Abstract

Recent research has observed that among the ever-increasing young users of social networking sites (e.g., Facebook), some present problematic use similar to other behavioral addictions. While regular use of Facebook is not systematically associated with mental health disorders, its addictive use has been consistently associated with higher level of depression and loneliness. Therefore, further research is needed in studying the separate impacts of regular and addictive Facebook use on young adults’ lives. The present study explored the role of Facebook addiction and social comparison on mental health and types of social networking sites (SNSs) usage (i.e., active versus passive usage), hypothesizing that addiction and social comparison will predict negative mental health outcomes and higher SNS usage. The study sample comprised 280 students at a British university. The data were analyzed using structural equation modelling to test for the significance of the relationships between these variables as well as the appropriateness of the overall hypothesised model. Results demonstrated that Facebook addiction significantly predicted depression, loneliness, and both active and passive SNS usage, and social comparison significantly predicted the level of depression significantly. The overall model also demonstrated a good fit which indicates that the hypothesized associations between the variables were strong. It is argued that the association between Facebook addiction and mental health could be a vicious cycle because no causation direction can be excluded. The implications of the study findings and future research directions are also discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Social networking sites (SNSs) and use of them have shown constant growth with 3.8 billion users globally in January 2020 (Statista, 2020). The number of Facebook users, currently the most popular SNS worldwide, has shown similar growth, and reached approximately 2.5 billion users in 2019 (Facebook, 2020). Over the years, SNS use has grown, allowing users to communicate with larger numbers of individuals and find further social support (e.g., Brailovskaia et al., 2018). SNSs provide users with multiple opportunities to express themselves or gain access to information and communication to create useful networks (Ellison et al., 2007). However, there is evidence associating young individual’s (in between ages of 18–25 as specified by Walker-Harding et al., 2017) SNS use with various mental health problems and unhealthy habits (Kuss & Griffiths, 2011; Yau et al., 2014). Research on this topic has highlighted that unhealthy SNS use shares similarities with other behavioral addictions and has been termed “SNS addiction” or “social media addiction” in a general capacity (Kuss & Griffiths, 2011), and (for example) “Facebook addiction” (Pontes et al., 2018), “YouTube addiction” (Balakrishnan & Griffiths, 2017), and “Instagram addiction” (Kircaburun & Griffiths, 2018) when referring to individual platforms.

Such addiction relating to SNSs could be due to the extended online access arising from the instant messages and push notifications users receive, which in turn can lead to problematically long and repetitive activities/use (Griffiths, 2018; Rozgonjuk et al., 2018). It is also associated with the “Fear of Missing Out” (FoMO), defined as the feeling that other individuals are going through positive/rewarding events when one is not connected (Przybylski et al., 2013). Studies have demonstrated that FoMO is significantly related to both frequency of SNS use (Barry et al., 2017; Blackwell et al., 2017; Franchina et al., 2018) and problematic SNS use (Elhai et al., 2016, Fabris et al., 2020; Müller et al., 2020), which further confirms that the social aspect of being on such sites is highly associated with the problematic use. Consequently, individuals with higher social identity and telepresence may also show tendencies to use SNSs more often and extensively (Kwon & Wen, 2010; Ross et al., 2009). For example, keeping in touch with friends, family, and relatives are some of the reasons for individuals to stay online so they do not feel lonely. Preference for offline contact/relationships is also prevalent in SNS use with some users preferring to use text messaging for communication rather than face-to-face interactions (Kujath, 2011). This specific form of virtual communication may predict potential addiction due to its enticing and interactive mechanisms (Sussman et al., 2011).

There has also been much debate concerning the association between SNS use and negative mental health outcomes such as depression and loneliness (e.g., Lee et al., 2015; Rosen et al., 2013). According to the latest (fifth) edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013), depressive disorder is an umbrella concept including different mental disorders (e.g., persistent depressive disorder, major depressive disorder) which have been regrouped into a single section due to their shared presence of mood modification (i.e., presence of sadness/emptiness feeling, sleep disturbance, and thoughts of death). Depression is highly prevalent in modern societies (e.g., 20.6% of US adults experienced a major depressive disorder episode in their lifetime; Hasin et al., 2018) and has been much studied in relation to Facebook. Globally, the association between depression and Facebook addiction appears clear and unilateral; the more individuals engage in addictive use of Facebook, the more depressed they feel (e.g., Brailovskaia & Margraf, 2017; Brailovskaia et al., 2019). However, the relationship between healthier use of Facebook and depression is less straightforward because the results suggest (i) no association (e.g., Błachnio et al., 2015; Chow & Wan, 2017), (ii) a positive association (e.g., Rosen et al., 2013; Thorisdottir et al., 2019), or (3) a negative association between these variables (e.g., Brailovskaia & Margraf, 2016).

