Abstract

This study aimed to assess the impact of Internet use on the well-being and health behaviours of Generation Z members by evaluating the associations between the Internet habits (i.e. intensive Internet use and cybersex use), aspects of psychological well-being, and negative emotions of Italian Generation Z members. Study participants comprised 113 Italian youth who were divided into two groups: a cybersex user group (n = 48) and an intensive Internet user group (n = 65). The psychological battery applied was composed of the EPOCH Measure of Adolescent Well-Being and Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale test. This initial investigation suggests that there are no significant differences in positive psychological patterns between intensive Internet users and cybersex users. However, this study demonstrated gender differences in their levels of engagement. Overall, women appeared to be more focused on life activities, and men were more active and performance oriented. Despite this, intensive Internet use and cybersex use were not found to be related to emotional fragility. Our findings suggest that cybersex use and intensive Internet use may not necessarily be related to mental health risks; on the contrary, these might even be related to positive psychological patterns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Members of Generation Z (also known as Gen Z, iGen, or centennials), whom researchers generally classify as people born between the mid-to-late 1990s and the early 2010s (Dimock, 2019), are typically young and skilful users of information and communication technology. This generation’s widespread exposure to technology has resulted in their comfort with and strong knowledge of digital media. Furthermore, connectivity has become a major factor in their social interactions, education, work, friendships, and even relationships (Deal et al., 2010; Pinto & Ramalheira, 2017). While there have been several studies on the impact of technology on savvy, young users in terms of their cognitive development, mental skills, and learning (Tapscott, 1998; Di Giacomo et al., 2016a, b, 2017; Wang et al., 2010), few have focused on the influence of digital living on their emotional development and personality.

Whorta et al. (2019) investigated emotions in digital learning environments and found that positive, negative, neutral, and boredom profiles can be predictive of digital learning. Meanwhile, Spann et al. (2019) analysed digital youth’s affect regulation during game-based learning and suggested that frustration, confusion, determination, and curiosity were the dominant affective states of the youth, and cognitive reappraisal and acceptance their major affective regulation strategies. They also showed that during digital gaming, members of Generation Z tend to manage positive and negative emotions by engaging in cognitive reappraisal and are thereby able to alter the way they think about a game-related situation. This indicates that a new learning paradigm may be needed for Generation Z. Hence, more psychological investigations of the daily Internet habits of Generation Z are needed to more accurately determine the behavioural aspects of this generation’s Internet use.

Our interest in this area was in studying perspective. We desired to analyse the emotional aspects of young people in different social phenomena and to examine how these aspects are associated with intensive Internet use and cybersex use, behaviours frequently engaged in by members of Generation Z. An innovative approach to examining youth-related issues has recently emerged—the engagement, perseverance, optimism, connectedness, and happiness (EPOCH) model (Kern et al., 2016), which is oriented towards positive psychological functioning in youth. The EPOCH model focuses on positive psychological perspectives and good mental functioning rather than the absence of mental illness. The main focus of this approach is the benefits obtained from the development of personal strengths that build subjective psychological well-being. The relationship between positive psychological characteristics and different types of Internet use among the youth (e.g. intensive use and cybersex use) still requires further comprehensive investigations in conjunction with the application of the EPOCH model. The EPOCH model is built on the well-being theory, which focuses on positive psychological functioning. This study aimed to assess the impact of Internet use on the well-being and health behaviours of Generation Z by evaluating the associations between the Internet habits (i.e. intensive use and cybersex use), aspects of psychological well-being (assessed using the EPOCH measure), and negative emotions of Italian Generation Z members.

