\alpha -\beta }{1-\beta }\). Thus, under the liturgy system and with the liturgists competing for status, the sum of the consumption expenditures of the rich is higher than under income taxation. This result echoes that of the standard model of status seeking where the individual compares its private consumption spending pattern to the rest of the society and public goods are absent (see e.g., Frank 1985; Layard 2005).

8 Conclusions

Status considerations mean that the individual is concerned with his relative position in the social ladder. The present study investigated aspects of the quest for status in ancient Greece. Specifically, it examined a setting where rich individuals sought to establish superior social status by performing liturgies, obligatory payments for public services which were jointly consumed by the rich and the poor, but expenditure was chosen by the spender. Like several unique institutions prevalent in ancient Greece, the liturgy mode of financing public services differed significantly from a system of income taxes. Recognising that public goods benefit all consumers, the novelty of the study has been to model the quest for status as a negative externality, in the sense that a liturgist derives higher benefit from his expense for public services relative to the expense of his peers. It was found that this type of status seeking increases aggregate provision of public goods. This implies that the ancient Greeks exploited human traits for the benefit of the community. The study then proceeded to compare the implicit tax implied by paying for liturgies with a hypothetical explicit tax on the income of the liturgist, other things being equal. It was concluded that although the size of public provision was increasing in the intensity of status seeking externality, it was not clear whether public provision under liturgies is greater or lower than under explicit income taxation. The more general point of the investigation is that it illustrates the value of using economic modelling to develop a more accurate picture of the ancient Greek economy. Contrary to the substantivist view of the ancient Greek economy, economic modelling offers insights into the behaviour of ancient agents which otherwise would have gone amiss. More broadly, financing of liturgies in ancient Greece offers an excellent illustration of how status seeking interacts with both politics and economics.

Notes

“The ancients … lacked the concept of an ‘economy’, and a fortiori, they lacked the conceptual elements which together constitute what we call the ‘economy’” (Finley 1979:21).

For example, Christesen (2003) discusses the suitability of the concepts of instrumental, procedural and expressive rationality to ancient Greece; he argues that expressive rationality, according to which individuals strive to maximize profits and espouse social norms, is a better descriptor of economic decision-making in Classical Athens. Foxhall (2007) argues that wealthy households sought opportunities to maximize domestic production while poor households were more like subsistence farmers. Schefold (2011) maintains that the Athenian economy was neither capitalist nor devoid of capitalistic elements and contends that the modern neoclassical economic theory is at best of limited applicability to ancient Greece. Lewis (2018), without fully abandoning Finley’s approach, supports the application of the methodology of New Institutional Economics (NIE) and its emphasis on Transaction Costs and bounded rationality to study the workings of the ancient Greek economy. Stanley (2019) reviews the applicability of the polar distinction between embedded and disembedded to the Athenian economy, and concludes that from the sixth century onwards the Athenian economy most likely combined elements of both.

Contrary to Finlay, de Ste. Croix held that Marxist concepts best represent social differences in ancient Greece. For critical discussions of the debate between Finley and de Ste. Croix and refinement by later authors see Nafissi (2004) and Kamen (2013). This debate regarding class conflict in ancient Greece is beyond the scope of the present inquiry.

Kamen (2013) argues that the boundaries between these groups were less fixed and more permeable than the Athenians themselves acknowledged, and that a fruitful approach is one which recognises a spectrum of statuses in classical Athens; namely, chattel slaves, privileged chattel slaves, conditionally freed slaves, metics, privileged metics, bastards, disenfranchised citizens, naturalized citizens, female citizens, and male citizens. For a recent discussion of the Athenian social structure see also Pritchard (2020).

One could neither choose the gender at birth nor the group of birth (citizen, metic or slave). Several individuals must have deliberately decided to emigrate from their birthplaces to Athens and become metics for economic reasons, but they knew that they would have fewer rights than citizens. It was also possible for slaves to be manumitted elevating to metic status and for metics (including ex-slaves) to be granted full citizenship.

See Davies (1967) for a detailed description of civilian liturgies which were parts of festival celebrations in Athens and outside Athens. Such festivals could cost between 300 and 3000 drachmas. Contrary to the other liturgies, festival liturgies could also be levied on metics.

A 5% tax on produce was levied during the tyranny of Peisistratus and his heirs, 546–510, but it was abolished after the foundation of democracy.

Gabrielsen (1994) offers a detailed analysis of the finances of the Athenian navy.

