Abstract

Remote delivery of interventions (e.g., online sessions, telephone sessions, e-mails, SMS, applications) facilitate access to health care and might be an efficacious alternative to face to face treatments for bulimia nervosa (BN) and binge-eating disorder (BED). Telehealth has evolved rapidly in recent years, facilitating access to health care, as it seems to be more accessible among different groups of the population. In the light of the COVID-19 pandemic, we decided to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compared remote versus face-to-face interventions for the treatment of BN and BED. We searched EMBASE, PubMed, CENTRAL, ClinicalTrials.gov, and WHO ICTRP and reference lists of relevant articles up to April, 2023. The primary outcomes were remission (defined as abstinence from binge/bulimic episodes for at least 2 weeks) and frequency of binge episodes. We also analyzed frequency of purging episodes, response, mean values of eating disorder psychopathology, depression, anxiety, and quality of life rating scales as well as drop-out rates and adverse effects. Six RCTs were identified with a total of 698 participants. Face-to-face interventions were found more effective than remote interventions in terms of remission (RR = 0.69, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.89, P = 0.004, 4 RCTs, N = 526), but the result was mainly driven by one study. No important differences were found in the remaining outcomes; nevertheless, most comparisons were underpowered. Few adverse effects were reported. Remote interventions demonstrated comparable efficacy to face-to-face interventions in treating BN and BED, providing effective and acceptable healthcare to patients who would otherwise go untreated. Nonetheless, to arrive at more definitive and secure conclusions, it is imperative that additional randomized controlled trials and robust real-world effectiveness studies, preferably with appropriate comparison groups, are conducted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Bulimia Nervosa (BN) and Binge-Eating Disorder (BED) are two common eating disorders, closely related (Fichter et al., 2008). BN includes recurrent binge episodes characterized by lack of control during the consumption of a large amount of food and subsequent attempts to compensate for the food consumed (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). BED presents with repeated and unrestrained binge episodes, but these are not accompanied by compensatory behaviors to avoid weight gain (Moghimi et al., 2022). Both types of eating disorders have been associated with a lower quality of life, functional impairment, as well as high emotional distress (Brownley et al., 2016; Jenkins et al., 2011; Kessler et al., 2013; Stice et al., 2013). Evidence-based treatment for patients with Binge spectrum disorders is available (Argyrou et al., 2023; Fornaro et al., 2023), but it remains markedly underutilized (Cooper & Kelland, 2015; Kazdin et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2022). Telehealth might be an efficacious alternative for treatment delivery as it facilitates access to healthcare (Jacobs et al., 2019). More specifically, it could be used to overcome problems such as mobility difficulties, lack of transportation, lack of time due to work or other commitments, limited professional resources at a local level, inequalities in accessing care (Malik et al., 2023), as well as the stigma that still accompanies mental health issues (Hoge et al., 2004), and it has been extensively used during in recent years (Termorshuizen et al., 2020). On the other hand, socioeconomic inequalities in healthcare access can hinder the optimal utilization of telehealth, given that not all individuals possess the requisite internet connectivity or computing devices.

All in all, an up-to-date compilation of the literature regarding remotely-delivered interventions for mental health disorders is crucial. This need arises primarily due to the dynamic evolution of the telepsychiatry field, coupled with the increasing reliance on remote delivery methods in response to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Recent meta-analyses conducted on other mental disorders such as depression (Moshe et al., 2021) and obsessive–compulsive disorder (Salazar de Pablo et al., 2023) have found no significant difference in efficacy between remote and face-to-face interventions. In the field of eating disorders, several types of remote interventions are used, such as videoconferencing and tele-conferencing. Some optimistic results from studies that examined self-help treatments on the internet have been reported (Carrard et al., 2011). However, despite the worldwide application of remote interventions in the treatment of BN and BED, the findings from various studies seem to be contradictory. Many studies support that remote and face-to-face interventions share similar efficacy (Ljotsson et al., 2007; Mitchell et al., 2008), while others fail to verify these findings (De Zwaan et al., 2017; Yu et al., 2020; Zerwas et al., 2017).

The current meta-analysis is the first to provide a comprehensive evaluation of the efficacy and acceptability of remotely-delivered interventions versus face-to-face ones for Binge spectrum disorders in terms of several important outcomes such as remission, frequency of binges and purge, response to treatment, and dropouts.