One of the reasons suggested by the researchers to explain these contrasting results is social comparison (Wheeler & Suls, in press), which can be either downward (i.e., comparing oneself to less fortunate individuals) or upward (i.e., comparing oneself to more fortunate individuals). Due to the biased way Facebook users present themselves online (i.e., focusing on the more positive aspect of their lives; Ellison et al., 2006), users will be more prone to compare upward rather than downward (e.g., Fox & Moreland, 2015). Interestingly, while downward comparison in real life has been associated with higher wellbeing (Wang et al., 2017), the opposite has been shown for upward comparison which appears to lead to higher depression and anxiety (McCarthy & Morina, 2020). Overall, one would expect to see a significant positive association between Facebook use and depression among users who are more prone to use social comparison, while this relationship would disappear for users are less prone to social comparison (e.g., Alfasi, 2019; Nisar et al., 2019).

Another variable potentially affecting the association between Facebook addiction and mental health is the type of use (i.e., active and passive use of SNS). Active SNS use is defined as the type of use that facilitates direct exchanges such as writing and sharing blogs or posts, along with posting pictures and videos on SNSs to stay connected with friends and family (Montague & JieXu, 2012). On the other hand, passive SNS use includes activities such as reading information by browsing. This involves scrolling through news feed and viewing posts without commenting on them (Verduyn et al., 2015). Interestingly, it has been pointed out that problematic SNS use is more associated with active use of SNS, specifically with the use of videogames on these sites (Jeong et al., 2016). Thorisdottir et al. (2019) found that active use led to lower levels of depression while passive use was associated with higher levels of depression. Furthermore, the type of Facebook use interacted significantly with social comparison in predicting the level of depression (Nisar et al., 2019); While active Facebook use led to less social comparison, using Facebook passively was related to more social comparison, with this latter variable leading to more depressive symptoms. It is noteworthy that envy (i.e., a hostile emotion resulting from an individual observing someone having something that they desire; Smith & Kim, 2007), which can be seen as a consequence of the upward social comparison, has also been found to moderate the association between Facebook surveillance (i.e., one of the passive use aspects) and depression (Tandoc et al., 2015). The more the participants are prone to Facebook surveillance, the more they envy their Facebook friends, leading to higher level of depression.

Like depression, loneliness has often been studied in relation to Facebook use and addiction (e.g., Biolcati et al., 2018; Ryan & Xenos, 2011). Loneliness is defined as a discrepancy between desired social relationships and the ones experienced (Perlman & Peplau, 1981). This is of interest because it has been shown that experiencing loneliness is directly related to higher levels of depression (Mushtaq et al., 2014). The association between loneliness and Facebook addiction is relatively straightforward because Facebook addiction is related to higher levels of loneliness (e.g., Rajesh & Rangaiah, 2020; Shettar et al., 2017). On the other hand, the research on the association between Facebook use and loneliness may appear contradictory at first glance (e.g., Lemieux et al., 2013; Skues et al., 2012) although an in-depth exploration of the literature has clarified the nature of these observations. Indeed, some variables inherent of Facebook use interact differently with the level of loneliness experienced by the users. For example, the number of friends a user has on Facebook is directly and negatively associated with loneliness (Jin, 2013; Phu & Gow, 2019). Furthermore, the number of overlapping friends (i.e., friends sharing both an online and offline friendship) similarly predicts a lower level of loneliness (Jin, 2013).

In addition, Facebook active use may affect the level of loneliness experienced. For example, the frequency of commenting on other individual’s posts has been negatively associated with the loneliness experienced (Scott et al., 2018). Interestingly, a longitudinal study explored the interaction between two types of loneliness (i.e., emotional and social) and active Facebook use (Wang et al., 2018). The study showed that both types of loneliness levels at follow up (T2; i.e., 1 year after the baseline test) were predicted through a quadratic model by active use at baseline (T1). This relationship indicated that for low level user, an increase in the active use of Facebook results in a reduction of loneliness, an increase in loneliness being observed for higher level use of Facebook.

Interestingly, the emotional loneliness scores at T1 also showed the same type of interaction with the active use of Facebook at T2 although social loneliness did not show this trend. The impact of Facebook use on loneliness appears to be confirmed by Deters and Mehl (2013) who observed that when asking their participants to post more than usual, their level of loneliness decreased compared to a control group posting as they would usually do (i.e., after a two-month period). Similarly, there could be an association between active SNS use and addiction. Andreassen et al. (2012) found that active SNS use was correlated with SNS addiction, suggesting that behavioral addictions could have varying psychopathological dimensions. Increased exposure to SNS use can lead to increased social capital (connects network of relationships among individuals who live in society (Ellison et al., 2007), enabling information-sharing) and emotional support (Deters & Mehl, 2013). However, over-exposure to passive SNS use could reinforce addictive checking behaviors if not handled correctly and could undermine psychological wellbeing (Verduyn et al., 2015).