Methods

Ethical Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (see WMA, 2020), and prior informed consent was obtained from each participant

Sample

The study participants comprised 113 Italian youth (age range 18–25 years; men = 62 and women = 51) who were divided into two groups: a cybersex use and an intensive Internet use group. The cybersex use group was composed of 65 participants who had a focused pursuit of sexual interests on the Internet, while the intensive Internet use group was composed of 48 participants who surfed the Web more than 6 h per day. Group classifications were based on ad hoc testing. There was no risk for overlap effect observed among subjects. The cybersex group spent between 3 and 5 h on Internet activities per week, whereas the intensive Internet group spent between 20 and 26 h per week (typically spent on forums, blogs, simple Web surfing, online social networking, and online shopping). The inclusion criteria for participation in this study were as follows: (a) aged 18–25 years, (b) possessed no signs of psychiatric or neurological impairment, and (c) had provided informed consent. Data were collected using a dedicated questionnaire and codified. Table 1 summarizes the participants’ demographic data.

Study Measurement Instruments

The study measurement instruments used to collect data on demographic characteristics, Internet use, and psychological wellness included a demographic questionnaire, the EPOCH assessment measure, and the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21).

Demographic Questionnaire. A questionnaire that had been developed for the study was used to gather data on the participants’ sociodemographic characteristics, such as their age, residential area, and time and type of Internet use. Participants were divided into either the cybersex use or intensive Internet use groups based on their answers on the questionnaire. Participants were classified into the cybersex use group based on the following characteristics: (a) possessed a desire for sexual pleasure through online content and (b) derived daily sexual pleasure from online content. Meanwhile, participants were classified into the intensive Internet use group based on the following characteristics: (a) the duration of time they spent online, (b) the type of social media they used (e.g. Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, or others), (c) their use intensity of online gaming, and (d) their perceived pleasure through Internet use.

EPOCH Measure of Adolescent Well-Being (Kern et al., 2016). This measure is a self-report questionnaire composed of 20 items, with item responses rated on a 5-point scale (‘never’ = 1, ‘sometimes’ = 2, ‘often’ = 3, ‘very often’ = 4, ‘always’ = 5). It assesses five positive psychological characteristics that might foster well-being, physical health, and other positive outcomes in adulthood: engagement, perseverance, optimism, connectedness, and happiness. These have been defined as follows: engagement refers to the capacity to become absorbed in and to focus on what one is doing, as well as one’s involvement and interest in life activities (= functions that are important for daily lives as well caring for oneself, performing manual tasks, seeing, hearing, eating, sleeping, walking, learning, reading, and working) and tasks. Perseverance refers to the ability to pursue one’s goals to completion, even in the face of obstacles. Optimism is characterised by hopefulness and confidence about the future, a tendency to take a favourable view of things, and an explanatory style marked by evaluating negative events as temporary, external, and specific to situations. Connectedness refers to the sense that one has satisfying relationships with others, believing that one is cared for, loved, esteemed, and valued, and providing friendship or support to others. Happiness is conceptualised as steady states of positive mood and feeling content with one’s life, rather than momentary emotion.

Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21; Beaufort et al., 2017). The DASS-21 is a self-administrated questionnaire that measures the degree of severity of the core symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress among respondents. The questionnaire is composed of 21 questions, with item responses rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (‘I strongly disagree’) to 3 (‘I totally agree’).

Procedure

Individuals were recruited using snowball sampling, a non-randomised method of sample selection. Research staff provided a digital form of the test protocol. After, the self-report questionnaires were linked on a dedicated online website so that participants could access them and provide the mandatory signed informed consent. The amount of time that was necessary to complete the entire process was about 20 min. Data were collected using a dedicated server and scored by trained professionals blinded to the study’s objectives.

Study Design

This was an observational study of Italian youth recruited via Facebook.

The study sample was divided into two groups: a cybersex use group and an intensive Internet use group. The sample’s characteristics were analysed using descriptive statistics. A multivariate analysis of variance was performed to compare categorical variables (i.e. sex, grouping, and psychological measures). Pearson’s test was applied to evaluate the relationships between the psychological measures. Statistical analyses were performed using the SSPS software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA), and the statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Collected data were statistically analysed. Table 2 summarizes the raw scores (in means and standard deviations) obtained from the psychological tests.