Materials and Methods

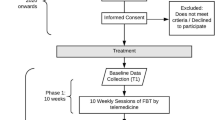

An a priori written study protocol was published in PROSPERO [number: CRD42021230478] and is presented in Supplement A. The systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted in compliance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Supplement B) (Moher et al., 2009).

Participants and Interventions

Our analysis included all randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that examined remote versus face-to-face delivery of equivalent interventions for the treatment of BN and/or BED. The active involvement of a therapist during the course of the intervention was an essential inclusion criterion for all remote interventions. There was no restriction concerning age, gender, and comorbidities. Any type of intervention that was provided via telemedicine (e.g., online sessions, telephone sessions, e-mails, SMS, applications) or face-to-face was included.

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

We identified RCTs in patients with BN or BED through a comprehensive, systematic literature search in EMBASE, PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), ClinicalTrials.gov, and WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP), covering the period from inception of databases up to April 2023. The search comprised terms related to trials, BN and BED. Moreover, we inspected the reference lists of the included studies and previous reviews on the same topic. There were no restrictions on the language, date, and publication status of the studies. Screening of titles and abstracts, and study selection was conducted by at least two independent reviewers (MS, EM, NM). In addition, we sent emails to the first and corresponding authors of all included studies to ask for missing data.

Outcome Measures and Data Extraction

The primary outcomes were (a) remission defined as 100% reduction in bulimia/binge eating-related symptoms over a minimum of a 2-week period or as no longer meeting the relevant diagnostic criteria including cognitive elements (Williams et al., 2012), and (b) frequency of binges. Secondary outcomes were frequency of purges; response defined as a reduction of at least 50% in bulimic/binge-eating episodes or according to authors' definitions (Argyrou et al., 2023; Williams et al., 2012); eating disorder psychopathology measured by Eating Disorder Inventory (EDI) or any other validated scale; depressive and anxiety symptoms; weight; body mass index (BMI); quality of life (QoL); total dropouts; dropouts due to adverse effects; and the total number of patients with adverse effects. We used the Cochrane risk of bias tool (study based) for randomized trials (RoB) to assess bias in included studies.

When authors of original studies used imputation methods to handle missing data, these were preferred over completers’ data. In crossover trials, we used the first crossover phase to avoid the problem of carryover effects if possible. Two independent reviewers (EM, NM) extracted all data from all included studies. Any disagreement was resolved by a third reviewer (MS). Missing SDs were estimated from P values or other information, or they were substituted by the mean SD of the other included studies.

Statistical Analysis

We performed a pairwise meta-analysis with Review Manager 5.4. We employed a random-effects model for analysis. Endpoint values were preferred to change whenever possible since the calculation of change needs two assessments (baseline and endpoint) which can be difficult. All analyses were on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis whenever possible. The effect size for dichotomous outcomes was Risk Ratio (RR). The effect size for continuous outcomes was weighted mean difference (MD); if different units of measurements were used, the effect size was calculated as Hedge's adjusted g standardized mean difference (SMD) (Higgins et al., 2019). Effect sizes were presented along with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Heterogeneity was tested by inspection of the forest plots with the Chi-square test (significance level a priori set at p < 0.1) and the degree of heterogeneity was quantified by the I2 statistics and its 95% confidence interval (CI).

We planned several subgroup analyses with the following considered a-priori variables: people with BN and people with BED; adults versus adolescents; previously treated participants versus not; participants with comorbidities versus no comorbidities; sponsored trials versus not; study duration up to 6 weeks versus longer; treatment groups according to their main therapeutic concept. The following sensitivity analyses on the primary outcomes were planned a-priori: exclusion of non-double-blind studies; exclusion of studies that did not use operationalized criteria to diagnose bulimia/binge eating disorder; exclusion of studies that presented only completer analyses; exclusion of studies with a high risk of bias; fixed effects instead of random effects model; exclusion of studies with imputed data.