Aims and Objectives

The present study explores the role of Facebook addiction and social comparison upon mental health and types of SNS use, with a broad hypothesis that addiction and social comparison will predict negative mental health outcomes and higher SNS use. As previous studies were mainly focused in using Facebook and university students, the present study also uses a non-clinical sample group of emerging adults to avoid a biased reflection on SNS and its users as a generalization. Additionally, there is no clear research suggesting regular active or passive SNS use would contribute to either addiction or social comparison because most research only focuses on excessive or abusive SNS use. The present study thus can help clinicians to better understand the effects of regular SNS use towards mental health, to improve intervention programs for young adults to engage in healthy SNS use, as well as on the British National Health Service budget.

Consequently, the following hypotheses are proposed: (H1) social comparison will predict loneliness, depression, and both active/ passive SNS use; (H2) Facebook addiction will predict loneliness, depression, and both active/passive SNS use; and (H3) loneliness and depression will show a positive association.

Methods

Participants

Using the analysis of G*Power (Faul et al., 2009), it was calculated that for a power of .95, an effect size of .25 (medium effect size), and an alpha constant of .05, a minimum sample size of 210 was required. A medium effect size was chosen because all scales scored good internal validity which means it is believed it would be able to detect a difference. Following the age range of young adults as defined earlier, participants in between 18 and 25 years of age were invited to take part in the study and there were no other exclusion criteria. Initially, 315 participants completed the questionnaire but the date from 35 of them had to be removed due to missing data. The final sample comprised 280 participants (Mage=22.01 years, SD=3.76) with 51 males and 229 females (three preferring not to say). The majority of the participants reported being students (N = 244), the remainder of the participants (i.e., N = 36) were either working full-time (86.44%), working part-time (8.47%), or unemployed (5.08%). Most of the students were full-time to the exception of 8 who were part-time and could have been working part-time. All participants in the study were required to be English-speaking and were recruited through opportunistic sampling.

Measures

Active and Passive SNS Use

Li'S (2016) Active and Passive SNS Use Scale was used to assess active and passive SNS use. The scale used was adapted from Pagani and Mirabello's (2011) research. The scale comprises seven items (e.g., “I comment on other posts on social media sites” for active use and “I “like” posts on companies Facebook sites” for passive use) scored on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The first four items assess active use, and the last three items assess passive use (Li, 2016). The Cronbach’s alpha in the original study was.90 for active use and .81 for passive use.

Facebook Addiction

Facebook addiction was assessed with the Facebook Addiction Scale (Koc & Gulyagci, 2013). The scale comprises eight items (e.g., “My Facebook use interferes with doing social activities”) scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not true) to 5 (extremely true). Higher the scores designate a higher level of addiction. The Cronbach’s alpha in the original study was .84.

Loneliness

To assess subjective loneliness, Baek et al.’s (2014) Loneliness Scale was used. The scale was adapted from Russell’s (1996) UCLA Loneliness Scale and comprises five items scored on a 6-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree) (e.g., “When using social networking sites, I feel left out”). The Cronbach alpha in Baek et al’s (2014) study was .86.

Social Comparison

The Iowa-Netherlands Comparison Orientation scale was used to assess social comparison among participants (Gibbons & Buunk, 1999). This scale comprises 11 items and participants rate how well each statement (e.g., “I often compare myself with others with respect to what I have accomplished in life”) applies to them on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very well). The Cronbach alpha in the original study varied between .77 and .85 based on the population (i.e., therapists, students, adults, and cancer patients) and the country (i.e., USA and The Netherlands).

Depression

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ;Spitzer et al., 1999) was used to assess depression. However, Item 9 was removed at the request of the research team’s university ethics committee. Therefore, the scale comprised eight items (e.g., “Little interest or pleasure in doing things”) with scores ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). The PHQ asks participants to list depressive symptoms over the past 2 weeks. The Cronbach alpha was not reported in the original study, but Jelenchick et al. (2013) obtained a Cronbach’s alpha of .89 in a recent study.

Procedure

The survey was created on Qualtrics, and the web-link was posted on the first author’s Instagram and Facebook pages as well as other student group pages. Participants completed the questionnaire online. There was no time limit for the duration of the survey and participants were told to take as much time as was necessary. Participation was voluntary and no monetary awards were given. A debriefing statement was presented to the participants at the end of the questionnaire.