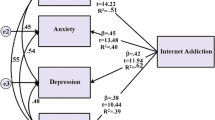

The results of the multivariate analysis of variance (Wilks analysis) that compared the two groups (cybersex and intensive Internet), eight psychological indexes (five EPOCH and three DASS-21 measures), and two genders (men and women) revealed significant differences between gender, (F(102, 8) = 2.21; π = 0.8; p = 0.03), and no difference between groups; the gender × group interaction was significant, F(102, 8) = 0.91; π = 0.8; p = 0.006. A gender effect analysis for the EPOCH dimensions showed a lower level of engagement index in women (p = 0.01), as reported in Fig. 1. Meanwhile, for the results regarding the DASS-21 performance, men showed a lower level of anxiety (p = 0.04).

Regarding positive psychological traits, men showed a higher EPOCH engagement level (i.e. the capacity to become absorbed in and to focus on what one is doing as well as one’s involvement and interest in life activities and tasks). Other EPOCH domains did not differ significantly.

Analysing the significant gender × group interaction for psychological traits (EPOCH), we observed the involvement of almost all indexes investigated (Fig. 2). First, for the significance of engagement index detected in the gender analysis, the interaction effect vanished; perseverance (F(112,1) = 4.61; π = 0.06; p = 0.03), optimism (F(112, 1) = 7.10; π = 0.06; p = 0.007), connectedness (F(112, 1) = 7.70; π = 0.8; p = 0.006), and happiness (F(112, 1) = 7.43; π = 0.8; p = 0.007), significantly differed. The intensive Internet group seemed to be more influenced in almost all investigated indexes (e.g. perseverance, optimism, happiness), and within the groups, women showed lower performances in positive psychological traits (EPOCH model). Cybersex appeared to have significantly influenced the men’s optimism and happiness dimensions.

Examining negative psychological characteristics by performance in the DASS-21, a statistical analysis evidenced no significant differences in stress and depression between the cybersex use and intensive internet use groups but significant differences between genders: anxiety (F(102, 8) = 6,88; π = 0.07; p = 0.01); stress (F(102, 8) = 4.91; π = 0.06; p = 0.02); no gender × group interaction was significant. No sign of depression among the participants was detected, and no significant differences between groups and genders were uncovered. As reported in Fig. 3, anxiety and stress were both influenced psychological variables.

A correlation analysis (Pearson’s test) was then conducted on the psychological measures (as shown in Table 3). We analysed the relationship between positive (EPOCH indexes) and negative (DASS-21 indexes) dimensions among participants, the results of which suggested that EPOCH engagement was correlated with anxiety, depression, and stress among both cybersex users and intensive Internet users, and optimism with all three negative emotions. Perseverance was found to only affect depression. Lastly, connectedness and happiness were correlated with anxiety and depression.

Discussion and Conclusions

This study sought to investigate the impact of internet usage on Generation Z with regards to their well-being by applying the EPOCH model. The research focused on analysing the influence of Internet usage (in the form of cybersex use and intensive Internet use) on the psychological well-being of Generation Z members through an evaluation of EPOCH positive traits (e.g. engagement, perseverance, optimism, connectedness, and happiness) and negative emotional dimensions (e.g. anxiety, depression, and stress). Our findings highlight two interesting key points: (1) Internet usage does not affect the youth’s psychological aspect of well-being and (2) the gender effect can function as a predictive factor related to the risk for well-being associated with internet usage. This study evidenced salient findings on the impact of Internet use on the well-being and health behaviours of the youth, promoting positive psychological perspectives and good functioning. We argue that members of Generation Z who engage in cybersex or intensive Internet use do not demonstrate different positive psychological patterns from one another. However, a significant difference was found in terms of gender independently by cybersex/internet usage propensity. Applying the EPOCH model, gender was observed to be potentially predictive of lower well-being. Moreover, using the EPOCH framework, men seemed more active and performance-oriented, whereas women appeared to be less optimistic and perseverant as well as happy and connected. Furthermore, the higher level of anxiety among the women seemed to negatively affect their level of persistence and resilience. Our finding confirmed the emerging ad prevalent mental health topic related to the personality dimensions, treatment effect studies giving greater consideration of sex throughout the research process (Bekker & van Mens-Verhulst, 2007).