Results

Description of Included Studies

We identified 6 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with 698 participants published from 2002 to 2021 through the literature search. The PRISMA flowchart is shown in Fig. 1, and details of all included studies are presented in Table 1. The mean participants’ age was 32.5 years. Of 698 patients, the vast majority were women (94.3%). Two RCTs (De Zwaan et al., 2017; Jenkins et al., 2021; Palmer et al., 2002) compared some type of remotely guided self-help intervention (prearranged telephone calls; via e-mail) with face-to-face guided self-help treatment for 12–16 weeks in patients diagnosed with BN and BED (N = 178). Mitchell et al. (2008), Zerwas et al. (2017) and Yu et al. (2020) compared remote CBT with face-to-face CBT for 16 and 20 weeks respectively in patients with BN (N = 324), but in Mitchel et al. treatment was delivered in individual sessions whereas in Zerwas et al. in group sessions. De Zwaan et al. compared internet-based guided self-help with face-to-face CBT for 16 weeks in patients with BED (N = 178) (De Zwaan et al., 2017; Jenkins et al., 2021; Palmer et al., 2002; Yu et al., 2020). Finally, Yu et al., in a very small study (N = 18), assessed a multidisciplinary approach that comprised of 12 individual 60-min weekly sessions (six CBT and six with a Dietitian Nutritionist) that were delivered for 12 weeks either through videoconference or face-to-face in patients with BED (Yu et al., 2020).

Risk of Bias Assessment

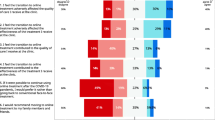

Risk of bias summary is presented in Fig. 2 and the relevant graph in eFig. 1 (Supplement C). All trials had a low risk of bias for random sequence generation, except for one that was characterized as unclear (Mitchell et al., 2008). Most of the studies (De Zwaan et al., 2017; Jenkins et al., 2021; Palmer et al., 2002; Yu et al., 2020) reported unclear allocation concealment, whereas the other two studies had a low risk of bias in this term. All six trials had a high risk of bias according to the blinding of participants and personnel due to the type of interventions. About blinding of outcome assessment, three studies reported low risk of bias (De Zwaan et al., 2017; Jenkins et al., 2021; Mitchell et al., 2008; Zerwas et al., 2017), and the remaining three had high risk of bias (Yu et al., 2020). In addition, four studies had high risk in attrition bias (Jenkins et al., 2021; Mitchell et al., 2008; Yu et al., 2020; Zerwas et al., 2017). Selective reporting had a low risk of bias in all studies. Other bias were unclear at one study (Palmer et al., 2002).

Remission and Frequency of Binge Episodes (Primary Outcomes)

Figure 3 presents the summary RR for remission and Fig. 4 the standardized mean difference for the outcome frequency of binge episodes. More patients in the group with face-to-face interventions (35.8%) were in remission compared to the online group (24.7%) (RR = 0.69, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.89, P = 0.004, 4 RCTs, N = 526). In terms of frequency of binges, there was a trend in favor of face-to-face interventions, but the difference between the two different methods of delivery was small and did not reach statistical significance (SMD = 0.16, 95% CI -0.01 to 0.33, P = 0.06, 5 RCTs, N = 542). Subgroup and sensitivity analyses did not materially change the results.

Secondary Outcomes

No statistically significant differences were found in terms of frequency of purges (MD = 2.23, 95% CI -1.24 to 5.71, P = 0.21, 3 RCTs, N = 368; eFig. 2), response (RR = 0.87, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.00, P = 0.06, 5 RCTs, N = 632; Fig. 5), eating disorder psychopathology (MD = -0.03, 95% CI -0.25 to 0.20, P = 0.81, 5 RCTs, N = 548; eFig. 3), depressive symptoms (SMD = 0.13, 95% CI -0.15 to 0.41, P = 0.35, 4 RCTs, N = 433; eFig. 4), anxiety symptoms (MD = 0.4, 95% CI -2.79 to 3.59, P = 0.81, 1 RCT, N = 179; eFig. 5), weight (MD = -0.82 kg, 95% CI -16.17 to 14.53, P = 0.92, 1 RCT, N = 12; eFig. 6), BMI (MD = -1.32, 95% CI -2.32 to -0.32, P = 0.01, 3 RCTs, N = 353; eFig. 7), quality of life (SMD = 0.00, 95% CI -0.19 to 0.19, P = 0.97, 4 RCTs, N = 433; eFig. 8), total dropouts (RR = 1.35, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.96, P = 0.12, 6 RCTs, N = 681; eFig. 9) and number of patients with adverse effects (RR = 1.52, 95% CI 0.30 to 7.67, P = 0.61, 3 RCTs, N = 494; eFig. 10).