Statistical Analysis

IBM SPSS statistic (version 26) was used for the statistical analysis. As the data were normally distributed (i.e., see Table 1 for more details) and average score was used for every scale, parametric tests were used. Based on this, the dichotomic variable (i.e., gender) was examined using an independent sample t-test. The relationships between the continuous variables tested were first explored through correlational analysis, allowing further testing with structural equation modelling (SEM) using AMOS 25.0.

Ethics

The study procedures were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Furthermore, the study was approved by the ethics committee at the first author’s university. Participants were provided with an information sheet with a brief explanation of the study and the impact of their contribution and had to click a box to indicated informed consent prior to taking part.

Results

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for the different self-report measures included within the study. None of the scores’ distribution were outside of the normality range for both the skewness and kurtosis, indicating normal distributions. Furthermore, the Cronbach’s alphas were all within an acceptable range.

Due to the biased gender distribution of males and females in this study (i.e., 51 males for 229 females), 51 female participants matching the males in term of age and occupation (i.e., students or non-students) were selected for the gender-based t-test. Perfect matches were systematically found except for one participant whose counterpart was 1 year older, for this reason, the counterpart of another participant was replaced by a female one year younger. This modification led to perfectly matched groups (i.e., F(100) = 0.000, p = 1.000 for the age and X2 = .000, p = 1.000 for the occupation). These two groups were therefore compared on all the self-reported measures, indicating no significant difference although the passive use approached significance with females (M = 5.37, SD = 1.39) scoring higher than males (M = 4.87, SD = 1.39), F(100) = 0.055, p = .07. Due to this lack of difference between the genders, the remainder of the statistical analyses was run using the whole sample.

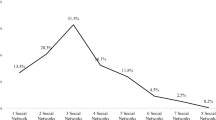

Prior to moving onto a full SEM, a correlational analysis was conducted to get initial insights on the data. As can be seen in Table 2, passive use was positively correlated with active use, these scores correlating similarly with Facebook Addiction score, but only active use correlating with the social comparison. Facebook Addiction correlated positively with all the variables included except for age, which showed a negative correlation. Finally, both loneliness and depression correlated with the social comparison but with neither the passive nor active use of Facebook.

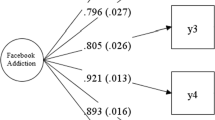

A SEM using AMOS 25.0 was then run to test for the hypothesized relationships between the variables (see Fig. 1). An adequate fit is assumed if the CFI and TLI are greater than .90, RMSEA is below .08, and relative chi-square (CMIN /df) is below 3 (Maxwell et al., 2005). The model showed an adequate fit, with X2/df= 1.638; p=.108; CFI=.985; TLI=.971; RMSEA=.047. Social comparison was a significant predictor for depression, and Facebook addiction significantly predicted all dependent variables, loneliness, depression, and active and passive SNS use. There was a significant correlation between the two predictor variables, social comparison and Facebook addiction. The error terms for active and passive SNS use were also correlated, which indicates that there was likely a significant covariance between the two variables.

Discussion

The present study investigated how social comparison and Facebook addiction predicted mental health outcomes and types and intensity of SNS use among emerging adults at a British university. Overall, the model tested in the present study demonstrated significant associations between the variables as indicated by the good overall fit observed. As hypothesized, higher level of Facebook addiction was significantly associated with heightened loneliness and depression, as well as higher active and passive SNS use. Furthermore, social comparison significantly correlated with Facebook addiction and predicted the level of depression, where higher social comparison was associated with higher levels of addiction and depression. The findings also demonstrated that loneliness and depression were closely associated.

The role of social comparison and Facebook addiction in predicting negative mental health outcomes and types of SNS use provides a better understanding of the adverse mechanisms associated with SNS use. Those who tend to make more social comparison and those who demonstrate addictive tendencies are more likely to experience negative mental health and use SNSs more (i.e., both passively and actively). The findings are consistent with Pantic (2014) and Mackson et al. (2019) who argued that social comparison leads to depression and loneliness via SNS use. In relation to the association between Facebook addiction and loneliness, both causality directions have been studied in the literature, making it unclear whether loneliness would be the cause (Biolcati et al., 2018; Rajesh & Rangaiah, 2020) or consequence (Shettar et al., 2017) of SNS addiction. The present model indicated that loneliness appears to be a consequence of Facebook addiction which provides partial support to the literature (Song et al., 2014). However, based on these results, the possibility of a “vicious cycle” type of association (i.e., loneliness leading to an increased addiction resulting in more loneliness and so on) cannot be excluded and should be considered in future longitudinal studies. Having a clearer picture of the associations between Facebook use and addiction and their potential impact on mental health is crucial in contemporary society because number of SNS users keeps increasing. Having observed the significant relationships, better understanding of how Facebook/SNS use leads to deteriorated mental health would help develop and improve interventions aimed at young individual’s mental health, and addiction-related issues in particular.