The antidosis procedure bears a certain similarity to the “Harberger tax” proposed by Posner and Weyl (2017) in response to the following private ownership dilemma. Private ownership of resources gives the owner monopoly power over an asset, but as is well known, monopoly reduces allocative efficiency; on the other hand, private ownership generates superior incentives for investment and therefore increases efficiency. Posner and Weyl claim that a mixed version of private and common ownership, which they call “partial common ownership”, optimizes across allocative and investment efficiency and argue for a self-assessed property taxation, or “Harberger tax” which would fulfill this function. Under the Harberger tax, “people periodically report valuations of their property to a government registry; pay property taxes based on these valuations; and are required to sell their property at these valuations to any buyer” (2017:54). We leave the implications of the antidosis system for the definition and protection of private property rights in ancient Greece for future research.

In addition to liturgies, a number of scholars saw trials in Athens as contests for status (Ober 1989; Cohen 1995; Lanni 2009; Lyttkens 2013). In addressing the courts, litigants spent considerable time highlighting their characters, public reputations and contributions to public service while simultaneously accusing their opponents of lack of such attributes and donations. Such arguments were offered because they must have appealed to the mass of jurors, who shared the same values regarding envy, honour and hybris. Cohen (op.cit) contends that in this light Athenian litigation is best understood as feud and the process of judicial judgment as operating within an agonistic social field; Herman (2006) however, challenges this view. We leave the examination of court trials as status contests for future research.

What follows is a highly simplified fiscal system. The Athenians operated a complex system of public finances, where in addition to property taxes levied on wealthy individuals and lump-sum taxes on non-Athenians, revenue was raised from the royalties from the silver mines and trade taxes. See Kyriazis (2009) for a detailed account of Athenian public finances in the fourth century.

The Cobb–Douglas specification implies that the sizes of leisure and consumption of the poor are independent of the fiscal variables; the latter affect only the size of public provision.

Were the poor to also pay for the public service, again the status seeking rich would have valued their contributions at \(1-\gamma\).

At the extreme, had each individual been unconcerned about how much the other contributed, that is, \(\gamma =0\) the size of public provision would have been \({G}_{S}^{0}=\frac{\beta \left({W}_{1}+{W}_{2}\right)}{\left(1+\left(1-\beta \right)\right)P}<{ G}_{S}\).

Abbreviations

- D62:

-

Externalities

- H23:

-

Redistributive effects

- H41:

-

Public goods

- N34:

-

Economic history-welfare, income, wealth

References

Amemiya, T. (2007). Economy and economics of ancient Greece. London: Routledge.

Austin, M. M., & Vidal-Naquet, P. (1977). Economic and social history of ancient greece. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Bowles, S. (1998). Endogenous preferences: The Cultural consequences of markets and other economic institutions’. Journal of Economic Literature, 36, 75–111.

Bresson, A. (2016). The making of the ancient Greek economy. Institutions, markets and growth in the city–states, translated by S. Rendall. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Burke, E. (1992). The economy of Athens in the Classical Era: Some adjustments to the primitivist model. Transactions of the American Philological Association, 122, 199–226.

Carmichael, C. M. (1997). Public munificence for public benefit: Liturgies in classical Athens. Economic Inquiry, 35, 261–270.

Carugati, F., Ober, J., & Weingast, B. R. (2019). Is Development uniquely modern? Ancient athens on the doorstep. Public Choice, 181, 29–47.

Charness, G., Masclet, D., & Villeval, M. C. (2013). The dark side of competition for status. Management Science, 60, 38–55.

Chaudhry, A., & Garner, P. (2013). The political economy of income comparisons and economic growth. Economic Modelling, 31, 214–222.

Christesen, P. (2003). Economic rationalism in fourth-century BCE athens. Greece & Rome, 50, 31–56.

Clark, A. E., Frijters, P., & Shields, M. A. (2008). Relative income, happiness, and utility: An explanation for the easterlin paradox and other puzzles. Journal of Economic Literature, 46, 95–144.

Cohen, D. (1995). Law, violence and community in classical athens. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cohen, E. (1992). Athenian economy and society. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Congleton, R. D. (1989). Efficient status seeking: Externalities and the evolution of status games. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 11, 175–190.

Davies, J. K. (1967). Demosthenes on liturgies: A Note. The Journal of Hellenic Studies, 87, 33–40.

Davies, J.K. (2008). Cultural, social and economic features of the Hellenistic World. Classical Greece: Production. In: Walbank, F.W, Astin, A.E., Frederiksen, M.W., Ogilve, R.M. (Eds.) Cambridge Ancient History, Vol. VII, Part I, The Hellenistic World: Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2nd edition (pp. 257–320).