Nevertheless, this study also found that cybersex use and intensive Internet use was not predictive factor: Generation Z was digital skilled and may be that could be protecting them to the prolonged exposition of internet being skilled into management of discomfort of addiction risk. Taking into account Spann’s framework (Spann et al., 2019), the correlation findings on positive and negative emotional patterns showed the ability of Generation Z to manage conflicting emotions, balancing them into cognitive modulations. This ability appears not to be negatively affected by their age or Internet habits.

A limitation of the study is its sample size, and a larger sample should be applied in the future for more generalizable elaborations.

In conclusion, our study is preliminary and further research on the mental characteristics of Generation Z is needed. However, our findings suggest that cybersex and intensive Internet use may not necessarily be related to risks for emotional disorders; on the contrary, these might even be related to positive psychological patterns. Generation Z represents a new target population of youth associated to digital skills and with improved cognitive development; both characteristics could be protective factors for emotional patterns. This population has new needs and strengths that are based on a new framework of psychological patterns.

References

Beaufort, I. N., De Weert-Van Oene, G. H., Buwalda, V. A., de, J. R. J., Leeuw, & Goudriaan, A. E. (2017). The Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21) as a screener for depression in substance use disorder inpatients: a pilot study. European Addiction Research, 23, 260–268. https://doi.org/10.1159/000485182.

Bekker, M., & van Mens-Verhulst, J. (2007). Anxiety disorders: Sex differences in prevalence, degree, and background, but gender-neutral treatment. Gender Medicine, 4(2), S178–S193. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1550-8579(07)80057-X.

Deal, J. J., Altman, D. G. and Rogelberg, S. G. (2010) “Millennials at work: What we know and what we need to do (if anything)". Journal of Business and Psychology, 258(2) https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9177-2

Di Giacomo, D., Ranieri, J., & Lacasa, P. (2017). Digital learning as enhanced learning processing? Cognitive evidence for new insight of smart learning. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1329. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01329.

Di Giacomo, D., Caputi, N., & Vittorini, P. (2016). Technology and learning processing in childhood: Enhancing the children outcomes. Interactive Learning: Strategies, Technologies and Effectiveness. Nova Publishing.

Di Giacomo, D., Cofini, V., Di Mascio, T., Cecilia, M. R., Fiorenzi, D., Gennari, R., et al. (2016). The silent reading supported by adaptive learning technology: Influence in the children outcomes. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 1125–1130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.09.053.

Dimock M (2019) Defining generations: Where Millennials end and Generation Z begins. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/01/17/where-millennials-end-and-generation-z-begins/

Kern, M. L., Benson, L., Steinberg, E. A., & Steinberg, L. (2016). The EPOCH measure of adolescent well-being. Psychological Assessment, 28(5), 586–597.

Pinto, L. H., & Ramalheira, D. C. (2017). Perceived employability of business graduates: The effect of academic performance and extracurricular activities. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 99, 165–178.

Spann, C. A., Shute, V. J., Rahimi, S., & D’Mello, S. K. (2019). The productive role of cognitive reappraisal in regulating affect during gamebased learning. Computers in Human Behavior, 100, 358–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.03.002.

Tapscott, D. (1998). Growing up digital: The rise of the net generation. New York: McGraw Hill.

Wang, M., Ran, W., Liao, J., & Yang, S. (2010). A performance-oriented approach to e-learning in the workplace. Educational Technology & Society, 13, 167–179.

Wortha, F., Azevedo, R., Taub, M., & Narciss, S. (2019). Multiple negative emotions during learning with digital learning environments – Evidence on their detrimental effect on learning from two methodological approaches. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2678. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.0267.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi dell’Aquila.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ranieri, J., Guerra, F., Martelli, A. et al. Impact of Cybersex and Intensive Internet Use on the Well-Being of Generation Z: An Analysis Based on the EPOCH Model. J. technol. behav. sci. 6, 501–506 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-021-00197-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-021-00197-4