Two potential variables should be explored in future research on the mechanisms underlying SNS use and mental health. Firstly, the time spent online/on SNSs appears to predict both social comparison and addiction, which in turn can lead to negative mental health outcomes (Frison & Eggermont, 2016). While no significant correlation was found between the types of SNS use (i.e., passive and active use) and mental health (i.e., depression and loneliness) in the present study, the inclusion of time spent on SNSs could have altered the results. For example, Deters and Mehl (2013) highlighted that the time spent actively using SNSs affected the level of loneliness experienced one year later, indicating that the type of use and the time spent on SNS interact in their prediction of mental health. Another variable of interest to include in further models of Facebook addiction would be FoMO which is recognised as a key concept in this addiction and its association with negative mental health. Indeed, young adults may be experiencing FoMO, making them want to stay closely connected with their friends and family, which could explain why these specific users tend to be heavy/addictive users and how they could use it in such a way that depicts themselves in a positive light (Yin et al., 2019). Recent studies have indeed found FoMO to be associated with both loneliness and social comparison (Reer et al., 2019), and as a predictor of depression (Barry et al., 2017; Fabris et al., 2020).

Notably, the present study found that active and passive SNS use to be highly and positively correlated although the two types of use should logically differ. Indeed, while an active user will have direct interaction with other users (e.g., commenting on their post, messaging other individuals), the passive user will be quieter (e.g., browsing their newsfeeds, reading other posts). This assumption is further supported by Nisar and colleagues (2019) who found a strong negative correlation between these two constructs, although these authors used a different scale that they created for their own study. This issue is interestingly reflected by the face validity of this scale, as one item from the active scale (i.e., “I ‘like’ posts on companies’ Facebook pages”) could be interpreted as part of the passive use of Facebook. Indeed, other scales distinguishing between passive and active use of Facebook (e.g., Frison & Eggermont, 2015) did not include this behavior in either type of use, but rather in separate categories associated with the positive feedback. However, although these two concepts were strongly interrelated, only the active use of Facebook was significantly associated with social comparison. This finding indicates that these two types of use might remain slightly different from each other, although further research is needed to delineate the distinction as well as the assessment of active and passive use.

Although the present work aimed to examine a more unbiased and representative young adult population compared to the previous studies, our sample still showed a bias towards students and female participants. Nonetheless, this limitation is unlikely to impact the generalizability of this study, due to the lack of difference observed between the male and female participants observed in this study. Furthermore, despite our efforts to collect a more representative sample, a majority of our sample also consisted of university students (i.e., 86%). This can, however, be explained by the fact that a large proportion of young adults in the UK are attending university, making this sample rather representative of that group age. Another limitation pertaining to the methodology employed in the present study is the lack of causality exploration due to its cross-sectional nature. Therefore, although the SEM model based on previous literature may imply a logical causality, this causality should be further explored through longitudinal studies in future research.

Conclusion

In brief, the present study expands the current literature concerning Facebook addiction by examining at the role of social comparison and Facebook addiction in predicting types of SNS use and mental health. The analysis showed that Facebook addiction is associated with increased levels of loneliness and depression as well as an increased use of both passive and active use. Furthermore, Facebook addiction was closely related to social comparison, which, in itself was also associated with depression. However, these results are to be taken cautiously due to the limitations inherent to this study. However, the findings highlight the importance of examining the associations between various aspects of Facebook use and addiction further with mental health outcomes and provides a better understanding of how and why SNs use may lead to negative mental health among young adults.

Data Availability

Data can be provided/shared upon request.

References

Alfasi, Y. (2019). The grass is always greener on my Friends’ profiles: the effect of Facebook social comparison on state self-esteem and depression. Personality and Individual Differences, 147, 111–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.04.032

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing.

Andreassen, C. S., Torsheim, T., Brunborg, G. S., & Pallesen, S. (2012). Development of a Facebook Addiction Scale. Psychological Reports, 110(2), 501–517. https://doi.org/10.2466/02.09.18.PR0.110.2.501-517

Baek, Y. M., Cho, Y., & Kim, H. (2014). Attachment style and its influence on the activities, motives, and consequences of SNS use. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 58(4), 522–541. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2014.966362

Balakrishnan, J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2017). Social media addiction: what is the role of content in YouTube? Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(3), 364–377. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.6.2017.058

Barry, C. T., Sidoti, C. L., Briggs, S. M., Reiter, S. R., & Lindsey, R. A. (2017). Adolescent social media use and mental health from adolescent and parent perspectives. Journal of Adolescence, 61, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.08.005

Biolcati, R., Mancini, G., Pupi, V., & Mugheddu, V. (2018). Facebook addiction: Onset predictors. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 7(6), 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm7060118