Publication Bias

When fewer than ten studies are included in a meta-analysis, asymmetry testing for funnel plots should not be employed (Egger et al., 1997; Higgins et al., 2019). Since six studies were available (De Zwaan et al., 2017; Jenkins et al., 2021; Mitchell et al., 2008; Palmer et al., 2002; Yu et al., 2020; Zerwas et al., 2017), we could not assess for publication bias using funnel plots.

Discussion

The present is the first meta-analysis that compared the efficacy of face-to-face interventions with remote interventions (e.g., online sessions, telephone sessions, e-mails, SMS, applications) in the treatment of BN and BED. Our review included six studies with a total of 698 participants. Face-to-face interventions were found more effective than remote interventions in terms of abstinence from binge/bulimic episodes; nevertheless, this finding was mainly driven by one study (De Zwaan et al., 2017). Furthermore, participants receiving face-to-face interventions appeared to show a tendency for a reduced frequency of binge episodes compared to remote ones, but the magnitude of difference was very small (SMD 0.16, 95% C.I. -0.01 to 0.33) and again it was driven by De Zwaan et al. study (2017). De Zwaan et al. compared 20 individual face-to-face 50-min CBT sessions with an internet-based guided self-help program that included weekly e-mails and motivational messages from therapists during a 4-month period. Thus, one explanation could be that efficacy differences shown in this study were due to differences in treatment technique (CBT versus guided self-help) and differences in patient-therapist communication (asynchronous and less frequent in the remote group) rather than differences in the mode of treatment delivery itself (face-to-face versus remote). Indeed, all other studies that compared similar interventions found no difference between groups.

To date, the results of RCTs and meta-analyses’ that have been conducted strongly agree on the contribution of distance psychotherapy in reducing binge and bulimic episodes compared to individuals who received no intervention (Aardoom et al., 2013; Melioli et al., 2016). Specifically, with small to moderate between-group effect sizes, Melioli et al. (2016) supported that internet-based treatments are effective in reducing ED symptoms and risk factors. In addition, Aardoom et al. (2013) suggested that internet-based treatments outperformed waiting lists in terms of reducing ED psychopathology, binge eating and purging frequency and quality of life. Comparing internet-based CBT for BN and related eating disorders with waiting list among students (n = 76), Sánchez-Ortiz et al. (2011) suggested that the first is better not only for the eating disorder treatment but also for the improvement of quality of life and affective symptoms. However, for technology-based interventions, the use of a few brief telephone prompts seems significant because it has been found that this kind of co-help can lead to higher adherence rates in patients with BN (Beintner & Jacobi, 2019).

Our findings on eating disorders are in line with the research findings on other mental illnesses. The researchers seem to agree that, across the spectrum of psychiatric diagnoses, remote treatments are as effective as in-person treatments (Barak et al., 2008; Fernandez et al., 2021; Norwood et al., 2018) and significantly better than waiting lists (Fernandez et al., 2021), but face-to-face psychotherapy might be superior to videoconferencing psychotherapy in terms of working alliance (Norwood et al., 2018). For specific mental disorders, no important difference was shown between remote and face-to-face interventions in anxiety (Krzyzaniak et al., 2021; Rooksby et al., 2015), depression (Andrews et al., 2010; Moshe et al., 2021; Richards & Richardson, 2012), obsessive–compulsive disorder (Salazar de Pablo et al., 2023; Wootton, 2016) and panic disorder (Efron & Wootton, 2021). Moreover, smartphone interventions outperformed both waiting lists and control conditions in anxiety disorders (Firth et al., 2017), and remote treatments were found more effective than passive control in panic attack disorder (Efron & Wootton, 2021). The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the need for remote mental health services in modern societies. As far as eating disorders are concerned, the incidence of eating disorder symptoms seems to have increased (Linardon et al., 2022; Phillipou et al., 2020). A 40% of people with eating disorders had a worsening of symptoms between the first weeks of the lockdown, while 60% reported comorbid symptoms of anxiety (Fernández-Aranda et al., 2020). In an observational study carried out during the pandemic, virtual treatments showed a comparable improvement in eating symptoms, weight, and satisfaction with services when compared to similar treatments delivered face-to-face in an heterogeneous sample of patients with eating disorders (Steiger et al., 2022). Another randomized study that compared standard care with smartphone-guided self-help care for BED concluded that the latter was superior for improvement of primary eating disorder symptoms, functioning and associated depressive symptoms (Hildebrandt et al., 2020). However, in the group of standard care (n = 111), no participants received eating disorder-related services, and only 15 received psychiatric services in general, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Lastly, a recent pilot study (Levinson et al., 2021) suggested that a multi-disciplinary telehealth eating disorder intensive outpatient program had comparable outcomes to face-to-face intensive outpatient program treatment.