Duesenberry, J. (1949). Income, saving, and the theory of consumer behavior. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Easterlin, R. A. (1974). Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence. In P. A. David & M. W. Reder (Eds.), Nations and households in economic growth: Essays in honour of moses abramowitz (pp. 89–125). New York and London: Academic Press.

Engen, D.T. (2010). Honor and Profit: Athenian Trade Policy and the Economy and Society of Greece, 415–307 B.C.E. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Finley, M. I. (1979). The ancient economy. London: Book Club Associates with Chatto and Windus.

Foxhall, L. (2007). Olive cultivation in ancient Greece: Seeking the ancient economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Frank, R. H. (1985). The demand for unobservable and other nonpositional goods. American Economic Review, 75, 101–116.

Frank, R. H., & Heffetz, O. (2011). Preferences for status: Evidence and economic implications, in J. Benhabib, J., Bisin, A. & Jackson, M. (Eds.), Handbook of social economics (pp. 69–91), Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Frey, B. & Stutzer, A. (2005). Testing theories of happiness. In: Bruni, L. & Porta, P.L (Eds.), Economics and Happiness: Framing the Analysis (pp. 117–146). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gabrielsen, V. (1994). Financing the athenian fleet: Public taxation and social relations. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Gershman, B. (2014). The two sides of envy. Journal of Economic Growth, 19, 407–438.

Gygax, M. D. (2016). Benefactions and rewards in the ancient Greek city. The origins of euergetism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hansen, M. H. (1999). The Athenian democracy in the age of Demosthenes. Structure, principles and ideology. London: Bristol Classical Press.

Harding, P. E. (2015). Athens transformed. From population sovereignty to the dominion of wealth. Abingdon: Routledge.

Hargreaves Heap, S. P. (2013). What is the meaning of behavioural economics? Cambridge Journal of Economics., 37, 985–1000.

Harris, E.M. (2002). ‘Workshop, marketplace and household: the nature of specialization in classicl Athens and its influence on economy and society’, in Cartledge, P., E.E. Cohen, E.E. & Foxhall, L. (Eds.) Money, labour and land. Approaches to the economies of ancient Greece (pp. 67–99). Abingdon: Routledge

Harris, E. M., & Lewis, D. M. (2015). Introduction: Markets in classical and hellenistic Greece. In E. M. Harris, D. M. Lewis, & M. Woolmer (Eds.), Markets, households and city-states in the ancient Greek economy (pp. 1–40). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hirsch, F. (1976). Social limits to economic growth. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Humphreys, S. C. (1970). Economy and society in classical athens. Annali della Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa, 39, 1–26.

Jaikumar, S., Singh, R., & Sarin, A. (2018). ‘I show off, so I am well off’: Subjective economic well-being and conspicuous consumption in an emerging economy. Journal of Business Research, 86, 386–393.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47, 263–291.

Kaiser, B. A. (2007). The athenian trierarchy: Mechanism design for the private provision of public goods. The Journal of Economic History, 67, 445–480.

Kamen, D. (2013). Status in classical athens. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Kyriazis, N. K. (2009). Financing the Athenian state: Public choice in the age of Demosthenes. European Journal of Law and Economics, 27, 109–127.

Lanni, A. (2009). Social norms in the courts of ancient Athens. Journal of Legal Studies, 1, 691–735.

Layard, R. (2005). Rethinking Public Economics: The Implications of rivalry and habit in Economics, In: Bruni, L. & Porta, P.L (Eds.), Economics and Happiness: Framing the Analysis (pp 147–169). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lewis, D. (2018). Behavioral economics and economic behavior in Classical Athens. In M. Canevaro, A. Erskine, B. Grey, & J. Ober (Eds.), Ancient greek history and contemporary social sciences (pp. 15–46). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Lyttkens, C. H. (2013). Economic analysis of institutional change in Ancient Greece: Politics, taxation and rational behaviour. Abingdon: Routledge.

Millet, P. (2000). The economy. In Osborne, R. (Ed), Classical Greece, (pp. 23–51) Oxford: Oxford University Press

Millett, P. C. (1991). Lending and borrowing in ancient athens. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Morris, I. (2004). Economic growth in ancient Greece. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics, 160, 709–742.

Nafissi, M. (2004). Class, embeddedness, and the modernity of ancient athens. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 46, 378–410.

North, D. C., Wallis, J. J., & Weingast, B. R. (2009). Violence and social orders. A conceptual framework for interpreting recorded human history. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ober, J. (1989). Mass and Elite in Democratic Athens Princeton: Princeton University Press

Ober, J. (2015). The rise and fall of classical Greece. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Pham, T. K. C. (2005). Economic growth and status-seeking through personal wealth. European Journal of Political Economy, 21, 407–427.