Błachnio, A., Przepiórka, A., & Pantic, I. (2015). Internet use, Facebook intrusion, and depression: results of a cross-sectional study. European Psychiatry, 30(6), 681–684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.04.002

Blackwell, D., Leaman, C., Tramposch, R., Osborne, C., & Liss, M. (2017). Extraversion, neuroticism, attachment style and fear of missing out as predictors of social media use and addiction. Personality and Individual Differences, 116, 69–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.04.039

Brailovskaia, J., & Margraf, J. (2016). Comparing Facebook users and Facebook non-users: Relationship between personality traits and mental health variables – An exploratory study. Plos One, 11(12), e0166999. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0166999

Brailovskaia, J., & Margraf, J. (2017). Facebook Addiction Disorder (FAD) among German students—A longitudinal approach. Plos One, 12(12), e0189719. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189719

Brailovskaia, J., Schillack, H., & Margraf, J. (2018). Facebook Addiction Disorder in Germany. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 21(7), 450–456. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2018.0140

Brailovskaia, J., Velten, J., & Margaf, J. (2019). Relationship between daily stress, depression symptoms, and Facebook Addiction Disorder in Germany and in the United States. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 22(9), 610–614. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2019.0165

Chow, T. S., & Wan, H. Y. (2017). Is there any ‘Facebook Depression’? Exploring the moderating roles of neuroticism, Facebook social comparison and envy. Personality and Individual Differences, 119, 277–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.07.032

Deters, F. G., & Mehl, M. R. (2013). Does posting Facebook status updates increase or decrease loneliness? An online social networking experiment. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 4(5), 579–586. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550612469233

Elhai, J. D., Levine, J. C., Dvorak, R. D., & Hall, B. J. (2016). Fear of missing out, need for touch, anxiety and depression are related to problematic smartphone use. Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 509–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.079

Ellison, N., Heino, R., & Gibbs, J. (2006). Managing impressions online: self-presentation processes in the online dating environment. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 11(2), 415–441. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2006.00020.x

Ellison, N. B., Steinfield, C., & Lampe, C. (2007). The benefits of Facebook “friends”: Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(4), 1143–1168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00367.x

Facebook. (2020). Company info about Facebook. Retrieved from: https://about.fb.com/company-info/

Fabris, M. A., Marengo, D., Longobardi, C., & Settanni, M. (2020). Investigating the links between fear of missing out, social media addiction, and emotional symptoms in adolescence: The role of stress associated with neglect and negative reactions on social media. Addictive Behaviors, 106, 106364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106364

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160.

Fox, J., & Moreland, J. J. (2015). The dark side of social networking sites: an exploration of the relational and psychological stressors associated with Facebook use and affordances. Computers in Human Behavior, 45, 168–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.11.083

Franchina, V., Vanden Abeele, M., van Rooij, A., Lo Coco, G., & De Marez, L. (2018). Fear of Missing Out as a predictor of problematic social media use and phubbing behavior among Flemish adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(10), 2319. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15102319

Frison, E., & Eggermont, S. (2015). The impact of daily stress on adolescents’ depressed mood: The role of social support seeking through Facebook. Computers in Human Behavior, 44, 315–325.

Frison, E., & Eggermont, S. (2016). Exploring the relationships between different types of Facebook use, perceived online social support, and adolescents’ depressed mood. Social Science Computer Review, 34(2), 153–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439314567449

Gibbons, F. X., & Buunk, B. P. (1999). Individual differences in social comparison: Development of a scale of social comparison orientation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(1), 129–142. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.76.1.129

Griffiths, M. D. (2018). Adolescent social networking: how do social media operators facilitate habitual use? Education and Health, 36(3), 66–69.

Hasin, D. S., Sarvet, A. L., Meyers, J. L., Saha, T. D., Ruan, W. J., Stohl, M., & Grant, B. F. (2018). Epidemiology of adult DSM-5 major depressive disorder and its specifiers in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(4), 336–346. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4602

Jelenchick, L. A., Eickhoff, J. C., & Moreno, M. A. (2013). “Facebook depression?” Social networking site use and depression in older adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 52(1), 128–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.05.008

Jeong, S.-H., Kim, H., Yum, J.-Y., & Hwang, Y. (2016). What type of content are smartphone users addicted to?: SNS vs. games. Computers in Human Behavior, 54, 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.07.035

Jin, B. (2013). How lonely people use and perceive Facebook. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(6), 2463–2470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.05.034

Kircaburun, K., & Griffiths, M. D. (2018). Instagram addiction and the Big Five of personality: the mediating role of self-liking. Journal of behavioral addictions, 7(1), 158–170. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.15

Koc, M., & Gulyagci, S. (2013). Facebook addiction among Turkish college students: the role of psychological health, demographic, and usage characteristics. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 16(4), 279–284. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0249