The primary limitation of the present meta-analysis was the small number of included RCTs. Despite conducting a comprehensive literature search across various databases, trial registries, and reference lists, only a limited number of clinical trials that directly compared remote interventions with face-to-face interventions in patients with BN or BED could be identified. While it's possible that including additional databases might have improved the sensitivity of the screening process, we believe it is unlikely that any RCTs have been missed. Our inclusion criteria focused on RCTs due to concerns that non-randomized trials could introduce additional bias related to patient selection and uncontrolled confounding variables. This is particularly relevant because patients with specific characteristics, such as those who are less severely ill, might be the primary recipients of remote interventions, potentially influencing the outcomes. Conversely, real-world non-randomized comparative studies offer valuable insights into intervention performance within real-world settings. These studies adeptly capture the intricacies and nuances of real-life situations. Moreover, they can accommodate larger sample sizes, extend over more prolonged periods, and provide data for cost-effectiveness analyses. However, due to our exclusive focus on RCTs, the number of trials and participants remained limited. For psychiatric meta-analyses to be robust, typically more than 1000 included participants are needed. Effect sizes may change significantly with the addition of new RCTs (Trikalinos et al., 2004).

Furthermore, our a priori defined response criterion (at least 50% bulimic/binge-eating episodes) was not indicated in any study; consequently, we had to recur to authors' definitions of response. Nevertheless, the use of different response criteria does not lead to markedly different results in meta-analyses as long as relative risks or odds ratios are used as measures of the effect size (Furukawa et al., 2011). Another significant limitation of the present meta-analysis was the fact that all included studies examined CBT or guided self-help interventions; thus, it is unclear whether the results apply to all remote interventions. No obvious difference between remote versus face-to-face interventions was suggested, but additional analyses on other therapist-led interventions would be important. Lastly, most studies had high drop-out rates and no study could have a double-blind design as both the therapists and the participants were aware of the nature of the intervention, id est whether it was a face-to-face or a remote intervention.

Our meta-analysis suggests that the efficacy of remote interventions does not differ from face-to-face interventions for the treatment of BN and BED, highlighting the potential important contribution of this form of delivery given the modern societies’ needs.. Flexibility and convenience offered through remote interventions, as well as privacy and reduced stigma may encourage more individuals who would otherwise go untreated to engage with evidence-based treatment. This is particularly important for individuals with BSDs, as it has been consistently emphasized that timely access to evidence-based treatment poses challenges within this patient group (Cooper & Kelland, 2015; Kazdin et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2022). Increased utilization of remote interventions may also have wider implications for healthcare systems. Quality of care for individuals with Binge spectrum disorders may improve as a consequence of timely access to evidence-based interventions, optimised healthcare resource allocation, and ultimately reduced burden and costs of care.

However, it has to be emphasized that more research is needed to reach clearer and safer conclusions. The existing RCT evidence, while promising, remains limited and therefore robust clinical conclusions cannot be reached. Furthermore, more research is needed to explore the aforementioned implications in the wider context of improving quality in healthcare.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Prof. Myrto Samara, upon reasonable request.

References

Aardoom, J. J., Dingemans, A. E., Spinhoven, P., & Van Furth, E. F. (2013). Treating eating disorders over the internet: A systematic review and future research directions. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 46(6), 539–552. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22135

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-V. American Psychiatric Publishing Inc.