Pollak, R. A. (1976). Interdependent preferences. American Economic Review, 66, 309–320.

Posner, E. A., & Weyl, E. G. (2017). Property is another name for monopoly. Journal of Legal Analysis, 9, 51–123.

Postlewaite, A. (2011). Social Norms and Preferences. In J. Benhabib, A. Bisin, & M. Jackson (Eds.), Handbook of social economics (pp. 32–67). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Pritchard, D.M. (2020). The social structure of democratic Athens. In de Oliveira Silva, M.A. and C. D. de Souza, C.D. (Eds.) Morte e Vida na Grécia Antiga: Olhares interdisciplinares, Teresina Editora da UFPI (in press). Available from https://www.academia.edu/43235678. Accessed 13 June 2020.

Rahe, P. A. (1984). The primacy of politics in classical greece. American Historical Review, 89, 265–293.

Sallares, P. (1991). The ecology of the ancient Greek world. London: Duckworth.

Schefold, B. (2011). The applicability of modern economics to forms of capitalism in antiquity. Some theoretical considerations and textual evidence. Journal of Economic Asymmetries, 8, 131–163.

Scheidel, W. (2010). Real wages in early economies: Evidence for Living Standards from 1800 BCE to 1300 CE. Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 53, 425–462.

Solnick, S. J., & Hemenway, D. (1998). Is more always better?: A survey on positional concerns. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 37, 1373–1383.

Stanley, P.V. (2019). Was the ancient Athenian Economy embedded and / or disembedded? available from https://www.academia.edu/39754922. Accessed 04 Aug 2019

Tridimas, G. (2019). Democracy without political parties: the case of ancient Athens. Journal of Institutional Economics, 15, 983–998.

Veblen, T. (1899). The Theory of the Leisure Class. Reprint 1965, NY: MacMillan

Weiss, Y., & Fershtam, C. (1998). Social status and economic performance: A survey. Europsean Economic Review, 42, 801–820.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Peter Nannestad and Roger Congleton for their suggestions on an earlier version of this research. I owe special thanks to Hartmut Kliemt for his guidance and encouragement in writing this paper. I am also grateful to two anonymous referees for insightful comments on an earlier draft. I am, of course, responsible for any remaining errors and omissions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

I confirm that in preparing this manuscript there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

“The best men choose one thing above all, the everlasting fame of mortals; the many gorge themselves like cattle” Heraclitus ca 500 BC https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/heraclitus/

Appendix

Appendix

The determinant of the threshold \({\gamma }^{*}= \frac{1}{1-\beta }-\frac{\beta }{\alpha }\)

Inequality (12.2) of the text implies that, given the value of \(\gamma\), the lower the level of the threshold \({\gamma }^{*}\) the more likely that the liturgy system yields a higher level of public goods, and vice versa.

Note first that with \(1-\alpha -\beta >0\) it is always \({\gamma }^{*}<1 .\)

Next, since \(\frac{d{\gamma }^{*}}{d\alpha }=\frac{\beta }{{a}^{2}}>0\), the smaller the value of \(\alpha\), the smaller the corresponding threshold \({\gamma }^{*}\); hence, other things being equal, the more likely that \({G}_{S}> {G}_{T}\). Intuitively, a society whose rich compete for status through payment for liturgies and which values private consumption only modestly (low \(\alpha\)) is more likely to choose liturgies. This may be true of the Athenian society during the fifth century rather than the fourth (since the sources indicate that the rich complained against liturgy payments during the latter).

However, the relationship between \({\gamma }^{*}\) and \(\beta\) is not monotonic. Specifically, \(\frac{d{\gamma }^{*}}{d\beta }=\frac{\alpha -{\left(1-\beta \right)}^{2}}{\alpha {\left(1-\beta \right)}^{2}}>\left(=, <\right) 0\) for \(\beta >\left(=, <\right)1-\sqrt{\alpha }\) and \(\frac{{d}^{2}{\gamma }^{*}}{d{\beta }^{2}}=\frac{2}{{\left(1-\beta \right)}^{3}}>0\). As \(\beta\) increases \({\gamma }^{*}\) first declines, but after reaching a minimum equal to \({\gamma }^{*}=\frac{2}{\sqrt{\alpha }}- \frac{1}{\alpha }\) it rises. Figure 2 graphs \({\gamma }^{*}\) against \(\beta\) for different values of \(\alpha\)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tridimas, G. Modelling the Quest for Status in Ancient Greece: Paying for Liturgies. Homo Oecon 37, 213–236 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41412-020-00100-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41412-020-00100-1