Kujath, C. L. (2011). Facebook and MySpace: Complement or substitute for face-to-face interaction? Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 14(1–2), 75–78. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2009.0311

Kuss, D. J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2011). Online social networking and addiction—a review of the psychological literature. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 8(9), 3528–3552. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph8093528

Kwon, O., & Wen, Y. (2010). An empirical study of the factors affecting social network service use. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(2), 254–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2009.04.011

Lee, S. L., Park, M. S. & Tam, C. L. (2015). The relationship between Facebook attachment and obsessive-compulsive disorder severity. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 9(2). https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2015-2-6

Lemieux, R., Lajoie, S., & Trainor, N. E. (2013). Affinity-seeking, social loneliness, and social avoidance among Facebook users. Psychological Reports, 112(2), 545–552. https://doi.org/10.2466/07.PR0.112.2.545-552

Li, Z. (2016). Psychological empowerment on social media: who are the empowered users? Public Relations Review, 42(1), 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2015.09.001

Mackson, S. B., Brochu, P. M., & Schneider, B. A. (2019). Instagram: Friend or foe? The application’s association with psychological well-being. New Media & Society, 21(10), 2160–2182. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819840021

Maxwell, J. P., Sukhodolsky, D. G., Chow, C. C. F., & Wong, C. F. C. (2005). Anger rumination in Hong Kong & Great Britain: validation of the scale and a cross-cultural comparison. Personality and Individual Differences, 39(6), 1147–1157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.03.022

McCarthy, P. A., & Morina, N. (2020). Exploring the association of social comparison with depression and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2452

Montague, E., & JieXu. (2012). Understanding active and passive users: the effects of an active user using normal, hard and unreliable technologies on user assessment of trust in technology and co-user. Applied Ergonomics, 43(4), 702–712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2011.11.002

Müller, S. M., Wegmann, E., Stolze, D., & Brand, M. (2020). Maximizing social outcomes? Social zapping and fear of missing out mediate the effects of maximization and procrastination on problematic social networks use. Computers in Human Behavior, 107, 106296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106296

Mushtaq, R., Shoib, S., Shah, T., & Mushtaq, S. (2014). Relationship between loneliness, psychiatric disorders and physical health? A review on the psychological aspects of loneliness. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research, 8(9), WE01-04. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2014/10077.4828

Nisar, T. M., Prabhakar, G., Ilavarasan, P. V., & Baabdullah, A. M. (2019). Facebook usage and mental health: an empirical study of role of non-directional social comparisons in the UK. International Journal of Information Management, 48, 53–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.01.017

Pagani, M., & Mirabello, A. (2011). The Influence of personal and social-interactive engagement in social TV web sites. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 16(2), 41–68. https://doi.org/10.2753/JEC1086-4415160203

Pantic, I. (2014). Online social networking and mental health. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 17(10), 652–657. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2014.0070

Perlman, D., & Peplau, L. A. (1981). Toward a social psychology of loneliness. In R. Gilmour, & S. Duck (Eds.) Personal relationships: 3. Relationships in disorder (pp. 31-56). London: Academic Press.

Phu, B., & Gow, A. J. (2019). Facebook use and its association with subjective happiness and loneliness. Computers in Human Behavior, 92, 151–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.11.020

Pontes, H. M., Taylor, M., & Stavropoulos, V. (2018). Beyond “Facebook addiction”: the role of cognitive-related factors and psychiatric distress in social networking site addiction. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 21(4), 240–247. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2017.0609

Przybylski, A. K., Murayama, K., DeHaan, C. R., & Gladwell, V. (2013). Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1841–1848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.02.014

Rajesh, T., & Rangaiah, D. B. (2020). Facebook addiction and personality. Heliyon, 6(1), e03184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03184

Reer, F., Tang, W. Y., & Quandt, T. (2019). Psychosocial well-being and social media engagement: the mediating roles of social comparison orientation and fear of missing out. New Media & Society, 21(7), 1486–1505. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818823719

Rosen, L. D., Whaling, K., Rab, S., Carrier, L. M., Cheever, N. A. (2013). Is Facebook creating “iDisorder”? The link between clinical symptoms of psychiatric disorders and technology use, attitudes and anxiety. Computers in Human Behavior, 29, 1243-1254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.11.012

Ross, C., Orr, E. S., Sisic, M., Arseneault, J. M., Simmering, M. G., & Orr, R. R. (2009). Personality and motivations associated with Facebook use. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(2), 578–586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2008.12.024

Rozgonjuk, D., Kattago, M., & Täht, K. (2018). Social media use in lectures mediates the relationship between procrastination and problematic smartphone use. Computers in Human Behavior, 89, 191–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.08.003

Russell, D. W. (1996). UCLA loneliness scale (version 3): reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66(1), 20–40. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2

Ryan, T., & Xenos, S. (2011). Who uses Facebook? An investigation into the relationship between the Big Five, shyness, narcissism, loneliness, and Facebook usage. Computers in Human Behavior, 27(5), 1658–1664.