Andrews, G., Cuijpers, P., Craske, M. G., McEvoy, P., & Titov, N. (2010). Computer therapy for the anxiety and depressive disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: A meta-analysis. Plos One, 5(10). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0013196

Argyrou, A., Lappas, A. S., Bakaloudi, D. R., Tsekitsidi, E., Mathioudaki, E., Michou, N., Polyzopoulou, Z., Christodoulou, N., Papazisis, G., Chourdakis, M., & Samara, M. T. (2023). Pharmacotherapy compared to placebo for people with Bulimia Nervosa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 327, 115357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2023.115357

Barak, A., Hen, L., & Boniel-nissim, M. (2008). A Comprehensive Review and a Meta-Analysis of the Effectiveness of Internet- Based Psychotherapeutic Interventions. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 26(2), 109–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228830802094429

Beintner, I., & Jacobi, C. (2019). Impact of telephone prompts on the adherence to an Internet-based aftercare program for women with bulimia nervosa: A secondary analysis of data from a randomized controlled trial. Internet Interventions, 15, 100–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2017.11.001

Brownley, K. A., Berkman, N. D., Peat, C. M., Lohr, K. N., Cullen, K. E., Bann, C. M., & Bulik, C. M. (2016). Binge-eating disorder in adults a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine, 165(6), 409–420. https://doi.org/10.7326/M15-2455

Carrard, I., Crépin, C., Rouget, P., Lam, T., Golay, A., & Van der Linden, M. (2011). Randomised controlled trial of a guided self-help treatment on the Internet for binge eating disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49(8), 482–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2011.05.004

Cooper, M., & Kelland, H. (2015). Medication and psychotherapy in eating disorders: Is there a gap between research and practice? Journal of Eating Disorders, 3(1), 4–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-015-0080-0

De Zwaan, M., Herpertz, S., Zipfel, S., Svaldi, J., Friederich, H. C., Schmidt, F., Mayr, A., Lam, T., Schade-Brittinger, C., & Hilbert, A. (2017). Effect of internet-based guided self-help vs individual face-to-face treatment on full or subsyndromal binge eating disorder in overweight or obese patients: The INTERBED randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(10), 987–995. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2150

Efron, G., & Wootton, B. M. (2021). Remote cognitive behavioral therapy for panic disorder: A meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 79, 102385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2021.102385

Egger, M., Smith, G. D., Schneider, M., & Minder, C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ, 315(7109), 629–634. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

Fernández-Aranda, F., Casas, M., Claes, L., Bryan, D. C., Favaro, A., Granero, R., Gudiol, C., Jiménez-Murcia, S., Karwautz, A., Le Grange, D., Menchón, J. M., Tchanturia, K., & Treasure, J. (2020). COVID-19 and implications for eating disorders. European Eating Disorders Review, 28(3), 239–245. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2738

Fernandez, E., Woldgabreal, Y., Day, A., Pham, T., Gleich, B., & Aboujaoude, E. (2021). Live psychotherapy by video versus in-person: A meta-analysis of efficacy and its relationship to types and targets of treatment. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 28(6), 1535–1549. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2594

Fichter, M. M., Quadflieg, N., & Hedlund, S. (2008). Long-term course of binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa: Relevance for nosology and diagnostic criteria. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 41(7), 577–586. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20539

Firth, J., Torous, J., Nicholas, J., Carney, R., Rosenbaum, S., & Sarris, J. (2017). Can smartphone mental health interventions reduce symptoms of anxiety? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Affective Disorders, 218, 15–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.04.046

Fornaro, M., Mondin, A.-M., Billeci, M., Fusco, A., De Prisco, M., Caiazza, C., Micanti, F., Calati, R., Carvalho, A. F., & de Bartolomeis, A. (2023). Psychopharmacology of eating disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Affective Disorders, 338, 526–545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.06.068

Furukawa, T. A., Akechi, T., Wagenpfeil, S., & Leucht, S. (2011). Relative indices of treatment effect may be constant across different definitions of response in schizophrenia trials. Schizophrenia Research, 126(1–3), 212–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2010.10.016

Higgins, J., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M., & Welch, V. (2019). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Hildebrandt, T., Michaeledes, A., Mayhew, M., Greif, R., Sysko, R., Toro-Ramos, T., & DeBar, L. (2020). Randomized controlled trial comparing health coach-delivered smartphone-guided self-help with standard care for adults with binge eating. American Journal of Psychiatry, 177(2), 134–142. https://doi.org/10.1176/APPI.AJP.2019.19020184

Hoge, C. W., Castro, C. A., Messer, S. C., McGurk, D., Cotting, D. I., & Koffman, R. L. (2004). Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. New England Journal of Medicine, 351(1), 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa040603

Jacobs, J. C., Blonigen, D. M., Kimerling, R., Slightam, C., Gregory, A. J., Gurmessa, T., & Zulman, D. M. (2019). Increasing mental health care access, continuity, and efficiency for veterans through telehealth with video tablets. Psychiatric Services, 70(11), 976–982. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201900104