Scott, G. G., Boyle, E. A., Czerniawska, K., & Courtney, A. (2018). Posting photos on Facebook: The impact of narcissism, social anxiety, loneliness, and shyness. Personality and Individual Differences, 133, 67–72.

Shettar, M., Karkal, R., Kakunje, A., Mendonsa, R. D., & Chandran, V. M. (2017). Facebook addiction and loneliness in the post-graduate students of a university in southern India. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 63(4), 325–329.

Skues, J. L., Williams, B., & Wise, L. (2012). The effects of personality traits, self-esteem, loneliness, and narcissism on Facebook use among university students. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(6), 2414–2419.

Smith, R. H., & Kim, S. H. (2007). Comprehending envy. Psychological Bulletin, 133(1), 46.

Song, H., Zmyslinski-Seelig, A., Kim, J., Drent, A., Victor, A., Omori, K., & Allen, M. (2014). Does Facebook make you lonely?: A meta analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 36, 446–452.

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W., & the Patient Health Questionnaire Primary Care Study Group. (1999). Validation and Utility of a Self-report Version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. JAMA, 282(18), 1737–1744. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.282.18.1737

Statista. (2020). Global digital population as of April 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/617136/digital-population-worldwide/

Sussman, S., Leventhal, A., Bluthenthal, R. N., Freimuth, M., Forster, M., & Ames, S. L. (2011). A framework for the specificity of addictions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 8(8), 3399–3415. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph8083399

Tandoc Jr, E. C., Ferrucci, P., & Duffy, M. (2015). Facebook use, envy, and depression among college students: Is facebooking depressing?. Computers in Human Behavior, 43, 139–146.

Thorisdottir, I. E., Sigurvinsdottir, R., Asgeirsdottir, B. B., Allegrante, J. P., & Sigfusdottir, I. D. (2019). Active and passive social media use and symptoms of anxiety and depressed mood among Icelandic adolescents. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 22(8), 535–542.

Verduyn, P., Lee, D. S., Park, J., Shablack, H., Orvell, A., Bayer, J., Ybarra, O., Jonides, J., & Kross, E. (2015). Passive Facebook usage undermines affective well-being: experimental and longitudinal evidence. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 144(2), 480–488. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000057

Walker-Harding, L. R., Christie, D., Joffe, A., Lau, J. S., & Neinstein, L. (2017). Young adult health and well-being: a position statement of the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine. Journal of Adolescent Health, 60(6), 758–759.

Wang, J. L., Wang, H. Z., Gaskin, J., & Hawk, S. (2017). The mediating roles of upward social comparison and selfesteem and the moderating role of social comparison orientation in the association between social networking site usage and subjective well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 771.

Wang, K., Frison, E., Eggermont, S., & Vandenbosch, L. (2018). Active public Facebook use and adolescents' feelings of loneliness: Evidence for a curvilinear relationship. Journal of Adolescence, 67, 35–44.

Wheeler, L., & Suls, J. (in press). The psychology of social comparison. In N.J. Smelser & P.B. Baltes (Eds.), International encylopedia of the social and behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Pergamon.

Yau, Y. H. C., Pilver, C. E., Steinberg, M. A., Rugle, L. J., Hoff, R. A., Krishnan-Sarin, S., & Potenza, M. N. (2014). Relationships between problematic Internet use and problem-gambling severity: Findings from a high-school survey. Addictive Behaviors, 39(1), 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.09.003

Yin, L., Wang, P., Nie, J., Guo, J., Feng, J., & Lei, L. (2019). Social networking sites addiction and FoMO: the mediating role of envy and the moderating role of need to belong. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00344-4

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MC participated in the study concept and design, as well as the data collection and the manuscript redaction; FN participated in the analysis and interpretation of data, and the manuscript redaction; MG helped in the proofreading and finalisation of the manuscript; MP participated in the study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript redaction, and supervised the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Statement

The project was approved by the research ethics committee of the first author’s institution and was conducted in line with the principles and guidelines of the American Psychological Association.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study and were made aware prior to participation that their data would be used for academic research and publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Casingcasing, M.L.S., Nuyens, F.M., Griffiths, M.D. et al. Does Social Comparison and Facebook Addiction Lead to Negative Mental Health? A Pilot Study of Emerging Adults Using Structural Equation Modelling. J. technol. behav. sci. 8, 69–78 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-022-00289-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-022-00289-9