Jenkins, P. E., Hoste, R. R., Meyer, C., & Blissett, J. M. (2011). Eating disorders and quality of life: A review of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(1), 113–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.08.003

Jenkins, P. E., Luck, A., Violato, M., Robinson, C., & Fairburn, C. G. (2021). Clinical and cost-effectiveness of two ways of delivering guided self-help for people with an eating disorder: A multi-arm randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 54(7), 1224–1237. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23554

Kazdin, A. E., Fitzsimmons-Craft, E. E., & Wilfley, D. E. (2017). Addressing critical gaps in the treatment of eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 50(3), 170–189. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22670

Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P. A., Chiu, W. T., Deitz, A. C., Hudson, J. I., Shahly, V., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Angermeyer, M. C., Benjet, C., Bruffaerts, R., De Girolamo, G., De Graaf, R., Maria Haro, J., Kovess-Masfety, V., O’Neill, S., Posada-Villa, J., Sasu, C., Scott, K., … & Xavier, M. (2013). The prevalence and correlates of binge eating disorder in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Biological Psychiatry, 73(9), 904–914. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.11.020

Krzyzaniak, N., Greenwood, H., Scott, A. M., Peiris, R., Cardona, M., Clark, J., & Glasziou, P. (2021). The effectiveness of telehealth versus face-to face interventions for anxiety disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X211053738

Levinson, C. A., Spoor, S. P., Keshishian, A. C., & Pruitt, A. (2021). Pilot outcomes from a multidisciplinary telehealth versus in-person intensive outpatient program for eating disorders during versus before the Covid-19 pandemic. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 54(9), 1672–1679. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23579

Linardon, J., Messer, M., Rodgers, R. F., & Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M. (2022). A systematic scoping review of research on COVID-19 impacts on eating disorders: A critical appraisal of the evidence and recommendations for the field. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 55, 3–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23640

Liu, L., Hay, P., & Conti, J. (2022). Perspectives on barriers to treatment engagement of people with eating disorder symptoms who have not undergone treatment: A qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry, 22(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-03890-7

Ljotsson, B., Lundin, C., Mitsell, K., Carlbring, P., Ramklint, M., & Ghaderi, A. (2007). Remote treatment of bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder: A randomized trial of Internet-assisted cognitive behavioural therapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(4), 649–661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2006.06.010

Malik, K., Shetty, T., Mathur, S., Jose, J. E., Mathews, R., Sahay, M., Chauhan, P., Nair, P., Patel, V., & Michelson, D. (2023). Feasibility and Acceptability of a Remote Stepped Care Mental Health Programme for Adolescents during the COVID-19 Pandemic in India. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20031722

Melioli, T., Bauer, S., Franko, D. L., Moessner, M., Ozer, F., Chabrol, H., & Rodgers, R. F. (2016). Reducing eating disorder symptoms and risk factors using the internet: A meta-analytic review. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 49(1). https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22477

Mitchell, J. E., Crosby, R. D., Wonderlich, S. A., Crow, S., Lancaster, K., Simonich, H., Swan-Kremeier, L., Lysne, C., & Myers, T. C. (2008). A randomized trial comparing the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa delivered via telemedicine versus face-to-face. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 46(5), 581–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2008.02.004

Moghimi, E., Davis, C., Bonder, R., Knyahnytska, Y., & Quilty, L. (2022). Exploring women’s experiences of treatment for binge eating disorder: Methylphenidate vs. cognitive behavioural therapy. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2021.110492

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ (online), 339(7716), 332–336. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535

Moshe, I., Terhorst, Y., Philippi, P., Domhardt, M., Cuijpers, P., Cristea, I., Pulkki-Råback, L., Baumeister, H., & Sander, L. B. (2021). Digital interventions for the treatment of depression: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 147(8), 749–786. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000334

Norwood, C., Moghaddam, N. G., Malins, S., & Sabin-Farrell, R. (2018). Working alliance and outcome effectiveness in videoconferencing psychotherapy: A systematic review and noninferiority meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 25(6), 797–808. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2315

Palmer, R. L., Birchall, H., McGrain, L., & Sullivan, V. (2002). Self-help for bulimic disorders: A randomised controlled trial comparing minimal guidance with face-to-face or telephone guidance. British Journal of Psychiatry, 181, 230–235. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.181.3.230

Phillipou, A., Meyer, D., Neill, E., Tan, E. J., Toh, W. L., Van Rheenen, T. E., & Rossell, S. L. (2020). Eating and exercise behaviors in eating disorders and the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia: Initial results from the COLLATE project. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(7), 1158–1165. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23317

Richards, D., & Richardson, T. (2012). Computer-based psychological treatments for depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(4), 329–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.02.004

Rooksby, M., Elouafkaoui, P., Humphris, G., Clarkson, J., & Freeman, R. (2015). Internet-assisted delivery of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for childhood anxiety: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 29(1), 83–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.11.006

Salazar de Pablo, G., Pascual-Sánchez, A., Panchal, U., Clark, B., & Krebs, G. (2023). Efficacy of remotely-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: An updated meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Journal of Affective Disorders, 322, 289–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.11.007

Sánchez-Ortiz, V. C., Munro, C., Stahl, D., House, J., Startup, H., Treasure, J., Williams, C., & Schmidt, U. (2011). A randomized controlled trial of internet-based cognitive-behavioural therapy for bulimia nervosa or related disorders in a student population. Psychological Medicine, 41(2), 407–417. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291710000711

Steiger, H., Booij, L., Crescenzi, O., Oliverio, S., Singer, I., Thaler, L., St-Hilaire, A., & Israel, M. (2022). In-person versus virtual therapy in outpatient eating-disorder treatment: A COVID-19 inspired study. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 55(1), 145–150. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23655

Stice, E., Nathan Marti, C., & Rohde, P. (2013). Prevalence, incidence, impairment, and course of the proposed DSM-5 eating disorder diagnoses in an 8-year prospective community study of young women. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122(2), 445–457. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030679

Termorshuizen, J. D., Watson, H. J., Thornton, L. M., Borg, S., Flatt, R. E., MacDermod, C. M., Harper, L. E., van Furth, E. F., Peat, C. M., & Bulik, C. M. (2020). Early impact of COVID-19 on individuals with self-reported eating disorders: A survey of ~1,000 individuals in the United States and the Netherlands. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(11), 1780–1790. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23353

Trikalinos, T. A., Churchill, R., Ferri, M., Leucht, S., Tuunainen, A., Wahlbeck, K., & Ioannidis, J. P. A. (2004). Effect sizes in cumulative meta-analyses of mental health randomized trials evolved over time. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 57(11), 1124–1130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.02.018

Williams, S. E., Watts, T. K. O., & Wade, T. D. (2012). A review of the definitions of outcome used in the treatment of bulimia nervosa. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(4), 292–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.01.006

Wootton, B. M. (2016). Remote cognitive-behavior therapy for obsessive-compulsive symptoms: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 43, 103–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.10.001

Yu, Z., Roberts, B., Snyder, J., Stuart, K., Wilburn, J., Pudwill, H., & Cortazzo, K. (2020). A Pilot Study of a Videoconferencing-Based Binge Eating Disorder Program in Overweight or Obese Females. Telemedicine and E-Health, 27(3), 330–340. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2020.0070

Zerwas, S. C., Watson, H. J., Hofmeier, S. M., Levine, M. D., Hamer, R. M., Crosby, R. D., Runfola, C. D., Peat, C. M., Shapiro, J. R., Zimmer, B., Moessner, M., Kordy, H., Marcus, M. D., & Bulik, C. M. (2017). CBT4BN: A Randomized Controlled Trial of Online Chat and Face-to-Face Group Therapy for Bulimia Nervosa. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 86(1), 47–53. https://doi.org/10.1159/000449025

Acknowledgements

Authors wish to thank Hunna Watson and Andrea Wyssen for providing further information on their trials.

Funding

Open access funding provided by HEAL-Link Greece. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design: MS, MC; data collection: NM, AA, EM, DB, ET, ZP; analysis and interpretation of results: MS, NM, AL; draft manuscript preparation: MS, AL; Writing review and editing: NC, GP, MC. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Author MS received honoraria as a consultant or for lectures for Lundbeck and Viatris. All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Samara, M.T., Michou, N., Argyrou, A. et al. Remote vs Face-to-face Interventions for Bulimia Nervosa and Binge-eating Disorder: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. technol. behav. sci. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-023-00345-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-023-00345-y